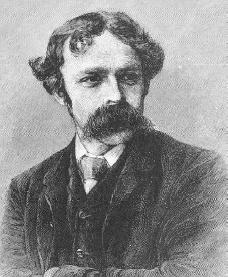

Nathaniel Hawthorne

(1804-1864)

Who Was Nathaniel Hawthorne?

Nathaniel Hawthorne was an American short story writer and novelist. His short stories include "My Kinsman, Major Molineux" (1832), "Roger Malvin's Burial" (1832), "Young Goodman Brown" (1835) and the collection Twice-Told Tales . He is best known for his novels The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851). His use of allegory and symbolism make Hawthorne one of the most studied writers.

Born on July 4, 1804, in Salem Massachusetts, Hawthorne’s life was steeped in the Puritan legacy. An early ancestor, William Hathorne, first emigrated from England to America in 1630 and settled in Salem, Massachusetts, where he became a judge known for his harsh sentencing. William’s son, John Hathorne, was one of three judges during the Salem Witch Trials in the 1690s. Hawthorne later added a “w” to his name to distance himself from this side of the family.

Hawthorne was the only son of Nathaniel and Elizabeth Clark Hathorne (Manning). His father, a sea captain, died in 1808 of yellow fever while at sea. The family was left with meager financial support and moved in with Elizabeth’s wealthy brothers. A leg injury at an early age left Hawthrone immobile for several months during which time he developed a voracious appetite for reading and set his sights on becoming a writer.

With the aid of his wealthy uncles, young Hawthorne attended Bowdoin College from 1821 to 1825. There he met and befriended Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and future president Franklin Pierce . By his own admission, he was a negligent student with little appetite for study.

Short Stories and Collections

While attending college, Hawthorne missed his mother and two sisters terribly and upon graduation, returned home for a 12-year stay. During this time, he began to write with purpose and soon found his “voice” self-publishing several stories, among them "The Hollow of the Three Hills" and "An Old Woman’s Tale ." By 1832, he had written " My Kinsman, Major Molineux" and "Roger Malvin’s Burial ," two of his greatest tales and in 1837, Twice Told Tales . Though his writing brought him some notoriety, it didn’t provide a dependable income and for a time he worked for the Boston Custom House weighing and gaging salt and coal.

Budding Success and Marriage

Hawthorne ended his self-imposed seclusion at home about the same time he met Sophia Peabody, a painter, illustrator and transcendentalist. During their courtship, Hawthorne spent some time at the Brook Farm community where he got to know Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau . He didn’t find transcendentalism to his favor but living in the commune allowed him to save money for his impending marriage to Sophia. After a long courtship, partially prolonged by Sophia’s poor health, the couple was married on July 9, 1842. They quickly settled in Concord, Massachusetts, and rented Old Manse, owned by Emerson. In 1844, the first of their three children was born.

'The Scarlet Letter'

With mounting debt and a growing family, Hawthorne moved to Salem. A life-long Democrat, political connections helped him land a job as a surveyor in the Salem Custom House in 1846, providing his family some needed financial security. However, when Whig President Zachary Taylor was elected, Hawthorne lost his appointment due to political favoritism. The dismissal turned into a blessing giving him time to write his masterpiece, The Scarlet Letter , the story of two lovers who clashed with the Puritan moral law. The book was one of the first mass-produced publications in the United States and its wide distribution made Hawthorne famous.

Other Books

Never feeling comfortable living in Salem, Hawthorne was determined to take his family out of the town’s Puritan trappings. They moved to Red House in Lenox, Massachusetts, where he formed a close friendship with Moby Dick author Herman Melville . During this time, Hawthorne enjoyed his most productive period as a writer publishing The House of the Seven Gables , Blithedale Romance and Tanglewood Tales .

Years Abroad

During the 1852 election, Hawthorne wrote a campaign biography for his college friend Pierce. When Pierce was elected president, he appointed Hawthorne an American Consul to Britain as a reward. The Hawthorne’s stayed in England from 1853-1857. This period served as inspiration for Hawthorne’s novel Our Old Home .

After serving as consul, Hawthorne took his family on an extended vacation to Italy and then back to England. In 1860, he finished his last novel The Marble Faun . That same year Hawthorne moved his family back to the United States and took permanent residence at The Wayside in Concord, Massachusetts.

Final Years and Death

After 1860, it was becoming apparent that Hawthorne was moving past his prime. Striving to rekindle his earlier productivity, he found little success. Drafts were mostly incoherent and left unfinished. Some even showed signs of psychic regression. His health began to fail and he seemed to age considerably, hair turning white and experiencing slowness of thought. For months, he refused to seek medical help and died in his sleep on May 19, 1864, in Plymouth, New Hampshire.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Birth Year: 1804

- Birth date: July 4, 1804

- Birth State: Massachusetts

- Birth City: Salem

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Author Nathaniel Hawthorne is best known for his novels 'The Scarlet Letter' and 'The House of Seven Gables,' and also wrote many short stories.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- Death Year: 1864

- Death date: May 19, 1864

- Death State: New Hampshire

- Death City: Plymouth

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Nathaniel Hawthorne Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/nathaniel-hawthorne

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 31, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- Happiness is as a butterfly which, when pursued, is always beyond our grasp, but which if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you.

- No man, for any considerable period, can wear one face to himself and another to the multitude, without finally getting bewildered as to which may be the true.

Famous Authors & Writers

How Did Shakespeare Die?

A Huge Shakespeare Mystery, Solved

Shakespeare Wrote 3 Tragedies in Turbulent Times

The Mystery of Shakespeare's Life and Death

Was Shakespeare the Real Author of His Plays?

20 Shakespeare Quotes

William Shakespeare

The Ultimate William Shakespeare Study Guide

Suzanne Collins

Alice Munro

Agatha Christie

- World Biography

Nathaniel Hawthorne Biography

Born: July 4, 1804 Salem, Massachusetts Died: May 19, 1864 Plymouth, New Hampshire American writer

The work of American fiction writer Nathaniel Hawthorne was based on the history of his Puritan ancestors and the New England of his own day. Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables are classics of American literature.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in Salem, Massachusetts, on July 4, 1804, into the sixth generation of his Salem family. His ancestors included businessmen, judges, and seamen—all Puritans, a strict religious discipline. Two aspects of his background especially affected his imagination and writing career. The Hathornes (Nathaniel added the "w" to the name) had been involved in religious persecution (intense harassment) with their first American ancestor, William. Another ancestor, John Hathorne, was one of the three judges at the seventeenth-century Salem witchcraft trials, where dozens of people were accused of, and later executed for, being "witches."

Nathaniel's father, a sea captain, died in 1808, leaving his wife and three children dependent on relatives. Nathaniel, the only son, spent his early years in Salem and in Maine. A leg injury forced Hawthorne to remain immobile for a considerable period, during which he developed an exceptional taste for reading and thinking. His childhood was calm, a little isolated but far from unhappy, especially since as a handsome and attractive only son he was idolized by his mother and his two sisters.

Years in seclusion

Returning from Bowdoin, Hawthorne spent the years 1825 to 1837 in his mother's Salem household. Later he looked back upon these years as a period of dreamlike isolation and solitude, spent in a haunted room. During these "solitary years" he learned to write tales and sketches that are still unique.

Recent biographers have shown that this period of Hawthorne's life was less lonely than he remembered it to be. In truth, he did have social engagements, played cards, and went to the theatre. Nevertheless, he consistently remembered these twelve years as a strange, dark dream, though his view of the influence of these years varied.

Writing short stories

Most of Hawthorne's early stories were published anonymously (without an author's name) in magazines and giftbooks. In 1837 the publication of Twice-Told Tales somewhat lifted this spell of darkness. After Twice-Told Tales he added two later collections, Mosses from an Old Manse (1846) and The Snow-Image (1851), along with Grandfather's Chair (1841), a history of New England for children. Hawthorne's short stories came slowly but steadily into critical favor, and the best of them have become American classics.

By his own account it was Hawthorne's love of his Salem neighbor Sophia Peabody that brought him from his "haunted chamber" out into the world. His books were far from profitable enough to support a wife and family, so in 1838 he went to work in the Boston Custom House and then spent part of 1841 in the famous Brook Farm community in hopes of finding a pleasant and economical home for Sophia and himself.

Hawthorne and Sophia, whom he finally married in 1842, resorted not to Brook Farm but to the Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, where they spent several years of happiness in as much quiet living as they could achieve. Concord was home to Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), and Ellery Channing (1780–1842), and Hawthorne was in frequent contact with these important thinkers, though he did not take to their philosophical lifestyles.

Writing the novels

Facing the world once more, Hawthorne obtained in 1846 the position of surveyor (one who maps out new lands) in the Salem Custom House, but was relieved of this position in 1848 because of his political ties. His dismissal, however, turned out to be a blessing, since it gave him time in which to write his greatest success, The Scarlet Letter.

The period 1850 to 1853 was Hawthorne's most productive, as he wrote The House of the Seven Gables and The Blithedale Romance, along with A Wonder Book (1852) and Tanglewood Tales (1853). During 1850 the Hawthornes lived at the Red House in Lenox in the Berkshire Hills, and Hawthorne formed a memorable friendship with novelist Herman Melville (1819–1912). The association was more important to Melville than to Hawthorne, since Melville was fifteen years younger and the much more impressionable (easily influenced) of the two men. It left its mark in dedication of his Moby-Dick, and in some wonderful letters.

Years abroad

In 1852 Franklin Pierce was elected president of the United States, and Hawthorne, who wrote his campaign biography, was appointed to the important overseas post of American consul (advisor) at Liverpool, England. He served in this post from 1853 to 1857. These English years resulted in Our Old Home (1863), a volume drawn from the since-published "English Note-Books."

In 1857 the Hawthornes left England for Italy, where they spent their time primarily in Rome and Florence. They returned to England, where Hawthorne finished his last and longest complete novel, The Marble Faun (1860). They finally returned to the United States, after an absence of seven years, and took up residence in their first permanent home, The Wayside, at Concord.

Although he had always been an exceptionally active man, Hawthorne's health began to fail him. Since he refused to submit to any thorough medical examination, the details of his declining health remain mysterious. Hawthorne died on May 19, 1864. He had set off for the New Hampshire hills with Franklin Pierce, an activity he had always enjoyed, hoping to regain his health. But he died the second night in Plymouth, New Hampshire, presumably in his sleep.

Hawthorne once said that New England was enough to fill his heart, yet he sought the broader experience of Europe. Modest in expectations, he had nonetheless desired to live fully. Hawthorne's life and writings present a complex puzzle. A born writer, he suffered the difficulties of his profession in early-nineteenth-century America, an environment unfriendly to artists.

For More Information

Bloom, Harold, ed. Nathaniel Hawthorne. New York: Chelsea House, 1986.

Mellow, James R. Nathaniel Hawthorne in His Times. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980. Reprint, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Miller, Edward Haviland. Salem Is My Dwelling Place. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

- Humanities ›

- Literature ›

- Classic Literature ›

- Authors & Texts ›

Biography of Nathaniel Hawthorne

New England's Most Prominent Novelist Focused on Dark Themes

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

Nathaniel Hawthorne was one of the most admired American authors of the 19th century, and his reputation has endured to the present day. His novels, including The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables , are widely read in schools.

A native of Salem, Massachusetts, Hawthorne often incorporated the history of New England, and some lore related to his own ancestors, into his writings. And by focusing on themes such as corruption and hypocrisy he dealt with serious issues in his fiction.

Often struggling to survive financially, Hawthorne worked at various times as a government clerk, and during the election of 1852 he wrote a campaign biography for a college friend, Franklin Pierce . During Pierce's presidency Hawthorne secured a posting in Europe, working for the State Department.

Another college friend was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. And Hawthorne was also friendly with other prominent writers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Herman Melville . While writing Moby Dick , Melville felt the influence of Hawthorne so profoundly that he changed his approach and eventually dedicated the novel to him.

When he died in 1864, the New York Times described him as "the most charming of American novelists, and one of the foremost descriptive writers in the language."

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born July 4, 1804, in Salem, Massachusetts. His father was a sea captain who died while on a voyage to the Pacific in 1808, and Nathaniel was raised by his mother, with the help of relatives.

A leg injury sustained during a game of ball caused young Hawthorne to restrict his activities, and he became an avid reader as a child. In his teens he worked in the office of his uncle, who ran a stagecoach, and in his spare time he dabbled with trying to publish his own small newspaper.

Hawthorne entered Bowdoin College in Maine in 1821 and began writing short stories and a novel. Returning to Salem, Massachusetts, and his family, in 1825, he finished a novel he had started in college, Fanshawe . Unable to get a publisher for the book, he published it himself. He later disavowed the novel and tried to stop it from circulating, but some copies did survive.

Literary Career

During the decade after college Hawthorne submitted stories such as "Young Goodman Brown" to magazines and journals. He was often frustrated in his attempts to get published, but eventually a local publisher and bookseller, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody began to promote him.

Peabody's patronage introduced Hawthorne to prominent figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson. And Hawthorne would eventually marry Peabody's sister.

As his literary career began to show promise, he secured, through political friends, an appointment to a patronage job in the Boston custom house. The job provided an income, but was fairly boring work. After a change in political administrations cost him the job, he spent about six months at Brook Farm, a Utopian community near West Roxbury, Massachusetts.

Hawthorne married his wife, Sophia, in 1842, and moved to Concord, Massachusetts, a hotbed of literary activity and home to Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau. Living in the Old Manse, the house of Emerson's grandfather, Hawthorne entered a very productive phase and he wrote sketches and tales.

With a son and a daughter, Hawthorne moved back to Salem and took another government post, this time at the Salem custom house. The job mostly required his time in the mornings and he was able to write in the afternoons.

After the Whig candidate Zachary Taylor was elected president in 1848, Democrats like Hawthorne could be dismissed, and in 1848 he lost his posting at the custom house. He threw himself into the writing of what would be considered his masterpiece, The Scarlet Letter .

Fame and Influence

Seeking an economical place to live, Hawthorne moved his family to Stockbridge, in the Berkshires. He then entered the most productive phase of his career. He finished The Scarlet Letter , and also wrote The House of the Seven Gables.

While living in Stockbridge, Hawthorne befriended Herman Melville, who was struggling with the book that became Moby Dick. Hawthorne's encouragement and influence was very important to Melville, who openly acknowledged his debt by dedicating the novel to his friend and neighbor.

The Hawthorne family was happy in Stockbridge, and Hawthorne began to be acknowledged as one of America's greatest authors.

Campaign Biographer

In 1852 Hawthorne's college friend, Franklin Pierce, received the Democratic Party's nomination for president as a dark horse candidate . In an era when Americans often did not know much about the presidential candidates, campaign biographies were a potent political tool. And Hawthorne offered to help his old friend by quickly writing a campaign biography.

Hawthorne's book on Pierce was published a few months before the November 1852 election, and it was considered very helpful in getting Pierce elected. After he became president, Pierce paid back the favor by offering Hawthorne as diplomatic post as the American consul in Liverpool, England, a thriving port city.

In the summer of 1853 Hawthorne sailed for England. He worked for the U.S. government until 1858, and while he kept a journal he didn't focus on writing. Following his diplomatic work he and his family toured Italy and returned to Concord in 1860.

Back in America, Hawthorne wrote articles but did not publish another novel. He began to suffer ill health, and on May 19, 1864, while on a trip with Franklin Pierce in New Hampshire, he died in his sleep.

- A Reading List of the Best 19th Century Novels

- Biography of Herman Melville, American Novelist

- Biography of Washington Irving, Father of the American Short Story

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: American Transcendentalist Writer and Speaker

- Biography of Louisa May Alcott, American Writer

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- Biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson, American Essayist

- Biography of Samuel Johnson, 18th Century Writer and Lexicographer

- The Life and Work of H.G. Wells

- List of Works by James Fenimore Cooper

- The Life and Works of Honoré de Balzac, French Novelist

- What Were Mark Twain's Inventions?

- Biography of George Eliot, English Novelist

- Life of Wilkie Collins, Grandfather of the English Detective Novel

- Mark Twain: His Life and His Humor

- Sinclair Lewis, First American to Win Nobel Prize for Literature

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born on July 4, 1804, in Salem, Massachusetts. His family, the Hathornes, had lived in Salem since the seventeenth century. A descendent of the Puritan judges William Hathorne and John Hathorne, a judge who oversaw the Salem Witch Trials, Hawthorne chose to add the “w” to his name when he was in his early twenties. Hawthorne grew up with his mother and uncles in Salem and Raymond, Maine. His father, a ship’s captain, died of yellow fever in 1808. Many of Hawthorne’s childhood poems and stories were concerned with sailing and the sea. Hawthorne suffered temporary paralysis during his youth and studied literature at home with the lexicographer Joseph Emerson Worcester. Hawthorne then attended Bowdoin College from 1821 to 1825, where he wrote his early poems and a novel. He was classmates with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow , and they developed a friendship later in life. Hawthorne moved back to Salem after graduation.

While best known for his novels, letters, and short stories, Hawthorne also wrote a few poems, notably “The Ocean,” published in the Salem Gazette in 1825, and “Oh Could I Raise the Darken’d Veil,” which appeared in 1820 in the Spectator , a weekly newspaper that Hawthorne created and edited, starting in the summer of that year.

Hawthorne is best known for his four major romances: The Marble Faun (Ticknor, Reed, & Fields, 1860); The Blithedale Romance (Ticknor, Reed, & Fields, 1852); The House of the Seven Gables (Ticknor, Reed, & Fields, 1851); and, most importantly, The Scarlet Letter (Ticknor, Reed, & Fields, 1850). He was also a successful short story writer. He gained fame when he published his stories in the collection Twice-Told Tales (American Stationers Co., 1837). During this period, Hawthorne began to attach his own name to his prose. His best-known works are “Ethan Brand” (Ticknor, Reed, & Fields, 1850); “The Birth-Mark,” published in James Russell Lowell ’s literary periodical, The Pioneer , in 1843; “Young Goodman Brown,” published in The New-England Magazine in 1835; and “My Kinsman, Major Molineux,” published in the illustrated gift book The Token and Atlantic Souvenir in 1832.

In 1986 Hawthorne was inducted into The American Poets’ Corner, joining the symbolic American pantheon of letters, alongside Robert Frost , the first twentieth-century poet to be inducted. Hawthorne was also recognized and admired by his contemporaries. Herman Melville gave Hawthorne’s short stories rave reviews, in addition to dedicating Moby Dick to him. However, Melville’s view of Hawthorne soured later in life, and Melville presented him unflatteringly in his poem “Clarel.” Longfellow wrote a review of Twice-Told Tales , in which he called Hawthorne a “new star” who wrote with “the heaven of poetry.” Henry James wrote a biographical critical essay on Hawthorne, describing him as “a beautiful, natural, original genius […] no one has had just that vision of life, and no one has had a literary form that more successfully expressed his vision […] he was not simply a poet. He combined in a singular degree the spontaneity of the imagination with a haunting care for moral problems. Man’s conscience was his theme, but he saw it in the light of a creative fancy which added, out of its own substance, an interest, and, I may almost say, an importance.”

In 1838 Hawthorne became engaged to his future wife, illustrator Sophia Peabody. While his writing often brought him satisfying recognition, it secured him very little income and Hawthorne often struggled to make ends meet, taking various positions throughout his life. As he said in 1820: “I have almost given up writing Poetry […] No Man can be a Poet & a Book-Keeper at the same time.” Hawthorne sought work at the Boston Custom House in 1839, as well as at the agricultural cooperative Brook Farm in 1841. By 1842 Hawthorne’s writing provided enough income for him to marry Sophia, and they settled for three years in Concord, Massachusetts. Hawthorne’s neighbors were Ralph Waldo Emerson , Henry David Thoreau , and the philosopher and educator Bronson Alcott, making the village the leading center of Transcendentalism. While Hawthorne associated with the thinkers and shared many of their philosophies, he preferred the company of Franklin Pierce, his old college friend, who later became the fourteenth U.S. president. Hawthorne wrote a campaign biography on Pierce, titled Life of Franklin Pierce (Ticknor, Reed, & Fields, 1852). When Pierce became president in 1853, Hawthorne was given the position of U.S. consul in Liverpool. He resigned in 1857 and spent his later years traveling in France and Italy and writing.

Hawthorne died on May 19, 1864, in Plymouth, New Hampshire, while on a mountain tour with Pierce. Hawthorne is buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord.

Related Poets

Newsletter sign up.

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Nathaniel Hawthorne

Introduction, general overviews.

- Primary Texts

- Bibliographies

- Hawthorne’s Reading

- Personal Reminiscences

- Hawthorne as Subject and Artist

- Hawthorne’s Family

- Race, Politics, and Culture

- Backgrounds

- The Scarlet Letter

- The Short Stories

- Hawthorne and Melville

- Film and Theater

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- American Literary Biography

- Charles Brockden Brown

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- Herman Melville

- Sophia Peabody Hawthorne

- Washington Irving

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Mary McCarthy

- William Apess

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Nathaniel Hawthorne by Michael Martin , Samuel Coale LAST REVIEWED: 28 August 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 28 August 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199827251-0096

Unlike Dickinson, Melville, and Thoreau, who are now viewed as classic American authors, Nathaniel Hawthorne and his work were never completely ignored by the public and various critics. Hawthorne (b. 1804–d. 1864)—was born Nathaniel Hathorne in Salem, Massachusetts, and came from a long line of farmers and sailors. His most notorious ancestor was John Hathorne, a judge at the Salem witch trials in 1692, which helps explain his constant struggle with the Calvinistic sense of determinism and tragic fate in his fiction. He married Sophia Peabody in 1842 and sought and accepted political appointments to the custom house in Boston and Salem and finally as consul to Liverpool, England, as a result of his campaign biography of President Franklin Pierce, a fellow Bowdoin graduate. He spent a twelve-year apprenticeship in his mother’s family’s home (1825–1837)—his father died when he was four—writing short stories, sketches, and essays, which led to his romantic legend as a hermit and recluse. Success came with The Scarlet Letter in 1850 and went on to include The House of the Seven Gables (1851), The Blithedale Romance (1852), and The Marble Faun (1860) as well as collections of his short fiction and Our Old Home (1863). Early on, critics wrestled with the relationship between his genteel style and his “morbid” subjects, biographers creating either a very pragmatic Hawthorne or a reclusive ghost. The New Critics delved into the psychological and proto-theological themes in his work and trumpeted his use of contradiction, paradox, and the polarized perspectives of his characters, thus concentrating on such tales as “The Minister’s Black Veil” and “My Kinsman, Major Molineux” at the expense of the popular ones in his lifetime, such as “Little Annie’s Ramble,” “A Rill from the Town Pump,” and “Sunday at Home.” Friends such as Elizabeth Peabody and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow consistently praised his work, as did other writers such as Edgar Allan Poe (at first he praised and then disparaged it as too allegorical and thin) and Herman Melville. Criticism has always emphasized the dualisms in his work—good and evil, men and women, and Puritanism and romanticism—as well as his often contradictory responses to such historical issues as the Civil War, abolitionism, feminism, and the delicate political compromises, which upheld the status quo between North and South, of the 1850s. After his four-year stint in Liverpool, he traveled extensively in Italy and returned to Concord, Massachusetts, in 1860.

From an abundance of material, this list includes both books specifically on Hawthorne and his background, as well as others that place him in the wider realms of literary and cultural history. Hawthorne can be seen as his own man by critics in works such as Baym 1976 , James 1997 , and Woodberry 1902 and as a product of his era, the latter approach championed by critics in works such as Berlant 1991 , Moore 1998 , and Tompkins 1985 . Both overlap one another, but Tompkins’s book clearly opts for a cultural and historical approach and led to the discipline of cultural studies, begun in the late 1980s and continuing into contemporary times.

Baym, Nina. The Shape of Hawthorne’s Career . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1976.

An in-depth tracing of Hawthorne’s career as he constantly toyed with different personae, styles, and approaches, asserting that the stories we read today are the result of the pro-Freudian criticism after 1950. Examines the different phases that reveal how fluid and flexible Hawthorne was as an author, relying on different strategies at different times, as well as his complex attitude toward his strong female characters.

Berlant, Lauren. The Anatomy of National Fantasy: Hawthorne, Utopia, and Everyday Life . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Suggests that Hawthorne intentionally provided an antidote to American myths of self-reliance and autonomy. What seems natural is really fully textualized according to prior writers who may feel isolated in a country that is already a kind of artistic construct of myth and self-conscious traditions. For the more specialized critic of Hawthorne.

Coale, Samuel Chase. The Entanglements of Nathaniel Hawthorne: Haunted Minds and Ambiguous Approaches . Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2011.

Covers all of the major criticism and biographies of Hawthorne from 1828 to 2010 and tries to show how each is entangled with the other, thus undermining most polarized and dualistic interpretations of Hawthorne’s work and personality.

James, Henry. Hawthorne . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997.

James uses the word “provincial” so many times that it becomes clear that James is trying to pigeonhole Hawthorne in opposition to his own more cosmopolitan self and fiction. This first view of Hawthorne, both biographical and critical, written by a literary successor, emphasizes Hawthorne’s simplicity as the product of an unsophisticated culture: a worthwhile read for getting a sense of how he was valued at the time. James relied heavily on the French critics with little acknowledgment of them. Reprint of the 1879 edition.

Moore, Margaret B. The Salem World of Nathaniel Hawthorne . Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1998.

An excellent, full-bodied, impeccably researched book about Hawthorne’s family, his friends and neighbors, and rituals and events in his native town: including religious rivalries, murder trials, ancestry, African Americans, and the “fireside traditions” of telling tales and passing on legends. Hawthorne emerges as a pragmatic soul, deeply engaged with his society.

Pease, Donald E. Visionary Compacts: American Renaissance Writings in Cultural Context . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987.

Argues that Hawthorne constructed a sense of community in terms of the past and memory, however contradictory and paradoxical, in response to the weakening of myths of the American Revolution and the prospects of civil war. Discusses the social roles of many of Hawthorne’s characters in an effort to create a cultural and communal memory. A broad context for Hawthorne’s fiction.

Tompkins, Jane. Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790–1860 . New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Tompkins tends to suggest a cultural conspiracy led by New England white males to maintain Hawthorne as a cultural and literary icon. Yet her main approach of placing novels in their cultural and historical context continues to resonate in contemporary literary criticism.

Woodberry, George E. Nathaniel Hawthorne: American Men of Letters . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1902.

An early critical biography that emphasizes Hawthorne’s pragmatic side and connects his aloofness to New England culture. The criticism, separating man from artist, is surprisingly modern in its approach, anticipating the New Criticism in its close readings and discussion of Hawthorne’s narrative strategies, particularly in his use of allegory and the influence of Sir Walter Scott.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About American Literature »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Adams, Alice

- Adams, Henry

- African American Vernacular Tradition

- Agee, James

- Alcott, Louisa May

- Alexie, Sherman

- Alger, Horatio

- American Exceptionalism

- American Grammars and Usage Guides

- American Literature and Religion

- American Magazines, Early 20th-Century Popular

- "American Renaissance"

- American Revolution, Music of the

- Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones)

- Anaya, Rudolfo

- Anderson, Sherwood

- Angel Island Poetry

- Antin, Mary

- Anzaldúa, Gloria

- Austin, Mary

- Baldwin, James

- Barlow, Joel

- Barth, John

- Bellamy, Edward

- Bellow, Saul

- Bible and American Literature, The

- Bierce, Ambrose

- Bishop, Elizabeth

- Bourne, Randolph

- Bradford, William

- Bradstreet, Anne

- Brockden Brown, Charles

- Brooks, Van Wyck

- Brown, Sterling

- Brown, William Wells

- Butler, Octavia

- Byrd, William

- Cahan, Abraham

- Callahan, Sophia Alice

- Captivity Narratives

- Cather, Willa

- Cervantes, Lorna Dee

- Chesnut, Mary Boykin

- Chesnutt, Charles Waddell

- Child, Lydia Maria

- Chopin, Kate

- Cisneros, Sandra

- Civil War Literature, 1861–1914

- Clark, Walter Van Tilburg

- Connell, Evan S.

- Cooper, Anna Julia

- Cooper, James Fenimore

- Copyright Laws

- Crane, Stephen

- Creeley, Robert

- Cruz, Sor Juana Inés de la

- Cullen, Countee

- Culture, Mass and Popular

- Davis, Rebecca Harding

- Dawes Severalty Act

- de Burgos, Julia

- de Crèvecœur, J. Hector St. John

- Delany, Samuel R.

- Dick, Philip K.

- Dickinson, Emily

- Doctorow, E. L.

- Douglass, Frederick

- Dreiser, Theodore

- Dubus, Andre

- Dunbar, Paul Laurence

- Dunbar-Nelson, Alice

- Dune and the Dune Series, Frank Herbert’s

- Eastman, Charles

- Eaton, Edith Maude (Sui Sin Far)

- Eaton, Winnifred

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Eliot, T. S.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo

- Environmental Writing

- Equiano, Olaudah

- Erdrich (Ojibwe), Louise

- Faulkner, William

- Fauset, Jessie

- Federalist Papers, The

- Ferlinghetti, Lawrence

- Fiedler, Leslie

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott

- Frank, Waldo

- Franklin, Benjamin

- Freeman, Mary Wilkins

- Frontier Humor

- Fuller, Margaret

- Gaines, Ernest

- Garland, Hamlin

- Garrison, William Lloyd

- Gibson, William

- Gilman, Charlotte Perkins

- Ginsberg, Allen

- Glasgow, Ellen

- Glaspell, Susan

- González, Jovita

- Graphic Narratives in the U.S.

- Great Awakening(s)

- Griggs, Sutton

- Hansberry, Lorraine

- Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins

- Harte, Bret

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel

- Hawthorne, Sophia Peabody

- H.D. (Hilda Doolittle)

- Hellman, Lillian

- Hemingway, Ernest

- Higginson, Ella Rhoads

- Higginson, Thomas Wentworth

- Hughes, Langston

- Indian Removal

- Irving, Washington

- James, Henry

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jesuit Relations

- Jewett, Sarah Orne

- Johnson, Charles

- Johnson, James Weldon

- Kerouac, Jack

- King, Martin Luther

- Kirkland, Caroline

- Knight, Sarah Kemble

- Larsen, Nella

- Lazarus, Emma

- Le Guin, Ursula K.

- Lewis, Sinclair

- Literary Biography, American

- Literature, Italian-American

- London, Jack

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth

- Lorde, Audre

- Lost Generation

- Lowell, Amy

- Magazines, Nineteenth-Century American

- Mailer, Norman

- Malamud, Bernard

- Manifest Destiny

- Mather, Cotton

- Maxwell, William

- McCarthy, Cormac

- McCarthy, Mary

- McCullers, Carson

- McKay, Claude

- McNickle, D'Arcy

- Melville, Herman

- Merrill, James

- Millay, Edna St. Vincent

- Miller, Arthur

- Moore, Marianne

- Morrison, Toni

- Morton, Sarah Wentworth

- Mourning Dove (Syilx Okanagan)

- Mukherjee, Bharati

- Murray, Judith Sargent

- Native American Oral Literatures

- New England “Pilgrim” and “Puritan” Cultures

- New Netherland Literature

- Newspapers, Nineteenth-Century American

- Norris, Zoe Anderson

- Northup, Solomon

- O'Brien, Tim

- Occom, Samson and the Brotherton Indians

- Olsen, Tillie

- Olson, Charles

- Ortiz, Simon

- Paine, Thomas

- Piatt, Sarah

- Pinsky, Robert

- Plath, Sylvia

- Poe, Edgar Allan

- Porter, Katherine Anne

- Proletarian Literature

- Realism and Naturalism

- Reed, Ishmael

- Regionalism

- Rich, Adrienne

- Rivera, Tomás

- Robinson, Kim Stanley

- Roth, Henry

- Roth, Philip

- Rowson, Susanna Haswell

- Ruiz de Burton, María Amparo

- Russ, Joanna

- Sanchez, Sonia

- Schoolcraft, Jane Johnston

- Selzer, Richard

- Sentimentalism and Domestic Fiction

- Sexton, Anne

- Silko, Leslie Marmon

- Sinclair, Upton

- Smith, John

- Smith, Lillian

- Spofford, Harriet Prescott

- Stein, Gertrude

- Steinbeck, John

- Stevens, Wallace

- Stoddard, Elizabeth

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher

- Tate, Allen

- Terry Prince, Lucy

- Thoreau, Henry David

- Time Travel

- Tourgée, Albion W.

- Transcendentalism

- Truth, Sojourner

- Twain, Mark

- Tyler, Royall

- Updike, John

- Vallejo, Mariano Guadalupe

- Viramontes, Helena María

- Vizenor, Gerald

- Walker, David

- Walker, Margaret

- War Literature, Vietnam

- Warren, Mercy Otis

- Warren, Robert Penn

- Wells, Ida B.

- Welty, Eudora

- Wendy Rose (Miwok/Hopi)

- Wharton, Edith

- Whitman, Sarah Helen

- Whitman, Walt

- Whitman’s Bohemian New York City

- Whittier, John Greenleaf

- Wideman, John Edgar

- Wigglesworth, Michael

- Williams, Roger

- Williams, Tennessee

- Williams, William Carlos

- Wilson, August

- Winthrop, John

- Wister, Owen

- Woolman, John

- Woolson, Constance Fenimore

- Wright, Richard

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

IMAGES

VIDEO