Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Understanding the Influence of Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Class on Inequalities in Academic and Non-Academic Outcomes among Eighth-Grade Students: Findings from an Intersectionality Approach

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity, Department of Social Statistics, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Affiliation Australian National University, Acton, Australia

- Laia Bécares,

- Naomi Priest

- Published: October 27, 2015

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141363

- Reader Comments

Socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and gender inequalities in academic achievement have been widely reported in the US, but how these three axes of inequality intersect to determine academic and non-academic outcomes among school-aged children is not well understood. Using data from the US Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten (ECLS-K; N = 10,115), we apply an intersectionality approach to examine inequalities across eighth-grade outcomes at the intersection of six racial/ethnic and gender groups (Latino girls and boys, Black girls and boys, and White girls and boys) and four classes of socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage. Results of mixture models show large inequalities in socioemotional outcomes (internalizing behavior, locus of control, and self-concept) across classes of advantage/disadvantage. Within classes of advantage/disadvantage, racial/ethnic and gender inequalities are predominantly found in the most advantaged class, where Black boys and girls, and Latina girls, underperform White boys in academic assessments, but not in socioemotional outcomes. In these latter outcomes, Black boys and girls perform better than White boys. Latino boys show small differences as compared to White boys, mainly in science assessments. The contrasting outcomes between racial/ethnic and gender minorities in self-assessment and socioemotional outcomes, as compared to standardized assessments, highlight the detrimental effect that intersecting racial/ethnic and gender discrimination have in patterning academic outcomes that predict success in adult life. Interventions to eliminate achievement gaps cannot fully succeed as long as social stratification caused by gender and racial discrimination is not addressed.

Citation: Bécares L, Priest N (2015) Understanding the Influence of Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Class on Inequalities in Academic and Non-Academic Outcomes among Eighth-Grade Students: Findings from an Intersectionality Approach. PLoS ONE 10(10): e0141363. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141363

Editor: Emmanuel Manalo, Kyoto University, JAPAN

Received: June 10, 2015; Accepted: October 6, 2015; Published: October 27, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Bécares, Priest. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Data Availability: All ECLS-K Kindergarten-Eighth Grade Public-use File are available from the National Center for Education Statistics website ( https://nces.ed.gov/ecls/dataproducts.asp#K-8 ).

Funding: This work was funded by an ESRC grant (ES/K001582/1) and a Hallsworth Research Fellowship to LB.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

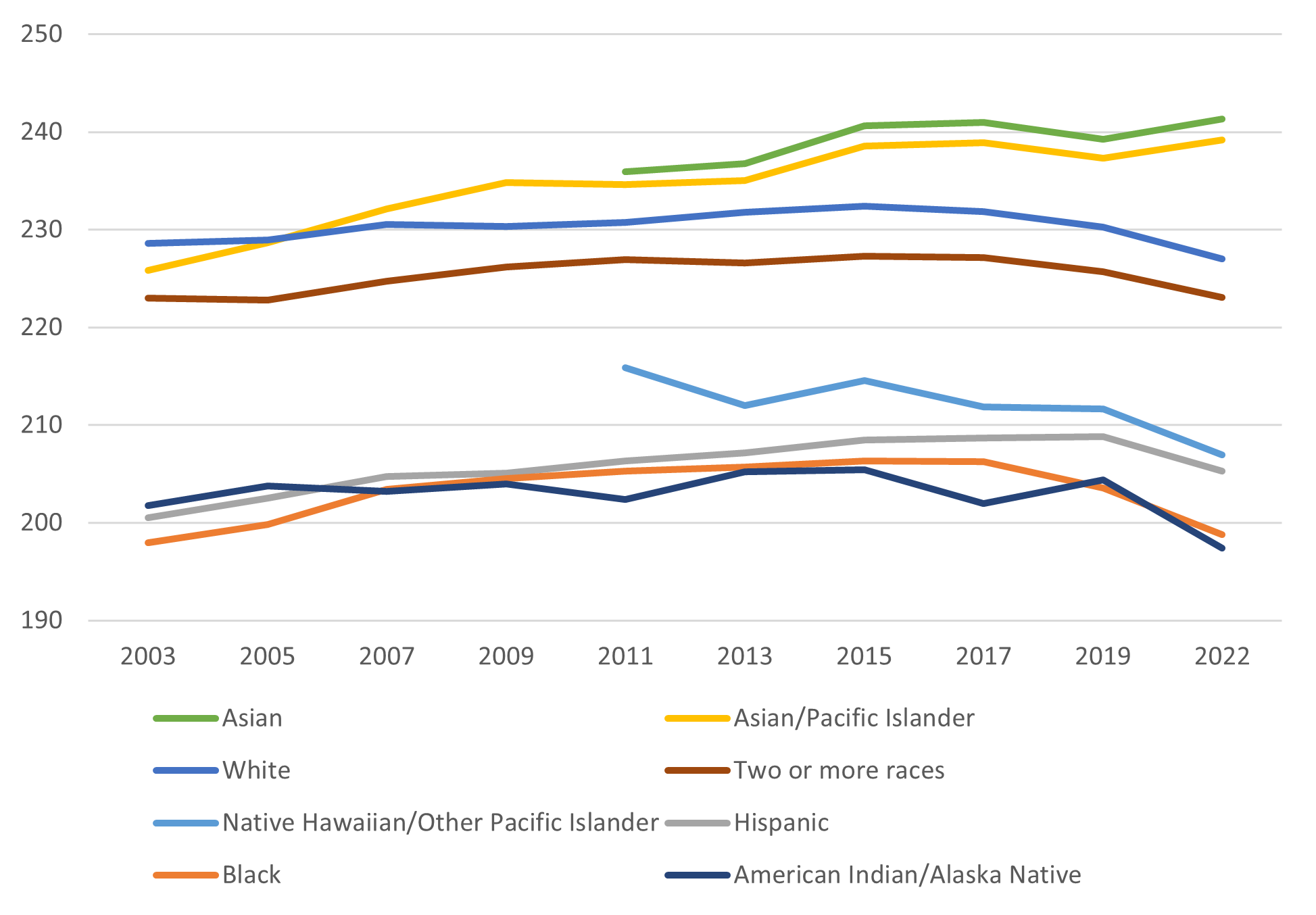

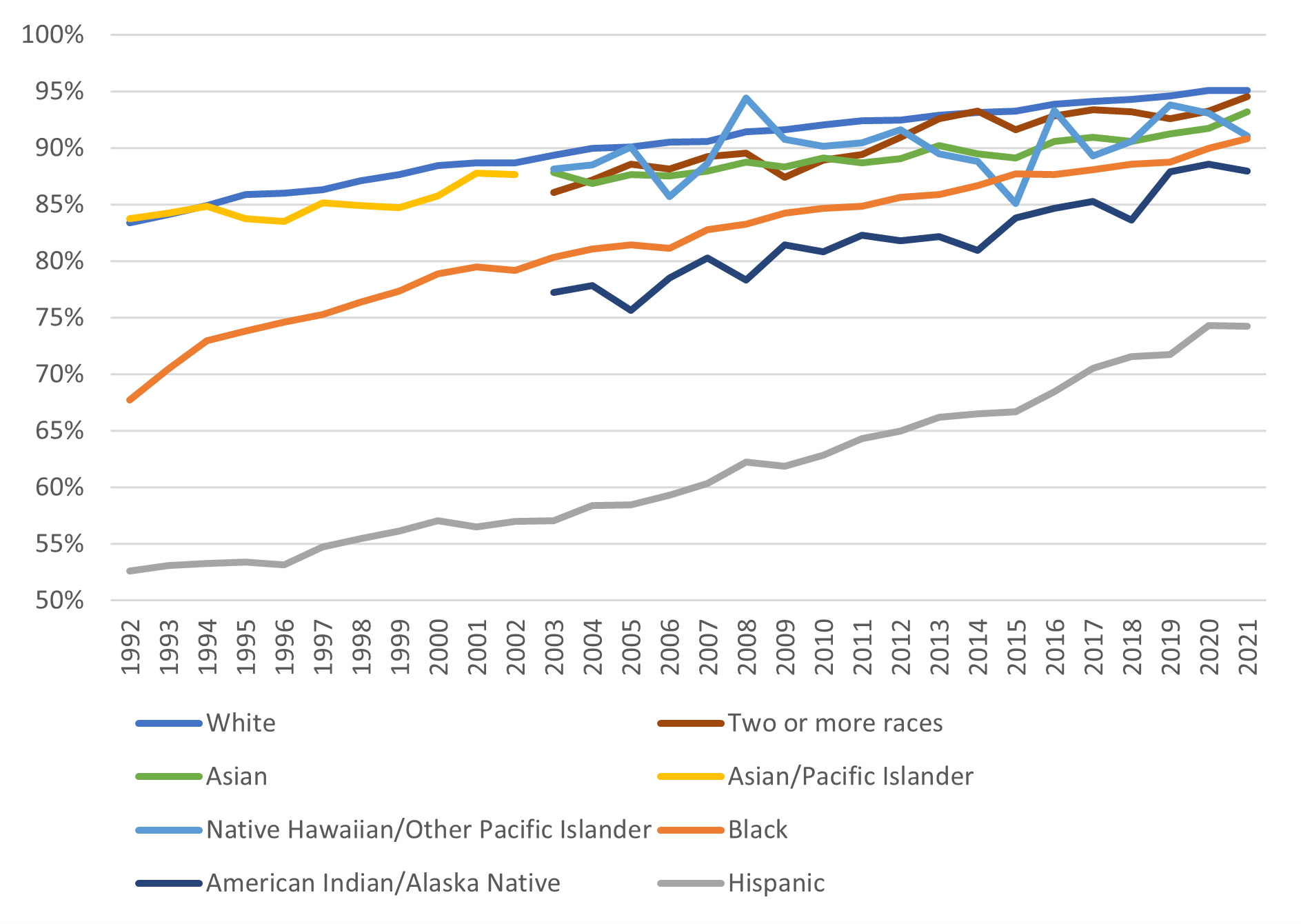

The US racial/ethnic academic achievement gap is a well-documented social inequality [ 1 ]. National assessments for science, mathematics, and reading show that White students score higher on average than all other racial/ethnic groups, particularly when compared to Black and Hispanic students [ 2 , 3 ]. Explanations for these gaps tend to focus on the influence of socioeconomic resources, neighborhood and school characteristics, and family composition in patterning socioeconomic inequalities, and on the racialized nature of socioeconomic inequalities as key drivers of racial/ethnic academic achievement gaps [ 4 – 10 ]. Substantial evidence documents that indicators of socioeconomic status, such as free or reduced-price school lunch, are highly predictive of academic outcomes [ 2 , 3 ]. However, the relative contribution of family, neighborhood and school level socioeconomic inequalities to racial/ethnic academic inequalities continues to be debated, with evidence suggesting none of these factors fully explain racial/ethnic academic achievement gaps, particularly as students move through elementary school [ 11 ]. Attitudinal outcomes have been proposed by some as one explanatory factor for racial/ethnic inequalities in academic achievement [ 12 ], but differences in educational attitudes and aspirations across groups do not fully reflect inequalities in academic assessment. For example, while students of poorer socioeconomic status have lower educational aspirations than more advantaged students [ 13 ], racial/ethnic minority students report higher educational aspirations than White students, particularly after accounting for socioeconomic characteristics [ 14 – 16 ]. Similarly, while socio-emotional development is considered highly predictive of academic achievement in school students, some racial/ethnic minority children report better socio-emotional outcomes than their White peers on some indicators, although findings are inconsistent [ 17 – 22 ].

In addition to inequalities in academic achievement, racial/ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities also exist across measures of socio-emotional development [ 23 – 26 ]. And as with academic achievement, although socioeconomic factors are highly predictive of socio-emotional outcomes, they do not completely explain racial/ethnic inequalities in school-related outcomes not focused on standardized assessments [ 11 ].

Further complexity in understanding how academic and non-academic outcomes are patterned by socioeconomic factors, and how this contributes to racial/ethnic inequalities, is added by the multi-dimensional nature of socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status is widely recognized as comprising diverse factors that operate across different levels (e.g. individual, household, neighborhood), and influence outcomes through different causal pathways [ 27 ]. The lack of interchangeability between measures of socioeconomic status within and between levels (e.g. income, education, occupation, wealth, neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics, or past socioeconomic circumstances) is also well established, as is the non-equivalence of measures between racial/ethnic groups [ 27 ]. For example, large inequalities have been reported across racial/ethnic groups within the same educational level, and inequalities in wealth have been shown across racial/ethnic that have similar income. It is therefore imperative that studies consider these multiple dimensions of socioeconomic status so that critical social gradients across the entire socioeconomic spectrum are not missed [ 27 ], and racial/ethnic inequalities within levels of socioeconomic status are adequately documented. It is also important that differences in school outcomes are considered across levels of socioeconomic status within and between racial/ethnic groups, so that the influence of specific socioeconomic factors on outcomes within specific racial/ethnic groups can be studied [ 28 ]. However, while these analytic approaches have been identified as research priorities in order to enhance our understanding of the complex ways in which socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity intersect to influence school outcomes, research that operationalizes these recommendations across academic and non-academic outcomes of school children is scant.

In addition to the complexity that arises from race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and intersections between them, different patterns in academic and non-academic outcomes by gender have also received longstanding attention. Comparisons across gender show that, on average, boys have higher scores in mathematics and science, whereas girls have higher scores in reading [ 2 , 3 , 29 ]. In contrast to explanations for socioeconomic inequalities, gender differences have been mainly attributed to social conditioning and stereotyping within families, schools, communities, and the wider society [ 30 – 35 ]. These socialization and stereotyping processes are also highly relevant determining factors in explaining racial/ethnic academic and non-academic inequalities [ 35 , 36 ], as are processes of racial discrimination and stigmatization [ 37 , 38 ]. Gender differences in academic outcomes have been documented as differently patterned across racial/ethnic groups and across levels of socioeconomic status. For example, gender inequalities in math and science are largest among White and Latino students, and smallest among Asian American and African American students [ 39 – 43 ], while gender gaps in test scores are more pronounced among socioeconomically disadvantaged children [ 44 , 45 ]. In terms of attitudes towards math and sciences, gender differences in attitudes towards math are largest among Latino students, but gender differences in attitudes towards science are largest among White students [ 39 , 40 ]. Gender differences in socio-developmental outcomes and in non-cognitive academic outcomes, across race/ethnicity and socio-economic status, have received far less attention; studies that consider multiple academic and non-academic outcomes among school aged children across race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status and gender are limited in the US and internationally.

Understanding how different academic and non-academic outcomes are differently patterned by race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and gender, including within and between group differences, is an important research area that may assist in understanding the potential causal pathways and explanations for observed inequalities, and in identifying key population groups and points at which interventions should be targeted to address inequalities in particular outcomes [ 28 , 46 ]. Not only is such knowledge critical for population level policy and/or local level action within affected communities, but failing to detect potential factors for interventions and potential solutions is argued as reinforcing perceptions of the unmodifiable nature of inequality and injustice [ 46 ].

Notwithstanding the importance of documenting patterns of inequality in relation to a particular social identity (e.g. race/ethnicity, gender, class), there is increasing acknowledgement within both theoretical and empirical research of the need to move beyond analyzing single categories to consider simultaneous interactions between different aspects of social identity, and the impact of systems and processes of oppression and domination (e.g., racism, classism, sexism) that operate at the micro and macro level [ 47 , 48 ]. Such intersectional approaches challenge practices that isolate and prioritize a single social position, and emphasize the potential of varied inter-relationships of social identities and interacting social processes in the production of inequities [ 49 – 51 ]. To date, exploration of how social identities interact in an intersectional way to influence outcomes has largely been theoretical and qualitative in nature. Explanations offered for interactions between privileged and marginalized identities, and associated outcomes, include family and teacher socialization of gender performance (e.g. math and science as male domains, verbal and emotional skills as female), as well as racialized stereotypes and expectations from teachers and wider society regarding racial/ethnic minorities that are also gendered (e.g. Black males as violent prone and aggressive, Asian females as submissive) [ 52 – 57 ]. That is, social processes that socialize and pattern opportunities and outcomes are both racialized and gendered, with racism and sexism operating in intersecting ways to influence the development and achievements of children and youth [ 58 – 60 ]. Socioeconomic status adds a third important dimension to these processes, with individuals of the same race/ethnicity and gender having access to vastly different resources and opportunities across levels of socioeconomic status. Moreover, access to resources as well as socialization experiences and expectations differ considerably by race and gender within the same level of socio-economic status. Thus, neither gender nor race nor socio-economic status alone can fully explain the interacting social processes influencing outcomes for youth [ 27 , 28 ]. Disentangling such interactions is therefore an important research priority in order to inform intervention to address inequalities at a population level and within local communities.

In the realm of quantitative approaches to the study of inequality, studies often examine separate social identities independently to assess which of these axes of stratification is most prominent, and for the most part do not consider claims that the varied dimensions of social stratification are often juxtaposed [ 56 , 61 ]. A pressing need remains for quantitative research to consider how multiple forms of social stratification are interrelated, and how they combine interactively, not just additively, to influence outcomes [ 46 ]. Doing so enables analyses that consider in greater detail the representation of the embodied positions of individuals, particularly issues of multiple marginalization as well as the co-occurrence of some form of privilege with marginalization [ 46 ]. It is important to note that the languages of statistical interaction and of intersectionality need to be carefully distinguished (e.g. intersectional additivity or additive assumptions, versus additive scale and cross-product interaction terms) to avoid misinterpretation of findings, and to ensure appropriate application of statistical interaction to enable the description of outcome measures for groups of individuals at each cross-stratified intersection [ 46 ]. Ultimately this will provide more nuanced and realistic understandings of the determinants of inequality in order to inform intervention strategies.

This study fills these gaps in the literature by examining inequalities across several eighth grade academic and non-academic outcomes at the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. It aims to do this by: identifying classes of socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage from kindergarten to eighth grade; then ascertaining whether membership into classes of socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage differ for racial/ethnic and gender groups; and finally, by contrasting academic and non-academic outcomes at the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender and socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage. Intersecting identities of race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic characteristics are compared to the reference group of White boys in the most advantaged socioeconomic category, as these are the three identities (male, White, socioeconomically privileged) that experience the least marginalization when compared to racial/ethnic and gender minority groups in disadvantaged socioeconomic positions.

This study used data on singleton children from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten (ECLS-K). The ECLS-K employed a multistage probability sample design to select a nationally representative sample of children attending kindergarten in 1998–99. In the base year the primary sampling units (PSUs) were geographic areas consisting of counties or groups of counties. The second-stage units were schools within sampled PSUs. The third- and final-stage units were children within schools [ 62 ]. Analyses were conducted on data collected from direct child assessments, as well as information provided by parents and school administrators.

Ethics Statement

This article is based on the secondary analysis of anonymized and de-identified Public-Use Data Files available to researchers via the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). Human participants were not directly involved in the research reported in this article; therefore, no institutional review board approval was sought.

Outcome Variables.

Eight outcome variables, all assessed in eighth grade, were selected to examine the study aims: two measures relating to non-cognitive academic skills (perceived interest/competence in reading, and in math); three measures capturing socioemotional development (internalizing behavior, locus of control, self-concept); and three measures of cognitive skills (math, reading and science assessment scores).

For the eighth-grade data collection, children completed the 16-item Self Description Questionnaire (SDQ) II [ 63 ], where they provided self-assessments of their academic skills by rating their perceived competence and interest in English and mathematics. The SDQ also asked children to report on problem behaviors with which they might struggle. Three subscales were produced from the SDQ items: The SDQ Perceived Interest/Competence in Reading, including four items on grades in English and the child’s interest in and enjoyment of reading. The SDQ Perceived Interest/Competence in Math, including four items on mathematics grades and the child’s interest in and enjoyment of mathematics. And the SDQ Internalizing Behavior subscale, which includes eight items on internalizing problem behaviors such as feeling sad, lonely, ashamed of mistakes, frustrated, and worrying about school and friendships [ 62 ].

The Self-Concept and Locus of Control scales ask children about their self-perceptions and the amount of control they have over their own lives. These scales, adopted from the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988, asked children to indicate the degree to which they agreed with 13 statements (seven items in the Self-Concept scale, and six items in the Locus of Control Scale) about themselves, including “I feel good about myself,” “I don’t have enough control over the direction my life is taking,” and “At times I think I am no good at all.” Responses ranged from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Some items were reversed coded so that higher scores indicate more positive self-concept and a greater perception of control over one’s own life. The seven items in the Self-Concept scale, and the six items in the Locus of Control were standardized separately to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1. The scores of each scale are an average of the standardized scores [ 62 ].

Academic achievement in reading, mathematics and science was measured with the eighth-grade direct cognitive assessment battery [ 62 ].

Children were given separate routing assessment forms to determine the level (high/low) of their reading, mathematics, and science assessments. The two-stage cognitive assessment approach was used to maximize the accuracy of measurement and reduce administration time by using the child’s responses from a brief first-stage routing form to select the appropriate second-stage level form. First, children read items in a booklet and recorded their responses on an answer form. These answer forms were then scored by the test administrator. Based on the score of the respective routing forms, the test administrator then assigned a high or low second-stage level form of the reading and mathematics assessments. For the second-stage level tests, children read items in the assessment booklet and recorded their responses in the same assessment booklet. The routing tests and the second-stage tests were timed for 80 minutes [ 62 ]. The present analyses use the standardized scores (T-scores), allowing relative comparisons of children against their peers.

Individual and Contextual Disadvantage Variables.

Latent Class Analysis, described in greater detail below, was used to classify students into classes of individual and contextual advantage or disadvantage. Nine constructs, measuring characteristics at the individual-, school-, and neighborhood-level, were captured using 42 dichotomous variables measured across the different waves of the ECLS-K.

Individual-level variables captured household composition, material disadvantage, and parental expectations of the children’s success. Measures included whether the child lived in a single-parent household at kindergarten, first, third, fifth and eighth grades; whether the household was below the poverty threshold level at kindergarten, fifth and eighth grades; food insecurity at kindergarten, first, second and third grades; and parental expectations of the child’s academic achievement (categorized as up to high school and more than high school) at kindergarten, first, third, fifth and eighth grades. An indicator of whether parents had moved since the previous interview (measured at kindergarten, first, third, fifth and eighth grades) was included to capture stability in the children’s life. A household-level composite index of socioeconomic status, derived by the National Center for Education Statistics, was also included at kindergarten, first, third, fifth and eighth grades. This measure captured the father/male guardian’s education and occupation, the mother/female guardian’s education and occupation, and the household income. Higher scores reflect higher levels of educational attainment, occupational prestige, and income. In the present analyses, the socioeconomic composite index was categorized into quintiles and further divided into the lowest first and second quintiles, versus the third, fourth and fifth quintiles.

Two variables measured the school-level environment: percentage of students eligible for free school meals, and percentage of students from a racial/ethnic background other than White non-Hispanic. These two variables were dichotomized as more than or equal to 50% of students belonging to each category. Both variables were measured in the kindergarten, first, third, fifth and eighth grade data collections.

To capture the neighborhood environment, a variable was included which measured the level of safety of the neighborhood in kindergarten, first, third, fifth and eighth grades. Parents were asked “How safe is it for children to play outside during the day in your neighborhood?” with responses ranging from 1, not at all safe, to 3, very safe. For the present analyses, response categories were recoded into 1 “not at all and somewhat safe,” and 0 “very safe.”

Predictor Variables.

The race/ethnicity and gender of the children were assessed during the parent interview. In order to empirically measure the intersection between race/ethnicity and gender in the classes of disadvantage, a set of six dummy variables were created that combined racial/ethnic and gender categories into White boys, White girls, Black boys, Black girls, Latino boys, and Latina girls.

Statistical Analyses

This study used the manual 3-step approach in mixture modeling with auxiliary variables [ 64 , 65 ] to independently evaluate the relationship between the predictor auxiliary variables (the combined race/ethnicity and gender groups), the latent class variable of advantage/disadvantage, and the outcome (non-cognitive skills, socioemotional development, cognitive assessments). This is a data-driven, mixture modelling technique which uses indicator variables (in this case the variables described under Individual and Contextual Disadvantage Variables section) to identify a number of latent classes. It also includes auxiliary information in the form of covariates (the race/ethnicity and gender combinations described under Predictor Variables) and distal outcomes (the eight outcome variables), to better explore the relationships between the characteristics that make up the latent classes, the predictors of class membership, and the associated consequences of membership into each class.

The first step in the 3-step procedure is to estimate the measurement part of the joint model (i.e., the latent class model) by creating the latent classes without adding covariates. Latent class analyses first evaluated the fit of a 2-class model, and systematically increased the number of classes in subsequent models until the addition of latent classes did not further improve model fit. For each model, replication of the best log-likelihood was verified to avoid local maxima. To determine the optimal number of classes, models were compared across several model fit criteria. First, the sample-size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [ 66 ] was evaluated; lower relative BIC values indicate improved model fit. Given that the BIC criterion tends to favor models with fewer latent classes [ 67 ], the Lo, Mendell, and Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT) statistic [ 68 ] was also considered. The LMR-LRT can be used in mixture modeling to compare the fit of the specified class solution ( k -class model) to a model with fewer classes ( k -1 class model). A non-significant chi-square value suggests that a model with one fewer class is preferred. Entropy statistics, which measure the separation of the classes based on the posterior class membership probabilities, were also examined; entropy values approaching 1 indicate clear separation between classes [ 69 ].

After determining the latent class model in step 1, the second step of the analyses used the latent class posterior distribution to generate a nominal variable N , which represented the most likely class [ 64 ]. During the third step, the measurement error for N was accounted for while the model was estimated with the outcomes and predictor auxiliary variables [ 64 ]. The last step of the analysis examined whether race/ethnic and gender categories predict class membership, and whether class membership predicts the outcomes of interest.

All analyses were conducted using MPlus v. 7.11 [ 70 ], and used longitudinal weights to account for differential probabilities of selection at each sampling stage and to adjust for the effects of non-response. A robust standard error estimator was used in MPlus to account for the clustering of observations in the ECLS-K.

Four distinct classes of advantage/disadvantage were identified in the latent class analysis (see Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141363.t001

Class characteristics are shown in Table A in S1 File . Trajectories of advantage and disadvantage were stable across ECLS-K waves, so that none of the classes identified changed in individual and contextual characteristics across time. The largest proportion of the sample (47%; Class 3: Individually and Contextually Wealthy) lived in individual and contextual privilege, with very low proportions of children in socioeconomic deprived contexts. A class representing the opposite characteristics (children living in individually- and contextually-deprived circumstances) was also identified in the analyses (19%; Class 1: Individually and Contextually Disadvantaged). Class 1 had the highest proportion of children living in socioeconomic deprivation, attending schools with more than 50% racial/ethnic minority students, and living in unsafe neighborhoods, but did not have a high proportion of children with the lowest parental expectations. Class 4 (19%; Individually Disadvantaged, Contextually Wealthy) had the highest proportion of children with the lowest parental expectations (parents reporting across waves that they expected children to achieve up to a high school education). Class 4 (Individually Disadvantaged, Contextually Wealthy) also had high proportions of children living in individual-level socioeconomic deprivation, but had low proportions of children attending a school with over 50% of children eligible for free school meals. It also had relatively low proportions of children living in unsafe neighborhoods and low proportions of children attending diverse schools, forming a class with a mixture of individual-level deprivation, and contextual-level advantage. The last class was composed of children who lived in individually-wealthy environments, but who also lived in unsafe neighborhoods and attended diverse schools where more than 50% of pupils were eligible for free school meals (13%; Class 2: Individually Wealthy, Contextually Disadvantaged; see Table A in S1 File ).

The combined intersecting racial/ethnic and gender characteristics yielded six groups consisting of White boys (n = 2998), White girls (n = 2899), Black boys (n = 553), Black girls (n = 560), Latino boys (n = 961), and Latina girls (n = 949). All pairs containing at least one minority status of either race/ethnicity or gender (e.g., Black boys, Black girls, Latino boys, Latina girls) were more likely than White boys to be assigned to the more disadvantaged classes, as compared to being assigned to Class 3, the least disadvantaged (see Table B in S1 File ).

Racial/Ethnic and Gender Differences in Eighth-Grade Academic Outcomes

Table 2 shows broad patterns of intersecting racial/ethnic and gender inequalities in academic outcomes, although interesting differences emerge across racial/ethnic and gender groups. Whereas Black boys achieved lower scores than White boys across all classes on the math, reading and science assessments, this was not the case for Latino boys, who only underperformed White boys on the science assessment within the most privileged class (Class 3: Individually and Contextually Wealthy). Latina girls, in contrast, outperformed White boys on reading scores within Class 4 (Individually Disadvantaged, Contextually Wealthy), but scored lower than White boys on science and math assessments, although only when in the two most privileged classes (Class 3 and 4). For Black girls the effect of class membership was not as pronounced, and they had lower science and math scores than White boys across all but one instance.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141363.t002

In general, the largest inequalities in academic outcomes across racial/ethnic and gender groups appeared in the most privileged classes. For example, results show no differences in math scores across racial/ethnic and gender categories within Class 4, the most disadvantaged class, but in all other classes that contain an element of advantage, and particularly in Class 3 (Individually and Contextually Wealthy), there are large gaps in math scores across racial/ethnic and gender groups, when compared to White boys. These patterns of heightened inequality in the most advantaged classes are similar for reading and science scores (see Table 2 ).

Racial/Ethnic and Gender Differences in Eighth-Grade Non-Academic Outcomes

Interestingly, racialized and gendered patterns of inequality observed in academic outcomes were not as stark in non-cognitive academic outcomes (see Table 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141363.t003

Racial/ethnic and gender differences were small across socioemotional outcomes, and in fact, White boys were outperformed on several outcomes. Black boys scored lower than White boys on internalizing behavior and higher on self-concept within Classes 2 (Individually Wealthy, Contextually Disadvantaged) and 4 (Individually Disadvantaged, Contextually Wealthy), and Black girls scored higher than White boys on self-concept within Classes 2 and 3 (Individually Wealthy, Contextually Disadvantaged, and Individually and Contextually Wealthy, respectively). White and Latina girls, but not Black girls, scored higher than White boys on internalizing behavior (within Classes 3 and 4 for White girls, and within Classes 1 and 3 for Latina girls; see Table 3 ).

As with academic outcomes, most racial/ethnic and gender differences also emerged within the most privileged classes, and particularly in Class 3 (Individually and Contextually Wealthy), although in the case of perceived interest/competence in reading, White and Latina girls performed better than White boys. White girls also reported higher perceived interest/competence in reading than White boys in Class 4: Individually Disadvantaged, Contextually Wealthy.

This study set out to examine inequalities across several eighth grade academic and non-academic outcomes at the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. It first identified four classes of longstanding individual- and contextual-level disadvantage; then determined membership to these classes depending on racial/ethnic and gender groups; and finally compared non-cognitive skills, academic assessment scores, and socioemotional outcomes across intersecting gender, racial/ethnic and socioeconomic social positions.

Results show the clear influence of race/ethnicity in determining membership to the most disadvantaged classes. Across gender dichotomies, Black students were more likely than White boys to be assigned to all classes of disadvantage as compared to the most advantaged class, and this was particularly strong for the most disadvantaged class, which included elements of both individual- and contextual-level disadvantage. Latino boys and girls were also more likely than White boys to be assigned to all the disadvantaged classes, but the strength of the association was much smaller than for Black students. Whereas membership into classes of disadvantage appears to be more a result of structural inequalities strongly driven by race/ethnicity, the salience of gender is apparent in the distribution of academic assessment outcomes within classes of disadvantage. Results show a gendered pattern of math, reading and science assessments, particularly in the most privileged class, where girls from all ethnic/racial groups (although mostly from Black and Latino racial/ethnic groups) underperform White boys in math and science, and where Black boys score lower, and White girls higher, than White boys in reading.

With the exception of educational assessments, gender and racial/ethnic inequalities within classes are either not very pronounced or in the opposite direction (e.g. racial/ethnic and gender minorities outperform White males), but differences in outcomes across classes are stark. The strength of the association between race/ethnicity and class membership, and the reduced racial/ethnic and gender inequalities within classes of advantage and disadvantage, attest to the importance of socioeconomic status and wealth in explaining racial/ethnic inequalities; should individual and contextual disadvantage be comparable across racial/ethnic groups, racial/ethnic inequalities would be substantially reduced. This being said, most within-class differences were observed in the most privileged classes, showing that benefits brought about by affluence and advantage are not equal across racial/ethnic and gender groups. The measures of advantage and disadvantage captured in this study relate to characteristics afforded by parental resources, implying an intergenerational transmission of disadvantage, regardless of the presence of absolute adversity in childhood. This pattern of differential returns of affluence has been shown in other studies, which report that White teenagers benefit more from the presence of affluent neighbors than do Black teenagers [ 71 ]. Among adult populations, studies show that across several health outcomes, highly educated Black adults fare worse than White adults with the lowest education [ 72 ]. Intersectional approaches such as the one applied in this study reveal how power within gendered and racialized institutional settings operates to undermine access to and use of resources that would otherwise be available to individuals of advantaged classes [ 72 ]. The present study further contributes to this literature by documenting how, in a key stage of the life course, similar levels of advantage, but not disadvantage, lead to different academic outcomes across racial/ethnic and gender groups. These findings suggest that, should socioeconomic inequalities be addressed, and levels of advantage were similar across racial/ethnic and gender groups, systems of oppression that pattern the racialization and socialization of children into racial/ethnic and gender roles in society would still ensure that inequalities in academic outcomes existed across racial/ethnic and gender categories. In other words, racism and sexism have a direct effect on academic and non-academic outcomes among 8 th graders, independent of the effect of socioeconomic disadvantage on these outcomes. An important limitation of the current study is that although it uses a comprehensive measure of advantage/disadvantage, including elements of deprivation and affluence at the family, school and neighborhood levels through time, it failed to capture these two key causal determinants of racial/ethnic and gender inequality: experiences of racial and gender discrimination.

Despite this limitation, it is important to note that socioeconomic inequalities in the US are driven by racial and gender bias and discrimination at structural and individual levels, with race and gender discrimination exerting a strong influence on academic and non-academic inequalities. Racial discrimination, prevalent in the US and in other industrialized nations [ 38 , 73 ] determines differential life opportunities and resources across racial/ethnic groups, and is a crucial determinant of racial/ethnic inequalities in health and development throughout life and across generations [ 37 , 38 ]. In the context of this study’s primary outcomes within school settings, racism and racial discrimination experienced by both the parents and the children are likely to contribute towards explaining observed racial/ethnic inequalities in outcomes within classes of disadvantage. Gender discrimination—another system of oppression—is apparent in this study in relation to academic subjects socially considered as typically male or female orientated. For example, results show no difference between Black girls and White boys from the most advantaged class in terms of perceived interest and competence in math but, in this same class, Black girls score much lower than White boys in the math assessment. This difference, not explained by intrinsic or socioeconomic differences, can be contextualized as a consequence of experienced intersecting racial and gender discrimination. The consequences of the intersection between two marginalized identities are found throughout the results of this study when comparing across broad categorizations of race/ethnicity and gender, and in more detailed conceptualizations of minority status. Growing up Black, Latino or White in the US is not the same for boys and girls, and growing up as a boy or a girl in America does not lead to the same outcomes and opportunities for Black, Latino and White children as they become adults. With this study’s approach of intersectionality one can observe the complexity of how gender and race/ethnicity intersect to create unique academic and non-academic outcomes. This includes the contrasting results found for Black and Latino boys, when compared to White boys, which show very few examples of poorer outcomes among Latino boys, but several instances among Black boys. Results also show different racialization for Black and Latina girls. Latina girls, but not Black girls, report higher internalizing behavior than White boys, whereas Black girls, but not Latina girls, report higher self-concept than White boys. Black boys also report higher self-concept and lower internalizing behavior than White boys, findings that mirror research on self-esteem among Black adolescents [ 74 , 75 ]. In cognitive assessments, intersecting racial/ethnic and gender differences emerge across classes of disadvantage. For example, Black girls in all four classes score lower on science scores than White boys, but only Latina girls in the most advantaged class score lower than White boys. Although one can observe differences in the racialization of Black and Latino boys and girls across classes of disadvantage, findings about broad differences across Latino children compared to Black and White children should be interpreted with caution. The Latino ethnic group is a large, heterogeneous group, representing 16.7% of the total US population [ 76 ]. The Latino population is composed of a variety of different sub-groups with diverse national origins and migration histories [ 77 ], which has led to differences in sociodemographic characteristics and lived experiences of ethnicity and minority status among the various groups. Differences across Latino sub-groups are widely documented, and pooled analyses such as those reported here are masking differences across Latino sub-groups, and providing biased comparisons between Latino children, and Black and White children.

Poorer performance of girls and racial/ethnic minority students in science and math assessments (but not in self-perceived competence and interest) might result from stereotype threat, whereby negative stereotypes of a group influence their member’s performance [ 78 ]. Stereotype threat posits that awareness of a social stereotype that reflects negatively on one's social group can negatively affect the performance of group members [ 35 ]. Reduced performance only occurs in a threatening situation (e.g., a test) where individuals are aware of the stereotype. Studies show that early adolescence is a time when youth become aware of and begin to endorse traditional gender and racial/ethnic stereotypes [ 79 ]. Findings among youth parallel findings among adult populations, which show that adult men are generally perceived to be more competent than women, but that these perceptions do not necessarily hold for Black men [ 80 ]. These stereotypes have strong implications for interpersonal interactions and for the wider structuring of systemic racial/ethnic and gender inequalities. An example of the consequences of negative racial/ethnic and gender stereotypes as children grow up is the well-documented racial/ethnic and gender pay gap: women earn less than men [ 81 ], and racial/ethnic minority women and men earn less than White men [ 82 ].

In addition to the focus on intersectionality, a strength of this study is its person-centered methodological approach, which incorporates measures of advantage and disadvantage across individual and contextual levels through nine years of children’s socialization. Children live within multiple contexts, with risk factors at the family, school, and neighborhood level contributing to their development and wellbeing. Individual risk factors seldom operate in isolation [ 83 ], and they are often strongly associated both within and across levels [ 84 ]. All risk factors captured in the latent class analyses have been independently associated with increased risk for academic problems [ 10 , 71 , 85 , 86 ], and given that combinations of risk factors that cut across multiple domains explain the association between early risk and later outcomes better than any isolated risk factor [ 83 , 84 ], the incorporation of person-centered and intersectionality approaches to the study of racial/ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic inequalities across school outcomes provides new insight into how children in marginalized social groups are socialized in the early life course.

Conclusions

The contrasting outcomes between racial/ethnic and gender minorities in self-assessment and socioemotional outcomes, as compared to standardized assessments, provide support for the detrimental effect that intersecting racial/ethnic and gender discrimination have in patterning academic outcomes that predict success in adult life. Interventions to eliminate achievement gaps cannot fully succeed as long as social stratification caused by gender and racial discrimination is not addressed [ 87 , 88 ].

Supporting Information

S1 file. supporting tables..

Table A: Class characteristics. Table B: Associations between race/ethnicity and gender groups and assigned class membership (membership to Classes 1, 2 or 4 as compared to Class 3: Individually and Contextually Wealthy).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141363.s001

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an ESRC grant (ES/K001582/1) and a Hallsworth Research Fellowship to LB. Most of this work was conducted while LB was a visiting scholar at the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. She would like to thank them for hosting her visit and for the support provided.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: LB. Performed the experiments: LB. Analyzed the data: LB. Wrote the paper: LB NP.

- 1. Jencks C, Phillips M. The Black-White Test Score Gap. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press; 1998.

- 2. (NCES) NCfES. The Nation’s Report Card: Science 2011(NCES 2012–465). Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2012.

- 3. (NCES) NCfES. The Nation’s Report Card: A First Look: 2013 Mathematics and Reading (NCES 2014–451). Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2013.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 12. Ogbu J. Low performance as an adaptation: The case of blacks in Stockton, California. In: Gibson M, Ogbu J, editors. Minority Status and Schooling. New York: Grand Publishing; 1991.

- 41. Coley R. Differences in the gender gap: Comparisons across racial/ethnic groups in education and work. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service, 2001.

- 47. Hankivsky O, Cormier R. Intersectionality: Moving women’s health research and policy forward. Vancouver: Women’s Health Research Network; 2009.

- 48. Dhamoon K, Hankivsky O. Why the theory and practice of intersectionality matter to health research and policy. In: Hankivsky O, editor. Health Inequities in Canada: Intersectional Frameworks and Practices. Vancouver: UBC Press; 2011. p. 16–50.

- 50. Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989:139–67.

- 62. Tourangeau K, Nord C, Lê T, Sorongon A, Najarian M. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–99 (ECLS-K), Combined User’s Manual for the ECLS-K Eighth-Grade and K–8 Full Sample Data Files and Electronic Codebooks (NCES 2009–004). Washington, DC.: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education., 2009.

- 63. Marsh HW. Self Description Questionnaire (SDQ) II: A theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of multiple dimensions of adolescent self-concept. An interim test manual and a research monograph. Sydney: University of Western Sydney: 1992.

- 64. Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Auxiliary Variables in Mixture Modeling: 3-Step Approaches Using Mplus. Mplus Web Notes [Internet]. 2013 April 2014. Available from: www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote15.pdf .

- 67. Dayton C. Latent class scaling analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998.

- 70. Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA.: 2012.

- 72. Jackson P, Williams D. The intersection of race, gender, and SES: Health paradoxes. In: Schulz A, Mullings L, editors. Gender, Race, Class, & Health: Intersectional Approaches. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006. p. 131–62.

- 76. Ennis S, Rios-Vargas M, Albert N. The Hispanic Population: 2010. United Census Bureau, 2011.

- 88. Rouse C, Brooks-Gunn J, McLanahan S. School Readiness: Closing racial and ethnic gaps. Washington, DC: Brookings Press, 2005.

Change Password

Your password must have 8 characters or more and contain 3 of the following:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

- Sign in / Register

Request Username

Can't sign in? Forgot your username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Reframing Educational Outcomes: Moving beyond Achievement Gaps

- Sarita Y. Shukla

- Elli J. Theobald

- Joel K. Abraham

- Rebecca M. Price

School of Educational Studies, University of Washington, Bothell, Bothell, WA 98011-8246

Search for more papers by this author

Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, Seattle, WA 98195

Department of Biological Science, California State University–Fullerton, Fullerton, CA 92831

*Address correspondence to: Rebecca M. Price ( E-mail Address: [email protected] )

School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, University of Washington, Bothell, Bothell, WA 98011-8246

The term “achievement gap” has a negative and racialized history, and using the term reinforces a deficit mindset that is ingrained in U.S. educational systems. In this essay, we review the literature that demonstrates why “achievement gap” reflects deficit thinking. We explain why biology education researchers should avoid using the phrase and also caution that changing vocabulary alone will not suffice. Instead, we suggest that researchers explicitly apply frameworks that are supportive, name racially systemic inequities and embrace student identity. We review four such frameworks—opportunity gaps, educational debt, community cultural wealth, and ethics of care—and reinterpret salient examples from biology education research as an example of each framework. Although not exhaustive, these descriptions form a starting place for biology education researchers to explicitly name systems-level and asset-based frameworks as they work to end educational inequities.

INTRODUCTION

Inequities plague educational systems in the United States, from pre-K through graduate school. Many of these inequities exist along racial, gender, and socioeconomic lines ( Kozol, 2005 ; Sadker et al. , 2009 ), and they impact the educational outcomes of students. For decades, education research has focused on comparisons of these educational outcomes, particularly with respect to test scores of students across racial and ethnic identities. The persistent differences in these test scores or other outcomes are often referred to as “achievement gaps,” which in turn serve as the basis for numerous educational policy and structural changes ( Carey, 2014 ).

A recent essay in CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) questioned narrowly defining “success” in educational settings ( Weatherton and Schussler, 2021 ). The authors posit that success must be defined and contextualized, and they asked the community to recognize the racial undercurrents associated with defining success as limited to high test scores and grade point averages (GPAs; Weatherton and Schussler, 2021 ). In this essay, we make a complementary point. We contend that the term “achievement gap” is misaligned with the intent and focus of recent biology education research. We base this realization on the fact that the term “achievement gap” can have a deeper meaning than documenting a difference among otherwise equal groups ( Kendi, 2019 ; Gouvea, 2021 ). It triggers deficit thinking ( Quinn, 2020 ); unnecessarily centers middle and upper class, White, male students as the norm ( Milner, 2012 ); and downplays the impact of structural inequities ( Ladson-Billings, 2006 ; Carter and Welner, 2013 ).

This essay unpacks the negative consequences of using the term “achievement gap” when comparing student learning across different racial groups. We advocate for abandoning the term. Similarly, we suggest that, in addition to changing our terminology, biology education researchers can explicitly apply theoretical frameworks that are more appropriate for interrogating inequities among educational outcomes across students from different demographics. We emphasize that the idea that a simple “find and replace,” swapping out the term “achievement gap” for other phrases, is not sufficient.

In the heart of this essay, we review some of these systems-level and asset-based frameworks for research that explores differences in academic performance ( Figure 1 ): opportunity gaps ( Carter and Welner, 2013 ), educational debt ( Ladson-Billings, 2006 ), community cultural wealth ( Yosso, 2005 ), and ethics of care ( Noddings, 1988 ). Within each of these frameworks, we review examples of biology education literature that we believe rely on them, explicitly or implicitly. We conclude by reiterating the need for education researchers to name explicitly the systems-level and asset-based frameworks used in future research.

FIGURE 1. Research frameworks highlighted in the essay. The column in gray summarizes deficit-based frameworks that focus on achievement gaps. The middle column (in gold) includes examples of systems-based frameworks that acknowledge that student learning is associated with society-wide habits. The rightmost columns (in peach) include examples of asset-based models that associate student learning with students’ strengths. The columns are not mutually exclusive, in that studies can draw from multiple frameworks simultaneously or sequentially.

We will use the phrase “students from historically or currently marginalized groups” to describe the students who have been and still are furthest from the center of educational justice. However, when discussing work of other researchers, we will use the terminology they use in their papers. Our conceptualization of this phrase matches, as near as we can tell, Asai’s phrase “PEERs—persons excluded for their ethnicity or race” ( Asai, 2020 , p. 754). We also choose to capitalize “White” to acknowledge that people in this category have a visible racial identity ( Painter, 2020 ).

Positionality

Our positionalities—our unique life experiences and identities—mediate our understanding of the world ( Takacs, 2003 ). What we see as salient in our research situation arises from our own life experiences. Choices in our research, including the types of data we collect and how we clean the data and prepare it for analysis, adopt analytical tools, and make sense of these analyses are important decision points that affect study results and our findings ( Huntington-Klein et al. , 2021 ). We recognize that it is impossible to be free of bias ( Noble, 2018 ; Obermeyer et al. , 2019 ). Therefore, we put forth our positionality to acknowledge the lenses through which we make decisions as researchers and to forefront the impact of our identities on our research. Still, the breadth of our experiences cannot be described fully in a few sentences.

The four authors of this essay have unique and complementary life experiences that contribute to the sense-making presented in this essay. S.Y.S. has been teaching since 2003 and teaching in higher education since 2012. She is a South Asian immigrant to the United States, and a cisgender woman. E.J.T. has taught middle school, high school, and college science since 2006. She is a cisgender White woman. J.K.A. is a cisgender Black mixed-race man who comes from a family of relatively recent immigrants with different educational paths. He has worked in formal and informal education since 2000. R.M.P. is a cisgender Jewish, White woman, and she has been teaching college since 2006. We represent a team of people who explicitly acknowledge that our experiences influence the lenses through which we work. Our guiding principles are 1) progress over perfection, 2) continual reflection and self-improvement, and 3) deep care for students. These principles guide our research and teaching, impacting our interactions with colleagues (faculty and staff) as well as students. Ultimately, these principles motivate us to make ourselves aware of, reflect on, and learn from our mistakes.

Simply Changing Vocabulary Does Not Suffice

The term “achievement gap” is used in research that examines differences in achievement—commonly defined as differences in test scores—across students from different demographic groups ( Coleman et al. , 1966 ). Some studies replace “achievement gap” with “score gap” (e.g., Jencks and Phillips, 2006 ), because it defines the type of achievement under consideration; others use “opportunity gap,” because it emphasizes differences in opportunities students have had throughout their educational history (e.g., Carter and Welner, 2013 ; more on opportunity gaps later). The shift for which we advocate, however, does not reside only with terminology. Instead, we call for a deeper shift of using research frameworks that acknowledge and respect students’ histories and empower them now.

The underlying framework in research that uses “achievement gap” or even “score gap” may not be immediately apparent. Take for example two studies that both use the seemingly benign term, “score gap.” A close read indicates that one study attributed the difference in test scores between Black and White students to deficient “culture and child-rearing practices” ( Farkas, 2004 , p. 18). Thus, even though the researcher uses what can be considered to be more neutral terminology, the phrase in this context represents deficit thinking and blame. On the other hand, another study uses the term “score gap” to explore differences that have been historically studied through cultures of poverty, genetic, and familial backgrounds ( Jencks and Phillips, 2006 ). While these researchers discuss the Black–White score gap, they present evidence that examines this phenomenon with nuanced constructs, such as stereotype threat ( Steele, 2011 ) and resources available. These authors also mention ways to reduce score gaps, such as smaller class sizes and high teacher expectations ( Jencks and Phillips, 2006 ).

Some researchers who use the phrase “achievement gap” explicitly avoid deficit thinking and instead embrace an asset-based framework. Jordt et al. (2017) address systemic racism, just as Jencks and Phillips (2006) do. Specifically, Jordt et al. (2017) identified an intervention that affirmed student values that might also be a potential tool for increasing underrepresented minority (URM) student exam scores in college-level introductory science courses. The researchers found that this intervention produced a 4.2% increase in exam performance for male URM students and a 2.2% increase for female URM students. Thus, while they use “achievement gap” throughout the paper to refer to racial and gender differences in exam scores, the study focused on ways to support URM student success.

In pursuit of improved language and clarity of intent, the term “achievement gap” should be replaced to reflect the research framework used to interrogate educational outcomes within and across demographic groups.

DEFICIT THINKING

Deficit thinking describes a mindset, or research framework, in which differences in outcomes between members of different groups, generally a politically and economically dominant group and an oppressed group, are attributed to a quality that is lacking in the biology, culture, or mindset of the oppressed group ( Valencia, 1997 ). Deficit thinking has pervaded public and academic discourse about the education of students from different races and ethnicities in the United States for centuries ( Menchaca, 1997 ).

Tenacious deficit-based explanations blame students from historically or currently marginalized groups for lower educational attainment. These falsities include biological inferiority due to brain size or structure ( Menchaca, 1997 ), negative cultural attributes such as inferior language acquisition ( Dudley-Marling, 2007 ), and accumulated deficits due to a “culture of poverty” ( Pearl, 1997 ; Gorski, 2016 ). More recently, lower achievement has been attributed to a lack of “grit” ( Ris, 2015 ) or the propensity for a “fixed” mindset ( Gorski, 2016 ; Tewell, 2020 ). While ideas around grit and mindset have demonstrable value in certain circumstances (e.g., Hacisalihoglu et al. , 2020 ), they fall short as primary explanations for differences in educational outcomes, because they focus attention on perceived deficits of students while providing little information about structural influences on failure and success, including how we define those constructs ( Harper, 2010 ; Gorski, 2016 ). In other words, deficit models often posit students as the people responsible for improving their own educational outcomes ( Figure 1 ).

Deficit thinking, regardless of intent, blames individuals, their families, their schools, or their greater communities for the consequences of societal inequities ( Yosso, 2006 ; Figure 1 ). This blame ignores the historic and structural drivers of inequity in our society, placing demands on members of underserved groups to adapt to unfair systems ( Valencia, 1997 ). A well-documented example of structural inequity is the consistent underresourcing of public schools that serve primarily students of color and children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds ( Darling-Hammond, 2013 ; Rothstein, 2013 ). Because learning is heavily influenced by factors outside the school environment, such as food security, trauma, and health ( Rothstein, 2013 ), schools themselves reflect gross disparities in resourcing based on historic discrimination ( Darling-Hammond, 2013 ). Deficit thinking focuses on student or cultural characteristics to explain performance differences and tends to overlook or minimize the impacts of systemic disparities. Deficit thinking also strengthens the narrative around student groups in terms of shortcomings, reinforces negative stereotypes, and ignores successes or drivers of success in those same groups ( Harper, 2015 ).

Achievement Gaps

The term “achievement gap” has historically described the difference in scores attained by students from racial and ethnic minority groups compared with White students on standardized tests or course exams ( Coleman et al. , 1966 ). As students from other historically or currently marginalized groups, such as female or first-generation students, are increasingly centered in research, the term is now used more broadly to compare any student population to White, middle and upper class, men ( Harper, 2010 ; Milner, 2012 ). Using White men as the basis for comparison comes at the expense of students from other groups ( Harper, 2010 ; Milner, 2012 ). Basing comparisons on the cultural perspectives of a single dominant group leads to “differences” being interpreted as “deficits,” which risks dehumanizing people in the marginalized groups ( Dinishak, 2016 ). Furthermore, centering White, wealthy, male performance means that even students from groups that tend to have higher test scores, like Asian-American students, risk dehumanization as “model minorities” or “just good at math” ( Shah, 2019 ).

Many researchers have highlighted the fact that the term “achievement gap” is a part of broader deficit-thinking models and rooted in racial hierarchy ( Ladson-Billings, 2006 ; Gutiérrez, 2008 ; Martin, 2009 ; Milner, 2012 ; Kendi, 2019 ). Focusing on achievement gaps emphasizes between-group differences over within-group differences ( Young et al. , 2017 ), reifies sociopolitical and historical groupings of people ( Martin, 2009 ), and minimizes attention to structural inequalities in education ( Ladson-Billings, 2006 ; Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools, 2018 ). Gutiérrez (2008) names this obsession with achievement gaps as a “gap-gazing fetish” that draws attention away from finding solutions that promote equitable learning ( Gutiérrez, 2008 ). Under a deficit-thinking model, achievement gaps are viewed as the primary problem, rather than a symptom of the problem ( Gutiérrez, 2008 ), and for decades they have been attributed to different characteristics of the demographics being compared ( Valencia, 1997 ). As such, proposed solutions tend to be couched in terms of remediation for students ( Figure 1 ).

Ignoring the social context of students’ education necessarily limits inferences that can be drawn about their success. Limiting measures of educational success, also conceptualized as achievement, to performance on exams or overall college GPA, often leaves out consideration of other potential data sources ( Weatherton and Schussler, 2021 ; Figure 2 ). This narrow perspective tends to perpetuate the systems of power and privilege that are already in place ( Gutiérrez, 2008 ). The biology education research community can instead broaden its sense of success to recognize the underlying historical and current contexts and the intersections of identities (e.g., racial, gender, socioeconomic) that contribute to those differences ( Weatherton and Schussler, 2021 ).

FIGURE 2. A selection of potential data sources that could inform researchers about within- and between-group differences in educational outcomes. This list does not encompass the full range of possible data sources, nor does it imply a hierarchy to the data. Instead, it reflects some of the diversity of quantitative and qualitative data that are directly linked to student outcomes and that are used under multiple research frameworks.

In biology education research, many papers still use the language of “achievement gap,” even in instances when researchers explicitly or implicitly use other nondeficit frameworks. While some may argue that this language merely describes a pattern, its origin and history is explicitly and inextricably linked to deficit-thinking models ( Gutiérrez, 2008 ; Milner, 2012 ). Thus, we join others in the choice to abandon the term “achievement gap” in favor of language—and frameworks—that align better to the goals of our research and to avoid the limitations and harm that can arise through its use.

Example: Focusing on Achievement Gaps Can Reinforce Racial Stereotypes

Messages of perpetual underachievement can inadvertently reinforce negative stereotypes. For example, Quinn (2020) demonstrated that, when participants watched a 2-minute video of a newscast using the term “achievement gap,” they disproportionately underpredicted the graduation rate of Black students relative to White students, even more so than participants in a control group who watched a counter-stereotypical video. They also scored significantly higher on an instrument measuring bias. Because bias is dynamic and affected by the environment, Quinn concludes that the video discussing the achievement gap likely heightened the bias of the participants ( Quinn, 2020 ).

Education researchers, just like the participants in Quinn’s (2020) study, inadvertently carry implicit bias against students from the different groups they study, and those biases can shift depending on context. Quinn (2020) demonstrates that just using the term “achievement gap” can reinforce the pervasive racial hierarchy that places Black students at the bottom. Researchers, without intending to, can be complicit in a system of White privilege and power if the language and frameworks underlying their study design, data collection, and/or data interpretation are aligned with bias and stereotype. If the goal is to dismantle inequities in our educational systems and research on those systems, the biology education research community must consider the historical and social weight of its literature to address racism head on, as progressive articles have been doing (e.g., Eddy and Hogan, 2014 ; Canning et al. , 2019 ; Theobald et al. , 2020 ).

SYSTEMS-LEVEL FRAMEWORKS

To move away from the achievement gap discourse—because of the history of the term, the perceived blame toward individual students, as well as the deficit thinking the term may imbue and provoke—we highlight some of the other frameworks for understanding student outcomes. We conclude discussion of each framework with an example from education research that can be reinterpreted within it, keeping in mind that multiple frameworks can be applied to different studies. We acknowledge two caveats about these reinterpretations: first, we are adding another layer of interpretation to the original studies, and we cannot claim that the original authors agree with these interpretations; second, each example could be interpreted through multiple frameworks, especially because these frameworks overlap ( Figure 1 ).

In this section, we begin at the systems level by examining opportunity gaps and educational debt. Rather than blaming students or their cultures for deficits in performance, these systems-level perspectives name white supremacy and the concomitant policies that maintain power imbalances as the cause of disparate student experiences.

Opportunity Gaps

The framework of opportunity gaps shifts the onus of differential student performance away from individual deficiencies and assigns solutions to actions that address systemic racism ( Milner, 2012 ; Figure 1 ). Specifically, opportunity gaps embody the difference in performance between students from historically and currently marginalized groups and middle and upper class, White, male students, with primary emphasis on opportunities that students have or have not had, rather than on their current performance (i.e., achievement) in a class ( Milner, 2012 ). Compared with deficit models, the focus shifts from assigning responsibility for the gap from the individual to society ( Figure 1 ).

Some researchers explore opportunity gaps by discussing the structural challenges that students from historically and currently marginalized groups have been facing (e.g., Rothstein, 2013 ). For example, poor funding in K–12 schools leads to inconsistent, poorly qualified, and poorly compensated teachers; few and outdated textbooks ( Darling-Hammond, 2013 ); limited field trips; a lack of extracurricular resources ( Rothstein, 2013 ); and inadequately supplied and cleaned bathrooms ( Darling-Hammond, 2013 ). Additional structural challenges that occur outside school buildings, but impact learning, include poor health and lack of medical care, food and housing insecurity, lead poisoning and iron deficiency, asthma, and depression ( Rothstein, 2013 ).

While the literature about opportunity gaps focuses more on K–12 than higher education ( Carter and Welner, 2013 ), college instructors can exacerbate opportunity gaps by biasing who has privilege (i.e., opportunities) in their classrooms. For example, some biology education literature focuses on how instructors’ implicit biases impact our students, such as by unconsciously elevating the status of males in the classroom ( Eddy et al. , 2014 ; Grunspan et al. , 2016 ).

Example: CUREs Can Prevent Opportunity Gaps.

Course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs) are one way to prevent opportunity gaps (e.g., Bangera and Brownell, 2014 ; CUREnet, n.d. ). Specifically, we interpret the suggestions that Bangera and Brownell (2014) make about building CUREs as a way to recognize that some students have the opportunity to participate in undergraduate research experiences while others do not. For example, students who access extracurricular research opportunities are likely relatively comfortable talking to faculty and, in many cases, have the financial resources to pursue unpaid laboratory positions ( Bangera and Brownell, 2014 ). More broadly, when research experiences occur outside the curriculum, they privilege students who know how to pursue and gain access to them. However, CUREs institutionalize the opportunity to conduct research, so that every student benefits from conducting research while pursuing an undergraduate degree.

Educational Debt

Ladson-Billings (2006) submits that American society has an educational debt, rather than an educational deficit. This framework shifts the work of finding solutions to educational inequities away from individuals and onto systems ( Figure 1 ). The metaphor is economic: A deficit refers to current mismanagement of funds, but a debt is the systematic accumulation of mismanagement over time. Therefore, differences in student performances are framed by a history that reflects amoral, systemic, sociopolitical, and economic inequities. Ladson-Billing ( 2006 ) suggests that focusing on debts highlights injustices that Black, Latina/o, and recent immigrant students have incurred: Focusing on student achievement in the absence of a discussion of past injustices does not redress the ways in which students and their parents have been denied access to educational opportunities, nor does it redress the ways in which structural and institutional racism dictate differences in performance. This approach begins by acknowledging the structural and institutional barriers to achievement in order to dismantle existing inequities. This reframing helps set the scope of the problem and identify a more accurate and just lens through which we make sense of the problem ( Cho et al. , 2013 ).

Example: NSF Supports Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

From my own (yet to be published) research, a participant described the HBCU where he studied physics as providing a “dome of security and safety.” In contrast, he recounted that when he attended a predominantly White institution, he constantly needed to be guarded and employ “his body sense,” an act that made him tense, defensive, and unable to listen. ( Rankins, 2019 , p. 50)

Example: Institutions Can Repay Educational Debt.

Institutions can repay educational debt by ensuring that their students have the resources and support structures necessary to succeed. The Biology Scholars Program at the University of California, Berkeley, is a prime example ( Matsui et al. , 2003 ; Estrada et al. , 2019 ). This program, begun in 1992 ( Matsui et al. , 2003 ) and still going strong ( Berkeley Biology Scholars Program, n.d. ), creates physical and psychological spaces that support learning: a study space and study groups, paid research experiences, and thoughtful mentoring. The students recruited to the program are from first-generation, low-socioeconomic status backgrounds and from groups that are historically underrepresented. When the students enter college, they have lower GPAs and Scholastic Aptitude Test scores than their counterparts with the same demographic profile who are not in the program. And yet, when they graduate, students in the Biology Scholars Program have higher GPAs and higher retention in biology majors than their counterparts ( Matsui et al. , 2003 ), perhaps because of the extended social support they receive from peers ( Estrada et al. , 2021 ). Moreover, students in this program report lower levels of stress and a greater sense of well-being ( Estrada et al. , 2019 ).

ASSET-BASED FRAMEWORKS

In this section, we continue to explore frameworks that move away from the achievement gap discourse, now focusing on models that build from students’ strengths. We have chosen two frameworks whose implications seem particularly relevant to and coincident with anti-racist research in biology education: community cultural wealth ( Yosso, 2005 ) and ethics of care ( Noddings, 1988 ). As before, we reinterpret articles from the education literature to illustrate these frameworks, and we once again include the caveats that we extend beyond the authors’ original interpretations and that other frameworks could also be used to reinterpret the examples.

Community Cultural Wealth

One asset-based way to frame student outcomes is to begin with the strengths that people from different demographic groups hold ( Yosso, 2005 ). Rather than focusing on racism, this approach focuses on community cultural wealth. The premise is that everyone can contribute a wealth of knowledge and approaches from their own cultures ( Yosso, 2005 ).

Community cultural wealth begins with critical race theory (CRT; Yosso, 2005 ). CRT illuminates the impact of race and racism embedded in all aspects of life within U.S. society ( Omi and Winant, 2014 ). CRT acknowledges that racism is interconnected with the founding of the United States. Race is viewed in tandem with intersecting identities that oppose dominant ones, and the constructs of CRT emerge by attending to the experiences of people from communities of color ( Yosso, 2005 ). Therefore, the experiences of students of color are central to transformative education that addresses the overrepresentation of White philosophies. CRT calls on research to validate and center these perspectives to develop a critical understanding about racism.

Community cultural wealth builds on these ideas by viewing communities of color as a source of students’ strength ( Yosso, 2005 ). The purpose of schooling is to build on the strengths that students have when they arrive, rather than to treat students as voids that need to be filled: students’ cultural wealth must be acknowledged, affirmed, and amplified through their education. This approach is consistent with those working to decolonize scientific knowledge (e.g., Howard and Kern, 2019 ).

Example: Community Cultural Wealth Can Improve Mentoring.

Thompson and Jensen-Ryan (2018) offer advice to mentors about how to use cultural wealth to mentor undergraduate students in research. They identify the forms of scientific cultural capital that research mentors typically value, finding that these aspects of a scientific identity are closely associated with majority culture. They challenge mentors to broaden the forms of recognizable capital. For example, members of the faculty can actively recruit students into their labs from programs aimed to promote the diversity of scientists, rather than insisting that students approach them with their interest to work in the lab ( Thompson and Jensen-Ryan, 2018 ). They can recognize that undergraduate students may not express an interest in a research career–especially initially—but that research experience is still formative. They can recognize that students who are strong mentors to their peers are valuable members of a research team and that this skill is a form of scientific capital. They can value the diverse backgrounds of students in their labs, rather than insisting that they come from families that have prioritized scientific thinking and research. In sum, the gaps that Thompson and Jensen-Ryan (2018) identify are in research mentors’ attitudes, rather than in student performance.