COVID-19 Lockdown: My Experience

When the lockdown started, I was ecstatic. My final year of school had finished early, exams were cancelled, the sun was shining. I was happy, and confident I would be OK. After all, how hard could staying at home possibly be? After a while, the reality of the situation started to sink in.

The novelty of being at home wore off and I started to struggle. I suffered from regular panic attacks, frozen on the floor in my room, unable to move or speak. I had nightmares most nights, and struggled to sleep. It was as if I was stuck, trapped in my house and in my own head. I didn't know how to cope.

However, over time, I found ways to deal with the pressure. I realised that lockdown gave me more time to the things I loved, hobbies that had been previously swamped by schoolwork. I started baking, drawing and writing again, and felt free for the first time in months. I had forgotten how good it felt to be creative. I started spending more time with my family. I hadn't realised how much I had missed them.

Almost a month later, I feel so much better. I understand how difficult this must be, but it's important to remember that none of us is alone. No matter how scared, or trapped, or alone you feel, things can only get better. Take time to revisit the things you love, and remember that all of this will eventually pass. All we can do right now is stay at home, look after ourselves and our loved ones, and look forward to a better future.

View the discussion thread.

Related Stories

Looking back on lockdown days

Art class and self care during the pandemic

We'll Walk Together

A Race to What Finish Line

C 2019 Voices of Youth. All Rights Reserved.

- < Previous

Home > History Community Special Collections > Remembering COVID-19 Community Archive > Community Reflections > 21

Community Reflections

My life experience during the covid-19 pandemic.

Melissa Blanco Follow

Document Type

Class Assignment

Publication Date

Affiliation with sacred heart university.

Undergraduate, Class of 2024

My content explains what my life was like during the last seven months of the Covid-19 pandemic and how it affected my life both positively and negatively. It also explains what it was like when I graduated from High School and how I want the future generations to remember the Class of 2020.

Class assignment, Western Civilization (Dr. Marino).

Recommended Citation

Blanco, Melissa, "My Life Experience During the Covid-19 Pandemic" (2020). Community Reflections . 21. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/covid19-reflections/21

Creative Commons License

Since September 23, 2020

Included in

Higher Education Commons , Virus Diseases Commons

To view the content in your browser, please download Adobe Reader or, alternately, you may Download the file to your hard drive.

NOTE: The latest versions of Adobe Reader do not support viewing PDF files within Firefox on Mac OS and if you are using a modern (Intel) Mac, there is no official plugin for viewing PDF files within the browser window.

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Expert Gallery

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- SelectedWorks Faculty Guidelines

- DigitalCommons@SHU: Nuts & Bolts, Policies & Procedures

- Sacred Heart University Library

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Biden might actually do something about ludicrously expensive concert tickets

Caitlin Clark’s staggeringly low starting salary, briefly explained

January 6 insurrectionists had a great day in the Supreme Court today

Tucker Carlson went after Israel — and his fellow conservatives are furious

The dairy industry really, really doesn’t want you to say “bird flu in cows”

Why the case at the center of Netflix’s What Jennifer Did isn’t over yet

Lockdown diaries: the everyday voices of the coronavirus pandemic

Senior Lecturer in Social Science, Swansea University

Disclosure statement

Michael Ward does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Swansea University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A diary is by its very nature an intensely personal thing. It’s a place to record our most intimate thoughts and worries about the world around us. In other words, it is a glimpse at our state of mind.

Now, the coronavirus pandemic, and the impact of the lockdown, have left many people isolated and scared about what the future might bring. As a sociologist, I was keen to hear how people were experiencing this totally new way of life. So in early March I began the CoronaDiaries – a sociological study which aimed to highlight the real voices and the everyday experiences of the pandemic by collecting the accounts of people up and down the UK, before, during and after the crisis.

From the frontline health worker concerned about PPE and exposure to COVID-19, to the furloughed engineer worried about his mental health, these are the voices of the pandemic. Entries take a variety of forms, such as handwritten or word-processed diaries, blogs, social media posts, photos, videos, memes and other submissions like songs, poems, shopping lists, dream logs and artwork. So far, the study has recruited 164 participants, from 12 countries, aged between 11 and 87. These people come from a range of backgrounds.

This article is part of Conversation Insights The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

When I began this project in March, I did not expect the study to prove so popular. I have been studying and working as a sociologist for nearly 20 years and most of my research so far has looked at how young men experience education, gender roles and social inequality.

Like many of us, I was wondering how I could be of use at this time, do my bit in the crisis and make the most of my skills. As the weeks have gone by and more and more people have signed up, I’ve realised this project isn’t just a research study to understand how society is being made and remade – it is also providing hope and acting as a cathartic coping tool for people. While some of the documents have made me cry, especially those from already vulnerable people, others have made me laugh and have been a joy to read. I feel as though I am on a journey with the participants as we move through the crisis.

Reading the entries, what becomes clear as the lockdown is eased is that this pandemic has been – and will continue to be – experienced in very different ways across society. For some, the crisis has been an opportunity, but for others, who are already in a disadvantaged position, it is a very frightening experience.

March – first days

The frontline health worker

Emma is in her late 30s, and a frontline health worker in a rural location in Wales. Like many key workers, Emma is also juggling family life and caring responsibilities. In a diary entry written in mid-march, Emma foresaw issues with PPE in the NHS.

On my shifts over the previous weekend, it became apparent how unprepared we are. I was working on a ‘clean’ ward and four of the patients were found to potentially be infected. There were no clinical indications they were potentially infected on admission and had been nursed without PPE for two days. We may have all been exposed, as these patients are suspected to have COVID-19. We have been given bare bones PPE. It was quite sobering when a rapid response was called and the doctors refused to enter the cubicle without FFP3 masks , blue gown and visor.

Emma said the equipment “magically turned up” after the doctors took this stand but said the sight of them all in surgical gowns, helmets and visors “did verge on the ridiculous”. She added:

I did find it amusing – we’re looking at the doctors wanting their protection and they are looking at the consultant wanting his! It did feel like a farce. Fortunately, the patient was made stable and went to surgery for another issue. But the whole episode was worrying, particularly the crappy surgical mask and aprons we are provided. It’s also galling that they have told staff there is no PPE when clearly there is. Can’t help but think a lack of information is creating fear amongst staff. It’s also weird they aren’t testing staff unless they’re symptomatic. This is crazy when they are so dependent on bank and agency workers who move around.

The worried mum

Beth, 35, is a mother of two young children who lives in a busy city. In the early days of the crisis, she hid her fears from her children. Here is a snapshot from her written diary:

I didn’t sleep well last night, didn’t help I watched the news before going to sleep. Then looked at my phone and full of corona news … Today was the big announcement from Boris (Friday, March 20) ‘to stay in’! Even though he had been saying this all week, the tone and manner of the broadcast was so scary and serious. I felt scared for my family and it just made me fearful of what is to come. I rang my mum straight away … [she] could hear my fear. After a good chat … my mum … remind[ed] me ‘we are all well at this moment’ and to focus on that. My daughter cried later that evening. I said, ‘what are you scared of’ to which she replied, ‘I’m not sure mummy, I don’t know what I am scared of.’ Which made me realise that I need to be brave and make sure that both kids are reassured. Later that evening, I felt tearful and just feeling overwhelmed by the whole situation. How stupid too, because we are all safe.

Read more: How to help with school at home: don't talk like a teacher

The student

Audrey, 21, goes to a university in Birmingham and is in the final months of her degree. The rupture of “normal” student life became clear when the full scale of the lockdown came into force, causing her housemates to leave their shared house.

I’d just lost all three of my housemates, who’d returned to Barbados, Spain and France – literally one day after each other. My landlord really kindly agreed that my sister could stay with me – and she won’t even charge any rent. I almost cried when I got that message. I was having a facetime with my friend, where we paused to watch Boris Johnson’s speech (March 23). It was so scary because we were effectively in lockdown. I had told my sister that I thought it was about to happen earlier in the day, she didn’t believe me – and then unfortunately it came true! I told her to jump on the train from Manchester.

Audrey went on to write how some of her fellow students set up a food bank in one of the student accommodations near her and that she is determined help where she can. But despite her altruistic efforts, the lockdown was still taking its toll.

I feel deflated from everything. I chatted to a friend over Messenger and she suggested I paint something. I painted this rainbow and felt so much better at the end. I added in my favourite quote that gets [me] through any hard times and stuck it on the window.

April – settling in

The cleaner

Eva is a self-employed cleaner, in her mid 50s, who lives in South Wales with her husband, John, who works in a factory making hand sanitiser. As the lockdown entered its second month, she reflected on her relationship with the woman who worked for her and how differently the pandemic was effecting them both.

Today I am cleaning the community centre, which since the lockdown, is running as a food bank three days a week … I bleach everything, door handles, floors, everything. Most staff work from home at the moment so we are going in the morning until all this is over. I’m glad I’m still in business for Beverly, who works with me, as much as anything. I’m her only income, but if I don’t work, I don’t get paid. We have a cigarette break outside and I remind Beverly to stay apart. ‘What, beans for brekkie, was it?’ I laugh. Beverly really doesn’t care about COVID – like many others I meet, who believe if they get it, they get it.

For once I’m glad I’m a worrier, plus I’m not ready to die yet. We are out of there early as no staff equals less mess. I break it to Beverly that I can’t give her a lift home for now. Last week I made her sit in the back [of the car] which felt faintly ridiculous, but John advised even that’s too close. Beverly shrugs and says that’s fine. Her son died unexpectedly two years ago and now she accepts hardship with ease. I feel bad as her life really is crap and now she has to walk two miles home.

The teacher

Sophia is a teacher in her 40s and based in the south of England. She is trying to home school her children during the lockdown and being a parent and a teacher is proving challenging.

We began the day slightly differently with an online PE lesson from someone called Joe Wicks, or The Body Coach. He’s been really popular during the lockdown and a few of my friends recommended the 30-minute workout session he does every day at 9am, so I thought we’d give it a go! Unfortunately, my two have the concentration spans of goldfish so it didn’t go according to plan! My son ended up lying upside down, with his legs on a chair and his head on the floor and my daughter said he moved too fast, before promptly falling on her behind! The only problem with changing the routine was that we were then 30 minutes late for home school and my son does not cope well with change. He needs quite a rigid structure, with clearly defined timings and any changes can be detrimental. The speed of the school lockdown was particularly challenging: school gives his day structure and taking it away so abruptly was very difficult for him.

The civil servant

Sarah is a civil servant in her mid-60s working in a pivotal role for HM Revenue and Customs. She used her diary to document the rapid changes which have taken place in her organisation since the lockdown and how working from home was becoming “normal” from March 23.

My department is changing so quickly – we have introduced a new i-form to promote more ‘web chat’. This is proving popular with the public. We are trialling taking incoming telephone calls at home. We are all now working from home when we can, no more car sharing, unless it’s with someone you live with – we must keep two metres apart. I am beginning to accept that this is a crisis, once in a generation, completely alien to us. Will life in the future be remembered as ‘before and after’ COVID-19? For the first time in many years I feel so proud to work where I do…I understand, possibly for the first time, why we are ‘key workers’. We have a letter as proof to show the police if we are ever stopped whilst travelling into work and NCP carparks are free for us to use if we come into work! No better validation than that!

The furloughed engineer

Lucas, a man in his late 30s from Northern Ireland, is finding the pandemic difficult on multiple levels. It’s a trigger for his mental health, but also it is a reminder of past troubles.

Nightmare. Anxiety, fear, dread, no way to burn off the angst, worry upon worry, like how the inside of my head can be at times. Then there’s the ones that are really in the middle of it, nurses dying because there was no proper PPE at the right time, people losing parents, friends, and IMHO worst of all, kids.

Lucas writes about how he stopped watching the news because in an attempt to “avoid anxiety”. He adds:

I grew up in Northern Ireland during ‘the troubles’ and it was totally normal for me to watch the news every night at tea time [6pm] and hear of various paramilitary groups killing people. That was 100% normal to me. Looking back watching the news in those times did me no good. Sure, I know some facts about it all, but do I feel any better for it … Same as now, I’m going to try to ride this out with my hands over my ears and my head in the sand at times.

Read more: Coronavirus: a growing number of people are avoiding news

The academic

Jack, 72, is a retired academic who used his diary to comment on societal problems. One of which is the narrative of what the “new normal” is and how society is being remade.

April 29 saw the return of Boris, who was to ‘take control of the problem’. An almost religious return for someone who came back from being nearly dead on Easter Sunday! It seems we are being told to be ready for the new normal which again raises the issue of what post-lockdown will be like. On the web I don’t see sociologists rushing in to think about this new normal! A Google search suggests that the new normal is being constructed largely by those in business and is largely focused on the new normal being a more exaggerated (and better?) version of the old normal – more globalisation, more focus on customers and so on. There is little ‘thinking outside the box’.

Read more: What will the world be like after coronavirus? Four possible futures

May – Looking forward

The bell-ringer

Daniel, a man in his mid-20s, had just started a new relationship in February with a woman he met while bell-ringing at a church in the Midlands. However, both he and his girlfriend live apart and have not seen each other since the lockdown began. Over the past few months, Daniel has found this a challenge, but has documented how their relationship has been maintained virtually and through the help of keeping a diary.

Suzy and I have got to know each other a lot quicker and a lot better than what we may have done otherwise, and whilst we do miss each other immensely, it’ll make the good times so much better when we do see each other next. Whenever and however we get out of this, I am determined that I will have made the most of these extraordinary circumstances.

This is just a glimpse of the stories that have been gathered by the CoronaDiaries project, but already patterns are emerging. While this crisis is undoubtedly impacting on people across the globe, what is clear from these accounts is that there are multiple crises across everyday life – for the young, the old, for mothers and for fathers and for those from different class, gender and ethnic backgrounds. These entries are able to highlight the multiple different lives behind the dreaded numbers we hear announced each day.

My diarists have been recording how they feel vulnerable and uncertain about their future – but there is also hope that things will not be like this forever.

The evidence which is being gathered here can play an important part in addressing the social, political and economic changes created by the COVID-19 pandemic. This type of analysis will foster global awareness of crucial issues that can help support specific public health responses to better control future outbreaks and to better prepare people for future problems. The study will run until September and all accounts will then be available to view in a free digital online archive.

All the names used in this piece have been changed at the request of the study participants.

For you: more from our Insights series :

Lockdown lessons from the history of solitude

What will the world be like after coronavirus? Four possible futures

The end of the world: a history of how a silent cosmos led humans to fear the worst

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter .

- Mental health

- Coronavirus

- Social science research

- Insights series

- Coronavirus insights

- COVID-19 lockdowns

Senior Enrolment Advisor

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Positive and negative experiences of living in covid-19 pandemic: analysis of italian adolescents’ narratives.

- Department of Education, Languages, Intercultures, Literatures and Psychology, University of Florence, Firenze, Italy

Introduction: Despite a growing interest in the field, scarce narrative studies have delved into adolescents’ psychological experiences related to global emergencies caused by infective diseases. The present study aims to investigate adolescents’ narratives on positive and negative experiences related to COVID-19.

Methods: Italian adolescents, 2,758 (females = 74.8%, mean age = 16.64, SD = 1.43), completed two narrative tasks on their most negative and positive experiences during the COVID-19 emergency. Data were analyzed by modeling an analysis of emergent themes.

Results: “Staying home as a limitation of autonomy,” “School as an educational, not relational environment,” the impact of a “new life routine,” and experiencing “anguish and loss” are the four emergent themes for negative experiences. As for positive experiences, the four themes were “Being part of an extraordinary experience,” “Discovering oneself,” “Re-discovering family,” and “Sharing life at a distance.”

Conclusion: Authors discuss the impact of COVID-19 on adolescents’ developmental tasks, such as identity processes and autonomy acquisition.

Introduction

After the first case of COVID-19 in Italy was discovered on the 21st of February, schools and universities were shut down on March 5. On the March 9, the government declared lockdown status in order to hinder the spread of the virus. In order to reduce contagion, citizens were required to stay home except for emergencies and primary needs. Over 8 million children and adolescents stopped their social and educational activities, which were reorganized online. On April 5, the last day of data collection for the present study, out of a global number of 1,133,758 ( Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, 2020 ), 128,948 people had been infected by COVID-19 in Italy, of which 15,887 (about the 12.3%) had died ( Italian Ministry of Health, 2020 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic is a public health emergency that poses questions and dilemmas regarding the psychological well-being of people at varying levels.

Currently, several studies have been conducted on how the general population experiences emergencies related to pandemic infectious diseases. Some authors ( Yeung and Fung, 2007 ; Dodgson et al., 2010 ; Peng et al., 2010 ; Main et al., 2011 ; Van Bortel et al., 2016 ), in analyzing the impact of infectious diseases such as SARS or Ebola, report experiences such as fear and anxiety for themselves and their families, separation anxieties, impotence, depression, as well as anger and frustration. In the case of COVID-19, scholars have highlighted several psychological effects of the pandemic on adult samples in China ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a , b ) and in Italy ( Rossi et al., 2020 ), and found psychological symptoms related to posttraumatic stress disorder. In a recent review, anxiety, depression, psychological stress, and poor sleep have been reported to be the main psychological outcomes of living with the COVID-19 emergency ( Rajkumar, 2020 ).

Considering children and adolescents, several studies have specifically explored psychological experiences related to the global emergency and lockdown experience of COVID-19 ( Lee, 2020 ), but evidence from autobiographical narratives are lacking. Qiu et al. (2020) compared different Chinese aged populations and found lower levels of psychological distress in people under 18. Similarly, Xie et al. (2020) found symptoms of anxiety (18.9%) and depression (22.6%) in primary school children in China.

As for US adolescents, evidence suggests that social trust and greater attitudes toward the severity of COVID-19 are related with more adolescents’ monitoring risk behaviors, performing social distancing, and disinfecting properly. Motivation to perform social distancing is also associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression ( Oosterhoff et al., 2020 ).

A study on Canadian adolescents’ well-being and psychiatric symptoms highlighted that depression and feelings of loneliness are related with great time spent on social media, while family time, physical activity, and schoolwork play a protective role for depression ( Ellis et al., 2020 ). Similarly, in a recent review of adolescents’ experience of lockdown for COVID-19, Guessoum et al. (2020) discuss the relation between the current pandemic and adolescents’ posttraumatic stress, depressive, and anxiety disorders, as well as grief-related symptoms. Furthermore, they found that data on adolescent mental health are still scarce and need to be empowered.

Adolescence is connected to certain developmental tasks ( Havighurst, 1948 ) related, among others, to defining one’s own personal identity ( Kroger and Marcia, 2011 ) and developing one’s autonomy by redefining family ties and building bonds with peers ( Alonso-Stuyck et al., 2018 ).

Considering identity changes, adolescence is characterized by a developmental crisis between the definition of a personal identity and a status of confusion of roles ( Erikson, 1968 ). Adolescents’ ego growth is linked to the separation from childhood identifications in order to allow an individual identity status to emerge. This gradual process is connected with four different styles of identity definition concerning vocational, ideological, and sexual issues ( Kroger et al., 2010 ): identity achievements, moratorium, foreclosure, and diffusion. Overall, the identity process may develop from a period of diffusion, not connected to significant identifications, or with foreclosure, in which identifications are still related to significant childhood figures. The opportunity to explore new relationships with peers and other developmental environments often stresses a time of identity moratorium where individuals investigate themselves by making identity-defining commitments, which usually end by achieving a balance between personal interests and the vocational and ideological opportunities provided by surrounding context.

A turning point in identity development is the acquisition of personal autonomy. Scholars define autonomy as a multidimensional variable related to a set of phenomena involved in psychosocial development: the separation-individuation task as reported by Erikson (1968) , management of detachment, and independence from family in order to look for new developmental environments, psychosocial maturity, self-regulation, self-control, self-efficacy, self-determination, and decision making ( Noom et al., 2001 ).

The main theories on autonomy acquisition during adolescence stress the relation between the desire for autonomy and the development of beliefs about personal capabilities, the need to explore one’s own life goals and reflect on personal desires and preferences. As teenagers gain self-confidence and focus on personal goals and attitudes related to their individual interests and talents, the demand for autonomy in the household increases ( Van Petegem et al., 2013 ). At the same time, intimate relationships with peers in adolescence acquire a vital importance for the definition of autonomous and personal identity. Adolescent friendships represent the possibility of strengthening the completion of the process of identification through establishing relationships with significant others ( Jones et al., 2014 ).

As a privileged context of peer interaction and acquisition of knowledge and personal maturity, school greatly contributes to the development of adolescent identity and interpersonal relationships ( Lannegrand-Willems and Bosma, 2006 ). Both curricular and extracurricular activities at school promote interpersonal interactions, and adolescents’ participation in school activities may have a protective role for academic achievement, substance use, sexual activity, psychological adjustment, delinquency, and young adult outcomes ( Feldman and Matjasko, 2005 ).

During the COVID-19 emergency and the consequent lockdown in Italy, adolescents experienced a strong change in their personal and social environment, which could have affected the trajectory of their developmental tasks. Nevertheless, currently, there is a lack of knowledge of adolescents’ experience of living with COVID-19 and the main psychological issues related to it. Lockdown and the consequent closing of schools ushered in a new life routine for adolescents, centered on sharing time with family and temporarily interrupting face-to-face peer relationships. In this sense, similar to others, very impacting autobiographical events such as diseases or natural disasters, lockdown, and pandemic might have caused a biographical disruption ( Bury, 1982 ; Tuohy and Stephens, 2012 ) interrupting developmental tasks typical of adolescence or forcing a reorganization. To understand the subjective experience of Italian adolescents and the potential impact of the biographical disruption on developmental tasks, we asked them the most impacting experiences related to COVID-19 and the national lockdown. We therefore collected narratives of positive and negative autobiographical events. Our main hypothesis was that the imposed lockdown may have constituted a turning point of pivotal developmental processes of autonomy acquisition and identity development, forcing adolescents to re-organize their personal resources. Therefore, we aimed to explore how Italian adolescents dealt with this peculiar life experience in terms of managing their developmental tasks.

Considering the lack of knowledge in literature and the need to investigate an unexplored topic, we performed a qualitative study to explore adolescents’ feelings and thoughts by means of their narratives. Qualitative research design helps “to generate useful knowledge about health and illness, from individual perceptions to how global systems work” ( Green and Thorogood, 2018 , p. 6) allowing for deep knowledge. Furthermore, narrative is a recognized tool to explore autobiographical experiences in terms of thoughts, emotions, and feelings as well as an intervention to promote emotional elaboration and meaning making ( Pennebaker, 1997 ; Pennebaker et al., 2003 ). As a natural act to elaborate life episodes and generate meanings ( Bruner, 1990 ), narrative enriches the search for evidence on autobiographical experience especially in both normative and not normative life transitions, when the need for meaning making about the self is strong. For this reason, the research design was exploratory, and it was caused by the need to generate insights on adolescence and COVID-19 starting from the direct adolescents’ narrated experience.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Participants of the present study were part of a broader study involving 5,295 Italian adolescents (mean age = 16.67, SD = 1.43; females = 75.2%; Min = 14, Max = 20) exploring emotional and cognitive patterns involved in COVID-19 experience. Since 14 is the Italian minimum age to give individual consent to having one’s online data processed, inclusion criteria for the present study were to be high school students and to be aged between 14 and 20. From the whole sample, we did not include data about adolescents with any missing data on either narrative task.

The final sample of 2,758 adolescents (females = 74.8%; mean age = 16.64, SD = 1.43; min = 14, max = 20; 14 years old = 7%, 15 years old = 17%, 16 years old = 22.4%, 17 years old = 22.2%, 18 years old = 23.2%, 19 years old = 6.3%, 20 years old = 1.9%) was composed by students attending lyceums (76.9%), technical high schools (16.9%), and vocational high schools (5.5%). Participants came from all regions of Italy: considering the impact of COVID-19 spread in Italy during data collection, the 16.8% of participants came from Lombardy (the most impacted region), the 20.7% came from medium impacted regions (Emilia Romagna, Liguria, Marche, Piedmont, Trentino Alto-Adige, Valle d’Aosta, Veneto), and the 62.5% came from other Italian region less impacted. Overall, 2,464 of them reported and narrated their most negative experiences and 2,110 reported their most positive experiences.

We also collected data about personal experiences involving COVID-19. Of the sample, 7.8% experienced a COVID-19 infection within the family circle (e.g., parents, brothers/sisters, grandparents, etc.). Of the sample, 38.6% experienced COVID-19 infections within friendship, scholastic, or broader social circles (e.g., neighbors, acquaintances). Ten participants (0.4%) reported to be infected themselves.

Procedures and Data Analyses

After the approval of the ethical committee of the University of Florence, data collection took place from April 1 to April 5, 2020, during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy, through a popular student website for sharing notes and receiving help with homework 1 , via a pop-up window asking the users to take part in the study. All respondents provided explicit informed consent at the beginning of the survey. It was possible to leave the survey at any point by simply closing the pop-up window. All data collected were anonymous. The contacts of a national helpline (i.e., telephone number and website chat) were provided at the end of the survey, inviting participants to get in touch if they need psychological support.

We invited participants to fill in two narrative tasks: the first on their most negative experience (“ Please, think about your memories surrounding COVID-19 and the “quarantine”. Would you please tell us your most negative experience during the last two weeks? Take your time and narrate what happened and how you experienced it. There are no limits of time and space for your narrative” ) and a second about their most positive experience of life during COVID-19 pandemic (“ Referring again to your memories surrounding COVID-19 and the “quarantine”, would you please tell us your most positive experience of the last two weeks? Please, narrate what happened and how you experienced that episode. There are no limits of time and space for your narrative” ).

The time frame of 2 weeks was referred to time approximately spent between the beginning of lockdown (March 9) and data collection.

All narratives were joined in two different full texts, one for the positive experience narratives and one for the negative ones. Then, a modeling emergent themes analysis was run by the T-Lab Software ( Lancia, 2004 ). Modeling of Emergent Themes discovers, examines, and extrapolates the main themes (or topics) emerging from the text by means of co-occurrence patterns of key-term analysis by a probabilistic model, which uses the Latent Dirichlet Allocation ( Blei et al., 2003 ). The results of the data analysis are several themes describing the main contents of a textual corpus. Researchers discussed in groups emergent themes and selected from elementary contexts derived from analysis those better explaining each theme.

This kind of textual analysis is therefore suggested in studies aiming to deepen unexplored topics in order to identify variables related to a specific kind of experience to be further investigated upon ( Cortini and Tria, 2014 ).

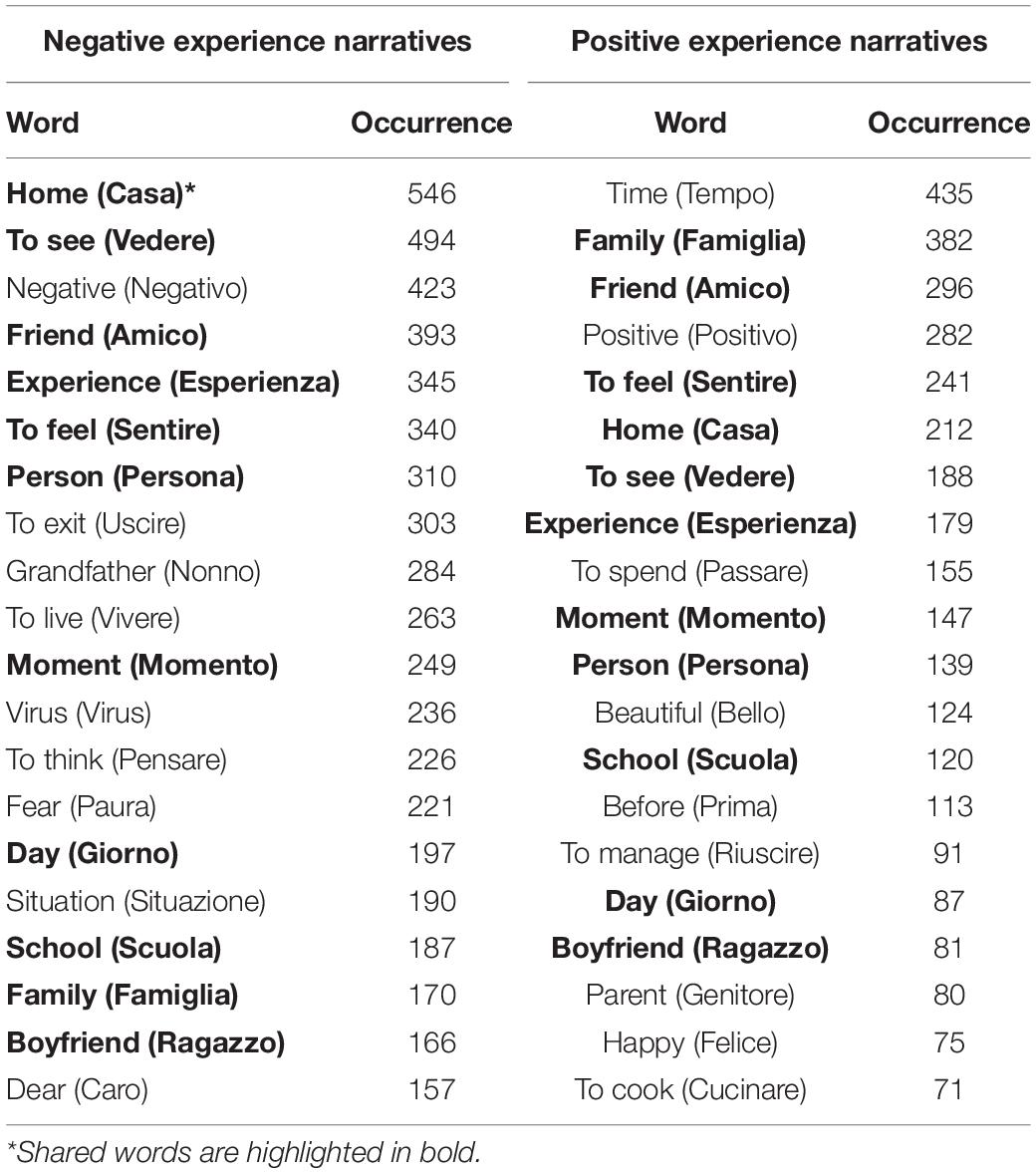

First, the total word count of both narratives by the participants were analyzed. Adolescents’ negative experience narratives were composed of 76,007 words, with a mean number of 30.84 words per narrative, while 38,452 was the number of words used to narrate the most positive experiences (with a mean of 18.22 words per narrative collected). Table 1 shows the words mostly reported in the two texts.

Table 1. The occurrence of the most reported 20 words both for positive and negative experience narratives.

Looking at word occurrence in the two texts (positive and negative experience), many communalities emerged. Among the 20 most cited words in both texts there are: “Home,” “To See,” “Experience,” “Friend,” “To feel,” “Moment,” “Person,” “School,” “Day,” “Boyfriend,” and “Family.” Overall, 11 words out of 20 are shared between the vocabulary of the two collected narratives.

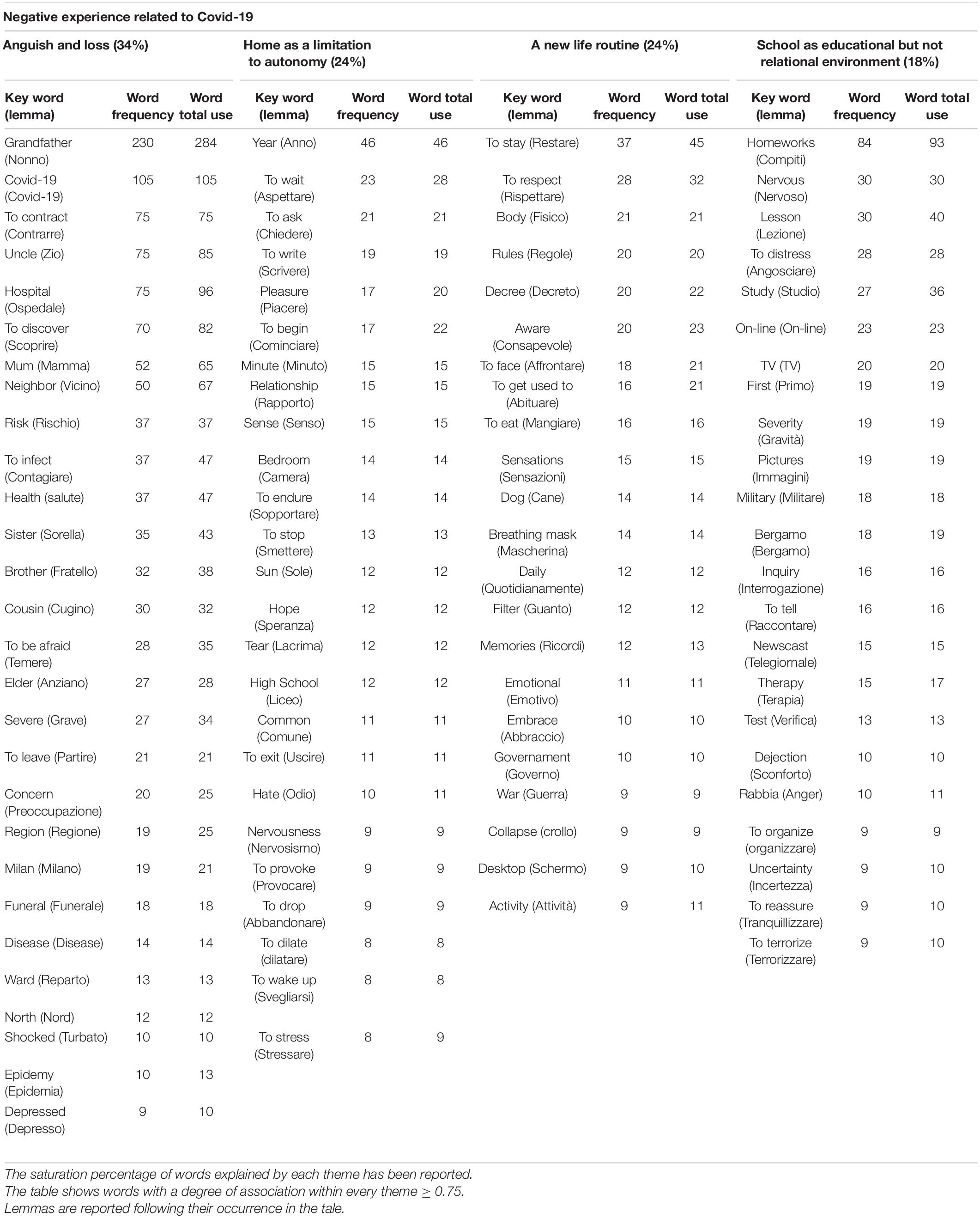

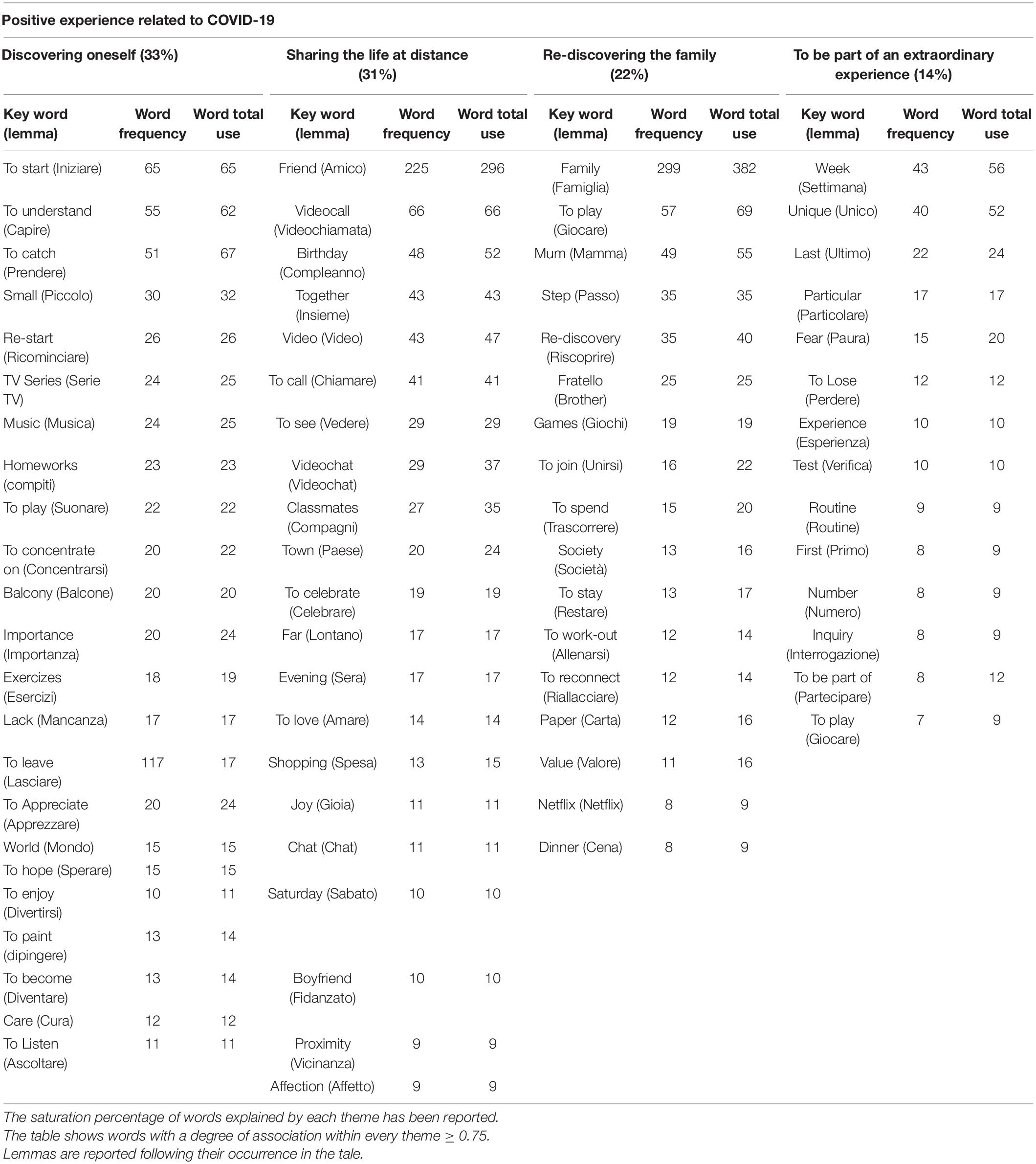

Looking at the modeling emergent themes analysis, The T-Lab software revealed four themes for each text. Tables 2 , 3 summarize the emergent themes and the main words associated with each of them.

Table 2. Themes of negative experience narratives and main words for each of them.

Table 3. Themes of positive experience narratives and specific words for each of them.

Negative Experiences Narratives

For negative experiences narratives, the first and most representative theme concerned feelings of “Anguish and Loss” and was explained by 34% of lemmas. Adolescents shared their anguish for having lost physical and emotional contact with relatives due to quarantine: “I went to my grandmother’s house because she lives next door. I went to hug her and she pushed me away as if I stank, it was so ugly, I felt like a stranger” (Participant n. 1070, male 17 years old) . In this narrative, social distancing acquired the meaning of loss of intimacy in close relationships; other adolescents narrated their anguish for their parents’ and relatives’ health due to the spread of COVID-19. One participant wrote: “When I heard that both my parents were going to have to go back to work, I got very scared, and I’m still scared for their health. We have a lot of friends who are sick, some are dead and we couldn’t even say goodbye to them” (Participant n. 1234, male 16 years old).

The inability to say goodbye to relatives and friends and to experience contact with their deaths is a frequent issue in collected narratives. As shared by a female participant, grief is a process hindered by the inability to experience loss directly: “The most negative experience I had was the death of my grandfather, who died after contracting COVID-19. You will think that I’m only talking about the loss itself, but actually difficulties came later. Not because there were people crying at the funeral and I had to show myself strong in front of my parents; not because when I went to his house I couldn’t find him; not because I won’t get to be spoiled by him just like every other granddaughter is by her grandfather; but because I had to undergo this process with just my mind. I had to imagine a funeral, I had to imagine him, pale and cold, in the coffin and try to feel the dampness of the tears on my cheeks at the moment of burial. There was nothing to help me metabolize the death, to make it happen in my mind. I’m usually a crybaby, but when they told me that my grandfather died I cried only once. When I think about it I feel guilty for how insensitive I’ve been, but he’s still there for me, when I think of him I see him alive. I tried to kill him with my thoughts because that’s the reality, but how hard is it to understand someone’s death when you don’t face it? When you don’t live it?” (Participant n. 23, female 16 years old) .

The second theme explained 24% of lemmas and it was labeled “Home as a limitation to autonomy.” Participants narrated their experience of feeling a limitation to their personal autonomy in daily life activities.

A female participant narrated: “Staying at home brings me moments of nervousness and I’m easily irritable. I often have panic attacks, precisely because staying at home for so long is not good for me. One feels alone, like in a cage and suffocated feelings give rise to nervousness that causes tension” (Participant n. 645, female 16 years old). Similarly, the following narrative introduces the difficulty of finding a personal space to give voice to individual needs at home: “It’s very hard for me to concentrate and I can’t stand spending 24 hours a day with my parents arguing. I don’t even have my own bedroom, because the door is missing so I have to be with them all the time. Personally, I’m not afraid of the virus, there have always been cases in history and of course we have always come out of it unscathed; the point is that I just want to go back to having the chance to be away from home, for example at school and possibly soon at university” (Participant n. 2185, female 18 years old) . The two negative experiences suggested adolescents’ perception of living with COVID-19 as a time to forcibly lose their personal autonomy.

Another male adolescent shared the sensation of being in prison as the result of having lost an individual identity related to a state of suspension of personal desires and identity: “It’s bad to wake up in the morning knowing you can’t accomplish anything with your life, you can’t do anything. I look out the window and it’s all deserted, no more sounds of cars, buses or people talking. It’s like a changed world, it’s like being in prison for something that’s not your fault. All I can do is wait and stay at home.” (Participant n. 1460, 16 years old).

The third theme, saturating by 24% of lemmas, concerned the impact of “A new life routine.” Adolescents narrated their contact with life in quarantine as well as social distancing. Participant n. 488, a 17-year-old male, narrated his most negative experience of not recognizing his best friend because of the mask: “The worst experience I had was when I went out for the first time to go shopping, wearing a mask and gloves. It was horrible to see used masks and gloves in the street that someone threw on the ground. Across the street someone said goodbye to me. He was my best friend with his dog, but I didn’t recognize him because he was covered by the mask. My best friend!” Narratives reported the adolescents’ difficult impact with a new daily routine in which their closest relationships (best friend) and daily activities (shopping) acquire the meaning of something unusual and perturbing. Similarly, the following extract focused on the feeling of being aware of taking part in a new life routine, which is completely different from one’s wishes about adolescent life: “There is not one episode in particular, but perhaps there is the most negative ‘feeling’ of this period, and it is certainly awareness. It’s being aware that you can’t live your senior year in high school as you would have liked. It’s the awareness of not being able to kiss your mom who just came back from the supermarket with your favorite dessert. It’s the awareness that you can’t go dancing or simply talk with friends about something that isn’t the ‘war bulletin’ or the press conference that resounds in the homes of Italians every night at 6 p.m.” (Participant n. 359, female 16 years old).

The fourth emergent theme was saturated by 18% of lemmas and was labeled “School as educational but not relational environment.” Participants reported the difficulty of being engaged in educational activities, which are perceived as lacking in social opportunities. A male adolescent (n. 60, 17 years old) reported: “since there have been positive cases I’ve stayed at home, but with the online lessons and lots of homework I am getting sad and especially stressed. I wanted to talk about Bergamo with the teachers and my classmates, but there is no time and in the online lessons we only talk about school and homework.”

A participant expressed his feeling of being unwelcome and misunderstood by teachers due to the relational distance: “In my opinion this is the saddest thing that this virus has brought: we young people no longer believe in dreams, but above all in hope for a better future. The professors, instead of understanding this situation, blame us, saying that we are ‘slackers’ and that we think we are on holiday, punishing us with millions of tasks, depriving us of everything. […] So, these are the reasons why we young people are exhausted and full of repressed hatred, because we see our peers die before our eyes and teachers often don’t understand us” (Participant n. 2545, female 17 years old).

Moreover, homework and online classes work as stressors and increase the lack of relations: “I felt agitated because homework and video tutorials have stressed me so much. It’s not the same online. I understand the gravity of the situation, the images we see are terrible, all those coffins. I miss my class, the teacher coming in, everything” (Participant n. 260, male 17 years old).

Positive Experiences Narratives

Concerning positive experiences, four themes emerged from the modeling analysis.

The first theme, the most representative for positive experiences collected, covered 33% of the lemmas and dealt with “Discovering oneself.” Adolescents reported to have discovered the pleasure of spending time with themselves and dedicating time to reading, listening to music, painting, and working out on their own. In this sense, lockdown became an opportunity for self-disclosure and personal growth: “I read, studied, I’ve cooked various stuff, experimented, relaxed taking time for myself, watched TV series, movies, played chess. Everything that made me feel good. I felt accepted by myself, because I had time to think about myself much more and to reflect, making me feel like a better and acceptable person” (Participant n. 2069, male 15 years old).

Similarly, a girl narrated: “Like never before, I have time to look inside and talk to myself in my bedroom, having more doubts, being able to resolve them, or simply leaving them unresolved, discovering what confuses me and understanding who I am” (Participant n. 1369, female 18 years old) .

The second emergent theme was labeled “Sharing life at a distance” (31% of lemmas) and dealt with the opportunity to be in a close relationship even at a distance. A participant narrated his relief in feeling his best friend’s support via video-call: “I Hear my friend tell me on the video-call that everything’s going to be okay and we’re going to come out of this even stronger. She said, ‘We’ll come back and watch the sunset on the beach, we’ll come back and eat ice cream together, we’ll come back and hug everybody, have faith’. I felt safe and full of hope” (Participant n. 2721, male 14 years old).

Friendship as an anchor is a frequent issue in adolescents’ narratives: “I felt a big panic inside and I had a video-call with all my friends at 1 am in a tense moment, it helped me a lot!” (Participant n. 1970, female 17 years old).

The third emerged theme, named “Re-discovering family,” was saturated by 22% of the lemmas and focused on the positive impact of spending time with family members and discovering the joy of doing things together: “I’m realizing how precious time is, every moment must be enjoyed because we could be deprived of it at any moment. I spend more time with my parents, before they were always at work and I used to see them for a few hours” (Participant n. 881, female, 16 years old). Similarly, a boy narrated the positive value of spending time with his grandparents: “I’m spending a lot of time with my grandparents and I’m growing up because they teach me so many things I didn’t know! We’ve rediscovered board games and we often play them all together” (Participant n. 2648, 17 years old).

The last theme, “To be part of an extraordinary experience”, was saturated by 14% of the lemmas and concerned participants’ feeling of being part of an unusual experience, which will have an impact on the culture they are living in. A participant narrated: “When I’m in class and I see my classmates, even if we do a test or an inquiry, it’s still a unique experience that I will tell my kids about!” (Participant n. 2044, male 18 years old). Most of the participants reported their satisfaction in their perception of having an active role in society by following the rules of social distancing and protecting others from contagion: “For once I really felt like a fundamental part of society” (Participant 1841, female 15 years old) .

The present study aimed to explore adolescents’ experience of living during the COVID-19 emergency and national lockdown in terms of narratives on positive and negative experiences. In light of a lack of scientific evidence on adolescents’ experience of living with infectious diseases and under national lockdown, the present study brings knowledge on negative and positive issues of such an impactful experience in this peculiar developmental age of adolescence.

At first, results show that adolescents were more forthcoming about their negative experiences than about positive ones. This datum is not a surprise: scientific literature defines one’s need to “create coherence out of chaos” ( Fivush et al., 2003 , p. 1). Scientific literature highlights that negative narratives are usually longer and more coherent than positive ones, and this is due to the narrator’s need to elaborate autobiographical past by means of language ( Fioretti and Smorti, 2015 , 2017 ).

Looking at word occurrence in both texts, results show similarities between terms used to describe the most negative and positive experiences. Nevertheless, emergent themes put in light different issues related to the same words. Overall, results highlight indeed a complex experience of adolescents characterized by a developmental challenge that may entail risk factors, as in the case of loss and anguish related to illness and contagion, or protective factors, such as the possibility of transforming the COVID-19 experience into an opportunity for personal growth.

In the case of impacting experiences such as diseases or traumatic events, scholars introduced the construct of biographical disruption ( Bury, 1982 ; Fioretti and Smorti, 2014 ), which determines a strong breakdown in one’s life trajectory forcing the individual to restore it finding a continuity between past, present, and future. Concerning COVID-19, our results point out that such a biographical disruption may be associated with the interruption of important developmental tasks such as personal autonomy ( Alonso-Stuyck et al., 2018 ). Of the adolescents’ lemmas, 24% narrated lockdown as a stressor in their process of constructing an individual physical and mental environment separate from the family one.

As shown by narratives on positive experiences of living with COVID-19, home acquires a duplex meaning in adolescents’ lives: loss of autonomy, but also the place where re-discovering family as a protective factor thanks to the opportunity to share activities and to spend time together. As argued by Guessoum et al. (2020) , family time is related with less depression symptoms in adolescents. Moreover, our results suggest that family can play an active role in the co-construction of what it means to live during a pandemic and can provide support during experiences of loss, which, as results show, appear to be the most represented issue in adolescents’ narratives.

As reported by participants, the impossibility of experiencing a direct contact with loss and death may play a traumatic role in adolescents’ lives. In their narratives, grief is forcibly an intimate and individual process in which, as in the case of traumatic events, the disruption is sudden and unexpected. Starting from these results, further investigation on potential posttraumatic disorders and long-term symptoms in adolescents related to COVID-19 is needed.

If family plays a protective role in collected narratives, adolescents denounce the absence of school as a place for relationships and emotional sharing. Participants narrate how they feel like receptors of educational contents without being able to play an active role within the educational process. Passivity and the inability to find a space to share concerns and emotions about the impact of the COVID-19 disease on their lives are the base of a feeling of disconnection from the educational environment. In this sense, the current “absence” of school may constitute a risk factor in adolescents’ development, as described in scientific literature ( Feldman and Matjasko, 2005 ).

School closing is part of a broader spectrum of the breakdown of the daily routine that participants described as a negative experience. In developmental psychology, routines acquire a pivotal role in fostering the security necessary for the process of autonomy and self-definition, in childhood and adolescence ( Crocetti, 2018 ). In this sense, the new life routine of wearing masks and gloves, and performing social distancing strongly impacts the process of creating one’s own identity.

On the other hand, narratives on positive experiences also see COVID-19 as an opportunity to make contact and define certain aspects of one’s identity that have not yet been considered. As shown, the discovery of oneself plays a pivotal role in positive experiences narratives saturating 33% of lemmas in analysis.

Identity, as described by Marcia et al. (2012) , undergoes a strong process of moratorium which, as results suggest, during the quarantine also becomes a path of deeper research into one’s sense of self, without the pressure of external agents. The discovery of the self-emergent theme suggests the hypothesis of a posttraumatic growth (PTG) related to life during the COVID-19 emergency. Participants narrated their individual research of themselves and the discovery of the importance of intimate reflexivity. In literature, over time, several terms have been used to describe the positive changes experienced by a person as a result of stress: “perceived benefits” ( Calhoun and Tedeschi, 1991 ), “raising existential awareness” ( Yalom and Lieberman, 1991 ), “stress-related growth” ( Park et al., 1996 ), and “growth through adversity” ( Joseph and Linley, 2006 ). Posttraumatic growth has been defined as an individual transformation entailing both positive intrapersonal and interpersonal changes caused by the impact of facing life challenges ( Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995 ). Our results suggest that, together with the importance of sharing experiences with peers as reported in 31% of lemmas about positive experiences, an intimate developmental process of self-moratorium was facilitated by living in lockdown due to the COVID-19 emergency. Adolescents narrate their discovery of alone-time as a personal process of growth. Studies on PTG during adolescence are still poor ( Milam et al., 2004 ) and suggest the importance of investigating potential specificities of growth in this peculiar developmental age and its correlations. Future studies could explore the construct of PTG in adolescents exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic in order to further assess a positive impact of living with the current emergency in their lives.

Limitations and Conclusion

Although it provides evidence on a topic which is unknown, the present study has some limitations. First, we did not control for narrative task administration order. All participants completed first the narrative on negative memories and, second, the one on positive experiences. For this reason, the present study did not aim to compare negative and positive experience, rather it considers them as separate narratives on autobiographical experience of living with COVID-19 pandemic.

Moreover, the sample is composed of a large percentage of females and of high school students and does not consider the portions of adolescents of the Italian population who are not currently involved in education. Further studies should consider adolescents’ varying economic and cultural backgrounds. A second limitation is related to the varying impact of the COVID-19 emergency in the different regions of Italy. Adolescents’ experiences might be related to having or not having personal contacts with the disease in their family or social environment. Future studies should focus on specific developmental challenges due to direct or indirect contact with COVID-19.

A third limitation is related to the lack of consideration of the interindividual differences. The study describes a process related to the COVID-19 in the global population without considering possible differential impacts related to personal characteristics and vulnerabilities.

To conclude, the results suggest the need to take into account the impact of lockdown in the developmental tasks of adolescence. As for the negative experiences, loss of autonomy and anguish related to death and loss are the most representative topics. Further studies could better investigate the autonomy issue related to COVID-19 emergency considering the role family and different parenting models can play. For instance, very few studies have investigated the role of pre-pandemic maltreatment experience ( Guo et al., 2020 ) or other experience related to family environment. Our results suggest the duplex role of family and invite scholars and professionals to design specific intervention programs for adolescents with family vulnerability.

Conversely, school, a pivotal developmental environment according to scientific literature, represented a smaller percentage of words in the narratives we collected for our sample, suggesting the need to debate on the lack of relation adolescents perceive in online didactic activities. Home and family may play a double role, both limiting adolescents’ acquisition of autonomy and providing an enriching setting for their personal growth. The latter, discovering oneself, is the most representative in positive experience narratives. In this sense, the starting hypothesis of the present study was left partially unconfirmed. Lockdown and life during the COVID-19 emergency may activate both a disruption and an empowering process in adolescents’ developmental tasks. Further studies are needed on psychological and social variables promoting or contrasting both processes.

In the light of scarce studies exploring narratives on COVID-19 experience, the present research supports the importance of giving language to the autobiographical past by means of methods exploring qualitatively participants’ experience. Results show that a narrative is a tool to collect information on personal experience and to generate insight starting from it. Additionally, a narrative allows narrators emotional disclosure and to give meaning to their life story ( Bruner, 1990 ; McAdams et al., 2006 ). This meaning-making process is even more important in developmental ages, as adolescence is, characterized by self and identity definition and growth of autobiographical process skills ( Habermas and Bluck, 2000 ). We support the need to further investigate adolescents’ narratives in this pandemic transition both as a tool to collect data and as an intervention to promote well-being through emotional and intrapsychic disclosure.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Commissione per l’Etica della Ricerca, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

CF, BP, AN, and EM conceived and performed the study design, data collection, and mastered the data. CF ran the data analysis. BP, AN, and EM discussed the results. CF wrote the manuscript with the support of BP and AN. EM and AN supervised the project and manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Skuola.net and especially its CEO, Daniele Grassucci and Carla Ardizzone and Marcello Gelardini, for the support with data collection. This research would have not been possible without their help during the hard time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- ^ www.skuola.net

Alonso-Stuyck, P., Zacarés, J. J., and Ferreres, A. (2018). Emotional separation, autonomy in decision-making, and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence: a proposed typology. J. Child Fam. Stud. 27, 1373–1383. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0980-5

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., and Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 993–1022.

Google Scholar

Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard university press.

Bury, M. (1982). Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol. Health Illness 4, 167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Calhoun, L. G., and Tedeschi, R. G. (1991). Perceiving benefits in trau matic events: some issues for practicing psychologists. J. Train. Pract. Prof. Psychol. 5, 45–52.

Cortini, M., and Tria, S. (2014). Triangulating qualitative and quantitative approaches for the analysis of textual materials: an introduction to T-lab. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 32, 561–568. doi: 10.1177/0894439313510108

Crocetti, E. (2018). Identity dynamics in adolescence: processes, antecedents, and consequences. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 15, 11–23. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2017.1405578

Dodgson, J. E., Tarrant, M., Chee, Y.-O., and Watkins, A. (2010). New mothers’ experiences of social disruption and isolation during the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Hong Kong. Nurs. Health Sci. 12, 198–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00520.x

Ellis, W. E., Dumas, T. M., and Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Behav. 52, 177–187. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000215

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity Youth and Crisis. New York, NY: W.W. Norton Inc.

Feldman, A. F., and Matjasko, J. L. (2005). The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: a comprehensive review and future directions. Rev. Educ. Res. 75, 159–210. doi: 10.3102/00346543075002159

Fioretti, C., and Smorti, A. (2014). Improving doctor-patient communication through an autobiographical narrative theory. Commun. Med. 11, 275–284. doi: 10.1558/cam.v11i3.20369

Fioretti, C., and Smorti, A. (2015). How emotional content of memories changes in narrative. Narrat. Inq. 25, 37–56. doi: 10.1075/ni.25.1.03fio

Fioretti, C., and Smorti, A. (2017). Narrating positive versus negative memories of illness: does narrating influence the availability and the emotional involvement of memories of illness? Eur. J. Cancer Care 23, 1–7. doi: 10.1111/ECC.12524

Fivush, R., Hazzard, A., McDermott Sales, J., Sarfati, D., and Brown, T. (2003). Creating coherence out of chaos? Children’s narratives of emotionally positive and negative events. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 17, 1–19. doi: 10.1002/acp.854

Green, J., and Thorogood, N. (2018). Qualitative Methods for Health Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Pubblications.

Guessoum, S. B., Lachal, J., Radjack, R., Carretier, E., Minassian, S., Benoit, L., et al. (2020). Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 291:113264. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264

Guo, J., Fu, M., Liu, D., Zhan, B., Wang, X., and van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2020). Is the psychological impact of exposure to COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment experiences? a survey of rural chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Neglect. 2020:104667. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104667

Habermas, T., and Bluck, S. (2000). Getting a life: the emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 126:748. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748

Havighurst, R. J. (1948). Developmental Tasks and Education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Italian Ministry of Health (2020). COVID-19 Daily New Cases and Deaths in Italy. Rome: Italian Ministry of Health.

Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (2020). Cases and Mortality by Country. Available online at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ (accessed July 13, 2020).

Jones, R. M., Vaterlaus, J. M., Jackson, M. A., and Morrill, T. B. (2014). Friendship characteristics, psychosocial development, and adolescent identity formation. Pers. Relationsh. 21, 51–67. doi: 10.1111/pere.12017