- Place order

Formal Analysis Paper Writing Guide

A formal analysis essay, aka a visual analysis essay , is an essay that is written to analyze a painting or a work of art. A properly written formal analysis paper will give the reader both objective and subjective information about an art piece.

This post will teach you the A to Z of how to write a formal analysis essay.

What is a formal analysis essay?

A formal analysis essay is an academic writing that comprehensively describes a work of art (usually a painting, image, or sculpture). An excellent formal analysis essay is one that not only describes a work of art but also analyzes it.

If you are enrolled in an art program in college or university, you will most likely have to complete a good number of formal or visual analysis essays before you graduate. They are common in art programs to help art students to understand and judge art better.

The 4 Main Steps for a Formal Analysis Essay

Every proper formal analysis essay must include four key elements – description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation. In other words, when writing a formal analysis essay, you must describe, analyze, interpret, and evaluate the work of art.

1. Description

The first thing you need to do when writing a formal analysis essay is to describe the elements of the work of art you see at first glance.

So what can you quickly notice about the work of art you want to analyze? What is it that has been depicted? What medium has the artist used? What painting element? Your answers to all these questions will help you to fully describe the work of art to the reader.

In your description of the work of art, there are several things you must strongly consider and describe.

- Texture : How does the artist use texture? Is it implied or actual?

- Color : How does the artist use colors? What color scheme? Is the image dark, medium, or light?

- Organizing space : How does the artist utilize perspective? Does the artist use linear perspective?

- Mass and volume : How does the artist represent mass and volume? Is the work of art one-dimensional, two-dimensional, or three-dimensional?

- Shape : How does the artist use shapes? Are the shapes soft or hard-edged? Are they small or large? How are the shapes related?

- Line : How does the artist use lines? Are they soft, jagged, straight, mechanical, or expressive? Are they used to describe space?

2. Analysis

The second thing you need to do when writing a formal analysis essay is to analyze the artistic elements of the work of art. This is where the rubber meets the road. It is where your inner artist must come out, and you must discuss the true art aspects of the work of art.

Once you have described the physical or first-glance elements of the artwork, you have to go straight into the analysis aspect. The analysis aspect is all about discussing how the artist employs design aspects in the artwork.

In your analysis of the work of art, there are several things you must strongly consider and analyze.

- Design : What principles of design (art techniques) does the artist use?

- Variety: What elements does the artist use, and how does he use them to provide variety?

- Scale : Is the work to scale? Are all the elements on the same scale?

- Symmetry : Is the work symmetrical or asymmetrical?

- Emphasis : What does the artist use to create emphasis? What movement does the work convey?

- Patterns : What patterns are clear in the artwork?

3. Interpretation

The third thing you need to do when writing a formal analysis essay is to reveal the hidden meanings or aspects of the work of art you are analyzing.

The interpretation part of your formal analysis essay should capture two things – the use of symbolism in the artwork and what it means to the viewer. It is all about revealing the hidden meaning of what may mean one thing at first glance and something deeper upon further inspection.

Interpretations of artworks usually reveal themselves somewhat slowly. This is because one has to look at an art object repeatedly to identify symbolism and get the deeper meaning.

When providing an interpretation for symbolism, you must provide supporting evidence.

4. Evaluation

The last thing you need to do when writing a formal analysis essay is to evaluate the work of art you have described, analyzed, and interpreted.

In the evaluation part of your visual analysis essay, you need to discuss your overall opinion of the artwork. Specifically, you need to discuss what you discovered about it and about yourself when examining it.

A proper evaluation of an art object will detail your opinion and feelings about it. It will also discuss whether you find it pleasing or engaging.

When evaluating an art piece, it is crucial to remember that it is best to evaluate art pieces per the period they were created. This allows for better contextualization and proper evaluation.

Format of Formal Analysis Paper

A typical formal analysis paper will have three key sections – an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Find out what each section entails in the visual analysis paper outline below.

1. Introduction

The first part of a formal analysis paper is the introduction. The introduction must provide the reader with all the essential information about the artwork to be analyzed. It must also be interesting enough to hook the reader.

The best way to provide the reader with all the essential information about the artwork to be analyzed is to describe it vividly. The vivid description should be followed by information about how the artwork was created and information about the creator.

An introduction with all the above information is sufficient to hook the reader's attention. Nevertheless, if there is something controversial about the artwork, this information must also be provided in the introduction. The purpose of giving this type of information is to ensure the reader is fully aware of all the crucial aspects of the art piece to be analyzed.

2. Thesis statement

A well-written visual analysis paper will have a thesis statement at the end of the introduction. The thesis statement must be clear, concise, and to the point. Moreover, it must quickly tell the reader the paper's main argument.

Think of the thesis statement of your formal analysis paper as your paper's central argument; the argument/claim you will be supporting during your analysis.

The body of a formal analysis essay is where the actual analysis happens. It must have four key elements for it to be considered complete. The elements are – description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation.

Each element is typically covered in a separate paragraph for good organization and flow. And it supports the thesis statement in the introduction section.

By the time the reader is done reading the body section of the essay, they should have all the art analysis they expected after reading the introduction.

4. Conclusion

The conclusion is the last part of every formal essay analysis. It is where the writer must nicely wrap up the art analysis. This is usually done by first restating the thesis and the main supporting statements. The restatement is frequently followed by information comparing the artwork with similar pieces or information about whether the artwork fits in with the creator's other artworks.

Steps for Writing a Formal Analysis Essay

As an art history student, it is essential to learn how to write a visual analysis paper. This is because you will most likely be asked to write such a paper several times before graduating. Moreover, learning how to write such a paper will also help you become a good art critic, curator, or appraiser.

Follow the steps below to write a brilliant visual analysis essay.

1. Gather general information about the artwork and the creator

The first thing to do to write a formal analysis essay is to gather general information about the artwork and the creator. The most crucial bits of information to collect include:

- The subject – what artwork will you be analyzing? What is it called, and when was it created?

- The creator – who is behind the art? Identify them by their full name.

- The date of creation – when was the artwork created? Is it typical art for the period and the artist?

- The location – where is the art being displayed? Has it been displayed somewhere else before?

- The medium and techniques – what medium was used to create the artwork? What techniques did the artist use?

2. Write the introduction

A good introduction paragraph to a formal analysis essay provides sufficient background information about the subject piece and grabs the reader's attention. Use the information you have gathered in the step above to write a good introduction.

Make your introduction brilliant by ensuring you provide information about the art piece in a logical and flowing manner. After writing your introduction, read it to ensure it can grab the reader's attention. If it can, you are good to go. If it can't, you should rewrite it until it can do so.

The last statement of your introduction paragraph should be your thesis statement (your central argument for the paper). It should quickly tell the reader your overall argument or opinion about the subject artwork. You can only develop a good thesis statement after researching a painting and finding out more about it and the period it was created. Researching an art piece will also help you describe and analyze it more objectively.

If, after writing your paper, you feel your thesis statement doesn't closely reflect its overall argument, you should rewrite the statement to make sure it does. It is totally okay to do so.

3. Describe the painting

After writing your introduction paragraph, you should write the body section of your paper. The body section of a typical formal analysis paper must have at least two distinct parts – the first part describing the painting and the second analyzing it. It can also have an interpretation part to discuss any symbolism or hidden meaning discovered in the art.

The best way to describe the subject painting is to provide all the visible information about it. The visible aspects of the artwork that you must capture in your description include:

- The figures – the characters displayed in the painting and their identities or what they represent.

- The theme – the story or theme depicted in the painting

- The setting – the background of the painting.

- The shapes and colors – the shapes and colors that stand out in the painting.

- The mood – the lighting and overall mood of the subject artwork.

Make sure your painting description is well-organized and has a good flow. If need be, rewrite it to enhance its flow.

Your description can be one paragraph long or two paragraphs long.

4. Analyze the painting

The second part of your paper's body section should be a detailed analysis of the subject painting. Your analysis should focus on the painting's art elements and design principles.

Your professor will most likely focus on the analysis part of your paper, so make sure you do a brilliant analysis. To ensure your professor is impressed with your painting analysis, you should analyze/discuss the art elements and the design principles separately.

The art elements of a painting are the painting techniques used. They are also known as the basics of composition. The art elements that shouldn't miss in your analysis include:

- The lines – what lines does the artist use? Are they implied, thick, curved, or straight? Talk about them in your paper.

- The shapes – what shapes does the artist use? Are they plain or hidden? Are they geometrical or out of proportion?

- The use of light – what is the light source in the painting? Is it obvious or hidden?

- The colors – what colors does the painter use? Are they primary or secondary colors? Is the tone cool or warm?

- The patterns – does the painting have distinct, repeated, textural, or hidden patterns? How do they make it look?

- The use of space – is the painting one-dimensional or two-dimensional? How does the artist show depth?

- The passage of time – how does the painting show the passage of time?

Remember, simply describing the art elements above is not enough. You must analyze them because this step is all about analysis; it is all about going deeper.

The design principles of a painting are the aspects of the painting that provide a thematic or broader perspective. Therefore, your inner artist should come out when analyzing the design principles of the painting.

The following things should feature in your analysis of the design principles of the painting:

- Symmetry and asymmetry – talk about the points of balance in the shapes, colors, patterns, and overall painting.

- Variety – talk about the varied techniques used by the artist and whether the overall feel is of chaos or unity.

- Emphasis – talk about the thematic and artistic points of focus. Mention the colors that the artist emphasizes.

- Proportions – discuss how the figures work together to depict the painting's volume, mass, and scale.

- Rhythm – discuss how the artist displays rhythm using figures and techniques.

Carefully and methodically detailing your analysis of the painting's art elements and design principles will help you to get a good grade in your visual analysis essay.

5. Write the conclusion

After describing and analyzing the painting, you should write the conclusion. A good visual or formal analysis essay conclusion provides an overall evaluation of the subject painting. The best way to write an overall evaluation of the subject painting is to think of the evaluation as your general assessment.

So what do you think of the painting based on your description and analysis? Is it standard, brilliant, or exceptional? Does it meet your expectations? Why yes or why not? Talk about these things in your conclusion to make it perfect.

6. Proofread and edit your essay

After writing your essay, you should proofread and edit it. Doing this will help you to transform it from ordinary to extraordinary.

The correct way to proofread your essay is to proofread it twice – first using a grammar checker like Grammarly and then using your own eyes.

Proofreading your paper using a grammar checker like Grammarly will help you quickly identify and edit basic grammar and typing errors. Proofreading your document one more time using your own eyes will help you to catch any mistakes the checker might have missed. It will also help you to identify and rewrite parts of your paper that are difficult to understand.

Your paper should be ready to submit after you proofread it as described above.

10 tips to help you write a brilliant formal analysis essay

Writing a visual analysis essay is not easy. This is because there are many things to include and consider to ensure the paper is complete. In this section, you will discover what you need to consider to ensure the final draft of your formal analysis essay is perfect.

- Consider your feelings. When analyzing a painting, it is crucial to be objective in your analysis. But at the same time, it is also vital to consider your feelings. All your feelings toward the painting are legitimate. Therefore, do not be afraid to say what you think about an artwork, especially in your analysis and conclusion. Your professor should be able to clearly see your judgment on the subject piece and not just your objective analysis.

- Focus on analysis. When most art students write a formal analysis essay, they spend a lot of time on the description rather than the analysis. This is wrong. It is okay for the first part of your analysis essay to include a description of the painting. However, at least 50 to 60 percent of your essay should be your analysis of the subject painting. Your professor expects this. So if you want to get a good grade, you should focus on analysis.

- Start with the obvious and go deeper. While it is true that a good formal analysis paper must focus on the analysis, a thorough description of the artwork is also a must. The first part of your paper's body section must be a detailed description of the subject painting. It is only after describing the artwork that you should proceed to analyze it. If you write your paper this way, your reader will know what exactly you are talking about in your analysis.

- Use the correct terms. You must use the correct terms to get a top grade when writing your visual analysis essay. This is because professors hate when students use non-official or inaccurate words to describe art elements. If you do not know the correct way to refer to an art element or design principle, you should search for it online in art term glossaries such as MOMA .

- Less is more. There are usually many art elements and design principles to consider when analyzing an art piece. However, discussing or describing all of them in your paper is not a must. Your analysis should focus on discussing the most significant art elements and design principles. You can, and you should, ignore all insignificant art elements and design principles.

- Proofread your work thoroughly. Many students ignore proofreading their papers before submission and end up submitting low-quality essays. You should not do the same. Instead, you should carefully proofread your work twice or thrice to remove all errors and mistakes. This will help you polish your essay to a level that is extremely easy to understand.

- See live artwork regularly. To write great visual analysis essays, you must visit art galleries, museums, and exhibitions frequently. Visiting such art establishments regularly will allow you to see, hear, and familiarize yourself with art critique. Of course, by familiarizing yourself with art critique, the exercise will become like second nature to you. Therefore, it will make it much easier for you to write great visual analysis essays.

- Consider audience and historical context. When analyzing art, you must strongly consider the audience and the historical context. Failure to do so will make your analysis shallow. Think of who the artist was trying to appeal to. Was he trying to appeal to the church? Art people? Or the masses? The target audience obviously influenced the way artists developed their paintings. Think also of the historical context. Judging a Renaissance period painter with Rococo era standards is not appropriate. You can only judge an art piece by the standards of the art period it was created.

Example of a formal or Visual or Formal Analysis Essay

The essay below is a short example of a formal analysis essay. It includes the three key sections of a formal analysis essay – introduction, body, and conclusion. Its body section consists of a brief description paragraph and a brief analysis paragraph.

Analysis of Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth

Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth is a chaotic oil on canvas painting by Englishman Joseph William Turner (1775- 1851, England). It is one of Turner's most famous paintings, and it is on display at Tate, one of the most important art organizations in the world. By looking at this painting, it is clear that Turner was a master at drawing abstract, chaotic paintings.

At first glance, this painting reveals a steamboat at the center of what looks like a storm. However, the painting is chaotic, so this is something one cannot tell for sure. Nevertheless, based on the title of the painting, one can see it is shaped like a steam-boat belching heavy smoke. The vessel is surrounded by swirling snow and pitching waves. The sky is somewhat depicted in blue despite the raging storm.

A closer inspection of the painting reveals a well-drawn chaotic artwork featuring long and heavy strokes. The long strokes create dramatic movement and enhance the artist's idea of a steamboat in a raging storm. It also reveals asymmetrical shapes, as is the case with most chaotic oil on canvas paintings.

In terms of design principles, the scale of the boat stands out. It looks somewhat tiny in the middle of a big storm. The tiny size of the vessel, plus the small indication of space above it created by a sliver of blue sky, indicates a scene of danger. The scene is reminiscent of humanity's struggle against powerful forces of nature.

This artwork by Turner is a beautiful work of art. Turner is considered one of the foremost painters of his time, and this work indeed shows that he was a master oil on canvas painter. The work depicts a boat in a big storm. It is a powerful reminder of humanity's struggle for survival in a cold and unforgiving world.

Final words

Professors and instructors know that formal analysis essay assignments help students to understand and judge art better. Because of this, they give such assignments from time to time. Therefore, if you are an art program student, you should learn how to do such assignments perfectly. Doing so will help you get an excellent grade whenever you are given such an assignment.

This post revealed everything crucial that you need to know to write a formal essay. The information includes the four steps for a formal analysis essay, the structure of a formal essay, and the steps to follow to write one. You can use the information to write a brilliant visual analysis essay on any work of art.

If the information is insufficient for you to write an excellent visual analysis essay or you are too busy to write one, you should work with us. If you do so, you will get 100% confidentiality, 100% quality, and 100% on-time delivery. Try Essay Maniacs today for quality assignment help !

Need a Discount to Order?

15% off first order, what you get from us.

Plagiarism-free papers

Our papers are 100% original and unique to pass online plagiarism checkers.

Well-researched academic papers

Even when we say essays for sale, they meet academic writing conventions.

24/7 online support

Hit us up on live chat or Messenger for continuous help with your essays.

Easy communication with writers

Order essays and begin communicating with your writer directly and anonymously.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing Essays in Art History

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Art History Analysis – Formal Analysis and Stylistic Analysis

Typically in an art history class the main essay students will need to write for a final paper or for an exam is a formal or stylistic analysis.

A formal analysis is just what it sounds like – you need to analyze the form of the artwork. This includes the individual design elements – composition, color, line, texture, scale, contrast, etc. Questions to consider in a formal analysis is how do all these elements come together to create this work of art? Think of formal analysis in relation to literature – authors give descriptions of characters or places through the written word. How does an artist convey this same information?

Organize your information and focus on each feature before moving onto the text – it is not ideal to discuss color and jump from line to then in the conclusion discuss color again. First summarize the overall appearance of the work of art – is this a painting? Does the artist use only dark colors? Why heavy brushstrokes? etc and then discuss details of the object – this specific animal is gray, the sky is missing a moon, etc. Again, it is best to be organized and focused in your writing – if you discuss the animals and then the individuals and go back to the animals you run the risk of making your writing unorganized and hard to read. It is also ideal to discuss the focal of the piece – what is in the center? What stands out the most in the piece or takes up most of the composition?

A stylistic approach can be described as an indicator of unique characteristics that analyzes and uses the formal elements (2-D: Line, color, value, shape and 3-D all of those and mass).The point of style is to see all the commonalities in a person’s works, such as the use of paint and brush strokes in Van Gogh’s work. Style can distinguish an artist’s work from others and within their own timeline, geographical regions, etc.

Methods & Theories To Consider:

Expressionism

Instructuralism

Postmodernism

Social Art History

Biographical Approach

Poststructuralism

Museum Studies

Visual Cultural Studies

Stylistic Analysis Example:

The following is a brief stylistic analysis of two Greek statues, an example of how style has changed because of the “essence of the age.” Over the years, sculptures of women started off as being plain and fully clothed with no distinct features, to the beautiful Venus/Aphrodite figures most people recognize today. In the mid-seventh century to the early fifth, life-sized standing marble statues of young women, often elaborately dress in gaily painted garments were created known as korai. The earliest korai is a Naxian women to Artemis. The statue wears a tight-fitted, belted peplos, giving the body a very plain look. The earliest korai wore the simpler Dorian peplos, which was a heavy woolen garment. From about 530, most wear a thinner, more elaborate, and brightly painted Ionic linen and himation. A largely contrasting Greek statue to the korai is the Venus de Milo. The Venus from head to toe is six feet seven inches tall. Her hips suggest that she has had several children. Though her body shows to be heavy, she still seems to almost be weightless. Viewing the Venus de Milo, she changes from side to side. From her right side she seems almost like a pillar and her leg bears most of the weight. She seems be firmly planted into the earth, and since she is looking at the left, her big features such as her waist define her. The Venus de Milo had a band around her right bicep. She had earrings that were brutally stolen, ripping her ears away. Venus was noted for loving necklaces, so it is very possibly she would have had one. It is also possible she had a tiara and bracelets. Venus was normally defined as “golden,” so her hair would have been painted. Two statues in the same region, have throughout history, changed in their style.

Compare and Contrast Essay

Most introductory art history classes will ask students to write a compare and contrast essay about two pieces – examples include comparing and contrasting a medieval to a renaissance painting. It is always best to start with smaller comparisons between the two works of art such as the medium of the piece. Then the comparison can include attention to detail so use of color, subject matter, or iconography. Do the same for contrasting the two pieces – start small. After the foundation is set move on to the analysis and what these comparisons or contrasting material mean – ‘what is the bigger picture here?’ Consider why one artist would wish to show the same subject matter in a different way, how, when, etc are all questions to ask in the compare and contrast essay. If during an exam it would be best to quickly outline the points to make before tackling writing the essay.

Compare and Contrast Example:

Stele of Hammurabi from Susa (modern Shush, Iran), ca. 1792 – 1750 BCE, Basalt, height of stele approx. 7’ height of relief 28’

Stele, relief sculpture, Art as propaganda – Hammurabi shows that his law code is approved by the gods, depiction of land in background, Hammurabi on the same place of importance as the god, etc.

Top of this stele shows the relief image of Hammurabi receiving the law code from Shamash, god of justice, Code of Babylonian social law, only two figures shown, different area and time period, etc.

Stele of Naram-sin , Sippar Found at Susa c. 2220 - 2184 bce. Limestone, height 6'6"

Stele, relief sculpture, Example of propaganda because the ruler (like the Stele of Hammurabi) shows his power through divine authority, Naramsin is the main character due to his large size, depiction of land in background, etc.

Akkadian art, made of limestone, the stele commemorates a victory of Naramsin, multiple figures are shown specifically soldiers, different area and time period, etc.

Iconography

Regardless of what essay approach you take in class it is absolutely necessary to understand how to analyze the iconography of a work of art and to incorporate into your paper. Iconography is defined as subject matter, what the image means. For example, why do things such as a small dog in a painting in early Northern Renaissance paintings represent sexuality? Additionally, how can an individual perhaps identify these motifs that keep coming up?

The following is a list of symbols and their meaning in Marriage a la Mode by William Hogarth (1743) that is a series of six paintings that show the story of marriage in Hogarth’s eyes.

- Man has pockets turned out symbolizing he has lost money and was recently in a fight by the state of his clothes.

- Lap dog shows loyalty but sniffs at woman’s hat in the husband’s pocket showing sexual exploits.

- Black dot on husband’s neck believed to be symbol of syphilis.

- Mantel full of ugly Chinese porcelain statues symbolizing that the couple has no class.

- Butler had to go pay bills, you can tell this by the distasteful look on his face and that his pockets are stuffed with bills and papers.

- Card game just finished up, women has directions to game under foot, shows her easily cheating nature.

- Paintings of saints line a wall of the background room, isolated from the living, shows the couple’s complete disregard to faith and religion.

- The dangers of sexual excess are underscored in the Hograth by placing Cupid among ruins, foreshadowing the inevitable ruin of the marriage.

- Eventually the series (other five paintings) shows that the woman has an affair, the men duel and die, the woman hangs herself and the father takes her ring off her finger symbolizing the one thing he could salvage from the marriage.

Writing About Art

- Formal Analysis

Formal analysis is a specific type of visual description. Unlike ekphrasis, it is not meant to evoke the work in the reader’s mind. Instead it is an explanation of visual structure, of the ways in which certain visual elements have been arranged and function within a composition. Strictly speaking, subject is not considered and neither is historical or cultural context. The purest formal analysis is limited to what the viewer sees. Because it explains how the eye is led through a work, this kind of description provides a solid foundation for other types of analysis. It is always a useful exercise, even when it is not intended as an end in itself.

The British art critic Roger Fry (1866-1934) played an important role in developing the language of formal analysis we use in English today. Inspired by modern art, Fry set out to escape the interpretative writing of Victorians like Ruskin. He wanted to describe what the viewer saw, independent of the subject of the work or its emotional impact. Relying in part upon late 19th- and early 20th-century studies of visual perception, Fry hoped to bring scientific rigor to the analysis of art. If all viewers responded to visual stimuli in the same way, he reasoned, then the essential features of a viewer’s response to a work could be analyzed in absolute – rather than subjective or interpretative – terms. This approach reflected Fry’s study of the natural sciences as an undergraduate. Even more important were his studies as a painter, which made him especially aware of the importance of how things had been made. 17

The idea of analyzing a single work of art, especially a painting, in terms of specific visual components was not new. One of the most influential systems was created by the 17th-century French Academician Roger de Piles (1635-1709). His book, The Principles of Painting , became very popular throughout Europe and appeared in many languages. An 18th-century English edition translates de Piles’s terms of analysis as: composition (made up of invention and disposition or design), drawing, color, and expression. These ideas and, even more, these words, gained additional fame in the English-speaking world when the painter and art critic Jonathan Richardson (1665-1745) included a version of de Piles’s system in a popular guide to Italy. Intended for travelers, Richardson’s book was read by everyone who was interested in art. In this way, de Piles’s terms entered into the mainstream of discussions about art in English. 18

Like de Piles’s system, Roger Fry’s method of analysis breaks a work of art into component parts, but they are different ones. The key elements are (in Joshua Taylor’s explanation):

Color , both as establishing a general key and as setting up a relationship of parts; line , both as creating a sense of structure and as embodying movement and character; light and dark , which created expressive forms and patterns at the same time as it suggested the character of volumes through light and shade; the sense of volume itself and what might be called mass as contrasted with space; and the concept of plane , which was necessary in discussing the organization of space, both in depth and in a two-dimensional pattern. Towering over all these individual elements was the composition , how part related to part and to whole: composition not as an arbitrary scheme of organization but as a dominant contributor to the expressive content of the painting. 19

Fry first outlined his analytical approach in 1909, published in an article which was reprinted in 1920 in his book Vision and Design . 20

Some of the most famous examples of Fry's own analyses appear in Cézanne. A Study of His Development . 21 Published in 1927, the book was intended to persuade readers that Cézanne was one of the great masters of Western art long before that was a generally accepted point of view. Fry made his argument through careful study of individual paintings, many in private collections and almost all of them unfamiliar to his readers. Although the book included reproductions of the works, they were small black-and-white illustrations, murky in tone and detail, which conveyed only the most approximate idea of the pictures. Furthermore, Fry warned his readers, “it must always be kept in mind that such [written] analysis halts before the ultimate concrete reality of the work of art, and perhaps in proportion to the greatness of the work it must leave untouched a greater part of the objective.” 22 In other words, the greater the work, the less it can be explained in writing. Nonetheless, he set out to make his case with words.

One of the key paintings in Fry’s book is Cézanne’s Still-life with Compotier (Private collection, Paris), painted about 1880. The lengthy analysis of the picture begins with a description of the application of paint. This was, Fry felt, the necessary place of beginning because all that we see and feel ultimately comes from paint applied to a surface. He wrote: “Instead of those brave swashing strokes of the brush or palette knife [that Cézanne had used earlier], we find him here proceeding by the accumulation of small touches of a full brush.” 23 This single sentence vividly outlines two ways Cézanne applied paint to his canvas (“brave, swashing strokes” versus “small touches”) and the specific tools he used (brush and palette knife). As is often the case in Fry’s writing, the words he chose go beyond what the viewer sees to suggest the process of painting, an explanation of the surface in terms of the movement of the painter’s hand.

After a digression about how other artists handled paint, Fry returned to Still-life with Compotier . He rephrased what he had said before, integrating it with a fuller description of Cézanne’s technique:

[Cézanne] has abandoned altogether the sweep of a broad brush, and builds up his masses by a succession of hatched strokes with a small brush. These strokes are strictly parallel, almost entirely rectilinear, and slant from right to left as they descend. And this direction of the brush strokes is carried through without regard to the contours of the objects. 24

From these three sentences, the reader gathers enough information to visualize the surface of the work. The size of the strokes, their shape, the direction they take on the canvas, and how they relate to the forms they create are all explained. Already the painting seems very specific. On the other hand, the reader has not been given the most basic facts about what the picture represents. For Fry, that information only came after everything else, if it was mentioned at all.

Then Fry turned to “the organization of the forms and the ordering of the volumes.” Three of the objects in the still-life are mentioned, but only as aspects of the composition.

Each form seems to have a surprising amplitude, to permit of our apprehending it with an ease which surprises us, and yet they admit a free circulation in the surrounding space. It is above all the main directions given by the rectilinear lines of the napkin and the knife that make us feel so vividly this horizontal extension [of space]. And this horizontal [visually] supports the spherical volumes, which enforce, far more than real apples could, the sense of their density and mass.

He continued in a new paragraph:

One notes how few the forms are. How the sphere is repeated again and again in varied quantities. To this is added the rounded oblong shapes which are repeated in two very distinct quantities in the compotier and the glass. If we add the continually repeated right lines [of the brush strokes] and the frequently repeated but identical forms of the leaves on the wallpaper, we have exhausted this short catalogue. The variation of quantities of these forms is arranged to give points of clear predominance to the compotier itself to the left, and the larger apples to the right centre. One divines, in fact, that the forms are held together by some strict harmonic principle almost like that of the canon in Greek architecture, and that it is this that gives its extraordinary repose and equilibrium to the whole design. 25

Finally the objects in the still-life have come into view: a compotier (or fruit dish), a glass, apples, and a knife, arranged on a cloth and set before patterned wallpaper.

In Fry’s view of Cézanne, contour, or the edges of forms, are especially important. The Impressionists, Cézanne's peers and exact contemporaries, were preoccupied “by the continuity of the visual welt.” For Cézanne, on the other hand, contour

became an obsession. We find the traces of this throughout this still-life. He actually draws the contour with his brush, generally in a bluish grey. Naturally the curvature of this line is sharply contrasted with his parallel hatchings, and arrests the eye too much. He then returns upon it incessantly by repeated hatchings which gradually heap up round the contour to a great thickness. The contour is continually being lost and then recovered . . . [which] naturally lends a certain heaviness, almost clumsiness, to the effect; but it ends by giving to the forms that impressive solidity and weight which we have noticed. 26

Fry ended his analysis with the shapes, conceived in three dimensions (“volumes”) and in two dimensions (“contours”):

At first sight the volumes and contours declare themselves boldly to the eye. They are of a surprising simplicity, and are clearly apprehended. But the more one looks the more they elude any precise definition. The apparent continuity of the contour is illusory, for it changes in quality throughout each particle of its length. There is no uniformity in the tracing of the smallest curve. . . . We thus get at once the notion of extreme simplicity in the general result and of infinite variety in every part. It is this infinitely changing quality of the very stuff of painting which communicates so vivid a sense of life. In spite of the austerity of the forms, all is vibration and movement. 27

Fry wrote with a missionary fervor, intent upon persuading readers of his point of view. In this respect, his writings resemble Ruskin’s, although Fry replaced Ruskin’s rich and complicated language with clear, spare words about paint and composition. A text by Fry like the one above provides the reader with tangible details about the way a specific picture looks, whereas Ruskin’s text supplies an interpretation of its subject. Of course, different approaches may be inspired by the works themselves. Ignoring the subject is much easier if the picture represents a grouping of ordinary objects than if it shows a dramatic scene of storm and death at sea. The fact that Fry believed in Cézanne’s art so deeply says something about what he believed was important in art. It also says something about the taste of the modern period, just as Ruskin’s values and style of writing reveal things about the Victorian period. Nonetheless, anyone can learn a great deal from reading either of them.

Ellen Johnson, an art historian and art critic who wrote extensively about modern art, often used formal analysis. One example is a long description of Richard Diebenkorn's Woman by a Large Window (Allen Art Museum, Oberlin), which covers the arrangement of shapes into a composition, the application of paint, the colors, and finally the mood of the work. Although organized in a different order from Fry's analysis of Cézanne's still-life, her discussion defines the painting in similar terms.

[Diebenkorn's] particular way of forming the picture . . . is captivating, . . . organizing the picture plane into large, relatively open areas interrupted by a greater concentration of activity, a spilling of shapes and colors asymmetrically placed on one side of the picture. In Woman by a Large Window the asymmetry of the painting is further enhanced by having the figure not only placed at the left of the picture but, more daringly, facing directly out of the picture. This leftward direction and placement is brought into a precarious and exciting but beautifully controlled balance by the mirror on the right which . . . creates a fascinating ambiguity and enrichment of the picture space. . . . The interior of the room and the woman in it are painted in subdued, desert-sand colors, roughly and vigorously applied with much of the drawing achieved by leaving exposed an earlier layer of paint. The edges of the window, table and chair, and the contours of the figure, not to mention the purple eye, were drawn in this way. In other areas, the top layer, roughly applied as though with a scrub brush, is sufficiently thin to permit the under-color to show through and vary the surface hue. . . . [T]he landscape is more positive in hue and value contrasts and the paint more thick and rich. The bright apple-green of the fields and the very dark green of the trees are enlivened by smaller areas of orange, yellow and purple; the sky is intensely blue. The glowing landscape takes on added sparkle by contrast with the muted interior . . . . Pictorially, however, [the woman] is anchored to the landscape by the dark of her hair forming one value and shape with the trees behind her. This union of in and out, of near and far, repeated in the mirror image, emphasizes the plane of the picture, the two-dimensional character of which is further asserted by the planar organization into four horizontal divisions: floor, ledge, landscape and sky. Thus, while the distance of the landscape is firmly stated, it is just as firmly denied . . . . While the mood of the picture is conveyed most obviously through the position and attitude of the figure, still the entire painting functions in evoking this response . . . Lonely but composed, withdrawn from but related to her environment, the woman reminds one of the self-contained, quiet and melancholy figures on Greek funerary reliefs. Like them, relaxed and still, she seems to have sat for centuries. 28

Johnson’s description touches on all aspects of what the viewer sees before ending with a final paragraph about mood. Firmly situated in our understanding of specific physical and visual aspects of Diebenkorn’s painting, her analogy to the seated women on Greek funerary reliefs enhances our ability to envision the position and spirit of this woman. It makes the picture seem vivid by referring to something entirely other. The image also is unexpected, so the description ends with an idea that catches our attention because it is new, while simultaneously summarizing an important part of her analysis. An allusion must work perfectly to be useful, however. Otherwise it becomes a distraction, a red herring that leads the reader away from the subject at hand.

The formal analysis of works other than paintings needs different words. In Learning to Look , Joshua Taylor identified three key elements that determine much of our response to works of sculpture. The artist “creates not only an object of a certain size and weight but also a space that we experience in a specific way.” A comparison between an Egyptian seated figure (Louvre, Paris) and Giovanni da Bologna’s Mercury (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) reveals two very different treatments of form and space:

The Egyptian sculptor, cutting into a block of stone, has shaped and organized the parts of his work so that they produce a particular sense of order, a unique and expressive total form. The individual parts have been conceived of as planes which define the figure by creating a movement from one part to another, a movement that depends on our responding to each new change in direction. . . . In this process our sense of the third-dimensional aspect of the work is enforced and we become conscious of the work as a whole. The movement within the figure is very slight, and our impression is one of solidity, compactness, and immobility.

In Mercury , on the other hand, “the movement is active and rapid.”

The sculptor’s medium has encouraged him to create a free movement around the figure and out into the space in which the figure is seen. This space becomes an active part of the composition. We are conscious not only of the actual space displaced by the figure, as in the former piece, but also of the space seeming to emanate from the figure of Mercury. The importance of this expanding space for the statue may be illustrated if we imagine this figure placed in a narrow niche. Although it might fit physically, its rhythms would seem truncated, and it would suffer considerably as a work of art. The Egyptian sculpture might not demand so particular a space setting, but it would clearly suffer in assuming Mercury’s place as the center piece of a splashing fountain. 29

Rudolf Arnheim (1904-2007) also used formal analysis, but as it relates to the process of perception and psychology, specifically Gestalt psychology, which he studied in Berlin during the 1920s. Less concerned with aesthetic qualities than the authors quoted above, he was more rigorous in his study of shapes, volumes, and composition. In his best-known book, Art and Visual Perception. A Psychology of the Creative Eye , first published in 1954, Arnheim analyzed, in order: balance, shape, form, growth, space, light, color, movement, tension, and expression. 30 Many of the examples given in the text are works of art, but he made it clear that the basic principles relate to any kind of visual experience. In other books, notably Visual Thinking and the Power of the Center: A Study of Composition in the Visual Arts , Arnheim developed the idea that visual perception is itself a kind of thought. 31 Seeing and comprehending what has been seen are two different aspects of the same mental process. This was not a new idea, but he explored it in relation to many specific visual examples.

Arnheim began with the assumption that any work of art is a composition before it is anything else:

When the eyes meet a particular picture for the first time, they are faced with the challenge of the new situation: they have to orient themselves, they have to find a structure that will lead the mind to the picture’s meaning. If the picture is representational, the first task is to understand the subject matter. But the subject matter is dependent on the form, the arrangement of the shapes and colors, which appears in its pure state in “abstract,” non-mimetic works. 32

To explain how different uses of a central axis alter compositional structure, for example, Arnheim compared El Greco’s Expulsion from the Temple (Frick Collection, New York) to Fra Angelico’s Annunciation (San Marco, Florence). About the first, Arnheim wrote:

The central object reposes in stillness even when within itself it expresses strong action. The Christ . . . is a typical figura serpentinata [spiral figure]. He chastises the merchant with a decisive swing of the right arm, which forces the entire body into a twist. The figure as a whole, however, is firmly anchored in the center of the painting, which raises the event beyond the level of a passing episode. Although entangled with the temple crowd, Christ is a stable axis around which the noisy happening churns. 33

Although his discussion identifies the forms in terms of subject, Arnheim’s only concern is the way the composition works around its center. The same is true in his discussion of Fra Angelico’s fresco:

As soon as we split the compositional space down the middle, its structure changes. It now consists of two halves, each organized around its own center. . . . Appropriate compositional features must bridge the boundary. Fra Angelico’s Annunciation at San Marco, for example, is subdivided by a prominent frontal column, which distinguishes the celestial realm of the angel from the earthly realm of the Virgin. But the division is countered by the continuity of the space behind the column. The space is momentarily covered but not interrupted by the vertical in the foreground. The lively interaction between the messenger and recipient also helps bridge the separation. 34

All formal analysis identifies specific visual elements and discusses how they work together. If the goal of a writer is to explain how parts combine to create a whole, and what effect that whole has on the viewer, then this type of analysis is essential. It also can be used to define visual characteristics shared by a number of objects. When the similarities seem strong enough to set a group of objects apart from others, they can be said to define a "style." Stylistic analysis can be applied to everything from works made during a single period by a single individual to a survey of objects made over centuries. All art historians use it.

- Introduction

- Personal Style

- Period Style

- "Realistic"

- The Biography

- Iconographic Analysis

- Historical Analysis

- Bibliography

- Appendix I: Writing the Paper

- Appendix II: Citation Forms

- Visual Description

- Stylistic Analysis

- Doing the Research

- The First Draft

- The Final Paper

- About the Author

- ISBN: 978-1441486240 Paperback $10 Kindle Edition $1.99

© Marjorie Munsterberg 2008-2009

Alberti’s Window

An art history blog.

- ancient Near East

- formal analysis

- introductory/survey

Wednesday, August 24th, 2011

Ancient Art: Formal Analysis Example

Note: The following post is intended to be a resource for my ancient art students. If you know of any good examples of basic formal analysis that are available online, please leave links in the comments section below! I would like to build up a list of resources for my students.

Formal elements are things that are part of the form (or physical properties) of a work of art: medium, line, color, scale, size, composition, etc. Formal analysis involves an exploration of how these formal elements affect you, as a viewer.

Formal analysis involves describing a work of art, but formal analysis goes beyond mere description. Instead, description is used as an agent to support the argument-at-hand. Although your essay will likely introduce a work of art with some general descriptions, the rest of your descriptions should be very pinpointed and with purpose. Make sure that such detailed descriptions are used to back up specific points of your argument. For this formal analysis assignment, your argument will revolve around some type of reaction to the work of art.

Your formal analysis should include some type of thesis statement that revolves around your reaction. To help you think about your own assignment and personal reaction, I have written a short sample of formal analysis below (and have underlined the thesis statement). Please also note that I am not basing my reaction on content (i.e. the subject matter, narrative, or symbolism), nor on historical context. Instead, I am focusing strictly on formal (visual or physical) elements:

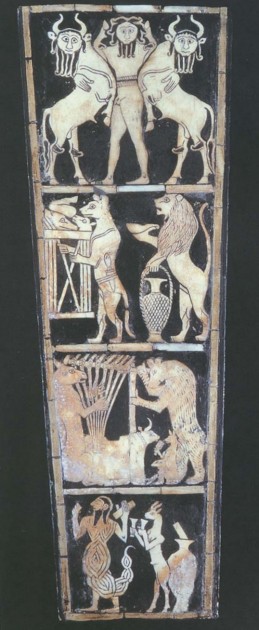

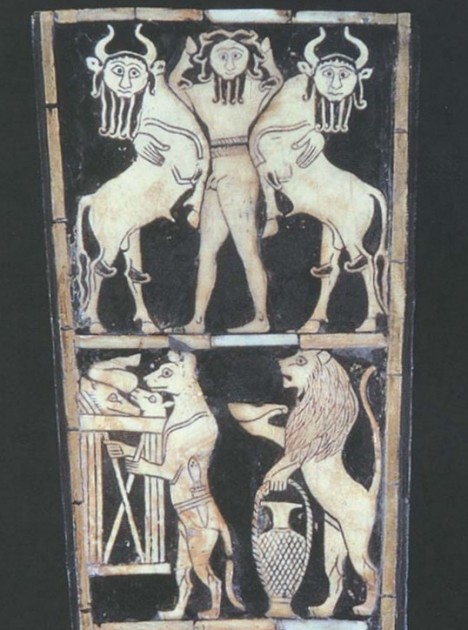

Great Lyre sound box, c. 2600-2500 BCE

The front panel of the Great Lyre sound box (shown above) is an example of Sumerian art from the Ancient Near East.The panel is divided into four different registers. These registers contain four scenes with figures (mostly animals) involved in various activities. Despite the rather rigid compartmentalization of the four sound box scenes, the overall effect of the front panel of the Great Lyre sound box is one of energy and dynamism. Such energy can be seen in the color of the figures and in curvy compositional lines.

The sound box is comprised of two different colors, a dark black and a light tan. These colors are caused by the medium of the panel. Dark black is the color of bitumen, which is used for the background of the panel and lines. Light tan is the color of the inlaid shell that is used for the bodies of the figures and objects. The stark contrast of light tan against a dark background adds a sense of dynamism to the figures. The figures seem to glow and hum with life. Furthermore, these lightly-colored figures are pushed closer toward the viewer, away from the black background, which gives the figures a sense of presence and energy.

Detail of top registers of Great Lyre sound box, c. 2600-2500 BCE

The composition of the figures also lends itself to this idea of energy. The figures fill the whole space of their respective registers and scenes, giving them a strong, energetic presence. In fact, some figures strain and twist so that their bodies can fill and fit within the register space. Such dynamic twisting is especially seen in the two bulls in the upper-most register (see image above). These bulls are symmetrically placed on either side of a central human figure, creating a “Master of the Animals” motif. The bodies of the bulls twist inward toward the human figure, and but their necks and heads twist outward and slightly downward. The theme of curves and energy is underscored in the beards and hair of these three figures: each lock of hair ends with a bouncy curl.

Energy can be seen in the curvaceous lines of other figures as well. In the second register from the top, the backs and tails of the hyena and lion are comprised of swooping lines. In fact, the lines of the lion’s back are reinforced and highlighted by swooping, short lines that suggest the lion’s bushy mane. While the lion’s mane swoops toward the center of the scene, the lion’s lower back curves in the other direction. These opposing compositional lines give the panel an added sense of energy and movement.

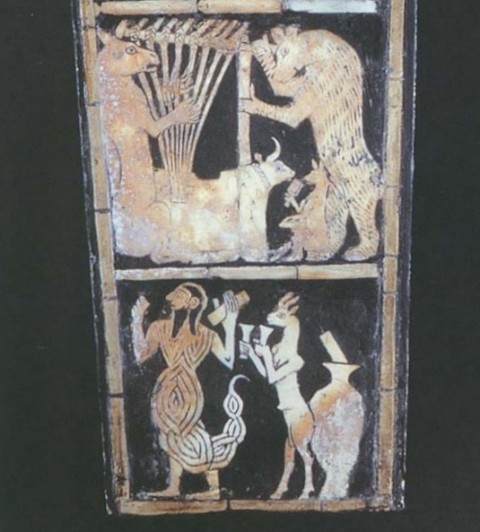

Detail of bottom registers of Great Lyre sound box, c. 2600-2500 BCE

In the second register from the bottom, the back of the bear curves upward and downward in a lyrical, dynamic swoop (see image above). In fact, the whole body of the bear is placed at a more dynamic angle, since the bear is leaning toward the lyre placed on the left side of the scene. Some of the strings of the lyre curve upward toward the right, opposite the angle of the bear’s body, to add more opposing movement and dynamism to the overall composition.

The lowest register of the front panel contains some of the most dynamic curves and lines. The most obvious curve is found in the tail of the scorpion man on the left side of the scene. This tail curls and swoops upward, only to end with a stinger that loops downward. The shape and detail lines of the scorpion tail are also energetic. The tail is comprised of several oval shapes of decreasing sizes. These shapes are combined together to creating a visually dynamic, bouncy outline for the tail. Furthermore, the tail is full of energy because of the multiple lines that appear within each oval shape. These lines look a little like a maze or labyrinth; they visually reinforce the idea of movement through their repetition and interlocking layout.

The front panel of the Great Lyre sound box embodies energy in many ways. This energy can be seen not only because of the colors of the panel, but also through several compositional devices and lines. Such visual interest in energy is fitting for this piece, given that this sound box originally hummed with musical vibrations and the energy created by sound.

For further information about formal analysis, you may want to look at the chapter, “Formal Analysis” by Anne d’Alleva. Preview is available online here .

3 Responses to Ancient Art: Formal Analysis Example —

Wonderful! Thank you.

Hi! I was referred to this blog by a mutual friend, Nik English. I received my bachelor's degree in Art History last year and am looking for opportunities to work or continue to study in this field so if you have any advise he thought you might be able to help.

As far as Formal Analysis examples go I liked this site from the University of Arkansas because these examples also show you the format for the paper as well as the writing style. Hope that helps:

http://ualr.edu/art/index.php/home/undergraduate-information/bachelor-of-arts-in-art-ba-in-art/bachelor-of-arts-in-art-art-history-track/formal-analysis-example-1/

Thanks for the comments!

Samantha, thanks for including the link to the University of Arkansas site. I wasn't familiar with that resource beforehand! It's nice to have some student examples posted online.

Also, I'd be happy to talk with you about job or schooling opportunities. It was kind of Nik to mention me. If you want to write me an email with more information about your background and interests, I can try and give you some recommendations. My contact info is at the top left hand side of my blog homepage.

Entries RSS Comments RSS

Email Subscription

An email notification will be sent whenever a new post appears on this site.

- 18th century (38)

- 19th century (81)

- 20th century (85)

- accidental damage (3)

- act of blogging (5)

- American (1)

- ancient Near East (10)

- architecture (19)

- art crime (21)

- art history humor (6)

- Art Nouveau (1)

- art theory and philosophy (29)

- artistic mediums (2)

- Arts and Crafts (2)

- bad art (1)

- Berenson (1)

- Brazilian – Imperial and Republican (3)

- Brazilian Baroque (9)

- Byzantine (9)

- carnival (3)

- celebrities (8)

- censorship (3)

- Colonial Brazil (6)

- colonialism (8)

- conferences (1)

- contemporary art (47)

- Early Christian (7)

- Egyptian (16)

- Etruscan (6)

- female artists (25)

- female collectors (5)

- films and television (7)

- formal analysis (2)

- German Baroque (2)

- giveaway (12)

- Gombrich (3)

- Greek and Roman (46)

- guest post (4)

- historiography (4)

- Impressionism (6)

- Indigenous art (2)

- intentional damage (7)

- introductory/survey (7)

- Mannerism (7)

- Middle Ages (19)

- Minoan/Mycenaean (10)

- museums and exhibitions (38)

- Nabatean (Hellenistic) (3)

- Neoclassicism (3)

- news and links (81)

- non-Western (16)

- Northern Baroque (28)

- Northern Renaissance (40)

- photography (1)

- pop culture (11)

- portraiture (9)

- Post Impressionism (1)

- Pre Raphaelites (5)

- prehistoric art (11)

- Proto-Renaissance (2)

- Romanesque (4)

- Romanticism (3)

- Seattle Art Museum (9)

- Southern Baroque (47)

- Southern Renaissance (64)

- Spanish America (1)

- student research (1)

- teaching (5)

- textbook errors (7)

- Uncategorized (7)

- Vasari (13)

- William Morris (4)

- Winckelmann (7)

- October 2024 (1)

- April 2024 (1)

- September 2023 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- April 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (1)

- August 2021 (2)

- May 2021 (1)

- February 2021 (3)

- January 2021 (1)

- November 2020 (1)

- September 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- October 2019 (2)

- September 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- July 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (1)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (2)

- October 2017 (1)

- September 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (2)

- May 2017 (3)

- April 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (1)

- December 2016 (1)

- November 2016 (2)

- September 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (1)

- April 2016 (2)

- March 2016 (1)

- February 2016 (3)

- January 2016 (2)

- November 2015 (2)

- October 2015 (1)

- September 2015 (1)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (2)

- June 2015 (3)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (2)

- February 2015 (5)

- January 2015 (2)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- October 2014 (4)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (3)

- July 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (2)

- April 2014 (2)

- March 2014 (3)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (2)

- September 2013 (6)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (2)

- June 2013 (4)

- May 2013 (3)

- April 2013 (4)

- March 2013 (2)

- February 2013 (4)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (4)

- November 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (4)

- August 2012 (3)

- July 2012 (4)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (2)

- April 2012 (3)

- March 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (3)

- December 2011 (6)

- November 2011 (3)

- October 2011 (2)

- September 2011 (6)

- August 2011 (8)

- July 2011 (4)

- June 2011 (6)

- May 2011 (5)

- April 2011 (6)

- March 2011 (6)

- February 2011 (7)

- January 2011 (8)

- December 2010 (7)

- November 2010 (8)

- October 2010 (9)

- September 2010 (10)

- August 2010 (11)

- July 2010 (7)

- June 2010 (11)

- May 2010 (9)

- April 2010 (7)

- March 2010 (10)

- February 2010 (9)

- January 2010 (11)

- December 2009 (8)

- November 2009 (8)

- October 2009 (13)

- September 2009 (9)

- August 2009 (12)

- July 2009 (12)

- June 2009 (11)

- May 2009 (9)

- April 2009 (9)

- March 2009 (11)

- February 2009 (6)

- January 2009 (8)

- December 2008 (4)

- November 2008 (3)

- October 2008 (8)

- September 2008 (4)

- August 2008 (5)

- July 2008 (3)

- March 2008 (2)

- August 2007 (2)

- July 2007 (1)

@albertis_window

- Art History Flashbook

- Art History Newsletter

- Art History Ramblings

- Art History Salon

- Art History Today

- Art Inconnu

- Art Theft Central

- ARTHistories

- Baroque Potion

- Caravaggista

- Cave to Canvas

- CultureGrrl

- Every Painter Paints Himself

- Experiments in Art History

- Giorgione et al…

- L'Historien Errant

- Martin Kemp

- Medieval Illumination

- Sedef's Corner

- SmART History Timeline

- The Canon 2010

- Three Pipe Problem

- Van Gogh's Chair

- When Art History Goes Bad

Art History

What this handout is about.

This handout discusses a few common assignments found in art history courses. To help you better understand those assignments, this handout highlights key strategies for approaching and analyzing visual materials.

Writing in art history

Evaluating and writing about visual material uses many of the same analytical skills that you have learned from other fields, such as history or literature. In art history, however, you will be asked to gather your evidence from close observations of objects or images. Beyond painting, photography, and sculpture, you may be asked to write about posters, illustrations, coins, and other materials.

Even though art historians study a wide range of materials, there are a few prevalent assignments that show up throughout the field. Some of these assignments (and the writing strategies used to tackle them) are also used in other disciplines. In fact, you may use some of the approaches below to write about visual sources in classics, anthropology, and religious studies, to name a few examples.

This handout describes three basic assignment types and explains how you might approach writing for your art history class.Your assignment prompt can often be an important step in understanding your course’s approach to visual materials and meeting its specific expectations. Start by reading the prompt carefully, and see our handout on understanding assignments for some tips and tricks.

Three types of assignments are discussed below:

- Visual analysis essays

- Comparison essays

- Research papers

1. Visual analysis essays

Visual analysis essays often consist of two components. First, they include a thorough description of the selected object or image based on your observations. This description will serve as your “evidence” moving forward. Second, they include an interpretation or argument that is built on and defended by this visual evidence.

Formal analysis is one of the primary ways to develop your observations. Performing a formal analysis requires describing the “formal” qualities of the object or image that you are describing (“formal” here means “related to the form of the image,” not “fancy” or “please, wear a tuxedo”). Formal elements include everything from the overall composition to the use of line, color, and shape. This process often involves careful observations and critical questions about what you see.

Pre-writing: observations and note-taking

To assist you in this process, the chart below categorizes some of the most common formal elements. It also provides a few questions to get you thinking.

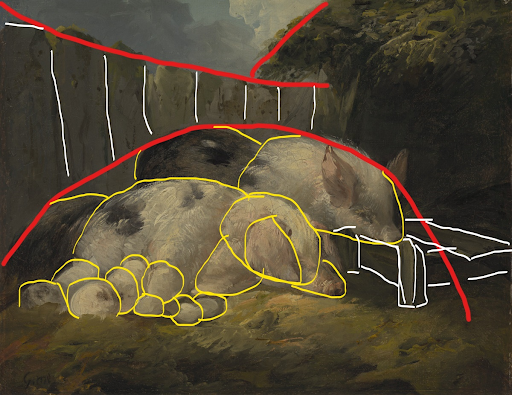

Let’s try this out with an example. You’ve been asked to write a formal analysis of the painting, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty , ca. 1800 (created in Britain and now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond).

What do you notice when you see this image? First, you might observe that this is a painting. Next, you might ask yourself some of the following questions: what kind of paint was used, and what was it painted on? How has the artist applied the paint? What does the scene depict, and what kinds of figures (an art-historical term that generally refers to humans) or animals are present? What makes these animals similar or different? How are they arranged? What colors are used in this painting? Are there any colors that pop out or contrast with the others? What might the artist have been trying to accomplish by adding certain details?

What other questions come to mind while examining this work? What kinds of topics come up in class when you discuss paintings like this one? Consider using your class experiences as a model for your own description! This process can be lengthy, so expect to spend some time observing the artwork and brainstorming.

Here is an example of some of the notes one might take while viewing Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty :

Composition

- The animals, four pigs total, form a gently sloping mound in the center of the painting.

- The upward mound of animals contrasts with the downward curve of the wooden fence.

- The gentle light, coming from the upper-left corner, emphasizes the animals in the center. The rest of the scene is more dimly lit.

- The composition is asymmetrical but balanced. The fence is balanced by the bush on the right side of the painting, and the sow with piglets is balanced by the pig whose head rests in the trough.

- Throughout the composition, the colors are generally muted and rather limited. Yellows, greens, and pinks dominate the foreground, with dull browns and blues in the background.

- Cool colors appear in the background, and warm colors appear in the foreground, which makes the foreground more prominent.

- Large areas of white with occasional touches of soft pink focus attention on the pigs.

- The paint is applied very loosely, meaning the brushstrokes don’t describe objects with exact details but instead suggest them with broad gestures.

- The ground has few details and appears almost abstract.

- The piglets emerge from a series of broad, almost indistinct, circular strokes.

- The painting contrasts angular lines and rectangles (some vertical, some diagonal) with the circular forms of the pig.

- The negative space created from the intersection of the fence and the bush forms a wide, inverted triangle that points downward. The point directs viewers’ attention back to the pigs.

Because these observations can be difficult to notice by simply looking at a painting, art history instructors sometimes encourage students to sketch the work that they’re describing. The image below shows how a sketch can reveal important details about the composition and shapes.

Writing: developing an interpretation

Once you have your descriptive information ready, you can begin to think critically about what the information in your notes might imply. What are the effects of the formal elements? How do these elements influence your interpretation of the object?

Your interpretation does not need to be earth-shatteringly innovative, but it should put forward an argument with which someone else could reasonably disagree. In other words, you should work on developing a strong analytical thesis about the meaning, significance, or effect of the visual material that you’ve described. For more help in crafting a strong argument, see our Thesis Statements handout .

For example, based on the notes above, you might draft the following thesis statement:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the close proximity of the pigs to each other–evident in the way Morland has overlapped the pigs’ bodies and grouped them together into a gently sloping mound–and the soft atmosphere that surrounds them hints at the tranquility of their humble farm lives.

Or, you could make an argument about one specific formal element:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the sharp contrast between rectilinear, often vertical, shapes and circular masses focuses viewers’ attention on the pigs, who seem undisturbed by their enclosure.

Support your claims

Your thesis statement should be defended by directly referencing the formal elements of the artwork. Try writing with enough specificity that someone who has not seen the work could imagine what it looks like. If you are struggling to find a certain term, try using this online art dictionary: Tate’s Glossary of Art Terms .

Your body paragraphs should explain how the elements work together to create an overall effect. Avoid listing the elements. Instead, explain how they support your analysis.

As an example, the following body paragraph illustrates this process using Morland’s painting:

Morland achieves tranquility not only by grouping animals closely but also by using light and shadow carefully. Light streams into the foreground through an overcast sky, in effect dappling the pigs and the greenery that encircles them while cloaking much of the surrounding scene. Diffuse and soft, the light creates gentle gradations of tone across pigs’ bodies rather than sharp contrasts of highlights and shadows. By modulating the light in such subtle ways, Morland evokes a quiet, even contemplative mood that matches the restful faces of the napping pigs.

This example paragraph follows the 5-step process outlined in our handout on paragraphs . The paragraph begins by stating the main idea, in this case that the artist creates a tranquil scene through the use of light and shadow. The following two sentences provide evidence for that idea. Because art historians value sophisticated descriptions, these sentences include evocative verbs (e.g., “streams,” “dappling,” “encircles”) and adjectives (e.g., “overcast,” “diffuse,” “sharp”) to create a mental picture of the artwork in readers’ minds. The last sentence ties these observations together to make a larger point about the relationship between formal elements and subject matter.

There are usually different arguments that you could make by looking at the same image. You might even find a way to combine these statements!

Remember, however you interpret the visual material (for example, that the shapes draw viewers’ attention to the pigs), the interpretation needs to be logically supported by an observation (the contrast between rectangular and circular shapes). Once you have an argument, consider the significance of these statements. Why does it matter if this painting hints at the tranquility of farm life? Why might the artist have tried to achieve this effect? Briefly discussing why these arguments matter in your thesis can help readers understand the overall significance of your claims. This step may even lead you to delve deeper into recurring themes or topics from class.

Tread lightly

Avoid generalizing about art as a whole, and be cautious about making claims that sound like universal truths. If you find yourself about to say something like “across cultures, blue symbolizes despair,” pause to consider the statement. Would all people, everywhere, from the beginning of human history to the present agree? How do you know? If you find yourself stating that “art has meaning,” consider how you could explain what you see as the specific meaning of the artwork.

Double-check your prompt. Do you need secondary sources to write your paper? Most visual analysis essays in art history will not require secondary sources to write the paper. Rely instead on your close observation of the image or object to inform your analysis and use your knowledge from class to support your argument. Are you being asked to use the same methods to analyze objects as you would for paintings? Be sure to follow the approaches discussed in class.

Some classes may use “description,” “formal analysis” and “visual analysis” as synonyms, but others will not. Typically, a visual analysis essay may ask you to consider how form relates to the social, economic, or political context in which these visual materials were made or exhibited, whereas a formal analysis essay may ask you to make an argument solely about form itself. If your prompt does ask you to consider contextual aspects, and you don’t feel like you can address them based on knowledge from the course, consider reading the section on research papers for further guidance.

2. Comparison essays

Comparison essays often require you to follow the same general process outlined in the preceding sections. The primary difference, of course, is that they ask you to deal with more than one visual source. These assignments usually focus on how the formal elements of two artworks compare and contrast with each other. Resist the urge to turn the essay into a list of similarities and differences.

Comparison essays differ in another important way. Because they typically ask you to connect the visual materials in some way or to explain the significance of the comparison itself, they may require that you comment on the context in which the art was created or displayed.

For example, you might have been asked to write a comparative analysis of the painting discussed in the previous section, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty (ca. 1800), and an unknown Vicús artist’s Bottle in the Form of a Pig (ca. 200 BCE–600 CE). Both works are illustrated below.

You can begin this kind of essay with the same process of observations and note-taking outlined above for formal analysis essays. Consider using the same questions and categories to get yourself started.

Here are some questions you might ask:

- What techniques were used to create these objects?

- How does the use of color in these two works compare? Is it similar or different?

- What can you say about the composition of the sculpture? How does the artist treat certain formal elements, for example geometry? How do these elements compare to and contrast with those found in the painting?

- How do these works represent their subjects? Are they naturalistic or abstract? How do these artists create these effects? Why do these similarities and differences matter?

As our handout on comparing and contrasting suggests, you can organize these thoughts into a Venn diagram or a chart to help keep the answers to these questions distinct.

For example, some notes on these two artworks have been organized into a chart: