An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Treatment decisions in end-stage COPD: who decides how? A cross-sectional survey of different medical specialties

Martin gäbler, gerald ohrenberger, georg-christian funk.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Martin Gäbler, Institute of Preventive and Applied Sports Medicine, Krems University Hospital, Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences, Mitterweg 10, 3500 Krems, Austria. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2018 Sep 17; Accepted 2019 Jun 20; Collection date 2019 Jul.

This article is open access and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Licence 4.0.

Introduction

End-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients with acute respiratory failure are often treated by representatives from different medical specialties. This study investigates if the choice of treatment is influenced by the medical specialty.

An online cross-sectional survey among four Austrian medical societies was performed, accompanied by a case vignette of a geriatric end-stage COPD patient with acute respiratory failure. Respondents had to choose between noninvasive ventilation (NIV), a conservative treatment attempt (without NIV) and a palliative approach. Ethical considerations and their impact on decision making were also assessed.

Responses of 162 physicians (67 from intensive care units (ICUs), 51 from pulmonology or internal departments and 44 from geriatric or palliative care) were included. The decision for NIV (instead of a conservative or palliative approach) was associated with working in an ICU (OR 14.9, 95% CI 1.87–118.8) and in a pulmonology or internal department (OR 9.4, 95% CI 1.14–78.42) compared with working in geriatric or palliative care (Model 1). The decision for palliative care was negatively associated with working in a pulmonology or internal department (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.05–0.47) and (nonsignificantly) in an ICU (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.15–1.12) (Model 2).

Conclusions

Department association was shown to be an independent predictor for treatment decisions in end-stage COPD with acute respiratory failure. Further research on these differences and influential factors is necessary.

Short abstract

Physicians from different departments make different treatment decisions in end-stage COPD patients with acute exacerbations. This may lead to over- or undertreatment. Subsequent training efforts (including ethical decision making) may be beneficial. http://bit.ly/2xaw1MW

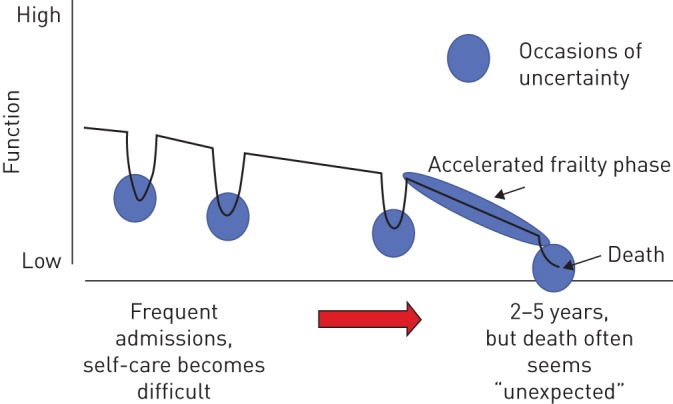

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third most common cause of death in the European Union and has a high prevalence among adults aged ≥40 years [ 1 ]. End-stage COPD is marked by a severe functional decline, frequent exacerbations and hospital admissions [ 2 , 3 ]. Deterioration in this phase is often caused by exacerbations, making end-of-life prediction uncertain ( figure 1 ) [ 4 ].

A typical life trajectory of a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patient, who experiences a continuous physical decline due to the loss of organ function and comorbidities. Dips in the curve are caused by exacerbations and represent stages of uncertain outcome. Reproduced from [ 4 ] with permission.

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) and palliative care are important treatment options in end-stage COPD, whereas NIV is not limited to only a therapeutic intervention, but can also be used as a ceiling therapy with palliative intent [ 5 – 8 ]. Palliative care is defined as “interventions aimed to prevent and relieve suffering by controlling symptoms and providing other support … in order to maintain and improve … quality of living during all stages of chronic life-threatening (or terminal) illness” [ 9 ]. However, not all eligible patients receive these treatment options and resources vary due to region and hospital, thus creating differences in the quality of care [ 9 – 13 ].

On the clinician side, treatment decisions in end-of-life situations seem to be influenced by their personal knowledge/experience, assessment of the situation, and personal and ethical values/beliefs [ 4 , 13 – 16 ]. This decision making under uncertainty may therefore be subject to judgemental bias [ 17 ]. The main ethical considerations in end-of-life situations are the medical indication or appropriateness (beneficence and nonmaleficence) and the will of the patient ( i.e. respect for patient autonomy/preference), as well as quality of life, contextual factors and issues of justice/fairness [ 18 – 20 ].

As COPD patients are cared for by a variety of healthcare providers from different specialty fields [ 21 ], evidence about the correlation between treatment differences and physician specialty (or demographic characteristics) is sparse and contradictory [ 22 – 25 ]. To date, no study of treatment decisions in end-stage COPD patients has been undertaken. Our hypothesis was that doctors would opt for different treatments according to their departments. Therefore, the overall aim of this study was to determine whether (or not) physicians would choose different treatment pathways in end-stage COPD based on their different departments. Additional aims were to evaluate whether any sociodemographic or ethical factors could serve as predictors for decision making and how important ethical aspects were to physicians in their decision process. If treatment choices differ, chances are high for end-stage COPD patients to experience markedly different therapeutic approaches in a crucial phase of their disease, with possibilities ranging from under- to overtreatment.

Study design

A cross-sectional survey via a web-based questionnaire was carried out among physicians from four different Austrian medical societies from July 28 to August 18, 2016.

Members of five Austrian medical societies were invited to participate. Four societies participated: the Austrian Society of Pneumology, the Austrian Society for Internal and General Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, the Austrian Society for Geriatrics and Gerontology, and the Austrian Palliative Society. The fifth, the Austrian Society of Internal Medicine, declined the invitation.

Only completed questionnaires from physicians actively treating patients and working in the fields of 1) intensive care, 2) pulmonology or internal medicine and 3) geriatric or palliative care (thus forming the groups) were included in the analysis. A fourth group (working in the emergency department) had been planned, but was excluded as only five participants were recruited.

An estimated minimum sample size of 133 respondents was calculated by means of the Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test with G*Power ( www.gpower.hhu.de ), using a medium effect size of 0.3, an α-value of 0.05, a minimal power of 0.80 and 4 degrees of freedom.

Data safety and ethics

To ensure anonymity, participants received an e-mail via their societies with a link to the survey (which did not contain any hidden codes) at www.soscisurvey.de . No information ( e.g. IP address) was collected about participants taking part in the survey.

The survey was conducted among experts in the field, with neither patient involvement nor interventions, and therefore an ethics committee approval was not obligatory, as was confirmed by the Ethics Committee of the City of Vienna (Vienna, Austria). The ethics guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Questionnaire

To answer the research question, a case vignette ( table 1 ) and a supplemental questionnaire were developed, since no adequate vignette and questionnaire were available. Vignettes are considered to be valid tools for measuring the quality of physicians' practices and a better gauge of treatment decisions than standardised patients, medical record abstraction or claims data analysis [ 26 – 28 ].

Case vignette of a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patient for whom a treatment pathway has to be chosen

The complete survey (in German) is available in the supplementary material .

Designed according to recommendations in the literature [ 26 ], the case vignette featured a typical geriatric end-stage COPD patient with acute respiratory failure on admittance to the hospital. The background information provided was concisely limited (as it is often experienced in clinical cases), thus not allowing a medically right or wrong decision. Additionally, respondents had to make an either/or choice, implying that a “palliative approach” meant sole symptom control in a terminally ill patient (not receiving any further life-prolonging therapies).

The supplemental questionnaire was composed of four parts. First, medical ethics considerations had to be rated, with items in this section comprising four to six questions each and covering the four topics as defined by J onson et al. [ 19 ], i.e. medical indication, patient preference, quality of life and contextual features. Second, respondents were asked whether they had had to make a similar decision in a case of their own and whether they had actively sought answers to these medical ethics questions. The third part asked questions about practical decision making and assessed the relevance of the survey topic for the respondents' daily work. The fourth part focused on common sociodemographic factors, i.e. level of education, job experience, age and sex. The final questionnaire comprised 81 items.

After three physicians tested the first draft, the revised questionnaire was then pre-tested among 18 physicians with the focus on understandability, operability and decision distribution. All recommendations for the questionnaire were implemented, and the case vignette was revised prior to final delivery to incorporate input from a geriatrician and an intensivist.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics used the Chi-squared test to present the sample characteristics and ANOVA for a comparison of age by department affiliation. All sociodemographic factors were dichotomous, with the exception of job experience and age, which were interval scaled. The questionnaire asked for multiple education levels, but only the highest specialisation was taken into consideration. The hypothesis was tested by the Chi-squared test. The questions pertaining to ethics and to practical decision making used a four-grade Likert-scale, thereby inducing a forced choice. Questions regarding the specific case that respondents were asked to recall from their own experience were dichotomous. All were calculated by the Chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was then used to explore the association of various predictors with the treatment decision. Therefore, the treatment decisions were dichotomised as NIV “yes” or “no” and palliative care “yes” or “no”, and calculated as separate models. The “geriatric and palliative care” group was chosen as the reference group for both models, as the significance (in the post hoc analysis) of the treatment decisions in the different groups was the highest against this group. For choosing the various predictors, age was tested by point-biserial correlation, all other items by the Chi-squared independent test with Cramérs V on contingency/correlation against the dichotomised treatment decisions. All significant variables (p≤0.05) were correlated with each other for avoidance of multicollinearity. In the case of a higher correlation (Cramérs V 0.6–1.0), the variable that had the higher association with the outcome was used. The variables were then sequentially included into the regression according to their significance value [ 29 – 31 ]. Due to the limited sample size, only parsimonious models without interactions were applied. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics for Macintosh version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Participants

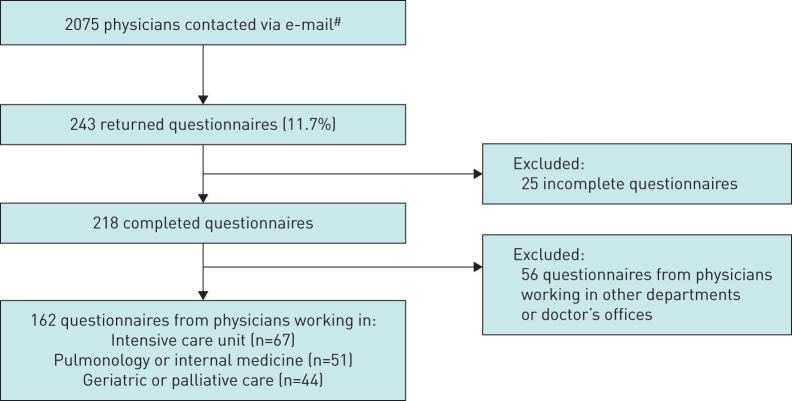

Of the 2075 physicians contacted, 243 took part in the survey (response rate 11.7%), which led to 162 eligible questionnaires as shown in figure 2 .

Flowchart of data acquisition. # : Austrian Society for Geriatrics and Gerontology n=310, Austrian Society for Internal and General Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine n=812, Austrian Society of Pneumology n=611, and Austrian Palliative Society n=342.

The mean age of the participants was 49 years; doctors working in geriatric and palliative care were significantly older than doctors in the other departments. Around two-thirds of the physicians had ≥10 years of job experience, with the majority being trained specialists. The baseline characteristics are shown in table 2 .

Sociodemographic characteristics stratified by department

Data are presented as n, mean± sd or n (%), unless otherwise stated. # : p-value obtained by ANOVA; ¶ : p-value obtained by the Chi-squared test.

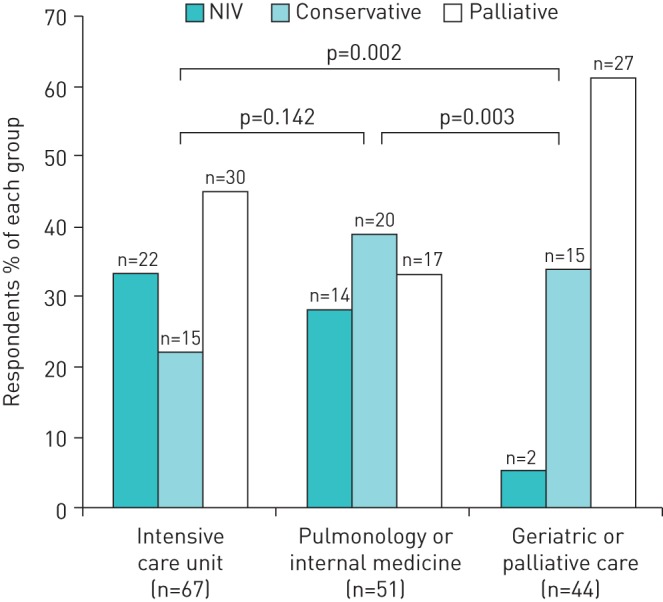

Treatment decision

38 (23%) respondents chose NIV, 50 (31%) respondents chose a conservative treatment approach and 74 (46%) respondents chose a palliative approach. Choices differed markedly depending upon the department where the physicians worked ( figure 3 ).

Treatment decisions in end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by department affiliation. NIV: noninvasive ventilation. p-value obtained by the Chi-squared test.

Predictors for the treatment decision

Two models were calculated: Model 1 for the decision for or against NIV and Model 2 for the decision for or against palliative care.

Intensivists had an almost 15-fold probability and pulmonologists/internists a nine-fold probability of inducing NIV in comparison with geriatricians/palliative physicians. By contrast, increasing age of the physician tended to correlate significantly against starting NIV. No effect was observed due to the following variables: amount (years) of professional experience, educational level and the importance of low patient stress due to the intervention. Details are shown in table 3 .

Model 1: independent predictors for a decision for (or against) noninvasive ventilation (NIV)

Odds ratios were obtained by multivariable logistic regression. OR >1 shows a higher probability for NIV. # : physicians with a positive answer to: “Do you advise patients with a foreseeably severe disease progression and/or limited life expectancy to draw up a living will?”.

Furthermore, pulmonologists/internists had a 16% probability and intensivists a 41% (nonsignificant) probability for choosing palliative care in comparison with geriatricians/palliative physicians. Physician age, amount (years) of professional experience and educational level had no influence on this decision; neither did the recommendation to draw up a living will. Details are shown in table 4 .

Model 2: independent predictors for a decision for (or against) a palliative approach

OR <1 shows a lower probability for a palliative approach. # : these respondents stated that the concerns of other professional groups ( e.g. nurses) involved in patient care had influenced their decision in the specific case they were asked to recall; ¶ : these respondents stated that they actively asked if a guardianship was in place in the specific case they were asked to recall.

Additional findings

In the comments section of the case vignette, 43% of the respondents wanted to know if the patient had any sort of precautionary directive (living will, healthcare proxy, etc. ). Other questions pertained to medications, laboratory results (arterial blood gas, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide), imaging (radiography, computed tomography) and the opinion of relatives.

All but the contextual factors of the medical ethics considerations seemed to be of high importance to the majority of respondents. The overall results are shown in the supplementary material .

Significant differences among the groups were found in four items. “Probability of success of the intervention” was rated “very important” by 60% of the intensivists, 47% of the lung/internal physicians and 80% of the geriatricians/palliative physicians (p=0.001). “Lack of independence – need for nursing care” was rated “very important” by 28% of the intensivists, 39% of the lung/internal physicians and 14% of the geriatricians/palliative physicians (p=0.003). “Functional status before the treatment” was “very important” for 40% of the intensivists, 63% of the lung/internal physicians and 32% of the geriatricians/palliative physicians (p=0.015). The aspect of “Dementia” was “very important” for 28% of the intensivists, 35% of the lung/internal physicians and 16% of the geriatricians/palliative physicians (p=0.046).

131 (81%) of the respondents answered the optional items pertaining to a specific case from their experience and ratings were similar to those given for the medical ethics considerations. The physician groups differed in two of their ratings. 1) 86% of the intensivists, 70% of the lung/internal physicians and 91% of the geriatricians/palliative physicians claimed to have actively considered or asked if the patient had dementia (p=0.039). 2) 14% of the intensivists, 40% of the lung/internal physicians and 31% of the geriatricians/palliative physicians declared that the attitude of the ICU physician regarding admittance of the patient had influenced their decision (p=0.021).

With regard to practical decision making, differences were found in two questions. 80% of the intensivists, 59% of the lung/internal physicians and 89% of the geriatricians/palliative physicians said they “always” read through an existing patient directive themselves before making their decision (p=0.006). 17% of the intensivists, 18% of the lung/internal physicians and 50% of the geriatricians/palliative physicians said they “always” try to discuss important decisions with patients who are cognitively restricted ( e.g. somnolence, dementia, delirium) (p<0.001).

127 (80%) of the respondents indicated that they “always” or “often” had to make similar decisions in the last 4–6 weeks ( i.e. if a therapy was to be intensified, limited or withdrawn). 143 (91%) of the respondents specified that they “always” or “often” had clear principles for making such a decision. Half of the respondents (49%) affirmed that end-of-life decisions are “often” or “always” stressful to them, even though 96% said they would “always” or “often” discuss the decision in advance with colleagues (or others). 165 (97%) stated that workload was “not” or “less important” for their decision, but in the recalled case 32 (25%) indicated that their “current mood, workload, empathy/antipathy” had influenced their decision negatively. 118 (77%) indicated that “guidelines for using resources, especially specialised beds” were “not” or “less important”, as was confirmed by 102 (80%) who did not “consider it actively” in their recalled case.

The aim of this cross-sectional study was to explore the situation of therapeutic decision making in end-stage COPD with acute exacerbations among different specialties, an area where sufficient evidence is lacking.

Our study has shown that the specialty/department affiliation of the physician is a predictor for end-stage COPD treatment decisions. Our results also indicate that the age of the physician seems to be predictive for a decision against NIV.

In contrast to our study, P earlman and J onsen [ 22 ], who used a similar case vignette in 1985 to compare quality-of-life considerations in decisions made by internal medicine and family medicine physicians with regard to employing life-sustaining therapy ( i.e. invasive ventilation), found no difference between the physician groups and their treatment decisions. In 1988, R egueiro et al . [ 23 ] found no difference between generalist and pulmonologist care on survival outcomes and costs for patients hospitalised with severe COPD, but did not investigate decision behaviour.

The high importance of the ethical topics in our study is in alignment with other results, such as in the ETHICATT study, where S prung et al . [ 14 ] have shown that quality of life (in comparison with value of life) was more important to physicians (88%) and nurses (87%) than to relatives (63%) and patients (51%).

A different approach to end-of-life issues by intensivists and palliative care physicians has been described by J ox et al . [ 16 ]; this can also be observed in our study in the different ratings given to some of the medical ethics questions by the different specialties.

The influence of physician age on medical care decisions has already been demonstrated. M c N eely et al . [ 24 ] surveyed respirologists about the decision to use mechanical ventilation when they approach end-stage COPD patients. They were able to show that physicians who have been practising longer tended to use a more physician- than patient-centred approach and also that they were more likely to withhold invasive ventilation for patients who abuse alcohol. Similarly, in a survey in Singapore in 2013, M alhotra et al . [ 32 ] found different recommendations for life-prolonging treatments according to the years of experience of the physician. D elgado et al . [ 33 ] further found that older physicians were less likely to order a spirometry test or to consider tobacco to be a major risk factor in a case vignette with COPD symptoms.

L ópez- C ampos et al . [ 13 ] found a high variability of hospital resources for acute care of COPD patients, which may be an attributing factor for treatment differences.

Strength and weaknesses

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of treatment decisions in end-stage COPD with acute respiratory failure by physicians from different specialties/departments. Data quality can be assumed to be high due to the number of respondents in all groups, almost 100% of questions answered, a balanced decision distribution in the case vignette and a normal distribution of the time needed to fill out the survey. Furthermore, it was possible to investigate a population of respondents who are regularly involved in the treatment of similar patients and who indicated that the questionnaire covered a topic relevant to their work. In addition, the participating physicians were very experienced and highly trained.

However, there are certain limitations. First, the recruitment of the participants through medical societies probably led to a selection bias, which may have been enhanced further by the fact that mainly physicians with a high level of interest in the topic of the questionnaire responded. This probably contributed to the low return rate, as well as the short time frame for the survey response during the Austrian summer holidays and the fact that no direct reminder mailings were possible. Also, it cannot be excluded that an unwillingness to face emotionally difficult survey questions influenced the participation rate.

Second, neglecting to explore physicians' medical knowledge and familiarity with guidelines (as the case vignette had been concisely designed to not examine this) and the local situation ( i.e. availability of NIV) renders it impossible to make any statements about how the level of knowledge ( i.e. knowing the indication, strengths and limits of NIV and palliative care) and the availability of resources influenced the different decisions. Also, religious affiliation was not asked for, but may influence ethical values and decision making [ 14 ].

Third, additional validation of the case vignette and questionnaire is needed, even though measures (as described) were taken to improve study quality.

Fourth, results from case vignettes may differ from real-life situations due to a social desirability bias and the absence of real-world conditions such as time constraints, work load, etc. [ 34 ]. Also, the answer in the case vignette was only for an either/or instead of allowing contemporary combination of NIV, standard therapy and palliative care measures.

Fifth, as the case vignette mirrors a specific clinical situation and the respondent cohort is a narrowly selected population, it is not possible to extrapolate our results into any other area of end-of-life decisions where similar questions may be asked, e.g. in neonatology for children facing limited life expectancy.

Sixth, due to the study design (as the primary aim of the study was to uncover differences and only secondary to find potential relationships), causality cannot be inferred.

Interpretation, relevance and remedies

Even though decisions under uncertainty are typically multifactorial, we assume the differences in the chosen treatment pathways are likely caused by an availability bias, as respondents tended to vote for therapies that they use regularly and know well. Also, it may be inferred that practical knowledge of certain treatments like NIV is limited. Additionally, different medicoethical values and beliefs may affect decision making at a group and a personal level.

As physician age seems to be predictive against a decision for NIV, it can be hypothesised that factors like greater experience lead to better prognostic judgement and less aggressive proceedings. It is also possible that knowledge of newer therapies decreases with increasing physician age. This is supported by the observation that physician age was not a predictor for or against palliative therapy.

Even though the participating physicians were very experienced and regularly made end-of-life decisions, half of them indicated that these decisions were emotionally stressful for them.

The differences observed in the survey with regard to treatment of end-stage COPD patients may possibly result in over- or undertreatment of this highly vulnerable patient group. In the case of overtreatment, patients who have very low life expectancy and very limited health-related quality of life might be subjected to useless and even burdensome interventions ( e.g. invasive mechanical ventilation), which might even decrease quality of life and prolong suffering. Conversely, in the case of undertreatment, patients might be denied access to beneficial interventions such as NIV.

We believe a remedy to be the continued medical education of all healthcare professionals about the scope of interventions in COPD. In addition, medical ethics and medical decision making should be an integral part of every physician's education, as well as joint educational formats (fostering peer-to-peer interaction across specialties). Local clinical ethics committees could be of additional help.

Physicians from different departments make different treatment decisions in end-stage COPD patients with acute exacerbations. This may lead to over- or undertreatment. Therefore, further research about treatment decision heuristics and influential factors in this special situation, as well as training in ethics, end-of-life decision making and coping strategies, is of paramount importance.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Questionnaire 00163-2018.supp1 (1.2MB, pdf)

Questions and results 00163-2018.supp1 (1.2MB, pdf)

Acknowledgement

This study was conducted as a thesis project by M. Gäbler at Danube University Krems (Krems, Austria) in 2016 (Medizinethischen Entscheidungen am Lebensende – Für welche prinzipielle Therapie entscheiden sich Ärztinnen und Ärzte bei einem geriatrischen End-Stage-COPD-Patienten? Eine Querschnittsbefragung [Medical Ethical Decisions at the End of Life – Which Principal Therapy Do Physicians Choose for a Geriatric End-Stage COPD Patient? A Cross-Section Survey]). Results were presented in part at conferences in Austria [ 35 ].

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com

Conflict of interest: M. Gäbler has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Ohrenberger has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G-C. Funk reports a speaker fee from AstraZeneca, service on an advisory board for GSK, a speaker fee from and service on an advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim, and a speaker fee from Orion Pharma, outside the submitted work.

- 1. Gibson GJ, Loddenkemper R, Lundbäck B, et al. . Respiratory health and disease in Europe: the new European Lung White Book. Eur Respir J 2013; 42: 559–563. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Klimathianaki M, Mitrouska I, Georgopoulos D. Management of end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease In: Siafakas NM, ed. Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (ERS Monograph) . Sheffield, European Respiratory Society, 2006; pp. 430–450. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Pavord I, Jones P, Burgel PR, et al. . Exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11: 21–30. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Taylor DR, Murray SA. Improving quality of care for end-stage respiratory disease: changes in attitude, changes in service. Chron Respir Dis 2018; 15: 19–25. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Creagh-Brown B, Shee C. Noninvasive ventilation as ceiling of therapy in end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis 2008; 5: 143–148. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Quill CM, Quill TE. Palliative use of noninvasive ventilation: navigating murky waters. J Palliat Med 2014; 17: 657–661. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2018. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf Date last accessed: June 10, 2018.

- 8. Wedzicha JA, Miravitlles M, Hurst JR, et al. . Management of COPD exacerbations: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1600791. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Carlucci A, Guerrieri A, Nava S. Palliative care in COPD patients: is it only an end-of-life issue? Eur Respir Rev 2012; 21: 347–354. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Roberts CM, Lopez-Campos JL, Pozo-Rodriguez F, et al. . Team on behalf of the ECA. European hospital adherence to GOLD recommendations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation admissions. Thorax 2013; 68: 1169–1171. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Vermylen J, Szmuiowicz E, Kalhan R. Palliative care in COPD: an unmet area for quality improvement. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015; 10: 1543–1551. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Diaz-Lobato S, Smyth D, Curtis JR. Improving palliative care for patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 596–598. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. López-Campos JL, Hartl S, Pozo-Rodriguez F. Variability of hospital resources for acute care of COPD patients: the European COPD Audit. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 754–762. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Sprung CL, Carmel S, Sjokvist P, et al. . Attitudes of European physicians, nurses, patients, and families regarding end-of-life decisions: the ETHICATT study. Intensive Care Med 2007; 33: 104–110. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Gabbay E, Calvo-Broce J, Meyer KB, et al. . The empirical basis for determinations of medical futility. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25: 1083–1089. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Jox RJ, Schaider A, Marckmann G, et al. . Medical futility at the end of life: the perspectives of intensive care and palliative care clinicians. J Med Ethics 2012; 38: 540–545. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Meyer TE, Kiernan MS, McManus DD, et al. . Decision-making under uncertainty in advanced heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2014; 11: 188–196. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Council of Europe. Guide on the Decision-making Process Regarding Medical Treatment in End-of-life Situations 2014. www.coe.int/t/dg3/healthbioethic/conferences_and_symposia/Guide%20FDV%20E.pdf Date last accessed: April 9, 2016.

- 19. Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical Ethics: A Practical Approach to Ethical Decisions in Clinical Medicine . 8th edn New York, McGraw-Hill, 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics . 7th edn New York, Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Kayyali R, Odeh B, Frerichs I, et al. . COPD care delivery pathways in five European Union countries: mapping and health care professionals’ perceptions. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11: 2831–2838. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Pearlman RA, Jonsen A. The use of quality-of-life considerations in medical decision making. J Am Geriatr Soc 1985; 33: 344–352. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Regueiro C, Hamel M, Davis R, et al. . A comparison of generalist and pulmonologist care for patients hospitalized with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: resource intensity, hospital costs, and survival. Am J Med 1998; 105: 366–372. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. McNeely PD, Hébert PC, Dales RE, et al. . Deciding about mechanical ventilation in end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: how respirologists perceive their role. CMAJ 1997; 156: 177–183. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Nava S, Sturani C, Hartl S, et al. . End-of-life decision-making in respiratory intermediate care units: a European survey. Eur Respir J 2007; 30: 156–164. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Converse L, Barrett K, Rich E, et al. . Methods of observing variations in physicians’ decisions: the opportunities of clinical vignettes. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 586–594. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, et al. . Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: a prospective validation study. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141: 771–780. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Veloski J, Tai S, Evans AS, et al. . Clinical vignette-based surveys: a tool for assessing physician practice variation. Am J Med Qual 2005; 20: 151–157. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Katz MH. Study Design and Statistical Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians . Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Katz MH. Multivariable Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians and Public Health Researchers . 3rd edn Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Stoltzfus JC. Logistic regression: a brief primer. Acad Emerg Med 2011; 18: 1099–1104. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Malhotra C, Chan N, Zhou J, et al. . Variation in physician recommendations, knowledge and perceived roles regarding provision of end-of-life care. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14: 52. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Delgado A, Saletti-Cuesta L, López-Fernández LA, et al. . Gender inequalities in COPD decision-making in primary care. Respir Med 2016; 114: 91–96. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, et al. . Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 2000; 283: 1715–1722. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Gäbler M. Medizinethische Entscheidungen am Lebensende. [Medical ethical decisions at the end of life.] Z Gerontol Geriatr 2017; 50: Suppl. 1, S9. [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (587.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO