Exploring Argument Writing With Visual Tools

Teachers can have students use graphic organizers and timelines to clarify their thinking during the writing process.

Your content has been saved!

As a teacher who loves to write and engage students with writing, I’ve experienced many challenges in attempting to bring composition into the classroom. While some students readily fill up blank pages with words inspired by their lives and stories they love, others are seemingly always in search of the best words.

More challenging still are those moments when I’ve led students through the steps necessary for expository and research-based argument writing. I’ve found that my students who are comfortable with the narrative mode are now thrust into compositing in a way that is unfamiliar ground.

This article explores some ways I’ve applied graphic organizers and visual planning strategies to the work of argument writing—which is perhaps the mode I consider the most challenging in the classroom.

Sifting Content

First among the challenges for argument is the way that debate and disagreement are often portrayed in popular culture—shouting matches and interruption rounds where it seems that the loudest voice wins out. In my classroom, the approach that I attempt to foster for argument is one of thoughtful intention and wisely applied rhetorical strategies.

As with much of the secondary curriculum I have worked with from middle-grades English to advanced composition, sorting information into categories (ethos/ethics, logos/logic, and emotion/pathos) is a helpful step once a topic is shared and resources are gathered.

But sorting through multiple paragraphs and pages in search of the “just right” evidence can be challenging and is a critical reading practice all on its own. To support these steps in criticality, I suggest that students create a simple three-column chart in which they can begin to sort the emotional, logical, and ethics-driven elements of their argument. Using a visual scaffold to support exploration of a complex reading is an essential step for me—and I used a similar strategy just this past week in my junior-level English class to sort out ideas and compare the writings of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke.

By sorting ideas in this way, students can physically see how balanced their argument actually is, and they can begin thinking about what they need to ramp up for the eventual presentation of the case.

Gathering Further Ideas

Another challenge in composing arguments is not only sorting and interpreting information, but also applying it in a way that includes informative and persuasive techniques.

As students consider the ways to apply these skills, they can begin to think through additional sources that they can use to build their foundation for thinking about the issues they’re presenting and noting the sources that help them build the strongest case. This type of exploring and writing is especially important when practicing synthesizing ideas across multiple sources.

On the surface, this process sounds like reading and rereading multiple sources (and it is). However, I apply a visual scaffold to this process to help students think about how their resources are linked and support or contradict each other. I illustrate the claim, counterclaim, and rebuttal aspects of argument structure through a visual outline, but the work of fleshing out these sections of the discussion takes place best in a mind map structure.

A simple three-circle Venn diagram can help students begin placing ideas into the claim section, and they can explore how authors overlap ideas with one another through this graphic organizer format. Ideally, they reach a point where the strongest ideas are in the center “target” point of the argument structure. They can think about best placement of these strongest ideas as leading points or final rebuttals—depending on what they want to leave their audience with. This approach is also helpful for relieving some of the stress that can surround framing what might be a challenging and less comfortable form of writing.

The additional details they gather can then be sorted further into areas of the argument structure that make sense.

Establishing Timelines

Further adapting the outline style, I encourage students to think about the argument as a timeline wherein their audience is most likely to connect with information early and remember information late. Outlining is almost always a building block of what I ask students to engage with when composing. For debates and discussions in our class, writing a timeline is an effective process.

From this timeline (prompting discussion and exploration of evidence and argument), students can practice writing their own arguments and responses by modifying it and including aspects of evidence and ideas they want to share (in whatever particular order they'd like to present their research).

Crafting Closing Arguments

By approaching an argument step-by-step, as discussion and collaboration that improves through a process, I have the goal of making what might seem complicated and overwhelming much more attainable and inviting—even, dare I say, active and interesting.

I recognize that many of my students might not have had vast experiences with all of the modes of writing and composing, and I take into account that some will be more naturally inclined to some ways of writing and sharing than others. Some students eagerly take the lead in an oral debate process, while others more readily engage in the research roles and independent writing components of the work.

As with much of my work in literacy, I attempt to make an invisible process clear and visual—in this case, through graphic organizers. I am aware that teachers might find other graphic organizer options that work more effectively at particular aspects of the argument process. For example, the Venn diagram might not communicate in the ways that a teacher may want, and so a flow chart/mind map or T-chart might work as a better substitute.

I encourage teachers to modify any steps in order to better support their students and focus on the importance of critical thinking and composing for all students.

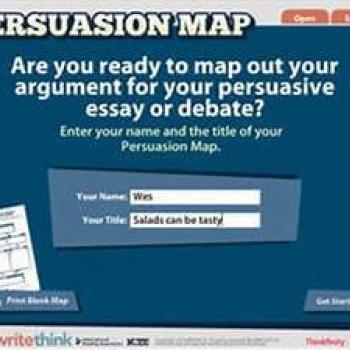

Persuasion Map

About this Interactive

Related resources.

The Persuasion Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to map out their arguments for a persuasive essay or debate. Students begin by determining their goal or thesis. They then identify three reasons to support their argument, and three facts or examples to validate each reason. The map graphic in the upper right-hand corner allows students to move around the map, instead of having to work in a linear fashion. The finished map can be saved, e-mailed, or printed.

- Student Interactives

- Strategy Guides

- Calendar Activities

- Lesson Plans

The Essay Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to organize and outline their ideas for an informational, definitional, or descriptive essay.

This Strategy Guide describes the processes involved in composing and producing audio files that are published online as podcasts.

This strategy guide explains the writing process and offers practical methods for applying it in your classroom to help students become proficient writers.

Through a classroom game and resource handouts, students learn about the techniques used in persuasive oral arguments and apply them to independent persuasive writing activities.

Students analyze rhetorical strategies in online editorials, building knowledge of strategies and awareness of local and national issues. This lesson teaches students connections between subject, writer, and audience and how rhetorical strategies are used in everyday writing.

Students examine books, selected from the American Library Association Challenged/Banned Books list, and write persuasive pieces expressing their views about what should be done with the books at their school.

Students will research a local issue, and then write letters to two different audiences, asking readers to take a related action or adopt a specific position on the issue.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

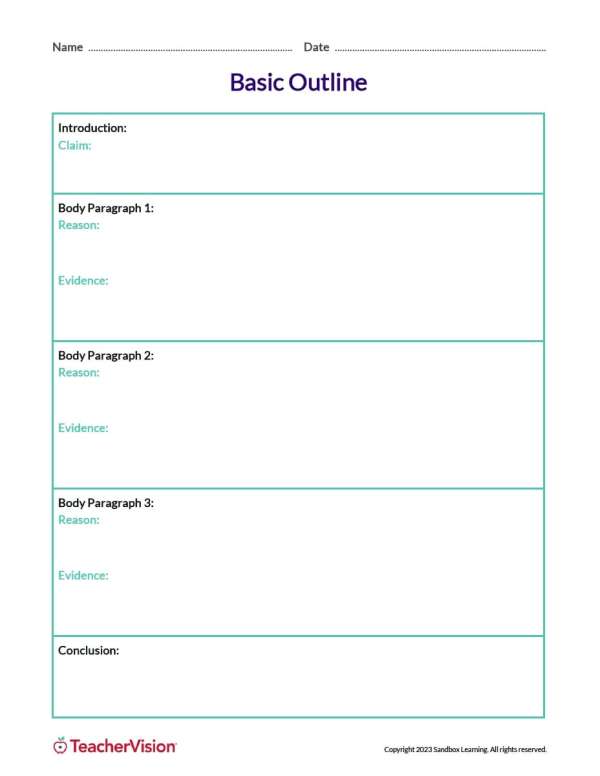

Argumentative Writing Graphic Organizer

Guide your students' writing with this set of three multi-leveled argumentative writing graphic organizers.

Use this essay outline template for students who either do not need much support in writing a comprehensive argumentative essay and need only to jot down ideas or students who should just focus on Claim-Reason-Evidence for this round as a scaffolded step.

The claim should be an opinion or something that other people could reasonably disagree with. Reasons should each be different ideas that support their claim, and evidence should be facts -- either found through research or commonly known.

What's Included:

- Set of three graphic organizers: Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced

Fields Covered:

- Introduction- Argument Claim

- Body Paragraph 1- Argument: Reason and Evidence and Examples

- Body Paragraph 2- Argument: Reason and Evidence and Examples

- Body Paragraph 3- Counter Argument: Reason and Evidence

Featured Middle School Resources

Related Resources

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This article explores some ways I’ve applied graphic organizers and visual planning strategies to the work of argument writing—which is perhaps the mode I consider the most challenging in the classroom.

The Persuasion Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to map out their arguments for a persuasive essay or debate. Students begin by determining their goal or thesis. They then identify three reasons to support their argument, and three facts or examples to validate each reason.

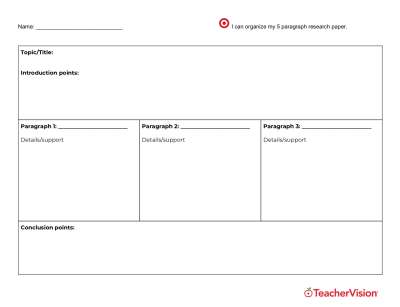

Support your claim with at least three supporting reasons – in logical order. Next, give evidence to support your reasons. Make at least one (1) counter-claim (the other side of the argument). Next, provide facts or examples to refute it (make a rebuttal).

Graphic Organizer for the Argument Essay. Grab the reader’s attention!!! Start with a great opening sentence to get the reader’s attention—a quote, an outrageous, surprising, or shocking fact, a relevant statistic or rhetorical question. Topic Sentence. Evidence (remember to cite)

Guide your students' writing with this set of three multi-leveled argumentative writing graphic organizers. Use this essay outline template for students who either do not need much support in writing a comprehensive argumentative essay and need only to jot down ideas or students who should just focus on Claim-Reason-Evidence for this round as a ...

Graphic Organizer for your Argument/Editorial Essay (OUTLINE) Directions: Below is a template outline to help you in structuring your ideas for your essay. This is due on Monday, Feb. 1st, 2016. This will be the first stage BEFORE typing.

FIGURE 20.1 Graphic Organizer for an Argument Essay. Urge readers to take action. *The thesis statement may appear anywhere within the argument.

CONCLUSION Paragraph. Ø Summary and restatement of CLAIM –. Ø Call to Action (what you want your readers to do) Ø End Statement (refer back to attention getting hook)

Use this graphic organizer to plan your analytical/persuasive essay. The introduction should start with a broad statement and end with your thesis statement, which “zooms in” on the points you will explore in more depth. The body paragraphs must contain evidence to support your thesis.

Paragraph 1: INTRODUCTION. Attention‐grabbing opening: Background of Issue: My position: (May include counter‐argument)