Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on September 5, 2024.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2024, September 05). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved October 19, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 4: Theoretical frameworks for qualitative research

Tess Tsindos

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe qualitative frameworks.

- Explain why frameworks are used in qualitative research.

- Identify various frameworks used in qualitative research.

What is a Framework?

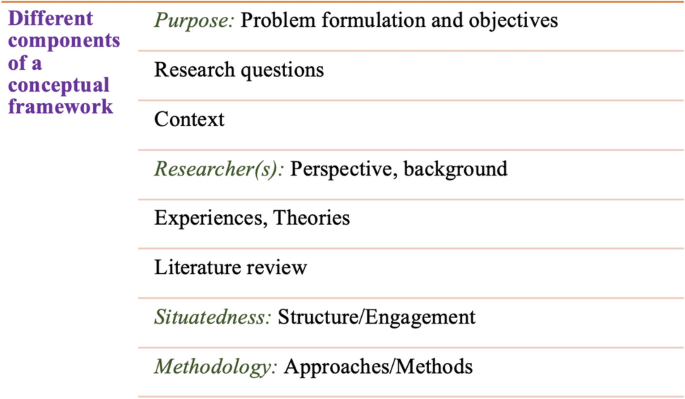

A framework is a set of broad concepts or principles used to guide research. As described by Varpio and colleagues 1 , a framework is a logically developed and connected set of concepts and premises – developed from one or more theories – that a researcher uses as a scaffold for their study. The researcher must define any concepts and theories that will provide the grounding for the research and link them through logical connections, and must relate these concepts to the study that is being carried out. In using a particular theory to guide their study, the researcher needs to ensure that the theoretical framework is reflected in the work in which they are engaged.

It is important to acknowledge that the terms ‘theories’ ( see Chapter 3 ), ‘frameworks’ and ‘paradigms’ are sometimes used interchangeably. However, there are differences between these concepts. To complicate matters further, theoretical frameworks and conceptual frameworks are also used. In addition, quantitative and qualitative researchers usually start from different standpoints in terms of theories and frameworks.

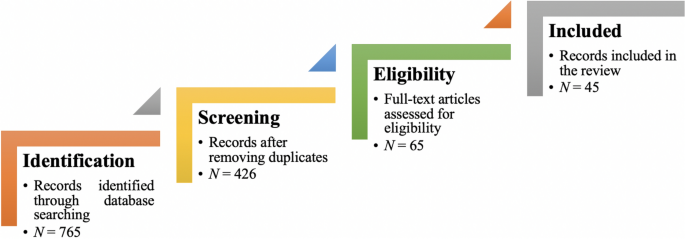

A diagram by Varpio and colleagues demonstrates the similarities and differences between theories and frameworks, and how they influence research approaches. 1(p991) The diagram displays the objectivist or deductive approach to research on the left-hand side. Note how the conceptual framework is first finalised before any research is commenced, and it involves the articulation of hypotheses that are to be tested using the data collected. This is often referred to as a top-down approach and/or a general (theory or framework) to a specific (data) approach.

The diagram displays the subjectivist or inductive approach to research on the right-hand side. Note how data is collected first, and through data analysis, a tentative framework is proposed. The framework is then firmed up as new insights are gained from the data analysis. This is referred to as a specific (data) to general (theory and framework) approach .

Why d o w e u se f rameworks?

A framework helps guide the questions used to elicit your data collection. A framework is not prescriptive, but it needs to be suitable for the research question(s), setting and participants. Therefore, the researcher might use different frameworks to guide different research studies.

A framework informs the study’s recruitment and sampling, and informs, guides or structures how data is collected and analysed. For example, a framework concerned with health systems will assist the researcher to analyse the data in a certain way, while a framework concerned with psychological development will have very different ways of approaching the analysis of data. This is due to the differences underpinning the concepts and premises concerned with investigating health systems, compared to the study of psychological development. The framework adopted also guides emerging interpretations of the data and helps in comparing and contrasting data across participants, cases and studies.

Some examples of foundational frameworks used to guide qualitative research in health services and public health:

- The Behaviour Change Wheel 2

- Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) 3

- Theoretical framework of acceptability 4

- Normalization Process Theory 5

- Candidacy Framework 6

- Aboriginal social determinants of health 7(p8)

- Social determinants of health 8

- Social model of health 9,10

- Systems theory 11

- Biopsychosocial model 12

- Discipline-specific models

- Disease-specific frameworks

E xamples of f rameworks

In Table 4.1, citations of published papers are included to demonstrate how the particular framework helps to ‘frame’ the research question and the interpretation of results.

Table 4.1. Frameworks and references

| Suits research exploring:• Changing behaviours within health contexts to address patient and carer practices• Changing behaviours regarding environmental concerns• Barriers and enablers to behaviour/ practice/ implementation• Intervention planning and implementation• Post-evaluation• Promoting physical activity | This study examined how the COM-B model could be used to increase children’s hand-washing and improve disinfecting surfaces in seven countries. Each country had a different result based on capability, opportunity and/or motivation. This study examined the barriers and facilitators to talking about death and dying among the general population in Northern Ireland. The findings were mapped across the COM-B behaviour change model and the theoretical domains framework. This study explored women’s understanding of health and health behaviours and the supports that were important to promote behavioural change in the preconception period. Coding took place and a deductive process identified themes mapped to the COM-B framework. Identified perceived barriers and enablers of the implementation of a falls-prevention program to inform the implementation in a randomised controlled trial. Strategies to optimise the successful implementation of the program were also sought. Results were mapped against the COM-B framework. | ||

| Great for:• Evaluation• Intervention and implementation planning | Explored participants’ experiences with the program (ceasing smoking) to inform future implementation efforts of combined smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence interventions, guided by the CFIR. Key findings from the interviews are presented in relation to overarching CFIR domains. This mixed-methods study drew upon the CFIR combined with the concept of ‘intervention fidelity’ to evaluate the quality of the interprofessional counselling sessions, to explore the perspective of, directly and indirectly, involved healthcare staff, as well as to analyse the perceptions and experiences of the patients. This is a protocol for a scoping study to identify the topics in need of study and areas for future research on barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of workplace health-promoting interventions. Data analysis was aligned to the CFIR. This study examined the utility of the CFIR in identifying and comparing barriers and facilitators influencing the implementation of participatory research trials, by employing an adaptation of the CFIR to assess the implementation of a multi-component, urban public school-based participatory health intervention. Adapted CFIR constructs guided the largely deductive approach to thematic data analysis. | ||

| Good for:• Pre-implementation, implementation and post-implementation studies• Feasibility studies• Intervention development | This study aimed to develop and assess the psychometric properties of a measurement scale for acceptance of a telephone-facilitated health coaching intervention, based on the TFA; and to determine the acceptability of the intervention among participants living with diabetes or having a high risk of diabetes in socio-economically disadvantaged areas in Stockholm. A questionnaire using TFA was employed. This paper reported patients’ perceived acceptability of the use of PINCER in primary care and proposes suggestions on how delivery of PINCER-related care could be delivered in a way that is acceptable and not unnecessarily burdensome.This study describes the nationwide implementation of a program targeting physical activity and sedentary behaviour in vocational schools (Lets’s Move It; LMI). Results showed high levels of acceptability and reach of training. This study drew on established models such TFA to assess the acceptability of SmartNet in Ugandan households. Results showed the monitor needs to continue to be optimised to make it more acceptable to users and to accurately reflect standard insecticide-treated nets use to improve understanding of prevention behaviours in malaria-endemic settings. | ||

| Good for:• Implementation• Evaluation | This pre-implementation evaluation of an integrated, shared decision-making personal health record system (e-PHR) was underpinned by NPT. The theory provides a framework to analyse cognitive and behavioural mechanisms known to influence implementation success. It was extremely valuable for informing the future implementation of e-PHR, including perceived benefits and barriers. This study assessed the impact of an intervention combining health literacy colorectal cancer-screening (CRC) training for GPs, using a pictorial brochure and video targeting eligible patients, to increase screening and other secondary outcomes, after 1 year, in several underserved geographic areas in France. They propose to evaluate health literacy among underserved populations to address health inequalities and improve CRC screening uptake and other outcomes. This study aimed to ascertain acceptability among pregnant smokers receiving the intervention. Interview schedules were informed by NPT and theoretical domains framework; interviews were analysed thematically, using the framework method and NPT. Findings are grouped according to the four NPT concepts. The study sought to understand how the implementation of primary care services for transgender individuals compares across various models of primary care delivery in Ontario, Canada. Using the NPT framework to guide analysis, key themes emerged about the successful implementation of primary care services for transgender individuals. | ||

| Good for:• Patient experiences• Evaluation of health services• Evaluation | The study used the candidacy framework to explore how the doctor–patient relationship can influence perceived eligibility to visit their GP among people experiencing cancer alarm symptoms. A valuable theoretical framework for understanding the interactional factors of the doctor–patient relationship which influence perceived eligibility to seek help for possible cancer alarm symptoms.The study aimed to understand ways in which a mHealth intervention could be developed to overcome barriers to existing HIV testing and care services and promote HIV self-testing and linkage to prevention and care in a poor, HIV hyperendemic community in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Themes were identified from the interview transcripts, manually coded, and thematically analysed informed by the candidacy framework.This study explored the perceived problems of non-engagement that outreach aims to address and specific mechanisms of outreach hypothesised to tackle these. Analysis was thematically guided by the concept of 'candidacy', which theorises the dynamic process through which services and individuals negotiate appropriate service use.This was a theoretically informed examination of experiences of access to secondary mental health services during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in England. Findings affirm the value of the construct of candidacy for explaining access to mental health care, but also enable deepened understanding of the specific features of candidacy. | ||

| Good for:• Examining how social injustice affects health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from a non-medical model• Examining how inequalities in illness and mortality rates result from personal context within communities characterised by social, economic and political inequality, factors | Culture had a strong presence in program delivery and building social cohesion, and social capital emerged as themes. As a primary health care provider, the ACCHO sector addresses the social determinants of health and health inequity experienced by Indigenous communities. The community-controlled service increased their breadth of strategies used to address primary health care indicates the need for greater understanding of the benefits of this model, as well as advocacy to safeguard it from measures that may undermine its equity performance.The primary health care delivered by ACCHOs is culturally appropriate because they are incorporated Aboriginal organisations, initiated by local Aboriginal communities and based in local Aboriginal communities, governed by Aboriginal bodies elected by the local Aboriginal community, delivering a holistic and culturally appropriate health service to the community that controls it. After investigation, the authors state that failure to recognise the intersection of culture with other structural and societal factors creates and compounds poor health outcomes, thereby multiplying financial, intellectual and humanitarian cost. They review health and health practices as they relate to culture. | ||

| Good for:• Understanding the non-medical factors that influence health and social outcomes | The study identifies and describes the social determinants of health.This study examines a socio-ecological approach to healthy eating and active living, a model of health that recognises the interaction between individuals and their greater environment and its impact on health.The study considers the healthcare screening and referral of families to resources that are critical roles for pediatric healthcare practices to consider as part of addressing social determinants of health.This study examines how (apart from age) social and economic factors contribute to disability differences between older men and women. | ||

| Good for: • Examining all the factors that contribute to health, such as social, cultural, political and environmental factors | Participants provided narratives of the pictures, using pre-identified themes and the different levels of the social-ecological model.The study tested a socioecological model of the determinants of health literacy with a special focus on geographical differences in Europe.This study investigated the interaction of family support, transport cost (ex-post) and disabilities on health service-seeking behaviour among older people, from the perspective of the social ecological model. The study examined the factors that contributed to low birth weight in babies, including age, gestational age, birth spacing, age at marriage, history of having a low birth weight infant, miscarriage and stillbirth, mean weight before pregnancy, body mass index, hemoglobin and hematocrit, educational level, family size, number of pregnancies, husband’s support during pregnancy and husband’s occupation. | ||

| Good for: • Using a new way of thinking to understand the whole rather than individual parts | The study outlines a systems theory of mental health care and promotion that is specific to needs of the recreational sport system, so that context-specific, effective policies, interventions and models of care can be articulated and tested.This study uses a systems-thinking approach to consider the person–environment transaction and to focus on the underlying processes and patterns of human behaviour of flight attendants.The study examines the family as a system and proposes that family systems theory is a formal theory that can be used to guide family practice and research.The authors examine the meta-theoretical, theoretical and methodological foundations of the literature base of hope. They examine the intersection of positive psychology with systems thinking. | ||

| Good for:• Understanding the many factors that affect health, including biological, psychological and social factors | The biopsychosocial model was used to guide the entire research study: background, question, tools and analysis.The biopsychosocial model was used to guide the researchers’ understanding of ‘health’ and the many factors that affect it, including the wider determinants of health in the discussion.The biopsychosocial model is not specifically mentioned; however, factors such as depression, age, social support, income, co-morbidities including diabetes and hypertension, and sex were measured and analysed.The study uses the Survey of Unmet Needs for data collection, which determines needs across impairment, activities of daily living, occupational activities, psychological needs, and community access. Data was analysed across the full spectrum of needs. |

As discussed in Chapter 3, qualitative research is not an absolute science. While not all research may need a framework or theory (particularly descriptive studies, outlined in Chapter 5), the use of a framework or theory can help to position the research questions, research processes and conclusions and implications within the relevant research paradigm. Theories and frameworks also help to bring to focus areas of the research problem that may not have been considered.

- Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med . 2020;95(7):989-994. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci . 2011;6:42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- CFIR Research Team. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Center for Clinical Management Research. 2023. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://cfirguide.org/

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res . 2017;17:88. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

- Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med . 2010;8:63. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-63

- Tookey S, Renzi C, Waller J, von Wagner C, Whitaker KL. Using the candidacy framework to understand how doctor-patient interactions influence perceived eligibility to seek help for cancer alarm symptoms: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv Res . 2018;18(1):937. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3730-5

- Lyon P. Aboriginal Health in Aboriginal Hands: Community-Controlled Comprehensive Primary Health Care @ Central Australian Aboriginal Congress; 2016. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://nacchocommunique.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/cphc-congress-final-report.pdf

- Solar O., Irwin A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice); 2010. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852

- Yuill C, Crinson I, Duncan E. Key Concepts in Health Studies . SAGE Publications; 2010.

- Germov J. Imagining health problems as social issues. In: Germov J, ed. Second Opinion: An Introduction to Health Sociology . Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Laszlo A, Krippner S. Systems theories: their origins, foundations, and development. In: Jordan JS, ed. Advances in Psychology . Science Direct; 1998:47-74.

- Engel GL. From biomedical to biopsychosocial: being scientific in the human domain. Psychosomatics . 1997;38(6):521-528. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71396-3

- Schmidtke KA, Drinkwater KG. A cross-sectional survey assessing the influence of theoretically informed behavioural factors on hand hygiene across seven countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1432. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11491-4

- Graham-Wisener L, Nelson A, Byrne A, et al. Understanding public attitudes to death talk and advance care planning in Northern Ireland using health behaviour change theory: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:906. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13319-1

- Walker R, Quong S, Olivier P, Wu L, Xie J, Boyle J. Empowerment for behaviour change through social connections: a qualitative exploration of women’s preferences in preconception health promotion in the state of Victoria, Australia. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1642. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-14028-5

- Ayton DR, Barker AL, Morello RT, et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of the 6-PACK falls prevention program: a pre-implementation study in hospitals participating in a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE . 2017;12(2):e0171932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171932

- Pratt R, Xiong S, Kmiecik A, et al. The implementation of a smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence intervention for people experiencing homelessness. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1260. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13563-5

- Bossert J, Mahler C, Boltenhagen U, et al. Protocol for the process evaluation of a counselling intervention designed to educate cancer patients on complementary and integrative health care and promote interprofessional collaboration in this area (the CCC-Integrativ study). PLOS ONE . 2022;17(5):e0268091. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268091

- Lwin KS, Bhandari AKC, Nguyen PT, et al. Factors influencing implementation of health-promoting interventions at workplaces: protocol for a scoping review. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275887. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275887

- Wilhelm AK, Schwedhelm M, Bigelow M, et al. Evaluation of a school-based participatory intervention to improve school environments using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1615. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11644-5

- Timm L, Annerstedt KS, Ahlgren JÁ, et al. Application of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability to assess a telephone-facilitated health coaching intervention for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275576. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275576

- Laing L, Salema N-E, Jeffries M, et al. Understanding factors that could influence patient acceptability of the use of the PINCER intervention in primary care: a qualitative exploration using the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275633

- Renko E, Knittle K, Palsola M, Lintunen T, Hankonen N. Acceptability, reach and implementation of a training to enhance teachers’ skills in physical activity promotion. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1568. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09653-x

- Alexander SM, Agaba A, Campbell JI, et al. A qualitative study of the acceptability of remote electronic bednet use monitoring in Uganda. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1010. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13393

- May C, Rapley T, Mair FS, et al. Normalization Process Theory On-line Users’ Manual, Toolkit and NoMAD instrument. 2015. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://normalization-process-theory.northumbria.ac.uk/

- Davis S. Ready for prime time? Using Normalization Process Theory to evaluate implementation success of personal health records designed for decision making. Front Digit Health . 2020;2:575951. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2020.575951

- Durand M-A, Lamouroux A, Redmond NM, et al. Impact of a health literacy intervention combining general practitioner training and a consumer facing intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in underserved areas: protocol for a multicentric cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1684. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11565

- Jones SE, Hamilton S, Bell R, Araújo-Soares V, White M. Acceptability of a cessation intervention for pregnant smokers: a qualitative study guided by Normalization Process Theory. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1512. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09608-2

- Ziegler E, Valaitis R, Yost J, Carter N, Risdon C. “Primary care is primary care”: use of Normalization Process Theory to explore the implementation of primary care services for transgender individuals in Ontario. PLOS ONE . 2019;14(4):e0215873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215873

- Mackenzie M, Conway E, Hastings A, Munro M, O’Donnell C. Is ‘candidacy’ a useful concept for understanding journeys through public services? A critical interpretive literature synthesis. Soc Policy Adm . 2013;47(7):806-825. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00864.x

- Adeagbo O, Herbst C, Blandford A, et al. Exploring people’s candidacy for mobile health–supported HIV testing and care services in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res . 2019;21(11):e15681. doi:10.2196/15681

- Mackenzie M, Turner F, Platt S, et al. What is the ‘problem’ that outreach work seeks to address and how might it be tackled? Seeking theory in a primary health prevention programme. BMC Health Serv Res . 2011;11:350. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-350

- Liberati E, Richards N, Parker J, et al. Qualitative study of candidacy and access to secondary mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Med. 2022;296:114711. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114711

- Pearson O, Schwartzkopff K, Dawson A, et al. Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1859. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09943-4

- Freeman T, Baum F, Lawless A, et al. Revisiting the ability of Australian primary healthcare services to respond to health inequity. Aust J Prim Health . 2016;22(4):332-338. doi:10.1071/PY14180

- Couzos S. Towards a National Primary Health Care Strategy: Fulfilling Aboriginal Peoples Aspirations to Close the Gap . National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. 2009. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/35080/

- Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, et al. Culture and health. Lancet . 2014;384(9954):1607-1639. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61603-2

- WHO. COVID-19 and the Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity: Evidence Brief . 2021. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038387

- WHO. Social Determinants of Health . 2023. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- McCrae JS, Robinson JAL, Spain AK, Byers K, Axelrod JL. The Mitigating Toxic Stress study design: approaches to developmental evaluation of pediatric health care innovations addressing social determinants of health and toxic stress. BMC Health Serv Res . 2021;21:71. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06057-4

- Hosseinpoor AR, Stewart Williams J, Jann B, et al. Social determinants of sex differences in disability among older adults: a multi-country decomposition analysis using the World Health Survey. Int J Equity Health . 2012;11:52. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-52

- Kabore A, Afriyie-Gyawu E, Awua J, et al. Social ecological factors affecting substance abuse in Ghana (West Africa) using photovoice. Pan Afr Med J . 2019;34:214. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.34.214.12851

- Bíró É, Vincze F, Mátyás G, Kósa K. Recursive path model for health literacy: the effect of social support and geographical residence. Front Public Health . 2021;9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.724995

- Yuan B, Zhang T, Li J. Family support and transport cost: understanding health service among older people from the perspective of social-ecological model. Arch Public Health . 2022;80:173. doi:10.1186/s13690-022-00923-1

- Mahmoodi Z, Karimlou M, Sajjadi H, Dejman M, Vameghi M, Dolatian M. A communicative model of mothers’ lifestyles during pregnancy with low birth weight based on social determinants of health: a path analysis. Oman Med J . 2017 ;32(4):306-314. doi:10.5001/omj.2017.59

- Vella SA, Schweickle MJ, Sutcliffe J, Liddelow C, Swann C. A systems theory of mental health in recreational sport. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2022;19(21):14244. doi:10.3390/ijerph192114244

- Henning S. The wellness of airline cabin attendants: A systems theory perspective. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure . 2015;4(1):1-11. Accessed February 15, 2023. http://www.ajhtl.com/archive.html

- Sutphin ST, McDonough S, Schrenkel A. The role of formal theory in social work research: formalizing family systems theory. Adv Soc Work . 2013;14(2):501-517. doi:10.18060/7942

- Colla R, Williams P, Oades LG, Camacho-Morles J. “A new hope” for positive psychology: a dynamic systems reconceptualization of hope theory. Front Psychol . 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809053

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136. doi:10.1126/science.847460

- Wade DT, HalliganPW. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabi l. 2017;31(8):995–1004. doi:10.1177/0269215517709890

- Ip L, Smith A, Papachristou I, Tolani E. 3 Dimensions for Long Term Conditions – creating a sustainable bio-psycho-social approach to healthcare. J Integr Care . 2019;19(4):5. doi:10.5334/ijic.s3005

- FrameWorks Institute. A Matter of Life and Death: Explaining the Wider Determinants of Health in the UK . FrameWorks Institute; 2022. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FWI-30-uk-health-brief-v3a.pdf

- Zemed A, Nigussie Chala K, Azeze Eriku G, Yalew Aschalew A. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among patients with stroke at tertiary level hospitals in Ethiopia. PLOS ONE . 2021;16(3):e0248481. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248481

- Finch E, Foster M, Cruwys T, et al. Meeting unmet needs following minor stroke: the SUN randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Health Serv Res . 2019;19:894. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4746-1

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Tess Tsindos is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

Nicola k gale, gemma heath, elaine cameron, sabina rashid, sabi redwood.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2012 Dec 17; Accepted 2013 Sep 6; Collection date 2013.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The Framework Method is becoming an increasingly popular approach to the management and analysis of qualitative data in health research. However, there is confusion about its potential application and limitations.

The article discusses when it is appropriate to adopt the Framework Method and explains the procedure for using it in multi-disciplinary health research teams, or those that involve clinicians, patients and lay people. The stages of the method are illustrated using examples from a published study.

Used effectively, with the leadership of an experienced qualitative researcher, the Framework Method is a systematic and flexible approach to analysing qualitative data and is appropriate for use in research teams even where not all members have previous experience of conducting qualitative research.

Keywords: Qualitative research, Qualitative content analysis, Multi-disciplinary research

The Framework Method for the management and analysis of qualitative data has been used since the 1980s [ 1 ]. The method originated in large-scale social policy research but is becoming an increasingly popular approach in medical and health research; however, there is some confusion about its potential application and limitations. In this article we discuss when it is appropriate to use the Framework Method and how it compares to other qualitative analysis methods. In particular, we explore how it can be used in multi-disciplinary health research teams. Multi-disciplinary and mixed methods studies are becoming increasingly commonplace in applied health research. As well as disciplines familiar with qualitative research, such as nursing, psychology and sociology, teams often include epidemiologists, health economists, management scientists and others. Furthermore, applied health research often has clinical representation and, increasingly, patient and public involvement [ 2 ]. We argue that while leadership is undoubtedly required from an experienced qualitative methodologist, non-specialists from the wider team can and should be involved in the analysis process. We then present a step-by-step guide to the application of the Framework Method, illustrated using a worked example (See Additional File 1 ) from a published study [ 3 ] to illustrate the main stages of the process. Technical terms are included in the glossary (below). Finally, we discuss the strengths and limitations of the approach.

Glossary of key terms used in the Framework Method

Analytical framework: A set of codes organised into categories that have been jointly developed by researchers involved in analysis that can be used to manage and organise the data. The framework creates a new structure for the data (rather than the full original accounts given by participants) that is helpful to summarize/reduce the data in a way that can support answering the research questions.

Analytic memo: A written investigation of a particular concept, theme or problem, reflecting on emerging issues in the data that captures the analytic process (see Additional file 1 , Section 7).

Categories: During the analysis process, codes are grouped into clusters around similar and interrelated ideas or concepts. Categories and codes are usually arranged in a tree diagram structure in the analytical framework. While categories are closely and explicitly linked to the raw data, developing categories is a way to start the process of abstraction of the data (i.e. towards the general rather than the specific or anecdotal).

Charting: Entering summarized data into the Framework Method matrix (see Additional File 1 , Section 6).

Code: A descriptive or conceptual label that is assigned to excerpts of raw data in a process called ‘coding’ (see Additional File 1 , Section 3).

Data: Qualitative data usually needs to be in textual form before analysis. These texts can either be elicited texts (written specifically for the research, such as food diaries), or extant texts (pre-existing texts, such as meeting minutes, policy documents or weblogs), or can be produced by transcribing interview or focus group data, or creating ‘field’ notes while conducting participant-observation or observing objects or social situations.

Indexing: The systematic application of codes from the agreed analytical framework to the whole dataset (see Additional File 1 , Section 5).

Matrix: A spreadsheet contains numerous cells into which summarized data are entered by codes (columns) and cases (rows) (see Additional File 1 , Section 6).

Themes: Interpretive concepts or propositions that describe or explain aspects of the data, which are the final output of the analysis of the whole dataset. Themes are articulated and developed by interrogating data categories through comparison between and within cases. Usually a number of categories would fall under each theme or sub-theme [ 3 ].

Transcript: A written verbatim (word-for-word) account of a verbal interaction, such as an interview or conversation.

The Framework Method sits within a broad family of analysis methods often termed thematic analysis or qualitative content analysis. These approaches identify commonalities and differences in qualitative data, before focusing on relationships between different parts of the data, thereby seeking to draw descriptive and/or explanatory conclusions clustered around themes. The Framework Method was developed by researchers, Jane Ritchie and Liz Spencer, from the Qualitative Research Unit at the National Centre for Social Research in the United Kingdom in the late 1980s for use in large-scale policy research [ 1 ]. It is now used widely in other areas, including health research [ 3 - 12 ]. Its defining feature is the matrix output: rows (cases), columns (codes) and ‘cells’ of summarised data, providing a structure into which the researcher can systematically reduce the data, in order to analyse it by case and by code [ 1 ]. Most often a ‘case’ is an individual interviewee, but this can be adapted to other units of analysis, such as predefined groups or organisations. While in-depth analyses of key themes can take place across the whole data set, the views of each research participant remain connected to other aspects of their account within the matrix so that the context of the individual’s views is not lost. Comparing and contrasting data is vital to qualitative analysis and the ability to compare with ease data across cases as well as within individual cases is built into the structure and process of the Framework Method.

The Framework Method provides clear steps to follow and produces highly structured outputs of summarised data. It is therefore useful where multiple researchers are working on a project, particularly in multi-disciplinary research teams were not all members have experience of qualitative data analysis, and for managing large data sets where obtaining a holistic, descriptive overview of the entire data set is desirable. However, caution is recommended before selecting the method as it is not a suitable tool for analysing all types of qualitative data or for answering all qualitative research questions, nor is it an ‘easy’ version of qualitative research for quantitative researchers. Importantly, the Framework Method cannot accommodate highly heterogeneous data, i.e. data must cover similar topics or key issues so that it is possible to categorize it. Individual interviewees may, of course, have very different views or experiences in relation to each topic, which can then be compared and contrasted. The Framework Method is most commonly used for the thematic analysis of semi-structured interview transcripts, which is what we focus on in this article, although it could, in principle, be adapted for other types of textual data [ 13 ], including documents, such as meeting minutes or diaries [ 12 ], or field notes from observations [ 10 ].

For quantitative researchers working with qualitative colleagues or when exploring qualitative research for the first time, the nature of the Framework Method is seductive because its methodical processes and ‘spreadsheet’ approach seem more closely aligned to the quantitative paradigm [ 14 ]. Although the Framework Method is a highly systematic method of categorizing and organizing what may seem like unwieldy qualitative data, it is not a panacea for problematic issues commonly associated with qualitative data analysis such as how to make analytic choices and make interpretive strategies visible and auditable. Qualitative research skills are required to appropriately interpret the matrix, and facilitate the generation of descriptions, categories, explanations and typologies. Moreover, reflexivity, rigour and quality are issues that are requisite in the Framework Method just as they are in other qualitative methods. It is therefore essential that studies using the Framework Method for analysis are overseen by an experienced qualitative researcher, though this does not preclude those new to qualitative research from contributing to the analysis as part of a wider research team.

There are a number of approaches to qualitative data analysis, including those that pay close attention to language and how it is being used in social interaction such as discourse analysis [ 15 ] and ethnomethodology [ 16 ]; those that are concerned with experience, meaning and language such as phenomenology [ 17 , 18 ] and narrative methods [ 19 ]; and those that seek to develop theory derived from data through a set of procedures and interconnected stages such as Grounded Theory [ 20 , 21 ]. Many of these approaches are associated with specific disciplines and are underpinned by philosophical ideas which shape the process of analysis [ 22 ]. The Framework Method, however, is not aligned with a particular epistemological, philosophical, or theoretical approach. Rather it is a flexible tool that can be adapted for use with many qualitative approaches that aim to generate themes.

The development of themes is a common feature of qualitative data analysis, involving the systematic search for patterns to generate full descriptions capable of shedding light on the phenomenon under investigation. In particular, many qualitative approaches use the ‘constant comparative method’ , developed as part of Grounded Theory, which involves making systematic comparisons across cases to refine each theme [ 21 , 23 ]. Unlike Grounded Theory, the Framework Method is not necessarily concerned with generating social theory, but can greatly facilitate constant comparative techniques through the review of data across the matrix.

Perhaps because the Framework Method is so obviously systematic, it has often, as other commentators have noted, been conflated with a deductive approach to qualitative analysis [ 13 , 14 ]. However, the tool itself has no allegiance to either inductive or deductive thematic analysis; where the research sits along this inductive-deductive continuum depends on the research question. A question such as, ‘Can patients give an accurate biomedical account of the onset of their cardiovascular disease?’ is essentially a yes/no question (although it may be nuanced by the extent of their account or by appropriate use of terminology) and so requires a deductive approach to both data collection and analysis (e.g. structured or semi-structured interviews and directed qualitative content analysis [ 24 ]). Similarly, a deductive approach may be taken if basing analysis on a pre-existing theory, such as behaviour change theories, for example in the case of a research question such as ‘How does the Theory of Planned Behaviour help explain GP prescribing?’ [ 11 ]. However, a research question such as, ‘How do people construct accounts of the onset of their cardiovascular disease?’ would require a more inductive approach that allows for the unexpected, and permits more socially-located responses [ 25 ] from interviewees that may include matters of cultural beliefs, habits of food preparation, concepts of ‘fate’, or links to other important events in their lives, such as grief, which cannot be predicted by the researcher in advance (e.g. an interviewee-led open ended interview and grounded theory [ 20 ]). In all these cases, it may be appropriate to use the Framework Method to manage the data. The difference would become apparent in how themes are selected: in the deductive approach, themes and codes are pre-selected based on previous literature, previous theories or the specifics of the research question; whereas in the inductive approach, themes are generated from the data though open (unrestricted) coding, followed by refinement of themes. In many cases, a combined approach is appropriate when the project has some specific issues to explore, but also aims to leave space to discover other unexpected aspects of the participants’ experience or the way they assign meaning to phenomena. In sum, the Framework Method can be adapted for use with deductive, inductive, or combined types of qualitative analysis. However, there are some research questions where analysing data by case and theme is not appropriate and so the Framework Method should be avoided. For instance, depending on the research question, life history data might be better analysed using narrative analysis [ 19 ]; recorded consultations between patients and their healthcare practitioners using conversation analysis [ 26 ]; and documentary data, such as resources for pregnant women, using discourse analysis [ 27 ].

It is not within the scope of this paper to consider study design or data collection in any depth, but before moving on to describe the Framework Method analysis process, it is worth taking a step back to consider briefly what needs to happen before analysis begins. The selection of analysis method should have been considered at the proposal stage of the research and should fit with the research questions and overall aims of the study. Many qualitative studies, particularly ones using inductive analysis, are emergent in nature; this can be a challenge and the researchers can only provide an “imaginative rehearsal” of what is to come [ 28 ]. In mixed methods studies, the role of the qualitative component within the wider goals of the project must also be considered. In the data collection stage, resources must be allocated for properly trained researchers to conduct the qualitative interviewing because it is a highly skilled activity. In some cases, a research team may decide that they would like to use lay people, patients or peers to do the interviews [ 29 - 32 ] and in this case they must be properly trained and mentored which requires time and resources. At this early stage it is also useful to consider whether the team will use Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS), which can assist with data management and analysis.

As any form of qualitative or quantitative analysis is not a purely technical process, but influenced by the characteristics of the researchers and their disciplinary paradigms, critical reflection throughout the research process is paramount, including in the design of the study, the construction or collection of data, and the analysis. All members of the team should keep a research diary, where they record reflexive notes, impressions of the data and thoughts about analysis throughout the process. Experienced qualitative researchers become more skilled at sifting through data and analysing it in a rigorous and reflexive way. They cannot be too attached to certainty, but must remain flexible and adaptive throughout the research in order to generate rich and nuanced findings that embrace and explain the complexity of real social life and can be applied to complex social issues. It is important to remember when using the Framework Method that, unlike quantitative research where data collection and data analysis are strictly sequential and mutually exclusive stages of the research process, in qualitative analysis there is, to a greater or lesser extent depending on the project, ongoing interplay between data collection, analysis, and theory development. For example, new ideas or insights from participants may suggest potentially fruitful lines of enquiry, or close analysis might reveal subtle inconsistencies in an account which require further exploration.

Procedure for analysis

Stage 1: transcription.

A good quality audio recording and, ideally, a verbatim (word for word) transcription of the interview is needed. For Framework Method analysis, it is not necessarily important to include the conventions of dialogue transcriptions which can be difficult to read (e.g. pauses or two people talking simultaneously), because the content is what is of primary interest. Transcripts should have large margins and adequate line spacing for later coding and making notes. The process of transcription is a good opportunity to become immersed in the data and is to be strongly encouraged for new researchers. However, in some projects, the decision may be made that it is a better use of resources to outsource this task to a professional transcriber.

Stage 2: Familiarisation with the interview

Becoming familiar with the whole interview using the audio recording and/or transcript and any contextual or reflective notes that were recorded by the interviewer is a vital stage in interpretation. It can also be helpful to re-listen to all or parts of the audio recording. In multi-disciplinary or large research projects, those involved in analysing the data may be different from those who conducted or transcribed the interviews, which makes this stage particularly important. One margin can be used to record any analytical notes, thoughts or impressions.

Stage 3: Coding

After familiarization, the researcher carefully reads the transcript line by line, applying a paraphrase or label (a ‘code’) that describes what they have interpreted in the passage as important. In more inductive studies, at this stage ‘open coding’ takes place, i.e. coding anything that might be relevant from as many different perspectives as possible. Codes could refer to substantive things (e.g. particular behaviours, incidents or structures), values (e.g. those that inform or underpin certain statements, such as a belief in evidence-based medicine or in patient choice), emotions (e.g. sorrow, frustration, love) and more impressionistic/methodological elements (e.g. interviewee found something difficult to explain, interviewee became emotional, interviewer felt uncomfortable) [ 33 ]. In purely deductive studies, the codes may have been pre-defined (e.g. by an existing theory, or specific areas of interest to the project) so this stage may not be strictly necessary and you could just move straight onto indexing, although it is generally helpful even if you are taking a broadly deductive approach to do some open coding on at least a few of the transcripts to ensure important aspects of the data are not missed. Coding aims to classify all of the data so that it can be compared systematically with other parts of the data set. At least two researchers (or at least one from each discipline or speciality in a multi-disciplinary research team) should independently code the first few transcripts, if feasible. Patients, public involvement representatives or clinicians can also be productively involved at this stage, because they can offer alternative viewpoints thus ensuring that one particular perspective does not dominate. It is vital in inductive coding to look out for the unexpected and not to just code in a literal, descriptive way so the involvement of people from different perspectives can aid greatly in this. As well as getting a holistic impression of what was said, coding line-by-line can often alert the researcher to consider that which may ordinarily remain invisible because it is not clearly expressed or does not ‘fit’ with the rest of the account. In this way the developing analysis is challenged; to reconcile and explain anomalies in the data can make the analysis stronger. Coding can also be done digitally using CAQDAS, which is a useful way to keep track automatically of new codes. However, some researchers prefer to do the early stages of coding with a paper and pen, and only start to use CAQDAS once they reach Stage 5 (see below).

Stage 4: Developing a working analytical framework

After coding the first few transcripts, all researchers involved should meet to compare the labels they have applied and agree on a set of codes to apply to all subsequent transcripts. Codes can be grouped together into categories (using a tree diagram if helpful), which are then clearly defined. This forms a working analytical framework. It is likely that several iterations of the analytical framework will be required before no additional codes emerge. It is always worth having an ‘other’ code under each category to avoid ignoring data that does not fit; the analytical framework is never ‘final’ until the last transcript has been coded.

Stage 5: Applying the analytical framework

The working analytical framework is then applied by indexing subsequent transcripts using the existing categories and codes. Each code is usually assigned a number or abbreviation for easy identification (and so the full names of the codes do not have to be written out each time) and written directly onto the transcripts. Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) is particularly useful at this stage because it can speed up the process and ensures that, at later stages, data is easily retrievable. It is worth noting that unlike software for statistical analyses, which actually carries out the calculations with the correct instruction, putting the data into a qualitative analysis software package does not analyse the data; it is simply an effective way of storing and organising the data so that they are accessible for the analysis process.

Stage 6: Charting data into the framework matrix

Qualitative data are voluminous (an hour of interview can generate 15–30 pages of text) and being able to manage and summarize (reduce) data is a vital aspect of the analysis process. A spreadsheet is used to generate a matrix and the data are ‘charted’ into the matrix. Charting involves summarizing the data by category from each transcript. Good charting requires an ability to strike a balance between reducing the data on the one hand and retaining the original meanings and ‘feel’ of the interviewees’ words on the other. The chart should include references to interesting or illustrative quotations. These can be tagged automatically if you are using CAQDAS to manage your data (N-Vivo version 9 onwards has the capability to generate framework matrices), or otherwise a capital ‘Q’, an (anonymized) transcript number, page and line reference will suffice. It is helpful in multi-disciplinary teams to compare and contrast styles of summarizing in the early stages of the analysis process to ensure consistency within the team. Any abbreviations used should be agreed by the team. Once members of the team are familiar with the analytical framework and well practised at coding and charting, on average, it will take about half a day per hour-long transcript to reach this stage. In the early stages, it takes much longer.

Stage 7: Interpreting the data

It is useful throughout the research to have a separate note book or computer file to note down impressions, ideas and early interpretations of the data. It may be worth breaking off at any stage to explore an interesting idea, concept or potential theme by writing an analytic memo [ 20 , 21 ] to then discuss with other members of the research team, including lay and clinical members. Gradually, characteristics of and differences between the data are identified, perhaps generating typologies, interrogating theoretical concepts (either prior concepts or ones emerging from the data) or mapping connections between categories to explore relationships and/or causality. If the data are rich enough, the findings generated through this process can go beyond description of particular cases to explanation of, for example, reasons for the emergence of a phenomena, predicting how an organisation or other social actor is likely to instigate or respond to a situation, or identifying areas that are not functioning well within an organisation or system. It is worth noting that this stage often takes longer than anticipated and that any project plan should ensure that sufficient time is allocated to meetings and individual researcher time to conduct interpretation and writing up of findings (see Additional file 1 , Section 7).

The Framework Method has been developed and used successfully in research for over 25 years, and has recently become a popular analysis method in qualitative health research. The issue of how to assess quality in qualitative research has been highly debated [ 20 , 34 - 40 ], but ensuring rigour and transparency in analysis is a vital component. There are, of course, many ways to do this but in the Framework Method the following are helpful:

•Summarizing the data during charting, as well as being a practical way to reduce the data, means that all members of a multi-disciplinary team, including lay, clinical and (quantitative) academic members can engage with the data and offer their perspectives during the analysis process without necessarily needing to read all the transcripts or be involved in the more technical parts of analysis.

•Charting also ensures that researchers pay close attention to describing the data using each participant’s own subjective frames and expressions in the first instance, before moving onto interpretation.

•The summarized data is kept within the wider context of each case, thereby encouraging thick description that pays attention to complex layers of meaning and understanding [ 38 ].

•The matrix structure is visually straightforward and can facilitate recognition of patterns in the data by any member of the research team, including through drawing attention to contradictory data, deviant cases or empty cells.

•The systematic procedure (described in this article) makes it easy to follow, even for multi-disciplinary teams and/or with large data sets.

•It is flexible enough that non-interview data (such as field notes taken during the interview or reflexive considerations) can be included in the matrix.

•It is not aligned with a particular epistemological viewpoint or theoretical approach and therefore can be adapted for use in inductive or deductive analysis or a combination of the two (e.g. using pre-existing theoretical constructs deductively, then revising the theory with inductive aspects; or using an inductive approach to identify themes in the data, before returning to the literature and using theories deductively to help further explain certain themes).

•It is easy to identify relevant data extracts to illustrate themes and to check whether there is sufficient evidence for a proposed theme.

•Finally, there is a clear audit trail from original raw data to final themes, including the illustrative quotes.

There are also a number of potential pitfalls to this approach:

•The systematic approach and matrix format, as we noted in the background, is intuitively appealing to those trained quantitatively but the ‘spreadsheet’ look perhaps further increases the temptation for those without an in-depth understanding of qualitative research to attempt to quantify qualitative data (e.g. “13 out of 20 participants said X). This kind of statement is clearly meaningless because the sampling in qualitative research is not designed to be representative of a wider population, but purposive to capture diversity around a phenomenon [ 41 ].

•Like all qualitative analysis methods, the Framework Method is time consuming and resource-intensive. When involving multiple stakeholders and disciplines in the analysis and interpretation of the data, as is good practice in applied health research, the time needed is extended. This time needs to be factored into the project proposal at the pre-funding stage.

•There is a high training component to successfully using the method in a new multi-disciplinary team. Depending on their role in the analysis, members of the research team may have to learn how to code, index, and chart data, to think reflexively about how their identities and experience affect the analysis process, and/or they may have to learn about the methods of generalisation (i.e. analytic generalisation and transferability, rather than statistical generalisation [ 41 ]) to help to interpret legitimately the meaning and significance of the data.

While the Framework Method is amenable to the participation of non-experts in data analysis, it is critical to the successful use of the method that an experienced qualitative researcher leads the project (even if the overall lead for a large mixed methods study is a different person). The qualitative lead would ideally be joined by other researchers with at least some prior training in or experience of qualitative analysis. The responsibilities of the lead qualitative researcher are: to contribute to study design, project timelines and resource planning; to mentor junior qualitative researchers; to train clinical, lay and other (non-qualitative) academics to contribute as appropriate to the analysis process; to facilitate analysis meetings in a way that encourages critical and reflexive engagement with the data and other team members; and finally to lead the write-up of the study.

We have argued that Framework Method studies can be conducted by multi-disciplinary research teams that include, for example, healthcare professionals, psychologists, sociologists, economists, and lay people/service users. The inclusion of so many different perspectives means that decision-making in the analysis process can be very time consuming and resource-intensive. It may require extensive, reflexive and critical dialogue about how the ideas expressed by interviewees and identified in the transcript are related to pre-existing concepts and theories from each discipline, and to the real ‘problems’ in the health system that the project is addressing. This kind of team effort is, however, an excellent forum for driving forward interdisciplinary collaboration, as well as clinical and lay involvement in research, to ensure that ‘the whole is greater than the sum of the parts’, by enhancing the credibility and relevance of the findings.

The Framework Method is appropriate for thematic analysis of textual data, particularly interview transcripts, where it is important to be able to compare and contrast data by themes across many cases, while also situating each perspective in context by retaining the connection to other aspects of each individual’s account. Experienced qualitative researchers should lead and facilitate all aspects of the analysis, although the Framework Method’s systematic approach makes it suitable for involving all members of a multi-disciplinary team. An open, critical and reflexive approach from all team members is essential for rigorous qualitative analysis.

Acceptance of the complexity of real life health systems and the existence of multiple perspectives on health issues is necessary to produce high quality qualitative research. If done well, qualitative studies can shed explanatory and predictive light on important phenomena, relate constructively to quantitative parts of a larger study, and contribute to the improvement of health services and development of health policy. The Framework Method, when selected and implemented appropriately, can be a suitable tool for achieving these aims through producing credible and relevant findings.

•The Framework Method is an excellent tool for supporting thematic (qualitative content) analysis because it provides a systematic model for managing and mapping the data.

•The Framework Method is most suitable for analysis of interview data, where it is desirable to generate themes by making comparisons within and between cases.

•The management of large data sets is facilitated by the Framework Method as its matrix form provides an intuitively structured overview of summarised data.

•The clear, step-by-step process of the Framework Method makes it is suitable for interdisciplinary and collaborative projects.

•The use of the method should be led and facilitated by an experienced qualitative researcher.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in the development of the concept of the article and drafting the article. NG wrote the first draft of the article, GH and EC prepared the text and figures related to the illustrative example, SRa did the literature search to identify if there were any similar articles currently available and contributed to drafting of the article, and SRe contributed to drafting of the article and the illustrative example. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/13/117/prepub

Supplementary Material

Illustrative Example of the use of the Framework Method.

Contributor Information

Nicola K Gale, Email: [email protected].

Gemma Heath, Email: [email protected].

Elaine Cameron, Email: [email protected].

Sabina Rashid, Email: [email protected].

Sabi Redwood, Email: [email protected].

Acknowledgments

All authors were funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Birmingham and Black Country (CLAHRC-BBC) programme. The views in this publication expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

- Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ives J, Damery S, Redwod S. PPI, paradoxes and Plato: who's sailing the ship? J Med Ethics. 2013;39(3):181–185. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100150. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heath G, Cameron E, Cummins C, Greenfield S, Pattison H, Kelly D, Redwood S. Paediatric ‘care closer to home’: stake-holder views and barriers to implementation. Health Place. 2012;18(5):1068–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elkington H, White P, Addington-Hall J, Higgs R, Petternari C. The last year of life of COPD: a qualitative study of symptoms and services. Respir Med. 2004;98(5):439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.11.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murtagh J, Dixey R, Rudolf M. A qualitative investigation into the levers and barriers to weight loss in children: opinions of obese children. Archives Dis Child. 2006;91(11):920–923. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.085712. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barnard M, Webster S, O’Connor W, Jones A, Donmall M. The drug treatment outcomes research study (DTORS): qualitative study. London: Home Office; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ayatollahi H, Bath PA, Goodacre S. Factors influencing the use of IT in the emergency department: a qualitative study. Health Inform J. 2010;16(3):189–200. doi: 10.1177/1460458210377480. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheard L, Prout H, Dowding D, Noble S, Watt I, Maraveyas A, Johnson M. Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in advanced cancer patients: a qualitative study. Palliative Med. 2012;27(2):339–348. doi: 10.1177/0269216312461678. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis J, Wagland R, Tishelman C, Williams ML, Bailey CD, Haines J, Caress A, Lorigan P, Smith JA, Booton R. et al. Considerations in developing and delivering a nonpharmacological intervention for symptom management in lung cancer: the views of patients and informal caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manag (0) 2012;44(6):831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.12.274. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gale N, Sultan H. Telehealth as ‘peace of mind’: embodiment, emotions and the home as the primary health space for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. Health place. 2013;21:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.01.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rashidian A, Eccles MP, Russell I. Falling on stony ground? A qualitative study of implementation of clinical guidelines’ prescribing recommendations in primary care. Health policy. 2008;85(2):148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.07.011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]