Bridging the Gap: Overcome these 7 flaws in descriptive research design

Descriptive research design is a powerful tool used by scientists and researchers to gather information about a particular group or phenomenon. This type of research provides a detailed and accurate picture of the characteristics and behaviors of a particular population or subject. By observing and collecting data on a given topic, descriptive research helps researchers gain a deeper understanding of a specific issue and provides valuable insights that can inform future studies.

In this blog, we will explore the definition, characteristics, and common flaws in descriptive research design, and provide tips on how to avoid these pitfalls to produce high-quality results. Whether you are a seasoned researcher or a student just starting, understanding the fundamentals of descriptive research design is essential to conducting successful scientific studies.

Table of Contents

What Is Descriptive Research Design?

The descriptive research design involves observing and collecting data on a given topic without attempting to infer cause-and-effect relationships. The goal of descriptive research is to provide a comprehensive and accurate picture of the population or phenomenon being studied and to describe the relationships, patterns, and trends that exist within the data.

Descriptive research methods can include surveys, observational studies , and case studies, and the data collected can be qualitative or quantitative . The findings from descriptive research provide valuable insights and inform future research, but do not establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Importance of Descriptive Research in Scientific Studies

1. understanding of a population or phenomenon.

Descriptive research provides a comprehensive picture of the characteristics and behaviors of a particular population or phenomenon, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the topic.

2. Baseline Information

The information gathered through descriptive research can serve as a baseline for future research and provide a foundation for further studies.

3. Informative Data

Descriptive research can provide valuable information and insights into a particular topic, which can inform future research, policy decisions, and programs.

4. Sampling Validation

Descriptive research can be used to validate sampling methods and to help researchers determine the best approach for their study.

5. Cost Effective

Descriptive research is often less expensive and less time-consuming than other research methods , making it a cost-effective way to gather information about a particular population or phenomenon.

6. Easy to Replicate

Descriptive research is straightforward to replicate, making it a reliable way to gather and compare information from multiple sources.

Key Characteristics of Descriptive Research Design

The primary purpose of descriptive research is to describe the characteristics, behaviors, and attributes of a particular population or phenomenon.

2. Participants and Sampling

Descriptive research studies a particular population or sample that is representative of the larger population being studied. Furthermore, sampling methods can include convenience, stratified, or random sampling.

3. Data Collection Techniques

Descriptive research typically involves the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data through methods such as surveys, observational studies, case studies, or focus groups.

4. Data Analysis

Descriptive research data is analyzed to identify patterns, relationships, and trends within the data. Statistical techniques , such as frequency distributions and descriptive statistics, are commonly used to summarize and describe the data.

5. Focus on Description

Descriptive research is focused on describing and summarizing the characteristics of a particular population or phenomenon. It does not make causal inferences.

6. Non-Experimental

Descriptive research is non-experimental, meaning that the researcher does not manipulate variables or control conditions. The researcher simply observes and collects data on the population or phenomenon being studied.

When Can a Researcher Conduct Descriptive Research?

A researcher can conduct descriptive research in the following situations:

- To better understand a particular population or phenomenon

- To describe the relationships between variables

- To describe patterns and trends

- To validate sampling methods and determine the best approach for a study

- To compare data from multiple sources.

Types of Descriptive Research Design

1. survey research.

Surveys are a type of descriptive research that involves collecting data through self-administered or interviewer-administered questionnaires. Additionally, they can be administered in-person, by mail, or online, and can collect both qualitative and quantitative data.

2. Observational Research

Observational research involves observing and collecting data on a particular population or phenomenon without manipulating variables or controlling conditions. It can be conducted in naturalistic settings or controlled laboratory settings.

3. Case Study Research

Case study research is a type of descriptive research that focuses on a single individual, group, or event. It involves collecting detailed information on the subject through a variety of methods, including interviews, observations, and examination of documents.

4. Focus Group Research

Focus group research involves bringing together a small group of people to discuss a particular topic or product. Furthermore, the group is usually moderated by a researcher and the discussion is recorded for later analysis.

5. Ethnographic Research

Ethnographic research involves conducting detailed observations of a particular culture or community. It is often used to gain a deep understanding of the beliefs, behaviors, and practices of a particular group.

Advantages of Descriptive Research Design

1. provides a comprehensive understanding.

Descriptive research provides a comprehensive picture of the characteristics, behaviors, and attributes of a particular population or phenomenon, which can be useful in informing future research and policy decisions.

2. Non-invasive

Descriptive research is non-invasive and does not manipulate variables or control conditions, making it a suitable method for sensitive or ethical concerns.

3. Flexibility

Descriptive research allows for a wide range of data collection methods , including surveys, observational studies, case studies, and focus groups, making it a flexible and versatile research method.

4. Cost-effective

Descriptive research is often less expensive and less time-consuming than other research methods. Moreover, it gives a cost-effective option to many researchers.

5. Easy to Replicate

Descriptive research is easy to replicate, making it a reliable way to gather and compare information from multiple sources.

6. Informs Future Research

The insights gained from a descriptive research can inform future research and inform policy decisions and programs.

Disadvantages of Descriptive Research Design

1. limited scope.

Descriptive research only provides a snapshot of the current situation and cannot establish cause-and-effect relationships.

2. Dependence on Existing Data

Descriptive research relies on existing data, which may not always be comprehensive or accurate.

3. Lack of Control

Researchers have no control over the variables in descriptive research, which can limit the conclusions that can be drawn.

The researcher’s own biases and preconceptions can influence the interpretation of the data.

5. Lack of Generalizability

Descriptive research findings may not be applicable to other populations or situations.

6. Lack of Depth

Descriptive research provides a surface-level understanding of a phenomenon, rather than a deep understanding.

7. Time-consuming

Descriptive research often requires a large amount of data collection and analysis, which can be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

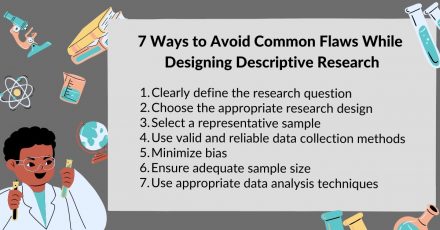

7 Ways to Avoid Common Flaws While Designing Descriptive Research

1. Clearly define the research question

A clearly defined research question is the foundation of any research study, and it is important to ensure that the question is both specific and relevant to the topic being studied.

2. Choose the appropriate research design

Choosing the appropriate research design for a study is crucial to the success of the study. Moreover, researchers should choose a design that best fits the research question and the type of data needed to answer it.

3. Select a representative sample

Selecting a representative sample is important to ensure that the findings of the study are generalizable to the population being studied. Researchers should use a sampling method that provides a random and representative sample of the population.

4. Use valid and reliable data collection methods

Using valid and reliable data collection methods is important to ensure that the data collected is accurate and can be used to answer the research question. Researchers should choose methods that are appropriate for the study and that can be administered consistently and systematically.

5. Minimize bias

Bias can significantly impact the validity and reliability of research findings. Furthermore, it is important to minimize bias in all aspects of the study, from the selection of participants to the analysis of data.

6. Ensure adequate sample size

An adequate sample size is important to ensure that the results of the study are statistically significant and can be generalized to the population being studied.

7. Use appropriate data analysis techniques

The appropriate data analysis technique depends on the type of data collected and the research question being asked. Researchers should choose techniques that are appropriate for the data and the question being asked.

Have you worked on descriptive research designs? How was your experience creating a descriptive design? What challenges did you face? Do write to us or leave a comment below and share your insights on descriptive research designs!

extremely very educative

Indeed very educative and useful. Well explained. Thank you

Simple,easy to understand

Excellent and easy to understand queries and questions get answered easily. Its rather clear than any confusion. Thanks a million Shritika Sirisilla.

Easy to understand. Well written , educative and informative

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Promoting Research

Graphical Abstracts Vs. Infographics: Best practices for using visual illustrations for increased research impact

Dr. Sarah Chen stared at her computer screen, her eyes staring at her recently published…

- Publishing Research

10 Tips to Prevent Research Papers From Being Retracted

Research paper retractions represent a critical event in the scientific community. When a published article…

- Industry News

Google Releases 2024 Scholar Metrics, Evaluates Impact of Scholarly Articles

Google has released its 2024 Scholar Metrics, assessing scholarly articles from 2019 to 2023. This…

![descriptive research design limitations What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- AI in Academia

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What factors would influence the future of open access (OA) publishing?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples

Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples

Published on May 15, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Descriptive research aims to accurately and systematically describe a population, situation or phenomenon. It can answer what , where , when and how questions , but not why questions.

A descriptive research design can use a wide variety of research methods to investigate one or more variables . Unlike in experimental research , the researcher does not control or manipulate any of the variables, but only observes and measures them.

Table of contents

When to use a descriptive research design, descriptive research methods, other interesting articles.

Descriptive research is an appropriate choice when the research aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories.

It is useful when not much is known yet about the topic or problem. Before you can research why something happens, you need to understand how, when and where it happens.

Descriptive research question examples

- How has the Amsterdam housing market changed over the past 20 years?

- Do customers of company X prefer product X or product Y?

- What are the main genetic, behavioural and morphological differences between European wildcats and domestic cats?

- What are the most popular online news sources among under-18s?

- How prevalent is disease A in population B?

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Descriptive research is usually defined as a type of quantitative research , though qualitative research can also be used for descriptive purposes. The research design should be carefully developed to ensure that the results are valid and reliable .

Survey research allows you to gather large volumes of data that can be analyzed for frequencies, averages and patterns. Common uses of surveys include:

- Describing the demographics of a country or region

- Gauging public opinion on political and social topics

- Evaluating satisfaction with a company’s products or an organization’s services

Observations

Observations allow you to gather data on behaviours and phenomena without having to rely on the honesty and accuracy of respondents. This method is often used by psychological, social and market researchers to understand how people act in real-life situations.

Observation of physical entities and phenomena is also an important part of research in the natural sciences. Before you can develop testable hypotheses , models or theories, it’s necessary to observe and systematically describe the subject under investigation.

Case studies

A case study can be used to describe the characteristics of a specific subject (such as a person, group, event or organization). Instead of gathering a large volume of data to identify patterns across time or location, case studies gather detailed data to identify the characteristics of a narrowly defined subject.

Rather than aiming to describe generalizable facts, case studies often focus on unusual or interesting cases that challenge assumptions, add complexity, or reveal something new about a research problem .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved October 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/descriptive-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is quantitative research | definition, uses & methods, correlational research | when & how to use, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Child Care and Early Education Research Connections

Descriptive research studies.

Descriptive research is a type of research that is used to describe the characteristics of a population. It collects data that are used to answer a wide range of what, when, and how questions pertaining to a particular population or group. For example, descriptive studies might be used to answer questions such as: What percentage of Head Start teachers have a bachelor's degree or higher? What is the average reading ability of 5-year-olds when they first enter kindergarten? What kinds of math activities are used in early childhood programs? When do children first receive regular child care from someone other than their parents? When are children with developmental disabilities first diagnosed and when do they first receive services? What factors do programs consider when making decisions about the type of assessments that will be used to assess the skills of the children in their programs? How do the types of services children receive from their early childhood program change as children age?

Descriptive research does not answer questions about why a certain phenomenon occurs or what the causes are. Answers to such questions are best obtained from randomized and quasi-experimental studies . However, data from descriptive studies can be used to examine the relationships (correlations) among variables. While the findings from correlational analyses are not evidence of causality, they can help to distinguish variables that may be important in explaining a phenomenon from those that are not. Thus, descriptive research is often used to generate hypotheses that should be tested using more rigorous designs.

A variety of data collection methods may be used alone or in combination to answer the types of questions guiding descriptive research. Some of the more common methods include surveys, interviews, observations, case studies, and portfolios. The data collected through these methods can be either quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative data are typically analyzed and presenting using descriptive statistics . Using quantitative data, researchers may describe the characteristics of a sample or population in terms of percentages (e.g., percentage of population that belong to different racial/ethnic groups, percentage of low-income families that receive different government services) or averages (e.g., average household income, average scores of reading, mathematics and language assessments). Quantitative data, such as narrative data collected as part of a case study, may be used to organize, classify, and used to identify patterns of behaviors, attitudes, and other characteristics of groups.

Descriptive studies have an important role in early care and education research. Studies such as the National Survey of Early Care and Education and the National Household Education Surveys Program have greatly increased our knowledge of the supply of and demand for child care in the U.S. The Head Start Family and Child Experiences Survey and the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Program have provided researchers, policy makers and practitioners with rich information about school readiness skills of children in the U.S.

Each of the methods used to collect descriptive data have their own strengths and limitations. The following are some of the strengths and limitations of descriptive research studies in general.

Study participants are questioned or observed in a natural setting (e.g., their homes, child care or educational settings).

Study data can be used to identify the prevalence of particular problems and the need for new or additional services to address these problems.

Descriptive research may identify areas in need of additional research and relationships between variables that require future study. Descriptive research is often referred to as "hypothesis generating research."

Depending on the data collection method used, descriptive studies can generate rich datasets on large and diverse samples.

Limitations:

Descriptive studies cannot be used to establish cause and effect relationships.

Respondents may not be truthful when answering survey questions or may give socially desirable responses.

The choice and wording of questions on a questionnaire may influence the descriptive findings.

Depending on the type and size of sample, the findings may not be generalizable or produce an accurate description of the population of interest.

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

- What is descriptive research?

Last updated

5 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Descriptive research is a common investigatory model used by researchers in various fields, including social sciences, linguistics, and academia.

Read on to understand the characteristics of descriptive research and explore its underlying techniques, processes, and procedures.

Analyze your descriptive research

Dovetail streamlines analysis to help you uncover and share actionable insights

Descriptive research is an exploratory research method. It enables researchers to precisely and methodically describe a population, circumstance, or phenomenon.

As the name suggests, descriptive research describes the characteristics of the group, situation, or phenomenon being studied without manipulating variables or testing hypotheses . This can be reported using surveys , observational studies, and case studies. You can use both quantitative and qualitative methods to compile the data.

Besides making observations and then comparing and analyzing them, descriptive studies often develop knowledge concepts and provide solutions to critical issues. It always aims to answer how the event occurred, when it occurred, where it occurred, and what the problem or phenomenon is.

- Characteristics of descriptive research

The following are some of the characteristics of descriptive research:

Quantitativeness

Descriptive research can be quantitative as it gathers quantifiable data to statistically analyze a population sample. These numbers can show patterns, connections, and trends over time and can be discovered using surveys, polls, and experiments.

Qualitativeness

Descriptive research can also be qualitative. It gives meaning and context to the numbers supplied by quantitative descriptive research .

Researchers can use tools like interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic studies to illustrate why things are what they are and help characterize the research problem. This is because it’s more explanatory than exploratory or experimental research.

Uncontrolled variables

Descriptive research differs from experimental research in that researchers cannot manipulate the variables. They are recognized, scrutinized, and quantified instead. This is one of its most prominent features.

Cross-sectional studies

Descriptive research is a cross-sectional study because it examines several areas of the same group. It involves obtaining data on multiple variables at the personal level during a certain period. It’s helpful when trying to understand a larger community’s habits or preferences.

Carried out in a natural environment

Descriptive studies are usually carried out in the participants’ everyday environment, which allows researchers to avoid influencing responders by collecting data in a natural setting. You can use online surveys or survey questions to collect data or observe.

Basis for further research

You can further dissect descriptive research’s outcomes and use them for different types of investigation. The outcomes also serve as a foundation for subsequent investigations and can guide future studies. For example, you can use the data obtained in descriptive research to help determine future research designs.

- Descriptive research methods

There are three basic approaches for gathering data in descriptive research: observational, case study, and survey.

You can use surveys to gather data in descriptive research. This involves gathering information from many people using a questionnaire and interview .

Surveys remain the dominant research tool for descriptive research design. Researchers can conduct various investigations and collect multiple types of data (quantitative and qualitative) using surveys with diverse designs.

You can conduct surveys over the phone, online, or in person. Your survey might be a brief interview or conversation with a set of prepared questions intended to obtain quick information from the primary source.

Observation

This descriptive research method involves observing and gathering data on a population or phenomena without manipulating variables. It is employed in psychology, market research , and other social science studies to track and understand human behavior.

Observation is an essential component of descriptive research. It entails gathering data and analyzing it to see whether there is a relationship between the two variables in the study. This strategy usually allows for both qualitative and quantitative data analysis.

Case studies

A case study can outline a specific topic’s traits. The topic might be a person, group, event, or organization.

It involves using a subset of a larger group as a sample to characterize the features of that larger group.

You can generalize knowledge gained from studying a case study to benefit a broader audience.

This approach entails carefully examining a particular group, person, or event over time. You can learn something new about the study topic by using a small group to better understand the dynamics of the entire group.

- Types of descriptive research

There are several types of descriptive study. The most well-known include cross-sectional studies, census surveys, sample surveys, case reports, and comparison studies.

Case reports and case series

In the healthcare and medical fields, a case report is used to explain a patient’s circumstances when suffering from an uncommon illness or displaying certain symptoms. Case reports and case series are both collections of related cases. They have aided the advancement of medical knowledge on countless occasions.

The normative component is an addition to the descriptive survey. In the descriptive–normative survey, you compare the study’s results to the norm.

Descriptive survey

This descriptive type of research employs surveys to collect information on various topics. This data aims to determine the degree to which certain conditions may be attained.

You can extrapolate or generalize the information you obtain from sample surveys to the larger group being researched.

Correlative survey

Correlative surveys help establish if there is a positive, negative, or neutral connection between two variables.

Performing census surveys involves gathering relevant data on several aspects of a given population. These units include individuals, families, organizations, objects, characteristics, and properties.

During descriptive research, you gather different degrees of interest over time from a specific population. Cross-sectional studies provide a glimpse of a phenomenon’s prevalence and features in a population. There are no ethical challenges with them and they are quite simple and inexpensive to carry out.

Comparative studies

These surveys compare the two subjects’ conditions or characteristics. The subjects may include research variables, organizations, plans, and people.

Comparison points, assumption of similarities, and criteria of comparison are three important variables that affect how well and accurately comparative studies are conducted.

For instance, descriptive research can help determine how many CEOs hold a bachelor’s degree and what proportion of low-income households receive government help.

- Pros and cons

The primary advantage of descriptive research designs is that researchers can create a reliable and beneficial database for additional study. To conduct any inquiry, you need access to reliable information sources that can give you a firm understanding of a situation.

Quantitative studies are time- and resource-intensive, so knowing the hypotheses viable for testing is crucial. The basic overview of descriptive research provides helpful hints as to which variables are worth quantitatively examining. This is why it’s employed as a precursor to quantitative research designs.

Some experts view this research as untrustworthy and unscientific. However, there is no way to assess the findings because you don’t manipulate any variables statistically.

Cause-and-effect correlations also can’t be established through descriptive investigations. Additionally, observational study findings cannot be replicated, which prevents a review of the findings and their replication.

The absence of statistical and in-depth analysis and the rather superficial character of the investigative procedure are drawbacks of this research approach.

- Descriptive research examples and applications

Several descriptive research examples are emphasized based on their types, purposes, and applications. Research questions often begin with “What is …” These studies help find solutions to practical issues in social science, physical science, and education.

Here are some examples and applications of descriptive research:

Determining consumer perception and behavior

Organizations use descriptive research designs to determine how various demographic groups react to a certain product or service.

For example, a business looking to sell to its target market should research the market’s behavior first. When researching human behavior in response to a cause or event, the researcher pays attention to the traits, actions, and responses before drawing a conclusion.

Scientific classification

Scientific descriptive research enables the classification of organisms and their traits and constituents.

Measuring data trends

A descriptive study design’s statistical capabilities allow researchers to track data trends over time. It’s frequently used to determine the study target’s current circumstances and underlying patterns.

Conduct comparison

Organizations can use a descriptive research approach to learn how various demographics react to a certain product or service. For example, you can study how the target market responds to a competitor’s product and use that information to infer their behavior.

- Bottom line

A descriptive research design is suitable for exploring certain topics and serving as a prelude to larger quantitative investigations. It provides a comprehensive understanding of the “what” of the group or thing you’re investigating.

This research type acts as the cornerstone of other research methodologies . It is distinctive because it can use quantitative and qualitative research approaches at the same time.

What is descriptive research design?

Descriptive research design aims to systematically obtain information to describe a phenomenon, situation, or population. More specifically, it helps answer the what, when, where, and how questions regarding the research problem rather than the why.

How does descriptive research compare to qualitative research?

Despite certain parallels, descriptive research concentrates on describing phenomena, while qualitative research aims to understand people better.

How do you analyze descriptive research data?

Data analysis involves using various methodologies, enabling the researcher to evaluate and provide results regarding validity and reliability.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 30 September 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Descriptive Research? Definition, Methods, Types and Examples

Descriptive research is a methodological approach that seeks to depict the characteristics of a phenomenon or subject under investigation. In scientific inquiry, it serves as a foundational tool for researchers aiming to observe, record, and analyze the intricate details of a particular topic. This method provides a rich and detailed account that aids in understanding, categorizing, and interpreting the subject matter.

Descriptive research design is widely employed across diverse fields, and its primary objective is to systematically observe and document all variables and conditions influencing the phenomenon.

After this descriptive research definition, let’s look at this example. Consider a researcher working on climate change adaptation, who wants to understand water management trends in an arid village in a specific study area. She must conduct a demographic survey of the region, gather population data, and then conduct descriptive research on this demographic segment. The study will then uncover details on “what are the water management practices and trends in village X.” Note, however, that it will not cover any investigative information about “why” the patterns exist.

Table of Contents

What is descriptive research?

If you’ve been wondering “What is descriptive research,” we’ve got you covered in this post! In a nutshell, descriptive research is an exploratory research method that helps a researcher describe a population, circumstance, or phenomenon. It can help answer what , where , when and how questions, but not why questions. In other words, it does not involve changing the study variables and does not seek to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Importance of descriptive research

Now, let’s delve into the importance of descriptive research. This research method acts as the cornerstone for various academic and applied disciplines. Its primary significance lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive overview of a phenomenon, enabling researchers to gain a nuanced understanding of the variables at play. This method aids in forming hypotheses, generating insights, and laying the groundwork for further in-depth investigations. The following points further illustrate its importance:

Provides insights into a population or phenomenon: Descriptive research furnishes a comprehensive overview of the characteristics and behaviors of a specific population or phenomenon, thereby guiding and shaping the research project.

Offers baseline data: The data acquired through this type of research acts as a reference for subsequent investigations, laying the groundwork for further studies.

Allows validation of sampling methods: Descriptive research validates sampling methods, aiding in the selection of the most effective approach for the study.

Helps reduce time and costs: It is cost-effective and time-efficient, making this an economical means of gathering information about a specific population or phenomenon.

Ensures replicability: Descriptive research is easily replicable, ensuring a reliable way to collect and compare information from various sources.

When to use descriptive research design?

Determining when to use descriptive research depends on the nature of the research question. Before diving into the reasons behind an occurrence, understanding the how, when, and where aspects is essential. Descriptive research design is a suitable option when the research objective is to discern characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories without manipulating variables. It is therefore often employed in the initial stages of a study before progressing to more complex research designs. To put it in another way, descriptive research precedes the hypotheses of explanatory research. It is particularly valuable when there is limited existing knowledge about the subject.

Some examples are as follows, highlighting that these questions would arise before a clear outline of the research plan is established:

- In the last two decades, what changes have occurred in patterns of urban gardening in Mumbai?

- What are the differences in climate change perceptions of farmers in coastal versus inland villages in the Philippines?

Characteristics of descriptive research

Coming to the characteristics of descriptive research, this approach is characterized by its focus on observing and documenting the features of a subject. Specific characteristics are as below.

- Quantitative nature: Some descriptive research types involve quantitative research methods to gather quantifiable information for statistical analysis of the population sample.

- Qualitative nature: Some descriptive research examples include those using the qualitative research method to describe or explain the research problem.

- Observational nature: This approach is non-invasive and observational because the study variables remain untouched. Researchers merely observe and report, without introducing interventions that could impact the subject(s).

- Cross-sectional nature: In descriptive research, different sections belonging to the same group are studied, providing a “snapshot” of sorts.

- Springboard for further research: The data collected are further studied and analyzed using different research techniques. This approach helps guide the suitable research methods to be employed.

Types of descriptive research

There are various descriptive research types, each suited to different research objectives. Take a look at the different types below.

- Surveys: This involves collecting data through questionnaires or interviews to gather qualitative and quantitative data.

- Observational studies: This involves observing and collecting data on a particular population or phenomenon without influencing the study variables or manipulating the conditions. These may be further divided into cohort studies, case studies, and cross-sectional studies:

- Cohort studies: Also known as longitudinal studies, these studies involve the collection of data over an extended period, allowing researchers to track changes and trends.

- Case studies: These deal with a single individual, group, or event, which might be rare or unusual.

- Cross-sectional studies : A researcher collects data at a single point in time, in order to obtain a snapshot of a specific moment.

- Focus groups: In this approach, a small group of people are brought together to discuss a topic. The researcher moderates and records the group discussion. This can also be considered a “participatory” observational method.

- Descriptive classification: Relevant to the biological sciences, this type of approach may be used to classify living organisms.

Descriptive research methods

Several descriptive research methods can be employed, and these are more or less similar to the types of approaches mentioned above.

- Surveys: This method involves the collection of data through questionnaires or interviews. Surveys may be done online or offline, and the target subjects might be hyper-local, regional, or global.

- Observational studies: These entail the direct observation of subjects in their natural environment. These include case studies, dealing with a single case or individual, as well as cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, for a glimpse into a population or changes in trends over time, respectively. Participatory observational studies such as focus group discussions may also fall under this method.

Researchers must carefully consider descriptive research methods, types, and examples to harness their full potential in contributing to scientific knowledge.

Examples of descriptive research

Now, let’s consider some descriptive research examples.

- In social sciences, an example could be a study analyzing the demographics of a specific community to understand its socio-economic characteristics.

- In business, a market research survey aiming to describe consumer preferences would be a descriptive study.

- In ecology, a researcher might undertake a survey of all the types of monocots naturally occurring in a region and classify them up to species level.

These examples showcase the versatility of descriptive research across diverse fields.

Advantages of descriptive research

There are several advantages to this approach, which every researcher must be aware of. These are as follows:

- Owing to the numerous descriptive research methods and types, primary data can be obtained in diverse ways and be used for developing a research hypothesis .

- It is a versatile research method and allows flexibility.

- Detailed and comprehensive information can be obtained because the data collected can be qualitative or quantitative.

- It is carried out in the natural environment, which greatly minimizes certain types of bias and ethical concerns.

- It is an inexpensive and efficient approach, even with large sample sizes

Disadvantages of descriptive research

On the other hand, this design has some drawbacks as well:

- It is limited in its scope as it does not determine cause-and-effect relationships.

- The approach does not generate new information and simply depends on existing data.

- Study variables are not manipulated or controlled, and this limits the conclusions to be drawn.

- Descriptive research findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

- Finally, it offers a preliminary understanding rather than an in-depth understanding.

To reiterate, the advantages of descriptive research lie in its ability to provide a comprehensive overview, aid hypothesis generation, and serve as a preliminary step in the research process. However, its limitations include a potential lack of depth, inability to establish cause-and-effect relationships, and susceptibility to bias.

Frequently asked questions

When should researchers conduct descriptive research.

Descriptive research is most appropriate when researchers aim to portray and understand the characteristics of a phenomenon without manipulating variables. It is particularly valuable in the early stages of a study.

What is the difference between descriptive and exploratory research?

Descriptive research focuses on providing a detailed depiction of a phenomenon, while exploratory research aims to explore and generate insights into an issue where little is known.

What is the difference between descriptive and experimental research?

Descriptive research observes and documents without manipulating variables, whereas experimental research involves intentional interventions to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Is descriptive research only for social sciences?

No, various descriptive research types may be applicable to all fields of study, including social science, humanities, physical science, and biological science.

How important is descriptive research?

The importance of descriptive research lies in its ability to provide a glimpse of the current state of a phenomenon, offering valuable insights and establishing a basic understanding. Further, the advantages of descriptive research include its capacity to offer a straightforward depiction of a situation or phenomenon, facilitate the identification of patterns or trends, and serve as a useful starting point for more in-depth investigations. Additionally, descriptive research can contribute to the development of hypotheses and guide the formulation of research questions for subsequent studies.

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

Conference Paper vs. Journal Paper: What’s the Difference

What is Availability Heuristic (with Examples)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review

MSN, CRNP, Doctoral Candidate, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Justine S. Sefcik

MS, RN, Doctoral Candidate, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Christine Bradway

PhD, CRNP, FAAN, Associate Professor of Gerontological Nursing, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Qualitative description (QD) is a term that is widely used to describe qualitative studies of health care and nursing-related phenomena. However, limited discussions regarding QD are found in the existing literature. In this systematic review, we identified characteristics of methods and findings reported in research articles published in 2014 whose authors identified the work as QD. After searching and screening, data were extracted from the sample of 55 QD articles and examined to characterize research objectives, design justification, theoretical/philosophical frameworks, sampling and sample size, data collection and sources, data analysis, and presentation of findings. In this review, three primary findings were identified. First, despite inconsistencies, most articles included characteristics consistent with limited, available QD definitions and descriptions. Next, flexibility or variability of methods was common and desirable for obtaining rich data and achieving understanding of a phenomenon. Finally, justification for how a QD approach was chosen and why it would be an appropriate fit for a particular study was limited in the sample and, therefore, in need of increased attention. Based on these findings, recommendations include encouragement to researchers to provide as many details as possible regarding the methods of their QD study so that readers can determine whether the methods used were reasonable and effective in producing useful findings.

Qualitative description (QD) is a label used in qualitative research for studies which are descriptive in nature, particularly for examining health care and nursing-related phenomena ( Polit & Beck, 2009 , 2014 ). QD is a widely cited research tradition and has been identified as important and appropriate for research questions focused on discovering the who, what, and where of events or experiences and gaining insights from informants regarding a poorly understood phenomenon. It is also the label of choice when a straight description of a phenomenon is desired or information is sought to develop and refine questionnaires or interventions ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2005 ).

Despite many strengths and frequent citations of its use, limited discussions regarding QD are found in qualitative research textbooks and publications. To the best of our knowledge, only seven articles include specific guidance on how to design, implement, analyze, or report the results of a QD study ( Milne & Oberle, 2005 ; Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen, & Sondergaard, 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 , 2010 ; Sullivan-Bolyai, Bova, & Harper, 2005 ; Vaismoradi, Turunen, & Bondas, 2013 ; Willis, Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, & Zichi-Cohen, 2016 ). Furthermore, little is known about characteristics of QD as reported in journal-published, nursing-related, qualitative studies. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to describe specific characteristics of methods and findings of studies reported in journal articles (published in 2014) self-labeled as QD. In this review, we did not have a goal to judge whether QD was done correctly but rather to report on the features of the methods and findings.

Features of QD

Several QD design features and techniques have been described in the literature. First, researchers generally draw from a naturalistic perspective and examine a phenomenon in its natural state ( Sandelowski, 2000 ). Second, QD has been described as less theoretical compared to other qualitative approaches ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ), facilitating flexibility in commitment to a theory or framework when designing and conducting a study ( Sandelowski, 2000 , 2010 ). For example, researchers may or may not decide to begin with a theory of the targeted phenomenon and do not need to stay committed to a theory or framework if their investigations take them down another path ( Sandelowski, 2010 ). Third, data collection strategies typically involve individual and/or focus group interviews with minimal to semi-structured interview guides ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 ). Fourth, researchers commonly employ purposeful sampling techniques such as maximum variation sampling which has been described as being useful for obtaining broad insights and rich information ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 ). Fifth, content analysis (and in many cases, supplemented by descriptive quantitative data to describe the study sample) is considered a primary strategy for data analysis ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 ). In some instances thematic analysis may also be used to analyze data; however, experts suggest care should be taken that this type of analysis is not confused with content analysis ( Vaismoradi et al., 2013 ). These data analysis approaches allow researchers to stay close to the data and as such, interpretation is of low-inference ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ), meaning that different researchers will agree more readily on the same findings even if they do not choose to present the findings in the same way ( Sandelowski, 2000 ). Finally, representation of study findings in published reports is expected to be straightforward, including comprehensive descriptive summaries and accurate details of the data collected, and presented in a way that makes sense to the reader ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 ).

It is also important to acknowledge that variations in methods or techniques may be appropriate across QD studies ( Sandelowski, 2010 ). For example, when consistent with the study goals, decisions may be made to use techniques from other qualitative traditions, such as employing a constant comparative analytic approach typically associated with grounded theory ( Sandelowski, 2000 ).

Search Strategy and Study Screening

The PubMed electronic database was searched for articles written in English and published from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014, using the terms, “qualitative descriptive study,” “qualitative descriptive design,” and “qualitative description,” combined with “nursing.” This specific publication year, “2014,” was chosen because it was the most recent full year at the time of beginning this systematic review. As we did not intend to identify trends in QD approaches over time, it seemed reasonable to focus on the nursing QD studies published in a certain year. The inclusion criterion for this review was data-based, nursing-related, research articles in which authors used the terms QD, qualitative descriptive study, or qualitative descriptive design in their titles or abstracts as well as in the main texts of the publication.

All articles yielded through an initial search in PubMed were exported into EndNote X7 ( Thomson Reuters, 2014 ), a reference management software, and duplicates were removed. Next, titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine if the publication met inclusion criteria; all articles meeting inclusion criteria were then read independently in full by two authors (HK and JS) to determine if the terms – QD or qualitative descriptive study/design – were clearly stated in the main texts. Any articles in which researchers did not specifically state these key terms in the main text were then excluded, even if the terms had been used in the study title or abstract. In one article, for example, although “qualitative descriptive study” was reported in the published abstract, the researchers reported a “qualitative exploratory design” in the main text of the article ( Sundqvist & Carlsson, 2014 ); therefore, this article was excluded from our review. Despite the possibility that there may be other QD studies published in 2014 that were not labeled as such, to facilitate our screening process we only included articles where the researchers clearly used our search terms for their approach. Finally, the two authors compared, discussed, and reconciled their lists of articles with a third author (CB).

Study Selection

Initially, although the year 2014 was specifically requested, 95 articles were identified (due to ahead of print/Epub) and exported into the EndNote program. Three duplicate publications were removed and the 20 articles with final publication dates of 2015 were also excluded. The remaining 72 articles were then screened by examining titles, abstracts, and full-texts. Based on our inclusion criteria, 15 (of 72) were then excluded because QD or QD design/study was not identified in the main text. We then re-examined the remaining 57 articles and excluded two additional articles that did not meet inclusion criteria (e.g., QD was only reported as an analytic approach in the data analysis section). The remaining 55 publications met inclusion criteria and comprised the sample for our systematic review (see Figure 1 ).

Flow Diagram of Study Selection

Of the 55 publications, 23 originated from North America (17 in the United States; 6 in Canada), 12 from Asia, 11 from Europe, 7 from Australia and New Zealand, and 2 from South America. Eleven studies were part of larger research projects and two of them were reported as part of larger mixed-methods studies. Four were described as a secondary analysis.

Quality Appraisal Process

Following the identification of the 55 publications, two authors (HK and JS) independently examined each article using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist ( CASP, 2013 ). The CASP was chosen to determine the general adequacy (or rigor) of the qualitative studies included in this review as the CASP criteria are generic and intend to be applied to qualitative studies in general. In addition, the CASP was useful because we were able to examine the internal consistency between study aims and methods and between study aims and findings as well as the usefulness of findings ( CASP, 2013 ). The CASP consists of 10 main questions with several sub-questions to consider when making a decision about the main question ( CASP, 2013 ). The first two questions have reviewers examine the clarity of study aims and appropriateness of using qualitative research to achieve the aims. With the next eight questions, reviewers assess study design, sampling, data collection, and analysis as well as the clarity of the study’s results statement and the value of the research. We used the seven questions and 17 sub-questions related to methods and statement of findings to evaluate the articles. The results of this process are presented in Table 1 .

CASP Questions and Quality Appraisal Results (N = 55)

| CASP Questions • CASP Subquestions | Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can’t tell | ||||

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher justify the research design? | 26 | 47.3 | 28 | 50.9 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher explain how the participants were selected? | 44 | 80 | 6 | 10.9 | 5 | 9.1 |

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | ||||||

| • Was the setting for data collection justified? | 31 | 56.4 | 21 | 38.2 | 3 | 5.4 |

| • Was it clear how data were collected e.g., focus group, semistructured interview etc.? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Did the researcher justify the methods chosen? | 13 | 23.6 | 41 | 74.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher make the methods explicit e.g., for the interview method, was there an indication of how interviews were conducted, or did they use a topic guide? | 51 | 92.7 | 4 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Was the form of data clear e.g., tape recordings, video materials, notes, etc.? | 54 | 98.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher discuss saturation of data? | 20 | 36.4 | 35 | 63.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher critically examine their own role, potential bias, and influence during data collection, including sample recruitment and choice of location | 4 | 7.3 | 50 | 90.9 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | ||||||

| • Was there sufficient detail about how the research was explained to participants for the reader to assess whether ethical standards were maintained? | 49 | 89.1 | 4 | 7.3 | 2 | 3.6 |

| • Was approval sought from an ethics committee? | 51 | 92.7 | 4 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | ||||||

| • Was there an in-depth description of the analysis process? | 46 | 83.6 | 9 | 16.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Was thematic or content analysis used. If so, was it clear how the categories/themes derived from the data? | 51 | 92.7 | 3 | 5.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher critically examine their own role, potential bias and influence during analysis and selection of data for presentation? | 20 | 36.4 | 30 | 54.5 | 5 | 9.1 |

| Was there a clear statement of findings? | ||||||

| • Were the findings explicit? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| • Did the researcher discuss the credibility of their findings (e.g., triangulation) | 46 | 83.6 | 8 | 14.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Were the findings discussed in relation to the original research question? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note . The CASP questions are adapted from “10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research,” by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2013, retrieved from http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf . Its license can be found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

Once articles were assessed by the two authors independently, all three authors discussed and reconciled our assessment. No articles were excluded based on CASP results; rather, results were used to depict the general adequacy (or rigor) of all 55 articles meeting inclusion criteria for our systematic review. In addition, the CASP was included to enhance our examination of the relationship between the methods and the usefulness of the findings documented in each of the QD articles included in this review.

Process for Data Extraction and Analysis

To further assess each of the 55 articles, data were extracted on: (a) research objectives, (b) design justification, (c) theoretical or philosophical framework, (d) sampling and sample size, (e) data collection and data sources, (f) data analysis, and (g) presentation of findings (see Table 2 ). We discussed extracted data and identified common and unique features in the articles included in our systematic review. Findings are described in detail below and in Table 3 .

Elements for Data Extraction

| Elements | Data Extraction |

|---|---|

| Research objectives | • Verbs used in objectives or aims |

| • Focuses of study | |

| Design justification | • If the article cited references for qualitative description |

| • If the article offered rationale to choose qualitative description | |

| • References cited | |

| • Rationale reported | |

| Theoretical or philosophical frameworks | • If the article has theoretical or philosophical frameworks for study |

| • Theoretical or philosophical frameworks reported | |

| • How the frameworks were used in data collection and analysis | |

| Sampling and sample sizes | • Sampling strategies (e.g., purposeful sampling, maximum variation) |

| • Sample size | |

| Data collection and sources | • Data collection techniques (e.g., individual or focus-group interviews, interview guide, surveys, field notes) |

| Data analysis | • Data analysis techniques (e.g., qualitative content analysis, thematic analysis, constant comparison) |

| • If data saturation was achieved | |

| Presentation of findings | • Statement of findings |

| • Consistency with research objectives |

Data Extraction and Analysis Results

| Authors Country | Research Objectives | Design justification | Theoretical/ philosophical frameworks | Sampling/ sample size | Data collection and data sources | Data analysis | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • USA | • Explore • Responses to communication strategies | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | Not reported (NR) | • Purposive sampling/ maximum variation • 32 family members | • Interviews • Observations • Review of daily flow sheet • Demographics | • Inductive and deductive qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Five themes about family members’ perceptions of nursing communication approaches |

| • Sweden | • Describe • Experiences of using guidelines in daily practice | • (-) Reference • (+) Rationale • Part of a research program | NR | • Unspecified • 8 care providers | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | One theme and seven subthemes about care providers’ experiences of using guidelines in daily practice |

| • USA | • Examine • Culturally specific views of processes and causes of midlife weight gain | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | Health belief model and Kleiman’s explanatory model | • Unspecified • 19 adults | • Semistructured, individual interview | • Conventional content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Three main categories (from the model) and eight subthemes about causes of weight gain in midlife |

| • Iran | • Explore • Factors initiating responsibility among medical trainees | • (-) Reference • (+) Rationale | NR | • Convenience, snowball, and maximum variation sampling • 15 trainees and other professionals | • Semistructured, individual interview • Interview guide | • Conventional content analysis • Constant comparison • (+) Data saturation | Two themes and individual and non- individual-based factors per theme |

| • Iran | • Explore • Factors related to job satisfaction and dissatisfaction | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Convenience sampling • 85 nurses | • Semistructured focus group interviews • Interview guide | • Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation | Three main themes and associated factors regarding job satisfaction and dissatisfaction |

| • Norway | • Describe • Perceptions on simulation-based team training | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Strategic sampling • 18 registered nurses | • Semistructured individual interviews | • Inductive content analysis • (-) Data saturation | One main category, three categories, and six sub- categories regarding nurses’ perceptions on simulation-based team training |

| • USA | • Determine • Barriers and supports for attending college and nursing school | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Unspecified • 45 students | • Focus-group interviews • Using Photovoice and SHOWeD | • Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation | Five themes about facilitators and barriers |

| • USA | • Explore • Reasons for choosing home birth and birth experiences | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 20 women | • Semistructured focus-group interviews • Interview guide • Field notes | • Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Five common themes and concepts about reasons for choosing home birth based on their birth experiences |

| • New Zealand | • Explore • Normal fetal activity related to hunger and satiation | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • Denzin & Lincoln (2011) | NR | • Purposive sampling • 19 pregnant women | • Semistructured individual interviews • Open-ended questions | • Inductive qualitative content analysis • Descriptive statistical analysis • (+) Data saturation | Four patterns regarding fetal activities in relation to meal anticipation, maternal hunger, maternal meal consummation, and maternal satiety |

| • Italy | • Explore, describe, and compare • perceptions of nursing caring | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | NR | • Purposive sampling • 20 nurses and 20 patients | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide • Field notes during interviews | • Unspecified various analytic strategies including constant comparison • (-) Data saturation | Nursing caring from both patients’ and nurses’ perspectives – a summary of data in visible caring and invisible caring |

| • Hong Kong | • Address • How to reduce coronary heart disease risks | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Secondary analysis • • | NR | • Convenience and snowball sampling • 105 patients | • Focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Four categories about patients’ abilities to reduce coronary heart disease |

| • Taiwan | • Explore • Reasons for young–old people not killing themselves | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Convenience sampling • 31 older adults | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide • Observation with memos/reflective journal | • Content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Six themes regarding reasons for not committing to suicide |

| • USA | • Explore • Neonatal intensive care unit experiences | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | NR | • Purposive sampling and convenience sample • 15 mothers | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide | • Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Four themes about participants’ experiences of neonatal intensive care unit |

| • Colombia | • Investigate • Barriers/facilitators to implementing evidence-based nursing | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | Ottawa model for research use: knowledge translation framework | • Convenience sampling • 13 nursing professionals | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide | • Inductive qualitative content analysis • Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation | Four main barriers and potential facilitators to evidence-based nursing |

| • Australia | • Explore • Perceptions and utilization of diaries | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | NR | • Unspecified • 19 patients and families | • Responses to open-ended questions on survey | • Unspecified analysis strategy • (-) Data saturation | Five themes regarding perceptions on use of diaries and descriptive statistics using frequencies of utilization |

| • USA | • Explore • Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about sexual consent | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger mixed-method study | Theory of planned behavior | • Purposive sampling • snowball sampling • 26 women | • Semistructured focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Three main categories and subthemes regarding sexual consent |

| • Sweden | • Describe • Experiences of knowledge development in wound management | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale: weak • | NR | • Purposive sampling • 16 district nurses | • Individual interviews • Interview guide | • Qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Three categories and eleven sub-categories about knowledge development experiences in wound management |

| • USA | • Describe • Parental-pain journey, beliefs about pain, and attitudes/behaviors related to children’s responses | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • • Part of a larger mixed methods study | NR | • Purposive sampling • 9 parents | • Individual interviews • One open- ended question | • Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Two main themes, categories, and subcategories about parents’ experiences of observing children’s pain |

| • USA | • Describe • Challenges and barriers in providing culturally competent care | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • Secondary analysis | NR | • Stratified sampling • 253 nurses | • Written responses to 2 open-ended questions on survey | • Thematic analysis • (-) Data saturation | Three themes regarding challenges/barriers |

| • Denmark | • Describe • Experiences of childbirth | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • A substudy | NR | • Purposive sampling with maximum variation • Partners of 10 women | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation | Three themes and four subthemes about partners’ experiences of women’s childbirth |

| • Australia | • Explore • Perceptions about medical nutrition and hydration at the end of life | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 10 nurses | • Focus-group interviews | • “analyzed thematically” • (-) Data saturation | One main theme and four subthemes regarding nurses’ perceptions on EOL- related medical nutrition and hydration |

| • USA | • Describe • Reasons for leaving a home visiting program early | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Convenience sample • 32 mothers, nurses, and nurse supervisors | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Inductive content analysis • Constant comparison approach • (+) Data saturation | Three sets of reasons for leaving a home visiting program |

| • Sweden | • Explore and describe • Beliefs and attitudes around the decision for a caesarean section | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • | NR | • Unspecified • 21 males | • Individual telephone interviews | • Thematic analysis • Constant comparison approach • (-) Data saturation | Two themes and subthemes in relation to the research objective |

| • Taiwan | • Explore • Illness experiences of early onset of knee osteoarthritis | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • • Part of a large research series | NR | • Purposive sampling • 17 adults | • Semistructured, Individual interviews • Interview guide • Memo/field notes (observations) | • Inductive content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Three major themes and nine subthemes regarding experiences of early onset-knee osteoarthritis |

| • Australia | • Explore • Perceptions about bedside handover (new model) by nurses | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • | NR | • Purposive sampling • 30 patients | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Thematic content analysis • (-) Data analysis | Two dominant themes and related subthemes regarding patients’ thoughts about nurses’ bedside handover |

| • Sweden | • Identify • Patterns in learning when living with diabetes | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Purposive sampling with variations in age and sex • 13 participants | • Semistructured, individual interviews (3 times over 3 years) | • analysis process • Inductive qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Five main patterns of learning when living with diabetes for three years following diagnosis |

| • Canada | • Evaluate • Book chat intervention based on a novel | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger research project | NR | • Unspecified • 11 long-term- care staff | • Questionnaire with two open- ended questions | • Thematic content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Five themes (positive comments) about the book chat with brief description |

| • Taiwan | • Explore • Facilitators and barriers to implementing smoking- cessation counseling services | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Unspecified • 16 nurse- counselors | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide | • Inductive content analysis • Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation | Two themes and eight subthemes about facilitators and barriers described using 2-4 quotations per subtheme |

| • USA | • Identify • Educational strategies to manage disruptive behavior | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger study | NR | • Unspecified • 9 nurses | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Content analysis procedures • (-) Data saturation | Two main themes regarding education strategies for nurse educators |

| • USA | • Explore • Experiences of difficulty resolving patient- related concerns | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Secondary analysis | NR | • Unspecified • 1932 physician, nursing, and midwifery professionals | • E-mail survey with multiple- choice and free- text responses | • Inductive thematic analysis • Descriptive statistics • (-) Data saturation | One overarching theme and four subthemes about professionals’ experiences of difficulty resolving patient-related concerns |

| • Singapore | • Explicate • Experience of quality of life for older adults | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | Parse’s human becoming paradigm | • Unspecified • 10 elderly residents | • Individual interviews • Interview questions presented (Parse) | • Unspecified analysis techniques • (-) Data saturation | Three themes presented using both participants’ language and the researcher’s language |