Report | Children

Student absenteeism : Who misses school and how missing school matters for performance

Report • By Emma García and Elaine Weiss • September 25, 2018

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

A broader understanding of the importance of student behaviors and school climate as drivers of academic performance and the wider acceptance that schools have a role in nurturing the “whole child” have increased attention to indicators that go beyond traditional metrics focused on proficiency in math and reading. The 2015 passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which requires states to report a nontraditional measure of student progress, has codified this understanding.

The vast majority of U.S. states have chosen to comply with ESSA by using measures associated with student absenteeism—and particularly, chronic absenteeism. This report uses data on student absenteeism to answer several questions: How much school are students missing? Which groups of students are most likely to miss school? Have these patterns changed over time? And how much does missing school affect performance?

Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in 2015 show that about one in five students missed three days of school or more in the month before they took the NAEP mathematics assessment. Students who were diagnosed with a disability, students who were eligible for free lunch, Hispanic English language learners, and Native American students were the most likely to have missed school, while Asian students were rarely absent. On average, data show children in 2015 missing fewer days than children in 2003.

Our analysis also confirms prior research that missing school hurts academic performance: Among eighth-graders, those who missed school three or more days in the month before being tested scored between 0.3 and 0.6 standard deviations lower (depending on the number of days missed) on the 2015 NAEP mathematics test than those who did not miss any school days.

Introduction and key findings

Education research has long suggested that broader indicators of student behavior, student engagement, school climate, and student well-being are associated with academic performance, educational attainment, and with the risk of dropping out. 1

One such indicator—which has recently been getting a lot of attention in the wake of the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) in 2015—is student absenteeism. Absenteeism—including chronic absenteeism—is emerging as states’ most popular metric to meet ESSA’s requirement to report a “nontraditional” 2 measure of student progress (a metric of “school quality or student success”). 3

Surprisingly, even though it is widely understood that absenteeism has a substantial impact on performance—and even though absenteeism has become a highly popular metric under ESSA—there is little guidance for how schools, districts, and states should use data about absenteeism. Few empirical sources allow researchers to describe the incidence, trends over time, and other characteristics of absenteeism that would be helpful to policymakers and educators. In particular, there is a lack of available evidence that allows researchers to examine absenteeism at an aggregate national level, or that offers a comparison across states and over time. And although most states were already gathering aggregate information on attendance (i.e., average attendance rate at the school or district level) prior to ESSA, few were looking closely into student-level attendance metrics, such as the number of days each student misses or if a student is chronically absent, and how they mattered. These limitations reduce policymakers’ ability to design interventions that might improve students’ performance on nontraditional indicators, and in turn, boost the positive influence of those indicators (or reduce their negative influence) on educational progress.

In this report, we aim to fill some of the gaps in the analysis of data surrounding absenteeism. We first summarize existing evidence on who misses school and how absenteeism matters for performance. We then analyze the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data from 2003 (the first assessment with information available for every state) and 2015 (the most recent available microdata). As part of the NAEP assessment, fourth- and eighth-graders were asked about their attendance during the month prior to taking the NAEP mathematics test. (The NAEP assessment may be administered anytime between the last week of January and the end of the first week of March, so “last month” could mean any one-month period between the first week of January and the first week of March.) Students could report that they missed no days, 1–2 days, 3–4 days, 5–10 days, or more than 10 days.

We use this information to describe how much school children are missing, on average; which groups of children miss school most often; and whether there have been any changes in these patterns between 2003 and 2015. We provide national-level estimates of the influence of missing school on performance for all students, as well as for specific groups of students (broken out by gender, race/ethnicity and language status, poverty/income status, and disability status), to detect whether absenteeism is more problematic for any of these groups. We also present evidence that higher levels of absenteeism are associated with lower levels of student performance. We focus on the characteristics and outcomes of students who missed three days of school or more in the previous month (the aggregate of those missing 3–4, 5–10, and more than 10 school days), which is our proxy for chronic absenteeism. 4 We also discuss data associated with children who had perfect attendance the previous month and those who missed more than 10 days of school (our proxy for extreme chronic absenteeism).

Given that the majority of states (36 states and the District of Columbia) are using “chronic absenteeism” as a metric in their ESSA accountability plans, understanding the drivers and characteristics of absenteeism and, thus, the policy and practice implications, is more important than ever (Education Week 2017). Indeed, if absenteeism is to become a useful additional indicator of learning and help guide effective policy interventions, it is necessary to determine who experiences higher rates of absenteeism; why students miss school days; and how absenteeism affects student performance (after controlling for factors associated with absenteeism that also influence performance).

Major findings include:

One in five eighth-graders was chronically absent. Typically, in 2015, about one in five eighth-graders (19.2 percent) missed school three days or more in the month before the NAEP assessment and would be at risk of being chronically absent if that pattern were sustained over the school year.

- About 13 percent missed 3–4 days of school in 2015; about 5 percent missed 5–10 days of school (between a quarter and a half of the month); and a small minority, less than 2 percent, missed more than 10 days of school, or half or more of the school days that month.

- We find no significant differences in rates of absenteeism and chronic absenteeism by grade (similar shares of fourth-graders and eighth-graders were absent), and the patterns were relatively stable between 2003 and 2015.

- While, on average, there was no significant change in absenteeism levels between 2003 and 2015, there was a significant decrease over this period in the share of students missing more than 10 days of school.

Absenteeism varied substantially among the groups we analyzed. In our analysis, we look at absenteeism by gender, race/ethnicity and language status, FRPL (free or reduced-price lunch) eligibility (our proxy for poverty status), 5 and IEP (individualized education program) status (our proxy for disability status). 6 Some groups had much higher shares of students missing school than others.

- Twenty-six percent of IEP students missed three school days or more, compared with 18.3 percent of non-IEP students.

- Looking at poverty-status groups, 23.2 percent of students eligible for free lunch, and 17.9 percent of students eligible for reduced-price lunch, missed three school days or more, compared with 15.4 percent of students who were not FRPL-eligible (that is, eligible for neither free lunch nor reduced-price lunch).

- Among students missing more than 10 days of school, the share of free-lunch-eligible students was more than twice as large as the share of non-FRPL-eligible students (2.3 percent vs. 1.1 percent). Similarly, the share of IEP students in this category was more than double the share of non-IEP students (3.2 percent vs. 1.5 percent).

- Perfect attendance rates were slightly higher among black and Hispanic non-ELL students than among white students, although all groups lagged substantially behind Asian students in this indicator.

- Hispanic ELL students and Asian ELL students were the most likely to have missed more than 10 school days, at 3.9 percent and 3.2 percent, respectively. These shares are significantly higher than the overall average rate of 1.7 percent and than the shares for their non-ELL counterparts (Hispanic non-ELL students, 1.6 percent; Asian non-ELL students, 0.6 percent).

Absenteeism varied by state. Some states had much higher absenteeism rates than others. Patterns within states remained fairly consistent over time.

- In 2015, California and Massachusetts were the states with the highest full-attendance rates: 51.1 and 51.0 percent, respectively, of their students did not miss any school days; they are closely followed by Virginia (48.4 percent) and Illinois and Indiana (48.3 percent).

- At the other end of the spectrum, Utah and Wyoming had the largest shares of students missing more than 10 days of school in the month prior to the 2015 assessment (4.6 and 3.5 percent, respectively).

- Five states and Washington, D.C., stood out for their high shares of students missing three or more days of school in 2015: in Utah, nearly two-thirds of students (63.5 percent) missed three or more days; in Alaska, nearly half (49.6 percent) did; and in the District of Columbia, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Montana, nearly three in 10 students were in this absenteeism category.

- In most states, overall absenteeism rates changed little between 2003 and 2015.

Prior research linking chronic absenteeism with lowered academic performance is confirmed by our results. As expected, and as states have long understood, missing school is negatively associated with academic performance (after controlling for factors including race, poverty status, gender, IEP status, and ELL status). As students miss school more frequently, their performance worsens.

- Overall performance gaps. The gaps in math scores between students who did not miss any school and those who missed three or more days of school varied from 0.3 standard deviations (for students who missed 3–4 days of school the month prior to when the assessment was taken) to close to two-thirds of a standard deviation (for those who missed more than 10 days of school). The gap between students who did not miss any school and those who missed just 1–2 days of school was 0.10 standard deviations, a statistically significant but relatively small difference in practice.

- For Hispanic non-ELL students, missing more than 10 days of school harmed their performance on the math assessment more strongly than for the average (0.74 standard deviations vs. 0.64 on average).

- For Asian non-ELL students, the penalty for missing school was smaller than the average (except for those missing 5–10 days).

- Missing school hindered performance similarly across the three poverty-status groups (nonpoor, somewhat poor, and poor). However, given that there are substantial differences in the frequency with which children miss school by poverty status (that is, poor students are more likely to be chronically absent than nonpoor students), absenteeism may in fact further widen income-based achievement gaps.

What do we already know about why children miss school and which children miss school? What do we add to this evidence?

Poor health, parents’ nonstandard work schedules, low socioeconomic status (SES), changes in adult household composition (e.g., adults moving into or out of the household), residential mobility, and extensive family responsibilities (e.g., children looking after siblings)—along with inadequate supports for students within the educational system (e.g., lack of adequate transportation, unsafe conditions, lack of medical services, harsh disciplinary measures, etc.)—are all associated with a greater likelihood of being absent, and particularly with being chronically absent (Ready 2010; U.S. Department of Education 2016). 8 Low-income students and families disproportionately face these challenges, and some of these challenges may be particularly acute in disadvantaged areas 9 ; residence in a disadvantaged area may therefore amplify or reinforce the distinct negative effects of absenteeism on educational outcomes for low-income students.

A detailed 2016 report by the U.S. Department of Education showed that students with disabilities were more likely to be chronically absent than students without disabilities; Native American and Pacific Islander students were more likely to be chronically absent than students of other races and ethnicities; and non-ELL students were more likely to be chronically absent than ELL students. 10 It also showed that students in high school were more likely to miss school than students in other grades, and that about 500 school districts reported that 30 percent or more of their students missed at least three weeks of school in 2013–2014 (U.S. Department of Education 2016).

Our analysis complements this evidence by adding several dimensions to the breakdown of who misses school—including absenteeism rates by poverty status and state—and by analyzing how missing school harms performance. We distinguish by the number of school days students report having missed in the month prior to the assessment (using five categories, from no days missed to more than 10 days missed over the month), 11 and we compare absenteeism rates across grades and across cohorts (between 2003 and 2015), as available in the NAEP data. 12

How much school are children missing? Are they missing more days than the previous generation?

In 2015, almost one in five, or 19.2 percent of, eighth-grade students missed three or more days of school in the month before they participated in NAEP testing. 13 About 13 percent missed 3–4 days, roughly 5 percent missed 5–10 days, and a small share—less than 2 percent—missed more than 10 days, or half or more of the instructional days that month ( Figure A , bottom panel). 14

How much school are children missing? : Share of eighth-grade students by attendance/absenteeism category, in the eighth-grade mathematics NAEP sample, 2003 and 2015

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Source: EPI analysis of National Assessment of Educational Progress microdata, 2003 and 2015

On average, however, students in 2015 did not miss any more days than students in the earlier period; by some measures, they missed less school than children in 2003 (Figure A, top panel). While the share of students with occasional absences (1–2 days) increased moderately between 2003 and 2015, the share of students who missed more than three days of school declined by roughly 3 percentage points between 2003 and 2015. This reduction was distributed about evenly (in absolute terms) across the shares of students missing 3–4, 5–10, and more than 10 days of school. But in relative terms, the reduction was much more significant in the share of students missing more than 10 days of school (the share decreased by nearly one-third). We find no significant differences by grade ( Appendix Figure A ) or by subject. Thus, we have chosen to focus our analyses below on the sample of eighth-graders taking the math assessment only.

Which groups miss school most often? Which groups suffer the most from chronic absenteeism?

Absenteeism by race/ethnicity and language status.

Hispanic ELLs and the group made up of Native Americans plus “all other races” (not white, black, Hispanic, or Asian) are the racial/ethnic and language status groups that missed school most frequently in 2015. Only 39.6 percent (Native American or other) and 41.2 percent (Hispanic ELL) did not miss any school in the month prior to the assessment (vs. 44.4 percent overall, 43.2 percent for white students, 43.5 percent for black students, and 44.1 percent for Hispanic non-ELL students; see Figure B1 ). 15

Which groups of students had the highest shares missing no school? : Share of eighth-graders with perfect attendance in the month prior to the 2015 NAEP mathematics assessment, by group

Notes: Students are grouped by gender, race/ethnicity and ELL status, FRPL eligibility, and IEP status. ELL stands for English language learner; IEP stands for individualized education program (learning plan designed for each student who is identified as having a disability); and FRPL stands for free or reduced-price lunch (federally funded meal programs for students of families meeting certain income guidelines).

Source: EPI analysis of National Assessment of Educational Progress microdata, 2015

Asian students (both non-ELL and ELL) are the least likely among all racial/ethnic student groups to be absent from school at all. Two-thirds of Asian non-ELL students and almost as many (61.6 percent of) Asian ELL students did not miss any school. Among Asian non-ELL students, only 8.8 percent missed three or more days of school: 6.1 percent missed 3–4 days (12.7 percent on average), 2.1 percent missed 5–10 days (relative to 4.8 percent for the overall average), and only 0.6 percent missed more than 10 days of school (relative to 1.7 percent for the overall average). Among Asian ELL students, the share who missed three or more days of school was 13.3 percent.

As seen in Figure B2 , the differences in absenteeism rates between white students and Hispanic non-ELL students were relatively small, when looking at the shares of students missing three or more days of school (18.3 percent and 19.1 percent, respectively). The gaps are somewhat larger for black, Native American, and Hispanic ELL students relative to white students (with shares missing three or more days at 23.0, 24.0, and 24.1 percent, respectively, relative to 18.3 percent for white students).

Which groups of students had the highest shares missing three or more days? : Share of eighth-graders missing three or more days of school in the month prior to the 2015 NAEP mathematics assessment, by group

Notes: This chart represents the aggregate of data for students who missed 3–4 days, 5–10 days, and more than 10 days of school. Students are grouped by gender, race/ethnicity and ELL status, FRPL eligibility, and IEP status. ELL stands for English language learner; IEP stands for individualized education program (learning plan designed for each student who is identified as having a disability); and FRPL stands for free or reduced-price lunch (federally funded meal programs for students of families meeting certain income guidelines).

Among students who missed a lot of school (more than 10 days), there were some more substantial differences by race and language status. About 3.9 percent of Hispanic ELL students and 3.2 percent of Asian ELL students missed more than 10 days of school, compared with 2.2 percent for Native American and other races, 2.0 percent for black students, 1.4 percent for white students, and only 0.6 percent for Asian non-ELL students (all relative to the overall average of 1.7 percent) (see Figure B3 ).

Which groups of students had the highest shares missing more than 10 days? : Share of eighth-graders missing more than 10 days of school in the month prior to the 2015 NAEP mathematics assessment, by group

Notes: Students are grouped by gender, race/ethnicity and ELL status, FRPL status, and IEP status. ELL stands for English language learner; IEP stands for individualized education program (learning plan designed for each student who is identified as having a disability); and FRPL stands for free or reduced-price lunch (federally funded meal programs for students of families meeting certain income guidelines).

Absenteeism by income status

The attendance gaps are even larger by income status than they are by race/ethnicity and language status (Figures B1–B3). Poor (free-lunch-eligible) students were 5.9 percentage points more likely to miss some school than nonpoor (non-FRPL-eligible) students, and they were 7.8 percentage points more likely to miss school three or more days (23.2 vs. 15.4 percent). 16 Among somewhat poor (reduced-price-lunch-eligible) students, 17.9 percent missed three or more days of school. The lowest-income (free-lunch-eligible) students were 4.1 percentage points more likely to miss school 3–4 days than non-FRPL-eligible students, and more than 2.4 percentage points more likely to miss school 5–10 days ( Appendix Figure B ). Finally, and most striking, free-lunch-eligible students—the most economically disadvantaged students—were more than twice as likely to be absent from school for more than 10 days as nonpoor students. In other words, they were much more likely to experience extreme chronic absenteeism. Figures B1–B3 show that the social-class gradient for the prevalence of absenteeism, proxied by eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch, is noticeable in all absenteeism categories, and especially when it comes to those students who missed the most school.

Absenteeism by disability status

Students with IEPs were by far the most likely to miss school relative to all other groups. 17 The share of IEP students missing school exceeded the share of non-IEP students missing school by 7.7 percentage points (Figure B1). More than one in four IEP students had missed school three days or more in the previous month (Figure B2). About 15.5 percent of students with IEPs missed school 3–4 days (vs. 12.4 percent among non-IEP students); 7.3 percent missed 5–10 days; and 3.2 percent missed more than 10 days of school in the month before being tested (Appendix Figure B; Figure B3).

Absenteeism by gender

The differences by gender are slightly surprising (Figures B1–B3). Boys showed a higher full-attendance rate than girls (46.6 vs. 42.1 percent did not miss any school), and boys were no more likely than girls to display extreme chronic absenteeism (1.7 percent of boys and 1.6 percent of girls missed more than 10 days of school). Boys (18.2 percent) were also slightly less likely than girls (20.2 percent) to be chronically absent (to miss three or more days of school, as per our definition).

Has there been any change over time in which groups of children are most often absent from school?

For students in several groups, absenteeism fell between 2003 and 2015 ( Figure C1 ), in keeping with the overall decline noted above. Hispanic students (both ELL and non-ELL), Asian non-ELL students, Native American and other race students, free-lunch-eligible (poor) students, reduced-priced-lunch-eligible (somewhat poor) students, non-FRPL-eligible (nonpoor) students, and IEP students were all less likely to miss school in 2015 than they were over a decade earlier. For non-IEP and white students, however, the share of students who did not miss any school days in the month prior to NAEP testing remained essentially unchanged, while it increased slightly for black students and Asian ELL students (by about 2 percentage points each).

How much have perfect attendance rates changed since 2003? : Percentage-point change in the share of eighth-graders who had perfect attendance in the month prior to the NAEP mathematics assessment, between 2003 and 2015, by group

Notes: Students are grouped by gender, race/ethnicity and ELL status, FRPL status, and IEP status. ELL stands for English language learner; IEP stands for individualized education program (learning plan designed for each student who is identified as having a disability); and FRPL stands for free or reduced-price lunch (federally funded meal programs for students of families meeting certain income guidelines).

As seen in Figure C2 , we also note across-the-board reductions in the shares of students who missed three or more days of school (with the exception of the share of Asian ELL students, which increased by 1.7 percentage points over the time studied). The largest reductions occurred for students with disabilities (IEP students), Hispanic non-ELL students, Native American students or students of other races, free-lunch-eligible students, and non-FRPL-eligible students (each of these groups experienced a reduction of at least 4.4 percentage points). 18 For all groups except Asian ELL students, the share of students missing more than 10 days of school ( Figure C3 ) also decreased (for Asian ELL students, it increased by 1.3 percentage points).

How much have rates of students missing three or more days changed since 2003? : Percentage-point change in the share of eighth-graders who were absent from school three or more days in the month prior to the NAEP mathematics assessment, between 2003 and 2015, by group

Notes: This chart represents the aggregate of data for students who missed 3–4 days, 5–10 days, and more than 10 days of school. Students are grouped by gender, race/ethnicity and ELL status, FRPL status, and IEP status. ELL stands for English language learner; IEP stands for individualized education program (learning plan designed for each student who is identified as having a disability); and FRPL stands for free or reduced-price lunch (federally funded meal programs for students of families meeting certain income guidelines).

How much have rates of students missing more than 10 days changed since 2003? : Percentage-point change in the share of eighth-graders who were absent from school more than 10 days in the month prior to the NAEP mathematics assessment, between 2003 and 2015, by group

Notes: Students are grouped by gender, race/ethnicity and ELL status, FRPL status, and IEP status. ELL stands for English language learner; IEP stands for individualized education program (learning plan designed for each student who is identified as having a disability); and FRPL stands for free or reduced-price lunch (federally funded meal programs for students of families meeting certain income guidelines).

In order to get a full understanding of these comparisons, we need to look at both the absolute and relative differences. Overall, the data presented show modest absolute differences in the shares of students who are absent (at any level) in various groups when compared with the averages for all students (Figures B1–B3 and Appendix Figure B). The differences (both absolute and relative) among student groups missing a small amount of school (1–2 days) are minimal for most groups. However, while the differences among groups are very small in absolute terms for students missing a lot of school (more than 10 days), some of the differences are very large in relative terms. (And, taking into account the censoring problem mentioned earlier, they could potentially be even larger.)

The fact that the absolute differences are small is in marked contrast to differences seen in many other education indicators of outcomes and inputs, which tend to be much larger by race and income divisions (Carnoy and García 2017; García and Weiss 2017). Nevertheless, both the absolute and relative differences we find are revealing and important, and they add to the set of opportunity gaps that harm students’ performance.

Is absenteeism particularly high in certain states?

Share of students absent from school, by state and by number of days missed, 2015.

Notes: Based on the number of days eighth-graders in each state reported having missed in the month prior to the NAEP mathematics assessment. “Three or more days” represents the aggregate of data for students who missed 3–4 days, 5–10 days, and more than 10 days of school.

Over the 2003–2015 period, 22 states saw their share of students with perfect attendance grow. The number drops to 15 if we count only states in which the share of students not missing any school increased by more than 1 percentage point. In almost every state (44 states), the share of students who missed more than 10 school days decreased, and in 41 states, the share of students who missed three or more days of school also dropped, though it increased in the other 10. 19 Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nevada, Indiana, New Hampshire, and California were the states in which these shares decreased the most, by more than 6 percentage points, while Utah, Alaska, and North Dakota were the states where this indicator (three or more days missed) showed the worst trajectory over time (that is, the largest increases in chronic absenteeism).

Is absenteeism a problem for student performance?

Previous research has focused mainly on two groups of students when estimating how much absenteeism influences performance: students who are chronically absent and all other students. This prior research has concluded that students who are chronically absent are at serious risk of falling behind in school, having lower grades and test scores, having behavioral issues, and, ultimately, dropping out (U.S. Department of Education 2016; see summary in Gottfried and Ehrlich 2018). Our analysis allows for a closer examination of the relationship between absenteeism and performance, as we look at the impact of absenteeism on student performance at five levels of absenteeism. This design allows us to test not only whether different levels of absenteeism have different impacts on performance (as measured by NAEP test scores), but also to identify the point at which the impact of absenteeism on performance becomes a concern. Specifically, we look at the relationship between student absenteeism and mathematics performance among eighth-graders at various numbers of school days missed. 20

The results shown in Figure D and Appendix Table 1 are obtained from regressions that assess the influence of absenteeism and other individual- and school-level determinants of performance. The latter include students’ race/ethnicity, gender, poverty status, ELL status, and IEP status, as well as the racial/ethnic composition of the school they attend and the share of students in their school who are eligible for FRPL (a proxy for the SES composition of the school). Our results thus identify the distinct association between absenteeism and performance, net of other factors that are known to influence performance. 21

In general, the more frequently children missed school, the worse their performance. Relative to students who didn’t miss any school, those who missed some school (1–2 school days) accrued, on average, an educationally small, though statistically significant, disadvantage of about 0.10 standard deviations (SD) in math scores (Figure D and Appendix Table 1, first row). Students who missed more school experienced much larger declines in performance. Those who missed 3–4 days or 5–10 days scored, respectively, 0.29 and 0.39 standard deviations below students who missed no school. As expected, the harm to performance was much greater for students who were absent half or more of the month. Students who missed more than 10 days of school scored nearly two-thirds (0.64) of a standard deviation below students who did not miss any school. All of the gaps are statistically significant, and together they identify a structural source of academic disadvantage.

The more frequently students miss school, the worse their performance : Performance disadvantage experienced by eighth-graders on the 2015 NAEP mathematics assessment, by number of school days missed in the month prior to the assessment, relative to students with perfect attendance in the prior month (standard deviations)

Notes: Estimates are obtained after controlling for race/ethnicity, poverty status, gender, IEP status, and ELL status; for the racial/ethnic composition of the student’s school; and for the share of students in the school who are eligible for FRPL (a proxy for school socioeconomic composition). All estimates are statistically significant at p < 0.01.

The results show that missing school has a negative effect on performance regardless of how many days are missed, with a moderate dent in performance for those missing 1–2 days and a troubling decline in performance for students who missed three or more days that becomes steeper as the number of missed days rises to 10 and beyond. The point at which the impact of absenteeism on performance becomes a concern, therefore, is when students miss any amount of school (vs. having perfect attendance); the level of concern grows as the number of missed days increases.

Gaps in performance associated with absenteeism are similar across all races/ethnicities, between boys and girls, between FRPL-eligible and noneligible students, and between students with and without IEPs. For example, relative to nonpoor (non-FRPL-eligible) students who did not miss any school, nonpoor children who missed school accrued a disadvantage of -0.09 SD (1–2 school days missed), -0.27 SD (3–4 school days missed), -0.36 SD (5–10 school days missed), and -0.63 SD (more than 10 days missed). For students eligible for reduced-price lunch (somewhat poor students) who missed school, compared with students eligible for reduced-price lunch who did not miss any school, the gaps are -0.16 SD (1–2 school days missed), -0.33 SD (3–4 school days missed), -0.45 SD (5–10 school days missed), and -0.76 SD (more than 10 days missed). For free-lunch-eligible (poor) students who missed school, relative to poor students who do not miss any school, the gaps are -0.11 SD (1–2 school days missed), -0.29 SD (3–4 school days missed), -0.39 SD (5–10 school days missed), and -0.63 SD (more than 10 days missed). By IEP status, relative to non-IEP students who did not miss any school, non-IEP students who missed school accrued a disadvantage of -0.11 SD (1–2 school days missed), -0.30 SD (3–4 school days missed), -0.40 SD (5–10 school days missed), and -0.66 SD (more than 10 days missed). And relative to IEP students who did not miss any school, IEP students who missed school accrued a disadvantage of -0.05 SD (1–2 school days missed), -0.21 SD (3–4 school days missed), -0.31 SD (5–10 school days missed), and -0.52 SD (more than 10 days missed). (For gaps by gender and by race/ethnicity, see Appendix Table 1).

Importantly, though the gradients of the influence of absenteeism on performance by race, poverty status, gender, and IEP status (Appendix Table 1) are generally similar to the gradients in the overall relationship between absenteeism and performance for all students, this does not mean that all groups of students are similarly disadvantaged when it comes to the full influence of absenteeism on performance. The overall performance disadvantage faced by any given group is influenced by multiple factors, including the size of the group’s gaps at each level of absenteeism (Appendix Table 1), the group’s rates of absenteeism (Figure B), and the relative performance of the group with respect to the other groups (Carnoy and García 2017). The total gap that results from adding these factors can thus become substantial.

To illustrate this, we look at Hispanic ELL, Asian non-ELL, Asian ELL, and FRPL-eligible students. The additional penalty associated with higher levels of absenteeism is smaller than average for Hispanic ELL students experiencing extreme chronic absenteeism; however, their performance is the lowest among all groups (Carnoy and García 2017) and they have among the highest absenteeism rates.

The absenteeism penalty is also smaller than average for Asian non-ELL students (except at 5-10 days); however, in contrast with the previous example, their performance is the highest among all groups (Carnoy and García 2017) and their absenteeism rate is the lowest.

The absenteeism penalty for Asian ELL students is larger than average, and the gradient is steeper. 22 Asian ELL students also have lower performance than most other groups (Carnoy and García 2017).

Finally, although there is essentially no difference in the absenteeism–performance relationship by FRPL eligibility, the higher rates of absenteeism (at every level) for students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, relative to nonpoor (FRPL-ineligible) students, put low-income students at a greater risk of diminished performance due to absenteeism than their higher-income peers, widening the performance gap between these two groups.

Conclusions

Student absenteeism is a puzzle composed of multiple pieces that has a significant influence on education outcomes, including graduation and the probability of dropping out. The factors that contribute to it are complex and multifaceted, and likely vary from one school setting, district, and state to another. This analysis aims to shed additional light on some key features of absenteeism, including which students tend to miss school, how those profiles have changed over time, and how much missing school matters for performance.

Our results indicate that absenteeism rates were high and persistent over the period examined (2003–2015), although they did decrease modestly for most groups and in most states. Unlike findings for other factors that drive achievement gaps—from preschool attendance to economic and racial school segregation to unequal funding (Carnoy and García 2017; García 2015; García and Weiss 2017)—our findings here seem to show some positive news for black and Hispanic students: these students had slightly higher perfect attendance rates than their white peers; in addition, their perfect attendance rates have increased over time at least as much as rates for white students. But with respect to the absenteeism rates that matter the most (three or more days of school missed, and more than 10 days of school missed), black and Hispanic students still did worse (just as is the case with other opportunity gaps faced by these students). Particularly worrisome is the high share of Hispanic ELL students who missed more than 10 school days—nearly 4 percent. Combined with the share of Hispanic ELL students who missed 5–10 school days (nearly 6 percent), this suggests that one in 10 children in this group would miss school for at least a quarter of the instructional time.

The advantages that Asian students enjoy relative to white students and other racial/ethnic groups in academic settings is also confirmed here (especially among Asian non-ELL students): the Asian students in the sample missed the least school. And there is a substantial difference in rates of absenteeism by poverty (FRPL) and disability (IEP) status, with the difference growing as the number of school days missed increases. Students who were eligible for free lunch were twice as likely as nonpoor (FRPL-ineligible) students to be absent more than 10 days, and students with IEPs were more likely than any other group to be absent (one or more days, that is, to not have perfect attendance).

Missing school has a distinct negative influence on performance, even after the potential mediating influence of other factors is taken into account, and this is true at all rates of absenteeism. The bottom line is that the more days of school a student misses, the poorer his or her performance will be, irrespective of gender, race, ethnicity, disability, or poverty status.

These findings help establish the basis for an expanded analysis of absenteeism along two main, and related, lines of inquiry. One, given the marked and persistent patterns of school absenteeism, it is important to continue to explore and document why children miss school—to identify the full set of factors inside and outside of schools that influence absenteeism. Knowing whether (or to what degree) those absences are attributable to family circumstances, health, school-related factors, weather, or other factors, is critical to effectively designing and implementing policies and practices to reduce absenteeism, especially among students who chronically miss school. The second line of research could look at variations in the prevalence and influence of absenteeism among the states, and any changes over time in absenteeism rates within each state, to assess whether state differences in policy are reducing absenteeism and mitigating its negative impacts. For example, in recent years, Connecticut has made reducing absenteeism, especially chronic absenteeism, a top education policy priority, and has developed a set of strategies and resources that could be relevant to other states as well, especially as they begin to assess and respond to absenteeism as part of their ESSA plans. 23

The analyses in this report confirm the importance of looking closely into “other” education data, above and beyond performance (test scores) and individual and school demographic characteristics. The move in education policy toward widening accountability indicators to indicators of school quality, such as absenteeism, is important and useful, and could be expanded to include other similar data. Indicators of bullying, school safety, student tardiness, truancy, level of parental involvement, and other factors that are relevant to school climate, well-being, and student performance would also merit attention.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge John Schmitt and Richard Rothstein for their insightful comments and advice on earlier drafts of the paper. We are also grateful to Krista Faries for editing this report, to Lora Engdahl for her help structuring it, and to Julia Wolfe for her work preparing the tables and figures included in the appendix. Finally, we appreciate the assistance of communications staff at the Economic Policy Institute who helped to disseminate the study, especially Dan Crawford and Kayla Blado.

About the authors

Emma García is an education economist at the Economic Policy Institute, where she specializes in the economics of education and education policy. Her areas of research include analysis of the production of education, returns to education, program evaluation, international comparative education, human development, and cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analysis in education. Prior to joining EPI, García was a researcher at the Center for Benefit-Cost Studies of Education, the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education, and the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University, and did consulting work for the National Institute for Early Education Research, MDRC, and the Inter-American Development Bank. García has a Ph.D. in economics and education from Teachers College, Columbia University.

Elaine Weiss served as the national coordinator for the Broader, Bolder Approach to Education (BBA) from 2011 to 2017, in which capacity she worked with four co-chairs, a high-level task force, and multiple coalition partners to promote a comprehensive, evidence-based set of policies to allow all children to thrive. She is currently working on a book drawing on her BBA case studies, co-authored with Paul Reville, to be published by the Harvard Education Press. Weiss came to BBA from the Pew Charitable Trusts, where she served as project manager for Pew’s Partnership for America’s Economic Success campaign. Weiss was previously a member of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s task force on child abuse and served as volunteer counsel for clients at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless. She holds a Ph.D. in public policy from the George Washington University and a J.D. from Harvard Law School.

Appendix figures and tables

Are there significant differences in student absenteeism rates across grades and over time : shares of fourth-graders and eighth-graders who missed school no days, 1–2 days, 3–4 days, 5–10 days, and more than 10 days in the month before the naep mathematics assessment, 2003 and 2015, detailed absenteeism rates by group : shares of eighth-graders in each group who missed school no days, 1–2 days, 3–4 days, 5–10 days, and more than 10 days in the month before the naep mathematics assessment, 2015, the influence of absenteeism on eighth-graders' math achievement : performance disadvantage experienced by eighth-graders on the 2015 naep mathematics assessment, by group and by number of days missed in the month prior to the assessment, relative to students in the same group with perfect attendance in the prior month (standard deviations).

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1

Notes: Students are grouped by gender, race/ethnicity and ELL status, FRPL eligibility, and IEP status. ELL stands for English language learner; IEP stands for individualized education program (learning plan designed for each student who is identified as having a disability); and FRPL stands for free or reduced-price lunch (federally funded meal programs for students of families meeting certain income guidelines). Estimates for the “All students” sample are obtained after controlling for race/ethnicity, poverty status, gender, IEP status, and ELL status; for the racial/ethnic composition of the student’s school; and for the share of students in the school who are eligible for FRPL (a proxy for school socioeconomic composition). For each group, controls that are not used to identify the group are included (for example, for black students, estimates control for poverty status, gender, IEP status, and ELL status; for the racial/ethnic composition of the student’s school; and for the share of students in the school who are eligible for FRPL; etc.)

1. See García 2014 and García and Weiss 2016.

2. See ESSA 2015. According to ESSA, this nontraditional indicator should measure “school quality or student success.” (The other indicators at elementary/middle school include measures of academic achievement, e.g., performance or proficiency in reading/language arts and math; academic progress, or student growth; and progress in achieving English language proficiency.)

3. Thirty-six states and the District of Columbia have included student absenteeism as an accountability metric in their states’ ESSA plans. This metric meets all the requirements (as outlined in ESSA) to be considered a measure of school quality or student success (valid, reliable, calculated the same for all schools and school districts across the state, can be disaggregated by student subpopulation, is a proven indicator of school quality, and is a proven indicator of student success; see Education Week 2017). See FutureEd 2017 for differences among the states’ ESSA plans. See the web page “ ESSA Consolidated State Plans ” (on the Department of Education website) for the most up-to-date information on the status and content of the state plans.

4. There is no precise official definition that identifies how many missed days constitutes chronic absenteeism on a monthly basis. Definitions of chronic absenteeism are typically based on the number of days missed over an entire school year, and even these definitions vary. For the Department of Education, chronically absent students are those who “miss at least 15 days of school in a year” (U.S. Department of Education 2016). Elsewhere, chronic absenteeism is frequently defined as missing 10 percent or more of the total number of days the student is enrolled in school, or a month or more of school, in the previous year (Ehrlich et al. 2013; Balfanz and Byrnes 2012). Given that the school year can range in length from 180 to 220 days, and given that there are about 20–22 instructional days in a month of school, these latter two definitions imply that a student is chronically absent if he or she misses between 18 and 22 days per year (depending on the length of the school year) or more, or between 2.0 and about 2.5 days (or more) per month on average (assuming a nine-month school year). In our analysis, we define students as being chronically absent if they have missed three or more days of school in the last month (the aggregate of students missing “3–4,” “5–10,” or “more than 10 days”), and as experiencing extreme chronic absenteeism if they have missed “more than 10 days” of school in the last month. These categories are not directly comparable to categories used in studies of absenteeism on a per-year basis or that use alternative definitions or thresholds. We purposely analyze data for each of these “days absent” groups separately to identify their distinct characteristics and the influence of those differences on performance. (Appendix Figure B and Appendix Table 1 provide separate results for each of the absenteeism categories.)

5. In our analysis, we define “poor” students as those who are eligible for free lunch; we define “somewhat poor” students as those who are eligible for reduced-price lunch; and we define “nonpoor” students as those who are not eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. We use “poverty status,” “income status,” “socioeconomic status” (“SES”), and “social class” interchangeably throughout our analysis. We use the free or reduced-price lunch status classification as a metric for individual poverty, and we use the proportion of students who are eligible for FRPL as a metric for school poverty (in our regression controls; see Figure D). The limitations of these variables to measure economic status are discussed in depth in Michelmore and Dynarski’s (2016) study. FRPL statuses are nevertheless valid and widely used proxies of low(er) SES, and students’ test scores are likely to reflect such disadvantage (Carnoy and García 2017).

6. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), an IEP must be designed for each student with a disability. The IEP “guides the delivery of special education supports and services for the student” (U.S. Department of Education 2000). For more information about IDEA, see U.S. Department of Education n.d.

7. Students are grouped by gender, race/ethnicity and ELL status, FRPL eligibility, and IEP status.

8. The U.S. Department of Education (2016) defines “chronically absent” as “missing at least 15 days of school in a year.” Ready (2010) explains the difference between legitimate or illegitimate absences, which may respond to different circumstances and behaviors. Ready’s findings, pertaining to children at the beginning of school, indicate that, relative to high-SES students, low-SES children with good attendance rates experienced greater gains in literacy skills during kindergarten and first grade, narrowing the starting gaps with their high-SES peers. No differences in math skills gains were detected in kindergarten.

9. U.S. Department of Education 2016. This report uses data from the Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection 2013–2014.

10. The analysis finds no differences in absenteeism by gender. It is notable that the Department of Education report finds that ELL students have lower absenteeism rates than their non-ELL peers, given that we find (as described later in the report) that Asian ELL students have higher absenteeism rates than Asian non-ELL students and that Hispanic ELL students have higher absenteeism rates than Hispanic non-ELL students. It is important to note, however, that the data the Department of Education analyze compared all ELL students to all non-ELL students (not only Asian and Hispanic students separated out by ELL status), and thus our estimates are not directly comparable.

11. Children in the fourth and eighth grades were asked, “How many days were you absent from school in the last month?” The possible answers are: none, 1–2 days, 3–4 days, 5–10 days, and more than 10 days. An important caveat concerning this indicator and results based on its utilization is that there is a potential inherent censoring problem: Children who are more likely to miss school are also likely to miss the assessment. In addition, some students may be inclined to underreport the number of days that they missed school, in an effort to be viewed more favorably (in social science research, this may introduce a source of response-bias referred to as “social desirability bias”). Although we do not have any way to ascertain the extent to which these might be problems in the NAEP data and for this question in particular, it is important to read our results and findings as a potential underestimate of what the rates of missingness are, as well as what their influence on performance is.

12. One reason to look at different grades is to explore the potential connection between early absenteeism and later absenteeism. Ideally, we would be able to include data on absenteeism from earlier grades in students’ academic careers since, as Nai-Lin Chang, Sundius, and Wiener (2017) explain, attendance habits are developed early and often set the stage for attendance patterns later on. These authors argue that detecting absenteeism early on can improve pre-K to K transitions, especially for low-income children, children with special needs, or children who experience other challenges at home; these are the students who most need the social, emotional, and academic supports that schools provide and whose skills are most likely to be negatively influenced by missing school. Gottfried (2014) finds reduced reading and math achievement outcomes, and lower educational and social engagement, among kindergartners who are chronically absent. Even though we do not have information on students’ attendance patterns at the earliest grades, looking at patterns in the fourth and eighth grades can be illuminating.

13. Students are excluded from our analyses if their absenteeism information and/or basic descriptive information (gender, race/ethnicity, poverty status, and IEP) are missing.

14. All categories combined, we note that in 2015, 49.5 percent of fourth-graders and 55.6 percent of eighth-graders missed at least one day of school in the month prior. Just over 30 percent of fourth-graders and 36.4 percent of eighth-graders missed 1–2 days of school during the month.

15. In the sample, 52.1 percent of students are white, 14.9 percent black, 4.5 percent Hispanic ELL, 19.4 percent Hispanic non-ELL, less than 1 percent Asian ELL, 4.7 percent Asian non-ELL, and 3.8 percent Native American or other.

16. Of the students in the sample, 47.8 percent are not eligible for FRPL, 5.2 percent are eligible for reduced-price lunch, and 47.0 percent are eligible for free lunch.

17. In the 2015 eighth-grade mathematics sample, 10.8 percent of students had an IEP.

18. For students who were eligible for reduced-price lunch (somewhat poor students), shares of students absent three or more days also decreased, but more modestly, by 3.3 percentage points.

19. Number of states is out of 51; the District of Columbia is included in the state data.

20. The results discussed below cannot be interpreted as causal, strictly speaking. They are obtained using regression models with controls for the relationship between performance and absenteeism (estimates are net of individual, home, and school factors known to influence performance and are potential sources of selection). However, the literature acknowledges a causal relationship between (high-quality) instructional time and performance, in discussions about the length of the school day (Kidronl and Lindsay 2014; Jin Jez and Wassmer 2013; among others) and the dip in performance children experience after being out of school for the summer (Peterson 2013, among others). These findings could be extrapolable to our absenteeism framework and support a more causal interpretation of the findings of this paper.

21. Observations with full information are used in the regressions. The absenteeism–performance relationship is only somewhat sensitive to including traditional covariates in the regression (not shown in the tables; results available upon request). The influence of absenteeism on performance is distinct and is not due to any mediating effect of the covariates that determine education performance.

22. Asian ELL students who miss more than 10 days of school are very far behind Asian ELL students with perfect attendance, with a gap of more than a standard deviation. This result needs to be interpreted with caution, however, as it is based on a very small fraction of students for whom selection may be a concern, too.

23. The data used in our analysis are for years prior to the implementation of measures intended to tackle absenteeism. See Education Week 2017. Data for future (or more recent) years will be required to analyze whether Connecticut’s policies have had an effect on absenteeism rates in the state.

Balfanz, Robert, and Vaughan Byrnes. 2012. The Importance of Being in School: A Report on Absenteeism in the Nation’s Public Schools . Johns Hopkins University Center for Social Organization of Schools, May 2012.

Carnoy, Martin, and Emma García. 2017. Five Key Trends in U.S. Student Performance: Progress by Blacks and Hispanics, the Takeoff of Asians, the Stall of Non-English Speakers, the Persistence of Socioeconomic Gaps, and the Damaging Effect of Highly Segregated Schools . Economic Policy Institute, January 2017.

Education Week. 2017. School Accountability, School Quality and Absenteeism under ESSA (Expert Presenters: Hedy Chang and Charlene Russell-Tucker) (webinar).

Ehrlich, Stacy B., Julia A. Gwynne, Amber Stitziel Pareja, and Elaine M. Allensworth with Paul Moore, Sanja Jagesic, and Elizabeth Sorice. 2013. Preschool Attendance in Chicago Public Schools: Relationships with Learning Outcomes and Reasons for Absences . The University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research, September 2013.

ESSA. 2015. Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 , Pub. L. No. 114-95 § 114 Stat. 1177 (2015–2016).

FutureEd. 2017. Chronic Absenteeism and the Fifth Indicator in State ESSA Plans . Georgetown University.

García, Emma. 2014. The Need to Address Noncognitive Skills in the Education Policy Agenda . Economic Policy Institute, December 2014.

García, Emma. 2015. Inequalities at the Starting Gate: Cognitive and Noncognitive Skills Gaps between 2010–2011 Kindergarten Classmates . Economic Policy Institute, June 2015.

García, Emma, and Elaine Weiss. 2016. Making Whole-Child Education the Norm. How Research and Policy Initiatives Can Make Social and Emotional Skills a Focal Point of Children’s Education . Economic Policy Institute, August 2016.

García, Emma, and Elaine Weiss. 2017. Education Inequalities at the School Starting Gate: Gaps, Trends, and Strategies to Address Them . Economic Policy Institute, September 2017.

Gottfried, Michael A. 2014. “Chronic Absenteeism and Its Effects on Students’ Academic and Socioemotional Outcomes.” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk 19, no. 2: 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2014.962696 .

Gottfried, Michael A., and Stacy B. Ehrlich. 2018. “Introduction to the Special Issue: Combating Chronic Absence.” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk 23, no. 1–2: 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2018.1439753 .

Jin Jez, Su, and Robert W. Wassmer. 2013. “The Impact of Learning Time on Academic Achievement.” Education and Urban Society 47, no. 3: 284–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124513495275 .

Kidronl, Yael, and Jim Lindsay. 2014. The Effects of Increased Learning Time on Student Academic and Nonacademic Outcomes: Findings from a Meta-Analytic Review . REL 2014-015. Regional Educational Laboratory Appalachia.

Michelmore, K., and S. Dynarski. 2016. The Gap within the Gap: Using Longitudinal Data to Understand Income Differences in Student Achievement . National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 22474.

Nai-Lin Chang, Hedy, Jane Sundius, and Louise Wiener. 2017. “ Using ESSA to Tackle Chronic Absence from Pre-K to K–12 ” (blog post). National Institute for Early Education Research website, May 23, 2017.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Various years. NAEP microdata (unpublished data).

Peterson, T.K., ed. 2013. Expanding Minds and Opportunities: Leveraging the Power of Afterschool and Summer Learning for Student Success . Washington, D.C.: Collaborative Communications Group.

Ready, Douglas D. 2010. “Socioeconomic Disadvantage, School Attendance, and Early Cognitive Development: The Differential Effects of School Exposure.” Sociology of Education 83, no. 4: 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040710383520 .

U.S. Department of Education. 2000. A Guide to the Individualized Education Program . Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, July 2000.

U.S. Department of Education. 2016. Chronic Absenteeism in the Nation’s Schools: An Unprecedented Look at a Hidden Educational Crisis (online fact sheet).

U.S. Department of Education. n.d. “ About IDEA ” (webpage). IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) website . Accessed September 19, 2018.

See related work on Student achievement | Disability | Program on Race, Ethnicity and the Economy (PREE) | Education | Poverty | Children

See more work by Emma García and Elaine Weiss

Sign up to stay informed

New research, insightful graphics, and event invites in your inbox every week.

See related work on Student achievement , Disability , Program on Race, Ethnicity and the Economy (PREE) , Education , Poverty , and Children

Track EPI on Twitter

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, school attendance and school absenteeism: a primer for the past, present, and theory of change for the future.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV, United States

- 2 Child Study Center, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

- 3 Department of Developmental Psychology and Teaching, University of Alicante, San Vicente del Raspeig, Alicante, Spain

- 4 Research Group TOR, Department of Sociology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Research Foundation Flanders, Brussels, Belgium

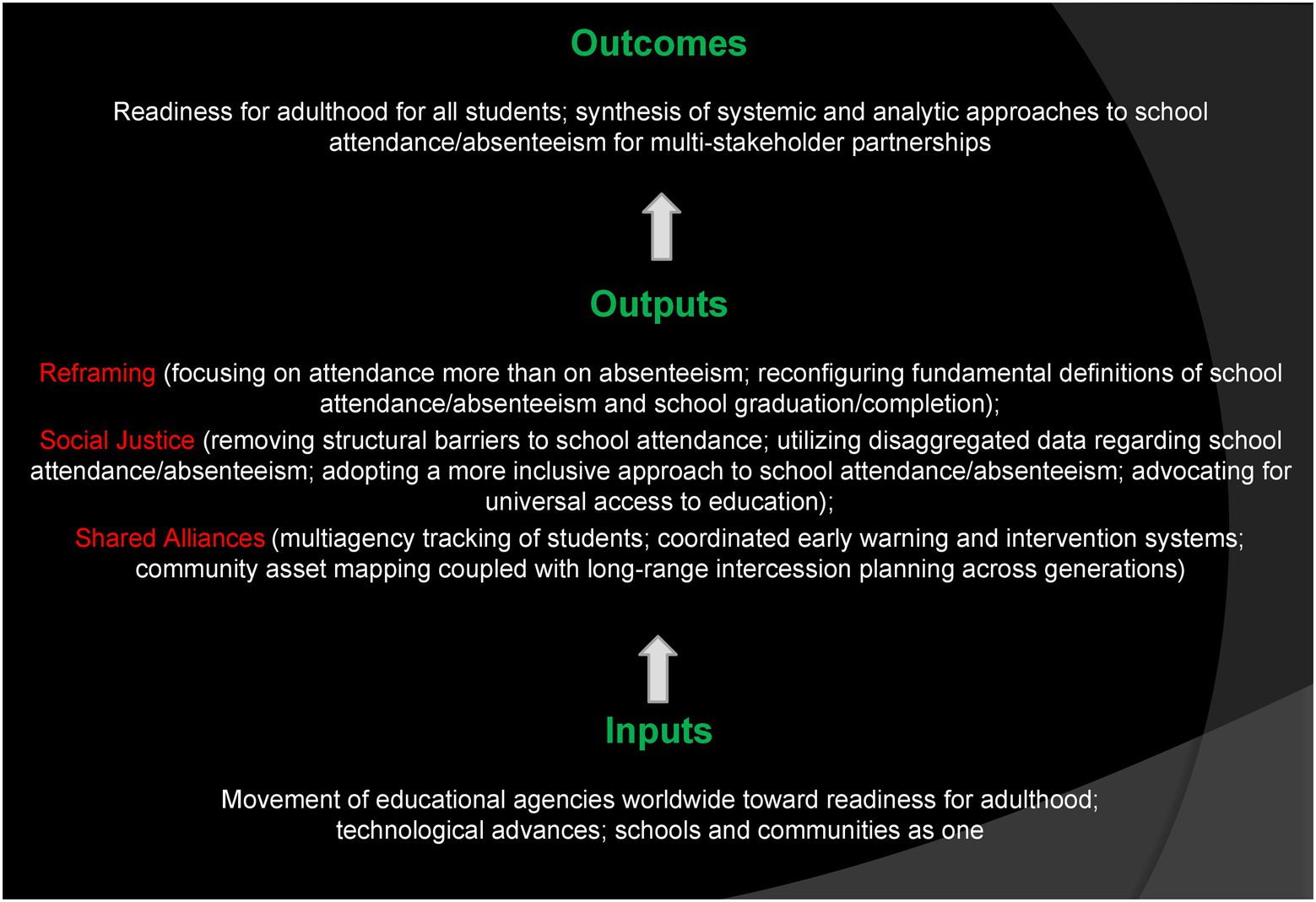

School attendance and school absenteeism have been studied for over a century, leading to a rich and vast literature base. At the same time, powerful demographic, climate, social justice/equity, and technological/globalization forces are compelling disparate stakeholders worldwide to quickly adapt to rapidly changing conditions and to consider new visions of child education for the next century. These overarching forces are utilized within a theory of change approach to help develop such a vision of school attendance/absenteeism for this era. This approach adopts key long-range outcomes (readiness for adulthood for all students; synthesized systemic and analytic approaches to school attendance/absenteeism) derived from thematic outputs (reframing, social justice, and shared alliances) that are themselves derived from contemporary inputs (movement of educational agencies worldwide toward readiness for adulthood, technological advances, schools, and communities as one). As with theory of change approaches, the purpose of this discourse is not to provide a roadmap but rather a compass to develop multi-stakeholder partnerships that can leverage shared resources and expertise to achieve a final mutual goal.

Introduction

School attendance and school absenteeism were one of the first areas of study for emerging disciplines such as education, psychology, and criminal justice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. With the advent of the labor rights movement, new employment laws, and the needs for an educated workforce and greater social order, children were increasingly moved from industrial and agricultural settings to more formalized school settings ( Rury and Tamura, 2019 ). School absenteeism thus became viewed as a legal as well as a societal problem in need of remediation, with a concurrent focus on illegal truancy as well as delinquency as a primary cause ( Williams, 1927 ; Kirkpatrick and Lodge, 1935 ; Gleeson, 1992 ). Around the mid-20th century, however, psychological approaches focused on other possible causal mechanisms of school absenteeism such as child fear/anxiety, problematic separation from caregivers, family dysfunction, and proximity to deviant peers (e.g., Johnson et al., 1941 ; Waldfogel et al., 1957 ; Kennedy, 1965 ). Many of these approaches centered on students and their families, a predominant focus of many professionals even today. Only later in the 20th century, and especially following the civil rights movement of the 1960s as well as a revival of Marxist theory via the emergence of social stratification research, did researchers and other stakeholders more intensely examine broader contexts of school absenteeism that included the school environment, the surrounding community, and economic, cultural, political, and other macro influences ( Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977 ; Willis, 1977 ; Weinberg, 1991 ; Sleeter, 2014 ).

Today, the study of school attendance/absenteeism comprises many disciplines such as child development, criminal and juvenile justice, economics, education, epidemiology, law, leadership, nursing, medicine, political science, program evaluation, psychiatry, psychology, public and educational policy, school counseling, social work, and sociology, among others. These approaches can be divided generally into systemic perspectives that focus on overarching contexts and structural concerns as well as analytic perspectives that focus on specific contexts and individual concerns ( Kearney, 2021 ). Together these approaches have produced a rich and vast repository of knowledge over the past century regarding the conceptualization of school attendance/absenteeism with respect to domains such as definition, classification, risk/protection, trajectory, measurement, and intervention. At the same time, however, the breadth and multifaceted nature of these varied systemic and analytic approaches has led to myriad avenues of investigation that are not always well-coordinated or integrated. In addition, geographical and cultural differences in systems of education, including areas where education does not exist at all, further complicate the current landscape of school attendance/absenteeism ( Porto, 2020 ).

On top of all of this are relatively recent revolutionary and fundamental changes in human communication and interaction that are spurred in part by climate change, demands for equity and social justice, demographic and migration shifts, globalization, health crises, political movements, and technological advancements ( Krishnamurthy et al., 2019 ; Mao et al., 2019 ; Cleveland-Innes, 2020 ; Rapanta et al., 2021 ). As such, the very nature of educating children is being radically altered and will continue to evolve (or devolve) quickly over the next decades. The challenge before us in the next century is thus not only to assimilate the different systemic/analytic and geographic/cultural approaches to school attendance/absenteeism but also to meld this assimilation process with rapidly changing undercurrents of essential human functioning.

The purpose of this article is to provide a primer for stakeholders in this area regarding the past and next century vis-à-vis school attendance/absenteeism. As such, broad strokes are emphasized at the expense of greater detail regarding specific investigations. The article is divided into three main sections. The first section outlines key conclusions that can be drawn from a century’s worth of study of school attendance/absenteeism. The second section outlines how some of the revolutionary and fundamental changes noted above are impacting child education as well as traditional notions of school attendance/absenteeism. The third section, a theory of change approach, outlines a potential mutual vision for what the study of school attendance/absenteeism could look like in the coming decades.

The past: What is known?

A more than century’s worth of study allows for several broad conclusions about what is known regarding school attendance/absenteeism. Six such conclusions are presented next that are drawn from communal themes across the many disciplines in this area. First, school attendance/absenteeism are global issues but ones that are studied primarily within geographically limited areas . Less than three-quarters of children worldwide complete at least a lower secondary school education ( UNESCO, 2019 ). This rate is particularly restricted for sub-Saharan Africa (38%), northern Africa and western Asia (72%), central and southern Asia (75%), and Latin America and the Caribbean (76%). Unfortunately, the vast majority of research regarding school attendance/absenteeism comes from continental areas that have the highest completion rates in this regard: Europe and North America (98%) and Oceania (92%). Although emerging research is emanating from places such as South America, Asia, and Africa (e.g., Momo et al., 2019 ; Gonzálvez et al., 2020 ), not nearly enough is known in these areas about the domains of school attendance/absenteeism noted earlier.

Second, rates of school attendance/absenteeism differ substantially and disproportionately affect vulnerable student groups . Approximately 17% of children worldwide do not attend school, and many of these students are deliberately deprived of an education on the basis of gender, disability, and/or ethnicity. Students in low-income countries also experience greater barriers to an education such as food and housing insecurity, lack of instructors and academic materials, large class sizes, long distances to school, poor infrastructure, and violence ( UNESCO, 2019 ). Health crises and limited economic opportunities in these regions also drive students out of school and into premature labor roles ( Mussida et al., 2019 ; Reimers, 2022 ). Even in developed countries, elevated school absenteeism and dropout rates occur among vulnerable groups such as impoverished students, migrant students, students of color, students with disabilities, and students less familiar with the dominant cultural language ( Garcia and Weiss, 2018 ; Koehler and Schneider, 2019 ; Sosu et al., 2021 ).

Third, school attendance is generally associated with student benefit and school absenteeism is generally associated with student harm . One could contend that formal schooling is one of the best interventions ever designed for children, or at least for many children. Regular school attendance and school completion have been linked to adaptive functioning in many child developmental domains (e.g., academic, behavioral, health, psychological, and social; Rocque et al., 2017 ; Ehrlich et al., 2018 ). These effects have both short-term (e.g., educational achievement) as well as long-term (e.g., enhanced lifetime earning potential) positive impacts. Conversely, school absenteeism and school dropout have been associated with less adaptive functioning in these domains, with both short-term and long-term negative impacts ( Ansari et al., 2020 ; Rumberger, 2020 ). Caveats apply to this general conclusion, however. For many students, particularly vulnerable students, school is an environment associated with biased exclusionary discipline, racism, oppression, systemic discrimination, and victimization ( Kohli et al., 2017 ; Sanders, 2022 ). In related fashion, many students miss school as a more adaptive choice, such as to support a family economically ( Chang et al., 2019 ; Ricking and Schulze, 2019 ).

Fourth, school attendance/absenteeism are complicated constructs that require innovative measurement strategies . School attendance/absenteeism represents more than just physical presence or absence in a brick-and-mortar building. Many forms of school attendance/absenteeism exist across multiple instructional formats, including virtual or distance learning formats, that demand new and broader metrics (e.g., log-ins, completed assignments, student-teacher interactions, and mastery of skills) for measuring these constructs ( National Forum on Education Statistics, 2021 ). In addition, school absenteeism comprises a spectrum of attendance problems that can include full or partial day absences, missing classes, tardiness, student/family problems in the morning, and distress, somatic complaints, and other psychological problems that interfere with school attendance ( Li et al., 2021 ; Kearney and Gonzálvez, 2022 ). This has led to broader definitions of school attendance/absenteeism that focus less on physical presence/absence and more on engagement ( Patrick and Chambers, 2020 ; Kearney, 2021 ). Greater sophistication with respect to systemic evaluation (e.g., early warning systems) and analytic assessment (e.g., clinical protocols) methods also allows for more sensitive data analytic strategies to define problematic school absenteeism for certain student groups and across geographical regions ( Balfanz and Byrnes, 2019 ; Gonzálvez et al., 2021 ; Kearney and Childs, 2022 ).

Fifth, school attendance/absenteeism remains associated with multiple risk and protective factors across ecological levels . One advantage of the contemporary era is that a historical, singular focus on either student/family or other narrow-band risk/protective factors or on school-related or other broad-band risk/protective factors is yielding to more integrated approaches for understanding the complex ecology of school attendance/absenteeism ( Kim, 2020 ; Singer et al., 2021 ). Stakeholders now understand that interconnected risk/protective factors in this area range from granular to immense levels; examples include disability/academic achievement (student level), psychopathology/academic involvement (caregiver level), residential movement/cohesion (family level), victimization/positive norms (peer level), negative/positive climate quality (school level), neighborhood violence/safe avenues to school (community level), and structural economic inequalities/well-financed educational agencies (macro level; e.g., Zaff et al., 2017 ; Gubbels et al., 2019 ). In addition, stakeholders increasingly view school attendance/absenteeism from a comprehensive Bronfenbrenner-like ecological approach; examples include linkages between student-caregiver interactions (microsystem), caregiver-school staff communications (mesosystem), educational policies (exosystem), transportation vulnerabilities (macrosystem), and changes in these systems as children move from preschool to elementary, middle, and high school and beyond (chronosystem; e.g., Melvin et al., 2019 ; Childs and Scanlon, 2022 ).

Sixth, positive interventions to enhance school attendance and to reduce school absenteeism are generally though perhaps only moderately effective . Positive interventions are defined here as those that are empirically supported, intentional, and designed to foster well-being ( Tejada-Gallardo et al., 2020 ). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses reveal that positive interventions from both systemic and analytic perspectives are modestly effective at boosting school attendance and reducing school absenteeism (refer to, for example, Maynard et al., 2018 ; Keppens and Spruyt, 2020 ; Eklund et al., 2022 ). Key limitations, however, include insufficient integration of these various intervention strategies as well as incomplete dissemination and implementation across schools, community support agencies, and student groups ( Heyne et al., 2020 ; Kearney and Benoit, 2022 ). In contrast, negative interventions, defined here as punitive measures to suppress certain behaviors, paradoxically exacerbate school absenteeism and are disproportionately and perniciously applied to vulnerable student groups ( Mireles-Rios et al., 2020 ; Weathers et al., 2021 ). Examples include exclusionary discipline (e.g., arrests, expulsion, and suspension) and zero tolerance laws that often focus on deprivation of resources (e.g., via fines or restrictions on financial assistance or licenses) for absenteeism ( Conry and Richards, 2018 ; Rubino et al., 2020 ).

A century of work has produced a prodigious amount of knowledge regarding school attendance/absenteeism. But, the world is changing fast. As mentioned, revolutionary and fundamental changes in human communication and interaction will alter the course of child education and thus the study of school attendance/absenteeism for decades to come. A complete summary of all possible future effects on education is beyond the scope of this paper. Instead, we concentrate on some of the broadest and perhaps most wide-ranging influences in this regard: demographic shifts, climate change, demands for social justice and equity, and technological advancements and globalization. These influences, discussed next, are naturally complex, often subsuming other themes, and are naturally interwoven with one another.

The present: What is changing?

As stakeholders develop new visions of child education and school attendance/absenteeism for the future, several key fundamental shifts must be considered. One key fundamental shift worldwide involves demographic changes such as uneven (rising and declining) birthrates, more frequent migration patterns between regional countries and especially from south to north, and increased urbanization. Population growth is expected to largely emanate from African and Indo-Pacific countries and population decline is expected to be most acute for European and eastern Asian countries ( United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2022 ). In addition, older age groups will grow fastest and will eventually outnumber children and adolescents. Migration is expected to expand considerably due to violence, persecution, deprivation, and natural disasters. Urbanization will increase from 55 to 68 percent of people by 2050, especially in Asia and Africa ( United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2018 ).