Homework – Top 3 Pros and Cons

Pro/Con Arguments | Discussion Questions | Take Action | Sources | More Debates

From dioramas to book reports, from algebraic word problems to research projects, whether students should be given homework, as well as the type and amount of homework, has been debated for over a century. [ 1 ]

While we are unsure who invented homework, we do know that the word “homework” dates back to ancient Rome. Pliny the Younger asked his followers to practice their speeches at home. Memorization exercises as homework continued through the Middle Ages and Enlightenment by monks and other scholars. [ 45 ]

In the 19th century, German students of the Volksschulen or “People’s Schools” were given assignments to complete outside of the school day. This concept of homework quickly spread across Europe and was brought to the United States by Horace Mann , who encountered the idea in Prussia. [ 45 ]

In the early 1900s, progressive education theorists, championed by the magazine Ladies’ Home Journal , decried homework’s negative impact on children’s physical and mental health, leading California to ban homework for students under 15 from 1901 until 1917. In the 1930s, homework was portrayed as child labor, which was newly illegal, but the prevailing argument was that kids needed time to do household chores. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 45 ] [ 46 ]

Public opinion swayed again in favor of homework in the 1950s due to concerns about keeping up with the Soviet Union’s technological advances during the Cold War . And, in 1986, the US government included homework as an educational quality boosting tool. [ 3 ] [ 45 ]

A 2014 study found kindergarteners to fifth graders averaged 2.9 hours of homework per week, sixth to eighth graders 3.2 hours per teacher, and ninth to twelfth graders 3.5 hours per teacher. A 2014-2019 study found that teens spent about an hour a day on homework. [ 4 ] [ 44 ]

Beginning in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic complicated the very idea of homework as students were schooling remotely and many were doing all school work from home. Washington Post journalist Valerie Strauss asked, “Does homework work when kids are learning all day at home?” While students were mostly back in school buildings in fall 2021, the question remains of how effective homework is as an educational tool. [ 47 ]

Is Homework Beneficial?

Pro 1 Homework improves student achievement. Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicated that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” [ 6 ] Students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework on both standardized tests and grades. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take-home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school. [ 10 ] Read More

Pro 2 Homework helps to reinforce classroom learning, while developing good study habits and life skills. Students typically retain only 50% of the information teachers provide in class, and they need to apply that information in order to truly learn it. Abby Freireich and Brian Platzer, co-founders of Teachers Who Tutor NYC, explained, “at-home assignments help students learn the material taught in class. Students require independent practice to internalize new concepts… [And] these assignments can provide valuable data for teachers about how well students understand the curriculum.” [ 11 ] [ 49 ] Elementary school students who were taught “strategies to organize and complete homework,” such as prioritizing homework activities, collecting study materials, note-taking, and following directions, showed increased grades and more positive comments on report cards. [ 17 ] Research by the City University of New York noted that “students who engage in self-regulatory processes while completing homework,” such as goal-setting, time management, and remaining focused, “are generally more motivated and are higher achievers than those who do not use these processes.” [ 18 ] Homework also helps students develop key skills that they’ll use throughout their lives: accountability, autonomy, discipline, time management, self-direction, critical thinking, and independent problem-solving. Freireich and Platzer noted that “homework helps students acquire the skills needed to plan, organize, and complete their work.” [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 49 ] Read More

Pro 3 Homework allows parents to be involved with children’s learning. Thanks to take-home assignments, parents are able to track what their children are learning at school as well as their academic strengths and weaknesses. [ 12 ] Data from a nationwide sample of elementary school students show that parental involvement in homework can improve class performance, especially among economically disadvantaged African-American and Hispanic students. [ 20 ] Research from Johns Hopkins University found that an interactive homework process known as TIPS (Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork) improves student achievement: “Students in the TIPS group earned significantly higher report card grades after 18 weeks (1 TIPS assignment per week) than did non-TIPS students.” [ 21 ] Homework can also help clue parents in to the existence of any learning disabilities their children may have, allowing them to get help and adjust learning strategies as needed. Duke University Professor Harris Cooper noted, “Two parents once told me they refused to believe their child had a learning disability until homework revealed it to them.” [ 12 ] Read More

Con 1 Too much homework can be harmful. A poll of California high school students found that 59% thought they had too much homework. 82% of respondents said that they were “often or always stressed by schoolwork.” High-achieving high school students said too much homework leads to sleep deprivation and other health problems such as headaches, exhaustion, weight loss, and stomach problems. [ 24 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] Alfie Kohn, an education and parenting expert, said, “Kids should have a chance to just be kids… it’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.” [ 27 ] Emmy Kang, a mental health counselor, explained, “More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies.” [ 48 ] Excessive homework can also lead to cheating: 90% of middle school students and 67% of high school students admit to copying someone else’s homework, and 43% of college students engaged in “unauthorized collaboration” on out-of-class assignments. Even parents take shortcuts on homework: 43% of those surveyed admitted to having completed a child’s assignment for them. [ 30 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Read More

Con 2 Homework exacerbates the digital divide or homework gap. Kiara Taylor, financial expert, defined the digital divide as “the gap between demographics and regions that have access to modern information and communications technology and those that don’t. Though the term now encompasses the technical and financial ability to utilize available technology—along with access (or a lack of access) to the Internet—the gap it refers to is constantly shifting with the development of technology.” For students, this is often called the homework gap. [ 50 ] [ 51 ] 30% (about 15 to 16 million) public school students either did not have an adequate internet connection or an appropriate device, or both, for distance learning. Completing homework for these students is more complicated (having to find a safe place with an internet connection, or borrowing a laptop, for example) or impossible. [ 51 ] A Hispanic Heritage Foundation study found that 96.5% of students across the country needed to use the internet for homework, and nearly half reported they were sometimes unable to complete their homework due to lack of access to the internet or a computer, which often resulted in lower grades. [ 37 ] [ 38 ] One study concluded that homework increases social inequality because it “potentially serves as a mechanism to further advantage those students who already experience some privilege in the school system while further disadvantaging those who may already be in a marginalized position.” [ 39 ] Read More

Con 3 Homework does not help younger students, and may not help high school students. We’ve known for a while that homework does not help elementary students. A 2006 study found that “homework had no association with achievement gains” when measured by standardized tests results or grades. [ 7 ] Fourth grade students who did no homework got roughly the same score on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) math exam as those who did 30 minutes of homework a night. Students who did 45 minutes or more of homework a night actually did worse. [ 41 ] Temple University professor Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek said that homework is not the most effective tool for young learners to apply new information: “They’re learning way more important skills when they’re not doing their homework.” [ 42 ] In fact, homework may not be helpful at the high school level either. Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, stated, “I interviewed high school teachers who completely stopped giving homework and there was no downside, it was all upside.” He explains, “just because the same kids who get more homework do a little better on tests, doesn’t mean the homework made that happen.” [ 52 ] Read More

Discussion Questions

1. Is homework beneficial? Consider the study data, your personal experience, and other types of information. Explain your answer(s).

2. If homework were banned, what other educational strategies would help students learn classroom material? Explain your answer(s).

3. How has homework been helpful to you personally? How has homework been unhelpful to you personally? Make carefully considered lists for both sides.

Take Action

1. Examine an argument in favor of quality homework assignments from Janine Bempechat.

2. Explore Oxford Learning’s infographic on the effects of homework on students.

3. Consider Joseph Lathan’s argument that homework promotes inequality .

4. Consider how you felt about the issue before reading this article. After reading the pros and cons on this topic, has your thinking changed? If so, how? List two to three ways. If your thoughts have not changed, list two to three ways your better understanding of the “other side of the issue” now helps you better argue your position.

5. Push for the position and policies you support by writing US national senators and representatives .

| 1. | Tom Loveless, “Homework in America: Part II of the 2014 Brown Center Report of American Education,” brookings.edu, Mar. 18, 2014 | |

| 2. | Edward Bok, “A National Crime at the Feet of American Parents,” , Jan. 1900 | |

| 3. | Tim Walker, “The Great Homework Debate: What’s Getting Lost in the Hype,” neatoday.org, Sep. 23, 2015 | |

| 4. | University of Phoenix College of Education, “Homework Anxiety: Survey Reveals How Much Homework K-12 Students Are Assigned and Why Teachers Deem It Beneficial,” phoenix.edu, Feb. 24, 2014 | |

| 5. | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “PISA in Focus No. 46: Does Homework Perpetuate Inequities in Education?,” oecd.org, Dec. 2014 | |

| 6. | Adam V. Maltese, Robert H. Tai, and Xitao Fan, “When is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math,” , 2012 | |

| 7. | Harris Cooper, Jorgianne Civey Robinson, and Erika A. Patall, “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Researcher, 1987-2003,” , 2006 | |

| 8. | Gökhan Bas, Cihad Sentürk, and Fatih Mehmet Cigerci, “Homework and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Research,” , 2017 | |

| 9. | Huiyong Fan, Jianzhong Xu, Zhihui Cai, Jinbo He, and Xitao Fan, “Homework and Students’ Achievement in Math and Science: A 30-Year Meta-Analysis, 1986-2015,” , 2017 | |

| 10. | Charlene Marie Kalenkoski and Sabrina Wulff Pabilonia, “Does High School Homework Increase Academic Achievement?,” iza.og, Apr. 2014 | |

| 11. | Ron Kurtus, “Purpose of Homework,” school-for-champions.com, July 8, 2012 | |

| 12. | Harris Cooper, “Yes, Teachers Should Give Homework – The Benefits Are Many,” newsobserver.com, Sep. 2, 2016 | |

| 13. | Tammi A. Minke, “Types of Homework and Their Effect on Student Achievement,” repository.stcloudstate.edu, 2017 | |

| 14. | LakkshyaEducation.com, “How Does Homework Help Students: Suggestions From Experts,” LakkshyaEducation.com (accessed Aug. 29, 2018) | |

| 15. | University of Montreal, “Do Kids Benefit from Homework?,” teaching.monster.com (accessed Aug. 30, 2018) | |

| 16. | Glenda Faye Pryor-Johnson, “Why Homework Is Actually Good for Kids,” memphisparent.com, Feb. 1, 2012 | |

| 17. | Joan M. Shepard, “Developing Responsibility for Completing and Handing in Daily Homework Assignments for Students in Grades Three, Four, and Five,” eric.ed.gov, 1999 | |

| 18. | Darshanand Ramdass and Barry J. Zimmerman, “Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework,” , 2011 | |

| 19. | US Department of Education, “Let’s Do Homework!,” ed.gov (accessed Aug. 29, 2018) | |

| 20. | Loretta Waldman, “Sociologist Upends Notions about Parental Help with Homework,” phys.org, Apr. 12, 2014 | |

| 21. | Frances L. Van Voorhis, “Reflecting on the Homework Ritual: Assignments and Designs,” , June 2010 | |

| 22. | Roel J. F. J. Aries and Sofie J. Cabus, “Parental Homework Involvement Improves Test Scores? A Review of the Literature,” , June 2015 | |

| 23. | Jamie Ballard, “40% of People Say Elementary School Students Have Too Much Homework,” yougov.com, July 31, 2018 | |

| 24. | Stanford University, “Stanford Survey of Adolescent School Experiences Report: Mira Costa High School, Winter 2017,” stanford.edu, 2017 | |

| 25. | Cathy Vatterott, “Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs,” ascd.org, 2009 | |

| 26. | End the Race, “Homework: You Can Make a Difference,” racetonowhere.com (accessed Aug. 24, 2018) | |

| 27. | Elissa Strauss, “Opinion: Your Kid Is Right, Homework Is Pointless. Here’s What You Should Do Instead.,” cnn.com, Jan. 28, 2020 | |

| 28. | Jeanne Fratello, “Survey: Homework Is Biggest Source of Stress for Mira Costa Students,” digmb.com, Dec. 15, 2017 | |

| 29. | Clifton B. Parker, “Stanford Research Shows Pitfalls of Homework,” stanford.edu, Mar. 10, 2014 | |

| 30. | AdCouncil, “Cheating Is a Personal Foul: Academic Cheating Background,” glass-castle.com (accessed Aug. 16, 2018) | |

| 31. | Jeffrey R. Young, “High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame,” chronicle.com, Mar. 28, 2010 | |

| 32. | Robin McClure, “Do You Do Your Child’s Homework?,” verywellfamily.com, Mar. 14, 2018 | |

| 33. | Robert M. Pressman, David B. Sugarman, Melissa L. Nemon, Jennifer, Desjarlais, Judith A. Owens, and Allison Schettini-Evans, “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background,” , 2015 | |

| 34. | Heather Koball and Yang Jiang, “Basic Facts about Low-Income Children,” nccp.org, Jan. 2018 | |

| 35. | Meagan McGovern, “Homework Is for Rich Kids,” huffingtonpost.com, Sep. 2, 2016 | |

| 36. | H. Richard Milner IV, “Not All Students Have Access to Homework Help,” nytimes.com, Nov. 13, 2014 | |

| 37. | Claire McLaughlin, “The Homework Gap: The ‘Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide’,” neatoday.org, Apr. 20, 2016 | |

| 38. | Doug Levin, “This Evening’s Homework Requires the Use of the Internet,” edtechstrategies.com, May 1, 2015 | |

| 39. | Amy Lutz and Lakshmi Jayaram, “Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework,” , June 2015 | |

| 40. | Sandra L. Hofferth and John F. Sandberg, “How American Children Spend Their Time,” psc.isr.umich.edu, Apr. 17, 2000 | |

| 41. | Alfie Kohn, “Does Homework Improve Learning?,” alfiekohn.org, 2006 | |

| 42. | Patrick A. Coleman, “Elementary School Homework Probably Isn’t Good for Kids,” fatherly.com, Feb. 8, 2018 | |

| 43. | Valerie Strauss, “Why This Superintendent Is Banning Homework – and Asking Kids to Read Instead,” washingtonpost.com, July 17, 2017 | |

| 44. | Pew Research Center, “The Way U.S. Teens Spend Their Time Is Changing, but Differences between Boys and Girls Persist,” pewresearch.org, Feb. 20, 2019 | |

| 45. | ThroughEducation, “The History of Homework: Why Was It Invented and Who Was behind It?,” , Feb. 14, 2020 | |

| 46. | History, “Why Homework Was Banned,” (accessed Feb. 24, 2022) | |

| 47. | Valerie Strauss, “Does Homework Work When Kids Are Learning All Day at Home?,” , Sep. 2, 2020 | |

| 48. | Sara M Moniuszko, “Is It Time to Get Rid of Homework? Mental Health Experts Weigh In,” , Aug. 17, 2021 | |

| 49. | Abby Freireich and Brian Platzer, “The Worsening Homework Problem,” , Apr. 13, 2021 | |

| 50. | Kiara Taylor, “Digital Divide,” , Feb. 12, 2022 | |

| 51. | Marguerite Reardon, “The Digital Divide Has Left Millions of School Kids Behind,” , May 5, 2021 | |

| 52. | Rachel Paula Abrahamson, “Why More and More Teachers Are Joining the Anti-Homework Movement,” , Sep. 10, 2021 |

More School Debate Topics

Should K-12 Students Dissect Animals in Science Classrooms? – Proponents say dissecting real animals is a better learning experience. Opponents say the practice is bad for the environment.

Should Students Have to Wear School Uniforms? – Proponents say uniforms may increase student safety. Opponents say uniforms restrict expression.

Should Corporal Punishment Be Used in K-12 Schools? – Proponents say corporal punishment is an appropriate discipline. Opponents say it inflicts long-lasting physical and mental harm on students.

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

Cite This Page

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Should We Get Rid of Homework?

Some educators are pushing to get rid of homework. Would that be a good thing?

By Jeremy Engle and Michael Gonchar

Do you like doing homework? Do you think it has benefited you educationally?

Has homework ever helped you practice a difficult skill — in math, for example — until you mastered it? Has it helped you learn new concepts in history or science? Has it helped to teach you life skills, such as independence and responsibility? Or, have you had a more negative experience with homework? Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes?

Should we get rid of homework?

In “ The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, ” published in July, the Times Opinion writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that homework may be imperfect, but it still serves an important purpose in school. The essay begins:

Do students really need to do their homework? As a parent and a former teacher, I have been pondering this question for quite a long time. The teacher side of me can acknowledge that there were assignments I gave out to my students that probably had little to no academic value. But I also imagine that some of my students never would have done their basic reading if they hadn’t been trained to complete expected assignments, which would have made the task of teaching an English class nearly impossible. As a parent, I would rather my daughter not get stuck doing the sort of pointless homework I would occasionally assign, but I also think there’s a lot of value in saying, “Hey, a lot of work you’re going to end up doing in your life is pointless, so why not just get used to it?” I certainly am not the only person wondering about the value of homework. Recently, the sociologist Jessica McCrory Calarco and the mathematics education scholars Ilana Horn and Grace Chen published a paper, “ You Need to Be More Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities .” They argued that while there’s some evidence that homework might help students learn, it also exacerbates inequalities and reinforces what they call the “meritocratic” narrative that says kids who do well in school do so because of “individual competence, effort and responsibility.” The authors believe this meritocratic narrative is a myth and that homework — math homework in particular — further entrenches the myth in the minds of teachers and their students. Calarco, Horn and Chen write, “Research has highlighted inequalities in students’ homework production and linked those inequalities to differences in students’ home lives and in the support students’ families can provide.”

Mr. Kang argues:

But there’s a defense of homework that doesn’t really have much to do with class mobility, equality or any sense of reinforcing the notion of meritocracy. It’s one that became quite clear to me when I was a teacher: Kids need to learn how to practice things. Homework, in many cases, is the only ritualized thing they have to do every day. Even if we could perfectly equalize opportunity in school and empower all students not to be encumbered by the weight of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity, I’m not sure what good it would do if the kids didn’t know how to do something relentlessly, over and over again, until they perfected it. Most teachers know that type of progress is very difficult to achieve inside the classroom, regardless of a student’s background, which is why, I imagine, Calarco, Horn and Chen found that most teachers weren’t thinking in a structural inequalities frame. Holistic ideas of education, in which learning is emphasized and students can explore concepts and ideas, are largely for the types of kids who don’t need to worry about class mobility. A defense of rote practice through homework might seem revanchist at this moment, but if we truly believe that schools should teach children lessons that fall outside the meritocracy, I can’t think of one that matters more than the simple satisfaction of mastering something that you were once bad at. That takes homework and the acknowledgment that sometimes a student can get a question wrong and, with proper instruction, eventually get it right.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

15 Should Homework Be Banned Pros and Cons

Homework was a staple of the public and private schooling experience for many of us growing up. There were long nights spent on book reports, science projects, and all of those repetitive math sheets. In many ways, it felt like an inevitable part of the educational experience. Unless you could power through all of your assignments during your free time in class, then there was going to be time spent at home working on specific subjects.

More schools are looking at the idea of banning homework from the modern educational experience. Instead of sending work home with students each night, they are finding alternative ways to ensure that each student can understand the curriculum without involving the uncertainty of parental involvement.

Although banning homework might seem like an unorthodox process, there are legitimate advantages to consider with this effort. There are some disadvantages which some families may encounter as well.

These are the updated lists of the pros and cons of banning homework to review.

List of the Pros of Banning Homework

1. Giving homework to students does not always improve their academic outcomes. The reality of homework for the modern student is that we do not know if it is helpful to have extra work assigned to them outside of the classroom. Every study that has looked at the subject has had design flaws which causes the data collected to be questionable at best. Although there is some information to suggest that students in seventh grade and higher can benefit from limited homework, banning it for students younger than that seems to be beneficial for their learning experience.

2. Banning homework can reduce burnout issues with students. Teachers are seeing homework stress occur in the classroom more frequently today than ever before. Almost half of all high school teachers in North America have seen this issue with their students at some point during the year. About 25% of grade school teachers say that they have seen the same thing.

When students are dealing with the impact of homework on their lives, it can have a tremendously adverse impact. One of the most cited reasons for students dropping out of school is that they cannot complete their homework on time.

3. Banning homework would increase the amount of family time available to students. Homework creates a significant disruption to family relationships. Over half of all parents in North America say that they have had a significant argument with their children over homework in the past month. 1/3 of families say that homework is their primary source of struggle in the home. Not only does it reduce the amount of time that everyone has to spend together, it reduces the chances that parents have to teach their own skills and belief systems to their kids.

4. It reduces the negative impact of homework on the health of a student. Many students suffer academically when they cannot finish a homework assignment on time. Although assumptions are often made about the time management skills of the individual when this outcome occurs, the reasons why it happens is usually more complex. It may be too difficult, too boring, or there may not be enough time in the day to complete the work.

When students experience failure in this area, it can lead to severe mental health issues. Some perceive themselves as a scholarly failure, which translates to an inability to live life successfully. It can disrupt a desire to learn. There is even an increased risk of suicide for some youth because of this issue. Banning it would reduce these risks immediately.

5. Eliminating homework would allow for an established sleep cycle. The average high school student requires between 8-10 hours of sleep to function at their best the next day. Grade-school students may require an extra hour or two beyond that figure. When teachers assign homework, then it increases the risk for each individual that they will not receive the amount that they require each night.

When children do not get enough sleep, a significant rest deficit occurs which can impact their ability to pay attention in school. It can cause unintended weight gain. There may even be issues with emotional control. Banning homework would help to reduce these risks as well.

6. It increases the amount of socialization time that students receive. People who are only spending time in school and then going home to do more work are at a higher risk of experiencing loneliness and isolation. When these emotions are present, then a student is more likely to feel “down and out” mentally and physically. They lack meaningful connections with other people. These feelings are the health equivalent of smoking 15 cigarettes per day. If students are spending time on homework, then they are not spending time connecting with their family and friends.

7. It reduces the repetition that students face in the modern learning process. Most of the tasks that homework requires of students is repetitive and uninteresting. Kids love to resolve challenges on tasks that they are passionate about at that moment in their lives. Forcing them to complete the same problems repetitively as a way to “learn” core concepts can create issues with knowledge retention later in life. When you add in the fact that most lessons sent for homework must be done by themselves, banning homework will reduce the repetition that students face, allowing for a better overall outcome.

8. Home environments can be chaotic. Although some students can do homework in a quiet room without distractions, that is not the case for most kids. There are numerous events that happen at home which can pull a child’s attention away from the work that their teacher wants them to do. It isn’t just the Internet, video games, and television which are problematic either. Household chores, family issues, employment, and athletic requirements can make it a challenge to get the assigned work finished on time.

List of the Cons of Banning Homework

1. Homework allows parents to be involved with the educational process. Parents need to know what their children are learning in school. Even if they ask their children about what they are learning, the answers tend to be in generalities instead of specifics. By sending home work from the classroom, it allows parents to see and experience the work that their kids are doing when they are in school during the day. Then moms and dads can get involved with the learning process to reinforce the core concepts that were discovered by their children each day.

2. It can help parents and teachers identify learning disabilities. Many children develop a self-defense mechanism which allows them to appear like any other kid that is in their classroom. This process allows them to hide learning disabilities which may be hindering their educational progress. The presence of homework makes it possible for parents and teachers to identify this issue because kids can’t hide their struggles when they must work 1-on-1 with their parents on specific subjects. Banning homework would eliminate 50% of the opportunities to identify potential issues immediately.

3. Homework allows teachers to observe how their students understand the material. Teachers often use homework as a way to gauge how well a student is understanding the materials they are learning. Although some might point out that assignments and exams in the classroom can do the same thing, testing often requires preparation at home. It creates more anxiety and stress sometimes then even homework does. That is why banning it can be problematic for some students. Some students experience more pressure than they would during this assessment process when quizzes and tests are the only measurement of their success.

4. It teaches students how to manage their time wisely. As people grow older, they realize that time is a finite commodity. We must manage it wisely to maximize our productivity. Homework assignments are a way to encourage the development of this skill at an early age. The trick is to keep the amount of time required for the work down to a manageable level. As a general rule, students should spend about 10 minutes each school day doing homework, organizing their schedule around this need. If there are scheduling conflicts, then this process offers families a chance to create priorities.

5. Homework encourages students to be accountable for their role. Teachers are present in the classroom to offer access to information and skill-building opportunities that can improve the quality of life for each student. Administrators work to find a curriculum that will benefit the most people in an efficient way. Parents work hard to ensure their kids make it to school on time, follow healthy routines, and communicate with their school district to ensure the most effective learning opportunities possible. None of that matters if the student is not invested in the work in the first place. Homework assignments not only teach children how to work independently, but they also show them how to take responsibility for their part of the overall educational process.

6. It helps to teach important life lessons. Homework is an essential tool in the development of life lessons, such as communicating with others or comprehending something they have just read. It teaches kids how to think, solve problems, and even build an understanding for the issues that occur in our society right now. Many of the issues that lead to the idea to ban homework occur because someone in the life of a student communicated to them that this work was a waste of time. There are times in life when people need to do things that they don’t like or want to do. Homework helps a student begin to find the coping skills needed to be successful in that situation.

7. Homework allows for further research into class materials. Most classrooms offer less than 1 hour of instruction per subject during the day. For many students, that is not enough time to obtain a firm grasp on the materials being taught. Having homework assignments allows a student to perform more research, using their at-home tools to take a deeper look into the materials that would otherwise be impossible if homework was banned. That process can lead to a more significant understanding of the concepts involved, reducing anxiety levels because they have a complete grasp on the materials.

The pros and cons of banning homework is a decision that ultimately lies with each school district. Parents always have the option to pursue homeschooling or online learning if they disagree with the decisions that are made in this area. Whether you’re for more homework or want to see less of it, we can all agree on the fact that the absence of any reliable data about its usefulness makes it a challenge to know for certain which option is the best one to choose in this debate.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Only 100 Left! Get FREE Timeline Posters Sent Right to Your School ✨

Should Homework Be Banned? Here’s What Real Educators Think

Plus, what research on the subject really tells us.

Every kid dreams of it: “Homework banned forevermore!” For as long as anyone can remember, homework has just been one of those things kids have to do because it’s good for them, like eating their vegetables. But is it really as important to do hours of homework every night as it is to eat broccoli and carrots? New research suggests homework might not have a whole lot of value. This leads to a big question: Should we ban homework?

“I think parents already have enough stress just in providing for their families!” says one Arizona 1st grade teacher. “I can imagine one more chore of having to sit down and do homework with their child would add that much more stress. Kids don’t like doing homework, so it frustrates them, which in turn frustrates parents. They spend time fighting about homework that they could be spending quality time over a board game or family meal!”

We wanted to know more, as every educator should. So, we combed through recent research to see what experts say, and explored the news to see what schools in the United States and abroad have tried. Plus, we asked 40+ active K-12 educators to share their thoughts. Here’s what we found out.

Does homework actually work?

This is one of the biggest questions people have around homework bans. Is it worth the time students are spending on it? How many kids actually do it consistently? How involved do parents need to be? In short: Does homework have value?

What the Research Says

Educators first started asking serious questions about homework more than 20 years ago, when an article that evaluated decades of research on homework suggested that it might not be as effective as we thought, at least in the lower grades . But other studies on homework indicate that students who do homework as assigned have higher academic outcomes overall, especially in grades 7 through 12.

What Real Educators Say

Most of the teachers that responded to our survey felt homework (especially for upper grades) does have at least some value. Many, though, were less concerned with academic benefits and more with developing general life skills like time management and responsibility.

- “For older students, reasonable homework that is preparation for class the next day helps students learn how to manage their time, meet deadlines, and take responsibility for their learning. I am a fan of flipped learning—students watch the lesson for homework and then use class time to ask questions, work together, work with their teacher, and do the work.” —Julie Mason, MS/HS English teacher

- “In middle school and high school, homework is important because it helps build stamina and potential study habits for college or trade schools.” —Desiree T., elementary teacher

- “Homework is good practice for subjects like math. In other subjects, it is good for reviewing subject matter.” —Ohio 8th grade social studies teacher

- “The proper amount of homework that is relevant to the daily lessons will help reinforce the skill and allow parents to see what their child is learning.” —Joanie B., Texas 4th/6th grade teacher

- “It’s not beneficial; parents today have not been taught how to help with new strategies. They are also often so busy that they cannot be bothered to help so they just give the answers. I saw a lot of this during the pandemic and even after when I would have 1st graders tell me they knew the answer ‘because they just know it.’ Not to mention the students who would actually benefit from having the extra practice of homework oftentimes do not have the support at home.” —Georgia 3rd grade teacher

- “In my 8 years of teaching, homework has never been successful for families or me. For the majority of parents and kids, it’s overwhelming. It is also additional work for teachers to manage. This is another extension and overreach of the expectations of the teacher.” —Lauren Anderson, Ohio 4th grade teacher

- “Homework isn’t busy work. How will today’s youth become tomorrow’s leaders (or survive college/trades classes) if they aren’t practicing skills to the next level?” —Arizona 1st grade teacher

Should we ban homework in elementary school?

Most adults today didn’t have homework in kindergarten, so they’re surprised when their child arrives home with a backpack full of worksheets. Older elementary students frequently bring home big projects like making a diorama or creating a family tree, something that usually means a lot of parent involvement. Is homework at this age reasonable and meaningful?

Supporters of a homework ban often cite research from John Hattie, who concluded that elementary school homework has no effect on academic progress. In a podcast he said, “Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero … It’s one of those lower hanging fruits that we should be looking in our primary schools to say, ‘Is it really making a difference?’”

The general wisdom these days seems to point to less homework overall at the elementary level, with one huge exception: reading. The research agrees: kids need to read at home as well as at school. Most educators recommend kids spend at least 20 minutes reading at home every single day.

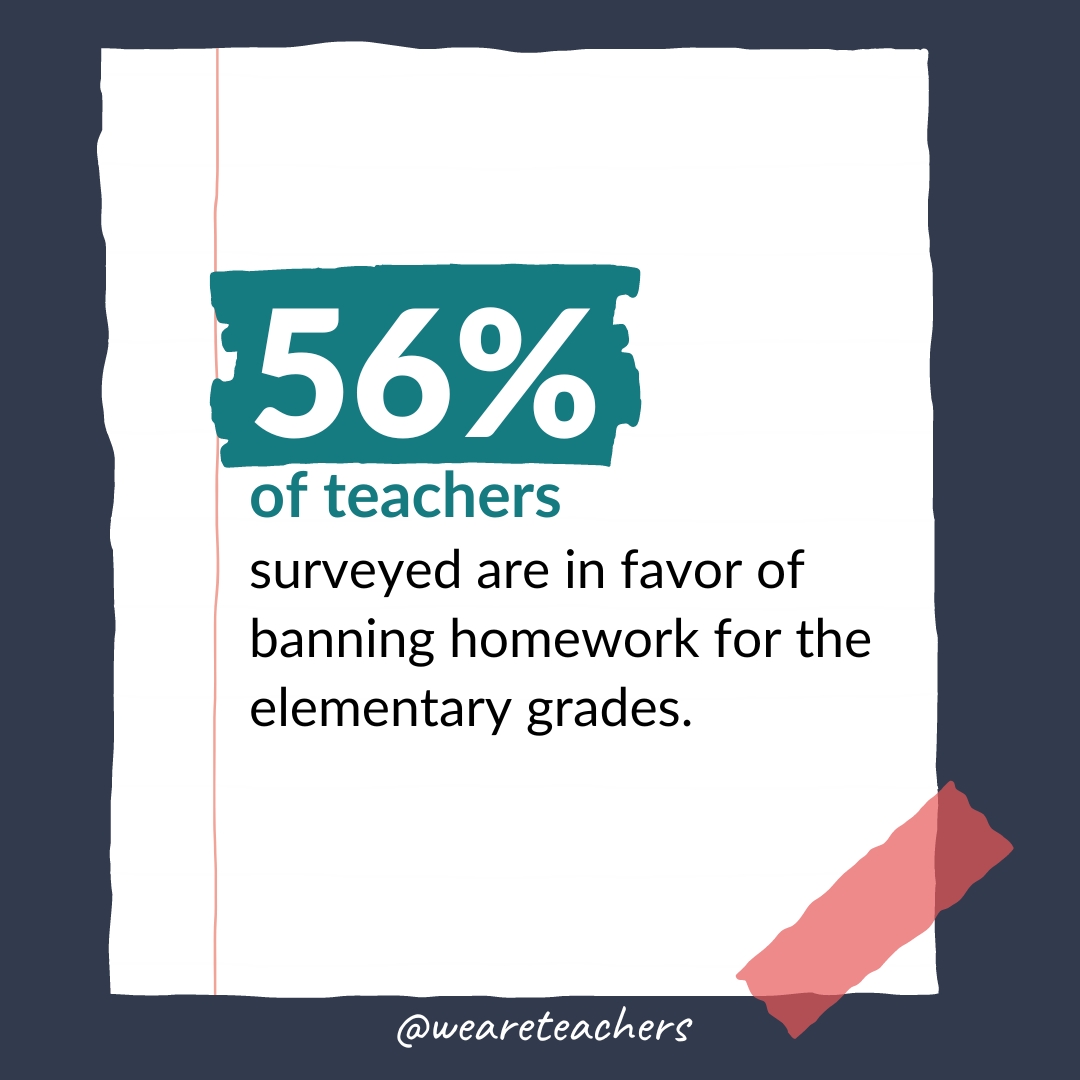

More than half of our survey respondents (56%) are in favor of banning homework for the elementary grades. They worried about kids not having support or resources at home and taking away their time for creative play or family activities. But some teachers still find value in elementary homework, especially for math and reading, as long as it’s minimal. ADVERTISEMENT

- “The common push for homework in elementary schools is ‘to prepare them for high school.’ That’s overreach. The elementary child’s job is to be an elementary child. We need to teach children where they are.” —Lauren Anderson

- “In elementary school, there should be a mixture of homework and unhomework activities. For example, a homework menu with a list of activities to complete for the month or for the week: Read in pajamas for 20 minutes, complete 3 math sheets, help cook dinner, have a family movie night, write your first and last name 10 times, help pack your snack, etc.” —Desiree T.

- “No homework should be part of the teacher motto—work smarter, not harder. Teachers spend too much time grading homework. I believe teachers and students should commit to making every minute count in the classroom so everyone can go home and just be with family.” —Jennifer N., 5th grade teacher

- “Students are learning new concepts. There is not a guarantee that someone will be able to help them with these tasks. Practicing incorrectly is worse than no practice at all.” —High school resource specialist

- “Kids should be encouraged to read [at home] and spend time with families and friends.” —Elementary English language development teacher

How much homework is enough (or too much)?

If we agree that that answer to “should we ban homework altogether” is “no,” then how much homework is reasonable? The answer seems to vary by grade level, as you would expect. But many point out the need to focus on the quality of homework over the quantity. And there have been increasing calls to let kids enjoy their longer school breaks without homework hanging over their heads .

A 2019 study showed that teenagers have doubled the amount of time they spend on homework since the 1990s. This study found that teens spend about an hour a day doing homework on average, which many would argue isn’t unreasonable. But in another study , kids self-reported doing an average of three hours of homework a night, which seems a lot more significant.

The National PTA and the NEA recommend kids do about 10 minutes of homework per night per grade level. In other words, a 3rd grader should do 30 minutes of homework. A 12th grader would do 120 minutes, or two full hours.

Perhaps more important than “How much homework?” is “What kind of homework?” Meaningful practice of what kids learned in class that day can be helpful. Busywork is not. And assigning really difficult work for kids to tackle at home, without any help from a teacher or other expert voice, is likely to simply frustrate them. Unfortunately, most teachers don’t receive training on how to assign homework that is meaningful and relevant to students. This is another area where we really need to consider a major culture shift.

While 75% of those surveyed say homework has some value in the upper grades at least, most feel it shouldn’t be excessive. Teachers stressed that it should never be used as punishment. Plus, it’s important to remember not all kids have the same access to help and resources outside the classroom.

- “Homework is important but I also believe it shouldn’t exceed 30-60 minutes a night.” —Desiree T.

- “I do think elementary students should practice their reading and maybe 10 minutes of math [at home]. That may look different for each child due to how long it may take them to complete something.” —Wisconsin elementary special education teacher

- “Elementary students are not too young to have homework once or twice a week. More than that would be too much.” —Tanya T., HS ELA teacher

- “In order to prepare students for high school, I feel 20-30 minutes of homework is okay [in elementary school].” —Florida 5th grade teacher

- “A ton of homework in every subject is ridiculous. But having to read parts of a book or an article and do several math problems should not be burdensome. And the benefit of those two things has been documented.” —Teresa Rennie, Pennsylvania 8th grade teacher

- “I encourage my elementary students to read a little every day to develop a love of reading.” —Meenal Parikh, Ohio 1st grade teacher

- “I think some homework is reasonable. Should it be a hindrance to other other activities or a major inconvenience? No. Some is good, but it doesn’t need to be an every-night thing.” —Patrick Danz, Michigan high school ELA teacher

Are there benefits to less (or no) homework?

Some schools have already banned homework, both in the United States and around the world. In April 2024, Poland enacted a homework ban for students in grades 1 through 3. In grades 4 through 8, homework must be optional and can’t count toward a student’s grade. Finnish schools are famous for assigning less homework at all ages , yet continuing to score highly in international rankings. So what are the benefits of freeing kids from homework?

Prioritizing mental health is at the forefront of the homework ban movement. Leaders say they want to give students time to develop other hobbies, relationships, and balance in their lives. When two Utah elementary schools officially banned homework , they found psychologist referrals for anxiety decreased by more than 50%.

In some cases, less or no homework can even have a positive effect on academic outcomes. One high school math teacher dramatically reduced the number of practice problems he asked his students to tackle at home. He also decreased the impact of homework on grades (from 25% to 1%). Now kids had more time to spend on just a few practice problems, and they weren’t stressed about getting them wrong. The result of changes like these? Higher standardized test scores on average.

Some schools have experimented with extending the school day in exchange for eliminating homework. This ensures that kids have more time to do independent work while also ensuring access to expert assistance. After all, not all parents have the time or ability to help with homework. And Internet access isn’t a given in every household. Keeping schoolwork at school means giving all kids equal access to the resources they need.

Teachers worry that kids who spend too much time doing homework are losing out in other areas. They want younger students to have more time to play. Older kids should be able to decompress after spending hours in the classroom. And everyone deserves more opportunities for family time and extracurriculars.

- “The stress and time surrounding homework is unnecessary. Jobs don’t require you take work home so school shouldn’t either. If a kid needs to work more, school could reach out with extra help, but homework is a waste of time. Home is for family time.” —Stephanie G., Maryland 1st grade teacher

- “Homework creates an equity problem. Not all learners have access to the same environment or supports at home as they do in school. The students who have supportive parents and resources (tutors, etc.) will succeed, while others will be penalized.” —Illinois high school teacher

- “If they work at school, they don’t need to work at home. We’re teaching them that it’s okay for someone to tell them how to spend their off-time. School is their job. I don’t like working for free; why should they think that it’s okay?” —North Carolina 1st grade teacher

- “After-school programs, sports, and unstructured play is MUCH more meaningful and impactful for these generations of students.” —Lauren Anderson

- “There are other ways to teach children responsibility and time management than completing homework that will most likely be ungraded.” —4th grade social studies teacher

One Teacher’s Take on the Value of Homework: More Cons Than Pros

One 4th grade social studies teacher from North Carolina shared their thoughts with us in detail. We felt they were worth sharing with a wider audience. (Note: We’ve edited and condensed their words for space and clarity.)

Homework Hurts Families

“There are multiple factors that work together that make homework detrimental to students and their families. Children need to spend time with their parents building relationships of trust and respect. It is difficult because during the limited time families have together, they are forced by the schools to give that up to deal with homework.

“Many parents are unable to answer homework questions to help their children as methodology has changed and evolved. Homework becomes a stressful battlefield. Children with ADHD, autism, and other challenges have such a difficult time keeping focus at school. When they have to do additional work at home, there are increased meltdowns and battles, putting further strains on families.”

Homework’s Time Cost

“Children also have less time to complete work at home due to how overscheduled families have become. Children as young as 3rd grade arrive home from their games as late as 10:00 at night. That is often their first opportunity to sit down to complete their work. When they come to school the next day, they become irritable, unfocused, frustrated, and unable to quickly grasp new material.

“In older grades, teachers don’t plan together and don’t understand how much is required of the student to complete each night. If a high school student has six classes and each teacher assigns only 30 minutes of homework each night, that adds up to three hours. I hear of many teachers that each give an hour each night. I don’t see how it is possible for a high school student to complete six hours of homework every night.

“The additional stress of homework for the teacher, students, and families is not worth it. Give families time to spend together, and free up teacher time by not having to hunt down missing work and reviewing what they are not grading. Allow children to have a better bedtime and avoid meltdowns at home, which lead to additional stress, anxiety, and depression.”

We’d love to hear your thoughts—should homework be banned? Join the discussion in the We Are Teachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

You Might Also Like

What’s It Like Teaching in a Rural School?

One-third of America's schools are in rural areas. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

share this!

August 16, 2021

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in

by Sara M Moniuszko

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide-range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas over workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework .

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy work loads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold, says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace, says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework causes, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high-achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school ," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely, but to be more mindful of the type of work students go home with, suggests Kang, who was a high-school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework, I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the last two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic, making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized... sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking assignments up can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

©2021 USA Today Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Investigating the impact of ultralight dark matter on gravitational wave signals

10 hours ago

Scientists find southern killer whales of the Pacific have access to enough food, deepening mystery of their struggles

All-optical switch device paves way for faster fiber-optic communication

Oct 19, 2024

Worms and snails handle the pressure 2,500m below the Pacific surface

Saturday Citations: Brown dwarf actually brown dwarfs; the adaptability of ice-age humans; archaeologists excited

Megastudy tests crowdsourced ideas for reducing political polarization

Controlling sound waves with Klein tunneling improves acoustic signal filtration

Oct 18, 2024

Lignin molecular property discovery could help turn trees into affordable, greener industrial chemicals

American lobster population and habitat preferences shifting, study finds

Cellular senescence research identifies key enzyme to promote healthy aging

Relevant physicsforums posts, help with math terminology in tutorial.

23 hours ago

Help with math terminology #2

How to explain ai to middle schoolers.

Oct 14, 2024

Incandescent bulbs in teaching

Oct 12, 2024

How is Physics taught without Calculus?

Oct 10, 2024

Sources to study basic logic for precocious 10-year old?

Sep 27, 2024

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Smartphones are lowering student's grades, study finds

Aug 18, 2020

Doing homework is associated with change in students' personality

Oct 6, 2017

Scholar suggests ways to craft more effective homework assignments

Oct 1, 2015

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Aug 29, 2019

How much math, science homework is too much?

Mar 23, 2015

Anxiety, depression, burnout rising as college students prepare to return to campus

Jul 26, 2021

Recommended for you

Analysis of approximately 75 million publications finds those employing AI are more likely to be a 'hit paper'

Oct 11, 2024

Carefully exposing children to more misinformation can make them better fact-checkers, study suggests

Review of English-language textbooks from 34 countries reveals persistent pattern of stereotypical gender roles

Oct 9, 2024

AI-generated college admissions essays tend to sound male and privileged, study finds

Oct 2, 2024

Learning mindset could be key to addressing medical students' alarming burnout

Sep 19, 2024

Researchers test ChatGPT, other AI models against real-world students

Sep 16, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

Should homework be banned?

Social media has sparked into life about whether children should be given homework - should students be freed from this daily chore? Dr Gerald Letendre, a professor of education at Pennsylvania State University, investigates.

We’ve all done it: pretended to leave an essay at home, or stayed up until 2am to finish a piece of coursework we’ve been ignoring for weeks. Homework, for some people, is seen as a chore that’s ‘wrecking kids’ or ‘killing parents’, while others think it is an essential part of a well-rounded education. The problem is far from new: public debates about homework have been raging since at least the early-1900s, and recently spilled over into a Twitter feud between Gary Lineker and Piers Morgan.

Ironically, the conversation surrounding homework often ignores the scientific ‘homework’ that researchers have carried out. Many detailed studies have been conducted, and can guide parents, teachers and administrators to make sensible decisions about how much work should be completed by students outside of the classroom.

So why does homework stir up such strong emotions? One reason is that, by its very nature, it is an intrusion of schoolwork into family life. I carried out a study in 2005, and found that the amount of time that children and adolescents spend in school, from nursery right up to the end of compulsory education, has greatly increased over the last century . This means that more of a child’s time is taken up with education, so family time is reduced. This increases pressure on the boundary between the family and the school.

Plus, the amount of homework that students receive appears to be increasing, especially in the early years when parents are keen for their children to play with friends and spend time with the family.

Finally, success in school has become increasingly important to success in life. Parents can use homework to promote, or exercise control over, their child’s academic trajectory, and hopefully ensure their future educational success. But this often leaves parents conflicted – they want their children to be successful in school, but they don’t want them to be stressed or upset because of an unmanageable workload.

However, the issue isn’t simply down to the opinions of parents, children and their teachers – governments also like to get involved. In the autumn of 2012, French president François Hollande hit world headlines after making a comment about banning homework, ostensibly because it promoted inequality. The Chinese government has also toyed with a ban, because of concerns about excessive academic pressure being put on children.

The problem is, some politicians and national administrators regard regulatory policy in education as a solution for a wide array of social, economic and political issues, perhaps without considering the consequences for students and parents.

Does homework work?

Homework seems to generally have a positive effect for high school students, according to an extensive range of empirical literature. For example, Duke University’s Prof Harris Cooper carried out a meta-analysis using data from US schools, covering a period from 1987 to 2003. He found that homework offered a general beneficial impact on test scores and improvements in attitude, with a greater effect seen in older students. But dig deeper into the issue and a complex set of factors quickly emerges, related to how much homework students do, and exactly how they feel about it.

In 2009, Prof Ulrich Trautwein and his team at the University of Tübingen found that in order to establish whether homework is having any effect, researchers must take into account the differences both between and within classes . For example, a teacher may assign a good deal of homework to a lower-level class, producing an association between more homework and lower levels of achievement. Yet, within the same class, individual students may vary significantly in how much homework improves their baseline performance. Plus, there is the fact that some students are simply more efficient at completing their homework than others, and it becomes quite difficult to pinpoint just what type of homework, and how much of it, will affect overall academic performance.

Over the last century, the amount of time that children and adolescents spend in school has greatly increased

Gender is also a major factor. For example, a study of US high school students carried out by Prof Gary Natriello in the 1980s revealed that girls devote more time to homework than boys, while a follow-up study found that US girls tend to spend more time on mathematics homework than boys. Another study, this time of African-American students in the US, found that eighth grade (ages 13-14) girls were more likely to successfully manage both their tasks and emotions around schoolwork, and were more likely to finish homework.

So why do girls seem to respond more positively to homework? One possible answer proposed by Eunsook Hong of the University of Nevada in 2011 is that teachers tend to rate girls’ habits and attitudes towards work more favourably than boys’. This perception could potentially set up a positive feedback loop between teacher expectations and the children’s capacity for academic work based on gender, resulting in girls outperforming boys. All of this makes it particularly difficult to determine the extent to which homework is helping, though it is clear that simply increasing the time spent on assignments does not directly correspond to a universal increase in learning.

Can homework cause damage?

The lack of empirical data supporting homework in the early years of education, along with an emerging trend to assign more work to this age range, appears to be fuelling parental concerns about potential negative effects. But, aside from anecdotes of increased tension in the household, is there any evidence of this? Can doing too much homework actually damage children?

Evidence suggests extreme amounts of homework can indeed have serious effects on students’ health and well-being. A Chinese study carried out in 2010 found a link between excessive homework and sleep disruption: children who had less homework had better routines and more stable sleep schedules. A Canadian study carried out in 2015 by Isabelle Michaud found that high levels of homework were associated with a greater risk of obesity among boys, if they were already feeling stressed about school in general.

For useful revision guides and video clips to assist with learning, visit BBC Bitesize . This is a free online study resource for UK students from early years up to GCSEs and Scottish Highers.

It is also worth noting that too much homework can create negative effects that may undermine any positives. These negative consequences may not only affect the child, but also could also pile on the stress for the whole family, according to a recent study by Robert Pressman of the New England Centre for Pediatric Psychology. Parents were particularly affected when their perception of their own capacity to assist their children decreased.

What then, is the tipping point, and when does homework simply become too much for parents and children? Guidelines typically suggest that children in the first grade (six years old) should have no more that 10 minutes per night, and that this amount should increase by 10 minutes per school year. However, cultural norms may greatly affect what constitutes too much.

A study of children aged between 8 and 10 in Quebec defined high levels of homework as more than 30 minutes a night, but a study in China of children aged 5 to 11 deemed that two or more hours per night was excessive. It is therefore difficult to create a clear standard for what constitutes as too much homework, because cultural differences, school-related stress, and negative emotions within the family all appear to interact with how homework affects children.

Should we stop setting homework?

In my opinion, even though there are potential risks of negative effects, homework should not be banned. Small amounts, assigned with specific learning goals in mind and with proper parental support, can help to improve students’ performance. While some studies have generally found little evidence that homework has a positive effect on young children overall, a 2008 study by Norwegian researcher Marte Rønning found that even some very young children do receive some benefit. So simply banning homework would mean that any particularly gifted or motivated pupils would not be able to benefit from increased study. However, at the earliest ages, very little homework should be assigned. The decisions about how much and what type are best left to teachers and parents.

As a parent, it is important to clarify what goals your child’s teacher has for homework assignments. Teachers can assign work for different reasons – as an academic drill to foster better study habits, and unfortunately, as a punishment. The goals for each assignment should be made clear, and should encourage positive engagement with academic routines.

Parents should inform the teachers of how long the homework is taking, as teachers often incorrectly estimate the amount of time needed to complete an assignment, and how it is affecting household routines. For young children, positive teacher support and feedback is critical in establishing a student’s positive perception of homework and other academic routines. Teachers and parents need to be vigilant and ensure that homework routines do not start to generate patterns of negative interaction that erode students’ motivation.

Likewise, any positive effects of homework are dependent on several complex interactive factors, including the child’s personal motivation, the type of assignment, parental support and teacher goals. Creating an overarching policy to address every single situation is not realistic, and so homework policies tend to be fixated on the time the homework takes to complete. But rather than focusing on this, everyone would be better off if schools worked on fostering stronger communication between parents, teachers and students, allowing them to respond more sensitively to the child’s emotional and academic needs.

- Five brilliant science books for kids

- Will e-learning replace teachers?

Follow Science Focus on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram and Flipboard

Share this article

© Getty Images

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

- PEARSON INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS

Should homework be banned? The big debate

Homework is a polarising topic. it can cause students to feel stressed or anxious. it adds extra pressure on teachers, who are often already struggling with their workloads. and, some parents resent the way homework can cut into family time at home. yet despite this,....

Homework is a polarising topic. It can cause students to feel stressed or anxious. It adds extra pressure on teachers, who are often already struggling with their workloads. And, some parents resent the way homework can cut into family time at home.

Yet despite this, homework is handed out in the vast majority of schools. And, many educators and parents believe it plays a vital role in reinforcing classroom learning. So what does the research say? Does homework really make a big difference in student learning?

Is homework effective in the first place?

This was the question posed by researchers at Rutgers University in a study published last year . Researchers measured student performance on homework and in exams over the course of eleven years – and the results showed an interesting trend.