An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Prev Med

Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research

Vishnu renjith.

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Royal College of Surgeons Ireland - Bahrain (RCSI Bahrain), Al Sayh Muharraq Governorate, Bahrain

Renjulal Yesodharan

1 Department of Mental Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Judith A. Noronha

2 Department of OBG Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Elissa Ladd

3 School of Nursing, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, USA

Anice George

4 Department of Child Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate robust evidence about important issues in the fields of medicine and healthcare. Qualitative research has ample possibilities within the arena of healthcare research. This article aims to inform healthcare professionals regarding qualitative research, its significance, and applicability in the field of healthcare. A wide variety of phenomena that cannot be explained using the quantitative approach can be explored and conveyed using a qualitative method. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research. The greatest strength of the qualitative research approach lies in the richness and depth of the healthcare exploration and description it makes. In health research, these methods are considered as the most humanistic and person-centered way of discovering and uncovering thoughts and actions of human beings.

Introduction

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate trustworthy evidence about issues in the field of medicine and healthcare. The three principal approaches to health research are the quantitative, the qualitative, and the mixed methods approach. The quantitative research method uses data, which are measures of values and counts and are often described using statistical methods which in turn aids the researcher to draw inferences. Qualitative research incorporates the recording, interpreting, and analyzing of non-numeric data with an attempt to uncover the deeper meanings of human experiences and behaviors. Mixed methods research, the third methodological approach, involves collection and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative information with an objective to solve different but related questions, or at times the same questions.[ 1 , 2 ]

In healthcare, qualitative research is widely used to understand patterns of health behaviors, describe lived experiences, develop behavioral theories, explore healthcare needs, and design interventions.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] Because of its ample applications in healthcare, there has been a tremendous increase in the number of health research studies undertaken using qualitative methodology.[ 4 , 5 ] This article discusses qualitative research methods, their significance, and applicability in the arena of healthcare.

Qualitative Research

Diverse academic and non-academic disciplines utilize qualitative research as a method of inquiry to understand human behavior and experiences.[ 6 , 7 ] According to Munhall, “Qualitative research involves broadly stated questions about human experiences and realities, studied through sustained contact with the individual in their natural environments and producing rich, descriptive data that will help us to understand those individual's experiences.”[ 8 ]

Significance of Qualitative Research

The qualitative method of inquiry examines the 'how' and 'why' of decision making, rather than the 'when,' 'what,' and 'where.'[ 7 ] Unlike quantitative methods, the objective of qualitative inquiry is to explore, narrate, and explain the phenomena and make sense of the complex reality. Health interventions, explanatory health models, and medical-social theories could be developed as an outcome of qualitative research.[ 9 ] Understanding the richness and complexity of human behavior is the crux of qualitative research.

Differences between Quantitative and Qualitative Research

The quantitative and qualitative forms of inquiry vary based on their underlying objectives. They are in no way opposed to each other; instead, these two methods are like two sides of a coin. The critical differences between quantitative and qualitative research are summarized in Table 1 .[ 1 , 10 , 11 ]

Differences between quantitative and qualitative research

Qualitative Research Questions and Purpose Statements

Qualitative questions are exploratory and are open-ended. A well-formulated study question forms the basis for developing a protocol, guides the selection of design, and data collection methods. Qualitative research questions generally involve two parts, a central question and related subquestions. The central question is directed towards the primary phenomenon under study, whereas the subquestions explore the subareas of focus. It is advised not to have more than five to seven subquestions. A commonly used framework for designing a qualitative research question is the 'PCO framework' wherein, P stands for the population under study, C stands for the context of exploration, and O stands for the outcome/s of interest.[ 12 ] The PCO framework guides researchers in crafting a focused study question.

Example: In the question, “What are the experiences of mothers on parenting children with Thalassemia?”, the population is “mothers of children with Thalassemia,” the context is “parenting children with Thalassemia,” and the outcome of interest is “experiences.”

The purpose statement specifies the broad focus of the study, identifies the approach, and provides direction for the overall goal of the study. The major components of a purpose statement include the central phenomenon under investigation, the study design and the population of interest. Qualitative research does not require a-priori hypothesis.[ 13 , 14 , 15 ]

Example: Borimnejad et al . undertook a qualitative research on the lived experiences of women suffering from vitiligo. The purpose of this study was, “to explore lived experiences of women suffering from vitiligo using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach.” [ 16 ]

Review of the Literature

In quantitative research, the researchers do an extensive review of scientific literature prior to the commencement of the study. However, in qualitative research, only a minimal literature search is conducted at the beginning of the study. This is to ensure that the researcher is not influenced by the existing understanding of the phenomenon under the study. The minimal literature review will help the researchers to avoid the conceptual pollution of the phenomenon being studied. Nonetheless, an extensive review of the literature is conducted after data collection and analysis.[ 15 ]

Reflexivity

Reflexivity refers to critical self-appraisal about one's own biases, values, preferences, and preconceptions about the phenomenon under investigation. Maintaining a reflexive diary/journal is a widely recognized way to foster reflexivity. According to Creswell, “Reflexivity increases the credibility of the study by enhancing more neutral interpretations.”[ 7 ]

Types of Qualitative Research Designs

The qualitative research approach encompasses a wide array of research designs. The words such as types, traditions, designs, strategies of inquiry, varieties, and methods are used interchangeably. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research.[ 1 , 7 , 10 ]

Narrative research

Narrative research focuses on exploring the life of an individual and is ideally suited to tell the stories of individual experiences.[ 17 ] The purpose of narrative research is to utilize 'story telling' as a method in communicating an individual's experience to a larger audience.[ 18 ] The roots of narrative inquiry extend to humanities including anthropology, literature, psychology, education, history, and sociology. Narrative research encompasses the study of individual experiences and learning the significance of those experiences. The data collection procedures include mainly interviews, field notes, letters, photographs, diaries, and documents collected from one or more individuals. Data analysis involves the analysis of the stories or experiences through “re-storying of stories” and developing themes usually in chronological order of events. Rolls and Payne argued that narrative research is a valuable approach in health care research, to gain deeper insight into patient's experiences.[ 19 ]

Example: Karlsson et al . undertook a narrative inquiry to “explore how people with Alzheimer's disease present their life story.” Data were collected from nine participants. They were asked to describe about their life experiences from childhood to adulthood, then to current life and their views about the future life. [ 20 ]

Phenomenological research

Phenomenology is a philosophical tradition developed by German philosopher Edmond Husserl. His student Martin Heidegger did further developments in this methodology. It defines the 'essence' of individual's experiences regarding a certain phenomenon.[ 1 ] The methodology has its origin from philosophy, psychology, and education. The purpose of qualitative research is to understand the people's everyday life experiences and reduce it into the central meaning or the 'essence of the experience'.[ 21 , 22 ] The unit of analysis of phenomenology is the individuals who have had similar experiences of the phenomenon. Interviews with individuals are mainly considered for the data collection, though, documents and observations are also useful. Data analysis includes identification of significant meaning elements, textural description (what was experienced), structural description (how was it experienced), and description of 'essence' of experience.[ 1 , 7 , 21 ] The phenomenological approach is further divided into descriptive and interpretive phenomenology. Descriptive phenomenology focuses on the understanding of the essence of experiences and is best suited in situations that need to describe the lived phenomenon. Hermeneutic phenomenology or Interpretive phenomenology moves beyond the description to uncover the meanings that are not explicitly evident. The researcher tries to interpret the phenomenon, based on their judgment rather than just describing it.[ 7 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]

Example: A phenomenological study conducted by Cornelio et al . aimed at describing the lived experiences of mothers in parenting children with leukemia. Data from ten mothers were collected using in-depth semi-structured interviews and were analyzed using Husserl's method of phenomenology. Themes such as “pivotal moment in life”, “the experience of being with a seriously ill child”, “having to keep distance with the relatives”, “overcoming the financial and social commitments”, “responding to challenges”, “experience of faith as being key to survival”, “health concerns of the present and future”, and “optimism” were derived. The researchers reported the essence of the study as “chronic illness such as leukemia in children results in a negative impact on the child and on the mother.” [ 25 ]

Grounded Theory Research

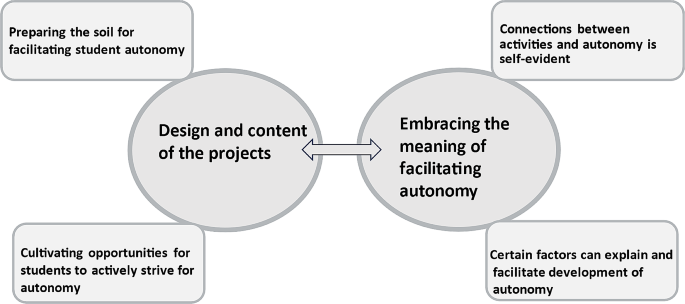

Grounded theory has its base in sociology and propagated by two sociologists, Barney Glaser, and Anselm Strauss.[ 26 ] The primary purpose of grounded theory is to discover or generate theory in the context of the social process being studied. The major difference between grounded theory and other approaches lies in its emphasis on theory generation and development. The name grounded theory comes from its ability to induce a theory grounded in the reality of study participants.[ 7 , 27 ] Data collection in grounded theory research involves recording interviews from many individuals until data saturation. Constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling, theoretical coding, and theoretical saturation are unique features of grounded theory research.[ 26 , 27 , 28 ] Data analysis includes analyzing data through 'open coding,' 'axial coding,' and 'selective coding.'[ 1 , 7 ] Open coding is the first level of abstraction, and it refers to the creation of a broad initial range of categories, axial coding is the procedure of understanding connections between the open codes, whereas selective coding relates to the process of connecting the axial codes to formulate a theory.[ 1 , 7 ] Results of the grounded theory analysis are supplemented with a visual representation of major constructs usually in the form of flow charts or framework diagrams. Quotations from the participants are used in a supportive capacity to substantiate the findings. Strauss and Corbin highlights that “the value of the grounded theory lies not only in its ability to generate a theory but also to ground that theory in the data.”[ 27 ]

Example: Williams et al . conducted a grounded theory research to explore the nature of relationship between the sense of self and the eating disorders. Data were collected form 11 women with a lifetime history of Anorexia Nervosa and were analyzed using the grounded theory methodology. Analysis led to the development of a theoretical framework on the nature of the relationship between the self and Anorexia Nervosa. [ 29 ]

Ethnographic research

Ethnography has its base in anthropology, where the anthropologists used it for understanding the culture-specific knowledge and behaviors. In health sciences research, ethnography focuses on narrating and interpreting the health behaviors of a culture-sharing group. 'Culture-sharing group' in an ethnography represents any 'group of people who share common meanings, customs or experiences.' In health research, it could be a group of physicians working in rural care, a group of medical students, or it could be a group of patients who receive home-based rehabilitation. To understand the cultural patterns, researchers primarily observe the individuals or group of individuals for a prolonged period of time.[ 1 , 7 , 30 ] The scope of ethnography can be broad or narrow depending on the aim. The study of more general cultural groups is termed as macro-ethnography, whereas micro-ethnography focuses on more narrowly defined cultures. Ethnography is usually conducted in a single setting. Ethnographers collect data using a variety of methods such as observation, interviews, audio-video records, and document reviews. A written report includes a detailed description of the culture sharing group with emic and etic perspectives. When the researcher reports the views of the participants it is called emic perspectives and when the researcher reports his or her views about the culture, the term is called etic.[ 7 ]

Example: The aim of the ethnographic study by LeBaron et al . was to explore the barriers to opioid availability and cancer pain management in India. The researchers collected data from fifty-nine participants using in-depth semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and document review. The researchers identified significant barriers by open coding and thematic analysis of the formal interview. [ 31 ]

Historical research

Historical research is the “systematic collection, critical evaluation, and interpretation of historical evidence”.[ 1 ] The purpose of historical research is to gain insights from the past and involves interpreting past events in the light of the present. The data for historical research are usually collected from primary and secondary sources. The primary source mainly includes diaries, first hand information, and writings. The secondary sources are textbooks, newspapers, second or third-hand accounts of historical events and medical/legal documents. The data gathered from these various sources are synthesized and reported as biographical narratives or developmental perspectives in chronological order. The ideas are interpreted in terms of the historical context and significance. The written report describes 'what happened', 'how it happened', 'why it happened', and its significance and implications to current clinical practice.[ 1 , 10 ]

Example: Lubold (2019) analyzed the breastfeeding trends in three countries (Sweden, Ireland, and the United States) using a historical qualitative method. Through analysis of historical data, the researcher found that strong family policies, adherence to international recommendations and adoption of baby-friendly hospital initiative could greatly enhance the breastfeeding rates. [ 32 ]

Case study research

Case study research focuses on the description and in-depth analysis of the case(s) or issues illustrated by the case(s). The design has its origin from psychology, law, and medicine. Case studies are best suited for the understanding of case(s), thus reducing the unit of analysis into studying an event, a program, an activity or an illness. Observations, one to one interviews, artifacts, and documents are used for collecting the data, and the analysis is done through the description of the case. From this, themes and cross-case themes are derived. A written case study report includes a detailed description of one or more cases.[ 7 , 10 ]

Example: Perceptions of poststroke sexuality in a woman of childbearing age was explored using a qualitative case study approach by Beal and Millenbrunch. Semi structured interview was conducted with a 36- year mother of two children with a history of Acute ischemic stroke. The data were analyzed using an inductive approach. The authors concluded that “stroke during childbearing years may affect a woman's perception of herself as a sexual being and her ability to carry out gender roles”. [ 33 ]

Sampling in Qualitative Research

Qualitative researchers widely use non-probability sampling techniques such as purposive sampling, convenience sampling, quota sampling, snowball sampling, homogeneous sampling, maximum variation sampling, extreme (deviant) case sampling, typical case sampling, and intensity sampling. The selection of a sampling technique depends on the nature and needs of the study.[ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ] The four widely used sampling techniques are convenience sampling, purposive sampling, snowball sampling, and intensity sampling.

Convenience sampling

It is otherwise called accidental sampling, where the researchers collect data from the subjects who are selected based on accessibility, geographical proximity, ease, speed, and or low cost.[ 34 ] Convenience sampling offers a significant benefit of convenience but often accompanies the issues of sample representation.

Purposive sampling

Purposive or purposeful sampling is a widely used sampling technique.[ 35 ] It involves identifying a population based on already established sampling criteria and then selecting subjects who fulfill that criteria to increase the credibility. However, choosing information-rich cases is the key to determine the power and logic of purposive sampling in a qualitative study.[ 1 ]

Snowball sampling

The method is also known as 'chain referral sampling' or 'network sampling.' The sampling starts by having a few initial participants, and the researcher relies on these early participants to identify additional study participants. It is best adopted when the researcher wishes to study the stigmatized group, or in cases, where findings of participants are likely to be difficult by ordinary means. Respondent ridden sampling is an improvised version of snowball sampling used to find out the participant from a hard-to-find or hard-to-study population.[ 37 , 38 ]

Intensity sampling

The process of identifying information-rich cases that manifest the phenomenon of interest is referred to as intensity sampling. It requires prior information, and considerable judgment about the phenomenon of interest and the researcher should do some preliminary investigations to determine the nature of the variation. Intensity sampling will be done once the researcher identifies the variation across the cases (extreme, average and intense) and picks the intense cases from them.[ 40 ]

Deciding the Sample Size

A-priori sample size calculation is not undertaken in the case of qualitative research. Researchers collect the data from as many participants as possible until they reach the point of data saturation. Data saturation or the point of redundancy is the stage where the researcher no longer sees or hears any new information. Data saturation gives the idea that the researcher has captured all possible information about the phenomenon of interest. Since no further information is being uncovered as redundancy is achieved, at this point the data collection can be stopped. The objective here is to get an overall picture of the chronicle of the phenomenon under the study rather than generalization.[ 1 , 7 , 41 ]

Data Collection in Qualitative Research

The various strategies used for data collection in qualitative research includes in-depth interviews (individual or group), focus group discussions (FGDs), participant observation, narrative life history, document analysis, audio materials, videos or video footage, text analysis, and simple observation. Among all these, the three popular methods are the FGDs, one to one in-depth interviews and the participant observation.

FGDs are useful in eliciting data from a group of individuals. They are normally built around a specific topic and are considered as the best approach to gather data on an entire range of responses to a topic.[ 42 Group size in an FGD ranges from 6 to 12. Depending upon the nature of participants, FGDs could be homogeneous or heterogeneous.[ 1 , 14 ] One to one in-depth interviews are best suited to obtain individuals' life histories, lived experiences, perceptions, and views, particularly while exporting topics of sensitive nature. In-depth interviews can be structured, unstructured, or semi-structured. However, semi-structured interviews are widely used in qualitative research. Participant observations are suitable for gathering data regarding naturally occurring behaviors.[ 1 ]

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

Various strategies are employed by researchers to analyze data in qualitative research. Data analytic strategies differ according to the type of inquiry. A general content analysis approach is described herewith. Data analysis begins by transcription of the interview data. The researcher carefully reads data and gets a sense of the whole. Once the researcher is familiarized with the data, the researcher strives to identify small meaning units called the 'codes.' The codes are then grouped based on their shared concepts to form the primary categories. Based on the relationship between the primary categories, they are then clustered into secondary categories. The next step involves the identification of themes and interpretation to make meaning out of data. In the results section of the manuscript, the researcher describes the key findings/themes that emerged. The themes can be supported by participants' quotes. The analytical framework used should be explained in sufficient detail, and the analytic framework must be well referenced. The study findings are usually represented in a schematic form for better conceptualization.[ 1 , 7 ] Even though the overall analytical process remains the same across different qualitative designs, each design such as phenomenology, ethnography, and grounded theory has design specific analytical procedures, the details of which are out of the scope of this article.

Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS)

Until recently, qualitative analysis was done either manually or with the help of a spreadsheet application. Currently, there are various software programs available which aid researchers to manage qualitative data. CAQDAS is basically data management tools and cannot analyze the qualitative data as it lacks the ability to think, reflect, and conceptualize. Nonetheless, CAQDAS helps researchers to manage, shape, and make sense of unstructured information. Open Code, MAXQDA, NVivo, Atlas.ti, and Hyper Research are some of the widely used qualitative data analysis software.[ 14 , 43 ]

Reporting Guidelines

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) is the widely used reporting guideline for qualitative research. This 32-item checklist assists researchers in reporting all the major aspects related to the study. The three major domains of COREQ are the 'research team and reflexivity', 'study design', and 'analysis and findings'.[ 44 , 45 ]

Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Research

Various scales are available to critical appraisal of qualitative research. The widely used one is the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Checklist developed by CASP network, UK. This 10-item checklist evaluates the quality of the study under areas such as aims, methodology, research design, ethical considerations, data collection, data analysis, and findings.[ 46 ]

Ethical Issues in Qualitative Research

A qualitative study must be undertaken by grounding it in the principles of bioethics such as beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice. Protecting the participants is of utmost importance, and the greatest care has to be taken while collecting data from a vulnerable research population. The researcher must respect individuals, families, and communities and must make sure that the participants are not identifiable by their quotations that the researchers include when publishing the data. Consent for audio/video recordings must be obtained. Approval to be in FGDs must be obtained from the participants. Researchers must ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of the transcripts/audio-video records/photographs/other data collected as a part of the study. The researchers must confirm their role as advocates and proceed in the best interest of all participants.[ 42 , 47 , 48 ]

Rigor in Qualitative Research

The demonstration of rigor or quality in the conduct of the study is essential for every research method. However, the criteria used to evaluate the rigor of quantitative studies are not be appropriate for qualitative methods. Lincoln and Guba (1985) first outlined the criteria for evaluating the qualitative research often referred to as “standards of trustworthiness of qualitative research”.[ 49 ] The four components of the criteria are credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Credibility refers to confidence in the 'truth value' of the data and its interpretation. It is used to establish that the findings are true, credible and believable. Credibility is similar to the internal validity in quantitative research.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] The second criterion to establish the trustworthiness of the qualitative research is transferability, Transferability refers to the degree to which the qualitative results are applicability to other settings, population or contexts. This is analogous to the external validity in quantitative research.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Lincoln and Guba recommend authors provide enough details so that the users will be able to evaluate the applicability of data in other contexts.[ 49 ] The criterion of dependability refers to the assumption of repeatability or replicability of the study findings and is similar to that of reliability in quantitative research. The dependability question is 'Whether the study findings be repeated of the study is replicated with the same (similar) cohort of participants, data coders, and context?'[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Confirmability, the fourth criteria is analogous to the objectivity of the study and refers the degree to which the study findings could be confirmed or corroborated by others. To ensure confirmability the data should directly reflect the participants' experiences and not the bias, motivations, or imaginations of the inquirer.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Qualitative researchers should ensure that the study is conducted with enough rigor and should report the measures undertaken to enhance the trustworthiness of the study.

Conclusions

Qualitative research studies are being widely acknowledged and recognized in health care practice. This overview illustrates various qualitative methods and shows how these methods can be used to generate evidence that informs clinical practice. Qualitative research helps to understand the patterns of health behaviors, describe illness experiences, design health interventions, and develop healthcare theories. The ultimate strength of the qualitative research approach lies in the richness of the data and the descriptions and depth of exploration it makes. Hence, qualitative methods are considered as the most humanistic and person-centered way of discovering and uncovering thoughts and actions of human beings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

729k Accesses

294 Citations

84 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

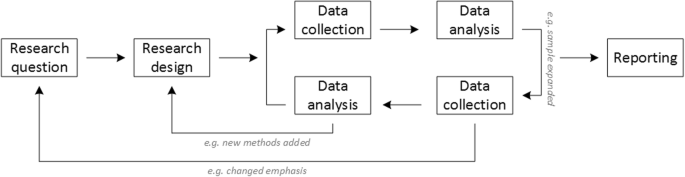

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

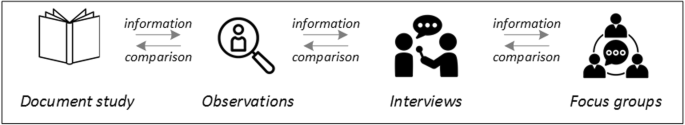

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

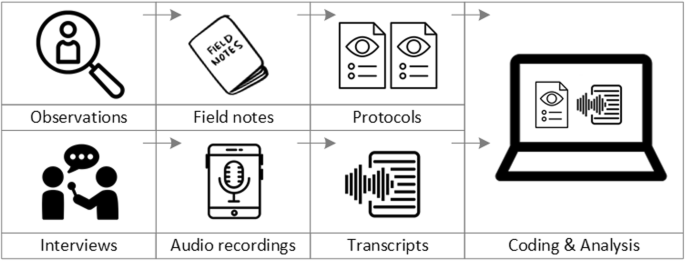

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

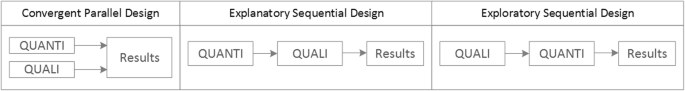

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8 , 117.

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Observation methods in qualitative research] (pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36 , 717–732.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks: Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49 (4), 283–287.

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, M. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [The half-open interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Jansen, H. (2007). Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Systematics and implementation of the qualitative survey (pp. 27–41). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Pv, R., & Peremans, L. (2007). Exploreren met focusgroepgesprekken: de ‘stem’ van de groep onder de loep. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Exploring with focus group conversations: the “voice” of the group under the magnifying glass (pp. 53–64). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41 (5), 545–547.

Boeije H: Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen, [Analysis in qualitative research: Thinking and doing] vol. Den Haag Boom Lemma uitgevers; 2012.

Hunter, A., & Brewer, J. (2015). Designing Multimethod Research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 185–205). London: Oxford University Press.

Archibald, M. M., Radil, A. I., Zhang, X., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14 (2), 5–33.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research . Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320 (7226), 50–52.

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52 (4), 1893–1907.

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24 (1), 9–18.

Marlett, N., Shklarov, S., Marshall, D., Santana, M. J., & Wasylak, T. (2015). Building new roles and relationships in research: A model of patient engagement research. Quality of Life Research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 24 (5), 1057–1067.

Demian, M. N., Lam, N. N., Mac-Way, F., Sapir-Pichhadze, R., & Fernandez, N. (2017). Opportunities for engaging patients in kidney research. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 4 , 2054358117703070–2054358117703070.

Noyes, J., McLaughlin, L., Morgan, K., Roberts, A., Stephens, M., Bourne, J., Houlston, M., Houlston, J., Thomas, S., Rhys, R. G., et al. (2019). Designing a co-productive study to overcome known methodological challenges in organ donation research with bereaved family members. Health Expectations . 22(4):824–35.

Piil, K., Jarden, M., & Pii, K. H. (2019). Research agenda for life-threatening cancer. European Journal Cancer Care (Engl), 28 (1), e12935.

Hofmann, D., Ibrahim, F., Rose, D., Scott, D. L., Cope, A., Wykes, T., & Lempp, H. (2015). Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 18 (5), 995–1008.

Jun, M., Manns, B., Laupacis, A., Manns, L., Rehal, B., Crowe, S., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2015). Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 2 , 35.

Elsie Baker, S., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? In National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper . National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf .

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18 (2), 179–183.

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., & Kingstone, T. (2018). Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21 (5), 619–634.

Download references

Acknowledgements

no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LB drafted the manuscript; WW and CG revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final versions.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Loraine Busetto .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Busetto, L., Wick, W. & Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2 , 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Download citation

Received : 30 January 2020

Accepted : 22 April 2020

Published : 27 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Mixed methods

- Quality assessment

Neurological Research and Practice

ISSN: 2524-3489

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 55, Issue 2

- Understanding qualitative research in health care

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

Qualitative studies are often used to research phenomena that are difficult to quantify numerically. 1,2 These may include concepts, feelings, opinions, interpretations and meanings, or why people behave in a certain way. Although qualitative research is often described in opposition to quantitative research, the approaches are complementary, and many researchers use mixed methods in their projects, combining the strengths of both approaches. 2 Many comprehensive texts exist on qualitative research methodology including those with a focus on healthcare related research. 2-4 Here we give a brief introduction to the rationale, methods and quality assessment of qualitative research.

https://doi.org/10.1136/dtb.2017.2.0457

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Key issues in qualitative research

Qualitative research allows deeper understanding of the richness and complexity of social phenomena. Qualitative methods can provide evidence on health and illness and can be used in various ways: 3

To complement quantitative methods, or when quantitative methods are impractical (e.g. when the topic is sensitive, poses measurement problems or is concerned with process and/or interaction; the research population is very small; or for intensive understanding of an innovation before widespread introduction). 3

In the exploratory stages of an applied health research programme, when they may clarify the research question and generate hypotheses. 3 Study design is often described as flexible or ‘emergent’ and researchers may have to adapt a study through a process of ‘progressive focussing’ in response to important but unanticipated findings. 3

To assess a pre-specified hypothesis, as in quantitative research. 3