Introductory Essay: Slavery and the Struggle for Abolition from the Colonial Period to the Civil War

How did the principles of the Declaration of Independence contribute to the quest to end slavery from colonial times to the outbreak of the Civil War?

- I can explain how slavery became codifed over time in the United States.

- I can explain how Founding principles in the Declaration of Independence strengthened anti-slavery thought and action.

- I can explain how territorial expansion intensified the national debate over slavery.

- I can explain various ways in which African Americans secured their own liberty from the colonial era to the Civil War.

- I can explain how African American leaders worked for the cause of abolition and equality.

Essential Vocabulary

Slavery and the struggle for abolition from the colonial period to the civil war.

The English established their first permanent settler colony in a place they called Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. Early seventeenth-century Virginia was abundant in land and scarce in laborers. Initially, the labor need was met mostly by propertyless English men and women who came to the new world as indentured servants hoping to become landowners themselves after their term of service ended. Such servitude was generally the status, too, of Africans in early British America, the first of whom were brought to Virginia by a Dutch vessel in 1619. But within a few decades, indentured servitude in the colonies gave way to lifelong, hereditary slavery, imposed exclusively on black Africans.

Because forced labor (whether indentured servitude or slavery) was a longstanding and common condition, the injustice of slavery troubled relatively few settlers during the colonial period. Southern colonies in particular codified slavery into law. Slavery became hereditary, with men, women, and children bought and sold as property, a condition known as chattel slavery . Opposition to slavery was mainly concentrated among Quakers , who believed in the equality of all men and women and therefore opposed slavery on moral grounds. Quaker opposition to slavery was seen as early as 1688, when a group of Quakers submitted a formal protest against the institution for discussion at a local meeting.

Anti-slavery sentiment strengthened during the era of the Revolution and Founding. Founding principles, based on natural law proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and in several state constitutions, added philosophical force to biblically grounded ideas of human equality and dignity. Those principles informed free and enslaved blacks, including Prince Hall, Elizabeth Freeman, Quock Walker, and Belinda Sutton, who sent anti slavery petitions to state legislatures. Their powerful appeal to natural rights moved legislators and judges to implement the first wave of emancipation in the United States. Immediate emancipation in Massachusetts, gradual emancipation in other northern states, and private manumission in the upper South dealt blows against slavery and freed tens of thousands of people.

Slavery remained deeply entrenched and thousands remained enslaved, however, in states in both the upper and lower South , even as northern leaders believed the practice was on its way to extinction. The result was the set of compromises the Framers inscribed into the U.S. Constitution—lending slavery important protections but also preparing for its eventual abolition. The Constitution did not use the word “slave” or “slavery,” instead referring to those enslaved as “persons.” James Madison, the “father” of the Constitution, thus thought the document implicitly denied the legitimacy of a claim of property in another human being. The Constitution also restricted slavery’s growth by allowing Congress to ban the slave trade after 20 years. Out of those compromises grew extended controversies, however, the most heated and dangerous of which concerned the treatment of fugitive slaves and the status of slavery in federal territories.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 renewed and enhanced slavery’s profitability and expansion, which intensified both attachment and opposition to it. The first major flare-up occurred in 1819, when a dispute over whether Missouri would be admitted to the Union as a slave state or a free state generated threats of civil war among members of Congress. The adoption of the Missouri Compromise in 1820 quelled the anger for a time. But the dispute was reignited in the 1830s and continued to inflame the country’s political life through the Civil War.

A cotton gin on display at the Eli Whitney Museum by Tom Murphy VII, 2007.

“U.S. Cotton Production 1790–1834” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr, CC BY 4.0

Separating the sticky seeds from cotton fiber was slow, painstaking work. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin (gin being southern slang for engine) made the task much simpler, and cotton production in the lower South exploded. Cotton planters and their slaves moved to Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama to start new cotton plantations. Many planters in the Chesapeake region sold their slaves to cotton planters in the lower South. This created a massive interstate slave trade that transferred enslaved persons through auctions and forced marches in chains and that also broke up many slave families.

In 1831, in Virginia, a large-scale slave rebellion led by Nat Turner resulted in the deaths of approximately 60 whites and more than 100 blacks and generated alarm throughout the South. That same decade saw the emergence of a radicalized (and to a degree racially integrated) abolitionist movement, led by Massachusetts activist William Lloyd Garrison, and an equally radicalized pro slavery faction, led by U.S. Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

The polarization sharpened in subsequent decades. The Mexican-American War (1846–1848) brought large new western territories under U.S. control and renewed the contention in Congress over the status of slavery in federal territories. The complex 1850 Compromise, which included a new fugitive slave law heavily weighted in favor of slaveholders’ interests, did little to restore calm.

A few years later, Congress reopened the Kansas and Nebraska territories to slavery, thereby undoing the 1820 Missouri Compromise and rendering any further compromises unlikely. The U.S. Supreme Court tried vainly to settle the controversy by issuing, in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), the most pro-slavery ruling in its history. In 1858, Abraham Lincoln, a rising figure in the newly born Republican Party, declared the United States a “house divided” between slavery and freedom. In late 1859, militant abolitionist John Brown alarmed the South when he attempted to liberate slaves by taking over a federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. He was promptly captured, tried, and executed and thereupon became a martyr for many northern abolitionists.

Watch this BRI Homework Help video: Dred Scott v. Sandford for more information on the pivotal Dred Scott decision.

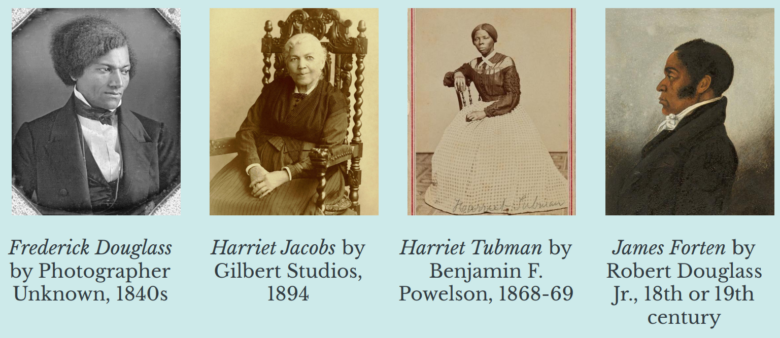

Leaders such as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, Harriet Tubman, and James Forten all worked for the cause of abolition and equality.

As the debate over slavery continued on the national stage, formerly enslaved and free black men and women spoke out against the evils of slavery. Slave narratives such as those by Frederick Douglass, Solomon Northrup, and Harriet Jacobs humanized the experience of slavery. Their vivid, heartbreaking accounts of their own enslavement strengthened the moral cause of abolition. At the same time, enslaved men and women made the brave and dangerous decision to run away. Some ran on their own, and others used the Underground Railroad, a network of secret “conductors” and “stations” that helped enslaved people escape to the North and, after 1850, to Canada. The most famous of these conductors was Harriet Tubman, who traveled to the South about 12 times to lead approximately 70 men and women to freedom. Free blacks faced their own challenges. Leaders such as Benjamin Banneker, James Forten, David Walker, and Maria Stewart spoke out against racist attitudes and laws that sought to limit their political and civil rights.

This map shows the concentration of slaves in the southern United States as derived from the 1860 U.S. Census. The so-called “Border states”—Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and after 1863, West Virginia—allowed slavery but remained loyal to the Union. Credit: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

By 1860, the atmosphere in the United States was combustible. With the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in November of that year, the conflict over slavery came to a head. Since Lincoln and Republicans opposed the expansion of slavery and called it a moral evil, seven slaveholding states declared their secession from the United States. And in April 1861, the war came. The next five years of conflict and bloodshed determined the fate of enslaved men, women, and children, and of the Union itself.

Reading Comprehension Questions

- What actions were taken to oppose slavery in the colonial period and Founding era?

- Why did the Constitution not use the words “slave” or “slavery”?

- The invention of the cotton gin

- The Mexican-American War

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- The election of Abraham Lincoln as president

- How did formerly enslaved and free black men and women fight to end slavery?

Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation and Freedom

- Explore the Collection

- Collections in Context

- Teaching the Collection

- Advanced Collection Research

Reconstruction, 1865-1877

Donald Brown, Harvard University, G6, English PhD Candidate

No period in American history has had more wide-reaching implications than Reconstruction. However, white supremacist mythologies about those contentious years from 1865-1877 reigned supreme both inside and outside the academy until the 1960s. Columbia University’s now-infamous Dunning School (1900-1930) epitomizes the dominant narrative regarding Reconstruction for over half of the twentieth century. From their point of view, Reconstruction was a tragic period of American history in which vengeful White Northern radicals took over the South. In order to punish the White Southerners they had just defeated in the Civil War, these Radical Republicans gave ignorant freedmen the right to vote. This resulted in at least 2,000 elected Black officeholders, including two United States senators and 21 representatives. In order to discredit the sweeping changes taking place across the American South, conservative historians argued this period was full of corruption and disorder and proved that Black Americans were not fit to leadership or citizenship.

Thanks to the work of a number of Black and leftist historians—most notably John Roy Lynch, W.E.B. Du Bois, Willie Lee Rose, and Eric Foner—that negative depiction of Reconstruction is being overturned. As Du Bois famously wrote in Black Reconstruction in America (1935), this was a time in which “the slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; and then moved back again toward slavery.” During that short time in the sun, underfunded biracial state governments taxed big planters to pay for education, healthcare, and roads that benefited everyone. There is still much more to be unpacked from this rich period of American history, and Houghton Library contains a wealth of material to further buttress new narratives of that era.

Reconstructing Reconstruction

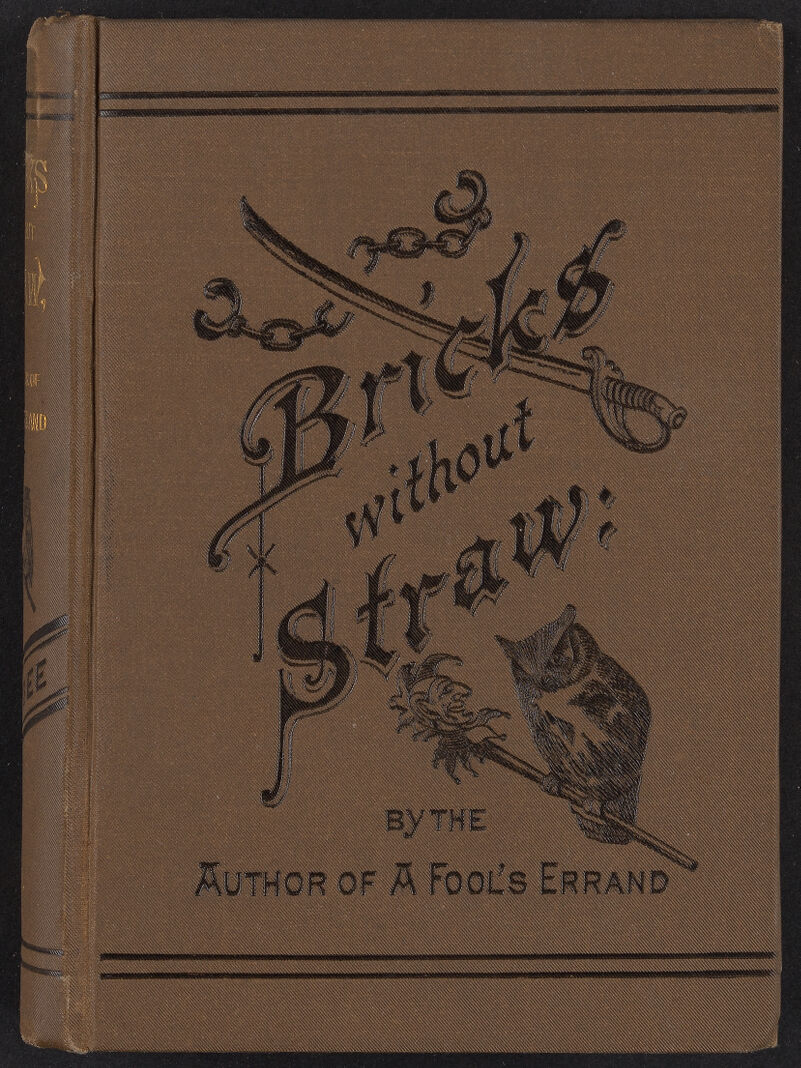

While some academics, like those of the Dunning School, interpreted Reconstruction as doomed to failure, in the years immediately following the Civil War there were many Americans, Black and White, who saw the radical reforms as being sabotaged from the outset. Writer and civil rights activist Albion W. Tourgée published his best selling novel Bricks Without Straw in 1880. Unlike most White authors at the time, Tourgée centered Black characters in his novel, showing how the recently emancipated were faced with violence and political oppression in spite of their attempts to be equal citizens.

In this period, two of the most iconic amendments were implemented. The Fourteenth Amendment ratified several crucial civil rights clauses. The natural born citizenship clause overturned the 1857 supreme court case, Dred Scott v. Sandford , which stated that descendants of African slaves could not be citizens of the United States. The equal protection clause ensured formerly enslaved persons crucial legal rights and validated the equality provisions contained in the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Even though many of these clauses were cleverly disregarded by numerous states once Reconstruction ended, particularly in the Deep South, the equal protection clause was the basis of the NAACP’s victory in the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed another important civil right: the right to vote. No longer could any state discriminate on the basis of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. At Houghton, we have proof of the exhilarating response Black Americans had to the momentous progress they worked so hard to bring about: Nashvillians organized a Fifteenth Amendment Celebration on May 4, 1870. And once again, during the classical period of the Civil Rights Movement, leaders appealed to this amendment to make their case for what became the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Reign of Kings Alpha and Abadon

Lorenzo D. Blackson's fantastical allegory novel, The Rise and Progress of the Kingdoms of Light & Darkness ; Reign of Kings Alpha and Abadon (1867), is one of the most ambitious creative efforts of Black authors during Reconstruction. A Protestant religious allegory in the lineage of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress , Blackson's novel follows his vision of a holy war between good and evil, showing slavery and racial oppression on the side of evil King Abadon and Protestant abolitionists and freemen on the side of good King Alpha. The combination of fantasy holy war, religious pedagogy, and Reconstruction era optimism provide a unique insight to one contemporary Black perspective on the time.

It is important to emphasize that these radical policy initiatives were set by Black Americans themselves. It was, in fact, from formerly enslaved persons, not those who formerly enslaved them, that the most robust notions of freedom were imagined and enacted. With the help of the nation’s first civil rights president, Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877), and Radical Republicans, such as Benjamin Franklin Wade and Thaddeus Stevens, substantial strides in racial advancement were made in those short twelve years. Houghton Library is home to a wide array of examples of said advancement, such as a letter written in 1855 by Frederick Douglass to Charles Sumner, the nation’s leading abolitionist. In it, he argues that Black Americans, not White abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, founded the antislavery movement. That being said, Douglass was appreciative of allies, such as President Grant, of whom he said: “in him the Negro found a protector, the Indian a friend, a vanquished foe a brother, an imperiled nation a savior.” Houghton Library also houses an extraordinary letter dated December 1, 1876 from Sojourner Truth , famous abolitionist and women’s rights activist, who could neither read nor write. She had someone help steady her hand so she could provide a signed letter to a fan, and promised to also send her supporter an autobiography, Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Bondswoman of Olden Time, Emancipated by the New York Legislature in the Early Part of the Present Century: with a History of Her Labors and Correspondence.

In this hopeful time, Black Americans, primarily located in the South, were determined to use their demographic power to demand their right to a portion of the wealth and property their labor had created. In states like South Carolina and Mississippi, which were majority Black at the time, and Louisiana , Alabama, and Georgia , with Black Americans consisting of nearly half of the population, the United States elected its first Black U.S. congressmen. Now that Black Southern men had the power to vote, they eagerly elected Black men to represent their best interests. Jefferson Franklin Long (U.S. congressman from Georgia), Joseph Hayne Rainey (U.S. congressman from South Carolina), and Hiram Rhodes Revels (Mississippi U.S. Senator) all took office in the 41st Congress (1869-1871). These elected officials were memorialized in a lithograph by popular firm Currier and Ives. Other federal agencies, such as the Freedmen’s Bureau , also assisted Black Americans build businesses, churches, and schools; own land and cultivate crops; and more generally establish cultural and economic autonomy. As Frederick Douglass wrote in 1870, “at last, at last the black man has a future.”

Black Americans quickly took full advantage of their newfound freedom in a myriad of ways. Alfred Islay Walden’s story is a particularly remarkable example of this. Born a slave in Randolph County, North Carolina, he only gained freedom after Emancipation. He traveled by foot to Washington, D.C. and made a living selling poems and giving lectures across the Northeast. He also attended school at Howard University on scholarship, graduating in 1876, and used that formal education to establish a mission school and become one of the first Black graduates of New Brunswick Theological Seminary. Walden’s Miscellaneous Poems, Which The Author Desires to Dedicate to The Cause of Education and Humanity (1872) celebrates the “Impeachment of President Johnson,” one of the most racist presidents in American history; “The Election of Mayor Bowen,” a Radical Republican mayor of Washington, D.C. (Sayles Jenks Bowen); and Walden’s own religious convictions, such as in “Jesus my Friend;” among other topics.

Black newspapers quickly emerged during Reconstruction as well, such as the Colored Representative , a Black newspaper based in Lexington, KY in the 1870s. As editor George B. Thomas wrote in an “Extra,” dated May 25, 1871 : “We want all the arts and fashions of the North, East and Western states, for the benefit of the colored people. They cannot know what is going on, unless they read our paper.... Now, we want everything that is a benefit to our colored people. Speeches, debates, and sermons will be published.”

Reconstruction proves that Black people, when not impeded by structural barriers, are enthusiastic civic participants. Houghton houses rich archival material on Black Americans advocating for civil rights in Vicksburg, Mississippi , Little Rock, Arkansas , and Atlanta, Georgia , among other states, in the forms of state Colored Conventions and powerful political speeches . For anyone interested in the long history of the Civil Rights Movement, these holdings are a treasure trove waiting to be mined. Though the moment in the sun was brief, the heat exuded during Reconstruction left a deep impact on progressive Americans and will continue to provide an exemplary political model for generations to come.

Essay on Abolition Of Slavery

Students are often asked to write an essay on Abolition Of Slavery in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Abolition Of Slavery

Introduction.

Slavery is a dark chapter in human history. It was a system where people, known as slaves, were treated as property. They were bought, sold, and forced to work without their consent. The abolition of slavery was a movement to end this cruel practice.

Early Resistance

Slaves always resisted their condition. They would run away, rebel, or even fight for their freedom. This resistance was the first step towards ending slavery. It made people question the morality of owning another human being.

Abolition Movement

In the 18th century, the abolition movement began in earnest. People started speaking out against slavery. They formed groups and campaigned for laws to end slavery. This movement played a crucial role in bringing about the end of slavery.

Key Figures

Many people fought for the end of slavery. People like William Wilberforce, Harriet Tubman, and Frederick Douglass played key roles. They risked their lives to help slaves escape and to change public opinion about slavery.

End of Slavery

The abolition movement led to laws that ended slavery. In the United States, the 13th Amendment in 1865 officially abolished slavery. In other parts of the world, similar laws were passed. This marked the end of legal slavery.

The abolition of slavery was a significant achievement in human rights. It showed that people can change unjust systems. Even today, it serves as a reminder that everyone deserves freedom and respect.

250 Words Essay on Abolition Of Slavery

Slavery is a dark part of human history. It was a time when people were bought and sold like objects. They were forced to work without pay. This essay talks about the end of slavery, known as the abolition of slavery.

What is Abolition?

Abolition means to officially end something. In this context, it means the ending of slavery. This was a big step towards human rights.

Why was Slavery Abolished?

Slavery was abolished because it was wrong and unfair. People began to understand that every human being should be free and have rights. They started to fight against slavery.

How was Slavery Abolished?

The abolition of slavery did not happen overnight. It took many years and a lot of effort. People like William Wilberforce in England and Abraham Lincoln in America fought hard to end slavery. They passed laws to stop it.

Impact of Abolition

The end of slavery had a huge impact. It meant freedom for millions of people. It was a big step towards equality and human rights. But, it did not end all problems. Former slaves faced many challenges, like racism and poverty.

The abolition of slavery was a major event in history. It showed that people can fight against injustice and win. It is a reminder that everyone deserves to be free and treated with respect. We must remember this history to ensure that such wrongs are never repeated.

In conclusion, the abolition of slavery was a significant step towards promoting human rights and equality. It serves as a reminder of the power of collective action against injustice.

500 Words Essay on Abolition Of Slavery

Slavery was a cruel practice where people were treated as property. They were bought, sold, and forced to work without pay. Many people fought against it and worked hard to end it. This fight is known as the abolition of slavery.

When and Where Slavery Existed

Slavery existed in many parts of the world, including America, Africa, and Europe, for many centuries. It was most common in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. People were captured from their homes in Africa and taken to other countries to work on farms and in homes.

The Abolition Movement

The abolition movement was a group of people who wanted to end slavery. They believed it was wrong to treat people as property. Many were brave men and women who risked their lives to help enslaved people gain freedom. This group included people like Harriet Tubman, William Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass.

The Fight Against Slavery in America

In America, the abolition movement gained strength in the 19th century. People began to realize that slavery was wrong and fought to change the laws. The North and South disagreed about this. The North wanted to end slavery, but the South wanted to keep it because their economy depended on it. This disagreement led to the Civil War in 1861.

The End of Slavery

The Civil War ended in 1865, and with it came the end of slavery. President Abraham Lincoln played a big role in this. He signed a law called the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, which declared that all enslaved people in the South were free. After the war, the 13th amendment to the Constitution was added. It made slavery illegal in the entire United States.

The abolition of slavery had a big impact. It meant that millions of people were free and could live their lives as they wanted. But it also led to many challenges. The freed people had to find jobs and homes, and they faced discrimination. Despite these challenges, the end of slavery was a big step towards equality and justice.

The abolition of slavery was a long and hard fight, but it was worth it. It showed that people can stand up against injustice and make a difference. It is an important part of history that reminds us of the value of freedom and equality. Today, we must continue to fight against all forms of discrimination and injustice, just like the abolitionists did.

In conclusion, the abolition of slavery was a significant event that changed the world. It ended a cruel practice and set a path towards equality and justice.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Abolition Of Animal Exploitation

- Essay on A Street

- Essay on A Stranger

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

HISTORIC ARTICLE

Dec 18, 1865 ce: slavery is abolished.

On December 18, 1865, the 13th Amendment was adopted as part of the United States Constitution. The amendment officially abolished slavery, and immediately freed more than 100,000 enslaved people, from Kentucky to Delaware.

Social Studies, U.S. History, World History

Loading ...

On December 18, 1865, the 13th Amendment was adopted as part of the United States Constitution . The amendment officially abolished slavery , and immediately freed more than 100,000 enslaved people, from Kentucky to Delaware. The language used in the 13th Amendment was taken from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance. Yet the 13th Amendment maintains an important exception for keeping people in "involuntary servitude" as "punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." Some scholars say this exception ended slavery in one form only to allow it to continue in another. These laws are sometimes credited with laying the groundwork for the U.S. system of mass incarceration, which disproportionately imprisons Black people. Two years earlier, at the height of the U.S. Civil War , President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared all Blacks held captive in the states who'd rebelled against the United States (as members of the Confederacy ) were free. This did not have a sweeping practical impact, however, as the Confederacy considered itself a separate nation and did not follow U.S. laws, and the proclamation did not free enslaved populations in the “border states” that sided with the United States.

Within five years, Congress passed the 14th and 15th Amendments. These amendments, among the most contested in courts today, established citizenship , equal protection, and voting rights for all male Americans, regardless of race. However, the same suffrage and protections would not be afforded to women of all races until over 50 years later, when Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1919.

At the time, Black people held in slavery by Native Americans in Indian Territory (now the state of Oklahoma) largely remained in bondage. Different factions of various tribes alternatively sided with the Confederacy and the United States. Regardless of their position, the U.S. government treated the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek, and Choctaw as allies of the Confederacy. These tribes signed the Treaty of 1866, which abolished slavery, to normalize relations with the U.S.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

January 24, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

The Abolitionist Movement: Resistance to Slavery From the Colonial Era to the Civil War

The Abolitionist movement in the United States of America was an effort to end slavery in a nation that valued personal freedom and believed “all men are created equal.” Over time, abolitionists grew more strident in their demands, and slave owners entrenched in response, fueling regional divisiveness that ultimately led to the American Civil War .

Slavery Comes To The New World

African slavery began in North America in 1619 at Jamestown, Virginia . The first American-built slave ship, Desire, launched from Massachusetts in 1636, beginning the slave trade between Britain’s American colonies and Africa. From the beginning, some white colonists were uncomfortable with the notion of slavery. At the time of the American Revolution against the English Crown, Delaware (1776) and Virginia (1778) prohibited importation of African slaves; Vermont became the first of the 13 colonies to abolish slavery (1777); Rhode Island prohibited taking slaves from the colony (1778); and Pennsylvania began gradual emancipation in 1780.

The Maryland Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Free Negroes and Others Unlawfully Held in Bondage was founded in 1789, the same year the former colonies replaced their Articles of Confederation with the new Constitution, “in order to form a more perfect union.”

When the U.S. Constitution was written, it made no specific mention of slavery, but it provided for the return of fugitives (which encompassed criminals, indentured servants and slaves). It allowed each slave within a state to be counted as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of determining population and representation in the House of Representatives (Article I, Section 3, says representation and direct taxation will be determined based on the number of “free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three-fifths of all other persons”).

Learn more about

- Slavery in America

The Constitution prohibited importation of slaves, to begin in 1808, but again managed to do so without using the words “slave” or “slavery.” Slave trading became a capital offense in 1819. There existed a general feeling that slavery would gradually pass away. Improvements in technology—the cotton gin and sewing machine—increased the demand for slave labor, however, in order to produce more cotton in Southern states. By the 1830s, many Southerners had shifted from, “Slavery is a necessary evil,” to “Slavery is a positive good.” The institution existed because it was “God’s will,” a Christian duty to lift the African out of barbarism while still exerting control over his “animal passions.”

The Missouri Compromise

Missouri’s appeal for statehood brought a confrontation between free and slave states in Congress in 1820; each feared the other would gain the upper hand. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 set a policy of admitting states in pairs, one slave, one free. (Maine came in at the same time as Missouri.) The compromise prohibited slavery above parallel 36 degrees, 30 minutes in the lands of the Louisiana Purchase, and it included a national Fugitive Slave Law requiring all Americans to return runaway slaves to their owners. The Fugitive Slave Law was upheld in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 1842, but the Missouri Compromise’s prohibitions on the spread of slavery would be found unconstitutional in the 1857 Dred Scott decision.

The Abolitionism Movement Spreads

Although many New Englanders had grown wealthy in the slave trade before the importation of slaves was outlawed, that area of the country became the hotbed of abolitionist sentiment. Abolitionist newspapers and pamphlets sprang into existence. These were numerous enough by 1820 that South Carolina instituted penalties for anyone bringing written anti-slavery material into the state.

These publications argued against slavery as a social and moral evil and often used examples of African American writings and other achievements to demonstrate that Africans and their descendents were as capable of learning as were Europeans and their descendents in America, given the freedom to do so. To prove their case that one person owning another one was morally wrong, they first had to convince many, in all sections of the country, that Negroes, the term used for the race at the time, were human. Yet, even many people among the abolitionists did not believe the two races were equal.

In 1829, David Walker, a freeman of color originally from the South, published An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World in Boston, Massachusetts. It was a new benchmark, pushing abolitionists toward extreme militancy. He called for slaves to rise up against their masters and to defend themselves: “It is no more harm for you to kill a man who is trying to kill you, than it is for you to take a drink of water when thirsty.” As early as 1800, a Virginia slave known as Gabriel Prosser had attempted an uprising there, but it failed when two slaves betrayed the plan to their masters.

Walker’s publication was too extreme even for most abolition leaders, including one of the most renowned, William Lloyd Garrison . In 1831, Garrison founded The Liberator, which would become the most famous and influential of abolitionist newspapers. That same year, Virginia debated emancipation, marking the last movement for abolition in the South prior to the Civil War. Instead, that year the Southampton Slave Riot, also called Nat Turner’s Rebellion, resulted in Virginia passing new regulations against slaves. Fears of slave revolts like the bloody Haitian Revolution of 1791–1803 were never far from Southerners’ minds. Publications like An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World led white Southerners to conclude Northern abolitionists intended to commit genocide against them.

In 1833 in Philadelphia, the first American Anti-Slavery Society Convention convened. In a backlash, anti-abolition riots broke out in many northeastern cities, including New York and Philadelphia, during 1834-35. Several Southern states, beginning with the Carolinas, made formal requests to other states to suppress abolition groups and their literature. In Illinois, the legislature voted to condemn abolition societies and their agitation; Delegate Abraham Lincoln voted with the majority, then immediately co-sponsored a bill to mitigate some of the language of the earlier one. The U.S. House of Representatives adopted a gag rule, automatically tabling abolitionist proposals.

The first national Anti-Slavery Convention was held in New York City in 1837, and the following year the second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women met in Philadelphia; the latter resulted in pro-slavery riots. The Liberty Party, a political action group, held its first national convention, at Albany, N.Y., in 1839. That same year, Africans mutinied aboard the Spanish slave ship Amistad and asked New York courts to grant them freedom. Their plea was answered affirmatively by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1841.

Frederick Douglass: A Black Abolitionist

Frederick Douglass —a former slave who had been known as Frederick Bailey while in slavery and who was the most famous black man among the abolitionists—broke with William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator, after returning from a visit to Great Britain, and founded a black abolitionist paper, The North Star. The title was a reference to the directions given to runaway slaves trying to reach the Northern states and Canada: Follow the North Star. Garrison had earlier convinced the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society to hire Douglass as an agent, touring with Garrison and telling audiences about his experiences in slavery. In England, however, Douglass had experienced a level of independence he’d never known in America and likely wanted greater independece for his actions here.

Working with Douglass on The North Star was another black man, Martin R. Delaney, who gave up publishing his own paper, The Mystery, to join with Douglass. Born to a free mother in Virginia (in what is now the eastern panhandle of West Virginia), Delaney had never been a slave, but he had traveled extensively in the South. After Uncle Tom’s Cabin became a bestseller, he attempted to achieve similar success for himself by penning a semi-fictional account of his travels, Blake: The Huts of America. In 1850, he was one of three black men accepted into Harvard Medical School, but white students successfully petitioned to have them removed. No longer believing that merit and reason could allow members of his race to have an equal opportunity in white society, he became an ardent black nationalist. In 1859, he traveled to Africa and negotiated with eight tribal chiefs in Abbeokuta for land, on which he planned to establish a colony for skilled and educated African Americans. The agreement fell apart, and he returned to America where, near the end of the Civil War, he became the first black officer on a general’s staff in the history of the U.S. Army.

- The Seneca Falls Convention

In 1848, the first Women’s Rights convention was held, in Seneca Falls, N.Y. Outside of the Society of Friends (“Quakers”), women were often denied the opportunity to speak at abolitionist meetings. The women’s rights movement produced many outspoken opponents of slavery, including Elizabeth Cody Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. In fact, women’s equality and abolition became inextricably linked in the minds of many Southerners. In the 20th century, that lingering animosity nearly defeated the constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote.

Although Delaney’s planned African colony failed, in 1849 Great Britain recognized the African colony of Liberia as a sovereign state. It had been founded in 1822 as a colony for free-born blacks, freed slaves and mulattoes (mixed race) from the United States. A number of Americans who opposed slavery (including Abraham Lincoln for a time and the aforementioned Delany) felt that the two races could never live successfully together, and the best hope for Negroes was to return them to freedom in Africa. However, the slave trade between Africa and the Western Hemisphere (the Caribbean and South America) had never ended, and many American ship owners and captains were enjoying something of a golden era of slave-trading while the U.S. and Europe looked the other way. Even if freed slaves had been sent to Africa, many would have wound up back in slavery south of the United States. Only in the late 1850s did Britain step up its anti-slavery enforcement on the high seas, leading America to increase its efforts somewhat.

When the federal government passed a second, even more stringent fugitive slave act in 1850, several states responded by passing personal liberty laws. The following year, Sojourner Truth (Isabella Baumfree) gave a now-famous speech, “Ain’t I a Woman,” at the Women’s Rights convention in Akron, Ohio. Born a slave in New York, she walked away from her owner after she felt she had contributed enough to him. In the late 1840s, she dictated a memoir, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave, published by Garrison in 1850. She began to tour, speaking against slavery and in favor of women’s rights.

Harriet Tubman and The Underground Railroad

While Sojourner Truth, Douglass, Delaney and others wrote and spoke to end slavery, a former slave named Harriet Tubman, nee Harriet Ross, was actively leading slaves to freedom. After escaping from bondage herself, she made repeated trips into Dixie to help others. Believed to have helped some 300 slaves to escape, she was noted for warning those she was assisting that she would shoot any of them who turned back, because they would endanger herself and others she was assisting.

- Harriet Tubman

- The Underground Railroad

Tubman was an agent of the Underground Railroad, a system of “safe houses” and way stations that secretly helped runaways. The trip might begin by hiding in the home, barn or other location owned by a Southerner opposed to slavery, and continuing from place to place until reaching safe haven in a free state or Canada. Those who reached Canada did not have to fear being returned under the Fugitive Slave Act. Several communities and individuals claim to have created the term “Underground Railroad.” In the southern section of states on the north bank of the Ohio River, a “reverse underground railroad” operated; blacks in those states were kidnapped, whether they had ever been slaves or not, and taken South to sell through a series of clandestine locations.

Harriet Beecher Stowe: Abolitionist and Author

In 1852, what may have been the seminal event of the abolition movement occurred. Harriet Beecher Stowe, an abolitionist who had come to know a number of escaped slaves while she was living in Cincinnati, authored the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It presented a scathing view of Southern slavery, filled with melodramatic scenes such as that of the slave Eliza escaping with her baby across the icy Ohio River:

The huge green fragment of ice on which she alighted pitched and creaked as her weight came on it but she stayed there not a moment. With wild cries and desperate energy she leaped to another and still another cake;—stumbling,—leaping,—slipping—springing upwards again! Her shoes are—gone her stockings cut from her feet—while blood marked every step; but she saw nothing, felt nothing, till dimly, as in a dream, she saw the Ohio side and a man helping her up the bank.

- Harriet Beecher Stowe

Critics pointed out that Stowe had never been to the South, but her novel became a bestseller in the North (banned in the South) and the most effective bit of propaganda to come out of the abolitionist movement. It galvanized many who had been sitting on the sidelines. Reportedly, when President Abraham Lincoln met Stowe during the Civil War he said to her, “So you’re the little woman who started this big war.”

Abolitionists Invoke A Higher Law

Abolitionists became increasingly strident in their condemnations of slave owners and “the peculiar institution of slavery.” Often, at Fourth of July gatherings of abolition societies, they reportedly used the occasion to denounce the U.S. Constitution as a “covenant with death, and an agreement with hell.” Many of them came to believe in “higher law,” that a moral commitment to ending slavery took precedent over observing those parts of the Constitution that protected slavery and, in particular, they refused to obey the Fugitive Slave Act. Slave owners or their representatives traveling north to reclaim captured runaways were sometimes set upon on abolitionists mobs; even local lawmen were sometimes attacked. In the South, this fueled the belief that the North expected the South to obey all federal laws but the North could pick and choose, further driving the two regions apart.

Abolitionism, Politics and the Election Of Abraham Lincoln

The abolition movement became an important element of political parties. Although the Native American Party (derisively called the Know-Nothing Party because when member were asked about the secretive group they claimed to “know nothing”) opposed immigrants, they also opposed slavery. So did many Whigs and the Free Soil Party. In 1856, these coalesced into the Republican Party. Four years later, its candidate, Abraham Lincoln , captured the presidency of the United States.

John Brown: Abolitionism’s Fiery Crusader

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 allowed the citizens of those territories to determine for themselves whether the state would be slave or free. Proponents of both factions poured into the Kansas Territory, with each side trying to gain supremacy, often through violence. After pro-slavery groups attacked the town of Lawrence in 1856, a radical abolitionist named John Brown led his followers in retaliation, killing five pro-slavery settlers. The territory became known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

Dred Scott V. Sanford

The 1857 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sanford denied citizenship to anyone of African blood and held the Missouri Compromise of 1820 to be unconstitutional. While Southern states had been passing laws prohibiting “Negro citizenship” and further restricting the rights even of freemen of color (Virginia in 1857 prohibited slaves from smoking and from standing on sidewalks, among other restrictions), one Northern state after another had been passing laws granting citizenship to their black residents. The Court’s findings upended that, and the ruling outraged many Northerners. Abraham Lincoln revived his personal political career, coming out of a self-imposed semi-retirement to speak out against the Dred Scott decision .

- The Dred Scott Decision

The year 1859 saw two events that were milestones in the history of slavery and abolition in America. The ship Clotilde landed in Mobile, Alabama. Though the importation of slaves had been illegal in America since 1808, Clotilde carried 110 to 160 African slaves. The last slave ship ever to land in the United States, it clearly demonstrated how lax the enforcement of the anti-importation laws was.

John Brown’s Raid On Harpers Ferry

Nearly 1,000 miles northeast of Mobile, on the night of October 16, 1859, John Brown—the radical abolitionist who had killed proslavery settlers in Kansas— led 21 men in a raid to capture the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). Though Brown denied it, his plan was to use the arsenal’s weapons to arm a slave uprising. He and his followers, 16 white men and five black ones, holed up in the arsenal after they were discovered, and were captured there by a group of U.S. Marines commanded by an Army lieutenant colonel, Robert E. Lee. Convicted of treason against Virginia, Brown was hanged December 2.

Initial reaction in the South was that this was the work of a small group of fanatics, but when Northern newspapers, authors and legislators began praising him as a martyr—a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier eulogizing Brown was published in the New York Herald Tribune less than a month after the execution—their actions were taken as further proof that Northern abolitionists wished to carry out genocide of white Southerners. The flames were fanned higher as information came out that Brown had talked other abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, about his plans and received financial assistance from some of them.

Abraham Lincoln: Abolitionist President

Following Abraham Lincoln ‘s election to the presidency in 1860, Southern states began seceding from the Union. Though personally opposed to slavery and convinced the United States was going to have to be all free or all slave states—”a house divided against itself cannot stand”—he repeatedly said he would not interfere with slavery where it existed. But he adamantly opposed its expansion into territories where it did not exist, and slave owners were determined that they had to be free to take their human property with them if they chose to move into those territories.

Less than two years into the civil war that began over Southern secession, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation . It freed all slaves residing in areas of the nation currently in rebellion. Often ridiculed, both then and now, because it only freed slaves in areas that did not recognize Lincoln’s authority, it meant that Union Army officers no longer had to return runaway slaves to their owners because, as the armies advanced, slaves in the newly captured areas were considered free. It also effectively prohibited European nations that had long since renounced slavery from entering the war on the side of the South.

The 13th Amendment: The Abolitionism Movement Triumphs

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution , declared ratified on December 18, 1865, ended slavery in the United States—at least in name. During the Reconstruction Era, Southern states found ways to “hire” black workers under terms that were slavery in all but name, even pursuing any who ran off, just as they had in the days of the Underground Railroad.

Abolition had been achieved, but the lessons learned by those in the abolition movement would be applied to other social concerns in the decades to come, notably the temperance and woman’s suffrage movements.

Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade Essay

Many historians pay close attention to the reasons why slavery persisted for a long time in some parts of the United States. Moreover, much attention is paid to the reasons why so many southerners defended this social institution, even though they did not belong to the so-called plantation aristocracy.

To a great extent, this outcome can be attributed to such factors to the influence of racist attitudes, the fear of violence or rebellion, and economic interests of many people who perceived the abolition of slavery as a threat to their welfare. To some degree, these factors contributed to the outbreak of the American Civil War that dramatically transformed the social and political life of the country. These are the main details that should be examined.

The persistent defense of slavery can be partly explained by the widespread stereotypes and myths which were rather popular in the South. For instance, one can mention the belief according to which the living conditions of slaves were much better, especially in comparison with European workers or those people who lived in the northern parts of the United States. These arguments were expressed by John Calhoun who regarded slavery as “a positive good” (1837). This statement implied that black people could even be satisfied with their subordinate status.

He said that under the rule of white people, slaves could enjoy more prosperity (Calhoun, 1837). These are some of the details that should not be disregarded. To some degree, this justification of slavery was based on the belief that black people were not self-sufficient. Therefore, one should not neglect the impact of racism on the worldviews and attitudes of many southerners who did not always question the propaganda which was imposed on them.

Overall, pro-slavery politicians such as John Calhoun believed the abolition of slavery could produce only detrimental results on various stakeholders, including black people. These are some of the main details that should be distinguished. One should keep in mind that many people living in the South did not pay much attention to the experiences of black slaves. They did not reflect on the cruel treatment of black people who were often dehumanized.

Additionally, it is important to examine the experiences of people who did not belong to the upper classes of the Southern society. Many of these people were farmers, and they were adversely affected by the competition with slave owners (Davidson et al., 2012). In many cases, their farms could be ruined in the course of this struggle. Moreover, many of them could not even afford a slave (Davidson et al., 2012). Nevertheless, they did not object to the existence of slavery as a social institution.

They believed that that the emancipation of slaves could eventually threaten their own existence. In particular, many of them were afraid of violence or rebellion. This is one of the reasons why they did not support the abolitionist movement. So, they could reconcile themselves with slavery, even though their own interests were significantly impaired. Secondly, they did not perceive black people as human beings who could deserve empathy or compassion. As a result, many of these people defended slavery and even fought for the interests of slave owners. This is one of the details should not be overlooked because it is important for understanding the cause of the civic conflict in the United States.

It should be noted that trans-Atlantic slave trade was abolished long before the Civil War in the United States (Oldfield, 2012). Moreover, they could prohibit slave trade within a state. Nevertheless, policy-makers could not easily abolish slavery as an institution, even though many people believed that this practice violated every ethical law. There were many interest groups that did not want to abolish slavery. These people believed that their investments in commerce, agriculture, or industry could be harmed by the abolition of slavery (Davidson et al., 2012).

Moreover, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were many people who owned hundreds of slaves. They believed that slavery had been critical for their economic prosperity. As a result, there was no legal support of the abolitionist movement in some parts of the United States. This tendency was particularly relevant if one speaks about the South in which the use of slave labor was often required. This is one of the details that should be distinguished.

On the whole, this discussion indicates that there were several barriers to the abolition of slavery in the South. Much attention should be paid to the influence of racist attitudes of many people who were firmly convinced that slaves could be deprived of their right to humanity. In their opinion, this practice was quite acceptable from an ethical viewpoint. Additionally, it is vital to remember about the influence about the use of propaganda that shaped the attitudes of many people. Finally, one should not forget about the economic interests of many people who regarded the abolitionist movement as a threat to their financial security. These are some of the major aspects that can be identified.

Reference List

Calhoun, J. (1837). Slavery a Positive Good .

Davidson, J., Delay, B., Herman, B., Leigh, C., & Lytle, M. (2012). US: A Narrative History Volume 1: To 1877 . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Oldfield, J. (2012). British Anti-slavery . Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 26). Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/

"Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade." IvyPanda , 26 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade'. 26 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/.

1. IvyPanda . "Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/.

- Community Health: Calhoun County Senior Services

- Role of Quakers in the Abolitionist Movement

- James Monroe’s “Annual Message to Congress”

- The Abolitionist Movement

- The American Civil War Period

- Discussion of Abolitionist Movement

- Slavery as an Institution in America

- Frederick Douglas and the Abolitionist Movement

- Abolitionist Movement: Attitudes to Slavery Reflected in the Media

- Abolition of Slavery in Brazil

- Confederation Articles and 1787 Constitution

- The Movie "GLORY 1989" by Edward Zwick Analysis

- The Grave Injustices of the Salem Witchcraft Trials

- The Three Rs of the New Deal in the United States History

- Peniel Joseph' Views on Barack Obama

The Abolition of Slavery

How it works

There was a drastic change brought about in the South during the 1860’s. The Union and the Confederacy at war, the abolition of slavery, and the Reconstruction of the South. The life of the south began to take a turn for the unknown. Many people who were once wealthy, living lavishly, and successful, were now poor field or mill workers. People no longer had their successful businesses or plantations. The Civil War greatly impacted the world, in Gone With The Wind, one woman’s experience changed her life forever.

(We need a thesis statement that introduces and states your answers for the prompts in one sentence here.)

Gone With the Wind was a movie that displayed the troubles and hardships of life before and after the Civil War. The main character was Scarlett O’Hara. Scarlett was the strong-willed, determined, and spoiled daughter of a wealthy plantation owner. She lived on a plantation called Tara in Georgia. Before the war, Scarlett seemed content with her life, she was pampered with whatever she desired and had maids who did all of her needed work. After the war, Scarlett was poor and no longer living lavishly. In fact, she became a feminist. Scarlett was working in the mill, fields, and learning to take on responsibility. Along with many other women who had to work while their husbands were away at war. For example, Scarlett began her own lumber business and worked hard to provide for herself and her family. She married several times for money. Also,

During this time period, there were many different issues in the South. One of the biggest was slavery. Slavery was vividly shown throughout the movie. Black individuals served as maids, servants, field hands, and were treated less than the white people.(Provide example) Slaves wore old, battered clothing, and were talked to any kind of way. Slavery was not the only issue, there was a class issue among the white people as well. Many white people were rich, wore expensive clothing, and had thriving plantations. Others had money, but not as much to thrive like others. For example, Scarlett was born with fortune, but she had to work and marry for money after the war. The Civil War changed class boundaries. Once slavery was abolished, the owners had only a few servants who stayed to work, they were then forced to take on the hardships. White people now had to work in their own fields, plant and maintain crops, clean for themselves, and take care of their kids.

The war brought many new changes to society. Before and after, its impact was greater than ever imagined. Before the war, things were unfair. There was slavery. White people were treated with more respect and greater authority than black people. In the movie, before the Civil War, Scarlett had a great life. She was well taken care of, pampered, and didn’t have a job in the world to do except look pretty. After the war, Scarlett and many other women had to take on big responsibilities. Working in place of the men, reality had finally struck, Scarlett saw that she had to step up, and mature in order to provide money and food for her family.

In conclusion, there were many different changes that occured as an effect of the Civil War. There was the abolition of slavery, the Reconstruction of the South, and people had a new way of life. Black people were now free, and had a fair chance of living decently. White people were now having to take on the challenges of their own work. This affected the class issues and society. Now

Cite this page

The Abolition Of Slavery. (2022, Feb 10). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-abolition-of-slavery/

"The Abolition Of Slavery." PapersOwl.com , 10 Feb 2022, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-abolition-of-slavery/

PapersOwl.com. (2022). The Abolition Of Slavery . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-abolition-of-slavery/ [Accessed: 26 Apr. 2024]

"The Abolition Of Slavery." PapersOwl.com, Feb 10, 2022. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-abolition-of-slavery/

"The Abolition Of Slavery," PapersOwl.com , 10-Feb-2022. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-abolition-of-slavery/. [Accessed: 26-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2022). The Abolition Of Slavery . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-abolition-of-slavery/ [Accessed: 26-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Abolition of Slavery

Introduction, general overviews.

- Textbooks and Surveys

- Bibliographies and Encyclopedias

- Document Collections in Print

- Electronic Resources

- Antislavery and Abolition

- Abolition of the Slave Trade

- Emancipation, Manumission, and Colonization

- Rebellions and Revolution

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- United States

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Brazilian Independence

- Domestic Slave Trades in the Americas

- Emancipation

- European, Javanese, and African and Indentured Servitude in the Caribbean

- French Emancipation

- Internal Slave Migrations in the Americas

- Interracial Marriage in the Atlantic World

- Literature, Slavery, and Colonization

- Manumission

- Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

- Philanthropy

- Phillis Wheatley

- Poetry in the British Atlantic

- Public Memory and Heritage of Slavery

- Reconstruction, Democracy, and United States Imperialism

- Representations of Slavery

- Slave Rebellions

- Slave Resistance in the Atlantic World

- Slavery and Fear

- Slavery in British America

- Slavery in Dutch America and the West Indies

- Slavery in New England

- South Atlantic Creole Archipelagos

- The Atlantic Slave Trade

- The Growth and Decline of Slavery in North America

- The Guianas

- The Slave Trade and Natural Science

- West Indian Economic Decline

- William Wilberforce

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Ecology and Nineteenth-Century Anglophone Atlantic Literature

- Science and Technology (in Literature of the Atlantic World)

- The Danish Atlantic World

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Abolition of Slavery by Michael Guasco , Matthew Wyman-McCarthy LAST REVIEWED: 23 June 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 23 June 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199730414-0001

The abolition of slavery in the Atlantic world occurred during the 19th century, but its origins are generally recognized to be the intellectual ferment of the 18th-century Enlightenment, the political turmoil of the Age of Revolution, and the economic transformations associated with the development of modern industrial capitalism. Although antislavery ideas circulated much more widely beginning in the 1760s, the first sustained effort to do something about slavery began in the 1780s, particularly with the British campaign to end the slave trade. The revolution in Saint Domingue added a new sense of urgency to the issue in France, Great Britain, and the United States (as did each of the increasingly troubling slave rebellions that erupted elsewhere in the region during this era), but it was not until the first decade of the 19th century that the British and US governments abolished the trade and made efforts to suppress it throughout the Atlantic world. Slowly thereafter, slavery would be outlawed in many of the newly independent Latin American nations, throughout the British Empire in 1833, and in the French colonies in 1848. Not until the 1860s would slavery come to a halt in the United States, followed by Cuba and Brazil in the 1880s. Scholars have demonstrated that there were many reasons for the abolition of slavery, including the heroic efforts of enslaved people and radical abolitionists alike. As important as moral outrage and popular pressure were to the effort, however, abolition was also facilitated by changing economic and political circumstances. The language of liberty that pervaded the revolutionary Atlantic world inevitably destabilized the ideological foundation of the Atlantic slave system. At the same time, new agricultural and technological innovations made it possible for European elites to imagine viable, and profitable, alternatives to the plantation complex that had been constructed during the preceding centuries. Much has been written about the end of slavery, but scholars are nonetheless still trying to figure out how the component parts of transatlantic abolitionism fit together into a seamless whole.

The abolition of slavery was once imagined as the logical outgrowth of intellectual transformations associated with the Enlightenment. The economic interpretation in Williams 1944 , however, forever altered scholarly analyses of both the rise and fall of slavery in the Atlantic world. There is now little support for the argument that the plantation complex was in decline during the 19th century, but scholarly works such as Blackburn 1988 have been sympathetic to the idea that economic self-interest motivated Europeans to abolish slavery. Others, such as Davis 1975 , Davis 2006 , and Drescher 2009 , emphasize the determinative power of radical social ideas and humanitarian impulses. Klein 1993 demonstrates that the effort to end slavery was a long and often frustrating global phenomenon. Hochshild 2005 is among the most readable synthetic works designed for a general audience.

Blackburn, Robin. The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848 . London: Verso, 1988.

A sweeping synthetic work demonstrating that a combination of economic, political, and intellectual changes brought about an end to slavery. Particularly valuable for its comprehensive approach to the subject.

Davis, David Brion. The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1975.

Classic political and intellectual history that privileges the actions and ideas of elites over the actions of rebels and revolutionaries. Especially attuned to developments in the United States.

Davis, David Brion. Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World . New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Thematic presentation that emphasizes the author’s idiosyncratic interests in various aspects of slavery. The final four chapters detail the history of abolitionism in Great Britain and the United States.

Drescher, Seymour. Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511770555

Impressive survey with greater geographic coverage and a lengthier temporal scope than most works. Emerging as the standard by which other surveys are measured. Drescher’s earlier works are also worth consulting, particularly Econocide: British Slavery in the Era of Abolition (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1977), and Capitalism and Antislavery: British Mobilization in Comparative Perspective (London: Macmillan, 1986).

Hochshild, Adam. Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

An engaging narrative written primarily for an audience of nonspecialists. Served as the basis for the film Amazing Grace (2006). Largely concerned with the British world.

Klein, Martin A., ed. Breaking the Chains: Slavery, Bondage, and Emancipation in Modern Africa and Asia . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993.

Although they stray well into the modern era and far beyond the confines of the Atlantic world, the essays in this volume are an important reminder of the pervasiveness of slavery and the long struggle to abolish it worldwide.

Williams, Eric. Capitalism and Slavery . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1944.

Classic work in which the author contends not only that slavery financed the Industrial Revolution but also that the rise of capitalism led to the downfall of slavery. Often criticized for the author’s economic determinism, but still routinely cited.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Atlantic History »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abolition of Slavery

- Abolitionism and Africa

- Africa and the Atlantic World

- African American Religions

- African Religion and Culture

- African Retailers and Small Artisans in the Atlantic World

- Age of Atlantic Revolutions, The

- Alexander von Humboldt and Transatlantic Studies

- America, Pre-Contact

- American Revolution, The

- Anti-Catholicism and Anti-Popery

- Army, British

- Art and Artists

- Asia and the Americas and the Iberian Empires

- Atlantic Biographies

- Atlantic Creoles

- Atlantic History and Hemispheric History

- Atlantic Migration

- Atlantic New Orleans: 18th and 19th Centuries

- Atlantic Trade and the British Economy

- Atlantic Trade and the European Economy

- Bacon's Rebellion

- Barbados in the Atlantic World

- Barbary States

- Berbice in the Atlantic World

- Black Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Bolívar, Simón

- Borderlands

- Bourbon Reforms in the Spanish Atlantic, The

- Brazil and Africa

- Britain and Empire, 1685-1730

- British Atlantic Architectures

- British Atlantic World

- Buenos Aires in the Atlantic World

- Cabato, Giovanni (John Cabot)

- Cannibalism

- Captain John Smith

- Captivity in Africa

- Captivity in North America

- Caribbean, The

- Cartier, Jacques

- Catholicism

- Cattle in the Atlantic World

- Central American Independence

- Central Europe and the Atlantic World

- Chartered Companies, British and Dutch

- Chinese Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World

- Church and Slavery

- Cities and Urbanization in Portuguese America

- Citizenship in the Atlantic World

- Class and Social Structure

- Coastal/Coastwide Trade

- Cod in the Atlantic World

- Colonial Governance in Spanish America

- Colonial Governance in the Atlantic World

- Colonialism and Postcolonialism

- Colonization, Ideologies of

- Colonization of English America

- Communications in the Atlantic World

- Comparative Indigenous History of the Americas

- Confraternities

- Constitutions

- Continental America

- Cook, Captain James

- Cortes of Cádiz

- Cosmopolitanism

- Credit and Debt

- Creek Indians in the Atlantic World, The

- Creolization

- Criminal Transportation in the Atlantic World

- Crowds in the Atlantic World

- Death in the Atlantic World

- Demography of the Atlantic World

- Diaspora, Jewish

- Diaspora, The Acadian

- Disease in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Production and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Dreams and Dreaming

- Dutch Atlantic World

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Caribbean and Guianas, The

- Early Modern Amazonia

- Early Modern France

- Economy and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Economy of British America, The

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Empire and State Formation

- Enlightenment, The

- Environment and the Natural World

- Europe and Africa

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Northern

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Western

- European Enslavement of Indigenous People in the Americas

- European, Javanese and African and Indentured Servitude in...

- Evangelicalism and Conversion

- Female Slave Owners

- First Contact and Early Colonization of Brazil

- Fiscal-Military State

- Forts, Fortresses, and Fortifications

- Founding Myths of the Americas

- France and Empire

- France and its Empire in the Indian Ocean

- France and the British Isles from 1640 to 1789

- Free People of Color

- Free Ports in the Atlantic World

- French Army and the Atlantic World, The

- French Atlantic World

- French Revolution, The

- Gender in Iberian America

- Gender in North America

- Gender in the Atlantic World

- Gender in the Caribbean

- George Montagu Dunk, Second Earl of Halifax

- Georgia in the Atlantic World

- German Influences in America

- Germans in the Atlantic World

- Giovanni da Verrazzano, Explorer

- Glorious Revolution

- Godparents and Godparenting

- Great Awakening

- Green Atlantic: the Irish in the Atlantic World

- Guianas, The

- Haitian Revolution, The

- Hanoverian Britain

- Havana in the Atlantic World

- Hinterlands of the Atlantic World

- Histories and Historiographies of the Atlantic World

- Hunger and Food Shortages

- Iberian Atlantic World, 1600-1800

- Iberian Empires, 1600-1800

- Iberian Inquisitions

- Idea of Atlantic History, The

- Impact of the French Revolution on the Caribbean, The

- Indentured Servitude

- Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World, Indian

- India, The Atlantic Ocean and

- Indigenous Knowledge

- Indigo in the Atlantic World

- Ireland and the Atlantic World

- Iroquois (Haudenosaunee)

- Islam and the Atlantic World

- Itinerant Traders, Peddlers, and Hawkers

- Jamaica in the Atlantic World

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jews and Blacks

- Labor Systems

- Land and Propert in the Atlantic World

- Language, State, and Empire

- Languages, Caribbean Creole

- Latin American Independence

- Law and Slavery

- Legal Culture

- Leisure in the British Atlantic World

- Letters and Letter Writing

- Literature and Culture

- Literature of the British Caribbean

- Literature, Slavery and Colonization

- Liverpool in The Atlantic World 1500-1833

- Louverture, Toussaint

- Maps in the Atlantic World

- Maritime Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Markets in the Atlantic World

- Maroons and Marronage

- Marriage and Family in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture of Slavery in the British Atlantic

- Medicine in the Atlantic World

- Mental Disorder in the Atlantic World

- Mercantilism

- Merchants in the Atlantic World

- Merchants' Networks

- Migrations and Diasporas

- Minas Gerais

- Mining, Gold, and Silver

- Missionaries

- Missionaries, Native American

- Money and Banking in the Atlantic Economy

- Monroe, James

- Morris, Gouverneur

- Music and Music Making

- Napoléon Bonaparte and the Atlantic World

- Nation and Empire in Northern Atlantic History

- Nation, Nationhood, and Nationalism

- Native American Histories in North America

- Native American Networks

- Native American Religions

- Native Americans and Africans

- Native Americans and the American Revolution

- Native Americans and the Atlantic World

- Native Americans in Cities

- Native Americans in Europe

- Native North American Women

- Native Peoples of Brazil

- Natural History

- Networks for Migrations and Mobility

- Networks of Science and Scientists

- New England in the Atlantic World

- New France and Louisiana

- New York City

- Nineteenth-Century France

- Nobility and Gentry in the Early Modern Atlantic World

- North Africa and the Atlantic World

- Northern New Spain