Case Study: The Collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Its Global Impact

“The downfall of SVB has left investors and depositors scrambling, as the domino effect threatens the stability of the global financial system.”

Introduction

The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is one of the leading U.S. banks in the fintech space, and its collapse has created an aftershock effect throughout the global financial system. Investors and depositors have uncertainties about the situation as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) intervenes to take control of the bank in question. In this article, we will analyze the international impact of SVB’s downfall on depositors, the financial markets, cryptocurrencies, and other banks.

Why Does It Matter?

As Emil Åkesson, Chairman and President of CLC & Partners, stated in his article on nasdaq.com , “ If things are bad in the U.S., things are bad all over. ” If the SVB issue is not addressed properly, it can lead to greater global problems with a domino effect.

Silicon Valley Bank is distinguished as being a strong stakeholder that serves tech startups, life science and healthcare companies, private equity firms, and venture capital funds. SVB stands out holding the 16th position amongst the largest banks in the U.S. with 4,100+ banks operating all over the country. Its collapse has sent shockwaves throughout the global markets and also raised concerns about the future of fintech, technology startups, and innovation in the U.S. economy.

Before its breakdown, SVB’s holdings and assets were valued around at $210 billion, with $175 billion in deposits. Although this may seem like a small fraction of the total U.S. bank deposits of $18 trillion, it’s important to note that nearly $6 trillion of those deposits are held in small banks. In addition, SVB falls into the category of large banks, with its size and efficacy in the fintech industry being significant factors. In fact, this is the largest bank failure in the U.S. since 2008 Washington Mutual Bank failure.

The impact of SVB’s breakdown extends beyond its immediate clients. As the primary financial supporter of technology startups and venture capital funds, SVB’s failure could hinder the growth and development of future tech giants like Apple, Google, and Tesla in their early days. These startups rely on funding from various sources, especially venture capital firms. SVB plays a critical and central role in this ecosystem by providing commercial banking services to these companies and funds, fueling the technological innovation that has made the U.S. a global powerhouse. Therefore, it is essential for the U.S. to serve a safe and sound banking system to secure its position in the technology race.

Approximately, 29% of SVB’s deposits belong to technology startups and companies, potentially putting the next generation of industry-disrupting ideas at risk. The collapse of SVB is not only a financial crisis but also a potential innovation catastrophe. As these tech startups and venture capital funds search for new banking partners and possible financing opportunities, the U.S. must address the reverberations of SVB’s breakdown to preserve its status as a leader in innovation and prevent a possible slowdown in the growth of its tech sector.

How Did SVB Get Here?

We can trace the roots of SVB’s collapse back to 2022, when the U.S. raised interest rates to combat inflation, successfully lowering the inflation from 9% to 6% and aiming to further reduce it to 4%. As interest rates increased, the availability of capital diminished. SVB and similar banks had been providing cash flow to startups, with investors channeling their money into venture capital funds to support these projects. The startups would then use the funds to grow and eventually repay their debts. If these startups succeeded, the venture capital funds would generate substantial returns for their investors, despite the high risk.

However, the interest rates started to rise in 2022, and investors shifted their attention to low-risk deposits and bonds with higher yields which led to difficulties for venture capital funds in raising capital. Consequently, startups encountered challenges in securing funds and even struggled to pay their employees’ salaries. With the decrease in fundraising traffic, startups had to dip into their SVB bank accounts to cover these expenses, causing SVB’s total deposits to shrink. Simultaneously, SVB’s investments and shares in these sectors suffered as the startups and tech companies could no longer grow.

SVB held the top position in the Q4 of 2022 with 55.4% of their total funds invested. The bank’s deposit funding predominantly consisted of early tech startups and tech companies, providing them with fundraising by acquiring shares and receiving interest payments in return. Both investors and companies held their money in SVB, which the bank then used to make risky investments in more startups. However, with an investment-to-holding ratio of over 55%, SVB’s exposure was a very high and unorthodox one.

Ultimately, SVB failed to accurately assess the risks associated with their investments in these startups given rising interest rates. While it may not be fair to label this approach as inherently flawed, the uncontrolled inflation rate necessitated an increase in the interest rates, which proved to be the tipping point. In the end, SVB found itself unable to repay the $175 billion in deposits. The following day, SVB experienced a bank run and panicked customers withdrew $42 billion from SVB. To cover the shortfall, the bank attempted to sell its shares in tech startups and companies which led to a significant drop in their value and intensified the crisis.

The Bond Backlash

A sudden surge in interest rates can create a chain of events that sends shockwaves throughout the financial landscape, shaking the very foundation of previously issued bonds. The allure of new bonds, offering higher returns in the wake of rising interest rates, leads investors to flee for safer havens with high returns, outshining the older bonds with lower yields. As a result, bondholders seeking to sell their older bonds must reduce the prices to compete with the more appealing new bonds and this eventually leads to a capital loss.

Banks generally tend to have big holdings of government bonds that they can easily liquidate in times of crisis. Unfortunately, SVB had made considerable investments in long-term bonds when the interest rates were much lower than they are now. When the U.S. aggressively raised interest rates by 4.5%, the market value of SVB’s older long-term bonds experienced a sharp decline. This situation resulted in a $1.8 billion loss in the market value of their bond investment for SVB. These consecutive events dealt a double blow to the bank, ultimately contributing to SVB’s collapse.

The FDIC and Depositor Insurance

In the United States, the deposits are insured up to at least $250,000 per depositor in the FDIC-insured banks providing a safety net for depositors in case of bank failures. However, this limit has become a discussion topic with the SVB case.

SVB’s Q4 2022 data revealed that only 2.7% of its account holders had deposits below $250,000, which means 97.3% of the depositors had uninsured amounts exceeding the FDIC limit. These uninsured deposits are at risk of being lost, amounting to over $150 billion.

- The Existentialists : People made their own decisions and therefore should face the consequences of their own choices.

- The Concerned : If the FDIC and the government don’t intervene, it could lead to a much bigger financial crisis, affecting everyone on a global scale.

SVB, Stocks, and Commodities

SVB’s collapse has had a significant impact on global markets, with financial stocks losing $465 billion in market value in just two days. Gold prices have rallied by up to 10% as investors were seeking a safe haven. With this incident, the U.S. might have failed to fight inflation, at least for a while.

SVB and Cryptocurrencies

The collapse of SVB have had a notable impact on cryptocurrencies, particularly Bitcoin and Ethereum being the safe haven of the crypto market, which have surged in value following the bank’s downfall. Around $100 billion has moved to the crypto market in the following week, making Bitcoin, Ethereum, and altcoins such as Solana and Cardano reach new heights. Investors have been driven away from traditional banking towards the decentralised, leading to Bitcoin reaching a nine-month high.

However, every silver lining has a cloud. USDC, a stablecoin pegged to the U.S. dollar and managed by Circle, serves as a reliable medium of exchange without the volatility of other cryptocurrencies. Circle maintains a one-to-one reserve, holding one dollar for each USDC issued. Of the $40 billion raised from users, Circle invested $32 billion in short-term U.S. government bonds, securing 77% of the funds. The remaining 23%, or $3.3 billion, was held in cash, leaving 8% of USDC’s backing at risk. As a result, the theoretical value of 1 USDC should have dropped to $0.92 at the moment, casting a shadow over the stability of stablecoins.

Following the SVB news, Circle’s delayed response caused USDC’s value to plummet to the $0.8 range. Eventually, Circle announced that they had anticipated the situation and requested SVB to return the funds. U.S. regulators intervened, and USDC’s value returned to normal levels.

Circle has also stated that they are also committed to compensating for any losses if they cannot recover the funds from SVB. While this may not be a significant challenge for Circle, as they earn approximately $1.6 billion in interest annually from their bond investments, the primary issue was their delayed statement. However, Circle should have made this statement earlier to prevent panic selling and financial loss for USDC holders.

Why Blockchain Technology Shines?

While all of these were happening, some of the C-levels of the SVB were selling their shares. Gregory W. Becker, CEO of SVB, sold 11% of his shares on 27th February. Some of them started to sell their shares even more than a month ago starting at the beginning of February. Even though it was publicly available, nobody can blame individuals in a situation where the government itself couldn’t foresee and prevent this from happening. On a legal level, there seems no problem with this, but in terms of ethics, it does not look good, and Greg Becker may have a hard time finding support.

The SVB collapse highlights the advantages of blockchain technology, which offers transparency and traceability. In a centralized banking system, individuals must trust the bank, and tracing transactions can be difficult even for governments. With blockchain, all transactions are transparent and immutable, and warning systems such as Blocknative can be put in place for significant withdrawals like the SVB scandal. If this had occurred on a blockchain-based platform, investors could have been warned earlier when the bank’s C-level executives sold their shares. Unfortunately, the fintech industry has failed in educating the public about these warning system benefits. This highlights the need for improved communication and transparency in the financial industry and as CLC & Partners, we are committed to informing our audience.

The 3S Trio: Silvergate, SVB, and Signature Bank

Silvergate Capital, SVB, and Signature Bank, all facing financial issues, have caused turmoil in the crypto-friendly banking space. The closures of these banks, coupled with regulatory and legal investigations, have made it difficult for crypto companies to rely on traditional banking partners.

What’s Next for SVB and Its Depositors?

A consortium of private equity firms led by The Bank of London has submitted formal proposals to His Majesty’s Treasury to acquire SVB, but it remains uncertain whether the U.S. government will allow such a move due to potential privacy concerns.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has announced that there will be no bailout for SVB. However, Yellen and the FDIC declared that additional funding will be made available to ensure all deposits will be paid in full regardless of the amount. The Fed also plans to provide funding to eligible depository institutions to support depositor needs. It should be noted that this issue should be solved very carefully to avoid providing freedom and relief to the other banks in the U.S. in terms of taking relentless risks with such a remedy.

All in all, the dramatic downfall of Silicon Valley Bank has left far-reaching consequences, affecting investors, depositors, and the global financial system. While the FDIC and the government are stepping in to prevent a total meltdown, it’s essential to monitor the situation closely and learn from this crisis to better prepare for future financial disruptions. As our chairman and president Emil Åkesson says, “history repeats itself, again,” and it will sure do again. A detailed case study like this article will definitely help us to extract valuable lessons to safeguard against future economic disruptions.

The financial world needs a leap forward, and we at CLC & Partners are eager to provide our community with our team’s valuable insights and extensive experiences to help you stay ahead of the curve. Follow CLC Blog to stay tuned and with truth!

CLC Homepage

© 2023 CLC & Partners All Rights Reserved.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR UPCOMING NEWSLETTER

The CLS Blue Sky Blog

Columbia Law School's Blog on Corporations and the Capital Markets

From hero to zero – the case of silicon valley bank.

The sudden collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) surprised many investors and industry experts, given the bank’s recent accolades and long-standing reputation as one of the best national and regional banks in the U.S. [1] Moreover, there had been no reported bank failures during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2022. As the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history, the collapse of SVB has raised many questions about what went wrong and how such a successful institution could fail so unexpectedly.

Banks fail for a variety of reasons, including weak regulation, economic instability, poor corporate governance, and inadequate risk management. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the number of bank failures in the United States increased significantly. In 2010, there were 157 failures, the highest number since the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s and early 1990s. However, since then, the number has steadily declined. One possible reason is the regulatory reforms that were implemented after the financial crisis The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, for example, introduced new regulations to increase capital and liquidity requirements for banks, as well as to enhance risk management practices. Additionally, the overall improvement of the economy and the banking industry’s recovery from the financial crisis have contributed to the decline in bank collapses.

In a recent paper , we investigate the collapse of SVB, analyzing the bank’s financial performance in the period 2019-2022. We show that the bank expanded significantly during that period, with total assets and total deposits tripling and total revenue and net income growing more than two-fold. However, the bank’s financial performance declined during the same period. For example, the average yield on earning assets declined from 3.83 percent in 2019 to 2.77 percent in 2022, which was lower than for its peers. In contrast, the cost of funding earning assets increased from 0.30 percent to 0.55 percent, which was higher than for its peers. Consequently, both return on assets and return on equity decreased during the period.

An analysis of the bank’s balance sheet also reveals some important points. First, the bank’s equity capital ratio was 7.39 percent in 2022, significantly lower than its peers’ ratio of 9.34 percent. Second, the bank’s proportion of loans and leases to total assets dropped from 46.95 percent in 2019 to 35.22 percent in 2022, which was significantly lower than the industry average of 50.98 percent. In contrast, the total debt securities ratio increased from 39.68 percent to 56.12 percent. Third, SVB mainly depended on deposits to finance its assets. Although the deposit-to-total assets ratio decreased from 89.99 percent to 83.90 percent, it was still significantly higher than its peers’ ratio of 81.42 percent. Moreover, more than 94 percent of its deposits were uninsured.

A more detailed analysis of the bank’s financial statements uncovers that in 2021, when interest rates were very low, the bank invested more in debt securities, which accounted for 60.07 percent of total assets. The held-to-maturity (HTM) securities grew six-fold from 2019 to 2021, comprising 47.08 percent of total assets, while the available-for-sale (AFS) securities doubled during this period. At the end of 2021, the weighted average duration of its debt securities was 3.97 years. This figure increased to 5.7 years at the end of 2022, while the weighted average duration of the HTM securities was 6.2 years.

In early 2022, interest rates experienced a significant surge. For example, the yield on three-year Treasury Notes increased significantly from less than 1 percent at the end of 2021 to around 4.20 percent at the end of 2022. As a result of the interest rate hike, SVB was exposed to the risk of unrealized losses of at least $15.76 billion (equivalent to 12.61 percent of its $125 billion debt securities). This could have resulted in a negative market value of the bank’s equity capital by the end of the year. However, since the bank did not sell its securities, most of these potential losses were not realized.

Another weakness of SVB was the lack of diversification in its depositor base, as 89.38 percent of total deposits come from a small group of depositors primarily operating in the venture capital industry. Given the concentration of depositors, there was a higher likelihood that they knew each other. In the event of poor bank performance, there was a greater possibility that many depositors would withdraw their deposits at the same time because most of these deposits were uninsured, thus increasing the risk of a bank run.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank can, therefore, be attributed to several factors. First, SVB invested significantly in debt securities during a low-interest-rate period and did not properly hedge its risks, which resulted in losses after the recent surge in interest rates. Second, SVB had a highly concentrated depositor base, with a small group of depositors providing most of the bank’s funding, and a high proportion of uninsured deposits, increasing the risk of a bank run. Finally, SVB had significantly less equity capital than its peers, which further exacerbated the bank’s risk.

[1] Just a few weeks before SVB’s failure, it was named by Forbes as one of the best American banks based on its impressive growth, credit quality, and profitability.

This post comes to us from professors Lai Van Vo at Western Connecticut State University and Huong Thi Thu Le at Northeastern Illinois University. It is based on their recent article “From Hero to Zero – The Case of Silicon Valley Bank,” available here.

Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University

Finance & Accounting Mar 16, 2023

What went wrong at silicon valley bank, and how can it be avoided next time a new analysis sheds light on vulnerabilities within the u.s. banking industry..

Erica Xuewei Jiang

Gregor Matvos

Tomasz Piskorski

Yevgenia Nayberg

Silicon Valley Bank’s sudden collapse has left finance professionals, economists, and even the Justice Department grappling with where to place blame for the bank’s failure and how to prevent the next bank collapse.

One significant question: Was Silicon Valley Bank an outlier, or are a lot of other U.S. banks similarly vulnerable to a bank run? Gregor Matvos, a finance professor at Kellogg, and his colleagues Erica Xuewei Jiang, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru, recently conducted an analysis that shows the banking sector is more fragile than we might hope.

Kellogg Insight spoke with Matvos about the bank run, his analysis, and what this could mean going forward. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

INSIGHT: Beyond the obvious—too many depositors all got spooked and tried to move their money at once—what happened here? What was the underlying cause?

Gregor MATVOS: In the last year or so, the Federal Reserve increased interest rates, which led to a decline in the value of the holdings of banks, the “asset side” of banks, as we call it. The loans they had made, the bonds they held, decreased in value.

INSIGHT: And why is that?

MATVOS: Well, think of it this way. You buy a government treasury bond two years ago when interest rates are close to zero that will repay over 20 years. Then the government starts issuing new bonds with interest rates at four percent. Obviously, you’d rather have four percent than zero percent. That seems like a no-brainer. Well, if the four percent bond right now costs you $1 to buy, then the bond you bought in the past surely is not worth a dollar anymore. It’s worth less because it’s giving you less interest payments over time. In other words, it declines in value. And the issue for banks is that not only have their securities lost value, but they also didn’t record these losses on the books. They pretended as though the value of these securities was the same as from the time when they issued them.

INSIGHT: Is that allowed?

MATVOS: Recognizing losses in a mark-to-market way has always been a little bit fraught with banks. The recognition of losses tends to be slow. Sometimes that’s okay; sometimes that’s not okay. The interesting question here is that the losses are quite substantial. So, uninsured depositors started getting worried. Imagine I’m one uninsured depositor, and I say, “Well, if all people like me pull out their money, is there going to be enough money left for me?”

Once people started worrying about there not being enough money, well, there may in fact not be enough money, and it makes sense to run. And that’s partly what happened to Silicon Valley Bank.

Now, what was especially interesting about Silicon Valley Bank is that its depositors were a tight-knit community in which the news of potential demise spread even faster than it normally would.

INSIGHT: So was there a specific trigger or did somebody just out of the blue say, “Hey, I think there’s a problem,” and then go tell their 50 best friends?

MATVOS: It’s always very hard to put your finger on a trigger. It was clear that banks were in slightly worse condition. Rumors started swirling, and then enough depositors redeemed that Silicon Valley Bank said, “We had to sell $20 billion of our bonds at a loss.”

I think that was actually a misstatement. They didn’t sell them at a loss, they sold them at market price. They just now finally had to acknowledge that the assets had lost value, which prior to that they had not done.

INSIGHT: Let’s talk about all these uninsured deposits. This would be any deposit over $250,000. So is the ideal scenario, then, for firms to just have 50 bank accounts so none go over $250,000?

MATVOS: Well, you want to think a little bit about who would have an uninsured deposit account, right? It could be a depositor who hasn’t really paid attention to where their salary is going, and more than $250,000 accumulates. Let’s call them “sleepy individual investors.” They quickly can readjust, and maybe send money to two banks or put money in Treasuries. For them, the deposits are a way of saving.

Another set of uninsured depositors would be something like charities or small businesses: You have to make payroll. It’ll be quite inconvenient to have your payroll spread across 50 banks. So you have one account with one bank, and you run your payroll through there, and you probably get your loan through there, and all the other services. It’s super convenient, and most of the time you really don’t have to worry about it. So we shouldn’t be that surprised that there’s uninsured deposits, because it’s practical for small businesses, charities, and so on to keep more than $250,000 in one place.

[SVB’s] still an outlier, but there are plenty of other banks, 186 to be precise, that sure look like they could be subject to a run. — Gregor Matvos

And if the banks have a big enough equity cushion—imagine that Silicon Valley Bank had been funded 20 percent through equity instead of 10 percent through equity—you can lose a lot of value and still not worry about deposits ever being impaired. But U.S. banks don’t do that. U.S. banks have more like 10 percent equity funding. That means that if asset values do decline, then all of a sudden, there’s a problem.

INSIGHT: In your analysis, you looked at whether Silicon Valley Bank is a complete outlier or emblematic of something broader. Can you tell us a little bit about your analysis?

MATVOS: We looked at data from all banks in the U.S. We first asked: These hidden losses, are they big? Are they small? Is Silicon Valley an exception? And we found that for the average U.S. bank, losses haven’t been mark-to-market on the order of 10 percent of their assets, which is substantial if you think that equity is about 10 percent of the assets.

So we said, okay, suppose Silicon Valley Bank defaulted just because of losses. How many other banks would default? Well, we find many would. In other words, Silicon Valley Bank wasn’t a particularly big outlier on asset losses.

It also wasn’t an outlier from the perspective of how much equity capital it had. Where it was really an outlier was in “uninsured leverage.” In other words, when it funded itself, it funded itself a lot with uninsured deposits. So it was a combination of losses and uninsured deposits that triggered a run. If you just had losses and not uninsured deposits, you’d probably be fine. If you just had uninsured deposits and no losses—which was pretty much the case for Silicon Valley Bank two years ago—you’d be fine. But having both losses and many uninsured deposits, well, they were not fine.

INSIGHT: You also looked at how many banks—through a combination of the above factors—would be vulnerable to a bank run. What did you find?

MATVOS: The way we try to evaluate who would be at risk of a run is we said, “Imagine that half of these uninsured depositors wake up and freak out. Like, ‘Oh my God, I don’t know what’s going to happen. Maybe I should pull out my money.’ And then you have to repay them. Is there enough money to repay the insured depositors so that FDIC won’t have to step in?” And we find that there are about 190 banks for whom if half the people ran, the bank would get shut down, and the other people who didn’t run would lose everything. So the incentives to run there would be enormous.

Now the FDIC should generally only protect insured deposits, which is why we factored that into our analysis. It now seems, because of the issues in the banking sector, that the government will guarantee all deposits. So there is no reason to run, because the FDIC will stand behind all deposits.

INSIGHT: So to recap, Silicon Valley Bank is pretty unique because it’s catering to these large Silicon Valley companies and is largely funded via uninsured deposits. But when you look holistically at its vulnerability to a bank run, it’s actually not as much of an outlier as we would want.

MATVOS: It’s still an outlier, but there are plenty of other banks, 186 to be precise, that sure look like they could be subject to a run.

INSIGHT: So that’s about five percent of the banks in America.

MATVOS: Yes. And we were trying to be fairly conservative. So, for example, we assumed that if people ran on the bank, you could sell the assets at zero discount, which we know doesn’t happen. But we said, okay, let’s try to give the banks a good shot.

INSIGHT: I want to zoom out to the big picture here. How did Silicon Valley Bank let this happen? Did they not understand that this was a possibility?

MATVOS: It’s a great question. What could Silicon Valley Bank have done to prevent this? They could have bought interest-rate insurance a couple of years ago. Had they done that, they would’ve been insured.

Or they could have held very short maturity securities. But then they wouldn’t have made very much money. Part of their issue specifically is they didn’t have tremendous lending opportunities: Their clients had too much liquidity. They had to park it somewhere, and they parked it with Silicon Valley Bank. And then the bank just invested in treasuries to earn something rather than completely zero.

But the broader issue is that banks are exposed to fluctuations in their asset values. If banks are very well capitalized, we don’t have the issue that we’ve just seen in the banking sector. For example, in some related work, we looked at the capitalization of financial intermediaries called “shadow banks” that offer a lot of loans in the U.S. but can’t take deposits. We found that these are funded with about 20 percent capital instead of 10 percent for banks. They have quite a lot of capital because they have no fallbacks. If U.S. banks had more capital, we wouldn’t be having this discussion right now.

INSIGHT: Are you envisioning a scenario where different banks with different business models or types of depositors should be held to different capital levels?

MATVOS: No, I think they should all be held to a higher capital level!

Look, of course we can go back to the drawing board, and we can keep trying to rewrite regulations, and maybe we can come up with something sensible. But U.S. history is littered with trying to write better regulations for financial intermediaries. And then in 2008, we realized house prices matter. And now in 2023, we realize interest rates matter, again, even though in the 1980s interest rates drove a third of the savings and loan industry—which is also banks—into default.

I’d probably sleep a little bit better at night as a taxpayer if capital requirements were higher. It just provides you a cushion if we get regulation wrong.

INSIGHT: What other long-term takeaways are you struck by in this particular incident?

MATVOS: That it’s hard to regulate banks! Banks provide a lot of really useful services. We need banks in our economy to move money from people who have too much of it—we call them savers—to people who drive our economy—borrowers. That could be consumers; that could be firms. So we need banking to operate well. It’s not like the financial industry isn’t already very heavily regulated. Medicine and finance are two of the most regulated industries in the U.S. The question is, can we come up with better regulation? Or should we just say that there’s an easier fix: if you want to take deposits, you need a little bit more capital. By a little bit, I mean five percentage points more, which banks consider quite a lot.

Howard Berolzheimer Professor in Finance

Jessica Love is editor in chief of Kellogg Insight .

Jiang, Erica Xuewei, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, Amit Seru. “Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs?” 2023. Available at SSRN.

Read the original

Brought to you by:

The Sudden Implosion of Silicon Valley Bank

By: George Yiorgos Allayannis, Aldo Sesia

On March 10, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) went into receivership. At the time, it was the second-largest US bank failure in history. What happened? The case briefly describes the story of SVB,…

- Length: 32 page(s)

- Publication Date: Oct 31, 2023

- Discipline: Finance

- Product #: UV8805-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

On March 10, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) went into receivership. At the time, it was the second-largest US bank failure in history. What happened? The case briefly describes the story of SVB, from its origin in the early 1980s to March 2023, and focuses on the events surrounding its demise. The case discusses in detail the issues that led to SVB's bankruptcy, in particular interest-rate risk, asset-liability management (ALM), inadequate stress testing, risk management more broadly, corporate governance, regulation, issues related to the bank's focus on venture capital (VC) and private equity (PE) loans, and its exposure to the technology sector. The case also describes the Fed's reaction after the bankruptcy. The SVB episode offers an important learning opportunity that touches many facets of a bank and its environment. It has several clear messages about bank management leadership. The case is well suited for a course on financial institutions, money and banking, and risk management. Ideally it would be positioned after credit, interest-rate, and liquidity risks have been covered, so that students have a better understanding of these concepts before they tackle this case; it could also be used as an introduction to the banking model, its key risks, and the role of the Federal Reserve. At Darden, it is taught in the second-year elective, "Financial Institutions and Markets."

Learning Objectives

The key objectives of the case are as follows: (1) understanding what went wrong with SVB, (2) exploring risk management (interest-rate and liquidity) issues faced by SVB, (3) examining asset-liability management themes present at SVB, (4) discussing corporate governance issues at a bank, (5) discussing SVB's focus on tech and its implications, and (6) contemplating new risks arising from social media.

Oct 31, 2023

Discipline:

Industries:

Financial service sector

Darden School of Business

UV8805-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What Silicon Valley Bank Did Right

- Lou Shipley

It became a fixture among startups because it understood their needs better than other banks.

There’s a reason Silicon Valley Bank became such a fixture among startups: it understood their needs better than any other bank. Even now, many banks don’t have the flexibility and understanding to make banking easy for startups. With SVB gone, a lot of young companies will find it harder to manage their finances.

In the wake of the current wave of bank failures, one of the startups I currently work with — a Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) customer — recently applied to open an account with a major money center bank. The bank came back with a long list of objections and ultimately declined to open even a basic banking account. Reasons given were: the startup was not 100% U.S. owned, had a foreign-born CEO, and had a senior manager residing outside the U.S. The startup was denied even though it is very well capitalized with a CEO residing in the U.S., has many large U.S. customers, and has a very promising future.

- Lou Shipley is a Senior Lecturer in Entrepreneurial Management at Harvard Business School. He serves on the boards of six early-stage technology companies.

Partner Center

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Banking Turmoil: What We Know

Regulators trying to stem panic among customers shut down Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank within days.

By Vivian Giang

On Friday, Silicon Valley Bank , a lender to some of the biggest names in the technology world, became the largest bank to fail since the 2008 financial crisis . By Sunday night, regulators had abruptly shut down Signature Bank to prevent a crisis in the broader banking system. The banks’ swift closures have sent shock waves through the tech industry, Washington and Wall Street.

Here’s what we know so far about this developing story.

Why did Silicon Valley Bank fail?

Silicon Valley Bank provided banking services to nearly half the country’s venture capital-backed technology and life-science companies, according to its website, and to more than 2,500 venture capital firms.

For decades, Silicon Valley Bank, flush with cash from high-flying start-ups, did what most of its rivals do: It kept a small chunk of its deposits in cash, and it used the rest to buy long-term debt like Treasury bonds. Those investments promised steady, modest returns when interest rates remained low. But they were, it turned out, shortsighted. The bank hadn’t considered what was happening in the broader economy, which was overheated after more than a year of pandemic stimulus.

This meant that Silicon Valley Bank was left in the lurch when the Federal Reserve, looking to combat rapid inflation, started raising interest rates. Those once-safe investments looked a lot less attractive as newer government bonds kicked off more interest.

But not all of Silicon Valley Bank’s problems are linked to rising interest rates. The bank was unique in ways that contributed to its rapid demise. Because the bank’s business was concentrated in the tech industry, Silicon Valley Bank started to see trouble when start-up funding began to dwindle, leading its clients — a mixture of technology start-ups and their executives — to tap their accounts more. The bank also had a significant number of big, uninsured depositors — the kind of investors who tend to withdraw their money during signs of turbulence. To fulfill its customers’ requests, the bank had to sell some of its investments at a steep discount.

Once Silicon Valley revealed its huge loss on Wednesday, the tech industry panicked, and start-ups rushed to pull out their money, resulting in a bank run.

By late last week, Silicon Valley Bank was in free fall. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation announced on Friday that it would take over the 40-year-old institution, after the bank and its financial advisers had tried — and failed — to find a buyer to step in. The takeover put about $175 billion in customer deposits under the control of the federal regulator.

The F.D.I.C., created by Congress in 1933 to provide consumer deposit insurance to banks, is responsible for maintaining “stability and public confidence in the nation’s financial system,” according to its website.

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank, based in Santa Clara, Calif., is the largest since the 2008 financial crisis. In the aftermath of that crisis, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank financial-regulatory package, intended to prevent such collapses.

In 2018, President Donald J. Trump signed a bill that reduced how often regional banks had to submit to stress tests by the Federal Reserve. Last week, as news of Silicon Valley Bank’s failure spread, some banking experts said the Dodd-Frank package might have forced the bank to better handle its interest rate risks had it not been rolled back.

Why did Signature Bank fail?

Two days after the F.D.I.C. took control of Silicon Valley Bank, New York regulators abruptly closed Signature Bank on Sunday to stymie risk in the broader financial system.

Signature Bank, which provided lending services for law firms and real estate companies, had deposits of less than $100 billion across 40 branches in the country. The bank’s clients included some people associated with the Trump Organization, Mr. Trump’s company. In 2018, the 24-year-old bank began taking deposits of crypto assets — a fateful decision after the industry’s bottom fell out after the collapse of the FTX cryptocurrency exchange.

Like Silicon Valley Bank’s clients, most of Signature bank’s customers had more than $250,000 in their accounts. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation insures deposits only up to $250,000, so anything more than that would not have the same government protection. Close to nine-tenths of Signature Bank’s roughly $88 billion in deposits were uninsured at the end of last year, according to regulatory filings. As Silicon Valley Bank’s troubles began to spread last week, many of Signature’s customers panicked and began calling the bank, worried that their own deposits could be at risk.

Signature saw a torrent of deposits leaving its coffers on Friday, according to a person with knowledge of the matter, and the bank’s stock, along with the stocks of some of its peers, also continued to tank.

What have regulators done so far?

Regulators have been rushing to contain the fallout , and the collapse of two banks in three days is prompting a swift re-evaluation of the Fed’s interest rate increases. Before the fallout from the banks’ collapse this weekend, the Fed had been expected to make a half-point increase at its next meeting, March 21-22.

In announcing the closing of Signature, regulators said on Sunday that depositors of the bank and Silicon Valley Bank would be made whole regardless of how much they held in their accounts and would have full access to their money by Monday.

On Monday morning, President Biden reassured Americans that the financial system was stable and that customers’ deposits would “be there when you need them.”

Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen said on Sunday that regulators had been working over the weekend to stabilize Silicon Valley Bank — and she tried to assure the public that the broader American banking system was “safe and well capitalized.”

At the same time, she acknowledged that many small businesses were counting on funds tied up at the bank.

Ms. Yellen suggested that a possible solution could be an acquisition of Silicon Valley Bank, emphasizing that regulators were trying to address the situation “in a timely way.” According to a person familiar with the matter, the F.D.I.C. on Saturday started an auction for Silicon Valley Bank that was set to wrap up Sunday afternoon.

On Sunday, the F.D.I.C. invoked a “systemic risk exception,” which allows the government to pay back uninsured depositors to prevent dire consequences for the economy or financial instability. Also on Sunday, the Fed announced that it would set up an emergency lending program, with approval from the Treasury, to provide additional funding to eligible banks and help ensure that they are able to “meet the needs of all their depositors.”

Are other banks at risk?

The demise of both Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank put a spotlight on the challenges surrounding small and midsize banks , which tend to focus on niche businesses and can be more vulnerable to bank runs than larger peers. The most immediate concern is that the failure of one would scare off customers of other banks. Both Silicon Valley Bank and Signature are small compared with the nation’s largest banks — Silicon Valley Bank’s $209 billion and Signature’s $110 billion in assets pale next to the more than $3 trillion at JPMorgan Chase. But bank runs can happen when customers or investors panic and start pulling their deposits.

On Monday, smaller banks rushed to reassure customers that they were on firmer financial footing.

Shares of U.S. regional banks plummeted on Monday, as investors tried to get a handle on the sudden collapse of Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank. First Republic Bank took the worst beating on the day, down 60 percent. Western Alliance in Arizona tumbled 45 percent, KeyCorp and Comerica both tumbled nearly 30 percent, and Zions Bancorp in Utah fell about 25 percent.

Shares of bigger banks were not affected as much: Citigroup and Wells Fargo each fell more than 7 percent, Bank of America fell more than 3 percent, and JPMorgan dipped around 1 percent. The KBW bank index, which tracks the performance of 24 major banks, fell 10 percent, adding to sharp losses last week that erased nearly $200 billion from the aggregate value of the banks in the index.

How is this different from the 2008 bailouts?

Over the past few days, as regulators took control of two banks and guaranteed deposit protections at the institutions, some compared the moves to the 2008 bank bailouts.

On Monday, President Biden tried to distinguish these moves to prevent more bank runs and those taken during the 2008 financial crisis, when hundreds of billions of dollars were provided to rescue the bank industry. Taxpayers shouldered much of that rescue, while the costs to make depositors of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank whole will be financed by fees paid by banks into the F.D.I.C.

“This is an important point: No losses will be borne by the taxpayers,” Mr. Biden said in his statement on Monday morning. “Let me repeat that: No losses will be borne by the taxpayers.”

But he said that “investors in the banks will not be protected.”

“They knowingly took a risk, and when the risk didn’t pay off, investors lose their money,” the president said. “That’s how capitalism works.”

Jessica Silver-Greenberg contributed reporting.

Vivian Giang joined The Times as a senior staff editor in 2019. Prior to The Times, she was a freelance writer and editor covering the workplace. More about Vivian Giang

Explore Our Business Coverage

Dive deeper into the people, issues and trends shaping the world of business..

Elon Musk’s Diplomacy: The billionaire is wooing right-wing world leaders to push his own politics and expand his business empire.

Staying Connected: Some couples are using professional project-management software like Slack and Trello to maintain their relationships. Why does it bother other people ?

A Final Curtain Call: The animatronic band at Chuck E. Cheese, by turns endearing and creepy, will be phased out by year’s end at all but two locations. We visited one of them .

The ‘Betches’ Got Rich: Betches Media, the women’s media company that started as a raunchy college blog, is a rare financial success story. So what’s next ?

Retraining German Workers: As Germany’s industrial landscape shifts, companies have formed an alliance aimed at offering the skills and certification that employees need to find new jobs .

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- Business & Finance

- Stock market

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/72069537/GettyImages_1248143864.0.jpg)

The swift collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, explained

What we know about the bank failure and fallout.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The swift collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, explained

Silicon Valley Bank , one of tech’s favorite lenders, collapsed on Friday after 48 hours of chaos, becoming the second-largest bank failure in US history.

The bank’s blowup has sent shockwaves across the tech sector, Wall Street, and Washington, DC , amid concerns that other banks could be in trouble or that contagion could set in. In the days after Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse, the panic appeared to spread, leading to the failure of additional banks, including Signature Bank of New York , which had bet on crypto. But it’s not clear how serious the fallout would be.

(Disclosure: Vox Media, which owns Vox, banked with SVB before its closure.)

The federal government has said it will step in to make sure all of Silicon Valley Bank depositors would have access to their funds. To some, this looks like a bailout , but President Joe Biden has said that those funds would not come from taxpayer dollars, but via loans from a newly created Bank Term Funding Program. It’s also important to note for consumers that the money you have in the bank right now is almost definitely fine.

Follow here for all of Vox’s coverage of this developing story.

9 questions about Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse, answered

Tech’s favorite bank just failed. What does that mean for you?

The Fed prioritizes inflation over bank turmoil with its latest rate hike

It announced a quarter-point increase to the interest rate this week, despite recent banking woes.

Should you be worried about your small bank?

Turns out you don’t have to be that big to be too big to fail.

What happens to Silicon Valley without Silicon Valley Bank?

A regional bank helped the tech industry grow. Now it might need to shrink.

Why the Silicon Valley Bank collapse couldn’t have happened in this one state

Don’t want to lose your bank deposits? Simple: Bank in Massachusetts.

Did the Fed break Silicon Valley Bank?

SVB’s collapse is the price of the Fed’s interest rate gambit.

Why bailouts keep happening even though everyone hates them

A bailout is the worst option, except for all the others.

What the hell is a “woke bank”?

As Silicon Valley Bank collapses, the right returns to its favorite boogeyman.

Trump-era banking law paved way for Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse

Silicon Valley Bank was a test case for Congress’s 2018 bipartisan banking deregulation law. It failed.

Is this a bailout?

After SVB, is the government bailing out the banks again? Yes-ish. But this isn’t 2008.

Sign up for the newsletter Today, Explained

Thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Christopher Rugaber, Associated Press Christopher Rugaber, Associated Press

Ken Sweet, Associated Press Ken Sweet, Associated Press

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/what-to-know-about-the-silicon-valley-bank-collapse

What to know about the Silicon Valley Bank collapse

WASHINGTON (AP) — Two large banks that cater to the tech industry have collapsed after a bank run, government agencies are taking emergency measures to backstop the financial system, and President Joe Biden is reassuring Americans that the money they have in banks is safe.

It’s all eerily reminiscent of the financial meltdown that began with the bursting of the housing bubble 15 years ago. Yet the initial pace this time around seems even faster.

Over the last three days, the U.S. seized the two financial institutions after a bank run on Silicon Valley Bank, based in Santa Clara, California. It was the largest bank failure since Washington Mutual went under in 2008.

How did we get here? And will the steps the government unveiled over the weekend be enough?

Here are some questions and answers about what has happened and why it matters:

Why did Silicon Valley Bank fail?

Silicon Valley Bank had already been hit hard by a rough patch for technology companies in recent months and the Federal Reserve’s aggressive plan to increase interest rates to combat inflation compounded its problems.

The bank held billions of dollars worth of Treasuries and other bonds, which is typical for most banks as they are considered safe investments. However, the value of previously issued bonds has begun to fall because they pay lower interest rates than comparable bonds issued in today’s higher interest rate environment.

That’s usually not an issue either because bonds are considered long term investments and banks are not required to book declining values until they are sold. Such bonds are not sold for a loss unless there is an emergency and the bank needs cash.

Silicon Valley, the bank that collapsed Friday, had an emergency. Its customers were largely startups and other tech-centric companies that needed more cash over the past year, so they began withdrawing their deposits. That forced the bank to sell a chunk of its bonds at a steep loss, and the pace of those withdrawals accelerated as word spread, effectively rendering Silicon Valley Bank insolvent.

What did the government do on Sunday?

The Federal Reserve, the U.S. Treasury Department, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation decided to guarantee all deposits at Silicon Valley Bank, as well as at New York’s Signature Bank, which was seized on Sunday. Critically, they agreed to guarantee all deposits, above and beyond the limit on insured deposits of $250,000.

Many of Silicon Valley’s startup tech customers and venture capitalists had far more than $250,000 at the bank. As a result, as much as 90 percent of Silicon Valley’s deposits were uninsured. Without the government’s decision to backstop them all, many companies would have lost funds needed to meet payroll, pay bills, and keep the lights on.

The goal of the expanded guarantees is to avert bank runs — where customers rush to remove their money — by establishing the Fed’s commitment to protecting the deposits of businesses and individuals and calming nerves after a harrowing few days.

ANALYSIS: What Silicon Valley Bank collapse means for the U.S. financial system

Also late Sunday, the Federal Reserve initiated a broad emergency lending program intended to shore up confidence in the nation’s financial system.

Banks will be allowed to borrow money straight from the Fed in order to cover any potential rush of customer withdrawals without being forced into the type of money-losing bond sales that would threaten their financial stability. Such fire sales are what caused Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse.

If all works as planned, the emergency lending program may not actually have to lend much money. Rather, it will reassure the public that the Fed will cover their deposits and that it is willing to lend big to do so. There is no cap on the amount that banks can borrow, other than their ability to provide collateral.

How is the program intended to work?

Unlike its more byzantine efforts to rescue the banking system during the financial crisis of 2007-08, the Fed’s approach this time is relatively straightforward. It has set up a new lending facility with the bureaucratic moniker, “Bank Term Funding Program.”

The program will provide loans to banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions for up to a year. The banks are being asked to post Treasuries and other government-backed bonds as collateral.

The Fed is being generous in its terms: It will charge a relatively low interest rate — just 0.1 percentage points higher than market rates — and it will lend against the face value of the bonds, rather than the market value. Lending against the face value of bonds is a key provision that will allow banks to borrow more money because the value of those bonds, at least on paper, has fallen as interest rates have moved higher.

As of the end of last year U.S. banks held Treasuries and other securities with about $620 billion of unrealized losses, according to the FDIC . That means they would take huge losses if forced to sell those securities to cover a rush of withdrawals.

How did the banks end up with such big losses?

Ironically, a big chunk of that $620 billion in unrealized losses can be tied to the Federal Reserve’s own interest-rate policies over the past year.

READ MORE: Yellen says there will be no bailout for collapsed Silicon Valley Bank

In its fight to cool the economy and bring down inflation, the Fed has rapidly pushed up its benchmark interest rate from nearly zero to about 4.6 percent. That has indirectly lifted the yield, or interest paid, on a range of government bonds, particularly two-year Treasuries, which topped 5 percent until the end of last week.

When new bonds arrive with higher interest rates, it makes existing bonds with lower yields much less valuable if they must be sold. Banks are not forced to recognize such losses on their books until they sell those assets, which Silicon Valley was forced to do.

How important are the government guarantees?

They’re very important. Legally, the FDIC is required to pursue the cheapest route when winding down a bank. In the case of Silicon Valley or Signature, that would have meant sticking to rules on the books, meaning that only the first $250,000 in depositors’ accounts would be covered.

Going beyond the $250,000 cap required a decision that the failure of the two banks posed a “systemic risk.” The Fed’s six-member board unanimously reached that conclusion. The FDIC and the Treasury Secretary went along with the decision as well.

Will these programs spend taxpayer dollars?

The U.S. says that guaranteeing the deposits won’t require any taxpayer funds. Instead, any losses from the FDIC’s insurance fund would be replenished by a levying an additional fee on banks.

READ MORE: Silicon Valley Bank’s failure shakes companies worldwide, from wine country to London

Yet Krishna Guha, an analyst with the investment bank Evercore ISI, said that political opponents will argue that the higher FDIC fees will “ultimately fall on small banks and Main Street business.” That, in theory, could cost consumers and businesses in the long run.

Will it all work?

Guha and other analysts say that the government’s response is expansive and should stabilize the banking system, though share prices for medium-sized banks, similar to Silicon Valley and Signature, plunged Monday.

“We think the double-barreled bazooka should be enough to quell potential runs at other regional banks and restore relative stability in the days ahead,” Guha wrote in a note to clients.

Paul Ashworth, an economist at Capital Economics, said the Fed’s lending program means banks should be able to “ride out the storm.”

“These are strong moves,” he said.

Yet Ashworth also added a note of caution: “Rationally, this should be enough to stop any contagion from spreading and taking down more banks … but contagion has always been more about irrational fear, so we would stress that there is no guarantee this will work.”

Support Provided By: Learn more

Another strong jobs report raises more questions about inflation and interest rate hikes

Economy Mar 10

What Does the Failure of Silicon Valley Bank Say About the State of Finance?

The bank run that led to the stunning collapse of Silicon Valley Bank late last week continues to send shivers through the American financial system. SVB, the Santa Clara, California-based bank that catered to the tech industry, was the biggest US lender to fail since the 2008 global financial crisis—and was the second-biggest to fail ever.

Analysts say SVB was largely unprepared for the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate increases, which shrank the value of its investments. As word spread quickly online that the bank could be in trouble last week, customers withdrew $42 billion in a single day, leaving the bank with a $1 billion negative balance, according to a regulatory filing by the company.

While financial regulators have announced that the US will guarantee all deposits at SVB, its collapse has spooked customers at other banks and raised concerns about other financial institutions. We asked Harvard Business School faculty who study banks: What does the failure of SVB say about the current state of the banking industry? Here’s what they said.

Victoria Ivashina: Banks are ‘fundamentally fragile.’

Much has been said already about the textbook nature of the deposits run on SVB, and the subsequent run on other regional banks. Many observers postulate that the vulnerability was hiding in plain sight (an unsettling thought), a result of a combination of COVID government stimulus followed by a series of rates hikes. I would add other contributors: general uncertainty exhaustion after several years of dealing with surprises ranging from shortages and runs on basic goods to the Fed’s limited ability to control or even forecast inflation. Something will also have to be said eventually about the profitable business of inciting runs that some hedge funds have been up to. While all of these factors likely played a role, this narrative oversimplifies a few points and plays into the panic.

Banks are fundamentally fragile, and as such, are prone to self-fulfilling prophesies. Deposit insurance has been effective in reducing deposits runs, but the truth is that—once the confidence is eroded—banks tend to face revolving credit runs and market funding runs. The deposits run in the US might feel like a thing of the past, but the history of the 2008 crisis saw many such examples. Regulation and supervision help moderate the depth of the shock that banks can withstand before a run could be unleashed, but they cannot eliminate the possibility of such a run. The relevant question is then: What has triggered the SVB run? This is where things get more complicated, and—the good news—they also get more idiosyncratic.

We actually do not know much about SVB’s exposures, since they fell below the Fed’s threshold for annual collection of Form FR Y-14A Capital Assessments and Stress Testing. At the moment, we also cannot track what fraction of SVB’s deposits was connected to the local venture capital (VC) ecosystem that it was serving. But we do know that that this bank was different, and it is highlighted in its name and in the history of its public statement.

"The bottom line: The art is not to predict whether a run might take place, but when."

For example, it is very clear that there is no other bank with over half of its loan portfolio dedicated to private equity subscription lines—that is, lines secured by VC and private equity fund commitments but ones used to fund investments in the short- to mid-term in lieu of capital call. It appears that this unusual specialized business model might have introduced significant correlation between large deposits and its business of revolving credit, on which it had substantial exposure. To add to that, the SVB leadership’s unorthodox approach to management of liquidity pressures clearly backfired.

The bottom line: The art is not to predict whether a run might take place, but when. The triggers of the run on SVB were no more apparent than the runs we have seen in the crypto space. The swift government actions to back regional banks, in my view, are commendable, although more targeted to managing general confidence than reflecting the isolated nature of the SVB troubles. They should be effective in reestablishing confidence in the broader financial system.

As to SVB, its credit specialization in the VC space is leaving an important void. I am less concerned about subscription lines, although this might temporarily bounce into pension liquidity. These events, however, are likely to have other lasting effects on the VC industry side, a subject for another day.

Victoria Ivashina is the Lovett-Learned Professor of Finance and head of the Finance Unit.

Erik Stafford: Interest rate exposure and customer withdrawals were devastating

SVB was unique in some ways, but also did some pretty normal bank activities. The business of banking involves investing in assets that are a little bit longer-term and a little bit riskier than the liabilities used to fund these investments. Banks invest in assets like US Treasury bonds, mortgages, and corporate loans. The liability side of their portfolio is a combination of checking and savings deposits, CDs, and debt.

Most deposit rates reset fairly often, so they represent relatively short-term borrowing for the bank. The equity receives the net cash flows and realizes the net gains and losses from value changes. Bank annual reports emphasize that bank earnings or cash flows are relatively insensitive to changes in interest rates.

Additionally, the stability of net interest margin (interest received minus interest paid) is pointed to as evidence that banks have little interest rate exposure. Many bank loans to businesses have floating interest rates, but most bank loans are mortgages, which tend to have fixed interest rates, and US Treasury bonds have fixed interest rates, too. Of course, because the interest payments are fixed, the value of these assets is sensitive to changes in market interest rates.

From an investment perspective, the value sensitivity to changes in interest rates is the most relevant. Note that it is typically difficult to hedge both the value and cash flow interest rate exposure, so the fact that the cash flows appear insensitive to interest rate changes suggests that the value-based interest rate exposure has not been hedged.

"SVB was forced to issue a large amount of equity, which brought a lot of attention to their situation."

Banks are highly levered, which magnifies the asset risk exposures for the equity. Suppose that bank assets resemble two-year bonds, interest rates increase quickly from 1 percent to 5 percent, and banks have equity of $20 for every $100 of assets. In order for the two-year bonds to earn the new market rate of 5 percent, their value will need to fall by about 7.5 percent, so assets of $100 now have a market value of $92.50. Because of the leverage, this $7.50 loss per $100 of assets represents a loss of $7.50 per $20 of equity, or around -38 percent.

One unique feature of SVB was their large uninsured deposit base. It is often argued that the present value of the ongoing profits that will be generated from deposit accounts effectively hedge the value-based interest rate exposure of the bank assets. In other words, the value of these accounts to the bank increase when interest rates increase, which offsets, at least partially, the interest rate exposure of the assets described above. One interesting feature of the SVB situation is that the value of their deposits fell as interest rates increased in a somewhat unexpected way. Well before the bank run last week, their deposit customers had been withdrawing money to pay their operating expenses, while their deposit inflows from new VC funding slowed, which produced large net withdrawals of deposits.

In this case, deposits appear to have added, rather than hedged, value-based interest rate exposure. The bank run was devastating for SVB, but the real problems that triggered this event were the underlying interest rate exposure and the slow withdrawal of deposits. SVB was forced to issue a large amount of equity, which brought a lot of attention to their situation. There is now a lot of attention on the situation at all banks. The underlying interest rate exposure is common across banks, so some drop in bank equity values is appropriate. An important question to be determined is whether there are other banks who have been experiencing a slow withdrawal of customer deposit balances. This is quickly being investigated by investors and regulators.

Erik Stafford is the John A. Paulson Professor of Business Administration.

You Might Also Like:

- After High-Profile Failures, Can Investors Still Trust Credit Ratings?

- Buy Now, Pay Later: How Retail's Hot Feature Hurts Low-Income Shoppers

- Did Pandemic Stimulus Funds Spur the Rise of 'Meme Stocks'?

Feedback or ideas to share? Email the Working Knowledge team at [email protected] .

Image: iStockphoto/Sundry Photography

- 09 May 2024

- Research & Ideas

Called Back to the Office? How You Benefit from Ideas You Didn't Know You Were Missing

- 06 May 2024

The Critical Minutes After a Virtual Meeting That Can Build Up or Tear Down Teams

- 01 May 2024

- What Do You Think?

Have You Had Enough?

- 13 May 2024

Picture This: Why Online Image Searches Drive Purchases

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- Banks and Banking

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy

- Governing Rules, Regulations, and Reforms

- Financial Services

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Could Silicon Valley Bank happen again? ‘The short answer is, yes,’ says professor who sees $2 trillion of losses on the books

At the Fortune Future of Finance conference, Tomasz Piskorski, Edward S. Gordon Professor of Real Estate, Finance Division, Columbia Business School, tackled the subject of much of his recent research: the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and its after-effects on the banking industry. Last year, Piskorski was one of several academics to look at the sector . Their paper found a “more than $2 trillion decline in banks’ asset values following the monetary tightening of 2022.” Below is a transcript of Piskorski’s presentation to the conference on his research.

Tomasz Piskorski: Welcome everybody. Glad to be here. I’m a professor at Columbia Business School. I do a lot of work on financial intermediation, banking, fintech, and real estate. And recently, along with my colleagues, I have done quite a lot of work on financial stability.

And drawing lessons from the recent bank failures such as the Silicon Valley Bank, I would like to tell you a little bit about it. So, let me tell you our view—what we think is one of the main sources of risk currently in the U.S. financial system.

From our perspective, it’s really the fact that banks have very high leverage. If you look at a typical bank in the United States, there is really very little variation, whether you’re a small bank, whether you’re a large bank. Banks are essentially about 90% debt-funded, and only 10% of equity. So think about what it means: Consider, for example, a situation when there is a modest decline in the value of bank assets, let’s say 10%. That already potentially puts this institution at the brink of insolvency, because the value of the assets will be less than the face value of the liabilities. And if you look at the banking sector as a whole, this is $24 trillion worth of assets.

On the asset side, banks take a lot of duration risk and credit risk. They give a lot of assets like securities, long-term treasuries, long-term mortgage-backed securities. In addition, they have real estate loans, including commercial real estate loans, and other loans like corporate loans with a credit risk. And the way they finance it is essentially with short-term debt. Most of these debts are deposits. About 18 trillion of them and about half are insured by FDIC and half are uninsured. These deposits are both $250,000. And in addition to that, the banks have firmly seen equity caution. So, you can see this is a pretty fragile system with very little equity financing and a lot of debt financing.

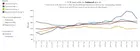

And in that sense, the recent monetary tightening illustrates this point: the Fed raised interest rates very aggressively, essentially, in a matter of a year, they went from zero to 5%. What that means to the value of long duration assets: There has been a very big decline in value, including U.S. Treasuries and so on. If you look at long duration assets, long-term bonds, they declined by, in the order of 30%. So, when you take this decline, the market-implied decline in the value of assets and apply it to bank balance sheets, what you will find is that, in the aggregate, the value of the bank assets right now is about $2 trillion less relative to where it was at the beginning of the Fed tightening cycle.

And in fact, there’s quite a few banks in the U.S. right now–and Silicon Valley Bank was one of them–that currently have the value of the assets, the market value, of being less than the face value of the debt. So, in principle, if the depositors would show up, this bank would fail, unless of course regulators step in.

Now, I’m not trying to say that all these banks will fail—it depends on your funding. And in particular, it depends what portion of your funding is unstable, especially uninsured deposits. Because uninsured depositors can lose money if the bank fails. And, you know, in that sense, Silicon Valley Bank was an outlier in that 80% of its assets were financed with uninsured deposits. Essentially, Silicon Valley Bank had just uninsured deposit funding. So, it was very fragile in that sense.

The mechanism is as follows: The interest rates go up, you can add to this credit risk, bank asset values decline like they did, and insured depositors get spooked, they see this big declines in asset values, they worry about solvency of the bank, they start withdrawing money, and then you can end up with a run equilibrium.

The key question that I was talking a lot with regulators about that is, how special is a Silicon Valley Bank? Are there other banks like that? And the short answer is, yes, there are quite a few banks in the United States right now that have very similar risk characteristics, not as extreme as Silicon Valley Bank, but they are actually at the risk of a run.

And this is just the duration effect. If you add to this credit risk, remember that for midsize banks, about 25 to 30% of the assets are commercial real estate loans. We did an analysis loan by loan 14% of these loans are underwater, meaning the property value is less worth less currently than the face value of debt. If you look at office loans, it’s 44%. So, in addition to this duration risk, there is also a credit risk that will enlarge the set of banks that could potentially fail.

So, the obvious question is—talking all the time with regulators—what to do about it? And one natural answer is, well, let’s raise the bank capital requirements. Maybe not right now. Once things come down a bit. That would make the system more safe, but the obvious question is how much leverage financial institutions really need to provide efficient functions like originating loans, and doing other things. And in fact, we have a window in it: We compare the leverage of banks, to non-bank lenders. The dark black curve shows you the non-bank lenders. These are the institutions that make loans like banks, this is in the mortgage market, but don’t have access to insure deposit funding, and are lightly regulated. And guess what? In this private market benchmark, without access to insure deposit funding, these institutions have much less leverage and much more equity funding. And the lesson we draw from this is you can be a pretty good lender with much lower leverage.

And what’s interesting is the biggest discrepancy is actually for smaller and midsize banks. What it means is that, let’s say JPMorgan, their leverage is pretty close to what they would have been levered, even if they didn’t have access to ensure deposit funding. It’s precisely the smaller and midsize banks, including banks like Silicon Valley Bank, that will deliver much more. And because of these implicit and explicit guarantees, Silicon Valley Bank did not have much insured deposits funding, but there’s a lot of other banks that do and take advantage of that.

One thing is that if you talk to bank CEOs, they will tell you, “Hey, if you raise bank capital requirements, the lending will collapse, and we’re gonna have a contraction of economic activity, we just really cannot do it.” Of course, the answer to this question depends on how important are banks in financing credit to households and firms. And let me just tell you, they’re not as important as commonly thought. In the 1970s, a bank balance sheet financed 60% of lending to households. So in other words, in the 1970s, banks were very important. Nowadays, banks finance only about a third of credit to house concerns. The rest is financed with debt securities, private credit, and so on, and so forth. So in the aggregate, the banks are much less important than they were a few decades ago. And what it means it has interesting implications for capital regulation.

We actually did a simulation: if you would raise capital requirements on U.S. banks, while the amount of bank balance sheet lending will drop substantially, and so will the bank profits. So, it’s kind of understandable why some bank CEOs might not like it. But the aggregate decline in lending would actually be quite modest. What would simply happen is that the bank would still make loans, but instead of keeping them on the balance sheet, they would sell them, and there would be expansion of non-bank and private credit.

So, let me just conclude with some thoughts on where I’m thinking it will go going forward.

First, I think the banks are continuing to become increasingly less relevant, and especially smaller and midsize banks will have ongoing consolidation in the banking industry. I predict in a few years, we’ll have much fewer smaller and midsize banks. I also think that we’ll see a growing rise of debt securities and private credit. Private credit is rapidly increasing right now. And of course, who’s going to finance a lot of that, you know, vehicles like money market funds, exchange, traded funds, and so on.

On the asset side, the traditional banks already lost a lot of edge. Think about mortgage finance, which is a very important debt market. Now, banks account for less than half of the lending there. And the biggest lender is Quicken Loan, currently called Rocket Mortgage, and they just have the platform, they don’t have deposits, it’s a non-bank.