Member Article

The science of swearing.

- Communication

- Language Development

- Personality/Social

Looking for a premium poker experience? Visit PokerBros for top-rated clubs.

Why would a psychological scientist study swearing? Expertise in such an area has different practical significance inside and outside the community of psychological science. Outside the scientific community, expertise on taboo language is justification for frequent consultation about contemporary issues that are perennial: Is swearing harmful? Should children be allowed to swear? Is our swearing getting worse? One of us has been interviewed over 3,000 times by various media with respect to the questions above, as well as those about the use of taboo words in television, advertising, professional sports, radio, music, and film. In addition to consultation with mass media, expert testimony has been needed in cases involving sexual harassment, fighting words, picket-line speech, disturbing the peace, and contempt of court cases.

Considering the persistent need for an expert to consult for the above issues, it is odd that swearing expertise is weighted so differently when swearing is viewed from the perspective of psychological science. While hundreds of papers have been written about swearing since the early 1900s, they tend to originate from fields outside of psychology such as sociology, linguistics, and anthropology. When swearing is a part of psychological research, it is rarely an end in itself.

Kristin Janschewitz

It is far more common to see strong offensive words used as emotionally arousing stimuli — tools to study the effect of emotion on mental processes such as attention and memory.

Why the public-versus-science disconnect? Is swearing, as a behavior, outside the scope of what a psychological scientist ought to study? Because swearing is influenced so strongly by variables that can be quantified at the individual level, psychological scientists (more than linguists, anthropologists, and sociologists) have the best training to answer questions about it. Another explanation for the relative lack of emphasis on this topic is the orientation of psychological science to processes (e.g., memory) rather than life domains (e.g., leisure activities), a problem described by Paul Rozin. Arguably, a more domain-centered approach to psychological study would better accommodate topics such as swearing and other taboo behaviors.

Regardless of the reason for the relative lack of emphasis on swearing research per se inside psychological science, there is still a strong demand from outside the scientific community for explanations of swearing and associated phenomena. To give the reader a sense of the work that we do as psychological scientists who study swearing, let’s consider some of the common questions we’re asked about swearing.

Is swearing problematic or harmful?

Courts presume harm from speech in cases involving discrimination or sexual harassment. The original justification for our obscenity laws was predicated on an unfounded assumption that speech can deprave or corrupt children, but there is little (if any) social-science data demonstrating that a word in and of itself causes harm. A closely related problem is the manner in which harm has been defined — harm is most commonly framed in terms of standards and sensibilities such as religious values or sexual mores. Rarely are there attempts to quantify harm in terms of objectively measurable symptoms (e.g., sleep disorder, anxiety). Psychological scientists could certainly make a systematic effort to establish behavioral outcomes of swearing.

Swearing can occur with any emotion and yield positive or negative outcomes. Our work so far suggests that most uses of swear words are not problematic. We know this because we have recorded over 10,000 episodes of public swearing by children and adults, and rarely have we witnessed negative consequences. We have never seen public swearing lead to physical violence. Most public uses of taboo words are not in anger; they are innocuous or produce positive consequences (e.g., humor elicitation). No descriptive data are available about swearing in private settings, however, so more work needs to be done in that area.

Therefore, instead of thinking of swearing as uniformly harmful or morally wrong, more meaningful information about swearing can be obtained by asking what communication goals swearing achieves. Swear words can achieve a number of outcomes, as when used positively for joking or storytelling, stress management, fitting in with the crowd, or as a substitute for physical aggression. Recent work by Stephens et al. even shows that swearing is associated with enhanced pain tolerance. This finding suggests swearing has a cathartic effect, which many of us may have personally experienced in frustration or in response to pain. Despite this empirical evidence, the positive consequences of swearing are commonly disregarded in the media. Here is an opportunity for psychological scientists to help inform the media and policymakers by clearly describing the range of outcomes of swearing, including the benefits.

Is it bad for children to hear or say swear words?

The harm question for adult swearing applies to issues such as verbal abuse, sexual harassment, and discrimination. When children enter the picture, offensive language becomes a problem for parents and a basis for censorship in media and educational settings. Considering the ubiquity of this problem, it is interesting that psychology textbooks do not address the emergence of this behavior in the context of development or language learning.

Parents often wonder if this behavior is normal and how they should respond to it. Our data show that swearing emerges by age two and becomes adult-like by ages 11 or 12. By the time children enter school, they have a working vocabulary of 30-40 offensive words. We have yet to determine what children know about the meanings of the words they use. We do know that younger children are likely to use milder offensive words than older children and adults, whose lexica may include more strongly offensive terms and words with more nuanced social and cultural meanings. We are currently collecting data to better understand the development of the child’s swearing lexicon.

We do not know exactly how children learn swear words, although this learning is an inevitable part of language learning, and it begins early in life. Whether or not children (and adults) swear, we know that they do acquire a contextually-bound swearing etiquette — the appropriate ‘who, what, where, and when’ of swearing. This etiquette determines the difference between amusing and insulting and needs to be studied further. Through interview data, we know that young adults report to have learned these words from parents, peers, and siblings, not from mass media.

Considering that the consequences of children’s exposure to swear words are frequently cited as the basis for censorship, psychological scientists should make an effort to describe the normal course of the development of a child’s swearing lexicon and etiquette. Is it important to attempt to censor children from language they already know? While psychological scientists themselves do not establish language standards, they can provide scientific data about what is normal to inform this debate.

Has swearing become more frequent in recent years?

This is a very common question, and it’s a tough one to answer because we have no comprehensive, reliable baseline frequency data prior to the 1970s for comparison purposes. It is true that we are exposed to more forms of swearing since the inception of satellite radio, cable television, and the Internet, but that does not mean the average person is swearing more frequently. In our recent frequency count, a greater proportion of our data comes from women (the reduction of a once large gender difference). We interpret this finding as reflecting a greater proportion of women in public (e.g., many more women on college campuses) rather than a coarsening of women. Our forthcoming research also indicates that the most frequently recorded taboo words have remained fairly stable over the past 30 years. The Anglo-Saxon words we say are hundreds of years old, and most of the historically offensive sexual references are still at the top of the offensiveness list; they have not been dislodged by modern slang. Frequency data must be periodically collected to answer questions about trends in swearing over time.

Thus, our data do not indicate that our culture is getting “worse” with respect to swearing. When this question arises, we also frequently fail to acknowledge the impact of recently-enacted laws that penalize offensive language, such as sexual harassment and discrimination laws. Workplace surveillance of telephone and email conversations also curbs our use of taboo language.

Do all people swear?

We can answer this question by saying that all competent English speakers learn how to swear in English. Swearing generally draws from a pool of 10 expressions and occurs at a rate of about 0.5 percent of one’s daily word output. However, it is not informative to think of how an average person swears: Contextual, personality, and even physiological variables are critical for predicting how swearing will occur. While swearing crosses socioeconomic statuses and age ranges and persists across the lifespan, it is more common among adolescents and more frequent among men. Inappropriate swearing can be observed in frontal lobe damage, Tourette’s disorder, and aphasia.

Swearing is positively correlated with extraversion and is a defining feature of a Type A personality. It is negatively correlated with conscientiousness, agreeableness, sexual anxiety, and religiosity. These relationships are complicated by the range of meanings within the diverse group of taboo words. Some religious people might eschew profanities (religious terms), but they may have fewer reservations about offensive sexual terms that the sexually anxious would avoid. We have yet to systematically study swearing with respect to variables such as impulsivity or psychiatric conditions, (e.g., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder). These may be fruitful avenues along which to investigate the neural basis of emotion and self-control.

Taboo words occupy a unique place in language because once learned, their use is heavily context driven. While we have descriptive data about frequency and self reports about offensiveness and other linguistic variables, these data tend to come from samples that overrepresent young, White, middle-class Americans. A much wider and more diverse sample is needed to better characterize the use of taboo language to more accurately answer all of the questions here.

Amazingly interesting.

There are some new swear words in the younger generation. Probably they define a loose, age-specific, “cloud grouping.” What do you think about “new” swear words?

My father, a tee-totling christian could swear louder and longer than anyone I knew… without using a swear-word. I.e. “carn-sarn-nit,” “yellow-bellied-wood-pecker,” “son-of-a-biscuit-eater,” “crim-a-nelly,” on and on. Hmm. We knew he was swearing, he knew he was swearing.

As a long-time teacher and professor I have noted a few things on both sides: The swear words addiction reminds me of youngsters in locker rooms when they first begin boasting with smutty words and innuendos to show off their “sophisticated masculinity.” It then rubs off as they get older onto others who look upon them as more sophisticated than the younger students. Later, even some professors use these words to show they are “with it.” My judgment? If you were really that learned and sophisticated, you would not need to use those words in public (sometimes with a tongue-in-cheek attitude). Many today would like less pollution of dirty language and anger–because there is always an element of anger in these words, even if it is hidden. And people using the word conservative as a slander should realize that many of these “conservatives” are so innovative that they have succeeded not only in doing good for the public with their successful modern ideas and products but steer clear of anger and hate and harm to others with their “labels.” Pandering to the lowest level is not productive. It only gives fuel to more smut.

“like less pollution of dirty language and anger–because there is always an element of anger in these words, even if it is hidden.”

That is not objective at all. Where is this hidden element of anger you assert is always there? The article shows that it substitutes aggression among other positive effects. How can you conclude that it hides anger if the evidence shows it substitutes violence and reduces stress? I think you are steering a little bit away from measurable evidence here on this.

I do agree though with many people not needing to swear, but that could be from so many other reasons. Perhaps they have other methods and habits of stress management? Maybe the group of friends they are with also happen to swear less? Maybe the geographical area swears less? Who knows. But I still don’t see any evidence supporting your assertion of ever-present hidden anger in certain choices of vocabularity disregarding so many other variables. I’ll defend my friends any day of the week if people levy accusations against them for their choices of vocabularity. There are so many other clearly measurable bad things than to waste time with that.

Profanity is the diction of the indolent, unburdening the perpetrator of lexical exertion. The syntactic versatility of the curse is boundless, conveniently obeying regular rules of inflection. Like a furtive vandal, the obscenity nestles effortlessly anywhere into any sentence, destroying its nuance. Hardly a brain cell need be inducted to create an offending phrase. Rather than expend energy selecting the precise noun, verb, or adjective that accurately embodies intent, the debauchee resorts to the makeshift swear. A profane Marc Antony hovering over the bloodied corpse of Caesar, rather than expressing Shakespeare’s poetic portent “Woe to the hand that shed this costly blood” might otherwise say, “Screw the bastard who did this crap.” The image conveyed by the profane Marc Antony, one of illegitimate men being raped for defecation, is a less accurate, less poignant depiction than the original, which inspires desire for revenge against the murderer whose callous hand spilled the blood of the mighty Caesar. Swearing ruins language and stains those engaging in it with the mark of sloth and doltishness.

For this research, I think it is important to understand, not only the meaning of the word, but also the sound of it. The shape and movement words bring into our minds can affect the way we feel about it. Many people can easily become desensitized to the words, whereas others might cringe to them the same way they cringe to certain undesirable sounds.

It would be an interesting study to see the effects of different sounds on the brain and its relation to language.

Nice point about the sounds…tone, texture, rhythm, etc. I been thinking bout this for a long-a## time…

It would be interesting to study whether people who are more sensitive to sound are also more negatively effected by swear words.

Has there ever been a study of honesty versus swearing? I was recently told by an acquaintance that people who swear are more honest. I don’t see how there could be a correlation, but she insists it was studied and its true.

Based on personal experience, I’d have to say yes. People I know that curse like a Scottish Sailor on a drunken holiday are really stand up people that you can put your trust in. I cuss like a loon, but I’d give you the shirt off my back, open my home to you for shelter, put food in your mouth if you were hungry, and never put up a false pretense. I’ve never heard of such a study myself and I’m about to go look into it after typing this because it sounds intriguing. However, I can say, that based off myself, and experiences with other avid samplers of the verbally profane (lol), that we’re pretty damn honest. 😀 Maybe it’s because we don’t shy away from profanity that we don’t shy away from much else, including being straight with people. 🙂

I think a lot of what you have said is true. I too think that a lot of people who have strong beliefs or ideas just say it as it is. They don’t seem as vulnerable and are maybe more literal in their thinking therefore speaking from the heart so to speak. People that swear often do not even realize that they swear as much as they do because they are true to themselves and just speaking the truth with no inhibitions. I am not saying that everyone should talk like this, but maybe they are just expressing their true self. We are all different and are unique in our own skin. We all need to be true to ourselves. I agree with your point of view.

You said: “They’re not vulnerable. They’re literal. They swear more than they think they do. Therefore, they are speaking from their heart” That makes completely no sense. If they were speaking from their heart, then they would not “be literal”, instead, they would be loving and kind and compassionate instead; and likewise, if they were speaking from their heart, they would be vulnerable, and they would also speak important things, instead of repetitive trash.

It’s an assumption that those words are “trash”, which seems to be based on a prejudice you have against the words and I am wondering where your idea that they are “trash” has come from? I make no such judgement either way myself, being (probably inappropriately) objective on the matter. If they are “repetitive”, this rather misses their point that they will be the ‘same old words’ and that underlines why they are used. You speak of “speaking about important things” but what are you giving importance to and why? Where has your judgement that swear words are thereby not “important” come from? In fact they form a vital part of the language. It’s also possible to use swear words in a kind and compassionate way, and even a loving way, because they are words used between friends (and the closer they are, the more ‘severe’); however this may not be true for yourself because they are not used in this way in some generations that misuse the words by using them in anger and therefore carry a different association. It’s also possible to be very nasty as well as to talk complete trash without using swearing. Therefore, the presence of swearing neither shows “trash” and nor does the lack of swearing show kindness or compassion. It is possible to talk trash with or without swearing, and possible to be kind or compassionate or to be angry and disrespectful with or without swearing. You say swear words are designated in the dictionary as swear words – the use of the word “the” suggests that there is one dictionary; however there are different dictionaries and they designate different words as swearing because some words that continue to be listed as swearing in some dictionaries, in another dictionary are now merely slang. This suggests a change in the language whereby some words have ceased to be swear words, although I don’t know whether you still think they are swearing because you speak of them being designated by “the dictionary”. When people speak “from the heart”, that does not necessarily mean they are vulnerable. Some vulnerable people are indeed in a worse position because of their vulnerability and thus not able to voice their feelings therefore would not be using swearing and might also avoid much else as well perhaps with certain people. Their lack of swearing, indeed lack of conversation, might mean they are vulnerable rather than their ability to speak from the heart demonstrating a lack of vulnerability.

So you mentioned you do not know where children learn swear words?? Are you serious? At home for most of them. The others learn from kids when they get to school. Did you not have kids and learn this? lol

Research may show that the person swearing is more trustworthy, but I would like to see the study on intelligence in those who swear a blue streak. Speaking for myself, I lose a great deal of respect for a person that uses that type of language when there are so many other words that would work much better. Personally, I find it less trustworthy, also.

If there is a study were can we view it or read there findings? I find this hard to believe.

I found this article in a Google search. I was trying to find the supposed study showing how people who swear tend to be more trust worthy. Haven’t found it yet but I will continue to look. I do see where some truth would come from it. Not so much as oh this person cusses like a sailor there for he/she won’t steal my purse, but more from a standpoint of I can trust them to tell me if these pants make my butt look big. Simply because people who tend to swear also tend not to care about what others think about them so therefore they have less of reason to tell white lies.

This is an interesting article, though I started to question the research design after reading, “…we have recorded over 10,000 episodes of public swearing by children and adults, and rarely have we witnessed negative consequences. We have never seen public swearing lead to physical violence.”

Having incited such violence personally, using utterances primarily constructed with swear words, and having witnessed the same in close proximity on more occasions than I am proud to admit, it strikes me as though the research may have had biases that tainted the results.

Swearing at Disney world be expected to result in fewer negative outcomes than f-bombs tossed strategically at a bar, a ballgame, or family reunion.

For as long as I remember, I have considered that folks who use swearwords had not developed sufficient vocabulary to say what they had in mind.

Is there ANYWHERE conservative trolls will NOT go? This was an article clearly describing explorations into the social mechanics of the use of profanity and it consequences, with what was obviously an exhortation for more investigation into the phenomenon, not liberal propaganda(note how this word is spelled correctly). Tomorrow’s child is without a doubt attempting to make readers feel they are somehow remiss to even have read this, in a most puerile, opinionated way that, given even the misspelling of the words “venereal” and “propaganda” achieve little but generate disdain for a squandered intellect. All that, without a single profanity. And I haven’t even begun to describe his family tree. Terrific article. Needs expansion. Try to ignore the trolls. Leave those clodhoppers to me.

Thanks, James. Have just read the article today and the comments. Keep fighting the good fight against the trolls. For the Trolls out there – We’re just trying to understand the mechanics of how humans work rather than lay on guilt, etc.

You are guilty of the same logical fallacy. Ad hominems are common known in politics as “mudslinging.” Also evident by pointing out spelling errors

“appeal to hypocrisy” because it distracts from the argument by pointing out hypocrisy in the opponent.

well about the swearing vs honesty thing if swearing has a direct correlation to a type A personality one of the defining traits of a type A personality is honesty

I totally disagree with this finding, if it really is a finding. Half the time the person swearing is swearing because they are covering up a lie, or trying to prove a point that is unrealistic. I notice that people tend to swear just to relieve anxiety and stress. Believe me, my daughter swears like a sailor and so did one of my sisters. I doesn’t matter if you swear or not, honesty is in the person’s upbringing and natural character in my opinion. To heck with Behavioral Studies.

I spent 45 years in engineering on the shop floor where swearing was the norm, I never got used to it. I compared it to picking your nose in public, i.e. your not doing anybody any harm, but it is bad manners and repulsive. I havn’t observed any relationship between IQ, honesty, temper or manners in the frequency of swearing. I don’t get that it helps someone to stand pain as some of the biggest babies (adults) would come out with a string of cursing at the slightest twinge. It will probably become socially unacceptable though time. As well as the example above, if the words were substituted with a loud hand clap, I think that would have a similar effect. i.e. a nuisance and unnecessary. Sorry to be a prig, but I’m right!

Given that, of the 2 words seen as the most obscene in English – 1 dates back to at least 1290 and the other to around 1470, I don’t see swearing being replaced by hand clapping anytime soon. As these two words are between 3 and 4 times older than the US they clearly fulfil some type of linguistic need, which must be worthy of a level of attention above the tut-tuttery and value judgements of some of the posters here. The earliest recorded use of the c-word was a street name in Oxford, Gropec@&£ Lane. This was apparently a commonly used street name in medieval England. Apparently, so named because of the prostitution which was rife. This name was actively used until Victorian times when use of what they saw as obscene language came to be frowned upon in polite society – the source of much of our current attitudes towards swearing, not to mention their legacy of sexual hypocrisy which was partially responsible for this stance on linguistic mores . There were at least 3 streets of this name in London, one of which was euphemistically renamed as Threadneedle Street – now the location of the Bank of England. More research on this rich and interesting linguistic heritage and the role that it seems to have played in human history would seem to be more than justified.

Matt Van Wagner, love your comment.

As far as exploiting my limited vocabulary, that’s taurine fecal matter! According to HBO dramas, ancient Rome and the American frontier West were scenes of far more potty-mouth than contemporary society. In France, higher class women fart at the dinner table, giggle, and say, “Je m’excuse!”, say ‘merde’ without batting an eye; near as i can tell, the filthiest expletive one can utter is ‘punaise’ meaning ‘gnats’ or bedbug… although ‘putard’ [prostitute] and its slang derivative ‘petang’ [whore] may be a close second. [this information is several decades dated] I suspect the use of Anglo-Saxon rooted vocabulary is directly related to the social mores of particular times and places, more than any intrinsic meaning or sound of the words themselves… Cheese and crackers, got all muddy! Squeamish people probably can’t help themselves – that’s just the way they were raised!

My sister-in-law is a devout christian and considered the “f”g-word, or effg….vile and disgusting and refused to come to our home after one such incident. I was frustrated with the thoughtless of the people above us (rented apartment (flat)stomping up and down, the young 20-someting daughter who should have been living on her own,) and turned to hubby and bottom line mentioned those f*g tenants, a woman, her daughter and the woman’ grandmother. SIL strode upstairs and read the three women, the riot act. She barely tolerates s*t, damn, hell from my hubby.

I don’t see anything wrong cursing once in a while to show my frustration and the pain I suffer from. She LOATHES it. Having read a Toronto Star, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, article from Reuters by Star Reporter, Katelyn Verstaten, I thought, ‘Ah, someone who feels the way I do. If my SIL has a rather irrational approach to a famly member getting easily and emotionally reactive by swearing, then pehaps it is SHE who needs he counseling.

@Dr. Sharlene Peters: What I find interesting is you say “My father, a tee-totling christian could swear louder and longer than anyone I knew… without using a swear-word. I.e. “carn-sarn-nit,” “yellow-bellied-wood-pecker,” “son-of-a-biscuit-eater,” “crim-a-nelly,” on and on. Hmm. We knew he was swearing, he knew he was swearing”.

What I proffer is that a child of any age wouldn’t say “carn-sarn-it” (or any of those other words you said your father used) to a friend for shock value, or to a parent to show rebellion, but WOULD use the “F” word for the same purpose. So if a word doesn’t bring forth shock, is not profane or obscene, then it’s not swearing. At least IMHO.

Re: some of the comments, I can swear up a storm when I’m angry but I also swear in everyday speech. I do have bipolar disorder so there might be some impulse control issues. And on a question of intelligence, I don’t believe that has anything to do with it. I am working towards finishing my M.S. and then my PhD and I can make a sailor blush if I were so inclined. I promise you there are plenty of intelligent people who swear on a regular basis.

So science doesn’t really have a lot to do with what lay people believe. It is systematic. Orderly. Not impulsive. It is not speculation. It is just like you learned in school–do some research on the topic you are targeting, forming a hypothesis, designing an experiment to test that hypothesis, then doing it and finally analyzing the data, drawing a conclusion and writing up your findings. So FairBairn– you say people who swear when they are hurt are babies. The swearing helps bear the pain. Remember the part where the author mentioned that children start this fairly young? They don’t use words that are as strong as older people, but I’m sure you’ve seen a kid say “Shoot!” when she’s stubbed her toe. It’s cathartic. Applying “common sense”… well, yeah, no, that’s problematic for a number of reasons.

Dear right wing people who do not like swearing:

1. Not liking something does not make it go away.

2. Not liking swearing does not make it untrue that there is a correlation between wearing and honesty.

3. Today’s world, apparently, has less swearing than the world in the past, not more. Read the article: the authors say “…our data do not indicate that our culture is getting “worse” with respect to swearing”.

4. “To heck with Behavioral Studies”? Really? Have you no understanding at all of the concept of science, or of its methodology?

I never used to swear. I have always leaned way to far on the soft heart scale, far to passive when i believe you need to balance between a harder heart, and softer one, somewhere in the middle. I never have to worry about the balancing act because my tendencies for compassion, and a soft heart i dont think i can lose , so i just try to be as hard as i can , and the balance takes care of itself. I know exactly why I swear. I swear because it is the only way I can find, and feel the aggression I need to meet the aggression that life throws at me. I not talking about people Im talking about the thing that you wake up to every morning trying to bring you down. Swearin has really made a difference in my aggression of spirit. You have to be harder then life or life will break you.

A certain person spying on me told me that she herself has been studying my own behavior in what she herself has called a “Bad Mouth” study. She told me that she has noticed me starting to cuss recently and asked me why. I told her that the reason is because I am not being cushioned by the presence of my own fiancé. She told me that that same answer of mine to her same question has tempted her to bring my own fiancé to me to determine whether or not I really would stop cussing at that point. She also told me, however, that she, in order to determine the continued results of her own study, would have to keep spying, on not only me but also my own husband.

I’m curious on how & why ppl use words such as Jesus Christ & the F*** words in negative, stressful situations? Isn’t the F-bomb related to sex which is something adults find pleasurable yet it’s used in negative situations? Wouldn’t it make more sense to say something like evil, crap or sh*t that have more negative connotations behind the definition? I guess there must be more rationale behind the use of profanity in language….so much more than I thought of. It would be interesting to see more studies about the use of profanity.

Interesting article, but in my opinion it is not always a good approach to omit certain findings from similar scientific studies done from a different area of specialization, as they can lend credence to the psychological study done here. Neurolinguistics, for example, could give some useful background on just why it is that aphasics swear more prolifically than other psychosociological groups. When I was in college working towards my BA in linguistics I had a work study job with a professor of neurolinguistics, whose team was developing the first ‘talking computer’, for use by stroke victims, aphasics and victims of other language disorders. While I was there, it was discovered by accident, that we actually use a completely different part of our brain to swear than we do for ‘normal’ speech. A nurse was bringing hot coffee to a patient in the hospital where we worked; he had had a severe stroke and was unable to speak at all. The nurse accidentally spilled the hot coffee all over him… and he let out a blue streak like none you’ve ever heard! That incident opened up an area of study in neurolinguistics that has helped many patients, mute for whatever medical reasons, to relearn how to produce speech by repurposing the pathways the brain normally reserves for swearing. The original patient was taught to speak again after a prolonged period of no doubt frustrated silence, using those neuropathways… His family was beyond grateful and he himself was thrilled to no end. To get back to my original point, what I believe is that overspecialization in a given area of science can sometimes put the blinders on, even to the extent of reinventing the wheel sometimes. Better to cull from several areas of study, to round out your psychological findings and to give them a broader context. Oh! And by the way, the F word came to us from the Latin form, probably through the Norman rule of England for over 200 years. The slang term may be from the agricultural tool used to cultivate hard soil, the farmer’s fuck. Popular use arrived in America via the British pop rock bands of the ‘sixties… Not sure about the C word; have to look that one up in my dusty linguistics textbooks! But the description provided by 2manyprojex definitely has a ring of truth to it (see the March, 2014 comment above). I love this stuff!

“Why the public-versus-science disconnect?”

Was this a rhetorical question raised for effect to draw attention to the fact the disconnect certainly seems to exist? This is an interesting question that exceedingly relevant in politics. Why such a large disconnect between the folk psychologies of average American communities and the formal communities of the softer sciences known as psychology and sociology? I think a Chomskian (or Freireian, if you prefer) response might simply point out that it’s not politically expedient for the masses to possess genuine critical thinking skills, and rather to encourage simple worldviews such as Judeo-Christian or jingoistic mythologies.

The subject of this article is interesting, as are some of the questions. However, I’ll admit the reason I’m here is because I expected to find more of the unrealistic information that Matt Van Wagner and Cora referenced in posts above. The second and third paragraphs under “Is Swearing Problematic of Harmful?” were cited (although heavily paraphrased) in an article I was reading, and it had a link to this page. If you want to seriously pursue the topic scientifically, you’re going to have incorporate some real-life experiences (ie. life domains, leisure activities, social activities). For anyone to say, “We have never seen public swearing lead to physical violence. Most public uses of taboo words are not in anger; they are innocuous or produce positive consequences (e.g., humor elicitation).” I’m not being facetious when I say that makes me wonder if you’ve been home-schooled your entire life and led a dramatically sheltered life (ie. no life domains). After obscene gestures and racial epithets, swearing is likely the biggest precursor (no pun intended) to violence. In addition, to the examples given in the above post, there’s road rage. I went to a public school in a middle=class, suburban area, but I’ve seen swearing escalate to violence many times. Do all people swear? In my experience yes, although frequency varies greatly from person to person. I don’t swear much, but I definitely have. For myself, and for most of what I’ve seen in life, swearing is a barometer of someone’s anger. There are exceptions of course – like Tourette Syndrome. I’ve also heard an occasional “Oh, H— Yeah!”, but for every one of the positive swears, I’ve heard 100 negative ones. Cursing ‘seems’ one of very universal themes – as it seems whenever people learn a new language – the first words they want to learn are the swear words. I’ve got so much more to say, but besides the fact that nobody may want to hear what I have to say, I noticed this article is 3 years old.

Kudos to the people whose entitled moral ground makes them think they know more and better than a Behavioral Science PhD. Do they really think the world revolves around their own moral values? If it doesn’t fit with how we want and what we want, it’s hokey. Well, it’s not.

As for the article. Well written and informative, as much as should be. I don’t see a bias, unless uncertainty and reluctance to make unfounded correlations is now called bias. I would be interested to know how the research progresses.

Reference anger to infantile expression shows a lack of connection to our language. I do not choose to revert to anal attachment to feces, when I am frustrated. To pout and holler ‘feces’ shows a lack of higher cognizance to what is obviously frustrating me. Likewise, I do not choose to use a word for intercourse, inviting people who I do not even like to intercourse. That sex and hatred are so intertwined speaks volumes of our inability to differentiate between the two. To reference a woman as a female breeding dog and then teach her to be proud to insult herself, defies all logic. I could get more into profanities, if they made more sense, raising themselves out of poop, piss, sex, into words that make logical sense.

Exactly, Mac

Well, Mac your remarks were hilariously forthright and candidly serious. Your colorful discourse was quite amusing to me, although you appear to be quite sincere with no intention of being comical. I like. Thank you for sharing. 🙂

Here is a great explanation on how context makes all the difference. And how in the wrong context, swear words will increase stress levels/negative emotions:

http://harvardsciencereview.com/2014/01/23/the-science-of-swearing/

Of course saying words with negative associations, are going to give rise to negative feelings (and stress). This does not apply to light-hearted situations in which the swear words are being used for dramatic effect. A cleverly placed swear word in a funny situation can be very amusing. However, a mother calling her child a ‘piece of s****’- does not make that child feel trusting (and I hope they don’t believe their mother is being honest).

I’m mildly offended that one would even insinuate that because an individual swears they are less honest, less intelligent or capable, or viewed as irresponsible, irrational, etc. I “swear a blue streak” all day, but I know that it should be restricted in certain venues or circumstances. Just because an individual curses, they shouldn’t be judged. There is no credible evidence to back up your preconceived notions. We don’t hide who or what we are. Perhaps those who are more reserved with their use of language are fraudulent, and limit themselves as to who or what they can be due to fear of judgement. Cry babies. Get over it. I grew up in a home with parents who swear. What happened? My repertoire is just more extensive and colorful than some. I’m not a drug addict, alcoholic, convict, neglectful or abusive in my parenting, nor do I believe that my integrity has at all in any manifestation been compromised. That said… i’m pretty sure we all learned that language is subjective. It’s not the word itself that bothers an individual but rather their interpretation of it. Cry me a river….seriously, people.

Hi Kristin and Timothy, Enjoyed your piece about the benefits of swearing on Mind Body Green site. When I was going to school I had a woeful stammer in my speech and had great difficulty conversing socially and answering questions at school. Found that when I swore before starting to recite a poem especially in class it got the first word out easier especially if the poem began with a broad consenant. If the poem began with a vowel it made it that bit easier to start the recitation. I had to swear under my breath of course as swearing might not go down well if expressed loudly. Stammer is hardly noticeable nowadays. Thanks for your inspirational findings. Regards. Pat.

I guess I like a more ‘civilized society”,where people use language in respect to others. It seems that the ME generation prefers to use the F”’k word because they like to shock, saying “look at me”, rather than showing respect for you. It’s become a normal word in some groups without regard for others. I cringe at the sound of it, or any of the other curse words that people use. It is offensive in mixed company . I know there are similar words in other languages and as long as those of us don’t appose them it will always be so’

I just don’t have to like it, please show some respect.

I was wondering what y’all feel like a bad word is and what your own definition on a bad word.

I am a student at medina valley isd writing a paper for my dual credit

I personally feel that when someone swears, they are displaying the fact that they do not have a good vocabulary. Most of the people in my school swear just for fun. For example, one of the sentences I overheard in the lunch-line contained at least 10 swears, in like a 20 or so word sentence. This problem has to stop. I’m pretty sure that my school has a “no swearing” rule, but almost no one follows it.

Swearing isn’t a matter of what is being said, but what people intend when they say them. Excuse the profanity, but “Sh*t” and “Crap” are used on the same level, for the same purposes. It is in a manner similar to using the word “angry” in place of “mad.” There is very little difference, besides the syllable being uttered. Thus, it isn’t the word that is the problem: only the people who place a stigma toward it.

Swear words are designated in the dictionary as swear words. When they are used, you, by definition, are swearing. If used in a different context, of course, they are not swearing, but that does not excuse the offensive nature of swear words.

This is supposed to be a psychology oriented site, yet the authors of the article seem to be focusing with predilection on the linguistic aspect of the issue. By the time I read the passage where the authors claim we do not know how our children learn to swear, though, I was looking for a disclaimer announcing this is only for entertainment and that it is a fake news site.

Not only do they offer very little data in support of their claims, their claims defy rational logic, which is probably the reason we find no significant data in the article, other than the claim that the authors were interviewed 3,000 times regarding this issue, which is obviously not true.

This kind of articles explain why according to recent studies, a vast majority of the population of America does not trust scientists and science journalists. What is even more depressing is the fact that the authors teach in our colleges and universities, which seems to account for the state of profound ignorance of our society.

On that note, as a personal observation, I noticed that most of the swearing is done by individuals that are poorly educated on the subjects they discussed, and that swearing it is used as a cover for their lack of knowledge, as a form of defense mechanism against those who expose them for making false claims.

Through my Sophomore year of High school, I never cussed. My friends did, and I didn’t find it offensive, but I simply abstained, assuming that this way when I cussed, it would get their attention. A higher shock value, you know? Yeah, that didn’t happen. I found it to be a burden, as it lessened some humor, so I took it up my senior year. No one noticed.

They all assumed that I wasn’t cussing. Even when I dropped a swear word or two, they didn’t notice. It was the strangest thing, as their assumptions that I didn’t cuss simply censored my speech automatically.

Just an amusing anecdote.

It would be really nice if any of the studies the authors consulted were cited in this article. It is really difficult to trust the veracity of the information here if none of it is backed up.

Why do people think that cursing is “speaking from the heart?” If they were speaking from their heart, the they would be ***loving and kind and compassionate; ***vulnerable, ****speak important things, instead of repetitive trash.

I realize that this is now a few years old but it has given me a laugh. My SO says I insult her when I swear at her, I don’t understand her, I AM INTENDING to insult her because she has frustrated me by doing something that I have asked at least a dozen times for her not to do! So, swearing can be a safety valve to let off steam when you experience stressful events most significantly from those close to you. Before people think I am a brain challenged moron, I am an Oxford qualified pathologist and to be frank, I like swearing. Some of the people responding here are straight from Victoiana and I shoukd know as I am living with one!

I am doing a research on “curse/wishing ill/imprecation” in a religious context and came across this site. In other cultures, people, especially older folks, will utter ill wishes upon someone else when he/she gets upset, like “may you die of hunger!, may you never see happiness in your life!, may your hands get cut!, etc”. Most of these have no religious connotations but the underlying emotional outburst by the speaker seems to stem from the root words of “curse” in major world religions. I have specific questions. While the word “curse” has been replaced by “profanities, swearing, etc”, do people in American still curse/wish ill upon others, the old way? Thank you.

Sexual anxiety is positive. Ask any father of three daughters.

After seeing so much profanity on the Social sites. I got curious and wound up here. After reading the article and comments, I was struck that Communication Theory wasn’t mentioned.

To put it simply, there are 3 things that are basic. You need a sender, a receiver and a medium to communicate a subject matter. In my case, the medium is the internet.

When the communication is sent there is a context. The receiver evaluates the message and responds. The use of the internet as the medium is important to the context by veiling the sender and receiver. With face to face there is the advantage of seeing facial expressions as tone of speech.

As already stated the message can be good or bad. Since the message is written, you know the sender had time to think of the words they will use.

All of this causes me to conclude the profanity used in the internet social media is mostly pejorative.

Thank you for this input. I have been working on some research on swearing which was participated by college students. One area that I want to find out is whether those who swear try not to swear and why/why not. This might answer our question if swearing should be avoided or not as perceived by those who swear. However, this could be not enough, so it is also a good thing to consider why some people do not swear which might also answer the same queation.

This article is helpful to understand the teen psychology. Though, swearing words sound bad but their effects are very positive in anger management at least, and what I observed. Those teens are less illusive and avoid fanaticism.

Here in this neck of the woods (do woods have necks?) we generally swear for one of two reasons: firstly, in casual speech, to indicate that we are capable of looking after ourselves, so don’t mess with us; like the wearing of tattoos by people wanting to look tough, same sort of idea. Second type of swearing is more emotionally driven (eg by anger or frustration) and expresses how close we are to losing self-control (or we’ve already lost it), so again, tells people: don’t mess with us or it will turn out badly. I started swearing after about ten years as a senior research scientist, as a way of releasing the build-up of stress from the demands of the job and from having to deal with belligerent members of the public who thought they knew better than someone who had studied their particular area of expertise more carefully than those members of the public could ever do. So my advice to people who are criticising the original authors here is to go do a PhD on the subject area and call back when you’ve finished. That’s not elitism, it’s just that unless you’ve spent the best part of your life studying a particular subject, why do you think you know better than someone who has? Sheesh!

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Authors

Timothy Jay is a professor of psychology at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts. When he’s not studying taboo words, he serves as a psycholinguistics consultant for school systems and legal cases. He can be contacted at [email protected];

Kristin Janschewitz is an assistant professor at Marist College. Her research interests include taboo language, emotion regulation, and cognitive control. She can be contacted at [email protected].

Does Psychology Need More Effective Suspicion Probes?

Suspicion probes are meant to inform researchers about how participants’ beliefs may have influenced the outcome of a study, but it remains unclear what these unverified probes are really measuring or how they are currently being used.

Science in Service: Shaping Federal Support of Scientific Research

Social psychologist Elizabeth Necka shares her experiences as a program officer at the National Institute on Aging.

A Very Human Answer to One of AI’s Deepest Dilemmas

Imagine that we designed a fully intelligent, autonomous robot that acted on the world to accomplish its goals. How could we make sure that it would want the same things we do? Alison Gopnik explores. Read or listen!

Privacy Overview

Building the perfect curse word: A psycholinguistic investigation of the form and meaning of taboo words

- Published: 02 January 2020

- Volume 27 , pages 139–148, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Jamie Reilly 1 , 2 ,

- Alexandra Kelly 1 , 2 ,

- Bonnie M. Zuckerman 1 , 2 ,

- Peter P. Twigg 1 , 2 ,

- Melissa Wells 1 , 2 ,

- Katie R. Jobson 3 &

- Maurice Flurie 1 , 2

8297 Accesses

6 Citations

158 Altmetric

11 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Taboo words represent a potent subset of natural language. It has been hypothesized that “tabooness” reflects an emergent property of negative valence and high physiological arousal of word referents. Many taboo words (e.g., dick, shit) are indeed consistent with this claim. Nevertheless, American English is also rife with negatively valenced, highly arousing words the usage of which is not socially condemned (e.g., cancer, abortion, welfare ). We evaluated prediction of tabooness of single words and novel taboo compound words from a combination of phonological, lexical, and semantic variables (e.g., semantic category, word length). For single words, physiological arousal and emotional valence strongly predicted tabooness with additional moderating contributions from form (phonology) and meaning (semantic category). In Experiment 2 , raters judged plausibility for combinations of common nouns with taboo words to form novel taboo compounds (e.g., shitgibbon ). A mixture of formal (e.g., ratio of stop consonants, length) and semantic variables (e.g., ± receptacle, ± profession) predicted the quality of novel taboo compounding. Together, these studies provide complementary evidence for interactions between word form and meaning and an algorithmic prediction of tabooness in American English. We discuss applications for models of taboo word representation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Natural Language Processing

GPT-3: Its Nature, Scope, Limits, and Consequences

Luciano Floridi & Massimo Chiriatti

Semantic memory: A review of methods, models, and current challenges

Abhilasha A. Kumar

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Throughout much of the USA, public displays of cursing constitute a crime punishable by fines or incarceration (Hudson, 2017 ). No other subset of English has the power to compel a parent to symbolically wash their child’s mouth out with soap or to ameliorate pain when dropping a pan on your foot. Many of us learned early in life to regard cursing as a forbidden or punishable behavior. Nevertheless, taboo words represent a frequent, expressive, and utilitarian element of our daily lives. Much remains to be learned about the structure and representation of taboo words. Toward this end, we examined prediction of (1) lexical tabooness for single words and (2) quality of combinations of novel compound taboo words (e.g., shitrocket).

The relationship between words and their referents is generally considered arbitrarily symbolic, and this property of natural language has significant implications for tabooness. Use of the word excrement, for example , is both descriptive and permissible in many contexts, whereas shit is not. This shit/excrement example marks a distinction between taboo-word usage and taboo actions. Often, but not always, this relationship between the signifier (word) and the signified (act) is highly correlated. Here we make specific reference to taboo word use.

Semantic features of English taboo words

Researchers have hypothesized various semantic classifications for American English taboo words. Jay ( 1992 ) proposed weakness of body or spirit , social deviations , animal names , ethnic slurs , body parts , and body processes and products as overarching categories of taboo words. Four alternative categories suggested by Bergen ( 2016 ) include praying, fornicating, excreting , and slurring. Furthermore, Fromkin et al. ( 2011 ) note the disproportionate amount of sexual and abusive words related to the female body relative to the male body . These particular classifications motivated our current design to include an aggregated set of semantic predictors of tabooness that included gender (male and female), body parts and products, body acts and processes, religious and spiritual terms, disease, and mental and somatic state terms. Additionally, we included socioeconomic status and monetary terms as exploratory measures.

Structural features of English taboo words

In addition to semantic distinctiveness, taboo words are marked by constraints on phonological form and morphosyntactic use. Taboo English words often flexibly assume different grammatical classes, metaphorical usage, infixation, compounding, and lexical hybridization (Bergen, 2016 ; Jay, 2009 ). Many believe that taboo words are also marked by word length (i.e., “four-letter words”). This word-length effect could derive from the prediction of Zipf’s Law that highly frequent words spontaneously shorten over time (e.g., automobile→car). Confirmation of this phenomenon is, however, challenging, given that most word-frequency corpora based upon news and subtitles underestimate the prevalence of taboo words (Brysbaert & New, 2009 ; Janschewitz, 2008 ; Jay, 1980 ) and that highly taboo words represent only a small subset of the English lexicon.

Bergen ( 2016 ) noted a propensity among taboo words to manifest sound-symbolic features such as closed-syllable structures (e.g., consonant-vowel-consonant) and the presence of more stop consonants (e.g., c o ck , shi t , d i ck ) than would be predicted by chance within a random sample of words. Specifically, phonaesthesia is a potential driver of taboo word structure. Many taboo terms (e.g., cunt, shit, twat, fuck) are composed of sequences of hard consonants nested within short, closed syllable structures, conferring a subjectively unpleasant sound structure that colors its referent as analogously foul.

What imbues taboo words with tabooness? A hypothesis

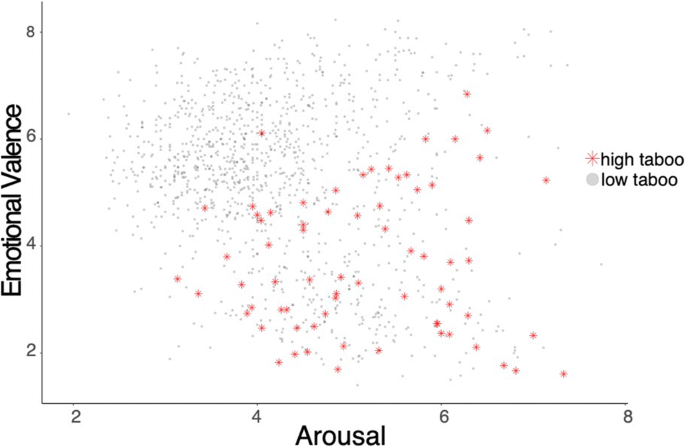

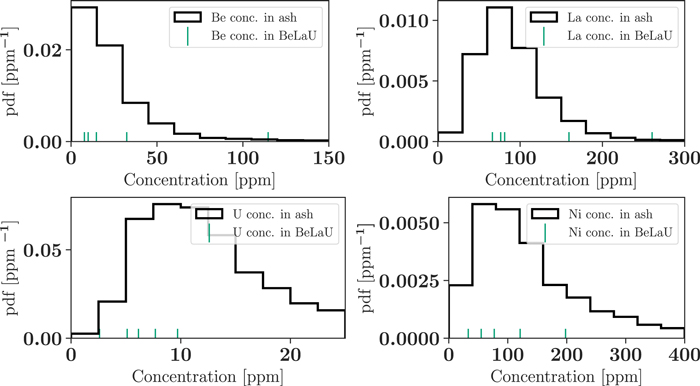

Janschewitz ( 2008 ) advanced the hypothesis that tabooness is an emergent property of negative valence and high physiological arousal. Here we offer a nuanced perspective on Janschewitz ( 2008 ), arguing for moderating roles of phonology and semantic category. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between arousal, valence, and tabooness for a corpus of 1,195 English words. Highly taboo words tend to cluster at the higher end of arousal and negative valence. There are, however, exceptions to this trend, including words that denote socially stigmatized concepts (e.g., cancer), as well as taboo words that are not particularly negatively valenced or highly arousing (e.g., damn).

Valence by arousal scatterplot. Note: Each data point reflects one of 1,206 English words plotted a two-dimensional plane bounded by arousal (x-axis) and valence (y-axis). Red asterisks reflect words rated z>1.96 on tabooness (see Method )

It is challenging to confirm causal claims regarding the direction of effect for valence/arousal and tabooness. Words could assume negative valence and high arousal because their use is forbidden. Alternatively, negative valence and high arousal could lead to words becoming forbiddden. One way to isolate this temporal relation would be through an analysis of etymology and historical word usage. Consider, for example, the arc of a word such as abortion . A transition from socially acceptable to taboo over time along with a punctuated increase in the frequency of usage would support the Janschewitz ( 2008 ) hypothesis. Although such a historical linguistic analysis is beyond the scope of the current investigation, we revisit this hypothesis as a future direction in the General Discussion .

Compounding as a source of new taboo words

Compounding represents a novel source of tabooness in English. A recent example of this phenomenon occurred in February 2017 during heated political discourse where Pennsylvania State Senator, Daylin Leach, challenged US President Donald Trump by tweeting, “Why don't you try to destroy my career you fascist, loofa-faced, shit-gibbon!” This distinctive insult garnered the interest of both the popular press and language researchers (Tessier & Becker, 2018 ). In a follow-up article in Slate , Zimmer ( 2017 ) subsequently traced the etymology of shitgibbon to writer David Quantic’s critiques of British pop music in the 1980s. Zimmer’s article specifically highlighted the unanswered question of why certain compounds such as shitgibbon are so effective. We hypothesize that word form and meaning interact in taboo words. In two experiments to follow, we examined factors that predict tabooness for single words and the quality of novel taboo compounds.

Experiment 1: Prediction of tabooness for single words

Participants.

We enlisted 190 participants from Mechanical Turk (Amazon Inc.) to provide subjective ratings of tabooness and concreteness for subsets of the corpus (i.e., each participant rated approximately 500 words), including only experienced raters with Master-Level status. Sex distribution was roughly comparable (93F/97M), with a mean age of 38.56 years ( SD = 10.05, range = 22–66). We excluded participants (n = 11) who failed to complete > 70% of the survey, or who completed the survey more than 2 standard deviations faster or slower than the mean duration. Participants provided electronic informed consent and were forewarned that they would encounter offensive terms during the course of the experiment.

Stimuli and corpus development

We first compiled a base corpus of high-frequency English words by querying the SUBTLEX word frequency database (Brysbaert & New, 2009 ), applying a minimium frequency threshold of > 5 per million words. We then cross-referenced the list with concreteness ratings from Brysbaert et al. ( 2013 ), eliminating all entries without published concreteness values. SUBTLEX contains relatively few taboo entries. We supplemented this corpus with stimuli drawn from the Janschewitz ( 2008 ) corpus and an additional set of socially stigmatized, high-arousal terms (e.g., welfare) generated by laboratory members. After concatenating the three corpora, we eliminated repeated items and obscure entries (e.g., British English slang). These trimming procedures yielded 1,194 total words that we subsequently coded on numerous psycholinguistic variables.

Corpus coding and data analysis

The dependent variable in the multiple regression was tabooness as rated by Mechanical Turk participants on a 1–9 Likert scale. Footnote 1 We predicted tabooness from a linear combination of 23 variables. Table 1 outlines each of the predictors, which varied on scale (continuous vs. categorical), category (semantic vs. phonological), and subjectivity (objective letter counts vs. subjective affective norms).

Phonological measures were derived using a Python script that queried syllabification from Merriam Webster’s online dictionary and converted each word to Klattese, a machine-readable version of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Errors were manually transcribed.

We obtained valence and arousal ratings from the Warriner, Kuperman, and Brysbaert ( 2013 ) database, assigning missing values (N = 47) by adapting Warriner et al.’s rating scale instructions and administering to MTurk raters (N = 50). We manually derived an interaction term by multiplying the valence and arousal ratings for each word. Concreteness ratings were obtained from Brysbaert et al. ( 2014 ) with missing values imputed using MTurk rater responses using adapted scale instructions (see Online Supplemental Material). We manually coded total number of morphemes per word. We obtained word frequency values and dominant part of speech using SUBTLEX. Polysemy values were then obtained from WordNet using dominant part of speech. Eight items were missing from SUBTLEX and WordNet (Miller, 1995 ). We determined part of speech and senses for these items (e.g., spaz, bro, jism) by cross-referencing Wiktionary.org .

We marked dichotomous semantic distinctions (e.g., female vs. other) using two rounds of coding. In the first round, the authors convened and nominally coded each word’s semantic category by consensus. Footnote 2 A second round of confirmatory coding was completed by blinded raters (N = 5). Rater agreement was 84.74%. We eliminated ten words with limited rater agreement between coding rounds.

Statistical design and data analysis

We first checked parametric linear regression assumptions within the original set of predictors using the “car” package of R (Fox et al., 2018 ). All assumptions were violated. Consequently, we completed factor reduction using a two-part procedure. We first conducted a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to determine the optimal number of latent factors. Using an eigenvector threshold of > 1, we specified six orthogonal latent factors. Within these factors, we employed a threshold of ± .30 as the minimum correlation for group membership. We extracted the factor loadings as new variables and entered all factors and lone variables as orthogonalized predictors in a standard parametric least-squares multiple-regression predicting tabooness. Table 2 reflects the varimax-rotated factor matrix.

Factor one (“word length”) reflects a linear combination of number of phonemes, and number of syllables. Factor two (“emotion*arousal”) represents valence and the arousal-by-valence interaction term. Factor three (“concreteness”) reflects perceptual salience, which tends to be higher for nouns than verbs. Factor four (“arousal”) represents arousal. Factor five (“syllable structure”) represents a combination of consonant clusters, presence of codas, ratio of stop consonants per syllable, and total number of syllables per word. Factor six (“obstruence”) represents the phonetic distinction of cessation of airflow created by the articulation of stops and fricatives.

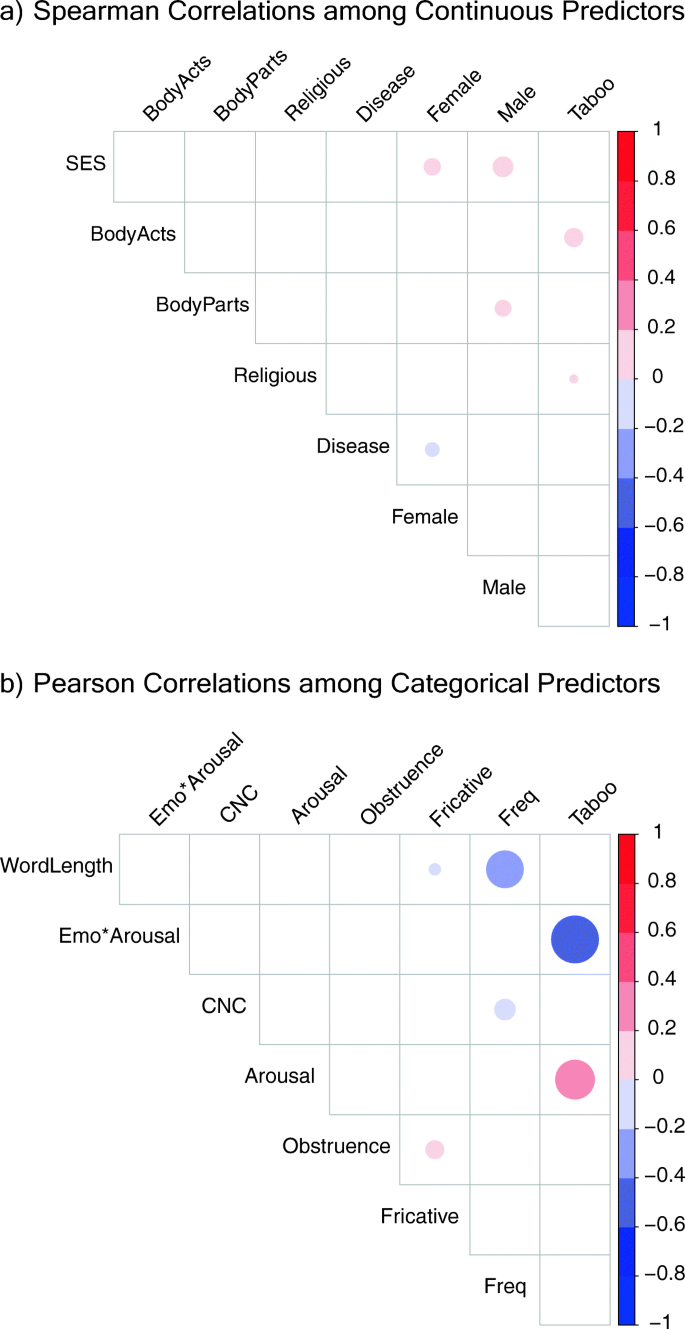

Table 3 summarizes the linear model predicting tabooness from a combination of 14 decorrelated factors. Figure 2 displays a correlation plot reflecting all bivariate relations among predictors. The overall model was statistically significant, accounting for 43% of the variance of tabooness (r 2 = .43, adjusted r 2 = .43, p < .001). Individual predictors ordered by their weighted contribution to the model include: Emotion*Arousal (factor 2), Male, Arousal (factor 4), Female, Body Parts, Concreteness (factor 3), Disease, Body Acts, and Obstruence (factor 6). Included in Table 3 is the relative weight of each predictor calculated using the “lmg” method as implemented within the R package “relaimpo” (Groemping & Matthias, 2018 ).

Correlation plots. Note: Non-significant bivariate correlations in panel A are presented as blank cells. In panel B, the Pearson correlation approximates point biserial correlation and was used to represent the bivariate associations

Interim discussion

Tabooness was moderately predicted (r 2 = .43) from a linear algorithm of nine variables. Arousal and valence contributed the greatest weight to the model, although a range of additional predictors were also statistically significant. Taboo words are slightly more abstract than concrete and more often connote body parts, bodily acts, gender, and/or disease. Obstruence was the only statistically significant word form/phonological predictor of tabooness, accounting for minimal variance (lmg < 0.01). There was no evidence for contributions of syllable structure or word length to support intuitions of phonaesthesia or the “four-letter-word” designation. One possible reason for the lack of an observed word length effect is the inclusion of compound words (e.g., cocksucker). We examine this specific subset of the taboo lexicon further below.

Experiment 2: Interactivity between form and meaning in taboo compounding

We examined a potential source of emergent tabooness when combining extant taboo words (e.g., shit) with common nouns (e.g., gibbon) to form novel compounds (e.g., shitgibbon). Participants evaluated the subjective quality of novel taboo and common noun combinations via Likert-scale ratings (e.g., ass-rocket [plausible] vs. ass-arm [implausible]). We examined the quality of novel taboo compound words when participants made unconstrained judgments (i.e., rate the extent to which this word combines with any curse word to form a new curse word), and an exploratory measure of combinations to specified anchors (i.e., fuck, shit). We then conducted a multiple regression to examine prediction of the quality of taboo-word compounding.

Participants included a combination of neurotypical young adults (n = 25) from Temple University who completed the study in the laboratory supplemented with MTurk raters (n = 115). For the final analyses, we excluded 17 participants who showed minimal variability in their responses (see rationale to follow). Participants completed ratings for the quality of common nouns combined with any possible taboo word (i.e., unconstrained). Footnote 3 The final sample included 87 adults with a mean age of 35.6 ( SD = 8.5, range = 18–46); sex distribution was 45F/42M. Participants were nominally financially compensated and provided written informed consent. Participants were additionally forewarned that they would be making judgments of taboo words.

We initially searched the MRC Psycholinguistic Database (Coltheart, 1981 ) for common nouns, limiting output by part-of-speech (i.e., noun only) with a minimum concreteness threshold of > 560 on a 100–700 scale. From this initial list (N = 1,026) we eliminated homophones, polysemes, and low-frequency nouns using a frequency threshold of 5 per million via the SUBTLEX US database (Brysbaert & New, 2009 ). Finally, we eliminated common nouns that form existing taboo compounds (e.g., hat, hole , head). These procedures netted a corpus of frequent and concrete English nouns (N = 487). Table 4 reflects psycholinguistic attributes of the stimulus set. This corpus is freely available for use via the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/uc8k4 ).

Experimental procedures

Participants evaluated plausibility of each common noun (e.g., door) as part of a taboo compound (e.g., assdoor). We obtained these ratings via Qualtrics software (Qualtrics Inc., Provo UT) using a Likert-scale format. In the primary analysis, participants rated the quality of novel taboo words with no specified comparison anchor. That is, participants were free to choose any taboo word they felt paired well with a given common noun in either initial (e.g., assdoor) or final position (e.g., doorass). Likert scales ranged from 1 (very poor) through 4 (neutral) to 7 (outstanding). Footnote 4 Stimuli were fully randomized. The software automatically prompted participants to complete all choices. Participants were given unlimited time to complete the survey, with most completing within 20 min.

Phonological predictors included length in letters, length in syllables, and orthographic neighborhood density (Marian, Bartolotti, Chabal, & Shook, 2012 ). Two independent raters coded the following phonological variables: syllable complexity (ratio of syllables with consonant clusters to total number of syllables), number of closed syllables (similarly normalized for length), and consonant obstruence (ratio of the total number of stop and affricate consonants to length in syllables). Rater agreement was 96.8% for the phonological predictors. Two additional independent raters coded membership in the following semantic categories: animate, manufactured artifact, receptacle, body part, vehicle, human dwelling, profession. Initial rater agreement was 95.5%. Raters then reconvened and resolved item-level disagreements.

Stimuli with ratings for valence, dominance, and physiological arousal drawn from Warriner, Kuperman, and Brysbaert ( 2013 ) were included as semantic predictors.

We conducted an item-level multiple regression with each word as an independent observation. The dependent variable was quality of emergent profanity as gleaned from the average rating for each item across participants.

We eliminated data from participants who completed the survey either with restricted variability (e.g., all 1’s or 4’s) and/or or too rapidly (n = 17). Table 5 summarizes results of the regression.

The model was statistically significant [F(20,460) = 8.59, p < .001], accounting for 24.03% of the variance in the tabooness judgments (r 2 = .27, adjusted R 2 = .24). Statistically significant phonological predictors included syllables-per-word (B = -.22, p < .05) and consonant obstruence (B = .18, p < .01), confirming that participants judged shorter words with more stop consonants as better candidates for novel taboo terms. In addition to word form, participants were sensitive to semantic variables including emotional valence (B = -.13, p < .01), physiological arousal (B = .12, p < .01), body part (B = .28, p < .05), receptacle (B = .23, p < .05), animacy (B = .66, p < .01), and profession (B = -.79, p < .01).

The five strongest candidates for taboo compounding per rated quality included: sack, trash, pig, rod, and mouth. The five least acceptable candidates were fireplace, restaurant, tennis, newspaper, and physician.

English is rife with taboo terms formed through combinatorial processes with religious terms (e.g., goddamn) and other extant taboo words ( Hughes, 1998 ; Mohr, 2013 ). In this experiment, we investigated this idiosyncratic propensity for common noun compounding. There are many such examples in common usage today (e.g., shithead, asshat, clusterfuck), and compounding appears to be a legitimate source of new words. We explored why some common nouns form effective new curse words (e.g., shithead), whereas others (e.g., shitarm) do not. It has been suggested that taboo words tend to denote negative concepts while simultaneously having phonological structures that mark sound-symbolic patterns of aggressive and/or unpleasant sounds (Bergen, 2016 ). We hypothesized that both of these factors (form and meaning) interact to predict the quality of emergent taboo speech, and this was indeed the case.

The data suggest that taboo compounding is a non-random process and that the quality of novel taboo compounding is to an extent predictable by a simple linear model. This compounding process did, however, differ in several important respects relative to the single-word regression data in Experiment 1 . First, participants endorsed shorter words, words with many similar sounding neighbors, and words with higher levels of obstruance (e.g., abrupt stoppage of air during articulation) as superior candidates for taboo compounding. Second, prediction was optimized by a linear combination of these formal factors with semantic variables such as whether a word denoted a profession, dwelling, or receptacle.

It is unclear how the linguistic rules governing taboo word compounding (e.g., catdick) diverge from non-taboo compounding (e.g., catfish). We know of no previous neuropsychological reports of excessive cursing characterized by either the production or the spontaneous generation of noun compounds. Morphological decomposition of non-taboo compound words (cat + fish = catfish) is a well-studied phenomenon in language disorders such as aphasia (Rastle & Davis, 2008 ). However, the extent to which the constituent morphemes of taboo compound words are similarly dissociable remains an open question.

General discussion

We conducted two experiments examining whether tabooness can be algorithmically predicted from the form and meaning of a particular word. The data suggest that American English follows a recipe for tabooness both for single words and to a lesser extent for compound words. Several factors are strongly associated with tabooness. These include physiological arousal and negative emotional valence, as well as semantic factors such as gender, body relations, and disease. There was less evidence for an effect of word length among single words, possibly because of the inclusion of a diverse range of compound words (e.g., cocksucker, motherfucker), all of which counter viability of the “four-letter-word” phenomenon.

Following Janschewitz ( 2008 ), we focused on an interaction between high arousal and negative emotional valence. These factors do appear to play a deterministic role in predicting tabooness, but there exists a range of additional moderating variables. Figure 1 illustrates overlap between taboo words and non-taboo words that share space within the negative-valence and high-arousal quadrant. Words such as welfare , abortion , and sodomy have all the necessary ingredients for tabooness, and indeed appear as some of the more taboo terms in our distribution. Yet, unlike words that are universally regarded as taboo, this particular class of descriptive terms is acceptable within certain public settings (e.g., scientific and/or instructional discourse). By tracing etymology and usage statistics over time, it may be possible to observe an arc as negatively valent and highly arousing words shift from descriptive to taboo.

Concluding remarks and future directions

Our findings suggest several promising future directions for the psychology and neurology of taboo-word processing. One application involves populations who experience excessive and/or uncontrolled taboo-word usage as a result of neurological etiologies, including severe expressive aphasia, Tourette Syndrome, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and the behavioral variant of frontotemporal degeneration (bvFTD). There are some commonalities but also many differences in the respective neuropathologies that underlie coprolalia and the excessive use of profanity in these populations. Hemispheric differences in valence, arousal, propositional/non-propositional language representation, theory of mind, and general cognitive control are all possible etiologies of excessive taboo-word usage. These variables likely interact with premorbid individual differences in both receptive and expressive use of taboo words. For people who experience debilitating social consequences of uncontrolled taboo-word usage, algorithmic prediction of tabooness may hold promise for tailoring intervention. Rather than punish or prohibit the output, a focus on precipitating factors (e.g., modulating arousal, sensitivity to listener attitudes) may improve communicative outcomes.

Open Science Statement

Stimuli, computer scripts, and scale wording are freely available for download and use at https://osf.io/uc8k4

Tabooness rating instructions are available in online Appendix A (accessible via the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/uc8k4 )

Semantic coding instructions are available in online Appendix B ( https://osf.io/uc8k4 )

We also conducted an exploratory analysis anchoring ratings to two specific taboo words, fuck (Condition 2) and shit (Condition 3). These results are summarized in Table 5 and Appendix D ( https://osf.io/uc8k4 )

Scale instructions for combinatorial tabooness are available in online Appendix C ( https://osf.io/uc8k4 ).

Bergen, B. K. (2016). What the F: What Swearing Reveals About Our Language, Our Brains, and Ourselves . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Google Scholar