By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

A look at how corruption works in the Philippines

The Philippines is perceived to be one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Of 180 countries, the Philippines ranked 116 in terms of being least corrupt. This means that the country is almost on the top one-third of the most corrupt countries, based on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) published by Transparency International.

According to CPI, the Philippines scored a total of 33 points out of 100. Even as far back as 2012, it has fluctuated around the same CPI score, with the highest score being 38 points in 2014 and the lowest being 33 points in 2021 and 2022. To further contextualize how low it scored, the regional average CPI score for the Asia-Pacific region is 45, with zero as highly corrupt. And of the 31 countries and territories in the region, the Philippines placed 22nd (tied with Mongolia).

It must be noted, however, that CPI measures perceptions of corruption and is not necessarily the reality of the state of corruption. CPI reflects the views of experts or surveys of business people on a number of corrupt behavior in the public sector (such as bribery, diversion of public funds, nepotism in the civil service, use of public office for private gain, etc.). CPI also measures the available mechanisms to prevent corruption, such as enforcement mechanisms, effective prosecution of corrupt officials, red tape, laws on adequate financial disclosure and legal protection for whistleblowers.

These data are taken from other international organizations, such as the World Bank, World Economic Forum, private consulting companies and think tanks.

Of course, measuring actual corruption is quite difficult, especially as it involves under-the-table activities that are only discovered when they are prosecuted, like in the case of the ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses, which was estimated to be up to $10 billion based on now-deleted Guinness World Records and cited as the “biggest robbery of a government.” Nevertheless, there still exists a correlation between corruption and corruption perceptions.

4 Syndromes

Corruption does not come in a single form as well. In a 2007 study, Michael Johnston, a political scientist and professor emeritus at Colgate University in the United States, studied four syndromes (categories) of corruption that were predominant in Asia, citing Japan, Korea, China and the Philippines as prime examples of each category.

The first category is Influence Market Corruption, wherein politicians peddle their influence to provide connections to other people, essentially serving as middlemen. The second category is Elite Cartel Corruption, wherein there exist networks of elites that may collude to protect their economic and political advantages. The third form of corruption is the Official Mogul Corruption, wherein economic moguls (or their clients) are usually the top political figures and face few constraints from the state or their competitors.

Finally, there is the form of corruption that the Philippines is familiar with. Oligarch-and-Clan Corruption is present in countries with major political and economic liberalization and weak institutions. Corruption of this kind has been characterized by Johnston as having “disorderly, sometimes violent scramble among contending oligarchs seeking to parlay personal resources into wealth and power.” Other than the Philippines, corruption in Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka falls under the same syndrome.

In the Philippines, Oligarch-and-Clan Corruption manifests itself in the political system. As Johnston noted, in this kind of corruption, there is difficulty in determining what is public and what is private (i.e., who is a politician and who is an entrepreneur). Oligarchs attempt to use their power for their private benefit or the benefit of their families. From the Aquinos, Binays, Dutertes, Roxases and, most notoriously, the Marcoses, the Philippines is no stranger to political families. In a 2017 chart by Todd Cabrera Lucero, he traced the lineage of Philippine presidents and noted them to be either related by affinity or consanguinity.

Corruption in the Philippines by oligarch families is not unheard of. In fact, the most notable case of corruption in the Philippines was committed by an oligarchic family—the Marcos family. The extent of the wealth stolen by former dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his wife has been well-documented. In fact, several Supreme Court cases clearly show the extent of the wealth that the Marcoses had stolen.

In an Oligarch-and-Clan system of corruption, oligarchs will also leverage whatever governmental authority they have to their advantage. Going back to the Marcos example, despite their convictions, the Marcoses have managed to weasel their way back into power, with Ferdinand Marcos Jr. becoming the 17th President despite his conviction for tax violation. Several politicians have also been convicted of graft and corruption (or have at least been hounded by allegations of corruption) and still remain in politics. As observed by Johnston in his article, though Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos are the popular images of corruption in the Philippines, he also noted other entrenched oligarchs throughout the country.

Finally, factions also tend to be “unstable and poorly disciplined.” The term “balimbing” is often thrown around in local politics but, more than that, the Philippines is also familiar with politically-motivated violence and disorder.

All these features are characteristics of Oligarch-and-Clan corruption, where these oligarchic families continue to hold power and politicians exploit their positions to enrich themselves or their families.

Corruption, no matter what kind, needs to be curbed. It results in loss of government money, which could have been used to boost the economy and help ordinary citizens, especially those from the lower income sectors.

According to the 2007 study, the Office of the Ombudsman had, in 1999, pegged losses arising from corruption at P100 million daily, whereas the World Bank estimates the losses at one-fifth of the national government budget. For relatively more updated figures, former Deputy Ombudsman Cyril Ramos claimed that the Philippines had lost a total of P1.4 trillion in 2017 and 2018. These estimates are in line with the World Bank estimates of one-fifth (or 20 percent) of the national budget.

So grave is the adverse effect of corruption that the international community recognized it as an international crime under the United Nations Convention Against Corruption where perpetual disqualification of convicted officials is recommended.

But the question stands: can corruption be eradicated in developing countries like the Philippines? Many Philippine presidents promised to end corruption in their political campaigning, but none has achieved it so far. If the government truly wants to end corruption, it must implement policies directed against corruption, such as lifting the bank secrecy law, prosecuting and punishing corrupt officials, increasing government transparency and more. INQ

This is part of the author’s presentation at DPI 543 Corruption: Finding It and Fixing It course at Harvard Kennedy School, where he is MPA/Mason fellow.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

This article reflects the personal opinion of the author and not the official stand of the Management Association of the Philippines or MAP. He is a member of MAP Tax Committee and MAP Ease of Doing Business Committee, co-chair of Paying Taxes on Ease of Doing Business Task Force and chief tax advisor of Asian Consulting Group. Feedback at [email protected] and [email protected] .

Curated business news

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

Corruption and Development pp 121–137 Cite as

Challenges to the Philippine Culture of Corruption

- Edna Estifania A. Co

255 Accesses

1 Citations

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Development ((PSD))

Upon the suggestion of financing institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, corruption has taken centre stage in policy discourse, making corruption the locus of many re-engineering efforts in Philippine governance (Transparency and Accountability Network, internal documents, 2005). Although there are no systematic studies on the extent of economic losses due to corruption, the Ombudsman estimates that the Philippines has lost approximately US$48 billion during the last 20 years, while the Commission on Audit estimates a loss of $44.5 million each year and the World Bank argues that around 20 per cent of the annual budget is lost to corruption (Romero, undated article). Meanwhile, a Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey reports a popular perception of public institutions riddled with corruption, leading to low public confidence in government (SWS, 2005).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Amorado, R. V. (2005), Fixing Society. An Ethnographic Study of Fixers in the Philippines , Ateneo de Davao University, July, unpublished dissertation

Google Scholar

Aquino, B. A. (1999), Politics of Plunder. The Philippines under Marcos , 2nd edn, University of the Philippines, College of Public Administration, Philippines

Aquino, Norman (2005), ‘Corruption: Cultural or institutional?’, in Business World Anniversary Report 2005 , pp. 26–8

Azfar, O. and Gurgur, T. (2000), ‘Decentralization and Corruption in the Philippines’, Mimeo, IRIS Center, University of Maryland

Batalla, E. C. (2000), ‘De-institutionalizing Corruption in the Philippines: Identifying Strategic Requirements for Reinventing Institutions’, conference paper for the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and Yuchengco Center For East Asia of De La Salle University, Makati City, August

Bhargava, E. and Bolongaita, V. (2003), Challenging Corruption in Asia: Case Studies and a Framework for Action , Washington DC, World Bank Publications

Book Google Scholar

Carino, L. (ed.) (1986), Bureaucratic Corruption in Asia: Causes, Consequences, and Controls , University of the Philippines Press, College of Public Administration, Philippines

Carino, L., Iglesias, Gabrielle, and Mendoza, F. (1999), ‘Initiatives Against Corruption: the Philippine Case’, Occasional paper UP-NCPAG 99–1 , July

Co, Edna E. A., Tigno, Jorge, Lao, Ma. Elissa Jayme, and Sayo, Margarita (2005), Philippine Democracy Assessment: Free and Fair Flections and the Democratic Role of Political Parties , Friedrich Ebert Stiftung and University of the Philippines National College of Public Administration and Governance, Philippines. Distributed by Ateneo de Manila University Press

Co, E. E. A. Lim, M. O., Jayme-Lao, M. E. and Juan, L.J. (2007), Philippine Democracy Assessment. Minimizing Corruption . British Council, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Philippine Democracy Audit, and Transparency and Accountability Network. Manila, Philippines

Coronel, S. (ed.) (1998), Pork and other Perks: Corruption and Governance in the Philippines , Quezon City Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

De Dios, E. and Ferrer, R. (2001), ‘Corruption in the Philippines. Framework and Context’, Public Policy , 5(1): 1–42, University of the Philippines Centre for Integrative and Development Studies

Democracy Audit (2005), Notes from a Focus Group Discussion among key informants in Luzon , Philippines, July

Doig, A. and Riley, S. (2000), Corruption and Anti-Corruption Strategies: Issues and Case Studies from Developing Countries , Washington DC, Work Bank

Eigen, P. (2000), ‘The Role of Civil Society’, in Corruption and Integrity Improvement Initiatives in Developing Countries , Washington DC, Work Bank

Endriga, J. (2003), ‘Stability and Change: Civil Service in the Philippines’, in Introduction to Public Administration in the Philippines: A Reader , Bautista, Victoria, Alfiler, Ma. Concepcion, Reyes, Danilo and Tapales, Proserpina (eds) UP-NCPAG Philippines

Hutchcroft, Paul D. (1998), Booty Capitalism: the Politics of Banking in the Philippines , Ateneo de Manila University Press, Quezon City, Philippines

Kaufmann, D. and Wei, S-J. (1998), ‘Does Grease Money Speed Up the Wheels of Commerce?’, World Bank Institute and Development Research Group, Washington DC

Klitgaard, R. (1998), ‘International Cooperation against Corruption’, RAND Graduate School, International Development and Security, Santa Monica, California

Lim, J. and Pascual, C. (2000), ‘The Detrimental Role of Biased Politics: Framework and Case Studies’, Study Paper 3 prepared for Philippine Centre for Policy Studies, Quezon City, Philippines

Mendoza, A. Jr. (2000), ‘The Industrial Anatomy of Corruption: Government Procurement, Bidding and Award of Contracts’, Study Paper 2a, Quezon City, Philippines

Pascual, C. and Lim, J. (2001), ‘Corruption and Weak Markets: the BW Resources Stock Market Scam’, in Public Policy , Center For Integrative and Development Studies, University of The Philippines, January–June, pp. 109–29

Putnam, R. (2000), Bowling Alone: the Collapse and Revival of American Community , New York, Simon and Schuster

Romero, S. (undated), Civil Society Initiated Measures for Combating Corruption in the Philippines , Development Academy of the Philippines, Philippines

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1996), ‘Democracy and Grand Corruption’ in International Social Science Journal , 149 September, pp. 365–80, also in Explaining Corruption: the Politics of Corruption , Robert Williams (ed.), Elgar Reference Collection UK and USA, pp. 321–36

Santiago, Miriam Defensor (1991), How to Fight Graft , Movement for Responsible Public Service, Manila, Zita Publishing Corporation

Scott, J. (2000), ‘The Analysis of Corruption in Developing Nations’, in Robert Williams (ed.), Explaining Corruption. The Politics of Corruption , Elgar Reference Collection UK and USA

Segundo, R. (undated), Civil Society Initiated Measures for Combating Corruption in the Philippines , Development Academy of the Philippines, Philippines

Social Weather Stations (SWS), National Survey Report , September–October 1999, 1999 and 2005

Transparency International (2004), Global Corruption Report 2004 , Pluto Press, London and Virginia, USA

Varela, Amelia P. (2003), ‘The Culture Perspective in Organization Theory: Relevance to Philippine Public Administration’, in Introduction to Public Administration in the Philippines: a Reader , Bautista, Victoria, Alfiler, Ma. Concepcion, Reyes, Danilo and Tapales, Proserpina (eds) 2nd edition, UP-NCPAG, Philippines

Virtucio, M. A. and Lalunio, M. (2000), ‘Tender Mercies: Contracts, Concessions and Privatization’, Study Paper 26, Quezon City, Philippines

Werner, S. (2000), ‘New Directions in the Study of Administrative Corruption’, in Robert Williams (ed.), Explaining Corruption. The Politics of Corruption , Elgar Reference Collection UK and USA

Williams R. (ed.) (2000), Explaining Corruption. The Politics of Corruption , Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

World Economic Forum (2004), Global Corruption Report 2004, Transparency International , Pluto Press, London

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Manchester, UK

Sarah Bracking

Copyright information

© 2007 Edna Estifania A. Co

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Co, E.E.A. (2007). Challenges to the Philippine Culture of Corruption. In: Bracking, S. (eds) Corruption and Development. Palgrave Studies in Development. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230590625_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230590625_6

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-35769-7

Online ISBN : 978-0-230-59062-5

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social & Cultural Studies Collection Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Analysis: Why Corruption Thrives in the Philippines

Create an FP account to save articles to read later and in the FP mobile app.

ALREADY AN FP SUBSCRIBER? LOGIN

World Brief

- Editors’ Picks

- Africa Brief

China Brief

- Latin America Brief

South Asia Brief

Situation report.

- Flash Points

- War in Ukraine

- Israel and Hamas

- U.S.-China competition

- Biden's foreign policy

- Trade and economics

- Artificial intelligence

- Asia & the Pacific

- Middle East & Africa

Fareed Zakaria on an Age of Revolutions

Ones and tooze, foreign policy live.

Spring 2024 Issue

Print Archive

FP Analytics

- In-depth Special Reports

- Issue Briefs

- Power Maps and Interactive Microsites

- FP Simulations & PeaceGames

- Graphics Database

From Resistance to Resilience

The atlantic & pacific forum, principles of humanity under pressure, fp global health forum 2024, fp security forum.

By submitting your email, you agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use and to receive email correspondence from us. You may opt out at any time.

Your guide to the most important world stories of the day

Essential analysis of the stories shaping geopolitics on the continent

The latest news, analysis, and data from the country each week

Weekly update on what’s driving U.S. national security policy

Evening roundup with our editors’ favorite stories of the day

One-stop digest of politics, economics, and culture

Weekly update on developments in India and its neighbors

A curated selection of our very best long reads

Why Corruption Thrives in the Philippines

A marcos might soon be back in power in manila. that’s because political dynasties are more powerful than parties..

- Southeast Asia

With Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte ineligible for reelection, Ferdinand Marcos Jr.—widely known as “Bongbong”—is poised to win a landslide victory at the polls on May 9. His father, Ferdinand Marcos Sr., who ruled as a dictator for 14 years under martial law, was known for his big infrastructure projects but also for his enormous corruption. (The World Bank estimates he stole between $5 billion and $10 billion over the course of his rule.) Marcos Jr., in turn, has been accused of graft and convicted of tax evasion.

So what accounts for Marcos Jr.’s popularity in spite of his legacy of malfeasance? Like voters everywhere, Filipinos say they don’t support corruption. In fact, 86 percent of Filipinos surveyed in 2020 by Transparency International called corruption in government a big problem. One famous scandal involved members of congress funneling money to phony nongovernmental organizations in exchange for kickbacks in what is known widely as the pork barrel scam and which came to light in July of 2013. Janet Lim-Napoles, a businesswoman and the convicted ringleader of the scheme, claimed Marcos Jr. was involved, although he denied any knowledge and said his signature on forms releasing money to fake NGOs was forged.

In a political system dominated by powerful families, corrupt politicians can still succeed. Dynasties are so influential that they have largely replaced political parties as the bedrock of Philippine politics. Politicians commonly jump from one party to another, making party labels meaningless. In a country where parties come and go overnight, voters look to families to evaluate candidates.

The history of the Philippine elite—and why voters continue to uphold their power—has colonial roots.

Over the past four years, I have examined the impact of political dynasties on election outcomes in the Philippines and analyzed the results of 10 election cycles since 1992 involving 500,000 candidates. The results may help explain the Marcos family’s political staying power. Despite being chased out of the country when Marcos Sr. fell from power in 1986, the family bounced back to political prominence in only a few years: Marcos Jr. became a governor in 1998 and a senator in 2010. Imee Marcos later took on his former role as governor and is currently a senator, having been succeeded as governor by her own son Matthew Manotoc in 2019.

My research shows that, when given a choice, Philippine voters are less likely to vote for corrupt politicians. After accounting for a candidate previously holding office—since incumbents are more likely to be reelected and more likely to face corruption charges—candidates indicted for corruption are 5 percent to 7 percent less likely to be elected. This is similar to how voters react to corruption in other countries. In Brazil, which also suffers from substantial corruption, researchers Claudio Ferraz and Frederico Finan showed that in the 2004 election, when there was evidence that a mayor had engaged in corruption on one occasion, that mayor was 4.6 percent less likely to be reelected.

A supporter holds pictures of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his wife Imelda Marcos as Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and Sara Duterte-Carpio take part in an election rally in Caloocan, Philippines, on Feb. 19. Ezra Acayan/Getty Images

But Philippine voters don’t punish politicians from large political dynasties even when they’ve been indicted for corruption. Ronald Mendoza and researchers at the Ateneo School of Government calculated that, as of 2019, 80 percent of governors, 67 percent of members of the House of Representatives, and 53 percent of mayors had at least one relative in office. These rich and powerful family networks can protect politicians from real accountability and keep reform at bay.

The history of the Philippine elite—and why voters continue to uphold their power—has colonial roots. When the United States seized control of the Philippines in 1898, it pledged to give land to the poor. The opposite happened. The United States spent $7 million—almost as much as it paid for Alaska in the 1860s—to buy land from Catholic friars who had run much of the country. But the land was sold at prices well above what the poor could afford. The United States also instituted a system of land titles. This could have helped protect poor farmers from being dispossessed, but the land titles were so expensive and complicated to acquire that only the well-off got titles. The rich were able to buy up more land, while the poor were left without titles or access to the best land. My research shows that areas in the Philippines with more land inequality and where more of these titles were issued by 1918 have a higher concentration of dynasties today.

The United States created a system where only property owners could vote, limiting the franchise to 1 percent of the population in the 1907 legislative elections. Wealthy landowners appointed allies to run the civil service and passed laws to cement their power. For example, in 1912, the Philippine Assembly made it a crime to break a labor contract, which effectively forced sharecroppers to stay on large plantations. Don Joaquín Ortega was appointed the first governor of La Union in 1901, and 120 years later his descendants are still governors.

Voters turn to political dynasties for a variety of reasons. Familiarity certainly helps. Families are also known for delivering pork barrel projects and even direct payouts before elections. Vote buying in the form of gifts or cash is common in the Philippines. Some dynasties have also used force to turn out votes of limited competition. In return, the ruling families tend to commission populist projects. Jinggoy Estrada, son of former President Joseph Estrada, helped build day care centers when he was mayor of San Juan. He also was twice indicted for corruption but never convicted.

The youthfulness of the Philippine population helps obscure the truth of the Marcos dictatorship. About 70 percent are under 40 years old, compared to 51 percent in the United States. Marcos Sr. was forced out of office 36 years ago, which is well before much of the electorate was even born. Few have a recollection of martial law.

Deeply entrenched political dynasties have hollowed out the political process, making elections not about parties or ideas but about family names.

Over the intervening years, the Marcos clan has spruced up its image: Marcos Jr. appeared as a child in a movie glorifying his father. His older sister ran a children’s TV show when Marcos Sr. was in power. Marcos Sr. projected an air of power and pride that older voters remember. In addition, current Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte gave the clan a boost in 2016 when he had Marcos Sr. reburied in the “Cemetery of Heroes” in Manila.

Marcos Jr.’s campaign also appeals to nostalgia among voters who lived during the era when Marcos Sr. built new rail lines, cultural centers, hospitals, and other infrastructure projects, as well as among younger voters who have been sold on this sanitized image of the Marcos era. Some recall the martial law period as one of peace (although not for the 34,000 political dissenters whom Amnesty International estimates were tortured by the government). The Philippine economy grew rapidly during much of the Marcos period, though it ended in a steep downturn in GDP and a huge increase in government debt.

The other major candidates running against Marcos Jr. don’t come from such important families with such deep political connections. Marcos Jr. has avoided saying much about his opponents who have attacked him and his revisionist Marcos history. This has made the campaign all about him and left his opponents looking small. Marcos Jr. has also played up his alliance with the Duterte family, as the outgoing president remains widely popular despite the brutal violence of his anti-drug campaign. Duterte’s daughter Sara Duterte-Carpio is running for vice president, further cementing a Duterte-Marcos alliance.

Across generations, the deeply entrenched political dynasties of the Philippines have hollowed out the political process, making elections not about parties or ideas but about family names. Powerful families date back to the Spanish period and have cemented their hold on power. While voters categorically oppose corruption, they continue to support families who deliver pork spending but do little for the long-term health of the country. Marcos Jr. has traded on carefully curated nostalgia about his father’s reign to propel himself to the presidency.

Daniel Bruno Davis is a Ph.D. graduate from the University of Virginia, where he studied Philippine politics and corruption. Twitter: @Daniel_B_Davis

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? Log In .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Not your account? Log out

Please follow our comment guidelines , stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username:

I agree to abide by FP’s comment guidelines . (Required)

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.

Sign up for Editors' Picks

A curated selection of fp’s must-read stories..

You’re on the list! More ways to stay updated on global news:

What Ghana Can Learn From Taiwan

Will washington sanction sudan’s rsf, u.s. allies relieved after senate passes long-delayed aid bill, u.k. passes controversial rwanda deportation bill, ukraine is still outgunned by russia, editors’ picks.

- 1 Will Washington Sanction Sudan’s RSF?

- 2 Ukraine Is Still Outgunned by Russia

- 3 New Zealand Becomes the Latest Country to Pivot to the U.S.

- 4 The Strategic Unseriousness of Olaf Scholz

- 5 The Iran-Israel War Is Just Getting Started

- 6 Is the U.S. Preparing to Ban Future LNG Sales to China?

Ukraine, Israel, Indo-Pacific Aid Bill Passes U.S. Senate

U.k. parliament passes controversial rwanda asylum deportation bill, ukraine artillery shortage to persist even if u.s. aid package passes congress, more from foreign policy, arab countries have israel’s back—for their own sake.

Last weekend’s security cooperation in the Middle East doesn’t indicate a new future for the region.

Forget About Chips—China Is Coming for Ships

Beijing’s grab for hegemony in a critical sector follows a familiar playbook.

‘The Regime’ Misunderstands Autocracy

HBO’s new miniseries displays an undeniably American nonchalance toward power.

Washington’s Failed Africa Policy Needs a Reset

Instead of trying to put out security fires, U.S. policy should focus on governance and growth.

The Strategic Unseriousness of Olaf Scholz

Is the u.s. preparing to ban future lng sales to china, the iran-israel war is just getting started, new zealand becomes the latest country to pivot to the u.s..

Sign up for World Brief

FP’s flagship evening newsletter guiding you through the most important world stories of the day, written by Alexandra Sharp . Delivered weekdays.

- Subscribe Now

IN NUMBERS: Impact of corruption on the Philippines

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Are you aware of how huge the impact of corruption is on the country?

Under the administration of former president Benigno Aquino III, the campaign on good governance was hinged on the slogan, “ Pag walang kurap, walang mahirap (if there is no corruption, there is no poverty).”

This anti-corruption campaign was supported by several studies – including a 2013 survey conducted by the Office of the Ombudsman, which showed that poverty exists partly because of corruption .

Similarly, a report by the World Bank in 2001 said that fighting corruption results in poverty reduction, better delivery of social services, and quality infrastructure.

Research we conducted on corruption in the Philippines and its impact on the economy, businesses, social services, citizen participation in reporting bribes, and being party to bribery yielded the following:

1. The Philippines lost $410.5 billion between 1960 and 2011 on illicit activities

According to a 2014 report by Global Financial Integrity , the Philippines lost about $410.5 billion between 1960 and 2011 on illicit financial flow. In current exchange rates, the amount is about P19.34 trillion (without accounting for inflation).

The vast majority of money flowing illegally into and out of the Philippines over the 52-year time span was done mostly through misinvoicing of trade. The table below shows how much money the government lost between 1960 and 2011:

In effect, the P19.34 trillion lost to corruption could have been used for education, health or infrastructure. In the 2016 national budget, this amount is:

- 154 times the budget for health (P125.4 billion)

- 52 times the budget for social protection (P370.4 billion)

- 39 times the budget for education (P490.6 billion)

- 25 times the budget for infrastructure (P759.58 billion)

2. $1 of every $4 goes unreported to Customs officials

In terms of lost revenue, the Bureau of Customs tops the list.

According to Global Financial Integrity, money flowing illicitly into the country takes away 25% of the value of all goods as $1 in every $4 goes unreported to Customs officials.

Since 2000, illicit financial flows have cheated the government of an average of $1.46 billion in tax revenue each year or about P68.8 billion in current rates.

To put that amount into perspective, the Philippines lost $3.85 billion in tax revenues in 2011 (P166.74 billion in 2011 rates) which is about 10% of the national budget that same year.

3. The Philippines ranks 95th in the global corruption perception index

Apart from grave impact on the fiscal arena, corruption affects the business climate.

According to anti-graft watchdog Transparency International (TI), the Philippines slid in its annual corruption perception ranking. With a score of 35 out of a possible 100, the country currently ranks 95th among 168 countries surveyed, according to expert opinion.

In 2014, the Philippines ranked 85th out of 175 countries, 10 notches higher than the current rank. The country got a score of 38 out of 100.

Over the years, trust in the public sector seems to have improved based on TI’s data. According to the report , poor results are attributed to promises yet to be fulfilled and corruption efforts undermined.

There were other issues that put the government in a bad light, such as the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP) and the reported delay in aid to victims of Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan). (READ: What stats, surveys say about Aquino’s fight vs corruption )

4. In ASEAN, the Philippines is perceived as the 5th least corrupt nation

Compared to Southeast Asian neighbors, the Philippines currently is the 5th least corrupt nation among 10 member-states in the region.

This is particularly important as these numbers determine how attractive the country is to investors.

In 2014, the Philippines tied with Thailand as the 3rd least corrupt nation in the region. It was when the country attained its highest rank in the past decade.

Back in 2008, the Philippines used to be the 4th most corrupt nation when it experienced its lowest dip in rankings. At the time, alleged corruption during the term of former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo hit an all-time high. (READ: TIMELINE: Gloria Arroyo – from plunder to acquittal )

Throughout the decade, Singapore has remained to be the perceived as corrupt-free not only within Southeast Asia, but around the world. It topped the rankings in 2010.

5. Filipino executives still think that the Bureau of Customs is the most corrupt government agency

Likewise, corruption affects ease of doing business.

The results of the 2014/2015 Social Weather Stations Survey of Enterprises on Corruption showed that 32% of Filipino executives surveyed said they have personal knowledge of corrupt transactions with the government.

Among agencies, Filipino businessmen still think that the Bureau of Customs is the most corrupt. The BOC received a sincerity rating of -55 from -65 in 2013. Despite the improvement, it was the only agency with a “very bad” rating in its “sincerity” in fightiing corruption.

The SWS terminology for net sincerity ratings are the following: excellent +70 and up; very good +50 to +69; good +30 to +49; moderate +10 to +29; neutral -9 to +9; poor -29 to -10; bad -49 to -30; and very bad, -69 to -50.

6. Less Filipino businessmen engage in corrupt transactions

According to a 2014/2015 SWS poll , less Filipino executives were asked for bribes during transactions. The number fell from 50% in 2012 to 44% in 2013 and 2014/2015.

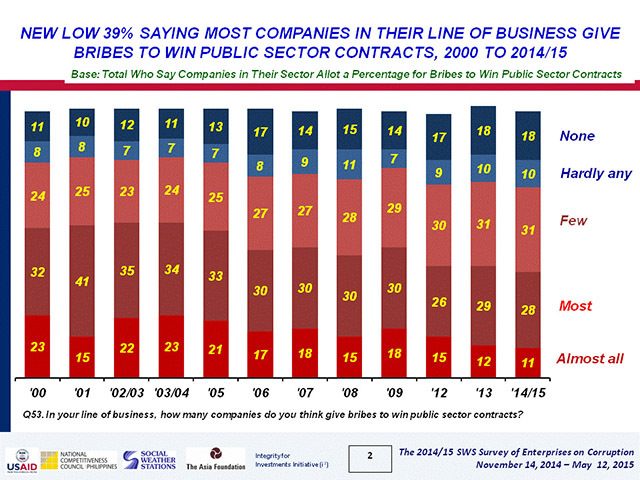

Results also showed that 28% of the respondents said most companies in their line of business gave bribes to win private sector contracts.

According to the poll, more businessmen think that the government does not punish corrupt officials. Only 11% of the respondents believe that the government often or almost always punishes corrupt officials, from 20% in 2013 and 27% in 2012.

However, 57% said that corrupt executives in their own sector of business are often punished. In the same 2014/2015 poll, of those solicited for bribes, only 13% admitted paying the bribe and reported the incident.

Overall, 64% of those surveyed were satisfied with the national government’s performance in promoting a good business climate but lower than 2013’s record of 70%.

7. One out of 20 families engages in bribery

Apart from businesses, data show that families and individuals take part in dishonest transactions as well.

In a 2013 survey , the Office of the Ombudsman found that one in every 20 Filipino families paid a bribe or grease money when transacting with a government agency.

Compared to a similar survey by the Philippine Statistics Authority in 2010, fewer families paid a bribe in 2013. The earlier survey found that two in every 20 families gave grease money.

Results showed that agencies involved in the delivery of basic social services are more vulnerable to corruption. Despite the decrease in participation in bribery, more families paid bribes when availing of social services. In 2010, the percentage of families who paid bribes was 4.1%; this increased to 4.5% by 2013.

Ironically, poor families are more likely to pay bribes just to have access to basic services, the poll revealed.

8. More Filipinos report corrupt practices to authorities

Despite the aggressive anti-corruption drive of the government, the Ombudsman found that the number of families that reported bribery incidents to public authorities is still low.

The 2013 survey said that 5.3% of the families who experienced being solicited for bribes reported the incident. This figure is almost 7 times the percentage of families in 2010.

The most cited reason for non-reporting is the amount being asked is too small to bother about. Other reasons were fear of reprisal and lack of time to report. – with Denise Nacnac/ Rappler.com

*2016 $1 = P47.11, 2011 $1 = P43.31

Sources: Office of the Ombudsman, Transparency International, Global Financial Integrity

Denise Nacnac is a Rappler intern

Have you ever been asked to give a bribe? Email details to [email protected] . It will help if you send supporting documents and contact information so we can reach you in case we need more details.

You may also report using the form below

Encourage your friends to join and become integrity champions by sharing this link on Facebook and Twitter.

Would you like to help validate reports? Email us via [email protected] so we can invite you to the validation workshops!

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended Stories

{{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}, finance industry, inside the alleged ponzi scheme preying on the rich.

How long can you go cashless? Filipinos last for 10 days on average

Going digital: 1 in 3 believe Philippines will be a cashless society by 2030

Visa names Maya as top prepaid card issuer in the Philippines once more

[ANALYSIS] Rule of 120: A practical method of asset allocation and minimizing investment risk exposure

![essay about graft and corruption in the philippines [ANALYSIS] Rule of 120: A practical method of asset allocation and minimizing investment risk exposure](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-rule-120-02222024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=274px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

Desktop menu

Mobile menu, graft gobbles 20% of the philippines’ budget.

Published: 19 August 2019

Philippines: Office of the Ombudsman (Photo: Judgefloro)

By Zdravko Ljubas

Corruption eats up US$13.35 billion, or 20% of the Philippines' budget every year, the country’s Deputy Ombudsman Cyril Ramos said on Thursday.

The figure, as he stressed, is equivalent to some 1.4 million houses for the poor, medical assistance for around seven million Filipinos, or a rice stock that can last for more than a year.

“With that amount, no Filipino would get hungry,” Ramos said.

Therefore, he added, it is not a surprise that the Philippines is ranked the sixth most corrupt Asia Pacific country.

“We need to keep reminding ourselves how destructive corruption is, especially for developing countries like ours,” Ramos said, addressing the National Police Commission’s summit on crime prevention, which gathered government agencies’ officials and representatives of community sectors to discuss how to fight crime, including corruption, more effectively.

Vice Chairman of the Commission Rogelio Casurao said he hopes that the results of the summit will help rationalize the framework for crime prevention for the next three years of the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte.

Duterte has been committed to violent response to crime since he took the office in 2016.

He has overseen the killing of as many as 12,000 alleged drug users. The statistics are hard to pin down because Duterte’s National Police suppress all critical reports and are spared from any accountability or legal consequences for a campaign that has left bodies in the streets.

Duterte has so far fired dozens of the country’s officials suspected of corruption and his anti-graft commission (PAGC) recently launched an investigation into two members of his cabinet.

Illegal drugs, robbery and theft, according to Rogelio Casuaro , remain the top crimes in the country and are met with lack of “cooperation and coordination among state agencies.”

Limited resources and funds, as well as lack of prosecutors to work on criminal cases, Casuaro said, add to the problem, especially having in mind that some 85% of court cases in the country are criminal in nature, according to Deputy Court Administrator of the Supreme Court Raul Villanueva.

With an average score of just 36 out of 100, the Philippines, according to Transparency International , still makes little progress in fighting graft, which places it in 99th place on the 180-country list.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter!

And get our latest investigations on organized crime and corruption delivered straight to your inbox.

Your cookie preferences

We use cookies to improve your experience by storing data about your preferences, your device or your browsing session. We also use cookies to collect anonymized data about your behaviour on our websites, and to understand how we can best improve our services. To find our more details, view our Cookie Policy .

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

NCJRS Virtual Library

What are we in power for the sociology of graft and corruption, additional details.

Box 154 , Manila D-406 Philippines , Philippines

No download available

Availability, related topics.

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Corruption — The Problem of Corruption and Its Examples in Philippines

The Problem of Corruption and Its Examples in Philippines

- Categories: Corruption Political Corruption

About this sample

Words: 979 |

Published: Mar 19, 2020

Words: 979 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Government & Politics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 907 words

2.5 pages / 1213 words

5 pages / 2353 words

1 pages / 521 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Corruption

Corruption in Kenya is a deeply entrenched and complex issue that has long plagued the nation's development and progress. This essay delves into the intricate layers of corruption, its causes, manifestations, and the efforts [...]

Crime fiction has a profound influence on public perceptions of law enforcement, serving as a medium through which readers engage with the intricacies of the criminal justice system. By portraying characters and institutions in [...]

Police corruption is a complex and pervasive issue that has serious implications for the criminal justice system and society as a whole. In this essay, we have explored the various factors that contribute to police corruption, [...]

Animal Farm, written by George Orwell, is a classic novel that uses the allegory of farm animals to explore the corrupting influence of power and the dangers of totalitarianism. This essay will provide a moral analysis of Animal [...]

It is a necessary ethnical appropriate and a primary leader concerning human then financial improvement on someone u . s . . it no longer only strengthens personal honor but additionally shapes the society between who we live. [...]

The purpose of this argumentative essay is to demonstrate that police brutality and police corruption are correlated. Most discussions on police brutality link it to racism/racial bias. This argument builds on the understanding [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Toggle Accessibility Statement

- Skip to Main Content

Republic of the Philippines National Council on Disability Affairs Pambansang Sanggunian Ukol sa Ugnayang Pangmaykapansanan

Total registered persons with disabilities (april 12, 2024), anti-graft and corrupt practices act – ra 3019.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled:

Section 1. Statement of policy. It is the policy of the Philippine Government, in line with the principle that a public office is a public trust, to repress certain acts of public officers and private persons alike which constitute graft or corrupt practices or which may lead thereto.

Section 2. Definition of terms. As used in this Act, that term

(a) “Government” includes the national government, the local governments, the government-owned and government-controlled corporations, and all other instrumentalities or agencies of the Republic of the Philippines and their branches.

(b) “Public officer” includes elective and appointive officials and employees, permanent or temporary, whether in the classified or unclassified or exempt service receiving compensation, even nominal, from the government as defined in the preceding subparagraph.

(c) “Receiving any gift” includes the act of accepting directly or indirectly a gift from a person other than a member of the public officer’s immediate family, in behalf of himself or of any member of his family or relative within the fourth civil degree, either by consanguinity or affinity, even on the occasion of a family celebration or national festivity like Christmas, if the value of the gift is under the circumstances manifestly excessive.

(d) “Person” includes natural and juridical persons, unless the context indicates otherwise.

Section 3. Corrupt practices of public officers. In addition to acts or omissions of public officers already penalized by existing law, the following shall constitute corrupt practices of any public officer and are hereby declared to be unlawful:

(a) Persuading, inducing or influencing another public officer to perform an act constituting a violation of rules and regulations duly promulgated by competent authority or an offense in connection with the official duties of the latter, or allowing himself to be persuaded, induced, or influenced to commit such violation or offense.

(b) Directly or indirectly requesting or receiving any gift, present, share, percentage, or benefit, for himself or for any other person, in connection with any contract or transaction between the Government and any other part, wherein the public officer in his official capacity has to intervene under the law.

(c) Directly or indirectly requesting or receiving any gift, present or other pecuniary or material benefit, for himself or for another, from any person for whom the public officer, in any manner or capacity, has secured or obtained, or will secure or obtain, any Government permit or license, in consideration for the help given or to be given, without prejudice to Section thirteen of this Act.

(d) Accepting or having any member of his family accept employment in a private enterprise which has pending official business with him during the pendency thereof or within one year after its termination.

(e) Causing any undue injury to any party, including the Government, or giving any private party any unwarranted benefits, advantage or preference in the discharge of his official administrative or judicial functions through manifest partiality, evident bad faith or gross inexcusable negligence. This provision shall apply to officers and employees of offices or government corporations charged with the grant of licenses or permits or other concessions.

(f) Neglecting or refusing, after due demand or request, without sufficient justification, to act within a reasonable time on any matter pending before him for the purpose of obtaining, directly or indirectly, from any person interested in the matter some pecuniary or material benefit or advantage, or for the purpose of favoring his own interest or giving undue advantage in favor of or discriminating against any other interested party.

(g) Entering, on behalf of the Government, into any contract or transaction manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to the same, whether or not the public officer profited or will profit thereby.

(h) Director or indirectly having financing or pecuniary interest in any business, contract or transaction in connection with which he intervenes or takes part in his official capacity, or in which he is prohibited by the Constitution or by any law from having any interest.

(i) Directly or indirectly becoming interested, for personal gain, or having a material interest in any transaction or act requiring the approval of a board, panel or group of which he is a member, and which exercises discretion in such approval, even if he votes against the same or does not participate in the action of the board, committee, panel or group.

Interest for personal gain shall be presumed against those public officers responsible for the approval of manifestly unlawful, inequitable, or irregular transaction or acts by the board, panel or group to which they belong.

(j) Knowingly approving or granting any license, permit, privilege or benefit in favor of any person not qualified for or not legally entitled to such license, permit, privilege or advantage, or of a mere representative or dummy of one who is not so qualified or entitled.

(k) Divulging valuable information of a confidential character, acquired by his office or by him on account of his official position to unauthorized persons, or releasing such information in advance of its authorized release date.

The person giving the gift, present, share, percentage or benefit referred to in subparagraphs (b) and (c); or offering or giving to the public officer the employment mentioned in subparagraph (d); or urging the divulging or untimely release of the confidential information referred to in subparagraph (k) of this section shall, together with the offending public officer, be punished under Section nine of this Act and shall be permanently or temporarily disqualified in the discretion of the Court, from transacting business in any form with the Government.

Section 4. Prohibition on private individuals. (a) It shall be unlawful for any person having family or close personal relation with any public official to capitalize or exploit or take advantage of such family or close personal relation by directly or indirectly requesting or receiving any present, gift or material or pecuniary advantage from any other person having some business, transaction, application, request or contract with the government, in which such public official has to intervene. Family relation shall include the spouse or relatives by consanguinity or affinity in the third civil degree. The word “close personal relation” shall include close personal friendship, social and fraternal connections, and professional employment all giving rise to intimacy which assures free access to such public officer.

(b) It shall be unlawful for any person knowingly to induce or cause any public official to commit any of the offenses defined in Section 3 hereof.

Section 5. Prohibition on certain relatives. It shall be unlawful for the spouse or for any relative, by consanguinity or affinity, within the third civil degree, of the President of the Philippines, the Vice-President of the Philippines, the President of the Senate, or the Speaker of the House of Representatives, to intervene, directly or indirectly, in any business, transaction, contract or application with the Government: Provided, That this section shall not apply to any person who, prior to the assumption of office of any of the above officials to whom he is related, has been already dealing with the Government along the same line of business, nor to any transaction, contract or application already existing or pending at the time of such assumption of public office, nor to any application filed by him the approval of which is not discretionary on the part of the official or officials concerned but depends upon compliance with requisites provided by law, or rules or regulations issued pursuant to law, nor to any act lawfully performed in an official capacity or in the exercise of a profession.

Section 6. Prohibition on Members of Congress. It shall be unlawful hereafter for any Member of the Congress during the term for which he has been elected, to acquire or receive any personal pecuniary interest in any specific business enterprise which will be directly and particularly favored or benefited by any law or resolution authored by him previously approved or adopted by the Congress during the same term.

The provision of this section shall apply to any other public officer who recommended the initiation in Congress of the enactment or adoption of any law or resolution, and acquires or receives any such interest during his incumbency.

It shall likewise be unlawful for such member of Congress or other public officer, who, having such interest prior to the approval of such law or resolution authored or recommended by him, continues for thirty days after such approval to retain such interest.

Section 7. Statement of assets and liabilities. Every public officer, within thirty days after the approval of this Act or after assuming office, and within the month of January of every other year thereafter, as well as upon the expiration of his term of office, or upon his resignation or separation from office, shall prepare and file with the office of the corresponding Department Head, or in the case of a Head of Department or chief of an independent office, with the Office of the President, or in the case of members of the Congress and the officials and employees thereof, with the Office of the Secretary of the corresponding House, a true detailed and sworn statement of assets and liabilities, including a statement of the amounts and sources of his income, the amounts of his personal and family expenses and the amount of income taxes paid for the next preceding calendar year: Provided, That public officers assuming office less than two months before the end of the calendar year, may file their statements in the following months of January.

Section 8. Dismissal due to unexplained wealth. If in accordance with the provisions of Republic Act Numbered One thousand three hundred seventy-nine, a public official has been found to have acquired during his incumbency, whether in his name or in the name of other persons, an amount of property and/or money manifestly out of proportion to his salary and to his other lawful income, that fact shall be a ground for dismissal or removal. Properties in the name of the spouse and unmarried children of such public official may be taken into consideration, when their acquisition through legitimate means cannot be satisfactorily shown. Bank deposits shall be taken into consideration in the enforcement of this section, notwithstanding any provision of law to the contrary.

Section 9. Penalties for violations. (a) Any public officer or private person committing any of the unlawful acts or omissions enumerated in Sections 3, 4, 5 and 6 of this Act shall be punished with imprisonment for not less than one year nor more than ten years, perpetual disqualification from public office, and confiscation or forfeiture in favor of the Government of any prohibited interest and unexplained wealth manifestly out of proportion to his salary and other lawful income.

Any complaining party at whose complaint the criminal prosecution was initiated shall, in case of conviction of the accused, be entitled to recover in the criminal action with priority over the forfeiture in favor of the Government, the amount of money or the thing he may have given to the accused, or the value of such thing.

(b) Any public officer violation any of the provisions of Section 7 of this Act shall be punished by a fine of not less than one hundred pesos nor more than one thousand pesos, or by imprisonment not exceeding one year, or by both such fine and imprisonment, at the discretion of the Court.

The violation of said section proven in a proper administrative proceeding shall be sufficient cause for removal or dismissal of a public officer, even if no criminal prosecution is instituted against him.

Section 10. Competent court. Until otherwise provided by law, all prosecutions under this Act shall be within the original jurisdiction of the proper Court of First Instance.

Section 11. Prescription of offenses. All offenses punishable under this Act shall prescribe in ten years.

Section 12. Termination of office. No public officer shall be allowed to resign or retire pending an investigation, criminal or administrative, or pending a prosecution against him, for any offense under this Act or under the provisions of the Revised Penal Code on bribery.

Section 13. Suspension and loss of benefits. Any public officer against whom any criminal prosecution under a valid information under this Act or under the provisions of the Revised Penal Code on bribery is pending in court, shall be suspended from office. Should he be convicted by final judgment, he shall lose all retirement or gratuity benefits under any law, but if he is acquitted, he shall be entitled to reinstatement and to the salaries and benefits which he failed to receive during suspension, unless in the meantime administrative proceedings have been filed against him.

Section 14. Exception. Unsolicited gifts or presents of small or insignificant value offered or given as a mere ordinary token of gratitude or friendship according to local customs or usage, shall be excepted from the provisions of this Act.

Nothing in this Act shall be interpreted to prejudice or prohibit the practice of any profession, lawful trade or occupation by any private person or by any public officer who under the law may legitimately practice his profession, trade or occupation, during his incumbency, except where the practice of such profession, trade or occupation involves conspiracy with any other person or public official to commit any of the violations penalized in this Act.

Section 15. Separability clause. If any provision of this Act or the application of such provision to any person or circumstances is declared invalid, the remainder of the Act or the application of such provision to other persons or circumstances shall not be affected by such declaration.

Section 16. Effectivity. This Act shall take effect on its approval, but for the purpose of determining unexplained wealth, all property acquired by a public officer since he assumed office shall be taken into consideration.

Approved: August 17, 1960

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Country Awash in Violence Backs Its Leader’s Hard-Line Stance

Voters in Ecuador gave their new president, Daniel Noboa, who deployed the military to fight gangs in January, even more powers.

By Genevieve Glatsky

Ecuadoreans voted on Sunday to give their new president more powers to combat the country’s plague of drug-related gang violence, officials said, supporting his hard-line stance on security and offering an early glimpse of how he might fare in his bid for re-election next year.

President Daniel Noboa, the 36-year-old heir to a banana empire, took office in November after an election season focused on the violence , which has surged to levels not seen in decades. In January, he declared an “internal armed conflict ” and ordered the military to “neutralize” the country’s gangs. The move allowed soldiers to patrol the streets and Ecuador’s prisons, many of which have come under gang control .

In a referendum on Sunday, Ecuadoreans voted to enshrine the increased military presence into law and to lengthen prison sentences for certain offenses linked to organized crime, among other security measures. With about 20 percent of the votes counted on Sunday night, Ecuador’s electoral authority declared that the trend toward approval of the security measures was “irreversible,” though voters rejected other proposals on the ballot.

Mr. Noboa claimed victory on social media. “I apologize for jumping the gun on a triumph that I cannot help but celebrate,” he wrote on X .

A flood of violence from international criminal groups and local gangs has turned Ecuador, a country of 17 million, into a key player in the global drug trade. Tens of thousands of Ecuadoreans have fled to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Experts saw the results of the voting Sunday as an indicator of how strongly the public supported Mr. Noboa’s stance on crime. “What is clear is that the people are saying ‘yes’ to the security model,” said an Ecuadorean political analyst, Caroline Ávila. She said the voters also had “high expectations” that the crime problem “will be solved.”

Mr. Noboa, who is expected to seek a second term in February, has high approval ratings , though they have slipped lately. He became president after his predecessor, Guillermo Lasso, facing impeachment proceedings over embezzlement accusations, called for early elections; Mr. Noboa is in office until May 2025, the remainder of Mr. Lasso’s term.

Some human rights groups have criticized Mr. Noboa’s anticrime tactics as going too far, saying they have led to abuses in prisons and in the streets. Still, most Ecuadoreans seem willing to accept Mr. Noboa’s strategy if they think it makes them safer, analysts said.

“Noboa is now one of the most popular presidents in the region,” said Glaeldys González, who researches Ecuador for the International Crisis Group. “He is taking advantage of those levels of popularity that he currently has to catapult himself to the presidential elections.”

He deployed the military against the gangs in response to a turning point in Ecuador’s long-running security crisis : Gangs attacked the large coastal city of Guayaquil after the authorities moved to take charge of Ecuador’s prisons.

Mr. Noboa’s deployment of the military was followed by a decline in violence and a precarious sense of safety, but the stability did not last. Over the Easter holiday this month, there were 137 murders in Ecuador, and kidnappings and extortion have been increasing .

Two weeks ago, Mr. Noboa took the extraordinary step of arresting an Ecuadorean politician who had taken refuge at the Mexican Embassy in Quito, in what experts called a violation of an international treaty on the sanctity of diplomatic posts. The move, which drew condemnation across the region, sent a message in line with Mr. Noboa’s heavy-handed approach to violence and graft.

Mr. Noboa said he had sent police officers into the embassy to arrest Jorge Glas , a former vice president who had been convicted of corruption, because Mexico had abused the immunities and privileges granted to the diplomatic mission. Mr. Noboa said Mr. Glas was not entitled to protection because he was a convicted criminal.

Taken together, the raid and the deployment of the military were meant to show that Mr. Noboa is tough on crime and impunity, political analysts say. Though polls show that Mr. Noboa’s approval rating has fallen in recent months, it remains high, at 67 percent.

Voter turnout on Sunday was 72 percent, according to the country’s electoral authority. Analysts considered that low, in a country where voting is mandatory and turnout usually exceeds 80 percent.

Just as voters were heading to the polls, they received another reminder of the surge in violence, as the authorities announced that the head of a prison in Manabí, a coastal province that has become a hub for transnational crime, had been killed.

Some proposals from Mr. Noboa’s government that were unrelated to security were voted down on Sunday. Ecuadoreans voted against one that would have legalized hourly employment contracts, which are currently prohibited. Labor unions say employers could use them to undermine workers’ rights and essentially pay lower salaries than the law requires. A proposal that would have allowed international arbitration of commercial disputes was also voted down.

But analysts said the overall result yielded a robust mandate for Mr. Noboa. Ms. González said it would “help the government argue that it needs more time in power to continue with these changes and these reforms in its general fight against organized crime.”

The results of the referendum are binding, and the national assembly has 60 days to pass them into law.

Some analysts said the referendum results had more to do with Mr. Noboa’s popularity than with whether the security measures were likely to be effective.

“We do not vote for the question; rather, we vote for who asked the question,” said Fernando Carrión, who studies violence and drug trafficking at the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences, a regional research and analysis group.

He added that measures like increasing prison sentences were likely to exacerbate the problems of overcrowding and violence in prisons.

Despite the tumultuous few weeks that preceded the voting, some voters said they were undeterred.

“I am going to vote ‘yes’ in this referendum because I am convinced that it is the only way for Ecuador to have a change, and we can all have a better future,” said Susana Chejín, 62, a resident of the southern city of Loja.

“He is making good changes for the country, to fight crime and drug trafficking,” she said of Mr. Noboa.

Others said they thought the questions on the referendum were not enough to address the country’s insecurity.

“We are still in the vicious circle of focusing on the symptoms and not on the causes,” said Juan Diego Del Pozo, 31, a photographer in Quito. “No question aims to solve structural problems, such as inequality. My vote will be a resounding ‘no’ on every question.”

Thalíe Ponce contributed reporting from Guayaquil, Ecuador, and José María León Cabrera from Quito, Ecuador.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Philippine government is directed to maintain honesty and integrity in the public service, and to take action against graft and corruption (Section 27, Art. II). It is also directed to give full public disclosure of all transactions involving the public interest (Section 28, Art. II).

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 02:01 AM March 13, 2023. The Philippines is perceived to be one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Of 180 countries, the Philippines ranked 116 in terms of ...

Donor agencies are also actively involved in building capacity to curb corruption in the Philippines. The success of these initiatives, however, is far from guaranteed and many observers believe that structural obstacles such as entrenched cronyism continue to undermine anti-corruption efforts. 18 August 2009 Updated 12 September 2023.

The Philippines suffers from widespread corruption, which developed during the Spanish colonial period. According to GAN Integrity's Philippines Corruption Report updated May 2020, the Philippines suffers from many incidents of corruption and crime in many aspects of civic life and in various sectors. Such corruption risks are rampant throughout the state's judicial system, police service ...

Corruption is a significant obstacle to good governance in the Philippines. A review of recent literature suggests that all levels of corruption, from petty bribery to grand corruption, patronage and state capture, exist in the Philippines at a considerable scale and scope. Significant efforts have been made to combat corruption, which include ...

The Philippines has a comprehensive set of laws that may have identified all the possible instances of graft and corruption that can be devised. The anti-corruption agencies have been given ample powers to identify and punish offenders. Special agencies devoted to rooting out government corruption have emphasized both prevention and punishment.

SUBSCRIBE TO EMAIL ALERTS. Daily Updates of the Latest Projects & Documents. This report collects and presents available information about corruption issues facing the Philippines, ongoing anticorruption efforts in and outside the government, and .

The research analysis of graft and corruption has been widely studied and described as social cancer in the political structure and process of the Philippine society. It has been identified within ...

Abstract. Upon the suggestion of financing institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, corruption has taken centre stage in policy discourse, making corruption the locus of many re-engineering efforts in Philippine governance (Transparency and Accountability Network, internal documents, 2005).

The research analysis of graft and corruption has been widely studied and described as the social cancer in the political structure and process of the Philippine society. It has been identified within the realm of political corruption that deterred the economic growth and development as the main cause of underdevelopment in developing countries in Asia and Africa. This study is a culture-based ...

Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. attends his mother Imelda Marcos's 90th birthday celebration in Manila, Philippines, on July 1, 2019. Artur Widak/NurPhoto via Getty Images. With Philippine ...

before the Philippine anti-graft court known as Sandiganbayan for (i) receiving gifts and kickbacks from illegal gambling; (ii) converting and misusing a portion of tobacco excise tax share allocated ... graft and corruption for entering into a manifestly and grossly disadvantageous contract with a telecommunications firm for personal gain. She ...

To put that amount into perspective, the Philippines lost $3.85 billion in tax revenues in 2011 (P166.74 billion in 2011 rates) which is about 10% of the national budget that same year. 3. The ...

"graft and corruption." In much of the English literature on the sub ject, the single word "corruption" is used rather than the local compound "graft and corruption." We shall therefore use the first (corruption) tor its universal or general meaning and reserve the latter (graft and corruption) to refer specifically to the Philippine setting.

Trust and Governance in the Philippines and Singapore: A comparative Analysis. Jon T. S. Quah. Political Science. 2010. According to the 2007 World Bank governance indicators, the total percentile rank for Singapore is 514.8 while that for the Philippines is 216.3. Transparency International's 2008 Corruption….

Graft Gobbles 20% of the Philippines' Budget. Corruption eats up US$13.35 billion, or 20% of the Philippines' budget every year, the country's Deputy Ombudsman Cyril Ramos said on Thursday. The figure, as he stressed, is equivalent to some 1.4 million houses for the poor, medical assistance for around seven million Filipinos, or a rice ...

the extent of graft and corruption in the philippines is examined in view of the causes, prevalence, and consequences of these practices in the existing social context of the country. ... and lawlessness. thus, graft and corruption as a legal concept and standard of public morality are alien to filipinos who view such practices as a traditional ...

This paper argues that one effective strategy for tackling corruption in the Philippines is to more actively involve civil society groups in the governance of the country. This paper examines how this approach is effective for two major areas of corruption, election irregularities and the misuse of public funds by elected officials.

torical examination of graft and corruption in the Philippines should properly include a description of pre-conquest society. Of course, to the basic question of whether there was bureaucratic corruption at the time, one answer would simply be to dismiss it since the absence of a formal bureacracy logically pre cludes the existence of the ...

Duterte said in July corruption remained "deeply embedded" in government. Corruption reinforces poverty by diverting resources that could help the poor, which nearly roughly one fifth of the ...

The most famous case of corruption in the country was the "Pork Barrel Scam" which involved a businesswoman named Janet Napoles with numerous politicians accused of stealing $229 million worth of Philippine taxpayer money. This scheme was done by creating fake non-governmental organizations where money would enter and they her and ...

The answer to my question is very simple. The incidents of sin nowadays are very high, because the system itself is corrupt. It is a system that not only enables graft and corruption to prosper, it also allows the sinners to get away with their crimes. As a matter of fact, nobody really sees them as criminals nowadays.

Section 1. Statement of policy. It is the policy of the Philippine Government, in line with the principle that a public office is a public trust, to repress certain acts of public officers and private persons alike which constitute graft or corrupt practices or which may lead thereto. Section 2. Definition of terms. As used in this Act, that term.

Better Essays. 3534 Words. 15 Pages. Open Document. A. INTRODUCTION In 1988, graft and corruption in the Philippines was considered as the "biggest problem of all" by Jaime Cardinal Sin, the Archbishop of Manila. Then President Corazon C. Aquino likewise despaired that corruption has returned. In 1989, public perception was that "corrupt ...

First, the economic fallout of Lan's corruption case and the ongoing anti-corruption campaign is already being felt. Initially arrested on bond fraud charges, Lan's apprehension stirred panic ...

Karen Toro/Reuters. Ecuadoreans voted on Sunday to give their new president more powers to combat the country's plague of drug-related gang violence, officials said, supporting his hard-line ...