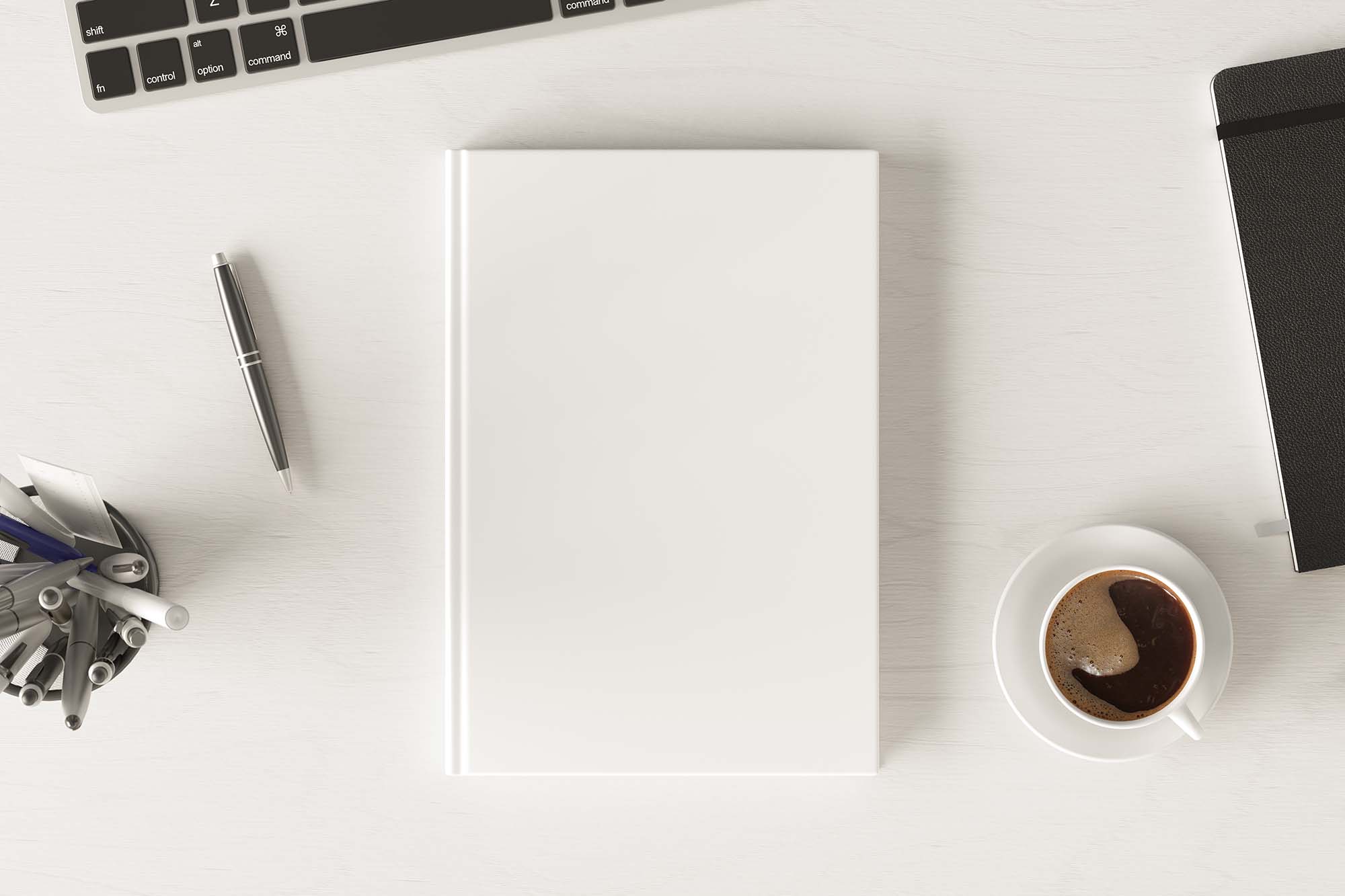

Psychological Research

An International Journal of Perception, Attention, Memory, and Action

- Focuses on human perception, attention, memory, and action.

- Upholds impartiality, independent of any particular approach or school of thought.

- Includes theoretical and historical papers alongside applied research if they contibute to basic understanding of cognition

- Adheres to firm experimental ground in its publications.

- Bernhard Hommel

Latest issue

Volume 88, Issue 3

Latest articles

Children’s metacognition and cognitive offloading in an immediate memory task.

- Catriona Iley

- Srdan Medimorec

Arousal, interindividual differences and temporal binding a psychophysiological study

- Anna Render

- Hedwig Eisenbarth

- Petra Jansen

Context-specific adaptation for head fakes in basketball: a study on player-specific fake-frequency schedules

- Iris Güldenpenning

- Nils T. Böer

- Matthias Weigelt

Can an isolated middle-series item make a “Dent” in the bow-shaped serial-position curve of comparative judgments?

- Kaelyn G. Calma

Beyond fixed sets: boundary conditions for obtaining SNARC-like effects with continuous semantic magnitudes

- Craig Leth-Steensen

- Seyed Mohammad Mahdi Moshirian Farahi

- Noora Al-Juboori

Journal updates

Psychological research is seeking a new editor-in-chief for 2025.

Psychological Research is seeking nominations for a new, incoming Editor-in-Chief, term beginning January 1 2025.

Interested candidates should email their CV and a letter of interest, indicating their expertise, editorial experience, and a vision statement (2 pages or so) for the journal to [email protected]

The call will be open until May 1st, 2024, and candidates will be contacted shortly after.

Psychological Research celebrates 100 years in Publication!

Special Issue on 100 years Psychologische Forschung/ Psychological Research edited by Bernhard Hommel (pp 2305 - 2365) and Special Issue on Concrete constraints on abstract concepts edited by Anna M. Borghi, Samuel Shaki and Martin H. Fischer (pp 2366 - 2560)

Journal information

- ABS Academic Journal Quality Guide

- Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) Journal Quality List

- Biological Abstracts

- Current Contents/Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Google Scholar

- Japanese Science and Technology Agency (JST)

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- Social Science Citation Index

- TD Net Discovery Service

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Editorial policies

© Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Psychological Science

Prospective submitters of manuscripts are encouraged to read Editor-in-Chief Simine Vazire’s editorial , as well as the editorial by Tom Hardwicke, Senior Editor for Statistics, Transparency, & Rigor, and Simine Vazire.

Psychological Science , the flagship journal of the Association for Psychological Science, is the leading peer-reviewed journal publishing empirical research spanning the entire spectrum of the science of psychology. The journal publishes high quality research articles of general interest and on important topics spanning the entire spectrum of the science of psychology. Replication studies are welcome and evaluated on the same criteria as novel studies. Articles are published in OnlineFirst before they are assigned to an issue. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) .

Quick Facts

Read the February 2022 editorial by former Editor-in-Chief Patricia Bauer, “Psychological Science Stepping Up a Level.”

Read the January 2020 editorial by former Editor Patricia Bauer on her vision for the future of Psychological Science .

Read the December 2015 editorial on replication by former Editor Steve Lindsay, as well as his April 2017 editorial on sharing data and materials during the review process.

Watch Geoff Cumming’s video workshop on the new statistics.

Current Issue

Online First Articles

List of Issues

Editorial Board

Submission Guidelines

Editorial Policies

Featured research from psychological science, teens who view their homes as more chaotic than their siblings have poorer mental health in adulthood.

Many parents ponder why one of their children seems more emotionally troubled than the others. A new study in the United Kingdom reveals a possible basis for those differences.

Rewatching Videos of People Shifts How We Judge Them, Study Indicates

Rewatching recorded behavior, whether on a Tik-Tok video or police body-camera footage, makes even the most spontaneous actions seem more rehearsed or deliberate, new research shows.

Loneliness Bookends Adulthood, Study Shows

Loneliness in adulthood follows a U-shaped pattern: It’s higher in younger and older adulthood, and lowest during middle adulthood, according to new research that examined nine longitudinal studies from around the world.

Privacy Overview

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Methods Section for a Psychology Paper

Tips and Examples of an APA Methods Section

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Verywell / Brianna Gilmartin

The methods section of an APA format psychology paper provides the methods and procedures used in a research study or experiment . This part of an APA paper is critical because it allows other researchers to see exactly how you conducted your research.

Method refers to the procedure that was used in a research study. It included a precise description of how the experiments were performed and why particular procedures were selected. While the APA technically refers to this section as the 'method section,' it is also often known as a 'methods section.'

The methods section ensures the experiment's reproducibility and the assessment of alternative methods that might produce different results. It also allows researchers to replicate the experiment and judge the study's validity.

This article discusses how to write a methods section for a psychology paper, including important elements to include and tips that can help.

What to Include in a Method Section

So what exactly do you need to include when writing your method section? You should provide detailed information on the following:

- Research design

- Participants

- Participant behavior

The method section should provide enough information to allow other researchers to replicate your experiment or study.

Components of a Method Section

The method section should utilize subheadings to divide up different subsections. These subsections typically include participants, materials, design, and procedure.

Participants

In this part of the method section, you should describe the participants in your experiment, including who they were (and any unique features that set them apart from the general population), how many there were, and how they were selected. If you utilized random selection to choose your participants, it should be noted here.

For example: "We randomly selected 100 children from elementary schools near the University of Arizona."

At the very minimum, this part of your method section must convey:

- Basic demographic characteristics of your participants (such as sex, age, ethnicity, or religion)

- The population from which your participants were drawn

- Any restrictions on your pool of participants

- How many participants were assigned to each condition and how they were assigned to each group (i.e., randomly assignment , another selection method, etc.)

- Why participants took part in your research (i.e., the study was advertised at a college or hospital, they received some type of incentive, etc.)

Information about participants helps other researchers understand how your study was performed, how generalizable the result might be, and allows other researchers to replicate the experiment with other populations to see if they might obtain the same results.

In this part of the method section, you should describe the materials, measures, equipment, or stimuli used in the experiment. This may include:

- Testing instruments

- Technical equipment

- Any psychological assessments that were used

- Any special equipment that was used

For example: "Two stories from Sullivan et al.'s (1994) second-order false belief attribution tasks were used to assess children's understanding of second-order beliefs."

For standard equipment such as computers, televisions, and videos, you can simply name the device and not provide further explanation.

Specialized equipment should be given greater detail, especially if it is complex or created for a niche purpose. In some instances, such as if you created a special material or apparatus for your study, you might need to include an illustration of the item in the appendix of your paper.

In this part of your method section, describe the type of design used in the experiment. Specify the variables as well as the levels of these variables. Identify:

- The independent variables

- Dependent variables

- Control variables

- Any extraneous variables that might influence your results.

Also, explain whether your experiment uses a within-groups or between-groups design.

For example: "The experiment used a 3x2 between-subjects design. The independent variables were age and understanding of second-order beliefs."

The next part of your method section should detail the procedures used in your experiment. Your procedures should explain:

- What the participants did

- How data was collected

- The order in which steps occurred

For example: "An examiner interviewed children individually at their school in one session that lasted 20 minutes on average. The examiner explained to each child that he or she would be told two short stories and that some questions would be asked after each story. All sessions were videotaped so the data could later be coded."

Keep this subsection concise yet detailed. Explain what you did and how you did it, but do not overwhelm your readers with too much information.

Tips for How to Write a Methods Section

In addition to following the basic structure of an APA method section, there are also certain things you should remember when writing this section of your paper. Consider the following tips when writing this section:

- Use the past tense : Always write the method section in the past tense.

- Be descriptive : Provide enough detail that another researcher could replicate your experiment, but focus on brevity. Avoid unnecessary detail that is not relevant to the outcome of the experiment.

- Use an academic tone : Use formal language and avoid slang or colloquial expressions. Word choice is also important. Refer to the people in your experiment or study as "participants" rather than "subjects."

- Use APA format : Keep a style guide on hand as you write your method section. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association is the official source for APA style.

- Make connections : Read through each section of your paper for agreement with other sections. If you mention procedures in the method section, these elements should be discussed in the results and discussion sections.

- Proofread : Check your paper for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors.. typos, grammar problems, and spelling errors. Although a spell checker is a handy tool, there are some errors only you can catch.

After writing a draft of your method section, be sure to get a second opinion. You can often become too close to your work to see errors or lack of clarity. Take a rough draft of your method section to your university's writing lab for additional assistance.

A Word From Verywell

The method section is one of the most important components of your APA format paper. The goal of your paper should be to clearly detail what you did in your experiment. Provide enough detail that another researcher could replicate your study if they wanted.

Finally, if you are writing your paper for a class or for a specific publication, be sure to keep in mind any specific instructions provided by your instructor or by the journal editor. Your instructor may have certain requirements that you need to follow while writing your method section.

Frequently Asked Questions

While the subsections can vary, the three components that should be included are sections on the participants, the materials, and the procedures.

- Describe who the participants were in the study and how they were selected.

- Define and describe the materials that were used including any equipment, tests, or assessments

- Describe how the data was collected

To write your methods section in APA format, describe your participants, materials, study design, and procedures. Keep this section succinct, and always write in the past tense. The main heading of this section should be labeled "Method" and it should be centered, bolded, and capitalized. Each subheading within this section should be bolded, left-aligned and in title case.

The purpose of the methods section is to describe what you did in your experiment. It should be brief, but include enough detail that someone could replicate your experiment based on this information. Your methods section should detail what you did to answer your research question. Describe how the study was conducted, the study design that was used and why it was chosen, and how you collected the data and analyzed the results.

Erdemir F. How to write a materials and methods section of a scientific article ? Turk J Urol . 2013;39(Suppl 1):10-5. doi:10.5152/tud.2013.047

Kallet RH. How to write the methods section of a research paper . Respir Care . 2004;49(10):1229-32. PMID: 15447808.

American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). Washington DC: The American Psychological Association; 2019.

American Psychological Association. APA Style Journal Article Reporting Standards . Published 2020.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Case Study Research Method in Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. Typically, data is gathered from various sources using several methods (e.g., observations & interviews).

The case study research method originated in clinical medicine (the case history, i.e., the patient’s personal history). In psychology, case studies are often confined to the study of a particular individual.

The information is mainly biographical and relates to events in the individual’s past (i.e., retrospective), as well as to significant events that are currently occurring in his or her everyday life.

The case study is not a research method, but researchers select methods of data collection and analysis that will generate material suitable for case studies.

Freud (1909a, 1909b) conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

This makes it clear that the case study is a method that should only be used by a psychologist, therapist, or psychiatrist, i.e., someone with a professional qualification.

There is an ethical issue of competence. Only someone qualified to diagnose and treat a person can conduct a formal case study relating to atypical (i.e., abnormal) behavior or atypical development.

Famous Case Studies

- Anna O – One of the most famous case studies, documenting psychoanalyst Josef Breuer’s treatment of “Anna O” (real name Bertha Pappenheim) for hysteria in the late 1800s using early psychoanalytic theory.

- Little Hans – A child psychoanalysis case study published by Sigmund Freud in 1909 analyzing his five-year-old patient Herbert Graf’s house phobia as related to the Oedipus complex.

- Bruce/Brenda – Gender identity case of the boy (Bruce) whose botched circumcision led psychologist John Money to advise gender reassignment and raise him as a girl (Brenda) in the 1960s.

- Genie Wiley – Linguistics/psychological development case of the victim of extreme isolation abuse who was studied in 1970s California for effects of early language deprivation on acquiring speech later in life.

- Phineas Gage – One of the most famous neuropsychology case studies analyzes personality changes in railroad worker Phineas Gage after an 1848 brain injury involving a tamping iron piercing his skull.

Clinical Case Studies

- Studying the effectiveness of psychotherapy approaches with an individual patient

- Assessing and treating mental illnesses like depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD

- Neuropsychological cases investigating brain injuries or disorders

Child Psychology Case Studies

- Studying psychological development from birth through adolescence

- Cases of learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, ADHD

- Effects of trauma, abuse, deprivation on development

Types of Case Studies

- Explanatory case studies : Used to explore causation in order to find underlying principles. Helpful for doing qualitative analysis to explain presumed causal links.

- Exploratory case studies : Used to explore situations where an intervention being evaluated has no clear set of outcomes. It helps define questions and hypotheses for future research.

- Descriptive case studies : Describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred. It is helpful for illustrating certain topics within an evaluation.

- Multiple-case studies : Used to explore differences between cases and replicate findings across cases. Helpful for comparing and contrasting specific cases.

- Intrinsic : Used to gain a better understanding of a particular case. Helpful for capturing the complexity of a single case.

- Collective : Used to explore a general phenomenon using multiple case studies. Helpful for jointly studying a group of cases in order to inquire into the phenomenon.

Where Do You Find Data for a Case Study?

There are several places to find data for a case study. The key is to gather data from multiple sources to get a complete picture of the case and corroborate facts or findings through triangulation of evidence. Most of this information is likely qualitative (i.e., verbal description rather than measurement), but the psychologist might also collect numerical data.

1. Primary sources

- Interviews – Interviewing key people related to the case to get their perspectives and insights. The interview is an extremely effective procedure for obtaining information about an individual, and it may be used to collect comments from the person’s friends, parents, employer, workmates, and others who have a good knowledge of the person, as well as to obtain facts from the person him or herself.

- Observations – Observing behaviors, interactions, processes, etc., related to the case as they unfold in real-time.

- Documents & Records – Reviewing private documents, diaries, public records, correspondence, meeting minutes, etc., relevant to the case.

2. Secondary sources

- News/Media – News coverage of events related to the case study.

- Academic articles – Journal articles, dissertations etc. that discuss the case.

- Government reports – Official data and records related to the case context.

- Books/films – Books, documentaries or films discussing the case.

3. Archival records

Searching historical archives, museum collections and databases to find relevant documents, visual/audio records related to the case history and context.

Public archives like newspapers, organizational records, photographic collections could all include potentially relevant pieces of information to shed light on attitudes, cultural perspectives, common practices and historical contexts related to psychology.

4. Organizational records

Organizational records offer the advantage of often having large datasets collected over time that can reveal or confirm psychological insights.

Of course, privacy and ethical concerns regarding confidential data must be navigated carefully.

However, with proper protocols, organizational records can provide invaluable context and empirical depth to qualitative case studies exploring the intersection of psychology and organizations.

- Organizational/industrial psychology research : Organizational records like employee surveys, turnover/retention data, policies, incident reports etc. may provide insight into topics like job satisfaction, workplace culture and dynamics, leadership issues, employee behaviors etc.

- Clinical psychology : Therapists/hospitals may grant access to anonymized medical records to study aspects like assessments, diagnoses, treatment plans etc. This could shed light on clinical practices.

- School psychology : Studies could utilize anonymized student records like test scores, grades, disciplinary issues, and counseling referrals to study child development, learning barriers, effectiveness of support programs, and more.

How do I Write a Case Study in Psychology?

Follow specified case study guidelines provided by a journal or your psychology tutor. General components of clinical case studies include: background, symptoms, assessments, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Interpreting the information means the researcher decides what to include or leave out. A good case study should always clarify which information is the factual description and which is an inference or the researcher’s opinion.

1. Introduction

- Provide background on the case context and why it is of interest, presenting background information like demographics, relevant history, and presenting problem.

- Compare briefly to similar published cases if applicable. Clearly state the focus/importance of the case.

2. Case Presentation

- Describe the presenting problem in detail, including symptoms, duration,and impact on daily life.

- Include client demographics like age and gender, information about social relationships, and mental health history.

- Describe all physical, emotional, and/or sensory symptoms reported by the client.

- Use patient quotes to describe the initial complaint verbatim. Follow with full-sentence summaries of relevant history details gathered, including key components that led to a working diagnosis.

- Summarize clinical exam results, namely orthopedic/neurological tests, imaging, lab tests, etc. Note actual results rather than subjective conclusions. Provide images if clearly reproducible/anonymized.

- Clearly state the working diagnosis or clinical impression before transitioning to management.

3. Management and Outcome

- Indicate the total duration of care and number of treatments given over what timeframe. Use specific names/descriptions for any therapies/interventions applied.

- Present the results of the intervention,including any quantitative or qualitative data collected.

- For outcomes, utilize visual analog scales for pain, medication usage logs, etc., if possible. Include patient self-reports of improvement/worsening of symptoms. Note the reason for discharge/end of care.

4. Discussion

- Analyze the case, exploring contributing factors, limitations of the study, and connections to existing research.

- Analyze the effectiveness of the intervention,considering factors like participant adherence, limitations of the study, and potential alternative explanations for the results.

- Identify any questions raised in the case analysis and relate insights to established theories and current research if applicable. Avoid definitive claims about physiological explanations.

- Offer clinical implications, and suggest future research directions.

5. Additional Items

- Thank specific assistants for writing support only. No patient acknowledgments.

- References should directly support any key claims or quotes included.

- Use tables/figures/images only if substantially informative. Include permissions and legends/explanatory notes.

- Provides detailed (rich qualitative) information.

- Provides insight for further research.

- Permitting investigation of otherwise impractical (or unethical) situations.

Case studies allow a researcher to investigate a topic in far more detail than might be possible if they were trying to deal with a large number of research participants (nomothetic approach) with the aim of ‘averaging’.

Because of their in-depth, multi-sided approach, case studies often shed light on aspects of human thinking and behavior that would be unethical or impractical to study in other ways.

Research that only looks into the measurable aspects of human behavior is not likely to give us insights into the subjective dimension of experience, which is important to psychoanalytic and humanistic psychologists.

Case studies are often used in exploratory research. They can help us generate new ideas (that might be tested by other methods). They are an important way of illustrating theories and can help show how different aspects of a person’s life are related to each other.

The method is, therefore, important for psychologists who adopt a holistic point of view (i.e., humanistic psychologists ).

Limitations

- Lacking scientific rigor and providing little basis for generalization of results to the wider population.

- Researchers’ own subjective feelings may influence the case study (researcher bias).

- Difficult to replicate.

- Time-consuming and expensive.

- The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources.

Because a case study deals with only one person/event/group, we can never be sure if the case study investigated is representative of the wider body of “similar” instances. This means the conclusions drawn from a particular case may not be transferable to other settings.

Because case studies are based on the analysis of qualitative (i.e., descriptive) data , a lot depends on the psychologist’s interpretation of the information she has acquired.

This means that there is a lot of scope for Anna O , and it could be that the subjective opinions of the psychologist intrude in the assessment of what the data means.

For example, Freud has been criticized for producing case studies in which the information was sometimes distorted to fit particular behavioral theories (e.g., Little Hans ).

This is also true of Money’s interpretation of the Bruce/Brenda case study (Diamond, 1997) when he ignored evidence that went against his theory.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on hysteria . Standard Edition 2: London.

Curtiss, S. (1981). Genie: The case of a modern wild child .

Diamond, M., & Sigmundson, K. (1997). Sex Reassignment at Birth: Long-term Review and Clinical Implications. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine , 151(3), 298-304

Freud, S. (1909a). Analysis of a phobia of a five year old boy. In The Pelican Freud Library (1977), Vol 8, Case Histories 1, pages 169-306

Freud, S. (1909b). Bemerkungen über einen Fall von Zwangsneurose (Der “Rattenmann”). Jb. psychoanal. psychopathol. Forsch ., I, p. 357-421; GW, VII, p. 379-463; Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis, SE , 10: 151-318.

Harlow J. M. (1848). Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 39 , 389–393.

Harlow, J. M. (1868). Recovery from the Passage of an Iron Bar through the Head . Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society. 2 (3), 327-347.

Money, J., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & Woman, Boy & Girl : The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Money, J., & Tucker, P. (1975). Sexual signatures: On being a man or a woman.

Further Information

- Case Study Approach

- Case Study Method

- Enhancing the Quality of Case Studies in Health Services Research

- “We do things together” A case study of “couplehood” in dementia

- Using mixed methods for evaluating an integrative approach to cancer care: a case study

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Help | Advanced Search

Computer Science > Computation and Language

Title: detection and positive reconstruction of cognitive distortion sentences: mandarin dataset and evaluation.

Abstract: This research introduces a Positive Reconstruction Framework based on positive psychology theory. Overcoming negative thoughts can be challenging, our objective is to address and reframe them through a positive reinterpretation. To tackle this challenge, a two-fold approach is necessary: identifying cognitive distortions and suggesting a positively reframed alternative while preserving the original thought's meaning. Recent studies have investigated the application of Natural Language Processing (NLP) models in English for each stage of this process. In this study, we emphasize the theoretical foundation for the Positive Reconstruction Framework, grounded in broaden-and-build theory. We provide a shared corpus containing 4001 instances for detecting cognitive distortions and 1900 instances for positive reconstruction in Mandarin. Leveraging recent NLP techniques, including transfer learning, fine-tuning pretrained networks, and prompt engineering, we demonstrate the effectiveness of automated tools for both tasks. In summary, our study contributes to multilingual positive reconstruction, highlighting the effectiveness of NLP in cognitive distortion detection and positive reconstruction.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- HTML (experimental)

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Lines represent modeled weighted prevalence by survey month, modeled nonlinearly using restricted cubic splines (5 knots). Shaded bands represent SEs. Points represent observed weighted prevalence by month.

Graphs show trends by age (A), gender (B), social grade (C), children in the household (D), smoking status (E), and drinking risk status (F). Lines represent modeled weighted prevalence by survey month, modeled nonlinearly using restricted cubic splines (5 knots). Shaded bands represent SEs. Points represent observed weighted prevalence by month.

eTable 1. Weighted Characteristics of the Analysed Sample Compared With Participants Excluded on the Basis of Missing Distress Data

eTable 2. Weighted Prevalence of Psychological Distress Among Adults in England, by AUDIT-C Score and 3-Level Drinking Risk Status: Data Aggregated Across the Study Period (April 2020-December 2022)

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Jackson SE , Brown J , Shahab L , McNeill A , Munafò MR , Brose L. Trends in Psychological Distress Among Adults in England, 2020-2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321959. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21959

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Trends in Psychological Distress Among Adults in England, 2020-2022

- 1 Department of Behavioural Science and Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2 SPECTRUM Consortium, United Kingdom

- 3 Addictions Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

- 4 MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, School of Psychological Science, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

Question How has the prevalence of psychological distress in the adult population of England changed since 2020?

Findings This survey study of 51 861 adults found that the proportion reporting severe levels of distress increased steadily by 46%, from an already elevated baseline, since the start of the pandemic. This increase in severe distress occurred across all population subgroups, with the exception of older adults (aged ≥65 years), and was most pronounced in young adults (aged 18-24 years).

Meaning These findings provide evidence of a growing mental health crisis in England and underscore an urgent need to address its cause and to adequately fund mental health services.

Importance In the last 3 years, people in England have lived through a pandemic and cost-of-living and health care crises, all of which may have contributed to worsening mental health in the population.

Objective To estimate trends in psychological distress among adults over this period and to examine differences by key potential moderators.

Design, Setting, and Participants A monthly cross-sectional, nationally representative household survey of adults aged 18 years or older was conducted in England between April 2020 and December 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures Past-month distress was assessed with the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. Time trends in any distress (moderate to severe, scores ≥5) and severe distress (scores ≥13) were modeled, and interactions with age, gender, occupational social grade, children in the household, smoking status, and drinking risk status were tested.

Results Data were collected from 51 861 adults (weighted mean [SD] age, 48.6 [18.5] years; 26 609 women [51.3%]). There was little overall change in the proportion of respondents reporting any distress (from 34.5% to 32.0%; prevalence ratio [PR], 0.93; 95% CI, 0.87-0.99), but the proportion reporting severe distress increased by 46%, from 5.7% to 8.3% (PR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.21-1.76). Although trends differed by sociodemographic characteristics, smoking, and drinking, the increase in severe distress was observed across all subgroups (with PR estimates ranging from 1.17 to 2.16), with the exception of those aged 65 years and older (PR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.43-1.38); the increase was particularly pronounced since late 2021 among those younger than 25 years (increasing from 13.6% in December 2021 to 20.2% in December 2022).

Conclusions and Relevance In this survey study of adults in England, the proportion reporting any psychological distress was similar in December 2022 to that in April 2020 (an extremely difficult and uncertain moment of the COVID-19 pandemic), but the proportion reporting severe distress was 46% higher. These findings provide evidence of a growing mental health crisis in England and underscore an urgent need to address its cause and to adequately fund mental health services.

Since 2020, England has undergone a period of substantial societal instability that may have contributed to worsening mental health. The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it an assortment of stressors, including fear of risk of infection, work and school closures, reduced social contact, financial strain, and uncertainty about the future. 1 - 3 There has been a cost-of-living crisis in the UK since late 2021, whereby high rates of inflation have caused the cost of everyday essentials like groceries, energy, and household bills to increase faster than average household incomes. 4 This has led to widespread industrial action since mid-2022, with unions across industries (including railways, the National Health Service, and education) striking for wage increases in line with inflation. There is also an ongoing health care crisis that has seen increased pressures on the National Health Service and across the health and social care sector, resulting in substantial delays for patients seeking emergency care. 5 , 6 These national pressures have occurred in the context of other international emergencies, including the climate crisis and the war in Ukraine. Collectively, these circumstances may have increased levels of psychological distress in the population, particularly among groups with less disposable income or other vulnerabilities. 7 It is important to understand whether, how, and among which groups there have been long-term shifts in population mental health burden, because this will have implications for service needs. 8

Mental health problems are not experienced equally across population groups. Previous studies 9 - 11 have identified a number of sociodemographic groups at greater risk of psychological distress, including younger adults, women, and people who are less socioeconomically advantaged (indicated by unemployment or lower income, education, or occupational status). Factors relating to family and household structure, including being single, living alone, and (less consistently) having children in the home have also been linked to poorer mental health, 11 - 13 as have behaviors such as smoking and heavy alcohol consumption. 14 - 17 Many of the groups who have historically had higher levels of distress have also experienced greater hardship during recent years, which may have compounded inequalities in mental health. For example, the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic had greater social and financial impacts on younger adults, women, and those with lower incomes 18 - 21 (although COVID-19 mortality rates were higher among older adults, men, and minoritized racial and ethnic groups 22 ). The cost-of-living crisis has seen particularly high rates of food insecurity in households with children and those receiving state benefits. 23 More recently, the health care crisis is likely to disproportionately affect groups who seek emergency care more frequently, including older adults, people from socioeconomically deprived areas, people who smoke, and those drinking at high-risk levels. 24 - 26

Studies 27 - 32 conducted early in the COVID-19 pandemic showed an acute increase in psychological distress and mental health symptoms in the UK population. Although these changes were observed across most population subgroups sampled, some studies reported greater deterioration in mental health among certain groups, including younger adults, women, those with greater socioeconomic disadvantage, and those with children in the home, 27 , 28 , 32 - 35 the same groups experiencing greater social and financial impacts early in the pandemic. 18 - 21 According to the nationally representative UK Household Longitudinal Study, 35 the prevalence of clinically significant distress returned to prepandemic levels by September 2020, after restrictions on social interaction were eased. However, levels of distress increased again when the second wave of COVID-19 hit the UK in late 2020, with a particularly pronounced increase among those with school-aged children at home. 33 How levels of psychological distress have continued to change in the context of subsequent waves of the pandemic, the cost-of-living crisis, the health care crisis, and other global issues—and the extent to which changes have differed between groups—is not known.

The Smoking and Alcohol Toolkit Study has been collecting data on psychological distress from a representative sample of adults in England each month since April 2020 (the first wave of data collected after the COVID-19 pandemic began to affect England in March 2020). It is, therefore, well placed to provide up-to-date descriptive information on levels of psychological distress and insight into trends over the entirety of this unstable period to date. This study used these data to estimate time trends in psychological distress and to explore differences by key potential moderators to identify high-risk groups. Specifically, we aimed to address 2 research questions. First, how has the prevalence of any and severe past-30-day psychological distress among adults in England changed since April 2020? Second, to what extent have changes in any and severe past-30-day psychological distress differed by age, gender, socioeconomic position (indexed by occupational social grade), presence of children in the household, smoking status, and drinking risk status?

This survey study used data from the ongoing Smoking and Alcohol Toolkit Study, a monthly cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of adults (aged ≥18 years) living in households in England. 36 , 37 The study uses a hybrid of random probability and simple quota sampling to select a new sample of approximately 1700 adults each month. Since April 2020, data have been collected via computer-assisted telephone interview. Comparisons with other national surveys indicate that key variables such as sociodemographic characteristics are nationally representative. 36 For the present study, we analyzed trends in psychological distress in the period from April 2020 (the first data collected after the COVID-19 pandemic began to affect England) to December 2022 (the most recent data available at the time of analysis).

Ethical approval for the Smoking and Alcohol Toolkit Study was granted originally by the University College London ethics committee. The data are collected by Ipsos Mori and are anonymized when received by University College London. All participants provide verbal informed consent. The study conformed to American Association for Public Opinion Research ( AAPOR ) reporting guideline for survey research.

Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, which measures nonspecific psychological distress in the past month. 38 , 39 It uses 6 questions: “During the past 30 days, about how often, if at all, did you feel (1) nervous, (2) hopeless, (3) restless or fidgety, (4) so depressed that nothing could cheer you up, (5) that everything was an effort, and (6) worthless?”

Responses were a 5-point scale, from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time) and were summed across items to produce a total score ranging from 0 to 24. We used established cutoffs to define severe (scores ≥13), moderate (scores 5-12) and no or minimal (scores <5) psychological distress. 40 We analyzed any moderate or severe distress (scores ≥5) as our primary outcome referred to as any distress, and severe distress (scores ≥13) as a secondary outcome.

Age was categorized as 18 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 49, 50 to 64, or 65 or more years. Gender was self-reported as man, woman, or in another way and summarized descriptively. Those who identify in another way were excluded from the trend analyses by gender because of the low numbers.

Occupational social grade was categorized as AB (higher and intermediate managerial, administrative, and professional), C1 (supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, administrative, and professional), C2 (skilled manual workers), D (semiskilled and unskilled manual workers), and E (state pensioners, casual and lowest grade workers, and unemployed with state benefits only). 41 The number of children in the household was self-reported and categorized as 0, 1, or 2 or more. Smoking status was self-reported and categorized as current, former, or never smoking.

Drinking risk status was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption. Scores of 5 or higher were defined as drinking at increasing or higher-risk levels (ie, levels that increase someone’s risk of harm), and scores less than 5 were defined as drinking at low-risk levels or not drinking. 42

The analysis plan was preregistered on Open Science Framework. 43 Data were analyzed in R statistical software version 4.2.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing). We excluded participants with missing data on our outcome of interest (psychological distress). Those with missing data on potential moderators were excluded on a per-analysis basis.

The Smoking and Alcohol Toolkit Study uses raking to weight the sample to the population in England on the dimensions of age, social grade, region, housing tenure, ethnicity, and working status within sex. 44 This profile is determined each month by combining data from the 2011 UK Census, the Office for National Statistics midyear estimates, and the annual National Readership Survey. 36 The following analyses used weighted data.

We used log-binomial regression to test the association of (1) any and (2) severe psychological distress with survey month. Survey month was modeled using restricted cubic splines with 5 knots, to allow associations with time to be flexible and nonlinear, while avoiding categorization.

To explore moderation by age, gender, social grade, presence of children in the household, smoking, and drinking risk status, we repeated the models including the interaction between the moderator of interest and survey month, thus allowing for time trends to differ across subgroups. Each of the interactions was tested in a separate model. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. We used predicted estimates from our models to plot the prevalence of each outcome over the study period (overall and by moderating variables), alongside unadjusted (weighted) data, and reported prevalence ratios (PRs) for the change in prevalence across the whole time-series (December 2022 vs April 2020) alongside 95% CIs calculated using bootstrapping.

A total of 53 370 adults in England participated in the Smoking and Alcohol Toolkit Study between April 2020 and December 2022 (mean [SD], 1617 [42.1] participants per month). We excluded 1509 participants (2.8%) with missing data on distress, leaving an analytic sample of 51 861 participants (weighted mean [SD] age, 48.6 [18.5] years; 26 609 women [51.3%]). Compared with the analyzed sample, the group excluded for missing distress overrepresented people who were aged 18 to 24 years or 65 years and older, described their gender in another way, were from social grades C1 and E, currently smoked, drank at low-risk levels or not at all, and those who were surveyed in 2022 (eTable 1 in Supplement 1 ).

Across the study period, 30.0% of adults reported any distress, and 6.2% reported severe distress ( Table 1 ). Groups with notably higher prevalence of any and severe distress included younger adults, women and those who describe their gender in another way, those from less advantaged social grades, and those who currently smoke ( Table 1 ). In addition, those with 1 child in the household had slightly higher prevalence of any distress than those with no children or 2 or more children, and those not drinking or drinking at low-risk levels had slightly higher prevalence of severe distress than those drinking at high-risk levels ( Table 1 ). When we looked at differences by drinking risk status in more detail in an unplanned analysis, using the full spectrum of Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption scores, we saw the highest prevalence at either ends of the scale (ie, among those with the highest scores and not drinking; see eTable 2 in Supplement 1 ).

The proportion of adults reporting any distress decreased from 34.5% to 28.0% between April 2020 and May 2021, then increased to 32.0% by December 2022 ( Figure 1 ), such that there was little overall change from the start to the end of the study period (PR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.87-0.99) ( Table 2 ). A significant overall decrease in any distress between April 2020 and December 2022 was observed among those aged 65 years and older (PR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.46-0.68), women (PR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93), those from social grade C1 (PR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.95), those with no children in the household (PR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.97), those reporting never smoking (PR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.81-0.996) or former smoking (PR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98), and those not drinking or drinking at low-risk levels (PR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93). No significant changes were observed in other subgroups (with PR estimates ranging from 0.88 to 1.08) ( Table 2 ).

However, trends in the prevalence of any distress within the study period differed significantly by all sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics ( Figure 2 ). People aged 65 years and older showed different patterns of any distress compared with younger age groups—a more pronounced decline during 2020 and a decrease in any distress since late 2021—whereas the prevalence increased among younger adults ( Figure 2 A). There was a decrease in any distress during 2020 among women, but little change among men ( Figure 2 B). After an initial decrease in any distress across social grades (with the exception of C2, where the prevalence was stable), the subsequent increase occurred soonest among those in social grade E and latest among those in social grades AB (with C2 the only group to show a fall in 2022) ( Figure 2 C). People with 1 child in the household had the highest prevalence of any distress in April 2020 and a more pronounced decline through mid-2021; in addition, from late 2021, there was an increase in any distress among those with 1 or more children in the household, whereas the prevalence remained stable among those with no children in the household ( Figure 2 D). People who used to smoke showed a more pronounced decline in any distress during 2020 than those who currently or never smoked, and those who currently smoke showed a more pronounced increase since mid-2021 ( Figure 2 E). Those not drinking or drinking at low-risk levels showed a more pronounced decline in any distress during 2020 than those drinking at high-risk levels, and the latter group showed a more pronounced increase in any distress in 2022 ( Figure 2 F).

The proportion of adults reporting severe distress increased by 46% between April 2020 and December 2022 (PR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.21-1.76) ( Table 2 ), increasing steadily from 5.7% to 8.3% with no period of decline ( Figure 1 ). An overall increase in severe distress between April 2020 and December 2022 was observed across all subgroups (with PR estimates ranging from 1.17 to 2.16) ( Table 2 ), with the exception of those aged 65 years and older (PR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.43-1.38). Of note, the proportion reporting severe distress increased by 9 percentage points among people younger than 25 years and by 5 percentage points among those from the most disadvantaged social grades (D and E) and current smokers.

Time trends in the prevalence of severe distress within the study period differed significantly by age ( P for interaction = .01) and drinking risk status ( P for interaction < .001). From late 2021, there was a sharp increase in severe distress among participants aged 18 to 24 years (from 13.6% in December 2021 to 20.2% in December 2022); smaller increases among those aged 25 to 34 years (from 9.9% in December 2021 to 11.7% in December 2022), those aged 35 to 49 years (from 6.1% in December 2021 to 7.2% in December 2022), and those aged 50 to 64 years (from 4.9% in December 2021 to 6.2% in December 2022); and no change among those aged 65 years and older (2.5% at both time points). Nearer the end of the study (April 2022 to December 2022), there was an increase in severe distress among those drinking at high-risk levels (from 6.2% to 9.7%), whereas levels remained stable among those not drinking or drinking at low-risk levels (at approximately 7%) ( Figure 3 F). Tests of interactions were inconclusive across other characteristics (with P for interaction ranging from .06 to .11) ( Figure 3 ).

Between April 2020 and December 2022, there was little overall change in the proportion of adults in England reporting any distress (declining from 34.5% to 32.0%; PR, 0.93) but the proportion reporting severe distress increased by almost one-half from 5.7% to 8.3% (PR, 1.46). Within this period, the prevalence of any distress declined between April 2020 and May 2021 and then returned to slightly below baseline levels by December 2022, whereas the prevalence of severe distress increased consistently. It is important to note that the baseline assessment was conducted in April 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when people were experiencing substantial disruption to their daily lives and fear and anxiety about the pandemic (eg, they or loved ones contracting and becoming seriously ill from COVID-19) were at their highest. 45 Other studies documented a notable increase in distress during the early months of the pandemic; for example, in the UK Household Longitudinal Study (a nationally representative panel study), the prevalence of clinically significant psychological distress (defined as a score of ≥4 of 12 on the General Health Questionnaire–12) increased from 21% before the pandemic (2019) to 30% in April 2020. 35 This makes our findings even more concerning: the prevalence of any distress among adults in England at the end of the study (in December 2022) was only slightly lower than at the start of the pandemic, and the prevalence of severe distress was 46% higher.

There was a pronounced age gradient across the study period, with the lowest prevalence of both any and severe distress among the oldest age group (aged ≥65 years) and the highest prevalence among the youngest group (aged 18-24 years). The decline in any distress during the first year of the study was particularly pronounced among those aged 65 years and older. The participants aged 65 years and older were also the only subgroup we looked at not to show an increase in severe distress. Given that the health risks associated with COVID-19 were greatest for this age group, 22 this group had the most reason to have comparatively high levels of distress at the start of this period. Over time, they benefited the most from the continued rollout of the vaccination program in terms of their reduction in risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes. 46 Meanwhile, those aged 18 to 24 years showed the sharpest increase in severe distress, particularly in the last year of the study (increasing from 13.6% in December 2021 to 20.2% in December 2022). This younger group may have been more affected than older groups by recent stressors, such as the cost-of-living crisis (because they typically have less disposable income 47 ), the climate crisis, and war in Ukraine. Regardless of the cause, the fact that 1 in 5 young adults reports severe distress is a cause for concern and warrants action by policy makers.

As has been observed in previous studies, 35 , 48 women reported higher levels of distress than men. There was a decrease in any distress in 2020 among women but little change among men, which narrowed the gender gap but did not close it entirely. This result may reflect easing of the childcare burden during the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately fell on women. 19 , 20 The prevalence of distress was also very high among those who described their gender in another way—substantially greater than those identifying as women or men—across the whole period, but we were unable to analyze trends in this group owing to the small sample size.

Occupational social grade was negatively associated with distress, consistent with previous literature documenting a substantial socioeconomic gradient in health, including mental health and well-being. 49 , 50 The increases in prevalence of any and severe distress we observed occurred soonest among social grade E (the most disadvantaged group). This group started from a high baseline and experienced a large 5 percentage point increase in severe distress. This may be explained by this group being hit earlier by the cost-of-living crisis, because they had less disposable income to absorb increasing costs of household essentials. A survey 51 conducted in July 2022 found that almost one-half (42%) of people living in the most deprived quintile of areas in England had cut back on food and essentials since the cost-of-living crisis began, compared with 27% in the least deprived quintile.

Patterns of distress varied by the number of children in the household. Those with 1 child had the highest prevalence of any distress at the start of the study period in April 2020 than those with none or multiple children. It is possible that this may be because 2 or more children provided company for each other, meaning parents were less worried about a lack of interaction with peers or the need to provide entertainment during lockdown. There was an increase in any distress among those with 1 or more children since late 2021, which may be linked to the additional strain having children puts on household budgets 52 in the context of the cost-of-living crisis. Parents may also be concerned about their children’s futures, for example due to impending climate hazards.

The prevalence of distress was elevated among those who currently smoked. It is a common misconception that smoking helps to relieve stress, 53 when in fact levels of distress are typically higher among people who smoke and decrease when people quit. 54 The most pronounced decline in any distress in the early part of the study period was observed among people who reported former smoking. This was likely confounded with age, since former smokers are, on average, older than never and current smokers. 55 Similarly, the increase in any distress in the later part of the study was more pronounced among those who currently smoked, which is likely confounded with social grade as smoking is much more common among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. 56

Levels of distress were similar between those drinking at high-risk levels and those not drinking or drinking at low-risk levels. This was explained by relatively higher prevalence of distress among people not drinking, which may be caused by those in poor health (and thereby greater distress) abstaining from drinking 57 (levels of distress were higher among those drinking at high-risk than those reporting low-risk levels of consumption). There was a more pronounced increase in distress near the end of the study period among those drinking at high-risk levels. It is possible that people experiencing distress related to the cost-of-living crisis or other stressors around this period were using alcohol as a coping strategy. 58 The high burden of mental health problems in England is not necessarily a new concern, 59 but the COVID-19 pandemic, cost-of-living crisis, and other stressors appear to have exacerbated the problem and caused existing inequalities in mental health to deepen. Groups with particularly high prevalence of distress include young adults, women, those who describe their gender in another way, people from more disadvantaged social grades, and people who smoke. Mitigating and managing these mental health needs requires adequately resourced services. 60

This study had several limitations. Because it was a household survey, people too unwell to participate or those living in institutions were excluded, so the findings may underestimate levels of distress by excluding those experiencing severe mental health problems. In addition, although the sample was representative, the small proportion (2.8%) of participants who did not respond to the measure of distress tended to belong to groups with higher levels of distress (eg, those aged 18-24 years or describing their gender in another way), which may bias estimates of prevalence downward, as has been noted in previous studies. 61 The numbers of participants reporting severe distress were small, limiting statistical power to detect significant differences in time trends between subgroups. Data on psychological distress were not collected in the survey before April 2020, so we were unable to draw comparisons with the prepandemic period. In addition, the survey did not capture other variables that may have been associated with changes in distress since April 2020, such as ethnicity, family circumstances (eg, living alone and marital status), economic factors (eg, job loss and food insecurity), or health status (eg, disability and diagnosed conditions). Nonetheless, it provides a comprehensive summary of trends in distress over this period. Although we have speculated on the potential causes of the patterns of distress we have observed across population groups, further research (eg, qualitative) is required to provide deeper insight into the factors that have caused a surge in the proportion of adults experiencing distress, how they differ between population groups, and how to reduce their impact.