61 intriguing psychology research topics to explore

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

Brittany Ferri, PhD, OTR/L

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Psychology is an incredibly diverse, critical, and ever-changing area of study in the medical and health industries. Because of this, it’s a common area of study for students and healthcare professionals.

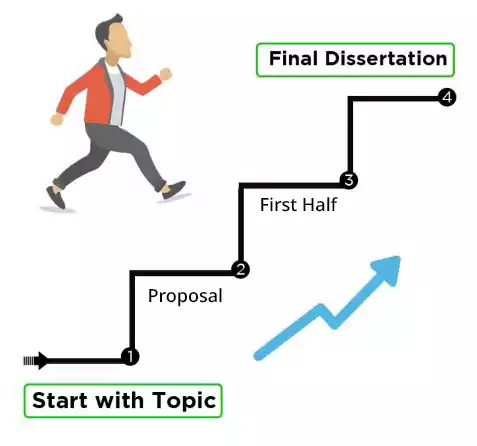

We’re walking you through picking the perfect topic for your upcoming paper or study. Keep reading for plenty of example topics to pique your interest and curiosity.

- How to choose a psychology research topic

Exploring a psychology-based topic for your research project? You need to pick a specific area of interest to collect compelling data.

Use these tips to help you narrow down which psychology topics to research:

Focus on a particular area of psychology

The most effective psychological research focuses on a smaller, niche concept or disorder within the scope of a study.

Psychology is a broad and fascinating area of science, including everything from diagnosed mental health disorders to sports performance mindset assessments.

This gives you plenty of different avenues to explore. Having a hard time choosing? Check out our list of 61 ideas further down in this article to get started.

Read the latest clinical studies

Once you’ve picked a more niche topic to explore, you need to do your due diligence and explore other research projects on the same topic.

This practice will help you learn more about your chosen topic, ask more specific questions, and avoid covering existing projects.

For the best results, we recommend creating a research folder of associated published papers to reference throughout your project. This makes it much easier to cite direct references and find inspiration down the line.

Find a topic you enjoy and ask questions

Once you’ve spent time researching and collecting references for your study, you finally get to explore.

Whether this research project is for work, school, or just for fun, having a passion for your research will make the project much more enjoyable. (Trust us, there will be times when that is the only thing that keeps you going.)

Now you’ve decided on the topic, ask more nuanced questions you might want to explore.

If you can, pick the direction that interests you the most to make the research process much more enjoyable.

- 61 psychology topics to research in 2024

Need some extra help starting your psychology research project on the right foot? Explore our list of 61 cutting-edge, in-demand psychology research topics to use as a starting point for your research journey.

- Psychology research topics for university students

As a university student, it can be hard to pick a research topic that fits the scope of your classes and is still compelling and unique.

Here are a few exciting topics we recommend exploring for your next assigned research project:

Mental health in post-secondary students

Seeking post-secondary education is a stressful and overwhelming experience for most students, making this topic a great choice to explore for your in-class research paper.

Examples of post-secondary mental health research topics include:

Student mental health status during exam season

Mental health disorder prevalence based on study major

The impact of chronic school stress on overall quality of life

The impacts of cyberbullying

Cyberbullying can occur at all ages, starting as early as elementary school and carrying through into professional workplaces.

Examples of cyberbullying-based research topics you can study include:

The impact of cyberbullying on self-esteem

Common reasons people engage in cyberbullying

Cyberbullying themes and commonly used terms

Cyberbullying habits in children vs. adults

The long-term effects of cyberbullying

- Clinical psychology research topics

If you’re looking to take a more clinical approach to your next project, here are a few topics that involve direct patient assessment for you to consider:

Chronic pain and mental health

Living with chronic pain dramatically impacts every aspect of a person’s life, including their mental and emotional health.

Here are a few examples of in-demand pain-related psychology research topics:

The connection between diabetic neuropathy and depression

Neurological pain and its connection to mental health disorders

Efficacy of meditation and mindfulness for pain management

The long-term effects of insomnia

Insomnia is where you have difficulty falling or staying asleep. It’s a common health concern that impacts millions of people worldwide.

This is an excellent topic because insomnia can have a variety of causes, offering many research possibilities.

Here are a few compelling psychology research topics about insomnia you could investigate:

The prevalence of insomnia based on age, gender, and ethnicity

Insomnia and its impact on workplace productivity

The connection between insomnia and mental health disorders

Efficacy and use of melatonin supplements for insomnia

The risks and benefits of prescription insomnia medications

Lifestyle options for managing insomnia symptoms

The efficacy of mental health treatment options

Management and treatment of mental health conditions is an ever-changing area of study. If you can witness or participate in mental health therapies, this can make a great research project.

Examples of mental health treatment-related psychology research topics include:

The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients with severe anxiety

The benefits and drawbacks of group vs. individual therapy sessions

Music therapy for mental health disorders

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with depression

- Controversial psychology research paper topics

If you are looking to explore a more cutting-edge or modern psychology topic, you can delve into a variety of controversial and topical options:

The impact of social media and digital platforms

Ever since access to internet forums and video games became more commonplace, there’s been growing concern about the impact these digital platforms have on mental health.

Examples of social media and video game-related psychology research topics include:

The effect of edited images on self-confidence

How social media platforms impact social behavior

Video games and their impact on teenage anger and violence

Digital communication and the rapid spread of misinformation

The development of digital friendships

Psychotropic medications for mental health

In recent years, the interest in using psychoactive medications to treat and manage health conditions has increased despite their inherently controversial nature.

Examples of psychotropic medication-related research topics include:

The risks and benefits of using psilocybin mushrooms for managing anxiety

The impact of marijuana on early-onset psychosis

Childhood marijuana use and related prevalence of mental health conditions

Ketamine and its use for complex PTSD (C-PTSD) symptom management

The effect of long-term psychedelic use and mental health conditions

- Mental health disorder research topics

As one of the most popular subsections of psychology, studying mental health disorders and how they impact quality of life is an essential and impactful area of research.

While studies in these areas are common, there’s always room for additional exploration, including the following hot-button topics:

Anxiety and depression disorders

Anxiety and depression are well-known and heavily researched mental health disorders.

Despite this, we still don’t know many things about these conditions, making them great candidates for psychology research projects:

Social anxiety and its connection to chronic loneliness

C-PTSD symptoms and causes

The development of phobias

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) behaviors and symptoms

Depression triggers and causes

Self-care tools and resources for depression

The prevalence of anxiety and depression in particular age groups or geographic areas

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a complex and multi-faceted area of psychology research.

Use your research skills to learn more about this condition and its impact by choosing any of the following topics:

Early signs of bipolar disorder

The incidence of bipolar disorder in young adults

The efficacy of existing bipolar treatment options

Bipolar medication side effects

Cognitive behavioral therapy for people with bipolar

Schizoaffective disorder

Schizoaffective disorder is often stigmatized, and less common mental health disorders are a hotbed for new and exciting research.

Here are a few examples of interesting research topics related to this mental health disorder:

The prevalence of schizoaffective disorder by certain age groups or geographic locations

Risk factors for developing schizoaffective disorder

The prevalence and content of auditory and visual hallucinations

Alternative therapies for schizoaffective disorder

- Societal and systematic psychology research topics

Modern society’s impact is deeply enmeshed in our mental and emotional health on a personal and community level.

Here are a few examples of societal and systemic psychology research topics to explore in more detail:

Access to mental health services

While mental health awareness has risen over the past few decades, access to quality mental health treatment and resources is still not equitable.

This can significantly impact the severity of a person’s mental health symptoms, which can result in worse health outcomes if left untreated.

Explore this crucial issue and provide information about the need for improved mental health resource access by studying any of the following topics:

Rural vs. urban access to mental health resources

Access to crisis lines by location

Wait times for emergency mental health services

Inequities in mental health access based on income and location

Insurance coverage for mental health services

Systemic racism and mental health

Societal systems and the prevalence of systemic racism heavily impact every aspect of a person’s overall health.

Researching these topics draws attention to existing problems and contributes valuable insights into ways to improve access to care moving forward.

Examples of systemic racism-related psychology research topics include:

Access to mental health resources based on race

The prevalence of BIPOC mental health therapists in a chosen area

The impact of systemic racism on mental health and self-worth

Racism training for mental health workers

The prevalence of mental health disorders in discriminated groups

LGBTQIA+ mental health concerns

Research about LGBTQIA+ people and their mental health needs is a unique area of study to explore for your next research project. It’s a commonly overlooked and underserved community.

Examples of LGBTQIA+ psychology research topics to consider include:

Mental health supports for queer teens and children

The impact of queer safe spaces on mental health

The prevalence of mental health disorders in the LGBTQIA+ community

The benefits of queer mentorship and found family

Substance misuse in LQBTQIA+ youth and adults

- Collect data and identify trends with Dovetail

Psychology research is an exciting and competitive study area, making it the perfect choice for projects or papers.

Take the headache out of analyzing your data and instantly access the insights you need to complete your next psychology research project by teaming up with Dovetail today.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 30 January 2024

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 12 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 31 January 2024

Last updated: 23 January 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Clinical Psychology Research Paper Topics

This page provides a comprehensive list of clinical psychology research paper topics , designed to support students navigating the complexities of mental health studies. Aimed at fostering a deeper understanding of psychological assessment, therapeutic methods, and the myriad issues faced by individuals with mental health disorders, these topics cover a broad spectrum of areas within clinical psychology. From exploring the efficacy of different therapeutic approaches to examining the impact of cultural and social factors on mental health, this list serves as a vital resource for students seeking to contribute meaningful research to the field. Whether you are interested in the latest trends in neuropsychology, the intricacies of forensic psychology, or the challenges of mental health in children and adolescents, these carefully selected topics offer a rich foundation for your academic inquiries and research endeavors.

100 Clinical Psychology Research Paper Topics

Clinical psychology plays a pivotal role in understanding, diagnosing, and treating mental health issues, standing at the forefront of efforts to improve psychological well-being and quality of life. This field combines rigorous academic research with practical therapeutic applications, making it essential for students to engage with a wide range of topics that reflect the diversity and complexity of human psychology. The topics listed here span foundational theories, cutting-edge therapeutic interventions, and the nuanced interplay between mental health and societal factors, offering students a comprehensive overview of the landscape of clinical psychology.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- The history and evolution of clinical psychology

- Major theoretical approaches in clinical psychology

- The role of clinical psychology in integrated healthcare

- Ethics in clinical practice and research

- The impact of technology on clinical psychology

- Psychoanalytic theories and techniques

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy: Foundations and evolutions

- The scientist-practitioner model

- Measurement and evaluation in clinical psychology

- Training and professional development in clinical psychology

- Psychological testing and assessment tools

- Neuropsychological testing for cognitive disorders

- Behavioral assessment strategies

- The DSM-5 and diagnostic criteria

- Cultural competence in psychological assessment

- The role of functional assessments in clinical settings

- Innovations in diagnostic methodologies

- Assessing risk and protective factors

- Personality assessment instruments

- Challenges in diagnosing complex cases

- Comparative effectiveness of psychotherapeutic techniques

- Mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions

- The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic therapies

- Innovations in cognitive-behavioral therapy

- Group therapy dynamics and outcomes

- Teletherapy and digital interventions

- Integrative and holistic therapeutic models

- The therapeutic alliance and outcome research

- Psychotherapy for chronic illness

- Ethical considerations in therapeutic practices

- Advances in understanding and treating depression

- Anxiety disorders: Phenomenology and treatment

- Schizophrenia and psychotic disorders

- Personality disorders: Challenges and therapeutic strategies

- Eating disorders: From etiology to recovery

- Bipolar disorder across the lifespan

- Substance use disorders and dual diagnoses

- Post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma-informed care

- Child and adolescent mental health disorders

- The psychology of chronic pain and its management

- Developmental psychopathology

- Behavioral interventions in schools

- Autism spectrum disorders: Diagnosis and intervention

- Adolescent mental health and identity formation

- Parent-child interactions and therapy outcomes

- The impact of technology on youth mental health

- Eating disorders in adolescents

- Childhood anxiety and depression

- ADHD: Contemporary approaches to assessment and treatment

- The role of family therapy in treating childhood disorders

- The brain-behavior relationship

- Cognitive rehabilitation strategies

- Neuroimaging techniques in clinical assessment

- Neuropsychological impacts of neurological disorders

- Aging and cognitive decline

- Pediatric neuropsychology

- Concussions and traumatic brain injury

- The neuropsychology of emotion

- Memory disorders and dementia

- Psychopharmacology for neuropsychological disorders

- The psychology of chronic illness management

- Behavioral interventions for physical health

- Psychoneuroimmunology: Stress and immunity

- Health behavior change models and strategies

- The role of psychology in pain management

- Psychological aspects of cancer care

- The impact of sleep on mental and physical health

- Eating behaviors and nutrition psychology

- The psychology of addiction and substance misuse

- Mind-body interventions in health care

- Psychological assessment in legal contexts

- Competency and insanity evaluations

- The psychology of criminal behavior

- Treatment of offenders and risk assessment

- Victimology and psychological impacts of crime

- Eyewitness testimony and memory reliability

- The role of psychology in law enforcement

- Ethical dilemmas in forensic psychology

- Child custody and family law

- Psychological interventions in correctional settings

- Cross-cultural psychology and mental health

- The impact of socioeconomic status on mental health

- Gender and sexuality issues in clinical psychology

- Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care

- The psychology of immigration and acculturation

- Indigenous mental health and healing practices

- Stigma and mental illness

- Community psychology and social change

- The role of religion and spirituality in therapy

- Cultural competence in therapeutic settings

- The future of psychotherapy: Trends and predictions

- Virtual reality and augmented reality in therapy

- The use of artificial intelligence in mental health services

- Digital phenotyping and mobile health

- Genomics and personalized medicine in mental health

- Ethical considerations in the use of technology

- The impact of social media on mental health

- Neurofeedback and biofeedback

- E-mental health interventions and apps

- Integrating technology into traditional therapeutic models

The depth and breadth of clinical psychology research paper topics reflect the field’s dynamic nature and its critical role in addressing mental health issues. These topics not only offer students a wealth of areas to explore but also the opportunity to contribute meaningful insights and advancements to the discipline. By delving into these diverse areas of clinical psychology, students can play a part in shaping the future of mental health treatment and understanding, enriching their academic journey and the field at large.

What is Clinical Psychology

Introduction to the Field of Clinical Psychology

Clinical psychology merges the science of psychology with the treatment of complex human problems, making it one of the most critical areas within the realm of psychological study and application. It encompasses a wide range of practices, including assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental disorders. Clinical psychologists employ various therapeutic approaches to treat individuals across the lifespan, dealing with everything from minor stress and life transitions to severe psychopathology.

Importance of Research in Advancing Clinical Practice and Understanding

The bedrock of clinical psychology lies in rigorous research. Research in this field serves multiple purposes: it enhances our understanding of the etiology and progression of mental disorders, evaluates the efficacy of therapeutic interventions, and tests new treatment approaches. Without research, clinical practice would lack the empirical basis necessary for effectively treating patients. Research ensures that clinical interventions are both safe and effective, thereby safeguarding the well-being of clients and advancing the field.

Exploration of Diverse Research Topics in Clinical Psychology

Research in clinical psychology is as diverse as the field itself, covering a wide array of topics that reflect the complexity of human behavior and mental health. These topics range from understanding the neurological underpinnings of mental disorders to exploring the effectiveness of new psychotherapeutic techniques. Research in this field also investigates the social, cultural, and environmental factors that influence mental health, thereby contributing to more holistic approaches to treatment and prevention. This diversity not only broadens the scope of clinical psychology but also ensures that the field remains responsive to the changing needs of society.

Recent Advancements and Innovations in Clinical Psychology Research

The field of clinical psychology has witnessed significant advancements and innovations, thanks in part to technological progress and a deeper understanding of psychological processes. Recent research has explored the potential of teletherapy, digital interventions, and mobile health applications, providing access to mental health services for individuals who might otherwise face barriers to treatment. Additionally, advances in neuroimaging and psychopharmacology have offered new insights into the biological aspects of mental disorders, leading to more targeted and effective treatments. These advancements underscore the dynamic nature of clinical psychology and its continuous evolution in response to scientific discoveries and societal changes.

Ethical Considerations in Clinical Psychology Research

Ethical considerations hold paramount importance in clinical psychology research, given the vulnerability of the populations often involved. Ethical guidelines ensure that research is conducted in a manner that respects the dignity, rights, and welfare of participants. This includes obtaining informed consent, ensuring confidentiality, and minimizing potential harm. Ethical research practices are crucial for maintaining trust between researchers and participants and for upholding the integrity of the field.

Future Directions for Research in Clinical Psychology

Looking ahead, the field of clinical psychology is poised to explore new frontiers that promise to further enhance our understanding of mental health and improve treatment outcomes. One area of future research may focus on personalized medicine, tailoring interventions to the unique genetic, biological, and environmental factors of each individual. Another promising area involves integrating clinical psychology more closely with other disciplines, such as neuroscience and public health, to develop more comprehensive and effective approaches to mental health care. Additionally, as society continues to evolve, ongoing research will be necessary to address the psychological impacts of emerging societal challenges.

The Impact of Research on the Evolution of Clinical Psychology Practices

The trajectory of clinical psychology is indelibly shaped by research. It is through the diligent efforts of researchers that the field continues to advance, offering new insights into the human psyche and more effective treatments for mental disorders. Research in clinical psychology not only enriches our understanding of mental health but also plays a critical role in shaping policies, therapeutic practices, and public perceptions of mental health issues. As we move forward, the continued emphasis on research will ensure that clinical psychology remains a vital force for good in the lives of individuals and communities worldwide, epitomizing the profound impact that research has on the evolution of clinical practices.

iResearchNet’s Writing Services

At iResearchNet, we recognize the unique challenges and complexities involved in crafting research papers within the field of clinical psychology. That’s why we offer specialized writing services tailored specifically for clinical psychology students and professionals. Our mission is to support your academic and research endeavors by providing custom, high-quality papers that reflect the latest advancements and ethical considerations in clinical psychology. Whether you’re exploring novel therapeutic interventions, dissecting complex case studies, or examining the societal impact of mental health issues, iResearchNet is your partner in navigating the intricacies of clinical psychology research.

- Expert Writers with Advanced Degrees in Clinical Psychology : Our team consists of professionals who not only have advanced degrees in clinical psychology but also possess extensive research and writing experience in the field.

- Custom Papers Crafted to Meet Individual Academic Requirements : We understand that each research project has unique requirements, and we tailor our services to meet your specific academic needs.

- Comprehensive Research Incorporating the Latest Studies and Findings : Our writers stay abreast of current research trends and findings in clinical psychology to ensure your paper is informed by the latest insights.

- Adherence to All Academic Formatting Guidelines : Whether you need your paper formatted in APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, or Harvard style, our writers are experts in adhering to academic formatting guidelines.

- Unwavering Commitment to Producing Top-Quality Work : Quality is at the heart of what we do. We’re committed to delivering papers that meet the highest standards of academic excellence.

- Personalized Solutions for Each Research Topic : We offer customized writing solutions, ensuring that your paper is tailored to the specific requirements of your research topic.

- Competitive Pricing Designed with Students in Mind : Our pricing model is designed to be affordable for students, balancing high-quality services with competitive pricing.

- Capacity to Meet Even the Most Urgent Deadlines : We understand the pressures of academic deadlines and are equipped to handle urgent requests, ensuring timely completion of your project.

- Assurance of On-Time Delivery for All Projects : Timeliness is crucial, and we guarantee the on-time delivery of your research paper, allowing you to submit your work with confidence.

- Round-the-Clock Support for Queries and Updates : Our customer support team is available 24/7 to address any queries you may have and provide updates on your project’s progress.

- Strict Privacy Policies to Protect Client Information : We take your privacy seriously and adhere to strict policies to protect your personal and academic information.

- User-Friendly System for Tracking Order Progress : Our online platform makes it easy for you to track the progress of your order, offering transparency and peace of mind.

- Money-Back Guarantee if Expectations Are Not Met : We stand by the quality of our work. If your paper does not meet your expectations, we offer a money-back guarantee.

At iResearchNet, our dedication to supporting students and professionals in their clinical psychology research endeavors is unwavering. We understand the critical importance of your academic and professional contributions to the field of clinical psychology. By providing high-quality, customized research papers, we aim to help you advance your academic journey and make meaningful contributions to the field. Choose iResearchNet for your clinical psychology research paper needs and experience the difference that professional, tailored writing services can make in achieving academic excellence.

Advance Your Academic Journey with Custom Research Papers!

Embark on a path of academic distinction in the field of clinical psychology with iResearchNet at your side. Our expert writing services are meticulously designed to cater to your unique research paper needs, empowering you to delve deeper into the complexities of mental health and therapeutic practices. Whether you’re tackling the intricacies of psychological assessments, exploring innovative therapeutic approaches, or analyzing the societal implications of mental health policies, our custom research papers are your gateway to academic excellence.

We invite you to take full advantage of the unparalleled support and expertise offered by iResearchNet. Our process is streamlined for your convenience, ensuring that ordering your custom research paper is as straightforward as possible. From the moment you reach out to us, you’ll experience the comprehensive support that sets us apart. Our team is dedicated to your success, offering personalized assistance every step of the way, from initial consultation to the final delivery of your project.

Don’t let the opportunity to elevate your academic and professional prospects pass you by. Choose iResearchNet for your clinical psychology research paper needs and step confidently into your future, armed with insights and knowledge that will distinguish your work in the field. Your journey towards academic and professional excellence in clinical psychology begins here, with iResearchNet’s commitment to providing you with top-quality, customized research papers.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Clinical Psychology Research Topics

Stumped for ideas? Start here

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Clinical psychology research is one of the most popular subfields in psychology. With such a wide range of topics to cover, figuring out clinical psychology research topics for papers, presentations, and experiments can be tricky.

Clinical Psychology Research Topic Ideas

Topic choices are only as limited as your imagination and assignment, so try narrowing the possibilities down from general questions to the specifics that apply to your area of specialization.

Here are just a few ideas to start the process:

- How does social media influence how people interact and behave?

- Compare and contrast two different types of therapy . When is each type best used? What disorders are best treated with these forms of therapy? What are the possible limitations of each type?

- Compare two psychological disorders . What are the signs and symptoms of each? How are they diagnosed and treated?

- How does "pro ana," "pro mia," " thinspo ," and similar content contribute to eating disorders? What can people do to overcome the influence of these sites?

- Explore how aging influences mental illness. What particular challenges elderly people diagnosed with mental illness face?

- Explore factors that influence adolescent mental health. Self-esteem and peer pressure are just a couple of the topics you might explore in greater depth.

- Explore the use and effectiveness of online therapy . What are some of its advantages and disadvantages ? How do those without technical literacy navigate it?

- Investigate current research on the impact of media violence on children's behavior.

- Explore anxiety disorders and their impact on daily functioning. What new therapies are available?

- What are the risk factors for depression ? Explore the potential risks as well as any preventative strategies that can be used.

- How do political and social climates affect mental health?

- What are the long-term effects of childhood trauma? Do children continue to experience the effects later in adulthood? What treatments are available for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) in childhood?

- What impact does substance use disorder have on the family? How can family members help with treatment?

- What types of therapy are most effective for childhood behavioral issues ?

Think of books you have read, research you have studied, and even experiences and interests from your own life. If you've ever wanted to dig further into something that interested you, this is a great opportunity. The more engaged you are with the topic, the more excited you will be to put the work in for a great research paper or presentation.

Consider Scope, Difficulty, and Suitability

Picking a good research topic is one of the most important steps of the research process. A too-general topic can feel overwhelming; likewise, one that's very specific might have limited supporting information. Spend time reading online or exploring your library to make sure that plenty of sources to support your paper, presentation, or experiment are available.

If you are doing an experiment , checking with your instructor is a must. In many cases, you might have to submit a proposal to your school's human subjects committee for approval. This committee will ensure that any potential research involving human subjects is done in a safe and ethical way.

Once you have chosen a topic that interests you, run the idea past your course instructor. (In some cases, this is required.) Even if you don't need permission from the instructor, getting feedback before you delve into the research process is helpful.

Your instructor can draw from a wealth of experience to offer good suggestions and ideas for your research, including the best available resources pertaining to the topic. Your school librarian may also be able to provide assistance regarding the resources available for use at the library, including online journal databases.

Kim WO. Institutional review board (IRB) and ethical issues in clinical research . Korean Journal of Anesthesiology . 2012;62(1):3-12. doi:10.4097/kjae.2012.62.1.3

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Mental Health and Clinical Psychological Science in the Time of COVID-19: Challenges, Opportunities, and a Call to Action

June gruber, lee anna clark, jonathan s abramowitz, amelia aldao, tammy chung, erika e forbes, gordon c nagayama hall, stephen p hinshaw, steven d hollon, daniel n klein, robert w levenson, jane mendle, enrique w neblett, bunmi o olatunji, mitchell j prinstein, jonathan rottenberg, anne marie albano, jessica l borelli, joanne davila, dylan g gee, lauren s hallion, stefan g hofmann, jutta joormann, alan e kazdin, annette m la greca, angus w macdonald iii, katie a mclaughlin, adam bryant miller, matthew nock, jacqueline b persons, david c rozek, george m slavich, jessica l schleider, bethany a teachman, lauren m weinstock.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

All author names for the full article are listed alphabetically (by last name) after the four coordinating authors. Authorship contributions are as follows: June Gruber: Oversaw and organized overall article ideas and editing; contributed to writing the introduction, middle-aged adulthood, and concluding comments; approved final article; Mitchell J. Prinstein: Oversaw and organized overall article ideas and editing; contributed to writing the introduction, suicide, adolescence, social relationships, and concluding comments; approved final article; Lee Anna Clark: Edited the overall article, contributed to writing on assessment and treatment challenges, training models for mental health delivery; approved final article; Jonathan Rottenberg: Edited overall article, contributed to writing the introduction; approved final article; Jonathan S. Abramowitz: Contributed to writing on anxiety and depression; approved final article; Anne Marie Albano: Contributed to writing on adolescents and young adults; approved final article; Amelia Aldao: Contributed to writing on assessment and treatment challenges, training models for mental health delivery; approved final article; Jessica L. Borelli: Contributed to writing on older adults, family and interpersonal dynamics; approved final article; Tammy Chung: Contributed to writing on section pertaining to substance use disorders; approved final article; Joanne Davila: Contributed to writing on family and interpersonal dynamics; approved final article; Erika E. Forbes: Contributed to writing on anxiety and depression, adolescents and young adults, research agenda and priorities; approved final article; Dylan G. Gee: Contributed to writing on childhood; approved final article; Gordon C. Nagayama Hall: Contributed to writing on marginalized racial and ethnic groups and health disparities; approved final article; Lauren S. Hallion: Contributed to writing on anxiety and depression, assessment and treatment challenges; approved final article; Stephen P. Hinshaw: Contributed to writing on stigma; approved final article; Stefan G. Hofmann: Contributed to writing on anxiety and depression; reviewed and edited overall article; approved final article; Steven D. Hollon: Contributed to writing on anxiety and depression; approved final article; Jutta Joormann: Contributed to writing on anxiety and depression; approved final article; Alan E. Kazdin: Contributed to writing on clinical science psychology delivery; approved final article; Daniel N. Klein: Contributed to writing on anxiety and depression, adolescents and young adults; approved final article; Annette M. La Greca: Contributed to writing on PTSD; approved final article; Robert W. Levenson: Contributed to writing on older adults; approved final article; Angus W. MacDonald III: Contributed to writing the introduction, psychosis and other severe mental disorders; approved final article; Dean McKay: Contributed to writing on anxiety and depression, mental health care; approved final article; Katie A. McLaughlin: Contributed to writing on childhood, anxiety and depression, mental health disparities; approved final article; Jane Mendle: Contributed to writing on adolescents and young adults; approved final article; Adam Bryant Miller: Contributed to writing on suicide, childhood, adolescents and young adults; approved final article; Enrique W. Neblett: Contributed to writing on members of marginalized racial and ethnic groups and health disparities; approved final article; Matthew Nock: Contributed to writing on suicide; approved final article; Bunmi O. Olatunji: Contributed to writing on mental health care; approved final article; Jacqueline B. Persons: Contributed to writing on assessment and treatment challenges; approved final article; David C. Rozek: Contributed to writing on suicide, research agenda and priorities; approved final article; Jessica L. Schleider: Contributed to writing on training models for mental health delivery and interventions; approved final article; George M. Slavich: Contributed to writing on stress and loss of protective factors; anxiety and depression; approved final article; Bethany A. Teachman: Contributed to writing on training models for mental health delivery and care; approved final article; Vera J. Vine: Contributed to writing on research agenda and priorities; approved final article; Lauren M. Weinstock: Contributed to writing on training models for mental health delivery; approved final article.

June Gruber served as lead for conceptualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Mitchell J. Prinstein served as lead for conceptualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Lee Anna Clark served as lead for writing – review and editing. Jonathan Rottenberg served as lead for writing – review and editing. Lee Anna Clark, Jonathan Rottenberg, Jonathan S. Abramowitz, Anne Marie Albano, Amelia Aldao, Jessica L. Borelli, Tammy Chung, Joanne Davila, Erika E. Forbes, Dylan G. Gee, Gordon C. Nagayama Hall, Lauren S. Hallion, Stephen P. Hinshaw, Stefan G. Hofmann, Steven D. Hollon, Jutta Joormann, Alan E. Kazdin, Daniel N. Klein, Annette M. La Greca, Robert W. Levenson, Angus W. MacDonald III, Dean McKay, Katie A. McLaughlin, Jane Mendle, Adam Bryant Miller, Enrique W. Neblett, Matthew Nock, Bunmi O. Olatunji, Jacqueline B. Persons, David C. Rozek, Jessica L. Schleider, George M. Slavich, Bethany A. Teachman, Vera J. Vine, and Lauren M. Weinstock contributed to conceptualization equally. Lee Anna Clark, Jonathan Rottenberg, Jonathan S. Abramowitz, Anne Marie Albano, Amelia Aldao, Jessica L. Borelli, Tammy Chung, Joanne Davila, Erika E. Forbes, Dylan G. Gee, Gordon C. Nagayama Hall, Lauren S. Hallion, Stephen P. Hinshaw, Stefan G. Hofmann, Steven D. Hollon, Jutta Joormann, Alan E. Kazdin, Daniel N. Klein, Annette M. La Greca, Robert W. Levenson, Angus W. MacDonald III, Dean McKay, Katie A. McLaughlin, Jane Mendle, Adam Bryant Miller, Enrique W. Neblett, Matthew Nock, Bunmi O. Olatunji, Jacqueline B. Persons, David C. Rozek, Jessica L. Schleider, George M. Slavich, Bethany A. Teachman, Vera J. Vine, and Lauren M. Weinstock contributed to writing – original draft equally. Jonathan S. Abramowitz, Anne Marie Albano, Amelia Aldao, Jessica L. Borelli, Tammy Chung, Joanne Davila, Erika E. Forbes, Dylan G. Gee, Gordon C. Nagayama Hall, Lauren S. Hallion, Stephen P. Hinshaw, Stefan G. Hofmann, Steven D. Hollon, Jutta Joormann, Alan E. Kazdin, Daniel N. Klein, Annette M. La Greca, Robert W. Levenson, Angus W. MacDonald III, Dean McKay, Katie A. McLaughlin, Jane Mendle, Adam Bryant Miller, Enrique W. Neblett, Matthew Nock, Bunmi O. Olatunji, Jacqueline B. Persons, David C. Rozek, Jessica L. Schleider, George M. Slavich, Bethany A. Teachman, Vera J. Vine, and Lauren M. Weinstock contributed to writing – review and editing equally.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to June Gruber, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Colorado Boulder, 345 UCB Muenzinger D321C, Boulder, CO 80309-0345, or to Mitchell J. Prinstein, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 240 Davie Hall, CB 3270, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3270. [email protected] or [email protected]

Issue date 2021 Apr.

COVID-19 presents significant social, economic, and medical challenges. Because COVID-19 has already begun to precipitate huge increases in mental health problems, clinical psychological science must assert a leadership role in guiding a national response to this secondary crisis. In this article, COVID-19 is conceptualized as a unique, compounding, multidimensional stressor that will create a vast need for intervention and necessitate new paradigms for mental health service delivery and training. Urgent challenge areas across developmental periods are discussed, followed by a review of psychological symptoms that likely will increase in prevalence and require innovative solutions in both science and practice. Implications for new research directions, clinical approaches, and policy issues are discussed to highlight the opportunities for clinical psychological science to emerge as an updated, contemporary field capable of addressing the burden of mental illness and distress in the wake of COVID-19 and beyond.

Keywords: clinical psychological science, clinical psychology, mental health, treatment, COVID-19

COVID-19, the illness produced by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been associated with some of the greatest social, economic, and medical challenges of the 21st century. Between November 2019, when the outbreak began, and early May 2020, over 4.6 million people worldwide tested positive for infection with the virus, and more than 300,000 have died. Understandably, the first response phase focused on reducing infection rates, thereby preserving hospital resources (i.e., “flattening the curve”; Adhanom Ghebreyesus, 2020 ; Gruber & Rottenberg, 2020 ). As such, the initial contribution of clinical psychological science was attenuated relative to such fields as virology, epidemiology, and public health. Increasingly, however, it is becoming clear that the pandemic confers grave and potentially long-term mental health implications for the nation. The toxic psychosocial stressors that the pandemic has created (e.g., physical risks, daily disruptions, uncertainty, social isolation, financial loss, etc.) are well known to affect mental health (and thereby also physical health) adversely, and collectively encompass many characteristics that have been identified as having the greatest negative effects. Moreover, preliminary evidence suggests that the virus has direct behavioral-health sequelae and exacerbates existing psychopathology ( Adhanom Ghebreyesus, 2020 ). Accordingly, the field of clinical psychological science must play a leadership role in guiding a national response for the foreseeable future.

There are three ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic may be particularly, and perhaps uniquely, detrimental to mental health. First, it is long term and widespread, with an uncertain end date; the stakes are high, the disruption to daily routines is severe, and the loss of resources to meet both immediate (e.g., food, cleaning supplies) and future needs (e.g., due to unemployment) is significant.

Second, the COVID-19 pandemic is a multidimensional stressor, affecting individual, family, educational, occupational, and medical systems, with broader implications for the macrosystem, as it exacerbates political rifts, cultural and economic disparities, and prejudicial beliefs. Concerns regarding interpersonal disruption may be particularly relevant for understanding its psychological effects and both physical and psychological outcomes. Reduced social interaction is a notable risk factor for mental health difficulties and the negative impact of loneliness on mental and physical health is well-documented ( Cacioppo, Grippo, London, Goossens, & Cacioppo, 2015 ). Many individuals are facing serious illness—and thus, prolonged separation or even death—of loved ones, made even more difficult by interruptions in typical modes of grieving (e.g., funerals, spending time with family, sitting shiva, religious services), or by ongoing concerns regarding one’s own or one’s family members’ safety. Social disruptions during COVID-19 also include role confusion and conflict: Many parents are serving as both home-school teachers and care providers while also maintaining occupational responsibilities. These role changes thus increase parental stress and fatigue which, in turn, result in lower parenting satisfaction, self-efficacy, and distress tolerance (e.g., Kinnunen & Mauno, 1998 ). Strict stay-at-home guidelines also confer risk for sustained exposure to many interpersonal sources of adversity (e.g., marital discord, parent–child conflicts, interpersonal threat and deprivation, parental psychopathology, addictive behaviors, unemployment and economic instability, and lack of social support), many of which are known risk factors for child abuse ( Brown, Cohen, Johnson, & Salzinger, 1998 ; Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2013 ) and the onset of psychopathology ( McLaughlin et al., 2012 ).

Third, the protections needed to safeguard against infection necessarily, but ironically, block access to protective factors that are known to reduce the effects of stress (e.g., enjoyable distractions, behavioral activation, social relationships) because they are difficult to employ while adhering to stay-at-home and social-distancing mandates. The lack of protective factors may be especially marked among socially isolated older adults who also are among the most vulnerable to the virus.

This article, therefore, aims to highlight the most urgent areas to address, and to suggest research directions, clinical approaches, and policy issues that need attention. Although numerous scientific fields and psychological subdisciplines, will need to be involved to address a myriad of interrelated relevant issues, this article focuses specifically on necessary contributions from “clinical psychological science,” a sub-field within mental health disciplines that reflects “a broad intellectual commitment to the importance of empirical research, its integration with clinical practice, and the central role that science must play in the training of clinical psychologists” ( Oltmanns & Krasner, 1993 ). 1 Extant findings are used to articulate briefly the unique mental health issues across developmental age levels that are likely to result from COVID-19. Next, acute challenge areas that are likely to emerge during the course of the pandemic are considered. A path forward is then discussed, highlighting new areas for discovery and potential paradigm shifts from traditional models of clinical psychological science implementation. It may be that the COVID-19 pandemic will prompt changes to mental health fields that have long been needed—only now, the changes are required to survive. In short, this article has two main goals: (a) to leverage what is known within clinical psychological science to address the enormous U.S. mental health needs exposed by COVID-19 and (b) to highlight what is unknown, perhaps prompting reforms to practices that are overdue for an update.

Psychological Impacts of COVID-19 Across the Life Span

Within the U. S., government officials and the popular media have begun to recognize the mental health crises that are likely to follow the immediate physical threat associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Substantial research suggests that these needs can now be predicted from theoretical models regarding psychopathology risks and articulated with some clarity and detail. This section provides a brief review of this literature to highlight unique risks applicable to different developmental stages, including childhood, adolescence and young adulthood, middle adulthood, and older adulthood.

Children’s emotional/behavioral responses to COVID-19 are likely to result more from significant disruptions to typical roles and daily routines than an appraisal of the health and economic concomitants of the pandemic. Government-mandated school closures affected more than 45 million children in the U.S. as of this writing May 2020. Worldwide, this included school closures in 138 countries, affecting approximately 80% of school-age children ( Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020 ). In combination with changes in parents’ and caregivers’ schedules or availability, this process has been the most disruptive, prolonged shift to children’s daily lives in many decades, scrambling their familiar routines and reducing the number of adult and peer resources available to them. Indeed, schools are a major point of access to mental health resources for children ( Merikangas et al., 2011 ) and serve as gateways for identification and referral to specialty mental health providers ( Farmer, Burns, Phillips, Angold, & Costello, 2003 ). Importantly, developmental and mental health risks associated with the vast societal changes triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to be felt disproportionately by children living in families with lower economic resources and/or experiencing high levels of adversity prior to the pandemic.

Adolescence

Many forms of psychopathology increase in severity and/or prevalence during adolescence. COVID-19 pandemic-related disruptions are likely to exacerbate developmental vulnerabilities to a wide range of internalizing, externalizing, and health-risk behaviors. Numerous factors may explain the increased risk to adolescents, including an increased exposure to parents’ mental health problems, a loss of important “rite of passage” milestones (e.g., senior prom, graduation), uncertainty about the future, and a loss of autonomy. Yet perhaps the most important impact on adolescent lives will be the significant disruption to peer experiences that are critical for youths’ emotional, moral, behavioral, and identity development ( Prinstein & Giletta, 2016 ). During the COVID-19 crisis, many adolescents have increased their already remarkably frequent use of digital media to compensate for the loss of in-person social interactions, yet emerging research suggests that digitally mediated social interactions may be distinct in form and psychological function from face-to-face experiences ( Prinstein, Nesi, & Telzer, 2020 ). Separated from their peers, adolescents also will miss chances to engage in reward-seeking behaviors that characterize this developmental period, and that often enable opportunities for growth and exploration ( Forbes & Dahl, 2012 ; Tezler, 2016 ).

Young Adulthood

The combination of mental health, financial, and social changes during COVID-19 also poses unique challenges for young adults (e.g., Arnett, 2014 ). Although some young adults will experience many of the same challenges as adolescents with regard to missed rites of passage and disrupted social lives, others who return to living with parents may find a stalling or regression of key developmental milestones, including their independence in sexual relationships, expression of their sexual and gender identity, and ability to engage (or not) in religious, political, or other pursuits of their choice. This can result in unprecedented role confusion if forced into an unwelcome adolescent role (e.g., back living with family after a period of independence) or an adult role for which they feel unprepared (e.g., economic self-sufficiency). In addition to the immediate financial constraints of a tenuous economy and high unemployment, long-term vocational and social growth may be narrowed through curtailed education, limited ability to travel, difficulty obtaining vocational training or experience, and a slow ramp-up of the economy as restrictions begin to ease, with limited employment opportunities for entry-level workers.

Middle Adulthood

Adults in the middle-adulthood life span phase face unique and compounding economic and social stressors during the COVID-19 crisis that put them at heightened risk for mental health challenges. These include economic stressors tied to sudden unemployment or furloughs, and salary cuts that threaten their current and future economic stability. Middle-aged adults with children may also face abrupt role shifts as they transition to full-time homeschool teachers with little to no preparation, while also juggling work demands with little childcare support, which can quickly cause parental burnout and mental exhaustion ( Manjoo, 2020 ). In addition to the immediate financial and caregiving stressors during COVID-19, those middle-aged adults with living parents may additionally face increased anxiety and worry about the health and ability to care for (or even visit) their parents while physical-distancing guidelines are enforced.

Older Adulthood

Older adults are uniquely vulnerable during COVID-19, both physically and psychosocially. Older adults may have a heightened susceptibility to infection and its adverse consequences, and they may experience a loss of usual social support, such as family members visiting ( Garnier-Crussard, Forestier, Gilbert, & Krolak-Salmon, 2020 ). This abrupt physical threat and loss of social resources may increase risk for loneliness, isolation, and depression among older adults (e.g., Armitage & Nellums, in press ). Research during the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak documented that greater levels of stress, anxiety, and social isolation among older adults were associated with higher suicide rates ( Chan, Tang, & Hui, 2006 ; Yip, Cheung, Chau, & Law, 2010 ). Particularly vulnerable are older adults with dementia, which interferes with full cognitive understanding of the threat of the virus and hampers remembering to use safety behaviors (e.g., hand washing, wearing a mask when necessary). Family members providing care for people with dementia (over 16 million in the U.S. alone; Alzheimer’s Association, 2020 ) already are highly vulnerable to mental health problems ( Schulz, O’Brien, Bookwala, & Fleissner, 1995 ). For them, sheltering in place can add to social isolation, reduce access to external resources, and increase burden. Finally, for older adults living in congregated nursing-home facilities, risk of infection spread can be dramatically heightened ( Wang et al., 2020 ).

Psychological Sequelae of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced a complex worldwide stressor, and the strategies used to reduce physical health threats ironically may undercut critical protective factors known to buffer the negative effects of psychological stress. It is thus reasonable to assume that the pandemic will be associated with a substantial, sustained, and potentially severe “mental health curve” that, like the prevalence of the virus itself, will also need flattening given already-insufficient mental health resources in the U.S. Ideally, federal and state resources would be allocated to address mental health needs with the same vigor and attention that has been dedicated toward physical health threats. Yet this response seems unrealistic in light of a long history of inadequate attention to, or funding for mental health; thus, it is incumbent upon clinical psychological scientists and practitioners to conceive of innovative approaches to meet the increased burden of mental illness. This section discusses a model for understanding the psychological sequelae of COVID-19-related phenomena; briefly reviews preliminary, emerging research confirming an increased rate of mental health distress; and then discusses specific presentations of psychopathology that may deserve special attention.

Stress and Loss of Protective Factors

Increased psychological difficulties following the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to result from stress, defined as the physical and psychological responses that occur when situational demands outweigh one’s real or perceived resources to address them ( Brooks et al., 2020 ; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ; Monroe, 2008 ). As noted earlier, this complex stressor is characterized by great uncertainty, life-threatening conditions, prolonged exposure to anxiety-inducing information, and losses (e.g., of loved ones, financial security, daily routines, perceived control, and social roles), as well as actual physical threat. COVID-19 may represent a “perfect storm” of stress with high potential for adverse mental health consequences.

Psychobiological models have described clear associations between stress, the activation of brain systems (e.g., amygdala) that process fear and threat, and the release of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine into the blood-stream (e.g., O’Donovan, Slavich, Epel, & Neylan, 2013 ). These responses are adaptive in the short term, mobilizing needed resources to address acute threats. When prolonged, however, these responses can take a toll on the body known as allostatic load ( McEwen & Stellar, 1993 ), which negatively affects the brain (e.g., hippocampus), cardiovascular system (e.g., high blood pressure), and immune system (e.g., increased inflammation; McEwen & Wingfield, 2003 ). Inflammation, in turn, increases risk for psychopathology and related physical health problems ( Furman et al., 2019 ; Slavich, 2020 ). Populations experiencing increased stress due to COVID-19 are thus likely to suffer from a wide range of mental as well as physical health difficulties.

Several literatures support this supposition. For instance, work on highly disruptive or life-threatening natural and human-made disasters suggests markedly high risk for psychopathology following stress exposure, including increased internalizing and externalizing symptoms across age groups ( Bonanno, Brewin, Kaniasty, & La Greca, 2010 ; La Greca, Silverman, Vernberg, & Roberts, 2002 ). These adverse mental health impacts are most prevalent in vulnerable populations (e.g., those at socioeconomic disadvantage, minority groups; Tang, Liu, Liu, Xue, & Zhang, 2014 ), and various risk factors (e.g., temperamental fear, neural reactivity to emotional stimuli) are associated with more postdisaster symptoms ( Kujawa et al., 2016 ; Meyer et al., 2017 ). For some individuals, these effects persist long after the disaster has passed ( Bonanno et al., 2010 ).

Early, descriptive data examining mental health concomitants of COVID-19 also support this prediction. In an early 2020 sample of 1,200+ Wuhan-area nurses and physicians, relatively high prevalence estimates (i.e., 12% 15%, and 36%) of moderate-to-severe levels of anxiety, depression, and general distress, respectively, were reported ( Lai et al., 2020 ). The pandemic is also already affecting national mental health in countries that were hit early; for example, there have been sharp rises in anxiety and depression in China ( Gao et al., 2020 ). A similar pattern is likely to occur following COVID-19 more globally, especially among vulnerable populations, with the severity and duration of mental health difficulties being proportionally greater as a function of the severity and duration of the stressors. In this context, there are several areas of psychopathology that are most likely to result from COVID-19. Five of these areas are addressed in the sections that follow, although there is insufficient space to do full justice to them all.

Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety and depressive symptoms are likely to increase during the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in greater vulnerability to psychological distress in the population at large and more individuals with diagnosable psychiatric disorders. This supposition is supported by data from the 2008 U.S. financial crisis, which suggested that chronic stress acutely increases risk for internalizing disorders (specifically, depressive, anxiety, and panic symptoms; Forbes & Krueger, 2019 ). This possibility is also supported by contemporary models that articulate how stress affects psychological and biological systems associated with anxiety and depression (e.g., Slavich, 2020 ). For instance, extant research reveals that psychological stressors increase emotional reactivity and reliance on maladaptive emotionregulation strategies that are known to exacerbate risk for internalizing symptoms (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008 ; Segerstrom, Tsao, Alden, & Craske, 2000 ). COVID-19 related stressors, such as social-distancing mandates, may also reduce access to regular social interactions that are recognized as an important process for promoting psychosocial resilience and overall well-being ( Cohen, 2004 ; Hofmann, 2014 ; Slavich, 2020 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to precipitate substantial increases in depression. Depression is generally theorized as an abnormal response to loss, and the pandemic is likely to engender loss experiences in several life domains. Most notably, COVID-19 will lead to the death of loved ones for many individuals, with such deaths being relatively sudden and otherwise unexpected. In addition, the pandemic is leading to losses in social connectedness, daily routines, social roles, jobs, and financial stability. COVID-19 also directly affects other risk factors for depression, such as emotion regulation and coping ( Gross & Jazaieri, 2014 ) and may interfere with many protective forms of responding, such as seeking of social support and use of problem-focused coping strategies (e.g., thinking of various ways to solve a problem, selecting one, and taking action; Compas et al., 2017 ; Hofmann, Sawyer, Fang, & Asnaani, 2012 ). At the same time, social isolation and ongoing media coverage focusing on social-environmental threat may result in increased rumination and worry that drive biological processes such as inflammation that increase risk for depression ( Slavich & Irwin, 2014 ). Social isolation and stay-at-home orders also may interfere with the ability to experience positive affect, apply social strategies for regulating affect, and use rewarding experiences to offset negative emotions. Given the importance of social connection and belonging for regulating positive affect for resilience to depression and resilience in general, COVID-19 may be particularly likely to increase risk for depression.

Although anxiety and depression overlap both temporally and in terms of phenotypic presentation, anxiety is generally considered a primary response to threat or uncertainty, whereas depression is typically conceptualized as an abnormal response to loss. Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic is a complex, multifaceted stressor that includes elements of threat, uncertainty, and potential loss. It is well known that not all individuals who experience major life stress develop affective disorders, with cognitive and emotional responses playing a critical role in determining whether anxiety or depression follows such stress ( Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010 ). Therefore, it will be important to pay attention to exaggerated perceptions of threat (which have been linked to anxiety) and loss (which have been linked to depression). It will also be important to ensure that the behaviors required to ensure physical safety, such as avoidance (e.g., of other people and public spaces) and vigilance (e.g., scanning the body for signs of disease), do not have the unintended consequence of increasing risk for the onset, exacerbation, or relapse of these two disorders.

Traumatic Stress Reactions

Acute stress disorder (ASD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are trauma- and stressor-related disorders that may occur at any age, and may result from direct exposure to a traumatic event involving actual or perceived life-threat, as well as from repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of a traumatic event ( American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). ASD symptoms are shorter in duration (3 days to 1 month) than for PTSD (at least 1 month) but, for both, symptoms include intrusion (e.g., nightmares), negative mood or cognitions, avoidance, and arousal (e.g., hypervigilance, insomnia).

Traumatic stress symptoms are likely to increase as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic because the multiple stressors that characterize it, including the threat to personal safety and security, significant life disruption, loss of loved ones and of financial resources, and disruption and erosion of interpersonal support systems, have been implicated in the development or maintenance of ASD and PTSD symptoms (e.g., Bonanno et al., 2010 ). In fact, the disaster mental health and medical-trauma literatures are pertinent to understanding the mental health impacts of COVID-19, which has exposed many individuals to medically related traumatic events associated with symptoms of ASD and PTSD, such as the sudden death of a loved one, near-death experiences, and life-threatening medical procedures (e.g., Hatch et al., 2018 ). Increased symptoms of traumatic stress (e.g., arousal, negative intrusive thoughts) are likely to occur in the general population, potentially fueled by media exposure to traumatic aspects of COVID-19 ( Gao et al., 2020 ). Although such symptoms may reflect a normative response to an unusually stressful situation, such symptoms are of substantial mental health concern when they are severe, persistent, and interfere with functioning.

Vulnerable populations in high-impact disasters, such as first responders and health care providers ( Bonanno et al., 2010 ; Norris et al., 2002 ), as well as other essential workers, are likely to be at risk for developing subclinical or clinical levels of ASD or PTSD in the COVID-19 pandemic. Health care providers and first responders may be exposed to extreme stressors, often referred to as secondary traumatic stress ( Greinacher, Derezza-Greeven, Herzog, & Nikendei, 2019 ), such as the sudden death of patients and moral decision-making regarding for whom to provide lifesaving intervention ( Griffin et al., 2019 ). First responders and essential workers also provide direct services to individuals with COVID-19 or have increased exposure to the general public, thereby increasing their own COVID-19 risk. Further, these vulnerable groups are advised to self-isolate away from family ( Ellis, 2020 ), thereby restricting social support, and further increasing their risk of traumatic stress reactions (e.g., Kaniasty & Norris, 2008 ; La Greca, Silverman, Lai, & Jaccard, 2010 ). Family members of first responders also may be at elevated risk for traumatic stress reactions, as they fear for loved ones’ safety (e.g., Duarte et al., 2006 ). Furthermore, elevated rates of PTSD have been observed among women and children and among disadvantaged minority groups in the aftermath of disasters ( Bonanno et al., 2010 ; Norris et al., 2002 ), and are likely to emerge for the current pandemic. PTSD symptoms also confer risk for alcohol and substance use, relationship difficulties, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (e.g., Sareen, 2014 ). Elevated symptoms of PTSD also commonly co-occur with symptoms of depression, which bodes poorly for recovery (e.g., Lai, La Greca, Auslander, & Short, 2013 ), and complicates treatment (e.g., Cohen & the Workgroup on Quality Issues, 2010 ; La Greca & Danzi, 2019 ).

Overall, the “good news” is that most youth and adults exposed to traumatic events recover over time, although a significant minority (15% to 30%) continue to display elevated symptoms of PTSD a year or more postdisaster ( Alisic et al., 2014 ; Bonanno et al., 2010 ) and will benefit from psychological interventions ( APA, 2017 ; Cohen & the Workgroup on Quality Issues, 2010 ; La Greca & Danzi, 2019 ). Psychological first aid ( Brymer et al., 2006 ), widely used for short-term crisis and disaster intervention, may be important for use with people displaying traumatic stress symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Increasing access to psychological treatments, such as via telehealth procedures, will be critical to address the anticipated widespread need for COVID-19-related mental health services for youth and adults.

Substance Use Disorders

Individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs), particularly those who smoke, vape, or use opioids, may be at increased risk for COVID-19 illness severity and even death ( Smith et al., 2020 ; Vardavas & Nikitara, 2020 ; Volkow, 2020 ). For some, pandemic-related stressors (e.g., job loss and financial strain), anxiety, and boredom due to extended stays at home could lead to an increase in smoking or other substance use as a way to cope with negative moods ( Nagelhout et al., 2017 ). In this regard, in March 2020, during the initial stay-at-home weeks in the United States, a survey of adults identified an association between more frequent alcohol and cannabis use in the past week and significantly higher mental distress ( Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Mental Health Measurement Working Group, 2020 ).

For individuals in recovery from SUD or seeking addiction treatment, the pandemic has presented unique challenges. Mandated stay-at-home orders have increased social isolation and concomitant risk for relapse for some individuals ( Volkow, 2020 ). Specifically, staying-at-home can involve domestic stressors (e.g., intimate partner violence), which can challenge recovery efforts. These stressors, in turn, can lead to or exacerbate co-occurring mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety among individuals with SUD ( Tripp, Jones, Back, & Norman, 2019 ). In addition, marginalized individuals, who are homeless or imprisoned, have high rates of SUD (e.g., up to 50% of prisoners have an SUD; Fazel, Yoon, & Hayes, 2017 ), and increased risk for COVID-19 infection ( Volkow, 2020 ) are less likely to receive care during the pandemic due to service provision cut-backs ( Alexander, Stoller, Haffajee, & Saloner, 2020 ). In-person social support, which can provide daily structure for individuals with SUD, especially during early recovery, has shifted to virtual or telehealth platforms ( Volkow, 2020 ). Federal guidelines have rapidly expanded to support access to and more flexible delivery of evidence-based eHealth ( APA, 2020 ), as well as to provide needed medications to support abstinence (e.g., medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder; Alexander et al., 2020 ) and other e-recovery support groups facilitated by psychologists in response to the pandemic ( Khatri & Perrone, 2020 ). Through evidence-based eHealth interventions, psychologists are using this opportunity in a time of crisis to create structured, safe, social, virtual spaces to facilitate recovery mindfully among individuals with SUD, and to reduce stigma and harms related to substance use disorder.

Before the onset of COVID-19, suicide already was a relatively neglected public health problem ( U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, and National Action Alliance for Suicide, 2012 ). The current pandemic increases the risk for suicide in at least four ways that require a far greater investment in suicide science, along with new approaches to suicide screenings and imminent risk assessments across all types of clinical care. The risk is perhaps most obviously increased in psychologically vulnerable populations through introduction of a novel, pervasive, relatively uncontrollable stressor. Those with histories of depressive symptoms, selfinjury, prior suicidality, maltreatment, PTSD, substance use, and disruptive behavior disorders (particularly among youth) are especially at risk for increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors for all the stress-related reasons already discussed ( Nock & Kessler, 2006 ). In particular, maladaptive interpersonal patterns experienced with few opportunities to escape or distract (due to stay-at-home orders) may elevate individuals’ risk for suicide, and may intensify stressful experiences over time. Second, new at-risk populations may emerge from COVID-19, including trauma-exposed first responders, health care workers, particularly physicians ( Gold, Sen, & Schwenk, 2013 ) who have had to make unspeakably difficult medical-care decisions under high-pressure conditions, as well as other essential workers. Children who have experienced increased exposure to other kinds of trauma (e.g., child maltreatment; Gawęda et al., 2020 ) also may be at increased risk for suicidal behavior.

Third, it should be noted that suicide rates are associated closely with economic indices, with periods of recession associated with higher rates of suicide ideation, attempts, and deaths by suicide among all age and all racial/ethnic groups (e.g., Reeves et al., 2012 ). The worldwide economic changes associated with COVID-19 are likely to be associated with changes in a wide range of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Last, most theories offered to explain suicidal behavior have implicated interpersonal stress (e.g., conflict, loss) as a common factor that significantly enhances individuals’ risk ( Miller & Prinstein, 2019 ). Reports of increased isolation, loneliness, interpersonal loss, and limited interpersonal contact thus present a uniquely high-risk period for suicide within the general population as well, requiring ongoing monitoring in the years that follow COVID-19. Unfortunately, many of the existing resources designed to address imminent suicide risk may prove less effective during or after the COVID-19 crisis. Perhaps most importantly, there may be greater reluctance to call 911 or visit a local emergency room to ensure safety from suicidal urges during the pandemic for fear of infection or out of concern that one’s suicidality may overburden hospital staff who are needed to attend to COVID-19 patients.