Research Medical Center

Kansas City, MO

High Performing

Patient experience.

Medical Surgical ICU

Cardiac ICU

Bariatric/Weight Control Services

Addiction Treatment Services

Onsite Emergency Department

Doctors at Research Medical Center

U.S. News has extensive information in each doctor's profile to help you find the best one for you.

Amel T. Abbas PA

Palm Springs, CA

Physician Assistant

General Neurosurgery PA

Elise A. Abicht MD

Leawood, KS

Obstetrics & Gynecology

General Obstetrics & Gynecology

Joel D. Ackerman MD

Lake Lotawana, MO

Anesthesiology

Pain Medicine

Hameed Ahmad MD

General Nephrology

Iftekhar Ahmed MD

General Neurology

Kelly R. Alford MD

Syed M. Ali MD

Family Medicine

Hospital Medicine/Hospitalist

Hamza Alshami MD

Pulmonology

Critical Care Medicine, Sleep Medicine

Kavitha K. Arabindoo MD

General Family Medicine

Alexandr V. Arakelov MD

Robert Ardinger MD

Bainbridge Island, WA

Pediatric Cardiology

General Pediatric Cardiology

Oluyomi Asojo MD

Hematopathology, Anatomic Pathology, Clinical Pathology

Robert M. Beatty MD

Overland Park, KS

Neurosurgery

General Neurosurgery

Revathi N. Bhat MD

Geriatric Medicine

General Geriatrics

Daniel K. Bixler MD

Emergency Medicine

General Emergency Medicine

Timothy L. Blackburn MD

Cardiac Electrophysiology

Margo L. Block DO

Kansas City, KS

Neurophysiology

Stephen A. Bloom MD

Echocardiography, Nuclear Cardiology, Cardiothoracic Imaging, Non-Invasive Cardiology

David B. Bock MD

General Urology

Karen A. Bordson DO

Lincoln, NE

Find a Doctor

Quality rankings & ratings.

To help patients decide where to receive care, U.S. News generates hospital rankings by evaluating data on nearly 5,000 hospitals. To be nationally ranked in a specialty, a hospital must excel in caring for the sickest, most medically complex patients.

Adult Rankings

Procedures and Conditions Related to Cancer

Cardiology, Heart & Vascular Surgery

Procedures and Conditions Related to Cardiology, Heart & Vascular Surgery

Diabetes & Endocrinology

Procedures and Conditions Related to Diabetes & Endocrinology

Gastroenterology & GI Surgery

Procedures and Conditions Related to Gastroenterology & GI Surgery

Procedures and Conditions Related to Nephrology

Neurology & Neurosurgery

Procedures and Conditions Related to Neurology & Neurosurgery

Procedures and Conditions Related to Obstetrics & Gynecology

Orthopedics

Procedures and Conditions Related to Orthopedics

Pulmonology & Lung Surgery

Procedures and Conditions Related to Pulmonology & Lung Surgery

Rehabilitation

Procedures and Conditions Related to Urology

Nearby Hospitals

AD Children's Mercy Kansas City Hospital

Kansas City , MO

5.4 miles away

St. Luke's Hospital of Kansas City

# 2 in Kansas City

3.3 miles away

University of Kansas Hospital

# 1 in Kansas City

Kansas City , KS

4.2 miles away

Kansas City VA Medical Center

4.3 miles away

St. Joseph Medical Center-Kansas City

Center for behavioral medicine.

University Health-Truman Medical Center

5.5 miles away

MidAmerica Rehabilitation Hospital

Shawnee Mission , KS

6.5 miles away

Kansas City Orthopaedic Institute

Leawood , KS

6.7 miles away

Scores are based on surveys taken from this hospital’s inpatients after they were discharged inquiring about different aspects of their stay. The scores are not used in the Best Hospitals rankings.

Satisfaction with the hospital overall

How the patient felt about their hospital stay and discharge overall.

Willingness to recommend

Willingness of patients to recommend this hospital to others.

Satisfaction with doctors’ communications

How patients rated physicians in listening and explaining in a way that patients could understand.

Satisfaction with nurses’ communications

How patients rated nurses in listening and explaining in a way that patients could understand.

Satisfaction with efforts to prevent medication harm

How well medications, how they were to be taken, and side effects were explained before they were administered.

Satisfaction with quality of discharge information

How well staff reviewed adequacy of help at home and provided enough information in writing about symptoms and problems to watch for.

Satisfaction with involvement in recovery

How well patients’ wishes were considered in discharge planning and how well patients understood when they left how to care for themselves, what medications they will take and why.

Satisfaction with staff responsiveness

How promptly help was provided when needed or requested.

Satisfaction with hospital room cleanliness

How patients rated the cleanliness of their hospital room and bathroom.

Satisfaction with noise volume

How well patients rated the quietness of their hospital experience.

See all 10 Categories

Health equity.

Health equity is the absence of unjust and avoidable differences among groups of people, regardless of social, economic, or demographic identification. U.S. News evaluates hospital performance in health equity by analyzing data on various dimensions of equity for historically underserved patients.

Racial Disparities in Outcomes New

How successful the hospital is in enabling Black patients to live at home during their first 30 days of recovery, compared to White patients at that hospital. Recovery at home, rather than at a hospital or nursing home, is preferred by most patients and families.

Days at home after knee replacement, hip replacement, or back surgery (spinal fusion)

Days at home after aortic valve replacement, transcatheter aortic valve replacement, or heart bypass surgery.

Too few patients to be rated

Charity Care

How well hospital spending on free and discounted care for uninsured patients aligns with the proportion of uninsured in the surrounding community.

Charity care provision for uninsured patients

Higher than other hospitals

Community Residents Who Accessed Care at this Hospital New

How well the surrounding community is represented in the population treated by the hospital.

Representation of low-income patients

Similar to other hospitals

Breakdown by Race & Ethnicity

The percentage of patients treated by the hospital for elective procedures compared to the community. County and state percentages were not included in the calculation of hospital scores.

Representation of non-white patients

Comparable to or higher than the community

Demographics

Representation of Black patients

Representation of asian american and pacific islander patients.

Insufficient data

Representation of Hispanic patients

Representation of native american patients.

Certain data used for the health equity analysis was provided by CareJourney and the Dartmouth Atlas Data website.

Elements of the Racial Disparities in Outcomes and Breakdown by Race & Ethnicity measures were developed by CareJourney using data accessed securely through the CMS Virtual Research Data Center (VRDC).

The data set forth at certain elements of the Community Residents Who Accessed Care at This Hospital and Charity Care portions of this Health Equity section were obtained from the Dartmouth Atlas Data website, which was funded by the...

Contact & Location

Hospital Location

2316 East Meyer Boulevard, Kansas City, MO, 64132-1136

Affiliated Hospital

Frequently Asked Questions

Where is research medical center located, what do patients say about research medical center , how can i find a doctor at research medical center , how does research medical center perform in health equity, what is a u.s. news best hospital, health disclaimer », disclaimer and a note about your health », you may also like, find a primary care doctor near you.

Payton Sy April 18, 2024

Routine Health Screenings Everyone Needs

Elaine K. Howley April 17, 2024

The Horrors of TMJ

KFF Health News April 11, 2024

Time Blindness ADHD Productivity Tools

Claire Wolters April 11, 2024

Knee Arthritis

Barbara Sadick April 10, 2024

Medicare Mistakes

Elaine Hinzey April 9, 2024

Dementia Care: Tips for Home Caregivers

Elaine K. Howley April 5, 2024

How to Find a Primary Care Doctor

Vanessa Caceres April 5, 2024

Symptoms of a Kidney Problem

Claire Wolters April 4, 2024

Allergies vs. Colds

Payton Sy April 4, 2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Planet Money

- Planet Money Podcast

- The Indicator Podcast

- Planet Money Newsletter Archive

- Planet Money Summer School

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Could the U.S. force treatment on mentally ill people (again)?

Greg Rosalsky

One of the most difficult and expensive questions that a society faces is how to care for those who cannot care for themselves, and how to pay for it. Over the last century, the United States has radically changed how it answers this question when it comes to treating people with severe mental illnesses. Now we appear to be on the brink of another major change.

In the mid-to-late 20th century, America closed most of the country's mental hospitals. The policy has come to be known as deinstitutionalization. Today, it's increasingly blamed for the tragedy that thousands of mentally ill people sleep on our city streets. Wherever you may stand in that debate, the reform began with good intentions and arguably could have gone much differently with more funding.

In October 1963, just weeks before he was assassinated, President John F. Kennedy signed into law landmark legislation that aimed to transform mental healthcare in the United States.

For decades, the United States had locked away people deemed to be mentally ill in asylums. At their height, in 1955, these state-run psychiatric hospitals institutionalized a staggering 558,922 Americans .

Investigative journalists , government officials, and heartbreaking books like 1962's One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest exposed Americans to the horrors of the asylum system and sparked a movement for reform. Meanwhile, new pharmaceuticals like chlorpromazine (also known as Thorazine) burst onto the scene, holding the promise to treat people with mental afflictions without the need for around-the-clock supervision. The asylum system was a massive cost to taxpayers, which helped reformers unite with fiscal conservatives to build a coalition for change.

For President Kennedy, the movement to reform mental healthcare was personal. His younger sister, Rosemary Kennedy, had been born with intellectual disabilities — and her treatment is illustrative of some of the horrors of the asylum era. Kennedy's parents had spent years sending Rosemary to special clinics and allowing doctors to subject her to experiments, like injecting her full of hormones as an adolescent. In 1941, surgeons convinced the Kennedy patriarch, Joseph Kennedy, of the need for a newfangled medical procedure: a lobotomy. The procedure involved cutting out part of Rosemary's brain.

Rosemary's surgery went terribly wrong (even for a lobotomy, which is now a medically suspect and extremely rare procedure). The surgeons removed too much of her frontal lobe. In an instant Rosemary became completely disabled, losing the ability to talk, walk, and control her bodily functions. Fearing embarrassment for his ambitious family, Joe Kennedy had his daughter institutionalized — and he kept his family and the public in the dark about what had really happened to her. It wasn't until 1958 when then-Senator John Kennedy tracked down his sister and secretly paid her a visit. He was shocked by what he found.

Like his sister, Eunice Kennedy Shriver, who would go on to found the Special Olympics, President Kennedy was inspired by his sister to fight for a better future for people with mental disabilities. And so, in 1963, he signed into law the Community Mental Health Act. The bill provided funding for research into mental disabilities and, more importantly, sought to dismantle the sprawling asylum system. It was the last bill Kennedy would sign into law.

"Under this legislation, custodial mental institutions will be replaced by therapeutic centers," President Kennedy said when he signed the bill into law. "It should be possible, within a decade of two, to reduce the number of patients in mental institutions by 50% or more." In fact, due to this law and other policy changes, by the 2000s, the number of people in asylums would end up plummeting over 90% .

Meanwhile, supporters of civil rights for mentally ill folks won a string of victories in state legislatures and the courts that made it harder to detain and medicate people against their will.

Rather than locking them away in state-run psychiatric hospitals, Kennedy and other reformers hoped to give people with mental illnesses the freedom to live in their communities and receive care from local organizations. However, the Community Mental Health Act failed to provide enough funding for the 1,500 community health centers that lawmakers had initially envisioned. Congress left much of the funding to the states, and, ultimately, only about half of the health centers ended up being built and those that did end up getting created were largely underfunded .

Both in the 1960s as governor of California and in the 1980s as president, Ronald Reagan was an important figure in cutting funding to community health centers. But this was only one part of a broader — and bipartisan — set of actions and inactions that have led to collective neglect for this vulnerable population. One reason may be that people with mental disabilities aren't exactly a powerful voting bloc.

Today, many of those who would historically be institutionalized in asylums are now instead incarcerated in jail, cycling in and out of emergency rooms , and living on the streets. Nowhere is this more clear than the city of Los Angeles, which has a swelling population of homeless people, many of whom suffer from mental illness.

In a new book titled Sons, Daughters, and Sidewalk Psychotics , UC San Diego sociologist Neil Gong grapples with the system of mental healthcare that Los Angeles has adopted in the wake of the closure of asylums.

"With hindsight, the triumph of deinstitutionalization looks more like a tragic irony: an unlikely coalition of civil libertarian liberals and fiscal conservatives pushed for the destruction of an abusive and neglectful system that had nonetheless housed, fed, and organized the lives of over half a million people," Gong writes.

A Crisis Within A Crisis

As we've covered before in this newsletter , research suggests that the homelessness crisis in states like California is primarily a story about housing supply and demand. There's not enough housing for folks who need it. Most of the people facing homelessness are not mentally ill.

However, mental illness is a huge predictor of who becomes homeless — and especially of who stays homeless for a long time. Research estimates that over 20% of Americans experiencing homelessness — and a larger percentage of those experiencing long-term homelessness — suffer from severe mental illnesses.

Gong calls the approach that cities like Los Angeles have taken to this problem "tolerant containment." Basically, the city tolerates things like encampments, bizarre behavior in public, and drug use as long as it's contained in segregated areas that are mostly out of sight of the majority of city residents.

Whether you're a progressive or conservative, especially in California, it's pretty universally accepted that this status quo is not working. It's both inhumane and also surprisingly expensive. Letting this at-risk population languish on the streets imposes a whole bunch of downstream taxpayer costs like repeat emergency room visits , police work, crisis care, and incarceration — none of which measurably improve the long-term outcomes for this population. The question is: what should we do now?

Many progressives have advocated for a "housing first" solution to the problem of homelessness. Basically, they argue, instead of focusing on getting this at-risk population psychiatric help or rehab, the priority should be getting them into stable housing first and then focusing on providing other services. However, Gong suggests, in Los Angeles and other cities, too often the focus has become what you might call housing only. "Because these public or nonprofit providers are under-resourced and understaffed, it kind of ends there," Gong says. This policy sometimes can be effective, he says, but sometimes it means "abandoning people to self-destruct."

A randomized controlled trial conducted in Santa Clara, California, found that providing chronically homeless folks with permanent housing and voluntary supportive services had an 86% success rate in terms of keeping them from returning to living on the streets. This and similar findings by other studies have been hailed by advocates as a slam-dunk validation for the housing first approach to tackling homelessness. But, Gong says, it also suggests there's still a sizable population — the remaining 14 percent — that need more than just housing and access to what's currently available to them for services. In a state like California, which has a massive population of chronically unhoused people, an 86% success rate suggests there would still be thousands of people living on the streets.

"I do believe that if we are able to deliver the kind of community-based services that were promised 60 years ago, we could whittle that number down," Gong says.

However, Gong acknowledges that, even with permanent housing and better quality social and psychiatric services, there would still be some small percentage of folks who would still wind up living on the streets. And for those folks the government, he argues, may need to impose "more assertive or coerced treatment, including even, in some cases, longer-term in-patient care." In other words, a modern, more humane version of a mental asylum or something similar.

For this population who gets forced treatment, Gong stresses, we really need to be careful. He cites research that this sort of compulsory care can be really traumatizing for patients and even result in a greater risk of suicide. "So one thing we really need to figure out how to do is to make the small amount of forced treatment that we might need better."

Reinstitutionalization

We're now at a crossroads where there's a bipartisan movement for what you might call reinstitutionalization. We're not going back to the horrors of lobotomies and forced sterilizations of the asylum era, but a growing number of Democrats and Republicans claim that it's now necessary to use greater force to require treatment for mentally ill folks in the quest to end homelessness.

New York City mayor Eric Adams has for the last couple years pursued a pilot program that gives the police and medical workers the power to involuntarily hospitalize the mentally ill.

Late last year, former president Donald Trump posted a video on his campaign website, remarking , "When I am back in the White House, we will use every tool, lever, and authority to get the homeless off our streets." He continued: "And for those who are severely mentally ill and deeply disturbed, we will bring them back to mental institutions, where they belong... with the goal of reintegrating them back into society once they are well enough to manage."

Recently, California voters narrowly passed Proposition 1, which was championed by Governor Gavin Newsom. Groups like the ACLU opposed this ballot measure on the grounds that it would strip funds from community health organizations and "primarily fund forced treatment and institutionalization."

Neil Gong admits he's fearful that the pendulum is swinging back to a more draconian and less humane approach to how we treat the mentally ill. "I definitely worry that we're going to move to this kind of heavy-handed, lock-people-up, get-them-outta-sight-in-the-cheapest-way-possible approach," Gong says. But, he says, with so much apparent political will to do something about the problem, he maintains hope we can build a better future for some of the most vulnerable people in our society.

- Rosemary Kennedy

- deinstitutionalization

- John Kennedy

Skip to content

Read the latest news stories about Mailman faculty, research, and events.

Departments

We integrate an innovative skills-based curriculum, research collaborations, and hands-on field experience to prepare students.

Learn more about our research centers, which focus on critical issues in public health.

Our Faculty

Meet the faculty of the Mailman School of Public Health.

Become a Student

Life and community, how to apply.

Learn how to apply to the Mailman School of Public Health.

SPIRIT Initiative Takes Aim at the U.S. Mental Health Crisis

The state of mental health in the United States is not good. The last 15 years have seen unprecedented increases in depression and anxiety, especially among young people. Rates of fatal suicide are also on the rise, particularly among older adults. A new Columbia Mailman School initiative called SPIRIT (Social Psychiatry: Innovation in Research, Implementation, and Training) aims to catalyze public health research collaborations to better understand the mental health crisis and identify solutions.

Katherine Keyes, SPIRIT’s director

“It is not an overstatement or alarmist to say we’re in a mental health crisis, and this crisis is not something we can treat out way out of. We really need to refocus on root causes, including social determinants of health,” says Katherine Keyes , professor of epidemiology, who directs SPIRIT. “What we need to do as a school of public health and university is design research, implementation, and solutions to these growing problems.”

Already, SPIRIT has more than 50 participating faculty bringing extensive expertise in mental health research, both from within Columbia Mailman and from the larger Columbia Irving Medical Center and other departments across campus. Research teams will look to uncover the factors giving rise to mental illness, such as the emotional stress of climate change, social media and other new technologies, as well as what is driving poor outcomes in populations like Black and LGBT+ communities. Other efforts will examine how brain development, stress response, plus how loneliness and lack of connection each play a role. Researchers will also examine possible solutions. These include school- and community-based prevention programs, economic and social policy, crisis support, and stigma reduction. SPIRIT offers pilot funding and mentoring.

SPIRIT comes from a long tradition of mental health research at Columbia Mailman dating back to the early 1970s and the establishment of the Psychiatric Epidemiology Training Program , which is currently led by Keyes. The emphasis is social psychiatry, covering the political, interpersonal, and cultural dimensions of psychiatric disorders, distress, and mental well-being. In 2022, the School launched GMH@Mailman (Global and Population Mental Health) as a hub for research on the social determinants of mental health and developing and implementing interventions.

Over the last year, Keyes and colleagues have published research on rising rates of depression and anxiety, psychological distress, and suicidal behaviors, especially among girls ; groups at elevated risk for suicide attempts from bullying victimization ; and rising rates of suicide among Black women . Ongoing projects are exploring topics such as the mental health needs of Afghani refugees in the U.S. and the impact of social media on youth mental health, both positive and negative .

Beyond a simple nexus for research collaborations, SPIRIT is taking the role of community-builder. True to its name, the initiative seeks to focus on and engender mental wellness, which in the words of Keyes translates to “finding joy and building spirit, both at our School and as a community.”

For years, Keyes has hosted a book club for her doctoral students. As part of SPIRIT, there is now a similar forum for books exploring mental health through a social determinants lens. The current selection is When Crack Was Kin g, which is about the role of drug policy in promoting inequality told through stories of people who survived the crack epidemic. Its author, Donovan X. Ramsey, will join John Pamplin , assistant professor of epidemiology, in conversation on May 9. Separately, a speaker series will host academics specializing in various aspects of mental health research.

SPIRIT is open for all comers. Keyes believes mental health and wellness is a topic we can all relate to and contribute to. “Everyone has been touched by mental health,” she says. “This is a time when all of us need to come together and invest in solutions that make a difference.”

Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior

Faculty research centers.

Our faculty research centers foster new knowledge across the spectrum of mental health disorders.

Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence

Members of the Brown Psychiatry and Human Behavior faculty lead three state-of-the-art biomedical and behavioral research centers, strengthening our research infrastructure here at the university and across the state of Rhode Island.

STAR COBRE for Stress, Trauma, and Resilience

Cobre center for sleep and circadian rhythms in child and adolescent mental health, cobre center for neuromodulation.

Brown Psychiatry and Human Behavior faculty lead research centers across Rhode Island, solving basic and translational questions about mental health in adolescence and adulthood.

Bradley Hasbro Children's Research Center

Brown center for the study of children at risk, brown-lifespan center for digital health, butler hospital behavioral medicine and addictions research, butler hospital memory and aging program, center for alzheimer's disease research, center for behavioral and preventive medicine, center for neurorestoration and neurotechnology, consortium for research innovation in suicide prevention, pediatric anxiety research center, providence/boston center for aids research, vista clinical research group, the weight control and diabetes research center.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Addressing Risks to Advance Mental Health Research

Ana s. iltis.

Director, Center for Bioethics, Health and Society, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Wake Forest University

Sahana Misra

Mental Health and Clinical Neurosciences Division, Portland VA Medical Center, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Oregon Health and Science University

Laura B. Dunn

Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Director of Psycho-Oncology, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco

Gregory K. Brown

Research Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology in Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Amy Campbell

Assistant Professor, Center for Bioethics and Humanities, Upstate Medical University and Syracuse University College of Law (courtesy)

Sarah A. Earll

Co-Director, Saint Louis Empowerment

Anne Glowinski

Professor, Psychiatry (Child), Director, Education and Training in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Whitney B. Hadley

Graduate Student, Falk College for Sports and Human Dynamics, Syracuse University

Ronald Pies

Professor of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine, Lecturer in Bioethics & Humanities, SUNY Upstate Medical University

James M. DuBois

Hubert Mäder Chair of Health Care Ethics at Saint Louis University, Adjunct Professor of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine

Risk communication and management are essential to the ethical conduct of research, yet addressing risks may be time consuming for investigators and institutional review boards (IRBs) may reject study designs that appear too risky. This can discourage needed research, particularly in higher risk protocols or those enrolling potentially vulnerable individuals, such as those with some level of suicidality. Improved mechanisms for addressing research risks may facilitate much needed psychiatric research. This article provides mental health researchers with practical approaches to: 1) identify and define various intrinsic research risks; 2) communicate these risks to others (e.g., potential participants, regulatory bodies, society); 3) manage these risks during the course of a study; and 4) justify the risks.

As part of a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded scientific meeting series, a public conference and a closed-session expert panel meeting were held on managing and disclosing risks in mental health clinical trials. The expert panel reviewed the literature with a focus on empirical studies and developed recommendations for best practices and further research on managing and disclosing risks in mental health clinical trials. IRB review was not required because there were no human subjects. The NIMH played no role in developing or reviewing the manuscript.

Challenges, current data, practical strategies, and topics for future research are addressed for each of four key areas pertaining to management and disclosure of risks in clinical trials: identifying and defining risks, communicating risks, managing risks during studies, and justifying research risks.

Conclusions

Empirical data on risk communication, managing risks, and the benefits of research can support the ethical conduct of mental health research and may help investigators better conceptualize and confront risks and to gain IRB approval.

Introduction

With 26.2% of U.S. adults afflicted with a psychiatric disorder, improvements in psychiatric treatments are needed. 1 Despite advances for psychiatric disorders there has been increased public scrutiny over how mental health research is conducted and the risks to participants, particularly in the wake of concerns regarding non-published data on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and suicide, 2 , 3 studies on schizophrenia in which medication is withheld, 4 and increased litigation. 5 Researchers must proactively address risks—from minimizing risks inherent to study design (e.g., placebo controlled studies), to mitigating potential participant misunderstanding of the research purpose, to addressing risks of worsening symptoms during research participation (e.g., emergence of suicidal ideation or psychosis). Yet there are not always readily apparent means of addressing risks, particularly when those risks may be inherent in the overall research endeavor or associated with the illness itself, not the research. Institutional review boards (IRBs) and sponsors may halt or delay studies over concerns about participant risks. Increased investigator burdens because of real and perceived risks may discourage much-needed research. For example, suicide is clearly associated with a history of depression and is the most serious potential outcome of depression, but only 10% of clinical trials examining SSRI efficacy between 1984 and 2001 included individuals with some level of suicidality. No SSRI efficacy trials in actively suicidal subjects currently exist. 6 Because the presence of suicidal ideation is a typical exclusion criterion in research, the community is left with ‘evidence-based’ guidance that is generalized to these excluded individuals. This pattern of exclusion has resulted in a dearth of evidence regarding treatment for individuals with varying degrees of suicidality. To facilitate research in this area, suicide should be treated as a negative outcome comparable to negative outcomes of other diseases - an undesirable yet to-be expected event. 7 , 8 To ignore this is to continue the unwarranted and unjust exclusion of these individuals.

Mental health researchers must strive to design ethical and scientifically sound research that does not ignore populations or kinds of research merely because of the difficulties involved. If mental health researchers continue to allow risks to discourage research, certain groups that could benefit from research will continue to be harmed by being understudied. Groups perceived as “high risk” deserve scientifically rigorous study as well. Researchers must be able to identify and communicate risks and potential benefits of this research to the public and regulatory bodies, demonstrate that they will manage risks effectively, and provide strong ethical justification for such research.

This article provides mental health researchers with practical approaches to: 1) identify and define various intrinsic research risks; 2) communicate risks to others (e.g., potential participants, regulatory bodies, society); 3) manage risks during the course of a study; and 4) justify the risks. These recommendations are the result of a systematic literature review, a public conference during which authors participated as speakers or panelists, a closed-door working session that included all of the authors, and subsequent email and phone conversations to formulate consensus recommendations. All authors participated in the writing and editing process.

I. Defining and Identifying Risks

A. challenges in defining risk in research.

The Belmont Report provides the ethical framework for U.S. research regulations and identifies five primary forms of harm relevant to research review and oversight. 9 These are summarized in Table 1 .

The Kinds of Harms Identified in the Belmont Report

In addition to recognizing the types of harms that study participation may pose, investigators and regulatory bodies must determine studies’ overall risk level. While risk is an inherent aspect of human life and familiar to all, it is difficult to define operationally. Most regulatory and philosophical definitions of risk include three primary concepts: the probability and magnitude of harm . However, there is no agreed upon formula for determining risk level. The Common Rule recognizes two risk categories for adult research: ‘minimal’ and ‘greater than minimal.’ Minimal risk is “the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the research are not greater in and of themselves than those ordinarily encountered in daily life or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examinations or tests”. 10 Whose daily life and which examinations are routine are not specified and instead left to IRB judgment. The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) identifies three categories of risk for research involving children—minimal risk, greater than minimal risk with prospect of direct benefit, minor increase over minimal risk with no direct benefit. Studies that do not fit these categories require special federal review. 10

In order to foresee and address research risks, investigators must identify the types, probability and magnitude of harm their study poses and describe risk information in protocols and informed consent discussions and forms clearly. Regulatory bodies, such as IRBs, ultimately define the study risks relevant to review and determine whether the “[r]isks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects, and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result”. 10 However, guidance about defining and evaluating risks and benefits is limited and often focused on determining the extent to which additional protections are needed for studies deemed to be higher risk. Researchers may educate IRB members about study risks, including a comparison of research risks across different types of studies, when they have data that might inform IRB determinations.

B. Research Summary: State of the Field

There is no consensus on how best to evaluate and rate research risk levels, and IRBs are inconsistent in how they evaluate risk. Shah et al found significant variability among IRB chairs’ rating of risk level. 11 Similar studies of IRB practices have demonstrated inconsistencies in rating protocols as eligible for expedited review versus requiring full review, a determination based largely on assessment of risk level since expedited studies must be minimal risk. 12 – 14 This variability results in uneven participant protections and delays in start date for funded research. 14 & 15 These issues are magnified in large-scale multi-site studies, which can provide greater statistical power with more meaningful and generalizable outcomes yet require review by multiple IRBs. 14

Despite data indicating that mental health research is as safe as most other medical research and that participants typically possess capacity to consent for themselves, 16 – 21 mental health researchers may find that IRBs, which are not required to and may not have members with substantive expertise in mental health research, 10 judge their studies as posing higher risks than comparably risky non-mental health studies and believe that potential participants are less likely to be able to understand risks and given informed consent. 22 , 23

C. Tips for the Savvy Researcher

Strategies for appropriately identifying research risks are summarized in Table 2 and include:

- Identify and define risks early in study development. The Research Protocol Ethics Assessment Tool (RePEAT), developed by Roberts, 24 essentially is a checklist thatcovers multiple ethical domains, including scientific merit of the protocol; risks and benefits; expertise, commitment and integrity of the research team; informed consent and decisional capacity issues; incentives for participation; confidentiality. Researchers can apply the RePEAT (or variations of it) to their protocols to ensure that ethically important research elements are proactively addressed.

- Study proposals should explicitly identify and address foreseen potential risks; how these risks will be communicated to potential participants; and how emerging risks will be managed, depending on risk level, once the study begins, including, but not limited to, the use of data and safety monitoring board or external monitors. Section II explores strategies for communicating and managing risks.

- To conduct research with groups that IRBs often exclude due to their “vulnerability,” mental health investigators may need to work harder than other investigators to document for IRBs evidence of research risks and of the decisional abilities of potential participants (who are likely to otherwise be perceived as “vulnerable”) to understand risk information and provide informed consent. For example, researchers may collaborate with community advisory boards, review the literature, and conduct focus groups to support inclusion.

D. Further Research Needed to Advance the Field

A better understanding of participant and IRB views and decision-making regarding risk would assist researchers in designing studies. Future research should aim to identify and understand the risks that matter most to potential participants, including understanding their concerns about privacy violations, legal risks, social harms at the individual level, and the burdens of participating in studies. Finally, more research on how IRBs evaluate risk, perceive institutional risk, compare risks and potential benefits, and make decisions could help investigators explain studies better when applying for IRB approval. Such research might also identify areas for IRB education. For example, one study compared IRB member judgments of consent capacity of potential participants in oncology, chronic pain, and major depressive disorder research studies. Persons with major depressive disorder were judged as having significantly less consent capacity than those with non-mental health diagnoses even when IRB members were told of the high incidence of depression as a comorbidity in oncology and chronic pain patients. IRB members also judged the psychiatric study as posing greater legal risk to the institution than the other studies. 22 , 23 If these apparently inconsistent analyses of capacity and risk by IRBs are typical, it would be appropriate to develop educational interventions to help IRBs develop new strategies for evaluating studies. Knowing whether there is a significant difference between perceived and actual institutional risk might help facilitate research. Future research needs are summarized in Table 3 .

Research Needs

Note: In answering research questions about the views and assessments of participants or populations of potential participants, it is important to attend to individual differences.

II. Communicating Risks with Research Participants

A. importance of communicating risks.

The regulatory 10 and ethical 9 obligation to obtain informed consent from research participants (or their legally authorized representatives) requires effective risk communication. 25 Risk communication is an information sharing process in which investigators disclose research risks and benefits in language potential participants can understand and elicit their need for additional information, and participants understand and appreciate the information relevant to their research participation decision.

Numerous factors can impede effective risk communication for research participants. Individuals with certain mental health conditions may face additional barriers, some of which can be overcome with appropriate interventions. 26 – 30 Many barriers identified here are exacerbated by heavy reliance on informed consent forms as the primary means for disclosing risks and on potential participants’ spontaneously asking for further information or clarification.

- Volume and Quality of Information. Risk information has five dimensions: identity, permanence, timing, probability and value/seriousness. 31 Effective risk communication requires disclosure, understanding, and appreciation of all five dimensions. Providing too much information at once, however, particularly without categorizing it or distinguishing between less and more significant and probable risks, impedes effective risk communication. Informed consent documents that incorporate required information from different sources can become long and difficult to read. 32 Risk communication involves both objective, factual information and subjective information whose relevance depends on individual values, goals and priorities. There may be a tendency to approach this process with a more legalistic/formalistic vision, whereby disclosure is seen as a standardized process without attention to the specific information particular participants might need and value. 33

- Poor Numeracy. Adults with average cognitive capacities do not always understand and use basic mathematical and statistical concepts well. 34 , 35 Understanding and appreciating risks requires a conceptual understanding of probability and basic mathematical skills. Poor numeracy interferes with this ability. If the person disclosing risk information does not understand these concepts well, disclosure may be inadequate.

- Cognitive Biases. Tversky and Kahneman 36 , 37 and others have identified ways in which cognitive biases affect the understanding and interpretation of numerical information. Cognitive biases include framing (information about the chance of a risk materializing and not materializing is understood differently); compression (small risks appear greater than they are and large risks appear smaller); availability (culturally significant or otherwise well-known risks are overestimated); anchoring (risks are estimated relative to a familiar risk) and comparison bias (risk perception changes when given comparative risk information). 38 , 39

- Poor Literacy and Health Literacy. Poor health literacy is well-documented in the U.S. 40 and can interfere with understanding and appreciating research risk information. Risk information often is communicated in writing. Given the estimated number of functionally illiterate (40 million) and marginally literate (50 million) adults in the US, 41 written communication may be unreliable, particularly when written at a high reading level, as often is the case with research consent documents. 42 , 43 Poor literacy may pose special concerns in psychiatric research because adults with certain disorders may read several grades below their educational level. 43 – 46

- Poor Retention and Recall of Information and Working Memory Limitations. The decision to participate in a study is a series of decisions to enroll and remain in a study. Individuals must be able to recall information about the study, including risk information, to make these decisions. Individuals often have difficulty retaining and recalling risk information. 47 – 49 Working memory limitations also can impede understanding and appreciation of risk information, which requires processing and manipulating significant amounts of information simultaneously. This poses special concern for potential participants with mental health conditions that adversely affect working memory, such as schizophrenia, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other forms of dementia.

- The Subjectivity of Risk Information. Risk evaluation is value laden, and individuals may evaluate the same risks differently. Knowing which risks individuals would want disclosed can improve risk communication. This envisions a more subjective standard of disclosure over a purely formalistic approach (akin to an “information dump”), as discussed in clinical decision-making. 50

- Poor Communication Regarding Research Benefits. Potential participants must not only understand and appreciate research risks but evaluate them in light of the potential benefits of participation. Exaggerating risks, using vague information regarding benefits, or allowing potential participants to think that research participation poses greater personal benefit than it does can impede effective risk communication. 51

Existing research suggests that specific practices can foster effective risk communication. These are summarized in Table 2 and include:

- Use plain language (see www.plainlanguage.gov ).

- Use interactive informed consent processes that can foster decisional capacity, including understanding and appreciation of risks, among people with different learning styles and capacities. 27 , 30 , 50 , 52 – 54

- Use graphs, charts or other means of presenting information, particularly numerical information, to promote understanding among people with different learning styles and capacities. 55 – 57

- Assess capacity not only to determine whether a person is ready to give valid informed consent but because specific processes designed to assess capacity involve educational interventions that can foster understanding and appreciation. 58 – 60

- Avoid unnecessary vagueness and provide necessary information regarding research risks and benefits, distinguishing between probable and remote. 51 , 57 , 61 – 63

- Review research information periodically to address retention and recall. 61

There are few studies on risk communication involving actual participants or people contemplating enrollment in a real study. Studies about participation in hypothetical trials may not fully generalize to real-world decision-making contexts.

As summarized in Table 3 , for each barrier identified, additional research is needed to better understand the nature of the barrier and identify cost-effective mechanisms that can overcome it. There also remain important normative questions, such as what level of understanding and appreciation among potential participants is necessary for valid informed consent. 64

III. Managing Risks

A. definition and importance of managing risks.

High-risk studies are essential to improving knowledge of psychiatric disorders and effective treatment. Effective risk management during these studies is critical. IRBs, however, may pay little attention to the investigator’s obligation to minimize risks 65 and either disapprove studies perceived as higher risk or approve studies with insufficient risk management plans. This makes it particularly important for mental health researchers to provide evidence based risk information and propose appropriate risk management plans when seeking IRB approval. Studies may be considered “high risk” because of the novel nature of the intervention; the study population is deemed high risk; the study targets risky behavior, e.g., suicidality or psychosis; or the study targets disorders where risky behaviors are features of the illnesses, e.g., depression or bipolar disorder. Automatic exclusion of “high risk” participants or removal of participants exhibiting risky behavior limits generalizability. 66 Risk management strategies instead focus on trying to initiate and maintain study participation in a safe manner.

Data safety and monitoring boards (DSMBs) may monitor studies, though they can be costly and there has been controversy about their independence from study sponsors. A July 2010 New England Journal of Medicine editorial proposed that DSMBs should be chosen and convened “under the aegis of an independent public body, such as…the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health…” and stated that they will be examining the independence of DSMBs for future manuscript submissions when appropriate. 67

For longitudinal studies in populations at risk for fluctuating levels of decisional abilities, there is concern about diminishing capacity and the possibility of subjects being unable to protect their interests if new risks arise during a study. Use of third-party participant advocates who ensure that a research participant’s interests remain protected during the course of a long term study should the participant exhibit diminished capacity may help researchers to allow individuals to remain in a study despite fluctuating or diminishing decisional capacity without adding significant costs. For example, the large-scale, 18-month-plus, Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Schizophrenia trial examining long-term outcomes used such advocates. 68 At time of enrollment, participants designated an advocate. While advocates participated in the initial informed consent discussions, all participants had capacity to give consent. Advocates received training to determine whether the risk/benefit ratio acknowledged by the participant at time of enrollment had changed ‘substantially and adversely,’ thus no longer reflecting the participant’s expressed interests. If so, participants were withdrawn. However if the risk/benefit ratio was not substantially altered, then the advocate could permit the participant to continue participation. Stroup and colleagues surveyed research personnel and a subset of participants and advocates when participants left or completed the study. A majority in all groups favorably viewed the advocate process. Twelve percent of sampled participants believed the process negatively impacted their autonomy. 69

Managing risk during a study may also involve altering standard study designs to address safety concerns and accounting for these changes in data analysis. 70 , 71 Consider the NIMH-funded randomized-controlled PROSPECT study (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly–Collaborative Trial). 72 PROSPECT randomly assigned depression health specialists in primary care clinics (the study intervention) and measured depression and suicidal ideation rates in elderly primary care patients. These outcomes were compared with those in clinics that were assigned to an enhanced treatment as usual (TAU). Individuals with suicidal ideation were not excluded from participation and rates of suicidal ideation were examined over time. Unlike a true TAU clinical setting, all participants assigned to TAU received enhanced care in the form of increased psychiatric surveillance (screening and assessment). This enhanced TAU design created potential study limitations, but it was necessary for study design purposes (to initially identify cases and evaluate at follow-up study visits) and to meet stringent standards of assuring participants’ safety. 73 Similar designs with high risk participants have been used in other clinical trials 74 , 75 and support to the notion that such approaches facilitate important research that otherwise would be constrained.

Training research staff how to assess and manage risks and anxiety-provoking situations (e.g., using role play) has been shown to be effective. 76 , 77

Investigators may implement a number of strategies to manage research risks. Three principal strategies are:

- Researcher ethics consultations. Such consultations involve interaction between researchers and other stakeholders in the research enterprise and one or more individuals knowledgeable about the ethical considerations in research, regarding an ethical question related to any aspect of planning, conducting, interpreting, or disseminating results of research related to human health and well being. The purpose of the interaction is to provide information; identify, analyze, and/or deliberate about ethical issues; and recommend a course of action.” 79 , p. 3 McCormick et al reported that psychiatric researchers were more likely than other researchers to find such services useful. 78

- Plan for ongoing research staff training regarding the use of management plans and ways of responding to different situations. The principal investigator or a qualified co-investigator should be readily available to research staff during the study.

- Identify situations that necessitate a written risk management plan. Such plans may include tools such as checklists for easy and systematic implementation of specific plan elements. Studies examining specific risky behavior require explicit procedures that include frequent assessment and crisis intervention when needed. For example, if investigators anticipate psychiatric emergencies, the plan should address how these will be handled, who will be involved and how, and to what extent confidentiality will be protected. Management plans may include a protocol for handling dropouts from the study and for obtaining follow-up information or for maintaining an up-to-date list of multiple ways to contact participants. Risk management plans should clearly delineate the roles of research team members and the relationship between researchers and clinicians in managing safety. These plans should be detailed in the protocol, and elements relevant to participant rights or willingness to participate should be disclosed during the informed consent process.

Further research to create evidence-based risk management plans and train investigators on risk management is needed. This is especially important given the need for more research in high risks areas such as suicide. Research to develop empirically based guidance about risk management in mental health research would benefit researchers and regulatory bodies alike. This research agenda should include further examination of the specific types of risky situations necessitating intervention and the specific interventions that are effective; the roles and responsibilities of researchers, clinicians and clinician-researchers with respect to risk management; and the perspectives of participants, families and regulatory bodies about the use of risk management strategies in research that carries greater than minimal risk.

IV. Justifying Risks

The Belmont Report and current regulations consistently require that risks be evaluated in light of potential benefits to participants and society; research that is scientifically invalid or otherwise lacks value is unethical insofar as it wastes resources and unnecessarily exposes subjects to risk. 64 , 80 Protecting the scientific validity of a study requires management of conflicts of interest that have the potential to bias the conduct or reporting of a study. 81 Trust in psychiatric research has been harmed by reports of investigators who conducted research of questionable validity with inadequately disclosed and unmanaged conflicts of interest. 82

One frequently heard criticism of mental health research is that, despite years of research, the field has made few significant advances. 83 However, at least two federally-sponsored studies have shown that available treatments for psychiatric disorders are comparable in efficacy to treatments in other medical specialties 84 , 85 The lack of research on some types of patients may explain the lack of progress in some areas. Moreover, the development of beneficial treatments is often extremely complex, involving false starts, competing interests, and stigma. These factors are illustrated well in the research history of Lithium, which has been proved effective as both an acute and maintenance treatment 86 , 87 in bipolar disorder, and is FDA-approved for these indications. Several studies show that lithium significantly reduces rates of suicide. 88 , 89 Yet despite sixty years of clinical use, lithium has not been systematically and thoroughly studied in either pediatric 90 or geriatric 91 populations. Furthermore, there have been few controlled studies of lithium in “dual diagnosis” populations, e.g., patients with both bipolar disorder and substance abuse/dependence. 92 Ironically, suicide rates are highest in elderly populations, with affective illness a potent risk factor, 93 suggesting that the potential benefit of research in this population is reasonable relative to the risks. Similarly, “dual diagnosis” status (bipolar/substance use disorder) is associated with poor prognosis and treatment resistance. 92 , 94 Thus, two populations at significant risk for morbidity and mortality are understudied with respect to lithium treatment. Reluctance to undertake research in these groups may stem from legitimate concerns regarding lithium’s side effects and potential toxicity; 95 however, other factors may be at work. For example, unlike many anticonvulsants and “atypical” antipsychotics, lithium receives little marketing support from pharmaceutical companies. 96 The role of stigma surrounding lithium must also be considered. One non-professional website observes that, “Lithium…conjures up images of zombies, and everyone seems to think that it zaps your brainpower. While some users do end up feeling this way, the majority do not.” 97 Clearly, if IRB members, researchers, or potential subjects buy into the “zombie” myth, research on lithium is likely to be impeded—notwithstanding a World Health Organization study estimating that lithium treatment saved over $145 billion in hospitalization costs in the U.S. between 1970 and 1994. 98

It is also important to determine which benefits matter most to participants and when and why they matter most. Some data suggest that the interests of researchers and funding agencies do not always align with those of participants, the primary stakeholders in mental health research. For example, mental health consumers tend to prioritize more than researchers a focus on alternative treatment modalities (such as nutritional or self-help modalities), iatrogenic harms, and qualitative research. 99 , 100

The ethical conduct of research requires investigators to identify, communicate and manage risks effectively. Investigators’ efforts to identify and communicate research risks and potential benefits clearly, demonstrate knowledge of participants’ perceptions of risks and the kinds of potential harms that most concern them, document potential participants’ capacity to give informed consent, and develop plans to monitor risks during the study and identify new risks may help researchers improve their studies and collaborations with IRBs. For individual investigators, providing IRBs with tables that explain risk information and clear management plans may be useful. Continued research is required to advance researchers’ and IRBs’ understanding of how best to identify, define, effectively communicate, and manage risks. Such efforts are essential to facilitating much needed mental health research.

Strategies for the Savvy Researcher

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Mental Health (grant 1R13MH079690) and the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science (grant UL1 TR000448). Dr. Dunn reports serving as a Consultant in 2012 to Lilly, Inc.

Contributor Information

Ana S. Iltis, Director, Center for Bioethics, Health and Society, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Wake Forest University.

Sahana Misra, Mental Health and Clinical Neurosciences Division, Portland VA Medical Center, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Oregon Health and Science University.

Laura B. Dunn, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Director of Psycho-Oncology, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco.

Gregory K. Brown, Research Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology in Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Amy Campbell, Assistant Professor, Center for Bioethics and Humanities, Upstate Medical University and Syracuse University College of Law (courtesy)

Sarah A. Earll, Co-Director, Saint Louis Empowerment.

Anne Glowinski, Professor, Psychiatry (Child), Director, Education and Training in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Whitney B. Hadley, Graduate Student, Falk College for Sports and Human Dynamics, Syracuse University.

Ronald Pies, Professor of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine, Lecturer in Bioethics & Humanities, SUNY Upstate Medical University.

James M. DuBois, Hubert Mäder Chair of Health Care Ethics at Saint Louis University, Adjunct Professor of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine.

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- About the Director

- Advisory Boards and Groups

- Strategic Plan

- Offices and Divisions

- Careers at NIMH

- Staff Directories

- Getting to NIMH

Research Centers

This program supports the centers mechanisms (P20, P30) and other institutional infrastructure grants in support of large-scale services trials and effectiveness studies in all areas of Branch programmatic responsibility.

Areas of Emphasis

- To develop a sound knowledge base to substantially increase the sustainable uptake of scientifically based treatments and services for mental disorders across diverse community settings.

- To identify and utilize active therapeutic ingredients in complex community-based services and programs for applications that optimize functioning and sustain community reintegration of people with mental disorders.

- To understand how and which traits of individuals, their families, providers, organizations, and social and cultural environments affect whether, where, and when people will seek care, the types of care chosen/provided, what happens during care, and the impact on outcomes.

- To enhance the research capacity and infrastructure for mental health services research through strategic partnerships, community engagement, and information technologies.

Agnes Rupp, Ph.D. Acting Branch Chief 6001 Executive Boulevard, Room 7146, MSC 9631 301-443-3364, [email protected]

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What the data says about abortion in the U.S.

Pew Research Center has conducted many surveys about abortion over the years, providing a lens into Americans’ views on whether the procedure should be legal, among a host of other questions.

In a Center survey conducted nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision that ended the constitutional right to abortion , 62% of U.S. adults said the practice should be legal in all or most cases, while 36% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Another survey conducted a few months before the decision showed that relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the issue .

Find answers to common questions about abortion in America, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, which have tracked these patterns for several decades:

How many abortions are there in the U.S. each year?

How has the number of abortions in the u.s. changed over time, what is the abortion rate among women in the u.s. how has it changed over time, what are the most common types of abortion, how many abortion providers are there in the u.s., and how has that number changed, what percentage of abortions are for women who live in a different state from the abortion provider, what are the demographics of women who have had abortions, when during pregnancy do most abortions occur, how often are there medical complications from abortion.

This compilation of data on abortion in the United States draws mainly from two sources: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, both of which have regularly compiled national abortion data for approximately half a century, and which collect their data in different ways.

The CDC data that is highlighted in this post comes from the agency’s “abortion surveillance” reports, which have been published annually since 1974 (and which have included data from 1969). Its figures from 1973 through 1996 include data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and New York City – 52 “reporting areas” in all. Since 1997, the CDC’s totals have lacked data from some states (most notably California) for the years that those states did not report data to the agency. The four reporting areas that did not submit data to the CDC in 2021 – California, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey – accounted for approximately 25% of all legal induced abortions in the U.S. in 2020, according to Guttmacher’s data. Most states, though, do have data in the reports, and the figures for the vast majority of them came from each state’s central health agency, while for some states, the figures came from hospitals and other medical facilities.

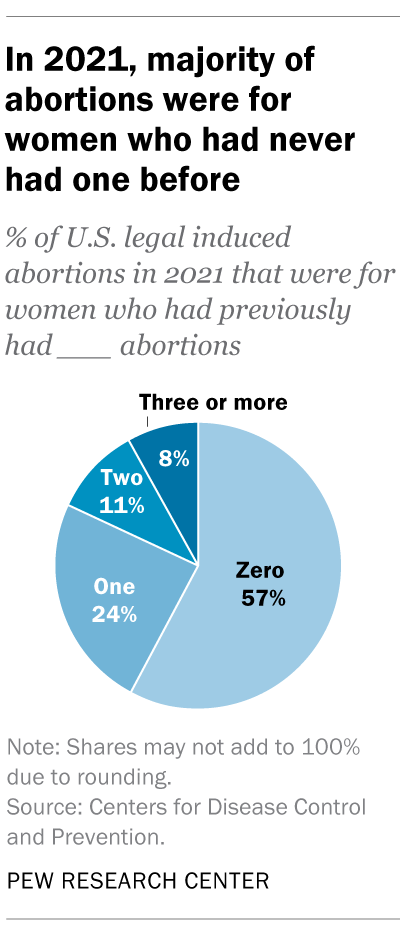

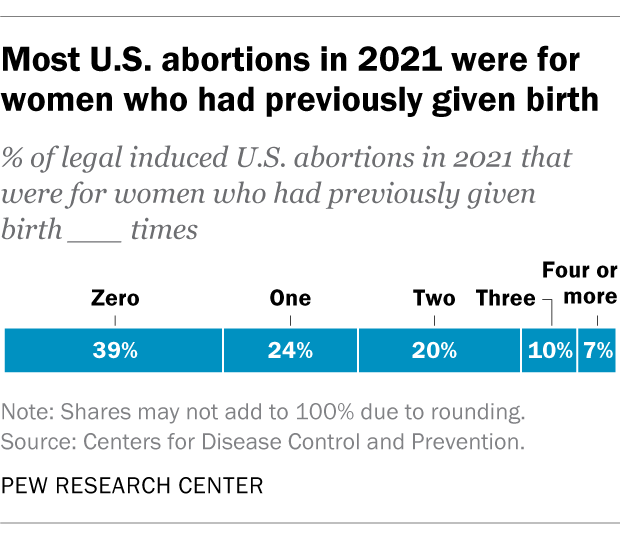

Discussion of CDC abortion data involving women’s state of residence, marital status, race, ethnicity, age, abortion history and the number of previous live births excludes the low share of abortions where that information was not supplied. Read the methodology for the CDC’s latest abortion surveillance report , which includes data from 2021, for more details. Previous reports can be found at stacks.cdc.gov by entering “abortion surveillance” into the search box.

For the numbers of deaths caused by induced abortions in 1963 and 1965, this analysis looks at reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. In computing those figures, we excluded abortions listed in the report under the categories “spontaneous or unspecified” or as “other.” (“Spontaneous abortion” is another way of referring to miscarriages.)

Guttmacher data in this post comes from national surveys of abortion providers that Guttmacher has conducted 19 times since 1973. Guttmacher compiles its figures after contacting every known provider of abortions – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, and it provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond to its inquiries. (In 2020, the last year for which it has released data on the number of abortions in the U.S., it used estimates for 12% of abortions.) For most of the 2000s, Guttmacher has conducted these national surveys every three years, each time getting abortion data for the prior two years. For each interim year, Guttmacher has calculated estimates based on trends from its own figures and from other data.

The latest full summary of Guttmacher data came in the institute’s report titled “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2020.” It includes figures for 2020 and 2019 and estimates for 2018. The report includes a methods section.

In addition, this post uses data from StatPearls, an online health care resource, on complications from abortion.

An exact answer is hard to come by. The CDC and the Guttmacher Institute have each tried to measure this for around half a century, but they use different methods and publish different figures.

The last year for which the CDC reported a yearly national total for abortions is 2021. It found there were 625,978 abortions in the District of Columbia and the 46 states with available data that year, up from 597,355 in those states and D.C. in 2020. The corresponding figure for 2019 was 607,720.

The last year for which Guttmacher reported a yearly national total was 2020. It said there were 930,160 abortions that year in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with 916,460 in 2019.

- How the CDC gets its data: It compiles figures that are voluntarily reported by states’ central health agencies, including separate figures for New York City and the District of Columbia. Its latest totals do not include figures from California, Maryland, New Hampshire or New Jersey, which did not report data to the CDC. ( Read the methodology from the latest CDC report .)

- How Guttmacher gets its data: It compiles its figures after contacting every known abortion provider – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, then provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond. Guttmacher’s figures are higher than the CDC’s in part because they include data (and in some instances, estimates) from all 50 states. ( Read the institute’s latest full report and methodology .)

While the Guttmacher Institute supports abortion rights, its empirical data on abortions in the U.S. has been widely cited by groups and publications across the political spectrum, including by a number of those that disagree with its positions .

These estimates from Guttmacher and the CDC are results of multiyear efforts to collect data on abortion across the U.S. Last year, Guttmacher also began publishing less precise estimates every few months , based on a much smaller sample of providers.

The figures reported by these organizations include only legal induced abortions conducted by clinics, hospitals or physicians’ offices, or those that make use of abortion pills dispensed from certified facilities such as clinics or physicians’ offices. They do not account for the use of abortion pills that were obtained outside of clinical settings .

(Back to top)

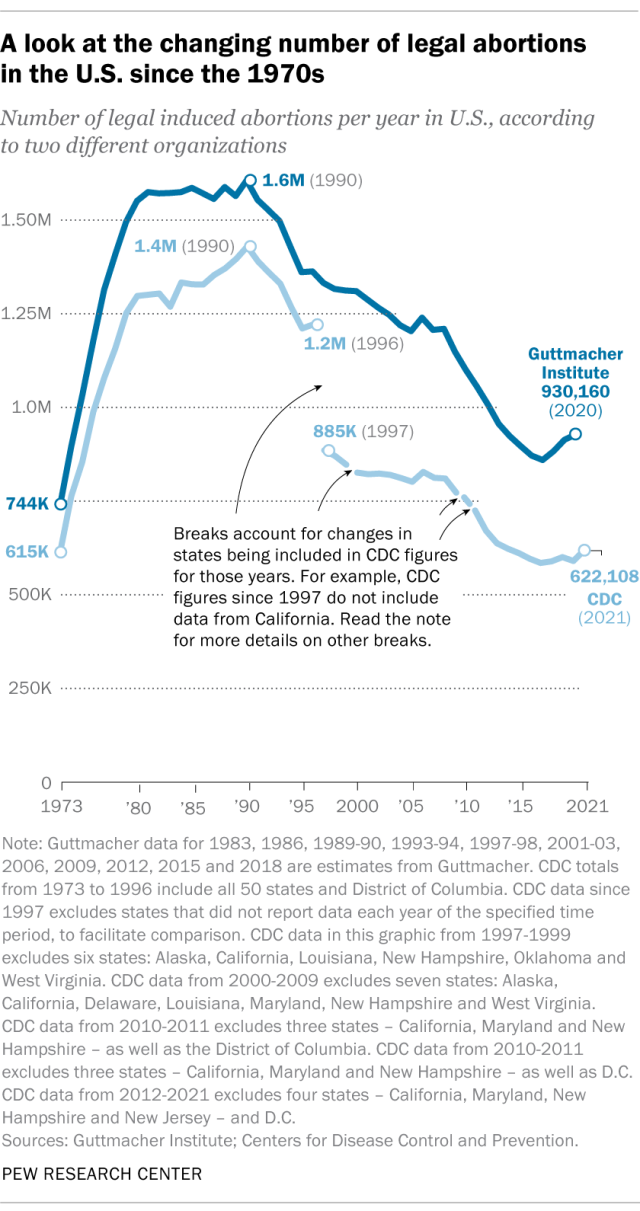

The annual number of U.S. abortions rose for years after Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure in 1973, reaching its highest levels around the late 1980s and early 1990s, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. Since then, abortions have generally decreased at what a CDC analysis called “a slow yet steady pace.”

Guttmacher says the number of abortions occurring in the U.S. in 2020 was 40% lower than it was in 1991. According to the CDC, the number was 36% lower in 2021 than in 1991, looking just at the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported both of those years.

(The corresponding line graph shows the long-term trend in the number of legal abortions reported by both organizations. To allow for consistent comparisons over time, the CDC figures in the chart have been adjusted to ensure that the same states are counted from one year to the next. Using that approach, the CDC figure for 2021 is 622,108 legal abortions.)

There have been occasional breaks in this long-term pattern of decline – during the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, and then again in the late 2010s. The CDC reported modest 1% and 2% increases in abortions in 2018 and 2019, and then, after a 2% decrease in 2020, a 5% increase in 2021. Guttmacher reported an 8% increase over the three-year period from 2017 to 2020.

As noted above, these figures do not include abortions that use pills obtained outside of clinical settings.

Guttmacher says that in 2020 there were 14.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. Its data shows that the rate of abortions among women has generally been declining in the U.S. since 1981, when it reported there were 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women in that age range.

The CDC says that in 2021, there were 11.6 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. (That figure excludes data from California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.) Like Guttmacher’s data, the CDC’s figures also suggest a general decline in the abortion rate over time. In 1980, when the CDC reported on all 50 states and D.C., it said there were 25 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44.

That said, both Guttmacher and the CDC say there were slight increases in the rate of abortions during the late 2010s and early 2020s. Guttmacher says the abortion rate per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 rose from 13.5 in 2017 to 14.4 in 2020. The CDC says it rose from 11.2 per 1,000 in 2017 to 11.4 in 2019, before falling back to 11.1 in 2020 and then rising again to 11.6 in 2021. (The CDC’s figures for those years exclude data from California, D.C., Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.)

The CDC broadly divides abortions into two categories: surgical abortions and medication abortions, which involve pills. Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved abortion pills in 2000, their use has increased over time as a share of abortions nationally, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher.

The majority of abortions in the U.S. now involve pills, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. The CDC says 56% of U.S. abortions in 2021 involved pills, up from 53% in 2020 and 44% in 2019. Its figures for 2021 include the District of Columbia and 44 states that provided this data; its figures for 2020 include D.C. and 44 states (though not all of the same states as in 2021), and its figures for 2019 include D.C. and 45 states.

Guttmacher, which measures this every three years, says 53% of U.S. abortions involved pills in 2020, up from 39% in 2017.

Two pills commonly used together for medication abortions are mifepristone, which, taken first, blocks hormones that support a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which then causes the uterus to empty. According to the FDA, medication abortions are safe until 10 weeks into pregnancy.

Surgical abortions conducted during the first trimester of pregnancy typically use a suction process, while the relatively few surgical abortions that occur during the second trimester of a pregnancy typically use a process called dilation and evacuation, according to the UCLA School of Medicine.

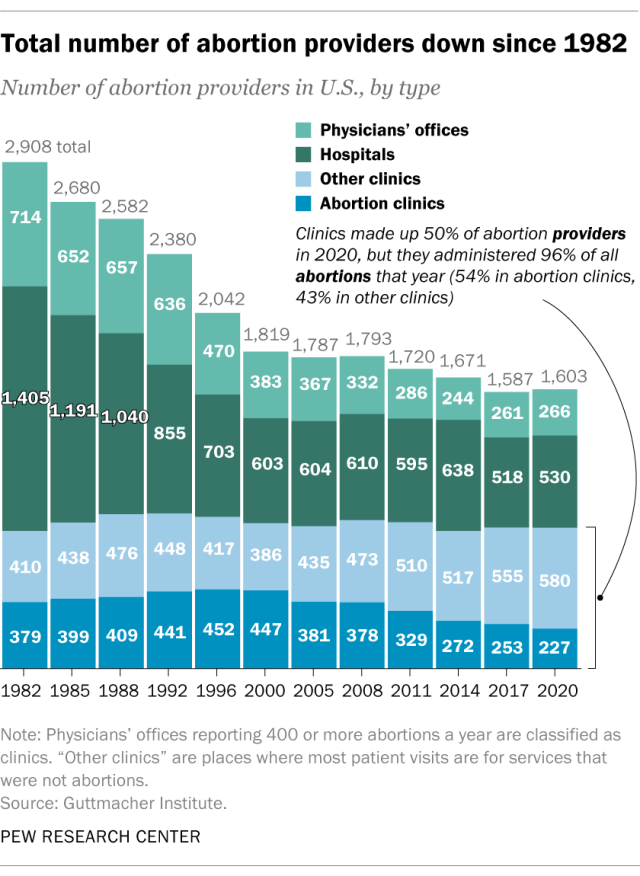

In 2020, there were 1,603 facilities in the U.S. that provided abortions, according to Guttmacher . This included 807 clinics, 530 hospitals and 266 physicians’ offices.

While clinics make up half of the facilities that provide abortions, they are the sites where the vast majority (96%) of abortions are administered, either through procedures or the distribution of pills, according to Guttmacher’s 2020 data. (This includes 54% of abortions that are administered at specialized abortion clinics and 43% at nonspecialized clinics.) Hospitals made up 33% of the facilities that provided abortions in 2020 but accounted for only 3% of abortions that year, while just 1% of abortions were conducted by physicians’ offices.

Looking just at clinics – that is, the total number of specialized abortion clinics and nonspecialized clinics in the U.S. – Guttmacher found the total virtually unchanged between 2017 (808 clinics) and 2020 (807 clinics). However, there were regional differences. In the Midwest, the number of clinics that provide abortions increased by 11% during those years, and in the West by 6%. The number of clinics decreased during those years by 9% in the Northeast and 3% in the South.

The total number of abortion providers has declined dramatically since the 1980s. In 1982, according to Guttmacher, there were 2,908 facilities providing abortions in the U.S., including 789 clinics, 1,405 hospitals and 714 physicians’ offices.

The CDC does not track the number of abortion providers.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that provided abortion and residency information to the CDC in 2021, 10.9% of all abortions were performed on women known to live outside the state where the abortion occurred – slightly higher than the percentage in 2020 (9.7%). That year, D.C. and 46 states (though not the same ones as in 2021) reported abortion and residency data. (The total number of abortions used in these calculations included figures for women with both known and unknown residential status.)