- Engineering

- Join Newsletter

Our Promise to you

Founded in 2002, our company has been a trusted resource for readers seeking informative and engaging content. Our dedication to quality remains unwavering—and will never change. We follow a strict editorial policy , ensuring that our content is authored by highly qualified professionals and edited by subject matter experts. This guarantees that everything we publish is objective, accurate, and trustworthy.

Over the years, we've refined our approach to cover a wide range of topics, providing readers with reliable and practical advice to enhance their knowledge and skills. That's why millions of readers turn to us each year. Join us in celebrating the joy of learning, guided by standards you can trust.

What is a Research Article?

A research article is a written paper that illustrates an outcome of scientific research with supporting clinical data. This differs from other types of informative articles, such as magazine features or research papers, which typically address the topic in a general scope as a means of introduction. A research article, on the other hand, is written by and for researchers for the purpose of making specific findings known to the scientific community at large. In fact, rather than appearing in a consumer or industry publication, a research article is found exclusively in a peer-reviewed scientific or medical journal, such as The Journal of the American Medical Association , for example.

Another key difference between other papers and a research article is that the latter strictly presents facts, rather than serve as a letter of opinion or a summary of the existing scientific literature. However, most scientific journals simultaneously publish such letters, as well as reviews of the body of existing research methods and findings.

As with any type of targeted writing, there is a protocol to follow when writing a research article in terms of layout. The title, for example, should provide a summary statement that either describes the research or presents the main conclusion drawn from the work. This not only helps the article to be noticed in table of contents in the print version of the scientific journal, but also assists in indexing the article in electronic forms. For instance, PubMed Medline is an online database of published journal material provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine. A lookup of a key word or phrase scans articles published in thousands of scientific journals, and returns search results according to their relevance in the title.

The author or authors of a research article are listed according to their degree of contribution to the work, easily permitting one to identify the lead researcher. The last name followed by first and middle initials format is typically used. When there are many authors presenting the article, only the first three names are usually required to include when referencing or citing the article in another paper. In addition, one author is usually selected to serve as a contact for further information or comment about the article, as well as the party responsible for future amendments or updates. If appropriate, the affiliated university or research facility follows the authors’ names.

While most other forms of articles contain a summary at its end, the process is reversed in a research article. In fact, the summary, known as the abstract, precedes the full content of the paper. There is also a specific formula for its construction. It contains one or two introductory sentences explaining the necessity of the research performed, followed by the methodology used, the results found, and how the researchers applied the results. Finally, the abstract contains a single sentence representing a statement of conclusion of the authors based on these findings.

Editors' Picks

Related Articles

- What is Collaborative Research?

- What is a Research Professor?

- What is a Research Fellow?

Our latest articles, guides, and more, delivered daily.

Understanding Scholarly/Academic Research

- What is Scholarly/Academic Research?

- Structure of a Scholarly Article

- Peer Review & Relevance

- Mixed Methods

- Evaluating Online Sources

- Seminal Works

- Impact Metrics

- Risk of Bias Assessment

- Supplemental Searching

- Open-Access Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

Librarian Team

Video: How to Read a Scholarly Article

Video Credit: Western University

Scholarly research articles or journals share these characteristics:

- scholarly works are considered unbiased within their discipline and are backed up with evidence

- are published in academic, scholarly, scientific or empirical journals

- reports on original research in a specific academic fields

- results are generalizable across populations

- use a research methodology that is replicable

- their authors are most often experts in the field and have their credentials listed

The structure of a scholarly article includes:

- a hypothesis: a proposed question

- a methods section

- conclusions

- suggestions for further research

- a citation reference list

All content in the library is credible, but not all of it is scholarly

Credible vs Scholarly

All content in the Library is credible, but not all of it is scholarly

These content formats are NOT scholarly

- Next: Structure of a Scholarly Article >>

- Last Updated: Nov 11, 2024 12:06 PM

- URL: https://libguides.americansentinel.edu/understanding-scholarly-academic-research

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- French Abstracts

- Portuguese Abstracts

- Spanish Abstracts

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal for Quality in Health Care

- About the International Society for Quality in Health Care

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ISQua

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Primacy of the research question, structure of the paper, writing a research article: advice to beginners.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Thomas V. Perneger, Patricia M. Hudelson, Writing a research article: advice to beginners, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 16, Issue 3, June 2004, Pages 191–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzh053

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Writing research papers does not come naturally to most of us. The typical research paper is a highly codified rhetorical form [ 1 , 2 ]. Knowledge of the rules—some explicit, others implied—goes a long way toward writing a paper that will get accepted in a peer-reviewed journal.

A good research paper addresses a specific research question. The research question—or study objective or main research hypothesis—is the central organizing principle of the paper. Whatever relates to the research question belongs in the paper; the rest doesn’t. This is perhaps obvious when the paper reports on a well planned research project. However, in applied domains such as quality improvement, some papers are written based on projects that were undertaken for operational reasons, and not with the primary aim of producing new knowledge. In such cases, authors should define the main research question a posteriori and design the paper around it.

Generally, only one main research question should be addressed in a paper (secondary but related questions are allowed). If a project allows you to explore several distinct research questions, write several papers. For instance, if you measured the impact of obtaining written consent on patient satisfaction at a specialized clinic using a newly developed questionnaire, you may want to write one paper on the questionnaire development and validation, and another on the impact of the intervention. The idea is not to split results into ‘least publishable units’, a practice that is rightly decried, but rather into ‘optimally publishable units’.

What is a good research question? The key attributes are: (i) specificity; (ii) originality or novelty; and (iii) general relevance to a broad scientific community. The research question should be precise and not merely identify a general area of inquiry. It can often (but not always) be expressed in terms of a possible association between X and Y in a population Z, for example ‘we examined whether providing patients about to be discharged from the hospital with written information about their medications would improve their compliance with the treatment 1 month later’. A study does not necessarily have to break completely new ground, but it should extend previous knowledge in a useful way, or alternatively refute existing knowledge. Finally, the question should be of interest to others who work in the same scientific area. The latter requirement is more challenging for those who work in applied science than for basic scientists. While it may safely be assumed that the human genome is the same worldwide, whether the results of a local quality improvement project have wider relevance requires careful consideration and argument.

Once the research question is clearly defined, writing the paper becomes considerably easier. The paper will ask the question, then answer it. The key to successful scientific writing is getting the structure of the paper right. The basic structure of a typical research paper is the sequence of Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion (sometimes abbreviated as IMRAD). Each section addresses a different objective. The authors state: (i) the problem they intend to address—in other terms, the research question—in the Introduction; (ii) what they did to answer the question in the Methods section; (iii) what they observed in the Results section; and (iv) what they think the results mean in the Discussion.

In turn, each basic section addresses several topics, and may be divided into subsections (Table 1 ). In the Introduction, the authors should explain the rationale and background to the study. What is the research question, and why is it important to ask it? While it is neither necessary nor desirable to provide a full-blown review of the literature as a prelude to the study, it is helpful to situate the study within some larger field of enquiry. The research question should always be spelled out, and not merely left for the reader to guess.

Typical structure of a research paper

The Methods section should provide the readers with sufficient detail about the study methods to be able to reproduce the study if so desired. Thus, this section should be specific, concrete, technical, and fairly detailed. The study setting, the sampling strategy used, instruments, data collection methods, and analysis strategies should be described. In the case of qualitative research studies, it is also useful to tell the reader which research tradition the study utilizes and to link the choice of methodological strategies with the research goals [ 3 ].

The Results section is typically fairly straightforward and factual. All results that relate to the research question should be given in detail, including simple counts and percentages. Resist the temptation to demonstrate analytic ability and the richness of the dataset by providing numerous tables of non-essential results.

The Discussion section allows the most freedom. This is why the Discussion is the most difficult to write, and is often the weakest part of a paper. Structured Discussion sections have been proposed by some journal editors [ 4 ]. While strict adherence to such rules may not be necessary, following a plan such as that proposed in Table 1 may help the novice writer stay on track.

References should be used wisely. Key assertions should be referenced, as well as the methods and instruments used. However, unless the paper is a comprehensive review of a topic, there is no need to be exhaustive. Also, references to unpublished work, to documents in the grey literature (technical reports), or to any source that the reader will have difficulty finding or understanding should be avoided.

Having the structure of the paper in place is a good start. However, there are many details that have to be attended to while writing. An obvious recommendation is to read, and follow, the instructions to authors published by the journal (typically found on the journal’s website). Another concerns non-native writers of English: do have a native speaker edit the manuscript. A paper usually goes through several drafts before it is submitted. When revising a paper, it is useful to keep an eye out for the most common mistakes (Table 2 ). If you avoid all those, your paper should be in good shape.

Common mistakes seen in manuscripts submitted to this journal

Huth EJ . How to Write and Publish Papers in the Medical Sciences , 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1990 .

Browner WS . Publishing and Presenting Clinical Research . Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999 .

Devers KJ , Frankel RM. Getting qualitative research published. Educ Health 2001 ; 14 : 109 –117.

Docherty M , Smith R. The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers. Br Med J 1999 ; 318 : 1224 –1225.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Hirsh Health Sciences

- Webster Veterinary

Guide to Scholarly Articles

Getting started, what makes an article scholarly, why does this matter.

- Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles

- Types of Scholarly Articles

- Anatomy of Scholarly Articles

- Tips for Reading Scholarly Articles

Scholarship is a conversation.

That conversation is often found in the form of published materials such as books, essays, and articles. Here, we will focus on scholarly articles because scholarly articles often contain the most current scholarly conversation.

After reading through this guide on scholarly articles you will be able to identify and describe different types of scholarly articles. This will allow you to navigate the scholarly conversation more effectively which in turn will make your research more productive.

The distinguishing feature of a scholarly article is not that it is without errors; rather, a scholarly article is distinguished by a few characteristics which reduce the likelihood of errors. For our purposes, those characteristics are expert authors , peer-review , and citations .

- Expert Authors - Authority is constructed and contextual. In other words it is built through academic credentialing and lived experience. Scholarly articles are written by experts in their respective fields rather than generalists. Expertise often comes in the form of academic credentials. For example, an article about the spread of various diseases should be written by someone with credentials and experience in immunology or public health.

- Peer-review - Peer-review is the process whereby scholarly articles are vetted and improved. In this process an author submits an article to a journal for publication. However, before publication, an editor of the journal will send the article to other experts in the field to solicit their informed and professional opinions of it. These reviewers (sometimes called referees) will give the editor feedback regarding the quality of the article. Based on this process, articles may be published as is, published after specific changes are made, or not published at all.

- Citations - One of the key differences between scholarly articles and other kinds of articles is that the former contain citations and bibliographies. These citations allow the reader to follow up on the author's sources to verify or dispute the author's claim.

There is a well-known axiom that says "Garbage in, garbage out." In the context of research this means that the quality of your research output is dependent on the information sources that go into you own research. Generally speaking, the information found in scholarly articles is more reliable than information found elsewhere. It is important to identify scholarly articles and prioritize them in your own research.

- Next: Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles >>

- Last Updated: Aug 23, 2023 8:53 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/scholarly-articles

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Evaluating Resources: Research Articles

Research articles.

A research article is a journal article in which the authors report on the research they did. Research articles are always primary sources. Whether or not a research article is peer reviewed depends on the journal that publishes it.

Published research articles follow a predictable pattern and will contain most, if not all, of the sections listed below. However, the names for these sections may vary.

- Title & Author(s)

- Introduction

- Methodology

To learn about the different parts of a research article, please view this tutorial:

Short video: How to Read Scholarly Articles

Learn some tips on how to efficiently read scholarly articles.

Video: How to Read a Scholarly Article

(4 min 16 sec) Recorded August 2019 Transcript

More information

The Academic Skills Center and the Writing Center both have helpful resources on critical and academic reading that can further help you understand and evaluate research articles.

- Academic Skills Center Guide: Developing Your Reading Skills

- Academic Skills Center Webinar Archive: Savvy Strategies for Academic Reading

If you'd like to learn how to find research articles in the Library, you can view this Quick Answer.

- Quick Answer: How do I find research articles?

- Previous Page: Primary & Secondary Sources

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

What is research?

- Published: 16 December 2021

- Volume 20 , pages 407–411, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Dong-Wook Song 1

40k Accesses

8 Citations

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is nothing so practical as a good theory. Kurt Lewin (1890–1947)

One of the duties to be conducted by an editor-in-chief is to make an editorial decision by accepting, requesting for revision(s) or rejecting a submitted manuscript after a round of reviewing processes or even before putting it into the reviewing procedure: that is desk rejection. See more about the decision-making process in the previous editorial (Song 2020b ). Authors of rejected manuscripts are likely to think of why their works are refused to be published at a peer-reviewed journal. In this editorial, your editor-in-chief attempts to express an overview of his perspective and/or philosophy on the related matter.

Research in definition

In his well-known book What is history? , Carr ( 1961 ) defines the history as a never-ending conversation between the past and the present. Similarly, the authors of The Craft of Research put their definition of the research as a conversation by helping you (as a researcher) and your community (i.e. learned societies) free us (i.e. general public) from ignorance, prejudice and the half-baked ideas that so many charlatans try to impose on us (Booth et al., p. 11). Furthermore, Huff ( 2009 ) starts her well-articulated book Designing Research for Publication with the chapter headed ‘Finding the Right Conversation’. The chapter is composed of such sub-headings as ‘scholarship as a social, sensemaking activity’, ‘identifying scholarly conversations’, ‘choosing your conversation’, ‘developing a scholarly identity that informs scholarly choices’ and ‘balancing attraction, agreement and disagreement’.

All the three books, being widely recognised and used for educating learned people like you, do commonly mention the term ‘conversation’ in a way to elucidating research. When googling further for more, you will find the following definition given by the Western Sydney University ( 2021 ):

“Research is defined as the creation of new knowledge and/or the use of existing knowledge in a new and creative way so as to generate new concepts, methodologies and understandings. This could include synthesis and analysis of previous research to the extent that it leads to new and creative outcomes.”

Putting all those explications into a single frame, one could interpret that the research (more preciously, academic or scientific research) has to do with (i) linking (that is a ‘conversation’) what has been done (the past) with what has to be done (the present and/or future) in a way to generate new knowledge and (ii) objectifying what you are doing in a way to contribute to your chosen field (or community).

The former is named a literature review, while the latter a methodology. While acknowledging that these two activities are deemed to need further discussion in a detailed manner, Footnote 1 the current editorial aims to proceed towards the definition and types of research in a context of maritime studies as an applied science.

Applied research in definition

In a simple but distinctive manner, Booth et al. ( 2016 , pp. 51–65) define pure (or basic) and applied research as “We call pure research when it addresses a conceptual problem that does not bear directly on any practical situation in the world….. [we] call applied research when it addresses a conceptual problem that does have practical consequences…… ‘[what] we should think ’ is concerned with the conceptual problem, while ‘what we should do ’ is with the practical problem.” [emphases inserted].

On the same matter, Flexner ( 1939 ) went even further by quoting the Nobel laureate George Porter saying the two types as applied and ‘ not-yet-applied ’ research: the latter being regarded as pure research (or blue sky research). In his context, findings from pure research are treated by general public as ‘useless knowledge’ until they become applied for human’s wellbeing (that is the useless knowledge has been eventually transformed into being useful). He did, however, make an emphasis on the fact that pure scientists, like Albert Einstein, had not considered the practicality nor applicability of their theory when launching their exploration; they did simply out of curiosities. Applied scientists are those who see a potential by examining theories developed by pure scientists and apply them to human’s welfares; those who developed GPS from the Einstein’s theory are those categorised ones in this context.

Turning on to the domain of social sciences, we are still able to observe the similar trajectory that has been developed. For example, Kurt Lewin (1890–1947), whose works in the field of applied psychology or organisation and management sciences are widely cited, did firmly claim that those working in practice-geared disciplines are to be a practical theorist . This assertion is vindicated by his most frequently cited sentence as quoted in the beginning of this editorial. His stand on the nature of applied research does clearly indicate that theories and/or concepts are a starting point for applied scientists to commence their journey of investigation.

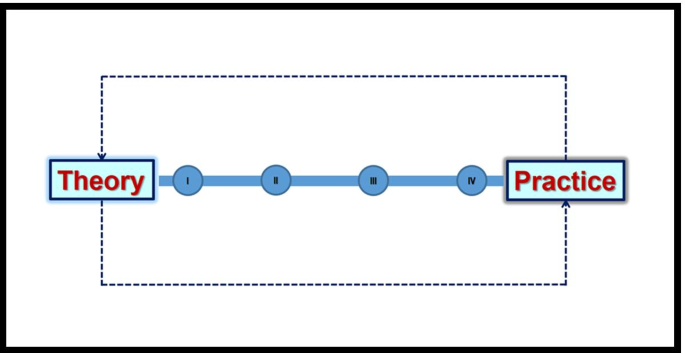

Types of research

Having the aforementioned points in mind, this editorial makes an effort to classify the types of applied research using the following diagram. Footnote 2 In a simple way, we are to generate a concept on our way towards theory by carefully observing the practice: so-called theory-building. Consequently, the developed concepts/theories are to be tested in an incremental manner to better reflect the practice: named ‘theory-testing’. In this sense, we could illustrate the related mechanism between theory on one side and practice on the other in a either direct or indirect format (expressed in a dotted line in the figure). In other words, some theories remain in a stage where they have not yet applied or related to the practice, while others are practically attached to the world.

The spectrum spread across the line between theory and practice could be approximately pointed into four spots (I to IV) in terms of nature of applied research.

Type I is a theory-focused research, while Type IV is a practice-driven one. Most of the applied research could fall into somewhere between the two—Type II or Type III. Specifically speaking, the editorial defines the Type I to be ‘close-to-blue-sky-research’ as it conducts for the sake of developing, enhancing or improving related concept/theory. The Type II could be the one that performs theory-dominated and practice-considered research. Its example could include, amongst others, those researches in responding to the call for applications commissioned by research councils, non-profit-making foundations or similar institutes whose interests are in making the world a better place by enhancing knowledge beneficial to the wide public. Research is considered principally as public goods under this category. The editorial names it ‘responsive research’ . The Type III could be the one that conducts the research having specific beneficiaries in mind from the beginning. The editorial calls the Type III as ‘contracted research’ including consultancies. Finally, the Type IV would be the in-house research executed exclusively for their own interest, the outputs of which are often produced in a form of company or organisation reports. Some of those reports are at times used either partially or fully for the purpose of promoting companies/organisations in question. This Type IV can be termed ‘in-house research’ .

Expected types of papers

Having once again defined the discipline of maritime studies in a broad sense (see more at Song 2020a ) as an applied science, the WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs (JOMA) as a peer-reviewed ‘academic’ dissemination outlet would welcome the Type I and Type II papers with the expectations that the Typed-II-papers could be majority. At the same time, however, JOMA as an ‘industry’-geared outlet would also welcome the Type III papers, subject to those works to be objectified Footnote 3 prior to submission to the journal for consideration. The Typed-IV-papers could be treated as a special case under the title of views from industrial professionals: that is the issues of contemporary interest as indicated in the editorial (Song 2020a ). Those authoritative voices from the industry would be ‘invited’ to express their views for the case of this Type IV of papers.

Final words

Assuming that most of the present and prospective authors, readers, reviewers or other stakeholders for JOMA are an ‘academic’ applied researcher, the editorial would like to summarise what has been discussed in the section by quoting the following point made by Kurt Lewin (1890–1947) who claimed himself as a practical theorist.

“Theory should fulfil two main functions: first, it should account for what is known; second, it should point out the way to new knowledge. ….. [research] should therefore be undertaken with the purpose of testing theoretical concepts, instead of merely collecting and analysing elemental facts or classifying behaviour statistically.” (Marrow 1969 , p. 30)

Having attempted to discuss what might be sensitive, subjective or perspective-biased to some, as usual, your editor-in-chief looks forward to receiving comments and feedbacks from you as a current and future contributor to the discipline of maritime studies in general and JOMA in specific. We could then collectively develop our beloved maritime communities as a backbone to the global economies. Please drop him an email whenever you feel it could be helpful and useful to the common good of the journal and/or maritime communities.

Dong-Wook Song

Editor-in-Chief

These issues will be also discussed in the forthcoming editorials in due course.

The editorial does fully acknowledge and appreciate that expressing the complexity involved with dynamism between theory and practice as a dichotomised form would be too simplistic to be convincing. The current effort is, however, made to convey the editor’s perspective and philosophy towards maritime studies (as a branch of applied research) as simplest as possible.

The subject of ‘how to objectify’ will be another topic to be dealt with at the forthcoming editorial in due time.

Booth W, Colomb G, Williams J, Bizup J, FitzGerald W (2016) The craft of research, 4th edn. University of Chicago Press, London

Google Scholar

Carr E (1961[2001]) What is history? Palgrave Macmillan, London

Flexner A (1939[2017]) The usefulness of useless knowledge. Princeton University Press, Oxford

Huff A (2009) Designing research for publication. Sage Publications, London

Marrow A (1969) The practical theorist: the life and work of Kurt Lewin. Basic Books, London

Song D-W (2020a) Editorial: looking back for the future. WMU J Marit Aff 19(1):1–3

Article Google Scholar

Song D-W (2020b) Editorial: decision-making process for journal articles. WMU J Marit Aff 19(2):159–162

Western Sydney University (2021) Definition of Research. https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/research/researchers/preparing_a_grant_application/dest_definition_of_research. Accessed on 15th November

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

World Maritime University, Malmö, Sweden

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dong-Wook Song .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Song, DW. What is research?. WMU J Marit Affairs 20 , 407–411 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-021-00256-w

Download citation

Published : 16 December 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-021-00256-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

ENGL 01A Epstein-Corbin

- Choosing Sources

- Background Information

- Scholarly Books

- Scholarly and Popular Articles

Sciences and Social Sciences

Arts and humanities, scanning and evaluating scholarly articles.

- About Library Databases

- Suggested Databases

- Database Tutorials

- Database Search Strategies

- Citing and Getting Research Help

Scholarly journal articles include original studies and review articles that contribute to the current scholarship on a given topic.

The list below describes the components of scholarly journal articles in the Sciences and Social Sciences. The majority of articles in these disciplines will have the sections listed below.

- Abstract: brief summary of the article, including research question, methodology and results.

- Introduction: background information about the topic, leading up to why this study is being done, and may include a brief literature review.

- Methods: description of how the study procedures, set-up and how data was collected.

- Results/Findings: presentation of the data from the study; this section often includes tables, charts, or other visualizations of the data.

- Discussion: analysis of the data and how the study relates to existing knowledge of the topic; the authors evaluate whether their results answer their research question.

- Conclusion: the authors wrap up the article by discussion how their study contributes to the research on this topic and outline future potential research questions or studies.

- References: list of resources that the authors consulted when developing their research and subsequently cited in their article.

- Pesticides in House Dust from Urban and Farmworker Households in California: An Observational Measurement Study From the journal Environmental Health.

Scholarly journal articles in the Arts and Humanities are set up differently than in the Sciences and Social Sciences. Articles may read more like essays, rather than reports on scientific experiments.

In the humanities, scholars are not conducting experiments on participants but rather are making logical arguments based on the evidence they have researched and analyzed.

In literature, for example, a scholar may be studying a particular novel of an author. In history, a scholar may look at the primary source documents from the time period they are studying.

The following sections are generally included in humanities scholarly articles, although they may not be clearly marked or labeled.

- Abstract: a summary of the research provided at the beginning of the article, although sometimes articles do not have an abstract.

- Introduction: provides background information for the topic being studied; the article's thesis will be found in the introduction, and may also include a brief literature review.

- Discussion/Conclusion: the discussion likely runs through the entire article and is the main component of the article providing analysis, criticism, etc.; the conclusion wraps up the article; both sections usually are not labeled.

- Regulation of Pesticides: A Comparative Analysis From the journal Science & Public Policy

" How to Quickly Scan and Evaluate a Scholarly Article " (3:12) by QVCC Library is licensed under CC BY 3.0

- << Previous: Scholarly and Popular Articles

- Next: About Library Databases >>

- Last Updated: Nov 12, 2024 6:59 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mccd.edu/engl01a_epstein-corbin

Organizing Research for Arts and Humanities Papers and Theses

- General Guide Information

- Developing a Topic

- What are Primary and Secondary Sources

- What are Scholarly and Non-Scholarly Sources

- Writing an Abstract

- Writing Academic Book Reviews

- Writing A Literature Review

- Using Images and other Media

What is a Scholarly Source

Both scholarly and non-scholarly materials have a place in arts and humanities research. Their use, and even their definition, depends on the context of the research project.

Books, conference publications, and academic journal articles, regardless of whether they are print-based or electronic, are common types of scholarly materials, which share the following characteristics:

- The authors are scholars or researchers with known affiliations and educational/research credentials

- The authors cite other sources, be they primary or secondary. Many scholarly publications include citations to other sources and bibliographies

- The language used is either academic or complex, and may include disciplinary or theoretical lingo

- The publisher is a scholarly press that practices editorial review to ensure that content and context adhere to the expected research parameters

- The intended audience is composed of researchers, scholars, academics, and other informed or specialized readership.

Scholarly and academic journals, which are periodic publications that contain articles, have additional characteristics, such as:

- An editorial process that is peer reviewed or refereed

- They publish long articles (essays that are ordinarily at least 10 pages), which may also inlcude an abstract. Scholarly journals often publish essay-length scholarly book reviews, which include citations to other sources

- Scholarly journals are published relatively infrequently, usually quarterly (once every 3 months), semi-annually (twice a year), or annually (once a year).

Use the points above to evaluate the scholarly nature of internet sites. It helps if the site's URL ends in .edu.

So far, so good.

But things are not always clear cut, and here are some complexities to keep in mind:

- Scholarly materials in art, architecture, theater, cinema, and related fields often include images

- Images may constitute a large portion of such publications, with text used to illustrate, contextualize, critique, or explicate the visual component

- There may be fewer citations to other sources, and the bibliographies may be shorter

- The author may be a creative practitioner, such as, for example, an architect or a playwright

- The author may be a multi-disciplinary intellectual of a transnational stature, who does not rely on the commonly acceptable scholarly apparatus. For example, works by Roland Barthes, which lack footnotes or bibliographies, are considered scholarly. An essay by Jean Baudrillard about Disneyworld, which appeared in the French daily newspaper Liberation , may also be considered scholarly, given the stature of the author and his importance in the development of a particular theoretical analysis of popular culture.

What is a Non-Scholarly Source

Non-scholarly materials usually consiste of, but are not limited to:

- News sources, newspapers, and materials that are time-based and get updated frequently

- Sources that are primarily journalistic

- Sources written for a broad readership

- Sources that are advocacy or opinion-based. Keep in mind that opinion-based articles, scholarly news, and letters to the editor get published in scholarly journals alongside scholarly articles.

- Sources that lack references to other sources

- Data and statistical publications and compilations

- Primary sources

- Trade and professional sources

- Reviews of books, movies, plays, or gallery and art shows, that are not essay-length and that do not inlcude a bibliographic context

Non-scholarly materials are legitimate sources for research in the arts and humanities, and should be used in context, just as scholarly sources must be used in context. For example, if you are researching something that happened very recently, you will have to, by necessity, use non-scholarly sources. It takes time for scholarship to be written, reviewed by peers, and published. In addition, there is no guarantee that your particular topic is of interest to other scholars. In such cases, look for scholarly materials in related areas that can provide a critical framework for you to use in analyzing your topic.

Remember to keep track of your sources, regardless of the stage of your research. The USC Libraries have an excellent guide to citation styles and to citation management software .

- << Previous: What are Primary and Secondary Sources

- Next: Writing an Abstract >>

- Last Updated: Nov 14, 2024 10:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/ah_writing

COMMENTS

Research articles represent the ultimate, final product of a scientific study. You should assume that your published work will be indefinitely available for anyone to access. • Research articles always consist of a title, abstract, introduction, materials and methods, results, discussion, and references sections, and many include a supplemental materials section. There are strategies for ...

A research article is a written paper that illustrates an outcome of scientific research with supporting clinical data. This differs from other types of informative articles, such as magazine features or research papers, which typically address the topic in a general scope as a means of introduction. A research article, on the other hand, is ...

Scholarly research articles or journals share these characteristics: scholarly works are considered unbiased within their discipline and are backed up with evidence; are published in academic, scholarly, scientific or empirical journals; reports on original research in a specific academic fields; results are generalizable across populations

The typical research paper is a highly codified rhetorical form [1, 2]. Knowledge of the rules—some explicit, others implied—goes a long way toward writing a paper that will get accepted in a peer-reviewed journal. Primacy of the research question. A good research paper addresses a specific research question.

Step 1: Source. The article is most likely scholarly if: You found the article in a library database or Google Scholar. The journal the article appears in is peer-reviewed. Move to Step 2: Authors. Step 2: Authors. The source is most likely scholarly if: The authors' credentials are provided. The authors are affiliated with a university or ...

Scholarship is a conversation. That conversation is often found in the form of published materials such as books, essays, and articles. Here, we will focus on scholarly articles because scholarly articles often contain the most current scholarly conversation. After reading through this guide on scholarly articles you will be able to identify ...

Research articles. A research article is a journal article in which the authors report on the research they did. Research articles are always primary sources. Whether or not a research article is peer reviewed depends on the journal that publishes it. Published research articles follow a predictable pattern and will contain most, if not all, of ...

When googling further for more, you will find the following definition given by the Western Sydney University (2021): "Research is defined as the creation of new knowledge and/or the use of existing knowledge in a new and creative way so as to generate new concepts, methodologies and understandings. This could include synthesis and analysis ...

The list below describes the components of scholarly journal articles in the Sciences and Social Sciences. The majority of articles in these disciplines will have the sections listed below. Abstract: brief summary of the article, including research question, methodology and results. Introduction: background information about the topic, leading ...

Both scholarly and non-scholarly materials have a place in arts and humanities research. Their use, and even their definition, depends on the context of the research project. Books, conference publications, and academic journal articles, regardless of whether they are print-based or electronic, are common types of scholarly materials, which ...