Home — Essay Samples — Environment — Global Citizen — The Importance of Being an Active and Responsible Citizen

The Importance of Being an Active and Responsible Citizen

- Categories: Global Citizen

About this sample

Words: 648 |

Published: Mar 6, 2024

Words: 648 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Defining good citizenship, importance of good citizenship, role of college students in shaping communities.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Environment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1670 words

2 pages / 868 words

4 pages / 1970 words

5 pages / 2419 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Global Citizen

Global citizenship encompasses a set of values and attitudes that promote understanding, empathy, and action for a better world. It implies a deep commitment to social justice, environmental sustainability, and active civic [...]

In an increasingly interconnected world, the concept of global citizenship has gained prominence. But what does it truly mean to be a global citizen? Is it merely about having a passport that allows you to travel the world, or [...]

In a rapidly evolving world where borders seem to blur and cultures intermingle, the concept of global citizenship has gained immense importance. Hugh Evans eloquently defines a global citizen as someone who identifies primarily [...]

Do we really understand why the world emerged concerning about the Environment issue that make some of us volunteering promotes about the important of sustainable development? The answer is the existing of the global citizen. [...]

There are numerous federal water conservation requirements. Thankfully, the Environmental Protection Agency has created a Water Conservation Strategy to meet the various requirements set by the government. The Water Conservation [...]

Among the largest market for automotive in North America is Canada. Every year the total value of automotive imports to Canada from America increases, for example in 2016 there was a 6% rise which included 9.6% of imports of [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Leadership Council

- Find People

- Fellowships

- Co-Curricular Program

- Student-led Events

- Recent Publications

- Gleitsman Program in Leadership and Social Change

- Hauser Leaders Program

What Does it Mean to Be a Good Citizen?

In this section.

"We don't agree on everything—but we do agree on enough that we can work together to start to heal our civic culture and our country." CPL's James Piltch asked people all over the US what it means to be a good citizen .

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

9. The responsibilities of citizenship

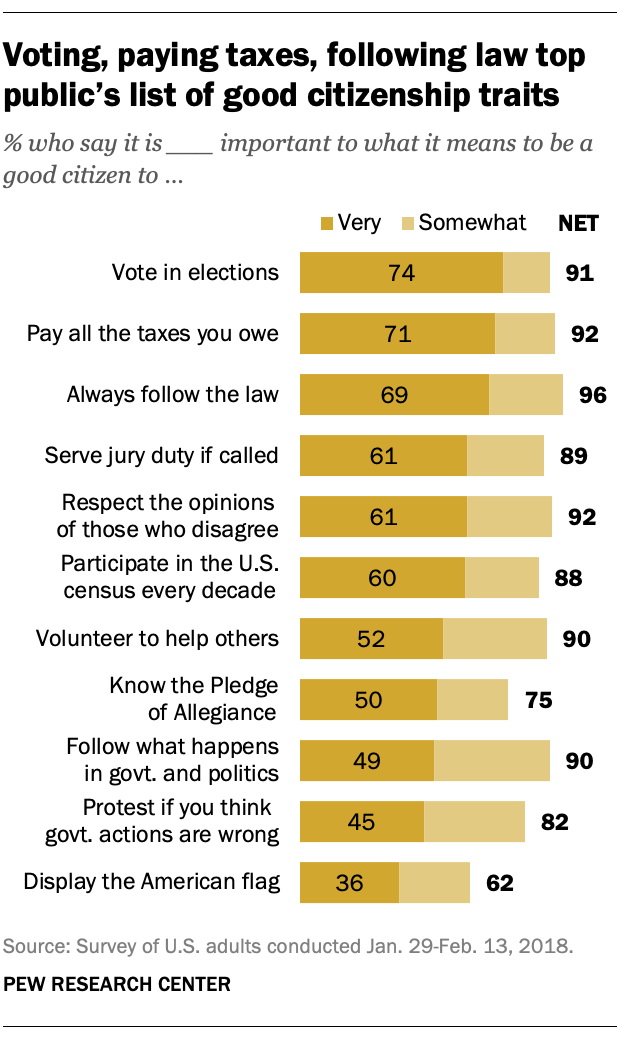

When it comes to what it takes to be a good citizen, the public has a long list of traits and behaviors that it says are important. And there’s a fair amount of agreement across groups about what it takes to be a good citizen.

Still, there are differences when it comes to which aspects are considered very important (as opposed to somewhat important), and points of emphasis differ by party identification as well as by age.

Overall, 91% say it is either very (74%) or somewhat (17%) important to vote in elections in order to be a good citizen; just 8% say this is not too or not at all important.

Large shares also say it is important to pay all the taxes you owe (92%) and to always follow the law (96%), including about seven-in-ten who say each is very important (71% and 69%, respectively).

For several other traits and behaviors, about nine-in-ten say they are at least somewhat important to good citizenship. However, the share saying each is very important varies significantly. For example, 89% say it’s important to serve jury duty if called, including 61% who say this is very important. While a comparable 90% say it’s important to follow what’s happening in government and politics as part of good citizenship, a smaller share (49%) says this very important.

Protesting government actions you think are wrong and knowing the Pledge of Allegiance are considered important parts of what it means to be a good citizen, though they rank somewhat lower on the public’s list. Displaying the American flag ranks last among the 11 items tested in the survey. Still, a majority says this is either a very (36%) or somewhat (26%) important part of what it means to be a good citizen.

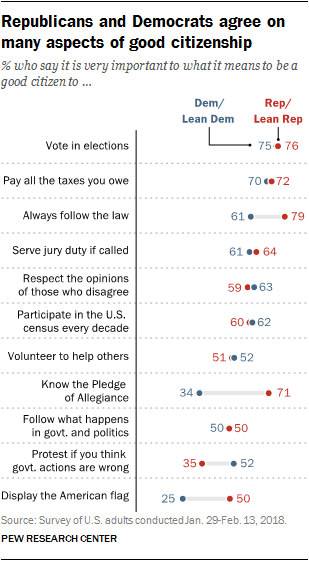

Republicans and Democrats largely agree on the importance of most responsibilities of citizenship.

About three-quarters of Republicans and Republican leaners (76%) and Democrats and Democratic leaners (75%) say it’s very important to vote in elections.

Similarly, comparable majorities of Republicans and Democrats say it’s very important to pay all the taxes you owe, serve jury duty if called, respect the opinions of those you disagree with and participate in the census. There also are no partisan divides over the importance of volunteering to help others and following what’s going on in government and politics.

However, Republicans (79%) are more likely than Democrats (61%) to say it’s very important to always follow the law to be a good citizen.

Knowing the Pledge of Allegiance ranks higher on Republicans’ list (71% say it’s very important) than Democrats’ (just 34% say it’s very important). In addition to placing greater importance on the Pledge of Allegiance, Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to say it is very important to display the American flag (50% vs. 25%).

By contrast, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to think it is very important to protest if government actions are believed to be wrong: About half of Democrats (52%) this is very important to what it means to be a good citizen, compared with just about a third (35%) of Republicans.

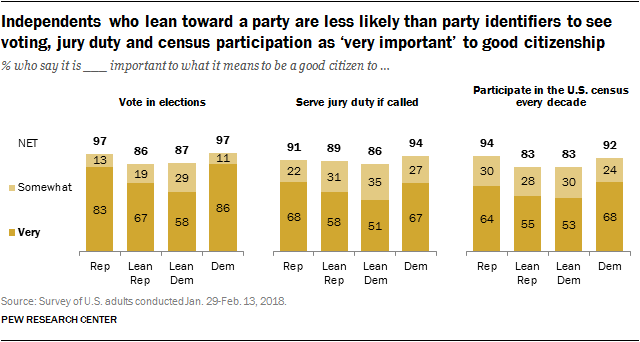

Partisans and ‘leaners’ differ over importance of aspects of citizenship

On many items, the views of independents that lean toward one of the two major parties diverge from those of self-identifying Republicans and Democrats. In general, partisan leaners tend to be less likely than straight Republicans and Democrats to view a range of responsibilities as important to what it means to be a good citizen.

Overall, 83% of Republicans say voting in elections is a very important aspect of being a good citizen, compared with a smaller majority of Republican leaners (67%). There is an even wider 28-point gap between the share of Democrats (86%) and Democratic leaners (58%) who say this is very important.

Similarly, roughly two-thirds of both Republicans (64%) and Democrats (68%) say participating in the U.S. census every 10 years is very important to being a good citizen; slightly fewer Republican leaners (55%) and Democratic leaners (53%) say the same.

This pattern is seen across other items as well: Those who identify with a party are more likely than independents who lean to a party to say it is very important to serve jury duty if called, pay all owed taxes and to follow what is happening in government.

While large shares of Republicans (96%) and Republican leaners (87%) say it is important to know the Pledge of Allegiance, Republican identifiers are somewhat more likely than leaners to say this is very important to good citizenship.

By comparison, smaller majorities of Democrats (67%) and Democratic leaners (60%) say it’s important to know the pledge. Self-identifying Democrats (42%) are significantly more likely to say knowing the pledge is a very important part of good citizenship than Democratic leaners (24%).

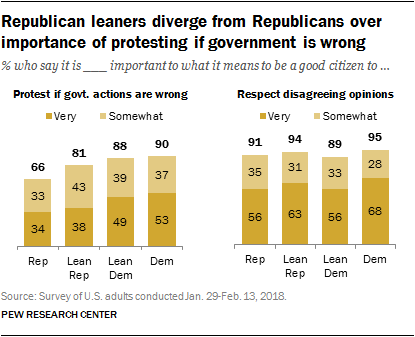

There is a 22-point gap between the share of Republicans (90%) and Republican leaners (68%) who say displaying the American flag is at least somewhat important to being a good citizen. And 63% of Republicans call this very important, compared with 35% of Republican leaners. About half of Democrats (52%) think this is a very or somewhat important aspect of good citizenship; 43% of Democratic leaners say the same.

In contrast to the patterns seen on many items, Republican leaners (81%) are more likely than Republicans (66%) to say protesting government actions you think are wrong is an important part of being a good citizen. The views of Republican leaners place them closer to those of Democrats and Democratic leaners in terms of the overall importance they place on this aspect of citizenship.

Age differences in views of the responsibilities of citizenship

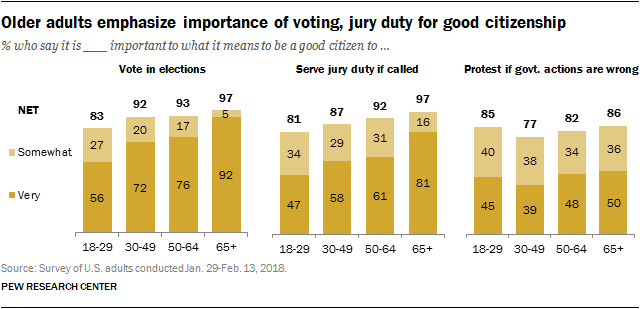

Young adults place less importance on many aspects of citizenship than older adults, especially when it comes to the share that describes a trait or behavior as very important for being a good citizen.

Majorities of adults across all ages say it is very important to vote in elections in order to be a good citizen. Still, a smaller majority of those under 30 say this (56%), compared with larger shares of those ages 30 to 49 (72%), 50 to 64 (76%) and 65 and older (92%).

And while fully 81% of those 65 and older say that to be a good citizen it is very important to serve jury duty if called, just about half (47%) of those under 30 say the same.

On other items, the pattern is similar. Young adults are less likely to call paying the taxes you owe, following the law, participating in the census, and following government and politics very important. Still, large majorities of young adults say each of these is at least somewhat important to being a good citizen.

There is no meaningful age gap in views of the importance of protesting government actions you think are wrong. Overall, 85% of those ages 18 to 29 say this is either very (45%) or somewhat (40%) important to being a good citizen. Views among those ages 65 and older are similar (50% very important, 36% somewhat important).

Displaying the American flag and knowing the Pledge of Allegiance do not rank particularly highly for young adults on their list of important characteristics for good citizenship. Among those ages 18 to 29, 63% say it is important to know the Pledge of Allegiance (38% very important) and 53% say it is important to display the American flag (19% very important). These items do not top the list of older adults either, though those 65 and older are more likely than the youngest adults to say both are important parts of being a good citizen.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

Most Popular

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Citizenship

A citizen is a member of a political community who enjoys the rights and assumes the duties of membership. This broad definition is discernible, with minor variations, in the works of contemporary authors as well as in the entry “ citoyen ” in Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie [1753]. [ 1 ] Notwithstanding this common starting-point and certain shared references, the differences between 18 th century discussions and contemporary debates are significant. The encyclopédiste ’s main preoccupation, understandable for one living in a monarchy, was the relationship between the concepts ‘citizen’ and ‘subject’. Were they the same (as Hobbes asserted) or contradictory (as a reading of Aristotle suggested)? [ 2 ] This issue is less central today as it is often assumed that a liberal democratic regime is an appropriate starting-point for thinking about citizenship. This does not mean, however, that the concept has become uncontroversial. After a long period of relative calm, there has been a dramatic upsurge in philosophical interest in citizenship since the early 1990s (Kymlicka and Norman 1994).

Two broad challenges have led theorists to re-examine the concept: first, the need to acknowledge the internal diversity of contemporary liberal democracies; second, the pressures wrought by globalisation on the territorial, sovereign state. We will focus on each of these two challenges, examining how they prompted new discussions and disagreements.

The entry has four sections. The first examines the main dimensions of citizenship (legal, political, identity) and sees how they are instantiated in very different ways within the two dominant models: the republican and the liberal. The feminist critique of the private/public distinction, central to both models, serves as a bridge to the entry’s second section. It focuses upon two important debates about the implications of social and cultural pluralism to conceptions of citizenship: first, should they recognize, rather than transcend, difference and, if so, does this recognition affect citizenship’s purported role in strengthening social cohesion? Second, how is one to understand the relation between citizenship and nationality under conditions of pluralism? The third section discusses the challenges which globalisation poses to theories of citizenship. These theories have long taken for granted the idea that citizenship’s necessary context is the sovereign, territorial state. This premise is being contested by those who question the state’s right to determine who is accepted as a member and/or claim that citizenship can be meaningful beyond the boundaries of the nation-state. The entry’s fourth and final section looks at how recent discussions in the fields of disability rights and animal rights challenge a basic premise of the literature on citizenship since Aristotle: the idea that discursive rationality constitutes a threshold condition to citizenship.

1.1 Definitions

1.2 two models of citizenship: republican and liberal, 1.3 the feminist critique, 2.1 universalist vs differentialist conceptions of citizenship, 2.2 liberal nationalists vs postnationalists, 3.1 citizenship and borders, 3.2 citizens, non-citizens, and rights, 3.3 debating transnational citizenship: statists vs. globalists, 4. citizenship’s new frontier, 5. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries, 1. dimensions of citizenship.

The concept of citizenship is composed of three main elements or dimensions (Kymlicka and Norman 2000; Carens 2000). The first is citizenship as legal status, defined by civil, political and social rights. Here, the citizen is the legal person free to act according to the law and having the right to claim the law’s protection. It need not mean that the citizen takes part in the law’s formulation, nor does it require that rights be uniform between citizens. The second considers citizens specifically as political agents, actively participating in a society’s political institutions. The third refers to citizenship as membership in a political community that provides a distinct source of identity.

In many ways, the identity dimension is the least straightforward of the three. Authors tend to include under this heading many different things related to identity, both individual and collective, and social integration. Arguably, this is inescapable since citizens’ subjective sense of belonging, sometimes called the “psychological” dimension of citizenship (Carens 2000, 166), necessarily affects the strength of the political community’s collective identity. If enough citizens display a robust sense of belonging to the same political community, social cohesion is obviously strengthened. However, since many other factors can impede or encourage it, social integration should be seen as an important goal (or problem) that citizenship aims to achieve (or resolve), rather than as one of its elements. As we will see, one crucial test for any conception of citizenship is whether it can be said to contribute to social integration.

Relations between the three dimensions are complex: the rights a citizen enjoys will partly define the range of available political activities while explaining how citizenship can be a source of identity by strengthening her sense of self-respect (Rawls 1972, 544). A strong civic identity can itself motivate citizens to participate actively in their society’s political life. That distinct groups within a state do not share the same sense of identity towards ‘their’ political community (or communities) can be a reason to argue in favour of a differentiated allocation of rights (Carens 2000, 168–173).

Differences between conceptions of citizenship centre around four disagreements: over the precise definition of each element (legal, political and identity); over their relative importance; over the causal and/or conceptual relations between them; over appropriate normative standards.

Discussions about citizenship usually have, as their point of reference, one of two models: the republican or the liberal. The republican model’s sources can be found in the writings of authors like Aristotle, Tacitus, Cicero, Machiavelli, Harrington and Rousseau, and in distinct historical experiences: from Athenian democracy and Republican Rome to the Italian city-states and workers’ councils.

The key principle of the republican model is civic self-rule, embodied in classical institutions and practices like the rotation of offices, underpinning Aristotle’s characterization of the citizen as one capable of ruling and being ruled in turn. Citizens are, first and foremost, “those who share in the holding of office” (Aristotle Politics , 1275a8). Civic self-rule is also at the heart of Rousseau’s project in the Contrat Social : it is their co-authoring of the laws via the general will that makes citizens free and laws legitimate. [ 3 ] Active participation in processes of deliberation and decision-making ensures that individuals are citizens, not subjects. [ 4 ] In essence, the republican model emphasizes the second dimension of citizenship, that of political agency.

The liberal model’s origins are traceable to the Roman Empire and early-modern reflections on Roman law (Walzer 1989, 211). The Empire’s expansion resulted in citizenship rights being extended to conquered peoples, profoundly transforming the concept’s meaning. Citizenship meant being protected by the law rather than participating in its formulation or execution. It became an “important but occasional identity, a legal status rather than a fact of everyday life” (Walzer 1989, 215). The focus here is on the first dimension: citizenship is primarily understood as a legal status rather than as a political office. It now “denotes membership in a community of shared or common law, which may or may not be identical with a territorial community” (Pocock 1995, 37). The Roman experience shows that the legal dimension of citizenship is potentially inclusive and indefinitely extensible.

The liberal tradition, which developed from the 17 th century onwards, understands citizenship primarily as a legal status: political liberty is important to protect individual freedoms from interference by other individuals or the authorities themselves. Citizens exercise these freedoms primarily in the world of private associations and attachments, rather than in the political domain.

At first glance, the two models offer a clear set of alternatives: citizenship as a political office or a legal status; central to an individual’s sense of self or as an “occasional identity”. The citizen appears either as the primary political agent or as an individual whose private activities leave little time or inclination to engage actively in politics, entrusting the business of law-making to representatives. If the liberal model of citizenship dominates contemporary constitutional democracies, the republican critique of the private citizen’s passivity and insignificance is still alive and well.

Republicans have problems of their own. First and foremost is a concern, often repeated since Benjamin Constant, that their ideal has become largely obsolete in the changed circumstances of the “ grands États modernes ” (Constant 1819). Aiming to realize the original republican ideal in the present context would be a disaster, as was the Jacobins’ attempt during the French revolution (Walzer 1989, 211). Today’s citizens will not be Romans: first, the scale and complexity of modern states seem to preclude the kind of civic engagement required by the republican model. If an individual’s chances of having an impact as an active citizen are close to nil, then it makes more sense for him to commit himself to non-political activities, be they economic, social or familial. His identity as citizen is not central to his sense of self and politics is only one of his many interests (Constant 1819, 316). Second, the heterogeneity of modern states does not allow the kind of “moral unity” and mutual trust that has been projected onto the ancient polis , qualities deemed necessary to the functioning of republican institutions (Walzer 1989, 214). However, if ancient virtue is irrecoverable, the republican model may still act today as “a benchmark that we appeal to when assessing how well our institutions and practices are functioning” (Miller 2000, 84). In essence, this involves a reformulation of the model, questioning some of its original premises while holding onto the ideal of the citizen as an active political agent.

Instead of opposing the two models, we could reasonably see them as complementary. Political liberty, as Constant pointed out, is the necessary guarantee of individual liberty. Echoing Constant, Michael Walzer considers that the two conceptions “go hand in hand” since “the security provided by the authorities cannot just be enjoyed; it must itself be secured, and sometimes against the authorities themselves. The passive enjoyment of citizenship requires, at least intermittently, the activist politics of citizens” (Walzer 1989, 217). There are times when individuals need only be “ private citizens” and others when they must become “private citizens ” (Ackermann 1988). Can we expect passive spectators of political life to become active citizens should the need arise? This is no easy question and may explain why Constant ended his famous essay by insisting that the regular exercise of political liberty is the surest means of moral improvement, opening citizens’ minds and spirits to the public interest, and to the importance of defending their freedoms. Such habituation underpins their capacity and willingness to protect their liberties and the institutions that support them (Constant 1819, 327–328). [ 5 ]

Since the 1970s, feminist theorists have sharply criticized the republican and liberal models’ shared assumption of a rigid separation between the private and the public spheres. Their critique has provided the impetus to the development of alternative conceptions of politics and citizenship.

In its classical formulation, the republican conception sees the public/political sphere as the realm of liberty and equality: it is there that free, male citizens engage with their peers and deliberate over the common good, deciding what is just or unjust, advantageous or harmful (Aristotle Politics , 1253a11). The political space must be protected from the private sphere, defined as the domain of necessity and inequality, where the material reproduction of the polis is secured. Women, associated with the ‘natural world’ of reproduction, are denied citizenship and relegated to the household.

Feminists have criticized this rigid division as mythical since both the separation itself and the radically unequal conception of the household that it presupposed “were clearly the outcome of political decisions made in the public sphere” (Okin 1992, 60). If the division ostensibly made it possible for citizens to engage with each other as equals, feminists doubt whether it ever was the ideal way of achieving this goal. Hence Susan Okin’s question to republicans: “Which is likely to produce better citizens, capable of acting as each other’s equals? Having to deal with things part of the time — even the ‘mundane’ things of daily life? Or treating most people as things? ” (Okin 1992, 64–65). An egalitarian family is a much more fertile ground for equal citizens than one organized like a school for despotism (J.S. Mill); if this means that the political space cannot remain insulated from the world of things, there’s no great loss.

The liberal model, for its part, gives primacy to the private sphere. Political liberty is seen in instrumental terms: the formal rights of individuals secure the private sphere from outside interference, allowing the free pursuit of their particular interests (Dietz 1998, 380–81). However, the neutral language of Lockean egalitarian individualism hides the reality of women’s subjection: “woman’s sphere” can be read as “male property” since wives are described as naturally subordinated to their husbands. Here as well, the division between private and public has prevented women from gaining access to the public (Pateman 1989, 120; Dietz 1998, 380–81; Okin 1991, 118).

Since the public and private “are, and always have been, inextricably connected” (Okin 1992, 69), the upshot of the feminist critique is not simply to make models of citizenship inclusive by recognizing that women are individuals or to acknowledge that they too can be citizens. Rather, we must see how laws and policies structure personal circumstances (e.g. laws about rape and abortion, child-care policies, allocation of welfare benefits, etc.) and how some ‘personal problems’ have wider significance and can only be solved collectively through political action (Pateman 1989, 131). This does not make the distinction irrelevant and the categories collapsible. However, it does mean that the boundaries between public and private should be seen as a social construction subject to change and contestation and that their hierarchical characterization should be resisted.

Once the abstractions that characterize both the classical and the liberal conceptions are discarded, the citizen sheds his “political lion skin” (Pateman 1989, 92 quoting Marx 1843) and appears as “situated” in a social world characterized by differences of gender, class, language, race, ethnicity, culture, etc. To accept that politics cannot and should not be insulated from private/social/economic life is not to dissolve the political, but, rather, to revive it since anything is as political as citizens choose to make it. This contextualized conception of the political has informed much of the criticism aimed at the universalist model of citizenship and has inspired the formulation of a differentialist alternative.

2. The challenge of internal diversity

The universalist or unitary model defines citizenship primarily as a legal status through which an identical set of civil, political and social rights are accorded to all members of the polity. T.H. Marshall’s seminal essay “Citizenship and Social Class” is the main reference for this model, which became progressively dominant in post-World War II liberal democracies. Marshall’s central thesis was that the 20 th century’s expansion of social rights was crucial to the working class’s progressive integration in British society (Marshall 1950). [ 6 ] Similar stories were told in other Western democracies: the development of welfare policies aimed at softening the impact of unemployment, sickness and distress was fundamental to political and social stability. The apparent success of the post-war welfare state in securing social cohesion was a strong argument in favour of a conception of citizenship focused on the securing of equal civil, political and social rights.

The universalist model was aggressively targeted at the end of the 1980s as the moral and cultural pluralism of contemporary liberal societies elicited increasing theoretical attention. Scepticism towards the universalist model was spurred by concerns that the extension of citizenship rights to groups previously excluded had not translated into equality and full integration, notably in the case of Afro-Americans and women (Young 1989; Williams 1998). A questioning of the causal relation assumed between citizenship as a uniform legal status and civic integration followed.

Critics argued that the model proves exclusionary if one interprets universal citizenship as requiring (a) the transcendence of particular, situated perspectives to achieve a common, general point of view and (b) the formulation of laws and policies that are difference-blind (Young 1989). The first requirement seems particularly odious once generality is exposed as a myth covering the majority’s culture and conventions. The call to transcend particularity too often translates into the imposition of the majority perspective on minorities. The second requirement may produce more inequality rather than less since the purported neutrality of difference-blind institutions often belies an implicit bias towards the needs, interests and identities of the majority group. This bias often creates specific burdens for members of minorities, i.e. more inequality.

Critics of this (failed) universalism have proposed an alternative conception of citizenship based on the acknowledgment of the political relevance of difference (cultural, gender, class, race, etc.). This means, first, the recognition of the pluralist character of the democratic public, composed of many perspectives, none of which should be considered a priori more legitimate. Second, it entails that, in certain cases at least, equal respect may justify differential treatment and the recognition of special minority rights.

Once these two points are conceded, the question becomes when, and for what reason, the recognition of particular rights is either justified or illegitimate. This discussion is necessarily context specific, focusing on concrete demands made by groups in particular circumstances, and shies away from easy generalizations. It has led to an array of publications covering issues ranging from the fate of ‘minorities within minorities’ to how tolerant liberal societies should be of illiberal groups, etc. [ 7 ]

The model of differentiated citizenship has generated its own share of criticisms and queries, particularly with regards to the overall effects of its implementation. Critics focus on its impact on the possibility of a common political practice. Consider Iris Young’s vision of a heterogeneous public where participants start from their “situated positions” and attempt to construct a dialogue across differences. This dialogue requires participants to be ‘public-spirited’ — open to the claims of others and not single-mindedly self-interested. Unlike interest group pluralism, which does not require justifying one’s interest as right or as compatible with social justice, participants are supposed to use deliberation to come to a decision that they determine to be best or more just (Young 1989, 267). While welcoming Young’s conception of the democratic public, one may doubt that the policies and institutions associated with a differentiated model of citizenship would either motivate or enable citizens to engage in such dialogue.

This analysis is tied to a wider literature on the virtues required of citizens in pluralist liberal democracies and on ways to favour their development. Stephen Macedo (1990), William Galston (1991), and Eamonn Callan (1997), among others, have all emphasized the importance of public reasonableness. This virtue is defined as the ability to listen to others and formulate one’s own position in a way that is sensitive to, and respectful of, the different experiences and identities of fellow citizens, acknowledging that these differences may affect political views. This raises many questions: how and where does one develop this and related virtue(s)? If a differentiated model of citizenship simply allows individuals and groups to retreat into their particular enclaves, how are they to develop either the motivation or the capacity to participate in a common forum?

This explains the abiding interest of political philosophers in education. If citizens of diverse societies are to develop the ‘right’ attitudes and dispositions, does this mean encouraging a common education, the development of a school curriculum that teaches respect for difference, while providing the necessary skills for democratic discussion across these differences? In this case, should demands for separate schools or dispensations for minorities be resisted? How flexible should public schools be towards minorities if the goal is to make them feel welcome and ensure that they do not retreat into parochial institutions (Callan 1997; Gutmann 1999; Brighouse 2000, 2006)? [ 8 ]

Critics of differentiated citizenship have also argued that policies that break with difference-blind universalism weaken the integrative function of citizenship. If embracing multicultural and minority rights means that citizens lose their sense of collective belonging, it may also affect their willingness to compromise and make sacrifices for each other. Citizens may then develop a purely strategic attitude towards those of different backgrounds. As Joseph Carens puts it: “From this perspective, the danger of […] differentiated citizenship is that the emphasis [it] place[s] on the recognition and institutionalization of difference could undermine the conditions that make a sense of common identification and thus mutuality possible” (Carens 2000, 193).

In addressing these and similar queries, Will Kymlicka and Wayne Norman have broadly distinguished between three types of demands: special representation rights (for disadvantaged groups), multicultural rights (for immigrant and religious groups) and self-government rights (for national minorities) (Kymlicka and Norman 1994; Kymlicka, 1995, 176–187). The first two are really demands for inclusion into mainstream society: special representation rights are best understood as (temporary) measures to alleviate the obstacles that minorities and/or historically disadvantaged groups face in having their voices heard in majoritarian democratic institutions. Reforming the electoral system to ensure the better representation of minorities may raise all sorts of difficult issues, but the aim is clearly integration into the larger political society, not isolation.

Similarly, the demands for multicultural rights made by immigrant groups are usually aimed either at exemption from laws and policies that disadvantage them because of their religious practices or at ensuring public support for particular education and/or cultural initiatives to maintain and transmit elements of their cultural and religious heritage. These should be seen as measures designed to facilitate their inclusion in the larger society rather than as a way to avoid integration. It is only claims to self-government rights, grounded in a principle of self-determination, that potentially endanger civic integration since their aim is not to achieve a greater presence in the institutions of the central government, but to gain a greater share of power and legislative jurisdiction for institutions controlled by national minorities.

Addressing this kind of demand through a simple reaffirmation of the ideal of common citizenship is not a serious option. It may only aggravate the alienation felt by members of these groups and feed into more radical political projects, including secession. Further, to say that recognition of self-government rights may weaken the bonds of the larger community is to suppose that these bonds exist in the first place and that a significant proportion of national minorities identify with the larger society. This may be overly optimistic. If these bonds do not exist, or remain quite weak, what is needed is the construction of a genuine dialogue between the majority society and minorities over what constitutes just relations, through which difference can be recognized. The hope is that dialogue would strengthen, rather than weaken, their relationship by putting it on firmer moral and political grounds (Carens 2000, 197).

This broadly positive assessment of the effects of differentiated citizenship on civic integration is contested. On the one hand, left-leaning authors have complained that multicultural politics make egalitarian policies more difficult to achieve by diverting “political effort away from universalistic goals” and by undermining efforts to build a broadly based coalition supporting ambitious policies of redistribution (Barry 2001, 325). On the other hand, events like September 11, the Mohammed cartoons affair (2005, see Klausen 2009), riots in the banlieux of Paris (2005), London (2011) and Stockholm (2017), as well as a series of terrorist attacks in Europe have led to a backlash against multicultural policies. The belief that demands for multicultural rights are really demands for inclusion in the larger society has been thrown into doubt, notably in the case of Muslim immigrants.

To allay fears about the supposed trade-off between cultural recognition and redistribution, supporters of multiculturalism cite the lack of empirical studies establishing a negative correlation between the adoption of multicultural policies and a robust welfare state (Banting and Kymlicka 2006, Banting 2005). Further, claims that the push for multicultural policies diverts energies, time and resources from the struggle for redistributive policies assume that the pursuit of justice is zero-sum, seemingly a false generalization. On the contrary, it can be argued that: “the pursuit of justice in one dimension helps build a broader political culture that supports struggles for justice in other dimensions” (Kymlicka 2009). In the same vein, to claim that paying attention to issues of cultural recognition tends to warp our sensitivity to economic injustice is to assume that we can only be sensitive to one dimension of injustice at a time. However, it is equally plausible that sensitivity to a particular type of injustice may favour, rather than hinder, sensitivity to other injustices.

In response to concerns about social and civic unity, liberal democracies have introduced a series of policies aimed at better securing the integration of immigrants: requiring minimal linguistic proficiency in the majority language as a condition of citizenship or banning religious symbols from public schools. These policies have sometimes been heralded as signaling the development of a ‘muscular liberalism’ (Former British PM David Cameron, quoted by Joppke 2014) as an alternative to multiculturalism. They have been hotly debated from the perspective of factual efficacy as well as from a normative perspective. The introduction of ‘citizenship tests’ for resident immigrants has led to a vigorous debate among normative theorists: under what conditions and in what form can they be justified? Some, like Carens (2010a), have argued that they are basically unjust, no matter what form they take. If one understands membership in a society to flow from long-term residence, as Carens does, then any test that “prevents a full member of a society from becoming a citizen unjustly deprives her of an entitlement to citizenship” (Mason 2014, 143). Other theorists have taken a more positive view of the tests: seeing them as an incentive for immigrants to acquire basic knowledge of liberal-democratic principles, as well as the political institutions and history of the host country. As such, they also serve as an “implicit statement of the nation’s political values” (Miller 2016, 138). On this view, as long as certain conditions are met, so that the tests are neither too difficult nor too expensive and give applicants the possibility to take them again if they fail, etc., then there is nothing deeply objectionable to them (though the empirical question of their efficacy remains open). In contrast, tests that purport to ‘weed out’ immigrants who do not share ‘our’ liberal values are generally held to be incompatible with liberal principles. This has led some theorists to question how ‘muscular’ can liberalism really be (Joppke 2014).

In the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, some liberal democracies have introduced legislation giving the state the power to revoke the citizenship of those convicted or suspected of terrorist activities. [ 9 ] Given the principle recognized in international law that no one should be left stateless, these legislations usually apply only to citizens holding dual or multiple citizenships. ‘Denationalisation’ is sometimes described in this context as “a technique for extending the functionality of immigration law in counter-terrorism” (Macklin 2015, see also Barry and Ferracioli 2016). Though states cannot deport their own citizens, denationalisation allows them to first withdraw citizenship and then deport. These legislations raise several normative issues. Firstly, they seem to contradict the basic idea that citizenship is a fundamental right, not a privilege (Lenard 2018; Gibney 2013; Macklin 2015). Secondly, since they weaken the security normally attached to the status of citizen, they can be described as demoting citizenship “to another category of permanent residence” (Macklin 2015). Thirdly, it is argued that by targeting only dual (or multiple) citizens, the new legislations treat them as second-class citizens (Gibney 2013, 653). In contrast, other theorists insist that that the nature of terrorist crimes (akin to acts of war against the state) warrants this kind of response (Schuck 2015; Joppke 2015). Concerning the worry that the legislations discriminate against dual citizens, the response is that the difference in treatment between mono-citizens and dual citizens is justified since the consequences of denationalisation are also very different in each case. Individuals holding a single citizenship are the only ones facing statelessness as a consequence of denationalisation (Barry and Ferracioli 2016). Where participants in the debate find some common ground is in their shared criticism of the specific form that some legislations have taken, most notably the 2006 British Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act. In the wake of the 7 July 2005 Tube bombing in London, the Act replaced the standard for deprivation present in the 2002 legislation (the “vital interests of the state” test) with a much weaker and vague standard providing for revocation in cases where an individual’s holding citizenship is “not conducive to the public good” (quoted by Gibney 2013, 650). Also deeply concerning is the progressive expansion of legislative measures to allow for “ proactive and administrative denationalisation” (Brown Prener 2023, 3–4). While the efficiency of denationalisation as a measure aimed at reducing the incidence of terrorist activity remains doubtful, its value appears to be primarily symbolic, expressing what some authors see as a ‘fitting’ response of liberal democracies to those intent on attacking their very foundations (Barry and Ferracioli 2016; see Lenard 2018 for a counterargument). This symbolic understanding of denationalisation highlights the persistent significance of the language of allegiance in contemporary liberal democratic thought, though some argue that this very language is incompatible with liberal democratic principles (Irving 2022).

Worries about the integration of Muslim immigrants in Western liberal democracies have fostered a persisting interest in the complex relations between the liberal political cultures dominant in the West, the different versions of secularism that they affirm, religion, and citizens of faith. Research has focused on religion’s place in the public sphere (Parekh 2006, Laborde 2008, Brahm Levey and Modood 2009, Modood 2019) as well as on the relation between religion, gender, and citizenship. [ 10 ]

The debate between supporters and critics of differentiated citizenship centres on the model’s supposed effect on civic integration. It is assumed that democratic citizenship, properly construed, can indeed function as a significant lever for integration. The idea is that citizenship as a set of civil, political and social rights and as a political practice can help generate desirable feelings of identity and belonging. This statement hides significant disagreement over how to characterize the relation between citizenship and nationality. Some consider that citizenship’s capacity to fulfil its integrative function depends on, and feeds upon, the prior existence of a common nationality while others counter that, under conditions of pluralism, nationality cannot function as a suitable focus of allegiance and identity. The collective identity of modern democratic states should rather be based upon more abstract and universalistic political and legal principles that transcend cultural difference. This debate brings to the fore differing assessments of the role that citizenship can play in contemporary societies characterized by a high degree of complexity and internal diversity.

Liberal nationalists like David Miller have argued that only specific forms of political practice can produce high levels of trust and loyalty between citizens (Miller 2000, 87). The political activities of the citizens of Athens or of Rousseau’s ideal Republic presumed face-to-face relations of cooperation that favour the growth of such sentiments. The scale and complexity of modern states have made the kind of political practice envisaged by Rousseau and described by Aristotle at best marginal. Citizens do not meet under an oak tree to formulate the laws; they are basically strangers and citizens’ involvement in the politics of representative democracies is episodic and diluted. Politics in this context cannot be expected to play a central role in most individuals’ lives; something else must generate the trust and loyalty necessary to the functioning of a political community. Historically, it is the nation that has allowed large numbers of individuals to feel a sense of commonality, setting them apart from others and making solidarity among strangers possible.

Postnationalists do not dispute the key role played by the nation in making republican politics possible in large modern states. They agree that reference to a common nationality allowed the political mobilization of their inhabitants, calling on their shared descent, history, or language. However, democracy’s association with the nation-state is contingent rather than necessary. Democratic politics can, in principle, free itself from its historical moorings. Postnationalists claim that this dissociation is not only possible, but necessary for moral and pragmatic reasons (Habermas 1998, 132).

On the one hand, the historical balance sheet of the nation-state reveals a legacy of oppression of minority cultures within and cultural, political, and economic imperialism outside its borders. On the other hand, the acknowledgment of the nation-state’s (growing) internal diversity and sensitivity to the injustice of forced assimilation undermine its ability to continue playing the role it fulfilled in the 19 th and early 20 th centuries. Imposing the majority culture upon minorities may simply make it more difficult for them to identify with the nation-state and weaken its legitimacy.

In conditions of pluralism, therefore, the majority culture cannot serve as the grounding of a shared identity. It must be replaced by universalistic principles of human rights and the rule of law, which do not, it is argued, imply the imposition of a particular majority culture on minorities. Each political community develops distinctive interpretations of the meaning of these principles over time, which become embodied in its political and legal institutions and practices. These in turn form a political culture that crystallizes around the country’s constitution and makes those principles into a ‘concrete universal’. This embedding of democratic and liberal principles in a distinctive political culture can, in turn, give rise to what Jürgen Habermas has called a “constitutional patriotism”, which should replace nationalism as the focus of a common identity. In countries that have achieved a strong national consciousness, the political culture has long been entangled with the majority culture. This “fusion”, argues Habermas, “must be dissolved if it is to be possible for different cultural, ethnic, and religious forms of life to coexist and interact on equal terms within the same political community” (Habermas 1998, 118).

The thrust of the argument is that democratic political practice can provide a sufficient stimulus to integration in complex democratic societies and is indeed the only one properly available to them. There is no need for a background consensus based on cultural homogeneity to act as a ‘catalyzing condition’ for democracy to the extent that the democratic political process, involving public deliberation and decision-making, makes “a reasonable political understanding possible, even among strangers.” Democracy, as a set of procedures, can secure legitimacy in the absence of more substantive commonalities between citizens and achieve social integration. Since it is not wedded to particular cultural premises, it can be responsive to changes in the cultural composition of the citizenry and generate a common political culture (Habermas 2001a, 73–74). Habermas’s position, then, gives pride of place to the democratic process and to the political participation of citizens, which play a key role in securing social integration: “In complex societies, it is the deliberative opinion- and will-formation of citizens, grounded in the principles of popular sovereignty, that forms the ultimate medium for a form of abstract, legally constructed solidarity that reproduces itself through political participation” (Habermas 2001a, 76).

However, the democratic process can fulfil its role only if it achieves a certain level of output legitimacy: appropriate levels of solidarity are sustainable only if basic standards of social justice are satisfied (Habermas 2001a, 76). If it is to remain a source of solidarity, citizenship must be seen as a valuable status, associated not only with civil and political rights, but also with the fulfilment of fundamental social and cultural rights (Habermas 1998, 118–119).

For most liberal nationalists, this seems like putting the cart before the horse since a successful welfare state, they argue, is possible only if citizens already enjoy high levels of mutual trust and loyalty. Welfare policies suppose that we make sacrifices for anonymous others who differ from us in terms of their ethnic origin, religion, and way of life. But in democracies, redistributive policies can be sustained only if they enjoy strong levels of public support. This support is dependent on a sense of common identity that transcends difference and motivates citizens to share their revenues with people whom they do not know, but to whom they feel related by common bonds. This sentiment implies reciprocity: the expectation that, in times of need, one could also benefit from the solidarity of fellow citizens (Miller, 1995; Canovan, 1996).

Liberal nationalists and other critics of the postnationalist position go on to argue that freeing the liberal democratic state from its historical moorings is neither possible, nor necessary. They recognize that the link between liberal democracy and the nation is historically contingent rather than necessary or conceptual while adding that this does not mean that they can or should be dissociated (Miller 1995, 29–30; Kymlicka 2003). Calling for the separation of a country’s political culture from the majority group’s culture is easier said than done. While it may be comparably easy to discard the most egregious forms of fusion, if there is the political will to do so (for instance, by de-establishing the Anglican church in the case of England), any political culture will be ethically patterned in ways that are difficult for members of the majority to appreciate. Expressions such as “cutting the umbilical cord” or “dissolving” the fusion overstate the extent to which a political culture may be disengaged from the background culture. This is not necessarily cause for alarm, it is argued, since the nation need not be construed in ways that exclude minorities. Nationhood can be understood in sufficiently ‘thin’ terms to accommodate minorities while being ‘thick’ enough to generate appropriate sentiments of solidarity, loyalty, and trust.

There are different versions of this thin understanding of nationhood. What they share is the downplaying of substantive commonalities of descent, culture and religion in favour of political and legal principles and institutions as well as a description of national identity as flexible and open to change . [ 11 ] Once immigrants are citizens, they can participate in the collective conversation in which citizens debate and constantly reinterpret the nation’s identity. What immigrants are required to display is a “willingness to accept current political structures and to engage with the host community so that a new common identity can be forged” (Miller 1995, 129). They are expected “to speak a common national language”, “feel loyalty to national institutions” and “share a commitment to maintaining the nation as a single, self-governing community into the indefinite future” (Kymlicka 2003, 273).

Given the thin version of national identity they propose, one might conclude that liberal nationalists are not that far from the constitutional patriotism of Habermas. After all, both positions seem to give the central role to a common political culture. The distance separating them becomes clear when we look at the political implications of their respective views, like when evaluating the prospects of the European Union. Liberal nationalists are often sceptical towards the European experiment while postnationalists are firm supporters. [ 12 ] This difference flows from their respective conceptions of what makes and sustains a political culture as a source of integration. For liberal nationalists, continuity is essential: a political culture derives much of its strength from an anchoring in the history and narrative of a distinct political community extending backwards and forwards in time. They are sceptical of political voluntarism and of what can be achieved through formal political institutions. Democratic procedures alone, divorced from a richer background, can neither generate nor sustain a robust political culture or a sense of common identity.

In contrast, postnationalists like Habermas consider that the democratic process is crucial. The postnationalist conception gives greater weight to political practice and to the legal and political institutions that sustain it rather than to their cultural and historical moorings. This explains Habermas’s militant support of the European project and his belief that adopting a constitution could have a “catalytic effect” on the process of constructing a ‘more perfect Union’ (Habermas 2001b, 16).

3. The challenge of globalisation

For the better part of the last century, conceptions of citizenship, despite many differences, have had one thing in common: the idea that the necessary framework for citizenship is the sovereign, territorial state. The legal status of citizen is essentially the formal expression of membership in a polity that has definite territorial boundaries within which citizens enjoy equal rights and exercise their political agency. In other words, citizenship, both as a legal status and as an activity, is thought to presuppose the existence of a territorially bounded political community, which extends over time and is the focus of a common identity. In the last thirty years, this premise has come under scrutiny. A host of phenomena, loosely associated under the heading ‘globalisation’, have encouraged this critical awakening: exploding transnational economic exchange, competition and communication as well as high levels of migration, of cultural and social interactions have shown how porous those borders have become and led people to contest the relevance and legitimacy of state sovereignty.

Three questions are particularly salient. First, the intensification of migratory movements from poorer to richer countries in the context of growing inequalities between North and South has led some authors to contest the state’s moral right to choose its members by selectively closing its borders. Second, what R. Bauböck calls the “mismatch between citizenship and the territorial scope of legitimate authority” (Bauböck 2008, 31) has prompted a growing questioning of the acceptability of the different rights accorded to citizens and non-citizens living within the same state. Does contesting the tight association between the territorial state, citizenship, and rights risks weakening the very institutional framework that makes citizenship a meaningful practice? This question raises a third set of issues as it assumes that the democratic nation-state is the only institutional context in which citizenship can thrive. This is contested by those who claim that citizenship can be exercised in a multiplicity of ‘sites’ both below and above the nation-state.

Does the state have the moral right to decide who can become a citizen or is there a fundamental right to free movement? The philosophical debate has largely focused on two issues: first, on the nature of obligations that wealthy states have towards people from impoverished countries who seek better lives for themselves and their families; secondly, on the moral status of political communities and their supposed right to protect their integrity by excluding non-members.

One way of characterizing one’s obligations towards strangers is to insist that, absent any relations of cooperation, common humanity is our only bond. Only a weak, imperfect or conditional duty of assistance, it is argued, can be inferred from this premise. This duty limits the basic right of a political community to distribute membership as it wishes without, in any way, displacing it. Individuals have a duty to assist strangers in urgent need if they can help without exposing themselves to significant risk or cost. At a collective level, the implications are more considerable as political communities have greater resources and can consider a broader range of benevolent actions at comparably negligible cost. The principle of mutual aid may justify redistribution of membership, territory, wealth and resources to the extent that certain states have more than they can reasonably be said to need (Walzer 1983, 47). However, in this framework redistributive policies remain entirely dependent on wealthier countries’ understanding of their needs and of the urgency of a stranger’s situation. There is no obligation to give equal weight to the interests of non-members.

Institutionally, this position supports what the Geneva Convention on the Status of Refugees (United Nations 1951) calls the principle of “ non refoulement ”: signatory states are not to deport refugees and asylum seekers to their countries of origin if this threatens their lives and freedom. It can also support claims in favour of increasing the number of immigrants admitted into richer countries, depending on how the latter evaluate the potential effects on their own interests.

Critics contend that obligations towards migrants and asylum-seekers go well beyond this and call for a policy of open borders and/or deny the state’s right to decide alone who exactly, and how many people, may enter its territory. Three basic strategies are employed: the first consists of arguing that freedom of movement is a fundamental human right. For example, some have argued that any theory recognizing the equal moral value of individuals and giving them moral primacy over communities cannot justify rejecting aliens’ claims to admission and citizenship. As Carens demonstrated in an early article, this argument applies to the three main strands of contemporary liberal theory: libertarianism ( à la Nozick), Rawlsianism and utilitarianism (Carens 1987). If the principle of moral equality is given its full extension, the distinction between citizen and alien appears as morally arbitrary, justified neither by nature nor achievement. When evaluating border and immigration policies, the equal consideration of the interests of all affected (be they aliens or citizens) is required. Political communities cannot decide whether they can afford to accept refugee claimants or prospective immigrants simply according to their understanding of their own situation, needs and interests. Consideration of consequences (e.g. in terms of public order, the sustainability of welfare policies, the potential effects of a brain drain in developing countries, etc.) is not prohibited; what changes radically is how we are to evaluate them. Institutionally, this would doubtless lead to substantial changes in the immigration and refugee policies of most Western democracies.

A second strategy advocated by Arash Abizadeh (2008) relies on the principle of democratic legitimacy, holding that the exercise of coercive power is legitimate “only insofar as it is actually justified by and to the very people over whom it is exercised” (41). Since a regime of border control subjects both citizens and non-citizens to the state’s coercive use of power, “the justification for a particular regime of border control is owed not just to those whom the boundary marks as members, but to nonmembers as well” (45) [ 13 ] . The argument’s upshot is that no democratic state has the right to unilaterally control its own borders, but must either allow freedom of movement or, at the very least, give voice to prospective immigrants when formulating border policy. The latter condition would itself lead to significant changes in immigration policies in the Western world, since jointly controlled borders would presumably be more porous as well.

The third strategy is less direct. To the extent that states do not satisfy their moral obligations to guarantee the universal human right to security and subsistence through international redistributive policies, they have a moral obligation to admit those wishing to enter. Here the idea of open borders is an instrumental, rather than intrinsic, moral principle: it is a means towards achieving global distributive justice (Bader 1997). The advantage of this line of argument is that it closely reflects a central motivation for open borders: the outrage provoked by the huge inequalities between North and South and rich countries’ role in perpetuating this situation. This strategy, if successful, would establish specific rights for people from poorer countries towards the North, rather than a broadly framed right to free movement, to be ‘equally’ enjoyed by individuals of rich and poor countries alike.

To be convincing the argument must show: first, that severe global poverty requires immediate action; second, that it is a matter of justice, not charity. To that effect, it is crucial to show that the extreme poverty of some countries is not simply the result of endogenous factors (e.g. bad governance; corrupt political culture, etc.), but is linked to a global political and economic order that systematically produces an unjust distribution of resources and political power, which rich northern countries, as its main beneficiaries, are in no hurry to reform. [ 14 ] The third step in this argument purportedly shows that justifications of restrictive immigration policies premised on ethico-political claims lose much of their force in the context of profound international inequalities and injustice. Proponents claim that regulating immigration to preserve the integrity of the political community is a legitimate goal only if duties of international distributive justice are satisfied (Tan 2004, 126, referring to Tamir 1992, 161). The argument’s upshot is that “[r]ich Northern states have a double moral obligation to seriously fight global poverty and to let more people in” (Bader 1997, 31).

Most supporters and critics of (more) open borders agree that liberal democratic states have a moral status and are worth preserving. [ 15 ] They disagree over what exactly is worthy of protection and how much weight should be given to securing their integrity (however it is defined) relative to duties of international justice.

The division of the world into states is arguably justifiable on functional grounds, to the extent that states appear as “first approximations of optimal units for allocating and producing the world’s resources” (Coleman and Harding 1995, 38). If we think that states matter simply as local units of efficient production and distribution, then this would be the main consideration when evaluating immigration policies. Public order arguments would still matter, likewise claims pertaining to a society’s basic capacity to secure its material reproduction, but not arguments relating to its cultural integrity or way of life. Unless, of course, the capacity of states to act as efficient units of production and distribution is linked to their being distinctive political communities with a particular culture of shared meanings worth preserving.

Some forty years ago, Michael Walzer defended this view, based on the idea that “distributive justice presupposes a bounded world within which distribution takes place” (Walzer 1983, 31). Since the goods to be divided, exchanged and shared among individuals have social meanings that are specific to particular communities, it is only within their boundaries that conflict can be resolved and distributive schemes judged either just or unjust. The crucial assumption here is that the “political community is probably the closest we can come to a world of common meanings. Language, history, and culture come together […] to produce a collective consciousness” (Walzer 1983, 28). Politics itself, moreover, as a set of practices and institutions that shape the form and outcome that distributive conflicts take, “establishes its own bonds of commonality” (Walzer 1983, 29). To reject political communities’ right to distribute the good of membership is to undermine their capacity to preserve their integrity as “communities of character”. It is to condemn them to become nothing more than neighbourhoods, random associations lacking any legally enforceable admissions policies. The probable result of the free movement of individuals would be “casual aggregates” devoid of any internal cohesion and incapable of being a source of patriotic sentiments and solidarity. In a world of neighbourhoods, membership would become meaningless. The upshot is that the political community’s right to regulate admission should be recognized to secure its cultural, economic and political integrity.

Walzer’s position, notably his choice of analogies, has been extensively discussed. [ 16 ] His assumption that sovereign states constitute communities of shared meanings appears particularly shaky. Most often, existing states incorporate various political communities that are themselves internally pluralistic: linguistically, culturally and ideologically. One would be hard pressed to identify the community whose integrity is at stake. Indeed, few states correspond to the picture Walzer envisages as the appropriate context for distributive justice.

Because it is premised on a thinner conception of the political community, liberal nationalists may be able to offer a similar account of the state’s right to control its borders that may be less vulnerable to this kind of criticism. David Miller, for instance, argues that liberal democratic states “require a common public culture that in part constitutes the political identity of their members, and that serves valuable functions in supporting democracy and other social goals” (Miller 2014, 369). A society’s public culture provides its citizens, their diverse identities and ways of life notwithstanding (i.e. what Miller calls their private culture), with shared reference points (e.g. an overlapping set of beliefs about the kind of political system they want to live in, social norms about how to behave in the public space, etc.) that enable them to confront their society’s challenges. The public culture also acts as a bridge between the society’s past, its present, and its future. It plays a key role in securing the kind of trust between citizens and towards political institutions that is essential for the provision of public goods and for supporting policies involving economic redistribution. “Where trust is lacking”, writes Miller, “deliberation is likely to be replaced by self-interested bargaining on the part of each group, where the outcome reflects the balance of power between them” (Miller 2016, 64). Citizens of liberal democratic states have a legitimate interest in preserving their public culture. This includes the capacity to decide the scale and type of immigration allowed in the country in order to regulate the changes that the common public culture may experience because of new arrivals. According to Miller, the concern here is not about diversity, but “about areas in which private culture and public culture intersect – in which it becomes harder to reach agreement on public matters because people approach them on the basis of conflicting and privately held beliefs and values” (Miller 2016, 68).

Miller’s argument has been widely discussed over the years (Carens 2013; Stilz 2022; Wellman 2008, 2022). His account of the common public culture has been described as unstable and unrealistic. Anna Stilz claims, for instance, that the internal diversity of liberal states is such “that it may be impossible to pick out any single ‘common public culture’, a[ny] set of understandings about how their collective life should be led” (Stilz 2022, 13).

Some theorists try to defend the state’s right to self-determination – including the right to restrict immigration – without making any reference to the (common public) culture of the political community. Chritopher Heath Wellman has argued that this can be done by focusing on freedom of association as an integral part of self-determination (Wellman 2008, 2012; see also Ferracioli 2022). Since “freedom of association includes a right to reject a potential association and (often) a right to dissociate” (Wellman 2008, 110), liberal democratic states – or legitimate states – have a presumptive right to exclude immigrants: “it does not matter how culturally diverse or homogeneous a country’s citizens are; if they are collectively able and willing to perform the requisite political function of adequately protecting and preserving human rights, then they are entitled to political self-determination” (Wellman 2012, 52). The presumptive right to exclude does not cancel duties of international distributive justice. It means that “whatever duties of distributive justice wealthy states have to those abroad, they need not be paid in the currency of open borders” (Wellman 2012, 66). [ 17 ]

None of the authors involved in this debate consider that the current levels of global inequality are morally acceptable or that prosperous liberal democratic states are doing enough to discharge their duties of international justice. Those who defend the state’s right to exclude, like Wellman, recognize that “affluent societies must dramatically relax their severe limits on immigration if they are unwilling to provide sufficient assistance in other ways ” (Wellman 2012, 77; see also Miller 2014, 368). As Kok-Chor Tan has remarked, “the national projects of well-off nations lose their legitimacy if these nations are not also doing their fair share as determined by their duties of justice” (Tan 2004, 129; see also Brock 2020). [ 18 ] Whether liberals should concentrate on reforming the international system or fight for both greater international distributive justice and more open borders remains open for debate. The two prescriptions are by no means incompatible: insisting on the illegitimacy of restrictive immigration policies under current conditions is also a way of putting rich countries on the spot and of prodding them to accept their moral responsibilities towards the world’s poor (Goodin 1992, 8).

Should one infer from the preceding discussion that citizenship is “hard on the outside and soft on the inside” (Bosniak 2006, 4) with the border representing a firm line between those who are part of the community of equal citizens and those who remain outside? The short answer is no. International migration produces what Bauböck calls a “mismatch between citizenship and the territorial scope of legitimate authority” with “citizens living outside the country whose government is supposed to be accountable to them and inside a country whose government is not accountable to them” (Bauböck 2008, 31). To resident aliens who live within a specific community of citizens, the border is not something they have left behind, it effectively follows them inside the state, denying them many of the rights enjoyed by full citizens or making their enjoyment less secure (Bosniak 2006).

One way to address this mismatch is to reconsider how entitlement to citizenship is determined. In a world characterized by significant levels of migration across states, birthright citizenship — acquired either through descent ( jus sanguinis ) or birth in the territory ( jus soli ) — may lead to counterintuitive results: while a regime of pure jus sanguinis systematically excludes immigrants and their children, though the latter may be born and bred in their parents’ new home, it includes descendants of expatriates who may never have set foot in their forebears’ homeland. On the other hand, a regime of jus soli may attribute citizenship to children whose birth in the territory is accidental while denying it to those children who have arrived in the country at a very young age.

The stakeholder principle (or jus nexi ) is proposed as an alternative (or a supplement) to birthright citizenship: individuals who have a “real and effective link” (Shachar 2009, 165) to the political community, or a “permanent interest in membership” (Bauböck 2008, 35) should be entitled to claim citizenship. This new criterion aims at securing citizenship for those who are truly members of the political community, in the sense that their life prospects depend on the country’s laws and policy choices.

If the stakeholder principle alleviates the mismatch, it does not question the tight association between rights, citizenship, territory, and authority. For some, it is precisely this association that should be questioned since it contradicts the increasing fluidity of the relations between individuals and polities in a globalized world. This context is thought to necessitate more than a friendly amendment to current principles of citizenship allocation: it requires the disaggregation of rights, commonly associated with citizenship, from the legal status of citizen. [ 19 ] This process is thought to have already begun in contemporary democracies since, as noted above, many of the civil and social rights associated with citizenship are now extended to all individuals residing in the state, notwithstanding their legal status. Political rights to participation should likewise be extended to resident noncitizens, and perhaps even to those “noncitizen nonresidents” who have fundamental interests that are affected by a particular state (Song 2009).

The emergence of human rights instruments at the international level has lent some credibility to the perspective of a deterritorialization of rights regimes and the possibility of securing a person’s basic rights irrespective of her formal membership status in a given polity. In this context, it is not in virtue of our (particular) citizenship that we are recognized rights, but in virtue of our (universal) personhood.