International Journal of Multicultural Education

About the Journal

International Journal of Multicultural Education (IJME) is a free , peer-reviewed open-access journal for scholars, practitioners, and students of multicultural education. Committed to promoting educational equity for diverse students, cross-cultural understanding, and global justice for marginalized people in all levels of education, including leadership and policies, IJME publishes three types of articles: (1) qualitative research studies that explicitly address multicultural educational issues; (2) conceptual and theoretical articles, typically grounded on in-depth literature review, which advance theories and scholarship of multicultural education; and (3) praxis articles that discuss successful multicultural education practices grounded on sound theories and literature. We encourage submissions resulted from meaningful and ethical collaboration among international scholars and practitioners. Submissions that advance from prescreening will be subject to originality-testing and double-blind peer review.

IJME is included in several international indexes and databases such as ESCI (Clarivate Analytics), Scopus, ERIC, Ebscohost, and Google Scholar. Our ISSN is 1934-5267.

IJME is ranked by the Scopus citation database as having a site score of 2.5 and a SCImago Journal Rank measure of 4.01. Scopus ranks IJME in the 90th percentile of journals in Cultural Studies and in the 57th percentile in Education (2023). These measures are available at Scopus.com . IJME is included in the Directory of Open Access Journals ( DOAJ ). T he journal has a readership of more than 23,000 and an acceptance rate of 7-8%.

IJME provides open access to its content on the principle that making research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge and equitable educational practices. All published articles are made available to readers under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license. Upon publication, users have immediate free access to IJME articles.

The institutional sponsors and the voluntary service of international editors and reviewers have enabled IJME to provide the open-access content to the global community with no subscription fees to readers and no article processing fees to authors.

**********************************************************

Announcements

4-trans special issue.

In alignment with IJME’s ultimate goals of promoting cultural understanding and social justice amongst multicultural populations, this special issue seeks manuscripts that address recent approaches related to transnationalism, transculturalism, translanguaging and transdisciplinarity, (the “4 trans”) and contribute to advancing towards a reconceptualization of bilingual and multilingual teacher education. By centering on the “4 trans”, we highlight the centrality of these dimensions that intersect explicitly or implicitly in the way we view, define, and prepare bilingual and multilingual teachers. In particular, we seek manuscripts that aim to question monolithic approaches to teacher preparation that perpetuate restrictive, monoglossic, hegemonic, and colonizing/oppressive views of teachers and teacher education (Zúñiga et al., 2023). Our special issue, in this way, seeks to summon the scholarship of international researchers and practitioners who engage in critical, theoretical, and practical explorations of the “4 trans” dimensions in teacher education.

Current Issue

Articles (peer-reviewed), “ready for change”: pre-service teacher perspectives on diversity preparation in rural appalachia, weathering the storm how mothers with refugee backgrounds helped their children with school during the covid-19 pandemic, experiences of preservice teachers of color at a predominantly white institution, from reading to restoration using book clubs and critical dialogue to challenge, critique, and change us and our work.

Please be aware of a fraudulent version of IJME that was created by nefarious actors. Their website is https://ijmejournal.org/ijme/index.php/ijme.html (no "-" between "ijme" and "journal"). They are scammers who have copied IJME's open access web design and pretend to be us. T hey charge for printing articles and are not indexed in Scopus or any database . Please do not give them your money. The real IJME (this site) is free and our publications are peer-reviewed and indexed in many academic data bases, including Scopus, where IJME is ranked in the 90th percentile of journals in Cultural Studies and in the 57th percentile in Education (2023). These measures are available at Scopus.com . Please note that the real IJME is included in the Directory of Open Access Journals ( DOAJ ).

Developed By

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Make a Submission

Part of the PKP Publishing Services Network

announcements

IJME is a peer-reviewed, open access journal that is FREE to authors and readers.

Advertisement

Effects of multicultural education on student engagement in low- and high-concentration classrooms: the mediating role of student relationships

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 17 March 2023

- Volume 26 , pages 951–975, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ceren S. Abacioglu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9931-1401 1 ,

- Sacha Epskamp 2 ,

- Agneta H. Fischer 1 &

- Monique Volman 3

20k Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Having positive and meaningful social connections is one of the basic psychological needs of students. The satisfaction of this need is directly related to students’ engagement—a robust predictor of educational achievement. However, schools continue to be sites of interethnic tension and the educational achievement of ethnically-minoritized students still lags behind that of their ethnic majority peers. The goal of the present study was to provide a quantitative account of the current segregated learning environments in terms of multicultural curriculum and instruction, as well as their possible impact on student outcomes that can mitigate these challenges. Drawing upon Self-Determination Theory, we investigated the extent to which the use of multicultural practices can improve students’ engagement and whether this relationship is mediated by students’ peer relationships. With data from 34 upper primary school classroom teachers and their 708 students, our multigroup analysis using structural equation modeling indicated that, in classrooms with a low (compared with high) minoritized student concentration, peer relationships can mediate the positive as well as negative effects of different dimensions of multicultural education on student engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Cultural Significance of “We-Ness”: Motivationally Influential Practices Rooted in a Scholarly Agenda on Black Education

The Intersection of the Peer Ecology and Teacher Practices for Student Motivation in the Classroom

Discrimination and academic (dis)engagement of ethnic-racial minority students: a social identity threat perspective

Explore related subjects.

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Having positive and meaningful social connections (i.e., relatedness ) is one of the basic psychological needs of students. The satisfaction of this need is directly related to students’ intrinsic motivation and engagement—a strong predictor of positive academic outcomes (see Self-Determination Theory, SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985 ). Present educational institutions, however, are struggling to create learning environments in which all students experience equal levels of opportunities, representation, and belongingness (Huijnk et al., 2016 ). Interethnic tensions between students and their peers and teachers, and structural barriers such as mainstream education that do not relate to minoritized students’ personal experiences and frames of reference (Stevens et al., 2017a , b ), seem to be at the core of this challenge.

These challenges are especially costly for the minoritized students that are more disadvantaged in the societal ethnic hierarchy (Thijssen et al., 2021 ). They indicate feeling less and less at home, experiencing high levels of discrimination and low levels of acceptance, and feeling more pessimistic about having equal representation and opportunities in the Netherlands over the last decade, where the current study was conducted (Huijnk et al., 2016 ). Accordingly, they perform lower on academic indicators such as standardized test scores at the end of primary school and higher drop-out rates compared with their majority group peers (CBS, 2020 ).

One potential way to tackle this challenge is to incorporate into education more multicultural practices that have the potential to benefit all students. These practices are designed to mitigate inequality in education opportunities and improve intergroup relationships (Banks, 1995 ). Despite an increased interest in multicultural classrooms, it is noteworthy that very little is empirically known about the influence of different aspects of multicultural practices on the desired student outcomes. Yet, the growing demand for diversity research indicates a necessity to provide more-detailed accounts of learning environments in how they accommodate the diversity of their students and what this means for students’ social and academic functioning (Alt, 2017 ).

Drawing upon SDT, the current study examined whether different aspects of multicultural practices can be useful in increasing students’ engagement—an important predictor of positive academic outcomes (Fredricks et al., 2019 ), through its influence on students’ peer relationships and hence relatedness . As Dutch schools are highly segregated along ethnic lines (Huilla et al., 2022 ), we tested the proposed relationships in learning environments that afford different conditions for peer relationships, namely, classrooms with low and high ethnically-minoritized student concentrations.

The learning environment

The Social Identity Approach (Abrams & Hogg, 1990 ; Reicher et al., 2010 ), which includes the Social Identity and Self-Categorization Theories (Tajfel & Turner, 1979 ; Turner et al., 1987 ), contends that children learn about socially-significant group distinctions and define themselves and others in terms of their group memberships from an early age. This act of self-categorization into a group offers familiarity and pertinent cultural information about oneself and one’s group and serves as the starting point for understanding intergroup dynamics. The resulting ‘us’ (the ingroup) and ‘them’ (the outgroup) division is a significant source of influence on children’s attitudes and behavior toward their ingroup and outgroup (Liberman et al., 2017 ; Rhodes & Baron, 2019 ), and can result in prejudices between the majority and minoritized groups so that the ingroup is favored and outgroup members are occasionally disliked and rejected.

The learning environment is one element that can augment or counteract prejudice between groups. Cortés ( 2000 ) calls the sociocultural elements that affect and mould students’ attitudes toward various ethnic and racial groups the ‘societal curriculum’. Indeed, through both a manifest and a hidden curriculum, learning environments frequently promote and uphold the unfavorable stereotypes about ethnic groups that young people learn about in the wider world.

Lesson plans, textbooks, bulletin boards, curriculum guides, and other observable environmental elements make up the manifest curriculum . These can make remarks about the school's beliefs regarding ethnic diversity because the ethnic groups that appear in textbooks and other instructional materials tell students which groups the school thinks are significant or unimportant. The curriculum that all students acquire, but no teacher openly teaches, is known as the hidden curriculum . This curriculum expresses many of the important values of the school regarding cultural diversity through the teacher–student interactions, learning characteristics, language, motivational systems, and culture that are fostered by the school (Banks, 2004a , 2004b ).

In Dutch educational institutions, the curriculum, materials, and instruction tend to be primarily from the perspective of the dominant group, resulting in less relatable educational content and pedagogical practices that do not support ‘alternative’ ways of learning. As a result, minoritized groups’ histories and cultures are usually added as a mere side note to the regular curriculum and mentioning of social biases is kept to a minimum, thereby perpetuating the acceptance of existing inequalities and not providing equitable opportunities for development.

For instance, when Weiner ( 2018 ) looked at the representation of immigrants, multiculturalism, and tolerance in all Dutch primary school history textbooks released between 1980 and 2011, 81.3 percent of the 203 textbooks, workbooks, and activity books in 18 series produced since 1980 completely exclude minoritized cultures and identities. When they are discussed in textbooks, they are separated from the rest of Dutch society and placed in their own distinct sections. They are portrayed as culturally alien outsiders from underdeveloped, impoverished, and violent cultures who create issues for the Dutch community that kindly welcomes them.

These biases, in addition, are often mirrored in interpersonal interactions between students and teachers, and between peers (Thijs & Verkuyten, 2014 ). Weiner ( 2016 ) spent two days a week for three months in a diverse eighth group (equal to the sixth grade in the US) classroom in Amsterdam North, a district chosen for its ethnic and racial variety and relative socioeconomic homogeneity. According to Weiner's ( 2016 ) research, the White teacher reified cultural norms and discourses prevalent in Dutch culture, and positioned Dutch students without a migration background as superior and normative, even when they engaged in disruptive activities while placing students with a migration background in an inferior position in the country's ethnic and racial hierarchy.

Peer relationships and student engagement

Such cultural discontinuity between majority and minoritized students can result in difficulties considering the experiences and perspectives of the non-dominant group members (Dovidio et al., 2017 ) or name-calling from peers and exclusion from peer groups (Huijnk et al., 2016 ; Thijs & Verkuyten, 2014 ). Against this background, children rarely have friendships and casual contact with peers of a different ethnic background in multicultural Dutch classrooms (de Bruijn et al., 2020 ; Fortuin et al., 2014 ).

SDT posits that learning environments that feature conditions that satisfy students’ feelings of relatedness can stimulate greater student engagement—the extent to which a student is actively involved in learning activities (Skinner et al., 2016 ). Lower levels of feelings of relatedness, on the other hand, can inhibit learning motivation and engagement (Fredricks et al., 2019 ), which is manifested in multiple dimensions.

The behavioral dimension of engagement includes students’ efforts in initiating learning activities, and attention, concentration, persistence, and involvement during these activities. The emotional dimension of engagement includes enthusiasm, interest, enjoyment, and satisfaction states during learning activities. The cognitive dimension of engagement includes goal strivings, mastery orientation, self-regulation, and the use of coping strategies preceding and during learning activities. Some studies do not distinguish between cognitive and emotive components. Despite the fact that we frequently distinguish ‘rational thought’ from ‘emotion,’ both factors work together to influence our actions. Thus, some researchers combine the notions into a single term known as ‘cognitive-affective states’ rather than separating them (Baker et al., 2010 ). On a similar account, to the best of our knowledge, the measures that assess students’ engagement in primary-school-aged children do not separate the emotional and cognitive dimensions.

Previous research shows that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs positively influences different dimensions of student engagement to different extents (Dincer et al., 2019 ). These dimensions capture related but independently emerging factors that influence a student's active involvement in school (Salmela‐Aro et al., 2021 ), and they can have varying positive effects on academic outcomes based on the dimension (Lei et al., 2018 ). Therefore, we focused on the emotional and behavioral aspects of engagement separately, but without an isolated cognitive dimension, and consider multicultural education as a tool to improve students’ engagement through its influence on students’ peer relationships, hence relatedness.

- Multicultural education

Concerned with critically examining inequitable structures, providing students with equal opportunities, understanding cultural diversity, and incorporating multiple perspectives into education (Nieto, 2004 ), multicultural education offers a set of practices that are designed to enhance intergroup relations and reach similar educational achievement levels by considering the needs of students from all backgrounds (Klein, 2012 ). Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985 ; Reeve, 2002 ) connects these two outcomes together through the relationship between satisfaction of the basic psychological need for relatedness and student engagement. We, therefore, examine the influence of multicultural education on students’ peer relationships (as a proxy to relatedness) and engagement using the SDT framework.

Banks ( 2004a , 2004b ) provides a detailed conceptualization of multicultural education that includes five distinct but highly interrelated dimensions. We used these dimensions to investigate the relationships between multicultural education, peer relationships, and engagement. In his conceptualization, teachers should employ content integration from a variety of cultures in what they teach, reflecting and representing the diversity of their students through texts, histories, values, beliefs, and varying perspectives from different cultures. Moreover, teachers should increase their students’ awareness of the knowledge construction process and help students to be critical about who the knowledge serves and from whose perspective it was constructed (e.g., cultural references, biases). Next, teachers should aim for prejudice reduction by modifying their students’ attitudes through teaching methods, materials, and dialogue to decrease negative and improve positive intergroup relations by actively counteracting social biases (i.e., prejudice, stereotyping, discrimination). Further, teachers should aim for an empowering school culture and social structure , by examining disproportionality in attendance and achievement between groups in various aspects of school (e.g., to giftedness programs). Lastly, teachers should strive for equity pedagogy (i.e., equity in how they teach, by modifying their teaching to include various teaching and assessment styles to facilitate the learning and academic achievement of all students). This requires avoiding standardized, one-size-fits-all approaches to teaching and learning, relating content to students’ lives, and creating opportunities for them to engage with learning in various forms (e.g., cooperative learning, problem-based learning, role-playing, simulations).

Therefore, multicultural education, through promoting student representation and involvement in the educational curriculum, instruction, and materials, improves students’ abilities to understand and interpret the perspectives, worldviews, frames of references, and values and behaviors that are normative to ethnic and racial groups other than their own (Banks, 2004a , 2004b ). It integrates content from a variety of cultures into instruction and provides opportunities to critically examine content from a variety of perspectives. Thereby, it provides students with an opportunity to express their voices and makes teaching relevant and meaningful for all students (Banks, 2004a , 2004b ).

Such teaching activities are more likely to be engaging for students because they acknowledge students’ experiences and emotions related to a topic (Skinner et al., 2016 ). They tend to include content that deals with issues and problems that relate to students’ worlds, including their norms, values, identities, and struggles (Banks, 2004a , 2004b ; Gay, 2013 ). A recent path analysis study, conducted with 110 ethnically-minoritized middle-school students from the United States, for instance, examined whether culturally-responsive teaching and teacher expectations had positive associations with Latinx students’ academic outcomes (Garcia & Chun, 2016 ). They found that, when teachers try to find out what students find interesting and what they already know, build on that knowledge and use it to exemplify new teaching content (i.e., content integration ) by using various teaching techniques (i.e., equity pedagogy ), and have high expectations of their students, they are more likely to help students to engage in learning and to have more positive beliefs about their achievement outcomes.

Moreover, students infer whose culture and history are worth studying and whose experiences are worth mentioning from the content studied in their classrooms. When the content includes multiple voices and perspectives as to how life can be experienced and understood, it not only makes the content more relevant for more students but also promotes positive ethnic identity and gives ‘permission’ to students to be their authentic selves and to accept each other as they are (Piper, 2019 ).

For instance, in a study conducted with children between the age of 6 and 11 years (Hughes et al., 2007 ), researchers compared pretest and posttest results of prejudiced attitudes towards African Americans in an experimental and in a control group. The experimental group learned about acclaimed African American leaders, together with discussion of examples of their experiences with discrimination (i.e., prejudice reduction ). In contrast, the control group only received biographical information about the leaders without any discussions on racism. Compared with the control group, European American children in the experimental group showed lower degrees of prejudice towards African Americans, and both African American and European American children displayed greater valuing of ‘interracial’ fairness.

Multicultural education not only has the potential to improve students’ engagement through offering content that is relevant to students’ lives, but it also has the potential to increase student engagement through improved understanding, positive peer relationships, and thus improved feelings of relatedness.

(Un)Equal status environments

It is evident from previous research that the learning environment can help students to become less prejudiced and acquire more democratic attitudes, values, and behaviours—fostering dialogue about issues related to prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination, and creating an appreciation of differences as a resource for social and academic development (Banks, 2004a , 2004b ).

However, decades of research on Intergroup Contact Theory (Allport, 1954 ; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006 ) suggests that instruction must be designed especially for this purpose and must take place in a learning environment that has several identifiable characteristics, including equal status between groups. Similarly, the Social Identity Approach (Abrams & Hogg, 1990 ; Reicher et al., 2010 ) stresses that psychological processes are influenced by the local and larger sociocultural context rather than general ingroup favouritism (Verkuyten, 2022 ).

Thus, depending on the characteristics of the learning environment, one’s group membership can become salient and relevant. Importantly, in situations in which the perceived status of the groups is unequal, which can be influenced both by the ethnic group hierarchies and the ethnic composition of the environment (Olonisakin, 2021 ; Radke et al., 2017 ), disadvantaged groups might try to change the status quo, whereas dominant groups might legitimize inequality in order to defend their position as the dominant group (Pehrson et al., 2017 ). Evidence suggests that disadvantaged groups could attempt to alter unstable status through higher levels of ingroup favouritism in order to make up for perceived disparity and/or to compete for future status and attain equality with the dominant outgroup (Rubin et al., 2014 ). Similarly, in environments where the dominant group members are in the numerical majority, they can develop in-group favoritism if their perceived representativeness of the larger social group is challenged (Mummendey & Wenzel, 1999 ; Steffens et al., 2017 ; Wenzel et al., 2007 ) by, for example, bringing out the diversity of perspectives and values. In such environments, dominant group members are more likely to see themselves as highly representative of the larger group (e.g., Dutch people in the Netherlands) compared with environments in which they are likely to see themselves as just another ethnic group among many others and therefore are in the numerical minority (e.g., Dutch people in Europe).

We investigated the role of multicultural education practices on students’ peer relationships and engagement in learning environments that differ in their conduciveness to equal status based on the demographic complexion of the classrooms. In doing so, we examined the role of both the pedagogical elements of the learning environment (i.e., how hidden and manifest curricula are enacted) and the structural elements of the learning environment (i.e., the degree to which the classrooms afford contact between students from different backgrounds) in students’ social and academic functioning. Specifically, in the Netherlands, schools are segregated along ethnic lines. Schools where 70% or more children come from migrant backgrounds, and schools where 70% or more children have no migration history, are accepted as highly concentrated with minoritized and majority group students, respectively (Wielzen & van Dijk-Groeneboer, 2018 ). In the current study, therefore, we defined classrooms with ethnically minoritized student concentration equal to or less than 30% as low-concentration, 30–70% as mixed , and 70% or higher as high-concentration classrooms. To reach comparable sample sizes, we combined the mixed and high -concentration classrooms.

Current study

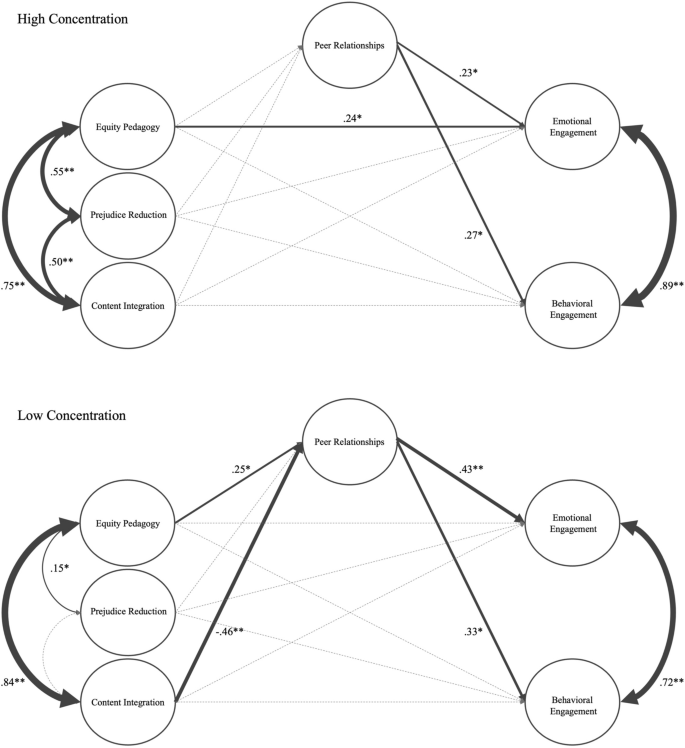

Our hypothesized model depicted in Fig. 1 is tested low- and high-concentration classrooms. It presents both a direct relationship between multicultural practices and student engagement because we can expect multicultural education to provide education that connects to students’ lives and hence is more relevant and engaging, and an indirect relationship that is mediated by students’ peer relationships (relatedness) as we can expect multicultural education to improve understanding and rapport between members of different groups.

Structural equation models. Note. The solid lines represent the significant relationships that vary in thickness depending on their strength. The standardized regression coefficients of the significant relationships are indicated in the figures. The observed indicators for the latent student variables are omitted from the graph for clarity. * = p < .05, ** = p < .01

A body of student- and teacher-level control variables also was incorporated into our models. Previous research has shown a normative steady decline in engagement throughout school years, and more so for male students (Wigfield et al., 2015 ). Moreover, multicultural education has been suggested as having positive effects on majority and minoritized students through varying mechanisms (Abacioglu et al., 2019 ). However, we did not investigate these mechanisms in the scope of our study. Therefore, student-level control variables included students, age, gender, and ethnic background.

Moreover, teachers from minoritized backgrounds themselves have been suggested to relate to the cultural discontinuity that students might be experiencing and thus practise multicultural education more frequently (Rychly & Graves, 2012 ) and effectively (Bingham & Okagaki, 2012 ). Similarly, because women have been found to be more sensitive to people’s distress (Christov-Moore et al., 2014 ), female teachers might be more vigilant about challenges that students experience and might be more likely to engage in practices such as prejudice reduction (Banks, 2004a , 2004b ). Additionally, teachers might learn more about different cultures, value differences in backgrounds, and develop more-positive interethnic and intercultural attitudes with increasing years of teaching experience and exposure to different cultures (Dovidio et al., 2017 ). Lastly, there is a distinction made between public and so-called ‘denominational’ schools in the Netherlands. Although both types of schools are publicly funded, the latter teach on the basis of religion, a specific philosophy or vision of education, whereas the former do not, which could affect the degree to which teachers employ multicultural practices. Therefore, we included teachers’ gender, ethnicity, teaching experience, and whether they teach in public or denominational schools as teacher-level control variables in our models.

Participants

Participants were recruited from schools that collaborate with the Primary Teacher Education Program of [removed for peer review]. In total, data were gathered from 34 upper primary school classroom teachers and their 708 students. We removed one student for missing more than 75% of the responses. Footnote 1 The remaining sample included teachers with a mean age of 38.87 ( SD = 11.20), who were predominantly female (64%) and without a migration history (82.7%) based on whether either of their parents had a migration history, or who identified with an ethnic identity other than or in addition to Dutch. Teachers had an average of 12.20 years of teaching experience ( SD = 9.36). Additionally, about half of the teachers were appointed in denominational schools (47.9%).

Participating students’ ages ranged from 7–13 ( M age = 10.66, SD = 1.11). About half of the students were female (52.6%). Based on whether either of their parents had a migration history, or whether they identified with an ethnic identity other than or in addition to Dutch, about 45% of students were identified as belonging to a group with a migration history.

Teacher-level measures

Teachers responded to 13 statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale, about their practices in student assessment, curriculum and instruction, classroom management, and cultural enrichment. The items were based on the Culturally Responsive Teaching Self-Efficacy Scale (Siwatu, 2007 ), but were shortened and adapted to measure practices in the classrooms. The scale has been successfully used in previous research (e.g., Abacioglu et al., 2020 ). It is referred to as the Culturally Responsive Teaching Scale (CRTS; α = 0.81) from hereon. An example item from the survey is “I make use of examples that are relatable for students from culturally different backgrounds” (1 = ‘never’, 5 = ‘always’).

Some items were excluded from the original 40-item scale before data collection because of the following reasons: they did not focus on cultural aspects of teaching and instruction (e.g., “I communicate with parents regarding the progress of their child’s education”), they were too subject-specific, or they were too similar to other items. A previous study provided us with data from the full Culturally Responsive Teaching Scale that was adapted to measure teacher practices (Abacioglu et al., 2020 ). We therefore could check with a different sample about whether excluding these items would have a big impact on the reliability of the scale. Cronbach’s alpha for that sample was 0.90 before and 0.88 after the item reduction. Therefore, we felt confident to exclude these items from the scale.

CRTS items corresponded to only three out of five multicultural education dimensions delineated by Banks ( 2004a , 2004b ). We used these categories to formulate the multicultural education variables that we used in our structural equation models Footnote 2 : teachers’ content integration (α = 0.62), prejudice reduction (α = 0.61), and equity pedagogy (α = 0.76).

Demographics

Teachers reported on the proportion of ethnically minoritized students in their classrooms, whether their school is a denominational school, their own age, gender, ethnic background, and years of teaching experience in years.

Student-level measures

- Peer relationships

A revised version of the Well-being in Relation to Fellow Students questionnaire (Peetsma et al., 2001 ) was used to assess students’ peer relations. It previously was used in a large-scale Dutch research mapping school careers of students from primary until the end of secondary school (COOL 5−18 ; Driessen et al., 2009 ). The original scale of 6 items was combined with 4 items from the Social Integration in the Class questionnaire from Van Damme et al., ( 2002 ). Students responded to 10 statements about (not) getting along with their peers in the classroom (1 = ‘not correct at all’, 5 = ‘very correct’). A sample item includes “In my class, I sometimes feel alone” (see Supplementary Materials for the items). Cronbach’s alpha for the combined scale was 0.86.

- Student engagement

Students responded to 12 statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = ‘no, that is not true’, 5 = ‘yes, that is true’) about their engagement in the classroom. Items were based on the Engagement Versus Disaffection with Learning Scale (Skinner et al., 2008 ) and have been successfully used in previous research (e.g., Abacioglu et al., 2019b ). Half of the statements measure students’ attention, effort, and persistence in initiating and participating in learning activities, reflecting their Behavioral Engagement (α = 0.77). The other half measure students’ motivated participation during learning activities, reflecting their Emotional Engagement (α = 0.65). Examples of items from the subscales are “I try hard to do well in school” and “I enjoy learning new things in class”, respectively. While the reliability of the Emotional Engagement subscale was below optimal, the construct showed good model fit when tested with confirmatory factor analysis (detailed in Supplementary Materials).

Students reported their age, gender, and ethnic backgrounds. Students were assigned to the ethnically minoritized group if they reported either of their parents as having a migration history or if they identified with an ethnic identity other than or in addition to Dutch; the rest of the students were categorized as the ethnic majority group.

Data analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) has the advantage of testing complicated mediation models in a single analysis, simultaneously allowing multiple independent and outcome variables (Gunzler et al., 2013 ). Therefore, we chose to use SEM to investigate our data. We validated our latent constructs, namely, the multicultural education factors that we suggested for the Culturally Responsive Teaching Scale items, and the peer relationships and student engagement factors using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which is detailed in the Supplementary Materials. After CFA, we continued to define our structural model and examined its fit across two groups by looking at measurement invariance and conducting a multigroup analysis. We used the statistical software R (RStudio Version 1.2.1335) package lavaan version 0.6–5 (Rosseel, 2012 ) to specify, estimate, and analyze our models.

Structural equation modeling

Based on the CFA results, we expanded the measurement models by specifying the relationships between the latent variables (i.e., formed the structural model), by creating a non-saturated model, using sum scores for the multicultural education factors (content integration, prejudice reduction, and equity pedagogy) and reflective latent factors for the rest of the variables: student peer relationships, and behavioral and emotional engagement.

We initially planned on using multilevel structural equation modeling to account for the hierarchical nature of our data. To find support for a multilevel approach, we examined the proportion of variance in the student-level variables that was explained by the grouping variable (i.e., teacher). We calculated the ratio of group-level error variance to the total error variance (Intraclass Correlation Coefficients; ICC1) for each item of the latent student-level factors, using the residual data set, which ranged between 0 to 0.006. Given the small values, we decided to use a simpler non-multilevel approach, coupled with bootstrapped standard errors to give us more robust results because of increased power.

At this stage of our analyses, control variables should be included in the structural model as observed variables, and their relationships to our main variables should be defined. We identified the following variables: teachers’ years of teaching, ethnic backgrounds and gender, and whether they are appointed in a denominational school; and students’ ethnic background, age, and gender. Note that student ethnic background could also be considered as a moderator between teacher multicultural education factors, peer relationships, and emotional and behavioral engagement. However, the correlations for ethnic background (using mean scores) indicated no outstanding differences in the strength of the relationships for students with and without a migration history. Therefore, this variable was not considered a moderator.

Including all of these variables in our analyses would lower our power drastically, especially because we wanted to test our model in two independent samples (further detailed below). To overcome this limitation, we used single imputation to deal with missing data (2.2% of the data), using predictive mean matching based on available cases for each variable that is the default method of the mice package (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011 ) in R. Moreover, we used multiple regression analysis to control for our covariates before running the main analysis. This process entails running regression analyses to predict the main variables of interest using control variables and taking the residuals from these predictions to create residual variables. This is a common method that is used to estimate, simplify, and enhance the utility of primary structural model (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2022 ). This allowed higher statistical power because we did not enter the covariates into the structural equation models as separate variables and estimated lower number of parameters. We use the resulting data set from here onwards.

Defining the comparison groups

In line with the accepted categorization of schools in the Netherlands, schools with 70% or more children from migrant backgrounds and schools with 70% or more children with no migration history are considered to be highly concentrated with minoritized and majority group students, respectively (Wielzen & van Dijk-Groeneboer, 2018 ). Therefore, we defined classrooms with ethnically minoritized student concentration equal to or less than 30% as low concentration (46% of the sample), 30–70% as mixed (13.8% of the sample), and 70% or higher as high concentration classrooms (40.2% of the sample). The concentration of classrooms was defined based on students’ reports of their ethnic background. However, because statistical procedures compare two groups at a time, and because the mixed group was comprised of only 13.8% of the sample whereas the other two groups were about three times its size, we merged the mixed and high-concentration classrooms into one group. The analyses should be interpreted because 74.5% of the combined group had an ethnically minoritized student concentration of 70% or higher. The groups that we compare are referred to as Low Concentration and High Concentration groups from here on. Correlation matrices of the Low and High Concentration groups used in SEM can be found in Supplementary Materials.

Measurement invariance

Our specified baseline model is depicted in Fig. 1 to be tested for measurement invariance between the low- and high-concentration groups. We followed the multistep approach during which we gradually introduced constraints to the baseline model for 1) factor loadings, 2) factor loadings and intercepts, and 3) factor loadings, intercepts, and residuals, respectively, to be equal across the two groups. Each model was compared with the previous one to decide on the best-fitting model. The results of model comparisons are shown in Table 1 . A significant χ 2 Diff indicates that the models differ significantly, with smaller AIC, BIC, and χ 2 values indicating a better fit, and a higher df indicates fewer parameters in a model and hence a more parsimonious one . The latent variables were allowed to covary, with the first item of each latent variable being constrained to have a factor loading of 1 for scaling purposes.

Model 1 was significantly different from the baseline model based on the significant χ 2 Diff test statistic , more parsimonious based on the df, and a better fit based on BIC but not AIC. χ 2 Diff between Model 1 and 2 was not significant. However, both AIC and BIC values indicated that Model 2 fits better than Model 1 and is more parsimonious based on the df . Model 3 was significantly different from Model 2 based on the significant χ 2 Diff test statistic , more parsimonious based on the df, and a better fit based on BIC but not on AIC. We chose to further investigate the most constrained model, namely, Model 3, because it featured the lowest BIC, comparable AIC to other models, and was the most parsimonious. Our decision means that we constrained all model parameters to be equal between the low- and high-concentration groups, except for regression coefficients.

Multigroup analysis

The multigroup analysis allows testing whether groups show significant differences in their coefficient estimates. We used this analysis to test our proposition that the relationships between multicultural education, peer relationships, and student engagement can change as a function of classroom composition.

We specified Model 4 to define equal regression coefficients between the two groups, in addition to Model 3 constraining factor loadings, intercepts, and residuals.

The model without regression equality constrains (Model 3) fit the data significantly better than the model with constrains (Model 4) according to the Chi Square Test statistic, χ 2 (11) = 32.823, p < 0.001, and the AIC value, but not the BIC value. Therefore, there is some evidence to suggest differences between groups. We thus investigated the differing relationships between our main variables.

Descriptive statistics

We used latent variables and sum scores in our structural models. For more comparable statistics, we calculated average mean scores for each variable for descriptive statistics. The results are presented in Table 2 for each concentration group and are reported separately for majority and minoritized students when applicable.

Teachers’ mean Content Integration ( t (19.443) = -0.14, p > 0.05), mean Prejudice Reduction ( t (31) = -0.09, p > 0.05), and mean Equity Pedagogy ( t (19.601) = -0.35, p > 0.05) did not significantly differ between Low and High Concentration groups. The majority group students’ Behavioral Engagement was significantly higher than that of the minoritized students in the High Concentration group, t (256.377) = 2.141, p < 0.05.

Finally, compared with the Low Concentration group, students in the High Concentration group in general had significantly better Peer Relationships ( t (608) =− 2.224, p < 0.05), Behavioral Engagement ( t (604.620) = − 2.466, p < 0.01), and Emotional Engagement ( t (605.833) = − 2.905 p < 0.01).

Structural equation models

Following the multigroup analysis results that indicated that regression coefficients were not equal across Low and High Concentration classrooms, we examined the structural models for further interpretation in Fig. 1 . Significant relationships are indicated with non-dashed lines. The thicker the lines, the stronger the relationships between the two variables. The standardized regression coefficients of the significant edges are shown in Fig. 1 . For the rest of the parameter values see Supplementary Materials, Table S3.

In both groups, Peer Relationships were significantly related to students’ Engagement. In the Low Concentration group, the relationships were stronger, which is especially the case for Emotional Engagement (but difference in the strength of these individual associations between groups has not been formally tested for significance). Figure 1 illustrates that, for the Low Concentration group, the relationship between Content Integration and Emotional and Behavioral Engagement and between Equity Pedagogy and only Emotional Engagement were mediated by students’ Peer Relationships. The standardized indirect effect of Content Integration on Emotional Engagement (β = -0.20, p < 0.01) and on Behavioral Engagement (β = -0.15, p < 0.05) were statistically significant. Additionally, the standardized indirect effect of Equity Pedagogy on Emotional Engagement was significant (β = 0.11, p < 0.05) and on Behavioral Engagement was marginally significant (β = 0.09, p = 0.07). In addition, Equity Pedagogy showed a weak but significant relationship with Prejudice Reduction and a strong relationship with Content Integration. Expectedly, Emotional and Behavioral Engagement showed a strong significant positive correlation.

In the High Concentration group, the direct effect of Equity Pedagogy on Emotional Engagement (β = 0.24, p < 0.05), and the direct effects of Peer Relationships on Emotional (β = 0.23, p < 0.05) and on Behavioral Engagement (β = 0.27, p < 0.05) were significant. The results of the fitted model yielded no significant indirect effects in this group, because none of the relationships between the Multicultural Education factors and Peer Relationships reached statistical significance. In addition, all three Multicultural Education factors showed moderate to high positive correlations with each other. Similarly, Emotional and Behavioral Engagement were very strongly correlated.

In the current study, we examined the role of both the pedagogical (i.e., multicultural practices) and structural elements of the learning environment (i.e., minoritized student concentration). Self-Determination Theory postulates that learning contexts that support students’ basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness can positively affect their motivation to learn (for an overview, see Fredricks et al., 2019 ). We argue that multicultural education can especially help to fulfill the needs of relatedness for students, by stimulating meaningful contact (see also ICT), and therefore improve students’ engagement. Previous research findings support the positive effect of multicultural education on student engagement but, to the best of our knowledge, the unique influence of different multicultural education dimensions and the mediating role of students’ relatedness has never been tested.

In classrooms with low minoritized student concentration, we found support for this mediation hypothesis with equity pedagogy having a positive effect and content integration having a negative effect on emotional and behavioral engagement, which was mediated by students’ peer relationships. In the high-concentration classrooms, however, only a direct effect of equity pedagogy on emotional engagement was found.

The low-concentration group

The low minoritized student concentration emphasizes the existing inequalities in society (Leonardelli et al., 2010 ), by also putting minoritized students in the numerical minority. This does not naturally create an equal status for the contact between groups. On the contrary, it creates the basis for the majority group members to perceive themselves as highly prototypical and representative of the larger social group, be it the classroom, school, or the Netherlands. In these unequal status environments, the Social Identity Approach (Abrams & Hogg, 1990 ; Reicher et al., 2010 ) predicts that the members of the dominant group try to keep their status against identity and status ‘threats’, whereas the members of disadvantaged groups show higher ingroup favouritism to make up for the perceived disparity in their status (Olonisakin, 2021 ; Radke et al., 2017 ). Indeed, Steffens et al. ( 2017 ) previously showed that multicultural education can backfire in such unequal contact environments.

In the Low-Concentration learning environments, the positive influence of equity pedagogy and the negative influence of content integration on peer relationships could be attributable to the majority group perceiving multiculturalism to be identity and status threatening, while the minoritized group perceived it as identity supporting and status improving (Deaux et al., 2006 ).

Content integration requires explicit acknowledgment of different cultures and their characteristics and contributions. This can directly challenge the majority group members’ perceived prototypicality of their group for the larger social category, in environments where they are likely to perceive themselves as being highly prototypical. This has been shown to increase negative attitudes toward the outgroup (Steffens et al., 2017 ). Supporting their findings, we also found that content integration negatively influences peer relationships directly and student engagement indirectly. While prejudice reduction practices might have been able to prevent this, our results indicated that teachers who engaged in content integration did not necessarily engage in prejudice reduction (see Fig. 1 or Table B1 for correlations between factors).

Equity pedagogy, on the other hand, is a subtler way of facilitating equal status in contacting parties that can be employed without activating group differences. It disrupts existing structures that perpetuate inequality by expecting all students to learn according to the way in which the instruction is delivered and instead requires tapping into students’ strengths and using tailoring teaching approaches to teach in the way students learn (Banks, 1995 ). Therefore, it adds to the conditions under which multicultural education can increase positive attitudes and hence can improve peer relationships—most importantly, under which students experience equal status (Allport, 1954 ; Dovidio et al., 2017 ).

However, we can expect a larger negative effect size of content integration on peer relationships compared with the positive effect of equity pedagogy by looking at the path coefficients. Based on these effects, we would have expected the majority group members’ reported peer relationships to be more positive compared with the minoritized group students if content integration ignited ingroup favoritism only in the majority group. Yet, the majority and minoritized students reported having similar average peer relationship qualities (see Table 2 ). This could signal that the ingroup favoritism in the minoritized groups, predicted by the Social Identity Approach (Abrams & Hogg, 1990 ; Reicher et al., 2010 ), is activated by content integration.

Higher ingroup favoritism and outgroup discrimination are consistently found in numerically smaller groups (Leonardelli et al., 2010 ), which is suggested to reflect the greater salience and distinctiveness associated with their small group size (Bettencourt et al., 1999 ). In this case, our minoritized group is both in the numerical minority and placed lower in the ethnic societal hierarchy, making them a disadvantaged but distinctive group. In line with this view, such distinctive groups have been shown to be more satisfied with their ingroup compared to non-distinctive groups. This is because a distinctive group is a source of positively valued social identity because it provides sufficient inclusiveness within the ingroup and sufficient differentiation compared with the outgroup, fulfilling both the need to belong and the need to be unique (see Optimal Distinctiveness Theory Brewer, 1991 ; Leonardelli et al., 2010 ). Thus, activating the distinctiveness of groups and providing further validation for the minoritized group through content integration might have led to heightened ingroup favoritism not only in the majority group but also in the minoritized group.

The high-concentration group

Contrary to the low-concentration group, in the high-concentration group, multicultural education factors did not have a significant effect on peer relationships. Nevertheless, students in this group reported having better relationships and higher engagement compared with students in the low-concentration group. These findings might stem from more balanced intergroup interactions because of the demographic landscape of these classrooms. Therefore, we might no longer see the significant negative effect of content integration on peer relationships: Majority group students no longer might perceive their group as highly prototypical of the larger social category of classroom or school because they are in the numerical minority and are thus just another ethnic group within their classrooms. Similarly, the minoritized students might no longer experience an optimal distinctiveness from the outgroup because they are no longer in the numerical minority. In turn, peer relationships in this group are not as strongly related to student engagement, especially emotional engagement, as they were in the low-concentration group. This could signal that, when relationships are less harmonious, they can become a more central factor in students’ educational lives and how much they enjoy it.

Interestingly, the reported quality of peer relationships was higher for the majority group students compared with the minoritized group students in this group. Although this difference was not significant, it might provide some support for the explanation based on the Optimal Distinctiveness Theory that we proposed above for the low-concentration group. Because the majority group members are mostly in the numerical minority in the high-concentration classrooms, they could experience more ingroup favoritism compared with the minoritized students who are now in the numerical majority. Yet, this might be to a lesser extent for the majority group members in the high-concentration group than for the minoritized students in the low-concentration group, because majority group members are still in numerical majority outside their classrooms and schools.

Moreover, because the contact status is likely to be more equal in this group because of minoritized students being in the numerical majority, the positive effect of equity on peer relationships might not be too salient. Yet, equity pedagogy was still directly related to students’ emotional engagement. When learning environments support students’ functioning equitably, regardless of their backgrounds, students seem to enjoy and show more enthusiasm for learning. This, in turn, is highly related to behavioral engagement, indicating that children who enjoy learning also put more effort into it. However, also in this group, the majority group members reported having, on average, significantly higher behavioral engagement compared with their minoritized counterparts. This is in line with previous research that points to the effects of factors such as low teacher expectations (Gershenson et al., 2016 ) or more challenging social environments in and out of school (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2019 ) for the minoritized students, which we did not cover within the scope of this study.

Lastly, in the high-concentration group, teachers who engaged in one aspect of multicultural education seem to have engaged also in others. In line with previous research that revealed that multicultural education is more prevalent in high-concentration classrooms (Agirdag et al., 2016 ), teachers in this group, on average, also engaged more in multicultural education than teachers in the low-concentration group (see Table 2 ). Attention to multicultural education in these classrooms might simply be a natural outcome of the classroom demographics.

Both groups

In both concentration groups, our results supported the propositions of SDT in that peer relationships were positively related to both emotional and behavioral student engagement. However, multicultural education factors would have been anticipated also to have direct effects on student engagement because of their possible influence on other basic psychological needs than relatedness, namely, autonomy and competence . Previous research showed that teachers’ own attitudes can moderate the effect of multicultural practices on student engagement so that only teachers who lead by example themselves and practise what they preach are thought to have a positive effect on students (Abacioglu et al., 2019 ). This could explain the lack of significant relationships in our case. Content integration and prejudice reduction necessitate that teachers explicitly talk about issues around diversity and engage in dialogue that can expose their own stance on these topics, which might not seem authentic to students in certain cases such as employing these practices because of school policy without necessarily having important insights into the realities of their students (Kreber, 2010 ).

Limitations and future research

Our results signal varying effects of multicultural education on peer relationships and engagement, based on the demographic complexion of the learning environment most probably, with different social identity processes in the majority and minoritized students being activated. However, in order to further validate the interpretation of our results, important variables such as ingroup identification and satisfaction, as well as classroom diversity (i.e., how many different groups there are) and ingroup size should be considered in relation to peer relationships (Leonardelli et al., 2010 ). Moreover, the status of the outgroup and its relationship to the ingroup has been suggested as being relevant for such research (Steffens et al., 2017 ). Different ethnic and cultural groups in the Netherlands have different migration histories and occupy different hierarchical positions within society, with minoritized groups from former colonies on the top and the groups with history of migration from Turkey at the bottom (Thijssen et al., 2021 ). The degree to which students benefit from multicultural practices can vary depending on their position in the societal hierarchy. Future researchers are encouraged to examine whether applications of these practices to classrooms with different ethnic profiles in different neighborhoods, and with increasing/decreasing diversity as the share of one ethnic group grows, warrant alternative solutions.

Moreover, how multicultural education affects peer relationships might depend not only on how responsive students are to multiculturalism, but also on teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills through which they implement multicultural practices (Gay, 2018 ). For instance, the most popular ways in which content integration is implemented are through a ‘contributions approach’ or an ‘additive approach’. These entail either insertion of isolated facts about or special units on minoritized groups to the curriculum, without the meaningful transformation of the curriculum that requires viewing information from different perspectives (i.e., ‘transformation approach’), reinforcing the notion that minoritized groups are not integral parts of the mainstream (Banks, 2016 ).

Additionally, it is important to gain deeper insights into the mechanisms underlying the effect of multicultural education on student engagement through peer relationships. Firstly, we cannot be certain that the improved peer relationships in our study were attributable to improved intergroup relationships. Yet, we know from extant research into Dutch schools that, even in culturally diverse schools, friendship networks tend to be segregated along ethnic lines (Baerveldt et al., 2007 ; Fortuin et al., 2014 ; Vermeij et al., 2009 ). In the literature, this has been explained by the homophily principle —individuals’ preferences are associated with similar others because this facilitates mutual understanding and liking (Leszczensky & Pink, 2015 ; Smith et al., 2014 )—which is a powerful predictor of relationship frequency, stability, and quality (Lessard et al., 2019 ). Therefore, it is likely that the positive relationships observed with multicultural education practices and peer relationships are attributable to advances in intergroup relationships that go above and beyond the same-ethnic friendships that tend to form more seamlessly. Secondly, our sample size was not big enough to compare mixed-concentration classrooms (30–70% minoritized student concentration) to classrooms with low and high minoritized student concentrations. We urge future researchers to conduct more-detailed investigations of the suggested psychological processes behind our results in classrooms that are not only segregated but also offer more contact opportunities between different ethnic groups.

If multiculturalism backfires for the majority group members in learning environments in which minoritized individuals might need it the most, how can we prevent resistance to multicultural practices? Previous research that revealed negative effects of activating the diversity of the larger social category on the majority group members tested this against the effects of activating the unity of the larger category (Ehrke & Steffens, 2015 ; Steffens et al., 2017 ; Waldzus et al., 2003 , 2005 ). These two conditions, however, do not need to compete with each other. A focus on shared values such as democracy, equality, and human integrity (Mattei & Broeks, 2018 ) together with multicultural practices can be an essential for both appreciating cultural differences and achieving greater social cohesion. It would be fruitful to investigate the combined effect of these practices on peer relationships and motivation. Moreover, the above-mentioned research focused on the effect of mere priming messages that reflected unity or diversity. The effects of educational practice for an extended period, however, can yield different results that need to be better unwrapped by using a longitudinal design.

Scholars have extensively discussed multicultural theories and their importance for motivational processes and school success (e.g., Au, 1980 ; Banks, 1995 ; Gay, 2000; Hollins, 1996 ; Ladson-Billings, 1995 ; Nieto, 1996 ; Sleeter, 1991 ). Yet, to the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to provide a detailed and quantitative account of the current segregated learning environments in the Netherlands in terms of multicultural curriculum and instruction, as well as their possible impact on the desired student outcomes that are reported in similar studies, which are mostly qualitative in nature and are conducted with preservice teachers using hypothetical scenarios (Agirdag et al., 2016 ).

Previous studies of learning environments have shown that factors such as perceived relationships with peers and teachers during academic-related activities, in addition to academic experiences, have a significant influence on student satisfaction, self-efficacy motivation for learning, and academic accomplishment (Lin et al., 2019 ). Our results corroborated these earlier findings in two different learning environments, namely, low- and high-concentration classrooms. Our findings indicate that some multicultural practices can improve, while other practices can impede, student engagement through peer relationships, depending on the characteristics of the learning environment. This can be of particular importance to the minoritized groups who perceive educational attainment as a means to social mobility (Alt, 2017 ). Therefore, improving the quality of peer relationships can be one way to mitigate the lower educational standing of the minoritized students within the Dutch education system compared with their ethnic majority peers (OECD, 2014 ; Thijs et al., 2014 ).

Our results are a good reminder that, while the representation of minoritized perspectives and lives is important, challenging the structures that perpetuate inequality (through equity pedagogy) can make the most difference by creating equal opportunities for individuals to thrive. It is crucial to increase the effectiveness of internal and external support services and resources for teachers to improve their beliefs in the need for a multicultural approach (Monsen et al., 2014 ), and to strengthen their confidence in their ability to create learning environments that match the diverse needs of all of their students.

Declarations

Current Themes of Research

The corresponding author, Ceren Abacioglu’s main research interests include multicultural ideologies and multicultural education, psychological underpinnings of interethnic relationships that take place in schools, motivational outcomes in relation to educational pedagogies and group processes.

Sacha Epskamp works in the field of psychometrics, with a special focus on Structural Equation Modeling, Multivariate Statistics, and Network Modeling. His research centers around the development and application of Network Modeling to psychological research.

Agneta Fischer’s general theme of research is the influence of social context on emotion, emotion recognition and emotion regulation, focusing mostly on interpersonal emotion recognition; hate, contempt, revenge, humiliation; and role of negative emotions in the development of populism.

Monique Volman’s main areas of research include learning environments for meaningful learning, diversity, and the use of ICT in education, issues which she approaches from a socio-cultural theoretical perspective.

Most Relevant Publications

Ceren Abacioglu

Abacioglu, C. S. , Volman, M., & Fischer, A. (2020). Teacher multicultural attitudes and perspective taking abilities as factors in culturally responsive teaching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90 (3), 736–752.

Abacioglu, C. S. , Volman, M., & Fischer, A. (2019). Teacher interventions to student misbehaviours: The role of ethnicity, emotional intelligence, and multicultural attitudes. Current Psychology (published online), 1–13 .

Abacioglu, C. S. , Zee, M., Hanna, F., Soeterik, I. M., Fischer, A., & Volman, M. (2019). Practice what you preach: The moderating role of teacher attitudes on the relationship between prejudice reduction and student engagement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86 , 102887.

Abacioglu, C. S. , Isvoranu, A., Verkuyten, M., Thijs, J, & Epskamp, S. (2019). Exploring multicultural classroom dynamics: A network analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 74 , 90–105.

Sacha Epskamp

Abacioglu, C. S., Isvoranu, A., Verkuyten, M., Thijs, J, & Epskamp, S. (2019). Exploring multicultural classroom dynamics: A network analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 74 , 90–105.

Epskamp, S. (2015). semPlot: Unified visualizations of Structural Equation Models. Structural Equation Modeling. Structural Equation Modeling 22 (3), 474–483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.937847

Open Science Collaboration (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 (6251), aac4716. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Agneta Fischer

Abacioglu, C. S., Volman, M., & Fischer, A. (2020). Teacher multicultural attitudes and perspective taking abilities as factors in culturally responsive teaching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90 (3), 736–752.

Abacioglu, C. S., Volman, M., & Fischer, A. (2019). Teacher interventions to student misbehaviours: The role of ethnicity, emotional intelligence, and multicultural attitudes. Current Psychology (published online), 1–13 .

Abacioglu, C. S., Zee, M., Hanna, F., Soeterik, I. M., Fischer, A., & Volman, M. (2019). Practice what you preach: The moderating role of teacher attitudes on the relationship between prejudice reduction and student engagement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86 , 102887.

Kommattam, P., Jonas, K. J., & Fischer, A. H. (2019). Perceived to feel less: Intensity bias in interethnic emotion perception. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 84 , [103809].

Monique Volman

Sincer, I., Volman, M ., van der Veen, I., & Severiens, S. (2021). The relationship between ethnic school composition, school diversity climate and students’ competences in dealing with differences. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 47 (9), 2039–2064.

Sincer, I., Severiens, S., & Volman, M. (2019). Teaching diversity in citizenship education: Context-related teacher understandings and practices. Teaching and Teacher Education , 78 , 183–192.

All the procedures described in the Data Analysis section were performed using the remaining teacher and student data.

Also see Supplementary Materials for an exploratory factor analysis for the items. These factor analysis results were not considered when forming the multicultural education variables, because the analysis results suggested inadequate sampling for reliable results.

Abacioglu, C. S., Isvoranu, A.-M., Verkuyten, M., Thijs, J., & Epskamp, S. (2019a). Exploring multicultural classroom dynamics: A network analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 74 , 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.02.003

Abacioglu, C. S., Zee, M., Hanna, F., Soeterik, I. M., Fischer, A. H., & Volman, M. (2019b). Practice what you preach: The moderating role of teacher attitudes on the relationship between prejudice reduction and student engagement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86 , 102887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102887

Abacioglu, C. S., Volman, M., & Fischer, A. H. (2020). Teachers’ multicultural attitudes and perspective taking abilities as factors in culturally responsive teaching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90 , 736–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12328

Abrams, D., & Hogg, M. A. (1990). An introduction to the social identity approach. Social Identity Theory: Constructive and Critical Advances , 1 (9).

Agirdag, O., Merry, M. S., & Van Houtte, M. (2016). Teachers’ understanding of multicultural education and the correlates of multicultural content integration in Flanders. Education and Urban Society, 48 (6), 556–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124514536610

Article Google Scholar

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice . Addison-Wesley.

Google Scholar

Alt, D. (2017). Constructivist learning and openness to diversity and challenge in higher education environments. Learning Environments Research, 20 , 99–119.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2022). Residual structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal . https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2022.2074422

Au, K. H. (1980). Participation structures in a reading lesson with Hawaiian children: Analysis of a culturally appropriate instructional event. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 11 (2), 91–115. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.1980.11.2.05x1874b

Baerveldt, C., Zijlstra, B., De Wolf, M., Van Rossem, R., & Van Duijn, M. A. (2007). Ethnic boundaries in high school students' networks in Flanders and the Netherlands. International sociology, 22 (6), 701–720.

Baker, R. S., D’Mello, S. K., Rodrigo, M. M. T., & Graesser, A. C. (2010). Better to be frustrated than bored: The incidence, persistence, and impact of learners’ cognitive–affective states during interactions with three different computer-based learning environments. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 68 (4), 223–241.

Banks, J. A. (1995). Multicultural education: Its effects on students’ racial and gender role attitudes. In J. A. Banks & C. A. M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (pp. 617–627). Jossey-Bass.

Banks, J. A. (2004a). Multicultural education: Historical development, dimensions, and practice. In J. A. Banks & C. A. M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 3–29). Jossey-Bass.

Banks, J. A. (2004b). Multicultural education: Historical development, dimensions, and practice. In J. A. Banks & C. A. M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 3–29). Jossey-Bass.

Banks, J. A. (2016). Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching (6th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1111/curi.12002

Bettencourt, B. A., Miller, N., & Hume, D. L. (1999). Effects of numerical representation within cooperative settings: Examining the role of salience in in-group favouritism. British Journal of Social Psychology, 38 (3), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466699164167

Bingham, G. E., & Okagaki, L. (2012). Ethnicity and student engagement. In A.L. Reschly, L.C. Sandra and C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 65–97). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_4

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17 (5), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001

CBS. (2020b). Jaarrapport integratie 2020b .

Christov-Moore, L., Simpson, E. A., Coudé, G., Grigaityte, K., Iacoboni, M., & Ferrari, P. F. (2014). Empathy: Gender effects in brain and behavior. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 46 (4), 604–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.001

Cortés, C. E. (2000). The Children Are Watching: How the Media Teach about Diversity. Multicultural Education Series. Teachers College Press, New York.

de Bruijn, Y., Amoureus, C., Emmen, R. A., & Mesman, J. (2020). Interethnic prejudice against Muslims among White Dutch children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 51 (3–4), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022120908346

Deaux, K., Reid, A., Martin, D., & Bikmen, N. (2006). Ideologies of diversity and inequality: Predicting collective action in groups varying in ethnicity and immigrant status. Political Psychology, 27 (1), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00452.x

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior . Plenum.

Book Google Scholar

Dincer, A., Yeşilyurt, S., Noels, K. A., & Vargas Lascano, D. I. (2019). Self-determination and classroom engagement of EFL learners: A mixed-methods study of the self-system model of motivational development. SAGE Open, 9 (2), 1–15.

Dovidio, J. F., Love, A., Schellhaas, F. M., & Hewstone, M. (2017). Reducing intergroup bias through intergroup contact: Twenty years of progress and future directions. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20 (5), 606–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217712052

Driessen, G., Mulder, L., Ledoux, G., Roeleveld, J., & Veen, I. van der. (2009). Cohortonderzoek COOL5–18. Technisch rapport basisonderwijs, eerste meting 2007/08.

Ehrke, F., & Steffens, M. C. (2015). Diversity-training: Theoretische grundlagen und empirische befunde (diversity training: Theoretical foundations and empirical findings). In E. Hanappi-Egger & R. Bendl (Eds.), Diversitat, diversifizierungund (ent)solidarisierung in der organisationsforschung (pp. 205–221). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. (2019). Integrating students from migrant backgrounds into schools in Europe: National policies and measures (Eurydice R). Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2797/222073

Fortuin, J., van Geel, M., Ziberna, A., & Vedder, P. (2014). Ethnic preferences in friendships and casual contacts between majority and minority children in the Netherlands. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 41 , 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.05.005

Fredricks, J. A., Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2019). Interventions for student engagement: Overview and state of the field. In A. L. R. and S. L. C. Jennifer A. Fredricks (Eds.), Handbook of student engagement interventions: Working with disengaged students (pp. 1–11). Elsevier.

Garcia, C., & Chun, H. (2016). Culturally responsive teaching and teacher expectations for Latino middle school students. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 4 (3), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000061

Gay, G. (2013). Teaching to and through cultural diversity. Curriculum Inquiry, 43 (1), 48–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/curi.12002

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Gershenson, S., Holt, S. B., & Papageorge, N. W. (2016). Who believes in me? The effect of student–teacher demographic match on teacher expectations. Economics of Education Review, 52 (1), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.002

Gunzler, D., Chen, T., Wu, P., & Zhang, H. (2013). Introduction to mediation analysis with structural equation modeling. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry . https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.06.009

Hollins, E. R. (1996). Culture in school learning: Revealing the deep meaning. Erlbaum . https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315813615

Hughes, J. M., Bigler, R. S., & Levy, S. R. (2007). Consequences of learning about historical racism among European American and African American children. Child Development, 78 (6), 1689–1705. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01096.x

Huijnk, W., & Andriessen, I. (Eds.). (2016). Integratie in zicht? De integratie van migranten in Nederland op acht terreinen nader bekeken [Integration in sight? A closer look at the integration of migrants in the Netherlands in eight areas] . Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau; SCP.

Huilla, H., Lay, E., & Tzaninis, Y. (2022). Tensions between diverse schools and inclusive educational practices: Pedagogues’ perspectives in Iceland, Finland and the Netherlands. A Journal of Comparative and International Education , 1–17.

Klein, S. S. (2012). Gender equitable education. In J.A. Banks (Ed.), Encyclopedia of diversity in education (pp. 961–969). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X06298778