Accessibility Tools

- Invert colors

- Dark contrast

- Light contrast

- Low saturation

- High saturation

- Highlight links

- Highlight headings

- Screen reader

- Keyword -->

Can’t get enough?

Feeding the beast

Current issue.

November 2024, no. 470

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

Please enable the javascript to submit this form

The Muse of History: The Ancient Greeks from the Enlightenment to the present by Oswyn Murray

Oswyn Murray’s book The Muse of History is subtitled ‘The Ancient Greeks from the Enlightenment to the present’, but this period of some three centuries represents virtually the whole of the modern historiography of Greece. The primary reason for this is one that is easily forgotten today: from the medieval to the early modern period, Greek civilisation, with its literature and art, was mainly understood from a Roman perspective. Even the gods were known by their adopted Latin names, and in an age when everyone who went to school could read and write Latin, a relatively small number were ever fluent in Greek.

The Holocaust and Australian Journalism: Reporting and reckoning by Fay Anderson

‘The Nazis are coming, Hurrah! Hurrah!’ wrote an excited young journalist, Ronald Selkirk Panton, to his parents the same month that Adolf Hitler was elected chancellor of Germany, the same month that Dachau was created, and the same year that the racial laws against Jews and other minority groups were enacted. Panton was one of a small but enthusiastic cohort of Australian journalists who went to Europe and filed stories about the Nazi dictatorship and the persecution of Jews. Most did not share Panton’s admiration for Hitler. Indeed, as Wilfred Burchett, one of the more political among them, later recalled, he found journalism about Hitler and Nazism elusive in Australia, amid ‘horrifying distortions’ of Hitler as a ‘man of peace’.

Three Wild Dogs and the Truth by Markus Zusak

Dogs have long been a feature of Markus Zusak’s fiction. His pre-fame trilogy of Young Adult novels, centring on brothers Cameron and Ruben Wolfe and their family, deployed the animal as a metaphor for tenaciousness. In the trilogy’s final book, When Dogs Cry (2001), Cameron and Ruben all but adopt Miffy, a Pomeranian whose scrappiness matches that of the brothers and whose death provides the book’s emotional fulcrum. There is a caffeinated hound in The Messenger (2002) and a clothesline-obsessed border collie in Bridge of Clay (2018). Even when, as in Zusak’s best-known work, The Book Thief (2006), dogs are not present, something about the way the author sees them – lovably rambunctious, all rough edges, chaos and, yes, doggedness – permeates the spirit of his two-legged characters.

Theory & Practice by Michelle de Kretser

How do we reconcile our ideals with the way we live our lives? What should we do when we discover that artists whom we revere turn out to be deeply flawed human beings? How do we continue to love and respect our mothers while acknowledging their shortcomings? Are desire and shame intrinsically linked? Which is the more powerful? These are some of the many issues Michelle de Kretser, twice winner of the Miles Franklin Literary Award (in 2013 for Questions of Travel and in 2018 for The Life to Come ) grapples with in her seventh novel, Theory & Practice.

Lower than the Angels: A history of sex and Christianity by Diarmaid MacCulloch

Christians so often have problems with sex these days. Australians saw this when, during the Marriage Law Postal Survey, the Anglican Archbishop of Sydney begged them to uphold a ‘biblical definition’ of marriage – if there were such a thing. Representatives of every denomination fret endlessly over their responsibility for enabling the sex offenders and abusers of children who were hidden in plain sight in their midst. That some do this even as they fulminate against overt sexual expression in the public sphere (the Paris Olympics opening ceremony anyone?) makes them seem even more out of touch.

Nexus: A brief history of information networks from the Stone Age to AI by Yuval Noah Harari

A book connecting Artificial Intelligence with storytelling around a Stone Age campfire certainly piqued my interest, especially given the stratospheric success of its author’s earlier works. Indeed, historian Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens (2011) was so successful that in 2019 he and his husband, Itzik Yahav, cofounded ‘Sapienship’, an initiative advocating on global challenges through focused conversations and global responsibility. In this spirit, Harari’s latest book, Nexus , focuses on the AI revolution. His Homo Deus (2015) also tackled this theme, but here Harari recapitulates ideas from both these earlier books and then develops them using an innovative framework that reviews history in terms of the impact of information networks. It is the relaying of information, says Harari, that connects Stone Age storytellers and AI.

Dark City: True stories of crimes, cock-ups, crooks and cops by John Silvester

In 2020, John Silvester posed for a portrait by the artist Mica Pillemer. The picture is an arresting one: Silvester, in business attire, posing as a boxer. Behind him, the walls are plastered with newspapers and posters, a testament to his more than four decades of experience as a Melbourne crime reporter. His fists are raised, his dark eyes hold the viewer’s, his mouth is upturned with the faintest crook of a smile.

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner

The recent discovery of Neanderthal remains in a cave in France is timely for Rachel Kushner’s latest novel, Creation Lake , which opens with the question: ‘What is a human being?’ Timely, because this novel deals with the question in a largely archaeological manner, focusing on that nebulous point in history when Neanderthals and Homo sapiens parted ways. The former, it seems, went quietly into extinction; the latter, with their cunning intellect and knack for not knowing what is good for them, went on to create the socio-environmental mess we find ourselves in today.

Juice by Tim Winton

Clocking in at 513 pages, Tim Winton’s new novel carries all the apparatus of a major publishing event. Juice is an ambitious work, technically very skilful, which seeks to delineate not only a dystopian prospect of the planet’s future but also an alternative, revisionist version of its historical past.

The Penguin Book of Greek and Latin Lyric Verse by Christopher Childers

In this impressive, 1,000-page volume, Christopher Childers has collected almost all that remains of the highly prized verses that were written in Greek and Latin to accompany performance on the lyre. This collection of ‘lyric verse’ provides a roll-call of the greatest poetic voices to emerge in antiquity. Some names, such as Sappho, are still familiar to many today. For others, such as Ibycus, their star has unjustly fallen and the fragments that survive tantalise us with their potential.

Kaddish: A Holocaust Memorial Concert

Conclave

Melbourne International Jazz Festival

A Different Man

Eucalyptus

Book of the week.

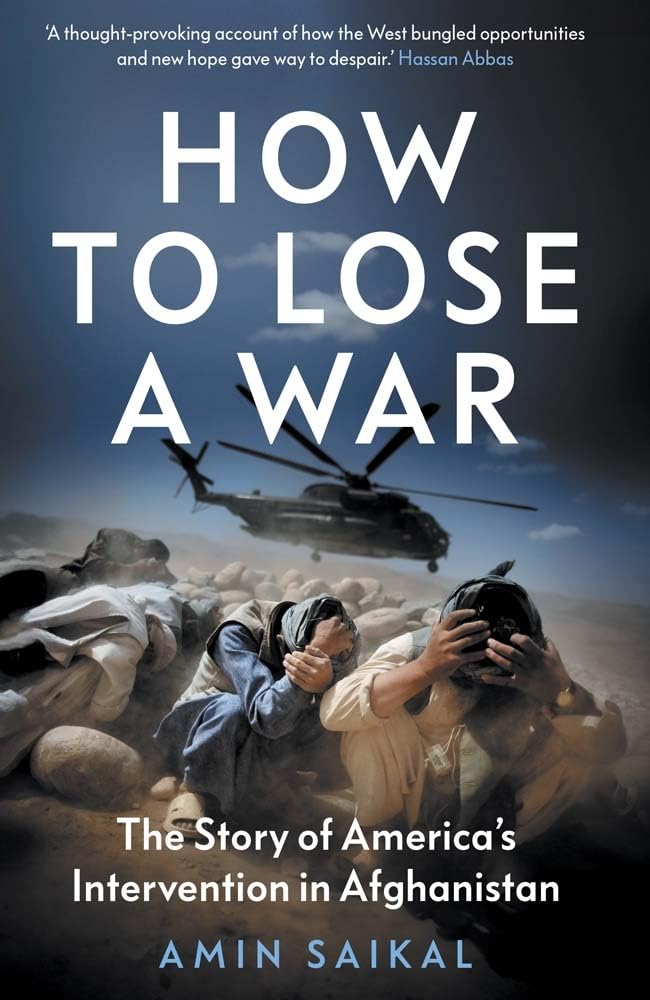

How to Lose a War: The story of America’s intervention in Afghanistan by Amin Saikal

Though scarcely a teenager at the time, I remember clearly what I was doing when I heard the news of John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. That was a seminal event for the baby-boomer generation – not only in the United States, but around a then barely globalised world. I suspect the equivalent event for young adults today is the horrifying television footage, rebroadcast countless times since, of two passenger aircraft being deliberately flown into the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center on 11 September 2001.

Short story

Jolley prize 2016 (winner): 'glisk' by josephine rowe.

W e are wading out, the five of us. I remember this. The sun an hour or two from melting into the ocean, the slick trail of its gold showing the way we will take ...

The power paradox: Illiberalism and Hindu majoritarianism in Modi’s India

On 15 August 2022, it will be seventy-five years since Jawaharlal Nehru declared that India’s ‘tryst with destiny’ had finally been ‘redeemed’. The rapturous crowds that gathered outside the Constituent Assembly in New Delhi on that sultry summer night cheered as loudspeakers relayed the words: ‘At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.’

The ABR Podcast

‘We right to go?’

This week on The ABR Podcast Johanna Leggatt reviews Australia’s Pandemic Exceptionalism: How we crushed the curve but lost the race by Steven Hamilton and Richard Holden. She quotes from the book: ‘There will be another pandemic. It might not happen for another century, or it might happen very soon.’ Johanna Leggatt is a Melbourne-based writer and journalist. Listen to Johanna Leggatt’s “‘We right to go?’ Heeding the lessons of the Covid-19 pandemic”, published in the October issue of ABR .

‘Melbourne Rare Book Week reaches a milestone’ by Des Cowley

An interview with Mary Beard

Calibre essays.

'The love song of Henry and Olga' by Ann-Marie Priest

From the archive.

Graham Kennedy Treasures: Friends remember the king by Mike McColl Jones

T ucked inside a plastic sleeve affixed to the inside front cover of this handsome, large-format book is a video disc promising ‘The Best of Graham Kennedy’. Introduced by Stuart Wagstaff, the one hour of footage offers a compilation of Kennedy’s work for Channel Nine drawn from the early days of In Melbourne Tonight (1957–69) and The Graham Kennedy Show (1972–75). Most of the sketches, dance routines, advertising segments and encounters with the audience I had seen before. Rover the Wonder Dog peeing on a camera while refusing to spruik Pal dog food has become part of the collective memory of Kennedy’s contrived mayhem, revisited whenever television (especially Channel Nine) embarks on one of those moments of self-memorialisation with which it marks each milestone.

Fault Lines by Pierz Newton-John

In this collection of short stories from Pierz Newton-John, the author calls upon the suburban familiarity of a garden weed: couch grass, the fast-spreading pest whose rhizomes grow rapidly in a suffocating network, until the area it covers is ‘strangled’ and the custodian must ‘pull up the entire intractable tangle and start again’. This network of affliction that spreads throughout Newton-John’s characters – disaffection, self-denial, drug dependency, turmoil, ambivalence, sheer despair – is handled nimbly by Newton-John, who wields a superb descriptive talent. Each story ends with the dislodging of some kind of rot, or the threat of destruction, because a situation is no longer sustainable.

Helen Ennis reviews 'Lives of the Great Photographers' by Juliet Hacking

- Forgot username?

- Forgot password?

Book Club Pick

The Latest List

Latest Issue

Inga Simpson on The Thinning and our fragile future

Taste test – endgame by sarah barrie, from the editor’s desk – october 2024.

Latest Reviews

See all reviews

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami

The Proof of My Innocence by Jonathan Coe

The Fog by Brooke Hardwick

Cactus Pear For My Beloved by Samah Sabawi

Good Reading Podcast

Chris Hammer on small town crime and blood relatives in The Valley

Melissa Lucashenko on her epic First Nations story set generations apart, Edenglassie

Beverley McWilliams on her 2024 Historical Novel Society of Australasia prize-winning novel for children, Spies in the Sky

Kathy Mexted on the incredible stories of Australian women who reach for the sky in ‘Take Flight’

Book Briefs

See all book briefs

QBD Books announces 2024 Book of the Year winners

Nagi Maehashi’s RecipeTin Eats: Tonight breaks sales record

Dr Kay Scarpetta coming to TV

What’s trending on Good Reading

John Steinbeck’s East of Eden series begins production

Coming soon, the defiance of frances dickinson.

Three Boys Gone

Unfinished Business

The Campers

Raising Hare

The Lion Women of Tehran

Would You Rather

The Knowing

Joan Lindsay

Discover More Reviews

Modern & Contemporary

Historical Fiction

Crime / Thrillers

Fantasy / Sci-fi

Non-Fiction

Biographies & True Stories

Lifestyle, Sport & Leisure

Health & Personal Development

Finance / Business

History, Science & Environment

Younger Readers

Young Adults

Primary Kids

Picture Books

Non-Fiction For Kids

Books By Age

COMMENTS

This month ABR sharpens its memory, looking back at Australia’s involvement in East Timor on the twenty-fifth anniversary of its liberation. We ask what the US invasion of Afghanistan revealed, how referendums have been lost and won, …

Latest Reviews. See all reviews. Cactus Pear For My Beloved by Samah Sabawi. Biography & True Stories, Good Reading Magazine, Non-Fiction, Open Access, Nov 2024. If there’s a more …

Australian Book Review (ABR) is Australia's leading arts and literary review. Created in 1961, and now based in Melbourne, ABR publishes reviews, essays, commentaries and creative writing.

The best australian book blogs ranked by influence, up to date. These australian book reviewers can help you get book reviews on Amazon, Goodreads, and more. Filter by australian book …

Publishing longform criticism and essays by Australia's best writers since 2013. Online and in Parramatta.

Welcome to Aussie Reviews, the Australian review site. Since 2001 we have been reviewing the best of Australian books of all genres. Now we have a fresh new look, making it easier to …

Australian Book Review Online has a national scope and is committed to highlighting the full range of critical and creative writing from around Australia. Registered members of the National Library can access these …

Australian Book Review is an Australian arts and literary review. [1] Created in 1961, [2] ABR is an independent non-profit organisation that publishes articles, reviews, commentaries, essays, …