Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Digital transformation of an academic hospital department: A case study on strategic planning using the balanced scorecard

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Rheumatology, Departement Appareil Locomoteur (DAL), University Hospital Lausanne (CHUV) and University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Rheumatology, Departement Appareil Locomoteur (DAL), University Hospital Lausanne (CHUV) and University of Lausanne, Switzerland, Department of Urology,Inselspital and University of Bern,Bern, Switzerland

- Thomas Hügle,

- Vincent Grek

- Published: November 17, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000385

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

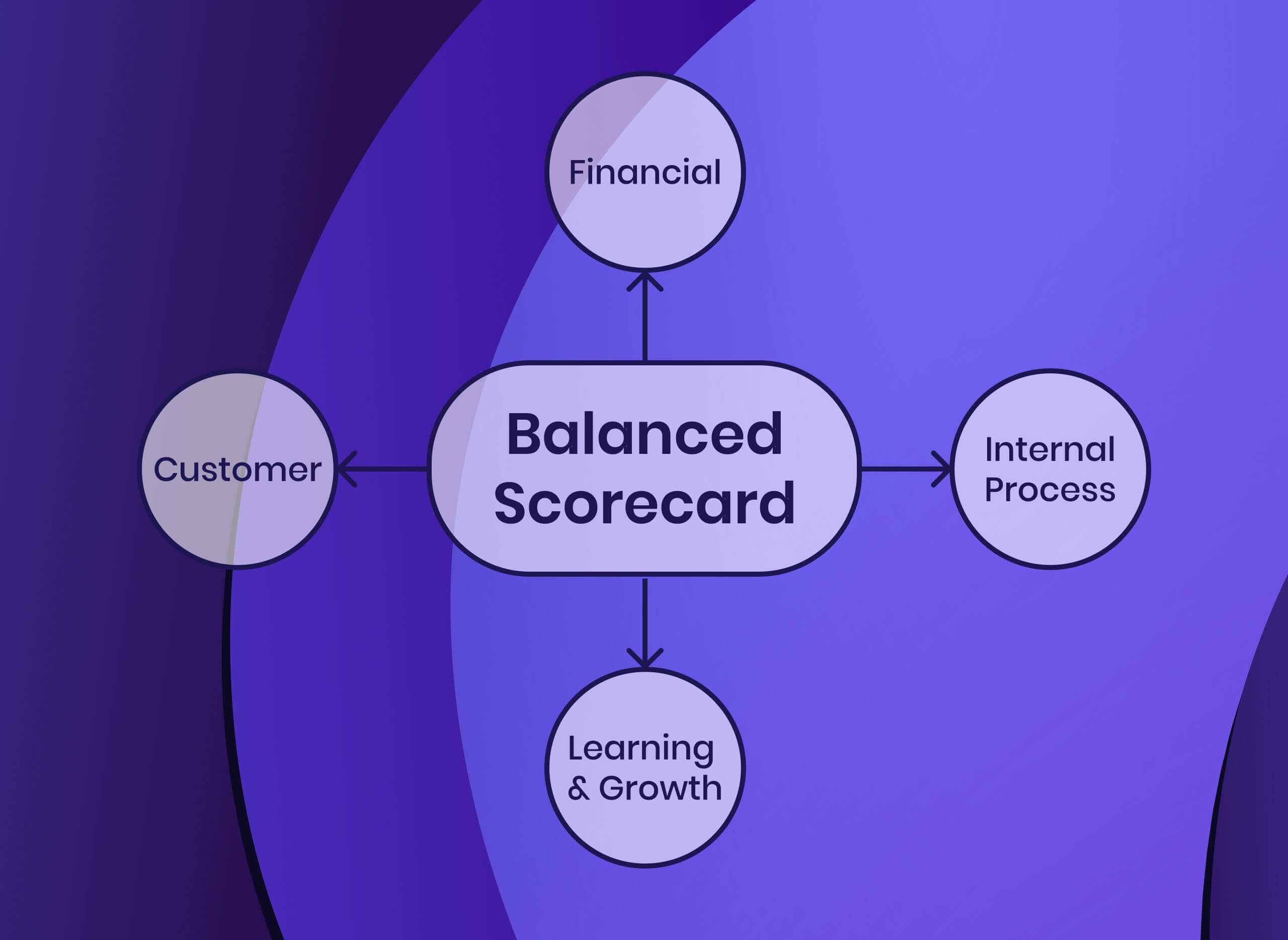

Digital transformation has a significant impact on efficiency and quality in hospitals. New solutions can support the management of data overload and the shortage of qualified staff. However, the timely and effective integration of these new digital tools in the healthcare setting poses challenges and requires guidance. The balanced scorecard (BSC) is a managerial method used to translate new strategies into action and measure their impact in an institution, going beyond financial values. This framework enables quicker operational adjustments and enhances awareness of real-time performance from multiple perspectives, including customers, internal procedures, and the learning organization. The aim of this study was to adapt the BSC to the evolving digital healthcare environment, encompassing factors like the recent pandemic, new technologies such as artificial intelligence, legislation, and user preferences. A strategic mapping with identification of corresponding key performance indicators was performed. To achieve this, we employed a qualitative research approach involving retreats, interdisciplinary working groups, and semi-structured interviews with different stakeholders (administrative, clinical, computer scientists) in a rheumatology department. These inputs served as the basis for customizing the BSC according to upcoming or already implemented solutions and to define actionable, cross-level performance indicators for all perspectives. Our defined values include quality of care, patient empowerment, employee satisfaction, sustainability and innovation. We also identified substantial changes in our internal processes, with the electronic medical record (EMR) emerging as a central element for vertical and horizontal digitalization. This includes integrating patient-reported outcomes, disease-specific digital biomarker, prediction algorithms to increase the quality of care as well as advanced language models in order save resources. Gaps in communication and collaboration between medical departments have been identified as a main target for new digital solutions, especially in patients with more than one disorder. From a learning institution’s perspective, digital literacy among patients and healthcare professionals emerges as a crucial lever for successful implementation of internal processes. In conclusion, the BSC is a helpful tool for guiding digitalization in hospitals as a horizontally and vertically connected process that affects all stakeholders. Future studies should include empirical analyses and explore correlations between variables and above all input and user experience from patients.

Author summary

Digital transformation enhances hospital efficiency and quality, yet the integration of these technologies poses challenges that require clear direction. The Balanced Scorecard (BSC) is a tool that helps institutions gauge and action new strategies, not limited to financial metrics. It promotes rapid adjustments and offers clarity on performance on different perspectives. The university hospital sector is suitable for the application of the BSC, as the financial perspective is important, but other perspectives such as patient care and safety or research and innovation are equally important. This study adapted the BSC for current and future digital health solutions such as digital therapeutics or biomarker, AI or automation. Key performance indicators span across education, employee satisfaction and patient empowerment. By collecting insights from diverse stakeholders at a Swiss University Hospital, we developed a custom BSC. This updated BSC accentuates the role of electronic medical records in digitalization and underscores communication challenges between departments. A crucial insight is the importance of digital health literacy for both patients and staff. In essence, the BSC adeptly steers hospitals through digital transitions. Future studies should emphasize real-world testing and patient feedback.

Citation: Hügle T, Grek V (2023) Digital transformation of an academic hospital department: A case study on strategic planning using the balanced scorecard. PLOS Digit Health 2(11): e0000385. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000385

Editor: Benjamin P. Geisler, Massachusetts General Hospital, UNITED STATES

Received: February 3, 2023; Accepted: October 10, 2023; Published: November 17, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Hügle, Grek. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are included in the manuscript.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: I have read the journal’s policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: TH has received speaker fees or research grants from Fresenius Kabi, Abbvie, BMS, Lilly, Janssen and GSK. He is a scientific board member of Atreon and Vtuls and patent holder of a digital biomarker for joint swelling. VG has no competing interest.

Introduction

Digital transformation is an ongoing process in hospitals that has enormous potential to improve patient care, optimize costs, and streamline resources [ 1 ]. The advancements in computing power, data storage, and interoperability, such as the electronic medical records (EMR) with mobile devices, and the growing availability of artificial intelligence (AI) to harness this data flood, are reshaping healthcare [ 2 ]. These changes are occurring against the backdrop of an aging society with more comorbidities, increasing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration. However, healthcare systems are also encountering rising costs due to advanced diagnostic and therapeutic interventions and a critical shortage of healthcare professionals. Therefore, it is essential to reorganize healthcare at the point of care as well as on institutional and systemic levels using new digital tools, including AI and automation [ 3 ].

Integrating new digital solutions in hospitals is challenging and requires breaking down data and knowledge silos. On a vertical level, healthcare professionals, administrative staff, and patients use different indicators to measure quality and satisfaction and often do not speak the same language. The same is true horizontally, with a considerable lack of communication and data usage both between medical specialties and patients. This notably applies for overlapping pathologies such as immune-mediated disorders or chronic pain requiring parallel care. Hospitals hardly use digital devices to overcome these silos, apart from using the same EMR. Interdisciplinary case discussions in person, by email, or phone are rare occasions to interact with colleagues from other disciplines to take decisions and learn from each other. However, due to the lack of time and staff, such meta-networks are hardly scalable.

A range of new digital solutions addresses these issues. Many are already certified, such as >500 FDA-cleared AI algorithms, certified mobile health applications, and digital therapeutics such as the German DIGAs (Digitale Gesundheitsanwendung). Other solutions with a potentially large impact are upcoming, such as large language models (LLM) and transfer learning models that exploit and harmonize unstructured clinical data and biomarkers across disciplines. New applications are also available for the EMR as a central digital element in patient care, expanding and leveraging it horizontally and vertically, such as AI or mobile patient applications.

Responsible persons in hospitals are aware of this development, but the implementation of digital tools in clinical practice is anything but easy. Digital transformation requires a high investment in technology and stakeholder training to create gains in operational efficiency, medical care, and cost-reduction. Different expectations from the economic, clinical, and patient perspective make it difficult to prioritize and approach digitalization implementation.

This study analyzes existing and emerging needs of our hospital department and projects existing and new digital solutions across the value chain. The article presents a systematic methodology that takes into account the mission and vision of the institution, current healthcare trends, and shows the impact of digital tools on key processes and their indicators. A central element of this study is the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) as a strategic management and planning system to improve internal operations and project external outcomes [ 4 ]. It has been developed to monitor and improve real-time performances, for operational adjustments and for implementation of new strategies [ 5 ]. The BSC is adapted to the hospital perspective with a focus on clinical, patient, quality of care, and innovation outcomes and their key performance indicators (KPIs) [ 6 ]. The possible impact of existing and upcoming digital solutions on these outcomes is analyzed, and internal processes and knowledge are discussed to implement them in clinical practice.

This monocentric, observational study on strategic planning was conducted in the rheumatology department of the University Hospital in Lausanne (CHUV), Switzerland from 2017–2023. It included restrictions and subsequent new digital developments during the SARS-Cov2 pandemic. Data were used from a general retreat, working and focus groups as well as semi-structured interviews with different stakeholders and a literature and social media review. The methodological process is illustrated in Fig 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000385.g001

Retreat and working groups

An initital retreat with all institutional stakeholders on a cadre level (doctors, nurses, adminsitrative) was performed 2017 to define visions, missions and clinical priorities. A SOAR analysis (Strengths, Opportunities, Aspirations, and Results) has been performed [ 7 ]. Clinical needs and potential digital solutions were further elaborated in monthly working groups over six months. Subsequently, existing key processes were analyzed in four working groups (patient care, organisation, research and education).

Semi-structured interviews, focus groups and conferences on an institutional level

We performed interviews with all stakeholders, including the informatic department, administration, clinicians, nurses and researchers. The status quo of implemented digital solutions and ongoing projects in terms of digital transformation were investigated. Data access and interfaces on an institutional level were discussed. From a clinical side, we organised a yearly interdisciplinary conference between rheumatology, gastro-enterology and dermatology on immune-mediated diseases to understand the clinical needs and developments of each speciality ( www.common-ground-meeting.org ).

Technological review

Information on existing digital solutions for health care insititutions was obtained by literature review on Pubmed, Google, social media (mainly LinkedIn) and podcasts (e.g. Medical AI Podcast, DTx Podcast, Faces of Digital Health, Deep Minds). We created the « Digital Rheumatology Network » ( www.digitalrheumatology.org ) as international platform to educate digitalization in rheumatology along with a conference series called Digital Rheumatology Day was started 2019. This platform served inform and connect clinicians and researcher with digital companies and start-ups in the field.

Adapted Balanced Scorecard and Strategy Mapping

The Balanced Scorecard was adapted to measure or project performances of digital solutions according four perspectives: financial, customer, internal processes and learning and growth. Vision, mission and have been elaborated in the working groups. Internal and external customers have been defined as patients, clinicians, health care professionals and administration. Financial performance has been shifted to « values », which were defined as: patient empowerment, clinical-decision support, time-saving, cost-effectiveness and quality.

Variables and KPI

KPI have been identified and assessed for measurability and feasibility in the working groups based on a clinical, internal, learning, quality of care or innovation perspective. According the clinical focus of this work KPIs shown in Fig 1 concern efficiency and effectiveness, qualiy of care, time management, scientific development of health care professionals, patient-centeredness, technology and information systems and interdisciplinary communication.

Strategic mapping

The primary result of this work is a strategic map based on an adapted Balanced Scorecard according key procedures for digitalization ( Fig 2 ). Previously, missions, visions and values facing new medical trends have been elaborated in a retreate and subsequent working groups. Internal processes and knowledge in terms of digitalisation have been worked out in semi-structured interviews, literature and social media search. Each chosen subset of the BSC was aligned with current developments in healthcare and digital technology.

From bottom-up the figure shows people & organisation, internal processes, customers, values and missions. Values have been adapted to current healthcare trends. Exemplary indicators are listed on the right. Artificial intelligence based models are indicated in orange. DTX: Digital therapeutics. PRO: Patient reported outcomes. EMR: Electronic medical record.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000385.g002

Mission and vision

We defined the mission of our academic department as cost-effective and state-of-the-art patient care, combined with a high level education and research. The vision was to overcome the challenges that come along with demographic changes of our society and staff shortage by becoming a smart hospital. We envision a countinously fluctuating healthcare system, e.g. due to the occurrence of infection waves, accidents or natural phenomena (heat or cold waves etc.). We aim to foster digital transformation but also to celebrate human interaction and contact with patients that are in control of their decisions and data.

Apart from a financial aspect, we defined four health care developments as the key values in our department:

- 1 . Patient empowerment and convenience

Healthcare is developing towards a consumer-driven service. Patients want to actively chose their site of patient care and doctors. Less wating times, accessiblity via email ect. appointments online ect. This also applies at least for a portion of the patients that prefer a more active role in managing their chronic disease by monitoring their symptoms, providing patient reported outcomes (PROs) or even taking over clinical decisions after appropriate training [ 8 ]. Patient convenience from the medical and digital side (not in terms of hospitality) has so far remained largely unexamined in hospitals, although it has a significant impact on the quality of life as a measurable indicator. Of note, convencience can be more important to patients than quality of care [ 9 ].

- 2. Personalized medicine

Personalized medicine approaches aim to streamline individualized diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for high efficacy and safety of care. This means a higher diagnostic effort (e.g. by -omics) and the integration of digital biomarkers and real world data in our workflow [ 10 ]. The exploitation of biomedical and clinical data by machine learning algorithms allows the prediction of individual disease courses, treatment response or phenotyping (clustering) as clinical decision support systems [ 11 ]. Thus, higher costs in diagnostics and data analysis might be compensated by better efficiency, lower complications and secondary healthcare costs.

- 3. Interdisciplinary care

In many chronic diseases, notably immune-mediated diseases or cancer, symptoms of different body systems often are compulsorily connected e.g. skin and joint inflammation in psoriasis arthritis, immune dysregulation due to immunotherapy in cancer or chronic pain and depression [ 12 ]. Quality of care depends on an optimal exchange of data and clinical decision between medical and paramedical information which bears a substantial number of barriers in terms of data interoperability. The individual ’point of care’ which is not always clear to the patient (private practice, hospital, pharmacy, online), needs to be redefined. Digital platforms or EMR with interdisciplinary dashboards may support an efficient and time saving exchange [ 13 ].

- 4. Sustainability and automatisation

The shortage of healthcare professionals, notably nurses, doctors or administrative staff is an emerging problem which leads to employee dissatisfaction and sick leave. Automatisation of simple procedures such as voice, image or text recognition has largely been implemented e.g. for medical documentation. There are several FDA-approved algorithms for automated evaluation of radiographs e.g. for fracture detection on the market. So far, those solutions are not an active clinical decision support but they likely increase quality as ‘double check’ or if no radiologist is available. Finally, advanced technology in chatbots such as ChatGPT from OpenAI could potentially support administrative tasks such as writing and correcting medical reports. Care robots are slowly touching ground in hospitals and care homes in order for transport but also for vital signs and PRO assessment [ 14 ].

Customers of our structure are patients (whether face-to-face or remote), clinicians, healthcare professionals, administrative staff and scientists. Accordingly, the needs of those internal and external customers on the BSC are anchored as clinical decision support, patient support, administrative support and research infrastructure. New types of customers are entering healthcare systems such as remote healthcare professionals (e.g. telenurse or online coaches), DIGA (Digital health application) providers ect. [ 15 ].

Internal processes (Digital Care Pathways)

Internal processes in hospitals are responsible to maintain and improve quality, efficiency and safety. Fig 2 (left) shows various forms of digital data collection (telemonitoring, digital biomarkers, biosensors ect.) as the basis for a personalized medicine. AI-models likely integrated in the EMR permit to define phenotypes, disease predictions and to perform transfer learning from concomitant (autoimmune) diseases. This supports the creation of digital care pathways that organise individual patient monitoring and treatment and orchestrate ressouces optimally. Data accessibility and connectibility is a main process for horizontal digitalization, both in terms of providing user interfaces, data privacy and legal certainty. Usability and intepretability of data is considered as a key process to avoid data and knowledge silos. This concerns structured data at the moment, but can be enlarged unstructured data e.g. by large language models. Clearly, external registries or other data sources should be interoperable with hospital systems, especially the EMR.

Generally, the EMR can be considered as the main tool to integrate new digital solutions horizontally and vertically ( Fig 3 ). For example. EMR can be extended vertically by integrating PROs, Patient reported experiences (PREs), digital biomarker or apps [ 16 ]. According to the ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT), the concept ‘Internet of Medical Devices’ (IoMD) should be promoted. Horizontally, dashboards increase usability of EMR between specialities and AI-generated predictions (including transfer learning algorithms) can be included in those interdisciplinary dashboards. New generation clinical dashboards also should show a holistic patient journey including predictions and outlier analysis etc. In the sense of horizontal integration along the value chain, the prediction should be connected to data on the availability of follow-up care facilities. The first step of AI-guided clinical pathway / decision support will likely be auto-care loops in stable disease courses. A maximal amount of collected data will be analyzed by clustering and prediction models, a digital treatment plan will be established and automatically monitored and reported to health care professionals including remote nurses. Smart agenda planning allows to identify and planify patients with a high flare risk for a conventional visit.

Elements around the EMR have been taken from the Balanced Scorecard (internal procedure perspective) and regrouped for a better demonstration.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000385.g003

Finally, automatisation is a sine qua non to encounter the shortage of rheumatologists and health care professionals. Large language models (LLM) such as GPT4 can be used to screen EMR and hospital databases for data or for the generation of discharge letters [ 17 ]. Voice recognition systems have widely been introduced in the clinic. New generation chatbots are able to extract the necessary information to create discharge reports and thus save time for the clinician to spend more time with patients or in interdisciplinary discussion. It seems primordial that all staff are equipped with smartphones and apps for those dashboards. Communication between colleagues in- and outside the hospital is via Email, which seems not adequate for several reasons (high number of unreplied messages, spam, security ect). It is obvious to connect case-based communication to dashboards in order to save time and to get relevant Information in a few clicks. All those digital processes together with their KPIs illustrate digital care pathways.

People and organisation (learning organisation)

In order to implement (digital or other) innovations, the human factor remains indispensable. This is especially true in medicine, where human interaction and ethical concerns are or paramount importance. Therefore, change management is the basis for creating readiness and acceptance for new technologies. In chronic diseases, a holistic view on patient journeys (or digital clinical pathways) with patient-centered endpoints and indicators are of increasing importance. Both patients and healthcare professionals need to understand how to access and inteprete this data and how to guarantee data privacy. To this end, knowledge about the inhouse databases (data warehouse etc.) and external data sources (registries or apps) as well as basic knowledge on data science is required and should be educated as a first step. The national or federal strategy for education of digital health is currently being actively discussed, but is only interoperable to a limited extent due to the different health systems [ 18 ]. Thus, a regular exchange between institutional, pan-departmental data scientists and collaborators within clinical departments ‘closer to clinical action’, shoud be established. Clinical-informaticians within medical departments are key elements for horizontal digitalization. For exemple they can educate clinicians use EMR more efficiently, including processes such as billing or implementing new processes such as prescribing DIGAs (Digitale Gesundheitsanwendung, digital health application) [ 15 ].

Human clinical know-how is also required to build and to control machine learning algorithms. As for input variables for algorithms (e.g. for clinical predictions), it is obviously not just about the availability but also the quality of the clinical data (e.g. what, when and how was measured). Clinicians need to specify the relevance of the data. As an exemple in image recognition, clinically defined pre-processing increases the prediction performance. As an example focusing on the hip shape to predict radiographic progression of hip ostearthritis [ 19 ].

No-coding platforms for image recognition or natural language processing can support clinicians in creating on predictions based on the insitutional data. For natural language processing, chatbots such as the openAI chatbot can leverage the work of doctors and scientists by support of writing articles or create automated reports and save precious time. Those tools are typically explored in defined research projects or audits before integrating them in the clinical workflow. Clearly, data safety issues have to be addressed rigourously and with new technological tools, its strengths and weaknesses are yet to be fully understood–and there appears early indication that such chatbots can be prone to confabulating information. An example of a medical report generated by the chatGPT3 chatbot can be found in S1 Table .

Patient education in the use of wearables, apps, digital therapeutics or biomarkers is pivotal. However low adherence to digital tools such as DIGAs is a widely undadressed problem [ 20 ]. Beside gamification, avatars or better human companion (e.g. health coaches) are necesary to assure adherence and quality of care. For mental health care, which also affects a substantial part of patients with immune-mediated diseases in form of secondary fibromyalgia, the human companionship seems even more important. Therefore, the need for trained remote health care professionals, e.g. as health coaches, will increase strongly in the future. A new profession of online nurses is also emerging among nurses, who work for hospitals or insurance companies and are connected to patients via a wide range of digital tools [ 21 ].

On a national and internationa level, both societies such as EULAR and patient organisations foster education and exchange of digital solutions [ 22 ]. To support this endavour, we created the digital rheumatology network ( www.digitalrheumatology.org ) organising yearly conferences (Digital Rheumatology Days) and regular pod-and webcasts.

The BSC has been developed around key indicators so they can and should be obtained at all levels. In other words, what is measurable within a digital care pathway should be measured. In our opinion, extra hours, sick leave and employer satisfaction are among the most urgent KPI, given the shortness of health care professionals and the wish for part-time positions. Patient empowerment and convenience measured by patient satifaction is also notably important to create and maintain trust as the basis of successful care.

For skills, education levels both of patients and clinicians can be measured by the number of attended courses, podcasts ect. Prescribed DIGAs and telemonitoring reports and patient adherence to those can be measured and discussed during face-to-face consultatons. PREs can be used to reflect the mix of human and digital therapeutic services offered by the department. Internal processes, including automatisation procedures, can be monitored by reduced extra-hours. Measuring ’connected care’ is more subtle but could be measurable by reduced length of hospital stay or readmission rates and patient satisfaction. Of note, many aspects of patient care such as empathy, time for listening can not be measured.

Implementation in our department and first results

In our and many other hospitals, the key aspects of digital transformation are initiated top-down from an institutional level. For example, the online assignment of patients for consultations or hospitalisation or telemonitoring via an app for post-operative patients that is supervised by a central nurse team. The access to the data warehouse for scientific purposes has been facilitated and a machine learning team for clinical predictions or biomedical (big) data analysis collaborates closely with medical departments on a project level. To leverage these and other opportunities, we initiated a bottom-up strategy according to the above mentioned factors. On a departimental level, we have introduced regularly scheduled meetings between clinicians and institutional IT specialists. A clinician-informatician consultant provides regular training in basic machine learning coding and institutional data access to our clinical and research team. Clinical data science training using data from registries and our datawarehouse has been added to the curriculum for new assistant doctors. A specialized nurse consultation for rheumatic patients has been implemented to instruct patients in the use of apps with PROs, here within our national registry SCQM (Swiss Cohort for Quality Management), wearable data and the use of digital therapeutics. As our current EMR is lacking clinical scores and indicators such as the DAS28 score, we included the mannequin for tender and swolen joints and were thus able to synchonize EMR with the registry. Patients can send pictures or videos of their hands into our system via apps. We have developed an algorithms that automatically measure the finger folds, joint diameter etc. on hand images to monitor joint swelling [ 23 ]. The range of motion can be estimated on self-recorded videos of patients by automatically measuring the angles of the different joints and comparing them with the previous values. In the future, hopefully such disease-specific biomarker will earlier detect of arthritis flares.

A telemonitoring & communication office is currently being set up where medical medical assistants are trained to become ‘clinical workflow & communication manager’ with access to PROs, wearables, photos, videos etc. on specific dashboards and obviously the agenda of our consultation. In parallel to telephone calls and emails from patients they forward information (or not) to specialized nurses or our rheumatologist and to refer patients to the consultation.

Five years ago we started an international conference series called the ’Digital Rheumatology Days’ ( www.digitalrheumatology.org ) for healthcare professionals to educate them on telemonitoring, digital therapeutics/DIGAs, digital biomarkers, social media usage, machine learning ect. The annual conference was complemented by the Digital Rheumatology Network as an educational platform where information, podcasts, webcasts, etc. are permanently published and distributed via social media. To foster interdisciplinarity as part of the connected care model, the Common Ground Meeting for Immune-mediated Diseases has been created (common-ground-meeting.org), assembling different specialties for disease updates, the use of data (e.g. presentation of digital biomarkers) and case discussions by rheumatologists, dermatologists, gastro-enterologists, immunologists, nephrologists and pneumologists.

So far, the internal processes mentioned above have been partially implemented. Digital tools and data science have mainly been introduced on a project basis, with ongoing studies ( S1 Table ).

We present a comprehensive mapping of digital transformation in a rheumatology hospital department, focusing on current digital developments and the evolving values in healthcare. By utilizing the BSC framework, we effectively illustrate how the implementation of digital solutions, both existing and upcoming, can enhance our performance on different levels towards achieving a ’connected care model’ that aligns with the institution’s mission and vision.

First of all, this strategic mapping emphasizes the significance of bottom-up education for all stakeholders, including patients, to promote the adoption of new digital tools. We propose that knowledge on data science, app technology, cloud computing, and the fundamentals of AI, such as large language models, is a vital process in transforming healthcare organizations into learning environments that better support patients, administration, and healthcare professionals. In this context, the BSC may improve organizational performance by facilitating double-loop learning and disseminating the hospital’s vision as a learning organization [ 24 ].

During our research, we identified a knowledge gap concerning institutional digital solutions or collaborative projects developed within the hospital. For instance, a platform designed for accessing clinical data for research purposes faced low adoption rates primarily due to a lack of awareness among clinical departments. Regular meetings between the institution and clinicians or the appointment of a clinician-informatician emerged as crucial strategies to leverage digitalization and foster adoption.

Furthermore, we demonstrate that the electronic EMR plays a pivotal role in the digital transformation of healthcare. As illustrated in Fig 3 , The EMR can be expanded both horizontally and vertically e.g. through the integration of AI algorithms, apps, interdisciplinary dashboards, wearable data, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), ultimately serving as the central point of care within a hospital.

Initially, the BSC was developed to establish relationships between actions and process performance in business institutions at levels beyond financial values. The hospital as ‘institution’ has evolving values and a very short half-life of knowledge and technology.

In a first step, we established a BSC framework that corresponds to the current state of knowledge and digitalization. Over time, key success factors in hospitals have undergone changes, particularly in terms of employee satisfaction and patient empowerment. Interdependencies with other sub-units (= interdisciplinarity) have also become increasingly important and should be taken into account when selecting KPI.

It is important to note that this strategic mapping does not serve as a manual for digitalization but rather aims to inspire others to conduct similar exercises in order to create a ’compass’ for responsible healthcare professionals.

We must acknowledge several limitations of this work. KPI implementation was only partial, and processes at different levels have not yet been fully connected or supported by empirical data. Thus, we cannot demonstrate causal relationships among key indicators within or across the four perspectives, as previously shown in hospital settings [ 25 ]. Therefore, the full potential of the BSC remains untapped. Adoption of the BSC healthcare professionals may prove challenging [ 5 ]. Another limitation lies in the fact that the BSC has shown limitations in measuring human relations, which are crucial components of learning organizations in the healthcare sector [ 26 ].

In conclusion, digital transformation is a complex and ongoing process that requires meticulous planning on various levels. The BSC proves to be a suitable tool for both planning and monitoring this significant endeavor. Digital tools should enable better care and save time, allowing healthcare professionals to focus on valuable human interaction that algorithms can never replace.

Supporting information

S1 table. implemented digital aspects in our rheumatology department..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000385.s001

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chris Lovejoy for his valuable review of the manuscript.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (44,031,989 articles, preprints and more)

- Available from publisher site using DOI. A subscription may be required. Full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Priority-setting and hospital strategic planning: a qualitative case study.

Author information, affiliations.

Journal of Health Services Research & Policy , 01 Oct 2003 , 8(4): 197-201 https://doi.org/10.1258/135581903322403254 PMID: 14596753

Abstract

Full text links .

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1258/135581903322403254

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, alternative metrics.

Article citations

Ethics education and moral decision-making in clinical commissioning: an interview study..

Knight S , Hayhoe BW , Frith L , Ashworth M , Sajid I , Papanikitas A

Br J Gen Pract , 70(690):e45-e54, 26 Dec 2019

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 31848203 | PMCID: PMC6917357

Free full text in Europe PMC

'You can give them wings to fly': a qualitative study on values-based leadership in health care.

Denier Y , Dhaene L , Gastmans C

BMC Med Ethics , 20(1):35, 27 May 2019

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 31133017 | PMCID: PMC6537214

Leadership styles in two Ghanaian hospitals in a challenging environment.

Aberese-Ako M , Agyepong IA , van Dijk H

Health Policy Plan , 33(suppl_2):ii16-ii26, 01 Jul 2018

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 30053032 | PMCID: PMC6037062

Setting healthcare priorities: a description and evaluation of the budgeting and planning process in county hospitals in Kenya.

Barasa EW , Cleary S , Molyneux S , English M

Health Policy Plan , 32(3):329-337, 01 Apr 2017

Cited by: 23 articles | PMID: 27679522 | PMCID: PMC5362066

Setting Healthcare Priorities at the Macro and Meso Levels: A Framework for Evaluation.

Barasa EW , Molyneux S , English M , Cleary S

Int J Health Policy Manag , 4(11):719-732, 16 Sep 2015

Cited by: 31 articles | PMID: 26673332 | PMCID: PMC4629697

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Hospital priority setting with an appeals process: a qualitative case study and evaluation.

Madden S , Martin DK , Downey S , Singer PA

Health Policy , 73(1):10-20, 10 Dec 2004

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 15911053

Priority setting in a hospital critical care unit: qualitative case study.

Mielke J , Martin DK , Singer PA

Crit Care Med , 31(12):2764-2768, 01 Dec 2003

Cited by: 37 articles | PMID: 14668612

SARS and hospital priority setting: a qualitative case study and evaluation.

Bell JA , Hyland S , DePellegrin T , Upshur RE , Bernstein M , Martin DK

BMC Health Serv Res , 4(1):36, 19 Dec 2004

Cited by: 26 articles | PMID: 15606924 | PMCID: PMC544195

A strategic approach for negotiating with hospital stakeholders.

Blair JD , Savage GT , Whitehead CJ

Health Care Manage Rev , 14(1):13-23, 01 Jan 1989

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 2647668

The use of cost-effectiveness by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE): no(t yet an) exemplar of a deliberative process.

Schlander M

J Med Ethics , 34(7):534-539, 01 Jul 2008

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 18591289

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

Essentials of Strategic Planning in Healthcare, Third Edition

Jeffrey p. harrison, phd, fache.

- Member Price: $68.60

- Non Member Price: $98.00

- Strategic Planning

Book Description

- Current data on healthcare spending, hospital statistics, healthcare employment, and the use of healthcare technology

- New content on the use of artificial intelligence and big data in healthcare, as well as the benefits of block chain technology

- Coverage of future advances in healthcare, including genomics and Medicare for All

- Expanded marketing content, including the latest trends in websites, digital outlets, and social media

- Table of Contents (PDF)

- Preface (PDF)

- Book Excerpt (PDF)

- Transition Guide

- Instructor Resource Sample

- Corrections

- PURCHASE EBOOK FROM AMAZON KINDLE SALES

- PURCHASE EBOOK FROM CHEGG

- PURCHASE EBOOK FROM VITALSOURCE (INGRAM)

Futurescan 2017: Healthcare Trends and Implications 2017-2022

Futurescan 2018: Healthcare Trends and Implications 2018-2023

Looking Back to Look Forward: AUPHA at 70

Futurescan 2016: Healthcare Trends and Implications 2016-2021

-b084e1dd.jpg?w=160)

Management of Healthcare Organizations: An Introduction, Third Edition

Evidence-Based Management in Healthcare: Principles, Cases, and Perspectives, Second Edition

Strategic Healthcare Management: Planning and Execution, Second Edition

Futurescan 2019–2024: Healthcare Trends and Implications

Exceptional Leadership: 16 Critical Competencies for Healthcare Executives, Second Edition

Futurescan 2022–2027: Health Care Trends and Implications

Marketing Health Services, Fourth Edition

Getting It Done: Experienced Healthcare Leaders Reveal Field-Tested Strategies for Clinical and Financial Success

Why Hospitals Should Fly: The Ultimate Flight Plan to Patient Safety and Quality Care

Transformative Planning: How Your Healthcare Organization Can Strategize for an Uncertain Future

Leadership for Public Health: Theory and Practice

An Insider’s Guide to Working with Healthcare Consultants

Healthcare Strategic Planning, Fourth Edition

Strategic Analysis for Healthcare: Concepts and Practical Applications, Second Edition

Make It Happen: Effective Execution in Healthcare Leadership

The Future of Healthcare: Global Trends Worth Watching

Use of Q methodology for hospital strategic planning: a case study

Affiliation.

- 1 Cardinal Health Alliance, Muncie, Indiana, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 11187361

This study was designed to illustrate how Q Methodology can be used as a tool for strategic planning. Potential plans for the future of a small Indiana hospital were formulated and Q sorted to determine support or resistance by key leaders from within hospital management, the board, and the medical staff. The hospital was able to identify stakeholder perceptions that resulted in strong consensus that integration should be a priority for the hospital. This exercise provided a list of objectives for hospital leadership and the results were also used to justify the cessation of several programs that the hospital leadership had been pursuing.

- Attitude of Health Personnel

- Decision Making, Organizational

- Governing Board

- Group Processes

- Hospital Administrators

- Hospital Bed Capacity, 100 to 299

- Hospital Planning / methods*

- Hospital Planning / statistics & numerical data

- Hospitals, Community / organization & administration*

- Leadership*

- Medical Staff, Hospital

- Organizational Case Studies

- Planning Techniques*

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2020

An analysis of the strategic plan development processes of major public organisations funding health research in nine high-income countries worldwide

- Cristina Morciano 1 ,

- Maria Cristina Errico 1 ,

- Carla Faralli 2 &

- Luisa Minghetti 1

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 18 , Article number: 106 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

9 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

There have been claims that health research is not satisfactorily addressing healthcare challenges. A specific area of concern is the adequacy of the mechanisms used to plan investments in health research. However, the way organisations within countries devise research agendas has not been systematically reviewed. This study seeks to understand the legal basis, the actors and the processes involved in setting research agendas in major public health research funding organisations.

We reviewed information relating to the formulation of strategic plans by 11 public funders in nine high-income countries worldwide. Information was collected from official websites and strategic plan documents in English, French, Italian and Spanish between January 2019 and December 2019, by means of a conceptual framework and information abstraction form.

We found that the formulation of a strategic plan is a common and well-established practice in shaping research agendas across international settings. Most of the organisations studied are legally required to present a multi-year strategic plan. In some cases, legal provisions may set rules for actors and processes and may establish areas of research and/or types of research to be funded. Commonly, the decision-making process involves both internal and external stakeholders, with the latter being generally government officials and experts, and few examples of the participation of civil society. The process also varies across organisations depending on whether there is a formal requirement to align to strategic priorities developed by an overarching entity at national level. We also found that, while actors and their interactions were traceable, information, sources of information, criteria and the mechanisms/tools used to shape decisions were made less explicit.

Conclusions

A complex picture emerges in which multiple interactive entities appear to shape research plans. Given the complexity of the influences of different parties and factors, the governance of the health research sector would benefit from a traceable and standardised knowledge-based process of health research strategic planning. This would provide an opportunity to demonstrate responsible budget stewardship and, more importantly, to make efforts to remain responsive to healthcare challenges, research gaps and opportunities.

Peer Review reports

Advances in scientific knowledge have contributed greatly to improvements in healthcare, but there have been claims that health research is not adequately addressing healthcare challenges. These concerns are reflected in the increasing debate over the adequacy of the mechanisms used to plan investment in health research and ensure its optimal distribution [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Over recent decades, methods and tools have been produced in order to guide the process of setting the health research agenda and facilitate more explicit and transparent judgment regarding research priorities. There is no single method that is considered appropriate for all settings and purposes, yet it is recognised that their optimal application requires a knowledge of health needs, research gaps and the perspectives of key stakeholders [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

A number of studies have described initiatives to set health research agendas. Several articles refer to experiences focusing on specific health conditions, for example, those undertaken under the framework of the James Lind Alliance [ 11 ]. There are also reviews of disparate examples of research agenda-setting in low- and middle-income countries [ 12 , 13 ] as well as in high-income countries (HICs) [ 14 ]. These initiatives were highly heterogeneous with regard to their promotor (public organisations, academics, advocacy groups, etc.), the level of the research system (global, regional, national, sub-national, organisational or sub-organisational) and the scope of the prioritisation process (broad themes or specific research questions).

However, there are no studies that have specifically investigated the way large public organisations in HICs devise their research agendas and to what extent this is linked to regulations and organisational setup. In 2016, Moher et al. reported on how research funders had addressed recommendations to increase value and reduce waste in biomedical research [ 15 ]. Within this framework, they provided a general overview of setting the overall agenda in a convenient sample of six public funders of health research. They also affirmed the need for a “ periodic survey of information on research funders’ websites about their principle and methods used to decide what research to support ” [ 15 ]. At the same time, Viergever et al. identified the 10 largest funders of health research in the world and recommended further study of their priority-setting processes [ 16 ].

Given this context, we wished to provide an updated and thorough description of the way public funders of research in HICs devise their research agenda. We therefore analysed the regulatory framework for the actors and processes involved in developing the strategic plan in 11 major English and non-English speaking public research funders across 9 HICs worldwide.

Strategic planning

Our analysis focused on the development of the strategic plan, or strategic planning, at organisational level as a crucial step in the setting of the research agenda by the organisation. By the term ‘setting the research agenda’, we meant the whole-organisation research management planning cycle, which may encompass multiple decision-making level (organisational, sub-organisational, research programme level, etc.) actors and funding flows.

Strategic planning has been defined in social science as a “ deliberative, disciplined effort to produce fundamental decisions and actions that shape and guide what an organization (or other entity) is, what it does, and why ” [ 17 ].

The strategic plan is assumed to be the final outcome of the strategic planning process, in which priority-setting is the key milestone. It is therefore expected that the research priorities of the organisation will be included. Depending on mandate, priorities could be related to research topics (e.g. health conditions or diseases), types of research (e.g. basic or clinical) and/or other planned initiatives (e.g. workforce or research integrity).

The choice to focus on strategic planning was also guided by the fact that it is known from social science that strategic planning is a well-established practice within public organisations worldwide [ 17 , 18 ]. This would enable us to ensure comparability of information on modalities of decision-making in research planning across organisations from different countries.

Selection of public organisations

We created a list of public funders of health research, drawing from a previous study in which the authors identified 55 public and philanthropic organisations and listed them according to their annual expenditure on health research [ 16 ]. In order to strike a balance between learning about the practices of health research funders, and keeping data collection feasible and manageable, we restricted our sample to two organisations per country, with health research budgets of more than 200 million USD annually. In doing so, we identified a manageable subsample of 35 organisations having the greatest potential influence on research agendas, both locally and globally, and representing different health research systems in different countries.

We based our overview on publicly available information and restricted our sample to those organisations with published strategic research plans in English, French, Italian or Spanish (Additional file 1 ).

Information search and abstraction

Since we expected processes to vary across organisations, we did not use guidelines or best practices for strategic planning, which allowed us to document a wide range of experiences. As mentioned earlier, we based this overview on the collection of publicly available information by means of a conceptual framework and an information abstraction form (Box 1 , Additional file 1 ).

We based the conceptual framework on Walt and Gilson’s policy analysis model [ 19 ] and the information that could actually be retrieved after an initial assessment of the available information. The conceptual framework and the data abstraction form were conceived in an effort to (1) standardise the search for and collection of information across organisations, (2) render the collection process more transparent, and (3) make the retrieved information more understandable to readers.

Three authors (CM, CF and MCE) performed the review of information and the compilation of the form independently, with differences of opinion resolved by discussion. Information was collected in duplicate from 1 January 2019 to 31 July 2019. Before submitting the article, we updated the information by accessing and reviewing the official websites of the included organisations until 10 December 2019.

We searched for information that answered our questions by (1) browsing the funding organisations’ official websites and following links providing information about the organisations, e.g. Who we are, About us, Mission, Laws and statutes, Funding opportunities and other similar web pages, and by (2) identifying and reviewing strategic plans. When an organisation was composed of multiple sub-organisations, we limited our analysis to the strategic planning of the overarching organisation.

A second phase of research consisted of producing a profile for each organisation according to the data extraction form (Additional file 1 ). Bearing in mind that the results of this analysis could have been very general, we also used two organisations as case studies to provide more detailed examples of planning and implementing research priorities at the organisational level. We accessed and reviewed the official websites of the case study organisations until 14 April 2020. We did not contact organisations directly to obtain additional information. After collecting and analysing the information, we produced a narrative overview of our findings.

Box 1 Conceptual framework

Organisation profile

This section describes the funding organisation and its role and relationship with other overarching governmental bodies.

What are the contents of the strategic plan?

This section examines the publicly available strategic plan of the funding organisation. The strategic plan is assumed to be the final outcome of the strategic planning process and includes the research priorities of the organisation. Depending on the mandate of the organisation, the research priorities are those related to research topics (for example, health conditions/diseases), types of research (for example, basic research, clinical research) and/or other planned initiatives within the mandate of the organisation (e.g. workforce, research integrity).

Regulatory basis

This part seeks to understand if there is an official basis for strategic planning, for example, a law or a government document that establishes processes and actors for setting priorities.

What are the process and tools of strategic planning?

This section seeks to describe the processes and tools for identifying the research priorities included in the strategic plan, including whether or not there are explicit mechanisms, criteria, instruments and information to guide and inform the process of strategic planning such as a research landscape analysis or a more structured experience of priority-setting.

Who are the actors involved?

This section examines who the involved actors are in preparing the strategic plan; for example, who coordinates the process and who is involved in the process (e.g. clinicians, patients, citizens, researchers) and how the organisation relates with other entities in preparing the strategic plan.

Included organisations

We included 11 public organisations with a publicly available strategic plan in English, Spanish, French or Italian (Additional file 1 ). There were two from the United States, two from France, and one each from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Japan, Italy, Spain and Singapore. The mandates of the organisations were diverse – some had the task of funding research and other activities in support of health research, while others were involved in both funding and conducting health research (Table 1 ).

The strategic plan: format and content

The strategic plans varied in format (Additional file 1 ). While some organisations indicated broad lines of research, others structured their strategic plan in a complex hierarchy with high-level priorities connected to goals and sub-goals. In some cases, indicators, or menus of indicators, were added to monitor progress of the planned work and/or assess the impact of the research. In some research plans, the type of research funding (e.g. responsive, commissioned, research training) and budget were explicitly linked to research priorities.

With regard to content, some organisations focused their strategy on supporting the production of new knowledge of specific diseases or conditions. Others prepared a comprehensive strategy to support different functions of the health research system, such as producing knowledge, sustaining the workforce and infrastructure, developing policies for research integrity and conceiving processes for making more informed decisions. Some strategic plans briefly described the research environment at the national, organisational or programme level. One organisation described the process used to develop health research priorities.

Most of the organisations are legally required to present a multi-year strategic plan or at least annual research priorities. In addition, legislation sets rules and procedures by covering subjects such as the actors to be involved, the documents to be consulted and the format of the strategic plan document to be adopted. In some cases, legal provisions indicate areas and/or types of research to be funded (Table 1 ).

Commonly, the main actors are the top-level policy-makers of the organisations. A spectrum of external stakeholders from multiple sectors may be involved and their participation varies across organisations. External stakeholders can be members of academia or government research agencies, or industry professionals and policy-makers. Most frequently, they have a membership role in organisational governing bodies (boards and committees) (Table 1 ).

The government maintains a role in shaping the strategic plan to various extents in different organisations. This may involve producing nationwide strategic plans for research that the organisations have to adopt or align to, directing attention to specific research priorities or types of research, having representatives in the governing bodies of the organisations and retaining the power of final approval of the organisations’ strategic plans (Table 1 ). Other actors involved are overarching government agencies, which play a role in managing or coordinating the research plan at the national level. Examples of this are the Spanish National Research Agency and United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI). When this study was being conducted, the latter had just been established and been given the role of developing a coherent national research strategy.

The participation of civil society in governing bodies, temporary committees or consultation exercises was far less common. There are representatives of the public in the advisory bodies of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; e.g. the Advisory Committee to the Director).

The Chief Executive Officer of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), acting under the terms of the NHMRC Act, established the Community and Consumer Advisory Group. This is a working committee whose function is to provide advice on health questions and health and medical research matters, from consumer and community perspectives. Most notably, the United States Department of Defense – Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (DoD-CDMRP) involve consumers (patients, their representatives and caregivers) at all levels of the funding process, from strategic planning to the peer-review process of research proposals. Organisations also have external consultation exercises, in which the target audiences and mechanisms implemented vary (Table 1 ).

In order to illustrate the interactions between different actors, we identified two broad categories of organisation. The first comprises those organisations that develop their own plans with a certain degree of independence. Government and legal provisions might provide some direction. In this group are the NIH, the Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm), the Italian Ministry of Health (MoH), the NHMRC, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Medical Research Council (MRC), the DoD-CDMRP, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (Table 1 ).

The second category is made up of those organisations whose research planning derives from the strategic plan of an overarching entity. In this group are the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the National Medical Research Council (NMRC) and the MRC. Both categories are represented in the case studies below.

An example of the first category from the United States is the 5-year strategic plan, NIH-Wide Strategic Plan, Fiscal Years 2016–2020: Turning Discovery Into Health, developed by the NIH at the request of Congress. Legislation provides direction on some criteria for setting priorities in the plan, but it is the NIH Director who develops it in consultation with internal (Centres, Institutes and Offices) and external stakeholders (see the NIH case study).

In Australia, the Chief Executive Officer of the NHMRC identifies major national health issues likely to arise during the 4-year period covered by the plan and devises the strategy in consultation with the Minister for Health and the NHMRC governing bodies. The Minister provides guidance on the NHMRC’s strategic priorities and approves or revises the plan. In Canada, the governing bodies of the CIHR are responsible for devising the strategic plan. The Deputy Minister of the Department of Health participates as a non-voting member of one of the governing bodies.

The common characteristic of the second category is that the process of strategic planning derives from one or more overarching entities. This means that the strategic plans of the organisations are informed to various extents by the research programmes of such an entity or entities. In some cases, there is a main institution with research coordination and/or management roles at the national level. For example, in Spain, in order to inform funding grants, the ISCIII adopted the research priorities set out in the Strategic Action for Health included in the State Plan for Science, Innovation and Technology 2017–2020 . This plan, elaborated by the Government Delegated Committee for the Policies for Research, Technology and Innovation ( la Comisión Delegada del Gobierno para Política Scientífica, Tecnológica y de Innovación ), in cooperation with the Ministry of Fianance, is aligned with the four strategic objectives of the Spanish Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation 2013–2020. The newly established Spanish State Research Agency ( Agencia Estatal de Investigacion ) also participated in the development of the State Plan. However, its role is mainly in monitoring the plan’s funding, including ISCIII funding for the Strategic Action for Health.

UKRI, sponsored by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, is the body responsible for the development of a coherent national research strategy that balances the allocation of funding across different disciplines. In 2018, the MRC became a committee body of UKRI, alongside eight other committees, called ‘Councils’, which represent various research sectors. The MRC is required to develop a strategic plan that is coherent with the strategic objectives set by UKRI. This plan must be approved by the UKRI Board, the governing body responsible for ensuring that Council plans are consistent with the UKRI strategy.

In Singapore, the NMRC refers to the strategic plan developed by the National Research Foundation, a department within the Prime Minister’s Office. The NMRC has a well-described system for incorporating national priorities into the organisation’s research plan (see the NMRC case study).

With regard to the information, sources of information, criteria and mechanisms used to shape decisions, the included organisations were less explicit. Most commonly, organisations introduced health research priorities with an overview of major general advancements in biomedical research or a catalogue of organisational activities and a research portfolio.

A small number of organisations presented a brief situational analysis of the health and health research sectors. In these cases, the scope and nature of the presented information varied from one organisation to another (Additional file 1 ).

For example, the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan contains a brief summary of the state of research at the organisational level. The plans of each DoD-CDMRP health research programme present a summary of both the current health and health research landscapes at the national level.

Other organisations stated that the plan had been supported by information analysis of the research field, but they did not report explicitly on this work.

Case studies

The national institutes of health (nih).

The NIH is an operating division of the United States Department of Health and Human Services whose mission is to improve public health by conducting and funding basic and translational biomedical research. It is made up of 27 theme-based Institutes, Centers and Offices, each of which develops an individual strategic plan [ 20 ].

The first 5-year strategic plan, NIH-Wide Strategic Plan, Fiscal Years 2016–2020: Turning Discovery into Health, was prepared at the request of Congress and published in 2016 [ 21 ]. The legal framework stipulates that the NIH-coordinated strategy will inform the individual strategic plans of the Institutes and Centers. In addition, it provides some direction regarding content and the process to be adopted for generating the overall NIH strategy [ 22 , 23 ]. For example, it sets out specific requirements for the identification of research priorities. These include “ an assessment of the state of biomedical and behavioural research ” and the consideration of “ (i) disease burden in the United States and the potential for return on investment to the United States; (ii) rare diseases and conditions; (iii) biological, social, and other determinants of health that contributes to health disparities; and (iv) other factors the Director of National Institutes of Health determines appropriate ” [ 23 ]. The NIH Director is also required to consult “ with the directors of the national research institutes and national centers, researchers, patient advocacy groups and industry leaders ” [ 23 ]. To fulfil the request of Congress, the NIH Director and the Principal Deputy Director initiated the process by creating a draft ‘framework’ for the strategic plan. This framework was designed with the purposes of identifying major areas of research that cut across NIH priorities and of setting out principles to guide the NIH research effort (‘unifying principles’).

The development of the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan involved extensive internal and external consultations throughout the process. Consultees included the ad hoc NIH-Wide Strategic Plan Working Group, composed of representatives of all 27 Institutes, Centers and Offices, the Advisory Committee to the Director, which is an NIH standing committee of experts in research fields relevant to the NIH mission, and representatives of the research community (from academia and the private sector) and the general public. The framework was also presented at meetings with the National Advisory Councils of the Institutes and Centers.

In addition, the framework was disseminated to external stakeholders for comments and suggestions, which were solicited via a series of public webinars and through the initiative Request for Information: Inviting Comments and Suggestions on a Framework for the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan. In this case, a web-based form collected comments and suggestions on a predefined list of topic areas from a wide array of stakeholders representative of patient advocacy organisations, professional associations, private hospitals and companies, academic institutions, government and private citizens [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. A report on the analysis of the public comments is publicly available [ 27 ].

The National Medical Research Council (NMRC)

The NMRC is the organisation that has the role of promoting, coordinating and funding biomedical research in Singapore [ 28 ]. It has developed its own research strategy by adopting the research priorities indicated by the national research strategy in the domain of health and biomedical sciences [ 29 ].

The national research strategy is the responsibility of the National Research Foundation, a department of the Prime Minister’s Office. It defines broad research priorities relating to various areas of research identified as ‘domains’. Within the health and biomedical sciences domain, five areas of research have been proposed with input from the Ministry of Health and the Health and Biomedical Sciences International Advisory Council. These are cancer, cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases, neurological and sense disorders, diabetes mellitus and other metabolic/endocrine conditions. Criteria for selection of the areas of focus were “ disease impact, scientific excellence in Singapore and national needs ” [ 29 ].

The approach of NMRC to implementing the national research strategy at organisational level involves the establishment of ‘task forces’, i.e. groups of experts, with the role of defining the specific research strategy for each of the five areas of focus. Each task force provides documentation of research recommendations and methods used to prioritise research topics [ 30 ].

For example, the Neurological and Sense Disorders Task Force identified sub-areas of research Footnote 1 after analysing the local burden of neurological and sense disorders as well as considering factors such as local scientific expertise and research talent, ongoing efforts in neurological and sense disorders, industry interest, and opportunities for Singapore. As part of the effort, input was also solicited from the research community and policy-makers. This research prioritisation exercise served for both the NMRC grant scheme and a 10-year research roadmap [ 31 ].

Our study is the first to report on the processes used by a set of large national public funders to develop health research strategic plans. In line with findings from public management literature [ 16 , 17 ], we found that the formulation of a strategic plan is a well-established practice in shaping research agendas across international settings and it is a legal requirement for the majority of the organisations we studied.

We were able to reconstruct the process for developing the strategic plan by identifying the main actors involved and how they are connected. A complex picture emerges, in which multiple interactive entities and forces, often organised in a non-linear dynamic, appear to shape the research plans. In general, an organisation has to take into account legislative provisions, government directives, national overall research plans, national health plans and specific disease area plans. In some cases, it has to consider ‘institutionalised’ allocation of resources across organisations’ sub-entities (institutes, centres and units), which are historically associated with a particular disease or type of research.

On the other hand, we found little documentation of the decision-making mechanisms and information used to inform decision-making. There were, for example, few references to health research needs, research capabilities, the sources of information consulted, and the principles and criteria applied. This despite the increasing attention being paid nationally and internationally to the need for an explicit evidence-based or rational approach to setting health research priorities, particularly in the light of current economic constraints [ 3 , 32 , 33 ]. Given the complexity of the influences of different parties and factors, the governance of the health research sector would benefit from a traceable knowledge-based process of strategic planning, similar to that advocated for the health sector [ 34 ].

We found, however, evidence of an increasing interest in improving ways to establish research priorities at the organisational level. For example, NIH has brought forward the Senate request to develop a coordinated research strategy by including, in the strategic plan, the intention to further improve the processes for setting NIH research priorities and to optimise approaches to making informed funding decisions [ 21 ].

Recently, the DoD-CDMRP, the second largest funder of health research in the United States, reviewed its research management practices upon the recommendations of an ad hoc committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. In the area of strategic planning, the committee recommended an analysis of the funding landscape across different agencies and organisations, the identification of short- and long-term research needs, and harmonisation with the research priorities of other organisations [ 35 ].

In its strategic plan, the JSPS has placed particular emphasis on the development of research-on-research capacity and infrastructures to analyse the research landscape at organisational, national and international levels in order to ensure that funding decisions are evidence based [ 36 ].

The allocation of sufficient resources to develop the infrastructure and technical expertise required for collection, analysis and dissemination of a portfolio of relevant data should be considered a necessary step when a funding organisation or country decides to implement standardised approaches for strategic planning and priority-setting.

Additionally, from the perspective of health research as a system, data collection and analyses should not be limited to ‘what is funded’, but should also include ‘who is funded and where’, and be linked to research policies and their long-term outcomes. The benefit of such an approach is not limited to the prevention of unnecessary duplication of research. Support would also be provided for producing formal mechanisms to coordinate research effort across research entities, within and among countries. Collaborations with other non-profit as well as for-profit organisations would be promoted and the capacity for research would be created and strengthened where necessary.

A number of resources and initiatives in this field already exist at organisational and national level. For example, the NIH has the Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools, a public repository of data and other tools from NIH research activities [ 37 ]. This repository is linked to Federal RePORTER, an infrastructure that makes data on federal investments in science available. In the United Kingdom, the Health Research Classification System performs regular analysis of the funding landscape of United Kingdom health research to support monitoring, strategy development and coordination [ 38 ].

At the international level, there is ongoing global work to shape evidence-based health research decisions and coordination. In 2013, the WHO Global Observatory on Health R&D was established “ in order to monitor and analyze relevant information on health research and development, […] with a view to contributing to the identification of gaps and opportunities for health research and development and defining priorities […] and to facilitate the development of a global shared research agenda ” [ 33 ]. This effort has been coupled with a global call to action, which asks governments to create or strengthen national health research observatories and contribute to the WHO Observatory. Furthermore, the Clinical Research Initiative for Global Health, a consortium of research organisations across the world, has ongoing projects that will map clinical research networks and funding capacity and conduct clinical research at a global level [ 39 ].

A further key area that deserves comment is the engagement of stakeholders. In general, a spectrum of external stakeholders from multiple sectors is involved and the extent of this involvement varies across organisations. Decision-making processes commonly include people from government bodies, academia, research agencies and industry. However, we found that the participation of civil society, here represented by the intended beneficiaries of research such as health professionals, patients and their carers, remains limited. The fact that decision-making is still the domain of government officials and experts is an unexpected finding. There is a widespread consensus that the participation of a mix of stakeholders can improve the process of strategic planning. The logic behind this is that representatives of those who are affected by decisions can bring new information and perspectives and improve the effectiveness of the process [ 17 , 32 , 40 ]. Broader inclusion is desirable, both for granting legitimacy to strategic planning and for advancing equity in healthcare. Decisions on research priorities shape knowledge and, ultimately, they determine whether patients and their carers will have access to healthcare options that meet their needs [ 41 ].

Additionally, our study shows that the involvement of civil society is not only desirable but is also feasible. Organisations that support the participation of civil society have this practice firmly embedded in their governance, although it may be implemented in different ways.

Strengths and limitations

A particular strength of our study is the innovative way in which we approached the disorienting complexity of whole-organisation planning cycle management. This allowed us to contribute to an understanding of the processes used by large public funders not only in English-speaking countries but also in France, Italy and Spain.