How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step

Sean Glatch | May 2, 2024 | 32 Comments

To learn how to write a poem step-by-step, let’s start where all poets start: the basics.

This article is an in-depth introduction to how to write a poem. We first answer the question, “What is poetry?” We then discuss the literary elements of poetry, and showcase some different approaches to the writing process—including our own seven-step process on how to write a poem step by step.

So, how do you write a poem? Let’s start with what poetry is.

How to Write a Poem: Contents

What Poetry Is

- Literary Devices

How to Write a Poem, in 7 Steps

How to write a poem: different approaches and philosophies.

- Okay, I Know How to Write a Good Poem. What Next?

It’s important to know what poetry is—and isn’t—before we discuss how to write a poem. The following quote defines poetry nicely:

“Poetry is language at its most distilled and most powerful.” —Former US Poet Laureate Rita Dove

Poetry Conveys Feeling

People sometimes imagine poetry as stuffy, abstract, and difficult to understand. Some poetry may be this way, but in reality poetry isn’t about being obscure or confusing. Poetry is a lyrical, emotive method of self-expression, using the elements of poetry to highlight feelings and ideas.

A poem should make the reader feel something.

In other words, a poem should make the reader feel something—not by telling them what to feel, but by evoking feeling directly.

Here’s a contemporary poem that, despite its simplicity (or perhaps because of its simplicity), conveys heartfelt emotion.

Poem by Langston Hughes

I loved my friend. He went away from me. There’s nothing more to say. The poem ends, Soft as it began— I loved my friend.

Poetry is Language at its Richest and Most Condensed

Unlike longer prose writing (such as a short story, memoir, or novel), poetry needs to impact the reader in the richest and most condensed way possible. Here’s a famous quote that enforces that distinction:

“Prose: words in their best order; poetry: the best words in the best order.” —Samuel Taylor Coleridge

So poetry isn’t the place to be filling in long backstories or doing leisurely scene-setting. In poetry, every single word carries maximum impact.

Poetry Uses Unique Elements

Poetry is not like other kinds of writing: it has its own unique forms, tools, and principles. Together, these elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

The elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

Most poetry is written in verse , rather than prose . This means that it uses line breaks, alongside rhythm or meter, to convey something to the reader. Rather than letting the text break at the end of the page (as prose does), verse emphasizes language through line breaks.

Poetry further accentuates its use of language through rhyme and meter. Poetry has a heightened emphasis on the musicality of language itself: its sounds and rhythms, and the feelings they carry.

These devices—rhyme, meter, and line breaks—are just a few of the essential elements of poetry, which we’ll explore in more depth now.

Understanding the Elements of Poetry

As we explore how to write a poem step by step, these three major literary elements of poetry should sit in the back of your mind:

- Rhythm (Sound, Rhyme, and Meter)

1. Elements of Poetry: Rhythm

“Rhythm” refers to the lyrical, sonic qualities of the poem. How does the poem move and breathe; how does it feel on the tongue?

Traditionally, poets relied on rhyme and meter to accomplish a rhythmically sound poem. Free verse poems —which are poems that don’t require a specific length, rhyme scheme, or meter—only became popular in the West in the 20th century, so while rhyme and meter aren’t requirements of modern poetry, they are required of certain poetry forms.

Poetry is capable of evoking certain emotions based solely on the sounds it uses. Words can sound sinister, percussive, fluid, cheerful, dour, or any other noise/emotion in the complex tapestry of human feeling.

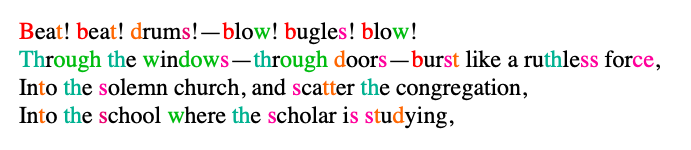

Take, for example, this excerpt from the poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” by Walt Whitman:

Red — “b” sounds

Blue — “th” sounds

Green — “w” and “ew” sounds

Purple — “s” sounds

Orange — “d” and “t” sounds

This poem has a lot of percussive, disruptive sounds that reinforce the beating of the drums. The “b,” “d,” “w,” and “t” sounds resemble these drum beats, while the “th” and “s” sounds are sneakier, penetrating a deeper part of the ear. The cacophony of this excerpt might not sound “lyrical,” but it does manage to command your attention, much like drums beating through a city might sound.

To learn more about consonance and assonance, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia , and the other uses of sound, take a look at our article “12 Literary Devices in Poetry.”

https://writers.com/literary-devices-in-poetry

It would be a crime if you weren’t primed on the ins and outs of rhymes. “Rhyme” refers to words that have similar pronunciations, like this set of words: sound, hound, browned, pound, found, around.

Many poets assume that their poetry has to rhyme, and it’s true that some poems require a complex rhyme scheme. However, rhyme isn’t nearly as important to poetry as it used to be. Most traditional poetry forms—sonnets, villanelles , rimes royal, etc.—rely on rhyme, but contemporary poetry has largely strayed from the strict rhyme schemes of yesterday.

There are three types of rhymes:

- Homophony: Homophones are words that are spelled differently but sound the same, like “tail” and “tale.” Homophones often lead to commonly misspelled words .

- Perfect Rhyme: Perfect rhymes are word pairs that are identical in sound except for one minor difference. Examples include “slant and pant,” “great and fate,” and “shower and power.”

- Slant Rhyme: Slant rhymes are word pairs that use the same sounds, but their final vowels have different pronunciations. For example, “abut” and “about” are nearly-identical in sound, but are pronounced differently enough that they don’t completely rhyme. This is also known as an oblique rhyme or imperfect rhyme.

Meter refers to the stress patterns of words. Certain poetry forms require that the words in the poem follow a certain stress pattern, meaning some syllables are stressed and others are unstressed.

What is “stressed” and “unstressed”? A stressed syllable is the sound that you emphasize in a word. The bolded syllables in the following words are stressed, and the unbolded syllables are unstressed:

- Un• stressed

- Plat• i• tud• i•nous

- De •act•i• vate

- Con• sti •tu• tion•al

The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is important to traditional poetry forms. This chart, copied from our article on form in poetry , summarizes the different stress patterns of poetry.

2. Elements of Poetry: Form

“Form” refers to the structure of the poem. Is the poem a sonnet , a villanelle, a free verse piece, a slam poem, a contrapuntal, a ghazal , a blackout poem , or something new and experimental?

Form also refers to the line breaks and stanza breaks in a poem. Unlike prose, where the end of the page decides the line breaks, poets have control over when one line ends and a new one begins. The words that begin and end each line will emphasize the sounds, images, and ideas that are important to the poet.

To learn more about rhyme, meter, and poetry forms, read our full article on the topic:

https://writers.com/what-is-form-in-poetry

3. Elements of Poetry: Literary Devices

“Poetry: the best words in the best order.” — Samuel Taylor Coleridge

How does poetry express complex ideas in concise, lyrical language? Literary devices—like metaphor, symbolism , juxtaposition , irony , and hyperbole—help make poetry possible. Learn how to write and master these devices here:

https://writers.com/common-literary-devices

To condense the elements of poetry into an actual poem, we’re going to follow a seven-step approach. However, it’s important to know that every poet’s process is different. While the steps presented here are a logical path to get from idea to finished poem, they’re not the only tried-and-true method of poetry writing. Poets can—and should!—modify these steps and generate their own writing process.

Nonetheless, if you’re new to writing poetry or want to explore a different writing process, try your hand at our approach. Here’s how to write a poem step by step!

1. Devise a Topic

The easiest way to start writing a poem is to begin with a topic.

However, devising a topic is often the hardest part. What should your poem be about? And where can you find ideas?

Here are a few places to search for inspiration:

- Other Works of Literature: Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it’s part of a larger literary tapestry, and can absolutely be influenced by other works. For example, read “The Golden Shovel” by Terrance Hayes , a poem that was inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We Real Cool.”

- Real-World Events: Poetry, especially contemporary poetry, has the power to convey new and transformative ideas about the world. Take the poem “A Cigarette” by Ilya Kaminsky , which finds community in a warzone like the eye of a hurricane.

- Your Life: What would poetry be if not a form of memoir? Many contemporary poets have documented their lives in verse. Take Sylvia Plath’s poem “Full Fathom Five” —a daring poem for its time, as few writers so boldly criticized their family as Plath did.

- The Everyday and Mundane: Poetry isn’t just about big, earth-shattering events: much can be said about mundane events, too. Take “Ode to Shea Butter” by Angel Nafis , a poem that celebrates the beautiful “everydayness” of moisturizing.

- Nature: The Earth has always been a source of inspiration for poets, both today and in antiquity. Take “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver , which finds meaning in nature’s quiet rituals.

- Writing Exercises: Prompts and exercises can help spark your creativity, even if the poem you write has nothing to do with the prompt! Here’s 24 writing exercises to get you started.

At this point, you’ve got a topic for your poem. Maybe it’s a topic you’re passionate about, and the words pour from your pen and align themselves into a perfect sonnet! It’s not impossible—most poets have a couple of poems that seemed to write themselves.

However, it’s far more likely you’re searching for the words to talk about this topic. This is where journaling comes in.

Sit in front of a blank piece of paper, with nothing but the topic written on the top. Set a timer for 15-30 minutes and put down all of your thoughts related to the topic. Don’t stop and think for too long, and try not to obsess over finding the right words: what matters here is emotion, the way your subconscious grapples with the topic.

At the end of this journaling session, go back through everything you wrote, and highlight whatever seems important to you: well-written phrases, poignant moments of emotion, even specific words that you want to use in your poem.

Journaling is a low-risk way of exploring your topic without feeling pressured to make it sound poetic. “Sounding poetic” will only leave you with empty language: your journal allows you to speak from the heart. Everything you need for your poem is already inside of you, the journaling process just helps bring it out!

Learn more about keeping a daily journal here:

How to Start Journaling: Practical Advice on How to Journal Daily

3. Think About Form

As one of the elements of poetry, form plays a crucial role in how the poem is both written and read. Have you ever wanted to write a sestina ? How about a contrapuntal, or a double cinquain, or a series of tanka? Your poem can take a multitude of forms, including the beautifully unstructured free verse form; while form can be decided in the editing process, it doesn’t hurt to think about it now.

4. Write the First Line

After a productive journaling session, you’ll be much more acquainted with the state of your heart. You might have a line in your journal that you really want to begin with, or you might want to start fresh and refer back to your journal when you need to! Either way, it’s time to begin.

What should the first line of your poem be? There’s no strict rule here—you don’t have to start your poem with a certain image or literary device. However, here’s a few ways that poets often begin their work:

- Set the Scene: Poetry can tell stories just like prose does. Anne Carson does just this in her poem “Lines,” situating the scene in a conversation with the speaker’s mother.

- Start at the Conflict : Right away, tell the reader where it hurts most. Margaret Atwood does this in “Ghost Cat,” a poem about aging.

- Start With a Contradiction: Juxtaposition and contrast are two powerful tools in the poet’s toolkit. Joan Larkin’s poem “Want” begins and ends with these devices. Carlos Gimenez Smith also begins his poem “Entanglement” with a juxtaposition.

- Start With Your Title: Some poets will use the title as their first line, like Ron Padgett’s poem “Ladies and Gentlemen in Outer Space.”

There are many other ways to begin poems, so play around with different literary devices, and when you’re stuck, turn to other poetry for inspiration.

5. Develop Ideas and Devices

You might not know where your poem is going until you finish writing it. In the meantime, stick to your literary devices. Avoid using too many abstract nouns, develop striking images, use metaphors and similes to strike interesting comparisons, and above all, speak from the heart.

6. Write the Closing Line

Some poems end “full circle,” meaning that the images the poet used in the beginning are reintroduced at the end. Gwendolyn Brooks does this in her poem “my dreams, my work, must wait till after hell.”

Yet, many poets don’t realize what their poems are about until they write the ending line . Poetry is a search for truth, especially the hard truths that aren’t easily explained in casual speech. Your poem, too, might not be finished until it comes across a necessary truth, so write until you strike the heart of what you feel, and the poem will come to its own conclusion.

7. Edit, Edit, Edit!

Do you have a working first draft of your poem? Congratulations! Getting your feelings onto the page is a feat in itself.

Yet, no guide on how to write a poem is complete without a note on editing. If you plan on sharing or publishing your work, or if you simply want to edit your poem to near-perfection, keep these tips in mind.

- Adjectives and Adverbs: Use these parts of speech sparingly. Most imagery shouldn’t rely on adjectives and adverbs, because the image should be striking and vivid on its own, without too much help from excess language.

- Concrete Line Breaks: Line breaks help emphasize important words, making certain images and themes clearer to the reader. As a general rule, most of your lines should start and end with concrete words—nouns and verbs especially.

- Stanza Breaks: Stanzas are like paragraphs to poetry. A stanza can develop a new idea, contrast an existing idea, or signal a transition in the poem’s tone. Make sure each stanza clearly stands for something as a unit of the poem.

- Mixed Metaphors: A mixed metaphor is when two metaphors occupy the same idea, making the poem unnecessarily difficult to understand. Here’s an example of a mixed metaphor: “a watched clock never boils.” The meaning can be discerned, but the image remains unclear. Be wary of mixed metaphors—though some poets (like Shakespeare) make them work, they’re tricky and often disruptive.

- Abstractions: Above all, avoid using excessively abstract language. It’s fine to use the word “love” 2 or 3 times in a poem, but don’t use it twice in every stanza. Let the imagery in your poem express your feelings and ideas, and only use abstractions as brief connective tissue in otherwise-concrete writing.

Lastly, don’t feel pressured to “do something” with your poem. Not all poems need to be shared and edited. Poetry doesn’t have to be “good,” either—it can simply be a statement of emotions by the poet, for the poet. Publishing is an admirable goal, but also, give yourself permission to write bad poems, unedited poems, abstract poems, and poems with an audience of one. Write for yourself—editing is for the other readers.

Poetry is the oldest literary form, pre-dating prose, theater, and the written word itself. As such, there are many different schools of thought when it comes to writing poetry. You might be wondering how to write a poem through different methods and approaches: here’s four philosophies to get you started.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Emotion

If you asked a Romantic Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the spontaneous emotion of the soul.

The Romantic Era viewed poetry as an extension of human emotion—a way of perceiving the world through unbridled creativity, centered around the human soul. While many Romantic poets used traditional forms in their poetry, the Romantics weren’t afraid to break from tradition, either.

To write like a Romantic, feel—and feel intensely. The words will follow the emotions, as long as a blank page sits in front of you.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Stream of Consciousness

If you asked a Modernist poet, “What is poetry?” they would tell you that poetry is the search for complex truths.

Modernist Poets were keen on the use of poetry as a window into the mind. A common technique of the time was “Stream of Consciousness,” which is unfiltered writing that flows directly from the poet’s inner dialogue. By tapping into one’s subconscious, the poet might uncover deeper truths and emotions they were initially unaware of.

Depending on who you are as a writer, Stream of Consciousness can be tricky to master, but this guide covers the basics of how to write using this technique.

How to Write a Poem: Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a practice of documenting the mind, rather than trying to control or edit what it produces. This practice was popularized by the Beat Poets , who in turn were inspired by Eastern philosophies and Buddhist teachings. If you asked a Beat Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the human consciousness, unadulterated.

To learn more about the art of leaving your mind alone , take a look at our guide on Mindfulness, from instructor Marc Olmsted.

https://writers.com/mindful-writing

How to Write a Poem: Poem as Camera Lens

Many contemporary poets use poetry as a camera lens, documenting global events and commenting on both politics and injustice. If you find yourself itching to write poetry about the modern day, press your thumb against the pulse of the world and write what you feel.

Additionally, check out these two essays by Electric Literature on the politics of poetry:

- What Can Poetry Do That Politics Can’t?

- Why All Poems Are Political (TL;DR: Poetry is an urgent expression of freedom).

Okay, I Know How to Write a Poem. What Next?

Poetry, like all art forms, takes practice and dedication. You might write a poem you enjoy now, and think it’s awfully written 3 years from now; you might also write some of your best work after reading this guide. Poetry is fickle, but the pen lasts forever, so write poems as long as you can!

Once you understand how to write a poem, and after you’ve drafted some pieces that you’re proud of and ready to share, here are some next steps you can take.

Publish in Literary Journals

Want to see your name in print? These literary journals house some of the best poetry being published today.

https://writers.com/best-places-submit-poetry-online

Assemble and Publish a Manuscript

A poem can tell a story. So can a collection of poems. If you’re interested in publishing a poetry book, learn how to compose and format one here:

https://writers.com/poetry-manuscript-format

How to Write a Poem: Join a Writing Community

Writers.com is an online community of writers, and we’d love it if you shared your poetry with us! Join us on Facebook and check out our upcoming poetry courses .

Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it exists to educate and uplift society. The world is waiting for your voice, so find a group and share your work!

Sean Glatch

32 comments.

super useful! love these articles 💕

Finally found a helpful guide on Poetry’. For many year, I have written and filed numerous inspired pieces from experiences and moment’s of epiphany. Finally, looking forward to convertinb to ‘poetry format’. THANK YOU, KINDLY. 🙏🏾

Indeed, very helpful, consize. I could not say more than thank you.

I’ve never read a better guide on how to write poetry step by step. Not only does it give great tips, but it also provides helpful links! Thank you so much.

Thank you very much, Hamna! I’m so glad this guide was helpful for you.

Best guide so far

Very inspirational and marvelous tips

Thank you super tips very helpful.

I have never gone through the steps of writing poetry like this, I will take a closer look at your post.

Beautiful! Thank you! I’m really excited to try journaling as a starter step x

[…] How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step […]

This is really helpful, thanks so much

Extremely thorough! Nice job.

Thank you so much for sharing your awesome tips for beginner writers!

People must reboot this and bookmark it. Your writing and explanation is detailed to the core. Thanks for helping me understand different poetic elements. While reading, actually, I start thinking about how my husband construct his songs and why other artists lack that organization (or desire to be better). Anyway, this gave me clarity.

I’m starting to use poetry as an outlet for my blogs, but I also have to keep in mind I’m transitioning from a blogger to a poetic sweet kitty potato (ha). It’s a unique transition, but I’m so used to writing a lot, it’s strange to see an open blog post with a lot of lines and few paragraphs.

Anyway, thanks again!

I’m happy this article was so helpful, Eternity! Thanks for commenting, and best of luck with your poetry blog.

Yours in verse, Sean

One of the best articles I read on how to write poems. And it is totally step by step process which is easy to read and understand.

Thanks for the step step explanation in how to write poems it’s a very helpful to me and also for everyone one. THANKYOU

Totally detailed and in a simple language told the best way how to write poems. It is a guide that one should read and follow. It gives the detailed guidance about how to write poems. One of the best articles written on how to write poems.

what a guidance thank you so much now i can write a poem thank you again again and again

The most inspirational and informative article I have ever read in the 21st century.It gives the most relevent,practical, comprehensive and effective insights and guides to aspiring writers.

Thank you so much. This is so useful to me a poetry

[…] Write a short story/poem (Here are some tips) […]

It was very helpful and am willing to try it out for my writing Thanks ❤️

Thank you so much. This is so helpful to me, and am willing to try it out for my writing .

Absolutely constructive, direct, and so useful as I’m striving to develop a recent piece. Thank you!

thank you for your explanation……,love it

Really great. Nothing less.

I can’t thank you enough for this, it touched my heart, this was such an encouraging article and I thank you deeply from my heart, I needed to read this.

great teaching Did not know all that in poetry writing

This was very useful! Thank you for writing this.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Poem Generator

Write an entire poem in less than a minute!

Didactic Cinquain

Rhyming couplets, narrative poem, line by line, alliteration, our other generators, dating profile generator, name generator, plot generator, song lyrics generator, letter generator, character generator, random generator, coming soon - the app, suggest a generator.

Powered by Aardgo

How to write a poem with our generator.

- 1. Choose a type of poem.

- 2. Select some keywords.

- 3. Let us automatically create a poem and an image.

Masterpiece Generator refers to a set of text generator tools created by Aardgo. The tools are designed to be cool and entertain, but also help aspiring writers create a range of different media, including plots, lyrics for songs, poems, letters and names. Some generated content parodies existing styles and artists, whilst others are based on original structures.

Our first generator, Song Lyrics Generator was launched in 2002 as a student magazine project. After it proved popular, we expanded to include plots, and the project grew from there.

We're proud to see work we've helped you create pop up on blogs and in fun projects. We enjoy watching you read your creations on YouTube. We're currently developing a cool app based on our site.

- Annual Emerging Poets Slam 2023

- Poems About the Pandemic Generation Slam

- Slam on AI - Programs or Poems?

- Slam on Gun Control

- Poet Leaderboard

- Poetry Genome

- What are groups?

- Browse groups

- All actions

- Find a local poetry group

- Top Poetry Commenters

- AI Poetry Feedback

- Poetry Tips

- Poetry Terms

- Why Write a Poem

- Scholarship Winners

6 Tips for Using Poetry in a Speech

The term “public speaking” may be defined as relaying information to a group of people in a structured, deliberate manner intended to inform, influence, or entertain the listeners. People may choose to give a speech in order to transmit information, motivate people to act, or simply to tell a story. A good orator should be able to change the emotions of their listener and not just inform them. Hey, we get it. Writing a speech on top of actually performing it in public can be super scary and intimidating, but it gets easier once you think of a speech as an epic spoken word poem. Check out our tip guide for getting over some of those spoken word nerves. Most speeches actually use the same literary devices you already use in tons of your poetry. Think of John F. Kennedy’s inaugural speech: “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country” (why hello there, chiasmus). Now, don’t you feel better? By using the boss poet skills you already have, you can create a speech with descriptive and moving language that really entices your listeners. Keep on reading to find out how to write a speech that grabs your listeners and holds their attention.

- Why Do I Have to Write This Thing Anyway? Think about the atmosphere of the occasion at which you’ll present your speech. This will affect the style and tone of your words, just like in a poem (example: a political poem would use a much more serious tone than a poem about a funny memory between you and your best friend). Also pay attention to your audience. For example, a wedding is an event that occurs frequently but no two weddings are exactly alike. This is because different guests with varying personalities attend each one. So, if you were to write a wedding speech, you’d tailor it to match the specific personalities of the couple as well as the guests. Use your poet’s intuition to choose which literacy devices you think everyone will best respond to.

- Use Metaphors and Similes. Ah, oldies but goodies. A metaphor is a stylistic device that assigns the characteristics of one thing to another. For example, in his famous "I Have a Dream" speech, when Martin Luther King described Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation as, "a great beacon light of hope for millions of Negro slaves," he used a metaphor to imply that the Emancipation Proclamation had the attributes of a shining beacon light. A simile is a literary device that compares two unlike things using the words “like” or “as.” If King had said the Emancipation Proclamation was " like a great beacon light of hope," he would have been using a simile. Metaphors and similes are elegant ways of saying something-- and listeners respond well to this type of fancy language that’s also easy to understand.

- Describe, Describe, Describe! Appeal to your listeners' senses by using concrete, vividly descriptive language. Let’s look at this in action. In a famous nineteenth-century murder case, the senator and powerful orator Daniel Webster recreated the murder scene in the minds of the jurors with expressive descriptions: "The room is uncommonly open to the admission of light. The face of the innocent sleeper is turned from the murderer, and the beams of the moon, resting on the gray locks of his aged temple, show him where to strike. The fatal blow is given!" By honing your ability to create intense imagery, you can entice your listeners to use all five of their senses and make your speech that much more impressive .

- This Isn’t an Essay for School-- Go Ahead and Repeat Yourself . Repetition is when a word or phrase is used more than once. In a speech, repetition forces the attention of your audience, quickens the pace of your words, and creates an insistent rhythm. Consider this famous example uttered by Winston Churchill during World War Two: "We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing-grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills." Bet’cha the next thought in your head is “we shall…” See, it totally works! Repetition helps to drill key words and ideas into your listeners’ minds so that they remember the most important sections of your speech.

- Practice your Delivery and Be CONFIDENT . If you’re confident when speaking and passionate about your speech topic, it will definitely come across as powerful in your delivery. Read your speech quietly aloud to yourself, listening for its musicality or beat. Then, start over again but a little louder. Each time you read your speech out loud, increase your volume. It might sound silly screaming your speech, but it’ll definitely help with your confidence and once it’s time to perform it for real, speaking at a normal yet assertive register will be a piece of cake. Familiarize yourself with the core ideas and images in your speech. The more you understand the speech, the more likely your audience will understand it and respond to the points you are trying to get across. The more strongly you identify with your work the easier it will be for your audience to follow.

- Power Poetry . Now that you’re more familiar with how to write a speech using poetic elements, it’s time to test it out. The ability to read your written work aloud is a gift of immense value because it expresses with grace and clarity thoughts and feelings that are often difficult to find appropriate words for in ordinary prose. Share your poetic speech with Power Poetry and better yet, record yourself so that you can see how much your hard work paid off!

Related Poems

Create a poem about this topic

- Join 230,000+ POWER POETS!

- Request new password

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing About Poetry

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Writing about poetry can be one of the most demanding tasks that many students face in a literature class. Poetry, by its very nature, makes demands on a writer who attempts to analyze it that other forms of literature do not. So how can you write a clear, confident, well-supported essay about poetry? This handout offers answers to some common questions about writing about poetry.

What's the Point?

In order to write effectively about poetry, one needs a clear idea of what the point of writing about poetry is. When you are assigned an analytical essay about a poem in an English class, the goal of the assignment is usually to argue a specific thesis about the poem, using your analysis of specific elements in the poem and how those elements relate to each other to support your thesis.

So why would your teacher give you such an assignment? What are the benefits of learning to write analytic essays about poetry? Several important reasons suggest themselves:

- To help you learn to make a text-based argument. That is, to help you to defend ideas based on a text that is available to you and other readers. This sharpens your reasoning skills by forcing you to formulate an interpretation of something someone else has written and to support that interpretation by providing logically valid reasons why someone else who has read the poem should agree with your argument. This isn't a skill that is just important in academics, by the way. Lawyers, politicians, and journalists often find that they need to make use of similar skills.

- To help you to understand what you are reading more fully. Nothing causes a person to make an extra effort to understand difficult material like the task of writing about it. Also, writing has a way of helping you to see things that you may have otherwise missed simply by causing you to think about how to frame your own analysis.

- To help you enjoy poetry more! This may sound unlikely, but one of the real pleasures of poetry is the opportunity to wrestle with the text and co-create meaning with the author. When you put together a well-constructed analysis of the poem, you are not only showing that you understand what is there, you are also contributing to an ongoing conversation about the poem. If your reading is convincing enough, everyone who has read your essay will get a little more out of the poem because of your analysis.

What Should I Know about Writing about Poetry?

Most importantly, you should realize that a paper that you write about a poem or poems is an argument. Make sure that you have something specific that you want to say about the poem that you are discussing. This specific argument that you want to make about the poem will be your thesis. You will support this thesis by drawing examples and evidence from the poem itself. In order to make a credible argument about the poem, you will want to analyze how the poem works—what genre the poem fits into, what its themes are, and what poetic techniques and figures of speech are used.

What Can I Write About?

Theme: One place to start when writing about poetry is to look at any significant themes that emerge in the poetry. Does the poetry deal with themes related to love, death, war, or peace? What other themes show up in the poem? Are there particular historical events that are mentioned in the poem? What are the most important concepts that are addressed in the poem?

Genre: What kind of poem are you looking at? Is it an epic (a long poem on a heroic subject)? Is it a sonnet (a brief poem, usually consisting of fourteen lines)? Is it an ode? A satire? An elegy? A lyric? Does it fit into a specific literary movement such as Modernism, Romanticism, Neoclassicism, or Renaissance poetry? This is another place where you may need to do some research in an introductory poetry text or encyclopedia to find out what distinguishes specific genres and movements.

Versification: Look closely at the poem's rhyme and meter. Is there an identifiable rhyme scheme? Is there a set number of syllables in each line? The most common meter for poetry in English is iambic pentameter, which has five feet of two syllables each (thus the name "pentameter") in each of which the strongly stressed syllable follows the unstressed syllable. You can learn more about rhyme and meter by consulting our handout on sound and meter in poetry or the introduction to a standard textbook for poetry such as the Norton Anthology of Poetry . Also relevant to this category of concerns are techniques such as caesura (a pause in the middle of a line) and enjambment (continuing a grammatical sentence or clause from one line to the next). Is there anything that you can tell about the poem from the choices that the author has made in this area? For more information about important literary terms, see our handout on the subject.

Figures of speech: Are there literary devices being used that affect how you read the poem? Here are some examples of commonly discussed figures of speech:

- metaphor: comparison between two unlike things

- simile: comparison between two unlike things using "like" or "as"

- metonymy: one thing stands for something else that is closely related to it (For example, using the phrase "the crown" to refer to the king would be an example of metonymy.)

- synecdoche: a part stands in for a whole (For example, in the phrase "all hands on deck," "hands" stands in for the people in the ship's crew.)

- personification: a non-human thing is endowed with human characteristics

- litotes: a double negative is used for poetic effect (example: not unlike, not displeased)

- irony: a difference between the surface meaning of the words and the implications that may be drawn from them

Cultural Context: How does the poem you are looking at relate to the historical context in which it was written? For example, what's the cultural significance of Walt Whitman's famous elegy for Lincoln "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed" in light of post-Civil War cultural trends in the U.S.A? How does John Donne's devotional poetry relate to the contentious religious climate in seventeenth-century England? These questions may take you out of the literature section of your library altogether and involve finding out about philosophy, history, religion, economics, music, or the visual arts.

What Style Should I Use?

It is useful to follow some standard conventions when writing about poetry. First, when you analyze a poem, it is best to use present tense rather than past tense for your verbs. Second, you will want to make use of numerous quotations from the poem and explain their meaning and their significance to your argument. After all, if you do not quote the poem itself when you are making an argument about it, you damage your credibility. If your teacher asks for outside criticism of the poem as well, you should also cite points made by other critics that are relevant to your argument. A third point to remember is that there are various citation formats for citing both the material you get from the poems themselves and the information you get from other critical sources. The most common citation format for writing about poetry is the Modern Language Association (MLA) format .

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.20: Writing Assignment: Figure of Speech Poem

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 87405

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Write a poem that incorporates a figure of speech: simile, metaphor, personification, hyperbole, or understatement. You may write it in first-person point of view (I, me, my, we, us, etc.) or third-person point of view (he, she, it, they, etc.) Here is a list of poem suggestions:

- Write a nature poem using a simile like Carl Sandburg did in “Fog.” Be sure to use the word like or as .

- Choose an abstract noun (peace, hate, joy, etc.) and write a poem using an extended metaphor like Emily Dickinson did in “Hope is the Thing with Feathers.” Be sure the abstract noun is compared to a concrete noun (something the reader can visualize) by using the word is.

- Choose an inanimate object and personify it like Robert Frost did in “Storm Fear.”

- Create an original hyperbole and use the line in a poem like Robert Frost did in “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.”

- Write a narrative poem that shows understatement like Mary Howitt’s poem “The Spider and the Fly.”

You get the idea, right? Brainstorm a list of your own ideas, avariation of one of the above, or use one of the above ideas.

Show Don’t Tell

Remember to use specific nouns and strong action verbs. Remember to use your senses: sight, sound, taste, touch, smell. Of course, poets use less words than fictional writers, too.

Line Breaks

Follow the traditional line breaks and format that most free-verse poets use. Make the line breaks where there is punctuation, an end of a phrase, or the end of a sentence.

Final Draft Instructions

Follow these instructions for typing the final draft:

- The poem must be typed in a Microsoft Word file (.docx).

- It must have one-inch margins, be single-spaced, and typed in a 12 pt. readable font like Times New Roman, Calibri, or Arial.

- Don’t allow the auto-correct in Microsoft Word to capitalize the first line of each poem. Use conventional English rules to write your lines.

- In the upper left-hand corner of page 1, type your first and last name, the name of the class, the date the assignment is due, and the assignment name. Example:

Jane Doe ENGL 1465–Creative Writing Due Date: Writing Assignment: Figure of Speech Poem

- Be sure to give your poem a title. Do not bold, enlarge, or punctuate the title. Capitalize the first word and each important word in the title.

- Writing Assignment: Figure of Speech Poem. Authored by : Linda Frances Lein, M.F.A. License : CC BY: Attribution

Want to adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open practices.

The meaning of language can be literal or figurative. Literal language states exactly what something is. On the other hand, figurative language creates meaning by comparing one thing to another thing. Poets use figures of speech in their poems. Several types of figures of speech exist for them to choose from. Five common ones are simile, metaphor, personification, hypberbole, and understatement.

Simile

A simile compares one thing to another by using the words like or as. Read Shakespeare’s poem “Sonnet 130.”

Sonnet 130 Author : William Shakespeare © 1598

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red, than her lips red: If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damask’d, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound: I grant I never saw a goddess go,— My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare, as any she belied with false compare.

In this sonnet, Shakespeare’s simile in the first line is a contrast where one thing is not like or as something else. He wrote, “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun.”

A metaphor compares one to another by saying one thing is another. Read Emily Dickinson’s poem “Hope Is the Thing with Feathers.”

Hope Is the Thing with Feathers Author : Emily Dickinson

“Hope” is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul And sings the tune without the words And never stops at all

And sweetest in the Gale is heard And sore must be the storm — That could abash the little Bird That kept so many warm —

I’ve heard it in the chillest land — And on the strangest Sea — Yet, never, in Extremity, It asked a crumb — of Me.

Notice that Emily Dickinson compared hope to a bird–the thing with feathers. Because there are bird images throughout the poem, it is called an extended metaphor poem.

Personification

A personification involves giving a non-human, inanimate object the qualities of a person. Robert Frost did that in his poem “Storm Fear.”

Storm Fear Author : Robert Frost ©1913

When the wind works against us in the dark, And pelts with snow The lower chamber window on the east, And whispers with a sort of stifled bark, The beast, ‘Come out! Come out!— It costs no inward struggle not to go, Ah, no! I count our strength, Two and a child, Those of us not asleep subdued to mark How the cold creeps as the fire dies at length,— How drifts are piled, Dooryard and road ungraded, Till even the comforting barn grows far away And my heart owns a doubt Whether ’tis in us to arise with day And save ourselves unaided.

Look specifically at the strong action verbs to find the human traits that are attributed to the wind and storm.

A hyperbole is an exaggeration of the truth in order to create an effect. Sometimes that’s done in a single statement. Other times it can happen with repetition like in Robert Frost’s famous poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” Read the poem aloud. Notice the effect of the last two lines. The reader feels the tiredness of the weary traveler.

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening Author : Robert Frost ©1923

Whose woods these are I think I know. His house is in the village though; He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound’s the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep.

Understatement

Understatement is the exact opposite of a hyperbole. The writer deliberately chooses to downplay the significance or seriousness of a situation or an event. This is evident in Mary Howitt’s Poem ” The Spider and the Fly.”

The Spider and the Fly Author : Mary Howitt ©1853

Will you walk into my parlour, said a Spider to a Fly; ‘Tis the prettiest little parlour that ever you did spy. The way into my parlour is up a winding stair, And I have many pretty things to shew when you get there. Oh, no, no! said the little Fly; to ask me is in vain: For who goes up that winding stair shall ne’er come down again.

Said the cunning Spider to the Fly, Dear friend, what can I do To prove the warm affection I have ever felt tor you? I have within my parlour great store of all that’s nice: I’m sure you’re very welcome; will you please to take a slice! Oh, no, no! said the little Fly; kind sir, that cannot be; For I know what’s in your pantry, and I do not wish to see.

Sweet creature, said the Spider, you’re witty and you’re wise; How handsome are your gaudy wings, how brilliant are your eyes! I have a little looking-glass upon my parlour-shelf; If you’ll step in one moment, dear, you shall behold yourself. Oh, thank you, gentle sir, she said, for what you’re pleased to say; And wishing you good morning now, I’ll call another day.

The Spider turn’d him round again, and went into his den, For well he knew that silly Fly would soon come back again. And then he wore a tiny web, in a little corner sly, And set his table ready for to dine upon the Fly; And went out to his door again, and merrily did sing, Come hither, pretty little Fly, with the gold and silver wing.

Alas, alas! how very soon this silly little Fly, Hearing his wily flattering words, came slowly fluttering by. With humming wings she hung aloft, then nearer and nearer drew. Thinking only of her crested head and gold and purple hue: Thinking only of her brilliant wings, poor silly thing! at last, Up jump’d the cruel Spider, and firmly held her fast!

He dragg’d her up his winding stair, into his dismal den, Within his little parlour; but she ne’er came down again. And now, my pretty maidens, who may this story hear, To silly, idle, flattering words, I pray you ne’er give ear; Unto an evil counsellor close heart, and ear, and eye, And learn a lesson from this tale of the Spider and the Fly.

Introduction to Creative Writing by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Poetry Facts

The Power of Poetry in Speeches

As a poetry lover, I’m sure you understand how influential poetry can be. Throughout history, many great leaders, activists, politicians have brought poetry into their speeches, crafting powerful messages that can (and did) change the world.

In today’s article, we’re going to look at poetry in speeches , why you should use poetry in your next speech, how to go about doing so, and of course, the famous poetic speeches across eras. Let’s dive in!

Why Use Poetry in a Public Speech

Poetry is powerful. That’s why there are many benefits to using poetry in a public speech. What benefits, you ask?

Well, for starter, a poem can really serve as a highlight of a speech, breaking the usual monotony. It adds a fresher element to the speech, and helps to capture the audience’s attention better.

Poetry can also be a very good reference point in your speech. By adding a familiar poem to the audience, the speaker can help the audience understand the subject that he or she is trying to convey better.

A good poem can really add an additional depth to your speech, if you know how to use it right. The audience can’t help but feel a strong influence, and the speaker has a much better chance of leaving an impact.

I think all of us can agree that poetry has an air of literary elegance to it. By adding poetry to your speech, you also bring that elegance and a lot of class into your presentation.

Finally, sometimes, poetry can say a lot more with less. Adding a poem at the right moment of the talk can help you being more concise and establish a deep connection with the audience.

So I hope by now I’ve convinced you that it’s a good idea to try adding poetry into your speech. In the next section, we’re going to talk about how to do it.

How to Use Poetry in A Public Speech

It’s pretty clear that poetry can enhance a speech greatly if done right. But it can be tricky if you’re not a poet nor a student of poetry yourself. Here are something to keep in mind if you want to use poetry in your next speech:

1. Choose the right poem

This should go without saying, but if you’re going to use poetry in your speech, make sure that the poem you choose fit within the context of what you’re trying to say. A poem should help you get your point across and make an impression on the audience, not making them confused or worse, zone out. So do your homework.

2. Have a plan

Most people don’t read poetry on a daily basis. This means that you can’t just bring a poem out of nowhere into your speech. You need to provide some introduction to the poem, why do you chose the poem, what’s the background story, etc. Prepare the audience so that they can listen to the poem from the best position possible.

3. Speak like a poet

Ever seen a spoken-word poet perform on stage? If you haven’t, then you should do it because you will learn a lot from them. Writing poetry is an art, but not many people think the same about delivering a poem to an audience that way. You’ll need to learn how to project from the diaphragm, posturing, pacing, etc. Watch a poet perform and try to practice your delivery as best as you can.

4. Don’t think too much

The last tip is kind of counter intuitive, but after all the preparing and practicing, you should not think when you go and perform. Thinking is great when you’re trying to practice, but once on stage, it will likely hinder your performance. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. After all, that’s how you get better.

5 Famous Poetic Speeches in History

1. i have a dream by martin luther king jr..

This is probably one of the most inspiring speeches of all time. Delivered on the 28th of August, 1963 by American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., “I have a dream” was a defining speech of the civil rights movement.

In the speech, King used anaphora, a poetic device in which the author repeats an expression at the beginning of a number of sentences. With a single phrase “I have a dream,” Martin Luther King Jr. joined ranks with the men who shaped modern America.

2. We shall fight on the beaches by Winston Churchill

“We shall fight on the beaches” is one of the three major speeches by the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. This speech was delivered to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom on the 4th of June, 1940, warning about a possible invasion attempt by Nazi Germany.

Churchill is known for spending hours working on every minute of his speech. He wrote every word, and carefully crafting them so that the final draft “looks like a draft of a poem,” according to many critics.

3. Ain’t I a Woman? by Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was a well known anti-slavery speaker and one of the most revolutionary advocates for women’s human rights in the 1800s. The speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” was delivered at the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention held in Akron, Ohio, addressing the discrimination of woman and African Americans in the post-Civil War era.

It is a poetic speech that many people have adapted it into a poem itself. Here’s the speech, delivered by Nkechi at a TEDx event in 2013.

4. Still I Rise by Maya Angelou

This one is a legit poem as a speech. “Still I Rise” is a poem written by Maya Angelou, an American poet, memoirist, and civil rights activist. She is well-known for uplifting fellow African American women through her work.

“Still I Rise” is one of Angelou’s most popular poems, inspiring black women everywhere to keep good faith and striving for equality and peace.

Final thoughts

By now, I’m sure we all can understand how much weight that poetry, or even just a poetic device, can bring into a speech. I hope that you’ve learned something new and useful, maybe even some inspirations to incorporate poetry into the next chance you have to deliver a public speech.

More interesting articles about poetry:

- A Brief Introduction To Closed Form Poetry

- The Beauty Of Typography In Poetry

- Dissonance In Poetry: Everything You Need To Know

Thomas Dao is the guy who created Poem Home, a website where people can read about all things poetry related. When he’s not busy working on his next project, you can find him reading a good book or spending time with family and friends.

Share this article

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related Articles

6 Poems About Body Image That Reminds You to Love Yourself

There’s no denying it: society tells us that our bodies are not good enough. We’re constantly bombarded with images of

9 Encouraging Poems About Waiting For Love

True love is worth the wait. Don’t forget that, don’t ever forget that. You neither have to force it, nor

5 Best Poems About Touch For Every Loving Couple Out There

Touch plays a crucial role in every loving relationship. Generally speaking, people feel more satisfied when physical affection is a

A Brief Look at Middle Eastern Poetry

The Middle East has one of the greatest literary traditions known to mankind. It reflects their history events, culture, and

Top 20 Best Poetry Books That Make The Perfect Gift

Looking for the perfect gift for the poetry lover in your life? We’ve rounded up a list of our favorite

14 Powerful Poems About Finding Yourself

There’s something very special about poetry. It has the ability to capture our thoughts and feelings in a way that

Panamanian Poetry: A Diamond In The Rough

Perhaps, in the eyes of international visitors, Panama is most famous for its engineering marvel – the Panama Canal connecting

Cynthia – A Slam Poem by Schmidt from 22 Jump Street

Are you looking for Cynthia, the master piece of slam poetry in 22 Jump Street? If so, you’ve come to

10+ Heavenly Poems About Angel Wings

In many cultures, the image of winged angel are very common. The wings of an angel is a magnificent sight

22 Beautiful Poems for Aunts – The Second Mothers

Whether you are close to our aunties or have only seen them occasionally, these poems about aunts might offer a

5 Best Poems About Lions – The King Of Jungle

Lions are strong and majestic creatures, with impressive fur and sharp claws. In this collection of poems about lions, we

Poetry of Departures – Analysis, Meaning, & Summary

“Poetry of Departures” by Philip Larkin is a beautiful, plain-spoken poem from “The Less Deceived.” First published in 1995, this

Sponsored Articles

Figure of Speech

Definition of figure of speech.

A figure of speech is a word or phrase that is used in a non-literal way to create an effect. This effect may be rhetorical as in the deliberate arrangement of words to achieve something poetic, or imagery as in the use of language to suggest a visual picture or make an idea more vivid. Overall, figures of speech function as literary devices because of their expressive use of language. Words are used in other ways than their literal meanings or typical manner of application.

For example, Margaret Atwood utilizes figures of speech in her poem “ you fit into me ” as a means of achieving poetic meaning and creating a vivid picture for the reader.

you fit into me like a hook into an eye a fish hook an open eye

The simile in the first two lines sets forth a comparison between the way “you” fits into the poet like a hook and eye closure for perhaps a garment. This is an example of rhetorical effect in that the wording carefully achieves the idea of two things meant to connect to each other. In the second two lines, the wording is clarified by adding “fish” to “hook” and “open” to “eye,” which calls forth an unpleasant and even violent image. The poet’s descriptions of hooks and eyes are not meant literally in the poem. Yet the use of figurative language allows the poet to express two very different meanings and images that enhance the interpretation of the poem through contrast .

Types of Figures of Speech

The term figure of speech covers a wide range of literary devices, techniques, and other forms of figurative language, a few of which include:

Personification

Understatement.

- Alliteration

- Onomatopoeia

- Circumlocution

Common Examples of Figures of Speech Used in Conversation

Many people use figures of speech in conversation as a way of clarifying or emphasizing what they mean. Here are some common examples of conversational figures of speech:

Hyperbole is a figure of speech that utilizes extreme exaggeration to emphasize a certain quality or feature.

- I have a million things to do.

- This suitcase weighs a ton.

- This room is an ice-box.

- I’ll die if he doesn’t ask me on a date.

- I’m too poor to pay attention.

Understatement is a figure of speech that invokes less emotion than would be expected in reaction to something. This downplaying of reaction is a surprise for the reader and generally has the effect of showing irony .

- I heard she has cancer, but it’s not a big deal.

- Joe got his dream job, so that’s not too bad.

- Sue won the lottery, so she’s a bit excited.

- That condemned house just needs a coat of paint.

- The hurricane brought a couple of rain showers with it.

A paradox is a figure of speech that appears to be self-contradictory but actually reveals something truthful.

- You have to spend money to save it.

- What I’ve learned is that I know nothing.

- You have to be cruel to be kind.

- Things get worse before they get better.

- The only rule is to ignore all rules.

A pun is a figure of speech that contains a “ play ” on words, such as using words that mean one thing to mean something else or words that sound alike in as a means of changing meaning.

- A sleeping bull is called a bull-dozer.

- Baseball players eat on home plates.

- Polar bears vote at the North Poll.

- Fish are smart because they travel in schools.

- One bear told another that life without them would be grizzly.

An oxymoron is a figure of speech that connects two opposing ideas, usually in two-word phrases, to create a contradictory effect.

- open secret

- Alone together

- controlled chaos

- pretty ugly

Common Examples of Figure of Speech in Writing

Writers also use figures of speech in their work as a means of description or developing meaning. Here are some common examples of figures of speech used in writing:

Simile is a figure of speech in which two dissimilar things are compared to each other using the terms “like” or “as.”

- She’s as pretty as a picture.

- I’m pleased as punch.

- He’s strong like an ox.

- You are sly like a fox.

- I’m happy as a clam.

A metaphor is a figure of speech that compares two different things without the use of the terms “like” or “as.”

- He is a fish out of water.

- She is a star in the sky.

- My grandchildren are the flowers of my garden.

- That story is music to my ears.

- Your words are a broken record.

Euphemism is a figure of speech that refers to figurative language designed to replace words or phrases that would otherwise be considered harsh, impolite, or unpleasant.

- Last night , Joe’s grandfather passed away (died).

- She was starting to feel over the hill (old).

- Young adults are curious about the birds and bees (sex).

- I need to powder my nose (go to the bathroom).

- Our company has decided to let you go (fire you).

Personification is a figure of speech that attributes human characteristics to something that is not human.

- I heard the wind whistling.

- The water danced across my window.

- My dog is telling me to start dinner.

- The moon is smiling at me.

- Her alarm hummed in the background.

Writing Figure of Speech

As a literary device, figures of speech enhance the meaning of written and spoken words. In oral communication, figures of speech can clarify, enhance description, and create interesting use of language. In writing, when figures of speech are used effectively, these devices enhance the writer’s ability for description and expression so that readers have a better understanding of what is being conveyed.

It’s important that writers construct effective figures of speech so that the meaning is not lost for the reader. In other words, simple rearrangement or juxtaposition of words is not effective in the way that deliberate wording and phrasing are. For example, the hyperbole “I could eat a horse” is effective in showing great hunger by using figurative language. If a writer tried the hyperbole “I could eat a barn made of licorice,” the figurative language is ineffective and the meaning would be lost for most readers.

Here are some ways that writers benefit from incorporating figures of speech into their work:

Figure of Speech as Artistic Use of Language

Effective use of figures of speech is one of the greatest demonstrations of artistic use of language. Being able to create poetic meaning, comparisons, and expressions with these literary devices is how writers form art with words.

Figure of Speech as Entertainment for Reader

Effective figures of speech often elevate the entertainment value of a literary work for the reader. Many figures of speech invoke humor or provide a sense of irony in ways that literal expressions do not. This can create a greater sense of engagement for the reader when it comes to a literary work.

Figure of Speech as Memorable Experience for Reader

By using effective figures of speech to enhance description and meaning, writers make their works more memorable for readers as an experience. Writers can often share a difficult truth or convey a particular concept through figurative language so that the reader has a greater understanding of the material and one that lasts in memory.

Examples of Figure of Speech in Literature

Works of literature feature innumerable figures of speech that are used as literary devices. These figures of speech add meaning to literature and showcase the power and beauty of figurative language. Here are some examples of figures of speech in well-known literary works:

Example 1: The Great Gatsby (F. Scott Fitzgerald)

In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars.

Fitzgerald makes use of simile here as a figure of speech to compare Gatsby’s party guests to moths. The imagery used by Fitzgerald is one of delicacy and beauty, and creates an ephemeral atmosphere . However, the likening of Gatsby’s guests to moths also reinforces the idea that they are only attracted to the sensation of the parties and that they will depart without having made any true impact or connection. This simile, as a figure of speech, underscores the themes of superficiality and transience in the novel .

Example 2: One Hundred Years of Solitude (Gabriel Garcia Marquez)

Both described at the same time how it was always March there and always Monday, and then they understood that José Arcadio Buendía was not as crazy as the family said, but that he was the only one who had enough lucidity to sense the truth of the fact that time also stumbled and had accidents and could therefore splinter and leave an eternalized fragment in a room.

In this passage, Garcia Marquez utilizes personification as a figure of speech. Time is personified as an entity that “stumbled” and “had accidents.” This is an effective use of figurative language in that this personification of time indicates a level of human frailty that is rarely associated with something so measured. In addition, this is effective in the novel as a figure of speech because time has a great deal of influence on the plot and characters of the story. Personified in this way, the meaning of time in the novel is enhanced to the point that it is a character in and of itself.

Example 3: Fahrenheit 451 (Ray Bradbury)

A book is a loaded gun in the house next door…Who knows who might be the target of the well-read man?

In this passage, Bradbury utilizes metaphor as a figure of speech to compare a book to a loaded gun. This is an effective literary device for this novel because, in the story, books are considered weapons of free thought and possession of them is illegal. Of course, Bradbury is only stating that a book is a loaded gun as a means of figurative, not literal meaning. This metaphor is particularly powerful because the comparison is so unlikely; books are generally not considered to be dangerous weapons. However, the comparison does have a level of logic in the context of the story in which the pursuit of knowledge is weaponized and criminalized.

Related posts:

- Speech: “Is this a dagger which I see before me

- Speech: Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow

Post navigation

- Games, topic printables & more

- The 4 main speech types

- Example speeches

- Commemorative

- Declamation

- Demonstration

- Informative

- Introduction

- Student Council

- Speech topics

- Poems to read aloud

- How to write a speech

- Using props/visual aids

- Acute anxiety help

- Breathing exercises

- Letting go - free e-course

- Using self-hypnosis

- Delivery overview

- 4 modes of delivery

- How to make cue cards

- How to read a speech

- 9 vocal aspects

- Vocal variety

- Diction/articulation

- Pronunciation

- Speaking rate

- How to use pauses

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Voice image

- Voice health

- Public speaking activities and games

- About me/contact

- How to read a poem aloud well

How to read poetry aloud well

- step-by-step help to nail reading a poem .

By: Susan Dugdale

So you want to learn how to read poetry aloud. Good on you. That's great!

And it's probably because you're preparing for a special occasion.

You are going to stand in front of others to deliver the poem you've chosen. Perhaps at a birthday celebration? A wedding? Maybe a funeral? Or a class presentation?

For many people this is totally terrifying.

They're scared they'll stumble over the words, won't understand what the poem is about and, consequently make a complete fool of themselves.

If this is you, relax.

A poem is not a poisonous snake. It will not bite, and you do not have to tip-toe around it.

Learning how to read a poem out loud is relatively straightforward and with practice you may even get to enjoy it!

How to read a poem aloud

Read your poem through silently several times to familiarize yourself with its core ideas and images.

What's the main point of this poem? What's the poet saying? (Can you put that into your own words? Try. It will help you make sense of it.)

Similarly, allow yourself to see the images/scenarios created by the words in your imagination. Likewise feel the emotions.

The more you understand and get inside the poem, the more likely your audience will be able to understand it when you deliver it.

Do you know how each word should be said?

Be sure to look up any unfamiliar words in an online dictionary for their meaning and pronunciation.

How to eat a poem

American poet, Eve Merriam has inspired countless people all over the world to play with poetry by making it accessible and fun.

Try her poem aloud. It's truly delicious!

"Don't be polite. Bite in. Pick it up with your fingers and lick the juice that may run down your chin. It is ready and ripe now, wherever you are.

You do not need a knife or a fork or a spoon or plate or napkin or tablecloth.

For there is no core or stem or rind or pit or seed or skin to throw away."

Find more about Eve Merriam here.

Read your chosen poem quietly aloud to yourself following the guidelines given by the punctuation, listening for its musicality or beat.

If you need them, there are tips for interpreting punctuation here.

Read slowly . Allow each word its space. The temptation is to rush. Resist it.

Once you've 'got the flow' of it, stand up and read the poem aloud authoritatively.

Now that you're more confident 'play' with your delivery, experimenting with vocal variety.

For example, what happens if you stress this word rather than that word? Does it change the meaning? How?

Say your poem as many ways as you can.

Say it loud. Say it soft. Say it gathering speed, getting faster and faster. Say it slow and low. Say it with a silly accent.

In short, have fun with it. Experiment! And record what you do.

When you play the recordings back, you'll find some of the ways you've tried will sound much better than others. Take the ways that work, blend them and try again.

Poems are very forgiving. You can flub the words and mangle the meaning but they will not break.

5 different readings of How to eat a poem

To illustrate how a poem is said alters how it's experienced by those listening to it, I recorded Eve Merriam's poem 'How to eat a poem' five different ways.

- You can hear it fast: ' How to eat a poem' read quickly

- You can hear it slow: ' How to eat a poem' read slowly

- You can hear it with heavy stresses or emphasis on various random words: ' How to eat a poem' read with stressed words

- You can hear it whispered: ' How to eat a poem' read in a whisper

- And lastly, you can hear it as I might deliver it to an audience: ' How to eat a poem '

Click the link to find out more about playing with vocal variety : the way you say words.

Rehearsal and feedback

Read your poem in front of several friends before going 'live'. Have them give you feedback on:

- clarity Could they hear and understand your words?

- meaning Did they understand the images and feelings of the poem? Could they follow the story, or the poet's intent?

- speaking rate Were you speaking too fast or too slowly?

- voice Too loud, too soft, too high, too low...

- body language/gesture and stance Was it expressive, effective, and appropriate? Or too much? Or too little?

- notes - how they were handled Did you have a copy of your poem on a stand in front of you? Was it on your phone? Did you manage reading from whatever device it was on effectively? Was there eye contact with the audience? Or were you reading head down for the entire time?

Incorporate their feedback and then present your poem.

Extra tips on reading poetry aloud

- Y ou do not need a 'dramatic' voice to be successful. An assumed voice, one other than your own, will seem artificial and strained. When you 'act' or 'perform', rather than read, you make yourself the center of attention and the integrity of the poem is compromised.

- Remember to breathe. Holding your breath heightens tension, which in turn heightens the tone of your voice.

- U se the natural pauses in the poem to take a breath, for example on a comma, full stop or period.

- If the occasion is emotional for example, the poem is part of eulogy, wedding or retirement speech, print it out in a large clear font so it is easily read. Marking the pauses, breath or stress points using a highlighter, will also help you remember what you rehearsed.

- Stand tall and relaxed, just as you would for delivering a speech.

- And just in case you need them, here's tips for managing public speaking anxiety and some good breathing exercises .

Reading poetry aloud is a gift

The ability to read poetry aloud is a gift of immense value.

Because the right poem, read well, expresses with grace and clarity thoughts and feelings that are often difficult to find appropriate words for in ordinary, everyday conversation.

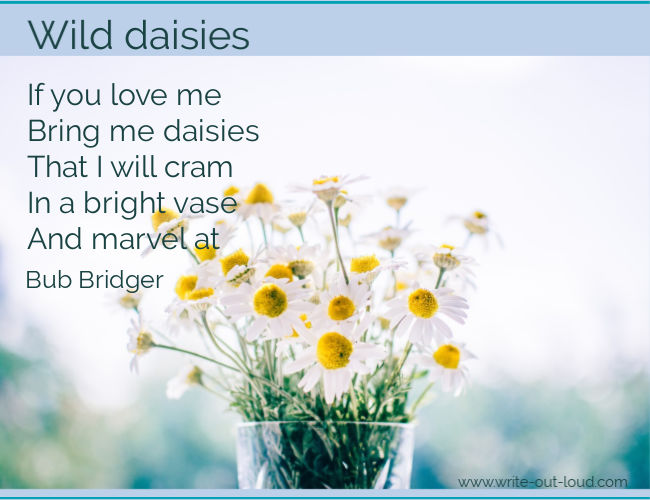

For instance I recently read this beautiful Bub Bridger poem - Wild Daisies at my niece's wedding. (See the excerpt below. This is the last segment of the poem.)

If you're wanting a reading about love that is both simple and profound do take a look. At the reception I got numerous compliments for choosing the poem and for the way I delivered it. Sadly, I could only accept half of them - those about its reading as Ruth, my niece, selected it.

(What great taste she has! ☺)

Would you like to listen to some poems?

You'll hear me, Susan, reading them. There are two collections of poems for funerals.

I recorded these to help people searching for a poem to read as part of a service. Hearing, as well as reading them, makes it easier to decide whether a poem fits their needs.

- I am Standing Upon the Seashore

- Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep

- Funeral Blues

- Prayer of St. Francis of Assisi

All four are popular choices.

You'll find them on this page: funeral poem readings .

Readings of 4 'Remember Me' funeral poems

You'll find the text of each poem, along with an interpretation, (a guide to its meaning), audio, and a printable, here: Funeral poems: Remember Me .

Readings of much-loved children's poems

There are also recordings of 6 much-loved children's nonsense poems. You'll find those here, along with activity suggestions and printables: poems for kids

Or perhaps you'd like to write and read a poem of your own?

It's not as difficult as you may think to craft something original and special. The result may not be award winning! However, that's not the aim of the exercise. If your wish is to express your thoughts and feelings uniquely, you can.

Find out here how to write a poem in free verse.

Related poetry pages you may enjoy:

- a large selection of timeless, cross-cultural poems for funerals