An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.3(5); 2017 May

Dietary diversity and child malnutrition in Ghana

Raymond boadi frempong.

a Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies, University of Bayreuth, Germany

Samuel Kobina Annim

b Department of Economics, University of Cape Coast, Ghana

The health of children in Ghana has improved in recent years. However, the current prevalence rates of malnutrition remain above internationally acceptable levels. This study, therefore, revisits the determinants of child health by using Ghana’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey to investigate the effect of infant feeding practices on child health. We used the World Health Organization’s Infant and Young Children Feeding guidelines to measure dietary quality. The econometric analyses show that dietary diversity may cause improvement in children’s health in Ghana. This suggests that educational campaigns on proper infant feeding and complementary dieting could be an effective means of improving the health of children in Ghana.

1. Introduction

The importance of nutrition has been emphasized for the intellectual and physical development of children. It is, therefore, important to ensure that children have adequate diet as it will ensure a healthy and productive population in future. The benefits of adequate nutrition to the economy come directly in the form of reduced public health expenditure on health care and indirectly through improved health, which may lead to economic growth ( Hoddinott et al., 2008 ). Because of the importance of nutrition in human and economic development, pragmatic steps, both at sub-national, national and international levels, have been taken to reduce the incidence of malnutrition. The importance development practitioners attach to nutrition is reflected in targets 1C and 4A of the first Millennium Development Goal’s (MDG), which identify the need to reduce hunger and mortality among children under five years of age. In spite of the various interventions, about 870 million people were malnourished globally between 2010 and 2012 (FAO, 2012), with a sizeable proportion of this is found in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia ( UNICEF, WHO & World Bank, 2015 ). Also, women and children tend to be the most affected ( Bain et al., 2013 ). According to UNICEF, WHO & World Bank’s (2016) joint child malnutrition estimates, about 32 percent of children in Africa are stunted whilst another 8 percent are wasting. Malnutrition at the early stages of life does not only affect health outcomes of the child, but it also has a serious adverse impact on the determinants of their livelihoods, such as physical and intellectual growth, school performance and eventual future earnings and productivity ( Hoddinott et al., 2008 ; Strauss and Thomas, 1998 ). As individuals get locked up in a vicious cycle of poor health, lower learning capacity, reduced physical activity, and lower productivity as a result of poverty, malnutrition and poor child health nexus, the gains from previous economic growth may be threatened ( Bagriansky, 2010 ).

Some countries in Africa, including Ghana, have made marginal, but steady, gains in reducing malnutrition among children less than five years ( ICF Macro, 2010 ). However, according to the last Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS4), 13 percent of children in Ghana are moderately or severely underweight, 23 percent are stunted (too short for their age.), and 6 percent are wasting (too thin for their height.) ( Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), 2011 ). Fig. 1 presents the nutritional status of children according to the Ghana Demographic Health Survey (GDHS, rounds I −V) and MICS4. The graph shows varying trends for overweight, stunting, underweight and wasting among children aged 5 to 59 months in Ghana. The graph shows that child stunting and underweight have reduced since 2003, even though the proportion of children who are stunted in Ghana is still higher than the global average of 25 percent ( UNICEF, 2013 ). On the other hand, child wasting and overweight rose between 2003 and 2008. Both indicators increased by 1 percent between 2003 and 2008. Similarly, the GDHS estimate of child wasting is higher than the global estimate of five (5) percent ( UNICEF, 2013 ). Whilst these figures are encouraging when they are benchmarked against other African countries ( UNICEF, WHO & World Bank, 2016 ), they are still above the World Health Organization’s (WHO) classification of low prevalence. Thus, notwithstanding this progress, there is the need to investigate the drivers behind malnutrition in Ghana. This has become necessary given the fact that there has not been a steady downward trend for some indicators.

Nutritional Status of Children under Five Years in Ghana from the GDHS I–V and Ghana MICS-4. (Source: ICF Macro (2010) and GSS (2011) ).

Following UNICEF’s (1990) conceptual framework on the causes of malnutrition, researchers have attempted to explain the role of quality diet in reducing child malnutrition. The empirical literature is replete with the assessment of complementary feeding and its effect on children’s health and nutrition ( Dewey and Adu-Afarwuah, 2008 ; Saha et al., 2008 and Vaahtera et al., 2001 ). The results from these studies suggest that proper complementary feeding could be effective in improving the health of children below the age of five years. In line with these findings, this paper studies the effect of dietary diversity as means of improving child health in Ghana.

Whilst UNICEF’s (1990) conceptual framework links food security to child nutrition, the relationship is not as simple as demonstrated by the framework. Given the fact that food security as a concept is multifaceted, the transmission mechanism of food security to better nutrition can either run from food availability in terms of quantity and quality or sustainability. Thus, policy intervention aimed at improving nutrition through food security may have different impacts, based on which aspect is targeted. In addition, the relationship between food security and child nutrition could be more complex, based on the level of the analysis and the interactions of social, environmental and cultural practices. Government policy can improve child nutrition by ensuring food security at the household or at the individual (child and mother) level. However, depending on which level is targeted, the transmission mechanism will differ and the desired impact may be achieved at different time intervals. In view of these complexities, the current study seeks to test the hypothesis that the consumption of a diversified diet leads to better child nutrition. To the best of our knowledge, this study is different from other studies conducted on the subject to the extent that we take care of the endogeneity between dietary diversity and child health outcomes.

The next section of the paper discusses the methodology, then we present results and discussion and finally draw conclusions from the study.

2. Methodology

Data for the study was obtained from the fourth round of the Ghana Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS4) collected in 2011. The MICS4 was conducted by the GSS as part of a broader international household survey designed by the UNICEF. The aim of the survey is to provide current information on the socio-economic circumstances of children and women by measuring key indicators relating to the MDGS ( GSS, 2011 ). MICS4 is, therefore, a cross-sectional survey that provides current information on the health, social and economic circumstances of women, children and other household members. To obtain the sample for the survey, rural and urban areas in the ten administrative regions of Ghana were used as the main sampling strata. The final sample was selected in two stages. In the first stage, enumeration areas were selected with the probability of selection being proportional to the size. Then 15 households in each enumeration area were systematically selected. Eventually, 12,150 households were successfully sampled and interviewed. This consists of 11,925 households, 10,627 women aged 15 to 49 year and 7550 under the age of five years ( GSS, 2011 ). After cleaning a merging the various data files, we 6598 children remained for the regression analysis.

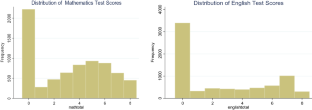

2.2. Measurement of dietary diversity

To measure dietary quality, we adopt the WHO’s Infant and Young Children Feeding guidelines (IYCF), because they are designed to measure dietary diversity for both breastfed and non-breastfed children. Also, the dataset used in the analysis contains information on the food items that can be used to calculate this indicator. The section of the survey on children collected information on food and liquids a child consumed in the previous day. We categorized these food items into seven major food groups based on the WHO’s IYCF guidelines ( Swindale and Bilinsky, 2006 ). These food groups are: (i) grains, roots, and tubers; (ii) legumes and nuts; (iii) flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry and liver/organ meats); (iv) eggs; (v) vitamin A rich fruits and vegetables; (vi) dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese); (vii) other fruits and vegetables. If a child consumed at least one food item from a food group, the group was assigned a value of one for that child. The group scores are then summed to obtain the dietary diversity score, which ranges from zero to seven, where zero represents non-consumption of any of the food items and seven represents the highest level of diet diversification.

2.3. Definition of nutrition status (anthropometric indicators)

In this study, the child’s nutritional status is measured by the WHO’s (2006) anthropometric indicators: height-for-age (HAZ) is used to measure chronic malnutrition due to prolonged food deprivation; weight-for-height (WHZ) captures undernutrition due to recent food deprivation and malnutrition. Weight-for-age which is measures the child’s body mass relative to her chronologic age is used as a proxy for underweight.

2.4. Model specification and estimation technique

Based on the reviewed literature and the objective of this study we estimate the following model:

where: sex = sex of child; age = age of child; numchildren = number of children in household; urban = whether household is in an urban area; mage = mother ’ s age; medu = mother ’ s education; wealth = wealth quintile; water = source of water; toilet = type of toilet; food = food diversity score; Bmilk = child ever breastfed; ethnic = ethnicity of household head; region = which administrative region household is located in; y j = ( W A Z , H A Z , W H Z ) are the raw z-score of the respective indicator; and i indexes individual children .

Estimating Eq. (1) with ordinary least squares (OLS) can yield a consistent estimate of the effect of dietary diversity on child health if dietary diversity is exogenous; that is uncorrelated with the error term in the model. However, this may not be the case because of the bi-causal relationship between the two variables. This bi-causal relationship is likely to arise because parents and caregivers may adopt different feeding practices depending on the current health status of the child. In this instance, the direction of causality could also run from child health to dietary diversity. If this is the case, the OLS estimates will no longer be consistent. To resolve this problem, we employed the Two Stage Least Square (TSLS) estimator to identify the causal effect of dietary diversity on child health. We used the number of chicken owned as well as household ownership of pigs as instruments for dietary diversity. We assume our instruments have no direct effect on child health outcomes but they indirectly influence it by improving the quality of diet consumed. Based on these considerations we estimate the following equations:

where f o o d i ˆ is the linearly predicted food diversity score from Eq. (2) ; pig and chicken are the number of pigs and chicken owner by the household.

3. Results and discussion

Table 1 presents the bivariate relationship between children’s nutritional outcomes, on the one hand, and individual and household characteristics, on the other hand. We find that approximately 25 percent of male children are stunted as compared to 20 percent of females. Similarly, 7.6 percent and 15.6 percent of male children are wasted and considered underweight respectively, whilst 5.2 and 11 percent of female children are wasted and underweight. In all cases, the incidence of malnutrition tends to be higher among male children than female children. This situation could be attributed to differences in biological composition and caregiving; and possibly due to daughter preference ( Fuse, 2010 ).

Bivariate analysis of socioeconomic variables and anthropometric indicators.

Source: Authors’ Computation from MICS4, 2011 .

One can also observe that the difference between the incidence of malnutrition over the different age groups is statistically significant. It is important to note that in all the three cases the proportion of malnourished children increases with age up to age 35 months and then falls, thus, suggesting a non-linear relationship between child age and nutritional status. Apart from stunting, we observe significant differences in the prevalence of wasting and underweight among children who had suffered from fever in the past two weeks and those who had not.

On the association between dietary diversity and child health, Table 1 shows that malnourishment varies significantly for the different levels of consumption. About a quarter of children who consumed at least four of the seven food items are stunted: 5 percent of this group were wasted and another 12 percent were underweight. The prevalence of wasting and child underweight begins to decline after the intake of two or more food items. Thus, child health improves as the intensity of dietary diversity increases.

Sanitation factors such as the type of toilet facility and the source of drinking water also tend to have a significant association with child health in Ghana. About 30 percent of children found in households where the bush or bucket are used as toilet facility is stunted, whilst only 10 percent of their counterparts in households with flush toilets are stunted. Similarly, only 4 percent of children found in households with flush toilets are wasted as compared to 7 percent of children found in households which neither use flush toilet nor pit latrine. The incidence of malnutrition decreases as the source of drinking water improves. For instance, the prevalence of child underweight falls from 17 percent among those who use unprotected water sources to 11 percent among those who use pipe-borne water. Good sanitation and water supply improve health by reducing infections and malnutrition ( Cuesta, 2007 ).

We also find that wealthier households have children with better nutritional status than poorer households. About a third of children born to poor parents are stunted. Equally, one-fifth of children born into poor households are underweight compared to only 6 percent of those in the richest households. A similar pattern was observed by Urke et al. (2011) , who found that wealth status and maternal education are positively associated with child health outcomes. In addition, we observe a positive relationship between maternal education and child health outcomes. The effect of dependence and competition for care is also felt through the number of children in the household. Table 1 shows that child nutritional status worsens as the number of children increases. This could be because of competition for care and resources in the household.

3.1. Feeding pattern in Ghana by child age groups

Fig. 2 provides a description of dietary diversity across different child age groups and it shows that in Ghana a majority of children (47%) consume a minimum of four out of the seven food groups. About a quarter of them had three food groups whilst 13 percent had none of the food groups. In addition, more than 80 percent of infants, aged zero to five months, can be assumed to be undergoing exclusive breastfeeding since they consumed none of the food items. Observable from Fig. 2 is how food diversity increases with child age. For instance, whilst only 0.5 percent of children who are under 6 months of age had at least four of the food items, the proportions increased to 49 percent among those aged 12 to 23 months and 61 percent among those aged 48 to 59 months. The pattern portrayed by this graph indicates that parents and caregivers see the need to vary their children’s diet within the first five years.

Feeding Pattern in Ghana by child age groups. (Source: Authors’ Computation from MICS, 2011).

3.2. Maternal education and food diversity

In Table 2 we test whether dietary diversity for children is statistically different across levels of maternal education. The table shows that children born to parents with higher levels of education had a more diversified diet. We found that children whose mothers have primary, middle/Junior High School (JHS) or at least secondary school education are significantly likely to consume more diversified diet than those whose mothers have no education. However, we fail to find any statistical difference in child feeding among those whose parents had received some form of formal education. Thus, as far as child feeding is concerned the feeding pattern of children who are born to parents with only primary education is not statistically different from those who are born to mothers with either middle/JHS or secondary school education. This suggests that intensifying nutrition education at basic/primary school level could also be an effective approach to fighting malnutrition.

Dietary diversity across levels of maternal education.

+ p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Source: Authors’ Computation from MICS, 2011 .

3.3. Regional distribution of food diversity among children under 6 years

In terms of regional differences in dietary pattern, Fig. 3 shows that children in the Volta region had the most diversified diet. This is followed by Greater Accra, which is the national capital. One would have expected regions like Eastern and Western to have better food diversity than Upper West and Upper East regions since the poverty rates in the former are lower than the latter region; however, the graph portrays a different picture. This could be as a result of the fact that most of the households in the Upper East and West regions are peasant farmers who grow a wide range of crops and, rear different domestic animals which serve to improve dietary diversity. The average dietary diversity of children in the Northern, Western and Eastern regions are less than the national average of 3.12. The implication of this of this pattern on children’s nutrition is seen in Table 1 , where the regions with low dietary diversity are also the ones with a high incidence of child malnutrition.

Distribution of Food Diversity by Administrative Regions in Ghana. (Source: Authors’Computation from MICS, 2011).

3.4. Estimation results

This paper set out to study the effects of dietary diversity on child health outcomes. To this end, anthropometric indicators of child health were regressed on dietary diversity, maternal education, ethnicity and other covariates of child health. The OLS and TSLS result of the effect of dietary diversity on child anthropometric indicators are presented in Table 3 . The first stage results for the TSLS are reported in column 7. Table 3 indicates that dietary diversity has a positive effect on child health outcomes. This relationship is observed in all the models, except for the IV model for weight-for-age. Thus, Increasing the number of food groups a child consumes by one causes HAZ and WAZ to increase by 0.65 and 0.52 units respectively. Thus, we find a consistent positive association between dietary diversity and better child health outcomes.

Effects of food diversity, mother's education and ethnicity on child health outcomes in Ghana (all children under 5 years).

On the effect of ethnicity on child health, we find in Table 3 that children from the Ewe, Grusi, Guan and Mole/Dagbani ethnic groups have better anthropometric scores than those from the Akan ethnic group. This result shows that ethnicity may have an important influence on child health in Ghana. This may be attributed to differences in feeding and post-partum practices across the different ethnic groups. Elsewhere, Adedini et al. (2015) and Annim and Imai (2014) have found that child health outcomes differ among children of different ethnic descent in Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

We also observe that an increase in the number of children in the household worsens the child's health. The table shows that an additional child in the household is associated with a 0.2 lower WHZ and a 0.3 lower scores in both WAZ and HAZ. Annim, Awusabo-Asare, Amo-Adjei (2013) argued that as the number of children in a household increase, children may have to compete for both household resources and caregiving. This may cause each child to receive sub-optimal care and resources to achieve the desired nutritional status. In line with our observation in Table 1 , male children tend to have lower weight-for-age and height-for-age than their female counterparts. The observed relationship between sex and nutritional status could be because of biological differences as well as socio-cultural differences. Socio-culturally, gender preferences, and preferential treatment may account for the observed coefficient. Indeed, Fuse (2010) has shown that daughter preference is slightly higher than son preference in Ghana.

In addition, children who had diarrhea have lower anthropometric scores compared to those who did not. Infections that lead to diarrhea and fever adversely affect nutritional status by reducing dietary intake and intestinal absorption and increasing catabolism and sequestration of nutrients which are essential for growth ( Brown, 2003 ). However, we fail to see this effect in the case of HAZ for children who had a fever. We also observe a negative relationship between child’s age and nutritional status.

As expected, household wealth positively correlates with height-for-age and weight-for-height. Children born to families within higher wealth quintiles tend to have better nutritional status as compared to those born to households within the poorest wealth quintile. For HAZ and WAZ, the effect of household wealth and child nutritional status falls between those in the second and middle quintiles but increases between the fourth and the richest quintiles. This suggests that the relationship between wealth and child health may not be linear. Conversely, weight-for-height is worse among children in the second and middle wealth quintiles as compared to those in the poorest wealth quintile.

Regional fixed effects are significant in explaining child nutrition. With the Western region as the base, we observe that except for Greater Accra, children in the other regions have lower weight-for-age than those in the Western region. Similarly, children in Northern, Upper East, and Upper West regions are worse off in terms of weight-for-height than their counterparts in the Western region. Interestingly the difference between the anthropometric score of children in the Western region and the three northern regions tends to be higher. This could be attributable to the high poverty and deprivation rates in this region.

3.5. Proportional selection assumption test

Following Oster (Oster, 2014) we test whether the omission of unobservable factors may significantly bias the observed coefficients of dietary diversity in our models. The test assumes that an inference can be made about the possible bias that could be caused by the omission of unobservable factors by observing the movement of the coefficient by successively including observable independent variables. The idea of the test is that if the inclusion of additional explanatory variables improves the R 2 but leaves the coefficient relatively unchanged, then one can be confident that the coefficient is relatively stable. Based on this, it can be concluded that the coefficient will remain relatively unchanged if the unobservable factors were added. Table 4 contains the results of the test. We select an R 2 cutoff of 30 percent, because studies in this are usually report R 2 around 20 percent (see Arimond and Ruel (2004) for a cross country study and the respective R 2 ). We found that, except for the WHZ model, the identified set always excludes zero. This is means that even though these models do not include all the potential explanatory variables, the effect of dietary diversity will be different from zero if we were to observe these variables.

Proportional Selection Assumption.

δ = 1 , R m a x 2 = 3 .

4. Discussion and conclusion

Because of the long-lasting effect of malnutrition on human development at later stages in life, children’s nutrition has engaged the attention of policy makers and researcher for several years. This has led to the prescription of various interventions to deal with child malnutrition, of which dietary diversity is an integral part. The association between dietary diversity and child health outcomes has been explored by researchers in some developing countries. In view of the evidence from these studies, the current study sought to investigate the causal effect of dietary diversity on child health outcomes in Ghana.

Food diversity, the independent variable of interest, was captured as a continuous variable from the count of the number of food groups from which a child had food in the previous day before the survey. These food groups are based on the WHO’s IYCF guidelines. The dependent variable, child health, was measured with three anthropometric indicators: weight-for-age (wasting), weight-for-height (stunting) and weight-for-height (underweight). We employed both bivariate and multivariate analyses to evaluate the effect of dietary diversity on child health. We found that there is a general trend towards higher dietary diversity as the child grows in age. We consider this as a good trend for child nutrition, as parents and caregivers see the need to meet the nutritional requirements of their wards in the growth process. Dietary diversity is also significantly higher for children from mothers with higher education. This was consistent with our apriori expectation since educated mothers know the importance of a balanced diet for their children. This also puts education as one of the important tools that policy makers can adopt to improve nutritional adequacy among infants and young children. This can be achieved by making nutrition awareness an integral part of the school curriculum, especially at the basic level. Since more than half of the respondents in our sample had had no formal education, we recommend that nutrition awareness should also be created outside the classroom through avenues like the mass media and informal education. The government of Ghana can take advantage of the existing information service department as well the flourishing community information centers to provide informal education on nutrition, especially in rural Ghana.

In general, our analysis shows that dietary diversity causes improvements in child health among under five-year-olds in Ghana. We interpret this results with caution because dietary diversity was measured over a one-day recall period which may not be an accurate reflection the dietary pattern for a longer period. Despite this limitation, our results show a consistent relationship across all the three anthropometric indicators. We recommend that public health officials should educate parents and caregivers on the importance of dietary diversity to their children. The government could also take advantage of the structures of the national school feeding program to diversify the diet of the school children. Our analysis of the effects of each individual food groups on child health shows that vitamin A rich food (pumpkin, yellow yam, green vegetables [kontomire] mangoes and pawpaw), eggs and other vegetables have a positive association with the weight-for-age score. Hence, given the right nutritional education, malnutrition among children in rural areas could be minimized at a relatively lower cost because these food items tend to be inexpensive in rural farming communities.

Declarations

Author contribution statement.

Raymond Boadi Frempong, Samuel Kobina Annim: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

- Adedini S.A., Odimegwu C., Imasiku E.N., Ononokpono D.N. Ethnic differentials in under-five mortality in Nigeria. Ethn. Health. 2015; 20 (2):145–162. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Annim S.K., Imai K.S. Nutritional Status of Children. Food Consumption Diversity and Ethnicity in Lao PDR. 2014 (No. DP2014-17) [ Google Scholar ]

- Annim S.K., Awusabo-Asare K., Amo-Adjei J., ICF International Household Nucleation, Dependency and Child Health Outcomes in Ghana. DHS Working Papers. August 2013 http://www.measuredhs.com/publications/publication-wp98-working-papers.cfm [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arimond M., Ruel M.T. Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. J. Nutr. 2004; 134 (10):2579–2585. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bagriansky J. UNICEF; Albania: 2010. The economics consequences of malnutrition in Albania. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bain L.E., Awah P.K., Geraldine N., Kindong N.P., Sigal Y., Bernard N., Tanjeko A.T. Malnutrition in Sub − Saharan Africa: burden, causes, and prospects. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2013; 15 :120. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown K.H. Diarrhea and Malnutrition. J. Nutr. 2003; 133 (1):328S–332S. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cuesta J. Child Malnutrition and the Provision of Water and Sanitation in the Philippines. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy. 2007; 12 (2):125–157. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dewey K.G., Adu-Afarwuah S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern. Child Nutr. 2008; 4 (Suppl. 1):24–85. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuse K. Variations in attitudinal gender preferences for children across 50 less-developed countries. Demographic Research. 2010; 23 (36):1031–1048. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghana Statistical Service . Ghana Statistical Service; Accra, Ghana: 2011. Ghana Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey with an Enhanced Malaria Module and Biomarker, (Final Report) [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoddinott J., Maluccio J.A., Behrman J.R., Flores R., Martorell R. Effect of a nutrition intervention during early childhood on economic productivity in Guatemalan adults. Lancet. 2008; 371 (9610):411–416. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- ICF Macro . ICF Macro; 2010. Trends in demographic, family planning, and health indicators in Ghana, 1960-2008: Trend analysis of demographic and health surveys data. [ Google Scholar ]

- Saha K.K., Frongillo E.A., Alam D.S., Arifeen S.E., Persson L.Å., Rasmussen K.M. Appropriate infant feeding practices result in better growth of infants and young children in rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008; 87 (6):1852–1859. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Strauss J., Thomas D. Health, nutrition, and economic development. J. Econ. Lit. 1998; 36 (2):766–817. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swindale A., Bilinsky P. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development; Washington, DC: 2006. Household dietary diversity score (HDDS) for measurement of household food access: indicator guide. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNICEF . UNICEF; New York: 2013. Improving child nutrition: The achievable imperative for global progress. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNICEF, WHO, World Bank . Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition; 2015. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2015 edition. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNICEF, WHO, World Bank . Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition; 2016. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2016 edition. [ Google Scholar ]

- Urke H.B., Bull T., Mittelmark M.B. Socioeconomic status and chronic child malnutrition: Wealth and maternal education matter more in the Peruvian Andes than nationally. Nutr. Res. 2011; 31 (10):741–747. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaahtera M., Kulmala T., Hietanen A., Ndekha M., Cullinan T., Salin M.L., Ashorn P. Breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in rural Malawi. Acta Paediatr. 2001; 90 (3):328–332. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Open access

- Published: 28 November 2007

Malnutrition and the disproportional burden on the poor: the case of Ghana

- Ellen Van de Poel 1 , 2 ,

- Ahmad Reza Hosseinpoor 3 ,

- Caroline Jehu-Appiah 4 ,

- Jeanette Vega 3 &

- Niko Speybroeck 5

International Journal for Equity in Health volume 6 , Article number: 21 ( 2007 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

73 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Malnutrition is a major public health and development concern in the developing world and in poor communities within these regions. Understanding the nature and determinants of socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition is essential in contemplating the health of populations in developing countries and in targeting resources appropriately to raise the health of the poor and most vulnerable groups.

This paper uses a concentration index to summarize inequality in children's height-for-age z-scores in Ghana across the entire socioeconomic distribution and decomposes this inequality into different contributing factors. Data is used from the Ghana 2003 Demographic and Health Survey.

The results show that malnutrition is related to poverty, maternal education, health care and family planning and regional characteristics. Socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition is mainly associated with poverty, health care use and regional disparities. Although average malnutrition is higher using the new growth standards recently released by the World Health Organization, socioeconomic inequality and the associated factors are robust to the change of reference population.

Child malnutrition in Ghana is a multisectoral problem. The factors associated with average malnutrition rates are not necessarily the same as those associated with socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition.

In the developing world, an estimated 230 million (39%) children under the age of five are chronically malnourished and about 54% of deaths among children younger than 5 are associated with malnutrition [ 1 ]. Malnutrition is a major public health and development concern with important health and socioeconomic consequences. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of malnutrition among the group of under-fives is estimated at 41% [ 1 ]. It is the only region in the world where the number of child deaths is increasing and in which food insecurity and absolute poverty are expected to increase [ 2 – 4 ]. Malnutrition in early childhood is associated with significant functional impairment in adult life, reduced work capacity and decreasing economic productivity [ 5 – 10 ]. Children who are malnourished not only tend to have increased morbidity and mortality but are also more prone to suffer from delayed mental development, poor school performance and reduced intellectual achievement [ 6 – 8 ].

Chronic malnutrition is usually measured in terms of growth retardation. It is widely accepted that children across the world have much the same growth potential, at least to seven years of age. Environmental factors, diseases, inadequate diet, and the handicaps of poverty appear to be far more important than genetic predisposition in producing deviations from the reference. These conditions, in turn, are closely linked to overall standards of living and the ability of populations to meet their basic needs. Therefore, the assessment of growth not only serves as one of the best global indicators of children's nutritional status, but also provides an indirect measurement of the quality of life of an entire population [ 11 – 13 ].

Large scale development programs such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have also emphasized the importance of the under-fives' nutritional status as indicators for evaluating progress [ 14 ]. When aiming at reducing childhood malnutrition, it is important not only to consider averages, which can obscure large inequalities across socioeconomic groups. Failure to tackle these inequalities may act as a brake on making progress towards achieving the MDGs and is a cause of social injustice [ 15 , 16 ].

Against this background, Ghana provides an interesting case study. The country experienced remarkable gains in health from the immediate post independence era. Life expectancy improved over the years and the prevention of a range of communicable diseases improved child survival and development. However in the last decade despite increasing investments in health, Ghana has not achieved target health outcomes. There has been no significant change in Ghana's under-five and infant mortality rates between 1993 and 2003. In the last couple of years, under-five mortality was actually slightly increasing. Life expectancy has also fallen from 57 years in 2000 to 56 years in 2005 [ 17 ]. Ghana's Human Development Index (HDI), a measure combing life expectancy, literacy, education and standard of living, has been worsening too; after improving from 0.444 in 1975 to 0.563 in 2001, the HDI dropped to 0.520 in 2005 [ 15 ]. Since 1988, there has been no definite trend in malnutrition (in terms of height-for-age). Apparent gains between 1988 and 1998 were reversed in 2003 [ 18 ]. Although the 2003 Ghana Demographic Health Survey (DHS) final report [ 17 ] recommends caution when using data from the various DHS to assess the trend in the nutritional status, it is noted that there was a trend over the past five years of increased stunting compared to a decrease of wasting and underweight. Further, there has been a trend of continued high values of stunting in the North compared to the South [ 17 , 19 ].

Malnutrition in Ghana has been most prevalent under the form of Protein Energy Malnutrition (PEM), which causes growth retardation and underweight. About 54% of all deaths beyond early infancy were associated with PEM, making this the single greatest cause of child mortality in Ghana [ 20 ].

A paradigm shift in Ghanaian health policy has been taking place in 2006. The theme for the new health policy in Ghana was 'Creating Wealth through Health". One of the fundamental hypotheses of this policy was that improving health and nutritional status of the population would lead to improved productivity, economic development and wealth creation [ 21 ]. Since this policy adopted an approach that addressed the broader determinants of health, it has thus generated interest in socio-economic inequalities in health and malnutrition. It was further recognised that not paying attention to malnutrition inequalities during the early years of life is likely to perpetuate inequality and ill health in future generations and thus defeat the aims of the new health policy.

From the existing evidence it is clear that childhood malnutrition is associated with a number of socioeconomic and environmental characteristics such as poverty, parents' education/occupation, sanitation, rural/urban residence and access to health care services. Also demographic factors such as the child's age and sex, birth interval and mother's age at birth have been linked with malnutrition [ 4 , 5 , 22 – 26 ]. Previous studies have also drawn attention to the disproportional burden of malnutrition among children from poor households [ 27 – 31 ]. However, much less is known on which factors lie behind this disproportional burden. It is important to note that the most important determinants of malnutrition are not necessarily also the most important determinants of socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. [ 31 ] shows that the poorest-to-richest odds-ratio of stunting is almost halved by controlling for household and child characteristics using Ghanaian data. However, it is not clear how much each of these characteristics is contributing to this reduction. Understanding the nature and determinants of socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition is essential in contemplating the health of populations in developing countries and in targeting resources appropriately to raise the health of the poor and most vulnerable groups. This paper employs a concentration index to summarize inequality across the entire socioeconomic distribution rather than simply comparing extremes as in ratio measures. The concentration index is decomposed using the framework suggested by [ 32 ], allowing to identify the factors that are associated with socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. This decomposition takes into account that both the association of a determinant with malnutrition as well as its distribution across socioeconomic groups play a role in the extent to which it is contributing to socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. The usefulness of this approach has already been demonstrated on European data, but has known limited applications on developing countries.

Further, this paper contributes to the literature by delivering evidence on the determinants of malnutrition and socioeconomic inequality in Ghana using the new child growth standards population that has recently been released by the World Health Organization (WHO) [ 33 ]. This reference population includes children from Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman and the US. The new standards adopt a fundamentally prescriptive approach designed to describe how all children should grow rather than merely describing how children grew in a single reference population at a specified time [ 34 ]. For example, the new reference population includes only children from study sites where at least 20% of women are willing to follow breastfeeding recommendations. To our knowledge this is the first study presenting estimates of malnutrition in Ghana based upon these new standards. To check sensitivity of the results to this change in reference group, the analysis is also done using the US National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reference population [ 35 ].

The results are useful from a policy perspective as they can be used in setting policies to reduce malnutrition and the excessive burden on the poor. The results of this study are particularly relevant for Ghanaian policy makers, but can also be generalized to other settings in the sense that they show that malnutrition is associated with a broad range of factors and that the factors related to average malnutrition are not necessarily the same as those related to socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition.

Measuring malnutrition

Nutritional status was measured by height-for-age z-scores. An overview of other nutritional indices and why height-for-age is the most suited for this kind of analysis is provided in [ 36 ]. A height-for-age z-score is the difference between the height of a child and the median height of a child of the same age and sex in a well-nourished reference population divided by the standard deviation in the reference population. The new WHO child growth population is used as reference population [ 33 ]. To construct height-for-age z-scores based upon these standards, we used the software available on the WHO website [ 37 ]. To check sensitivity of the results to this change in reference group, the analysis is also done by using the US National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reference population [ 35 ].

Generally, children whose height-for-age z-score is below minus two standard deviations of the median of the reference population are considered chronically malnourished or stunted. In the regression models, the negative of the z-score is used as dependent variable ( y ). This facilitates interpretation since it has a positive mean and is increasing in malnutrition [ 32 ]. For the purpose of our analysis, using the z-score instead of a binary or ordinal variable indicating whether the child is (moderately/severely) stunted is preferred as it facilitates the interpretation of coefficients and the decomposition of socioeconomic inequality. However, binary indicators of stunting are also used in the descriptive analysis and to position Ghana within a set of other Sub-Saharan African countries.

The concentration index as a measure of socioeconomic inequality

Assume y i is the negative of the height-for-age z-score of child i . The concentration index (C) of y results from a concentration curve, which plots the cumulative proportion of children, ranked by socioeconomic status, against the cumulative proportion of y . The concentration curve lies above the diagonal if y is larger among the poorer children and vice versa. The further the curve lies from the diagonal, the higher the socioeconomic inequality in nutritional status. A concentration index is a measure of this inequality and is defined as twice the area between the concentration curve and the diagonal. If children with low socioeconomic status suffer more malnutrition than their better off peers the concentration index will be negative [ 38 ]. It should be noted that the concentration index is not bounded within the range of [-1,1] if the health variable of interest takes negative, as well as positive values. Since children with a negative y are better off than children in the reference population, they cannot be considered malnourished. Therefore their z-score is changed into zero, such that the z-scores are restricted to positive values with zero indicating no malnutrition and higher z-scores indicating more severe malnutrition.

Further, the bounds of the concentration index depend upon the mean of the indicator when applied to binary indicators, such as stunting [ 39 ]. This would impede cross-country comparisons due to substantial differences in means across countries. To avoid this problem, we used an alternative but related concentration index that was recently introduced by [ 40 ] and does not suffer from mean dependence, when comparing Ghana with other Sub-Saharan African countries.

Decomposition of socioeconomic inequality

More formally, a concentration index of y can be written as [ 38 ]:

where y i refers to the height-for-age of the i -th individual and R i is its respective fractional rank in the socioeconomic distribution. As will be discussed further in the following section, the present paper uses a continuous wealth variable, developed by principal component analysis, as a measure of socioeconomic status [see e.g. [ 41 ]].

If y i is linearly modelled

[ 32 ] showed that the concentration index of height-for-age can be decomposed into inequality in the determinants of height-for-age as follows:

where μ is the mean of y , x ¯ k MathType@MTEF@5@5@+=feaafiart1ev1aaatCvAUfKttLearuWrP9MDH5MBPbIqV92AaeXatLxBI9gBaebbnrfifHhDYfgasaacPC6xNi=xH8viVGI8Gi=hEeeu0xXdbba9frFj0xb9qqpG0dXdb9aspeI8k8fiI+fsY=rqGqVepae9pg0db9vqaiVgFr0xfr=xfr=xc9adbaqaaeGacaGaaiaabeqaaeqabiWaaaGcbaGafmiEaGNbaebadaWgaaWcbaGaem4AaSgabeaaaaa@2EEF@ is the mean of x k , C k is the concentration index of x k (with respect to socioeconomic status) and GCε is the generalized concentration index of the residuals. The latter term reflects the socioeconomic inequality in height-for-age that is left unexplained by the model and is calculated as G C ε = 2 n ∑ i = 1 n ε i R i MathType@MTEF@5@5@+=feaafiart1ev1aaatCvAUfKttLearuWrP9MDH5MBPbIqV92AaeXatLxBI9gBaebbnrfifHhDYfgasaacPC6xNi=xH8viVGI8Gi=hEeeu0xXdbba9frFj0xb9qqpG0dXdb9aspeI8k8fiI+fsY=rqGqVepae9pg0db9vqaiVgFr0xfr=xfr=xc9adbaqaaeGacaGaaiaabeqaaeqabiWaaaGcbaGaem4raCKaem4qam0aaSbaaSqaaGGaciab=v7aLbqabaGccqGH9aqpjuaGdaWcaaqaaiabikdaYaqaaiabd6gaUbaakmaaqahabaGae8xTdu2aaSbaaSqaaiabdMgaPbqabaGccqWGsbGudaWgaaWcbaGaemyAaKgabeaaaeaacqWGPbqAcqGH9aqpcqaIXaqmaeaacqWGUbGBa0GaeyyeIuoaaaa@40B6@ .

As the DHS data have a hierarchical structure, with children nested in households and households nested within communities, we have also considered using multilevel models to estimate the associations of variables with childhood malnutrition (see e.g. [ 42 ]). Allowing for random effects on the household and/or community level yielded coefficients that were similar to the ones from OLS regression corrected for clustering. Because of this similarity and because the use of multilevel models would complicate the decomposition of socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition, the remainder is based on results from linear regression corrected for clustering on the community level.

All estimation takes account of sample weights (provided with the DHS data). Statistical inference on the decomposition results is obtained through bootstrapping with 3000 replications. The bootstrap procedure takes into account the dependence of observations within clusters.

Data is used from the 2003 Ghana Demographic Health Survey (DHS) and are restricted to children under the age of 5. Anthropometric measures are missing for 12.3% of children in this age group. The final sample contains information on 3061 children. We did examine possible selection problems due to the high proportion of missing observations. A logit model explaining the selection in the sample and a Heckman sample selection model (using different exclusion restrictions) were used to check for this [ 43 ]. Both tests did not reveal large sample selection problems, and coefficients in the Heckman model were very similar to those in the model presented here.

The nutritional status of a child is specified to be a linear function of child-level characteristics such as age, sex, duration of breastfeeding, size at birth; maternal characteristics such as education, mother's age at birth, birth interval, marital status, use of health services, occupation and finally household-level characteristics such as wealth, type of toilet facility, access to safe water, number of under-five children in the household, region and urbanization. We preferred not to include information on the type of toilet and water source into the wealth indicator, as these variables can be expected to have a direct relation with children's growth apart from being correlated with household socioeconomic status [ 44 ].

The explanatory variables are described in the last column of Table 1 . All have well documented relevance in the literature [ 5 , 22 – 26 , 31 , 32 , 45 , 46 ].

No information on mother's nutritional status was included in the set of explanatory variables. Since about 10% of women in the dataset were pregnant at the time of interview, their BMI did not provide an accurate measure of their nutritional status. Furthermore, BMI reflects current nutritional status and may not be relevant for children born 5 years prior to the interview. Inclusion of mother's height-for-age had no significant effect on results.

Summary statistics

In the 2003 DHS data for Ghana, 36% of children under the age of 5 are stunted. Stunting is defined as height-for-age being below minus 2 SD from the median of the reference population. The concentration index for stunting in children under the age of 5 was -0.12 (SD = 0.016). This negative value implies that poor children had a higher probability of being stunted than their better off peers. Using the older NCHS reference study showed a lower prevalence of stunting (29%) and slightly higher socioeconomic inequality (C = -0.15, SD = 0.019).

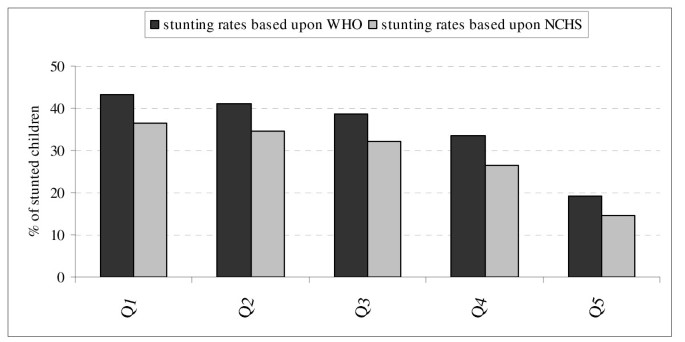

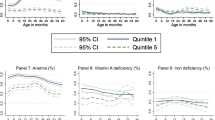

Figure 1 illustrates the strong socioeconomic inequality in childhood stunting. The stunting rate among the poorest 60 percent was more than twice the rate of children in the richest 20 percent.

Distribution of stunting across wealth quintiles.

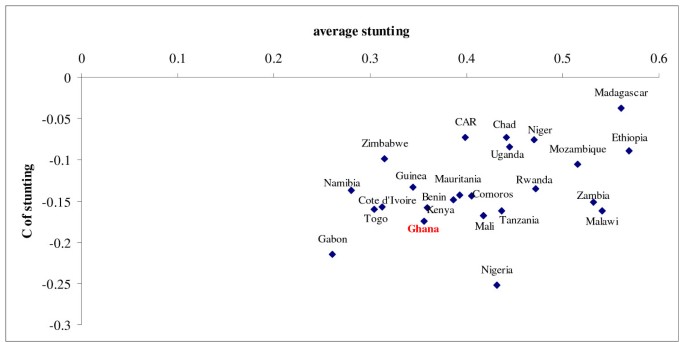

Figure 2 shows a comparative picture of stunting and socioeconomic inequality in stunting across the Sub-Saharan African region. Stunting and socioeconomic variables are calculated for each country on DHS data in exactly the same way as is described for the Ghana DHS. Summary statistics of all variables are shown in Table 1 .

Average stunting versus socioeconomic inequality in stunting in under-five children in Sub-Saharan Africa. Data from recent Demographic Health surveys. Stunting is measured using the WHO child growth standards. Concentration index as suggested by [40] is used since it is invariant to the mean of the binary variable.

Determinants of malnutrition

The regression coefficients and their significance are shown in the first column of Table 2 . Note that the dependent variable is increasing in malnutrition, such that a negative coefficient should be interpreted as lowering malnutrition.

Malnutrition increased with the child's age in a non-linear way. Children who were very small at birth had a higher probability to be stunted than children with normal size. Male children were more prone to malnutrition than their female peers. Long duration of breastfeeding is associated with higher malnutrition.

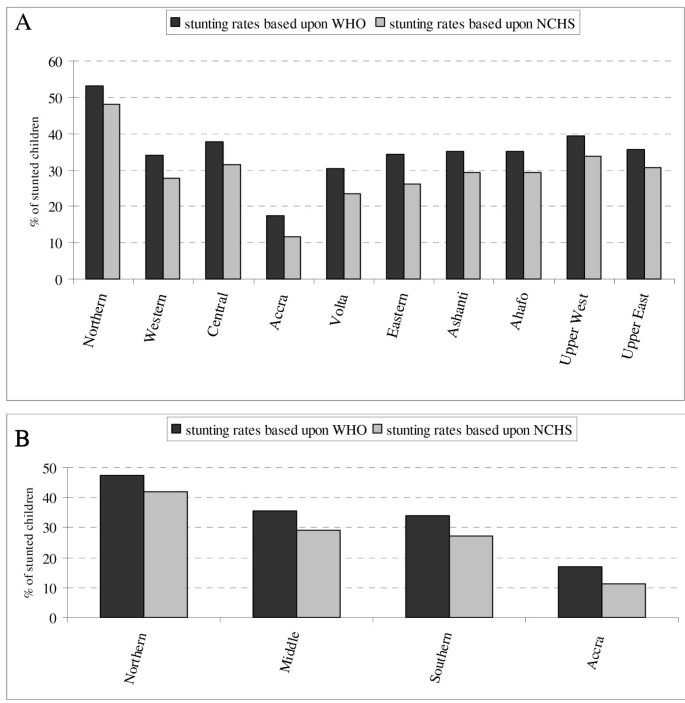

With respect to maternal characteristics, the existence of a short birth interval was significantly increasing malnutrition. Children of women that accessed health services more frequently were less prone to being malnourished. Maternal occupation showed no clear effect. Maternal education and household wealth showed a significant association with childhood malnutrition. The presence of two or more under-five children in the household was negatively associated with the child's nutritional status. Sanitation variables however had no significant association on malnutrition. As compared to the Northern region all regions were associated with lower malnutrition, especially the Accra region. The high regional disparities in malnutrition are further illustrated in Figure 3 . The four most deprived regions in Ghana (Northern, Central, Upper East and Western regions) exhibited the greatest burden of malnutrition.

Inequality in stunting by regions (A) and grouped regions (B) (as in [55]).

Decomposition of socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition

Table 2 also shows the concentration index and the relative contributions of each determinant to socioeconomic inequality in childhood malnutrition. For the ease of interpretation, the last column shows the grouped contribution from the categorical variables. A negative contribution to socioeconomic inequality implies that the respective variable is lowering socioeconomic inequality and vice versa. A variable can contribute to socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition both through its association with malnutrition and through its unequal distribution across wealth groups. The extent to which each of the explanatory variables is unequally distributed across wealth is reflected by its C value. A negative C means that the determinant is more prevalent among poorer households.

Wealth accounted for the major part (31%) of socioeconomic inequality. This part of socioeconomic inequality reflects the direct contribution of wealth. The remainder is the wealth-related inequality in malnutrition through other factors. Important contributors were regional variables (23%) and the use of health care services (18%). The age of the child was contributing negatively to socioeconomic inequality (-8%). This means that the combined effect of its coefficient and its distribution by wealth was lowering socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. Older children were more likely to be stunted and were more prevalent in higher wealth quintiles. The latter is reflected by the positive and significant C of the variable age > 12 months The contribution of the error term only amounted to about 6%, meaning that the decomposition model functioned well in explaining socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition.

Using the older NCHS reference population gave very similar regression and decomposition results are therefore not discussed (results are available upon request.).

Relative to other Sub-Saharan countries, Ghana appeared to have a rather low level of average stunting, combined with relatively high socioeconomic inequality in stunting. The use of the new WHO child growth standards yielded a higher average stunting rate as compared to the older NCHS reference group. [ 47 ] found the same for Bangladesh, Dominican Republic and a pooled sample of North American and European children. However, the variables associated with malnutrition and socioeconomic inequality were very robust to the change of the reference population.

Malnutrition in Ghanaian children rises with the age of the child, which is confirmed by other studies [ 5 , 25 , 32 ]. The higher prevalence of malnutrition among boys as compared to girls, and the negative association of long breastfeeding have also been established in the literature [ 5 , 22 , 32 , 45 ]. Long duration of breastfeeding may be associated with higher malnutrition because it reflects lack of resources to provide children with adequate nutrition [ 31 ]. It is also possible that children who are breastfed for a long time are more reluctant to eat other foods, as was found by [ 22 ] in their study on a cohort of Ghanaian children.

Short birth intervals and the presence of two or more under-five children in the household, affected childhood growth negatively by placing a heavy burden on the mother's reproductive and nutritional resources, and by increasing competition for the scarce resources within the household [ 22 ]. Children of younger mothers could be more prone to malnutrition because of physiological immaturity and social and psychological stress that come with child bearing at young age [ 48 ].

Maternal education was significantly lowering childhood malnutrition. This may reflect education generating the necessary income to purchase food. However, although education is often suggested to be a measure of social status, the coefficient stayed significant after controlling for household wealth and living conditions. A high level of maternal education could also lower childhood malnutrition through other pathways such as increased awareness of healthy behaviour, sanitation practices and a more equitable sharing of household resources in favour of the children [ 4 , 5 , 49 ].

Sanitation in terms of having a toilet and access to safe water did not significantly affect malnutrition. [ 26 ] also reported this result, but they did find a significant association between sanitation and wasting (which reflects current nutritional status). This might suggest that good sanitation can avoid episodes of diarrhoea and hereby affect current nutritional status, while it may not be sufficient for long term child growth.

The higher levels of malnutrition of the population living in the northern regions of Ghana have already been observed more than a decade ago [ 23 ]. This regional pattern reflects ecological constraints, worse general living conditions and access to public facilities in the Northern regions. In addition, the persistence of this regional inequality can point to an intergenerational effect of malnutrition. Since women who were malnourished as children are more likely to give birth to low-birth-weight children, past prevalence of child malnutrition is likely to have an effect on current prevalence.

The high socioeconomic inequality in childhood malnutrition is -apart from wealth itself-mainly associated with regional characteristics and use of health care services. Wealth was responsible for about one third of the socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. This means that poorer children were more likely to be malnourished, mainly because of their poverty. The regional contribution results from the fact that poorer children are more likely to live in regions with disadvantageous characteristics. Given the strong regional associations with malnutrition, after controlling for a broad range of socioeconomic and demographic covariates, there must be other important regional aspects. The regional inequality in Ghana originates from both geographical and historical reasons. Much of the North is characterized by lower rainfall, savannah vegetation, periods of severe drought and remote and inaccessible location. Further, the colonial dispensation ensured that northern Ghana was a labor reserve for the southern mines and forest economy and the post-colonial failed to break the established pattern [ 19 ].

Health services use was also responsible for a substantial proportion of socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. This derives from the combined effect of the positive associations between health services use and childhood growth and the unequal use across socioeconomic groups. The reason for the lower health care use amongst the poor may be due to several barriers including the cost of care, cost of transportation and lower awareness on health promoting behavior [ 50 ]. User fees were introduced in Ghana in 1985 as a cost-sharing mechanism at all public health facilities. To ensure access to health care services for the poor and vulnerable the government introduced fee exemptions. Then again in 2003, a new policy for exempting deliveries from user fees in the four most deprived regions of the country, namely Central, Northern, Upper East and Upper West regions were introduced. To further bridge the inequality a key recommendation of the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy [ 51 ] was to allocate 40% of the non-wage recurrent budget to the deprived regions. However, experience to date indicates that Ghana has not been able to implement an efficient exemption mechanism or commit to the 40% budgetary allocation to achieve the principal purpose. In addition to these financial hurdles, poorer people are often also located further from health centers. The ratios of population to nurses and doctors are the highest the poorest regions of Ghana. For example the ratio of population to doctors in the northern region is 1:81338 compared to the national average of 1:17733. Trends show that since 1995 the Northern region has had the lowest average number of outpatient visits per capita in the country [ 52 ]. Also partly related to the use of health services is the contribution of the number of under-fives in the household. Poor women are more likely to have more children and these, in turn, are therefore more likely to be malnourished. The higher parity among poorer women may be related to difficult access to or knowledge on family planning services. The much lower use and knowledge of modern contraception among poor women is documented in the Ghana DHS 2003 final report [ 17 ].

The negative contribution of age comes from the combined facts that older children are more likely to be malnourished and at the same time more prevalent in the richer wealth quintiles. The latter could be related to higher child and infant mortality rates amongst poorer households that cause the proportion of older children to be lower among poor households as compared to richer households.

Combining the results from the analysis on the determinants of malnutrition and socioeconomic inequality demonstrates that variables that are associated with average malnutrition are not necessarily also related to socioeconomic inequality. Although bio-demographic variables such as a risky birth interval, size at birth, duration of breastfeeding and the sex of the child are quite strongly associated with a child's nutritional status, they do not contribute to socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. This is because of their relatively equal distribution across socioeconomic groups. Other variables such as urban/rural location, having a toilet, access to clean water and maternal occupation are very unequally distributed across socioeconomic groups, but still do not contribute to socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition because they are not significantly associated with malnutrition. A third group of variables such as regions, health care use and wealth are both very strongly related to average and socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition.

Considerations and limitations

There exist some limitations of this study. First, DHS only collects information on the recent food consumption of the youngest child under three years of age living with the mother. Restricting the sample to these children would substantially reduce the number of observations. However, the analysis was also conducted on this sub sample, using food consumption as one of the determinants of malnutrition (indices were created similar to [ 25 , 45 ]). Since the regression and decomposition results did not differ much, these are not presented in this paper (but are available from the authors upon request). Second, one has to bear in mind that, although commonly used, the construction of an asset index to capture socioeconomic status has its shortcomings and e.g. is sensitive to the assets included [ 44 ]. However, in the absence of reliable information on income or expenditure, the use of such an asset index is generally a good alternative to distinguish socioeconomic layers within a population [ 53 ]. Finally, it is important to note that this paper is showing the factors that are associated with malnutrition and socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition and the magnitude of these associations. These results are subject to the usual caveats regarding the causal interpretation of cross-sectional results. Focusing on child health avoids much of the direct feedback of income and health that is usually present in microeconomic studies. To gain some insight into the severity of endogeneity problems we also did the analysis excluding possible endogenous variables such as birth interval, breastfeeding, the number of children in the household and use of health care services. Again, wealth and regional characteristics were contributing most to socioeconomic inequality, followed by maternal education. To avoid endogeneity of health care use, it would be better to use data on proximity/availability of care. However, no such data were available in the 2003 Ghana DHS. Another option would be to predict health care use, but we were not able to find strong predictors for health care.

Conclusion and policy implications

The regression results show that malnutrition is associated with a broad range of factors. However in Ghana it often falls through the cracks since it has no institutional home. Tackling malnutrition therefore calls for a shared vision and should be viewed and addressed in a broader context [ 54 ]. Therefore special attention needs to be given to policies aimed at reducing malnutrition based on the magnitude and nature of determinants of malnutrition, such as poverty, education, health care and family planning services and regional characteristics. Currently in Ghana, various interventions are being implemented to reduce both PEM and micro nutrient deficiencies. These include the Infant and Young Child Feeding Strategy (IYCF) and Community Based Nutrition and Food Security project among others. Notwithstanding the positive effects of these programs, they address only the symptoms of malnutrition and therefore are most likely not sufficient to have a sustained impact in the long term as they do not deal with a lot of the root causes of malnutrition.

The results also suggest that factors strongly associated with average malnutrition are not necessarily also contributing to socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. The distinction between these groups of variables can be quite important, as it suggests that policies trying to reduce average malnutrition rates can be different from those aiming at lowering socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition. If equity goals are to be achieved, health policies in Ghana should further be directed at strategies/interventions to reduce poverty and to improve the use of health care and family planning services among the poorer population groups. Furthermore, regional disparities should further be tackled to narrow the gap in malnutrition between the poor and the rich. A starting point could be for policy makers to include under-five malnutrition differentials to set criteria to guide resource allocation to regions. Moreover, the strong regional contributions to socioeconomic inequality, even after controlling for other factors such as household wealth and education, bring forward the issue of geographical targeting. Further targeting public programs towards the central and northern regions would substantially reduce socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition and is administratively easier than targeting the poor. The latter argument is relevant for Ghana, where pro-poor policies (redistribution schemes and exemption policies) are not having the aimed effect because of problems in identifying the poor [ 55 , 56 ]. Geographic targeting reduces leakage of program benefits to the non-needy compared to untargeted programs, although under coverage of the truly needy can increase. "Fine-tuning" the targeting by basing it on smaller geographic units increases efficiency, but in some circumstances may be costly and politically unacceptable [ 57 ].

With respect to Ghana, regional averages should be interpreted with caution as there is large heterogeneity between districts in each region and indeed among socio-economic groups within districts. In this case, polices aimed at reducing child malnutrition based on regional averages may lead to under coverage of those in need. [ 58 ] exposes some important limitations of geographic targeting if used to place poverty-alleviation or nutrition interventions within cities. Using data from Abidjan (Cote d'Ivoire) and Accra (Ghana), they found significant clustering in housing conditions; however they did not find any sign of geographic clustering of nutritional status in either city. This implies that geographic targeting of nutrition interventions in these and similar cities has important limitations. Geographic targeting would probably lead to a significant under coverage of the truly needy and, unless accompanied by additional targeting mechanisms, would also result in significant leakage to non-needy populations. Nonetheless, there is a need for additional research to further decompose regional malnutrition inequalities to generate valuable information for policy making decisions. The Ghana Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy for 2006 – 2009 [ 59 ] states that one of the strategies to be implemented is developing and implementing high impact yielding strategies for malnutrition. This would mean targeting areas at the greatest risks of malnutrition, replicate best practices and expand coverage. This then should result in decreasing malnutrition rates among children particularly in rural areas and northern Ghana.

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF): The state of the world's children. 2000, [ http://www.unicef.org/sowc00/ ]

Google Scholar

United Nations (UN): Sub-Saharan Africa – the human costs of the 2015 'business-as-usual' scenario. [ http://hdr.undp.org/docs/events/Berlin/Background_paper.pdf ]

Smith LC, Obeid AEE, Jensen HH: The geography and causes of food insecurity in developing countries. Agricultural Economics. 2000, 22: 199-215. 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2000.tb00018.x.

Article Google Scholar

Smith LC, Haddad L: Explaining child malnutrition in developing countries: a cross country analysis. 2000, International Food Policy Research Institute, Food Consumption and Nutrition Division discussion paper nr. 60

Vella V, Tomkins A, Borghesi A, Migliori GB, Adriko BC, Crevatin E: Determinants of child nutrition in north-west Uganda. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1992, 70: 637-647.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Habicht JP: Epidemiological evidence for a potentiating effect of malnutrition on child mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 1993, 83: 1130-1133.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schroeder DG, Brown KH: Nutritional status as a predictor of child survival: summarizing the association and quantifying its global impact. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1994, 72: 569-579.

Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA: The effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1995, 73: 443-448.

Mendez MA, Adair LS: Severity and timing of stunting in the first two years of life affect performance on cognitive tests in late childhood. Journal of Nutrition. 1999, 129: 1555-1562.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Delpeuch F, Traissac P, Martin-Pre Y, Massamba JP, Maire B: Economic crisis and malnutrition: socioeconomic determinants of anthropometric status of preschool children and their mothers in an African urban area. Public Health Nutrition. 2000, 3: 39-47.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Martorell R, Rivera J, Kaplowitz H, Pollitt E: Long-term consequences of growth retardation during early childhood. Human growth: basic and clinical aspects. Edited by: Hernandez M, Argente J. 1992, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers, 143-149.

Lavy V, Strauss J, Thomas D, de Vreyer P: Quality of health care, survival and health outcomes in Ghana. Journal of Health Economics. 1996, 15: 333-357. 10.1016/0167-6296(95)00021-6.

de Onis M, Frongillo EA, Blossner M: Is malnutrition declining? An analysis of changes in levels of child malnutrition since 1980. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000, 78: 1222-1233.

United Nations (UN): UN Millennium Project. About the Goals: What they are. 2006, [ http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/goals/ ]

United Nations Development Program (UNDP): Human Development Report. 2005

Nolen LB, Braveman P, Dachs JN, Delgado I, Gakidou E, Moser K, Rolfe L, Vega J, Zarowsky C: Strengthening health information systems to address health equity challenges. Bull World Health Organ. 2005, 83 (8): 597-603.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR), ORC Macro: . Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2003. 2004, Calverton, Maryland

ORC Macro: Trends in Demographic, Family Planning, and Health Indicators in Ghana, 1960–2003: Trend Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys Data. 2005, Calverton, Maryland, USA

Shepherd A, Gyimah-Boadi E, Gariba S, Plagerson S, Wahab Musa A: Bridging the North South divide in Ghana. World Development Report 2006, Background Papers. 2004

Ghana Health Service: Imagine Ghana free of malnutrition. Ghana. 2005

Ghana Ministry of Health: National Health Policy Draft. Ghana. 2006

Brakohiapa LA, Yartey J, Bille A, Harrison E, Quansah E, Armar MA, Kishi K, Yamamato S: Does prolonged breastfeeding adversely affect a child's nutritional status?. Lancet. 1988, 332: 416-418. 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90411-4.

Alderman H: Nutritional status in Ghana and its determinants. Social Dimensions of Adjustments in sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Working Paper nr 3. 1999, World Bank, Washington

Ruel MT, Levin CE, Armar-Klemesu D, Maxwell D, Morris S: Good care practices can mitigate the negative effects of poverty and low maternal schooling on children's nutritional status: Evidence from Accra. World Development. 1999, 27: 1993-2009. 10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00097-2.

Tharakan CT, Suchindran CM: Determinants of child malnutrition – An intervention model for Botswana. Nutritional Research. 1999, 19: 843-860. 10.1016/S0271-5317(99)00045-7.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ukuwuani FA, Suchindran CM: Implications of women's work for child nutritional status in sub-Saharan Africa: a case study of Nigeria. Social Science and Medicine. 2003, 56: 2109-2121. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00205-8.

Wagstaff A, Watanabe N: Socioeconomic inequalities in Child Malnutrition in the Developing World. World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 2434;. 2000

Thang NM, Popkin BM: In an area of economic growth, is inequity holding back reductions in child malnutrition in Vietnam?. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003, 12: 405-10.

PubMed Google Scholar

Zere E, McIntyre D: Inequities in under-five child malnutrition in South-Africa. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2003, 2:

Fotso JC, Kuate-Defo B: Measuring socioeconomic status in health research in developing countries: should we be focusing on households, communities or both?. Social Indicators Research. 2005, 72: 189-237. 10.1007/s11205-004-5579-8.

Hong R: Effect of economic inequality on chronic childhood undernutrition in Ghana. Public Health Nutrition. 2006, 10: 371-378. 10.1017/S1368980007226035.

Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E, Watanabe N: On decomposing the causes of health sector inequalities with an application to malnutrition inequalities in Vietnam. Journal of Econometrics. 2003, 112: 207-223. 10.1016/S0304-4076(02)00161-6.

World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group: WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/height-for-age, Weight-forage, Weight-for-length, Weight-for-height and Body mass index-for-age: Methods and Development. World Health Organization. 2006, Geneva

Garza C, de Onis M: Rationale for developing a new international growth reference. Food Nutr Bull. 2004, 25 (1 Suppl): S5-S14.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization (WHO): Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. WHO Technical Report Series No. 854. 1995, World Health Organization, Geneva

Pradhan M, Sahn DE, Younger SD: Decomposing world health inequality. Journal of Health Economics. 2003, 22: 271-293. 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00123-6.

World Health Organization: WHO Anthro software and macros. [ http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/ ]