Memoir vs Autobiography: Understanding the Key Differences

By: Author Valerie Forgeard

Posted on May 10, 2024

Categories Reading , Storytelling , Writing

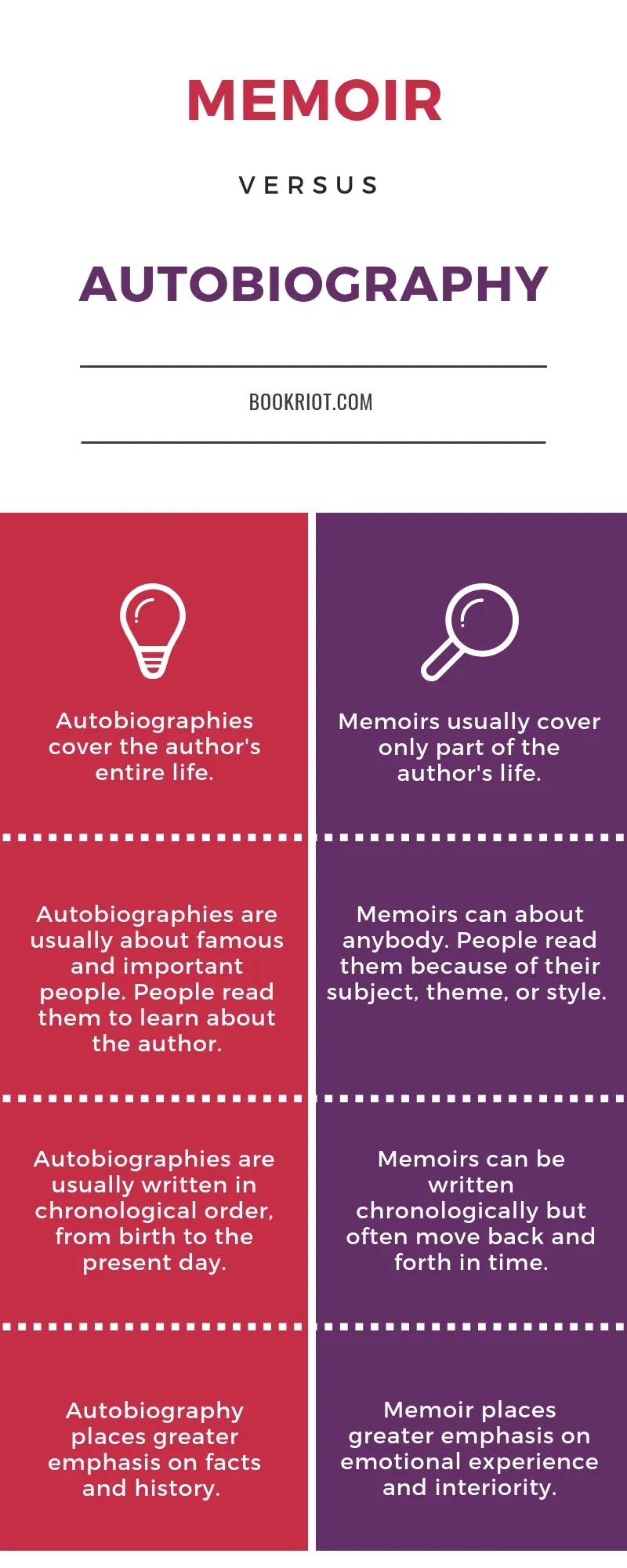

A memoir and an autobiography are both forms of personal narrative that delve into an individual’s life experiences, but they serve distinct purposes and adhere to different structures.

An autobiography is a comprehensive narration that covers an author’s entire life from birth to the present, offering a detailed chronology of events and facts. It is expected to be factually accurate and exhaustive, encapsulating a wide spectrum of life’s milestones.

In contrast, a memoir tends to be more selective and subjective. It may focus on a particular theme or a significant segment of the author’s life, emphasizing emotional truth and personal reflection. Memoir writers often aim to establish a deep connection with the reader, employing a storytelling approach that prioritizes emotional resonance over chronological exactitude.

The distinction between the two can be seen in how they approach their narratives: a memoir is akin to a snapshot of a pivotal moment or series of moments, imparting personal insights and truths, while an autobiography resembles a full-length documentary, capturing a life’s story with precision and breadth.

Defining Memoir and Autobiography

In the realm of nonfiction, memoirs and autobiographies allow authors to present their life stories, but they adhere to different conventions and serve distinct literary functions.

Core Characteristics

Memoir is a term that specifies a narrative focused on specific memories or pivotal moments from the author’s life, often presented with reflective and emotional overtones. Memoirs tend to zoom in on a particular period or theme, offering deep insights into personal experiences and their broader impacts. They are less about the comprehensive chronology and more about the subjective journey and emotional truths.

Contrast, an autobiography might be seen as the exhaustive mapping of an individual’s life. It is a chronological account, commencing with birth and following through to the present or the end of their life. Autobiographies are structured around the factual and often strive for a complete historical portrayal of one’s life, including significant milestones and achievements.

Historical Evolution

The memoir as a literary genre has evolved significantly over time, with early iterations akin to autobiographies but without their sweeping scope. Modern memoirs, however, have become more selective, seeking to engage readers through shared human conditions and powerful storytelling.

The concept of an autobiography has remained relatively stable, rooted in the comprehensive recording of a person’s life. This form has long been associated with influential figures and serves as a method for public personas to share their life stories with a degree of formal structure and attention to factual detail.

Both genres reflect an author’s perspective and presence, thus contributing valuable insights into the human condition as documented through the lenses of personal history within nonfiction writing .

Structural Differences

In examining the structural variations between memoirs and autobiographies, one will find distinct differences in the approaches to chronology and the extent of the life story they cover.

Chronology in Narrative

Memoirs often adopt a non-traditional approach to chronology , focusing on thematic connections rather than strict chronological order . The structure can be flexible, weaving in and out of different time periods as they relate to the overall theme or message the author is conveying. This may involve flashbacks or reflective passages that link past events to current reflections.

Scope and Focus

Conversely, autobiographies usually maintain a broader scope , presenting the narrative of one’s whole life from birth to the present day in a linear fashion. The structure here is more traditionally chronological, cataloging events as they occurred through time.

An autobiography aims to provide a comprehensive history rather than emphasizing a specific period or theme. It seeks to document the full spectrum of experiences and achievements of an individual’s life.

Emotional and Thematic Content

Choosing between a memoir and an autobiography often hinges on how the writer wishes to engage with the audience through emotional depth and central themes . This section will explore how each format addresses personal experiences and emotions , and how themes and messages are developed to establish a connection with the reader.

Personal Experiences and Emotion

In memoirs, authors have the latitude to deeply explore their personal experiences with a focus on emotional truth . They offer a profound emotional connection by reflecting on the feelings and insights that these experiences elicited. For instance, writing a memoir allows an author to share not just the events of their life but also the emotional journey that accompanied those events, providing a more intimate reading experience.

Themes and Messages

Contrasting with autobiographies, memoirs are often designed around a central theme or message , rather than a comprehensive life story. This focused approach allows the writer to illuminate lessons learned or insights gained, making it a powerful tool for delivering a resonating message .

The thematic bones of a memoir can vary widely, from overcoming adversity to the joy of discovery, each underscored by the emotional resonance that binds the narrative together.

The Role of the Author

In both memoirs and autobiographies, the author undeniably plays a central role not only as the narrator but also as the subject. The nuances in their storytelling and purpose set apart the impact and structure of each genre.

First-Person Perspective

Memoirs and autobiographies are crafted from a first-person perspective , giving the reader an intimate lens through which to view the author’s experiences. The writer’s perspective is the core of both narratives, revealing personal essays that frame their experiences with immediacy and presence. A memoir often hinges on this perspective to draw the reader into specific personal stories.

Author’s Intention and Reflection

The intentions and reflections present in the author’s writing can vary significantly between a memoir and an autobiography. In autobiographies, the intention often circles around documenting the historical account of their life, elucidating a factual chronology from birth to the present.

Whereas in memoirs, the writer’s reflection is more pronounced, they emphasize particular life events to share a thematic or emotional journey rather than a comprehensive life story. The personal essay format of a memoir relies heavily on an author’s reflection to convey deeper truths about human experience .

Influence and Impact on the Reader

The measure of a book’s success often lies in its capacity to influence and impact its readers on an emotional and educational level. Memoirs and autobiographies, while similar, achieve this in distinct ways.

Creating Connection

Memoirs tap into the profound depths of the writers’ experiences to forge a strong emotional connection with their readers. This genre is not just about the events themselves but also about the emotions and reflections that accompany them. Readers often find memoirs relatable because they focus on specific themes , allowing individuals to see aspects of their own lives mirrored in the narrative. For instance, a memoir can make a reader feel as if they are walking alongside the author through their most transformative life events .

Educational Value

Autobiographies, however, often contain a comprehensive account of the author’s life, which can be educational in scope. Readers gain insights into not only the personal journeys but also historical and cultural contexts that shaped the author’s experiences.

An autobiography can serve as a de facto masterclass on an individual’s entire life, offering readers a chronological understanding of the subject’s history and development within their professional field or influence on society.

Examining Notable Works

In examining the impact and contribution to literature , it’s important to look at specific examples of autobiographies and memoirs that have left an indelible mark on readers and the literary world.

Famous Autobiographies

Autobiographies provide an encompassing look into an individual’s life, often presenting a chronological journey from birth to the present. Nelson Mandela’s “Long Walk to Freedom” is a profound testament to his resilience and leadership in the face of apartheid in South Africa. Benjamin Franklin is another distinguished figure whose autobiography has inspired countless individuals with its portrayal of American Enlightenment ideas.

The narratives of Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X are pivotal, highlighting racial injustice in America and the power of transformation ; the former through “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” and the latter via “ The Autobiography of Malcolm X ,” as told to Alex Haley. Helen Keller’s “The Story of My Life” also serves as a beacon of courage, detailing her journey as an author and activist who overcame the challenges of being deaf and blind.

Memorable Memoirs

A memoir often focuses on specific themes or periods from the author’s life, reflecting on the emotional and personal growth of the individual. Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” shines a light on identity and racism through the lens of her early experiences. Frank McCourt’s “Angela’s Ashes” provides a haunting yet humorous account of his impoverished childhood in Ireland.

Joan Didion crafted a powerful narrative on grief in “The Year of Magical Thinking,” reflecting on the year following the death of her husband. Elie Wiesel’s memoir “Night” confronts the horrors he survived during the Holocaust, embodying a chilling testament of history. Meanwhile, David Sedaris uses wit and observation in “Me Talk Pretty One Day” to explore the idiosyncrasies of his life. The personal struggles and triumphs of Malala Yousafzai are poignantly narrated in “I Am Malala,” inspiring readers worldwide.

Ernest Hemingway and Elizabeth Gilbert utilized the memoir format to recount significant personal journeys. Hemingway’s “A Moveable Feast” delves into his years in 1920s Paris, while Gilbert’s “Eat, Pray, Love” recounts a year of exploration and self-discovery.

Andre Agassi and Roxane Gay wrote memoirs offering raw insights into their lives. Agassi’s “Open” reveals the complexities behind his illustrious tennis career, while Gay’s “Hunger” is a brave exposition of her relationship with her body and self-image.

The transformative experiences of Piper Kerman in “Orange Is the New Black” and Malala Yousafzai ‘s activism in “I Am Malala” have struck chords with readers, highlighting the potential for personal memoirs to effect change and resonate on a global scale.

Understanding these notable works enriches our appreciation for the unique lenses through which autobiographies and memoirs are written, offering a profound glimpse into the human experience.

Writing Your Own

When one sets out to pen a personal narrative , they grapple with the choice of a memoir or autobiography, each offering a unique avenue for sharing life stories. The decision shapes not only the content but also the connection with readers.

Choosing Between Memoir and Autobiography

A memoir typically zooms in on specific themes or periods in a person’s life, conveying more emotional depth and personal insights. It’s a slice of life that resonates with overarching themes common to human experiences. For example, one might focus a memoir on the trials and triumphs of their artistic career, highlighting critical moments that define their personal growth and development.

An autobiography , on the other hand, presents a more comprehensive chronology of the author’s life. It’s often factual and holistic, starting from early life and progressing through major milestones and achievements. When an author wishes to document their entire life’s journey as a historical record, an autobiography is the suitable format. This approach requires meticulous attention to detail and often involves a chronological recount of the author’s life experiences.

Tips for Aspiring Authors

Begin with a plan : Establish whether the aim is to explore a particular aspect of life (memoir) or to narrate life from start to present (autobiography). Consult credible resources like Masterclass for insights into the distinctions.

Be reflective : Regardless of the chosen format, reflection is key. Tap into personal feelings, lessons learned, and experiences that shaped who you are. This introspective approach is paramount for both memoirs and autobiographies.

Develop your voice : A unique narrative voice is crucial. Whether it’s the conversational tone of a memoir or the authoritative recount of an autobiography, the voice should be compelling and authentic.

Focus on storytelling : Narrate your experiences in a way that engages readers. Grammarly suggests that good storytelling transcends mere facts, weaving experiences into a narrative that captivates readers.

Edit meticulously : A successful personal account demands rigorous editing. A story is only as compelling as it is clear and well-written.

In distinguishing between memoirs and autobiographies , it is essential for one to recognize the scope and detail each literary form entails. An autobiography offers a comprehensive recollection of an individual’s entire life story , chronicling their birth, upbringing, achievements , and struggles . It often follows a chronological structure and demands extensive reflection and thorough documentation of events.

Memoirs, on the other hand, present a more concentrated exploration, focusing on pivotal events or periods within a person’s life. These works are typically less comprehensive but rich in emotional and introspective detail. The lens through which a memoir is written is aimed at bringing forth the writer’s personal reflection on significant experiences, revealing insights into their choices and the lessons learned.

- Autobiography : Chronicles the entirety of one’s life.

- Memoir : Highlights specific chapters of personal significance.

Writers choose between these forms based on their intent to either recount their life’s full tapestry or illuminate select threads that hold unique personal meaning. Each format serves its purpose, allowing readers to delve into the narrative – be it the detailed map of a full life’s journey or the magnified examination of its critical junctures.

The Differences between Memoir, Autobiography, and Biography - article

Creative nonfiction: memoir vs. autobiography vs. biography.

Writing any type of nonfiction story can be a daunting task. As the author, you have the responsibility to tell a true story and share the facts as accurately as you can—while also making the experience enjoyable for the reader.

There are three primary formats to tell a creative nonfiction story: memoir, autobiography, and biography. Each has its own distinct characteristics, so it’s important to understand the differences between them to ensure you’re writing within the correct scope.

A memoir is a collection of personal memories related to specific moments or experiences in the author’s life. Told from the perspective of the author, memoirs are written in first person point of view.

The defining characteristic that sets memoirs apart from autobiographies and biographies is its scope. While the other genres focus on the entire timeline of a person’s life, memoirs structure themselves on one aspect, such as addiction, parenting, adolescence, disease, faith, etc.

They may tell stories from various moments in the author’s life, but they should read like a cohesive story—not just a re-telling of facts.

“You don’t want a voice that simply relates facts to the reader. You want a voice that shows the reader what’s going on and puts him or her in the room with the people you’re writing about.” – Kevan Lyon in Writing a Memoir

Unlike autobiographies and biographies, memoirs focus more on the author’s relationship to and feelings about his or her own memories. Memoirs tend to read more like a fiction novel than a factual account, and should include things like dialogue , setting, character descriptions, and more.

Authors looking to write a memoir can glean insight from both fiction and nonfiction genres. Although memoirs tell a true story, they focus on telling an engaging narrative, just like a novel. This gives memoir authors a little more flexibility to improve upon the story slightly for narrative effect.

However, you should represent dialogue and scenarios as accurately as you can, especially if you’re worried about libel and defamation lawsuits .

Examples of popular memoirs include Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert and The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls.

Key traits of a memoir:

- Written in 1 st person POV from the perspective of the author - Less formal compared to autobiographies and biographies - Narrow in scope or timeline - Focused more on feelings and memories than facts - More flexibility to change the story for effect

Autobiography

Like a memoir, an autobiography is the author’s retelling of his or her life and told in first person point of view, making the author the main character of the story.

Autobiographies are also narrative nonfiction, so the stories are true but also include storytelling elements such as a protagonist (the author), a central conflict, and a cast of intriguing characters.

Unlike memoirs, autobiographies focus more on facts than emotions. Because of this, a collaborator often joins the project to help the author tell the most factual, objective story possible.

While a memoir is limited in scope, an autobiography details the author’s entire life up to the present. An autobiography often begins when the author is young and includes detailed chronology, events, places, reactions, movements and other relevant happenings throughout the author’s life.

“In many people’s memoir, they do start when they’re younger, but it isn’t an, ‘I got a dog, then we got a fish, and then I learned to tie my shoes’…it isn’t that kind of detail.” – Linda Joy Meyers in Memoir vs. Autobiography

The chronology of an autobiography is organized but not necessarily in date order. For instance, the author may start from current time and employ flashbacks or he/she may organize events thematically.

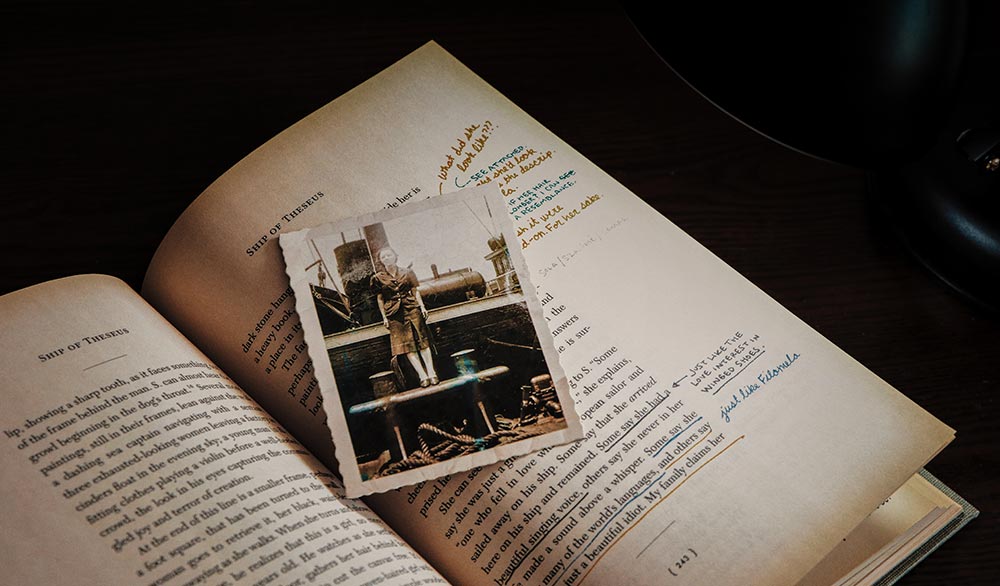

Autobiographers use many sources of information to develop the story such as letters, photographs, and other personal memorabilia. However, like a memoir, the author’s personal memory is the primary resource. Any other sources simply enrich the story and relay accurate and engaging experiences.

A good autobiography includes specific details that only the author knows and provides context by connecting those details to larger issues, themes, or events. This allows the reader to relate more personally to the author’s experience.

Examples of popular autobiographies include The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou.

Key traits of an autobiography:

- Written in 1 st person POV from the perspective of the author, occasionally with the help of a collaborator - More formal and objective than memoirs, but more subjective than biographies - Broad in scope or timeline, often covering the author’s entire life up to the present - Focused more on facts than emotions - Requires more extensive fact-checking and research than memoirs, but less than biographies

A biography is the story of events and circumstances of a person’s life, written by someone other than that person. Usually, people write biographies about a historical or public figure . They can be written with or without the subject’s authorization.

Since the author is telling the account of someone else, biographies are always in third person point of view and carry a more formal and objective tone than both memoirs and autobiographies.

Like an autobiography, biographies cover the entire scope of the subject’s life, so it should include details about his or her birthplace, educational background, work history, relationships, death and more.

Good biographers will research and study a person’s life to collect facts and present the most historically accurate, multi-faceted picture of an individual’s experiences as possible. A biography should include intricate details—so in-depth research is necessary to ensure accuracy.

“If you’re dealing principally with historical figures who are long dead, there are very few legal problems…if you’re dealing with a more sensitive issue…then the lawyers will be crawling all over the story.” – David Margolick in Legal Issues with Biographies

However, biographies are still considered creative nonfiction, so the author has the ability to analyze and interpret events in the subject’s life, looking for meaning in their actions, uncovering mistakes, solving mysteries, connecting details, and highlighting the significance of the person's accomplishments or life activities.

Authors often organize events in chronological order, but can sometimes organize by themes or specific accomplishments or topics, depending on their book’s key idea.

Examples of popular biographies include Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson and The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot.

Key traits of a biography:

- Written about another person, often a celebrity or public figure, and told in 3 rd person point of view - More formal and objective than both memoirs and autobiographies - Broad in scope or timeline, often covering the subject’s entire life up to the present - Focused solely on facts - Requires meticulous research and fact-checking to ensure accuracy

- Biographies and Memoirs

- Zeinab el Ghatit</a> and <span class="who-likes">7 others</span> like this" data-format="<span class="count"><span class="icon"></span>{count}</span>" data-configuration="Format=%3Cspan%20class%3D%22count%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22icon%22%3E%3C%2Fspan%3E%7Bcount%7D%3C%2Fspan%3E&IncludeTip=true&LikeTypeId=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000" >

Met you this morning briefly and just bought your book on Amazon. Congratulations.

Very helpful. I think I am heading down the path of a memoir.

Thank you explaining the differences between the three writing styles!

Very useful article. Well done. Please can we have more. Doctor's Orders !!!

My first book, "Tales of a Meandering Medic" is definitely a Memoir.

© Copyright 2018 Author Learning Center. All Rights Reserved

If you’ve thought about putting your life to the page, you may have wondered how to write a memoir. We start the road to writing a memoir when we realize that a story in our lives demands to be told. As Maya Angelou once wrote, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

How to write a memoir? At first glance, it looks easy enough—easier, in any case, than writing fiction. After all, there is no need to make up a story or characters, and the protagonist is none other than you.

Still, memoir writing carries its own unique challenges, as well as unique possibilities that only come from telling your own true story. Let’s dive into how to write a memoir by looking closely at the craft of memoir writing, starting with a key question: exactly what is a memoir?

How to Write a Memoir: Contents

What is a Memoir?

- Memoir vs Autobiography

Memoir Examples

Short memoir examples.

- How to Write a Memoir: A Step-by-Step Guide

A memoir is a branch of creative nonfiction , a genre defined by the writer Lee Gutkind as “true stories, well told.” The etymology of the word “memoir,” which comes to us from the French, tells us of the human urge to put experience to paper, to remember. Indeed, a memoir is “ something written to be kept in mind .”

A memoir is defined by Lee Gutkind as “true stories, well told.”

For a piece of writing to be called a memoir, it has to be:

- Nonfictional

- Based on the raw material of your life and your memories

- Written from your personal perspective

At this point, memoirs are beginning to sound an awful lot like autobiographies. However, a quick comparison of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love , and The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin , for example, tells us that memoirs and autobiographies could not be more distinct.

Next, let’s look at the characteristics of a memoir and what sets memoirs and autobiographies apart. Discussing memoir vs. autobiography will not only reveal crucial insights into the process of writing a memoir, but also help us to refine our answer to the question, “What is a memoir?”

Memoir vs. Autobiography

While both use personal life as writing material, there are five key differences between memoir and autobiography:

1. Structure

Since autobiographies tell the comprehensive story of one’s life, they are more or less chronological. writing a memoir, however, involves carefully curating a list of personal experiences to serve a larger idea or story, such as grief, coming-of-age, and self-discovery. As such, memoirs do not have to unfold in chronological order.

While autobiographies attempt to provide a comprehensive account, memoirs focus only on specific periods in the writer’s life. The difference between autobiographies and memoirs can be likened to that between a CV and a one-page resume, which includes only select experiences.

The difference between autobiographies and memoirs can be likened to that between a CV and a one-page resume, which includes only select experiences.

Autobiographies prioritize events; memoirs prioritize the writer’s personal experience of those events. Experience includes not just the event you might have undergone, but also your feelings, thoughts, and reflections. Memoir’s insistence on experience allows the writer to go beyond the expectations of formal writing. This means that memoirists can also use fiction-writing techniques , such as scene-setting and dialogue , to capture their stories with flair.

4. Philosophy

Another key difference between the two genres stems from the autobiography’s emphasis on facts and the memoir’s reliance on memory. Due to memory’s unreliability, memoirs ask the reader to focus less on facts and more on emotional truth. In addition, memoir writers often work the fallibility of memory into the narrative itself by directly questioning the accuracy of their own memories.

Memoirs ask the reader to focus less on facts and more on emotional truth.

5. Audience

While readers pick up autobiographies to learn about prominent individuals, they read memoirs to experience a story built around specific themes . Memoirs, as such, tend to be more relatable, personal, and intimate. Really, what this means is that memoirs can be written by anybody!

Ready to be inspired yet? Let’s now turn to some memoir examples that have received widespread recognition and captured our imaginations!

If you’re looking to lose yourself in a book, the following memoir examples are great places to begin:

- The Year of Magical Thinking , which chronicles Joan Didion’s year of mourning her husband’s death, is certainly one of the most powerful books on grief. Written in two short months, Didion’s prose is urgent yet lucid, compelling from the first page to the last. A few years later, the writer would publish Blue Nights , another devastating account of grief, only this time she would be mourning her daughter.

- Patti Smith’s Just Kids is a classic coming-of-age memoir that follows the author’s move to New York and her romance and friendship with the artist Robert Maplethorpe. In its pages, Smith captures the energy of downtown New York in the late sixties and seventies effortlessly.

- When Breath Becomes Air begins when Paul Kalanithi, a young neurosurgeon, is diagnosed with terminal cancer. Exquisite and poignant, this memoir grapples with some of the most difficult human experiences, including fatherhood, mortality, and the search for meaning.

- A memoir of relationship abuse, Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House is candid and innovative in form. Machado writes about thorny and turbulent subjects with clarity, even wit. While intensely personal, In the Dream House is also one of most insightful pieces of cultural criticism.

- Twenty-five years after leaving for Canada, Michael Ondaatje returns to his native Sri Lanka to sort out his family’s past. The result is Running in the Family , the writer’s dazzling attempt to reconstruct fragments of experiences and family legends into a portrait of his parents’ and grandparents’ lives. (Importantly, Running in the Family was sold to readers as a fictional memoir; its explicit acknowledgement of fictionalization prevented it from encountering the kind of backlash that James Frey would receive for fabricating key facts in A Million Little Pieces , which he had sold as a memoir . )

- Of the many memoirs published in recent years, Tara Westover’s Educated is perhaps one of the most internationally-recognized. A story about the struggle for self-determination, Educated recounts the writer’s childhood in a survivalist family and her subsequent attempts to make a life for herself. All in all, powerful, thought-provoking, and near impossible to put down.

While book-length memoirs are engaging reads, the prospect of writing a whole book can be intimidating. Fortunately, there are plenty of short, essay-length memoir examples that are just as compelling.

While memoirists often write book-length works, you might also consider writing a memoir that’s essay-length. Here are some short memoir examples that tell complete, lived stories, in far fewer words:

- “ The Book of My Life ” offers a portrait of a professor that the writer, Aleksandar Hemon, once had as a child in communist Sarajevo. This memoir was collected into Hemon’s The Book of My Lives , a collection of essays about the writer’s personal history in wartime Yugoslavia and subsequent move to the US.

- “The first time I cheated on my husband, my mother had been dead for exactly one week.” So begins Cheryl Strayed’s “ The Love of My Life ,” an essay that the writer eventually expanded into the best-selling memoir, Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail .

- In “ What We Hunger For ,” Roxane Gay weaves personal experience and a discussion of The Hunger Games into a powerful meditation on strength, trauma, and hope. “What We Hunger For” can also be found in Gay’s essay collection, Bad Feminist .

- A humorous memoir structured around David Sedaris and his family’s memories of pets, “ The Youth in Asia ” is ultimately a story about grief, mortality and loss. This essay is excerpted from the memoir Me Talk Pretty One Day , and a recorded version can be found here .

So far, we’ve 1) answered the question “What is a memoir?” 2) discussed differences between memoirs vs. autobiographies, 3) taken a closer look at book- and essay-length memoir examples. Next, we’ll turn the question of how to write a memoir.

How to Write a Memoir: A-Step-by-Step Guide

1. how to write a memoir: generate memoir ideas.

how to start a memoir? As with anything, starting is the hardest. If you’ve yet to decide what to write about, check out the “ I Remember ” writing prompt. Inspired by Joe Brainard’s memoir I Remember , this prompt is a great way to generate a list of memories. From there, choose one memory that feels the most emotionally charged and begin writing your memoir. It’s that simple! If you’re in need of more prompts, our Facebook group is also a great resource.

2. How to Write a Memoir: Begin drafting

My most effective advice is to resist the urge to start from “the beginning.” Instead, begin with the event that you can’t stop thinking about, or with the detail that, for some reason, just sticks. The key to drafting is gaining momentum . Beginning with an emotionally charged event or detail gives us the drive we need to start writing.

3. How to Write a Memoir: Aim for a “ shitty first draft ”

Now that you have momentum, maintain it. Attempting to perfect your language as you draft makes it difficult to maintain our impulses to write. It can also create self-doubt and writers’ block. Remember that most, if not all, writers, no matter how famous, write shitty first drafts.

Attempting to perfect your language as you draft makes it difficult to maintain our impulses to write.

4. How to Write a Memoir: Set your draft aside

Once you have a first draft, set it aside and fight the urge to read it for at least a week. Stephen King recommends sticking first drafts in your drawer for at least six weeks. This period allows writers to develop the critical distance we need to revise and edit the draft that we’ve worked so hard to write.

5. How to Write a Memoir: Reread your draft

While reading your draft, note what works and what doesn’t, then make a revision plan. While rereading, ask yourself:

- What’s underdeveloped, and what’s superfluous.

- Does the structure work?

- What story are you telling?

6. How to Write a Memoir: Revise your memoir and repeat steps 4 & 5 until satisfied

Every piece of good writing is the product of a series of rigorous revisions. Depending on what kind of writer you are and how you define a draft,” you may need three, seven, or perhaps even ten drafts. There’s no “magic number” of drafts to aim for, so trust your intuition. Many writers say that a story is never, truly done; there only comes a point when they’re finished with it. If you find yourself stuck in the revision process, get a fresh pair of eyes to look at your writing.

7. How to Write a Memoir: Edit, edit, edit!

Once you’re satisfied with the story, begin to edit the finer things (e.g. language, metaphor , and details). Clean up your word choice and omit needless words , and check to make sure you haven’t made any of these common writing mistakes . Be sure to also know the difference between revising and editing —you’ll be doing both. Then, once your memoir is ready, send it out !

Learn How to Write a Memoir at Writers.com

Writing a memoir for the first time can be intimidating. But, keep in mind that anyone can learn how to write a memoir. Trust the value of your own experiences: it’s not about the stories you tell, but how you tell them. Most importantly, don’t give up!

Anyone can learn how to write a memoir.

If you’re looking for additional feedback, as well as additional instruction on how to write a memoir, check out our schedule of nonfiction classes . Now, get started writing your memoir!

29 Comments

Thank you for this website. It’s very engaging. I have been writing a memoir for over three years, somewhat haphazardly, based on the first half of my life and its encounters with ignorance (religious restrictions, alcohol, and inability to reach out for help). Three cities were involved: Boston as a youngster growing up and going to college, then Washington DC and Chicago North Shore as a married woman with four children. I am satisfied with some chapters and not with others. Editing exposes repetition and hopefully discards boring excess. Reaching for something better is always worth the struggle. I am 90, continue to be a recital pianist, a portrait painter, and a writer. Hubby has been dead for nine years. Together we lept a few of life’s chasms and I still miss him. But so far, my occupations keep my brain working fairly well, especially since I don’t smoke or drink (for the past 50 years).

Hi Mary Ellen,

It sounds like a fantastic life for a memoir! Thank you for sharing, and best of luck finishing your book. Let us know when it’s published!

Best, The writers.com Team

Hello Mary Ellen,

I am contacting you because your last name (Lavelle) is my middle name!

Being interested in genealogy I have learned that this was my great grandfathers wife’s name (Mary Lavelle), and that her family emigrated here about 1850 from County Mayo, Ireland. That is also where my fathers family came from.

Is your family background similar?

Hope to hear back from you.

Richard Lavelle Bourke

Hi Mary Ellen: Have you finished your memoir yet? I just came across your post and am seriously impressed that you are still writing. I discovered it again at age 77 and don’t know what I would do with myself if I couldn’t write. All the best to you!! Sharon [email protected]

I am up to my eyeballs with a research project and report for a non-profit. And some paid research for an international organization. But as today is my 90th birthday, it is time to retire and write a memoir.

So I would like to join a list to keep track of future courses related to memoir / creative non-fiction writing.

Hi Frederick,

Happy birthday! And happy retirement as well. I’ve added your name and email to our reminder list for memoir courses–when we post one on our calendar, we’ll send you an email.

We’ll be posting more memoir courses in the near future, likely for the months of January and February 2022. We hope to see you in one!

Very interesting and informative, I am writing memoirs from my long often adventurous and well travelled life, have had one very short story published. Your advice on several topics will be extremely helpful. I write under my schoolboy nickname Barnaby Rudge.

[…] How to Write a Memoir: Examples and a Step-by-Step Guide […]

I am writing my memoir from my memory when I was 5 years old and now having left my birthplace I left after graduation as a doctor I moved to UK where I have been living. In between I have spent 1 year in Canada during my training year as paediatrician. I also spent nearly 2 years with British Army in the hospital as paediatrician in Germany. I moved back to UK to work as specialist paediatrician in a very busy general hospital outside London for the next 22 years. Then I retired from NHS in 2012. I worked another 5 years in Canada until 2018. I am fully retired now

I have the whole convoluted story of my loss and horrid aftermath in my head (and heart) but have no clue WHERE, in my story to begin. In the middle of the tragedy? What led up to it? Where my life is now, post-loss, and then write back and forth? Any suggestions?

My friend Laura who referred me to this site said “Start”! I say to you “Start”!

Hi Dee, that has been a challenge for me.i dont know where to start?

What was the most painful? Embarrassing? Delicious? Unexpected? Who helped you? Who hurt you? Pick one story and let that lead you to others.

I really enjoyed this writing about memoir. I ve just finished my own about my journey out of my city then out of my country to Egypt to study, Never Say Can’t, God Can Do It. Infact memoir writing helps to live the life you are writing about again and to appreciate good people you came across during the journey. Many thanks for sharing what memoir is about.

I am a survivor of gun violence, having witnessed my adult son being shot 13 times by police in 2014. I have struggled with writing my memoir because I have a grandson who was 18-months old at the time of the tragedy and was also present, as was his biological mother and other family members. We all struggle with PTSD because of this atrocity. My grandson’s biological mother was instrumental in what happened and I am struggling to write the story in such a way as to not cast blame – thus my dilemma in writing the memoir. My grandson was later adopted by a local family in an open adoption and is still a big part of my life. I have considered just writing it and waiting until my grandson is old enough to understand all the family dynamics that were involved. Any advice on how I might handle this challenge in writing would be much appreciated.

I decided to use a ghost writer, and I’m only part way in the process and it’s worth every penny!

Hi. I am 44 years old and have had a roller coaster life .. right as a young kid seeing his father struggle to financial hassles, facing legal battles at a young age and then health issues leading to a recent kidney transplant. I have been working on writing a memoir sharing my life story and titled it “A memoir of growth and gratitude” Is it a good idea to write a memoir and share my story with the world?

Thank you… this was very helpful. I’m writing about the troubling issues of my mental health, and how my life was seriously impacted by that. I am 68 years old.

[…] Writers.com: How to Write a Memoir […]

[…] Writers.com: “How to Write a Memoir” […]

I am so grateful that I found this site! I am inspired and encouraged to start my memoir because of the site’s content and the brave people that have posted in the comments.

Finding this site is going into my gratitude journey 🙂

We’re grateful you found us too, Nichol! 🙂

Firstly, I would like to thank you for all the info pertaining to memoirs. I believe am on the right track, am at the editing stage and really have to use an extra pair of eyes. I’m more motivated now to push it out and complete it. Thanks for the tips it was very helpful, I have a little more confidence it seeing the completion.

Well, I’m super excited to begin my memoir. It’s hard trying to rely on memories alone, but I’m going to give it a shot!

Thanks to everyone who posted comments, all of which have inspired me to get on it.

Best of luck to everyone! Jody V.

I was thrilled to find this material on How to Write A Memoir. When I briefly told someone about some of my past experiences and how I came to the United States in the company of my younger brother in a program with a curious name, I was encouraged by that person and others to write my life history.

Based on the name of that curious program through which our parents sent us to the United States so we could leave the place of our birth, and be away from potentially difficult situations in our country.

As I began to write my history I took as much time as possible to describe all the different steps that were taken. At this time – I have been working on this project for 5 years and am still moving ahead. The information I received through your material has further encouraged me to move along. I am very pleased to have found this important material. Thank you!

Wow! This is such an informative post packed with tangible guidance. I poured my heart into a book. I’ve been a professional creative for years to include as a writer, mainly in the ad game and content. No editor. I wasn’t trying to make it as an author. Looking back, I think it’s all the stuff I needed to say. Therapy. Which does not, in and of itself, make for a coherent book. The level of writing garnering praise, but the book itself was a hot mess. So, this is helpful. I really put myself out there, which I’ve done in many areas, but the crickets response really got to me this time. I bought “Educated” as you recommended. Do you have any blog posts on memoirs that have something to say to the world, finding that “something” to say? It feels like that’s theme, but perhaps something more granular. Thanks for this fantastic post. If I had the moola, I would sign up for a class. Your time is and effort is appreciated. Typos likely on comments! LOL

thanks. God bless

I am a member of the “Reprobates”, a group of seven retired Royal Air Force pilots and navigators which has stayed in intermittent touch since we first met in Germany in 1969. Four of the group (all of whom are in their late seventies or early eighties) play golf together quite frequently, and we all gather for reunions once or twice a year. About a year ago, one of the Reprobates suggested posterity might be glad to hear the stories told at these gatherings, and there have since been two professionally conducted recording sessions, one in London, and one in Tarifa, Spain. The instigator of these recordings forwarded your website to his fellow Reprobates by way of encouragement to put pen to paper. And, I, for one, have found it inspiring. It’s high time I made a start on my Memoirs, thank you.

Thank you for sharing this, Tim! Happy writing!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Memoir vs. Autobiography: What’s the Difference?

They say everyone has a story to tell, and I absolutely believe that. But some folks have a story to tell about their own lives. They’ve experienced things and learned lessons that are worth sharing with other people.

That’s pretty freaking cool.

When you want to tell a personal narrative, you have a few options: a blog, a YouTube channel , even a diary. But if you want to turn it into a book, you have two options to consider:

A memoir or an autobiography.

While these two genres might seem similar, there are quite a number of meaningful differences you must know if you want to be successful in either—or if you just want to figure out what you’re going to write.

We’ll cover all that and more in this article. “And more” includes a history of these genres, tips for each, how to choose between memoir and autobiography writing, and pulling everything together.

You have that story to tell, so let’s figure out how to do it.

Defining Your Life Story: Memoirs and Autobiographies

Understanding the distinction between a memoir and an autobiography is a must for any writer venturing into personal narrative writing.

While both genres share the common element of being based on the author's life experiences, the scope and focus of each are quite different.

Memoirs are a form of creative nonfiction where the writer shares specific experiences or periods from their life. These works are less about the chronology of the author's life and more about personal reflections, emotions, and insights.

Memoirs often include a focus on specific themes or events, allowing the author to delve deeply into their experiences with a reflective and often emotional lens, and are written more like a fictional story than nonfiction.

Autobiographies, on the other hand, provide a more comprehensive view of the author's life. They typically follow a chronological format, documenting the author's life from early childhood to the present.

Autobiographies are characterized by their detailed recounting of life events to encompass personal, professional, and sometimes public aspects of the author’s journey. The autobiography format emphasizes factual storytelling.

Memoir readers aren’t looking for a play-by-play of your life. They’re after the deeper meaning and themes behind your experiences and are more okay with stylistic choices and some interpretation of events.

Folks reading autobiographies are all about knowing what you did and why.

The History of Writing About A Person’s Life

While they’re both staples in modern literature, these genres have roots deeply embedded in history.

Which means as people, we like talking about ourselves.

That’s not a bad thing, don’t get me wrong; we all lead extraordinary, unique lives and have important things to share. And share we have.

Understanding how memoirs and autobiographies have been used historically can help us understand their current forms, too.

Memoirs have transformed quite a bit over time. Originating from the ancient practice of documenting noteworthy events (with that grandiose, fictional spin), they evolved during the Renaissance as a way for individuals to share their experiences and perspectives, often focusing on public life.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, memoirs became more personal, reflecting individual experiences and internal landscapes. This evolution paved the way for the modern memoir, which often blurs the lines between factual recounting and creative storytelling. Honestly, this works best for readers seeking emotional truth and personal growth.

Autobiographies have a lineage that can be traced back to religious and political leaders documenting their lives as a record of moral and ethical standards. You know, bragging about how good they are.

In the 18th century, with the rise of literacy and individualism, autobiographies became a tool for self-expression and identity exploration. This genre gained momentum in the 20th century, with notable figures from various fields chronicling their journeys, making it a popular way for exploring the complexities of human experience.

Both styles of work have been instrumental in our understanding of the past, too. Even memoirs, with their emphasis on storytelling, give us a glimpse into the lives of individuals and societies as a whole.

Writing a Memoir: Tips and Techniques

Diving into memoir writing can be equal parts thrilling and terrifying. It's not just about recounting events; it's about turning your experiences into a story that vibes with readers.

Here are some tips and techniques to guide you:

- Find your focus - Unlike autobiographies, memoirs don't require you to detail your entire life. Pinpoint a specific theme, event, or period that holds significant meaning. This focus will be the heart of your memoir.

- Embrace emotional honesty - Memoirs thrive on emotional depth. Be honest about your feelings and experiences. This authenticity is what will connect with your readers.

- Show, don't just tell - Universally solid writing advice. Use descriptive language and sensory details to bring your story to life. Paint pictures with your words to immerse the reader in your world. Need some practice? Check out these worksheets .

- Incorporate reflective elements - A memoir is more than a series of events. It's an introspective journey. Reflect on your experiences, what you learned, and how they shaped you. This is what your readers are here for.

- Consider a non-linear structure - While some memoirs follow a chronological order, feel free to experiment with the structure. A non-linear approach can add intrigue and highlight how past events influence the present. Make sure to get lots of beta reader feedback to make sure your story still makes sense.

- Get personal, but stay relatable - While your memoir is deeply personal, aim to connect your experiences to universal themes. This relatability makes your story more impactful. Here’s a complete guide for writing themes .

- Revise with care - Memoirs often blend fact and narrative flair. In your revisions, balance creativity with accuracy. Remember, the essence of your truth is what matters most, so don’t let it get lost in your fictionalization.

Memoir writing is not just about telling your story; it's about sharing your perspective on life, with all its complexities and nuances. Each memoir is a unique window into a life, offering insights and reflections that no other story can.

My pal Abi has a great guide to writing memoirs you should bookmark if this is something you’re serious about.

Crafting an Autobiography: Structure and Elements

Writing an autobiography involves a different set of considerations compared to memoirs. It's about presenting the entirety of your life's journey with clarity and structure.

Here are key elements and structural ideas to consider:

- Outline the chronology - Autobiographies typically follow a chronological order, leading your reader through your life's journey. Map out the key events from your early years to the present, creating a timeline that serves as your narrative backbone.

- Detail significant events - Highlight the pivotal moments in your life, both personal and professional. These events should not only tell what happened but also detail their impact and the lessons you learned from them.

- Develop a consistent theme - While covering all the cool stuff you’ve done (or things you’ve endured), maintain a consistent theme or message throughout your autobiography. This theme makes the whole story worth reading.

- Incorporate character development - Show how you evolved over time. This character arc is crucial in autobiographies because it shows how experiences shaped your personality, beliefs, and decisions.

- Be factual, yet engaging - Autobiographies require factual accuracy, but that doesn't mean they should be dry. Use engaging storytelling techniques to bring your experiences to life, making your narrative both informative and captivating. Here’s an article to help you focus on your prose.

- Include supporting characters - Your life's story is also about the people who influenced you. Include these characters, describing their roles and the dynamics in your relationships with them. An autobiography is still a story, and supporting characters make stories great.

- Reflect on your journey - Offer reflections on your experiences, providing insights into how they influenced your current perspective. This reflective angle adds depth to the factual recounting of events and should be directly tied to your themes.

- Edit for coherence and clarity - Ensure that your autobiography is not just a collection of events but a cohesive tale. In editing , focus on clarity, coherence, and the overall flow of your story.

Crafting an autobiography is an opportunity to not only share your life story but also to reflect on the journey and its broader implications. It's a chance to offer a detailed, introspective look at the milestones that have defined you.

Which, admittedly, sounds intimidating, but putting in the effort can result in a book that changes both your life and a reader’s.

Choosing Your Approach to Creative Nonfiction

When it comes to sharing your life story, deciding between a memoir and an autobiography isn’t always an easy decision. This choice influences not only the structure and focus of your work but also how your readers will connect with your story.

Here are some considerations to help you decide:

Understand your objective - Consider what you wish to achieve with your book. Are you looking to explore a particular aspect of your life with emotional depth (memoir) or do you intend to provide a comprehensive account of your life’s journey (autobiography)?

Assess your content - Reflect on the events and experiences you want to share. A memoir suits a more focused, thematic exploration, while an autobiography is ideal for a broader, chronological recounting.

Consider your audience - Think about who you're writing for. Memoir readers choose their books because they’re interested in the theme, topic, or story rather than the person. Autobiography readers tend to make purchases based on who they’re reading about. If you don’t have some fame or following, an autobiography might be a hard sell.

Reflect on your writing style - Your natural writing style can also guide your choice. If you lean towards reflective, emotive storytelling, a memoir might be your forté. If you're more comfortable with factual, chronological narratives, consider an autobiography.

Flexibility vs. structure - Memoirs offer more creative flexibility in structure and storytelling, allowing for a more literary approach. Autobiographies, being more factual and chronological, require a structured approach to storytelling.

Personal comfort - Consider your comfort level with vulnerability and personal disclosure. Memoirs require a deeper dive into personal experiences and emotions. Autobiographies, while personal, can let you use a more observational tone.

Remember, the choice between a memoir and an autobiography is not just about the story you want to tell but about how you want to tell that story. Your decision will shape both the way you write your story and how your readers interpret it.

Best Practices for Personal Narrative Writing

Whether you choose to write a memoir or an autobiography, certain best practices can enhance your storytelling and connect more deeply with your readers.

First, stay authentic . Authenticity is the cornerstone of personal narrative writing. Your readers are seeking truth in your story, even if it's presented through a subjective lens. Be genuine in your recounting, and don't shy away from your unique voice.

You also want to engage your readers emotionally . Whether it's through humor, sorrow, inspiration, or reflection, emotional resonance makes your story memorable and impactful. One of the best ways to suck them in is to use descriptive language to create vivid scenes and characters. This immerses the reader in your world, making your experiences and memories come alive.

Remember, these are both still stories and thus have a cohesive plot. Ensure your story has a clear beginning, middle, and end . Even if you choose a non-linear structure, maintaining a coherent narrative flow is essential for keeping your readers engaged. If you need some help with story structure, you know we have your back with this guide .

Dialogue can be a powerful tool in personal narratives. It brings dynamism to the story and offers insights into characters and relationships. Don’t neglect good dialogue just because you aren’t writing fiction.

Personal narratives aren’t just about what happened; they’re about what those events mean. Include your reflections and analysis to provide depth and context to your experiences, but do it in a way that flows and feels natural. This is obviously more important in memoirs, but your autobiography needs to have reflection, too.

Finally, when writing about real people and events, consider the implications of sharing private information. Respect the privacy of others and navigate sensitive topics with care.

Personal narrative writing is a journey of exploration, both for you as a writer and for your readers. By incorporating these best practices, you can create a story that’s not only engaging and informative but also profoundly moving.

And that’s the whole point.

Reflective Writing and Authorial Perspective in Personal Narratives

The heart of a compelling personal story, be it a memoir or an autobiography, lies in its reflective writing and your authorial perspective. These are the elements that make memoirs and autobiographies unique from other genres. And it’s what our readers are looking for.

Here are five final tips to make best use of these elements:

Embrace reflective writing - Reflective writing involves looking back at your experiences and analyzing their impact. It's about understanding the why behind the what. This critical thinking transforms your writing from a simple plot into a journey of personal growth and understanding.

Cultivate a strong authorial voice - While an author’s voice is always important, it does extra work with these genres. It conveys your unique perspective and personality. A strong, consistent voice helps readers connect with your story on a deeper level. And, if you need help refining or developing your voice and tone, click here .

Integrate insights and learnings - Your story should offer insights and learnings, not just for yourself but also for your readers. Share the wisdom gained from your trials and adventures. Turn your personal journey into a relatable, universal tale of human experience.

Use reflection to drive the narrative - Let your reflections and insights drive the plot forward. Your personal growth is just as important in these stories as a fictional character’s arc is in a fantasy epic or hockey romcom. What you learn and realize should push the plot.

Engage the reader with thoughtful questions - Sometimes, posing questions can be more powerful than providing answers. Use reflective questions to engage your readers and prompt them to think about their own experiences and perspectives.

Memoirs and Autobiographies are Still Stories

I know I’ve said this a bunch of times already, but this is something you need to permanently imprint in your writing brain: both memoirs and autobiographies rely on the same core elements as any other story.

It doesn’t matter that they’re based on real life. You still need to understand plot, character development, themes, settings, conflicts, metaphors, point of view, writing habits, and so much more. Then you need to layer everything we’ve discussed here on top of that.

I mentioned equal parts thrilling and terrifying before, right?

Don’t worry, though, because we’ve got you covered. I’ve already given you a bunch of links to relevant guides in this article, but you’ll find hundreds—yes, I’m talking triple digits!—for free over at DabbleU .

And speaking of free, you can click here to get a 100+ page e-book to help you go from idea to finished draft, also for zero dollars and zero cents. Now the only thing left to do is tell your life’s story.

Thrilling. Terrifying. Pretty dang cool.

Doug Landsborough can’t get enough of writing. Whether freelancing as an editor, blog writer, or ghostwriter, Doug is a big fan of the power of words. In his spare time, he writes about monsters, angels, and demons under the name D. William Landsborough. When not obsessing about sympathetic villains and wondrous magic, Doug enjoys board games, horror movies, and spending time with his wife, Sarah.

SHARE THIS:

TAKE A BREAK FROM WRITING...

Read. learn. create..

There are countless ways to master the craft of writing. Is a creative writing class really necessary? It depends! Here's everything you ever wanted to know about taking a writing course, plus tips for picking the best class for you.

Learn how to write dark fantasy, the subgenre that invites you to explore nightmarish landscapes, meet darkly complex characters, and ask unsettling questions about morality.

A character flaw is a fault, limitation, or weakness that can be internal or external factors that affect your character and their life.

Autobiography Writing Guide

Autobiography Vs Memoir

Last updated on: Feb 9, 2023

Autobiography vs. Memoir: Definitions & Writing Tips

By: Barbara P.

Reviewed By: Chris H.

Published on: Mar 2, 2021

Autobiography and memoirs are written to tell the life story of the writer. An autobiography covers the author’s whole life, while a memoir focuses on specific events. These two terms are used interchangeably, but there are obvious and practical differences between the two similar genres.

Writing a memoir and autobiography is a creatively challenging experience, even for the most experienced of writers.

Therefore, read on this blog and get to know the difference and similarities between autobiography vs. memoir.

On this Page

Definition of Memoir vs. Autobiography

The memoir and autobiography are the terms that overlap each other, so the confusion is understandable. These two are the formats that are used to tell a creative non-fiction story. However, there are some differences that you need to know before using the most appropriate one.

Let us discuss the definition of both in detail.

A memoir is based on the author’s real-life experience, and it is written from the author’s point of view. Also, they are not covering their whole life from birth to the present. However, they explore a specific era in great detail, which makes them much different from other writing genres.

Memoirs are more personal and focused on the writer's life. It should be written from the first-person point of view.

The main purpose of the memoir is to:

- Share your personal life experience with the readers.

- Tell the story from the author’s perspective.

- Connect with others who have similar or the same situations.

- Help the people to understand that they are not alone in their experiences.

- Make sense of the threads and themes of their life, as well as identify what's important.

Moreover, the memoir is a type of autobiography that gives a glimpse of the specific event of the writer’s life. Also, the memoir should be:

- Descriptive

- Well-written

The memoir also focuses on the relationship between the author and a particular place or person. Also, they tend to be read more like a fiction novel than a factual account. It includes the following things:

However, for a great memoir, you should share snippets from their life. Also, do not try to tell the entire story in one sitting.

Here is an example that gives you a better idea of the memoir.

Memoir Example

Autobiography

An autobiography focuses on the writer’s entire life and discusses the significant events of their life. It comes through the writer’s own life and in his own words. People write autobiographies to record their feelings and ideas to share with others. Then get it published to reach a greater number of people.

The main purpose of the autobiography is to:

- Inform or teach someone about something.

- Present the facts based on a memoir.

- Focus on the most important events and people in the writer’s life.

- Give you a better insight into how their experiences have shaped them as a person.

Moreover, an autobiography is written in a fictional tale that closely mirrors events from the author’s real life. However, your autobiography should be:

- Easy to read

- Free from obscure details

The below example will help you in writing a good autobiography.

Autobiography Example

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Autobiography vs. Memoir: Differences and Similarities

The autobiography and memoir have some differences and similarities. You must know them before you start writing it.

The below table shows the differences between autobiography and memoir.

Here are some similarities between autobiography and memoir.

- Both use the first-person point of view.

- Both demonstrate the life of the author.

- Focus on the limited aspect of the author’s life.

- Nonfiction literary genre.

- Presents facts as the person experiencing them.

Biography vs. Autobiography vs. Memoir

Some students get confused between biography, autobiography, and memoir. They are not the same and are written for different purposes.

Check the below table and better understand the similarities and differences between biography, autobiography, and memoir.

Memoir vs. Autobiography vs. Personal Narrative

The below table shows the differences and similarities between memoir, autobiography, and personal narrative.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Tips for Writing the Autobiography and Memoir

The following are the tips that you should follow and create a well-written autobiography and memoir.

- Use fiction-writing techniques.

- Write in an engaging way.

- Mention the specific dates of the events.

- Focused on facts.

- Dialogues in memoir should be natural instead of journalistic.

- Do in-depth research.

- Start with a strong hook.

- Use the correct memoir and autobiography format .

- Pick a strong theme.

- Focus on the main events of the person’s life.

Now, you get a complete understanding of the autobiography and memoir. However, if there is still any confusion in writing, then simply consult 5StarEssays.com.

Our essay writer will help you make your writing process easy. All your write my essay requests are managed by professional writers.

So, contact us now and get professional academic help at an affordable rate.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 3 characteristics of a memoir.

The 3 characteristics are:

- It focuses on a specific life event

- The subject becomes alive in the writing

- They are more limited than biographies

Is a memoir more factual than an autobiography?

No! On the contrary, an autobiography is more factual than a memoir. An autobiography encompasses many facts and real incidents from one’s life.

Can we use memoir and autobiography interchangeably?

In some instances, when autobiographies become exceedingly short, they are often called memoirs. However, they are still different in their essence and purpose.

Literature, Marketing

Dr. Barbara is a highly experienced writer and author who holds a Ph.D. degree in public health from an Ivy League school. She has worked in the medical field for many years, conducting extensive research on various health topics. Her writing has been featured in several top-tier publications.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- How to Write an Autobiography - A Complete Guide

- Autobiography Examples – Detailed Outline and Samples

- Know the Different Types of Autobiography Here

- Autobiography Format for Students - A Detailed Guide

People Also Read

- college application essay

- how to write a bio

- essay writing

- thesis statement examples

- essay format

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

What Are the Major Differences Between Memoir and Autobiography?

Rebecca Hussey

Rebecca holds a PhD in English and is a professor at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. She teaches courses in composition, literature, and the arts. When she’s not reading or grading papers, she’s hanging out with her husband and son and/or riding her bike and/or buying books. She can't get enough of reading and writing about books, so she writes the bookish newsletter "Reading Indie," focusing on small press books and translations. Newsletter: Reading Indie Twitter: @ofbooksandbikes

View All posts by Rebecca Hussey

Feeling confused about the difference between memoir and autobiography? You’re not the only one. The terms are sometimes used interchangeably, and there is a lot of overlap between the two, so confusion is understandable. But there are some basic differences that will help you distinguish between them and make sure you are using the most appropriate word. Knowing the difference will help you choose what to read, as well: you should know what you are getting into when you pick up a book labeled memoir vs. autobiography.

First, let’s discuss similarities between the two. Both autobiography and memoir are first-person accounts of the writer’s life. This means the writer is describing her or his life using “I” and “me” (“I did this, then this happened to me,” etc.) One exception to this is that sometimes autobiographies are written in the third person (where the author refers to him or herself as “he” or “she”), but this is not common and rarely seen in contemporary writing. Mostly, both genres are about writers telling readers about their lives in their own voice.

That’s pretty simple. What’s trickier is figuring out what makes these genres different. So here’s a breakdown of the difference between memoir and autobiography, that I’ll discuss more below.

Memoir vs. Autobiography Basics

1. autobiography usually covers the author’s entire life up to the point of writing, while memoir focuses only on a part of the author’s life..

There are going to be exceptions to every point on this list, but generally speaking, autobiography aims to be comprehensive, while memoir does not. Autobiographers set out to tell the story of their life, and while some parts will get more detail than others, they usually cover most or all of it.

Memoirists will often choose a particularly important or interesting part of their life to write about and ignore or briefly summarize the rest. They will sometimes choose a theme or subject and tell stories from different parts of their life that illustrate its significance to them.

As examples, The Autobiography of Malcolm X covers the major points of Malcolm X’s life, while Abandon Me: A Memoir by Melissa Febos focuses mainly on two significant relationships (with her father and with a lover).

2. In autobiography, authors usually tell their life stories because they are famous and important. A memoirist can be anybody, famous or not.

Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, is a good example: he was an important person whose personal account of his life matters because of who he was and everything he accomplished.

For memoir, Mary Karr’s The Liar’s Club is not the story of a famous person; instead, it’s an account of a regular person’s childhood. Her childhood was especially eventful, but it doesn’t stand out because she was famous. Memoirists do sometimes become famous, but usually it’s for writing memoirs.

3. People read autobiographies because they want to know about a particular (probably famous) person. They read memoirs because they are interested in a certain subject or story or they are drawn to the writer’s style or voice.

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin is a book people might read because they want to learn about an important historical figure. They may also have heard it’s exceptionally interesting and well-written, but the desire to learn about a person who shaped U.S. history is probably the main motivation.

On the other hand, readers may pick up Roxane Gay’s memoir Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body because they want to read about food, weight, and body image. Or they may admire Gay’s essays available online and want to explore more of her work. The motivation here is more about subject and style and less about the writer as a historical or cultural figure.

4. Autobiographies tend to be written in chronological order, while memoirs often move back and forth in time.

When readers pick up an autobiography, they expect it to begin with the author’s childhood (or perhaps even with the author’s parents’ lives), to proceed through young adulthood and middle age, through to the time of the writing. Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano does just that, opening with his childhood and proceeding in a straightforward manner through time.

Memoirs, on the other hand, can be much looser in their treatment of time. Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot shifts back and forth in time and has a structure more focused on theme than chronology. We finish the book with a sense of the major events of Mailhot’s life, but not necessarily their order.

5. Autobiography places greater emphasis on facts and how the writer fits into the historical record, while memoir emphasizes personal experience and interiority.

Autobiographies are sometimes thought of as a form of history and they are used as source material for historians. While it’s possible for both autobiographers and memoirists to get their facts wrong, the stakes are higher for the autobiographer who made history or witnessed historically-important events.

Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is important in part because of Douglass’s work as an orator, statesman, and abolitionist. His historical stature adds to the significance of his book.

The facts matter in memoir, but it’s understood that memoirists select and shape the facts of their lives to explore their chosen theme. Darin Strauss’s Half a Life: A Memoir is rooted in a real-life event—a car crash in which Strauss accidentally hit and killed a classmate—but it focuses on the emotional aftereffects of this event rather than the historical context of Strauss’s life.

And there you have it! Again, these distinctions are loose ones, but hopefully they have helped you understand the different connotations of the two words.

Want to read more about memoir? Check out this list of 100 must-read memoirs , this discussion of how to define the term “memoir,” and this post on short memoirs .

You Might Also Like

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

Memoir vs. Autobiography: What Are the Differences?

by Chris Snellgrove

Thinking of writing about your life? In that case, you have a choice to make: a memoir or an autobiography? Each of these types of writing represents a different way to tell your life story.

Often, people hoping to commit their life stories into a book don’t know the difference between autobiography vs. memoir. But once you understand the key differences, you’ll be able to get started writing your emotional truth for the world to see.

What’s the difference between a memoir and an autobiography?

Memoirs and autobiographies are both nonfiction narratives written by the person that they’re about. Autobiographies encompass the entirety of a person’s life story, while memoirs focus on just one powerful experience or a group of experiences. Memoirs cover less time than autobiographies, and are often about conveying a particular message, rather than simply overviewing someone’s life.

We’ll dig deeper into both autobiographies and memoirs below.

What is an autobiography?

An autobiography is a first-person work of nonfiction that’s meant to cover an author’s entire life . Because of this, many choose to write autobiographies later in life when they have more of a life story to share.

You don’t have to be famous to write an autobiography. However, it can be a tough sell convincing the average reader to dive into a subject’s entire life if the subject isn’t someone they’ve heard of before. Having heard of the subject before makes reading about that person’s life seem more interesting.

If you’re not famous, you’ll just need to find a unique perspective or slant to make an engaging story out of your life.

How is an autobiography structured?

Most autobiographies are written in chronological order. This means your autobiography will be an entertaining and detailed chronology of your entire life from beginning to end.

Even though you’re writing creative nonfiction, a reader expects the same things from a good autobiography that he expects from any other narrative: an interesting series of events told in a gripping manner. Once you have this foundation in place , your autobiography should focus on the most important moments in your life.