We need your support today

Independent journalism is more important than ever. Vox is here to explain this unprecedented election cycle and help you understand the larger stakes. We will break down where the candidates stand on major issues, from economic policy to immigration, foreign policy, criminal justice, and abortion. We’ll answer your biggest questions, and we’ll explain what matters — and why. This timely and essential task, however, is expensive to produce.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

The uproar over the New Yorker short story “Cat Person,” explained

How a short story about a bad date sparked a conversation about gender, sex, and privilege.

by Constance Grady

This past weekend, the biggest story on social media was not about a powerful man who had sexually assaulted someone, or something the president said on Twitter. Charmingly, as if we were all at a Paris salon in the 1920s, everyone had an opinion about a short story.

Specifically, the story “Cat Person” by Kristen Roupenian, which appeared in the New Yorker. The story centers on a 20-year-old college student named Margot who gradually falls into flirtation with a man named Robert.

As Margot and Robert’s relationship develops, and the balance of power between them shifts back and forth, she cycles rapidly between imagining Robert as an adorable naif who is overwhelmed by her young beauty and sophistication, and imagining him as a vicious and murderous brute.

“Margot keeps trying to construct an image of Robert based on incomplete and unreliable information, which is why her interpretation of him can’t stay still,” Roupenian said in an interview . “The point at which she receives unequivocal evidence about the kind of person he is is the point at which the story ends.”

As the story began to go viral, a series of narratives began to emerge around it: It was a good story. No, it was a bad story, and people who thought it was good had not read enough short stories. No, it actually was good, and people who thought it was not good were sexist. Margot’s internal monologue about Robert’s body constituted fat shaming. No, she was simply a good old-fashioned unlikable narrator. Robert was the villain. No, Robert was the hero. Wait, was “Cat Person” fiction, or a nonfiction personal essay?

Much of the discomfort and controversy swirls around the character of Margot and all that she represents: a white, college-educated, straight, relatively thin young woman. She’s both a figure of enormous privilege and a figure who is disempowered, and most of the discourse about the story has focused on trying to figure out exactly where she stands.

Spoilers for “Cat Person” follow.

For many readers, “Cat Person” captures how it feels to be a woman in her 20s

Where “Cat Person” is acclaimed, it’s mostly for the eerie accuracy in depicting what dating is like for a 20-year-old woman. It captures the interiority of a certain kind of (middle-class, thin, white) woman perfectly: the guessing at what might possibly be going on in a man’s head, the slow piling-up of red flags that cannot quite be named and as such are dismissed, the desperate need to be considered polite and nice at all costs.

The need to be thought of as a nice girl is what drives Margot to sleep with Robert at the very moment that she realizes she is really not all that attracted to him: “The thought of what it would take to stop what she had set in motion was overwhelming,” Roupenian writes. “It would require an amount of tact and gentleness that she felt was impossible to summon.”

And as Roupenian explores the interior of Margot’s psyche with breathtaking thoroughness in the foreground, Robert is in the background, throwing up warning sign after warning sign: He is older; he is controlling; he has a chip on his shoulder; he seems preoccupied with the idea of Margot sleeping with someone else.

All of these moments are innocuous in and of themselves, but together, they acquire so much force that if you are a person who has dated men, watching Margot blithely convince herself that Robert is a good guy feels like watching a horror movie. “Don’t go through that door!” you want to shout. “Call the cops!” When Robert calls Margot a whore at the end of the story, it feels inevitable. You saw that one coming.

Familiarity is what gives the story its aesthetic power. You recognize both the danger in the background and the interiority in the foreground. When they come together, there’s a pleasurable jolt: Yes, that is how it is; this is true .

And for that kind of careful, detailed attention to be applied to the practice of dating as a young woman — and for it to appear in a publication like the New Yorker — feels almost shocking. In a literary establishment filled with stories about the subjectivity of straight white men, for young women, it’s validation on a huge scale: Yes, this is what the world is like, and no, you’re not crazy.

“Cat Person” contradicts our culture’s tendency to treat women’s concerns as unliterary

For some readers, the fact that “Cat Person” centers on the subjectivity of a young woman made it inherently unliterary and unworthy. So much of the criticism surrounding “Cat Person” is weighted by misogyny that the Twitter account Men React to Cat Person sprang into being to chronicle it all.

Our culture tends to consider the things that happen to men to be compelling, universal, and worthy of literary attention, and the things that happen to women to be trivial, uninteresting, and petty.

A story like John Updike’s “A&P,” in which a man watches women and thinks about how hot they are, is a literary classic that is regularly taught in high schools. The literary canon’s attempts to delve into women’s heads, meanwhile, tend to look like C.S. Lewis’s “Shoddy Lands,” in which a woman’s mental landscape is devoted entirely to her own grotesque body, and the absence of the male gaze in her head is a moral affront. Women’s short stories about their own interiority rarely make it into the literary canon at all.

So when a story specifically about the experiences of a young woman takes off and becomes a major cultural touchstone, it’s threatening to the established order of things. But I thought lady things were Bad , a man might say. I don’t know how to empathize with ladies!

The trivializing of women’s stories also plays into one of the persistent oddities surrounding “Cat Person”; namely, the frequency with which readers have called it an “article” or an “essay” or generally treated it as a piece of nonfiction rather than as a short story.

“Cat Person” does not bear any of the signifiers of a personal essay: It is told in the third person, not the first, and it appears in the New Yorker’s fiction section, with FICTION splashed at the top of the page. Nonetheless, the default response from many seemed to be to treat it as an essay rather than as a short story.

Perhaps that’s because it does have one signifier that we associate with the personal essay. It has an intimate, confessional feminine narrative voice, the kind of voice we have learned to associate with “It Happened to Me” –style first-person narratives. Women’s subjectivity is not for serious literary fiction, after all; it’s for unserious, uninteresting, unpaid-for online writing. Treating “Cat Person” as a piece of nonfiction is another way to dismiss its literary merit, and we’re able to do that because it was written by a woman.

“Cat Person” is not the only short story out there about young women

But it’s worth noting that “Cat Person” is not the only short story in the world that pays careful attention to what it feels like to be a young woman dating in a world of dangerous men. Mary Gaitskill has devoted story after story to that theme since the 1980s, and so has Lorrie Moore. More recently, Lauren Holmes delved into the concern in her 2016 story collection Barbara the Slut .

So to some observers, it has been puzzling to watch “Cat Person” take off so rapidly. Short stories are read comparatively less often than book-length fiction , which suggests that many of the readers who commented publicly on “Cat Person” weren’t people who read lots of short stories. Yet they were discussing “Cat Person” as though it were the only story in the world capable of granting subjectivity to young women.

And the idea that few of the people lauding “Cat Story” were all that familiar with short stories stung particularly badly given the current literary moment. Over the past few months, short story fans have been critiquing the role of the short story in the literary world. Short stories are treated like the redheaded stepchildren of publishing, they argue, as though they’re worthy of a reader’s attention only because the stories are so short that they require very little of it.

“There seems to be an idea that people, with those shortened attention spans of theirs, want quick and easy reads!” wrote Brandon Taylor on LitHub . “If short stories are going to compete with Netflix, then we better make sure that people know that short stories can be read quickly!”

But, he argued, “Short stories are not aphorisms. Short stories are not the chocolate sampler hurriedly purchased as a last-minute gift idea. The expedience of a short story is certainly a feature in the way that feathers are a feature of a bird. It’s a brute fact.”

The short story is a medium already granted precious little respect — and now people barely acquainted with it were holding up “Cat Person” as exceptional rather than typical. Hackles rose; not necessarily at the story’s readers, but at the literary culture that makes it so easy to skate by on knowing the three short stories everybody reads in 10th-grade English, and to treat the great short stories that are written every year as afterthoughts.

Depending on whom you ask, Margot’s disgust with Richard’s body is either honest or fat shaming

Adding to the backlash against “Cat Person” was the sense that its narrative is fat shaming, and that it is constructed around the unexamined idea that fat bodies are inherently gross and bad.

Margot first realizes that she does not want to have sex with Robert when she sees “his belly thick and soft and covered with hair.” And as her revulsion grows, it’s constantly tinged with disgust at his weight: He “weighs her down.” His penis is “only half visible beneath the hairy shelf of his belly.” Her mental image of herself is one in which she’s “naked and spread-eagled with this fat old man’s finger inside her.”

Margot is not obligated to be attracted to Robert, but the idea that his fat body is intrinsically disgusting, some critics have argued, reinforces a sense that fat people are themselves inherently disgusting, even worthless.

“It feels like shorthand there to denote how objectively undesirable we are and how our bodies fool (via clothes) and trap (via weight),” wrote author Ana Mardoll in a now-deleted tweet, going on to add that she found Margot relatable, “until she saw a body like mine and recoiled and I realized THAT was the moment she saw the guy as bad.”

Margot is not an aspirational character or a role model, but a portrait of a flawed young woman, bringing context to the fat shaming. She’s riddled with all of the unexamined prejudices our culture teaches young women to feel: that nice girls are polite, that turning down sex once it’s been initiated is rude, and that fat people are gross.

But the sheer insistence of the story that Robert’s fat is the thing that makes him uniquely unacceptable remains troubling. In Margot’s horror at Robert’s body, “Cat Person” seems to be flattening the category of fatness into the category of things that are sexually disgusting.

This critique highlights Margot’s privilege. It is unusual, if not exceptional, for short stories about female subjectivity to become quite as popular as “Cat Person” — but it’s very normal for all kinds of stories to include offhand statements about how fat people are gross. As just one example, Jessica Jones , a fantastic TV show that is devoted to female interiority, has featured a snide joke about a fat woman eating a cheeseburger while on a treadmill.

“Cat Person” is not just speaking truth to power; it’s also reinforcing existing power structures.

It’s pretty delightful that we’re all sitting around debating a short story, though

Regardless of whether or not “Cat Person” is a great short story or just an okay short story, whether it’s deeply subversive or highly problematic, it has been exciting to see the cultural discourse revolve around a short story for a spell. It’s a reminder of how immensely powerful and valuable fiction can be, and why it’s worthwhile to pay attention to it and learn from it.

If you enjoyed “Cat Person” and you would like to read similar short fiction, here are some options, as crowd-sourced via Twitter :

- Mary Gaitskill is the OG when it comes to writing about women and sex. If you want something “Cat Person”-esque, start with “Something Better Than This.”

- Lauren Holmes writes the millennial woman’s voice with a deadpan glee, and her treatment of sex is elegant and nuanced. Her collection is called Barbara the Slut and Other People .

- For sheer overwhelming dread at how the threat posed by men can slowly creep up on women, it’s hard to beat Carmen Maria Machado. Start with “The Husband Stitch,” and from there you can move on to the rest of Her Body and Other Parties .

Happy reading!

- Internet Culture

Most Popular

- A thousand pigs just burned alive in a barn fire

- Who is Ryan Wesley Routh? The suspect in the Trump Florida assassination attempt, explained.

- Sign up for Vox’s daily newsletter

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- The messy Murdoch succession drama, explained

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Culture

A minor upset for Best Comedy Series couldn’t keep the rest of the night from feeling predictable.

Please pay your respects to the new queen of TV killer thrillers.

The right thinks that hot girls can “kill woke.” What?

The truth behind the ongoing controversy over the highly memeable dancer.

The highly coveted endorsement comes after a year of paranoid speculation.

From prebiotic sodas to collagen waters, beverages are trying to do the most. Consumers are drinking it up.

10 Lessons from “Cat Person” on Character Interiority

“Cat Person,” by Kristen Roupenian, was published in the Dec. 11 th , 2017 edition of The New Yorker and it made waves. It’s easily the most talked-about story of the year, but it may also be the most-talked about short story in the modern digital age. There were corners of the internet that never discuss short stories discussing this short story. It did a lot of things right with its craft, but far and away its clearest accomplishment, I feel, is the author’s handling of character interiority. When I say “interiority,” I mean emotion, perception, and thought. This is a story that opens a window into the internal processes that can lead someone to make what the protagonist dubs “the worst life decision [she has] ever made.”

So I’d like to investigate Roupenian’s craft of interiority in some depth. If you haven’t read the story yet, read it first . And a warning, I suppose: it involves sex, so, you know, maybe don’t use this lesson in a high school creative writing course.

The Techniques

1. stimulus, response.

The first rule of interiority is that it needs a trigger. It needs a cause. Interiority is reaction.

Roupenian routinely gives us a motivating stimulus and then a response. Here’s an example:

On the drive, he was quieter than she’d expected, and he didn’t look at her very much. Before five minutes had gone by, she became wildly uncomfortable, and, as they got on the highway, it occurred to her that he could take her someplace and rape and murder her; she hardly knew anything about him, after all.

See that? His silence is the external stimulus. It happens outside of Margot. Emotion is typically the first reaction (before thought). In this case, she’s uncomfortable. It’s a feeling. And from that feeling comes a thought: “it occurred to her that he could take her someplace and rape and murder her.” External stimulus, emotion, thought.

2. Feelings precede thought

I think it’s worth separating this out as its own guideline. This is not to say that you need to state the feeling every time you state a thought. It’s just that it’s human nature to feel first and think next. Roupenian does this constantly, even with little things like this one: “He opened his laptop, an action that confused her, until she understood that he was putting on music.” Or this: “‘I like it,’ she said, truthfully, and, as she did, she identified the emotion she was feeling as relief.” Margot feels the emotion and then consciously identifies it (through thinking about it).

3. Chained interiority

The stimulus for interiority is usually external but can sometimes be other interiority . That is, an external stimulus might lead to an emotion and/or a thought, which in turn leads to an emotion, which then leads to another thought. Margot is a very self-conscious character, who does this all the time. We see clear chained interiority during the first kiss:

He kissed her then, on the lips, for real; he came for her in a kind of lunging motion and practically poured his tongue down her throat. It was a terrible kiss, shockingly bad; Margot had trouble believing that a grown man could possibly be so bad at kissing. It seemed awful, yet somehow it also gave her that tender feeling toward him again, the sense that even though he was older than her, she knew something he didn’t.

The kiss (external stimulus) spurs unstated disgust (feeling) spurs her incredulity that he could be so bad (thought) spurs tenderness (feeling) and a “sense” of her power over him (a “sense” is interesting; I’d call it unconscious thought).

As Robert Olen Butler points out, one of the ways in which we experience emotion is to flash to the past. “Moments of reference in our past come back to us in our consciousness, not as ideas or analyses about the past, but as little vivid bursts of waking dream; they come back as images, sense impressions.” Roupenian uses this technique on occasion, like during the awkward interaction after the movie, when Margot thinks back to his proposal that they see this Holocaust movie for their date:

Maybe, she thought, her texting ‘lol r u serious’ had hurt him, had intimidated him and made him feel uncomfortable around her. The thought of this possible vulnerability touched her, and she felt kinder toward him than she had all night.

You can see there how the thought about the past then has consequence for her subsequent present-time emotion.

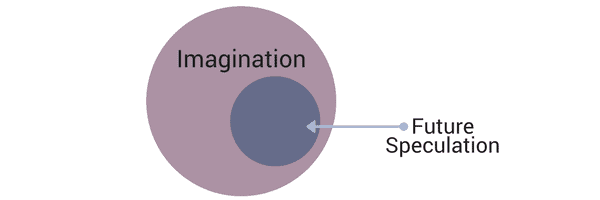

5. Future and Imagination

In addition to remembering the past, we have what Robert Olen Butler calls “flashes of the future . . . of something that has not yet happened or that may happen, something we desire or fear or otherwise anticipate.” This is the fourth expression of emotion he identifies. But speculation of the future is rooted in the broader category of imagination . I want to be careful not to conflate these two modes of experiencing emotion. There is a distinction between future-thinking and imagination. Namely, any anticipation of the future is an act of imagination, but not all acts of imagination are speculations of the future.

5a. Imagination

Margot sometimes goes on imaginative riffs to a parallel universe (that don’t involve the future). Here’s one of the most central imaginative riffs of the story:

As they kissed, she found herself carried away by a fantasy of such pure ego that she could hardly admit even to herself that she was having it. Look at this beautiful girl, she imagined him thinking. She’s so perfect, her body is perfect, everything about her is perfect, she’s only twenty years old, her skin is flawless, I want her so badly, I want her more than I’ve ever wanted anyone else, I want her so bad I might die.

But certainly, some of Margot’s imaginative riffs, like this other very central one, look toward the future as well:

“We should probably just kill ourselves,” she imagined saying, and then she imagined that somewhere, out there in the universe, there was a boy who would think that this moment was just as awful yet hilarious as she did, and that sometime, far in the future, she would tell the boy this story.

In the NY Times interview , Roupenian states, “Margot’s empathetic imagination is working on overdrive . . . throughout the story. Her skills at reading other people make her socially adept, but because imaginative empathy is still, fundamentally, imagination, she is also easily misled.” Clearly, then, Margot’s imaginative interiority is pretty crucial to this story.

6. Implied, unstated interiority

Thus far we’ve been discussing interiority reactions that are stated explicitly. Emotion is named, thought is named, a flash to the past is included, or speculation (fantasy or future) is relayed. Sometimes, however, the interiority is left entirely implied. It is not explained in any way. We don’t get to see what’s in Margot’s head. We’re just given an external reaction, the internal cause of which is left invisible to us. We therefore are left to intuit.

Some of the awkward post-coital dialogue is rendered with no stated interiority. Like this exchange:

“Are you still awake?” he asked, and she said yes, and he said, “Is everything O.K.?” “How old are you, exactly?” she asked him.

And just a bit later, this one:

“Gotta get back to the dorm room,” he said, voice dripping with sarcasm. “Yep,” she said. “Since that’s where I live.”

An author may be tempted to explain what’s going through the character’s head before replying the way Margot does, but is it really necessary? Mostly, you want to leave the explanations for complex internal reactions that we can’t otherwise intuit. Which brings us to . . .

7. Complex feelings

A big part of what makes Margot’s interiority so compelling is its complexity. Take a look at this long paragraph and think about how a film adaptation of the scene would have a very hard time capturing all of this:

Margot laughed along with the jokes he was making at the expense of this imaginary film-snob version of her, though nothing he said seemed quite fair, since she was the one who’d actually suggested that they see the movie at the Quality 16. Although now, she realized, maybe that had hurt Robert’s feelings, too. She’d thought it was clear that she just didn’t want to go on a date where she worked, but maybe he’d taken it more personally than that; maybe he’d suspected that she was ashamed to be seen with him. She was starting to think that she understood him—how sensitive he was, how easily he could be wounded—and that made her feel closer to him, and also powerful, because once she knew how to hurt him she also knew how he could be soothed. She asked him lots of questions about the movies he liked, and she spoke self-deprecatingly about the movies at the artsy theatre that she found boring or incomprehensible; she told him about how much her older co-workers intimidated her, and how she sometimes worried that she wasn’t smart enough to form her own opinions on anything. The effect of this on him was palpable and immediate, and she felt as if she were petting a large, skittish animal, like a horse or a bear, skillfully coaxing it to eat from her hand.

Margot doesn’t feel that Robert’s poking fun at her is fair, but rather than be hurt, she wonders whether he’s been hurt. Thus begins her speculations about Robert’s feelings and her ensuing belief that she is starting to understand him. She then feels closer to him and that she has power over him.

That’s pretty complicated. We begin with a stimulus which she’d be justified in feeling hurt about, and by a pure interior chain of reactions, we land on her feeling power over him.

Indirect interiority

A large part of what makes Roupenian’s rendering of interiority so masterful is not only that she makes Margot’s interiority so rich and so relatable for so many; it’s that she also renders Robert’s interiority expertly. That is, she gives him very authentic male hangups and insecurities. And in some ways, what she does with Robert is even more impressive because the narrator is limited to Margot’s perspective. So everything Robert is feeling or thinking has to be conveyed in some other way that through stated interiority. I’m referring to this as “indirect interiority,” and though the following tips aren’t different techniques, per se, from the list above, I think it’s worth specifying and elaborating upon how Roupenian pinpoints Robert’s feelings.

8. External reaction

At times, Robert’s reactions to Margot are very revelatory. Reaction is, in general, more revelatory than action because in reaction, we have a clear understanding of the context and can thus intuit the causal chain that leads to the reaction. As I’ve said, the typical order of things is feeling, thought, reaction. We can’t see the feeling or thought, but in seeing the stimulus and the reaction, we can guess at the feeling and thought. Thus, when Roupenian writes the following, we have some ideas about what motivates Robert:

But, when Robert saw her face crumpling, a kind of magic happened. All the tension drained out of his posture; he stood up straight and wrapped his bearlike arms around her. “Oh, sweetheart,” he said. “Oh, honey, it’s O.K., it’s all right. Please don’t feel bad.”

He is empowered by his feeling needed and by Margot’s vulnerability. As humans, we’re equipped to make sense of external reactions like this; such empathic response is built into us. And one of Butler’s expressions of emotion is “a sensual response that sends signals outside of our body–posture, gesture, facial expression, tone of voice, and so forth.” By showing those sensual responses, we can communicate a lot about the internal.

9. POV-character judgments

We can’t fully trust the judgments of any perspective character, but when they’re backed up with some evidence (of external actions), then we may be more swayed. Margot has a lot of erroneous judgments, but sometimes we get ones that feel accurate:

As they talked, she became increasingly sure that what she’d interpreted as anger or dissatisfaction with her had, in fact, been nervousness, a fear that she wasn’t having a good time. He kept coming back to her initial dismissal of the movie, making jokes that glanced off it and watching her closely to see how she responded. He teased her about her highbrow taste, and said how hard it was to impress her because of all the film classes she’d taken, even though he knew she’d taken only one summer class in film.

I find Margot’s interpretation of Robert to be pretty convincing. And I think the final several lines of the story demonstrate his nervousness and insecurity very clearly.

But perhaps even more convincing example is this:

“You don’t need to apologize,” he said, but she could tell by his face, as well as by the fact that he was going soft beneath her, that she did.

10. Seeming

Michael Byers argues that sometimes, impressions of how something seems can often bring a description to life. This is, of course, just an extension of #9 above, because narration of something seeming is inflected with the perspective character’s assessment of things, but this is such a quick and nearly-invisble way of accomplishing #9; I wanted to pinpoint it. Here’s an example from “Cat Person”:

At the front door, he fumbled with his keys for what seemed a ridiculously long time and swore under his breath. She rubbed his back to try to keep the mood going, but that seemed to fluster him even more, so she stopped.

In this case, Margot’s impression of the Robert’s actions seems accurate.

Bringing it all together

In the heart of the sex scene, we can see almost every technique above applied in rapid succession. Causal chains, reaction, imagination, memory, implied interiority, complexity galore. I’ll present it here without my commentary, but you should be able to find every technique above, with the exceptions, if we’re being strict, of #5b and #10.

“You don’t have to be nervous,” he said. “We’ll take it slow.” Yeah, right, she thought, and then he was on top of her again, kissing her and weighing her down, and she knew that her last chance of enjoying this encounter had disappeared, but that she would carry through with it until it was over. When Robert was naked, rolling a condom onto a dick that was only half visible beneath the hairy shelf of his belly, she felt a wave of revulsion that she thought might actually break through her sense of pinned stasis, but then he shoved his finger in her again, not at all gently this time, and she imagined herself from above, naked and spread-eagled with this fat old man’s finger inside her, and her revulsion turned to self-disgust and a humiliation that was a kind of perverse cousin to arousal. During sex, he moved her through a series of positions with brusque efficiency, flipping her over, pushing her around, and she felt like a doll again, as she had outside the 7-Eleven, though not a precious one now—a doll made of rubber, flexible and resilient, a prop for the movie that was playing in his head. When she was on top, he slapped her thigh and said, “Yeah, yeah, you like that,” with an intonation that made it impossible to tell whether he meant it as a question, an observation, or an order, and when he turned her over he growled in her ear, “I always wanted to fuck a girl with nice tits,” and she had to smother her face in the pillow to keep from laughing again.

I challenge anyone to write a sex scene so fraught with authentic character internal struggles, especially one that so adeptly captures our received heterosexual gender concepts and all the baggage that accompanies such role playing.

Want more lessons on narration and interiority ? Check out these previous articles:

- External action and interiority

- Information vs. Action

Author, Narrator, Character

- Writing Emotion

Save Save Save Save

GET SERIOUS ABOUT WRITING CRAFT

The newsletter delivers thought-provoking tips, questions, and resources to your inbox, and alerts you to new articles.

Varieties of Omniscience

How to Use Objects to Create More Powerful Stories

Writing Character Emotion

9 Responses

- Pingback: 4 Common Failures in Story Cause/Effect | Storm Writing School

- Pingback: Create Sentiment; Avoid Sentimentality | Storm Writing School

- Pingback: Formatting Character Thoughts | Storm Writing School

- Pingback: The Problem with “Show, Don’t Tell” (August Author Toolbox) | Storm Writing School

- Pingback: The Pitfalls of Emotional Body Language in Your Writing (October Author Toolbox) | Storm Writing School

- Pingback: The Key to Epiphanies, Realizations, and Moments of Clarity (January Author Toolbox) | Craft Articles

- Pingback: 12 Ways to Be an Invisible Writer | Craft Articles

- Pingback: The Pitfalls of Emotional Body Language in Your Writing | Storm Writing School

- Pingback: Showing Character’s Interior Lives – Carrie Jones Books

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Welcome to Storm Writing School!

- Check out the Mission

- Read the About page

- Scan the index of posts below

Find these resources valuable? Consider a tip by clicking the jar below:

Index of Posts

100 Books Published in 2023 for Your TBR Pile

12 Ways to Be an Invisible Writer

3 Techniques for Creating Tension

4 Common Failures in Story Cause/Effect

A Compendium of Novel Structure Resources

A Glossary of Assorted Writing Craft Terms

Action vs. Information: Convey Info without Stalling the Story

Approaching the Workshop

Captivating Protagonists: The Essentials

Centrifugal Forces: How a Character Doesn’t Want What They Desire

Common Problems in Manuscripts

Create a Moving Character Arc

Create Sentiment; Avoid Sentimentality

Creating Suspense

Dealing with Criticism and Rejections

Delight: The Secondary Source of Reader Engagement

Dramatic Prognosis: a tool for designing strong plots and improving weak ones

Earning Story Events

Escalating Complications

Exposition in Dialogue

Formatting Character Thoughts

Freytag’s Pyramid Doesn’t Deserve the Hate

How a Scene List Can Help Your Revision

How and Why to Write Your Back-Cover Synopsis Early

How to Create Compelling Story Action

How to Create Story Momentum

How to Maintain Perspective When Encountering Writing Advice

How to Make a DIY Writing Retreat

How to Write While You’re Freaking Out

How Your Attitude and Approach Toward Habits Can Revitalize Your Writing Practice

Irony is Central to Storytelling

Juggle External Action and Interiority

Narrating Deep or Shallow: The Spectrum of Psychic Distance

Novel Structure: An Aggregate Paradigm

Page-level Storytelling: Four Ways to Break Down Your Narration

Prepping for Beta Reading

Readers to Help You Write Your Book

Revision for Haters

Scene vs. Summary

Should You Use Dialogue Tags Other Than “Said”?

Show, Don’t Tell Disambiguation

Story Consumption: How to Read Like a Writer

Stretch Tension to Maximize Suspense

Subjective Conflict

The Case for Messy Character Motivation

The Case for Pantsing

The Character Mixing Board

The Essence of Standout Characters

The Essentials of Orienting Your Reader

The Key to Epiphanies, Realizations, and Moments of Clarity

The Key to Reader Engagement

The Pitfalls of Emotional Body Language in Your Writing

The Problem with “Show, Don’t Tell”

The Storm Writing School Mission

The True Source of Voice

The Two Imperatives for Compelling Dialogue

The Two Roles of the Beginning

Theme Is Not Optional

Time Digressions in Narration

To Filter or Not to Filter

Tools for Big Picture Editing of Your Novel

Triangulate Dialogue

Turning Points Propel Your Story

Two Conflicts: Problems vs. Obstacles

Use “Urgent Story Questions” to Create Tension

Use Beats to Move Characters within Scenes

Verisimilitude: What it is and how it works

What Does the Inciting Incident Actually Do?

What Is a Beat, Anyway?

Why Most Writing Rules Can Be Broken

Why the Hero’s Journey May Not Be Right for Your Story

Why You Need Strong Antagonists in Your Story

Why Your Story’s Conflict May Fail to Grip Readers

Your Writing Needs to Be Better Than Game of Thrones

Copyright © 2024 Storm Writing School, all rights reserved.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

“Cat Person” and Me

Kristen roupenian’s viral story draws specific details from my own life. i’ve spent the years since it published wondering: how did she know.

One night in December of 2017, I saw Call Me by Your Name for the second time, alone, at the Alamo Drafthouse in a mall in Downtown Brooklyn. When I emerged from the theater after lingering for a moment to let my tears dry, I checked my phone. I had dozens of text messages—some from close friends, but many from old co-workers, classmates, and people I hadn’t spoken to in years. Most of them contained a link to a New Yorker short story. I recognized the photo that accompanied the piece because I’d idly flipped past it in the magazine earlier that day and remembered being a bit grossed out by the image: a close-up of two pairs of lips.

“Is this about you?” the text messages read. “Did you write this under a pen name? Did Charles?” My stomach dropped. Charles and I had broken up two years prior, and though we were still in touch on occasion, I’d distanced myself from the relationship. (I’ve chosen to use a pseudonym for him here.) Seeing his name in these messages was jarring. I shoved my phone in my pocket and made my way down the escalator and toward the A train. Once aboard, I clicked the link again and started reading.

Kristen Roupenian’s “ Cat Person ” is a fictional story that follows its protagonist, Margot, a college sophomore, as she navigates a relationship with an older man named Robert. They meet when he flirts with her at the local theater where she works concessions—he orders Red Vines—and they text for a while before going on a date. Throughout their time together, Margot vacillates between feeling disgusted by him and wanting more. Eventually, when they sleep together, Margot finds herself repulsed, creating an imaginary boyfriend in her head to laugh about the awful sex with later. In the following weeks, as she attempts to ghost him, Robert sends Margot texts that become increasingly aggressive, culminating in an encounter at a campus bar that leads him to text her: “Whore.”

“Cat Person” was published at the height of the #MeToo movement, at a time when many women were reassessing past relationships through a new lens, and it clearly resonated with readers. Roupenian’s story was the first work of short fiction to ever go viral; as the Guardian put it, “Cat Person” “sent the internet into meltdown.” Now it’s being made into a movie starring Nicholas Braun, who plays Cousin Greg on Succession . But for me, the experience of reading it was particularly uncanny. I remember that, as I scrolled, I had to sit down on the train instead of leaning against the door as usual because I needed the added stability.

Some of the most pivotal scenes—the sexual encounter and the hostile text messages—were unfamiliar to me. But the similarities to my own life were eerie: The protagonist was a girl from my small hometown who lived in the dorms at my college and worked at the art house theater where I’d worked and dated a man in his 30s, as I had. I recognized the man in the story, too. His appearance (tall, slightly overweight, with a tattoo on his shoulder). His attire (rabbit fur hat, vintage coat). His home (fairy lights over the porch, a large board game collection, framed posters). It was a vivid description of Charles. But that felt impossible. Could it be a wild coincidence? Or did Roupenian, a person I’d never met, somehow know about me?

I met Charles my senior year of high school at a burger restaurant in a strip mall. He was a server; I was a host. He was older than I was—I’d pegged him as in his late 20s. At the time, I was waiting to hear about my pending acceptance to the University of Michigan. Having recently returned to his home state after breaking off an engagement with a woman in Los Angeles, Charles was applying to work in the U of M biology labs.

Among a cast of 20-to-40-year-olds that included an Iraq war veteran and a waiter who unrelentingly tried to convince me to play Dungeons & Dragons, Charles stood out. I watched him scroll through Instagram—this was 2012, and he was the oldest person I’d ever seen use the app—and laughed when he successfully convinced the manager to let him print a goofy nickname on his nametag. We talked about climate change, the board games we played instead of making small talk with our families, and my cat, which happened to look like his roommate’s.

He wrote the names of songs on receipt paper and handed them to me between his trips to deliver burgers to tables. I stuffed them in my apron, then took them out when I got home, creating a playlist that began with Real Estate’s “Beach Comber.” He drew me a map to his favorite hole-in-the-wall taco place on the back of a “build your own burger” sheet. I taped it to my bedroom wall between my friends’ senior photos and drove there with a classmate after our AP calculus test. I asked him to buy me vodka from Target. Later, drunk with my friends for one of the first few times in my life, I texted him. We made Vine accounts at the same time, and I started recording six-second snippets of my life and imagined him watching them.

That spring, we went to see Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby at the multiplex. He didn’t have a car—for environmental reasons, he vowed to never own one—so I drove us there after our shift. We didn’t touch, but it was clearly a date. He started burning me CDs: Beach House, Panda Bear, Oasis. He borrowed Party Down on DVD for me from the library. Talking to Charles felt exciting, like a peek into my future. Finally, someone who cared about the things I was talking about. Finally, someone I could learn from.

“How old are you?” I asked him after we kissed for the first time. His answer, a hesitant “33,” didn’t scare me. I felt empowered by my ability to attract a fully formed adult and enticed by the forbidden nature of our potential relationship. I smiled and kissed him again.

Soon he got the lab job, left the restaurant, and moved into a house with a porch on Ann Arbor’s Old West Side, where, I learned, the cool grad students lived. At my college orientation, I imagined myself passing him on campus between classes, meeting up to share iced coffees on the steps of Angell Hall. By July, we were official.

“I’m on antidepressants,” he told me one day, avoiding eye contact. No one had ever told me they were on antidepressants before. We walked to the river and ate snacks from Trader Joe’s. “I am never this happy,” he said.

In August, I moved into a dorm with a friend from high school who didn’t approve of my relationship’s 15-year age gap. I rode the city bus to Charles’, where he read my essays and student newspaper op-eds while we drank Dark ’n’ Stormies. We painted the rooms of his house together. He picked out a bike for me, and we rode around town, falling in love. When he sent me a Craigslist post for a job at the local art house movie theater, I applied and was hired.

On his way home from work, Charles would wait in the box office line to drop off baked goods for me. After my shifts, I biked straight to his house. I made plans to rent an apartment with some girls from my econ class the following year, but they told me they’d changed their minds when they found out about my older boyfriend.

Every time I had to tell someone about Charles I got nervous—I assumed each potential new friendship would end the second they found out about us. Every few months we would ride the Amtrak to Chicago for a weekend in a city where no one would recognize us.

Out of a series of board game nights Charles organized at a local brewery, we began making friends together. One of them, David, moved in with him. For the seven months he lived there, we felt like a family. When he moved away, Charles and I adopted two cats from the humane society—Mochi and Apricot. We gave them each one of our last names. “I’m growing up too fast because I fell in love with you,” I wrote in my journal. “It scares me that I want to be with you forever.”

With Charles’ encouragement, I applied to a program to spend a semester studying in Detroit at the end of my sophomore year. Suddenly an hour away from Ann Arbor and unable to rely on Charles for constant guidance and validation, I began making friends my own age. When I returned, he accused me of all but forgetting he existed while I was gone. I couldn’t argue with him: I had finally found community, and I was happier than I’d been in years.

Our breakup was drawn out over months. Finally, in the summer of 2015, we called it quits and started seeing other people. He seemed bruised but understood. In any case, we never cut each other off entirely. When I graduated college, he left a book, bike socks, and a card in a bag on my porch. Before I moved to New York, I stopped by to see the cats one last time.

About half of “Cat Person” is a sex scene. In it, Roupenian depicts a type of bad sex that is easy for readers to relate to: not explicitly harmful or abusive but toeing the line of consent and leaving Margot feeling repulsed afterward. This is where the story diverges completely from my reality. Aside from the fact that, like Margot, it was my first time not having to sneak around in suburban basements to hook up, the latter half of “Cat Person” does not mirror my relationship with Charles. In Roupenian’s story, Margot laughs when Robert asks if she’s had sex before. The first time Charles and I hooked up, he was surprised when I told him I never had. In “Cat Person,” Margot is turned off by Robert’s aggression and embarrassed by his vulnerability. Roupenian spends a good portion of the story describing just how disgusting of a person he is. Of course, I know nothing about how Charles was with other women; I can only speak for myself. With me, at least, he was careful, patient, and gentle—it was the first time someone asked if they could kiss me instead of just doing it.

But so much of the central dynamic in the story rang true to me: Charles’ cryptic communication style; the way I had to work to impress him; the joke rapport we created between our cats early on—him sending a picture of his roommate’s cat captioned “watching u sleep,” and me responding with a picture of my family’s cat with a bird in its mouth captioned “brought u breakfast.” Roupenian even knew the location of our first date: the multiplex outside of town, Quality 16. In “Cat Person,” the characters didn’t touch during their first date, either.

After I read the story, I sent Charles the link. At that point, we weren’t in regular communication, but we still texted occasionally. “It seems like we’ve been stalked,” I joked. He texted me as he was reading:

“this is weird!” “it is very disparaging to the guy, am I a slimeball”

I’d assured him that with me, he wasn’t. Eventually, he changed the subject. Later, I Googled Roupenian and discovered that she was getting her MFA in the University of Michigan’s English department; I was friendly with some grad students in her program and remember thinking that maybe one of them had found my relationship strange and mentioned it to her. Looking back, it’s hard to say why I never asked Charles whether he knew her. Maybe I didn’t really want to know. At that point, I was trying to avoid probing personal topics with him in order to distance myself. I was hoping not to encourage him to rely on me.

Three years later, I found out Charles had died via an Instagram DM from his mom that I opened at midnight on a Friday. It was November 2020—five years since we broke up, and five months since we last texted, when he’d been furloughed from his job due to COVID and I’d posted on Instagram that I was collecting money for Black Lives Matter–related orgs. “Something aggressive [fist emoji] not milquetoast neoliberal,” he labeled his Venmo to me. I texted him the receipt.

He passed away suddenly, his mom said. I spent that night lying awake and the next day in a trance. The following evening, I texted David—who had remained one of Charles’ closest friends—to ask if he’d heard from Charles’ family. When he said no, I called to break the news. (David is a pseudonym, too, at his request.) About an hour into a conversation full of attempts to articulate just how special Charles was, he brought up “Cat Person.” “He was always so upset that she brought you into it,” he said. I paused, taking in what this might mean. I’d spent the past three years trying to convince myself that it was just some crazy coincidence.

“Did Charles know her?” I asked. Yes, David told me. He did.

When I first got off the phone with David, I felt oddly giddy. In the midst of my grief, I realized for the first time that my suspicions had been true—I could finally say for sure that “Cat Person” was about me. As the night wore on, my chest tightened. Within hours, the strange thrill I’d felt was replaced by disgust, then anger. I imagined Roupenian scrolling through my social media accounts, gathering details about me. I felt invaded.

By the time I went to bed, I was brainstorming ways of getting in contact with Roupenian. I wanted to yell at her. But when I tried to imagine what I actually wanted to say, I wasn’t sure.

When asked in interviews what inspired “Cat Person,” Roupenian has said it came out of an experience she had in her mid-30s with a man she met online. But she’s also insisted, repeatedly , on its fictionality. “It’s not autobiographical; though many of the details and emotional notes come from life,” she told the New York Times. The story feels so intimate and naturalistic that it’s easy to see why Roupenian has wanted to draw a line here, especially given how quick many readers have been to assume that the plot is taken from her life.

“Cat Person,” and the cultural reception to it, feels connected to the broader literary debate over “autofiction”—writing that, in its raw and confessional style, seems to blur the boundaries between the real and the invented. Susan Choi’s 2019 bestseller Trust Exercise was partly a coming-of-age story about a performing arts high school and partly a pointed commentary on the idea of autofiction itself: specifically, on the question of “who owns a story,” as Katy Waldman put it a New Yorker essay . In a recent New York Times Book Review essay titled “Our Autofiction Fixation,” novelist Jessica Winter writes about the confidence with which strangers assume that her fiction describes her own life. “The expectation that fiction is autobiographical is understandable for the simple reason that so much of it is,” she writes. But she adds: “There is something backhanded about using authors’ personal statements as a Captcha tool for verifying the emotional resonance of their work.” Female authors tend to attract these assumptions from readers with special frequency. It’s clear that Roupenian knows this firsthand.

I’ve wondered a lot about the line between fiction and nonfiction, and what license is actually bestowed by the act of labeling something as fiction. I’ve asked myself why Roupenian might have chosen not to change even a few key details about me and Charles—my workplace, my hometown, his appearance, the location of our first date. At times I’ve convinced myself that she wanted us to know it was about us. But then I remind myself that when she wrote “Cat Person,” she was still in her MFA program. No one knew her name. Submitting a story to the New Yorker was a long shot, and a piece of literary short fiction had never gone viral in this way.

It wasn’t until six months after Charles’ death that I finally gained the courage to email Roupenian. I wasn’t sure whether she’d deny everything, or whether she’d be angry, or whether she’d answer me at all. From what I understood from David, she and Charles hadn’t kept in touch, so I assumed she didn’t know about his death. After my editor reached out first, letting her know about this essay, I wrote a brief message asking if she’d be willing to talk on the phone. She replied to say that she wanted to take some time to think and would reach out again soon. Then came a longer note.

“Dear Alexis,” she began. “I’ve spent the past several days struggling with the question of how to balance what is right for me with what I owe you.”

When I was living in Ann Arbor, I had an encounter with a man. I later learned, from social media, that this man previously had a much younger girlfriend. I also learned a handful of facts about her: that she worked in a movie theater, that she was from a town adjacent to Ann Arbor, and that she was an undergrad at the same school I attended as a grad student. Using those facts as a jumping-off point, I then wrote a story that was primarily a work of the imagination, but which also drew on my own personal experiences, both past and present. In retrospect, I was wrong not to go back and remove those biographical details, especially the name of the town. Not doing so was careless.

She went on to emphasize that she’d never had access to any information about my personal life beyond that. She clarified that she didn’t think it was fair to characterize the character of Margot as fully based on me. But she continued:

I can absolutely see why the inclusion of those details in the story would cause you significant pain and confusion, and I can’t tell you how sorry I am about that. I hope it goes without saying that was never my intention, and I will do what I can to rectify any harm it caused. I was not prepared for the amount of attention the story received, and I have not always known how to handle the consequences of it, both for myself and other people. … It has always been important for my own well-being to draw a bright line, in public, between my personal life and my fiction. This is a matter not only of privacy but of personal safety. When “Cat Person” came out, I was the target of an immense amount of anger on the part of male readers who felt that the character of Robert had been treated unfairly. I have always felt that my insistence that the story was entirely fiction, and that I was not accusing any real-life individual of behaving badly, was all that stood between me and an outpouring of not only rage but potentially violence.

It took me a few days to fully process what she’d written. I appreciated that she was sorry. I could understand how unprepared and overwhelmed she felt by just how much attention “Cat Person” received. But I was also frustrated. I could sense in her email that she hoped I might feel guilty about potentially encouraging the misdirected rage of her male readers. And I was angry, still—that someone who knows so intensely about what it’s like to watch your readers misconstrue fiction as autobiography would have dragged others, without their knowledge, into that discomfort.

More than anything, it shocked me to see that Roupenian also felt nervous. Reading her note, I realized for the first time that I wasn’t as helpless in all of this as I’d thought. I’d spent the past several months feeling, frankly, too scared—of her fame and her story’s dedicated fan base—to consider speaking publicly about my own experience. But it turned out she was struggling, too. (After she emailed, I reached out to her again to tell her that Charles had died, since I wanted to make sure she didn’t learn it from reading this essay; Roupenian asked to keep that phone conversation off the record.)

We are all unreliable narrators. Sometimes, to my own disappointment, I find myself inclined to trust Roupenian over myself. Had Charles actually been pathetic and exploitative, and I simply hadn’t understood it because I, like Margot, was young and naïve? Had he become vengeful and possessive after we broke up, but I’d just blocked it out in order to move on with my life? The story is so confident and sure, helping the reader to see things Margot herself does not. In December, David told me that Charles kept his old iPhone even after he got a new one so that he could look back at his old messages with Kristen from time to time to see whether he had actually been an asshole. Sometimes it feels easier to believe the story that everyone knows than the one they don’t.

I’m not sure how Roupenian gleaned so much information from social media alone, nor am I sure whether Charles told her anything about me, but she got a lot of things right. She captured the way Charles winced when made fun of, the way he couldn’t stand being laughed at. How sensitive he was. The way we both worried the other was ashamed of the relationship, and how we avoided places where I might run into classmates and ended up running into my TAs instead. She guessed correctly at the way I was intimidated by my colleagues at the Michigan Theater, afraid I wasn’t smart enough to express my opinions to them. She repeatedly mentioned the dining hall and dorms (things Charles and I pretended weren’t central to my life) in order to emphasize the age difference. Most importantly, she got that the power dynamic went both ways: Charles was my point of access to an entirely new world of culture and an escape from a life where I didn’t fit in, but with my youth—the way I had my whole life ahead of me—I held power over him, too.

My relationship with Charles was full of shame brought on by people who assumed the worst—a predatory man asserting his power over an innocent girl. But those who knew Charles well knew how respectful and caring he could be. On a Zoom memorial following his death, half a dozen people around the country said something to the effect of “I was in a dark place, then Charles said, ‘Hey, come live with me,’ and it turned things around.” Despite his social anxieties and insecurities, the Charles I knew made space for people. He was most in his element when showing someone new around town, or patiently teaching a group how to play a board game, having studied the rules in advance.

What’s difficult about having your relationship rewritten and memorialized in the most viral short story of all time is the sensation that millions of people now know that relationship as described by a stranger. Meanwhile, I’m alone with my memories of what really happened—just like any death leaves you burdened with the responsibility of holding onto the parts of a person that only you knew.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

What It Felt Like When “Cat Person” Went Viral

In the fall of 2017, I was finishing up lunch at a Noodles & Company in Ann Arbor, Michigan, when I saw that I’d missed a call from a 212 area code. I thought, I bet my story just got into The New Yorker . This was an unusual assumption for me to make, given that, at that point, I’d had a single story accepted in a print literary magazine; the rest of my published work was available only in online genre venues, like Body Parts Magazine and Weird Fiction Review. The story I’d submitted to The New Yorker had already been rejected, politely, by every other publication I’d sent it to, but, a few weeks earlier, my agent had received an e-mail from Deborah Treisman , The New Yorker’s fiction editor, which read, in its entirety:

Hi Jenni, I just want to apologize for holding onto this one for so long. It’s an intriguing piece and I have it circulating here now, so should be able to get back to you in the next week or two. Sorry to keep you waiting, Deborah

If you are not in the habit of submitting short stories to literary magazines, this might not seem like such a big deal to you, but, when I learned that the fiction editor of The New Yorker knew my name, I was so thrilled that I forwarded the e-mail to my mother.

Against all odds, my prediction was correct. On my voice mail was a message from my agent—at that point, we’d had so few reasons to talk to each other that I hadn’t yet entered her number into my phone. All I remember from the rest of that afternoon was sitting under an oak tree in a University of Michigan quad, trying to wrap my brain around what had happened and what it would mean and thinking, This is it. This is the happiest I will ever be.

On Monday, December 4th, my story “ Cat Person ” came out in the magazine and online. I posted the link on my Facebook page, at which point nearly everyone I’d ever met either liked it or sent me a message saying “ CONGRATULATIONS ,” and I responded “ THANK YOU !!!” Then a bunch of my friends took me out for drinks at a local cocktail bar and, after that, it was pretty much over.

Except that it wasn’t. Three days later, I was sitting in a coffee shop with my girlfriend, Callie, trying to write, when she looked up from her computer and said, “There’s something going on with your story.” Callie is also a writer, and she used to work in publishing, so she was much more connected to the literary Internet than I was. She seemed slightly unnerved. “It’s just Twitter,” I said, with the smug dismissiveness of a thirtysomething late millennial who had tweeted a grand total of twelve times in her life. Callie tried to explain what was happening; I failed to understand. Then I went home, fired up Twitter, and saw that I had a bunch of notifications from strangers. I was reading through them when my mom called about something unrelated. I tried to explain to her what was happening, and then she went online herself and, at some point, she said, “Oh, my God, Kristen, someone Barack Obama follows just retweeted your story.” Then she burst into tears.

In brief, “Cat Person” is a story about two characters—Margot, a twenty-year-old college student, and Robert, a man in his mid-thirties—who go on a single bad date. The story is told in the close third person, and much of it is spent describing Margot’s thought process as she realizes that she does not want to have sex with Robert but then decides, for a variety of reasons, to go through with it anyway. When the story appeared online, young women began sharing it among themselves; they said it captured something that they had also experienced: the sense that there is a point at which it is “too late” to say no to a sexual encounter. They also talked, more broadly, about the phenomenon of unwanted sex that came about not through the use of physical force but because of a poisoned cocktail of emotions and cultural expectations—embarrassment, pride, self-consciousness, and fear. What had started as a conversation among women was then taken up and folded into a much larger debate that played out, for the most part, between men and women, its flames fanned by the Internet controversy machine. Was what happened between Robert and Margot an issue of consent, or no? Was Robert a villain for not picking up on Margot’s discomfort, or was Margot at fault for not telling Robert what she was feeling? The lines hardened, think pieces proliferated, and disagreements were amplified to the point of absurdity, until the story threatened to become the blue-dress/white-dress moment of the #MeToo era. Men read “Cat Person” this way! Women read “Cat Person” that way! Why can’t we all just get along?

I may have oversimplified this version of events. There are a lot of essays and articles out there that summarize the response to the story much more objectively than I ever could. When I started writing this, my goal was to do something different, to tell the story from the epicenter, to answer a question that I still get asked fairly often: “What was it like to have your story go viral?” But that is turning out to be surprisingly hard.

The truth is that my memory of that period is largely fragmentary, displaced in time and space. I remember that that weekend was very, very cold; my dog had a U.T.I., so I had to keep going outdoors even as the rain froze into snow. I remember logging out of Twitter and then sneaking back onto it from my phone. I remember my friends, on a group chat, sending me a screenshot of someone on Twitter saying, “I cannot IMAGINE her group texts rn”—the social-media snake eating its own tail. I remember Callie hugging me as I cried. I remember the e-mails coming and coming—first, fan letters from people who’d discovered my story and liked it, then anti-fan letters, from people who’d discovered my story and didn’t. I received many in-depth descriptions, from men, of sexual encounters they’d had, because they thought I’d “just like to know.” I got e-mails from people I hadn’t talked to in years who wondered if I’d noticed that my story had gone viral. And, as the days went on, I got e-mails requesting interviews from outlets all over the globe: the U.S., Canada, England, Australia. Everyone wanted me to come on the air and talk about my story. Emphasis on my .

Because that was another thing about the story’s second life as an Internet Sensation: its status as fiction had largely got lost. In a way, I still feel that this is something to be proud of: the story’s realism, and Margot’s perspective in particular, were things I had worked very hard to perfect. I’d wanted people to be able to see themselves in the story, to identify with it in such a way that its narrative scaffolding would disappear. But, perhaps inevitably, as the story was shared again and again, moving it further and further from its original context, people began conflating me, the author, with the main character. Sometimes this was blunt (“What, The New Yorker is just publishing diary entries now?”) and other times it was subtler: the assumption was that I’d be happy to go on the radio and explain why young women in 2018 were still struggling to achieve satisfying sex lives—in other words, the assumption was that my own position and history would be identical to Margot’s. I was thirty-six years old and a few months into my first serious relationship with a woman, and now everyone wanted me to explain why twenty-year-old girls were having bad sex with men. I felt intensely protective of Margot, and of the readers who identified with her, and, at the same time, I felt like an impostor. I felt as though if I were truthful about who I was, I would let everyone down.

So what was it like to have a story go viral? For a few hours, before I came to my senses and shut down my computer, I got to live the dream and the nightmare of knowing exactly what people thought when they read what I’d written, as well as what they thought about me. A torrent of unvarnished, unpolished opinion was delivered directly to my eyes and my brain. That thousands—and, eventually, millions—of readers had liked the story, identified with it, been affected by it, exhorted others to read it, didn’t make this any easier to take. The story was not autobiographical, but it was, nonetheless, personal—everything I write is personal—and here were all these strangers dissecting it, dismissing it, judging it, fighting about it, joking about it, and moving on.

I want people to read my stories—of course I do. That’s why I write them. But knowing, in that immediate and unmediated way, what people thought about my writing felt . . . the word I keep reaching for, even though it seems melodramatic, is annihilating . To be faced with all those people thinking and talking about me was like standing alone, at the center of a stadium, while thousands of people screamed at me at the top of their lungs. Not for me, at me. I guess some people might find this exhilarating. I did not.

For people with low-level social anxiety, a common piece of conventional wisdom is that you should stop worrying so much about what other people think, because no one is actually thinking about you. In fact, this isn’t true, even if you haven’t had a story go viral. Almost everyone we encounter thinks about us. Bad hair, they think, as they pass us on the street. Annoying voice. Nice legs. Gummy smile. Stained shirt. She looks like my third-grade teacher. Why is she taking so long to order her coffee? I hate her stupid face. The problem is not that other people think about us but that their thoughts are so flattening, so reductive in comparison to our own complicated view of ourselves. Here I am, having this irreducible and mysterious set of human experiences, and all you think when you encounter me is, Her hair is weird. Many horror stories revolve around this theme: if we could eavesdrop on all the quick, dismissive thoughts that other people were having about us, we would go insane. We are simply not meant to see ourselves as others see us.

Here’s the catch: when you read a story I’ve written, you’re not thinking about me—you’re thinking as me. I’ve wormed my way inside your head (hi!) and briefly taken over your mind. You’re forced to reckon with my full complexity—or, at least, whatever fraction of that complexity I’ve managed to get down on the page. When the story is over—or if you put it down midway—you’re free to think whatever you want. You can think, Dumb, or Boring, or Great, or, She looks like a bitch in her author photo, or, What the fuck did I just read? But I don’t need to be there to absorb your reaction. In fact, I shouldn’t be. My role in the process is over. The interpretation, the criticism, the analysis telling you that you’re right or that you’re wrong or that you’re an asshole—that’s someone else’s job. I can’t, and won’t, take part.

After “Cat Person” went viral, I sold my first book , a story collection. It’s coming out this month. I’m hoping that the number of monsters and murderers in its pages will put at least some of the autobiographical questions to rest. But, more than that, I want people to read it. I hope they like it. And, at the same time, I don’t want to know what they think about it. I’m sure that sometime, late at night, I’ll go on Twitter and search for my name and try to figure out what people are saying—or not saying—about me and my book. I’ll do this because I’m human, and I’m curious, and I’m anxious, and because it’s possible to want things that are bad for us—but I’ll also do my best to resist. Another piece of conventional wisdom is that what other people think about us is none of our business. And, as it turns out, with that I agree.

Home For Fiction – Blog

for thinking people

July 12, 2020

Kristen Roupenian’s “Cat Person”: an Example of Post-Autonomous Fiction

Criticism , Writing

guest post , Igor Livramento , Kristen Roupenian , literature , narrative , post-autonomous , writing

Today’s post offers an example of post-autonomous fiction, focusing on Kristen Roupenian’s “Cat Person”. The article is authored by Igor da Silva Livramento. He’s a fellow academic from UFSC, fellow author, fellow creative-writing advisor, and overall a great fellow. He’s also a composer, music theorist, and producer. Check out his papers on Academia.edu , his music on Bandcamp , and his personal musings on his blog – in Portuguese, Spanish/Castilian, and English.

Having explained what on earth is post-autonomous fiction , this time we’ll see an example of it, focusing on some of its literary specifics. Our example will be a most fascinating story. It appeared on The New Yorker , on December 4th, 2017.

I’m referring to Kristen Roupenian’s “Cat Person” .

What’s so interesting is that the story got more views on a single week than any other one published on the magazine that year. That alone is impressive, but the reaction it got is also worthy of mention.

This reaction was due to a narration technique we’ll explore, and such a technique as applied there increased its post-autonomous status.

Roupenian’s “Cat Person”: The Basics

“Cat Person” is a short story about the unsuccessful relationship between the young Margot, 20 years of age, and Robert, 14 years older. It focuses on describing Margot’s thoughts about her desires and expectations about the relationship (built through instant messaging with Robert).

I won’t go into details regarding the content of the story . That would lead downwards a spiral of sociopolitical and affective issues that are burning the best minds of our time. By my standard, it is not even a great short story – one worthy of literary praise.

But that’s exactly the whole idea of its being an example of post-autonomous fiction.

Post-Autonomy at Work

What’s important is not whether the story is good in a literary sense. That would be an autonomous judgement. Rather, its importance lies in that, as a story, it’s indistinguishable from reality.

Most readers thought Roupenian was writing about herself; an autobiographical account, some awful time she had in her life.

Now, that was a truly post-autonomous reception of the story. It was so indistinguishable from reality that readers thought it was about the author herself. So much, that she had to come out and speak against that interpretation.

Though we should remember from my last post : “The author” is not an analytical category worth thinking through in such cases, precisely because it adds nothing to the understanding and interpretation of the story.

This points us in a curious direction: Margot embodies a wealth of women, she is many. In other words, a twitter hashtag like #We’reAllMargot is perfectly feasible.

However, the question remains: Why did people think Margot was Roupenian? To understand it we’ll have to get our hands dirty in the theoretical jargon.

Roupenian’s “Cat Person”: Theory and/in Practice

The story is narrated in third person, but the narrator is far from an omniscient disinterested eagle hovering above the clouds. It is more akin to the game Resident Evil 4 ‘s close-up on the back of the protagonist: All we ever get to know is filtered by Margot’s perceptions, feelings, sensations, and intuitions.

Let us label it a false third person or, more precisely, a disguised first-person narrator . Let’s check the opening paragraph:

Margot met Robert on a Wednesday night toward the end of her fall semester. She was working behind the concession stand at the artsy movie theatre downtown when he came in and bought a large popcorn and a box of Red Vines.

Analysis to the Rescue!

From the outset, time is framed from Margot’s perspective: It happened “toward the end of her fall semester”. We get to know where she was working.

Movement is also perceived through her lens: “[…] when he came in “. Robert’s shopping is presented to us through her objective, outside-looking-in impersonal listing: “a large popcorn and a box of Red Vines” (if it was not for his name, we would almost hear his voice as merely another costumer order). And last but not least: her name comes first in the first sentence of the first paragraph: She is the grand opener – a most meaningful decision.

From such marks on the path of reading we get used to Margot’s perspective as the narrator’s perspective.

Another quote three paragraphs ahead and we’ll notice how narration tricks us further into it:

Robert did not pick up on her flirtation. Or, if he did, he showed it only by stepping back, as though to make her lean toward him, try a little harder.

The very first sentence tries to fool us with objectivity: “Robert did not pick up […]”. As soon as we get to the next sentence, we’re back at Margot’s shoes: “O r, if he did, ” – here lies her impression of his action – “he showed it only by stepping back ” – and now we’re trapped in her limited access to his outer side, her observation of his external behavior.

The fact two such sentences form a single paragraph reinforces that narration chooses Margot’s perspective as the single one true (third-person) position from whence to tell the story. A trick well played , most readers bit the bait.

Hands-on Advice

Getting practical, let’s think of a method to enable us to write in such manner.

A great way to write in disguised first-person narration is to actually write first in full-blown first person. Then, when the text is finished, change every part of speech (verbs, pronouns, etc.) to third person, as necessary.

Devising a text under such methodology will ensure we do not slip any inadequate perspectives that would break the verisimilitude Verisimilitude stems from the Latin verisimilar , meaning truth-like(ness) ("similar" is a common English word; vera appears in "veracity"). It may be translated as "feasibleness". A technical term within poetics first appearing on Aristotle’s Ars Poetica as a criterion of fiction. It remains meaningful to this day: If a fictional world is coherent , it is verisimilar . This has nothing to do with truth in philosophy or science. Or does it? Food for thought. of our fictional creation.

Note that the “objective” sentence about Robert we analyzed further above is but a strategy to trick us into buying the equation “Margot’s perspective = Narrator (third person) = Objective perception”.

In Guise of Conclusion

As we saw, a well-devised close-up (“zoomed in”) third-person narrator can be a wolf in sheep’s clothing. It becomes a disguise for a first-person narrative.

If it ain’t the best of both worlds!

The illusion of objectivity provided by third person goes hand in hand with the affective intensity of first-person impressions and reactions. And, oh if it works!

It does work so well that not only did it give Roupenian a million-dollar contract for two books, it also was the most accessed story that whole year on the magazine. This is a notable feat, considering how late in the year – December 4th – it was published.

And all that happened because of the post-autonomous reception (“Did this happen to her? Is this autobiographical?”) of the short story.

27 pages • 54 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Story Analysis

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

How does Roupenian explore shame in the story? Who feels shame, under what conditions, and to what ends? Use examples from the text to support your argument.

Why does Margot imagine a future boyfriend to tell this story to? What themes does this fantasy play into?

Discuss the role of movies in the story. When do movies show up, who references them, and what purpose do they serve?

Featured Collections

Books that Feature the Theme of...

View Collection

Feminist Reads

'Cat Person' and the Impulse to Undermine Women's Fiction

Kristen Roupenian’s viral New Yorker short story is not an essay—but many have seen it as one.

In fiction-writing—before characters can be developed, before plots can be sketched, before tensions can be introduced, and attendant arcs molded and stretched—the author must first make a series of much more basic decisions: How will the story be told? Who, in the context of the story itself, will tell it? Who will be given a person and a voice within this hermetic little universe? Who will not? Why? Why not? These are the defining cosmological questions of every work of fiction, the ones that will shape everything else that comes to exist in the author’s—and the story’s—manufactured world.