- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Slavery in America

By: History.com Editors

Published: April 25, 2024

Millions of enslaved Africans contributed to the establishment of colonies in the Americas and continued laboring in various regions of the Americas after their independence, including the United States. Many consider a significant starting point to slavery in America to be 1619 , when the privateer The White Lion brought 20 enslaved Africans ashore in the British colony of Jamestown , Virginia . The crew had seized the Africans from the Portuguese slave ship São João Bautista. Yet, enslaved Africans had been present in regions such as Florida, that are part of present-day United States nearly one century before.

Throughout the 17th century, European settlers in North America turned to enslaved Africans as a cheaper, more plentiful labor source than Indigenous populations and indentured servants, who were mostly poor Europeans.

Existing estimates establish that Europeans and American slave traders transported nearly 12.5 million enslaved Africans to the Americas. Of this number approximately 10.7 million disembarked alive in the Americas. During the 18th century alone, approximately 6.5 million enslaved persons were transported to the Americas. This forced migration deprived the African continent of some of its healthiest and ablest men and women.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved Africans worked mainly on the tobacco, rice and indigo plantations of the southern Atlantic coast, from the Chesapeake Bay colonies of Maryland and Virginia south to Georgia.

Slavery in Plantations and Cities

In the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved Africans worked mainly on the tobacco, rice and indigo plantations of the southern coast, from the Chesapeake Bay colonies of Maryland and Virginia south to Georgia. Starting 1662, the colony of Virginia and then other English colonies established that the legal status of a slave was inherited through the mother. As a result, the children of enslaved women legally became slaves.

Before the rise of the American Revolution , the first debates to abolish slavery emerged. Black and white abolitionists contributed to the enactment of new legislation gradually abolishing slavery in some northern states such as Vermont and Pennsylvania. However, these laws emancipated only the newly born children of enslaved women.

Did you know? One of the first martyrs to the cause of American patriotism was Crispus Attucks, a former enslaved man who was killed by British soldiers during the Boston Massacre of 1770. Some 5,000 Black soldiers and sailors fought on the American side during the Revolutionary War.

But after the end of the American Revolutionary War , slavery was maintained in the new states. The new U.S. Constitution tacitly acknowledged the institution of slavery, when it determined that three out of every five enslaved people were counted when determining a state's total population for the purposes of taxation and representation in Congress.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, European and American slave merchants purchased enslaved Africans who were transported to the Americas and forced into slavery in the American colonies and exploited to work in the production of crops such as tobacco, wheat, indigo, rice, sugar, and cotton. Enslaved men and women also performed work in northern cities such as Boston and New York, and in southern cities such as Charleston, Richmond, and Baltimore.

By the mid-19th century, America’s westward expansion and the abolition movement provoked a great debate over slavery that would tear the nation apart in the bloody Civil War . Though the Union victory freed the nation’s four million enslaved people, the legacy of slavery continued to influence American history, from the Reconstruction to the civil rights movement that emerged a century after emancipation and beyond.

In the late 18th century, the mechanization of the textile industry in England led to a huge demand for American cotton, a southern crop planted and harvested by enslaved people, but whose production was limited by the difficulty of removing the seeds from raw cotton fibers by hand.

But in 1793, a U.S.-born schoolteacher named Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin , a simple mechanized device that efficiently removed the seeds. His device was widely copied, and within a few years, the South transitioned from the large-scale production of tobacco to that of cotton, a switch that reinforced the region’s dependence on enslaved labor.

Slavery was never widespread in the North as it was in the South, but many northern businessmen grew rich on the slave trade and investments in southern plantations. Although gradual abolition emancipated newborns since the late 18th century, slavery was only abolished in New York in 1827, and in Connecticut in 1848.

Though the U.S. Congress outlawed the African slave trade in 1808, the domestic trade flourished, and the enslaved population in the United States nearly tripled over the next 50 years. By 1860 it had reached nearly 4 million, with more than half living in the cotton-producing states of the South.

Living Conditions of Enslaved People

Enslaved people in the antebellum South constituted about one-third of the southern population. Most lived on large plantations or small farms; many enslavers owned fewer than 50 enslaved people.

Landowners sought to make their enslaved completely dependent on them through a system of restrictive codes. They were usually prohibited from learning to read and write, and their behavior and movement were restricted.

Many enslavers raped women they held in slavery, and rewarded obedient behavior with favors, while rebellious enslaved people were brutally punished. A strict hierarchy among the enslaved (from privileged house workers and skilled artisans down to lowly field hands) helped keep them divided and less likely to organize against their enslavers.

Marriages between enslaved men and women had no legal basis, but many did marry and raise large families. Most owners of enslaved workers encouraged this practice, but nonetheless did not usually hesitate to divide families by sale or removal.

Slave Rebellions

Enslaved people organized r ebellions as early as the 18th century. In 1739, enslaved people led the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina, the largest slave rebellion during the colonial era in North America. Other rebellions followed, including the one led by Gabriel Prosser in Richmond in 1800 and by Denmark Vesey in Charleston in 1822. These uprisings were brutally repressed.

The revolt that most terrified enslavers was that led by Nat Turner in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831. Turner’s group, which eventually numbered as many 50 Black men, murdered some 55 white people in two days before armed resistance from local white people and the arrival of state militia forces overwhelmed them.

Like with previous rebellions, in the aftermath of the Nat Turner’s Rebellion, slave owners feared similar insurrections and southern states further passed legislation prohibiting the movement and assembly of enslaved people.

Abolitionist Movement

As slavery expanded during the second half of the 18th century, a growing abolitionist movement emerged in the North.

From the 1830s to the 1860s, the movement to abolish slavery in America gained strength, led by formerly enslaved people such as Frederick Douglass and white supporters such as William Lloyd Garrison , founder of the radical newspaper The Liberator .

While many abolitionists based their activism on the belief that slaveholding was a sin, others were more inclined to the non-religious “free-labor” argument, which held that slaveholding was regressive, inefficient and made little economic sense.

Black abolitionists and antislavery northerners led meetings and created newspapers. They also had begun helping enslaved people escape from southern plantations to the North via a loose network of safe houses as early as the 1780s. This practice, known as the Underground Railroad , gained real momentum in the 1830s.

Conductors like Harriet Tubman guided escapees on their journey North, and “ stationmasters ” included such prominent figures as Frederick Douglass, Secretary of State William H. Seward and Pennsylvania congressman Thaddeus Stevens. Although no one knows for sure how many men, women, and children escaped slavery through the Underground Railroad, it was in the thousands ( estimates range from 25,000 to 100,000).

The success of the Underground Railroad helped spread abolitionist feelings in the North. It also undoubtedly increased sectional tensions, convincing pro-slavery southerners of their northern countrymen’s determination to defeat the institution that sustained them.

Missouri Compromise

America’s explosive growth—and its expansion westward in the first half of the 19th century—would provide a larger stage for the growing conflict over slavery in America and its future limitation or expansion.

In 1820, a bitter debate over the federal government’s right to restrict slavery over Missouri’s application for statehood ended in a compromise: Missouri was admitted to the Union as a slave state, Maine as a free state and all western territories north of Missouri’s southern border were to be free soil.

Although the Missouri Compromise was designed to maintain an even balance between slave and free states, it was only temporarily able to help quell the forces of sectionalism.

Kansas-Nebraska Act

In 1850, another tenuous compromise was negotiated to resolve the question of slavery in territories won during the Mexican-American War .

Four years later, however, the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened all new territories to slavery by asserting the rule of popular sovereignty over congressional edict, leading pro- and anti-slavery forces to battle it out—with considerable bloodshed —in the new state of Kansas.

Outrage in the North over the Kansas-Nebraska Act spelled the downfall of the old Whig Party and the birth of a new, all-northern Republican Party . In 1857, the Dred Scott decision by the Supreme Court (involving an enslaved man who sued for his freedom on the grounds that his enslaver had taken him into free territory) effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise by ruling that all territories were open to slavery.

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry

In 1859, two years after the Dred Scott decision, an event occurred that would ignite passions nationwide over the issue of slavery.

John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry , Virginia—in which the abolitionist and 22 men, including five Black men and three of Brown’s sons raided and occupied a federal arsenal—resulted in the deaths of 10 people and Brown’s hanging.

The insurrection exposed the growing national rift over slavery: Brown was hailed as a martyred hero by northern abolitionists but was vilified as a mass murderer in the South.

The South would reach the breaking point the following year, when Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected as president. Within three months, seven southern states had seceded to form the Confederate States of America ; four more would follow after the Civil War began.

Though Lincoln’s anti-slavery views were well established, the central Union war aim at first was not to abolish slavery, but to preserve the United States as a nation.

Abolition became a goal only later, due to military necessity, growing anti-slavery sentiment in the North and the self-emancipation of many people who fled enslavement as Union troops swept through the South.

When Did Slavery End?

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued a preliminary emancipation proclamation, and on January 1, 1863, he made it official that “slaves within any State, or designated part of a State…in rebellion,…shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

By freeing some 3 million enslaved people in the rebel states, the Emancipation Proclamation deprived the Confederacy of the bulk of its labor forces and put international public opinion strongly on the Union side.

Though the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t officially end all slavery in America—that would happen with the passage of the 13th Amendment after the Civil War’s end in 1865—some 186,000 Black soldiers would join the Union Army, and about 38,000 lost their lives.

The Legacy of Slavery

The 13th Amendment, adopted on December 18, 1865, officially abolished slavery, but freed Black peoples’ status in the post-war South remained precarious, and significant challenges awaited during the Reconstruction period.

Previously enslaved men and women received the rights of citizenship and the “equal protection” of the Constitution in the 14th Amendment and the right to vote in the 15th Amendment , but these provisions of the Constitution were often ignored or violated, and it was difficult for Black citizens to gain a foothold in the post-war economy thanks to restrictive Black codes and regressive contractual arrangements such as sharecropping .

Despite seeing an unprecedented degree of Black participation in American political life, Reconstruction was ultimately frustrating for African Americans, and the rebirth of white supremacy —including the rise of racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)—had triumphed in the South by 1877.

Almost a century later, resistance to the lingering racism and discrimination in America that began during the slavery era led to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, which achieved the greatest political and social gains for Black Americans since Reconstruction.

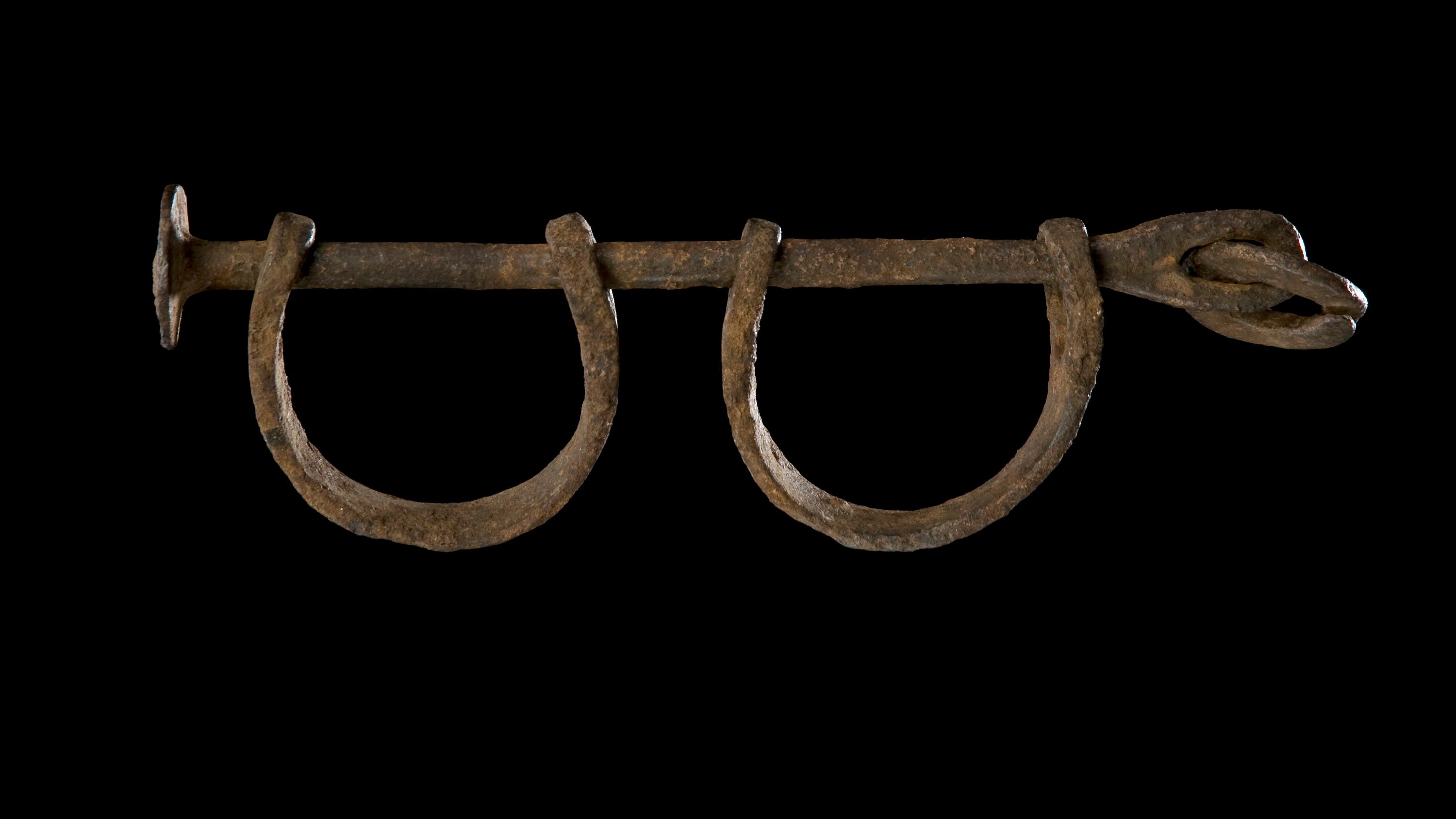

Ana Lucia Araujo , a historian of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade, edited and contributed to this article. Dr. Araujo is currently Professor of History at Howard University in Washington, D.C., and member of the International Scientific Committee of the UNESCO Routes of Enslaved Peoples Projects. Her three more recent books are Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History , The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism , and Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The New York Times

Magazine | the 1619 project, the 1619 project.

AUG. 14, 2019

In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the English colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed. On the 400th anniversary of this fateful moment, it is finally time to tell our story truthfully.

Our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written. black americans have fought to make them true., if you want to understand the brutality of american capitalism, you have to start on the plantation., myths about physical racial differences were used to justify slavery — and are still believed by doctors today., america holds onto an undemocratic assumption from its founding: that some people deserve more power than others., for centuries, black music has been the sound of artistic freedom. no wonder everybody’s always stealing it., ‘i slide my ring finger from senegal to south carolina & feel the ocean separate a million families.’, what does a traffic jam in atlanta have to do with segregation quite a lot., why doesn’t the united states have universal health care the answer begins with policies enacted after the civil war., slavery gave america a fear of black people and a taste for violent punishment. both still define our prison system., the sugar that saturates the american diet has a barbaric history as the ‘white gold’ that fueled slavery., a vast wealth gap, driven by segregation, redlining, evictions and exclusion, separates black and white america., a re-education is necessary., most americans still don’t know the full story of slavery. this is the history you didn’t learn in school., ‘we are committing educational malpractice’: why slavery is mistaught — and worse — in american schools., the 1619 project continues, the 1619 podcast.

An audio series from The Times observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery.

Live at the Smithsonian

Watch highlights of a symposium about how history is defined — and redefined — featuring historians, journalists and policymakers.

Reader Responses

We asked you to share photographs and stories of your enslaved ancestors. The images and stories helped paint a picture of a too-often-erased American history.

We asked you how you learned about slavery in school. You told us about degrading role play, flawed lessons and teachers who played down its horrors.

Race/Related

The 1619 Project was conceived by Nikole Hannah-Jones. In this interview, she talks about the project and the reaction to it.

In the N.B.A., the very term “owner” has come under fire, as players, most of whom are black, assert self-determination.

Behind the Scenes of 1619

Since January, The Times Magazine has been working on an issue to mark the 400th anniversary of the first enslaved people arriving in America.

For teachers

Looking for ways to use this issue in your classroom? You can find curriculums, guides and activities for students developed by the Pulitzer Center at 1619 education.org. And it’s all free!

More on NYTimes.com

Advertisement

Background Essay: Slavery and the US Constitution

Was the united states constitution a pro-slavery document or an anti-slavery document.

Written by: The Bill of Rights Institute

In the summer of 1787, delegates to the Constitutional Convention went to Philadelphia primarily to create a stronger national government than what existed under the first national framework of government, the Articles of Confederation. The issue of slavery was not on the agenda, but could hardly be avoided.

James Madison of Virginia wrote the main divisions in the convention were not those between large and small states, but “between the N[orthern] & South[er]n States” regarding the “institution of slavery & its consequences.”

James Madison, one of the leading delegates at the Constitutional Convention, believed that the main divisions during the drafting of the new framework of government was over the issue of slavery.

The discussion of representation in a national Congress sparked the first major argument about slavery. Southern delegates wanted enslaved people to count the same as a free person because of the region’s large slave population. Charles Pinckney of South Carolina urged it was “nothing more than justice.” Northern delegates did not want to count the enslaved at all. Slaveholders considered them property; counting them would give a political advantage to the South in terms of representation.

A contentious debate took place about slaves and representation. The North did not want to count enslaved people at all for purposes of representation, whereas the South wanted to count them as fully human. The convention settled on a Three-Fifths Compromise: three enslaved persons would count for every five free persons for the purpose of representation. Not for the last time, southern delegates threatened to walk out of the convention if they did not get their way. William Davie of North Carolina warned that “the business was at an end” if the convention did not accept at least the three-fifths rule (though he wanted the enslaved to count fully).

The final version of the Three-Fifths Compromise stated that representatives and direct taxes would be apportioned among the states according to the number of free persons and “three-fifths of all other persons.” Madison later explained the reason for using “person” instead of “slave.” The delegates did not “admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.” The Three-Fifths Clause was a compromise. It was a concession, or perhaps even a defeat, in the convention for the South because the section wanted five-fifths. However, it was a victory for the southern slave power in national politics. But the compromise did not validate slavery nationally.

The delegates to the Convention also fiercely debated the importation of enslaved Africans in the international slave trade. The issue became hotly contested after the Committee of Detail report of August 6 banned the national government from ever interfering with the slave trade.

The permanent protection of the slave trade angered many delegates who agreed with George Mason of Virginia, who called the slave trade an “infernal traf[f]ic.” Luther Martin of Maryland averred that the trade was “inconsistent with the principle of the revolution and dishonorable to the American character.” Edward Rutledge of South Carolina defensively argued that “religion and humanity had nothing to do with the question. Interest alone is the governing principle with Nations.” Twelve of 13 states already had bans or high taxes on the slave trade, so the topic was sure to stir debate.

George Mason was a slaveholder, in Virginia but he spoke out against the institution during the convention.

The delegates from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia strongly argued in favor of the slave trade continuing forever to ensure a constant supply of enslaved Africans. They saw a national limitation on the slave trade as a threat to slavery itself. Charles Pinckney cautioned the people of his South Carolina would “never receive the plan if it prohibits the slave trade.” Many southern states, he predicted, “shall not be parties to the Union.”

A Committee of Eleven— known as the Committee on the Slave Trade —met to hammer out a compromise on the issue. The committee severely curtailed the previous inability of Congress from ever interfering with the slave trade. The committee offered that Congress could not interfere with the institution until 1800. The delegates of the Lower South bargained hard to get the convention to approve pushing the date back to 1808.

The South lost a major point of protecting the slave trade forever but forced a concession of 20 years under threat of disunion. The region, with the help of northern merchants, would tragically import tens of thousands of enslaved Africans during those two decades. Ultimately, in 1807 President Thomas Jefferson called for and Congress passed a law banning the international slave trade on January 1, 1808 — the earliest constitutionally-allowable moment.

After reaching its compromise on the slave trade, the Constitutional Convention addressed a committee’s proposal on fugitive slaves. The question of fugitive slaves became a major issue because northern emancipations meant enslaved persons might run away to free states in the hope of gaining their freedom. A consensus existed on allowing runaways to be claimed by slaveholders based upon state comity, or states respecting the laws of other states. Pierce Butler of Georgia and Charles Pinckney introduced a motion requiring “fugitive slaves and servants to be delivered up like criminals.” Yet many northern delegates opposed the motion because their states did not want to be forced to “deliver up” runaways.

The convention settled upon the Fugitive Slave Clause that read, “No Person held to Service or labor in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another … shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or labor may be due.” Significantly, the clause did not recognize a property in man, did not compel free states to participate in the recapture, and did not give national sanction to slavery because it stated the institution was under state law. Although the enforcement provision was removed from the final version, it nonetheless declares the fugitive “shall be delivered up.” The ambiguity would produce decades of controversy over who was responsible for enforcing the Fugitive Slave Clause. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 would later make highly controversial changes to this understanding and cause a firestorm of outrage and resistance in the North.

The Constitution was ratified in 1788 and became the law of the land. The Constitution did not end slavery, which continued to grow and spread in the South at the same time it receded in the North. However, the Constitution did not protect a property in man, nor did it provide for national validation of the institution. The Constitution supported the concept of “freedom national, slavery local.” That is, slavery was to remain a matter of state and local law. Importantly, the federal government therefore could not interfere with the institution in the states where it already existed. This tenuous compromise related to slavery resulted in a “house divided,” in Abraham Lincoln’s words, “half-slave and half-free.” This had significant consequences for the history of the United States from 1787 to 1865 and after.

The exact character of the Constitution also had significant consequences for how it was understood and interpreted. Some saw the Constitution as a pro-slavery document, even across a broad political spectrum. Radical abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison called the Constitution a “covenant with death” and an “agreement with hell.” Chief Justice Roger Taney endorsed the idea of a pro-slavery Constitution strongly in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), which stated Blacks were not citizens of the country and could not be because they were inferior. Senator John Calhoun of South Carolina advanced a similar argument.

Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass agreed with Garrison for several years but then notably changed his mind. After long study and reflection, he defended the idea that the Constitution was anti-slavery. He called the Constitution a “glorious liberty document” and believed it supported anti-slavery principles. Abraham Lincoln concurred and had to navigate the shoals of “freedom national, slavery local” in his decisions related to slavery as president. The Emancipation Proclamation and Thirteenth Amendment showed Lincoln bound by constitutionalism and the virtue of prudence in dealing with slavery.

Scholars on both sides of the question continue to argue about the pro-slavery or anti-slavery character of the U.S. Constitution and what it meant and means to the American republic.

Related Content

Constitutional Convention

Use this lesson with The Constitutional Convention Narrative and after students have done The Articles of Confederation, 1781 Primary Source activity.

Compromise, Convention & the Constitution | Julie Silverbrook | BRI’s Constitutional Conversations

Julie Silverbrook, Executive Director of the Constitutional Sources Project, discusses how and why the Constitutional Convention came into being.

Constitutional Reasoning and its Outcomes

Explore constitutional reasoning in the Supreme Court through the lens of Morse v. Frederick (2007).

IMAGES

COMMENTS

A Brief History of Slavery That You Didn't Learn in School. Four hundred years after enslaved Africans were first brought to Virginia, most Americans still don’t know the full story of slavery...

Slavery in America was the legal institution of enslaving human beings, mainly Africans and African Americans. Slavery existed in the United States from its founding in 1776 and became the...

Slavery gave America a fear of black people and a taste for violent punishment. Both still define our prison system. Essay by Bryan Stevenson

From their point of view, Reconstruction was a tragic period of American history in which vengeful White Northern radicals took over the South. In order to punish the White Southerners they had just defeated in the Civil War, these Radical Republicans gave ignorant freedmen the right to vote.

Slaves were of varying importance in Mesoamerica and on the South American continent. Initially slaves were imported because of a labor shortage, aggravated by the high death rate of the indigenous population after the introduction of European diseases in the early 16th century.

To explore American slavery in its full international context, then, is essentially to tell the history of the globe. That task is not possible in the available space, so this essay will explore some key antecedents of slavery in North America and attempt to show what is distinctive or unusual about its development.

African Americans - Slavery, Resistance, Abolition: Enslaved people played a major, though unwilling and generally unrewarded, role in laying the economic foundations of the United States—especially in the South.

Under slavery, an enslaved person is considered by law as property, or chattel, and is deprived of most of the rights ordinarily held by free persons. Learn more about the history, legality, and sociology of slavery in this article.

Civil War, 1861-1865. Jonathan Karp, Harvard University Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, PhD Candidate, American Studies. The story of the Civil War is often told as a triumph of freedom over slavery, using little more than a timeline of battles and a thin pile of legislation as plot points.

Background Essay: Slavery and the US Constitution. Was the United States Constitution a pro-slavery document or an anti-slavery document? Written by: The Bill of Rights Institute.