Registered Nurse RN

Registered Nurse, Free Care Plans, Free NCLEX Review, Nurse Salary, and much more. Join the nursing revolution.

Cirrhosis NCLEX Review

This NCLEX review will discuss cirrhosis .

As a nursing student, you must be familiar with cirrhosis along with how to care for a patient experiencing this disease.

These type of questions may be found on NCLEX and definitely on nursing lecture exams.

Don’t forget to take the cirrhosis quiz .

You will learn the following from this NCLEX review:

- Definition of cirrhosis

- Signs and Symptoms

- Complications

- Nursing Interventions

Cirrhosis Nursing Lecture

What causes Cirrhosis?

- Viral Infection: Hepatitis C*, B

- Alcohol Consumption: Heavy amount*

- Too much fat collecting in the liver (nonalcoholic): obese, hyperlipidemia, diabetics

- Problems with bile duct (carries bile from liver to small intestine): bile stays in liver and damages cells

*most common causes in the U.S.

Role of the Liver (helps to understand the complications and nursing interventions):

In a nutshell, the liver takes substances in our blood and metabolizes and detoxifies them along with storing and producing substances to help with digestion, clotting, and immune health. In other words, it is SO VERY important for our survival. When it stops working every system in our body struggles!

The liver receives it blood from two sources :

- small/large intestine, pancreas, spleen, stomach

- Second Source: Hepatic artery : it delivers rich oxygenate blood that just came from the heart to the liver, but it’s poor in nutrients .

—– these two blood supplies mix together as they enter the functional units of the liver called the liver lobules (there are thousands of them in the liver). These lobules contain hepatocytes, which perform most of the liver’s function and kupffer cells (macrophages that cleanse the blood coming from the hepatic portal vein and artery), and the blood will exit via the hepatic vein to go back to the heart to be re-oxygenated.

As blood flows through the lobules there a two types of cells performing special jobs (as stated above):

- Kupffer cells: removing bacteria, debris, parasites, old RBCs (remember this because this plays a role with bilirubin)

- Hepatocytes: does most of the work of the liver by performing bile production, metabolism, storage, conjugating bilirubin, and detoxification.

Highlights of the Functions of the Liver

(need to understand these functions to help with understanding the complications and signs/symptoms):

- Glucose : the excessive amounts will be synthesized and stored as glycogen (monitor blood glucose…in cirrhosis the liver can’t synthesize glycogen properly and store it, so more hangs out in the blood, leading to hyperglycemia ) AND converts glycogen into glucose when blood glucose levels are low to increase sugar levels (in cirrhosis, if the patient is sick or not eating the liver is unable to convert the glycogen to glucose so the patient can have episode of hypoglycemia )

- Lipids and Proteins . The liver converts ammonia , which is a byproduct of protein breakdown, into urea which is then excreted via the urine. Urea is much less toxic to the brain that ammonia. This doesn’t happen in cirrhosis which is why the patient will have neuro change, asterixis, HEPATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY, etc.

- Stores vitamins (vitamin B12, A, E, D, and K) and minerals along with iron and glycogen. Remember bile is essential for the absorption of fat soluble vitamins. In cirrhosis, bile production is impaired which will lead to decreased absorption and storage of those fat soluble vitamins (vitamin A, D, E, and K)

- Remember RBCs are removed by the Kupffer cells and components of the RBCs are recycled. The Kupffer cells break down the hemoglobin into heme and globin groups.

Production of blood plasma proteins : albumin (maintains oncotic pressure and water regulation within the interstitial tissue), fibrinogen, prothrombin (aids in clotting).

Detoxifies : makes drugs less harmful to the body. In cirrhosis, the patient is very sensitive to drugs because the liver can’t protect the patient from their harmful effects. It also removes toxins from the body (alcohol) and hormones produced by our glands. For example, estrogen is metabolized in the liver. However, in cirrhosis, it is unable to metabolize estrogen which leaves more of the hormone in the body. This can lead to enlarged breast tissue in men (gynecomastia).

Complications of Cirrhosis:

Portal Hypertension : the portal vein becomes narrowed due to scar tissue in the liver. This restricts the flow of blood to the liver and increases pressure in the portal vein. This will affect the organs connected to the portal vein…..like the spleen, vessels to the GI structure (varices).

Enlarged spleen : “splenomegaly” What does the spleen do? Stores platelets and WBCs. With portal HTN the platelets and WBCs are kept in the spleen. They can’t leave and this leads to a low platelet and WBC count.

Esophageal Varices (as well as gastric varices): due to the increased pressure via the portal vein. This increased pressure causes the veins to become weak, and they can RUPURE!

- Life-threatening if the varice ruptures: WHY? Remember the platelet count will be low along with clotting factors available AND levels of Vitamin-K…they are at risk for a total bleed out.

Fluid overload in legs and abdomen : Ascites (fluid in the abdomen). If the patient has ascites, they are at risk for infection from bacteria in the GI system. Remember the immune system is compromised because of low WBC production. Swelling in the legs and ascites is happening due to venous congestion from the portal HTN and low albumin levels (the water is not being regulated in the body and is entering the interstitial tissue).

Jaundice: yellowing of the sclera of the eyes, mucous membranes, and skin. This is due to the hepatocytes leaking bilirubin into the blood rather than the bile.

Hepatic Encephalopathy: the liver is unable to detoxify. Ammonia builds up along with other toxins that collect in the brain. This leads to an altered mental system, coma, neuromuscular problems, asterixis (involuntary hand-flapping), hepatic foetor “fetor hepaticus” (late sign).

- What is Hepatic Foetor? A pungent, musty, sweet smell to the breath (discussed more below)

Renal Failure : In severe cases known as Hepatorenal Syndrome.

Miscellaneous: Liver Cancer, bone fractures (low vitamin D), diabetes

Signs and Symptoms of Cirrhosis:

Early stages: patients may be asymptomatic, but in the late stages will have:

Remember the mnemonic: “The Liver is Scarred”

T remors of hands (asterixis: hand-flapping due to increased toxins in the blood)

H epatic foetor or “fetor hepaticus”: very late in the disease and is a pungent, sweet, musty smell. This is from the buildup of toxins (mercaptans) in the blood. Why in the breath? The portal hypertension shunts these toxins where they pass through the lungs allowing the smell to be noticed.

E ye and skin yellowing (jaundice)

L oss of appetite (spleen pushing on stomach…feel full)

I ncreased Bilirubin (skin and urine….jaundice) and ammonia

V arices (esophagus and gastric…at risk for bleeding…watching for activities that can increase rupture: coughing, vomiting, drinking ETOH, constipation)

E dema in legs (low albumin and congestion of hepatic veins)

R educed platelets and WBCs (bleeding and infection risk)

I tchy skin (toxins the blood)

S pider angiomas (chest) (increased estrogen in the blood)

S plenomegaly (low platelets and WBCs), stool clay colored (no bilirubin in the stool…should be there not in the urine or blood)

C onfusion or coma (high toxin and ammonia level)

A scites (low albumin and venous congestion)

R edness on the palms of the hands (increased estrogen in the blood)

R enal failure (hepatorenal syndrome)

E nlarged breast in men (decrease metabolism of estrogen so there is more in the blood)

D eficient on vitamins (B12, A, C, D, E, K and iron) (no longer able to store and have bile to help absorb these fat soluble vitamins)

- Liver biopsy

- Labs: liver enzymes (albumin), platelet levels, PT/INR, hepatitis B or C, bilirubin levels

Nursing Interventions for Cirrhosis:

Monitor for bleeding (PT and INR)

- limit invasive procedures and hold pressure at injection sites for 5 minutes or more, soft tooth brushes, safety, assessing stools, urine, petechiae

Monitor Esophageal varices

- Monitor very closely for bleeding, darky tarry stools, vomiting blood, (bleeding is an emergency!!) Watch for activities that can increase rupture: coughing, vomiting, drinking ETOH, constipation

Check reflexes , mental status very closely (mental status change, irritability, confusion), hepatic encephalopathy, and for flapping of the hands “asterixis”

- If neuro system is compromised: low protein diet: protein breaks down into ammonia

- If neuro system NOT compromised : high lean protein (fish, poultry) NO ETOH, or raw seafood (oysters….contain bacteria that the immune system is too weak to fight and detoxify from the body), fluid restriction, needs vitamin (administer PO vitamins per MD order)

Monitor blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia)

Assessing sclera and skin color for Jaundice along with urine color: very dark

Monitor I’s and O’s very closely, daily weight, and measuring abdominal girth (monitor ascites) and swelling in extremities

Activity intolerance, difficulty breathing (no supine), at risk for skin breakdown (turning every 2 hours), elevating feet

Administering Lactulose per MD order: decreases ammonia levels

- Liver transplant

- Shunting surgery (helps alleviate the ascites)

- beta blockers (slows the heart rate..decreases force of contraction and also helps with the treatment of esophageal varices) and Nitrates (dilate vessels) to treat portal hypertension

- Administer blood products and vitamin K to help with clotting

- Lactulose (to decrease ammonia level)

- Paracentesis (to remove fluid from abdomen)

References:

1.Cirrhosis | NIDDK . (2017). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . Retrieved 16 October 2017, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/cirrhosis

2. FastStats . (2017). Cdc.gov . Retrieved 16 October 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/liver-disease.htm

Please Share:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

Disclosure and Privacy Policy

Important links, follow us on social media.

- Facebook Nursing

- Instagram Nursing

- TikTok Nurse

- Twitter Nursing

- YouTube Nursing

Copyright Notice

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Alcohol consumption and risk of liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Michael Roerecke, Afshin Vafaei, Omer SM Hasan, Bethany R Chrystoja, Jürgen Rehm

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, 33 Russell Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2S1

Marcus Cruz, Roy Lee, Manuela G Neuman

In Vitro Drug and Biotechnology, Banting Institute, lab. 217, 100 College St., Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1L5, Canada

Authors’ contributions

Associated Data

To systematically summarize the risk relationship between different levels of alcohol consumption and incidence of liver cirrhosis.

Medline and Embase were searched up to March 6 th , 2019 to identify case-control and cohort studies with sex-specific results and more than two categories of drinking in relation to incidence of liver cirrhosis. Study characteristics were extracted and random-effects meta-analyses and meta-regressions were conducted.

A total of seven cohort studies and two case-control studies met the inclusion criteria, providing data from 2,629,272 participants with 5,505 cases of liver cirrhosis. There was no increased risk for occasional drinkers. Consumption of 1 drink per day in comparison to long-term abstainers showed an increased risk for liver cirrhosis in women, but not in men. The risk for women was consistently higher compared to men. Drinking ≥5 drinks per day was associated with a substantially increased risk in both women (RR = 12.44, 95% CI: 6.65 – 23.27 for 5–6 drinks, and RR = 24.58, 95% CI: 14.77 – 40.90 for ≥7 drinks) and men (RR = 3.80, 95% CI: 0.85 – 17.02, and RR = 6.93, 95% CI: 1.07 – 44.99, respectively). Heterogeneity across studies indicated the additional impact of other risk factors.

Conclusions

Alcohol is a major risk factor for liver cirrhosis with risk increasing exponentially. Women may be at higher risk compared to men even with little alcohol consumption. More high-quality research is necessary to elucidate the role of other risk factors, such as genetic vulnerability, body weight, metabolic risk factors, and drinking patterns over the life course. High alcohol consumption should be avoided, and people drinking at high levels should receive interventions to reduce their intake.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol is a major risk factor for liver disease in general, and for liver cirrhosis in particular.( 1 – 3 ) In fact, about half of the liver cirrhosis burden of morbidity and mortality would disappear in a world without alcohol.( 4 ) Mortality from liver cirrhosis has been on the rise in the US( 5 ) and Europe,( 6 ) more so in women than in men. Alcohol consumption is partly responsible, but liver disease is increasingly recognized as a multifactorial disease process.( 6 )

The importance of alcohol in the etiology of liver disease has led to establishing different codes for categories of liver diseases, which are considered to be primarily caused by alcohol. Thus, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10( 7 )) recognizes several forms of alcoholic liver disease (ICD-10, K70), sometimes considered stages( 8 ) that range from relatively mild and reversible alcoholic hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) (K70.0) and alcoholic hepatitis (K70.1), to alcoholic fibrosis and sclerosis of the liver (K70.2), and further to severe and irreversible stages such as alcoholic liver cirrhosis (K70.3) and alcoholic hepatic failure (K70.4). Alcohol consumption, in particular heavy use over time, has been found crucial in the etiology and progression of these diseases.( 1 , 9 , 10 ) However, liver diseases are multifactorial, and alcohol use may play a role in the progression of all types of cirrhosis,( 11 ) and even one drink per day may have an effect on the incidence of liver cirrhosis, ( 12 ). For scientific review of all liver cirrhosis, it is therefore crucial to include both alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis when examining the impact of alcohol use.

Most of the epidemiological literature to date has dealt with the level of drinking and incidence or mortality of liver cirrhosis.( 13 ) It followed the epidemiological tradition of the early studies of Lelbach and others,( 14 , 15 ) who, based on studies in people with alcohol use disorders, postulated a clear association between volume of alcohol use and liver cirrhosis.( 1 ) This association was corroborated in more rigorous studies.( 1 , 13 , 16 ) It remains to be determined, however, if a threshold for alcohol-related damage to the liver exists, or whether any amount of alcohol increases the risk for liver cirrhosis, which has been discussed recently.( 17 – 19 ) In fact, the last meta-analysis on the topic is now more than 10 years old and found some evidence for a protective association at low levels of alcohol intake in men.( 13 ) Furthermore, several large-scale studies have been published since then.( 20 – 22 )

The present review provides an overview of the current knowledge on the dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and risk of liver cirrhosis in comparison to abstainers, with particular consideration given to the effects of study design and sex, and other subgroups where data were available. As noted above, our review was not restricted to alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Following the MOOSE guidelines,( 23 ) we conducted a systematic electronic literature search using Medline and Embase from inception to March 6 th , 2019 for keywords and MeSH terms relating to alcohol consumption, liver cirrhosis, and observational studies ( Supplementary Table 1 ). Additionally, we searched reference lists of identified articles and published meta-analyses and reviews. Inclusion criteria were as follows:

- cohort and case-control studies examining the sex-specific association between average alcohol consumption and liver cirrhosis,

- analyses were adjusted for age at baseline,

- data for at least two quantitatively defined categories of average alcohol consumption in relation to non-drinkers, or data for former drinkers in relation to long-term abstainers were reported,

- more than 50 cases of liver cirrhosis occurred.

We did not apply language restrictions. At least two reviewers independently excluded articles based on title and abstract or full-text and abstracted the data. Any discrepancies were resolved in consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

From all relevant articles we extracted authors’ names, year of publication, country, year(s) of baseline examination, follow-up period, setting of the study, study design, assessment of liver cirrhosis, age (range, mean or median) at baseline, sex, number of observed liver cirrhosis cases among participants by drinking group, number of total participants by drinking group, specific adjustment or stratification for potential confounders, and adjusted relative risks (RRs) and their confidence intervals (CIs) or standard errors. Risk estimates by sex were treated as independent samples. Where necessary, RRs within studies were re-calculated to contrast alcohol consumption categories against non-drinkers.( 24 )

Exposure and outcome assessment

Consolidating exposure measures across primary studies involved a two-step process. First, among drinkers, we converted reported alcohol intake categories in primary studies into an average of pure alcohol in grams per day (g/day) using the midpoints (mean or median) of reported drinking group categories. For open-ended categories, we added three quarters of the second highest category’s range to the lower limit of the open-ended category of alcohol intake if the mean was not reported. Standard drinks vary by country, with one standard drink containing approximately 8–14 g of pure alcohol.( 25 ) We used reported conversion factors when standard drinks were the unit of measurement to convert all measures to grams per day. Then, for reporting of our analyses, we considered categories with a mean of up to 12 grams pure ethanol as one standard drink for a global representation. Qualitative descriptions, such as ‘social’ or ‘frequent’ drinkers with no clear total alcohol intake in g/day were excluded. When current non-drinkers were the reference group (i.e., including both long-term abstainers and former drinkers), we adjusted risk estimates for the effect of former drinking compared to long-term abstention, based on the pooled risk for former drinking from two studies included in this review to avoid the sick-quitter effect. Long-term abstainers were defined as people who stated that they never consumed alcohol,( 20 ) people who stated that they never, or almost never, drank alcohol in the past,( 26 ) and when people who had greatly decreased their consumption in the last 10 years were excluded from non-drinkers.( 27 ) The logRR for former drinkers in comparison to long-term abstainers (RR former drinkers = 2.52) was multiplied by the mean fraction of former drinkers among current non-drinkers (0.23) and added to the respective logRRs of current drinking groups from primary studies used in our analysis when current non-drinkers was the reference group.

Liver cirrhosis due to known aetiology such as alcohol, and unspecified liver cirrhosis was defined as in the primary studies, which included ICD codes for liver cirrhosis (ICD-7: 581; ICD-8: 571; ICD-10: K70, K73, K74) and unspecified liver cirrhosis (ICD-8: 571.9, 456.0, 785.3; ICD-10: I85.0, I85.9, K74.6, R18.9). Because we aimed to estimate the relative risk in comparison to abstainers, we excluded several studies (e.g., ( 28 , 29 )) which focused only on alcoholic liver cirrhosis (or included alcoholism in addition to liver cirrhosis in the outcome),( 30 ) which, by definition, cannot occur in lifetime abstainers.

Quality assessment

Most quality scores are tailored for meta-analyses of randomized trials of interventions( 31 – 33 ) and many criteria do not apply to epidemiological studies examined in this study. Additionally, quality score use in meta-analyses remains controversial.( 34 – 36 ) As a result, study quality was enhanced by including quality components, such as study design, measurement of alcohol consumption and liver cirrhosis, adjustment for age in our inclusion and exclusion criteria, and further by investigating potential heterogeneity in several sensitivity analyses. We used the most adjusted RR reported and the most comprehensive data available for each analysis and gave priority to estimates where lifetime or long-term abstainers were used as the risk reference group.

In a formal risk of bias analysis, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Non-Randomized Studies (ROBINS-I( 37 )) to assess risk of bias in primary studies. We rated the evidence for the association between alcohol consumption and incidence of liver cirrhosis based on the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation system (GRADE).( 38 )

Statistical analyses

In categorical analyses using standard drinks (12 grams pure alcohol) as the exposure measure, RRs were pooled with inverse-variance weighting using DerSimonian-Laird random-effect models to allow for between-study heterogeneity.( 39 ) Small-study bias was examined using Egger’s regression-based test.( 40 ) Variation in the effect size because of heterogeneity between studies was quantified using the I 2 statistic.( 41 )

Using studies that reported data for four or more alcohol intake groups, we conducted two-stage restricted cubic spline regression analysis in multivariate meta-regression models, taking into account the variance-covariance matrix for risk estimates derived from one reference group( 42 , 43 ) to test for non-linear dose-response relationships in relation to long-term abstainers. All meta-analytical analyses were conducted on the natural log scale in Stata Statistical Software, Version 14.2.

Role of funding source

The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

In total, out of 2,977 identified references, 385 articles were retrieved in full-text. Of these, seven cohort and two case-control studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria ( Figure 1 ). Four studies were conducted in the US,( 26 , 27 , 44 , 45 ), two in Italy,( 46 , 47 ) and one each in China,( 22 ) the UK,( 21 ) and Denmark.( 20 ) In total, data from 2,629,272 participants (579,592 men, 2,049,680 women) and 5,505 cases of liver cirrhosis (2,196 men, 3,309 women) were used in the analyses. All cohort studies included liver cirrhosis mortality as the outcome. The two case-control studies investigated first-time diagnosis of symptomatic liver cirrhosis in comparison to lifetime abstainers ( Table 1 ). The study by Liu et al contributed 2,078 liver cirrhosis cases from the National Health Service Million Women Study linked to death and morbidity registries.( 21 ) The proportion of non-drinkers varied widely, from 0.002% (lifetime abstainers) among men in the Danish study by Askgaard et al. ( 20 ) to 80% (current abstainers) in the study of women from the American Cancer Society I cohort by Garfinkel et al .( 44 ) All cohort studies used a one-time measurement of alcohol consumption as the baseline alcohol intake, while the three case-control studies from Italy assessed lifetime alcohol consumption retrospectively. All but one cohort study were rated to be of moderate quality mainly because of the one-time measurement of alcohol consumption at baseline (cohort studies), and the observational study design ( Supplementary Table 2 ). One cohort study( 44 ) had potential serious bias because the results were adjusted only for age.

Flowchart of study selection

Characteristics of 7 cohort and 2 case-control studies investigating risk of liver cirrhosis by alcohol intake, 1988–2017.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; M, men; W, women; M, W, men and women stratified; M/W, men and women combined; SES, socioeconomic status; NHS, National Health System.

The pooled proportion of former drinkers among current abstainers( 20 , 26 ) was 23%, and the pooled RR for liver cirrhosis in comparison to long-term abstainers was 2.56 (95% CI: 0.93 – 6.79). Figure 2 displays the RRs for liver cirrhosis in cohort studies by alcohol intake in reference to long-term abstainers after current abstention at baseline was adjusted for the proportion and risk in former drinkers. Alcohol consumption beyond occasional drinking, which showed a similar risk compared to long-term abstainers, was associated with increasing risk for liver cirrhosis ( Figure 2 ) with a pooled RR of 10.70 (95% CI: 2.95–38.78) for consumption of 7 drinks or more per day. However, all drinking categories showed substantial heterogeneity across studies (I 2 between 70 and 98%, all P-values <0.001), resulting in large confidence intervals. We restricted analyses of small-study effects and influential studies to drinkers of 1 or 2 drinks per day for both sexes because of the small number of studies identified. We found no statistical evidence for small study bias for drinkers of 1 or 2 drinks per day (P = 0.94), the funnel plot showed similar results ( Supplementary Figure 1 ). None of the studies had an overly large impact on the pooled estimates ( Supplementary Figure 2 ).

Relative risk on the log scale. 1 standard drink = 12 grams pure ethanol per day. RR = relative risk.

Results for men and women are shown separately in Figures 3 and and4, 4 , respectively. Across all consumption levels, RRs in women were higher, reaching RR = 24.58 (95% CI: 14.77–40.90) for ≥7 drinks. While consumption of 1–2 drinks was associated with a substantially elevated risk for liver cirrhosis in women, this was not the case in men. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution because of the small number of studies available. Four cohort studies( 20 , 21 , 26 , 27 ) in women were adjusted for age, BMI or waist circumference, and smoking. The relationship was similar to the main analysis with an elevated and linearly increasing risk for consumption of 1 drink and beyond ( Supplementary Figure 3 ).

In both men and women, there was no evidence for a non-linear dose-response relationship on the log scale (P=0.24 and 0.27, respectively, Supplementary Figures 4 and 5 ). However, the number of studies available was low, resulting in little power to detect non-linearity.

The two case-control studies with liver cirrhosis morbidity as the outcome yielded smaller risks associated with alcohol consumption, with 1–4 drinks showing no risk increase compared to lifetime abstainers (pooled RR=1.19, 95% CI: 0.58–2.43, Figure 5 ). Risks for consumption of 5–8 and 9–13 drinks were associated with large heterogeneity with one study( 47 ) showing substantial risk increases for both men and women, while the other study( 46 ) showed no or marginally statistically significant risk increases for either men or women (see also Supplementary Figures 6 and 7 ).

Subgroup analyses

One cohort study( 21 ) showed that while the risk in smokers was higher than in never-smokers, the risk of liver cirrhosis by alcohol intake increased in never-smokers similar to current smokers, indicating that smoking is a confounder but not an effect modifier. In another report( 48 ) from the case-control studies by Corrao et al , it was shown that the relationship between alcohol and liver cirrhosis in all participants was similar to participants without serum HBsAg and/or positive anti-HCV status. One of the case-control studies( 46 ) included in our main analysis also showed that the risk for liver cirrhosis was greatest in drinkers who drank heavily for 10 or 20 years, but not for 30 years, indicating potentially a survivor bias. Similarly, the same study( 46 ) reported risk by age (≤60 years and > 60 years), showing that the risk increase was stronger in younger participants for both sexes. The cohort study by Askgaard et al. ( 20 ) reported results by frequency of drinking days adjusted for weekly alcohol intake. In men, there was an increased risk for daily drinking in comparison to drinking on 2–4 days per week (RR = 2.25, 95% CI: 1.68–3.00). In women, the RR was 1.28 (95% CI: 0.82–2.02). Results from the UK Million Women study( 49 ) showed that among drinkers daily drinking in comparison to non-daily drinking (RR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.40–1.85) and drinking with meals in comparison to drinking outside of meals (RR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.62–0.77) were associated with incidence of liver cirrhosis. These associations were similar in strata of BMI, smoking status, and type of alcoholic beverage. Women who both drank daily and outside of meals had a 2.47 (95% CI: 1.96–3.11) increased risk for liver cirrhosis with adjustment for amount and type of beverage.( 49 )

Given the observational nature of the studies included in this report, we rate the evidence for a causal effect of alcohol consumption and risk for liver cirrhosis as moderate. However, the dose-response relationship in addition to established biological pathways confirmed in randomized controlled trials( 50 ) give rise to high confidence in a causal dose-response relationship. There was no clear indication for a threshold effect, but we rate the quality of the evidence as low because of imprecision and the small number of studies reporting sex-specific RRs for low levels of drinking.

We conducted a systematic review and various meta-analyses on alcohol consumption and risk of liver cirrhosis. Contrary to prior analyses,( 13 ) we found overall no protective effects at any level of drinking when compared to long-term abstainers, and a steadily increasing dose-response relationship in women, and some evidence for a threshold effect in men. However, risks varied widely and the analysis of case-control studies showed no risk increase for consumption of 1–4 drinks per day. The high risk for heavy drinkers found in our meta-analysis of cohort studies is in line with prior research on risk for liver cirrhosis in people with alcohol use disorders.( 11 , 51 , 52 ) The pooled RRs from case-control studies were much smaller; however, the more recent case-control study( 47 ) corresponds with the risks found in people with alcohol use disorder. One of the cohort studies and one of the case-control studies reported very small RRs compared to the other studies. The reasons for this are unclear, although some outliers are to be expected in any statistical analysis.

Additionally, many studies were not well adjusted and of generally moderate methodological quality, mostly related to potential bias due to confounding and selection bias. While the increase in risk was stronger in women, confidence intervals were large and overlapped with those for men. Stronger effects in women are supported by studies in people with alcohol use disorder with or without liver cirrhosis( 53 , 54 ), and higher hepatotoxicity. While there is no doubt that heavy alcohol consumption is one of the main risk factors for liver cirrhosis, the large heterogeneity observed indicates that the multifactorial nature of development of liver cirrhosis has not been reflected in the epidemiological literature. Liver cirrhosis has a complex and not fully understood etiology, and the contributory role of other risk factors for liver cirrhosis, such as BMI, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, drinking frequency and outside of meals, and others, at any given level of alcohol intake over the life course, need more attention in both research and prevention efforts.

While several important confounders have been identified and should be adjusted for in epidemiological studies, it is likely that some of them are in fact effect modifiers that impact the risk associated with alcohol consumption. Most important here is genetic vulnerability. Twin studies have shown a three-fold higher disease concordance between monozygotic twins and dizygotic twins, but the genetic case-control studies have not yet led to conclusive results.( 55 ) Genetic vulnerability is seen as the major reason why only a minority of very heavy drinkers develop liver problems. With respect to other potential effect modifiers, it seems that the drinking frequency modifies the risk for liver cirrhosis associated with a given total weekly alcohol intake with fewer drinking days being associated with lower risk supporting the notion of a ‘liver holiday’.( 56 – 58 ) A report from the Singapore Chinese Health Study( 59 ) showed that among daily drinkers, consumption of even one drink a day was associated with a RR = 2.72 (95% CI: 0.98–7.50) for liver cirrhosis in comparison to non-drinkers. In more recent years, patterns of drinking, especially binge drinking, were introduced as potentially important for the etiology and progression of liver cirrhosis.( 60 , 61 ) However, evidence is limited and inconclusive at this point.( 62 , 63 ) Future research should include standard measures on patterns of drinking, such as measures of irregular heavy drinking in addition to average volume of drinking and drinking frequency, to test hypotheses about such patterns, and to determine whether there is a positive effect of abstinence days.( 64 ) The consumption of mostly wine, as opposed to beer or liquor, has been shown to modify the risk for alcoholic liver cirrhosis in some studies;( 29 , 58 ) however, as the UK Million Women study showed,( 49 ) this may be explained by the consumption of alcohol with meals, which is more common in wine drinkers than consumers of other types of alcohol.

An investigation of Midspan cohorts( 65 ) in Scotland indicated that BMI modifies the effect of alcohol consumption on liver disease, with obese participants being more susceptible to the harms from alcohol consumption than participants with lower BMI. An analysis of the Million Women Study( 66 ) confirmed that BMI and alcohol consumption interact in development of liver cirrhosis, in particular at alcohol intake of more than 150 g/week and BMI above 30. Potential interaction with drinking patterns seem possible.( 62 ) The effect of smoking in relation to alcohol consumption on liver cirrhosis is not clear. Several studies have reported an effect independent of alcohol consumption( 21 , 67 ), and no clear effect.( 68 , 69 ) Meta-analyses of the association of coffee consumption and risk for liver disease consistently show a decreased risk.( 70 , 71 ) Potential interaction with alcohol consumption should be explored. Liver cirrhosis severity may also play a role. Another analysis from the series of case-control studies from Italy showed the risk increase from alcohol consumption was characterized by a threshold effect at approximately 150 g/day, and a smaller risk at higher consumption for asymptomatic liver cirrhosis than for symptomatic liver cirrhosis. In other reports including the same participants,( 69 , 72 ) it was shown that HBV and HCV infection were risk factors independent from alcohol consumption. The role of nutrient intake is unclear. Several nutrients were investigated in reports from the Italian case-control studies. Possible interaction effects were observed for dietary intake of lipids,( 73 ) vitamin A,( 74 ) and iron.( 74 ) However, larger sample sizes are required to detect an effect with sufficient power. More and higher quality epidemiological studies are needed to reach firm conclusions about confounding and interaction effects of these risk and protective factors in men and women.( 51 )

Other limitations of this review are based on the underlying literature. First, the number of original articles was limited. This is surprising given the fact that the majority of liver cirrhosis cases would not exist in a counterfactual scenario without alcohol. Second, the quality of the contributions was limited. Because of the small number of studies published, we were unable to investigate in detail the role of many study design characteristics, such as adjustment for potential confounders, follow-up length, race/ethnicity, and others that may play a role in the development of liver cirrhosis. Low response rates and inclusion criteria in primary studies, such as participants in screening programs, may limit the generalizability of our findings. Although self-reported alcohol consumption is generally reliable,( 75 ) it may result in underestimation of the real consumption. No cohort study measured alcohol consumption more than once, thus opening the research to measurement and regression dilution bias, and underestimation of the real effect.( 76 ) While the two case-control studies from Italy were able to assess lifetime drinking retrospectively, these types of studies are prone to recall bias, and categories of alcohol consumption were large, and adjustments for other risk factors for liver cirrhosis were minimal. Again, even with similar methodology in the same country, the two studies observed large differences in risk for liver cirrhosis for a given total alcohol intake. One possibility for the difference in risk observed between cohort and case-control studies is because of the difference in outcome assessment (mortality vs morbidity).

In comparison to our earlier meta-analysis,( 13 ) the strengths of this meta-analysis lie in its clear definition of the outcome, and its methodological rigour. For example, we excluded studies with insufficient number of cases or adjustment,( 77 ) and provide an examination of age, drinking patterns, and type of beverage where data were available. This strength came at a cost - some of the most well-known studies in the field, which were limited to subcategories of liver cirrhosis, had to be excluded.( 28 , 29 ), which was crucial to quantify the risk of liver cirrhosis in comparison to abstainers, which by definition cannot develop alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

What are the clinical conclusions of this study? The exponential dose-response curve on the relative risk level indicates that the highest levels of average volume of alcohol consumption confer exponentially higher risks and should be avoided.( 78 ) For people at the high end of this trajectory, the risk for liver cirrhosis is very high,( 16 ) and reductions of the highest levels are associated with the highest health gains.( 79 ) This can be achieved on the individual level in two ways: first, the trajectory towards these levels should be interrupted early, and more than once. This should best be done at the general practitioner level with screening and brief interventions or treatment;( 80 ) however, screening for unhealthy alcohol use is still not conducted routinely.( 81 , 82 )` Second, ( 79 )to prevent liver cirrhosis and subsequent complications including death in people with continued high consumption, it is most important to reduce high levels, even if the new drinking level are still high, and even if the patients still qualify for alcohol use disorders. Of course, the larger the reduction from a given level, the larger the reduction of relative risk, but it should be taken into consideration that any reduction of high volume drinking will be beneficial.( 83 ) Finally, there are alcohol control policy measures. Measures like increase in price via taxation( 84 ) or restrictions in availability have historically shown to impact on liver cirrhosis deaths.( 85 ) Thus, the current high impact of alcohol consumption on liver cirrhosis is avoidable, and both individual interventions in the health care sector and alcohol control policies can contribute to reduce this impact.

Study Highlights

What is the current knowledge.

- Alcohol is involved in all types of liver disease, and high alcohol consumption is associated with high disease risk.

- Prior systematic evidence syntheses have included inconsistent definitions of alcohol exposure and liver cirrhosis.

What is new here

- The risk for incidence of liver cirrhosis for former drinkers in comparison to long-term abstainers was three-fold.

- With any alcohol consumption, the risk for liver cirrhosis increased exponentially among women; among men, the risk increased beyond consumption of 1 drink or more per day.

- Drinking daily and outside of meals increases the risk for liver cirrhosis at any given level of overall alcohol intake. Several other risk factors for liver cirrhosis may modify the association of alcohol with liver cirrhosis, such as genetics, age, BMI, metabolic risk factors, and others.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary file, financial support.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Alcohol Abuse And Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21AA023521 to MR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The sponsor of the study (NIAAA) had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The authors collected the data, and had full access to all of the data in the study. The authors also had final responsibility for the decision to submit the study results for publication.

Declaration of interests

MR and JR report grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), during the conduct of the study. JR reports grants and personal fees from Lundbeck and D&A Pharma outside of this work. AV, OSMH, BRC, MGN, RL, MC report no conflicts of interest.

Hepatic Cirrhosis

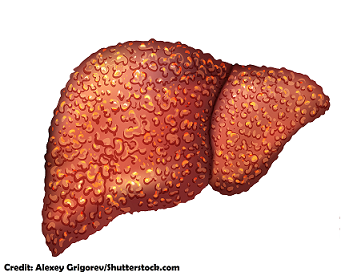

- Hepatic cirrhosis is a chronic hepatic disease characterized by diffuse destruction and fibrotic regeneration of hepatic cells.

Table of Contents

- What is Hepatic Cirrhosis?

Classification

Pathophysiology, statistics and incidences, clinical manifestations, complications, assessment and diagnostic findings, pharmacologic therapy, surgical management, nursing assessment, nursing diagnosis, nursing care planning & goals, nursing interventions, discharge and home care guidelines, documentation guidelines, practice quiz: hepatic cirrhosis, what is hepatic cirrhosis.

The end-stage of liver disease is called cirrhosis.

- As necrotic tissue yields to fibrosis, this disease alters liver structure and normal vasculature, impairs blood and lymph flow, and ultimately causes hepatic insufficiency.

- The prognosis is better in noncirrhotic forms of hepatic fibrosis, which cause minimal hepatic dysfunction and don’t destroy liver cells.

These clinical types of cirrhosis reflect its diverse etiology:

- Laennec’s cirrhosis. The most common type, this occurs in 30% to 50% of cirrhotic patients, up to 90% of whom have a history of alcoholism.

- Biliary cirrhosis. Biliary cirrhosis results in injury or prolonged obstruction.

- Postnecrotic cirrhosis. Postnecrotic cirrhosis stems from various types of hepatitis .

- Pigment cirrhosis. Pigment cirrhosis may result from disorders such as hemochromatosis.

- Cardiac cirrhosis. Cardiac cirrhosis refers to cirrhosis caused by right-sided heart failure .

- Idiopathic cirrhosis. Idiopathic cirrhosis has no known cause.

Although several factors have been implicated in the etiology of cirrhosis, alcohol consumption is considered the major causative factor.

- Necrosis. Cirrhosis is characterized by episodes of necrosis involving the liver cells.

- Scar tissue. The destroyed liver cells are gradually replaced with a scar tissue.

- Fibrosis. There is diffuse destruction and fibrotic regeneration of hepatic cells.

- Alteration. As necrotic tissue yields to fibrosis, the disease alters the liver structure and normal vasculature, impairs blood and lymph flow, and ultimately causes hepatic insufficiency.

Various types of cirrhosis may occur in different types of individuals.

- The most common, Laennec’s cirrhosis, occurs in 30% to 50% of cirrhotic patients.

- Biliary cirrhosis occurs in 15% to 20% of patients.

- Postnecrotic cirrhosis occurs in 10% to 30% of patients.

- Pigment cirrhosis occurs in 5% to 10% of patients.

- Idiopathic cirrhosis occurs in about 10% of patients.

Different types of cirrhosis have different causes.

- Excessive alcohol consumption. Too much alcohol intake is the most common cause of cirrhosis as liver damage is associated with chronic alcohol consumption.

- Injury. Injury or prolonged obstruction causes biliary cirrhosis.

- Hepatitis. The different types of hepatitis can cause postnecrotic cirrhosis.

- Other diseases. Diseases such as hemochromatosis causes pigment cirrhosis.

- Right-sided heart failure. Cardiac cirrhosis, a rare kind of cirrhosis, is caused by right-sided heart failure.

Clinical manifestations of the different types of cirrhosis are similar, regardless of the cause.

- GI system. Early indicators usually involve gastrointestinal signs and symptoms such as anorexia , indigestion, nausea , vomiting constipation , or diarrhea .

- Respiratory system . Respiratory symptoms occur late as a result of hepatic insufficiency and portal hypertension , such as pleural effusion and limited thoracic expansion due to abdominal ascites, interfering with efficient gas exchange leading to hypoxia.

- Central nervous system . Signs of hepatic encephalopathy also occur as a late sign, and these are lethargy, mental changes, slurred speech, asterixis (flapping tremor), peripheral neuritis, paranoia, hallucinations, extreme obtundation, and ultimately, coma.

- Hematologic. The patient experiences bleeding tendencies and anemia .

- Endocrine. The male patient experiences testicular atrophies, while the female patient may have menstrual irregularities, and gynecomastia and loss of chest and axillary hair .

- Skin. There is severe pruritus, extreme dryness, poor tissue turgor, abnormal pigmentation, spider angiomas, palmar erythema, and possibly jaundice .

- Hepatic. Cirrhosis causes jaundice, ascites, hepatomegaly, edema of the legs, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatic renal syndrome.

The complications of hepatic cirrhosis include the following:

- Portal hypertension . Portal hypertension is the elevation of pressure in the portal vein that occurs when blood flow meets increased resistance.

- Esophageal varices. Esophageal varices are dilated tortuous veins in submucosa of the lower esophagus.

- Hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy may manifest as deteriorating mental status and dementia or as physical signs such as abnormal involuntary and voluntary movements.

- Fluid volume excess . Fluid volume excess occurs due to an increased cardiac output and decreased peripheral vascular resistance.

Laboratory findings and imaging studies that are characteristic of cirrhosis include:

- Liver scan. Liver scan shows abnormal thickening and a liver mass.

- Liver biopsy . Liver biopsy is the definitive test for cirrhosis as it detects destruction and fibrosis of the hepatic tissue.

- Liver imaging. Computed tomography scan , ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging may confirm the diagnosis of cirrhosis through visualization of masses, abnormal growths, metastases, ans venous malformations.

- Cholecystography and cholangiography. These two visualize the gallbladder and the biliary duct system.

- Splenoportal venography. Splenoportal venography visualizes the portal venous system.

- Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. This test differentiates intrahepatic from extrahepatic obstructive jaundice and discloses hepatic pathology and the presence of gallstones .

- Complete blood count . There is decreased white blood cell count, hemoglobin level and hematocrit, albumin, or platelets.

Medical Management

Treatment is designed to remove or alleviate the underlying cause of cirrhosis.

- Diet . The patient may benefit from a high-calorie and a medium to high protein diet , as developing hepatic encephalopathy mandates restricted protein intake.

- Sodium restriction. is usually restricted to 2g/day .

- Fluid restriction. Fluids are restricted to 1 to 1.5 liters/day .

- Activity. Rest and moderate exercise is essential.

- Paracentesis. Paracentesis may help alleviate ascites.

- Sengstaken-Blakemore or Minnesota tube. The Sengstaken-Blakemore or Minnesota tube may also help control hemorrhage by applying pressure on the bleeding site.

Drug therapy requires special caution because the cirrhotic liver cannot detoxify harmful agents effectively.

- Octreotide . If required, octreotide may be prescribed for esophageal varices.

- Diuretics . Diuretics may be given for edema, however, they require careful monitoring because fluid and electrolyte imbalance may precipitate hepatic encephalopathy.

- Lactulose. Encephalopathy is treated with lactulose.

- Antibiotics . Antibiotics are used to decrease intestinal bacteria and reduce ammonia production, one of the causes of encephalopathy.

Surgical procedures for management of hepatic cirrhosis include:

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure. The TIPS procedure is used for the treatment of varices by upper endoscopy with banding to relieve portal hypertension.

Nursing Management

Nursing management for the patient with cirrhosis of the liver should focus on promoting rest, improving nutritional status, providing skin care, reducing risk of injury, and monitoring and managing complications.

Assessment of the patient with cirrhosis should include assessing for:

- Bleeding. Check the patient’s skin, gums, stools, and vomitus for bleeding.

- Fluid retention. To assess for fluid retention, weigh the patient and measure abdominal girth at least once daily.

- Mentation. Assess the patient’s level of consciousness often and observe closely for changes in behavior or personality.

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnosis for the patient are:

- Activity intolerance related to fatigue , lethargy, and malaise.

- Imbalanced nutrition : less than body requirements related to abdominal distention and discomfort and anorexia.

- Impaired skin integrity related to pruritus from jaundice and edema.

- High risk for injury related to altered clotting mechanisms and altered level of consciousness.

- Disturbed body image related to changes in appearance, sexual dysfunction , and role function.

- Chronic pain and discomfort related to enlarged liver and ascites.

- Fluid volume excess related ascites and edema formation.

- Disturbed thought processes and potential for mental deterioration related to abnormal liver function and increased serum ammonia level.

- Ineffective breathing pattern related to ascites and restriction of thoracic excursion secondary to ascites, abdominal distention, and fluid in the thoracic cavity.

Main Article: 8 Liver Cirrhosis Nursing Care Plans

The major goals for a patient with cirrhosis are:

- Report decrease in fatigue and increased ability to participate in activities.

- Maintain a positive nitrogen balance, no further loss of muscle mass, and meet nutritional requirements.

- Decrease potential for pressure ulcer development and breaks in skin integrity .

- Reduce the risk of injury.

- Verbalize feelings consistent with improvement of body image and self-esteem.

- Increase level of comfort.

- Restore normal fluid volume.

- Improve mental status, maintain safety, and ability to cope with cognitive and behavioral changes.

- Improve respiratory status.

The patient with cirrhosis needs close observation, first-class supportive care, and sound nutrition counseling.

Promoting Rest

- Position bed for maximal respiratory efficiency; provide oxygen if needed.

- Initiate efforts to prevent respiratory, circulatory, and vascular disturbances.

- Encourage patient to increase activity gradually and plan rest with activity and mild exercise.

Improving Nutritional Status

- Provide a nutritious, high-protein diet supplemented by B-complex vitamins and others, including A, C, and K.

- Encourage patient to eat: Provide small, frequent meals, consider patient preferences, and provide protein supplements, if indicated.

- Provide nutrients by feeding tube or total PN if needed.

- Provide patients who have fatty stools (steatorrhea) with water-soluble forms of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and E, and give folic acid and iron to prevent anemia .

- Provide a low-protein diet temporarily if patient shows signs of impending or advancing coma; restrict sodium if needed.

Providing Skin Care

- Change patient’s position frequently.

- Avoid using irritating soaps and adhesive tape.

- Provide lotion to soothe irritated skin; take measures to prevent patient from scratching the skin.

Reducing Risk of Injury

- Use padded side rails if patient becomes agitated or restless.

- Orient to time, place, and procedures to minimize agitation.

- Instruct patient to ask for assistance to get out of bed.

- Carefully evaluate any injury because of the possibility of internal bleeding.

- Provide safety measures to prevent injury or cuts (electric razor, soft toothbrush).

- Apply pressure to venipuncture sites to minimize bleeding.

Monitoring and Managing Complications

- Monitor for bleeding and hemorrhage .

- Monitor the patient’s mental status closely and report changes so that treatment of encephalopathy can be initiated promptly.

- Carefully monitor serum electrolyte levels are and correct if abnormal.

- Administer oxygen if oxygen desaturation occurs; monitor for fever or abdominal pain , which may signal the onset of bacterial peritonitis or other infection .

- Assess cardiovascular and respiratory status; administer diuretics, implement fluid restrictions, and enhance patient positioning , if needed.

- Monitor intake and output , daily weight changes, changes in abdominal girth, and edema formation.

- Monitor for nocturia and, later, for oliguria, because these states indicate increasing severity of liver dysfunction.

Home Management

- Prepare for discharge by providing dietary instruction, including exclusion of alcohol.

- Refer to Alcoholics Anonymous , psychiatric care, counseling, or spiritual advisor if indicated.

- Continue sodium restriction; stress avoidance of raw shellfish.

- Provide written instructions, teaching, support, and reinforcement to patient and family.

- Encourage rest and probably a change in lifestyle (adequate,well-balanced diet and elimination of alcohol).

- Instruct family about symptoms of impending encephalopathy and possibility of bleeding tendencies and infection.

- Offer support and encouragement to the patient and provide positive feedback when the patient experiences successes.

- Refer patient to home care nurse , and assist in transition from hospital to home.

Expected patient outcomes include:

- Reported decrease in fatigue and increased ability to participate in activities.

- Maintained a positive nitrogen balance, no further loss of muscle mass, and meet nutritional requirements.

- Decreased potential for pressure ulcer development and breaks in skin integrity.

- Reduced the risk of injury.

- Verbalized feelings consistent with improvement of body image and self-esteem.

- Increased level of comfort.

- Restored normal fluid volume.

- Improved mental status, maintain safety, and ability to cope with cognitive and behavioral changes.

- Improved respiratory status.

The focus of discharge education is dietary instructions.

- Alcohol restriction. Of greatest importance is the exclusion of alcohol from the diet, so the patient may need referral to Alcoholics Anonymous, psychiatric care, or counseling.

- Sodium restriction. Sodium restriction will continue for considerable time, if not permanently.

- Complication education. The nurse also instructs the patient and family about symptoms of impending encephalopathy, possible bleeding tendencies, and susceptibility to infection.

The focus of documentation may include:

- Level of activity.

- Causative or precipitating factors.

- Vital signs before, during, and following activity.

- Plan of care.

- Response to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Teaching plan.

- Changes to plan of care.

- Attainment or progress toward desired outcome.

- Caloric intake.

- Individual cultural or religious restrictions, personal preferences.

- Availability and use of resources.

- Duration of the problem.

- Perceptio of pain, effects on lifestyle, and expectations of therapeutic regimen .

- Results of laboratory tests, diagnostic studies, and mental status and cognitive evaluation .

Here are some practice questions for this study guide .Please visit our nursing test bank page for more NCLEX practice questions .

1. Which assessment finding indicates that lactulose is effective in decreasing the ammonia level in the client with hepatic encephalopathy?

A. Passage of two or three soft stools daily. B. Evidence of watery diarrhea . C. Daily deterioration in the client’s handwriting. D. Appearance of frothy, foul-smelling stools.

1. Correct Answer: A. Passage of two or three soft stools daily.

- A: Two or three soft stools daily indicate effectiveness of the drug.

- B: Watery diarrhea indicates overdose.

- C: Daily deterioration in the client’s handwriting indicates an increase in the ammonia level and worsening of hepatic encephalopathy.

- D: Frothy, foul-smelling stools indicate steatorrhea, caused by impaired fat digestion.

2. For a client with hepatic cirrhosis who has altered clotting mechanisms, which intervention would be most important?

A. Allowing complete independence of mobility . B. Applying pressure to injection sites. C. Administering antibiotics as prescribed. D. Increasing nutritional intake.

2. Correct Answer: B. Applying pressure to injection sites.

- B: Prolonged application of pressure to injection or bleeding sites is important.

- A: Complete independence may increase the client’s potential for injury, because an unsupervised client may injure himself and bleed excessively.

- C&D: Antibiotics and good nutrition are important to promote liver regeneration.

3. A client with advanced cirrhosis has been diagnosed with hepatic encephalopathy. The nurse expects to assess for:

A. Malaise. B. Stomatitis. C. Hand tremors. D. Weight loss.

3. Correct Answer: C. Hand tremors.

- C: Flapping of the hands (asterixis), changes in mentation, agitation, and confusion are common.

- A&B: Malaise and stomatitis are not related to neurological involvement.

- D: These clients typically have ascites and edema so experience weight gain.

4. A client diagnosed with chronic cirrhosis who has ascites and pitting peripheral edema also has hepatic encephalopathy. Which of the following nursing interventions are appropriate to prevent skin breakdown?

A. Range of motion every 4 hours. B. Turn and reposition every 2 hours. C. Abdominal and foot massages every 2 hours. D. Sit in chair for 30 minutes each shift.

4. Correct Answer: B. Turn and reposition every 2 hours.

- B: Careful repositioning can prevent skin breakdown.

- A: Range of motion exercises preserve joint function but do not prevent skin breakdown.

- C: Abdominal or foot massage will not prevent skin breakdown but must be cleansed carefully to prevent breaks in skin integrity.

- D: The feet should be kept at the level of heart or higher so Fowler’s position should be employed.

5. The nurse must be alert for complications with Sengstaken-Blakemore intubation including:

A. Pulmonary obstruction. B. Pericardiectomy syndrome. C. Pulmonary embolization. D. Cor pulmonale.

5. Correct Answer: A. Pulmonary obstruction.

- A: Rupture or deflation of the balloon could result in upper airway obstruction .

- B, C, D: The other choices are not related to the tube.

Other posts from the site you may like:

- 8 Liver Cirrhosis Nursing Care Plans

- 7 Hepatitis Nursing Care Plans

- Bile Duct Stones (Choledocholithiasis)

1 thought on “Hepatic Cirrhosis”

Good effective management of cirrhosis that will help nurse student to manage patients: well done health team🙏

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Can I pay someone to write my essay?

Time does not stand still and the service is being modernized at an incredible speed. Now the customer can delegate any service and it will be carried out in the best possible way.

Writing essays, abstracts and scientific papers also falls into this category and can be done by another person. In order to use this service, the client needs to ask the professor about the topic of the text, special design preferences, fonts and keywords. Then the person contacts the essay writing site, where the managers tell him about the details of cooperation. You agree on a certain amount that you are ready to give for the work of a professional writer.

A big bonus of such companies is that you don't have to pay money when ordering. You first receive a ready-made version of the essay, check it for errors, plagiarism and the accuracy of the information, and only then transfer funds to a bank card. This allows users not to worry about the site not fulfilling the agreements.

Go to the website and choose the option you need to get the ideal job, and in the future, the best mark and teacher's admiration.

Finished Papers

Customer Reviews

Who are your essay writers?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like (While making initial visits c her assigned clients, the PN enters Robertas room. After the PN discusses the diagnosis of cirrhosis c Roberta & her husband, robertas husband asks if it is true that cirrhosis is a disease of alcoholics) The PNs response should be based on what information?, Which additional questions should the PN ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Mr. Garcia is a 43 year old male who presented to the ED complaining of nausea and vomiting x 3 days. The nurse notes a large, distended abdomen and yellowing of the patient's skin and eyes. The patient reports a history of alcoholic cirrhosis. *What initial nursing assessments should be performed?*, What diagnostic testing do ...

Cirrhosis of the Liver Conclusion. Sources. Cirrhosis of the liver is a chronic disease that is caused by long-term damage to the organ. Cirrhosis can cause major complications, including liver failure, bleeding in the esophagus or stomach, or death. Clients with cirrhosis most likely experience liver damage from:

Recently published guidelines by European Association for Studies of Liver (EASL) 3 and European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) 13 provide comprehensive overviews of nutrition in cirrhosis. Herein, we provide a case-based practical guide of the causes of malnutrition, assessments tools, daily requirements and dietary ...

300+ Nursing Cheatsheets. Start Free Trial. "Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!". ~Jordan. Cirrhosis Case Study (45 min) is mentioned in these lessons. Nursing case study for patient with cirrhosis with unfolding questions and answers. Written by ICU nurses.

UNFOLDING Reasoning Case Study: STUDENT Cirrhosis History of Present Problem: John Richards is a 45-year-old male who presents to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain and worsening nausea and vomiting the past three days that have not resolved. He is feeling more fatigued and has had a poor appetite the past month.

Educational Case: Evaluating a patient with cirrhosis. The following fictional case is intended as a learning tool within the Pathology Competencies for Medical Education (PCME), a set of national standards for teaching pathology. These are divided into three basic competencies: Disease Mechanisms and Processes, Organ System Pathology, and ...

Any chronic liver disease, including excessive alcohol intake and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), can cause cirrhosis. The specific cause of cirrhosis may not be determined in all patients. The most common causes of cirrhosis in the United States are chronic hepatitis C infection and alcohol- induced liver disease.

A. Beef tips and broccoli rabe. B. Pasta noodles and bread. C. Cucumber sandwich with a side of grapes. D. Fresh salad with chopped water chestnuts. 6. During your morning assessment of a patient with cirrhosis, you note the patient is disoriented to person and place.

Cirrhosis NCLEX Review. This NCLEX review will discuss cirrhosis. As a nursing student, you must be familiar with cirrhosis along with how to care for a patient experiencing this disease. These type of questions may be found on NCLEX and definitely on nursing lecture exams. Don't forget to take the cirrhosis quiz.

UNFOLDING Reasoning Case Study: STUDENT Cirrhosis History of Present Problem: John Richards is a 45-year-old male who presents to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain and worsening nausea and vomiting the past three days that have not resolved. He is feeling more fatigued and has had a poor appetite the past month.

INTRODUCTION. Alcohol is a major risk factor for liver disease in general, and for liver cirrhosis in particular.(1-3) In fact, about half of the liver cirrhosis burden of morbidity and mortality would disappear in a world without alcohol.() Mortality from liver cirrhosis has been on the rise in the US() and Europe,() more so in women than in men.. Alcohol consumption is partly responsible ...

UNFOLDING Reasoning Case Study: STUDENT Cirrhosis History of Present Problem: John Richards is a 45-year-old male who presents to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain and worsening nausea and vomiting the past three days that have not resolved. He is feeling more fatigued and has had a poor appetite the past month.

Hepatic cirrhosis is a chronic hepatic disease characterized by diffuse destruction and fibrotic regeneration of hepatic cells. As necrotic tissue yields to fibrosis, this disease alters liver structure and normal vasculature, impairs blood and lymph flow, and ultimately causes hepatic insufficiency. The prognosis is better in noncirrhotic ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Which nursing intervention best promotes accurate and effective communication?, The nurse continues the focused risk assessment by asking about etiologic factors related to cirrhosis. Which assessment finding provides the most likely indication that the client is at high risk for cirrhosis?, Which nursing interventions are ...

current issue. current issue; browse recently published; browse full issue index; learning/cme

Case Study Question 1 of 6. The nurse is caring for a 67-yr-old male with history of alcohol use disorder and cirrhosis admitted to the medical-surgical unit. Nurses' Notes DAY 1 1000. Admitted with ascites and confusion; oriented to person only. Has 25-yr history of alcohol use disorder, mild hypertension, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Our essay help exists to make your life stress-free, while still having a 4.0 GPA. When you pay for an essay, you pay not only for high-quality work but for a smooth experience. Our bonuses are what keep our clients coming back for more. Receive a free originality report, have direct contact with your writer, have our 24/7 support team by your ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Which information about cirrhosis should the nurse remember when responding to Frank's wife?, Which question is most important for the nurse to include when assessing the client for etiologic factors related to cirrhosis?, When nursing intervention is important prior to a paracentesis? and more.

Review material on Liver disease and examples. Professor Jensen. Fall 2017 study questions chronic liver diseases case study: mr. is 48 year old divorced father