Scaffolding Methods for Research Paper Writing

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

Students will use scaffolding to research and organize information for writing a research paper. A research paper scaffold provides students with clear support for writing expository papers that include a question (problem), literature review, analysis, methodology for original research, results, conclusion, and references. Students examine informational text, use an inquiry-based approach, and practice genre-specific strategies for expository writing. Depending on the goals of the assignment, students may work collaboratively or as individuals. A student-written paper about color psychology provides an authentic model of a scaffold and the corresponding finished paper. The research paper scaffold is designed to be completed during seven or eight sessions over the course of four to six weeks.

Featured Resources

- Research Paper Scaffold : This handout guides students in researching and organizing the information they need for writing their research paper.

- Inquiry on the Internet: Evaluating Web Pages for a Class Collection : Students use Internet search engines and Web analysis checklists to evaluate online resources then write annotations that explain how and why the resources will be valuable to the class.

From Theory to Practice

- Research paper scaffolding provides a temporary linguistic tool to assist students as they organize their expository writing. Scaffolding assists students in moving to levels of language performance they might be unable to obtain without this support.

- An instructional scaffold essentially changes the role of the teacher from that of giver of knowledge to leader in inquiry. This relationship encourages creative intelligence on the part of both teacher and student, which in turn may broaden the notion of literacy so as to include more learning styles.

- An instructional scaffold is useful for expository writing because of its basis in problem solving, ownership, appropriateness, support, collaboration, and internalization. It allows students to start where they are comfortable, and provides a genre-based structure for organizing creative ideas.

- In order for students to take ownership of knowledge, they must learn to rework raw information, use details and facts, and write.

- Teaching writing should involve direct, explicit comprehension instruction, effective instructional principles embedded in content, motivation and self-directed learning, and text-based collaborative learning to improve middle school and high school literacy.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 2. Students read a wide range of literature from many periods in many genres to build an understanding of the many dimensions (e.g., philosophical, ethical, aesthetic) of human experience.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

Computers with Internet access and printing capability

- Research Paper Scaffold

- Example Research Paper Scaffold

- Example Student Research Paper

- Internet Citation Checklist

- Research Paper Scoring Rubric

- Permission Form (optional)

Preparation

Student objectives.

Students will

- Formulate a clear thesis that conveys a perspective on the subject of their research

- Practice research skills, including evaluation of sources, paraphrasing and summarizing relevant information, and citation of sources used

- Logically group and sequence ideas in expository writing

- Organize and display information on charts, maps, and graphs

Session 1: Research Question

You should approve students’ final research questions before Session 2. You may also wish to send home the Permission Form with students, to make parents aware of their child’s research topic and the project due dates.

Session 2: Literature Review—Search

Prior to this session, you may want to introduce or review Internet search techniques using the lesson Inquiry on the Internet: Evaluating Web Pages for a Class Collection . You may also wish to consult with the school librarian regarding subscription databases designed specifically for student research, which may be available through the school or public library. Using these types of resources will help to ensure that students find relevant and appropriate information. Using Internet search engines such as Google can be overwhelming to beginning researchers.

Session 3: Literature Review—Notes

Students need to bring their articles to this session. For large classes, have students highlight relevant information (as described below) and submit the articles for assessment before beginning the session.

Checking Literature Review entries on the same day is best practice, as it gives both you and the student time to plan and address any problems before proceeding. Note that in the finished product this literature review section will be about six paragraphs, so students need to gather enough facts to fit this format.

Session 4: Analysis

Session 5: original research.

Students should design some form of original research appropriate to their topics, but they do not necessarily have to conduct the experiments or surveys they propose. Depending on the appropriateness of the original research proposals, the time involved, and the resources available, you may prefer to omit the actual research or use it as an extension activity.

Session 6: Results (optional)

Session 7: conclusion, session 8: references and writing final draft, student assessment / reflections.

- Observe students’ participation in the initial stages of the Research Paper Scaffold and promptly address any errors or misconceptions about the research process.

- Observe students and provide feedback as they complete each section of the Research Paper Scaffold.

- Provide a safe environment where students will want to take risks in exploring ideas. During collaborative work, offer feedback and guidance to those who need encouragement or require assistance in learning cooperation and tolerance.

- Involve students in using the Research Paper Scoring Rubric for final evaluation of the research paper. Go over this rubric during Session 8, before they write their final drafts.

- Strategy Guides

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Four Strategies for Effective Writing Instruction

- Share article

(This is the first post in a two-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is the single most effective instructional strategy you have used to teach writing?

Teaching and learning good writing can be a challenge to educators and students alike.

The topic is no stranger to this column—you can see many previous related posts at Writing Instruction .

But I don’t think any of us can get too much good instructional advice in this area.

Today, Jenny Vo, Michele Morgan, and Joy Hamm share wisdom gained from their teaching experience.

Before I turn over the column to them, though, I’d like to share my favorite tool(s).

Graphic organizers, including writing frames (which are basically more expansive sentence starters) and writing structures (which function more as guides and less as “fill-in-the-blanks”) are critical elements of my writing instruction.

You can see an example of how I incorporate them in my seven-week story-writing unit and in the adaptations I made in it for concurrent teaching.

You might also be interested in The Best Scaffolded Writing Frames For Students .

Now, to today’s guests:

‘Shared Writing’

Jenny Vo earned her B.A. in English from Rice University and her M.Ed. in educational leadership from Lamar University. She has worked with English-learners during all of her 24 years in education and is currently an ESL ISST in Katy ISD in Katy, Texas. Jenny is the president-elect of TexTESOL IV and works to advocate for all ELs:

The single most effective instructional strategy that I have used to teach writing is shared writing. Shared writing is when the teacher and students write collaboratively. In shared writing, the teacher is the primary holder of the pen, even though the process is a collaborative one. The teacher serves as the scribe, while also questioning and prompting the students.

The students engage in discussions with the teacher and their peers on what should be included in the text. Shared writing can be done with the whole class or as a small-group activity.

There are two reasons why I love using shared writing. One, it is a great opportunity for the teacher to model the structures and functions of different types of writing while also weaving in lessons on spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

It is a perfect activity to do at the beginning of the unit for a new genre. Use shared writing to introduce the students to the purpose of the genre. Model the writing process from beginning to end, taking the students from idea generation to planning to drafting to revising to publishing. As you are writing, make sure you refrain from making errors, as you want your finished product to serve as a high-quality model for the students to refer back to as they write independently.

Another reason why I love using shared writing is that it connects the writing process with oral language. As the students co-construct the writing piece with the teacher, they are orally expressing their ideas and listening to the ideas of their classmates. It gives them the opportunity to practice rehearsing what they are going to say before it is written down on paper. Shared writing gives the teacher many opportunities to encourage their quieter or more reluctant students to engage in the discussion with the types of questions the teacher asks.

Writing well is a skill that is developed over time with much practice. Shared writing allows students to engage in the writing process while observing the construction of a high-quality sample. It is a very effective instructional strategy used to teach writing.

‘Four Square’

Michele Morgan has been writing IEPs and behavior plans to help students be more successful for 17 years. She is a national-board-certified teacher, Utah Teacher Fellow with Hope Street Group, and a special education elementary new-teacher specialist with the Granite school district. Follow her @MicheleTMorgan1:

For many students, writing is the most dreaded part of the school day. Writing involves many complex processes that students have to engage in before they produce a product—they must determine what they will write about, they must organize their thoughts into a logical sequence, and they must do the actual writing, whether on a computer or by hand. Still they are not done—they must edit their writing and revise mistakes. With all of that, it’s no wonder that students struggle with writing assignments.

In my years working with elementary special education students, I have found that writing is the most difficult subject to teach. Not only do my students struggle with the writing process, but they often have the added difficulties of not knowing how to spell words and not understanding how to use punctuation correctly. That is why the single most effective strategy I use when teaching writing is the Four Square graphic organizer.

The Four Square instructional strategy was developed in 1999 by Judith S. Gould and Evan Jay Gould. When I first started teaching, a colleague allowed me to borrow the Goulds’ book about using the Four Square method, and I have used it ever since. The Four Square is a graphic organizer that students can make themselves when given a blank sheet of paper. They fold it into four squares and draw a box in the middle of the page. The genius of this instructional strategy is that it can be used by any student, in any grade level, for any writing assignment. These are some of the ways I have used this strategy successfully with my students:

* Writing sentences: Students can write the topic for the sentence in the middle box, and in each square, they can draw pictures of details they want to add to their writing.

* Writing paragraphs: Students write the topic sentence in the middle box. They write a sentence containing a supporting detail in three of the squares and they write a concluding sentence in the last square.

* Writing short essays: Students write what information goes in the topic paragraph in the middle box, then list details to include in supporting paragraphs in the squares.

When I gave students writing assignments, the first thing I had them do was create a Four Square. We did this so often that it became automatic. After filling in the Four Square, they wrote rough drafts by copying their work off of the graphic organizer and into the correct format, either on lined paper or in a Word document. This worked for all of my special education students!

I was able to modify tasks using the Four Square so that all of my students could participate, regardless of their disabilities. Even if they did not know what to write about, they knew how to start the assignment (which is often the hardest part of getting it done!) and they grew to be more confident in their writing abilities.

In addition, when it was time to take the high-stakes state writing tests at the end of the year, this was a strategy my students could use to help them do well on the tests. I was able to give them a sheet of blank paper, and they knew what to do with it. I have used many different curriculum materials and programs to teach writing in the last 16 years, but the Four Square is the one strategy that I have used with every writing assignment, no matter the grade level, because it is so effective.

‘Swift Structures’

Joy Hamm has taught 11 years in a variety of English-language settings, ranging from kindergarten to adult learners. The last few years working with middle and high school Newcomers and completing her M.Ed in TESOL have fostered stronger advocacy in her district and beyond:

A majority of secondary content assessments include open-ended essay questions. Many students falter (not just ELs) because they are unaware of how to quickly organize their thoughts into a cohesive argument. In fact, the WIDA CAN DO Descriptors list level 5 writing proficiency as “organizing details logically and cohesively.” Thus, the most effective cross-curricular secondary writing strategy I use with my intermediate LTELs (long-term English-learners) is what I call “Swift Structures.” This term simply means reading a prompt across any content area and quickly jotting down an outline to organize a strong response.

To implement Swift Structures, begin by displaying a prompt and modeling how to swiftly create a bubble map or outline beginning with a thesis/opinion, then connecting the three main topics, which are each supported by at least three details. Emphasize this is NOT the time for complete sentences, just bulleted words or phrases.

Once the outline is completed, show your ELs how easy it is to plug in transitions, expand the bullets into detailed sentences, and add a brief introduction and conclusion. After modeling and guided practice, set a 5-10 minute timer and have students practice independently. Swift Structures is one of my weekly bell ringers, so students build confidence and skill over time. It is best to start with easy prompts where students have preformed opinions and knowledge in order to focus their attention on the thesis-topics-supporting-details outline, not struggling with the rigor of a content prompt.

Here is one easy prompt example: “Should students be allowed to use their cellphones in class?”

Swift Structure outline:

Thesis - Students should be allowed to use cellphones because (1) higher engagement (2) learning tools/apps (3) gain 21st-century skills

Topic 1. Cellphones create higher engagement in students...

Details A. interactive (Flipgrid, Kahoot)

B. less tempted by distractions

C. teaches responsibility

Topic 2. Furthermore,...access to learning tools...

A. Google Translate description

B. language practice (Duolingo)

C. content tutorials (Kahn Academy)

Topic 3. In addition,...practice 21st-century skills…

Details A. prep for workforce

B. access to information

C. time-management support

This bare-bones outline is like the frame of a house. Get the structure right, and it’s easier to fill in the interior decorating (style, grammar), roof (introduction) and driveway (conclusion). Without the frame, the roof and walls will fall apart, and the reader is left confused by circuitous rubble.

Once LTELs have mastered creating simple Swift Structures in less than 10 minutes, it is time to introduce complex questions similar to prompts found on content assessments or essays. Students need to gain assurance that they can quickly and logically explain and justify their opinions on multiple content essays without freezing under pressure.

Thanks to Jenny, Michele, and Joy for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Our 2020-21 Writing Curriculum for Middle and High School

A flexible, seven-unit program based on the real-world writing found in newspapers, from editorials and reviews to personal narratives and informational essays.

Update, Aug. 3, 2023: Find our 2023-24 writing curriculum here.

Our 2019-20 Writing Curriculum is one of the most popular new features we’ve ever run on this site, so, of course, we’re back with a 2020-21 version — one we hope is useful whether you’re teaching in person , online , indoors , outdoors , in a pod , as a homeschool , or in some hybrid of a few of these.

The curriculum detailed below is both a road map for teachers and an invitation to students. For teachers, it includes our writing prompts, mentor texts, contests and lesson plans, and organizes them all into seven distinct units. Each focuses on a different genre of writing that you can find not just in The Times but also in all kinds of real-world sources both in print and online.

But for students, our main goal is to show young people they have something valuable to say, and to give those voices a global audience. That’s always been a pillar of our site, but this year it is even more critical. The events of 2020 will define this generation, and many are living through them isolated from their ordinary communities, rituals and supports. Though a writing curriculum can hardly make up for that, we hope that it can at least offer teenagers a creative outlet for making sense of their experiences, and an enthusiastic audience for the results. Through the opportunities for publication woven throughout each unit, we want to encourage students to go beyond simply being media consumers to become creators and contributors themselves.

So have a look, and see if you can find a way to include any of these opportunities in your curriculum this year, whether to help students document their lives, tell stories, express opinions, investigate ideas, or analyze culture. We can’t wait to hear what your students have to say!

Each unit includes:

Writing prompts to help students try out related skills in a “low stakes” way.

We publish two writing prompts every school day, and we also have thematic collections of more than 1,000 prompts published in the past. Your students might consider responding to these prompts on our site and using our public forums as a kind of “rehearsal space” for practicing voice and technique.

Daily opportunities to practice writing for an authentic audience.

If a student submits a comment on our site, it will be read by Times editors, who approve each one before it gets published. Submitting a comment also gives students an audience of fellow teenagers from around the world who might read and respond to their work. Each week, we call out our favorite comments and honor dozens of students by name in our Thursday “ Current Events Conversation ” feature.

Guided practice with mentor texts .

Each unit we publish features guided practice lessons, written directly to students, that help them observe, understand and practice the kinds of “craft moves” that make different genres of writing sing. From how to “show not tell” in narratives to how to express critical opinions , quote or paraphrase experts or craft scripts for podcasts , we have used the work of both Times journalists and the teenage winners of our contests to show students techniques they can emulate.

“Annotated by the Author” commentaries from Times writers — and teenagers.

As part of our Mentor Texts series , we’ve been asking Times journalists from desks across the newsroom to annotate their articles to let students in on their writing, research and editing processes, and we’ll be adding more for each unit this year. Whether it’s Science writer Nicholas St. Fleur on tiny tyrannosaurs , Opinion writer Aisha Harris on the cultural canon , or The Times’s comics-industry reporter, George Gene Gustines, on comic books that celebrate pride , the idea is to demystify journalism for teenagers. This year, we’ll be inviting student winners of our contests to annotate their work as well.

A contest that can act as a culminating project .

Over the years we’ve heard from many teachers that our contests serve as final projects in their classes, and this curriculum came about in large part because we want to help teachers “plan backwards” to support those projects.

All contest entries are considered by experts, whether Times journalists, outside educators from partner organizations, or professional practitioners in a related field. Winning means being published on our site, and, perhaps, in the print edition of The New York Times.

Webinars and our new professional learning community (P.L.C.).

For each of the seven units in this curriculum, we host a webinar featuring Learning Network editors as well as teachers who use The Times in their classrooms. Our webinars introduce participants to our many resources and provide practical how-to’s on how to use our prompts, mentor texts and contests in the classroom.

New for this school year, we also invite teachers to join our P.L.C. on teaching writing with The Times , where educators can share resources, strategies and inspiration about teaching with these units.

Below are the seven units we will offer in the 2020-21 school year.

September-October

Unit 1: Documenting Teenage Lives in Extraordinary Times

This special unit acknowledges both the tumultuous events of 2020 and their outsized impact on young people — and invites teenagers to respond creatively. How can they add their voices to our understanding of what this historic year will mean for their generation?

Culminating in our Coming of Age in 2020 contest, the unit helps teenagers document and respond to what it’s been like to live through what one Times article describes as “a year of tragedy, of catastrophe, of upheaval, a year that has inflicted one blow after another, a year that has filled the morgues, emptied the schools, shuttered the workplaces, swelled the unemployment lines and polarized the electorate.”

A series of writing prompts, mentor texts and a step-by-step guide will help them think deeply and analytically about who they are, how this year has impacted them, what they’d like to express as a result, and how they’d like to express it. How might they tell their unique stories in ways that feel meaningful and authentic, whether those stories are serious or funny, big or small, raw or polished?

Though the contest accepts work across genres — via words and images, video and audio — all students will also craft written artist’s statements for each piece they submit. In addition, no matter what genre of work students send in, the unit will use writing as a tool throughout to help students brainstorm, compose and edit. And, of course, this work, whether students send it to us or not, is valuable far beyond the classroom: Historians, archivists and museums recommend that we all document our experiences this year, if only for ourselves.

October-November

Unit 2: The Personal Narrative

While The Times is known for its award-winning journalism, the paper also has a robust tradition of publishing personal essays on topics like love , family , life on campus and navigating anxiety . And on our site, our daily writing prompts have long invited students to tell us their stories, too. Our 2019 collection of 550 Prompts for Narrative and Personal Writing is a good place to start, though we add more every week during the school year.

In this unit we draw on many of these resources, plus some of the 1,000-plus personal essays from the Magazine’s long-running Lives column , to help students find their own “short, memorable stories ” and tell them well. Our related mentor-text lessons can help them practice skills like writing with voice , using details to show rather than tell , structuring a narrative arc , dropping the reader into a scene and more. This year, we’ll also be including mentor text guided lessons that use the work of the 2019 student winners.

As a final project, we invite students to send finished stories to our Second Annual Personal Narrative Writing Contest .

DECEMBER-January

Unit 3: The Review

Book reports and literary essays have long been staples of language arts classrooms, but this unit encourages students to learn how to critique art in other genres as well. As we point out, a cultural review is, of course, a form of argumentative essay. Your class might be writing about Lizzo or “ Looking for Alaska ,” but they still have to make claims and support them with evidence. And, just as they must in a literature essay, they have to read (or watch, or listen to) a work closely; analyze it and understand its context; and explain what is meaningful and interesting about it.

In our Mentor Texts series , we feature the work of Times movie , restaurant , book and music critics to help students understand the elements of a successful review. In each one of these guided lessons, we also spotlight the work of teenage contest winners from previous years.

As a culminating project, we invite students to send us their own reviews of a book, movie, restaurant, album, theatrical production, video game, dance performance, TV show, art exhibition or any other kind of work The Times critiques.

January-February

Unit 4: Informational Writing

Informational writing is the style of writing that dominates The New York Times as well as any other traditional newspaper you might read, and in this unit we hope to show students that it can be every bit as engaging and compelling to read and to write as other genres. Via thousands of articles a month — from front-page reporting on politics to news about athletes in Sports, deep data dives in The Upshot, recipes in Cooking, advice columns in Style and long-form investigative pieces in the magazine — Times journalists find ways to experiment with the genre to intrigue and inform their audiences.

This unit invites students to take any STEM-related discovery, process or idea that interests them and write about it in a way that makes it understandable and engaging for a general audience — but all the skills we teach along the way can work for any kind of informational writing. Via our Mentor Texts series, we show them how to hook the reader from the start , use quotes and research , explain why a topic matters and more. This year we’ll be using the work of the 2020 student winners for additional mentor text lessons.

At the end of the unit, we invite teenagers to submit their own writing to our Second Annual STEM writing contest to show us what they’ve learned.

March-April

Unit 5: Argumentative Writing

The demand for evidence-based argumentative writing is now woven into school assignments across the curriculum and grade levels, and you couldn’t ask for better real-world examples than what you can find in The Times Opinion section .

This unit will, like our others, be supported with writing prompts, mentor-text lesson plans, webinars and more. We’ll also focus on the winning teenage writing we’ve received over the six years we’ve run our related contest.

At a time when media literacy is more important than ever, we also hope that our annual Student Editorial Contest can serve as a final project that encourages students to broaden their information diets with a range of reliable sources, and learn from a variety of perspectives on their chosen issue.

To help students working from home, we also have an Argumentative Unit for Students Doing Remote Learning .

Unit 6: Writing for Podcasts

Most of our writing units so far have all asked for essays of one kind or another, but this spring contest invites students to do what journalists at The Times do every day: make multimedia to tell a story, investigate an issue or communicate a concept.

Our annual podcast contest gives students the freedom to talk about anything they want in any form they like. In the past we’ve had winners who’ve done personal narratives, local travelogues, opinion pieces, interviews with community members, local investigative journalism and descriptions of scientific discoveries.

As with all our other units, we have supported this contest with great examples from The Times and around the web, as well as with mentor texts by teenagers that offer guided practice in understanding elements and techniques.

June-August

Unit 7: Independent Reading and Writing

At a time when teachers are looking for ways to offer students more “voice and choice,” this unit, based on our annual summer contest, offers both.

Every year since 2010 we have invited teenagers around the world to add The New York Times to their summer reading lists and, so far, 70,000 have. Every week for 10 weeks, we ask participants to choose something in The Times that has sparked their interest, then tell us why. At the end of the week, judges from the Times newsroom pick favorite responses, and we publish them on our site.

And we’ve used our Mentor Text feature to spotlight the work of past winners , explain why newsroom judges admired their thinking, and provide four steps to helping any student write better reader-responses.

Because this is our most open-ended contest — students can choose whatever they like, and react however they like — it has proved over the years to be a useful place for young writers to hone their voices, practice skills and take risks . Join us!

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, 5 methods to teach students how to do research papers.

When teaching students how to construct research papers, the scaffolding method is an effective option. This method allows students to research and then organize their information. The scaffold provides understandable support for expository papers. Students greatly benefit from having the majority of the research and proper structure in place before even starting the paper.

With well-prepared references, students are able to:

- Study informational text

- Practice strategies that are genre-specific for expository writing

- Use an inquiry-based approach

- Work individually

- Work collaboratively

The following tips and methodologies build off the initial preparation:

- Students formulate a logical thesis that expresses a perspective on their research subject.

- Students practice their research skills. This includes evaluating their sources, summarizing and paraphrasing significant information, and properly citing their sources.

- The students logically group and then sequence their ideas in expository writing.

- They should arrange and then display their information on maps, graphs and charts.

- A well-written exposition is focused on the topic and lists events in chronological order.

Formulating a research question

An example research paper scaffold and student research paper should be distributed to students. The teacher should examine these with the students, reading them aloud.

Using the example research paper, discuss briefly how a research paper answers a question. This example should help students see how a question can lead to a literature review, which leads to analysis, research, results and finally, a conclusion.

Give students a blank copy of the research paper Scaffold and explain that the procedures used in writing research papers follow each section of the scaffold. Each of those sections builds on the one before it; describe how each section will be addressed in future sessions.

Consider using Internet research lessons to help students understand how to research using the web.

Have students collect and print at least five articles to help them answer their research question. Students should use a highlighter to mark which sections pertain specifically to their question. This helps students remain focused on their research questions.

The five articles could offer differing options regarding their research questions. Be sure to inform students that their final paper will be much more interesting if it examines several different perspectives instead of just one.

Have students bring their articles to class. For a large class, teachers should have students highlight the relevant information in their articles and then submit them for assessment prior to the beginning of class.

Once identification is determined as accurate, students should complete the Literature Review section of the scaffold and list the important facts from their articles on the lines numbered one through five.

Students need to compare the information they have found to find themes.

Explain that creating a numbered list of potential themes, taken from different aspects proposed in the literature collected, can be used for analysis.

The student’s answer to the research question is the conclusion of the research paper. This section of the research paper needs to be just a few paragraphs. Students should include the facts supporting their answer from the literature review.

Students may want to use the conclusion section of their paper to point out the similarities and/or discrepancies in their findings. They may also want to suggest that further studies be done on the topic.

You may also like to read

- How to Use Reading to Teach ELL Students

- Web Research Skills: Teaching Your Students the Fundamentals

- How to Help Middle School Students Develop Research Skills

- Five Free Websites for Students to Build Research Skills

- How to Help High School Students with Career Research

- Students Evaluating Teachers: What Educators Need to Know

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Assessment Tools

- COVID-19 Teacher Toolkit: Resilience Through ...

- Online & Campus Master's in Education Leaders...

- Early Childhood Education: Resources, Theorie...

Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Teaching students to write good papers.

This module is designed to help you teach students to write good papers. You will find useful examples of activities that guide students through the writing process. This resource will be helpful for anyone working with students on research papers, book reviews, and other analytical essays. The Center for Teaching and Learning also has comprehensive writing resources featuring general writing tips, citation guidelines, model papers, and ways to get more help at Yale.

There are several steps TFs and faculty can take to prepare students to write good papers. If you are responsible for making writing assignments, remember that most students need to practice the basic elements of writing — purpose, argument, evidence, style — and that these skills are best practiced in shorter, focused assignments. Opt for shorter essays and papers throughout the semester in lieu of long, end-of-semester research papers. Build opportunities for revision and refinement into your assignments and lesson plans.

For each assignment, there are steps you can take to help students produce better writing . First, use strategies for making sure students understand the assignment. Use individual meetings, short, in-class writing exercises or small-group activities to make sure students can articulate what their paper will accomplish (describe, compare/contrast, explain, argue) and to what standard.

Second, guide students in selecting and analyzing primary and secondary source material. Use in-class activities to teach students: the difference between types of sources and their uses; strategies for evaluating a source and its value in a given argument; and examples of how to incorporate source material into an argument or other text with proper citation .

Finally, teach them to construct strong thesis statements and support their arguments with evidence. Use model documents to introduce students to strong, arguable statements. Give students practice developing statements from scratch and refining statements that lack importance or clarity . Ask students to analyze the relationship between thesis statements and supporting evidence in short essays. Teach them to use the active voice .

Students who have never gone through a thorough revision process are used to handing in and receiving poor grades on first drafts. These students will lack confidence in their ability to produce good writing. Do all you can to let your students experience good writing through revision. Require drafts of papers, or parts of papers, so students can learn to apply the standards of good writing to make their papers better. Have students read and comment on each other’s papers to give them practice reading for clarity, style, persuasiveness, etc.

By focusing on the process of writing, not just the product, you will help students write better papers and gain confidence along the way.

For those of you who work with teaching fellows, we also include an agenda for teaching these skills to others and a workshop evaluation form .

Downloads

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

Writing Consultations

For graduate students looking for expert advice on planning, drafting, and revising their research paper, dissertation, presentation, or any other writing project.

- Research Skills

50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills

Please note, I am no longer blogging and this post hasn’t updated since April 2020.

For a number of years, Seth Godin has been talking about the need to “ connect the dots” rather than “collect the dots” . That is, rather than memorising information, students must be able to learn how to solve new problems, see patterns, and combine multiple perspectives.

Solid research skills underpin this. Having the fluency to find and use information successfully is an essential skill for life and work.

Today’s students have more information at their fingertips than ever before and this means the role of the teacher as a guide is more important than ever.

You might be wondering how you can fit teaching research skills into a busy curriculum? There aren’t enough hours in the day! The good news is, there are so many mini-lessons you can do to build students’ skills over time.

This post outlines 50 ideas for activities that could be done in just a few minutes (or stretched out to a longer lesson if you have the time!).

Learn More About The Research Process

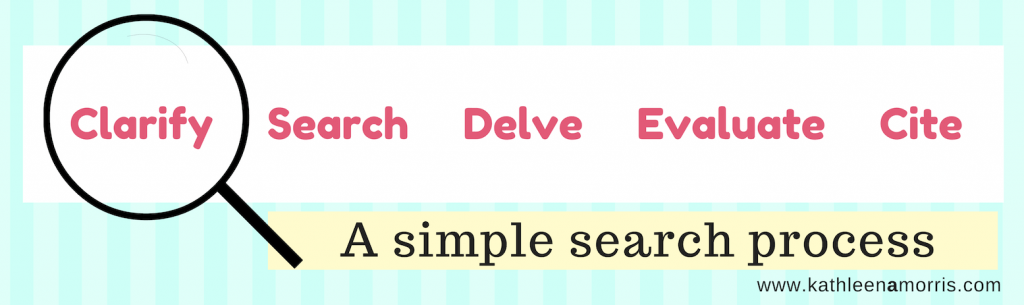

I have a popular post called Teach Students How To Research Online In 5 Steps. It outlines a five-step approach to break down the research process into manageable chunks.

This post shares ideas for mini-lessons that could be carried out in the classroom throughout the year to help build students’ skills in the five areas of: clarify, search, delve, evaluate , and cite . It also includes ideas for learning about staying organised throughout the research process.

Notes about the 50 research activities:

- These ideas can be adapted for different age groups from middle primary/elementary to senior high school.

- Many of these ideas can be repeated throughout the year.

- Depending on the age of your students, you can decide whether the activity will be more teacher or student led. Some activities suggest coming up with a list of words, questions, or phrases. Teachers of younger students could generate these themselves.

- Depending on how much time you have, many of the activities can be either quickly modelled by the teacher, or extended to an hour-long lesson.

- Some of the activities could fit into more than one category.

- Looking for simple articles for younger students for some of the activities? Try DOGO News or Time for Kids . Newsela is also a great resource but you do need to sign up for free account.

- Why not try a few activities in a staff meeting? Everyone can always brush up on their own research skills!

- Choose a topic (e.g. koalas, basketball, Mount Everest) . Write as many questions as you can think of relating to that topic.

- Make a mindmap of a topic you’re currently learning about. This could be either on paper or using an online tool like Bubbl.us .

- Read a short book or article. Make a list of 5 words from the text that you don’t totally understand. Look up the meaning of the words in a dictionary (online or paper).

- Look at a printed or digital copy of a short article with the title removed. Come up with as many different titles as possible that would fit the article.

- Come up with a list of 5 different questions you could type into Google (e.g. Which country in Asia has the largest population?) Circle the keywords in each question.

- Write down 10 words to describe a person, place, or topic. Come up with synonyms for these words using a tool like Thesaurus.com .

- Write pairs of synonyms on post-it notes (this could be done by the teacher or students). Each student in the class has one post-it note and walks around the classroom to find the person with the synonym to their word.

- Explore how to search Google using your voice (i.e. click/tap on the microphone in the Google search box or on your phone/tablet keyboard) . List the pros and cons of using voice and text to search.

- Open two different search engines in your browser such as Google and Bing. Type in a query and compare the results. Do all search engines work exactly the same?

- Have students work in pairs to try out a different search engine (there are 11 listed here ). Report back to the class on the pros and cons.

- Think of something you’re curious about, (e.g. What endangered animals live in the Amazon Rainforest?). Open Google in two tabs. In one search, type in one or two keywords ( e.g. Amazon Rainforest) . In the other search type in multiple relevant keywords (e.g. endangered animals Amazon rainforest). Compare the results. Discuss the importance of being specific.

- Similar to above, try two different searches where one phrase is in quotation marks and the other is not. For example, Origin of “raining cats and dogs” and Origin of raining cats and dogs . Discuss the difference that using quotation marks makes (It tells Google to search for the precise keywords in order.)

- Try writing a question in Google with a few minor spelling mistakes. What happens? What happens if you add or leave out punctuation ?

- Try the AGoogleADay.com daily search challenges from Google. The questions help older students learn about choosing keywords, deconstructing questions, and altering keywords.

- Explore how Google uses autocomplete to suggest searches quickly. Try it out by typing in various queries (e.g. How to draw… or What is the tallest…). Discuss how these suggestions come about, how to use them, and whether they’re usually helpful.

- Watch this video from Code.org to learn more about how search works .

- Take a look at 20 Instant Google Searches your Students Need to Know by Eric Curts to learn about “ instant searches ”. Try one to try out. Perhaps each student could be assigned one to try and share with the class.

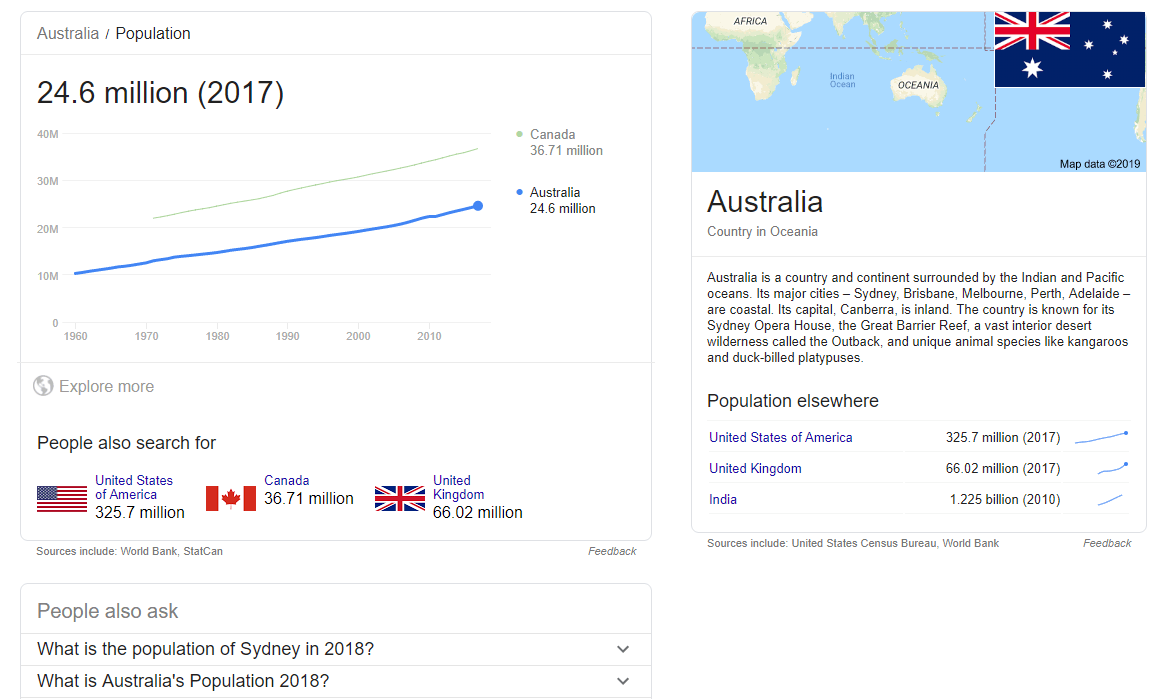

- Experiment with typing some questions into Google that have a clear answer (e.g. “What is a parallelogram?” or “What is the highest mountain in the world?” or “What is the population of Australia?”). Look at the different ways the answers are displayed instantly within the search results — dictionary definitions, image cards, graphs etc.

- Watch the video How Does Google Know Everything About Me? by Scientific American. Discuss the PageRank algorithm and how Google uses your data to customise search results.

- Brainstorm a list of popular domains (e.g. .com, .com.au, or your country’s domain) . Discuss if any domains might be more reliable than others and why (e.g. .gov or .edu) .

- Discuss (or research) ways to open Google search results in a new tab to save your original search results (i.e. right-click > open link in new tab or press control/command and click the link).

- Try out a few Google searches (perhaps start with things like “car service” “cat food” or “fresh flowers”). A re there advertisements within the results? Discuss where these appear and how to spot them.

- Look at ways to filter search results by using the tabs at the top of the page in Google (i.e. news, images, shopping, maps, videos etc.). Do the same filters appear for all Google searches? Try out a few different searches and see.

- Type a question into Google and look for the “People also ask” and “Searches related to…” sections. Discuss how these could be useful. When should you use them or ignore them so you don’t go off on an irrelevant tangent? Is the information in the drop-down section under “People also ask” always the best?

- Often, more current search results are more useful. Click on “tools” under the Google search box and then “any time” and your time frame of choice such as “Past month” or “Past year”.

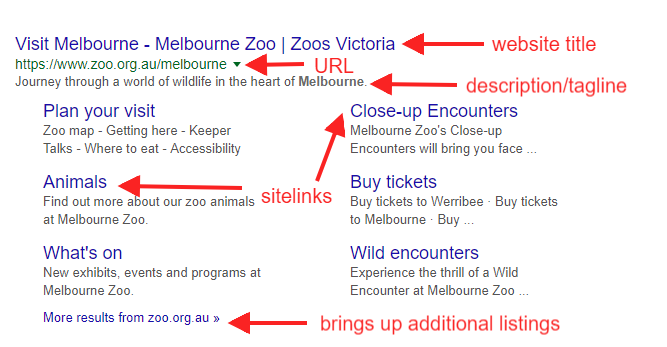

- Have students annotate their own “anatomy of a search result” example like the one I made below. Explore the different ways search results display; some have more details like sitelinks and some do not.

- Find two articles on a news topic from different publications. Or find a news article and an opinion piece on the same topic. Make a Venn diagram comparing the similarities and differences.

- Choose a graph, map, or chart from The New York Times’ What’s Going On In This Graph series . Have a whole class or small group discussion about the data.

- Look at images stripped of their captions on What’s Going On In This Picture? by The New York Times. Discuss the images in pairs or small groups. What can you tell?

- Explore a website together as a class or in pairs — perhaps a news website. Identify all the advertisements .

- Have a look at a fake website either as a whole class or in pairs/small groups. See if students can spot that these sites are not real. Discuss the fact that you can’t believe everything that’s online. Get started with these four examples of fake websites from Eric Curts.

- Give students a copy of my website evaluation flowchart to analyse and then discuss as a class. Read more about the flowchart in this post.

- As a class, look at a prompt from Mike Caulfield’s Four Moves . Either together or in small groups, have students fact check the prompts on the site. This resource explains more about the fact checking process. Note: some of these prompts are not suitable for younger students.

- Practice skim reading — give students one minute to read a short article. Ask them to discuss what stood out to them. Headings? Bold words? Quotes? Then give students ten minutes to read the same article and discuss deep reading.

All students can benefit from learning about plagiarism, copyright, how to write information in their own words, and how to acknowledge the source. However, the formality of this process will depend on your students’ age and your curriculum guidelines.

- Watch the video Citation for Beginners for an introduction to citation. Discuss the key points to remember.

- Look up the definition of plagiarism using a variety of sources (dictionary, video, Wikipedia etc.). Create a definition as a class.

- Find an interesting video on YouTube (perhaps a “life hack” video) and write a brief summary in your own words.

- Have students pair up and tell each other about their weekend. Then have the listener try to verbalise or write their friend’s recount in their own words. Discuss how accurate this was.

- Read the class a copy of a well known fairy tale. Have them write a short summary in their own words. Compare the versions that different students come up with.

- Try out MyBib — a handy free online tool without ads that helps you create citations quickly and easily.

- Give primary/elementary students a copy of Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Citation that matches their grade level (the guide covers grades 1 to 6). Choose one form of citation and create some examples as a class (e.g. a website or a book).

- Make a list of things that are okay and not okay to do when researching, e.g. copy text from a website, use any image from Google images, paraphrase in your own words and cite your source, add a short quote and cite the source.

- Have students read a short article and then come up with a summary that would be considered plagiarism and one that would not be considered plagiarism. These could be shared with the class and the students asked to decide which one shows an example of plagiarism .

- Older students could investigate the difference between paraphrasing and summarising . They could create a Venn diagram that compares the two.

- Write a list of statements on the board that might be true or false ( e.g. The 1956 Olympics were held in Melbourne, Australia. The rhinoceros is the largest land animal in the world. The current marathon world record is 2 hours, 7 minutes). Have students research these statements and decide whether they’re true or false by sharing their citations.

Staying Organised

- Make a list of different ways you can take notes while researching — Google Docs, Google Keep, pen and paper etc. Discuss the pros and cons of each method.

- Learn the keyboard shortcuts to help manage tabs (e.g. open new tab, reopen closed tab, go to next tab etc.). Perhaps students could all try out the shortcuts and share their favourite one with the class.

- Find a collection of resources on a topic and add them to a Wakelet .

- Listen to a short podcast or watch a brief video on a certain topic and sketchnote ideas. Sylvia Duckworth has some great tips about live sketchnoting

- Learn how to use split screen to have one window open with your research, and another open with your notes (e.g. a Google spreadsheet, Google Doc, Microsoft Word or OneNote etc.) .

All teachers know it’s important to teach students to research well. Investing time in this process will also pay off throughout the year and the years to come. Students will be able to focus on analysing and synthesizing information, rather than the mechanics of the research process.

By trying out as many of these mini-lessons as possible throughout the year, you’ll be really helping your students to thrive in all areas of school, work, and life.

Also remember to model your own searches explicitly during class time. Talk out loud as you look things up and ask students for input. Learning together is the way to go!

You Might Also Enjoy Reading:

How To Evaluate Websites: A Guide For Teachers And Students

Five Tips for Teaching Students How to Research and Filter Information

Typing Tips: The How and Why of Teaching Students Keyboarding Skills

8 Ways Teachers And Schools Can Communicate With Parents

10 Replies to “50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills”

Loving these ideas, thank you

This list is amazing. Thank you so much!

So glad it’s helpful, Alex! 🙂

Hi I am a student who really needed some help on how to reasearch thanks for the help.

So glad it helped! 🙂

seriously seriously grateful for your post. 🙂

So glad it’s helpful! Makes my day 🙂

How do you get the 50 mini lessons. I got the free one but am interested in the full version.

Hi Tracey, The link to the PDF with the 50 mini lessons is in the post. Here it is . Check out this post if you need more advice on teaching students how to research online. Hope that helps! Kathleen

Best wishes to you as you face your health battler. Hoping you’ve come out stronger and healthier from it. Your website is so helpful.

Comments are closed.

How to teach research skills to high school students: 12 tips

by mindroar | Oct 10, 2021 | blog | 0 comments

Teachers often find it difficult to decide how to teach research skills to high school students. You probably feel students should know how to do research by high school. But often students’ skills are lacking in one or more areas.

Today we’re not going to give you research skills lesson plans for high school. But we will give you 12 tips for how to teach research skills to high school students. Bonus, the tips will make it quick, fun, and easy.

One of my favorite ways of teaching research skills to high school students is to use the Crash Course Navigating Digital Information series.

The videos are free and short (between ten and fifteen minutes each). They cover information such as evaluating the trustworthiness of sources, using Wikipedia, lateral reading, and understanding how the source medium can affect the message.

Another thing I like to integrate into my lessons are the Crash Course Study Skills videos . Again, they’re free and short. Plus they are an easy way to refresh study skills such as:

- note-taking

- writing papers

- editing papers

- getting organized

- and studying for tests and exams.

If you’re ready to get started, we’ll give you links to great resources that you can integrate into your lessons. Because often students just need a refresh on a particular skill and not a whole semester-long course.

1. Why learn digital research skills?

Tip number one of how to teach research skills to high school students. Address the dreaded ‘why?’ questions upfront. You know the questions: Why do we have to do this? When am I ever going to use this?

If your students understand why they need good research skills and know that you will show them specific strategies to improve their skills, they are far more likely to buy into learning about how to research effectively.

An easy way to answer this question is that students spend so much time online. Some people spend almost an entire day online each week.

It’s amazing to have such easy access to information, unlike the pre-internet days. But there is far more misinformation and disinformation online.

A webpage, Facebook post, Instagram post, YouTube video, infographic, meme, gif, TikTok video (etc etc) can be created by just about anyone with a phone. And it’s easy to create them in a way that looks professional and legitimate.

This can make it hard for people to know what is real, true, evidence-based information and what is not.

The first Crash Course Navigating Digital Information video gets into the nitty-gritty of why we should learn strategies for evaluating the information we find (online or otherwise!).

An easy way to answer the ‘why’ questions your high schoolers will ask, the video is an excellent resource.

2. Teaching your students to fact check

Tip number two for teaching research skills to high school students is to teach your students concrete strategies for how to check facts.

It’s surprising how many students will hand in work with blatant factual errors. Errors they could have avoided had they done a quick fact check.

An easy way to broach this research skill in high school is to watch the second video in the Crash Course Navigating Digital Information series. It explains what fact-checking is, why people should do it, and how to make it a habit.

You can explain to your students that they’ll write better papers if they learn to fact-check. But they’ll also make better decisions if they make fact-checking a habit.

The video looks at why people are more likely to believe mis- or disinformation online. And it shows students a series of questions they can use to identify mis- or disinformation.

The video also discusses why it’s important to find a few generally reliable sources of information and to use those as a way to fact-check other online sources.

3. Teaching your students how and why to read laterally

This ties in with tip number 2 – teach concrete research strategies – but it is more specific. Fact-checking tends to be checking what claim sources are making, who is making the claim, and corroborating the claim with other sources.

But lateral reading is another concrete research skills strategy that you can teach to students. This skill helps students spot inaccurate information quickly and avoid wasting valuable research time.

One of the best (and easiest!) research skills for high school students to learn is how to read laterally. And teachers can demonstrate it so, so easily. As John Green says in the third Crash Course Navigating Digital Information video , just open another tab!

The video also shows students good websites to use to check hoaxes and controversial information.

Importantly, John Green also explains that students need a “toolbox” of strategies to assess sources of information. There’s not one magic source of information that is 100% accurate.

4. Teaching your students how to evaluate trustworthiness

Deciding who to trust online can be difficult even for those of us with lots of experience navigating online. And it is made even more difficult by how easy it now is to create a professional-looking websites.

This video shows students what to look for when evaluating trustworthiness. It also explains how to take bias, opinion, and political orientations into account when using information sources.

The video explains how reputable information sources gather reliable information (versus disreputable sources). And shows how reputable information sources navigate the situation when they discover their information is incorrect or misleading.

Students can apply the research skills from this video to news sources, novel excerpts, scholarly articles, and primary sources. Teaching students to look for bias, political orientation, and opinions within all sources is one of the most valuable research skills for high school students.

5. Teaching your students to use Wikipedia

Now, I know that Wikipedia can be the bane of your teacherly existence when you are reading essays. I know it can make you want to gouge your eyes out with a spoon when you read the same recycled article in thirty different essays. But, teaching students how to use Wikipedia as a jumping-off point is a useful skill.

Wikipedia is no less accurate than other online encyclopedia-type sources. And it often includes hyperlinks and references that students can check or use for further research. Plus it has handy-dandy warnings for inaccurate and contentious information.

Part of how to teach research skills to high school students is teaching them how to use general reference material such as encyclopedias for broad information. And then following up with how to use more detailed information such as primary and secondary sources.

The Crash Course video about Wikipedia is an easy way to show students how to use it more effectively.

6. Teaching your students to evaluate evidence

Another important research skill to teach high school students is how to evaluate evidence. This skill is important, both in their own and in others’ work.

An easy way to do this is the Crash Course video about evaluating evidence video. The short video shows students how to evaluate evidence using authorship, the evidence provided, and the relevance of the evidence.

It also gives examples of ways that evidence can be used to mislead. For example, it shows that simply providing evidence doesn’t mean that the evidence is quality evidence that supports the claim being made.

The video shows examples of evidence that is related to a topic, but irrelevant to the claim. Having an example of irrelevant evidence helps students understand the difference between related but irrelevant evidence and evidence that is relevant to the claim.

Finally, the video gives students questions that they can use to evaluate evidence.

7. Teaching your students to evaluate photos and videos

While the previous video about evidence looked at how to evaluate evidence in general, this video looks specifically at video and photographic evidence.

The video looks at how videos and photos can be manipulated to provide evidence for a claim. It suggests that seeking out the context for photos and videos is especially important as a video or photo is easy to misinterpret. This is especially the case if a misleading caption or surrounding information is provided.

The video also gives tools that students can use to discover hoaxes or fakes. Similarly, it encourages people to look for the origin of the photo or video to find the creator. And to then use that with contextual information to decide whether the photo or video is reliable evidence for a claim.

8. Teaching your students to evaluate data and infographics

Other sources of evidence that students (and adults!) often misinterpret or are misled by are data and infographics. Often people take the mere existence of statistics or other data as evidence for a claim instead of investigating further.

Again the Crash Course video suggests seeking out the source and context for data and infographics. It suggests that students often see data as neutral and irrefutable, but that data is inherently biased as it is created by humans.

The video gives a real-world example of how data can be manipulated as a source of evidence by showing how two different news sources represented global warming data.

9. Teaching your students how search engines work and why to use click restraint

Another video from the Crash Course Navigating Digital Information series is the video about how search engines work and click restraint . This video shows how search engines decide which information to list at the top of the search results. It also shows how search engines decide what information is relevant and of good quality.

The video gives search tips for using search engines to encourage the algorithms to return more reliable and accurate results.

This video is important when you are want to know how to teach research skills to high school students. This is because many students don’t understand why the first few results on a search are not necessarily the best information available.

10. Teach your students how to evaluate social media sources

One of the important research skills high school students need is to evaluate social media posts. Many people now get news and information from social media sites that have little to no oversight or editorial control. So, being able to evaluate posts for accuracy is key.

This video in the Crash Course Navigating Digital Information series also explains that social media sites are free to use because they make money from advertising. The advertising money comes from keeping people on the platform (and looking at the ads).

How do they keep people on the platform? By using algorithms that gather information about how long people spend on or react to different photos, posts and videos. Then, the algorithms will send viewers more content that is similar to the content that they view or interact with.

This prioritizes content that is controversial, shocking, engaging, attractive. It also reinforces the social norms of the audience members using the platform.

By teaching students how to combat the way that social media algorithms work, you can show them how to gather more reliable and relevant information in their everyday lives. Further, you help students work out if social media posts are relevant to (reliable for) their academic work.

11. Teaching your students how to cite sources

Another important research skill high school students need is how to accurately cite sources. A quick Google search turned up a few good free ideas:

- This lesson plan from the Brooklyn Library for grades 4-11. It aligns with the common core objectives and provides worksheets for students to learn to use MLA citation.

- This blog post about middle-school teacher Jody Passanini’s experiences trying to teach students in English and History how to cite sources both in-text and at the end with a reference list.

- This scavenger hunt lesson by 8th grade teacher on ReadWriteThink. It has a free printout asking students to prove assertions (which could be either student- or teacher-generated) with quotes from the text and a page number. It also has an example answer using the Catching Fire (Hunger Games) novel.

- The Chicago Manual of Style has this quick author-date citation guide .

- This page by Purdue Online Writing Lab has an MLA citation guide , as well as links to other citation guides such as APA.

If you are wanting other activities, a quick search of TPT showed these to be popular and well-received by other teachers:

- Laura Randazzo’s 9th edition MLA in-text and end-of-text citation activities

- Tracee Orman 8th edition MLA cheet sheet

- The Daring English Teacher’s MLA 8th edition citation powerpoint

12. Teaching your students to take notes

Another important skill to look at when considering how to teach research skills to high school students is whether they know how to take effective notes.

The Crash Course Study Skills note-taking video is great for this. It outlines three note-taking styles – the outline method, the Cornell method, and the mind map method. And it shows students how to use each of the methods.

This can help you start a conversation with your students about which styles of note-taking are most effective for different tasks.

For example, mind maps are great for seeing connections between ideas and brain dumps. The outline method is great for topics that are hierarchical. And the Cornell method is great for topics with lots of specific vocabulary.

Having these types of metacognitive discussions with your students helps them identify study and research strategies. It also helps them to learn which strategies are most effective in different situations.

Teaching research skills to high school students . . .

Doesn’t have to be

- time-consuming

The fantastic Crash Course Navigating Digital Information videos are a great way to get started if you are wondering how to teach research skills to high school students.

If you decide to use the videos in your class, you can buy individual worksheets if you have specific skills in mind. Or you can buy the full bundle if you think you’ll end up watching all of the videos.

Got any great tips for teaching research skills to high school students?

Head over to our Facebook or Instagram pages and let us know!

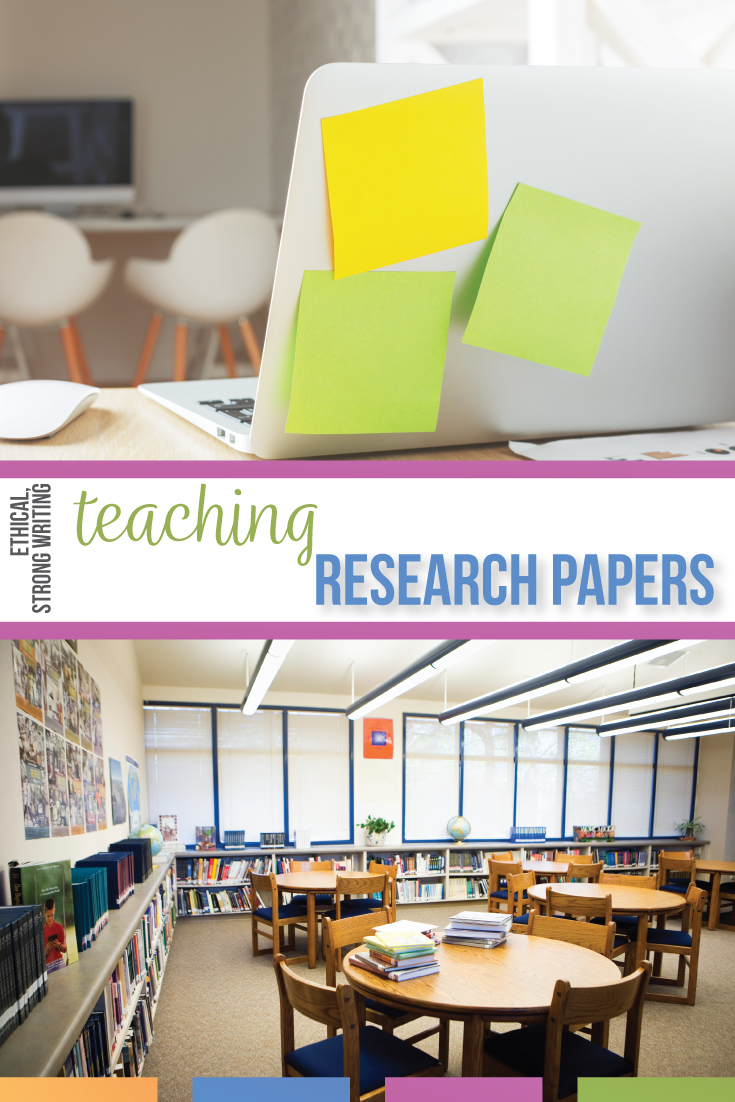

Teaching Research Papers with High School Students

Teaching research papers with high school students? Teaching students how to write a research paper is an important part of an ELA class. Here are guidelines to make this writing unit a success.

Lawyers, political organizers, advertisers, real estate agents: most jobs require ethical research and then a written report. As a citizen, I research concepts important to my community and family. As knowledge in our world grows, student will only have more reasons to be ethical digital citizens.

Providing students with a sustainable foundation is a humbling responsibility. Teachers know that teaching students how to write a research paper is important. While teaching students how to research, I share those sentiments with them. I want students to know I take research seriously, and my expectation is that they will as well. My research paper lesson plans take into account the seriousness of ethical research.

What is the best way to teach research papers to students?

The best way to teach research papers to students is by breaking down the process into manageable steps. Start with teaching them how to choose a topic, conduct research, and create an outline/list/graphic organizer. Then guide them in writing drafts, revising and editing their papers, and properly citing sources.

Even after teaching for a decade, I sometimes overwhelm myself with this duty. I handle teaching research papers with four ideas in my mind.

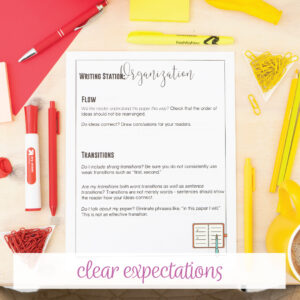

Provide clear expectations.

Idea one, be clear.

A feeling I always hated as a student was the unknown . Sure, part of the learning process is not knowing everything and making mistakes. I, as the teacher, don’t want to be the source of frustration though. I never want my classes to wander down a path that won’t advance them toward our end goal: a well-researched paper. Part of teaching research skills to high school students is providing clear expectations.

As writing in the ELA classroom becomes more digital, I simply give writers tools on our online learning platform. That way, I can remind them to check a certain section or page as we collaborate on their writing.

Give a writing overview.

Idea two, provide an overview.

Every teacher grades a little differently. Sometimes, terminology differs. Throw in the stress of research, and you might have a classroom of overwhelmed students. An overview before teaching research papers can relax everyone!

I start every writing unit with clear expectations, terminology, and goals. I cover a presentation with students, and then I upload it to Google Classroom. Students know to consult that presentation for clarity. Initially, covering the basics may seem wasteful, but it saves all of us time because students know my expectations.

Furthermore, parents and tutors appreciate my sharing that information. As students work independently (inside or outside of class), they can take it upon themselves to consult expectations. Their responsibility with this prepares them for their futures. Finally, having established that overview with students during virtual classes was invaluable.