Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Inflation targeting: A time-frequency causal investigation

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Economics, National University of Sciences and Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft

- Tanweer Ul Islam,

- Dajeeha Ahmed

- Published: December 11, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295453

- Reader Comments

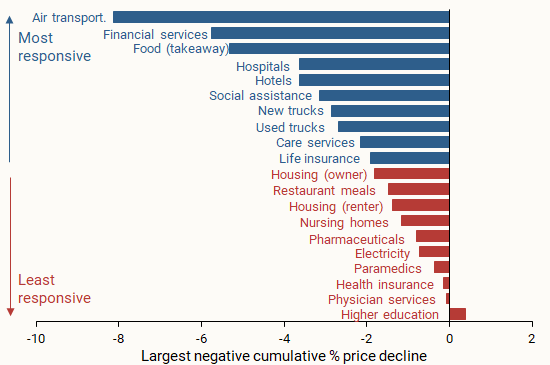

The enduring discourse regarding the effectiveness of interest rate policy in mitigating inflation within developing economies is characterized by the interplay of structural and supply-side determinants. Moreover, extant academic literature fails to resolve the direction of causality between inflation and interest rates. Nevertheless, the prevalent adoption of interest rate-based monetary policies in numerous developing economies raises a fundamental inquiry: What motivates central banks in these nations to consistently espouse this strategy? To address this inquiry, our study leverages wavelet transformation to dissect interest rate and inflation data across a spectrum of frequency scales. This innovative methodology paves the way for a meticulous exploration of the intricate causal interplay between these pivotal macroeconomic variables for twenty-two developing economies using monthly data from 1992 to 2022. Traditional literature on causality tends to focus on short- and long-run timescales, yet our study posits that numerous uncharted time and frequency scales exist between these extremes. These intermediate scales may wield substantial influence over the causal relationship and its direction. Our research thus extends the boundaries of existing causality literature and presents fresh insights into the complexities of monetary policy in developing economies. Traditional wisdom suggests that central banks should raise interest rates to combat inflation. However, our study uncovers a contrasting reality in developing economies. It demonstrates a positive causal link between the policy rate and inflation, where an increase in the central bank’s interest rates leads to an upsurge in price levels. Paradoxically, in response to escalating prices, the central bank continues to heighten the policy rate, thereby perpetuating this cyclical pattern. Given this observed positive causal relationship in developing economies, central banks must explore structural and supply-side factors to break this cycle and regain control over inflation.

Citation: Islam TU, Ahmed D (2023) Inflation targeting: A time-frequency causal investigation. PLoS ONE 18(12): e0295453. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295453

Editor: Kittisak Jermsittiparsert, University of City Island, CYPRUS

Received: September 5, 2023; Accepted: November 22, 2023; Published: December 11, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Islam, Ahmed. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data relevant to this paper are available from GitHub at https://github.com/Tanweerulislam/Data-Inf-PR/blob/main/Inf-PR%20data.xlsx .

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

There is a long-standing debate among economists about the effectiveness of interest rates as a monetary policy tool for managing inflation in developing economies [ 1 ]. While some argue for its universal effectiveness, others suggest it may be less potent in developing economies [ 2 ]. Proponents of universal effectiveness cite its successful application in numerous developed economies to combat inflation [ 2 , 3 ]. They posit that the basic principles of economics are universally applicable, indicating that interest rate policy should perform as effectively in developing economies as it does in their more advanced counterparts.

Those economists who contend that interest rate policy is less effective in developing economies emphasize several factors that can impede its implementation and effectiveness in these countries [ 2 , 4 ]. For example, the prevalence of sizable informal sectors in developing economies, which often operate with distinct financial regulations compared to the formal sector. This circumstance can pose a challenge for central banks in effectively transmitting monetary policy signals to the entire economy [ 5 ]. The relatively weaker financial systems in developing economies can also impede the effective implementation of monetary policy [ 2 ]. Moreover, developing economies often grapple with substantial external debt, exposing them to fluctuations in global financial markets. This susceptibility can create difficulties for central banks as they endeavor to oversee and stabilize domestic inflation rates [ 6 , 7 ]. Furthermore, in developing economies, reduced central bank credibility leads expectations to be anchored in historical data, thereby increasing their reliance on past information. Consequently, this can lead to higher inflation by diminishing the efficacy of inflation targets as the primary influencers of inflation expectations [ 8 ].

Supply shocks can trigger substantial and enduring fluctuations in headline inflation. This can add complexity to the trade-off between economic output and inflation [ 9 ], posing challenges for monetary authorities and rendering monetary policy less effective in developing economies. In a high inflation scenario, understanding the implications of interest rates becomes a complex task. Assessing the true level of the real interest rate is particularly challenging when inflation expectations are in constant flux [ 10 ]. Further, in the presence of supply shocks, applying monetary tightening has a marked and positive influence on inflation in both advanced and emerging economies [ 11 ]. Rodrik and Velasco [ 12 ] argue that the sensitivity of investment and consumption to interest rates in developing economies can be low, limiting the effectiveness of interest rate policies in controlling inflation.

Developing economies face challenges in achieving consistent economic growth and have increasingly focused on using interest rates to control inflation, aiming for price stability in monetary policy. However, the relationship between inflation and interest rates remains unclear, with studies reporting varying causality directions. Some studies find unidirectional causality from interest rates to inflation [ 13 , 14 ], and inflation to interest rate [ 15 – 17 ], while others identify bidirectional relationships [ 18 , 19 ].

The debate about the effectiveness of interest rate policy to control inflation in developing economies is likely to endure. The evidence indicates that the effectiveness of such policies can vary due to structural and supply-side factors. Additionally, the literature does not provide a clear consensus on the causal relationship between inflation and interest rates. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that interest rate policies remain a prominent strategy in many developing economies. This leads to the question: Why do central banks in these economies continue to favor interest rate-based monetary policy? To address this, our study utilizes wavelet transformation to dissect interest rate and inflation data across different frequency scales. One of the key advantages of wavelets lies in their ability to unveil concealed cyclic trends, patterns, and non-stationarity prevalent in economic time series data that may not be apparent with traditional time series analysis [ 20 ]. This innovative approach provides an opportunity for a meticulous exploration of the intricate causal interplay between these two pivotal macroeconomic variables. Conventional literature on causality often confines itself to the delineation of short- and long-run timescales. In contrast, our study advances the argument that numerous unexplored time and frequency scales exist between these two extremes [ 21 ], potentially exerting a profound impact on the causal relationship and its directional flow. It expands the horizons of the existing literature on causality and opens new avenues for understanding the nuances of monetary policy in developing economies.

2. Literature review

2.1. theoretical framework.

The theoretical framework of using interest rates as a monetary policy tool to control inflation is primarily rooted in the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) and the Phillips Curve. The Quantity Theory of Money posits that a change in the rate of money supply growth leads to a corresponding change in the rate of growth in nominal income and in inflation [ 22 ]. Raising interest rates results in higher borrowing costs, prompting consumers and businesses to typically cut back on their spending and borrowing. This decrease in spending leads to a reduction in the demand for money which theoretically leads to lower inflation.

The Phillips Curve delineates an inverse correlation between inflation and unemployment [ 23 ], thereby signifying a trade-off for central banks. When central banks opt to increase interest rates, their objective is to mitigate inflation within an overheated economy. However, such a decision may entail a temporary elevation in unemployment levels. Conversely, the reduction of interest rates can catalyse economic activity but concurrently has the potential to exacerbate inflation. Consequently, central banks employ interest rates as a mechanism to attain equilibrium between inflation and employment.

2.2. Empirical debate

Monetary policy stands as a pivotal instrument for fostering economic growth in developing nations. The discourse surrounding this subject is long-lasting, with a multitude of studies elucidating its influence and efficacy. It holds the potential to achieve price stability, stimulate investments, and bolster economic vitality. Yet, the effectiveness of monetary policy in these contexts remains intricate and subject to debate. In this literature review, we amalgamate insights from pertinent research to illuminate the intricate connection between monetary policy and inflation in developing countries.

Inflation targeting is a monetary policy framework wherein the central bank defines a precise inflation target and deploys its policy tools to achieve this goal. Literature has demonstrated the efficacy of inflation targeting in reducing inflation rates and stimulating economic growth in developed countries. Notably, Masson et al. [ 2 ] observed that developing economies implementing inflation targeting experienced lower inflation compared to countries without such a policy framework. Nonetheless, arriving at a definitive conclusion is not as straightforward when considering developing economies [ 4 ] as the preconditions for adopting such a framework are not yet present in these economies [ 2 ]. In these contexts, the implementation and effectiveness of interest rate-based monetary policy can be hindered by structural and supply-side factors.

Alberola & Urrutia [ 5 ] argue that monetary policy actions are sacrificed due to the presence of an informal sector in developing economies. Their results indicate that informality can dampen inflation volatility in response to various shocks but, at the same time, diminish the efficacy of monetary policy. The monetary policy impact takes a longer time in relatively weaker financial systems in developing economies [ 24 ] as compared to developed financial systems. Further, when people have less trust in the central bank, they are more likely to base their expectations about future inflation on past inflation rates. Inflation targets by the central banks become less effective in impacting future inflation expectations [ 8 ].

According to Coletti et. al. [ 9 ], supply shocks can cause large and long-lasting fluctuations in inflation, which can make it difficult for central banks to manage inflation and economic output. This is especially true in developing economies, where monetary policy may be less effective. Further, in the presence of supply shocks, applying monetary tightening has a marked and positive influence on inflation in both advanced and emerging economies [ 11 ]. Under high inflation, it can be difficult to understand the effects of interest rates as the real interest rates can change quickly when inflation expectations are unstable [ 10 ]. Thus, the effectiveness of interest rate policies in controlling inflation may be limited in developing economies, because investment and consumption may be less sensitive to interest rates [ 12 ].

Thus, developing economies have been struggling to achieve steady economic growth [ 25 ]. Controlling inflation with the help of interest rates has become the only goal of many Central Banks during the previous few decades [ 26 ] because inflation targeting is a complete monetary framework that ensures price stability along with other monetary objectives [ 27 – 29 ]. However, inflationary pressures can lead to contractionary monetary policy that impacts economic growth, poverty, and inequality [ 30 – 33 ]. Thus, the direction of causality between inflation and interest rate is the prime concern because it is related to the potency of the monetary policy framework.

2.3. Causality debate

The literature does not provide any clarity on the direction of causality between the interest rate and inflation. Mehregan et al., [ 13 ] examine the causal relationship between inflation and interest rate by utilizing panel data from 24 developing countries. A unidirectional relationship from interest rate to inflation is established for 23 countries. Ahmadi et al.[ 14 ] rely on Hsiao’s causality test to establish the causal relationship from interest rate to inflation only for Qatar and Djibouti using quarterly data for sixteen Middle East-North Africa (MENA) countries for the period 1997–2008. No causality is found for the rest of the member countries. The Toda-Yamamoto causality test shows a unidirectional causal relationship from interest rate to inflation for the United Kingdom and Switzerland while for Germany the causality runs two-way [ 18 ]. Another study conducted on Turkey using monthly data shows a unidirectional causal relationship from inflation to interest rate between 2005(04)-2006(05) and from interest rate to inflation for 2015–2016 [ 34 ]. Asgharpur et al., [ 35 ] employ a panel causality approach to 40 Islamic countries to explore the causal nexus between interest rate and inflation. The study establishes the unidirectional relationship from interest rate to inflation. Mirza & Rashidi [ 36 ] consider two scenarios for assessing the causal relationship between the variables: lending rate & inflation and real interest rate and inflation. The study utilizes panel data ranging from 2006 to 2013 for South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries and finds no causal relationship for the first scenario and a bidirectional causal relationship for the second scenario.

Fatima & Sahibzada [ 19 ] determine the nature of the relationship between inflation, interest rate, and money supply for the economy of Pakistan from 1980–2010. The Granger causality analysis indicates the existence of a bidirectional relationship between inflation and interest rate which corroborates with the findings in [ 33 ]. Nezhad & Zarea [ 37 ] examine the causality relationship between inflation and interest rate in Iran. Toda and Yamamoto’s Granger causality analysis shows one-way causality from the interest rate to the inflation rate. Amaefula [ 38 ] finds strong evidence of unidirectional Granger causality from interest rate to inflation rate for Nigeria using monthly data from 1995 to 2014 whereas Alimi & Ofonyelu [ 17 ] employs Toda-Yamamoto test to establish a unidirectional relationship from inflation to nominal interest rate for Nigeria using data for the period 1970–2011 which is in line with the findings for Kenya [ 39 ], Jorden [ 40 ], Pakistan [ 15 ], and Bangladesh [ 16 ].

Based on the synopsis of previous studies above, there is a lack of consensus among researchers concerning the efficacy of interest rate policies in managing inflation within developing economies due to the structural and supply-side factors. Furthermore, the direction of causality between interest rates and inflation in developing nations remains a subject of debate. The sample size, econometric methods, frequency, and time scales could be the possible reasons behind the conflicting causality results. Literature covers the first two reasons, sample size and econometric methods well [ 41 – 44 ] however, the frequency and time scale impact has not been considered. Literature on causality considers only the short- and long-run as time scales while this study argues that there exist more time and frequency scales in between the short- and long-run that may impact the causal relationship and its direction. Therefore, we employ the wavelet transformation to decompose the interest rate and inflation series into different frequency scales. This will help us to study the causal dynamics between the two important macroeconomic variables in detail.

3. Data & methodology

This study utilizes international financial statistics (IFS) and central banks’ repositories to collect the data on Consumer Price Index (CPI) based inflation and Policy Rate (PR) of twenty-two developing countries for varying periods (see Table 2 , Col 1, 2). This study aims to investigate the causal relationship between inflation and interest rates through a time-frequency analysis, necessitating the use of high-frequency data. The selection of the countries in our sample is contingent on the accessibility of monthly data concerning these macroeconomic variables. Time series analysis of macroeconomic indicators is generally grounded in the time domain and ignores the frequency domain. Spectrum analysis allows us to decompose the series into a spectrum of cycles of varying length that helps to extract the main oscillatory components of the series [ 45 , 46 ] including low frequency (trend), medium frequency (cycles), and high frequency (noise) components. There are different tools available to transform the time series into these components including the Fourier and Wavelet transformations. The Fourier transformation requires the stationarity of the data [ 47 ] whereas the macroeconomic variables are less likely to be integrated of order zero (i.e., stationary). To explore the scale-dependent causal linkages between inflation and policy rate, we employ Wavelet transformation to decompose the series into various frequency scales. Wavelet transformation has an edge over the Fourier transformation as its window size adjusts optimally both for low and high frequencies [ 46 ]. Further, its good frequency and time resolutions enable it to capture movements both at low and high frequencies which allows it to cater for outliers, regime changes, and shocks [ 48 ]. For wavelet decomposition, we need to select a suitable filter like Haar and Daubechies. The Haar filter is simple but neither continuous nor differentiable however the Daubechies is an orthogonal, smooth, symmetric, and localized filter [ 48 ]. Therefore, this study uses the Daubechies’s Daub4 wavelet filter while decomposing the series.

After decomposing the inflation and policy rate series for all the selected countries, we estimate correlation coefficients for inflation and policy rate at different scales to understand the direction and strength of the relationship between the variables. The t-test is used to establish the statistical significance of the correlation coefficients. To explore the direction of causality, we employ the Granger Causality test to the pair of variables at various scales. The direction of the relationship and causality together would help us answer the question of whether the policy rate is an appropriate tool for controlling inflation.

3.1. Wavelet decomposition

This study employs Daubechies’s wavelet to decompose inflation and policy rate and considers the length of the business cycle to sixty-four months [ 46 ]. The series is decomposed into different frequency components of length between (2 k , 2 k +1 ) months where k = 1,2,3,…,5 keeping in view the monthly frequency of our data [ 49 , 50 ]. Both series are decomposed into five orthogonal frequency components, trends, and business cycles ( Table 1 ). To better understand the decomposition, following Hanif et al., [ 48 ] & Tiwari et al., [ 51 ], the components are categorized as noise (D1), cycles (D2-D5), business cycle, and trend (Col 3, Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295453.t001

These frequency scales depict varying cyclical fluctuations which are usually ignored while conducting the conventional causal analysis. The implication of ignoring these cyclic fluctuations is that we could not study the relationship between the variables at different scales that exist between the short- and long-run. Fig 1 indicates the phenomenon: cyclical fluctuations recede as the aggregation increases over the months.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295453.g001

4. Results & discussion

Table 2 below provides descriptive statistics on the inflation and policy rates of the selected twenty-two developing countries. Theoretically speaking, the higher the interest rate, the lower the inflation rate like in the case of Congo, the average policy rate is at 19.18 and the average inflation rate is at 2.80. Whereas the mean inflation and policy rates for other countries like Morocco, Ghana, Nigeria, Uzbekistan, etc. do not follow the inverse relationship as per the theory. On balance, Fig 2 shows a positive relationship between the two rates i.e., the higher the policy rate, the higher the inflation. These initial findings raise a valid question on the appropriateness of the policy rate as a monetary tool and the disagreement among the researchers regarding the direction of causality motivates us to explore the more time and frequency scales that exist between the short- and long-run.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295453.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295453.t002

This study utilizes correlation and causality analysis to test the appropriateness of the policy rate as a monetary tool. Theoretically, we should expect a negative and significant correlation between the policy rate and inflation with the direction of causality running from policy rate to inflation. Correlation and causality results are furnished in Tables 3 and 4 respectively.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295453.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295453.t004

In Table 3 , we observed a negative and significant correlation between the policy rate and inflation, at levels, for four countries including Algeria, Morocco, Mongolia, and Sri Lanka which is in line with the theory. However, interestingly, no causal relationship is observed for these countries [ 14 ] except for Sri Lanka ( Table 4 ). Policy rate causes inflation in Sri Lanka with a negative and significant relationship [ 13 ] which contradicts the finding in [ 36 ] of bidirectional causality for the SAARC countries. At levels, no causality in case of India and the bidirectional causality in the case of Pakistan [ 19 ] might lead [ 36 ] to conclude the bidirectional causality for the panel of SAARC countries. Positive and significant correlation is observed for the remaining eighteen countries with mixed results on the direction of causality ( Table 3 ) which is not in line with the theory. Unidirectional causality runs from policy rate to inflation for Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and South Africa whereas causality runs from inflation to policy rate for Cambodia and Zambia. Two-way relationship is established for Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria.

Considering the noise series (D1), a negative and significant correlation is recorded for five countries at level whereas lagged policy rate has a significant and positive association with inflation ( Table 3 ). Three out of these five countries (Pakistan, Congo, Mauritania) show no causal relationship at level for the noise series and the remaining two countries (Uganda & Zambia) show a two-way causal relationship ( Table 4 ). The direction of causality runs from lagged policy rate to inflation in the case of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Uzbekistan with a positive correlation whereas inflation causes the lagged policy rate in the case of Cambodia and Ghana.

For D2 (4–8 months) component at level, negative and significant correlation is observed for only Congo and Mauritania where inflation causes the policy rate. For the remaining countries, positive and significant correlation contradicts the theory while the causality runs from policy rate to inflation for five countries, from inflation to policy rate for five countries, and a bidirectional relationship is established for nine countries. The lagged policy rate causes inflation only in the case of India but with a positive and significant correlation meaning that a positive shock to the policy rate would lead to higher inflation in the future. On balance, the findings for the D2 component reject the policy rate as an appropriate monetary tool.

For D3 (8–16 months), no causality is observed for Algeria, Morocco, Mongolia, Nepal, and Mauritania [ 14 ]. Congo is the only country that has a significant and negative correlation with bidirectional causality. Thirteen other countries are showing bidirectional causality but with positive and significant correlation which is not in line with our hypothesis: there is a negative relationship between the policy rate and inflation. Policy rate causes inflation in Nigeria [ 38 ] with the positive direction of the relationship between the variables.

While considering D4 (16–32 months), a lagged policy rate causes inflation in the case of Pakistan and Bangladesh with a positive and significant correlation between the variables of interest. On balance, the remaining countries exhibit a two-way causality while the negative and significant correlation is only observed for Algeria and Mauritania. It is pertinent to mention that no causal relationship is observed for Mauritania. No causality may be attributed to the existence of a parallel financial market in Mauritania [ 52 ].

For D5 (32–64 months), results indicate a bidirectional causal relationship between the policy rate and inflation for all the selected developing countries however negative correlation is found only for Algeria and Morocco. Positive and significant correlation for the rest of the economies is not in line with our theoretical hypothesis.

For the business cycle (4–64 months) series, policy rate causes inflation in the case of India, Kyrgyzstan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Egypt, and Uganda however the correlation is positive and significant between the variables of interest. This means an increase in interest rate would further add fuel to inflation. While Congo, Cambodia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Zambia are experiencing a reverse causality i.e., inflation is causing the policy rate with a significant positive correlation except for Congo meaning that an increase in inflation would push the interest rate in the upward direction. These results corroborate the findings in the literature for countries like Nigeria and Kenya [ 17 , 39 ].

Considering the trend (> 64 months), a negative and significant relationship is established only for Algeria, Morocco, Mongolia, and Sri Lanka while the rest of the countries show a positive and significant correlation between the policy rate and inflation. The direction of causality is unanimously bidirectional for all the selected developing countries.

To sum up, Algeria, Morocco, and Mauritania are the countries bearing a negative and significant relationship between the policy rate and inflation for most of the frequency scales. However, these countries exhibit either no causality or bidirectional causality for most of the scenarios. Further, Mauritania experiences reverse causality (from inflation to policy rate) for the D2 component. For the rest of the countries, the correct combination of correlation sign and direction of causality is not found. Hence, we reject the hypothesis that increasing the policy rate would control the inflation in developing countries under consideration.

5. Conclusion

This study examines the suitability of policy rates as instruments for managing inflation in 22 developing countries using wavelet decomposition. Theoretically, the policy rate and inflation are negatively correlated i.e., the inflation rate would decline in response to an increase in policy rate and the direction of causality runs from policy rate to inflation. The investigation reveals several noteworthy findings at different time scales.

At levels , on average, a positive relationship exists between policy rate and inflation across the countries studied ( Fig 2 ). The direction of causality is found to be both uni- and bi-directional with positive and significant correlations between these variables. The only exception is the Sri Lanka where the policy rate does Granger cause inflation with negative correlation which is in line with the theory.

The short run analysis is based on the two components of the series namely D1(2–4 months) and D2 (4–8 months). First component analysis reveals that the policy rate and inflation are negatively and significantly correlated with bidirectional causality for Uganda and Zambia only. Unidirectional causality runs from policy rate to inflation in the case of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Uzbekistan with a positive and statistically significant correlation. In the context of second component the policy rate causes inflation in case of India, Philippines, and Mongolia with positive and statistically significant correlation. This suggests that an increase in the policy rate could potentially lead to a rise in inflation within these countries. While the causality direction remains ambiguous for the remaining countries in the study, it is important to note that there is a positive correlation between the policy rate and inflation.

The medium short run analysis utilizes the D3 (8–16 months), D4 (16–32 months), and D5 (32–64 months) components of the policy rate and inflation. For the first component (D3), Congo is the only country having a significant and negative correlation with bidirectional causality. Thirteen other countries are showing bidirectional causality but with positive and significant correlation. While considering the D4 & D5 components, on balance, a two-way causality with a positive correlation is found. In the long run (> 64 months), the direction of causality is unanimously bidirectional for all the selected developing countries with a positive and significant correlation between the policy rate and inflation.

Theory suggests that a negative causal relationship between the policy rate and inflation is instrumental for central banks to implement tight monetary policy as a measure to effectively control inflation. However, this exercise reveals that the developing economies bear a positive causal relationship between the policy rate and inflation. This indicates that as the central bank raises interest rates, it triggers an increase in price levels. Furthermore, in response to rising prices, the central bank continues to raise the policy rate, perpetuating this cycle. Given the observed positive causal relationship between the policy rate and inflation in developing economies, central banks should explore structural and supply-side elements to disrupt this cycle and successfully manage inflation.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 39. MMASI B., “An Investigation of the Relationship Between Interest Rate and Inflation in Kenya,” University of Nairobi, 2013.

Inflation expectations and consumer spending: the role of household balance sheets

- Open access

- Published: 09 March 2022

- Volume 63 , pages 2479–2512, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lenard Lieb ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2814-2022 1 &

- Johannes Schuffels 1

10k Accesses

9 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Research interest in the reaction of consumption to expected inflation has increased in recent years due to efforts by central banks to kick-start demand by steering inflation expectations. We contribute to this literature by analysing whether various components of households’ balance sheets determine how consumption reacts to expected inflation. Two channels in particular are conceivable: an increase in inflation expectations can raise consumption through direct increases in expected real wealth, e.g. for households with nominal financial liabilities. By affecting the real interest rate, expected inflation can interact with wealth if only those households can adapt their consumption to current real interest rates that are not budget-constrained or sufficiently liquid to shift funds between consumption and savings. We investigate these channels empirically using household-level information on balance sheets, durable consumption and inflation expectations from the Dutch Central Bank’s Household Survey. We find that investments in risky assets as well as net worth moderates the relation between expected inflation and durable spending decisions. The net worth effect is most pronounced for households with fixed interest rate mortgages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Inflation and growth: the role of institutions

Hakan Yilmazkuday

Effects of risk tolerance, financial literacy, and financial status on retirement planning

Heejung Park & William Martin

Real GDP growth rates and healthcare spending – comparison between the G7 and the EM7 countries

Mihajlo Jakovljevic, Yuriy Timofeyev, … Vladimir Reshetnikov

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Hypotheses on why inflation expectations can have an impact on consumption on the micro-level are based on two arguments. First, inflation expectations change the real interest rate and could therefore affect consumption through intertemporal substitution. Second, they affect expected real wealth and therefore consumption out of real wealth. In both cases the composition of a household’s balance sheet can alter the size and direction of the effect of inflation expectations on spending. Attempts to gauge this interaction in the literature have been incomplete. Several authors estimated the impact of inflation expectations on consumption. These studies have often exploited some sort of natural experiment such as the zero lower bound or value-added tax increases to identify a causal relationship using cross-sectional (Bachmann et al. 2015 ; Ichiue and Nishiguchi 2015 ; D’Acunto et al. 2016 ) or panel data (Burke and Ozdagli 2013 ; Crump et al. 2015 ; Duca et al. 2018 ) without reaching consensus on the sign or size of the effect. However, no analysis has properly accounted for the potential role of the balance sheet as a moderator of the effect of price expectations on spending. In this paper we investigate empirically whether different components of a household’s balance sheet interact with its inflation expectations in affecting realised consumer spending. To this end, we use panel data on household level balance sheets, inflation expectations and durable consumer spending from the Dutch Central Bank’s (DNB) Household Survey.

While the use of micro-level data to study the nexus between inflation expectations and consumer spending has allowed researchers to estimate cross-sectional effects, almost no attention has been paid to analyse the economic mechanisms behind these “general” effects. Changes in the real interest rate affect a household’s optimal allocation of consumption over time. Differences in inflation expectations can lead to differences in the perceived real interest rate both over time and across households. Depending on their balance sheets, households might or might not be able to shift funds from savings to current spending or vice versa. Additionally, access to and costs of credit financed consumption might differ between households depending on the available collateral. We characterise these two channels through which inflation expectations can affect spending as real interest rate dependent. Another channel that motivates the research question of this paper is a real wealth channel. Inflation expectations determine expected real wealth. In case of rising inflation expectations debtors expect increases in real wealth, while creditors expect falls in real wealth. The net nominal position of their balance sheet measures their exposure to price level changes. Empirical evidence suggests that consumption is sensitive to changes in wealth (Case et al. 2005 ; Mian et al. 2013 ). Consequently, inflation expectations and balance sheet positions might interact on the micro-level. This could have macroeconomic effects if debtors have a higher propensity to consume than creditors. Here we refer to the growing heterogeneous agent literature that emphasises the relevance of differential marginal propensities to consume of households with differing balance sheet compositions (Cloyne et al. 2020 ; Auclert 2019 ). Another reason is the inflation-hedging nature of certain assets: owners of real estate and stocks are relatively well protected against devaluation effects of inflation (Fama and Schwert 1977 ; Kim and In 2005 ) whereas financial liabilities are repaid in nominal terms. Accordingly, spending of net debtors is expected to be more sensitive to changes in expected inflation than for net owners of real estate and stocks. Footnote 1

Our approach departs from the literature in important ways. First, we try to identify specific economic channels that determine the effect of inflation expectations on spending. The granular information on households’ balance sheet in our data set allows us to test explicitly what role balance sheets play in moderating the effect of price expectations on durable spending. Second, we analyse realised spending, rather than planned spending or attitudes towards spending. These two latter measures, often used in the literature, will likely overestimate a positive effect of inflation expectations on spending since households might be willing to consume but liquidity constraints impede them from doing so. Third, observing households over time allows us to better capture the intertemporal dimension of consumption decisions, which is particularly important if agents are forward looking and expectations play a crucial role.

Sufficient and accurate control for confounders in analyses of large scale surveys poses problems. The DNB Household Survey contains a wide range of household characteristics. Including all characteristics that could potentially impact consumption behaviour is not feasible. Selecting controls only based on personal judgement or theory might lead to omission or unnecessary inclusion of some variables. Instead we apply a data-driven post-double variable selection procedure of the type introduced by Belloni et al. ( 2014a ). With penalised regression techniques, we only select those variables that impact the dependent variable and the independent variables of interest in the data. This limits the danger of omitted variable bias while ensuring a parsimonious specification. Moreover, the panel dimension of our data allows us to control for time-invariant confounders in general.

The results of our paper give support to channels we classified as real interest rate and real wealth dependent. Financial investments moderate the effect of inflation expectations on spending which can be explained by the real interest rate channel. We also find that the positive relation between expected inflation and the probability of positive durable expenditures is amplified for households with lower net worth. The effect is stronger among a subsample of households with fixed interest mortgages. We interpret this result as evidence for the real wealth channel which depends on the net nominal position of the balance sheet combined with heterogeneities arising from the composition of the balance sheet.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. In Sect. 2 we review the related literature. We discuss possible economic mechanisms that link consumption decisions, inflation expectations and the balance sheet in Sect. 3 . The data are presented in Sect. 4 . In Sect. 5 we present our econometric framework. Results are discussed in Sect. 6 . Section 7 concludes.

2 Related literature

A number of influential contributions by Coibion and Gorodnichenko ( 2012 , 2015a ) and Coibion et al. ( 2017 ) have initiated a renewed discussion about the formation of inflation expectations and their macro- and microeconomic effects. They provide substantial evidence that inflation expectations by consumers, businesses and even professionals and central bankers do not satisfy the conditions for full information rational expectations. Thus, consumers make systematic forecasting errors that, according to Coibion and Gorodnichenko ( 2015b ), can help explain macro-puzzles, such as the missing disinflation in the US after 2009. In this paper we complement their work by investigating the channels through which consumers’ inflation expectations affect microeconomic choices.

More closely related to our research question are previous studies that have used micro-data to estimate the effects of inflation expectations on consumer spending. As stated above, no clear consensus has been reached on the direction or size of the effect. Bachmann et al. ( 2015 ) use repeated cross sections of the Michigan Survey of Consumers to investigate the effect of inflation expectations of households on their “readiness to spend”. The authors relate readiness to spend to a survey question on whether the current period is a good time to spend money on durable goods. They find that during the zero lower bound episode higher inflation expectations had slightly negative effects on the probability for households to have positive spending attitudes arguing that high inflation expectations might be correlated with increased economic uncertainty. The authors perform a number of regressions in search of heterogeneities in the relationship between inflation expectations and spending attitudes, for instance by including binary measures of home ownership and proxying an individual’s debtor status with age. They do not specifically analyse wealth channels that moderate the spending response to inflation expectations. Ichiue and Nishiguchi ( 2015 ) approach the problem similarly, but with Japanese data and find strong positive effects of inflation expectations on planned spending. They argue that, after a long period of zero nominal interest rates, Japanese consumers have understood how inflation affects the real interest rate and therefore react. The authors do not further investigate the role of balance sheets. In contrast to both of these studies, we construct a measure of realised spending and allow for a moderating role of balance sheet variables in the relation between expected inflation and spending.

A very different approach has been taken by D’Acunto et al. ( 2016 ). Their paper uses a value-added tax increase in January 2007 in Germany to estimate the effects of exogenous changes in inflation expectations. Compared to households in other European countries that did not experience the VAT increase, German households were substantially more likely to have positive attitudes towards spending in the months before the tax increase came into force. A limitation of this approach is that the price expectations of German households in November and December of 2006 contained considerably less uncertainty than those of households in other European countries. Households knew that a VAT increase will unambiguously increase prices of consumer products. They usually cannot form expectations with such certainty and precision. The effect of inflation expectations on consumption might differ substantially in times with less salient events or policy changes that nonetheless impact inflation.

The study most similar to ours is Burke and Ozdagli ( 2013 ). Using survey responses on expected inflation and realised spending on a wide range of products of a panel of American households between 2009 and 2012, they find much less clear results than the studies presented above. Households do not seem to increase their durable expenditures as a result of higher inflation expectations. In addition, they find evidence for effects on non-durable expenditures, driven by owners of real estate. Even though we analyse durable expenditures, this finding justifies our strategy of carefully investigating potential interactions of expected inflation with balance sheet variables. Burke and Ozdagli ( 2013 ) can only observe binary measures of balance sheet variables, such as home ownership. Crump et al. ( 2015 ) estimate the subjective elasticity of intertemporal substitution based on survey responses on expected inflation and planned consumer spending of a panel of American households in the Survey of Consumer Expectations. They find that the elasticity of planned consumption to changes in expected inflation is around 0.5. While planned spending is a better proxy for spending than “readiness to spend”, it isn’t a realised measure neither. Based on a large panel of Eurozone households, Duca et al. ( 2018 ) find small positive effects of increased inflation expectations on households’ “readiness to spend”. While they control for household wealth, they do not examine the balance sheet channels we suggest.

3 Mechanisms

Next we discuss different mechanisms through which balance sheets could affect households’ spending responses to changes in expected inflation. Potential candidates are real interest rate and real wealth changes that result from changed inflation expectations. In addition to balance sheet size and its net position, we also discuss how differences in its composition could moderate the spending response of inflation expectations.

3.1 Intertemporal Substitution

Consumers adapt their spending behaviour when relative prices change by substituting the more expensive for the cheaper good. Price changes over time also change the purchasing power of consumers’ income in different periods which may affect their selected intertemporal consumption bundle. These standard substitution and income effects of relative price changes can be illustrated by the following basic set-up. Consider the following intertemporal budget constraint for a household with nominal income \(y_t\) , nominal interest rate i and consumption good \(c_t\) with price \(p_t\) in periods 1 and 2:

By normalising \(p_1\) to 1 and defining \(\pi ^e = \frac{p_2 - p_1}{p_1}\) , we can rewrite the previous equation as

An increase in \(\pi ^ { e }\) raises the expected future price of the consumption good relative to its current price and lowers the real interest rate. This triggers the standard substitution effect: consumers want to increase current spending relative to future spending since the price of the good is lower in the current period. In contrast, the direction of the income effect depends on whether the consumer is borrower or saver. The lower real interest rate benefits the borrower: by transferring income from period 2 to period 1, one can increase total consumption compared to a situation with higher real interest rates. Savers lose: the income they transfer from period 1 to period 2 earns less real interest, therefore total consumption falls. Even this very basic set-up predicts differential consumption responses for households based on their balance sheet position: debtors will increase their current consumption by more than savers if their expectations about future prices rise. The qualitative conclusion does not change if future income is indexed to inflation, only the degree to which consumption is transferred to the current period would be lower.

However, not all households face the same perceived borrowing conditions. Analogous to the argument made by Bernanke ( 1993 ) for firms, households with higher net worth are generally seen as more credit-worthy by banks and might face better borrowing conditions. Thus, even under constant economy-wide nominal interest levels the perceived borrowing conditions for households do not only depend on their inflation expectations. The same change in inflation expectations can lead to different household-specific perceived borrowing conditions if the balance sheet quality differs. Applying this idea to the relationship between inflation expectations and consumption is not new: Ichiue and Nishiguchi ( 2015 ) make the same point in their analysis, but cannot convincingly test it.

3.2 Real Wealth

An increase in expected inflation leads to a reduction in expected real wealth since the expected price level of the future period is now higher than before while nominal wealth has remained constant. For debtors the opposite is true: higher inflation will reduce the expected real value of debt and thus increase their expected net worth. The observation that changes in wealth have effects on consumption has been widely documented in the past using both macro- and micro-data (Case et al. 2005 ; Mian et al. 2013 ). The most appropriate measure for the exposure of a household’s financial position to changes in the price level is its nominal net worth, i.e. assets minus liabilities.

3.3 Balance Sheet Composition

However, this view on the real wealth channel may be too simplistic. There are various reasons why differences in the composition of the balance sheet could lead to different consumption reactions of households with the same nominal net worth. First, there are differences in the sensitivity of various assets and liabilities to inflation. Real estate or financial investments can serve as a protection against inflation. Fama and Schwert ( 1977 ) have shown that returns on real estate protect fully against unanticipated as well as anticipated inflation. They regressed the expected nominal return of several assets on expected inflation. If the coefficient of expected inflation is equal to one, the nominal return compensates for losses in real returns on average. Thus, the expected real return does not change when inflation expectations change. More recent studies have confirmed the long-run inflation hedging nature of real estate and found mixed evidence for the short-run analysis conducted by Fama and Schwert ( 1977 ) (Anari and Kolari 2002 ; Hoesli et al. 2008 ). While Fama and Schwert ( 1977 ) cannot confirm the inflation hedging nature of stocks in the short term, later studies came to the conclusion that in the long-run stock investments have the same inflation hedging property as real estate (Schotman and Schweitzer 2000 ; Kim and In 2005 ). Households with a substantial part of their wealth invested in these asset classes might not regard higher future inflation as a threat to their future wealth since their investment strategy is designed to protect against such developments. Even if this protection is not perfect, it is superior to, say, for cash holdings. Households with cash holdings as their only assets have no way of protecting themselves against real losses due to inflation. Similarly, debt contracts usually specify a nominal amount that has to be repaid. Here, higher inflation expectations lead to an expected decrease in the real value of debt, i.e. increasing real wealth. To summarise, households who invested large parts of their wealth into real estate or financial investments are expected to exhibit less sensitivity to inflation expectations in their consumption decisions. Households with relatively large exposure to cash or debt may react more strongly since their expected real wealth necessarily changes in response to changing inflation expectations.

Composition effects could play a role on the liability side as well. While most liabilities are repaid in nominal terms, differences across liabilities arise with respect to the interest payment schemes. Specifics of mortgage contracts play an important role in the transmission of nominal interest rates to household behaviour, especially consumption: Di Maggio et al. ( 2017 ) show that holders of adjustable rate mortgages respond significantly stronger to nominal interest rate shocks than those with fixed rate mortgages and without mortgages. These results have been confirmed in different settings. Cloyne et al. ( 2020 ) show that household balance sheet composition in the US and the UK alters the spending response to changes in the nominal interest rate, suggesting differing marginal propensities to consume between home owners with mortgages (high) and outright owners (low). Cumming and Hubert ( 2019 ) show a positive relation between the share of financially constrained (adjustable rate) mortgage holders and aggregate consumption responses to monetary policy shocks. While in the US and the UK interest on mortgages is predominantly paid at adjustable rates, interest in the Netherlands is predominantly paid at rates fixed for more than one year (83% of the total volume (DNB 2020 )). We argue that households with these kind of mortgages are an interesting subsample to study the spending response to changes in inflation expectations on. The argument builds on a similar intuition as that applied by the authors cited above. Without nominal rigidities, changes in inflation expectations should not have real effects. The insensitivity of interest payments on fixed rate mortgages to nominal rates potentially increases the impact of changes in inflation expectations on real expected disposable income. Footnote 2 If the marginal propensity to consume for more constrained households is indeed higher, those fixed rate mortgage holders with lower net worth should exhibit a stronger response to changes in their inflation expectations. We test this hypothesis in Sect. 6.3 .

Any of the above channels imply that individuals with a different balance sheet composition (both concerning the relative sizes of assets and liabilities and the relative importance of specific classes of assets and liabilities), but identical changes in inflation expectations could exhibit differing spending responses. These considerations give rise to an econometric specification in which we allow for interactions between households’ expected inflation and its different balance sheet components. Section 5 outlines how we aim to test the different mechanisms and what effects they would imply for our empirical analysis. By accounting for this interaction we depart from the previous literature on the topic. All of the aforementioned authors have stressed in their papers that wealth might play a role in the relationship between expected inflation and (durable) consumption. Our key contribution consists of testing this channel in a novel way.

Our aim in this study is to explore the interaction between households’ inflation expectations and their balance sheets in determining spending decisions. Information on all variables needs to be at the household level and available for the same household over several years.

Contrary to previous studies, we set out to analyse realised consumer spending instead of attitudes to spending in general. However, specific survey answers on total (durable) expenditures might involve substantial measurement error. It is much easier to recall expenditures for specific durable goods since these items are seldom purchased and each individual purchase accounts for a substantial fraction of total spending of that period.

Additionally, our analysis requires balance sheet information on the household level. The literature on wealth effects on consumption concludes that different types of assets and liabilities might have different effects on consumer expenditures (Case et al. 2005 ). To provide a thorough account of the interaction we want to analyse individual balance sheet components as well as the net financial position of the households.

For the reasons mentioned above we make use of the DNB Household Survey (DHS) administered by CentERdata (Tilburg University, The Netherlands) and issued by the Dutch Central Bank (DNB). It includes households’ self-reported balance sheets and their expected one year ahead inflation rate. Part of the self-reported balance sheet consists of vehicles owned by the household. We use this information to construct a variable of household vehicle expenditures (more details below). The DHS is an unbalanced panel of 12.439 households with annual observations between 1993 and 2018. More than one household member can respond to the survey. Since the balance sheets are aggregated at the household level, we primarily use responses to household member specific questions from the first member of the household. If the first member has not answered a specific question we use the response of the second member. This results in 52.055 household-year observations from which we construct our variables of interest. The survey is typically completed by respondents between the 15th and 26th calendar week of a year with some exceptions in case respondents need to be reminded of completion.

We want to stress the unique fit of this data set for our purposes. To our knowledge, no previous study has made use of such extensive balance sheet information to analyse the effect of inflation expectations on realised consumer spending.

In the following, we give an overview of the different variables of interest and provide descriptive statistics.

4.1 Measuring durable consumption

In recent papers many authors concentrate on analysing the effects of inflation expectations on durable consumption (Burke and Ozdagli 2013 ; Bachmann et al. 2015 ; Ichiue and Nishiguchi 2015 ). We follow the literature in this respect. Durable consumption is the component of aggregate consumption most likely to be affected by variations in the real interest rate since it is more likely to be credit financed than expenditures on non-durable goods. Additionally, demand for non-durable consumption is less elastic to changes in macroeconomic conditions in general.

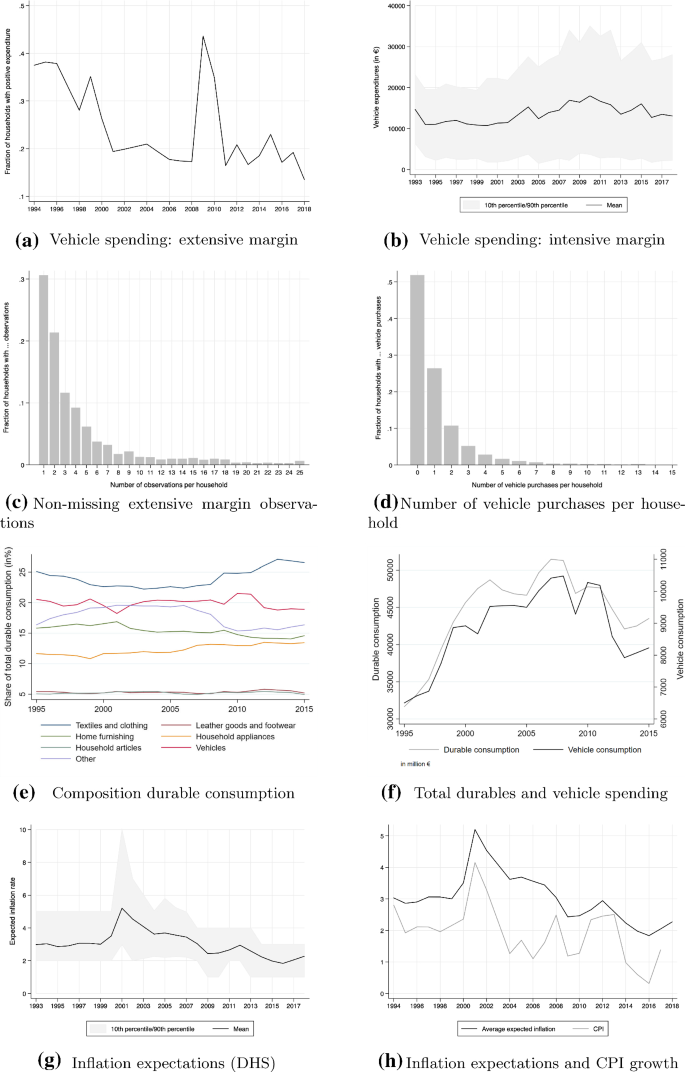

The DNB Household Survey does not include questions on expenditures on different classes of durable goods. However, households do report a large part of their assets. Among those are vehicles, such as cars, motorbikes and boats. For each of these items households report the purchasing price and additional details on the vehicle, such as its build year. We construct our expenditure variable by recording each time the purchasing price changes. If the purchasing price stays constant but the build year changes, a purchase is recorded as well. For the extensive margin, the consumption variable takes the value 0 in case we record no change in the vehicle and 1 in case there is a change. Footnote 3 The fraction of households that have purchased a vehicle in a specific year is shown in Fig. 1 a. Footnote 4 For those households that did buy a car we construct a variable capturing the intensive margin of the purchase, i.e. the amount a household spent on vehicles, i.e. the sum of changed purchasing prices. Figure 1 b shows the mean, the 10th and 90th percentile of this variable’s distribution over the sample period.

It is unclear whether we should expect the effects outlined above to materialise on the extensive or the intensive margin of a purchase. In theory, the mechanisms could play a role in both decisions a household has to make. When emphasising the extensive margin, we assume that households’ tastes regarding durable goods are relatively fixed over time and the element of the decision that is subject to variations in expected inflation is the timing of the purchase. In a year in which a household has higher inflation expectations it might be more likely to buy the durable item it had already planned to acquire for longer. This reasoning is consistent with some results that emerged from the literature analysing the “hot potato” effect of inflation. The “hot potato” effect refers to the observation that consumers spend their money faster in times of high inflation. In a search based monetary theory model, Liu et al. ( 2011 ) find that inflation affects especially the extensive margin of the purchasing decision.

On the extensive margin, we observe 12,620 vehicle purchases throughout the entire sample period. In 39,435 household-year observations, no purchase has taken place. Figure 1 c shows from how many household observations we can draw to construct the extensive margin variable. For roughly 30% of households we only observe the purchasing decision once. This means that these households participated in two consecutive waves of the survey, allowing us to evaluate whether the purchasing price of their vehicles changed. Figure 1 d depicts the fraction of households with a certain number of vehicle purchases. For a majority of households we do not observe any purchase. Roughly 45% of households we observe between one and five purchases.

However, the sample that enters our regression analysis shrinks considerably since not all households answer all survey questions. Due to limited overlap with the variables capturing expected inflation, the remaining balance sheet variables, current and expected income, we are left with 8663 observations from 3092 households. We use the full sample when applying a linear probability model. The application of the conditional logit model reduces our sample size further as it drops households for which the extensive margin variable does not change value, leaving us with 4790 observations from 909 households.

On the intensive margin we would be limited to a much lower number of observations. In our preferred specification we would have to rely on a sample of 2645 observations from 1396 households. In a fixed-effects framework an average number of 1.89 observations per panel unit would not allow us to draw any meaningful conclusions. Therefore, we do not proceed with analysing the intensive margin further.

How much can vehicle expenditures tell us about durable consumption? To answer this question, we take a look at the aggregate durable and vehicle expenditures in the Netherlands. Figure 1 e shows all subcategories of total durable consumption as defined by CBS, the Dutch statistical agency. Vehicle expenditures account for about 20% of total durable consumption in the Netherlands across the whole sample period. They are the second biggest component of durable consumption after textiles and clothing. Additionally, as Fig. 1 f shows, they are highly correlated with total durable expenditures (correlation coefficient of 0.95 between 1995 and 2015). We indeed find that, on the aggregate level, vehicle purchases in the Netherlands instrument overall durable consumption very well, as indicated in Fig. 1 f and as suggested by an effective (marginal) F-statistic of 183. Furthermore, vehicle purchases have frequently been used in the literature to gauge the dynamic behaviour of aggregate durable spending (see e.g. Mian et al. 2013 ; Berger and Vavra 2015 ; Ravn et al. 2020 ).

Descriptives

4.2 Inflation expectations

In the DHS households are asked the following question about their expectations for one year ahead inflation:

What is the most likely (consumer)prices increase over the next twelve months, do you think?

Since 2008 the possible answers are given between 1 and 10% in steps of one. Before, respondents were free to respond with any number they liked. To ensure consistency between the responses given before and after 2008, we enforce the same limitation in the answer range before 2008. Figure 1 g shows the development of this variable over time. There is a clear peak after the introduction of the Euro. After that the downward trend in average expectations continues until well after 2008 and has stabilised close to but above 2% after that.

Figure 1 h compares average expected inflation in the Netherlands with the realised CPI values. Expected inflation is structurally higher than realised inflation but trends are well anticipated by households. The latter observation is more relevant for our study since we are mainly interested in changes in inflation expectations. Secondly, this alleviates concerns that inflation expectations by (laymen) survey respondents are completely detached from actual inflation and instead measure expectations or perceptions of some other variables.

4.3 Balance sheet

Table 1 shows the individual balance sheet components that households report as well as the aggregation level at which we include them in our models (in bold). Grouping of assets is largely determined by the liquidity of the balance sheet item. Among illiquid assets we differentiate between real estate and other assets to acknowledge the special role housing wealth could play. We group liabilities according to maturity. Mortgages and other longer term debt (referred to as loans) are aggregated separately. The net worth variable is constructed by subtracting liabilities from assets.

Instead of having to interpret our results in units of currency, we prefer to analyse percentage changes. The usual log-transformation is not well suited for our variables since many households do not possess some of the balance sheet variables. Their observations would be lost in case of a log-transformation. In the case of the net worth variable all negative net worth observations would be dropped as well. Instead, we perform an inverse hyperbolic sine transformation (ihs). Footnote 5 Table 2 gives descriptive statistics for all balance sheet variables that enter our regressions in the empirical analysis.

5 Empirical approach

As pointed out in Sect. 3 , there are several arguments why inflation expectations could matter for spending decisions and how wealth could alter size and direction of this relation. In this section we motivate our econometric approach in light of the transmission channels we aim to investigate. To that end, we run fixed effects linear probability models (LPM) as well as conditional logit (CL) regressions with the binary purchasing variable as dependent variable.

5.1 Specification

Our analysis consists of two baseline specifications. We estimate a fixed effects linear probability model as well as a conditional logit. Below we outline these two specifications. For the linear probability model we run the following regression:

where \(\alpha _ { i }\) and \(\kappa _ { t }\) are household and year-fixed effects, \(E _ { it-1 }\left( \pi _ { t } \right) \) is household \(i's\) expectation at time \(t-1\) for the inflation rate at time t , \(W _ { it - 1 }\) is the value of a particular balance sheet variable in \(t-1\) , and \({\varvec{X}} _ { it-1 }\) is household i ’s set of other characteristics at time \(t-1\) .

In addition, we estimate the following conditional logit model:

where \(\lambda \) denotes the logistic function. The fixed effects logit model imposes the condition that \(T>\sum _{t=1}^{T} c _ {it} > 0\) , where T is the total number of periods that the household participated in the survey. This condition implies that only households whose expenditure variable takes on both possible values (0 and 1) are included in the estimation. We construct inference based on bootstrapped standard errors.

Next we discuss how to interpret the models in ( 1 ) and ( 2 ) in light of the mechanisms outlined in Sect. 3 . Two coefficients in the above regressions are of special interest: \(\sigma \) , the coefficient for expected inflation, and \(\delta \) , the coefficient of the interaction term. \(\delta \) measures in which direction and with what magnitude a specific balance sheet component scales the effect of inflation expectations on consumption. Conversely, when including a single balance sheet components, \(\sigma \) measures the effect of expected inflation on consumption if the household has no holdings of the balance sheet component. For instance, when including net worth as the balance sheet variable, \(\sigma \) measures the relation between inflation expenditures and spending if net worth would be zero. As we argued in Sect. 3 , the real interest rate channel would suggest a positive effect of the interaction between expected inflation and household wealth, implying negative effects for any interaction between liabilities and expected inflation. In contrast, the real wealth channel would suggest a negative interaction effect between household wealth and expected inflation. However, many assets serve as hedges against inflation. The real wealth channel on its own would thus predict no significant interaction effect when financial investments or real estate holdings are interacted separately with expected inflation. Any interaction between liabilities and expected inflation is thus expected to have positive effects on the spending variable. The mechanisms that we discussed in Sect. 3 suggest opposite effects of the interaction between wealth and expected inflation. The coefficient of the interaction term is the average magnitude of the real interest and the real wealth channel. That is, if \(\sigma \) is significantly different from zero, one of the two effects dominates. However, this would not necessarily prove the absence of the other effect.

Table 3 gives an overview of the coefficients we would expect for the variables of interest in our regression if the channels could be measured separately. Thus, if the coefficients in our models align with the signs or magnitudes of these coefficients we could claim that the respective channel dominates over the other.

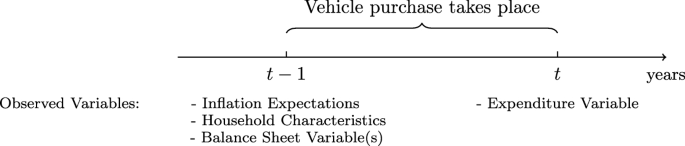

5.1.1 Timing of households’ consumption decision

We only include households that are observed in at least two waves of the survey; otherwise, we cannot determine differences (or lack thereof) in their vehicles’ purchasing prices. Since we construct the expenditure variable by comparing purchasing prices of vehicles and do not use specific questions on the subject, we do not observe the exact date of the purchase. In our regressions we relate the vehicle purchase that occurred between period \(t-1\) and t to the balance sheet, inflation expectations and other characteristics observed in period \(t-1\) . Since households are asked about their expectations for the coming 12 months, we consider these 12 months as the current period in which the effect on spending should play out. Figure 2 shows which period’s observation of each of the previously introduced variables is used in our analysis.

Timing of the purchasing decision

5.1.2 Selection of controls

Consumers’ purchasing decisions are driven by many factors. We attempt to isolate the role of inflation expectations and various balance sheet items. However, if we do not control for other key predictors, estimation of the coefficients of interest may be biased. While it is plausible to assume that current and expected income are relevant covariates in this context, the survey provides us with detailed information on individual household characteristics (e.g. attitudes toward saving and risk-taking, financial literacy, health, financial situation and expectations, etc.) and, hence, contain other possibly relevant predictors.

In order to identify relevant covariates, we use the “post-double-selection” method proposed by Belloni et al. ( 2014b ). This involves a two-step LASSO regression, which in a first step selects covariates that predict the dependent variable, and in a second step selects variables predicting our independent variables of interest. The second step is necessary to control for the omitted variable bias. Note that selected controls may differ across regressions as we perform the “post-double-selection” for each regression separately. We always include current and expected income. Since we include individual fixed effects in all (LASSO) regressions we expect that most time-invariant household characteristics are controlled for, and only few (if any) additional controls are needed to estimate the impact of inflation expectations on car purchases. Footnote 6

For the exposition of the results of our analysis, we proceed in steps. First, we present the results from our baseline analysis in which we are mainly interested in the interaction terms between expected inflation and various balance sheet variables. We present estimates from fixed effects LPM and Logit regressions. In Table 4 results from the Logit regressions are marked as CL in the column title. Lastly, we analyse a subsample of households that have fixed interest rate mortgages.

As we argued in Sect. 3 , the different balance sheet components are not expected to moderate the effect of inflation expectations on spending in the same fashion. The main reason are differences in their inflation-hedging potential. Certain assets like stocks or real estate protect the investor better against inflation than cash, for example. Additionally, we expect a difference between assets and liabilities in general. Debt is usually repaid in nominal terms, which makes its expected real value sensitive to expectations about inflation.

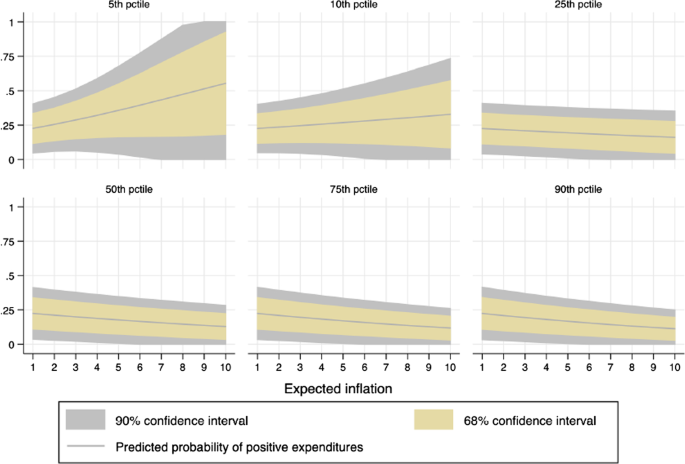

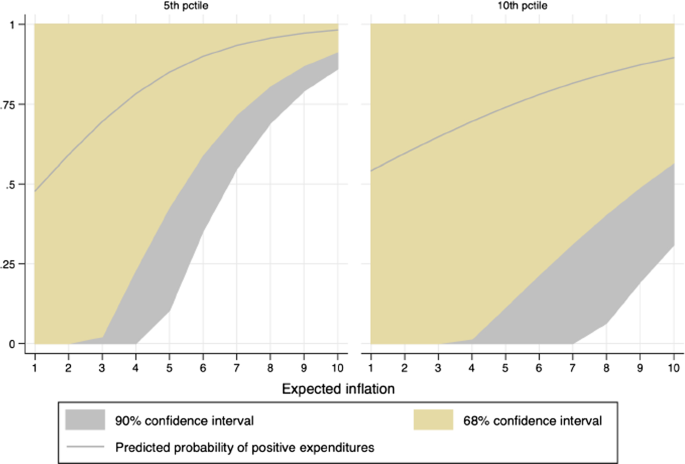

6.1 Balance sheet components

Table 4 presents the baseline results. For the regressions results shown in columns one and two, we included all single balance sheet components and their interactions with expected inflation. Collinearity is not an issue since net worth is not included and therefore free to move. The results do not depend much on the specification used, both the linear probability model (LPM) and the conditional logit (CL) give similar results in terms of sign and magnitude of the estimator. All but one balance sheet component do not significantly alter the relationship between inflation expectations and the probability to purchase a vehicle. For the interaction term between financial investments and expected inflation both the LPM and CL estimates are positive, the LPM estimate marginally above the 10% significance threshold, the CL estimate marginally below. The relation between expected inflation and the spending decision seems to be marginally different for households with within-household deviations from their average financial investment holdings compared to those at their average value. Households with higher than average financial investments exhibit a stronger positive reaction of expected inflation on their probability to spend. To quantify this relation, consider a household with inflation expectations 2%-points Footnote 7 above their mean: a 10% increase in financial investments increases their predicted purchasing probability by around 3.8%-points. Compare that to a household that is 5%-points above their mean expected inflation: here, a 10% increase in financial investments increases the predicted purchasing probability by almost 10%-points.

Column 2 of Table 4 shows the results of the analogous conditional logit regression to the OLS regression in column 1. The results look qualitatively similar. The only balance sheet item that significantly alters the effect of inflation expectations on spending probabilities are financial investments. The estimated coefficient of 0.0226 corresponds to an odds ratio of roughly 1,023. An odds ratio larger than one means that as the value of the interaction term increases, the odds of having positive vehicle expenditures in a given year rise. Footnote 8

This result is in line with the real interest channel presented in Sect. 3 . A falling perceived real interest rate increases incentives to substitute future spending for current spending. Only households with either sufficient collateral or sufficient internal finance are able to act on their increased willingness to spend. However, as the predicted probability plot shows, this moderating effect does not seem to be large enough to affect the outcome in an economically meaningful way.

Plot of the predicted probability of positive vehicle expenditures for households for given percentiles of the net worth distribution (based on estimates of column (5), Table 4 )

6.2 Net worth

We continue our analysis by taking a different perspective on the role that individual balance sheet components play. The rationale for analysing components individually is that they differ in terms of their return or real value sensitivity to inflation. At the same time, no component on its own is an appropriate measure of household wealth. Therefore, we now analyse whether net household wealth modifies the relation between expected inflation and the probability to spend. Columns 3 and 4 of Table 4 provide the baseline results of this analysis. We apply the same strategy as above by interacting the expected inflation rate of each household with their net worth to explain the following period’s spending decision. The net worth variable is transformed from levels using the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation that accommodates zero and negative values while mimicking a log-linearisation (see Sect. 4 ).

In none of the three specifications in which we include net worth (columns 3, 4 and 5 in Table 4 , we find strong evidence in favour of a moderating effect of net worth on spending. However, all point estimates are negative and of similar magnitude. This means that for households with a net worth that is below their household specific mean, the predicted probability to spend increases.