- Annual Emerging Poets Slam 2023

- Poems About the Pandemic Generation Slam

- Slam on AI - Programs or Poems?

- Slam on Gun Control

- Poet Leaderboard

- Poetry Genome

- What are groups?

- Browse groups

- All actions

- Find a local poetry group

- Top Poetry Commenters

- AI Poetry Feedback

- Poetry Tips

- Poetry Terms

- Why Write a Poem

- Scholarship Winners

6 Tips for Using Poetry in a Speech

The term “public speaking” may be defined as relaying information to a group of people in a structured, deliberate manner intended to inform, influence, or entertain the listeners. People may choose to give a speech in order to transmit information, motivate people to act, or simply to tell a story. A good orator should be able to change the emotions of their listener and not just inform them. Hey, we get it. Writing a speech on top of actually performing it in public can be super scary and intimidating, but it gets easier once you think of a speech as an epic spoken word poem. Check out our tip guide for getting over some of those spoken word nerves. Most speeches actually use the same literary devices you already use in tons of your poetry. Think of John F. Kennedy’s inaugural speech: “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country” (why hello there, chiasmus). Now, don’t you feel better? By using the boss poet skills you already have, you can create a speech with descriptive and moving language that really entices your listeners. Keep on reading to find out how to write a speech that grabs your listeners and holds their attention.

- Why Do I Have to Write This Thing Anyway? Think about the atmosphere of the occasion at which you’ll present your speech. This will affect the style and tone of your words, just like in a poem (example: a political poem would use a much more serious tone than a poem about a funny memory between you and your best friend). Also pay attention to your audience. For example, a wedding is an event that occurs frequently but no two weddings are exactly alike. This is because different guests with varying personalities attend each one. So, if you were to write a wedding speech, you’d tailor it to match the specific personalities of the couple as well as the guests. Use your poet’s intuition to choose which literacy devices you think everyone will best respond to.

- Use Metaphors and Similes. Ah, oldies but goodies. A metaphor is a stylistic device that assigns the characteristics of one thing to another. For example, in his famous "I Have a Dream" speech, when Martin Luther King described Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation as, "a great beacon light of hope for millions of Negro slaves," he used a metaphor to imply that the Emancipation Proclamation had the attributes of a shining beacon light. A simile is a literary device that compares two unlike things using the words “like” or “as.” If King had said the Emancipation Proclamation was " like a great beacon light of hope," he would have been using a simile. Metaphors and similes are elegant ways of saying something-- and listeners respond well to this type of fancy language that’s also easy to understand.

- Describe, Describe, Describe! Appeal to your listeners' senses by using concrete, vividly descriptive language. Let’s look at this in action. In a famous nineteenth-century murder case, the senator and powerful orator Daniel Webster recreated the murder scene in the minds of the jurors with expressive descriptions: "The room is uncommonly open to the admission of light. The face of the innocent sleeper is turned from the murderer, and the beams of the moon, resting on the gray locks of his aged temple, show him where to strike. The fatal blow is given!" By honing your ability to create intense imagery, you can entice your listeners to use all five of their senses and make your speech that much more impressive .

- This Isn’t an Essay for School-- Go Ahead and Repeat Yourself . Repetition is when a word or phrase is used more than once. In a speech, repetition forces the attention of your audience, quickens the pace of your words, and creates an insistent rhythm. Consider this famous example uttered by Winston Churchill during World War Two: "We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing-grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills." Bet’cha the next thought in your head is “we shall…” See, it totally works! Repetition helps to drill key words and ideas into your listeners’ minds so that they remember the most important sections of your speech.

- Practice your Delivery and Be CONFIDENT . If you’re confident when speaking and passionate about your speech topic, it will definitely come across as powerful in your delivery. Read your speech quietly aloud to yourself, listening for its musicality or beat. Then, start over again but a little louder. Each time you read your speech out loud, increase your volume. It might sound silly screaming your speech, but it’ll definitely help with your confidence and once it’s time to perform it for real, speaking at a normal yet assertive register will be a piece of cake. Familiarize yourself with the core ideas and images in your speech. The more you understand the speech, the more likely your audience will understand it and respond to the points you are trying to get across. The more strongly you identify with your work the easier it will be for your audience to follow.

- Power Poetry . Now that you’re more familiar with how to write a speech using poetic elements, it’s time to test it out. The ability to read your written work aloud is a gift of immense value because it expresses with grace and clarity thoughts and feelings that are often difficult to find appropriate words for in ordinary prose. Share your poetic speech with Power Poetry and better yet, record yourself so that you can see how much your hard work paid off!

Related Poems

Create a poem about this topic

- Join 230,000+ POWER POETS!

- Request new password

To learn how to write a poem step-by-step, let’s start where all poets start: the basics.

This article is an in-depth introduction to how to write a poem. We first answer the question, “What is poetry?” We then discuss the literary elements of poetry, and showcase some different approaches to the writing process—including our own seven-step process on how to write a poem step by step.

So, how do you write a poem? Let’s start with what poetry is.

What Poetry Is

It’s important to know what poetry is—and isn’t—before we discuss how to write a poem. The following quote defines poetry nicely:

“Poetry is language at its most distilled and most powerful.” —Former US Poet Laureate Rita Dove

Poetry Conveys Feeling

People sometimes imagine poetry as stuffy, abstract, and difficult to understand. Some poetry may be this way, but in reality poetry isn’t about being obscure or confusing. Poetry is a lyrical, emotive method of self-expression, using the elements of poetry to highlight feelings and ideas.

A poem should make the reader feel something.

In other words, a poem should make the reader feel something—not by telling them what to feel, but by evoking feeling directly.

Here’s a contemporary poem that, despite its simplicity (or perhaps because of its simplicity), conveys heartfelt emotion.

Poem by Langston Hughes

I loved my friend. He went away from me. There’s nothing more to say. The poem ends, Soft as it began— I loved my friend.

Poetry is Language at its Richest and Most Condensed

Unlike longer prose writing (such as a short story, memoir, or novel), poetry needs to impact the reader in the richest and most condensed way possible. Here’s a famous quote that enforces that distinction:

“Prose: words in their best order; poetry: the best words in the best order.” —Samuel Taylor Coleridge

So poetry isn’t the place to be filling in long backstories or doing leisurely scene-setting. In poetry, every single word carries maximum impact.

Poetry Uses Unique Elements

Poetry is not like other kinds of writing: it has its own unique forms, tools, and principles. Together, these elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

The elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

Most poetry is written in verse , rather than prose . This means that it uses line breaks, alongside rhythm or meter, to convey something to the reader. Rather than letting the text break at the end of the page (as prose does), verse emphasizes language through line breaks.

Poetry further accentuates its use of language through rhyme and meter. Poetry has a heightened emphasis on the musicality of language itself: its sounds and rhythms, and the feelings they carry.

These devices—rhyme, meter, and line breaks—are just a few of the essential elements of poetry, which we’ll explore in more depth now.

Understanding the Elements of Poetry

As we explore how to write a poem step by step, these three major literary elements of poetry should sit in the back of your mind:

- Rhythm (Sound, Rhyme, and Meter)

- Literary Devices

1. Elements of Poetry: Rhythm

“Rhythm” refers to the lyrical, sonic qualities of the poem. How does the poem move and breathe; how does it feel on the tongue?

Traditionally, poets relied on rhyme and meter to accomplish a rhythmically sound poem. Free verse poems—which are poems that don’t require a specific length, rhyme scheme, or meter—only became popular in the West in the 20th century, so while rhyme and meter aren’t requirements of modern poetry, they are required of certain poetry forms.

Poetry is capable of evoking certain emotions based solely on the sounds it uses. Words can sound sinister, percussive, fluid, cheerful, dour, or any other noise/emotion in the complex tapestry of human feeling.

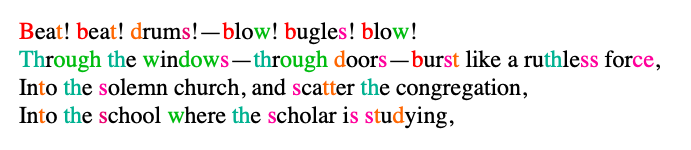

Take, for example, this excerpt from the poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” by Walt Whitman:

Red — “b” sounds

Blue — “th” sounds

Green — “w” and “ew” sounds

Purple — “s” sounds

Orange — “d” and “t” sounds

This poem has a lot of percussive, disruptive sounds that reinforce the beating of the drums. The “b,” “d,” “w,” and “t” sounds resemble these drum beats, while the “th” and “s” sounds are sneakier, penetrating a deeper part of the ear. The cacophony of this excerpt might not sound “lyrical,” but it does manage to command your attention, much like drums beating through a city might sound.

To learn more about consonance and assonance, euphony and cacophony, and the other uses of sound, take a look at our article “12 Literary Devices in Poetry.”

https://writers.com/literary-devices-in-poetry

It would be a crime if you weren’t primed on the ins and outs of rhymes. “Rhyme” refers to words that have similar pronunciations, like this set of words: sound, hound, browned, pound, found, around.

Many poets assume that their poetry has to rhyme, and it’s true that some poems require a complex rhyme scheme. However, rhyme isn’t nearly as important to poetry as it used to be. Most traditional poetry forms—sonnets, villanelles , rimes royal, etc.—rely on rhyme, but contemporary poetry has largely strayed from the strict rhyme schemes of yesterday.

There are three types of rhymes:

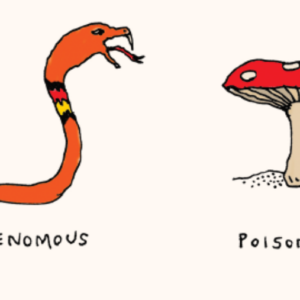

- Homophony: Homophones are words that are spelled differently but sound the same, like “tail” and “tale.” Homophones often lead to commonly misspelled words .

- Perfect Rhyme: Perfect rhymes are word pairs that are identical in sound except for one minor difference. Examples include “slant and pant,” “great and fate,” and “shower and power.”

- Slant Rhyme: Slant rhymes are word pairs that use the same sounds, but their final vowels have different pronunciations. For example, “abut” and “about” are nearly-identical in sound, but are pronounced differently enough that they don’t completely rhyme. This is also known as an oblique rhyme or imperfect rhyme.

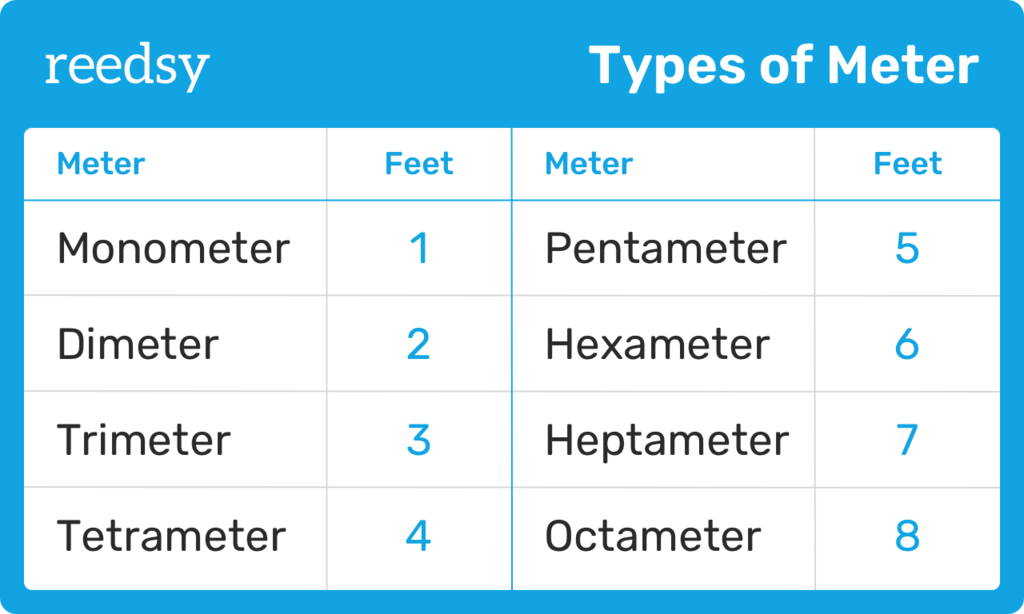

Meter refers to the stress patterns of words. Certain poetry forms require that the words in the poem follow a certain stress pattern, meaning some syllables are stressed and others are unstressed.

What is “stressed” and “unstressed”? A stressed syllable is the sound that you emphasize in a word. The bolded syllables in the following words are stressed, and the unbolded syllables are unstressed:

- Un• stressed

- Plat• i• tud• i•nous

- De •act•i• vate

- Con• sti •tu• tion•al

The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is important to traditional poetry forms. This chart, copied from our article on form in poetry , summarizes the different stress patterns of poetry.

2. Elements of Poetry: Form

“Form” refers to the structure of the poem. Is the poem a sonnet, a villanelle, a free verse piece, a slam poem, a contrapuntal, a ghazal , a blackout poem , or something new and experimental?

Form also refers to the line breaks and stanza breaks in a poem. Unlike prose, where the end of the page decides the line breaks, poets have control over when one line ends and a new one begins. The words that begin and end each line will emphasize the sounds, images, and ideas that are important to the poet.

To learn more about rhyme, meter, and poetry forms, read our full article on the topic:

https://writers.com/what-is-form-in-poetry

3. Elements of Poetry: Literary Devices

“Poetry: the best words in the best order.” — Samuel Taylor Coleridge

How does poetry express complex ideas in concise, lyrical language? Literary devices—like metaphor, symbolism, juxtaposition, irony, and hyperbole—help make poetry possible. Learn how to write and master these devices here:

https://writers.com/common-literary-devices

How to Write a Poem, in 7 Steps

To condense the elements of poetry into an actual poem, we’re going to follow a seven-step approach. However, it’s important to know that every poet’s process is different. While the steps presented here are a logical path to get from idea to finished poem, they’re not the only tried-and-true method of poetry writing. Poets can—and should!—modify these steps and generate their own writing process.

Nonetheless, if you’re new to writing poetry or want to explore a different writing process, try your hand at our approach. Here’s how to write a poem step by step!

1. Devise a Topic

The easiest way to start writing a poem is to begin with a topic.

However, devising a topic is often the hardest part. What should your poem be about? And where can you find ideas?

Here are a few places to search for inspiration:

- Other Works of Literature: Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it’s part of a larger literary tapestry, and can absolutely be influenced by other works. For example, read “The Golden Shovel” by Terrance Hayes , a poem that was inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We Real Cool.”

- Real-World Events: Poetry, especially contemporary poetry, has the power to convey new and transformative ideas about the world. Take the poem “A Cigarette” by Ilya Kaminsky , which finds community in a warzone like the eye of a hurricane.

- Your Life: What would poetry be if not a form of memoir? Many contemporary poets have documented their lives in verse. Take Sylvia Plath’s poem “Full Fathom Five” —a daring poem for its time, as few writers so boldly criticized their family as Plath did.

- The Everyday and Mundane: Poetry isn’t just about big, earth-shattering events: much can be said about mundane events, too. Take “Ode to Shea Butter” by Angel Nafis , a poem that celebrates the beautiful “everydayness” of moisturizing.

- Nature: The Earth has always been a source of inspiration for poets, both today and in antiquity. Take “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver , which finds meaning in nature’s quiet rituals.

- Writing Exercises: Prompts and exercises can help spark your creativity, even if the poem you write has nothing to do with the prompt! Here’s 24 writing exercises to get you started.

At this point, you’ve got a topic for your poem. Maybe it’s a topic you’re passionate about, and the words pour from your pen and align themselves into a perfect sonnet! It’s not impossible—most poets have a couple of poems that seemed to write themselves.

However, it’s far more likely you’re searching for the words to talk about this topic. This is where journaling comes in.

Sit in front of a blank piece of paper, with nothing but the topic written on the top. Set a timer for 15-30 minutes and put down all of your thoughts related to the topic. Don’t stop and think for too long, and try not to obsess over finding the right words: what matters here is emotion, the way your subconscious grapples with the topic.

At the end of this journaling session, go back through everything you wrote, and highlight whatever seems important to you: well-written phrases, poignant moments of emotion, even specific words that you want to use in your poem.

Journaling is a low-risk way of exploring your topic without feeling pressured to make it sound poetic. “Sounding poetic” will only leave you with empty language: your journal allows you to speak from the heart. Everything you need for your poem is already inside of you, the journaling process just helps bring it out!

Learn more about keeping a daily journal here:

How to Start Journaling: Practical Advice on How to Journal Daily

3. Think About Form

As one of the elements of poetry, form plays a crucial role in how the poem is both written and read. Have you ever wanted to write a sestina ? How about a contrapuntal, or a double cinquain, or a series of tanka? Your poem can take a multitude of forms, including the beautifully unstructured free verse form; while form can be decided in the editing process, it doesn’t hurt to think about it now.

4. Write the First Line

After a productive journaling session, you’ll be much more acquainted with the state of your heart. You might have a line in your journal that you really want to begin with, or you might want to start fresh and refer back to your journal when you need to! Either way, it’s time to begin.

What should the first line of your poem be? There’s no strict rule here—you don’t have to start your poem with a certain image or literary device. However, here’s a few ways that poets often begin their work:

- Set the Scene: Poetry can tell stories just like prose does. Anne Carson does just this in her poem “Lines,” situating the scene in a conversation with the speaker’s mother.

- Start at the Conflict: Right away, tell the reader where it hurts most. Margaret Atwood does this in “Ghost Cat,” a poem about aging.

- Start With a Contradiction: Juxtaposition and contrast are two powerful tools in the poet’s toolkit. Joan Larkin’s poem “Want” begins and ends with these devices. Carlos Gimenez Smith also begins his poem “Entanglement” with a juxtaposition.

- Start With Your Title: Some poets will use the title as their first line, like Ron Padgett’s poem “Ladies and Gentlemen in Outer Space.”

There are many other ways to begin poems, so play around with different literary devices, and when you’re stuck, turn to other poetry for inspiration.

5. Develop Ideas and Devices

You might not know where your poem is going until you finish writing it. In the meantime, stick to your literary devices. Avoid using too many abstract nouns, develop striking images, use metaphors and similes to strike interesting comparisons, and above all, speak from the heart.

6. Write the Closing Line

Some poems end “full circle,” meaning that the images the poet used in the beginning are reintroduced at the end. Gwendolyn Brooks does this in her poem “my dreams, my work, must wait till after hell.”

Yet, many poets don’t realize what their poems are about until they write the ending line . Poetry is a search for truth, especially the hard truths that aren’t easily explained in casual speech. Your poem, too, might not be finished until it comes across a necessary truth, so write until you strike the heart of what you feel, and the poem will come to its own conclusion.

7. Edit, Edit, Edit!

Do you have a working first draft of your poem? Congratulations! Getting your feelings onto the page is a feat in itself.

Yet, no guide on how to write a poem is complete without a note on editing. If you plan on sharing or publishing your work, or if you simply want to edit your poem to near-perfection, keep these tips in mind.

- Adjectives and Adverbs: Use these parts of speech sparingly. Most imagery shouldn’t rely on adjectives and adverbs, because the image should be striking and vivid on its own, without too much help from excess language.

- Concrete Line Breaks: Line breaks help emphasize important words, making certain images and ideas clearer to the reader. As a general rule, most of your lines should start and end with concrete words—nouns and verbs especially.

- Stanza Breaks: Stanzas are like paragraphs to poetry. A stanza can develop a new idea, contrast an existing idea, or signal a transition in the poem’s tone. Make sure each stanza clearly stands for something as a unit of the poem.

- Mixed Metaphors: A mixed metaphor is when two metaphors occupy the same idea, making the poem unnecessarily difficult to understand. Here’s an example of a mixed metaphor: “a watched clock never boils.” The meaning can be discerned, but the image remains unclear. Be wary of mixed metaphors—though some poets (like Shakespeare) make them work, they’re tricky and often disruptive.

- Abstractions: Above all, avoid using excessively abstract language. It’s fine to use the word “love” 2 or 3 times in a poem, but don’t use it twice in every stanza. Let the imagery in your poem express your feelings and ideas, and only use abstractions as brief connective tissue in otherwise-concrete writing.

Lastly, don’t feel pressured to “do something” with your poem. Not all poems need to be shared and edited. Poetry doesn’t have to be “good,” either—it can simply be a statement of emotions by the poet, for the poet. Publishing is an admirable goal, but also, give yourself permission to write bad poems, unedited poems, abstract poems, and poems with an audience of one. Write for yourself—editing is for the other readers.

How to Write a Poem: Different Approaches and Philosophies

Poetry is the oldest literary form, pre-dating prose, theater, and the written word itself. As such, there are many different schools of thought when it comes to writing poetry. You might be wondering how to write a poem through different methods and approaches: here’s four philosophies to get you started.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Emotion

If you asked a Romantic Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the spontaneous emotion of the soul.

The Romantic Era viewed poetry as an extension of human emotion—a way of perceiving the world through unbridled creativity, centered around the human soul. While many Romantic poets used traditional forms in their poetry, the Romantics weren’t afraid to break from tradition, either.

To write like a Romantic, feel—and feel intensely. The words will follow the emotions, as long as a blank page sits in front of you.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Stream of Consciousness

If you asked a Modernist poet, “What is poetry?” they would tell you that poetry is the search for complex truths.

Modernist Poets were keen on the use of poetry as a window into the mind. A common technique of the time was “Stream of Consciousness,” which is unfiltered writing that flows directly from the poet’s inner dialogue. By tapping into one’s subconscious, the poet might uncover deeper truths and emotions they were initially unaware of.

Depending on who you are as a writer, Stream of Consciousness can be tricky to master, but this guide covers the basics of how to write using this technique.

How to Write a Poem: Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a practice of documenting the mind, rather than trying to control or edit what it produces. This practice was popularized by the Beat Poets , who in turn were inspired by Eastern philosophies and Buddhist teachings. If you asked a Beat Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the human consciousness, unadulterated.

To learn more about the art of leaving your mind alone , take a look at our guide on Mindfulness, from instructor Marc Olmsted.

https://writers.com/mindful-writing

How to Write a Poem: Poem as Camera Lens

Many contemporary poets use poetry as a camera lens, documenting global events and commenting on both politics and injustice. If you find yourself itching to write poetry about the modern day, press your thumb against the pulse of the world and write what you feel.

Additionally, check out these two essays by Electric Literature on the politics of poetry:

- What Can Poetry Do That Politics Can’t?

- Why All Poems Are Political (TL;DR: Poetry is an urgent expression of freedom).

Okay, I Know How to Write a Good Poem. What Next?

Poetry, like all art forms, takes practice and dedication. You might write a poem you enjoy now, and think it’s awfully written 3 years from now; you might also write some of your best work after reading this guide. Poetry is fickle, but the pen lasts forever, so write poems as long as you can!

Once you understand how to write a poem, and after you’ve drafted some pieces that you’re proud of and ready to share, here are some next steps you can take.

Publish in Literary Journals

Want to see your name in print? These literary journals house some of the best poetry being published today.

https://writers.com/best-places-submit-poetry-online

Assemble and Publish a Manuscript

A poem can tell a story. So can a collection of poems. If you’re interested in publishing a poetry book, learn how to compose and format one here:

https://writers.com/poetry-manuscript-format

Join a Writing Community

writers.com is an online community of writers, and we’d love it if you shared your poetry with us! Join us on Facebook and check out our upcoming poetry courses .

Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it exists to educate and uplift society. The world is waiting for your voice, so find a group and share your work!

Sean Glatch

27 comments.

super useful! love these articles 💕

Indeed, very helpful, consize. I could not say more than thank you.

I’ve never read a better guide on how to write poetry step by step. Not only does it give great tips, but it also provides helpful links! Thank you so much.

Thank you very much, Hamna! I’m so glad this guide was helpful for you.

Best guide so far

Very inspirational and marvelous tips

Thank you super tips very helpful.

I have never gone through the steps of writing poetry like this, I will take a closer look at your post.

Beautiful! Thank you! I’m really excited to try journaling as a starter step x

[…] How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step […]

This is really helpful, thanks so much

Extremely thorough! Nice job.

Thank you so much for sharing your awesome tips for beginner writers!

People must reboot this and bookmark it. Your writing and explanation is detailed to the core. Thanks for helping me understand different poetic elements. While reading, actually, I start thinking about how my husband construct his songs and why other artists lack that organization (or desire to be better). Anyway, this gave me clarity.

I’m starting to use poetry as an outlet for my blogs, but I also have to keep in mind I’m transitioning from a blogger to a poetic sweet kitty potato (ha). It’s a unique transition, but I’m so used to writing a lot, it’s strange to see an open blog post with a lot of lines and few paragraphs.

Anyway, thanks again!

I’m happy this article was so helpful, Eternity! Thanks for commenting, and best of luck with your poetry blog.

Yours in verse, Sean

One of the best articles I read on how to write poems. And it is totally step by step process which is easy to read and understand.

Thanks for the step step explanation in how to write poems it’s a very helpful to me and also for everyone one. THANKYOU

Totally detailed and in a simple language told the best way how to write poems. It is a guide that one should read and follow. It gives the detailed guidance about how to write poems. One of the best articles written on how to write poems.

what a guidance thank you so much now i can write a poem thank you again again and again

The most inspirational and informative article I have ever read in the 21st century.It gives the most relevent,practical, comprehensive and effective insights and guides to aspiring writers.

Thank you so much. This is so useful to me a poetry

[…] Write a short story/poem (Here are some tips) […]

It was very helpful and am willing to try it out for my writing Thanks ❤️

Thank you so much. This is so helpful to me, and am willing to try it out for my writing .

Absolutely constructive, direct, and so useful as I’m striving to develop a recent piece. Thank you!

thank you for your explanation……,love it

Really great. Nothing less.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Poetry Facts

The Power of Poetry in Speeches

As a poetry lover, I’m sure you understand how influential poetry can be. Throughout history, many great leaders, activists, politicians have brought poetry into their speeches, crafting powerful messages that can (and did) change the world.

In today’s article, we’re going to look at poetry in speeches , why you should use poetry in your next speech, how to go about doing so, and of course, the famous poetic speeches across eras. Let’s dive in!

Why Use Poetry in a Public Speech

Poetry is powerful. That’s why there are many benefits to using poetry in a public speech. What benefits, you ask?

Well, for starter, a poem can really serve as a highlight of a speech, breaking the usual monotony. It adds a fresher element to the speech, and helps to capture the audience’s attention better.

Poetry can also be a very good reference point in your speech. By adding a familiar poem to the audience, the speaker can help the audience understand the subject that he or she is trying to convey better.

A good poem can really add an additional depth to your speech, if you know how to use it right. The audience can’t help but feel a strong influence, and the speaker has a much better chance of leaving an impact.

I think all of us can agree that poetry has an air of literary elegance to it. By adding poetry to your speech, you also bring that elegance and a lot of class into your presentation.

Finally, sometimes, poetry can say a lot more with less. Adding a poem at the right moment of the talk can help you being more concise and establish a deep connection with the audience.

So I hope by now I’ve convinced you that it’s a good idea to try adding poetry into your speech. In the next section, we’re going to talk about how to do it.

How to Use Poetry in A Public Speech

It’s pretty clear that poetry can enhance a speech greatly if done right. But it can be tricky if you’re not a poet nor a student of poetry yourself. Here are something to keep in mind if you want to use poetry in your next speech:

1. Choose the right poem

This should go without saying, but if you’re going to use poetry in your speech, make sure that the poem you choose fit within the context of what you’re trying to say. A poem should help you get your point across and make an impression on the audience, not making them confused or worse, zone out. So do your homework.

2. Have a plan

Most people don’t read poetry on a daily basis. This means that you can’t just bring a poem out of nowhere into your speech. You need to provide some introduction to the poem, why do you chose the poem, what’s the background story, etc. Prepare the audience so that they can listen to the poem from the best position possible.

3. Speak like a poet

Ever seen a spoken-word poet perform on stage? If you haven’t, then you should do it because you will learn a lot from them. Writing poetry is an art, but not many people think the same about delivering a poem to an audience that way. You’ll need to learn how to project from the diaphragm, posturing, pacing, etc. Watch a poet perform and try to practice your delivery as best as you can.

4. Don’t think too much

The last tip is kind of counter intuitive, but after all the preparing and practicing, you should not think when you go and perform. Thinking is great when you’re trying to practice, but once on stage, it will likely hinder your performance. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. After all, that’s how you get better.

5 Famous Poetic Speeches in History

1. i have a dream by martin luther king jr..

This is probably one of the most inspiring speeches of all time. Delivered on the 28th of August, 1963 by American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., “I have a dream” was a defining speech of the civil rights movement.

In the speech, King used anaphora, a poetic device in which the author repeats an expression at the beginning of a number of sentences. With a single phrase “I have a dream,” Martin Luther King Jr. joined ranks with the men who shaped modern America.

2. We shall fight on the beaches by Winston Churchill

“We shall fight on the beaches” is one of the three major speeches by the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. This speech was delivered to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom on the 4th of June, 1940, warning about a possible invasion attempt by Nazi Germany.

Churchill is known for spending hours working on every minute of his speech. He wrote every word, and carefully crafting them so that the final draft “looks like a draft of a poem,” according to many critics.

3. Ain’t I a Woman? by Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was a well known anti-slavery speaker and one of the most revolutionary advocates for women’s human rights in the 1800s. The speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” was delivered at the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention held in Akron, Ohio, addressing the discrimination of woman and African Americans in the post-Civil War era.

It is a poetic speech that many people have adapted it into a poem itself. Here’s the speech, delivered by Nkechi at a TEDx event in 2013.

4. Still I Rise by Maya Angelou

This one is a legit poem as a speech. “Still I Rise” is a poem written by Maya Angelou, an American poet, memoirist, and civil rights activist. She is well-known for uplifting fellow African American women through her work.

“Still I Rise” is one of Angelou’s most popular poems, inspiring black women everywhere to keep good faith and striving for equality and peace.

Final thoughts

By now, I’m sure we all can understand how much weight that poetry, or even just a poetic device, can bring into a speech. I hope that you’ve learned something new and useful, maybe even some inspirations to incorporate poetry into the next chance you have to deliver a public speech.

More interesting articles about poetry:

- A Brief Introduction To Closed Form Poetry

- The Beauty Of Typography In Poetry

- Dissonance In Poetry: Everything You Need To Know

Thomas Dao is the guy who created Poem Home, a website where people can read about all things poetry related. When he’s not busy working on his next project, you can find him reading a good book or spending time with family and friends.

Share this article

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related Articles

7 Beautiful Poems About Her Eyes

In the human body, eyes are one of the most delicate organs. They’re the mirrors of our emotions and the

5 Steps to Deal With Nerves Before A Poetry Slam

Many poets don’t like to perform in front of a crowd. Why struggle to deliver your lines on stage, when

Anti-poetry: Seeking Harmony in Discordance

Anti-poetry has been around for a while now, but it’s gaining more and more attention as the world becomes more

6 Mystic Poems That Will Touch Your Heart and Soul

Have you ever felt a connection to the divine, or experienced a moment of transcendence? If so, then you know

7 Poems About Monetary Greed We All Should Read

Money. It’s been called the root of all evil. But is it really? Or is it the love of money

22 Beautiful Poems for Aunts – The Second Mothers

Whether you are close to our aunties or have only seen them occasionally, these poems about aunts might offer a

9 Encouraging Poems About Waiting For Love

True love is worth the wait. Don’t forget that, don’t ever forget that. You neither have to force it, nor

9 Relaxing Poems About The Natural Wild Forest

The natural wild forest can be a place of solace and relaxation. The poems in this post capture the beauty

8 Poems About Respect Worth Paying Attention To

Respect is something that is often taken for granted. We often show respect to others without thinking, and sometimes we

11 Best Poems About The Night That Will Intrigue You

To many people, the energy of the night always seems so mysterious and unattainable. It’s completely different from daylight, almost

5 Poems in Mount & Blade: Warband and How to Use Them

In this article, we’re going to talk about poetry in Mount & Blade: Warband. You’re going to learn everything about

Sponsored Articles

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Writing Poetry

How to Write a Poem

Last Updated: April 14, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Alicia Cook . Alicia Cook is a Professional Writer based in Newark, New Jersey. With over 12 years of experience, Alicia specializes in poetry and uses her platform to advocate for families affected by addiction and to fight for breaking the stigma against addiction and mental illness. She holds a BA in English and Journalism from Georgian Court University and an MBA from Saint Peter’s University. Alicia is a bestselling poet with Andrews McMeel Publishing and her work has been featured in numerous media outlets including the NY Post, CNN, USA Today, the HuffPost, the LA Times, American Songwriter Magazine, and Bustle. She was named by Teen Vogue as one of the 10 social media poets to know and her poetry mixtape, “Stuff I’ve Been Feeling Lately” was a finalist in the 2016 Goodreads Choice Awards. There are 16 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 7,073,142 times.

Writing a poem is about observing the world within or around you. A poem can be about anything, from love to loss to the rusty gate at the old farm. Writing poetry can seem daunting, especially if you do not feel you are naturally bursting with poetic ideas. With the right inspiration and approach, you can write a poem that you can be proud to share with others in the class or with your friends.

How to Start Writing Poetry

- Pick a topic or theme that interests you, or brainstorm ideas by writing to a prompt like “what water feels like” or “how it feels to get bad news.”

- Read famous poems and choose a poem format that you like. For example, you could try a playful structure like a limerick or a romantic one like a sonnet.

- Write lines for your poem with sound in mind. Read your poem out loud and consider the way the words in your poems flow together. Make any necessary edits.

Sample Poems

Starting the Poem

Brainstorming for Ideas Try a free write. Grab a notebook or your computer and just start writing—about your day, your feelings, or how you don’t know what to write about. Let your mind wander for 5-10 minutes and see what you can come up with. Write to a prompt. Look up poem prompts online or come up with your own, like “what water feels like” or “how it feels to get bad news.” Write down whatever comes to mind and see where it takes you. Make a list or mind map of images. Think about a situation that’s full of emotion for you and write down a list of images or ideas that you associate with it. You could also write about something you see right in front of you, or take a walk and note down things you see.

Finding a Topic Go for a walk. Head to your favorite park or spot in the city, or just take a walk through your neighborhood. Use the people you see and nature and buildings you pass as inspiration for a poem. Write about someone you care about. Think about someone who is really important to you, like a parent or your best friend. Recall a special moment you shared with them and use it to form a poem that shows that you care about them. Pick a memory you have strong feelings about. Close your eyes, clear your head, and see what memories come to the forefront of your mind. Pay attention to what emotions they bring up for you—positive or negative—and probe into those. Strong emotional moments make for beautiful, interesting poems.

- For example, you may decide to write a poem around the theme of “love and friendship.” You may then think about specific moments in your life where you experienced love and friendship as well as how you would characterize love and friendship based on your relationships with others.

- Try to be specific when you choose a theme or idea, as this can help your poem feel less vague or unclear. For example, rather than choosing the general theme of “loss,” you may choose a more specific theme, such as “loss of a child” or “loss of a best friend.”

- You may decide to try a short poetic form, such as the haiku , the cinquain , or the shape poem. You could then play around with the poetic form and have fun with the challenges of a particular form. Try rearranging words to make your poem sound interesting.

- You may opt for a form that is more funny and playful, such as the limerick form if you are trying to write a funny poem. Or you may go for a more lyrical form like the sonnet , the ballad , or the rhyming couplet for a poem that is more dramatic and romantic.

- “Kubla Khan” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge [4] X Research source

- “Song of Myself” by Walt Whitman [5] X Research source

- “I measure every Grief I meet” by Emily Dickinson [6] X Research source

- “Sonnet 18” by William Shakespeare [7] X Research source

- “One Art” by Elizabeth Bishop [8] X Research source

- “Night Funeral in Harlem” by Langston Hughes [9] X Research source

- “The Red Wheelbarrow” by William Carlos Williams [10] X Research source

Writing the Poem

- For example, rather than try to describe a feeling or image with abstract words, use concrete words instead. Rather than write, “I felt happy,” you may use concrete words to create a concrete image, such as, “My smile lit up the room like wildfire.”

Try a New Literary Device Metaphor: This device compares one thing to another in a surprising way. A metaphor is a great way to add unique imagery and create an interesting tone. Example: “I was a bird on a wire, trying not to look down.” Simile: Similes compare two things using “like” or “as.” They might seem interchangeable with metaphors, but both create a different flow and rhythm you can play with. Example: “She was as alone as a crow in a field,” or “My heart is like an empty stage.” Personification: If you personify an object or idea, you’re describing it by using human qualities or attributes. This can clear up abstract ideas or images that are hard to visualize. Example: “The wind breathed in the night.” Alliteration: Alliteration occurs when you use words in quick succession that begin with the same letter. This is a great tool if you want to play with the way your poem sounds. Example: “Lucy let her luck linger.”

- For example, you may notice how the word “glow” sounds compared to the word “glitter.” “Glow” has an “ow” sound, which conjures an image of warmth and softness to the listener. The word “glitter” is two syllables and has a more pronounced “tt” sound. This word creates a sharper, more rhythmic sound for the listener.

- For example, you may notice you have used the cliche, “she was as busy as a bee” to describe a person in your poem. You may replace this cliche with a more unique phrase, such as “her hands were always occupied” or “she moved through the kitchen at a frantic pace.”

Polishing the Poem

- You may also read the poem out loud to others, such as friends, family, or a partner. Have them respond to the poem on the initial listen and notice if they seem confused or unclear about certain phrases or lines.

- You may go over the poem with a fine-tooth comb and remove any cliches or familiar phrases. You should also make sure spelling and grammar in the poem are correct.

Community Q&A

Reader Videos

- Brainstorm big things in your life and how they have impacted you. For example, if you write about how someone you know died, the tone of the poem could be the great sadness and loss you feel deep down and how it feels like a piece of you is missing. Thanks Helpful 17 Not Helpful 1

- Think about what matters in your life. It can give you ideas when you think about the people and places you love. You can write a poem in the form of the struggles in your life or the dangers you have had to face. You can also write a poem about the happiness someone or something has brought to your life. Remember, what you write about should set the mood of your poem. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

Tips from our Readers

- Poems are written mainly to touch the heart. Write a poem on something that's emotionally dear to you or that evokes some other feeling.

- There's no real rules around poetry. Write something that you enjoy writing and reading and don't worry about the rest!

- If you need inspiration, look at photos online or in a magazine or go for a long walk around your neighborhood.

- Try writing a poem based on a memorable dream you had the night before (or whenever!).

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.edutopia.org/article/every-student-can-be-poet/

- ↑ https://jerz.setonhill.edu/writing/creative1/poetry-writing-tips-h

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/the-empowerment-diary/201604/the-secret-writing-transformative-poetry

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/readingpoetry/

- ↑ https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45477/song-of-myself-1892-version

- ↑ https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/i-measure-every-grief-i-meet-561

- ↑ https://poets.org/poem/shall-i-compare-thee-summers-day-sonnet-18

- ↑ https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47536/one-art

- ↑ https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/night-funeral-harlem

- ↑ https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45502/the-red-wheelbarrow

- ↑ https://jerz.setonhill.edu/writing/creative1/poetry-writing-tips-how-to-write-a-poem/

- ↑ https://www.literacymn.org/sites/default/files/learning_center_docs/metaphors_and_similes.pdf

- ↑ https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1266002.pdf

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/poetry-explications/

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5709796/

- ↑ https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/naming-the-unnameable/chapter/chapter-eight-revision/

About This Article

Writing a poem can seem intimidating at first, but with a little patience and inspiration, you can produce a beautiful work of written art. If you’re not sure what to write about, spend a few minutes jotting down whatever thoughts come into your head. Think about your feelings, your experiences and memories, people in your life, or things that you sense in your environment and see if any of those things inspire you. You can also try working from writing prompts. Once you’ve done some free writing, look for themes and ideas in what you’ve written, and choose one that feels inspiring to you. Common themes include things like love, loss, family, or nature. After you choose a theme, think about how you’d like to structure the poem. For example, you might stick to a traditional format, such as a limerick, haiku, or quatrain. If you’d rather not feel constrained by rhymes or meter, consider writing a free verse poem and simply let the words flow in whatever way feels right. You can also read poems by other authors to get ideas and inspiration. When you’re writing the poem, look for ways to express your thoughts using powerful, sensory language. For example, instead of saying something like “I felt happy,” try using a colorful simile, like “My heart soared like a bird set free.” As you’re writing, also think about how the poem will sound when read out loud. Try reading it to yourself or a friend to see if it’s pleasing to the ear. If a word or phrase doesn’t flow the way you like, replace it with something else that has a similar meaning. You might not be satisfied with the first draft of your poem, and that’s totally okay. Read it to yourself, get feedback from friends, teachers, or other people you trust, and keep revising until you feel like you’ve created a poem that really captures the feelings you’re trying to convey. For help choosing a structure for your poem, like a haiku, limerick, or sonnet, read the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Mahnoor Kokab

Aug 11, 2016

Did this article help you?

Mar 20, 2018

Alex Sarich

Jan 6, 2021

Lucy Lebrun

Mar 1, 2019

Feb 7, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

How to Write a Poem: A Simple Guide for Beginners

How to write a Poem! To write a poem is to express oneself through the art of words. It is a beautiful form of creative writing that allows you to convey emotions, thoughts, and ideas in a unique and artistic way. Whether you are a seasoned poet or a beginner, learning how to write a poem can be a rewarding experience that allows you to explore your creativity and imagination.

In this article, you will learn the basics of how to write a poem. You will discover the different types of poetry, including sonnets, haikus, and free verse, and learn how to choose the type that best fits your message. You will also learn about the elements of poetry, such as rhyme, rhythm, and meter, and how to use them to create a powerful and memorable poem.

How to Write a Poem

Understanding Poetry

When it comes to understanding poetry, there are a few key elements you should be aware of. Forms of poetry, themes in poetry, and rhythm and rhyme are all important aspects to consider.

Forms of Poetry

Poetry comes in many different forms, each with its own unique structure and rules. Some of the most common forms of poetry include sonnets, haikus, and free verse. Understanding the structure and rules of each form can help you to better craft your own poetry.

For example, a sonnet typically consists of 14 lines, with a specific rhyme scheme and meter. Haikus, on the other hand, are three-line poems with a specific syllable count for each line. Free verse, as the name suggests, is poetry without any specific structure or rules.

Themes in Poetry

Themes in poetry can range from love and nature to politics and social issues. Understanding the themes that are common in poetry can help you to better appreciate and analyze the works of others, as well as inspire your own writing.

Some common themes in poetry include:

- Love and relationships

- Nature and the environment

- Death and mortality

- Politics and social issues

- Identity and self-discovery

Rhythm and Rhyme

Rhythm and rhyme are important elements in poetry that can help to create a sense of musicality and flow. Understanding the different types of rhyme and meter can help you to craft poems that are both pleasing to the ear and meaningful.

Some common types of rhyme include:

- End rhyme: when the last words of two or more lines rhyme

- Internal rhyme: when words within a line rhyme with each other

- Slant rhyme: when words have similar but not identical sounds

- Eye rhyme: when words look like they should rhyme, but do not

Meter refers to the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a poem. Common meters include iambic pentameter and trochaic tetrameter.

Getting Started

Writing poetry can be a daunting task, especially if you’re new to it. But with a little guidance, you can unleash your creativity and start writing beautiful, meaningful poems. Here are some tips on how to get started.

Choosing a Theme

Before you start writing your poem, it’s important to choose a theme. A theme is the main idea or message that you want to convey through your poem. It can be anything from love, loss, nature, or even a specific event or memory. Choosing a theme will help you focus your thoughts and give your poem direction.

To choose a theme, think about what inspires you or what you’re passionate about. You can also draw inspiration from your own experiences or observations of the world around you. Once you have a theme in mind, jot down some ideas or phrases that relate to it. This will help you develop your poem further.

Finding Inspiration

Now that you have a theme, it’s time to find inspiration. Inspiration can come from anywhere – a beautiful sunset, a meaningful conversation, or even a random thought. The key is to be open to it and to pay attention to the world around you.

To find inspiration, try some of the following:

- Take a walk in nature and observe your surroundings

- Listen to music or read poetry for inspiration

- Keep a journal and jot down your thoughts and observations

- Attend a poetry reading or open mic night for inspiration and community

Remember, inspiration can come from anywhere, so be open to new experiences and ideas.

Writing the Poem

Creating the first draft.

The first draft of a poem is often the most difficult to write. It’s important to remember that the first draft doesn’t have to be perfect. In fact, it’s often better to write freely without worrying too much about structure or rhyme.

When you’re writing the first draft, try to focus on the emotion or message you want to convey. You can worry about structure and rhyme later on. It’s also helpful to read your work out loud as you go along. This can help you identify areas that need improvement.

Using Metaphors and Similes

Metaphors and similes are great tools for adding depth and meaning to your poetry. A metaphor is a comparison between two things that are not alike but share something in common. For example, “life is a journey” is a metaphor that compares life to a journey.

A simile is similar to a metaphor but uses “like” or “as” to make the comparison. For example, “her eyes were like the ocean” is a simile that compares someone’s eyes to the ocean.

When using metaphors and similes in your poetry, try to choose ones that are original and unexpected. This will help your poetry stand out and make a lasting impression on your readers.

Creating Imagery

Imagery is another important element of poetry. It helps create a vivid picture in the reader’s mind and can make your poetry more engaging and powerful.

When creating imagery in your poetry, try to use all five senses. This will help your readers feel like they are experiencing the scene or emotion you are describing. For example, if you’re writing about a sunset, you might describe the colors of the sky, the warmth of the sun on your skin, and the sound of birds chirping in the distance.

Revising the Poem

As a poet, you know that writing the first draft of a poem can be a liberating and purposeful feeling. However, the real work begins when you start revising your poem. Revising your poem is an art and can be more creative than writing the first draft. In this section, we will discuss the two essential sub-sections of revising your poem: reviewing and editing, and getting feedback.

Reviewing and Editing

Reviewing and editing your poem is an essential part of the revision process. It involves reading your poem carefully and making changes to improve its overall quality. Here are some tips to help you review and edit your poem:

- Read your poem aloud: Reading your poem aloud helps you hear the rhythm and flow of your words. It also helps you identify awkward phrasing, repetition, and other issues that might not be apparent when you read silently.

- Check for grammar and punctuation errors: Make sure your poem is free of grammar and punctuation errors. Use a grammar checker or proofreading tool to help you identify any mistakes.

- Simplify your language: Use simple and clear language to convey your message. Avoid using jargon or complex words that might confuse your readers.

- Cut unnecessary words: Remove any unnecessary words or phrases that do not add value to your poem. This will help you keep your poem concise and to the point.

Getting Feedback

Getting feedback is an essential part of the revision process. It helps you identify areas that need improvement and provides you with fresh perspectives on your work. Here are some tips to help you get feedback on your poem:

- Share your poem with trusted readers: Share your poem with friends, family, or fellow poets who can provide you with honest and constructive feedback.

- Join a writing group: Joining a writing group can help you get feedback from a diverse group of writers. It also provides you with an opportunity to learn from others and improve your writing skills.

- Attend poetry workshops: Attending poetry workshops can help you get feedback from professional poets and learn new techniques to improve your writing.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some tips for starting a poem?

Starting a poem can be challenging, but there are several ways to get started. You can begin by brainstorming ideas or topics that inspire you. You can also start by writing down a single word or phrase that captures your attention and build from there. Another technique is to use a prompt or writing exercise to jumpstart your creativity.

How do you structure a poem?

The structure of a poem can vary depending on the type of poem you are writing. Some common structures include sonnets, haikus, and free verse. When structuring your poem, consider the length, rhythm, and rhyme scheme. You can also experiment with line breaks, stanzas, and other poetic devices to create a unique structure.

Are there any rules to follow when writing poetry?

While there are no strict rules for writing poetry, there are some guidelines to keep in mind. For example, poems are typically written in stanzas and use poetic devices such as rhyme, alliteration, and imagery. It’s also important to pay attention to the rhythm and flow of your poem. However, these guidelines are not set in stone and can be broken for creative effect.

What are some examples of good poetry?

There are many examples of great poetry, ranging from classic works by Shakespeare and Emily Dickinson to contemporary poets like Maya Angelou and Billy Collins. Reading widely and studying different styles and forms can help you develop your own voice and style.

How do you write a poem for children?

When writing poetry for children, it’s important to use simple language and vivid imagery. Consider using repetition, rhyme, and other poetic devices to engage young readers. You can also incorporate themes and topics that are relevant to children, such as animals, nature, and friendship.

What are some creative writing techniques for poetry?

There are many creative writing techniques that can be used in poetry, such as metaphor, simile, personification, and onomatopoeia. You can also experiment with different forms and structures, such as found poetry or blackout poetry. It’s important to stay open to new ideas and approaches and to keep practicing and refining your craft.

Last Updated on August 30, 2023

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- Utility Menu

Poetry at Harvard

- Guide to Prosody

Terms for Describing Prosody

There are many different ways of describing the spoken cadences of verse. Various languages and poetic traditions listen for stress, vowel length, syllable count, or some combination of these three, and poets experiment with all of them. What follows below is an outline of the basics. The following terms describe the generally agreed-upon system for approximating, in writing, our speech rhythms. It is a reasonably efficient system, but it's important to remember that it's not perfect: there are far more subtle variations in speech rhythms than the simple binary of "stressed" and "unstressed" (or, in quantitative meters, "long" and "short") can register.

Some general terms:

Terms that describe the number of lines in a stanza. Note: a stanza need not have lines of uniform length or rhythm. Click here for a glossary of common poetic forms.

Terms that describe the number of feet in a line. Note: while most meters are composed in just one kind of foot per line, poets frequently vary the prescribed rhythm. For English prosody, a good rule of thumb is to count the number of beats (stresses) per line.

- Key to Poetic Forms

- Guide to Poetic Terms

- Glossary of Poetic Genres

Poetry Out Loud

How To Write a Poem

By Laura Hershey

Don't be brilliant. Don't use words for their own sake, or to show how clever you are, how thoroughly you have subjugated them to your will, the words.

Don't try to write a poem as good as your favorite poet. Don't even try to write a good poem.

Just peel back the folds over your heart and shine into it the strongest light that streams from your eyes, or somewhere else.

Whatever begins bubbling forth from there, whatever sound or smell or color swells up, makes your throat fill with unsaid tears,

whatever threatens to ignite your hair, your eyelashes, if you get too close—

write that. Suck it in and quickly shape it with your tongue before you grow too afraid of it and it gets away.

Don't think about writing a good poem, or a great poem, or the poem to end all poems.

Write the poem, you need to hear; write the poem you need.

Laura Hershey, "How to Write a Poem" from Laura Hershey: On the Life & Work of an American Master. Copyright © 2019 by Laura Hershey. Reprinted by permission of The Estate of Laura Hershey.

Source: Laura Hershey: On the Life & Work of an American Master (Unsung Masters Series, 2019)

- Arts & Sciences

More By This Poet

We are taught not to gamble. Perhaps it is thought we have lost enough already—legs, vision, speech, the typical use of our bodies. Others' fears would teach us to cringe at any thought of any risk. Disability and risk don't mix. Risk is something we are supposed to be protected from— by agencies,...

- Social Commentaries

More Poems about Activities

Golden hour.

When you caught one to keep, we took it home and I asked you to teach me. You showed me how to spike the brain— I thanked the fish, looked away, pressed down. We bled it, shaved away the scales, severed meat from bone. I’m afraid...

By Kimberly Casey

A Wing and a Prayer

We thought the birds were singing louder. We were almost certain they were. We spoke of this, when we spoke, if we spoke, on our zoom screens or in the backyard with our podfolk. Dang, you hear those birds? Don’t they sound loud?...

By Beth Ann Fennelly

More Poems about Arts & Sciences

Listening in deep space.

We've always been out looking for answers, telling stories about ourselves, searching for connection, choosing to send out Stravinsky and whale song, which, in translation, might very well be our undoing instead of a welcome. We launch satellites, probes, telescopes unfolding like origami, navigating geomagnetic storms, major disruptions. Rovers...

By Diane Thiel

Self-Portrait with Sylvia Plath’s Braid

Some women make a pilgrimage to visit it in the Indiana library charged to keep it safe. I didn’t drive to it; I dreamed it, the thick braid roped over my hands, heavier than lead. My own hair was long for years. Then I became...

By Diane Seuss

How To Write A Poem: Comprehensive Guide For Beginners

Tips on how to write a poem.

Ever wondered how to write a poem but felt overwhelmed by where to start?

Crafting a compelling poem often begins with identifying a poignant moment or stirring emotion that resonates.

This guide will walk you through the basics, from choosing your subject to refining your verses, ensuring that poetry doesn’t have to be perplexing for beginners.

Dive in – poetic expression awaits!

Key Takeaways

- Start by picking a topic that touches your heart, then play with words and sounds to express it.

- Use literary devices like similes and metaphors to add depth to your poem.

- Try different forms like sonnets or free verse to find what best suits your message.

- Edit your work by reading aloud and changing words for the strongest impact.

- Join a writing community , seek mentorship from published poets , and keep practicing .

Table of Contents

Understanding the elements of poetry.

Before diving into the creative current of poetry, it’s essential to grasp its foundational elements — these are the building blocks that give your verses structure and depth.

From the subtle dance of assonance to the precise architecture of stanzas, each aspect works in harmony to transform a mere string of words into an evocative literary masterpiece.

Sound in poetry

They use sounds to support their themes and messages.

Rhymes give poems a catchy beat and can make them fun to say out loud. Learning about syllables helps you see patterns in stress and rhythm.

Mastering rhyme boosts your creativity everywhere – not just in writing poems!

Sound devices are your secret tools for making each poem unique and powerful .

Use them wisely to create special effects that stick with the reader long after they’ve finished reading.

Moving beyond sound, we find that rhythm truly breathes life into a poem. It creates a beat, much like the heartbeat of your piece.

Picture rhythm as the drum you tap to while reading your poem out loud—it shapes how fast or slow, smooth or choppy the words flow from one line to another.

Think of stressed and unstressed syllables as the building blocks of rhythm; they help you decide where emphasis falls in each line.

Rhythm can stir emotions and reinforce your message. Use it skillfully to make readers feel the excitement, calmness, or tension with every verse they read.

Consider how sometimes repeating certain sounds at regular intervals can add power to an idea or emotion you want to express.

Mastering this musical element will set your poetry apart, turning simple words into an experience that resonates deeply with those who hear them .

Rhythm sets the beat, but rhyme brings harmony to your poem. A good rhyme can make your lines sing.

Think of it as a pattern where sounds match at the end of each line or in the middle.

These matching sounds are part of what’s called a “ rhyme scheme .” Poets craft these schemes to give their work structure and flow.

You don’t need every line to rhyme, but when they do, it creates melody and rhythm that stick with readers long after they’ve read your poem.

Explore different types of rhymes, like slant rhymes or eye rhymes , to add variety.

Use rhyme scheme wisely – it guides listeners through your poetry, making each verse memorable. Sound matters in poetry; let’s use it well!

Literary devices

Literary devices are like secret tools poets use to make their writing stand out. Think of them as spices in cooking—they add flavor and depth.

Poets sprinkle these devices throughout their work to stir up emotions and thoughts in the reader’s mind.

For example, similes compare two things using “like” or “as,” making images more vivid.

Metaphors do a similar job but without the comparison words, creating solid connections directly.

Analogies extend those comparisons even further, often across several lines or an entire poem, building complex relationships between ideas.

Sound devices like alliteration repeat consonant sounds at the beginning of words close together—it can make a line hum!

Personification gives human traits to non-human things; it makes everything feel alive and relatable.

Using these literary tools well takes practice. Begin by playing with them in your writing exercises—see how they change your poem’s sound when read out loud or alter its meaning line by line.

Let’s dive into how you can start your journey step-by-step by choosing a topic for your poem next!

Just as literary devices add depth to your words, form gives shape to your poem.

Many types of poetry have specific structures , like a sonnet with its 14 lines and strict rhyme scheme.

Choose a free verse that flows without set rules. Each form comes with its rhythm and flow.

Trying out different poetic forms can be an exciting way to find the one that resonates with you.

Explore traditional forms such as haikus or limericks if you’re looking for clear rules to guide you.

For more freedom, consider a free verse where line breaks and stanza divisions are up to you.

The important thing is how the structure reflects what you want to say—whether it’s controlling pace through quatrains or building intensity with couplets.

Whatever form catches your eye, give it a shot! Experimenting is part of discovering your unique voice in poetry .

How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step

Diving into the world of poetry can be exhilarating yet intimidating, but with a solid step-by-step approach, crafting your verses becomes an attainable adventure.

This section is where creativity meets methodology; it’s about transforming that spark of inspiration into lines that resonate and stir emotions — let’s get those words flowing!

Choosing a topic

Picking a subject for your poem is like choosing the heart of your message. Look for ideas that stir your emotions, things you feel deeply about.

This connection makes your words more powerful and can touch others, too. Use images and experiences from life to bring richness to the theme.

Brainstorming helps you explore different angles of the topic before starting your poem. Jot down single words, phrases, or even feelings related to the idea.

These notes will be valuable in crafting lines that resonate with readers later on.

Think about what kind of poem celebrates or reflects upon these thoughts—this sets the tone for writing something significant.

Consideration of form

Poems come in shapes and sizes. Some are long; others are just a few words.

There’s free verse , which doesn’t follow rules, and then there’s sonnets with 14 lines that often tell about love.

Haikus from Japan have three lines with a pattern of 5, 7, and 5 syllables.

Think about the form before you start writing your poem. Want to share a story? Try a ballad ! They’re like songs telling tales.

Or pick cinquains if you want something short but mighty – they’ve got five lines that paint a vivid picture.

Make sure your choice suits the mood and message of your poem – it helps bring your words to life!

Word exploration

Pick each word carefully, like choosing a color for a painting. Think about how they sound and feel. Some words can make your poem soft or loud, fast or slow.

Play with language to find the perfect match for your ideas.

Look at different words until you find ones that fit just right. Try synonyms to see if they add something new to your lines.

Use strong verbs to give power to what you write and paint clear pictures in the reader’s mind.

Word choice is critical – it can turn a simple message into something beautiful and full of life!

Writing process

Let your ideas flow onto the page without worrying about perfection. Start with brainstorming and free-writing in prose to get your thoughts out.

This technique helps tap into emotions and can spark creativity for your poem. Try to include feelings and consider using nature as an inspiration source.

Once you’ve got a bunch of ideas, shape them into a first draft of your poem. Don’t fret over misspelled words or misplaced commas; write something down!

Exploring different words, rhythms, and rhymes will refine your vision. As you write, pause often to feel the beat of each line —this is where rhythm comes alive.

After finishing this step, you’ll be ready to edit your poem —a crucial part that polishes rough edges and tightens up language.

Now, let’s move on to reshaping with editing .

Once your poem is on paper, it’s time to fine-tune it. Dive into the editing process with fresh eyes and a sharp mind.

Look for lines that could be clearer or stronger. Swap out any weak words for ones that pack more punch.

Listen to how each line sounds; cut out extra words that drag down your rhythm.

Editing is about polishing your work until it shines. Read your poem aloud—does anything sound off? Fix those spots!

Changes might include cutting lines, adding imagery, or playing with the order of words.

Even minor tweaks can make a big difference in how your poem flows and feels to readers.

Keep shaping and refining because every edit gets you closer to a poem you’ll be proud to share!

Different Approaches and Philosophies for Writing Poetry

Exploring the vast landscape of poetry can be as diverse as the poets who pen it—each with a unique approach to uncovering the heart’s musings.

Whether you’re capturing fleeting emotions or painting with words in a stream-of-consciousness style, your philosophy shapes every stanza; it’s about finding that resonance within and letting it ripple through your verses.

Emotion-driven

Poems can make hearts race or bring tears to the eyes. They reach deep into feelings, sometimes in ways that stories and songs cannot touch.

The secret? Poets pour their own emotions onto the page.

When you try your hand at writing poetry with emotion , let your heart lead. Think about what stirs you up inside—joy, anger, sadness—and write it down.

Use words like a painter uses colors; mix and match till they feel just right. You don’t need fancy tricks or rigid rules to convey raw emotions .

If a line of your poem makes you laugh or cry when you read it back, chances are it will move someone else, too.

Poetry isn’t just about form and technique—it’s also writing from the soul for an audience of one or many .

Let each word take its reader on a journey through sensations, guiding them to taste, smell, see, and feel everything you pour into your lines.

Stream of consciousness

Stream of consciousness lets you capture every twist and turn of your thoughts.

This style can feel like a wild river of ideas , jumping from one to another without strict rules. Think of it as a direct line from your brain to the page.

Your readers get to ride the rapids of emotions and images just as they come. This powerful technique is not just for stories or novels; poets use it, too.

It can add depth to your poetry by showing how feelings and thoughts connect in real time. Don’t worry about making perfect sense at first.

Let your mind wander and spill those raw, unedited thoughts onto paper. Use specific words that pop into your head—no matter how strange or disconnected they may seem.

Feel free to mix memories, hopes, fears, and dreams all in one poem. Permit yourself to break traditional poetic structures with this method!

Mindfulness

Mindfulness brings a special touch to poetry writing . As you focus on the present moment , each word flows with purpose and intention.

It’s like using poetry to capture snapshots of life’s experiences.

Whether observing the rustle of leaves or the rush of emotions, mindfulness in writing helps explore personal insights deeply.

Writing mindfully also offers peace and clarity for both the poet and the reader.

A poem becomes more than just words; it transforms into a journey through sights, sounds, and sensations .