Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Literary Genres — Short Story

Essays on Short Story

Brief description of short story, importance of writing essays on this topic, tips on choosing a good topic, essay topics, concluding thought, the importance of foreshadowing in roald dahl’s the landlady, julius excluded from heaven analysis, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Situational Irony: a Closer Look at Unexpected Twists in Literature

Darkness in the short stories of james joyce, description of an abandoned house: a short story, personal development of the main character in raymond's run, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Bridging The Gap: Comparing "Letters from My Father" and "The Writer"

The effects of class and morality in 'the boarding house' by james joyce, the connection between art and history for julian barnes, analysis of the short story 'the storm' by kate chopin, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Analysis of Anton Chekhov’s Short Story "Agafya"

Sister lilith by honorée fanonne jeffers: dismissal of patriarchal values, critical analysis of the lesson by toni cade bambara, our town by thornton wilder: the message to appreciate life, a brief history of perfume, my most embarrassing moment, "a man called horse" as transgression of the western genre, readers’ interpretation of barn burning by haruki murakami, gaze through the window: paralyses in joyce's "dubliners", feeling of imprisonment, blind devotion in james joyce’s "araby", life and death in "dubliners" by james joyce, epiphany in james joyce’s araby, already dead: the need for human interaction in butler’s "titanic victim speaks through waterbed", poe’s use of literary techniques in the tell-tale heart, main themes in kate chopin's 'the storm', the yellow wallpaper by charlotte perkins gilman: a woman’s plight, mrs. fullerton’s odd dominos of ambition, two-faced: characterization in bad haircut, analysis of setting in ‘’eveline’’ by james joyce, relevant topics.

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 great narrative essay examples + tips for writing.

General Education

A narrative essay is one of the most intimidating assignments you can be handed at any level of your education. Where you've previously written argumentative essays that make a point or analytic essays that dissect meaning, a narrative essay asks you to write what is effectively a story .

But unlike a simple work of creative fiction, your narrative essay must have a clear and concrete motif —a recurring theme or idea that you’ll explore throughout. Narrative essays are less rigid, more creative in expression, and therefore pretty different from most other essays you’ll be writing.

But not to fear—in this article, we’ll be covering what a narrative essay is, how to write a good one, and also analyzing some personal narrative essay examples to show you what a great one looks like.

What Is a Narrative Essay?

At first glance, a narrative essay might sound like you’re just writing a story. Like the stories you're used to reading, a narrative essay is generally (but not always) chronological, following a clear throughline from beginning to end. Even if the story jumps around in time, all the details will come back to one specific theme, demonstrated through your choice in motifs.

Unlike many creative stories, however, your narrative essay should be based in fact. That doesn’t mean that every detail needs to be pure and untainted by imagination, but rather that you shouldn’t wholly invent the events of your narrative essay. There’s nothing wrong with inventing a person’s words if you can’t remember them exactly, but you shouldn’t say they said something they weren’t even close to saying.

Another big difference between narrative essays and creative fiction—as well as other kinds of essays—is that narrative essays are based on motifs. A motif is a dominant idea or theme, one that you establish before writing the essay. As you’re crafting the narrative, it’ll feed back into your motif to create a comprehensive picture of whatever that motif is.

For example, say you want to write a narrative essay about how your first day in high school helped you establish your identity. You might discuss events like trying to figure out where to sit in the cafeteria, having to describe yourself in five words as an icebreaker in your math class, or being unsure what to do during your lunch break because it’s no longer acceptable to go outside and play during lunch. All of those ideas feed back into the central motif of establishing your identity.

The important thing to remember is that while a narrative essay is typically told chronologically and intended to read like a story, it is not purely for entertainment value. A narrative essay delivers its theme by deliberately weaving the motifs through the events, scenes, and details. While a narrative essay may be entertaining, its primary purpose is to tell a complete story based on a central meaning.

Unlike other essay forms, it is totally okay—even expected—to use first-person narration in narrative essays. If you’re writing a story about yourself, it’s natural to refer to yourself within the essay. It’s also okay to use other perspectives, such as third- or even second-person, but that should only be done if it better serves your motif. Generally speaking, your narrative essay should be in first-person perspective.

Though your motif choices may feel at times like you’re making a point the way you would in an argumentative essay, a narrative essay’s goal is to tell a story, not convince the reader of anything. Your reader should be able to tell what your motif is from reading, but you don’t have to change their mind about anything. If they don’t understand the point you are making, you should consider strengthening the delivery of the events and descriptions that support your motif.

Narrative essays also share some features with analytical essays, in which you derive meaning from a book, film, or other media. But narrative essays work differently—you’re not trying to draw meaning from an existing text, but rather using an event you’ve experienced to convey meaning. In an analytical essay, you examine narrative, whereas in a narrative essay you create narrative.

The structure of a narrative essay is also a bit different than other essays. You’ll generally be getting your point across chronologically as opposed to grouping together specific arguments in paragraphs or sections. To return to the example of an essay discussing your first day of high school and how it impacted the shaping of your identity, it would be weird to put the events out of order, even if not knowing what to do after lunch feels like a stronger idea than choosing where to sit. Instead of organizing to deliver your information based on maximum impact, you’ll be telling your story as it happened, using concrete details to reinforce your theme.

3 Great Narrative Essay Examples

One of the best ways to learn how to write a narrative essay is to look at a great narrative essay sample. Let’s take a look at some truly stellar narrative essay examples and dive into what exactly makes them work so well.

A Ticket to the Fair by David Foster Wallace

Today is Press Day at the Illinois State Fair in Springfield, and I’m supposed to be at the fairgrounds by 9:00 A.M. to get my credentials. I imagine credentials to be a small white card in the band of a fedora. I’ve never been considered press before. My real interest in credentials is getting into rides and shows for free. I’m fresh in from the East Coast, for an East Coast magazine. Why exactly they’re interested in the Illinois State Fair remains unclear to me. I suspect that every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember that about 90 percent of the United States lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropological reporting on something rural and heartlandish. I think they asked me to do this because I grew up here, just a couple hours’ drive from downstate Springfield. I never did go to the state fair, though—I pretty much topped out at the county fair level. Actually, I haven’t been back to Illinois for a long time, and I can’t say I’ve missed it.

Throughout this essay, David Foster Wallace recounts his experience as press at the Illinois State Fair. But it’s clear from this opening that he’s not just reporting on the events exactly as they happened—though that’s also true— but rather making a point about how the East Coast, where he lives and works, thinks about the Midwest.

In his opening paragraph, Wallace states that outright: “Why exactly they’re interested in the Illinois State Fair remains unclear to me. I suspect that every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember that about 90 percent of the United States lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropological reporting on something rural and heartlandish.”

Not every motif needs to be stated this clearly , but in an essay as long as Wallace’s, particularly since the audience for such a piece may feel similarly and forget that such a large portion of the country exists, it’s important to make that point clear.

But Wallace doesn’t just rest on introducing his motif and telling the events exactly as they occurred from there. It’s clear that he selects events that remind us of that idea of East Coast cynicism , such as when he realizes that the Help Me Grow tent is standing on top of fake grass that is killing the real grass beneath, when he realizes the hypocrisy of craving a corn dog when faced with a real, suffering pig, when he’s upset for his friend even though he’s not the one being sexually harassed, and when he witnesses another East Coast person doing something he wouldn’t dare to do.

Wallace is literally telling the audience exactly what happened, complete with dates and timestamps for when each event occurred. But he’s also choosing those events with a purpose—he doesn’t focus on details that don’t serve his motif. That’s why he discusses the experiences of people, how the smells are unappealing to him, and how all the people he meets, in cowboy hats, overalls, or “black spandex that looks like cheesecake leotards,” feel almost alien to him.

All of these details feed back into the throughline of East Coast thinking that Wallace introduces in the first paragraph. He also refers back to it in the essay’s final paragraph, stating:

At last, an overarching theory blooms inside my head: megalopolitan East Coasters’ summer treats and breaks and literally ‘getaways,’ flights-from—from crowds, noise, heat, dirt, the stress of too many sensory choices….The East Coast existential treat is escape from confines and stimuli—quiet, rustic vistas that hold still, turn inward, turn away. Not so in the rural Midwest. Here you’re pretty much away all the time….Something in a Midwesterner sort of actuates , deep down, at a public event….The real spectacle that draws us here is us.

Throughout this journey, Wallace has tried to demonstrate how the East Coast thinks about the Midwest, ultimately concluding that they are captivated by the Midwest’s less stimuli-filled life, but that the real reason they are interested in events like the Illinois State Fair is that they are, in some ways, a means of looking at the East Coast in a new, estranging way.

The reason this works so well is that Wallace has carefully chosen his examples, outlined his motif and themes in the first paragraph, and eventually circled back to the original motif with a clearer understanding of his original point.

When outlining your own narrative essay, try to do the same. Start with a theme, build upon it with examples, and return to it in the end with an even deeper understanding of the original issue. You don’t need this much space to explore a theme, either—as we’ll see in the next example, a strong narrative essay can also be very short.

Death of a Moth by Virginia Woolf

After a time, tired by his dancing apparently, he settled on the window ledge in the sun, and, the queer spectacle being at an end, I forgot about him. Then, looking up, my eye was caught by him. He was trying to resume his dancing, but seemed either so stiff or so awkward that he could only flutter to the bottom of the window-pane; and when he tried to fly across it he failed. Being intent on other matters I watched these futile attempts for a time without thinking, unconsciously waiting for him to resume his flight, as one waits for a machine, that has stopped momentarily, to start again without considering the reason of its failure. After perhaps a seventh attempt he slipped from the wooden ledge and fell, fluttering his wings, on to his back on the window sill. The helplessness of his attitude roused me. It flashed upon me that he was in difficulties; he could no longer raise himself; his legs struggled vainly. But, as I stretched out a pencil, meaning to help him to right himself, it came over me that the failure and awkwardness were the approach of death. I laid the pencil down again.

In this essay, Virginia Woolf explains her encounter with a dying moth. On surface level, this essay is just a recounting of an afternoon in which she watched a moth die—it’s even established in the title. But there’s more to it than that. Though Woolf does not begin her essay with as clear a motif as Wallace, it’s not hard to pick out the evidence she uses to support her point, which is that the experience of this moth is also the human experience.

In the title, Woolf tells us this essay is about death. But in the first paragraph, she seems to mostly be discussing life—the moth is “content with life,” people are working in the fields, and birds are flying. However, she mentions that it is mid-September and that the fields were being plowed. It’s autumn and it’s time for the harvest; the time of year in which many things die.

In this short essay, she chronicles the experience of watching a moth seemingly embody life, then die. Though this essay is literally about a moth, it’s also about a whole lot more than that. After all, moths aren’t the only things that die—Woolf is also reflecting on her own mortality, as well as the mortality of everything around her.

At its core, the essay discusses the push and pull of life and death, not in a way that’s necessarily sad, but in a way that is accepting of both. Woolf begins by setting up the transitional fall season, often associated with things coming to an end, and raises the ideas of pleasure, vitality, and pity.

At one point, Woolf tries to help the dying moth, but reconsiders, as it would interfere with the natural order of the world. The moth’s death is part of the natural order of the world, just like fall, just like her own eventual death.

All these themes are set up in the beginning and explored throughout the essay’s narrative. Though Woolf doesn’t directly state her theme, she reinforces it by choosing a small, isolated event—watching a moth die—and illustrating her point through details.

With this essay, we can see that you don’t need a big, weird, exciting event to discuss an important meaning. Woolf is able to explore complicated ideas in a short essay by being deliberate about what details she includes, just as you can be in your own essays.

Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

On the twenty-ninth of July, in 1943, my father died. On the same day, a few hours later, his last child was born. Over a month before this, while all our energies were concentrated in waiting for these events, there had been, in Detroit, one of the bloodiest race riots of the century. A few hours after my father’s funeral, while he lay in state in the undertaker’s chapel, a race riot broke out in Harlem. On the morning of the third of August, we drove my father to the graveyard through a wilderness of smashed plate glass.

Like Woolf, Baldwin does not lay out his themes in concrete terms—unlike Wallace, there’s no clear sentence that explains what he’ll be talking about. However, you can see the motifs quite clearly: death, fatherhood, struggle, and race.

Throughout the narrative essay, Baldwin discusses the circumstances of his father’s death, including his complicated relationship with his father. By introducing those motifs in the first paragraph, the reader understands that everything discussed in the essay will come back to those core ideas. When Baldwin talks about his experience with a white teacher taking an interest in him and his father’s resistance to that, he is also talking about race and his father’s death. When he talks about his father’s death, he is also talking about his views on race. When he talks about his encounters with segregation and racism, he is talking, in part, about his father.

Because his father was a hard, uncompromising man, Baldwin struggles to reconcile the knowledge that his father was right about many things with his desire to not let that hardness consume him, as well.

Baldwin doesn’t explicitly state any of this, but his writing so often touches on the same motifs that it becomes clear he wants us to think about all these ideas in conversation with one another.

At the end of the essay, Baldwin makes it more clear:

This fight begins, however, in the heart and it had now been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair. This intimation made my heart heavy and, now that my father was irrecoverable, I wished that he had been beside me so that I could have searched his face for the answers which only the future would give me now.

Here, Baldwin ties together the themes and motifs into one clear statement: that he must continue to fight and recognize injustice, especially racial injustice, just as his father did. But unlike his father, he must do it beginning with himself—he must not let himself be closed off to the world as his father was. And yet, he still wishes he had his father for guidance, even as he establishes that he hopes to be a different man than his father.

In this essay, Baldwin loads the front of the essay with his motifs, and, through his narrative, weaves them together into a theme. In the end, he comes to a conclusion that connects all of those things together and leaves the reader with a lasting impression of completion—though the elements may have been initially disparate, in the end everything makes sense.

You can replicate this tactic of introducing seemingly unattached ideas and weaving them together in your own essays. By introducing those motifs, developing them throughout, and bringing them together in the end, you can demonstrate to your reader how all of them are related. However, it’s especially important to be sure that your motifs and clear and consistent throughout your essay so that the conclusion feels earned and consistent—if not, readers may feel mislead.

5 Key Tips for Writing Narrative Essays

Narrative essays can be a lot of fun to write since they’re so heavily based on creativity. But that can also feel intimidating—sometimes it’s easier to have strict guidelines than to have to make it all up yourself. Here are a few tips to keep your narrative essay feeling strong and fresh.

Develop Strong Motifs

Motifs are the foundation of a narrative essay . What are you trying to say? How can you say that using specific symbols or events? Those are your motifs.

In the same way that an argumentative essay’s body should support its thesis, the body of your narrative essay should include motifs that support your theme.

Try to avoid cliches, as these will feel tired to your readers. Instead of roses to symbolize love, try succulents. Instead of the ocean representing some vast, unknowable truth, try the depths of your brother’s bedroom. Keep your language and motifs fresh and your essay will be even stronger!

Use First-Person Perspective

In many essays, you’re expected to remove yourself so that your points stand on their own. Not so in a narrative essay—in this case, you want to make use of your own perspective.

Sometimes a different perspective can make your point even stronger. If you want someone to identify with your point of view, it may be tempting to choose a second-person perspective. However, be sure you really understand the function of second-person; it’s very easy to put a reader off if the narration isn’t expertly deployed.

If you want a little bit of distance, third-person perspective may be okay. But be careful—too much distance and your reader may feel like the narrative lacks truth.

That’s why first-person perspective is the standard. It keeps you, the writer, close to the narrative, reminding the reader that it really happened. And because you really know what happened and how, you’re free to inject your own opinion into the story without it detracting from your point, as it would in a different type of essay.

Stick to the Truth

Your essay should be true. However, this is a creative essay, and it’s okay to embellish a little. Rarely in life do we experience anything with a clear, concrete meaning the way somebody in a book might. If you flub the details a little, it’s okay—just don’t make them up entirely.

Also, nobody expects you to perfectly recall details that may have happened years ago. You may have to reconstruct dialog from your memory and your imagination. That’s okay, again, as long as you aren’t making it up entirely and assigning made-up statements to somebody.

Dialog is a powerful tool. A good conversation can add flavor and interest to a story, as we saw demonstrated in David Foster Wallace’s essay. As previously mentioned, it’s okay to flub it a little, especially because you’re likely writing about an experience you had without knowing that you’d be writing about it later.

However, don’t rely too much on it. Your narrative essay shouldn’t be told through people explaining things to one another; the motif comes through in the details. Dialog can be one of those details, but it shouldn’t be the only one.

Use Sensory Descriptions

Because a narrative essay is a story, you can use sensory details to make your writing more interesting. If you’re describing a particular experience, you can go into detail about things like taste, smell, and hearing in a way that you probably wouldn’t do in any other essay style.

These details can tie into your overall motifs and further your point. Woolf describes in great detail what she sees while watching the moth, giving us the sense that we, too, are watching the moth. In Wallace’s essay, he discusses the sights, sounds, and smells of the Illinois State Fair to help emphasize his point about its strangeness. And in Baldwin’s essay, he describes shattered glass as a “wilderness,” and uses the feelings of his body to describe his mental state.

All these descriptions anchor us not only in the story, but in the motifs and themes as well. One of the tools of a writer is making the reader feel as you felt, and sensory details help you achieve that.

What’s Next?

Looking to brush up on your essay-writing capabilities before the ACT? This guide to ACT English will walk you through some of the best strategies and practice questions to get you prepared!

Part of practicing for the ACT is ensuring your word choice and diction are on point. Check out this guide to some of the most common errors on the ACT English section to be sure that you're not making these common mistakes!

A solid understanding of English principles will help you make an effective point in a narrative essay, and you can get that understanding through taking a rigorous assortment of high school English classes !

Melissa Brinks graduated from the University of Washington in 2014 with a Bachelor's in English with a creative writing emphasis. She has spent several years tutoring K-12 students in many subjects, including in SAT prep, to help them prepare for their college education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Short Story Analysis Essay

Almost everyone has read a couple of short stories from the time they were kids up until today. Although, depending on how old you are, you analyze the stories you read differently. As a kid, you often point out who is the good guy and the bad guy. You even express your complaints if you do not like the ending. Now, in high school or maybe in college, you pretty much do the same, but you need to incorporate your critical thinking skills and follow appropriate formatting. That said, to present the results of your literature review, compose a short story analysis essay.

3+ Short Story Analysis Essay Examples

1. short story analysis essay template.

Size: 310 KB

2. Sample Short Story Analysis Essay

Size: 75 KB

3. Short Story Analysis Essay Example

Size: 298 KB

4. Printable Short Story Analysis Essay

Size: 121 KB

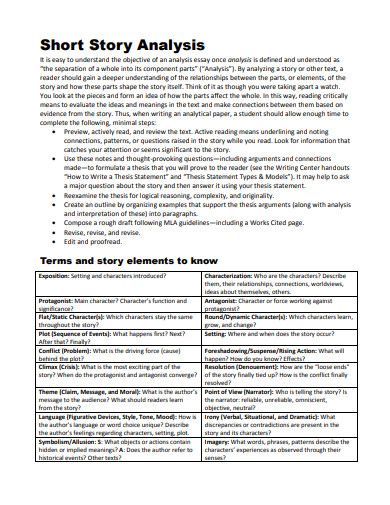

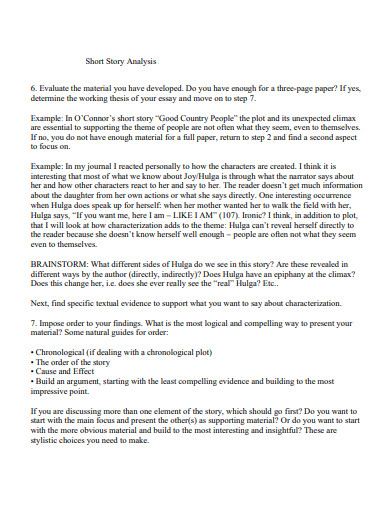

What Is a Short Story Analysis Essay?

A short story analysis essay is a composition that aims to examine the plot and the aspects of the story. In writing this document, the writer needs to take the necessary elements of a short story into account. In addition, one purpose of writing this type of analysis essay is to identify the theme of the story. As well as try to make connections between the different aspects.

How to Compose a Critical Short Story Analysis Essay

Having the assignment to write a short story analysis can be overwhelming. Reading the short story is easy enough. Evaluating and writing down your essay is the challenging part. A short story analysis essay follows a different format from other literature essays . That said, to help with that, here are instructive steps and helpful tips.

1. Take Down Notes

Considering that you have read the short story a couple of times, the first step you should take before writing your essay is to summarize and write down your notes. To help you with this, you can utilize flow charts to determine the arcs the twists of the short story. Include the parts and segments that affected you the most, as well as the ones that hold significance for the whole story.

2. Compose Your Thesis Statement

Before composing your thesis statement for the introductory paragraph of your essay, first, you need to identify the thematic statement of the story. This sentence should present the underlying message of the entire literature. It is where the story revolves around. After that, you can use it as a basis and proceed with composing your thesis statement. It should provide the readers an overview of the content of your analysis paper.

3. Analyze the Concepts

One of the essential segments of your paper is, of course, the analysis part. In the body of your essay, you should present arguments that discuss the concepts that you were able to identify. To support your point, you should provide evidence and quote sentences from the story. If you present strong supporting sentences, it will make your composition more effective. To help with the organization and the structure, you can utilize an analysis paper outline .

4. Craft Your Conclusion

The last part of the process is to craft a conclusion for your essay . Aside from restating the crucial points and the thesis statement, there is another factor that you should consider for the ending paragraph. That said, you should also present your understanding regarding why the author wrote the story that way. In addition, you can also wrap it up by expressing how the story made you feel.

How to run an in-depth analysis of a short story?

In analyzing a short story, you should individually examine the elements of a short story. That said, you need to study the characters, setting, tone, and plot. In addition, you should also consider evaluating the author’s point of view, writing style, and story-telling method. Also, it involves studying how the story affects you personally.

Why is it necessary to compose analysis essays?

Composing analysis essays tests how well a person understands a reading material. It is a good alternative for reading comprehension worksheets . Another advantage of devising this paper is it encourages people to look at a story from different angles and perspectives. In addition to this, it lets the students enhance their article writing potential.

What is critical writing?

Conducting a critical analysis requires an individual to examine the details and facts in the literature closely. It involves breaking down ideas as well as linking them to develop a point or argument. Despite that, the prime purpose of a critical essay is to give a literary criticism of the things the author did well and the things they did poorly.

People enjoy reading short stories. It is for the reason that aside from being brief, they also present meaningful messages and themes. In addition to that, it also brings you to a memorable ride with its entertaining conflicts and plot twists. That said, as a sign of respect to the well-crafted literature, you should present your thoughts about it by generating a well-founded short story analysis essay.

Short Story Analysis Essay Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Short Story Analysis Essay on the theme of courage in "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty"

Short Story Analysis Essay on symbolism in "The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Short Essay

Last Updated: January 17, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 113,685 times.

Essay writing is a common assignment in high school or college courses, especially within the humanities. You’ll also be asked to write essays for college admissions and scholarships. In a short essay (250-500 words), you will need to provide an introduction with a thesis, a body, and a conclusion, as you would with a longer essay. Depending on the essay requirements, you may also need to do academic or online research to find sources to back up your claims.

Picking a Topic and Gathering Research

- If you have any questions about the topic, ask your instructor. If your essay doesn't respond to the prompt, you likely won't receive full credit.

- If you're writing an essay for an in-class test or for an application, tailor the essay to the given prompt and topic. Quickly brainstorm a few ideas; for example, think of positive things you can say about yourself for a college-entrance essay.

- For example, the topic “depression in American literature” is far too broad. Narrow down your topic to something like “Willie Loman’s depression in Death of a Salesman .”

- Or, you could write about a narrow topic like “the increase in the USA’s national debt in the 1950s” rather than a broad topic like “the American economy in the 20th century.”

- Depending on the field in which you’re writing the essay—e.g., hard sciences, sociology, humanities, etc.—your instructor will direct you towards appropriate databases. For example, if you’re writing a high-school or college-level essay for your English class, visit online literary databases like JSTOR, LION, and the MLA Bibliography.

- If you're writing the essay for a college or graduate-school application, it's unlikely that you'll need to include any secondary sources.

- If you're writing a timed or in-class essay, you may not be able to find research articles. But, still do draw information from texts and sources you've studied both in and out of class, and build from points made in any provided reading passages.

- If you’re writing about current events or journalism topics, read articles from well-known news sites like CNN or the BBC.

- Avoid citing unreliable websites like blogs or any sites that have a clear bias about the topic they’re reporting on.

Composing the Essay

- If you write the essay without outlining, the essay will be poorly organized.

- This thesis statement is far too weak: “ Death of a Salesman shows the difficulty of living in America after WWII.”

- Instead, hone your thesis to something like: “Arthur Miller uses Death of a Salesman to show that the American Dream is materialist and impractical.”

- So, avoid beginning the paragraph by writing something like, “Since the beginning of time, all people have been consumed with the desire for their father’s approval.”

- Instead, write something like, “In the play Death of a Salesman , Willie Loman’s sons compete for their father’s approval through various masculine displays."

- Then, you can say, "To examine this topic, I will perform a close reading of several key passages of the play and present analyses by noted Arthur Miller scholars."

- In a short essay, the conclusion should do nothing more than briefly restate your main claim and remind readers of the evidence you provided.

- So, take the example about Death of a Salesman . The first body paragraph could discuss the ways in which Willie’s sons try to impress him.

- The second body paragraph could dive into Willie’s hopelessness and despair, and the third paragraph could discuss how Miller uses his characters to show the flaws in their understanding of the American Dream.

- Always cite your sources so you avoid charges of plagiarism. Check with your instructor (or the essay prompt) and find out what citation style you should use.

- For example, if you’re summarizing the inflation of the American dollar during the 1930s, provide 2 or 3 years and inflation-rate percentages. Don’t provide a full-paragraph summary of the economic decline.

- If you're writing an in-class essay and don't have time to perform any research, you don't need to incorporate outside sources. But, it will impress your teacher if you quote from a reading passage or bring up pertinent knowledge you may have gained during the class.

- If no one agrees to read the essay, read over your own first draft and look for errors or spots where you could clarify your meaning. Reading the essay out loud often helps, as you’ll be able to hear sentences that aren’t quite coherent.

- This step does not apply to essays written during a timed or in-class exam, as you won't be able to ask peers to read your work.

- It’s always a mistake to submit an unrevised first draft, whether for a grade, for admissions, or for a scholarship essay.

- However, if you're writing an essay for a timed exam, it's okay if you don't have enough time to combine multiple drafts before the time runs out.

Condensing Your Essay

- So, if you’re writing about Death of a Salesman , an article about symbolism in Arthur Miller’s plays would be useful. But, an article about the average cost of Midwestern hotels in the 1940s would be irrelevant.

- If you’re writing a scholarship essay, double-check the instructions to clarify what types of sources you’re allowed to use.

- A common cliche you might find in an essay is a statement like, "I'm the hardest working student at my school."

- For example, this sentence is too verbose: “I have been a relentlessly stellar student throughout my entire high school career since I am a seriously dedicated reader and thoroughly apply myself to every assignment I receive in class.”

- Shortened, it could read: “I was a stellar student throughout my high school career since I was a dedicated reader and applied myself to every assignment I received.”

- Avoid writing something like, “Willie Loman can be seen as having achieved little through his life because he is not respected by his sons and is not valued by his co-workers.”

- Instead, write, “Arthur Miller shows readers that Willie’s life accomplishments have amounted to little. Willie’s sons do not look up to him, and his co-workers treat him without respect.”

- For example, if you’re trying to prove that WWII pulled the USA out of the Great Depression, focus strictly on an economic argument.

- Avoid bringing in other, less convincing topics. For example, don’t dedicate a paragraph to discussing how much it cost the USA to build fighter jets in 1944.

Short Essay Template and Example

Expert Q&A

- When composing the text of your essay, resist the temptation to pull words from a thesaurus in an attempt to sound academic or intelligent. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If your high school or college has an online or in-person writing center, schedule an appointment. Taking advantage of this type of service can improve your essay and help you recognize structural or grammatical problems you would not have noticed otherwise. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/choosing_a_topic.html

- ↑ https://monroecollege.libguides.com/c.php?g=589208&p=4072926

- ↑ https://www.utep.edu/extendeduniversity/utepconnect/blog/march-2017/4-ways-to-differentiate-a-good-source-from-a-bad-source.html

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/essay-outline/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/thesis-statements/

- ↑ https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-an-essay/essay-introduction

- ↑ https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/undergraduates/writing-guides/how-do-i-write-an-intro--conclusion----body-paragraph.html

- ↑ https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/writingsuccess/chapter/8-3-drafting/

- ↑ https://www.trentu.ca/academicskills/how-guides/how-write-university/how-approach-any-assignment/writing-english-essay/using-secondary

- ↑ https://patch.com/michigan/berkley/bp--how-to-shorten-your-college-essay-without-ruining-it

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/style/ccs_activevoice/

- ↑ https://wordcounter.net/blog/2016/01/26/101025_how-to-reduce-essay-word-count.html

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

D. L. Smith

Sep 9, 2019

Did this article help you?

Aug 15, 2023

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 29, 2023

How to Write a Short Story in 9 Simple Steps

This post is written by UK writer Robert Grossmith. His short stories have been widely anthologized, including in The Time Out Book of London Short Stories , The Best of Best Short Stories , and The Penguin Book of First World War Stories . You can collaborate with him on your own short stories here on Reedsy .

The joy of writing short stories is, in many ways, tied to its limitations. Developing characters, conflict, and a premise within a few pages is a thrilling challenge that many writers relish — even after they've "graduated" to long-form fiction.

In this article, I’ll take you through the process of writing a short story, from idea conception to the final draft.

How to write a short story:

1. Know what a short story is versus a novel

2. pick a simple, central premise, 3. build a small but distinct cast of characters, 4. begin writing close to the end, 5. shut out your internal editor, 6. finish the first draft, 7. edit the short story, 8. share the story with beta readers, 9. submit the short story to publications.

But first, let’s talk about what makes a short story different from a novel.

The simple answer to this question, of course, is that the short story is shorter than the novel, usually coming in at between, say, 1,000-15,000 words. Any shorter and you’re into flash fiction territory. Any longer and you’re approaching novella length .

As far as other features are concerned, it’s easier to define the short story by what it lacks compared to the novel . For example, the short story usually has:

- fewer characters than a novel

- a single point of view, either first person or third person

- a single storyline without subplots

- less in the way of back story or exposition than a novel

If backstory is needed at all, it should come late in the story and be kept to a minimum.

It’s worth remembering too that some of the best short stories consist of a single dramatic episode in the form of a vignette or epiphany.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

A short story can begin life in all sorts of ways.

It may be suggested by a simple but powerful image that imprints itself on the mind. It may derive from the contemplation of a particular character type — someone you know perhaps — that you’re keen to understand and explore. It may arise out of a memorable incident in your own life.

For example:

- Kafka began “The Metamorphosis” with the intuition that a premise in which the protagonist wakes one morning to find he’s been transformed into a giant insect would allow him to explore questions about human relationships and the human condition.

- Herman Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” takes the basic idea of a lowly clerk who decides he will no longer do anything he doesn’t personally wish to do, and turns it into a multi-layered tale capable of a variety of interpretations.

When I look back on some of my own short stories, I find a similar dynamic at work: a simple originating idea slowly expands to become something more nuanced and less formulaic.

So how do you find this “first heartbeat” of your own short story? Here are several ways to do so.

Experiment with writing prompts

Eagle-eyed readers will notice that the story premises mentioned above actually have a great deal in common with writing prompts like the ones put forward each week in Reedsy’s short story competition . Try it out! These prompts are often themed in a way that’s designed to narrow the focus for the writer so that one isn’t confronted with a completely blank canvas.

Turn to the originals

Take a story or novel you admire and think about how you might rework it, changing a key element. (“Pride and Prejudice and Vampires” is perhaps an extreme product of this exercise.) It doesn’t matter that your proposed reworking will probably never amount to more than a skimpy mental reimagining — it may well throw up collateral narrative possibilities along the way.

Keep a notebook

Finally, keep a notebook in which to jot down stray observations and story ideas whenever they occur to you. Again, most of what you write will be stuff you never return to, and it may even fail to make sense when you reread it. But lurking among the dross may be that one rough diamond that makes all the rest worthwhile.

Like I mentioned earlier, short stories usually contain far fewer characters than novels. Readers also need to know far less about the characters in a short story than we do in a novel (sometimes it’s the lack of information about a particular character in a story that adds to the mystery surrounding them, making them more compelling).

Yet it remains the case that creating memorable characters should be one of your principal goals. Think of your own family, friends and colleagues. Do you ever get them confused with one another? Probably not.

Your dramatis personae should be just as easily distinguishable from one another, either through their appearance, behavior, speech patterns, or some other unique trait. If you find yourself struggling, a character profile template like the one you can download for free below is particularly helpful in this stage of writing.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

- “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman features a cast of two: the narrator and her husband. How does Gilman give her narrator uniquely identifying features?

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe features a cast of three: the narrator, the old man, and the police. How does Poe use speech patterns in dialogue and within the text itself to convey important information about the narrator?

- “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor is perhaps an exception: its cast of characters amounts to a whopping (for a short story) nine. How does she introduce each character? In what way does she make each character, in particular The Misfit, distinct?

He’s right: avoid the preliminary exposition or extended scene-setting. Begin your story by plunging straight into the heart of the action. What most readers want from a story is drama and conflict, and this is often best achieved by beginning in media res . You have no time to waste in a short story. The first sentence of your story is crucial, and needs to grab the reader’s attention to make them want to read on.

One way to do this is to write an opening sentence that makes the reader ask questions. For example, Kingsley Amis once said, tongue-in-cheek, that in the future he would only read novels that began with the words: “A shot rang out.”

This simple sentence is actually quite telling. It introduces the stakes: there’s an immediate element of physical danger, and therefore jeopardy for someone. But it also raises questions that the reader will want answered. Who fired the shot? Who or what were they aiming at, and why? Where is this happening?

We read fiction for the most part to get answers to questions. For example, if you begin your story with a character who behaves in an unexpected way, the reader will want to know why he or she is behaving like this. What motivates their unusual behavior? Do they know that what they’re doing or saying is odd? Do they perhaps have something to hide? Can we trust this character?

As the author, you can answer these questions later (that is, answer them dramatically rather than through exposition). But since we’re speaking of the beginning of a story, at the moment it’s enough simply to deliver an opening sentence that piques the reader’s curiosity, raises questions, and keeps them reading.

“Anything goes” should be your maxim when embarking on your first draft.

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

By that, I mean: kill the editor in your head and give your imagination free rein. Remember, you’re beginning with a blank page. Anything you put down will be an improvement on what’s currently there, which is nothing. And there’s a prescription for any obstacle you might encounter at this stage of writing.

- Worried that you’re overwriting? Don’t worry. It’s easier to cut material in later drafts once you’ve sketched out the whole story.

- Got stuck, but know what happens later? Leave a gap. There’s no necessity to write the story sequentially. You can always come back and fill in the gap once the rest of the story is complete.

- Have a half-developed scene that’s hard for you to get onto the page? Write it in note form for the time being. You might find that it relieves the pressure of having to write in complete sentences from the get-go.

Most of my stories were begun with no idea of their eventual destination, but merely an approximate direction of travel. To put it another way, I’m a ‘pantser’ (flying by the seat of my pants, making it up as I go along) rather than a planner. There is, of course, no right way to write your first draft. What matters is that you have a first draft on your hands at the end of the day.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the ending of a short story : it can rescue an inferior story or ruin an otherwise superior one.

If you’re a planner, you will already know the broad outlines of the ending. If you’re a pantser like me, you won’t — though you’ll hope that a number of possible endings will have occurred to you in the course of writing and rewriting the story!

In both cases, keep in mind that what you’re after is an ending that’s true to the internal logic of the story without being obvious or predictable. What you want to avoid is an ending that evokes one of two reactions:

- “Is that it?” aka “The author has failed to resolve the questions raised by the story.”

- “WTF!” aka “This ending is simply confusing.”

Like Truman Capote said, “Good writing is rewriting.”

Once you have a first draft, the real work begins. This is when you move things around, tightening the nuts and bolts of the piece to make sure it holds together and resembles the shape it took in your mind when you first conceived it.

In most cases, this means reading through your first draft again (and again). In this stage of editing , think to yourself:

- Which narrative threads are already in place?

- Which may need to be added or developed further?

- Which need to perhaps be eliminated altogether?

All that’s left afterward is the final polish . Here’s where you interrogate every word, every sentence, to make sure it’s earned its place in the story:

- Is that really what I mean?

- Could I have said that better?

- Have I used that word correctly?

- Is that sentence too long?

- Have I removed any clichés?

Trust me: this can be the most satisfying part of the writing process. The heavy lifting is done, the walls have been painted, the furniture is in place. All you have to do now is hang a few pictures, plump the cushions and put some flowers in a vase.

Eventually, you may reach a point where you’ve reread and rewritten your story so many times that you simply can’t bear to look at it again. If this happens, put the story aside and try to forget about it.

When you do finally return to it, weeks or even months later, you’ll probably be surprised at how the intervening period has allowed you to see the story with a fresh pair of eyes. And whereas it might have felt like removing one of your own internal organs to cut such a sentence or paragraph before, now it feels like a liberation.

The story, you can see, is better as a result. It was only your bloated appendix you removed, not a vital organ.

It’s at this point that you should call on the services of beta readers if you have them. This can be a daunting prospect: what if the response is less enthusiastic than you’re hoping for? But think about it this way: if you’re expecting complete strangers to read and enjoy your story, then you shouldn’t be afraid of trying it out first on a more sympathetic audience.

This is also why I’d suggest delaying this stage of the writing process until you feel sure your story is complete. It’s one thing to ask a friend to read and comment on your new story. It’s quite another thing to return to them sometime later with, “I’ve made some changes to the story — would you mind reading it again?”

So how do you know your story’s really finished? This is a question that people have put to me. My reply tends to be: I know the story’s finished when I can’t see how to make it any better.

This is when you can finally put down your pencil (or keyboard), rest content with your work for a few days, then submit it so that people can read your work. And you can start with this directory of literary magazines once you're at this step.

The truth is, in my experience, there’s actually no such thing as a final draft. Even after you’ve submitted your story somewhere — and even if you’re lucky enough to have it accepted — there will probably be the odd word here or there that you’d like to change.

Don’t worry about this. Large-scale changes are probably out of the question at this stage, but a sympathetic editor should be willing to implement any small changes right up to the time of publication.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your short stories to life

Fuse character, story, and conflict with tools in the Reedsy Book Editor. 100% free.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

25 Great Nonfiction Essays You Can Read Online for Free

Alison Doherty

Alison Doherty is a writing teacher and part time assistant professor living in Brooklyn, New York. She has an MFA from The New School in writing for children and teenagers. She loves writing about books on the Internet, listening to audiobooks on the subway, and reading anything with a twisty plot or a happily ever after.

View All posts by Alison Doherty

I love reading books of nonfiction essays and memoirs , but sometimes have a hard time committing to a whole book. This is especially true if I don’t know the author. But reading nonfiction essays online is a quick way to learn which authors you like. Also, reading nonfiction essays can help you learn more about different topics and experiences.

Besides essays on Book Riot, I love looking for essays on The New Yorker , The Atlantic , The Rumpus , and Electric Literature . But there are great nonfiction essays available for free all over the Internet. From contemporary to classic writers and personal essays to researched ones—here are 25 of my favorite nonfiction essays you can read today.

“Beware of Feminist Lite” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The author of We Should All Be Feminists writes a short essay explaining the danger of believing men and woman are equal only under certain conditions.

“It’s Silly to Be Frightened of Being Dead” by Diana Athill

A 96-year-old woman discusses her shifting attitude towards death from her childhood in the 1920s when death was a taboo subject, to World War 2 until the present day.

“Letter from a Region in my Mind” by James Baldwin

There are many moving and important essays by James Baldwin . This one uses the lens of religion to explore the Black American experience and sexuality. Baldwin describes his move from being a teenage preacher to not believing in god. Then he recounts his meeting with the prominent Nation of Islam member Elijah Muhammad.

“Relations” by Eula Biss

Biss uses the story of a white woman giving birth to a Black baby that was mistakenly implanted during a fertility treatment to explore racial identities and segregation in society as a whole and in her own interracial family.

“Friday Night Lights” by Buzz Bissinger

A comprehensive deep dive into the world of high school football in a small West Texas town.

“The Case for Reparations” by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Coates examines the lingering and continuing affects of slavery on American society and makes a compelling case for the descendants of slaves being offered reparations from the government.

“Why I Write” by Joan Didion

This is one of the most iconic nonfiction essays about writing. Didion describes the reasons she became a writer, her process, and her journey to doing what she loves professionally.

“Go Gentle Into That Good Night” by Roger Ebert

With knowledge of his own death, the famous film critic ponders questions of mortality while also giving readers a pep talk for how to embrace life fully.

“My Mother’s Tongue” by Zavi Kang Engles

In this personal essay, Engles celebrates the close relationship she had with her mother and laments losing her Korean fluency.

“My Life as an Heiress” by Nora Ephron

As she’s writing an important script, Ephron imagines her life as a newly wealthy woman when she finds out an uncle left her an inheritance. But she doesn’t know exactly what that inheritance is.

“My FatheR Spent 30 Years in Prison. Now He’s Out.” by Ashley C. Ford

Ford describes the experience of getting to know her father after he’s been in prison for almost all of her life. Bridging the distance in their knowledge of technology becomes a significant—and at times humorous—step in rebuilding their relationship.

“Bad Feminist” by Roxane Gay

There’s a reason Gay named her bestselling essay collection after this story. It’s a witty, sharp, and relatable look at what it means to call yourself a feminist.

“The Empathy Exams” by Leslie Jamison

Jamison discusses her job as a medical actor helping to train medical students to improve their empathy and uses this frame to tell the story of one winter in college when she had an abortion and heart surgery.

“What I Learned from a Fitting Room Disaster About Clothes and Life” by Scaachi Koul

One woman describes her history with difficult fitting room experiences culminating in one catastrophe that will change the way she hopes to identify herself through clothes.

“Breasts: the Odd Couple” by Una LaMarche

LaMarche examines her changing feelings about her own differently sized breasts.

“How I Broke, and Botched, the Brandon Teena Story” by Donna Minkowitz

A journalist looks back at her own biased reporting on a news story about the sexual assault and murder of a trans man in 1993. Minkowitz examines how ideas of gender and sexuality have changed since she reported the story, along with how her own lesbian identity influenced her opinions about the crime.

“Politics and the English Language” by George Orwell

In this famous essay, Orwell bemoans how politics have corrupted the English language by making it more vague, confusing, and boring.

“Letting Go” by David Sedaris

The famously funny personal essay author , writes about a distinctly unfunny topic of tobacco addiction and his own journey as a smoker. It is (predictably) hilarious.

“Joy” by Zadie Smith

Smith explores the difference between pleasure and joy by closely examining moments of both, including eating a delicious egg sandwich, taking drugs at a concert, and falling in love.

“Mother Tongue” by Amy Tan

Tan tells the story of how her mother’s way of speaking English as an immigrant from China changed the way people viewed her intelligence.

“Consider the Lobster” by David Foster Wallace

The prolific nonfiction essay and fiction writer travels to the Maine Lobster Festival to write a piece for Gourmet Magazine. With his signature footnotes, Wallace turns this experience into a deep exploration on what constitutes consciousness.

“I Am Not Pocahontas” by Elissa Washuta

Washuta looks at her own contemporary Native American identity through the lens of stereotypical depictions from 1990s films.

“Once More to the Lake” by E.B. White

E.B. White didn’t just write books like Charlotte’s Web and The Elements of Style . He also was a brilliant essayist. This nature essay explores the theme of fatherhood against the backdrop of a lake within the forests of Maine.

“Pell-Mell” by Tom Wolfe

The inventor of “new journalism” writes about the creation of an American idea by telling the story of Thomas Jefferson snubbing a European Ambassador.

“The Death of the Moth” by Virginia Woolf

In this nonfiction essay, Wolf describes a moth dying on her window pane. She uses the story as a way to ruminate on the lager theme of the meaning of life and death.

You Might Also Like

The short story is a fiction writer’s laboratory: here is where you can experiment with characters, plots, and ideas without the heavy lifting of writing a novel. Learning how to write a short story is essential to mastering the art of storytelling . With far fewer words to worry about, storytellers can make many more mistakes—and strokes of genius!—through experimentation and the fun of fiction writing.

Nonetheless, the art of writing short stories is not easy to master. How do you tell a complete story in so few words? What does a story need to have in order to be successful? Whether you’re struggling with how to write a short story outline, or how to fully develop a character in so few words, this guide is your starting point.

Famous authors like Virginia Woolf, Haruki Murakami, and Agatha Christie have used the short story form to play with ideas before turning those stories into novels. Whether you want to master the elements of fiction, experiment with novel ideas, or simply have fun with storytelling, here’s everything you need on how to write a short story step by step.

How to Write a Short Story: Contents

The Core Elements of a Short Story

How to write a short story outline, how to write a short story step by step, how to write a short story: length and setting, how to write a short story: point of view, how to write a short story: protagonist, antagonist, motivation, how to write a short story: characters, how to write a short story: prose, how to write a short story: story structure, how to write a short story: capturing reader interest, where to read and submit short stories.

There’s no secret formula to writing a short story. However, a good short story will have most or all of the following elements:

- A protagonist with a certain desire or need. It is essential for the protagonist to want something they don’t have, otherwise they will not drive the story forward.

- A clear dilemma. We don’t need much backstory to see how the dilemma started; we’re primarily concerned with how the protagonist resolves it.

- A decision. What does the protagonist do to resolve their dilemma?

- A climax. In Freytag’s Pyramid , the climax of a story is when the tension reaches its peak, and the reader discovers the outcome of the protagonist’s decision(s).

- An outcome. How does the climax change the protagonist? Are they a different person? Do they have a different philosophy or outlook on life?

Of course, short stories also utilize the elements of fiction , such as a setting , plot , and point of view . It helps to study these elements and to understand their intricacies. But, when it comes to laying down the skeleton of a short story, the above elements are what you need to get started.

Note: a short story rarely, if ever, has subplots. The focus should be entirely on a single, central storyline. Subplots will either pull focus away from the main story, or else push the story into the territory of novellas and novels.

The shorter the story is, the fewer of these elements are essentials. If you’re interested in writing short-short stories, check out our guide on how to write flash fiction .

Some writers are “pantsers”—they “write by the seat of their pants,” making things up on the go with little more than an idea for a story. Other writers are “plotters,” meaning they decide the story’s structure in advance of writing it.

You don’t need a short story outline to write a good short story. But, if you’d like to give yourself some scaffolding before putting words on the page, this article answers the question of how to write a short story outline:

https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-story-outline

There are many ways to approach the short story craft, but this method is tried-and-tested for writers of all levels. Here’s how to write a short story step-by-step.

1. Start With an Idea

Often, generating an idea is the hardest part. You want to write, but what will you write about?

What’s more, it’s easy to start coming up with ideas and then dismissing them. You want to tell an authentic, original story, but everything you come up with has already been written, it seems.

Here are a few tips:

- Originality presents itself in your storytelling, not in your ideas. For example, the premise of both Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Ostrovsky’s The Snow Maiden are very similar: two men and two women, in intertwining love triangles, sort out their feelings for each other amidst mischievous forest spirits, love potions, and friendship drama. The way each story is written makes them very distinct from one another, to the point where, unless it’s pointed out to you, you might not even notice the similarities.

- An idea is not a final draft. You will find that exploring the possibilities of your story will generate something far different than the idea you started out with. This is a good thing—it means you made the story your own!

- Experiment with genres and tropes. Even if you want to write literary fiction , pay attention to the narrative structures that drive genre stories, and practice your storytelling using those structures. Again, you will naturally make the story your own simply by playing with ideas.

If you’re struggling simply to find ideas, try out this prompt generator , or pull prompts from this Twitter .

2. Outline, OR Conceive Your Characters

If you plan to outline, do so once you’ve generated an idea. You can learn about how to write a short story outline earlier in this article.

If you don’t plan to outline, you should at least start with a character or characters. Certainly, you need a protagonist, but you should also think about any characters that aid or inhibit your protagonist’s journey.

When thinking about character development, ask the following questions:

- What is my character’s background? Where do they come from, how did they get here, where do they want to be?

- What does your character desire the most? This can be both material or conceptual, like “fitting in” or “being loved.”

- What is your character’s fatal flaw? In other words, what limitation prevents the protagonist from achieving their desire? Often, this flaw is a blind spot that directly counters their desire. For example, self hatred stands in the way of a protagonist searching for love.

- How does your character think and speak? Think of examples, both fictional and in the real world, who might resemble your character.

In short stories, there are rarely more characters than a protagonist, an antagonist (if relevant), and a small group of supporting characters. The more characters you include, the longer your story will be. Focus on making only one or two characters complex: it is absolutely okay to have the rest of the cast be flat characters that move the story along.

Learn more about character development here:

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

3. Write Scenes Around Conflict

Once you have an outline or some characters, start building scenes around conflict. Every part of your story, including the opening sentence, should in some way relate to the protagonist’s conflict.

Conflict is the lifeblood of storytelling: without it, the reader doesn’t have a clear reason to keep reading. Loveable characters are not enough, as the story has to give the reader something to root for.

Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s classic short story The Cask of Amontillado . We start at the conflict: the narrator has been slighted by Fortunato, and plans to exact revenge. Every scene in the story builds tension and follows the protagonist as he exacts this revenge.

In your story, start writing scenes around conflict, and make sure each paragraph and piece of dialogue relates, in some way, to your protagonist’s unmet desires.

Read more about writing effective conflict here:

What is Conflict in a Story? Definition and Examples

4. Write Your First Draft

The scenes you build around conflict will eventually be stitched into a complete story. Make sure as the story progresses that each scene heightens the story’s tension, and that this tension remains unbroken until the climax resolves whether or not your protagonist meets their desires.

Don’t stress too hard on writing a perfect story. Rather, take Anne Lamott’s advice, and “write a shitty first draft.” The goal is not to pen a complete story at first draft; rather, it’s to set ideas down on paper. You are simply, as Shannon Hale suggests, “shoveling sand into a box so that later [you] can build castles.”

5. Step Away, Breathe, Revise

Whenever Stephen King finishes a novel, he puts it in a drawer and doesn’t think about it for 6 weeks. With short stories, you probably don’t need to take as long of a break. But, the idea itself is true: when you’ve finished your first draft, set it aside for a while. Let yourself come back to the story with fresh eyes, so that you can confidently revise, revise, revise .

In revision, you want to make sure each word has an essential place in the story, that each scene ramps up tension, and that each character is clearly defined. The culmination of these elements allows a story to explore complex themes and ideas, giving the reader something to think about after the story has ended.

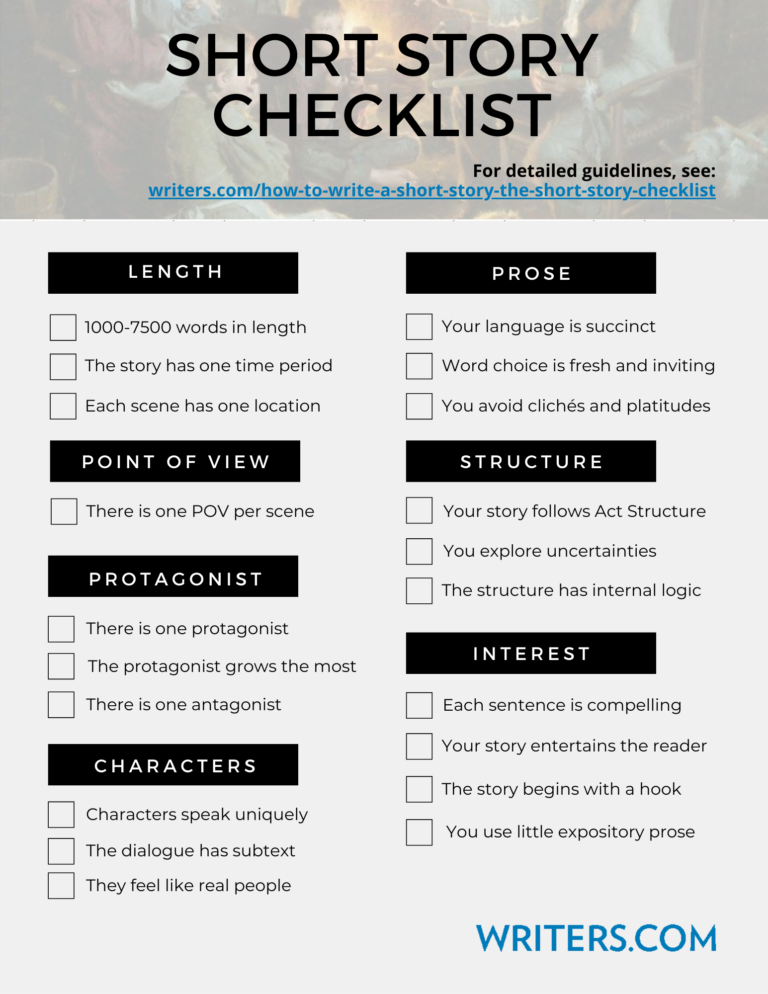

6. Compare Against Our Short Story Checklist

Does your story have everything it needs to succeed? Compare it against this short story checklist, as written by our instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko.

Below is a collection of practical short story writing tips by Writers.com instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko . Each paragraph is its own checklist item: a core element of short story writing advice to follow unless you have clear reasons to the contrary. We hope it’s a helpful resource in your own writing.

Update 9/1/2020: We’ve now made a summary of Rosemary’s short story checklist available as a PDF download . Enjoy!

Click to download

Your short story is 1000 to 7500 words in length.

The story takes place in one time period, not spread out or with gaps other than to drive someplace, sleep, etc. If there are those gaps, there is a space between the paragraphs, the new paragraph beginning flush left, to indicate a new scene.

Each scene takes place in one location, or in continual transit, such as driving a truck or flying in a plane.

Unless it’s a very lengthy Romance story, in which there may be two Point of View (POV) characters, there is one POV character. If we are told what any character secretly thinks, it will only be the POV character. The degree to which we are privy to the unexpressed thoughts, memories and hopes of the POV character remains consistent throughout the story.

You avoid head-hopping by only having one POV character per scene, even in a Romance. You avoid straying into even brief moments of telling us what other characters think other than the POV character. You use words like “apparently,” “obviously,” or “supposedly” to suggest how non-POV-characters think rather than stating it.

Your short story has one clear protagonist who is usually the character changing most.

Your story has a clear antagonist, who generally makes the protagonist change by thwarting his goals.

(Possible exception to the two short story writing tips above: In some types of Mystery and Action stories, particularly in a series, etc., the protagonist doesn’t necessarily grow personally, but instead his change relates to understanding the antagonist enough to arrest or kill him.)

The protagonist changes with an Arc arising out of how he is stuck in his Flaw at the beginning of the story, which makes the reader bond with him as a human, and feel the pain of his problems he causes himself. (Or if it’s the non-personal growth type plot: he’s presented at the beginning of the story with a high-stakes problem that requires him to prevent or punish a crime.)

The protagonist usually is shown to Want something, because that’s what people normally do, defining their personalities and behavior patterns, pushing them onward from day to day. This may be obvious from the beginning of the story, though it may not become heightened until the Inciting Incident , which happens near the beginning of Act 1. The Want is usually something the reader sort of wants the character to succeed in, while at the same time, knows the Want is not in his authentic best interests. This mixed feeling in the reader creates tension.

The protagonist is usually shown to Need something valid and beneficial, but at first, he doesn’t recognize it, admit it, honor it, integrate it with his Want, or let the Want go so he can achieve the Need instead. Ideally, the Want and Need can be combined in a satisfying way toward the end for the sake of continuity of forward momentum of victoriously achieving the goals set out from the beginning. It’s the encounters with the antagonist that forcibly teach the protagonist to prioritize his Needs correctly and overcome his Flaw so he can defeat the obstacles put in his path.

The protagonist in a personal growth plot needs to change his Flaw/Want but like most people, doesn’t automatically do that when faced with the problem. He tries the easy way, which doesn’t work. Only when the Crisis takes him to a low point does he boldly change enough to become victorious over himself and the external situation. What he learns becomes the Theme.

Each scene shows its main character’s goal at its beginning, which aligns in a significant way with the protagonist’s overall goal for the story. The scene has a “charge,” showing either progress toward the goal or regression away from the goal by the ending. Most scenes end with a negative charge, because a story is about not obtaining one’s goals easily, until the end, in which the scene/s end with a positive charge.

The protagonist’s goal of the story becomes triggered until the Inciting Incident near the beginning, when something happens to shake up his life. This is the only major thing in the story that is allowed to be a random event that occurs to him.

Your characters speak differently from one another, and their dialogue suggests subtext, what they are really thinking but not saying: subtle passive-aggressive jibes, their underlying emotions, etc.

Your characters are not illustrative of ideas and beliefs you are pushing for, but come across as real people.