Beneath the weathered baseball cap and bushy goatee, the parade of plaid shirts and the polite replies of "Yes, ma'am," there's a whole lot more to Bill Baker. Sure, he listens to old-school country in his pickup truck while driving between manual labor gigs and he never fails to pray before a meal, even if it's tater tots and a cherry limeade from Sonic. It seems perfectly natural to him to keep a couple of guns in his run-down Oklahoma home, and he never misses an opportunity to watch his favorite college football team.

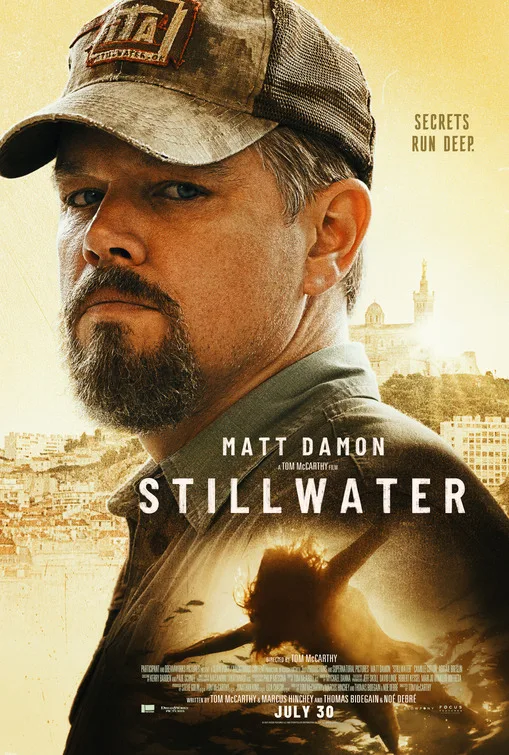

But there's something simmering within this collection of red-state stereotypes, and "Stillwater" is at its best when it explores those complexities and contradictions. Beefed-up and sad-eyed, Matt Damon brings great subtlety and pathos to the role, especially when he cracks his stoic character open ever so gently and allows warmth, vulnerability, and even hope to shine through on his road to redemption. But Bill's tale of hard-earned second chances is one of many stories director Tom McCarthy is telling in "Stillwater," and while it's the most compelling, it also gets swallowed up almost entirely during the film's insane third act.

The script, which McCarthy co-wrote with Thomas Bidegain , Marcus Hinchey , and Noe Debre, loosely takes its inspiration from the case of Amanda Knox, the American college student convicted in 2007 of killing her roommate while studying abroad in Italy. Eight years later, Knox was acquitted. "Stillwater" moves the action to the French port city of Marseilles and introduces us to Bill's daughter, Allison ( Abigail Breslin ), after she's already served five years of a nine-year prison sentence for the murder of her lover, a young Muslim woman.

Allison insists she's innocent; Bill resolutely believes her. And so "Stillwater" is also the story of a father and daughter trying to mend their strained relationship as he makes frequent visits to chat and do her laundry and she pretends to care as he prattles on about Oklahoma State football. (The college campus is in—that's right—Stillwater, Bill and Allison's hometown. But as you've probably guessed by now, the title refers to our hero's demeanor, as well.) "Life is brutal," each of them says at one point, and one of the more intriguing elements of "Stillwater" is the notion that being a screw-up is hereditary, which pushes against its feel-good, Hollywood-ending urges.

But wait, there's more—so much more. Because the primary driving narrative here is the possibility that Allison can prove her innocence based on jailhouse hearsay about an elusive, young Arab man. Here, "Stillwater" becomes a procedural reminiscent of McCarthy's Oscar best-picture winner " Spotlight ," as Bill knocks on doors and follows one lead after another, talking to people who either help him or don't in his efforts to exonerate his only child. In this vein, it's also about the racial tensions and socioeconomic disparities that exist in both France and the United States, and the blindly confident swagger with which some Americans carry themselves overseas—even someone like Bill who is, to borrow from the Tim McGraw song, humble and kind.

And for a big chunk of its midsection, it's about a middle-aged man forming an unexpected friendship—and then a makeshift family—with a single mom and her little girl. Virginie (a vibrant and charismatic Camille Cottin ) and her daughter, Maya (an adorable and steely Lilou Siauvaud ), give the widowed Bill a shot at righting the wrongs of his past. Virginie and Bill initially connect when she offers to help him in his investigation by making calls, translating and generally serving as his guide through an ancient city he's barely gotten to know. The relationship makes zero sense on paper—she's a bohemian actress, he's an oil-rig worker—but the small kindnesses they show each other allow them to forge a bond, and allow Bill to reveal more about himself and his tortured history, piece by piece. It sounds cheesy, but surprisingly, it works.

This is far and away the strongest section of "Stillwater," and if the majority of this film had focused on this understated dynamic and the quiet hope of better days to come, it would have been more than satisfying. The performances here are lovely, and Damon enjoys distinctly sweet connections with both Cottin and Siauvaud. But then it takes a significant turn into darker territory toward the end, with twists predicated on major coincidences and reckless decisions. "Stillwater" also becomes a far less interesting film as it slogs through its overlong running time. While it's fascinating to consider Bill's self-destructive streak rearing its head once again, even after it seems he's finally found some peace, the way it plays out is so wild and implausible, it feels like it was ripped from an entirely different movie and grafted on here. Within this eventful stretch, there's also a suicide attempt that's tossed in almost as a baffling afterthought, as it's never mentioned again.

Ultimately, the cacophony of all these plot lines converging and the weight of the messaging being conveyed is almost too much to bear. Details get spelled out and characters explain their motivations when maintaining an overall air of mystery would have been far more effective. Whether or not Allison is guilty isn't the point; enjoying a moment of stillness and solitude in the afternoon sunshine is, even if it's fleeting.

Now playing in theaters.

Christy Lemire

Christy Lemire is a longtime film critic who has written for RogerEbert.com since 2013. Before that, she was the film critic for The Associated Press for nearly 15 years and co-hosted the public television series "Ebert Presents At the Movies" opposite Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, with Roger Ebert serving as managing editor. Read her answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here .

- Matt Damon as Bill Baker

- Abigail Breslin as Allison

- Camille Cottin as Virginie

- Deanna Dunagan as Sharon

- Robert Peters as Pastor

- Moussa Maaskri as Dirosa

- Lilou Siauvaud as Maya

- Marcus Hinchey

- Thomas Bidegain

- Tom McCarthy

Cinematographer

- Masanobu Takayanagi

- Mychael Danna

- Tom McArdle

Leave a comment

Now playing.

Night Is Not Eternal

All We Imagine as Light

Elton John: Never Too Late

The Creep Tapes

Small Things Like These

Bird (2024)

Latest articles

Black Harvest Film Festival 2024: Disco Afrika, It Was All a Dream, Dreams Like Paper Boats

Ted Danson Stars in Lovely, Moving “A Man on the Inside”

Appreciating the Brushstrokes: Pre-Computer Animation and the Human Touch

“Call of Duty: Black Ops 6” is Best Installment in the Franchise in Years

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Stillwater’ Review: Another American Tragedy

Matt Damon plays a father determined to free his daughter from prison in the latest from Tom McCarthy, the director of “Spotlight.”

- Share full article

By Manohla Dargis

A truism about American movies is that when they want to say something about the United States — something grand or profound or meaningful — they typically pull their punches. There are different reasons for this timidity, the most obvious being a fear of the audience’s tricky sensitivities. And so ostensibly political stories rarely take partisan stands, and movies like the ponderously earnest “ Stillwater ” sink under the weight of their good intentions.

The latest from the director Tom McCarthy (“Spotlight”), “Stillwater” stars Matt Damon as Bill Baker. He’s a familiar narrative type with the usual late-capitalism woes, including the dead-end gigs, the family agonies, the wounded masculinity. He also has a touch of Hollywood-style exoticism: He’s from Oklahoma. A recovering addict, Bill now toggles between swinging a hammer and taking a knee for Jesus. Proud, hard, alone, with a cord of violence quaking below his impassivity, he lives in a small bleak house and lives a small bleak life. He doesn’t say much, but he’s got a real case of the white-man blues.

He also has a burden in the form of a daughter, Allison (a miscast Abigail Breslin), who’s serving time in a Marseille prison, having been convicted of savagely killing her girlfriend. The story, which McCarthy conceived of (he shares script credit with several others), takes its inspiration from that of Amanda Knox, an American studying in Italy, who was convicted of a 2007 murder, a case that became an international scandal. Knox’s conviction was later overturned and she moved back to the United States, immortalized by lurid headlines, books, documentaries and a risible 2015 potboiler with Kate Beckinsale .

Like that movie, which focuses on the sins of a vampiric, sensation-hungry media, “Stillwater” isn’t interested in the specifics of the Knox case but in its usefulness for moral instruction. Soon after it opens, and following a tour of Bill’s native habitat — with its industrial gothic backdrop and lonely junk-food dinners — he visits Allison, a trip he’s taken repeatedly. This time he stays. Allison thinks that she has a lead that will prove her innocence, which sends her father down an investigative rabbit hole and, for a time, quickens the movie’s pulse.

McCarthy isn’t an intuitive or innovative filmmaker and, like a lot of actors turned directors, he’s more adept at working with performers than telling a story visually. Shot by Masanobu Takayanagi, “Stillwater” looks and moves just fine — it’s solid, professional — and Marseille, with its sunshine and noir, pulls its atmospheric weight as Bill maps the city, trying to chase clues and villains. Also earning his pay is the underutilized French Algerian actor Moussa Maaskri, playing one of those sly, world-weary private detectives who, like the viewer, figures things out long before Bill does.

Much happens, including an abrupt, unpersuasive relationship with a French theater actress, Virginie (the electric Camille Cottin, from the Netflix show “ Call My Agent !”). The character is a fantasy, a ministering angel with a hot bod and a cute tyke (Lilou Siauvaud); among her many implausible attributes, she isn’t ticked off by Bill’s inability to speak French. But Cottin, a charismatic performer whose febrile intensity is its own gravitational force, easily keeps you engaged and curious. She gives her character juice and her scenes a palpable charge, a relief given Bill’s leaden reserve.

There’s little joy in Bill’s life; the problem is, there isn’t much personality, either. It’s clear that Damon and McCarthy have thought through this man in considered detail, from Bill’s plaid shirts to his tightly clenched walk. The character looks as if he hasn’t moved his bowels in weeks; if anything, he feels overworked, a product of too much conceptualizing and not enough feeling, identifiable humanity or sharp ideas. And because Bill doesn’t talk much, he has to emerge largely through his actions and tamped-down physicality, his lowered eyes and head partly obscured by a baseball hat that hangs over them like a visor.

It is, as show people like to say, a committed performance, but it’s also a frustratingly flat one. Less character than conceit, Bill isn’t a specific father and uneasy American abroad; he’s a symbol. McCarthy tips his hand early in the first scene in Oklahoma with the image of Bill precisely framed in the center of a window of a house he’s helping demolish. A tornado has ripped through the region, leveling everything. When Bill pauses to look around, surveying the damage, the camera takes in the weeping survivors, the rubble and ruin. It’s a good setup, brimming with potential, but as the story develops, it becomes evident this isn’t simply a disaster, natural or otherwise. It’s an omen.

Like “Nomadland” and any number of Sundance movies, “Stillwater” seizes on the classic figure of the American stoic, the rugged individualist whose self-reliance has become a trap, a dead end and — if all the narrative parts cohere — a tragedy. And like “Nomadland,” “Stillwater” tries to say something about the United States (“Ya Got Trouble,” as the Music Man sings) without turning the audience off by calling out specific names or advancing an ideological position. Times are tough, Americans are too (at least in movies). They keep quiet, soldier on, squint into the sun and the void. Bad things happen and it’s somebody’s fault, but it’s all so very vague.

Stillwater Rated R for violence and language. Running time: 2 hour 20 minutes. In theaters.

Manohla Dargis has been the co-chief film critic since 2004. She started writing about movies professionally in 1987 while earning her M.A. in cinema studies at New York University, and her work has been anthologized in several books. More about Manohla Dargis

Explore More in TV and Movies

Not sure what to watch next we can help..

A ‘Wicked’ Tearful Talk : Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande, the stars of the new movie, reflected on their long ride together , getting through Covid and the actors’ strike, and avoiding “playing to the green.”

Ridley Scott Returns to the Arena : The director of “Gladiator II” speaks his mind on rejected sequel ideas, Joaquin Phoenix’s plan to quit the original and working with a “fractious” Denzel Washington.

The Clint Squint : When Clint Eastwood narrows his eyes, pay attention. The master of the big screen is using them to convey seduction, intimidation, mystery and more .

Streaming Guides: If you are overwhelmed by the endless options, don’t despair — we put together the best offerings on Netflix , Max , Disney+ , Amazon Prime and Hulu to make choosing your next binge a little easier.

Watching Newsletter: Sign up to get recommendations on the best films and TV shows to stream and watch, delivered to your inbox.

‘Stillwater’ Review: Matt Damon Gets to the Heart of How the World Sees Americans Right Now

'Spotlight' director Tom McCarthy collaborates with top French screenwriter Thomas Bidegain in this humbling Marseille-set crime drama.

By Peter Debruge

Peter Debruge

Chief Film Critic

- ‘Wicked’ Review: Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande Give Iconic Turns in the Year’s Must-See Musical 2 days ago

- At 80, Udo Kier — Who’s Starred in Everything From Andy Warhol’s Films to ‘Ace Ventura’ — Looks Back on a Lifetime of Cult Encounters 2 weeks ago

- Warner Bros. Planned to Send ‘Juror No. 2’ to Streaming, but the Film Proves Clint Eastwood Is Still Built for Theaters 2 weeks ago

Americans are used to watching Americans save the day in movies. That’s the kind of hero Bill Baker wants to be for his daughter Allison — a young woman convicted of murdering her girlfriend while studying abroad — in “Spotlight” director Tom McCarthy ’s not-at-all-conventional crime thriller “ Stillwater .” The setup will sound familiar to anyone who remembers the Amanda Knox case: Five clicks in to a nine-year sentence, Allison has always maintained her innocence. After new evidence arises, she writes a letter to her lawyer asking for help. But she’s careful not to involve her dad directly. “I cannot trust him with this. He’s not capable,” she writes.

To a particular kind of man, words like that are a direct challenge. And when that man is played by Matt Damon in sleeveless T-shirts and a bald-eagle tattoo, we expect him to save the day anyway. Maybe he does, but that’s not the reason McCarthy chose to tell this story. Originally, he just wanted to film a mystery in a Mediterranean town, deciding at some point that the French port of Marseille would do the trick. But in the time that it took to make the movie, something changed with America. Maybe you noticed. Certainly, the world did.

Related Stories

Why Samsung’s FAST Platform Could Be Poised for Its Breakout Moment

J.K. Rowling Says John Oliver ‘Spouts Absolute Bulls---’ About Trans Athletes Not Posing ‘Any Threat to Safety and Fairness’ in Women’s Sports

McCarthy tells “Stillwater” from Bill Baker’s point of view, but he invites audiences to see the character from others’ perspectives as well, to observe how this out-of-place roughneck looks to the people he meets abroad — and especially to a single mother named Virginie (“Call My Agent!” star Camille Cottin) whom the gruff widower befriends early on. Back home in Stillwater, Okla., Bill does odd jobs since losing his oil-rig gig. He wouldn’t be in Marseille if not for his daughter (Abigail Breslin). He’s not a tourist, and he’s not interested in learning the language. But he’s not the stereotypical “ugly American” either. Bill prays, he’s polite and he believes in doing the right thing. And if Allison says she’s innocent, then the right thing in this God-fearing, gun-owning guy’s eyes is to help her prove it.

Popular on Variety

Now, anyone could’ve written that movie. But McCarthy was smart: He enlisted the top screenwriter working in France today, Thomas Bidegain (“A Prophet”), and his writing partner Noé Debré to collaborate and wound up with a completely different movie. Well, maybe not completely different, but different enough to disappoint those expecting to see Matt Damon whip out a gun and kick down some doors in pursuit of justice. (Let Mark Wahlberg make that film.)

Bidegain’s signature — the thing that sets him apart from the vast majority of screenwriters — is that he doesn’t write “the scene where” a specific plot point is supposed to happen. Watching most Hollywood thrillers, that’s all you get, as if the creators bought a bunch of index cards, divided the movie into story-advancing moments (the scene where A, the scene where B) and taped them to the wall, then built the script from that. Bidegain knows we’ve all seen enough movies that such literal-mindedness gets boring, and so he and Debré come at each scene sideways: They let certain things happen off screen, focusing instead on seemingly mundane snapshots that reveal far more about character.

“Stillwater” contains a mix of both approaches — a scene where a friend of Virginie’s asks Bill whom he voted for is a prime example — and while it’s hard to say who wrote what (Marcus Hinchey, of terrific Netflix drama “Come Sunday,” is also credited), the movie’s more interesting for being less obvious. Naturally, Bill wants to clear his daughter’s name, and “Stillwater” shows him going about it. But the cultural barriers make it impossible to get far by himself — a trip to north Marseille’s notorious Kallisté neighborhood leaves him hospitalized — and so he enlists Viriginie, winning her over by being kind to her 8-year-old daughter Maya (Lilou Siauvaud).

Of course, Bill can’t change French law, and it’s not clear that even if he could locate the guy Allison claims was responsible — an Arab who was there in the bar that night — he’d be able to overturn her conviction. But as he and Virginie spend time together, Bill shows Maya the kind of fatherly concern he was too drunk and reckless to give Allison when she was a kid. The guilt of that irresponsibility weighs heavy on Bill, adding another dimension to Damon’s remarkable performance. There’s something caveman-like about the way the actor carries his body, in the scowl on his face and slow drawl of his Southern accent. The character has a temper problem, and from the looks of him, he could tear someone in two — although that might not be advisable in a foreign country.

After hitting a dead end in the investigation, Bill decides to stay on in Marseille. He moves in with Virginie and Maya, picking up a few words of French and playing handyman around the house. To dub this Bill’s redemption might oversimplify things, although something’s plainly changing in him. And that change is the soul of “Stillwater.” Resisting any temptation to be cute, yet bolstered by child actor Siauvaud’s immensely sympathetic presence, the movie gives Bill — as well as audiences — a taste of another life.

Will Americans who haven’t been abroad connect with this part of the movie? Or will they be bored with every second that Bill isn’t proactively trying to prove Allison’s innocence? At 140 minutes, “Stillwater” spends a lot more time on Bill’s new domestic situation with Virginie and Maya than viewers probably expect. But then, these scenes take time, since they’re tasked with conveying more than just the latest development in the case. (By contrast, straightforward genre movies have the luxury of being tight.) Ironically, the clunkiest scene here occurs when the cops show up.

McCarthy has more on his mind, using Damon’s character to “make hole” (as roughnecks do) in various assumptions Americans hold about themselves. Bill serves as a mirror of what foreigners see when a certain kind of cowboy barrels through the saloon doors of another country, hands on his holster, and it’s not necessarily flattering. On the surface, that may not satisfy everyone, but then, to coin a phrase, “Stillwater” runs deep.

Reviewed at Cannes Film Festival (Out of Competition), July 8, 2021. MPAA Rating: R. Running time: 140 MIN.

- Production: A Focus Features release of a Participant, DreamWorks Pictures presentation of a Slow Pony, Anonymous Content production, in association with 3Dot Prods., Supernatural Pictures. Producers: Steve Golin, Tom McCarthy, Jonathan King, Liza Chasin. Executive producers: Jeff Skoll, David Linde, Robert Kessel, Mari Jo Winkler-Ioffreda, Thomas Bidegain, Noé Debré. Co-producers: Raphaël Benoliel, Melissa Wells.

- Crew: Director: Tom McCarthy. Screenplay: Tom McCarthy & Marcus Hinchey, Thomas Bidegain & Noé Debré. Camera: Masanobu Takayanagi. Editor: Tom McArdle. Music: Mychael Danna.

- With: Matt Damon, Camille Cottin, Abigail Breslin, Lilou Siauvaud, Deanna Dunagan, Idir Azougli, Anne Le Ny.

More from Variety

Amazon Taps Jennifer Hudson, Martha Stewart and More to Host Black Friday Shopping Shows Powered by TalkShopLive

Disney’s Bundling Strategy Will Be Key to Long-Term Streaming Success

‘The Office’ Christmas Storybook Has Arrived — And It’s Already a No. 1 Bestseller on Amazon

Amazon MGM Studios Hires Disney Alum Alexandra Weinberger as Head of YA and Comedy Series

A New Kind of Storyteller Is Needed for Immersive Entertainment

Eric Kripke, Antony Starr on ‘The Boys’ Holding Up a Mirror to Society, Homelander’s Arc in Season 4

More from our brands.

The Private-Jet World Is Optimistic About 2025, Despite a Post-Covid Slow-Down

Penn State Wins Industry-Shaping Trademark Trial Over Logo Use

The Best Loofahs and Body Scrubbers, According to Dermatologists

Black Doves Trailer: Keira Knightley’s Outed Spy Seeks Revenge in Netflix’s Upcoming Thriller

‘Stillwater’ Examines Lives in Wreckage, With Matt Damon at the Center

By K. Austin Collins

K. Austin Collins

Matt Damon ’s new movie, Stillwater , opens by building up to a gentle but pointed bit of misdirection, the subtle sort of deviation from our expectations meant to say as much about the audience as it does about the man at the story’s center — something of an running theme for this particular movie. When we first see Bill Baker (Damon), he’s waist-deep in rubble, the recognizable but devastated remains of what used to be someone’s home. Bill is a roughneck from Oklahoma, a state squarely, oft-tragically at the center of that mid-U.S. stretch known as Tornado Alley. His main line of work used to be oil rigs; when that labor dried up and he got laid off, he turned to construction. In the wake of a tornado, construction skills are easy to repurpose for demolition and recovery. So that’s what Bill does. He is, at this stage of his life, a maker of things.

Yet thanks to that tornado, he’s getting his hands dirty in the remains of utter mess, the wreck of lives painfully unmade — another theme in the making. It’s clear early on that we’re meant to experience the world of this movie through Bill’s eyes, or at the very least firmly at his side. When he’s riding home from the wreckage with some colleagues, at dusk, he overhears them saying, “I don’t think Americans like to change,” and “I don’t think the tornado cares what Americans like.” Only they’re speaking Spanish. If Bill understands it, he doesn’t react to it; Damon’s face gives nothing away. Nor is the man overly emotive soon after, when paying a visit to his mother-in-law, Sharon (Deanna Dunagan), and the pair engage each other in naturalistically terse conversation, talk full of ellipses that we don’t realize are ellipses, because real people don’t speak as if they know strangers are watching — and these, the movie is committed to impressing upon us, are real people.

It’s not long before Bill hops on a plane, seemingly all of a sudden, and lands — in France. In sunny, coastal Marseilles, to be exact, a fact that lands with the force of a punchline, despite there being nothing funny at stake in the particulars of this voyage. It’s early in the movie, and Damon — a more than capable actor, whose physical commitment to his roles is, in contrast to his oft-touted ability to “disappear,” remarkably underrated — has already sold us on Bill as a man who could plausibly be the man that the movie wants us to believe he is. He is a “Yes, ma’am” type of guy with an Okie drawl, eyes often hiding behind his wraparound shades, jeans stiff, cap grimed with years of oil and sweat, and an array of plaid shirts, bulgy with hard-working, middle-age fat and muscle, that tells us there’s little distance between a work uniform and everyday life for this man. He’s in France but does not speak French. When it comes to picking accommodations, he opts for what must feel like a slice of home: a Best Western. He is pronouncedly, unabashedly, though not quite crudely, a so-called red-blooded American. So, a fish out of water — and eventually gasping for breath. Stillwater , which was directed and co-written by Tom McCarthy ( Spotlight ), has been advertised and described as a thriller. But it doesn’t open like one. It opens like this: with a slow accrual of details, in which it’s almost easy to miss Bill noticing what appear to be oil refineries just outside of Marseilles, as if he plans to stay awhile; or the fact that the hotel workers already know Bill’s name, making him less of a stranger in a strange land than, to the French eye, simply a little strange. This is an apt choice for a story in which a sense of being out of place while increasingly desperate, having to rely on others while navigating utterly unfamiliar cultural terrain, is going to matter a great deal; it is, in so many ways, the point of the story.

Editor’s picks

The 100 best tv episodes of all time, the 250 greatest guitarists of all time, the 500 greatest albums of all time, the 200 greatest singers of all time.

Rather, it’s one point of the story. The other part is the stuff that’s gotten Stillwater in a bit of trouble, earning it the courtesy of being called “a calamitous reworking of [a] notorious murder case.” Bill’s not here for pleasure; he’s here to visit his daughter, Allison ( Abigail Breslin ), who’s in prison for the murder of her French Arabic roommate — a case that bears an undeniable resemblance to the 2007 murder of British exchange student Meredith Kercher in Perugia, Italy. This is a case that is more commonly associated with the woman wrongfully convicted — twice — of that murder : Amanda Knox , a fellow exchange student from Seattle, who along with her boyfriend at the time, Raffaele Sollecito, was sentenced to more than 20 years in prison, despite the fingerprints of the actual murderer, Rudy Guede, being present at the scene. Knox was fully exonerated in 2015. She has, it’s no surprise to hear, heard about Stillwater , heard about the resemblance to her case, and is not pleased .

Related Stories

Amanda knox upcoming hulu series sparks backlash in italy, 'the instigators': movie stars plus boston, divided by gunshots and laughs.

And it’s true: The similarities are more than a matter of mere resemblance. The film in fact started, according to McCarthy , with the Kercher murder and the accused Knox more fully on its mind, until the director, who co-wrote the script, became more interested in the surrounding circumstances. But even Stillwater ’s expansion beyond the 2007 tragedy and its aftermath feels somewhat drawn from Knox’s story, given the film’s focus on the heroics — many of them, in the film’s case, wrongheaded — of the accused Knox’s father was one of her most diligent and vocal advocates throughout her ordeal. Stillwater ’s basic premise is that of a man who, after being slipped a note by his daughter and asked to pass it along to her attorney, feels compelled to save her in light of the system failing her. Allison gets a tip that she wants her attorney to look into: a man, she’s been told, has confessed to a murder that bears striking resemblance to that for which she’s imprisoned. Her attorney, calling the tip hearsay, feels it would be wiser not to give the young woman false hope and advises Bill to perform in kind. Instead, Bill steps in and begins to investigate on his own; he can’t afford the private detective that he’s been recommended. And besides, he has some making up to do with his daughter. Theirs is a strained relationship from the start. So begins much invention on the film’s part.

The complications of Stillwater and, really, the meat and bones of its story, have less to do with the Mercher-Knox story in itself than with these inventions. Suffice it to say that Bill has his reasons for wanting to do right by his daughter at this stage of her life and that, for her, it’s too little, too late. He also needs help navigating the labyrinth of a foreign country in which he does not speak the language, in any sense of the word; the movie doesn’t shy away from making good on the promise of his being wholly, stubbornly out of place. Bill, now having to extend his stay way beyond what he’d planned, falls in with a single mother, Virginie (Camille Cottin), and her daughter Maya (Lilou Siauvaud), who become his guides, his English teachers, and — well.

It makes for a satisfying film in some ways, primarily because of Damon, Cottin, and Siauvaud, and the mere curiosity of their playing house — she a French actress whose work in theater is way above Bill’s head, he a hands-on gentle giant with a past, a man who did not vote for Trump (which he’s of course asked), but only because, as a convicted felon, he couldn’t vote at all. No one has to say: But he would have . But much of what fascinates the movie seems to be the fact that he would have, which carries with it all manner of opportunity for presumption and assumption on the part of the audience. The movie knows what it’s doing when it tees these ideas up and gently circumvents them with a sometimes-effective veneer of human complexity. How will Bill respond when a bar owner he questions starts to spout off rampant anti-Arab comments? And when this story begins to boil down to a white American with an Oklahoma drawl hunting down a French Arab twentysomething who’s done wrong by his daughter, what violence is the film pushing us to expect?

It’d be more openly ridiculous, feel far more manipulative, if not for Damon’s performance, which — despite his Cambridge-born, Harvard dropout roots — is widely appreciated for what people insist on calling his “Everyman” qualities . I’d sooner say that Damon’s magic is in making a certain plainness, a near-anonymity, defiantly charismatic. This is what makes him great in spy movies like The Good Shepherd , where he practically blends into the surrounding furniture of the movie, and what makes the “Where’s Waldo?” suspensions of belief at the heart the Bourne franchise, or the against-the-odds implausibility of The Martian , so effective. Stillwater depends on precisely that matrix of actorly skill and unvarnished likability; Damon’s other magic trick is removing all signs of the strings holding the performance together, like he’s his own CGI wizard, his own best special effect.

What this means for Stillwater : A movie that’s complicated, moving, and accordingly frustrating. You can feel it trying to paint the most rigorously humane portrait of, not only its hero, but the thorny sidebars of the situation he’s found himself in — the tense racial discomforts, the nauseating swerves into Bill’s bad decisions. McCarthy’s prevailing approach here as in Spotlight , his nonstyle style, its tempered lack of visual flare paired with its heightened attentiveness to Damon’s (and Cottin’s!) centrifugal star power, feels at times like a ruse for obscuring just how carefully modulated, even calculating, it is in its politics. We can’t help but notice that as his daughter speaks freely about the woman whose murder she’s accused of as being her girlfriend, her red-blooded, prayerful, gun-owning father, who deploys the phrase “fake news” despite by and large refusing to discuss politics, doesn’t even wince. It’s on us, the movie seems to say, that we’d assume homophobia of the man. This is the sly power of McCarthy’s style and intentions: Our assumptions become more readily noticeable as, possibly, matters of projection.

The illusion often works — until it doesn’t. The movie’s assured realism sometimes butts up against moments that feel woefully misguided, mangled in either the script, the editing room, or both — such as its failure to make proper dramatic sense of characters’ feelings in the aftermath of someone’s suicide attempt, or a late choice to save someone’s ass that doesn’t quite add up psychologically or make sense logistically. The movie’s attentive sense of noticing makes its flaws, its leaps in logic, easier to notice. But this seems to matter less to the filmmakers than what the style has to offer the movie in terms of a message; on this front, Stillwater is tellingly consistent. Damon and McCarthy have both spoken at length about the time they spent in Oklahoma, among real-life roughnecks, earning their trust, learning their ways, feeling more confident in the goodness of the world, the nuances in people, thanks to the lessons learned and memories shared. (“It was truly intellectually exciting and engaging,” McCarthy has said, astonished to the point of near-condescension. “I was impressed by them on a lot of levels. Truly impressed by them.”)

The realism is not incidental and not unsatisfying. But nor is it always as wise as it would seem. In the best case, what Stillwater encourages are genuine instances of reflection, particularly for and about a man in Bill’s shoes. The connections drawn between anti-Arab sentiment in both France and the U.S. are, by brunt of who Bill is, ripe for consideration. To lean too heavily into this subject would be to shatter the illusion of Bill’s ironic complexity — ironic, that is, for the people who’d be prone to writing him off. But the movie is invested in Bill’s complexity to the point of most everyone else, everything else, getting short shrift. A scene of Bill’s bullheaded, indiscreet wandering through what the movie depicts as something like the Marseilles projects, beholden to the familiar codes of snitching and the like that you’d expect of a scene set in the United States, ends in violence — the central point being a reiteration of Bill simply not knowing how to navigate a place such as this, with the undertone being a little less easily overlooked, a bit too slow to question the racial stereotypes piling up by the second.

It all — all of it, including the slow-building romance — leads up to a climax in which Bill makes a desperate, unwise decision. He risks everything. Ultimately, as in the case of its relationship to the Amanda Knox story, the movie can’t get around the consequences, for everyone else in this tale, of choosing to be so fully tied to Bill, so singularly focused on his desires and regrets and the idiosyncrasies that make him more than a stereotype, that the decision he makes somehow primarily moves us for what it means to his life, his chances, when there’s in fact another person who’s life is stake. A mistake is made; a rash decision is pushed to a devastating conclusion. Devastating for whom, is the question this film can’t quite face with the fullness that the question deserves.

In moments like this, it’s worth stepping back and asking ourselves who the movie is making us care about, why, and at what cost. In Bill’s case, the choices that pile up toward the end make us feel so fully for him that the movie nearly drives off-road into a rut from which it can’t recover. Dramatically, it works: The agitation we feel on his behalf is effective. Only when it ends do we realize what’s being left unsaid, whose life is ultimately rendered far less worthy of our sympathy and attention. This is when the movie shows us, ultimately and unabashedly, what it is — and suffers for its lack of reflection over what it could be.

From 'The Real World' to Congress and Beyond: Five MTV Reality Stars Who Made It Big

- Reality Overload

- By Andy Greene

‘Haiti on Fire’: Rolling Stone Dives Into the Country’s Deadly Gang War

- Rolling Stone Films

- By Jason Motlagh

How A Star of ‘The Sex Lives of College Girls’ Took Broadway and Hollywood by Storm

- Leveling Up

- By CT Jones

'A Man on the Inside' Puts Ted Danson Back in a Good Place

- By Alan Sepinwall

Selena Gomez Spills on Hiding Her Identity Before Auditions

- By Charisma Madarang

Most Popular

'the substance' director coralie fargeat pulls film from camerimage following festival head's comments about women, 178 amazon favorites that have earned a spot in everyone's cart, oscar predictions via feinberg forecast: scott's take heading into governors awards weekend, admissions to humanities and social science phd programs suspended at boston university, you might also like, ‘the bad guys 2’ trailer: natasha lyonne joins the heist in dreamworks sequel, black friday shoppers seek more than just price cuts, accenture study reveals, the best yoga mats for any practice, according to instructors, luca guadagnino directs omar apollo’s ‘te maldigo’ short film with trent reznor and atticus ross, penn state wins industry-shaping trademark trial over logo use.

Rolling Stone is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Rolling Stone, LLC. All rights reserved.

Review: Matt Damon is a man on a Marseille mission in the uneven but surprising ‘Stillwater’

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The Times is committed to reviewing theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic . Because moviegoing carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local health officials .

At the beginning of “Stillwater,” Bill Baker (Matt Damon), an Oklahoma construction worker, stands amid the remnants of a house that’s recently been destroyed by a tornado. He’s dependably good at his job, even if it’s just a temporary gig, something to tide him over while he looks for a more permanent position on an oil rig. Money and work have been scarce for a while, and the tornado, without affecting him directly, puts a cruel accent on the litany of disasters — alcoholism, unemployment, family estrangement, a criminal record — that his life has become. He’s gotten used to combing through the wreckage; when he leaves town a few beats later, it’s clear he’s not leaving behind much.

Although it draws its title from this Middle American city, most of Tom McCarthy’s methodical and surprising new drama takes place half a world away in the French port city of Marseille, where Bill finds himself on a curious and lonely assignment. He’s visiting his daughter, Allison (Abigail Breslin), who’s spent five years in prison for the murder of her girlfriend, Lena, whom she met while studying abroad in Marseille. The story was loosely inspired by events surrounding the 2007 killing of the British student Meredith Kercher, though McCarthy and his co-writers are not especially interested in a straightforward retelling of that tragedy.

Allison, the movie’s Amanda Knox figure, has always maintained her innocence. With four years left to serve, she asks her father to contact her attorney (Anne Le Ny) with new evidence that might persuade the authorities to reopen her case. A teenager, Akim, has allegedly implicated himself in a scrap of barroom hearsay, though it’s too flimsy a lead to persuade the attorney. But Bill, spying an opportunity to make up for his past negligence as a dad, stubbornly undertakes his own search for the elusive, possibly nonexistent Akim, all while navigating a city and a language that couldn’t feel more foreign.

To him, anyway. Centering its protagonist’s stern, bearded frown in nearly every scene, “Stillwater” registers Bill’s cultural confusion without necessarily indulging it. Unveiled this week at the Cannes Film Festival , a little further along France’s Mediterranean coast, the movie effectively merges the patient investigative rigor of McCarthy’s Oscar-winning newsroom drama “Spotlight” and the cross-cultural humanism of his earlier film “The Visitor.” Put another way, it’s a somber crime thriller wrapped around a sly fish-out-of-water comedy, in which Bill is invariably the butt of the joke.

“I’m a dumbass,” Bill says more than once, and the movie, however sympathetic to his plight, doesn’t really contradict him. Stiff of gait, clenched of jaw and plaid of shirt, Damon strides through the picture with a genial, determined cluelessness from which every lingering vestige of Jason Bourne has been carefully purged. Bill gets an A for effort, but the challenges of a murder investigation — tracing Instagram feeds, chasing down frightened witnesses — would prove daunting even to someone who knows the Marseille waterfront.

Fortunately, Bill meets a friendly bilingual guide in Virginie (a terrific Camille Cottin), a theater actress who regards this Sooner State refugee with kindness, amusement and an almost sociological fascination: Does he own a gun? Did he vote for Trump? (The answers are worth hearing for yourself.) Virginie also has a winsome young daughter, Maya (Lilou Siauvaud), who naturally hits it off with Bill immediately, raising the specter of a redemptive second shot at fatherhood. The mutually beneficial arrangement that follows — Virginie helps Bill with his search, Bill becomes her handyman and Maya’s babysitter — is one of those sentimental developments you grudgingly and then gladly accept, because the actors have such warm, involving chemistry and because there’s something irresistible about the kindness of strangers.

The best passages of “Stillwater” allow that kindness to flourish and take center frame, temporary liberating the movie from its dogged procedural template. McCarthy, a straightforward craftsman, has a gift for teasing out the humanity in every unshowy frame, and, working with cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi and editor Tom McArdle, he nicely conveys the passage of time and the blooming of fresh emotional possibilities. Those possibilities become still more heartrending when Allison is allowed out on parole for a day, in scenes that Breslin plays with a wrenching mix of toughness, resignation and despair. Through her eyes, we see the Marseille that she fell in love with and briefly wonder if her crucible of suffering might also mark a potential new beginning.

The filmmakers, of course, have chosen France’s oldest and most diverse city for a reason, given its longstanding reputation as a gritty hotbed of crime and poverty — a reputation that’s been partly fueled by the movies themselves, among them classic thrillers like “The French Connection” and “Army of Shadows” (and the recent “Transit,” a classic in the making). McCarthy has cited Marseille noir novels as an inspiration for his screenplay, which he wrote with Marcus Hinchey and the French writers Thomas Bidegain and Noé Debré, who were doubtless crucial in fleshing out a persuasively inhabited street-level portrait of contemporary France. Notably, Bidegain and Debré have also fashioned “Stillwater” into a curious echo of their 2015 neo-western, “Les Cowboys,” another father-daughter rescue story set at a Franco-American cultural crossroads.

In “Les Cowboys,” a white man is driven mad by the realization that his daughter has run off with her Muslim boyfriend. Although it’s cut from different genre cloth, “Stillwater” doesn’t have to dig too deep to uncover similarly ugly sentiments in Marseille as Bill’s search for an Arab suspect brings him face to face with all manner of casual anti-immigrant bigotry. Bill, it’s worth noting, comes off rather better by comparison: He seems appreciably less racist than some of the locals, and if this devout Christian has any negative thoughts about his daughter’s passionate romance with an Arab woman, he keeps them to himself. His mission here isn’t motivated by religion, politics or ideology, but by the simple desire to bring his daughter home. Nothing could be more primal or understandable.

Our sympathetic identification with Bill, in other words, is the reason this movie exists. It’s also the reason a viewer might find “Stillwater” troubling as well as absorbing. This is the story, after all, of a white male American charging into a French Arab community (represented by fine actors including Moussa Maaskri, Nassiriat Mohamed and Idir Azougli) and running roughshod over cultural sensitivities in his aggressive pursuit of what he considers justice. It’s also ostensibly the story of a dead Arab woman who nonetheless remains at the narrative margins and who exists primarily as a catalyst for her lover’s incarceration and potential exoneration.

The standard defense against this criticism is that the filmmakers are smart and self-aware enough to have anticipated it. In this case they’ve also sought to defuse it by treating Bill’s narrative centrality as a point of subversion, a means of rejecting the trumped-up myth of American exceptionalism that he represents. Bill’s outsider status, a source of pathos and comedy in the first two acts, threatens to become a moral liability in the third. McCarthy pushes the thriller narrative in directions more extreme and harrowing than plausible, bringing Bill and Allison’s story to an unexpected point of reckoning. It’s possible to be genuinely moved by that reckoning — and to admire the obvious intelligence and care that have been brought to bear on “Stillwater” — without fully buying the trail of contrivances and compromises it leaves in its wake.

‘Stillwater’

(In English and French with English subtitles) Rating: R, for language Running time: 2 hours, 20 minutes Playing: Opens July 30 in general release

More to Read

How a disillusioned Nigerian man’s trek to Europe becomes a test of faith and ambition

The 15 movies you need to see this summer

An ironic Mexico-set adventure novel has its swashbuckling cake and mocks it too

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Justin Chang was a film critic for the Los Angeles Times from 2016 to 2024. He won the 2024 Pulitzer Prize in criticism for work published in 2023. Chang is the author of the book “FilmCraft: Editing” and serves as chair of the National Society of Film Critics and secretary of the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Can men and women just be friends? ‘Sweethearts’ director Jordan Weiss knows the answer

Hollywood Inc.

‘Wicked’ and ‘Gladiator’ set the stage for gravity-defying box office weekend

Why Alexandre Desplat was so eager to score ‘The Piano Lesson’

Angelina Jolie scored as an evil fairy in ‘Maleficent,’ her top box-office hit

Most read in movies.

Review: Massive ‘Wicked’ movie adaptation takes its time to soar, much less defy gravity

Introducing Marissa Bode, the actor making ‘Wicked’ history in her film debut

Sydney Sweeney is no fan of Hollywood girlbosses who ‘fake’ support for other women

On a day when the world woke up to a nightmare in progress, they were in the control room

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Movie Reviews

Stillwater review: Matt Damon is a dad unmoored in atmospheric drama

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/image001-1-96bff255cc7d4c8da59d9d4192867e86.jpg)

By the trailer alone, Stillwater sells itself as fairly conventional kind of thriller: a recasting of the real-life Amanda Knox story, told through a lens of righteous parental vengeance. And in its lesser moments Tom McCarthy 's drama does lean toward a sort of Liam Neeson implausibility. At its best though, it's much quieter and more unsettling than that — the slow-churn character study of a man ( Matt Damon ) who is arguably more lost than the incarcerated daughter ( Abigail Breslin ) he's so desperate to free will ever be.

Damon neatly disappears into the role of Bill Baker, a marginally employed Oklahoma oil rigger in stiff Wranglers and wraparound shades. He's the kind of guy whose thousand-yard squint and flying-eagle tattoos look like they were earned the hard way, but he also won't sit down to a sandwich without bowing his head for a proper blessing first. And nearly all the money he makes from his itinerant work goes directly towards trips to France — the same long-haul flight path through Atlanta, Frankfurt, then finally Marseille — to visit Breslin's Allison, a onetime exchange student now more than halfway into a nine-year prison sentence for killing her lover there.

That the victim was a girl and what Bill calls an "Arab" helped make the case an international sensation; inevitably, the headlines have faded, but his hope of rooting out miracles in a byzantine foreign legal system remains. Whatever the allure of a city like Marseille — cobbled streets and seaside cliffs, the eternal siren song of French pastries — he moves through it in a blinkered bubble, checking into the same drab Best Western and taking home his lonely foot-long dinners from a nearby Subway.

A chance encounter with a bohemian single mother named Virginie ( Call My Agent 's Camille Cottin ) and her young daughter Maya (Lilou Siauvad) offers the first inkling of real human interaction he seems to have had outside his brief and only marginally welcome visits to Allison. (He was not, it is heavily implied, a prime candidate for father of the year before her imprisonment.) Virginie turns out to be a godsend when it comes to navigating the intricacies of a country whose customs and language he can't begin to understand, though it's never entirely clear why such a lovely woman would do so much for a gruff and largely charmless stranger — "Refugees, zero waste… He's your new cause," a friend says to her, bemused — except for the fact that he is, you know, Matt Damon.

McCarthy, an Oscar-winning writer-director whose films include Spotlight and The Station Agent , generally crafts the kind of lived-in adult dramas whose unshowy intelligence belies the need for narrative shock and awe. So it's jarring when his script takes a soapier turn, swerving abruptly into not-without-my-daughter Neeson territory and away from the more patient, almost languid onion-peeling of its setup. Damon and Cottin sell the tone shift better than they should, and Breslin brings an itchy urgency to Allison — who even in her too-brief scenes manages to register not merely as a cipher or a victim of circumstance but a flawed, furious girl with her own hopes and agendas.

A lot will probably be made of Damon's foray into MAGA-Daddy drag, and it's a testament to his tightly coiled performance that Bill comes off as nuanced and sympathetic as he does: Though the intrinsic likability that makes him a movie star may be doing half the heavy lifting, you want to invest in this blunt, difficult man. McCarthy also embeds him so deeply in the daily rhythms of Marseille — the back alleys, grubby kebab shops, and sudden dazzling flashes of sun-dappled Gallic scenery — that the movie becomes a kind of immersive travelogue too. The unhurried rhythms of those scenes feel like their own reward, more compelling and true to life than any notion of third-act reveals or tidy cinematic endings. Grade: B

Related content:

- Matt Damon on the surprising life lessons he learned shadowing roughnecks for Stillwater

- Camille Cottin on Stillwater , House of Gucci , and coming to terms with international fame

- Matt Damon is an Oklahoma roughneck out to save his daughter in Stillwater first look

Related Articles

We sent an email to [email protected]

Didn't you get the email?

By joining, you agree to the Terms and Policies and Privacy Policy and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

User 8 or more characters with a number and a lowercase letter. No spaces.

username@email

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

- About Rotten Tomatoes®

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening This Week

- Top Box Office

- Coming Soon to Theaters

- Certified Fresh Movies

Movies at Home

- Fandango at Home

- Prime Video

- Most Popular Streaming Movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- 92% Wicked Link to Wicked

- 74% Gladiator II Link to Gladiator II

- 81% Blitz Link to Blitz

New TV Tonight

- 72% Dune: Prophecy: Season 1

- 100% Outlander: Season 7

- 82% Interior Chinatown: Season 1

- 76% Landman: Season 1

- 100% Based On A True Story: Season 2

- -- The Sex Lives of College Girls: Season 3

- -- A Man on the Inside: Season 1

- 25% Cruel Intentions: Season 1

- -- Our Oceans: Season 1

- -- Making Manson: Season 1

Most Popular TV on RT

- 100% Arcane: League of Legends: Season 2

- 91% Say Nothing: Season 1

- 95% The Penguin: Season 1

- 84% The Day of the Jackal: Season 1

- 76% Cross: Season 1

- 96% Silo: Season 2

- 100% Lioness: Season 2

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

Certified fresh pick

- 100% Arcane: League of Legends: Season 2 Link to Arcane: League of Legends: Season 2

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

All Twilight Saga Movies, Ranked by Tomatometer

50 Newest Verified Hot Movies

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming.

Awards Tour

The Gladiator II Cast on Working with Ridley Scott

Wicked First Reviews: “Everything a Movie Musical Should Be”

- Trending on RT

- Gladiator II First Reviews

- Holiday Programming

- Verified Hot Movies

Stillwater Reviews

What lifts Stillwater out of the doldrums of mediocrity is the performances of the actors and McCarthy’s admirable determination to steer away from the cliched idea of revenge actioner...

Full Review | Original Score: B | Apr 26, 2024

The lack of genre identity does not always work in the film's favor. [Full review in Spanish]

Full Review | Original Score: 3/4 | Jan 22, 2024

Stillwater refuses to belittle and judge its characters, and challenges viewers to do the same.

Full Review | Jul 27, 2023

Caught me by surprise with its fascinating journey of redemption, acceptance, & Beauty. Don’t get my wrong the movie evolves in ways I did not expect some for the better & some for the bad.

Full Review | Jul 26, 2023

Stillwater is pure drama that turns into a crime thriller when you least expect it. This is Matt Damon‘s best performance in the last 10 years.

Full Review | Original Score: 3.5/5 | Mar 30, 2023

A damn effective drama about the struggles accompanying second chances and unshakable reputations.

Full Review | Original Score: 3.5/5 | Oct 9, 2022

A classic narrative in the style of later Clint Eastwood, the film focuses on the protagonist's quest and his internal transformation. [Full review in Spanish]

Full Review | Original Score: 8/10 | Oct 4, 2022

Stillwater is so much more than its simple logline would lead you to believe, blending sentimentality with suspense to create a brutally captivating concoction.

Full Review | Original Score: 4.5/5 | Sep 1, 2022

I prefer McCarthy’s approach which keeps the characters front-and-center, giving them and their relationships room to grow even if it means running a little long.

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Aug 17, 2022

The final act turns the heat up a bit, as Bill gets closer and turns to more desperate means. The conclusion will raise some eyebrows, but in the main Stillwater is a solid drama that plays to the crowd effectively.

Full Review | Original Score: 3/5 | Mar 3, 2022

As a work of fiction, Stillwater feels near-masterpiece level with Tom McCarthy, Matt Damon and Abigail Breslin giving possibly the best performances of their careers. The movie, however, is undeniably tied to a real-life tragedy and feels manipulative

Full Review | Feb 12, 2022

The movie really keeps you guessing as to the true motives of the characters with its complex plot.

Full Review | Dec 28, 2021

This might be a crime thriller, but thrill it does not. Slow, distracted and unfocused, its narrative makes giant leaps one moment and drags its feet the next.

Full Review | Original Score: 3/5 | Dec 7, 2021

If we can't take responsibility for our own choices, then there can be no moving forward and your life will become a prison of your own making.

Full Review | Original Score: 3/5 | Oct 26, 2021

A slow burn that is far longer than it needs to be to get its point across. However, Matt Damon brings a lot of heart to this one, and makes it worth watching.

If tied to the real-life case, it's irresponsible and irredeemable. Separated from these knotty ties to the real world and accepted as a piece of fiction, it's a decent drama that begins strong before eventually losing its bearings and its believability.

Full Review | Original Score: 2.5/4 | Oct 23, 2021

Absent the sheen of a noble cause, Stillwater is a frustrating effort without a point.

Full Review | Original Score: C- | Oct 23, 2021

There's a dangerous lack of verisimilitude that hangs over the entire film. But McCarthy remains firm in his decision not to offer the usual satisfactions expected of these kind of American films. [Full Review in Spanish]

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Oct 18, 2021

Within half an hour its drama loses emotional records and dries up like an oil well in the desert when Matt Damon plays an ordinary hero lost in Marseille. [Full review in Spanish]

Full Review | Original Score: 5/10 | Sep 10, 2021

Stillwater's sharp emotional claws shred Bill's moral authority and the myth of American exceptionalism. In ways both shocking and right, director Tom McCarthy reinvents the story seemingly in real time.

Full Review | Original Score: 4/4 | Sep 2, 2021

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

Matt Damon Makes For an Excellent Unlovable American in Stillwater

Bill Baker, the Oklahoma oil-rig roughneck abroad played by an excellent Matt Damon in Stillwater , is not a Trump voter, but you can understand why one of the women he meets in Marseilles asks him about it outright. It’s not just that he looks like a guy who might have voted for Trump, from his frustrated outburst about “fake news” and insistence of saying grace over every meal down to the particular style of wraparound sunglasses he favors. He embodies a certain instinctive obstinance, a habit of holding on to what he knows and only what he knows, no matter how much the world might change around him. While the people Bill meets in France tend to react as though they’re anticipating an ugly American, the truth is that Bill isn’t the kind of guy who’d go there at all, given a choice. He’s in Marseilles to see his daughter, Allison (Abigail Breslin), who’s in prison for killing her girlfriend, Lina, while there as an exchange student. It’s a crime she insists she’s innocent of, and, five years into her sentence, she’s come across a tenuous new lead she asks her father to pass along to her lawyer, though he ends up taking up the investigation himself.

Stillwater is the new movie from director Tom McCarthy, and it feels like one he’s spent his career preparing for — an enthralling, exasperating, and, above all else, ambitious affair that doesn’t soften or demand sympathy for its difficult main character but does insist on according him his full humanity. McCarthy is best known for 2015’s Spotlight , which won Best Picture, but most of his work as a director has been devoted to the idea of battling back first impressions to get at the complexity of individuals. Each of his early indies — The Station Agent , The Visitor , and Win Win — use a premise of almost-perverse hokiness as the basis for a subdued character study of enormous generosity. Stillwater is a sprawling realization of that same approach, teasing a tawdry international crime thriller and then offering, instead, a portrait of a man trying to make up for past regrets with one big swing and constantly frustrated by his inability to meet the standards he’s set for himself. Bill spends a good part of Stillwater looking for redemption, but the film is more interested in the idea of learning to live with your mistakes.

Bill’s relationship with Allison has been shaped by those mistakes, and we come to understand that she counts on him as her point of contact with the outside world without really trusting him. McCarthy started off as an actor, and he has a way of writing for great performances that seems counterintuitive at first because his movies are so averse to grandstanding or big monologues. But he approaches his characters like they’re iceberg tips, the bulk of their lives a submerged but solid presence that can be sensed, even if it’s mostly unseen. Details about Allison’s childhood and Bill’s drug- and drink-fueled absenteeism emerge slowly from both of them, and it’s clear that while Bill’s been showing up for her regularly, Allison wouldn’t be surprised if he stopped at any moment. He still thinks of a relationship as something that can be fixed rather than something that’s nurtured and maintained, and his eagerness to clear his daughter’s name (while lying to her about her attorney’s inaction) speaks to preference for the cleanness of action. For a while, his determination is effective, and Damon is particularly deft at showing how Bill’s doggedness works without giving the character’s efforts any fish-out-of-water cutesiness.

His blunt-force approach carries him forward until it doesn’t, and when Bill’s amateur detective work stalls out, the film takes a startling turn toward the domestic by way of Virginie ( Call My Agent! ’s Camille Cottin), a Parisian transplant who starts giving Bill translation help, and her ebullient daughter, Maya (the wonderful Lilou Siauvaud). Virginie is part of the local theater scene and has a touch of kamikaze do-gooderism that leads her to open her home to a relative stranger. Her Gallic bohemianism neither overlaps with nor lines up in opposition to Bill’s blue-collar stolidity. It’s her friend who asks if Bill voted for Trump and who’s briefly stymied by his response that he didn’t vote at all because his criminal record forbids it. If it’s never clear how much of a willing enlistee Bill is in his country’s ongoing culture war, the film is also aware of the fact that those schisms don’t export neatly. Bill, still scarred from the way Allison’s crime inflamed press attention because her lover was Arab and female, has no idea what to make of the way that a professor at her school casts her as a privileged American dating a poor girl from the inner city. But Allison didn’t grow up with money, Bill protests, and the man avers that she was nevertheless the one with power in the relationship and that “there is a lot of resentment toward the educational elite.”

Allison wanted to get far away from her father and from everything she knew, but one of the themes of the movie is that she’s more like Bill than she wants to admit. Stillwater can’t get away from its own origins either in the end, and after a delicate and lovely middle section in which the film liberates itself from any obligations to address the murder as something other than an intractable fact, it surrenders to obligations toward plot again. It’s a development that feels as inevitable as a visa expiring, with everyone having to take up the narrative that’s the ostensible reason the film exists, even if it feels artificial compared to what’s come before. At the start of Stillwater , Bill rides home from a post-storm cleanup job back in Oklahoma, and as two of his colleagues talk in subtitled Spanish, the audience is invited into a conversation Bill doesn’t understand. One man marvels at the fact that the destroyed houses are likely to be rebuilt just as they were. “I don’t think Americans like change,” the other observes, to which the first replies, “I don’t think a tornado cares what Americans think.” It’s a discussion that feels like it could apply to the movie they’re a part of, one that lays waste to expectations but ultimately can’t help but go back to the way things always are.

More Movie Reviews

- When an American Pursues Bulgarian Dreams

- Rust Didn’t Choose to Echo Its Tragedy, But It Courses Through the Film

- Wicked Is As Enchanting As It Is Exhausting

- movie review

- tom mccarthy

- abigail breslin

Most Viewed Stories

- Cinematrix No. 240: November 21, 2024

- A.J., Big Justice, and Rizzler Bring the BOOM! to Jimmy Fallon

- The Extremely Chaotic Life of Jamian Juliano-Villani

- Every Taylor Sheridan TV Show, Ranked

- The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Season-Premiere Recap: Separation Anxiety

Most Popular

What is your email.

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

The Definitive Voice of Entertainment News

Subscribe for full access to The Hollywood Reporter

site categories

Matt damon in tom mccarthy’s ‘stillwater’: film review | cannes 2021.

The star plays an Oklahoma oil worker who travels to Marseille to help Abigail Breslin as his imprisoned daughter in this cross-cultural drama.

By David Rooney

David Rooney

Chief Film Critic

- Share on Facebook

- Share to Flipboard

- Send an Email

- Show additional share options

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Reddit

- Share on Tumblr

- Share on Whats App

- Print the Article

- Post a Comment

Tom McCarthy cites Mediterranean noirs as the inspiration for Stillwater , but there’s little of that mystique in this uneven ‘90s throwback, despite the mostly untapped potential of its atmospheric setting in the French port city of Marseille. Matt Damon gives a solid performance as an unemployed Oklahoma oil rig worker with a messy past, determined to do right by the daughter stuck in prison for a murder she claims she didn’t commit. But that story is clunky, old-fashioned and predictable when it’s not implausible. In any case, it’s less involving than the shot at renewal the failed family man gets with a French single mother.

The latter role, Virginie, is played by Call My Agent! lead Camile Cottin in a quietly luminous performance, juggling French and English dialogue with the same relaxed warmth. As Damon’s Bill Baker grows closer to Virginie and her 9-year-old daughter Maya (Lilou Siauvaud, a charming natural), this reticent man who wears his disappointment like a heavy overcoat slowly opens up to the possibilities of a life he had thought off-limits. That thread taps into the same kind of sensitively observed cross-cultural connections McCarthy explored in The Visitor , which, along with The Station Agent , remains his most accomplished work as director — regardless of that best picture Oscar for Spotlight .

Related Stories

Chinese director guan hu on releasing 'black dog' and 'a man and a woman' in the same year: "both films are simply about life", jennifer lopez supports her son's wrestling dreams in 'unstoppable' trailer.

Release date : Friday, July 30 Venue : Cannes Film Festival (Out of Competition) Cast : Matt Damon, Abigail Breslin, Camille Cottin, Lilou Siauvaud, Idir Azougli, Deanna Dunagan, Anne Le Ny, Moussa Maaskri, Naidra Ayadi, Nassiriat Mohamed, Mahia Zrouki Director : Tom McCarthy Screenwriters : Tom McCarthy, Marcus Hinchey, Thomas Bidegain, Noé Debré

Unfortunately, the A plot keeps dragging the movie down. Following its out of competition premiere in Cannes , this late July Focus release looks likely to make only a brief theatrical detour en route to streaming platforms.

Scripted by McCarthy and Marcus Hinchey with French writers Thomas Bidegain and Noé Debré, best known for their collaborations with Jacques Audiard, the screenplay’s earliest draft is from a decade ago and it does indeed play like something that’s been gathering dust in a drawer. There are allusions to current-day red-state America in the blinkered worldview that is part of Bill’s baggage, but that contemporary veneer is undernourished and the story’s political teeth have no bite.

Bill’s daughter Allison ( Abigail Breslin ) is five years into a nine-year sentence for the murder of Lina, the French Arab girlfriend she met while attending college in Marseille. Allison’s mother committed suicide for reasons never revealed, and the declining health of the maternal grandmother who raised her (Deanna Dunagan) means she can no longer travel. So Bill flies to Marseille as often as he can, delivering supplies, picking up her laundry and praying for Allison even though her affection for him seems muted. He was a screw-up before going into recovery for alcohol and drugs, but we only ever get generic hints about the reasons for her coolness toward him.

When Allison learns new information about Lina’s murder, implicating a young man named Akim from the projects, she asks her dad to deliver a letter to her lawyer Leparq (Anne Le Ny), requesting that she have the case reopened. But Leparq declines, pointing out that hearsay is not considered evidence. So while Bill keeps this from Allison, he makes it his mission to find Akim and prove his worth to his daughter. This despite her having made clear in her letter to the lawyer that she considers her father incapable and untrustworthy.

The language barrier and a lack of understanding of how the different social strata of Marseille work make his task a difficult one. But he gets help when he strikes up a friendship with theater actress Virginie, who has a habit of adopting causes.

Unfurling over a sluggish two hours plus, Stillwater is least convincing when McCarthy attempts to build suspense, with most of that work being done by Mychael Danna’s score. The late plot twists become almost risible, once Akim (Idir Azougli) enters the picture.

Part of the problem also is that there’s never much reason to invest in Allison, despite the heavy burden Bill clearly carries. Her case was big news at the time, and in a town where poverty and race draw sharp dividing lines, the sentiment of neither public nor press was much in favor of “the American lesbian.” Breslin has a few tender moments when she gets reacquainted with her father and his new adoptive family during a day release. But mostly, Allison remains remote as a character, especially when she blurts out heavy-handed lines like, “Life is brutal.” The fact that she might not be entirely blameless in Lina’s death should make her more interesting, not less.

Considering that Bidegain was a co-writer on Audiard’s great prison drama A Prophet , an enthralling representation of Muslim identity in a French microcosm, the race elements here are fairly basic. Liberal-minded Virginie bristles at the indiscriminate urge of many to put another Arab kid behind bars as they get closer to tracking down Akim, while for Bill, that kind of kneejerk racism is so familiar he barely notices it.

But those differences are also what makes the gradual transition from friendship to romance of Bill and Virginie so disarming. He’s a religious man who literally wears his patriotism on his sleeve in a bald eagle tattoo. He’s also the owner of not one but two guns, the idea of which Virginie finds incomprehensible. In one amusing scene, while her friend Nedjma (Naidra Ayadi) is helping them with some Instagram detective work, she asks Bill if he voted for Trump. He says only that he didn’t vote because of his arrest record.

Damon finds understated humor in this uncultured man who is nudged for the first time in his life to see himself — and by extension Allison — as the outsiders, the way the rest of the world sees Americans. A telling moment in an early scene finds him in the back of a van with a tornado cleanup crew chattering away in Spanish, while he sits in absent silence. His time in Marseille shows in subtle ways that he’s learning to see beyond otherness, and Damon never overplays that softening of Bill’s closed-off views.

The actor’s many scenes with young Siauvaud are quite lovely, avoiding cutesiness while gently showing Bill’s pleasure in getting to experience the kind of bonding he skipped with his own daughter. His awkward comments when Virginie invites him to watch a rehearsal of a play she’s doing show how completely he’s outside his comfort zone. (“What am I gonna do in a fuckin’ theater?” he asks Allison earlier, with blunt self-awareness.) But the melting of the distance between them is so well played by Damon and Cottin you keep wishing this was their story. A gorgeous interlude in which they dance to Sammi Smith’s “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” with Maya demanding to get in on the act, further cements that desire.

Bill may have stayed on in Marseille to remain in Allison’s life even after her rejection. But it’s the different version of himself he discovers there that provides the often clumsy Stillwater with some grace and heart.

Full credits

Venue: Cannes Film Festival (Out of Competition) Cast: Matt Damon, Abigail Breslin, Camille Cottin, Lilou Siauvaud, Idir Azougli, Deanna Dunagan, Anne Le Ny, Moussa Maaskri, Naidra Ayadi, Nassiriat Mohamed, Mahia Zrouki Production companies: Participant, DreamWorks Pictures, Slow Pony, Anonymous Content, in association with 3Dot Productions, Supernatural Pictures Distribution: Focus Features Director: Tom McCarthy Screenwriters: Tom McCarthy, Marcus Hinchey, Thomas Bidegain, Noé Debré Producers: Steve Golin, Tom McCarthy, Jonathan King, Liza Chasin Executive producers: Jeff Skoll, David Linde, Robert Kessel, Mari Jo Winkler-Ioffreda, Thomas Bidegain, Noé Debré Director of photography: Masanobu Takayanagi Production designer: Philip Messina Costume designer: Karen Muller Serreau Music: Mychael Danna Editor: Tom McArdle Casting: Kerry Barden, Paul Schnee, Anne Fremiot

THR Newsletters

Sign up for THR news straight to your inbox every day

More from The Hollywood Reporter

How does bafta choose its breakthroughs a glimpse into finding tomorrow’s top talent, doc ‘of color and ink’ unravels the mystery surrounding “the picasso of china”, ridley scott explains why his ‘gladiator’ emperors are nuts: “no wonder…”, ‘the brutalist’ dp lol crawley to be honored with rotterdam’s robby müller award, ‘parthenope’ trailer: sun, sea and sex feature in paolo sorrentino’s love letter to naples, why european cinema is on a critical high, but also a commercial low.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

"Stillwater" moves the action to the French port city of Marseilles and introduces us to Bill's daughter, Allison (Abigail Breslin), after she's already served five years of a nine-year prison sentence for the murder of her lover, a young Muslim woman.

Stillwater isn't perfect, but its thoughtful approach to intelligent themes -- and strong performances from its leads -- give this timely drama a steadily building power. Read Critics Reviews...

Like “Nomadland” and any number of Sundance movies, “Stillwater” seizes on the classic figure of the American stoic, the rugged individualist whose self-reliance has become a trap, a dead ...

‘Stillwater’ Review: Matt Damon Gets to the Heart of How the World Sees Americans Right Now. 'Spotlight' director Tom McCarthy collaborates with top French screenwriter Thomas Bidegain in this...

'Stillwater' Movie Review: Starring Matt Damon. TV & Movies. ‘Stillwater’ Examines Lives in Wreckage, With Matt Damon at the Center. The sly power of director Tom McCarthy’s style is to...

At the beginning of “Stillwater,” Bill Baker (Matt Damon), an Oklahoma construction worker, stands amid the remnants of a house that’s recently been destroyed by a tornado.

In Stillwater, Matt Damon plays an Oklahoma oil rig worker who travels to France to help his daughter, who is in prison for a murder she says she didn't commit.