How to defeat terrorism: Intelligence, integration, and development

Subscribe to global connection, norman loayza nl norman loayza lead economist, development research group - world bank.

July 25, 2016

My partner was caught at the Istanbul airport during the latest terrorist attack. She hid in a closet with a few people, including a small girl, disconcerted and afraid. And when the attack was over, she saw the blood, desolation, chaos, and tears of the aftermath. This was a horrific moment. Yet, it paled in comparison to what the injured and dead and their relatives had to suffer.

It seems that terrorism and political violence are becoming more prevalent and intense. They have been, however, long brewing and have affected many countries around the world. In the 1980s, my home country, Peru, suffered immensely from terrorism: The badly called “Shining Path” organization, with its communist ideology and ruthless tactics, terrorized first rural communities and then large cities with deadly bombs in crowded places and assassinations of official and civil society leaders.

A few years ago, Phil Keefer, lead economist at the World Bank, and I edited two books on what we perceived to be the main security threats of our time: terrorism and drug trafficking . We thought that the answers had to come from research, and we tried to gather the best available evidence and arguments to understand the links between these security threats and economic development.

After the myriad of recent terrorist attacks—in Istanbul, Munich, Nice, Bagdad, Brussels, and Paris, to name a few—we found it important to recap lessons learned. These lessons are not just academic: Understanding the root causes of terrorism can lead to policies for prevention and for reducing the severity of attacks. To defeat terrorism, a policy strategy should include three components: intelligence, integration, and development.

Intelligence . A terrorist attack is relatively easy to conduct. Modern societies offer many exposed and vulnerable targets: an airport, a crowded celebration by the beach, a bus station at peak hours, or a restaurant full of expats. And the potential weapons are too many to count: a squadron of suicide bombers, a big truck ramming through the streets, two or three comrades armed with semi-automatic guns. It is impossible to protect all flanks, and some of the measures taken to prevent the previous terrorist attacks are, well, frankly silly. For a strategy to have any chance against terrorism, it should be based on intelligence. Intelligence implies understanding the motivations, leadership structure, and modus operandi of terrorist organizations, and developing a plan that can anticipate and adapt to their constantly morphing operations. Importantly, the ideological dimension should not be ignored because it explains the extremes to which terrorists are willing to arrive: A suicide attack requires a person who has muted both his basic survival instinct and all sense of natural compassion for others. It was radical communism in the 1970s and 1980s; it is a perverted and fanatical misrepresentation of Islam nowadays. An intelligence strategy that targets the sources of terrorism, both the perpetrators and the social movements that underlie them, should be the first component of the campaign against terror.

Integration. Foreigners living in the U.S. like to make fun of Hollywood movies and the social rituals that Americans go through each year: Halloween and Thanksgiving are in many respects more popular than Christmas. Yet, thanks to these cultural norms along with widespread economic opportunities and equality under the law, the U.S. has mostly succeeded in what many countries, including some European ones, have failed: the integration of people of different ethnic, religious, and cultural backgrounds. The U.S. is no paradise of integration, but the social melting pot does work for immigrants: Within a generation or two, Mexican Americans, Italian Americans, Iranian Americans, and so forth are just Americans, with a single national identity and, at least by law, the same rights and obligations. In some European countries, in contrast, many immigrants feel like second-class citizens. There is little that can inflame more hatred than the feeling of being excluded, and a misguided search for a sense of belonging can be the trigger that incites religious, ethnic, and ideological radicalization. This may explain why France has suffered more from terrorist acts perpetrated by their own residents than the U.S. or U.K., that paradoxically are substantially more engaged in the war against ISIS and al-Qaeda. Social integration—especially of immigrants—through explicit and targeted programs from education at an early age to immigration and citizenship reforms is a key component in the fight against terrorism.

Development. One of the puzzles in the evidence on terrorism is that while it tends to be led (and sometimes even perpetrated) by well-off and educated people, it represents the complaints and grievances of the disenfranchised, the poor, and the unemployed. The hundreds of thousands of unemployed and discouraged young men in places as diverse as Afghanistan, Somalia, South Africa, and Brazil are the potential armies of common and political violence. In South Africa and Brazil, lacking an overriding communal ideology, this violence is expressed in robberies, homicides, and common crime. In Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, the violence is mostly political, taking the shape or at least the cover of religious fundamentalism. Somehow in Somalia, violence has adopted both criminal and political expressions: We worry about Somali pirates as much as we do about Somali jihadists. (On the link between vulnerable youth and violence, it is telling that the name of the main terrorist organization in Somalia, al-Shabaab, means literally “The Youth”) But there is hope. A couple of decades ago, thousands of unemployed young people joined terrorist organizations in Cambodia, Colombia, and Peru, when these countries were fragile. Since their economies started growing and providing employment, these armies for criminal and political violence have started to fade away. Investing in development, conducting economic reforms, and providing (yes, equal) opportunities is the third component of a winning strategy against terrorism.

A sound military and police strategy is undoubtedly important to counter terrorism. However, it’s not sufficient in the long run. If we want to defeat terrorism permanently and completely, we need to tackle it comprehensively, using political and military intelligence, social integration, and economic development.

For more, please see Keefer, Philip and Norman Loayza, Editors. Terrorism, Economic Development, and Political Openness . Cambridge University Press. 2008.

Global Economy and Development

Mounir Siaplay, Eric Werker

February 3, 2023

Fiona Hill, John Haltiwanger

July 16, 2022

Adedeji Adeniran, Marco Castradori

April 19, 2021

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The 20th Anniversary Of The 9/11 Attacks

The world has changed since 9/11, and so has america's fight against terrorism.

An American flag at ground zero on the evening of Sept. 11, 2001, after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City. Mark Lennihan/AP hide caption

An American flag at ground zero on the evening of Sept. 11, 2001, after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City.

In the fall of 2001, Aaron Zebley was a 31-year-old FBI agent in New York. He had just transferred to a criminal squad after working counterterrorism cases for years.

His first day in the new job was Sept. 11.

"I was literally cleaning the desk, I was like wiping the desk when Flight 11 hit the north tower, and it shook our building," he said. "And I was like, what the heck was that? And later that day, I was transferred back to counterterrorism."

It was a natural move for Zebley. He'd spent the previous three years investigating al-Qaida's bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. And he became a core member of the FBI team leading the investigation into the 9/11 attacks.

It quickly became clear that al-Qaida was responsible.

The hijackers had trained at the group's camps in Afghanistan. They received money and instructions from its leadership. And ultimately, they were sent to the U.S. to carry out al-Qaida's "planes operation."

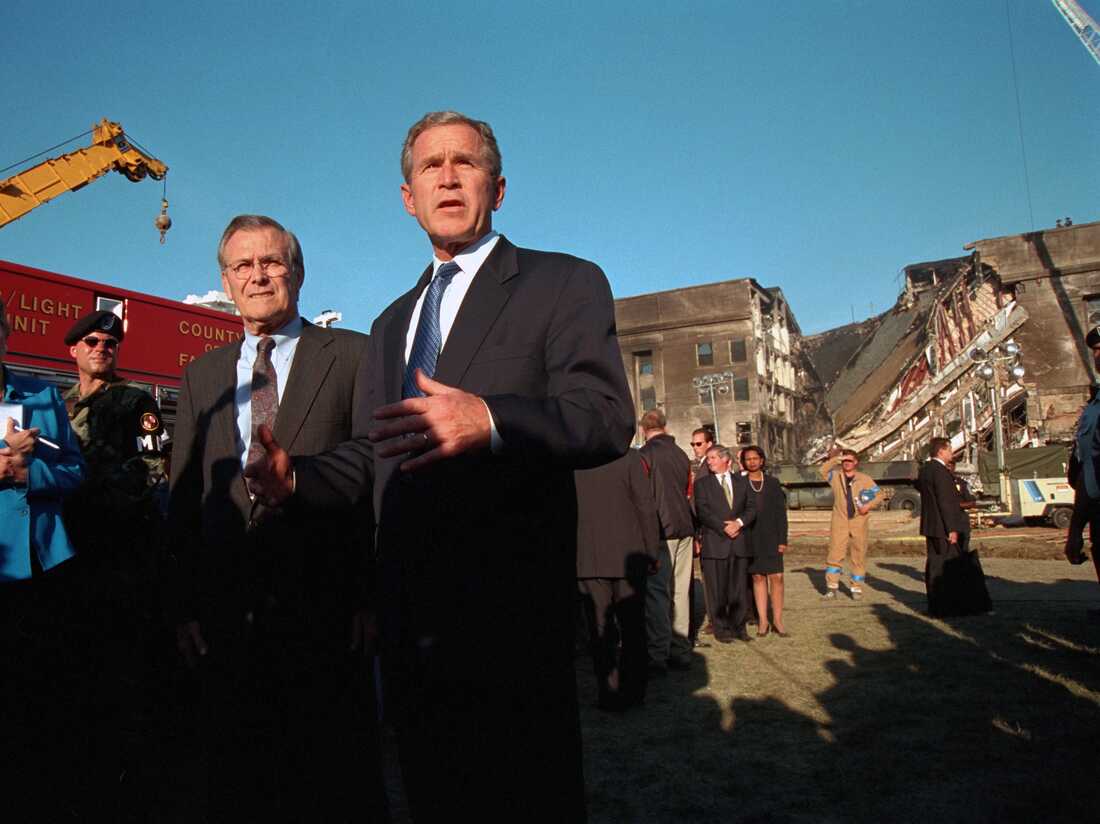

President George W Bush gives an address in front of the damaged Pentagon following the Sept. 11 terrorist attack there as Counselor to the President Karen Hughes and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld stand by. Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images hide caption

President George W Bush gives an address in front of the damaged Pentagon following the Sept. 11 terrorist attack there as Counselor to the President Karen Hughes and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld stand by.

As the nation mourned the nearly 3,000 people who were killed on 9/11, the George W. Bush administration frantically tried to find its footing and prevent what many feared would be a second wave of attacks.

President Bush ordered members of his administration, including top counterterrorism official Richard Clarke, to imagine what the next attack could look like and take steps to prevent it.

"We had so many vulnerabilities in this country," Clarke said.

At the time, officials were worried that al-Qaida could use chemical weapons or radioactive materials, Clarke said, or that the group would target intercity trains or subway systems.

"We had a very long list of things, systems, that were vulnerable because no one in the United States had seriously considered security from terrorist attacks," he said.

That, of course, quickly changed.

Security became paramount.

And over the next two decades, the federal government poured money and resources — some of it, critics say, to no good use — into protecting the U.S. from another terrorist attack, even as the nature of that threat continuously evolved.

The response to keeping the U.S. secure takes shape

The government built out a massive infrastructure, including creating the Department of Homeland Security, all in the name of protecting against terrorist attacks.

The Bush administration also empowered the FBI and its partners at the CIA, National Security Agency and the Pentagon to take the fight to al-Qaida.

The military invaded Afghanistan, which had been a haven for the group. The CIA hunted down al-Qaida operatives around the world and tortured many of them in secret prisons.

The NPR Politics Podcast

Part of flight 93 crashed on my land. i went back to the sacred ground 20 years later.

The Bush administration also launched its ill-fated war in Iraq, which unleashed two decades of bloodletting, shook the Middle East and spawned another generation of terrorists.

On the homefront, FBI Director Robert Mueller shifted some 2,000 agents to counterterrorism work as he tried to transform the FBI from a crime-fighting first organization into a more intelligence-driven one that prioritized combating terrorism and preventing the next attack.

Part of that involved centralizing the bureau's international terrorism investigations at headquarters and making counterterrorism the FBI's top priority.

Chuck Rosenberg, who served as a top aide to Mueller in those early years, said the changes Mueller imposed amounted to a paradigm shift for the bureau.

Robert S. Mueller, then-director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, talks to reporters on Aug. 17, 2006, in Seattle. Ted S. Warren/AP hide caption

Robert S. Mueller, then-director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, talks to reporters on Aug. 17, 2006, in Seattle.

"Mueller, God bless him, couldn't be all that patient about it," Rosenberg said. "It couldn't happen at a normal pace of a traditional cultural change. It had to happen yesterday."

It had to happen "yesterday" because al-Qaida was still plotting. Overseas, its operatives carried out horrific bombings in Bali, Madrid, London and elsewhere.

In the U.S., al-Qaida operative Richard Reid was arrested in December 2001 after trying to blow up a trans-Atlantic flight with a bomb hidden in his shoe. More plots were foiled in the ensuing years, including one targeting the Brooklyn Bridge.

Over time, the FBI and its partners better understood al-Qaida, its hierarchical structure, and how to unravel the various threads of a plot.

That stemmed to large degree, Zebley says, from the U.S. getting better at pulling together various threads of intelligence and by upping the operational tempo.

"If you have a little thread that could potentially tell you about a terrorist plot, not only were we much better at integrating the intelligence, but we did it at a pace that was tenfold what we were doing before," he said.

But critics warned that the government's new anti-terrorism tools were eroding civil liberties, while the American Muslim community felt it was all too often the target of an overzealous FBI.

The digital world helps transform terrorism

By the early days of the Obama administration, the U.S. had to a large extent hardened the homeland against 9/11-style plots. But the terrorism landscape was evolving.

At that time, Zebley was serving as a senior aide to Mueller. Each morning, he would sit in on the FBI director's daily threat briefing.

"I was thinking about al-Qaida for years leading up until that moment," he said. "And now I'm sitting in these morning threat briefings and I'm seeing al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb in North Africa, al-Shabab. ... One of my first thoughts was 'the map looks very different to me now.' "

Robert Mueller (left) and Aaron Zebley testify on Capitol Hill in Washington on July 24, 2019, before the House Intelligence Committee hearing on his report on Russian election interference. Susan Walsh/AP hide caption

Robert Mueller (left) and Aaron Zebley testify on Capitol Hill in Washington on July 24, 2019, before the House Intelligence Committee hearing on his report on Russian election interference.

Ultimately, AQAP — al-Qaida's branch based in Yemen — emerged as a significant threat to the U.S. homeland.

That became clear in November 2009 when U.S. Army Maj. Nidal Hasan shot and killed 13 people at Fort Hood, Texas. A month later, on Christmas Day, a young Nigerian man tried to blow up a passenger jet over Detroit with a bomb hidden in his underwear.

It quickly emerged that both men had been in contact with a senior AQAP figure, an American-born Yemeni cleric named Anwar al-Awlaki.

"My sense when I first heard about him was 'well, he's some charismatic guy, born in the U.S., fluent English speaker and all that. But how big a threat could he be?" said John Pistole, who served as the No. 2 official at the FBI from 2004 until 2010 when he left to lead the Transportation Security Administration.

"I think I failed to recognize and appreciate his ability to influence others to action."

Awlaki used the internet to spread his calls for violence against America, and his lectures and ideas influenced attacks in several countries. Awlaki was killed in a U.S. drone strike in 2011, a move that proved controversial because he was an American citizen.

A few years later, a different terrorist group emerged from the cauldron of Syria and Iraq — the Islamic State, or ISIS, a group that would build on Awlaki's savvy use of the digital world.

"When ISIS came onto the scene, particularly that summer of 2014, with the beheadings and the prolific use of social media, it was off the charts," said Mary McCord, who was a senior national security official at the Justice Department at the time.

Her Brother Died On Flight 93. She Still Sees Him Surfacing In Small Ways

Like al-Qaida more than a decade before, ISIS used its stronghold to plan operations abroad, such as the coordinated attacks in 2015 that killed 130 people in Paris. But it also used social media platforms such as Twitter and Telegram to pump out slickly produced propaganda videos.

"They deployed technology in a much more sophisticated way than we had seen with most other foreign terrorist organizations," McCord said.

ISIS produced materials featuring idyllic scenes of life in the caliphate to entice people to move there. At the same time, the group pushed out a torrent of videos showing horrendous violence that sought to instill fear in ISIS' enemies and to inspire the militants' sympathizers in Europe and the U.S. to conduct attacks where they were.

"The threat was much more horizontal. It was harder to corral," said Chuck Rosenberg, who served as FBI Director James Comey's chief of staff.

People inspired by ISIS could go from watching the group's videos to action relatively quickly without setting off alarms.

"It was clear too that there were going to be attacks we just couldn't stop. Things that went from left of boom to right of boom very quickly. People were more discreet, the thing we used to refer to as lone wolves," Rosenberg said. "A lot of bad things could happen, maybe on a smaller scale, but a lot of bad things could happen more quickly."

Bad things did happen

Europe was hit by a series of deadly one-off attacks. In the U.S., a gunman killed 49 people at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., in 2016. A year later, a man used a truck to plow through a group of cyclists and pedestrians in Manhattan, killing eight people. Both men had been watching ISIS propaganda.

A makeshift memorial stands outside the Tree of Life Synagogue in the aftermath of a deadly shooting in Pittsburgh in 2018. Matt Rourke/AP hide caption

A makeshift memorial stands outside the Tree of Life Synagogue in the aftermath of a deadly shooting in Pittsburgh in 2018.

The group's allure waned after a global coalition led by the U.S. managed to retake all the territory that ISIS once claimed.

By then, America's most lethal terror threat already stemmed not from foreign terror groups, but from the country's own domestic extremists.

For nearly two decades, the FBI had prioritized the fight against international terrorists. But in early 2020, FBI Director Christopher Wray said that had changed.

"We elevated to the top-level priority racially motivated violent extremism so it's on the same footing in terms of our national threat banding as ISISI and homegrown violent extremism," he testified before Congress.

The move came in the wake of a series of high-profile attacks by people espousing white supremacist views in Charlottesville, Va., Pittsburgh, Pa., Poway, Calif., and El Paso, Texas.

At the same time, anti-government extremist groups and conspiracy theories like QAnon were attracting more adherents.

Those various movements converged in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6, 2021, in the storming of the U.S. Capitol as Congress was certifying Joe Biden's presidential win.

Rioters climb the west wall of the the U.S. Capitol in Washington on Jan. 6. Jose Luis Magana/AP hide caption

Rioters climb the west wall of the the U.S. Capitol in Washington on Jan. 6.

The FBI has since launched a massive investigation into the assault, and Wray has bluntly described the Capitol riot as "domestic terrorism."

McCord, who is now the executive director at the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at the Georgetown University Law Center, says domestic extremist groups are using many of the same tools that foreign groups have for years.

"You see that in the use of social media for the same kind of things: to recruit, to propagandize, to plot, and to fundraise," she said.

The Capitol riot has put a spotlight on far-right extremism in a way the issue has never received in the past two decades, including in the media and the highest levels of the U.S. government.

President Biden, for one, has called political extremism and domestic terrorism a looming threat to the country that must be defeated, and he has made combating the threat a priority for his administration.

- terrorist attacks

- FBI Director Robert Mueller

- President George W. Bush

- Sept. 11 attacks

Terrorism Essay for Students and Teacher

500+ words essay on terrorism essay.

Terrorism is an act, which aims to create fear among ordinary people by illegal means. It is a threat to humanity. It includes person or group spreading violence, riots, burglaries, rapes, kidnappings, fighting, bombings, etc. Terrorism is an act of cowardice. Also, terrorism has nothing to do with religion. A terrorist is only a terrorist, not a Hindu or a Muslim.

Types of Terrorism

Terrorism is of two kinds, one is political terrorism which creates panic on a large scale and another one is criminal terrorism which deals in kidnapping to take ransom money. Political terrorism is much more crucial than criminal terrorism because it is done by well-trained persons. It thus becomes difficult for law enforcing agencies to arrest them in time.

Terrorism spread at the national level as well as at international level. Regional terrorism is the most violent among all. Because the terrorists think that dying as a terrorist is sacred and holy, and thus they are willing to do anything. All these terrorist groups are made with different purposes.

Causes of Terrorism

There are some main causes of terrorism development or production of large quantities of machine guns, atomic bombs, hydrogen bombs, nuclear weapons, missiles, etc. rapid population growth, Politics, Social, Economic problems, dissatisfaction of people with the country’s system, lack of education, corruption, racism, economic inequality, linguistic differences, all these are the major elements of terrorism, and terrorism flourishes after them. People use terrorism as a weapon to prove and justify their point of view. The riots among Hindus and Muslims are the most famous but there is a difference between caste and terrorism.

The Effects Of Terrorism

Terrorism spreads fear in people, people living in the country feel insecure because of terrorism. Due to terrorist attacks, millions of goods are destroyed, the lives of thousands of innocent people are lost, animals are also killed. Disbelief in humanity raises after seeing a terrorist activity, this gives birth to another terrorist. There exist different types of terrorism in different parts of the country and abroad.

Today, terrorism is not only the problem of India, but in our neighboring country also, and governments across the world are making a lot of effort to deal with it. Attack on world trade center on September 11, 2001, is considered the largest terrorist attack in the world. Osama bin Laden attacked the tallest building in the world’s most powerful country, causing millions of casualties and death of thousands of people.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Terrorist Attacks in India

India has suffered several terrorist attacks which created fear among the public and caused huge destruction. Here are some of the major terrorist attacks that hit India in the last few years: 1991 – Punjab Killings, 1993 – Bombay Bomb Blasts, RSS Bombing in Chennai, 2000 – Church Bombing, Red Fort Terrorist Attack,2001- Indian Parliament Attack, 2002 – Mumbai Bus Bombing, Attack on Akshardham Temple, 2003 – Mumbai Bombing, 2004 – Dhemaji School Bombing in Assam,2005 – Delhi Bombings, Indian Institute of Science Shooting, 2006 – Varanasi Bombings, Mumbai Train Bombings, Malegaon Bombings, 2007 – Samjhauta Express Bombings, Mecca Masjid Bombing, Hyderabad Bombing, Ajmer Dargah Bombing, 2008 – Jaipur Bombings, Bangalore Serial Blasts, Ahmedabad Bombings, Delhi Bombings, Mumbai Attacks, 2010 – Pune Bombing, Varanasi Bombing.

The recent ones include 2011 – Mumbai Bombing, Delhi Bombing, 2012 – Pune Bombing, 2013 – Hyderabad Blasts, Srinagar Attack, Bodh Gaya Bombings, Patna Bombings, 2014 – Chhattisgarh Attack, Jharkhand Blast, Chennai Train Bombing, Assam Violence, Church Street Bomb Blast, Bangalore, 2015 – Jammu Attack, Gurdaspur Attack, Pathankot Attack, 2016 – Uri Attack, Baramulla Attack, 2017 – Bhopal Ujjain Passenger Train Bombing, Amarnath Yatra Attack, 2018 Sukma Attack, 2019- Pulwama attack.

Agencies fighting Terrorism in India

Many police, intelligence and military organizations in India have formed special agencies to fight terrorism in the country. Major agencies which fight against terrorism in India are Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS), Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), National Investigation Agency (NIA).

Terrorism has become a global threat which needs to be controlled from the initial level. Terrorism cannot be controlled by the law enforcing agencies alone. The people in the world will also have to unite in order to face this growing threat of terrorism.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

Securing our Future: A Decade of Counter-terrorism Strategies

About the author.

From No. 2, Vol. XLVIII, “Pursuing Peace: Commemorating Dag Hammarskjöld”, 2011

T errorism did not begin on 11 September 2001, but that terrible day did change the world. The attacks on the United States that claimed the lives of nearly three thousand innocent people showed us that terrorism had morphed into a global phenomenon that could cause massive pain and destruction anywhere. The magnitude of the attacks meant that no one could stand on the sidelines anymore. The fight had become global because the impact of terrorism was being felt everywhere.

The human values we share and work to uphold are derided by terrorists. The promotion of peace, equality, tolerance, and dignity for all are universal values that transcend our national differences. They are the glue that binds us together. United as nations and people of the world, we must come together to protect our common humanity. The global framework against terrorism The United Nations was engaged with the issue of terrorism long before that calamitous September morning ten years ago. For decades, the Organization has brought the international community together to condemn terrorist acts and developed the international legal framework to enable states to fight the threat collectively. Sixteen international treaties have been negotiated at the United Nations and related forums that address issues as diverse as the hijacking of planes, the taking of hostages, the financing of terrorism, the marking of explosives, and the threat of nuclear terrorism.

Additionally, in response to deadly attacks in East Africa and the deteriorating situation in Afghanistan, the Security Council, in 1999, decided to impose sanctions on the Taliban and, later, on Al-Qaeda. The Council created a list of individuals and entities associated with these organizations that are subject to a travel ban, assets freeze, and arms embargo.

Shortly after 11 September 2001, the Security Council took even more forthright action, based on its realization that terrorism would continue to pose a serious threat to international peace and security in the new millennium. It adopted a far-reaching resolution charting the way forward in the fight against terrorism. That resolution requires all UN Member States, separately and collectively, to deny terrorists safe haven and financial support and to cooperate in bringing them to justice.

Subsequent Security Council resolutions paid increasing attention to taking preventive measures noting, for example, that extremists were using the Internet to recruit people and incite terrorist acts. The Council began to consistently emphasize the need for counter-terrorism measures to be in line with states' international legal obligations, including human rights law. It also considered it vital to ensure that non-state actors, such as terrorist groups, would not have access to weapons of mass destruction. Meanwhile, in 2006, the General Assembly adopted the United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, in which it stressed the importance of addressing the issues that can give rise to terrorism. These include unresolved conflicts, dehumanization of victims, discrimination, violations of human rights, and lack of good governance. A comprehensive response to terrorism In the past decade, we at the United Nations have built on previous experience and are helping states adapt to an evolving threat that often involves new technologies. Although I believe we are heading in the right direction, much progress still needs to be made at the national, regional, and international levels.

Individual countries have made big strides, but success is measured in relative terms and major disparities persist. While some countries can spend billions of dollars on countering terrorism, others struggle to put in place even the basic measures needed to protect their borders and bring terrorists to justice. When a large proportion of a country's population lives in poverty, it is no surprise that they put scarce resources into development rather than counter-terrorism. We understand that, and often suggest approaches that have the dual benefit of protecting the country's economic and developmental interests while enhancing its security.

Frankly, preventing terrorist attacks is a challenge for everyone, even for countries that are richly endowed with resources and skilled personnel. For most nations, realistically, the implementation of the long list of measures envisaged by the Security Council resolutions and the Global Strategy is going to be patchy at best. The task is daunting: securing borders, tightening financial controls, strengthening the role of the police, improving criminal justice systems, and providing mutual legal assistance to other countries trying to convict terrorists in their courts. This is a step-by-step process that might begin with Governments ratifying the relevant conventions and adopting stronger terrorism-related laws. However, they cannot stop there.

The devil is often in the details when dealing with an issue as complex as this one. Take, for example, airport security. In many airports, security is tighter than ever, often to the annoyance of travelers who feel they are subjected to overly intrusive measures. The 9/11 terrorists, the "shoe bomber," and the "underwear bomber" all prompted reviews of security procedures that resulted in new approaches. As we introduce the latest ones and train staff on their use, we must always be aware that Al-Qaeda and other groups are probably working on new methods of evasion. All this relies on information and technology, both often in short supply in parts of the world where it can take weeks to repair a broken X-ray machine.

Countless men and women are on the beat every day all over the world, determined to prevent terrorists and other criminals from carrying out their plans. Think of border guards patrolling long and remote frontiers in inhospitable terrain, police officers following leads that span multiple countries, prosecutors combing through endless piles of evidence. Knowing that proper training, better equipment, and access to more information would help them immeasurably, we work towards bringing these tools to them.

When a country's defences are breached and a terrorist attack succeeds, we are immediately reminded of the real cost of this scourge, notably human pain, loss, and suffering. The images of the latest bombed vehicle or building flickering on our television screens may fade in our memories, but the pain of survivors, families of victims, and affected communities does not go away so easily. These people must not be forgotten, and we in the United Nations should continue to advocate for their interests and dignity. Their stories speak loudly for humanity and justice, and are an important part of countering terrorist propaganda.

It is clear that Governments alone cannot deal with this challenge. Countries with truly effective counter-terrorism strategies recognize the value of involving local communities, the private sector, the media, and other groups in society. They also encourage the exchange of intelligence, information, and expertise between national agencies and across borders. The broader the response, the more effective it is likely to be. The road ahead Over the past ten years, we have seen states try a variety of approaches to reduce the chance of terrorists succeeding. The United Nations has provided guidance and support in their endeavors, focusing on areas where we have a comparative advantage.

As a leader in the global fight against terrorism, our Organization will continue to press Governments to adopt comprehensive national strategies that balance hard-end security measures with social, economic, and community-driven policies that are grounded in the rule of law. The truth is that measures that try to take shortcuts or are not respectful of international human rights norms can actually undermine the collective effort by bolstering resentment in parts of the community and providing grist for terrorist groups' propaganda mills.

In the coming years, we will do more to help countries improve their internal coordination and their cooperation with neighbours. But breaking down institutional barriers and building trust between competing agencies as well as across borders takes time. The regional and global events we organize aim to facilitate those processes, giving professionals an opportunity to meet face to face and brainstorm on good practices. Once back home, they can implement the lessons learned and call on their international network for support.

We work with bilateral and multilateral agencies that can share their expertise with countries in need of technical assistance. Services available include drafting national laws, training prosecutors and judges, and linking national databases to border posts. The United Nations can also offer support with, for example, education programmes aimed at building tolerance in communities and development projects directed at improving governance.

Our bird's eye view has allowed us to follow counter-terrorism developments across the globe, learning along the way what works and what does not. And when I consider what we have already achieved, I am optimistic about what we can accomplish together as nations and people of the world over the next decade. Working as one, we can significantly reduce the number of attacks and victims and, hopefully, one day eliminate the terrorist threat completely.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Thirty Years On, Leaders Need to Recommit to the International Conference on Population and Development Agenda

With the gains from the Cairo conference now in peril, the population and development framework is more relevant than ever. At the end of April 2024, countries will convene to review the progress made on the ICPD agenda during the annual session of the Commission on Population and Development.

The LDC Future Forum: Accelerating the Attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals in the Least Developed Countries

The desired outcome of the LDC Future Forums is the dissemination of practical and evidence-based case studies, solutions and policy recommendations for achieving sustainable development.

From Local Moments to Global Movement: Reparation Mechanisms and a Development Framework

For two centuries, emancipated Black people have been calling for reparations for the crimes committed against them.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

From Knowledge to Wisdom

Disastrous War against Terrorism