- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Theoretical Framework

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Theories are formulated to explain, predict, and understand phenomena and, in many cases, to challenge and extend existing knowledge within the limits of critical bounded assumptions or predictions of behavior. The theoretical framework is the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. The theoretical framework encompasses not just the theory, but the narrative explanation about how the researcher engages in using the theory and its underlying assumptions to investigate the research problem. It is the structure of your paper that summarizes concepts, ideas, and theories derived from prior research studies and which was synthesized in order to form a conceptual basis for your analysis and interpretation of meaning found within your research.

Abend, Gabriel. "The Meaning of Theory." Sociological Theory 26 (June 2008): 173–199; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (December 2018): 44-53; Swanson, Richard A. Theory Building in Applied Disciplines . San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers 2013; Varpio, Lara, Elise Paradis, Sebastian Uijtdehaage, and Meredith Young. "The Distinctions between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework." Academic Medicine 95 (July 2020): 989-994.

Importance of Theory and a Theoretical Framework

Theories can be unfamiliar to the beginning researcher because they are rarely applied in high school social studies curriculum and, as a result, can come across as unfamiliar and imprecise when first introduced as part of a writing assignment. However, in their most simplified form, a theory is simply a set of assumptions or predictions about something you think will happen based on existing evidence and that can be tested to see if those outcomes turn out to be true. Of course, it is slightly more deliberate than that, therefore, summarized from Kivunja (2018, p. 46), here are the essential characteristics of a theory.

- It is logical and coherent

- It has clear definitions of terms or variables, and has boundary conditions [i.e., it is not an open-ended statement]

- It has a domain where it applies

- It has clearly described relationships among variables

- It describes, explains, and makes specific predictions

- It comprises of concepts, themes, principles, and constructs

- It must have been based on empirical data [i.e., it is not a guess]

- It must have made claims that are subject to testing, been tested and verified

- It must be clear and concise

- Its assertions or predictions must be different and better than those in existing theories

- Its predictions must be general enough to be applicable to and understood within multiple contexts

- Its assertions or predictions are relevant, and if applied as predicted, will result in the predicted outcome

- The assertions and predictions are not immutable, but subject to revision and improvement as researchers use the theory to make sense of phenomena

- Its concepts and principles explain what is going on and why

- Its concepts and principles are substantive enough to enable us to predict a future

Given these characteristics, a theory can best be understood as the foundation from which you investigate assumptions or predictions derived from previous studies about the research problem, but in a way that leads to new knowledge and understanding as well as, in some cases, discovering how to improve the relevance of the theory itself or to argue that the theory is outdated and a new theory needs to be formulated based on new evidence.

A theoretical framework consists of concepts and, together with their definitions and reference to relevant scholarly literature, existing theory that is used for your particular study. The theoretical framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of your research paper and that relate to the broader areas of knowledge being considered.

The theoretical framework is most often not something readily found within the literature . You must review course readings and pertinent research studies for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power.

The theoretical framework strengthens the study in the following ways :

- An explicit statement of theoretical assumptions permits the reader to evaluate them critically.

- The theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge. Guided by a relevant theory, you are given a basis for your hypotheses and choice of research methods.

- Articulating the theoretical assumptions of a research study forces you to address questions of why and how. It permits you to intellectually transition from simply describing a phenomenon you have observed to generalizing about various aspects of that phenomenon.

- Having a theory helps you identify the limits to those generalizations. A theoretical framework specifies which key variables influence a phenomenon of interest and highlights the need to examine how those key variables might differ and under what circumstances.

- The theoretical framework adds context around the theory itself based on how scholars had previously tested the theory in relation their overall research design [i.e., purpose of the study, methods of collecting data or information, methods of analysis, the time frame in which information is collected, study setting, and the methodological strategy used to conduct the research].

By virtue of its applicative nature, good theory in the social sciences is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose: to explain the meaning, nature, and challenges associated with a phenomenon, often experienced but unexplained in the world in which we live, so that we may use that knowledge and understanding to act in more informed and effective ways.

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Corvellec, Hervé, ed. What is Theory?: Answers from the Social and Cultural Sciences . Stockholm: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2013; Asher, Herbert B. Theory-Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences . Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1984; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (2018): 44-53; Omodan, Bunmi Isaiah. "A Model for Selecting Theoretical Framework through Epistemology of Research Paradigms." African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 4 (2022): 275-285; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Jarvis, Peter. The Practitioner-Researcher. Developing Theory from Practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Strategies for Developing the Theoretical Framework

I. Developing the Framework

Here are some strategies to develop of an effective theoretical framework:

- Examine your thesis title and research problem . The research problem anchors your entire study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework.

- Brainstorm about what you consider to be the key variables in your research . Answer the question, "What factors contribute to the presumed effect?"

- Review related literature to find how scholars have addressed your research problem. Identify the assumptions from which the author(s) addressed the problem.

- List the constructs and variables that might be relevant to your study. Group these variables into independent and dependent categories.

- Review key social science theories that are introduced to you in your course readings and choose the theory that can best explain the relationships between the key variables in your study [note the Writing Tip on this page].

- Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research.

A theoretical framework is used to limit the scope of the relevant data by focusing on specific variables and defining the specific viewpoint [framework] that the researcher will take in analyzing and interpreting the data to be gathered. It also facilitates the understanding of concepts and variables according to given definitions and builds new knowledge by validating or challenging theoretical assumptions.

II. Purpose

Think of theories as the conceptual basis for understanding, analyzing, and designing ways to investigate relationships within social systems. To that end, the following roles served by a theory can help guide the development of your framework.

- Means by which new research data can be interpreted and coded for future use,

- Response to new problems that have no previously identified solutions strategy,

- Means for identifying and defining research problems,

- Means for prescribing or evaluating solutions to research problems,

- Ways of discerning certain facts among the accumulated knowledge that are important and which facts are not,

- Means of giving old data new interpretations and new meaning,

- Means by which to identify important new issues and prescribe the most critical research questions that need to be answered to maximize understanding of the issue,

- Means of providing members of a professional discipline with a common language and a frame of reference for defining the boundaries of their profession, and

- Means to guide and inform research so that it can, in turn, guide research efforts and improve professional practice.

Adapted from: Torraco, R. J. “Theory-Building Research Methods.” In Swanson R. A. and E. F. Holton III , editors. Human Resource Development Handbook: Linking Research and Practice . (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1997): pp. 114-137; Jacard, James and Jacob Jacoby. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Guilford, 2010; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Sutton, Robert I. and Barry M. Staw. “What Theory is Not.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (September 1995): 371-384.

Structure and Writing Style

The theoretical framework may be rooted in a specific theory , in which case, your work is expected to test the validity of that existing theory in relation to specific events, issues, or phenomena. Many social science research papers fit into this rubric. For example, Peripheral Realism Theory, which categorizes perceived differences among nation-states as those that give orders, those that obey, and those that rebel, could be used as a means for understanding conflicted relationships among countries in Africa. A test of this theory could be the following: Does Peripheral Realism Theory help explain intra-state actions, such as, the disputed split between southern and northern Sudan that led to the creation of two nations?

However, you may not always be asked by your professor to test a specific theory in your paper, but to develop your own framework from which your analysis of the research problem is derived . Based upon the above example, it is perhaps easiest to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as an answer to two basic questions:

- What is the research problem/question? [e.g., "How should the individual and the state relate during periods of conflict?"]

- Why is your approach a feasible solution? [i.e., justify the application of your choice of a particular theory and explain why alternative constructs were rejected. I could choose instead to test Instrumentalist or Circumstantialists models developed among ethnic conflict theorists that rely upon socio-economic-political factors to explain individual-state relations and to apply this theoretical model to periods of war between nations].

The answers to these questions come from a thorough review of the literature and your course readings [summarized and analyzed in the next section of your paper] and the gaps in the research that emerge from the review process. With this in mind, a complete theoretical framework will likely not emerge until after you have completed a thorough review of the literature .

Just as a research problem in your paper requires contextualization and background information, a theory requires a framework for understanding its application to the topic being investigated. When writing and revising this part of your research paper, keep in mind the following:

- Clearly describe the framework, concepts, models, or specific theories that underpin your study . This includes noting who the key theorists are in the field who have conducted research on the problem you are investigating and, when necessary, the historical context that supports the formulation of that theory. This latter element is particularly important if the theory is relatively unknown or it is borrowed from another discipline.

- Position your theoretical framework within a broader context of related frameworks, concepts, models, or theories . As noted in the example above, there will likely be several concepts, theories, or models that can be used to help develop a framework for understanding the research problem. Therefore, note why the theory you've chosen is the appropriate one.

- The present tense is used when writing about theory. Although the past tense can be used to describe the history of a theory or the role of key theorists, the construction of your theoretical framework is happening now.

- You should make your theoretical assumptions as explicit as possible . Later, your discussion of methodology should be linked back to this theoretical framework.

- Don’t just take what the theory says as a given! Reality is never accurately represented in such a simplistic way; if you imply that it can be, you fundamentally distort a reader's ability to understand the findings that emerge. Given this, always note the limitations of the theoretical framework you've chosen [i.e., what parts of the research problem require further investigation because the theory inadequately explains a certain phenomena].

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Conceptual Framework: What Do You Think is Going On? College of Engineering. University of Michigan; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Lynham, Susan A. “The General Method of Theory-Building Research in Applied Disciplines.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 4 (August 2002): 221-241; Tavallaei, Mehdi and Mansor Abu Talib. "A General Perspective on the Role of Theory in Qualitative Research." Journal of International Social Research 3 (Spring 2010); Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Weick, Karl E. “The Work of Theorizing.” In Theorizing in Social Science: The Context of Discovery . Richard Swedberg, editor. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), pp. 177-194.

Writing Tip

Borrowing Theoretical Constructs from Other Disciplines

An increasingly important trend in the social and behavioral sciences is to think about and attempt to understand research problems from an interdisciplinary perspective. One way to do this is to not rely exclusively on the theories developed within your particular discipline, but to think about how an issue might be informed by theories developed in other disciplines. For example, if you are a political science student studying the rhetorical strategies used by female incumbents in state legislature campaigns, theories about the use of language could be derived, not only from political science, but linguistics, communication studies, philosophy, psychology, and, in this particular case, feminist studies. Building theoretical frameworks based on the postulates and hypotheses developed in other disciplinary contexts can be both enlightening and an effective way to be more engaged in the research topic.

CohenMiller, A. S. and P. Elizabeth Pate. "A Model for Developing Interdisciplinary Research Theoretical Frameworks." The Qualitative Researcher 24 (2019): 1211-1226; Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Undertheorize!

Do not leave the theory hanging out there in the introduction never to be mentioned again. Undertheorizing weakens your paper. The theoretical framework you describe should guide your study throughout the paper. Be sure to always connect theory to the review of pertinent literature and to explain in the discussion part of your paper how the theoretical framework you chose supports analysis of the research problem or, if appropriate, how the theoretical framework was found to be inadequate in explaining the phenomenon you were investigating. In that case, don't be afraid to propose your own theory based on your findings.

Yet Another Writing Tip

What's a Theory? What's a Hypothesis?

The terms theory and hypothesis are often used interchangeably in newspapers and popular magazines and in non-academic settings. However, the difference between theory and hypothesis in scholarly research is important, particularly when using an experimental design. A theory is a well-established principle that has been developed to explain some aspect of the natural world. Theories arise from repeated observation and testing and incorporates facts, laws, predictions, and tested assumptions that are widely accepted [e.g., rational choice theory; grounded theory; critical race theory].

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in your study. For example, an experiment designed to look at the relationship between study habits and test anxiety might have a hypothesis that states, "We predict that students with better study habits will suffer less test anxiety." Unless your study is exploratory in nature, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen during the course of your research.

The key distinctions are:

- A theory predicts events in a broad, general context; a hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a specified set of circumstances.

- A theory has been extensively tested and is generally accepted among a set of scholars; a hypothesis is a speculative guess that has yet to be tested.

Cherry, Kendra. Introduction to Research Methods: Theory and Hypothesis. About.com Psychology; Gezae, Michael et al. Welcome Presentation on Hypothesis. Slideshare presentation.

Still Yet Another Writing Tip

Be Prepared to Challenge the Validity of an Existing Theory

Theories are meant to be tested and their underlying assumptions challenged; they are not rigid or intransigent, but are meant to set forth general principles for explaining phenomena or predicting outcomes. Given this, testing theoretical assumptions is an important way that knowledge in any discipline develops and grows. If you're asked to apply an existing theory to a research problem, the analysis will likely include the expectation by your professor that you should offer modifications to the theory based on your research findings.

Indications that theoretical assumptions may need to be modified can include the following:

- Your findings suggest that the theory does not explain or account for current conditions or circumstances or the passage of time,

- The study reveals a finding that is incompatible with what the theory attempts to explain or predict, or

- Your analysis reveals that the theory overly generalizes behaviors or actions without taking into consideration specific factors revealed from your analysis [e.g., factors related to culture, nationality, history, gender, ethnicity, age, geographic location, legal norms or customs , religion, social class, socioeconomic status, etc.].

Philipsen, Kristian. "Theory Building: Using Abductive Search Strategies." In Collaborative Research Design: Working with Business for Meaningful Findings . Per Vagn Freytag and Louise Young, editors. (Singapore: Springer Nature, 2018), pp. 45-71; Shepherd, Dean A. and Roy Suddaby. "Theory Building: A Review and Integration." Journal of Management 43 (2017): 59-86.

- << Previous: The Research Problem/Question

- Next: 5. The Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 12:20 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work.

Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research, showing that your work is grounded in established ideas.

In other words, your theoretical framework justifies and contextualises your later research, and it’s a crucial first step for your research paper , thesis, or dissertation . A well-rounded theoretical framework sets you up for success later on in your research and writing process.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why do you need a theoretical framework, how to write a theoretical framework, structuring your theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, frequently asked questions about theoretical frameworks.

Before you start your own research, it’s crucial to familiarise yourself with the theories and models that other researchers have already developed. Your theoretical framework is your opportunity to present and explain what you’ve learned, situated within your future research topic.

There’s a good chance that many different theories about your topic already exist, especially if the topic is broad. In your theoretical framework, you will evaluate, compare, and select the most relevant ones.

By “framing” your research within a clearly defined field, you make the reader aware of the assumptions that inform your approach, showing the rationale behind your choices for later sections, like methodology and discussion . This part of your dissertation lays the foundations that will support your analysis, helping you interpret your results and make broader generalisations .

- In literature , a scholar using postmodernist literary theory would analyse The Great Gatsby differently than a scholar using Marxist literary theory.

- In psychology , a behaviourist approach to depression would involve different research methods and assumptions than a psychoanalytic approach.

- In economics , wealth inequality would be explained and interpreted differently based on a classical economics approach than based on a Keynesian economics one.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

To create your own theoretical framework, you can follow these three steps:

- Identifying your key concepts

- Evaluating and explaining relevant theories

- Showing how your research fits into existing research

1. Identify your key concepts

The first step is to pick out the key terms from your problem statement and research questions . Concepts often have multiple definitions, so your theoretical framework should also clearly define what you mean by each term.

To investigate this problem, you have identified and plan to focus on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

Research question : How can the satisfaction of company X’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

2. Evaluate and explain relevant theories

By conducting a thorough literature review , you can determine how other researchers have defined these key concepts and drawn connections between them. As you write your theoretical framework, your aim is to compare and critically evaluate the approaches that different authors have taken.

After discussing different models and theories, you can establish the definitions that best fit your research and justify why. You can even combine theories from different fields to build your own unique framework if this better suits your topic.

Make sure to at least briefly mention each of the most important theories related to your key concepts. If there is a well-established theory that you don’t want to apply to your own research, explain why it isn’t suitable for your purposes.

3. Show how your research fits into existing research

Apart from summarising and discussing existing theories, your theoretical framework should show how your project will make use of these ideas and take them a step further.

You might aim to do one or more of the following:

- Test whether a theory holds in a specific, previously unexamined context

- Use an existing theory as a basis for interpreting your results

- Critique or challenge a theory

- Combine different theories in a new or unique way

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation. As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

There are no fixed rules for structuring your theoretical framework, but it’s best to double-check with your department or institution to make sure they don’t have any formatting guidelines. The most important thing is to create a clear, logical structure. There are a few ways to do this:

- Draw on your research questions, structuring each section around a question or key concept

- Organise by theory cluster

- Organise by date

As in all other parts of your research paper , thesis, or dissertation , make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

To get a sense of what this part of your thesis or dissertation might look like, take a look at our full example .

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/the-theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, how to write a results section | tips & examples, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

Theoretical Framework Example for a Thesis or Dissertation

Published on October 14, 2015 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Tegan George.

Your theoretical framework defines the key concepts in your research, suggests relationships between them, and discusses relevant theories based on your literature review .

A strong theoretical framework gives your research direction. It allows you to convincingly interpret, explain, and generalize from your findings and show the relevance of your thesis or dissertation topic in your field.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Sample problem statement and research questions, sample theoretical framework, your theoretical framework, other interesting articles.

Your theoretical framework is based on:

- Your problem statement

- Your research questions

- Your literature review

A new boutique downtown is struggling with the fact that many of their online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases. This is a big issue for the otherwise fast-growing store.Management wants to increase customer loyalty. They believe that improved customer satisfaction will play a major role in achieving their goal of increased return customers.

To investigate this problem, you have zeroed in on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

- Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

- Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

- Research question : How can the satisfaction of the boutique’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

The concepts of “customer loyalty” and “customer satisfaction” are clearly central to this study, along with their relationship to the likelihood that a customer will return. Your theoretical framework should define these concepts and discuss theories about the relationship between these variables.

Some sub-questions could include:

- What is the relationship between customer loyalty and customer satisfaction?

- How satisfied and loyal are the boutique’s online customers currently?

- What factors affect the satisfaction and loyalty of the boutique’s online customers?

As the concepts of “loyalty” and “customer satisfaction” play a major role in the investigation and will later be measured, they are essential concepts to define within your theoretical framework .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Below is a simplified example showing how you can describe and compare theories in your thesis or dissertation . In this example, we focus on the concept of customer satisfaction introduced above.

Customer satisfaction

Thomassen (2003, p. 69) defines customer satisfaction as “the perception of the customer as a result of consciously or unconsciously comparing their experiences with their expectations.” Kotler & Keller (2008, p. 80) build on this definition, stating that customer satisfaction is determined by “the degree to which someone is happy or disappointed with the observed performance of a product in relation to his or her expectations.”

Performance that is below expectations leads to a dissatisfied customer, while performance that satisfies expectations produces satisfied customers (Kotler & Keller, 2003, p. 80).

The definition of Zeithaml and Bitner (2003, p. 86) is slightly different from that of Thomassen. They posit that “satisfaction is the consumer fulfillment response. It is a judgement that a product or service feature, or the product of service itself, provides a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment.” Zeithaml and Bitner’s emphasis is thus on obtaining a certain satisfaction in relation to purchasing.

Thomassen’s definition is the most relevant to the aims of this study, given the emphasis it places on unconscious perception. Although Zeithaml and Bitner, like Thomassen, say that customer satisfaction is a reaction to the experience gained, there is no distinction between conscious and unconscious comparisons in their definition.

The boutique claims in its mission statement that it wants to sell not only a product, but also a feeling. As a result, unconscious comparison will play an important role in the satisfaction of its customers. Thomassen’s definition is therefore more relevant.

Thomassen’s Customer Satisfaction Model

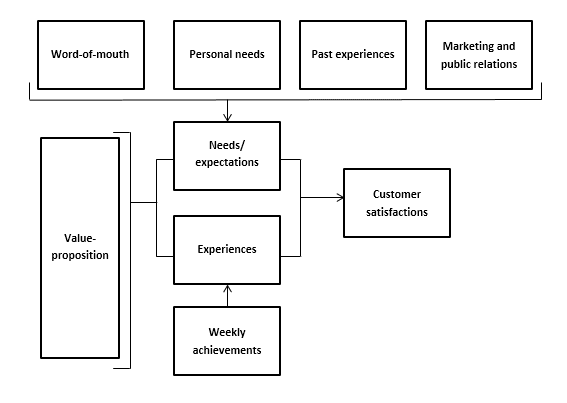

According to Thomassen, both the so-called “value proposition” and other influences have an impact on final customer satisfaction. In his satisfaction model (Fig. 1), Thomassen shows that word-of-mouth, personal needs, past experiences, and marketing and public relations determine customers’ needs and expectations.

These factors are compared to their experiences, with the interplay between expectations and experiences determining a customer’s satisfaction level. Thomassen’s model is important for this study as it allows us to determine both the extent to which the boutique’s customers are satisfied, as well as where improvements can be made.

Figure 1 Customer satisfaction creation

Of course, you could analyze the concepts more thoroughly and compare additional definitions to each other. You could also discuss the theories and ideas of key authors in greater detail and provide several models to illustrate different concepts.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Vinz, S. (2023, July 18). Theoretical Framework Example for a Thesis or Dissertation. Scribbr. Retrieved April 17, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/theoretical-framework-example/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is your plagiarism score.

What Is A Theoretical Framework? A Practical Answer

- Published: 30 November 2015

- Volume 26 , pages 593–597, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Norman G. Lederman 1 &

- Judith S. Lederman 1

210k Accesses

26 Citations

37 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Other than the poor or non-existent validity and/or reliability of data collection measures, the lack of a theoretical framework is the most frequently cited reason for our editorial decision not to publish a manuscript in the Journal of Science Teacher Education . A poor or missing theoretical framework is similarly a critical problem for manuscripts submitted to other journals for which Norman or Judith have either served as Editor or been on the Editorial Board. Often the problem is that an author fails to justify his/her research effort with a theoretical framework. However, there is another level to the problem. Many individuals have a rather narrow conception of what constitutes a theoretical framework or that it is somehow distinct from a conceptual framework. The distinction on lack thereof is a story for another day. The following story may remind you of an experience you or one of your classmates have had.

Doctoral students live in fear of hearing these now famous words from their thesis advisor: “This sounds like a promising study, but what is your theoretical framework?” These words instantly send the harried doctoral student to the library (giving away our ages) in search of a theory to support the proposed research and to satisfy his/her advisor. The search is often unsuccessful because of the student’s misconception of what constitutes a “theoretical framework.” The framework may actually be a theory, but not necessarily. This is especially true for theory driven research (typically quantitative) that is attempting to test the validity of existing theory. However, this narrow definition of a theoretical framework is commonly not aligned with qualitative research paradigms that are attempting to develop theory, for example, grounded theory, or research falling into the categories of description and interpretation research (Peshkin, 1993 ). Additionally, a large proportion of doctoral theses do not fit the narrow definition described. The argument here is not that various research paradigms have no overarching philosophies or theories about knowing. Clearly quantitative research paradigms are couched in a realist perspective and qualitative research paradigms are couched in an idealist perspective (Bogdan & Biklen, 1982 ). The discussion here is focused on theoretical frameworks at a much more specific and localized perspective with respect to the justification and conceptualization of a single research investigation. So, what is a theoretical framework?

It is, perhaps, easier to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as the answer to two basic questions:

What is the problem or question?

Why is your approach to solving the problem or answering the question feasible?

Indeed, the answers to these questions are the substance and culmination of Chapters I and II of the proposal and completed dissertation, or the initial sections preceding the Methods section of a research article. The answers to these questions can come from only one source, a thorough review of the literature (i.e., a review that includes both the theoretical and empirical literature as well as apparent gaps in the literature). Perhaps, a hypothetical situation can best illustrate the development and role of the theoretical framework in the formalization of a dissertation topic or research investigation. Let us continue with the doctoral student example, keeping in mind that a parallel situation also presents itself to any researcher planning research that he/she intends to publish.

As an interested reader of educational literature, a doctoral student becomes intrigued by the importance of questioning in the secondary classroom. The student immediately begins a manual and computer search of the literature on questioning in the classroom. The student notices that the research findings on the effectiveness of questioning strategies are rather equivocal. In particular, much of the research focuses on the cognitive levels of the questions asked by the teacher and how these questions influence student achievement. It appears that the research findings exhibit no clear pattern. That is, in some studies, frequent questioning at higher cognitive levels has led to more achievement than frequent questioning at the lower cognitive levels. However, an equal number of investigations have shown no differences between the achievement of students who are exposed to questions at distinctly different cognitive levels, but rather the simple frequency of questions.

The doctoral student becomes intrigued by these equivocal findings and begins to speculate about some possible explanations. In a blinding flash of insight, the student remembers hearing somewhere that an eccentric Frenchman named Piaget said something about students being categorized into levels of cognitive development. Could it be that a student’s cognitive level has something to do with how much and what he/she learns? The student heads back to the library and methodically searches through the literature on cognitive development and its relationship to achievement.

At this point, the doctoral student has become quite familiar with two distinct lines of educational research. The research on the effectiveness of questioning has established that there is a problem. That is, does the cognitive level of questioning have any effect on student achievement? In effect, this answers the first question identified previously with respect to identification of a theoretical framework. The research on the cognitive development of students has provided an intriguing perspective. That is, could it be possible that students of different cognitive levels are affected differently by questions at different cognitive levels? If so, an answer to the problem concerning the effectiveness questioning may be at hand. This latter question, in effect, has addressed the second question previously posed about the identification of a theoretical framework. At this point, the student has narrowed his/her interests as a result of reviewing the literature. Note that the doctoral student is now ready to write down a specific research question and that this is only possible after having conducted a thorough review of the literature.

The student writes down the following research hypotheses:

Both high and low cognitive level pupils will benefit from both high and low cognitive levels of questions as opposed to no questions at all.

Pupils categorized at high cognitive levels will benefit more from high cognitive level questions than from low level questions.

Pupils categorized at lower cognitive levels will benefit more from low cognitive level questions than from high level questions.

These research questions still need to be transformed into testable statistical hypotheses, but they are ready to be presented to the dissertation advisor. The advisor looks at the questions and says: “This looks like a promising study, but what is your theoretical framework?” There is no need, however for a sprint to the library. The doctoral student has a theoretical framework. The literature on questioning has established that there is a problem and the literature on cognitive development has provided the rationale for performing the specific investigation that is being proposed. ALL IS WELL!

If some of the initial research completed by Norman concerning what classroom variables contributed to students’ understandings of nature of science (Lederman, 1986a , 1986b ; Lederman & Druger, 1985 ) had to align with the overly restricted definition of a theoretical framework, which necessitates the presence of theory, it never would have been published. In these initial studies, various classroom variables were identified that were related to students’ improved understandings of nature of science. The studies were descriptive and correlational and were not driven by any theory about how students learn nature of science. Indeed, the design of the studies was derived from the fact that there were no existing theories, general or specific, to explain how students might learn nature of science more effectively. Similarly, the seminal study of effective teaching, the Beginning Teacher Evaluation Study (Tikunoff, Berliner, & Rist, 1975 ), was an ethnographic study that was not guided by the findings of previous research on effective teaching. Rather, their inductive study simply compared 40 teachers “known” to be effective and ineffective of mathematics and reading to derive differences in classroom practice. Their study had no theoretical framework if one were to use the restrictive conception that a theory needed to provide a guiding framework for the investigation. There are plenty of other examples that have guided lines of research that could be provided, but there is no need to beat a dead horse by detailing more examples. The simple, but important, point is that research following qualitative research paradigms or traditions (Jacob, 1987 ; Smith, 1987 ) are particularly vulnerable to how ‘theoretical framework’ is defined. Indeed, it could be argued that the necessity of a theory is a remnant from the times in which qualitative research was not as well accepted as it is today. In general, any research design that is inductive in nature and attempts to develop theory would be at a loss. We certainly would not want to eliminate multiple traditions of research from the Journal of Science Teacher Education .

Harry Wolcott’s discussion about validity in qualitative research (Wolcott, 1990 ) is quite explicit about the lack of theory or necessity of theory in driving qualitative ethnography. Interestingly, he even rejects the idea of validity as being a necessary criterion in qualitative research. Additionally, Bogdan and Biklen ( 1982 ) emphasize the importance of qualitative researchers “bracketing” (i.e., masking or trying to forget) their a priori theories so that it does not influence the collection of data or any meanings assigned to data during an investigation. Similar discussions about how qualitative research differs from quantitative research with respect to the necessity of theory guiding the research have been advanced by many others (e.g., Becker, 1970 ; Bogdan & Biklen, 1982 ; Erickson, 1986 ; Krathwohl, 2009 ; Rist, 1977 ; among others). Perhaps, Peshkin ( 1993 , p. 23) put it best when he expressed his concern that “Research that is not theory driven, hypothesis testing, or generalization producing may be dismissed as deficient or worse.” Again, the key point is that qualitative research is as valuable and can contribute as much to our knowledge of teaching and learning as quantitative research.

There is little doubt that qualitative researchers often invoke theory when analyzing the data they have collected or try to place their findings within the context of the existing literature. And, as stated at the beginning of this editorial, different research paradigms have large overarching theories about how one comes to know about the world. However, this is not the same thing has using a theory as a framework for the design of an investigation from the stating of research questions to developing a design to answer the research questions.

It is quite possible that you may be thinking that this editorial about the meaning of a theoretical framework is too theoretical. Trust us in believing that there is a very practical reason for us addressing this issue. At the beginning of the editorial we talked about the lack of a theoretical framework being the second most common reason for manuscripts being rejected for publication in the Journal of Science Teacher Education . Additionally, we mentioned that this is a common reason for manuscripts being rejected by other prominent journals in science education, and education in general. Consequently, it is of critical importance that we, as a community, are clear about the meaning of a theoretical framework and its use. It is especially important that our authors, reviewers, associate editors, and we as Editors of the journal are clear on this matter. Let us not fail to mention that most of us are advising Ph.D. students in the conceptualization of their dissertations. This issue is not new. In 1992, the editorial board of the Journal of Research in Science Teaching was considering the claim, by some, that qualitative research was not being evaluated fairly for publication relative to quantitative research. In their analysis of the relative success of publication for quantitative and qualitative research, Wandersee and Demastes ( 1992 , p. 1005) noted that reviewers often noted, “The manuscript had a weak theoretical basis” when reviewing qualitative research.

Theoretical frameworks are critically important to all of our work, quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. All research articles should have a valid theoretical framework to justify the importance and significance of the work. However, we should not live in fear, as the doctoral student, of not having a theoretical framework, when we actually have such, because an Editor, reviewer, or Major Professor is using any unduly restrictive and outdated meaning for what constitutes a theoretical framework.

Becker, H. (1970). Sociological work: Methods and substance . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Google Scholar

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (1982). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods . Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 119–161). New York: Macmillan.

Jacob, E. (1987). Qualitative research traditions: A review. Review of Educational Research, 57 , 1–50.

Article Google Scholar

Krathwohl, D. R. (2009). Methods of educational and social science research . Logrove, IL: Waveland Press.

Lederman, N. G. (1986a). Relating teaching behavior and classroom climate to changes in students’ conceptions of the nature of science. Science Education, 70 (1), 3–19.

Lederman, N. G. (1986b). Students’ and teachers’ understanding of the nature of science: A reassessment. School Science and Mathematics, 86 , 91–99.

Lederman, N. G., & Druger, M. (1985). Classroom factors related to changes in students’ conceptions of the nature of science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 22 , 649–662.

Peshkin, A. (1993). The goodness of qualitative research. Educational Researcher, 22 (2), 24–30.

Rist, R. (1977). On the relations among educational research paradigms: From disdain to détente. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 8 , 42–49.

Smith, M. L. (1987). Publishing qualitative research. American Educational Research Journal, 24 (2), 173–183.

Tikunoff, W. J., Berliner, D. C., & Rist, R. C. (1975). Special study A: An enthnographic study of forty classrooms of the beginning teacher evaluation study known sample . Sacramento, CA: California Commission for Teacher Preparation and Licensing.

Wandersee, J. H., & Demastes, S. (1992). An analysis of the relative success of qualitative and quantitative manuscripts submitted to the Journal of Research in Science Teaching . Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 29 , 1005–1010.

Wolcott, H. F. (1990). On seeking, and rejecting, validity in qualitative research. In E. W. Eisner & A. Peshkin (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry in education (pp. 121–152). New York: Teachers College Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Chicago, IL, USA

Norman G. Lederman & Judith S. Lederman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Norman G. Lederman .

About this article

Lederman, N.G., Lederman, J.S. What Is A Theoretical Framework? A Practical Answer. J Sci Teacher Educ 26 , 593–597 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-015-9443-2

Download citation

Published : 30 November 2015

Issue Date : November 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-015-9443-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Mary DePew Resource Center for Research Writing: Theoretical Frameworks

- Identifying Scholarly Resources

- Primary Vs. Secondary

- Peer-Reviewed

- Practitioner Vs. Scholarly

- College of Business: Essential Readings

- College of Education: Curriculum & Instruction

- College of Education: Leadership & Administration Essential Readings

- College of Education: Teaching & Learning Essential Readings

- College of Health, Science, and Technology: Essential Readings

- College of Theology, Arts, and Humanities: Division of Research Essential Readings

- Lutheran Education Journal This link opens in a new window

- Concordia University Chicago: Pillars Yearbooks This link opens in a new window

- Martin Luther & the Lutheran Church This link opens in a new window

Theoretical Frameworks

- Journals by Subject

- Online Resources

- APA 7th Ed.

- Expository Paragraph Writing

- Sentence Composition

- Online Writing Labs

- Comprehensive Exam Writing

- Comprehensive Exam Rubric Example

- Comprehensive Exam College of Education, Dept. of Curriculum & Instruction: Rubric Example Parts 1 & 2

- Comprehensive Exam College of Education, Dept. of Ed Leadership: Rubric Example Part 1 & 2

- Comprehensive Exam FAQs This link opens in a new window

- Qualitative Research Focused Journals

- Technology for Data Collection and Analysis

- Research Tools

- Example Dissertations by Epis//Method. Claim

- Dissertation FAQs & Models This link opens in a new window

- Dissertation Ebooks

- Doctoral Defense

- CUC Doc Student Support Groups

- Faculty Publications

- CUC Writing Center This link opens in a new window

- Klinck Library Resources

- Accessibility & Accommodations Services This link opens in a new window

- CougarNet This link opens in a new window

- What are they?

- Strategies for Developing your Framework

- Ed. Leadership Examples

A theoretical framework consists of concepts and, together with their definitions and reference to relevant scholarly literature, existing theory that is used for your particular study. Theoretical frameworks provide a perspective through which to examine a topic, especially when constructing your dissertation. There are many different lenses, which may be used to define specific concepts and explain phenomena. Different lenses can be:

- psychological theories

- social theories

- organizational theories

- economic theories

Sometimes frameworks may come from an area outside of your immediate academic discipline. Using a theoretical framework for your dissertation will help you to better analyze past events by providing a particular set of questions to ask and a perspective to use when examining your topic.

Traditionally, Ph.D. and Applied Degree research must include relevant theoretical framework(s) to frame, or inform, every aspect of the dissertation. Dissertations should make an original contribution to the field by adding support for the theory or demonstrating ways in which the theory may not be as explanatory as originally thought.

It can be difficult to find scholarly work that takes a particular theoretical approach because articles, books, and book chapters are typically described according to the topics they tackle rather than the methods they use to tackle them.

Unfortunately, there is no single database or search technique for locating theoretical information. However, the suggestions below provide techniques for locating possible theoretical frameworks and theorists in the CUC library databases. In addition to your Library research, you should discuss possible theories your Dissertation Chair to ensure they align with your study. You will likely find and discard several potential theoretical frameworks before one is finally chosen.

I. Developing the Framework

Here are some strategies to develop of an effective theoretical framework:

- Examine your thesis title and research problem . The research problem anchors your entire study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework.

- Brainstorm about what you consider to be the key variables in your research . Answer the question, "What factors contribute to the presumed effect?"

- Review related literature to find how scholars have addressed your research question.

- List the constructs and variables that might be relevant to your study. Group these variables into independent and dependent categories.

- Review key social science theories that are introduced to you in your course readings and choose the theory that can best explain the relationships between the key variables in your study [note the Writing Tip on this page].

- Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research.

A theoretical framework is used to limit the scope of the relevant data by focusing on specific variables and defining the specific viewpoint [framework] that the researcher will take in analyzing and interpreting the data to be gathered. It also facilitates the understanding of concepts and variables according to given definitions and builds new knowledge by validating or challenging theoretical assumptions.

II. Purpose

Think of theories as the conceptual basis for understanding, analyzing, and designing ways to investigate relationships within social systems. To that end, the following roles served by a theory can help guide the development of your framework.

- Means by which new research data can be interpreted and coded for future use,

- Response to new problems that have no previously identified solutions strategy,

- Means for identifying and defining research problems,

- Means for prescribing or evaluating solutions to research problems,

- Ways of discerning certain facts among the accumulated knowledge that are important and which facts are not,

- Means of giving old data new interpretations and new meaning,

- Means by which to identify important new issues and prescribe the most critical research questions that need to be answered to maximize understanding of the issue,

- Means of providing members of a professional discipline with a common language and a frame of reference for defining the boundaries of their profession, and

- Means to guide and inform research so that it can, in turn, guide research efforts and improve professional practice.

Adapted from: Torraco, R. J. “Theory-Building Research Methods.” In Swanson R. A. and E. F. Holton III , editors. Human Resource Development Handbook: Linking Research and Practice . (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1997): pp. 114-137; Jacard, James and Jacob Jacoby. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Guilford, 2010; Sutton, Robert I. and Barry M. Staw. “What Theory is Not.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (September 1995): 371-384.

No framework is necessarily more effective than another. Frameworks serve to provide a conceptual overview, separate from methodologies or implementation. Though there are thousands of theoretical frameworks leveraged in teaching, some of the more popular frameworks are:

- Andragogy/Adult Learning Theory – Theorists like Knowles (1980) believed adults are problem-oriented participants that want to incorporate experience and self-direction into subjects or projects that are relevant to their lives. Andragogic education tends to incorporate methods like constructivism and connectivism, leveraging task-oriented processes and projects, also stressing application.

- Behaviorism – Theorists like Skinner (1953) often focused on observable behavior, believing learning was supported through drill & practice and related reinforcement. Behaviorist instruction tends to be directive, incorporating lectures and practice problems, often leveraging objective assessments including multiple choice questions or other rote approaches.

- Cognitivism – Theorists like Gagné (Gagne, Wager, Golas, & Keller, 2004) focused more on thought processes and structures. For instance, Gagné developed nine events of instruction to describe optimal conditions for learning. Cognitivist instruction often incorporates lecture along with methods like visual tools or organizers to promote retention. It may leverage objective assessments with multiple choice, though also including response or essay activities for learners to demonstrate thought processes.

- Connectivism – Theorists like Siemens & Downes (2009) saw learners as part of many nodes or connections, driving their personal learning by leveraging the knowledge of that network, and contributing to the knowledge infrastructure. Connectivist instruction tends to be self-directed, including a variety of information sources/references and is often used in online education. It could also be considered a constructivist approach.

- Constructivism – Theorists like Piaget (1950) & Brunner (1961) proposed individuals construct knowledge from within, contributing to the process by incorporating personal experience. Constructivist instruction tends to be social and exploratory, sometimes without clearly defined outcomes, often leveraging critical thinking activities, peer review, and/or collaborative projects.

- Objectivism – Theorists or writers like Rand (1943) believed knowledge exists outside the individual as opposed to constructivist perspectives valuing knowledge from within. Objectivist frameworks can describe both behaviorist and cognitivist perspectives. Objectivist instruction tends to be directive and linear, valuing inductive logic, and often leverages objective assessments.

Credit to Central Michigan

- National University: Theoretical Frameworks Sheet

- Grant, C., & Osanloo, A. (2014). Understanding, Selecting, and Integrating a Theoretical Framework in Dissertation Research: Creating the Blueprint for Your “House.” Administrative Issues Journal: Education, Practice & Research, 4(2), 12–26. https://doi.o

- Kumar, S., Dawson, K., Pollard, R., & Jeter, G. (2022). Analyzing Theories, Conceptual Frameworks, and Research Methods in EdD Dissertations. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 66(4), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-022-0

- Tegtmeyer, J. (2022). Building a Dissertation Conceptual and Theoretical Framework: A Recent Doctoral Graduate Narrates behind the Curtain Development. Penn GSE Perspectives on Urban Education, 20(1).

- << Previous: Martin Luther & the Lutheran Church

- Next: Lit. Review Resources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 3:39 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cuchicago.edu/research_center

Klinck Memorial Library

Concordia University Chicago 7400 Augusta Street River Forest, Illinois 60305 (708) 209-3050 [email protected] Campus Maps and Directions

- Staff Directory

- Getting Started

- Databases A-Z

- Library Catalog

- Interlibrary Loan

Popular Links

- Research Guides

- Research Help

- Request Class Instruction

© 2021 Copyright: Concordia University Chicago, Klinck Memorial Library

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 22, Issue 2

- Integration of a theoretical framework into your research study

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Roberta Heale 1 ,

- Helen Noble 2

- 1 Laurentian University , School of Nursing , Sudbury , Ontario , Canada

- 2 Queens University Belfast , School of Nursing and Midwifery , Belfast , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Roberta Heale, School of Nursing, Laurentian University, Ramsey Lake Road, Sudbury, P3E2C6, Canada; rheale{at}laurentian.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103077

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Often the most difficult part of a research study is preparing the proposal based around a theoretical or philosophical framework. Graduate students ‘…express confusion, a lack of knowledge, and frustration with the challenge of choosing a theoretical framework and understanding how to apply it’. 1 However, the importance in understanding and applying a theoretical framework in research cannot be overestimated.

The choice of a theoretical framework for a research study is often a reflection of the researcher’s ontological (nature of being) and epistemological (theory of knowledge) perspective. We will not delve into these concepts, or personal philosophy in this article. Rather we will focus on how a theoretical framework can be integrated into research.

The theoretical framework is a blueprint for your research project 1 and serves several purposes. It informs the problem you have identified, the purpose and significance of your research demonstrating how your research fits with what is already known (relationship to existing theory and research). This provides a basis for your research questions, the literature review and the methodology and analysis that you choose. 1 Evidence of your chosen theoretical framework should be visible in every aspect of your research and should demonstrate the contribution of this research to knowledge. 2

What is a theory?

A theory is an explanation of a concept or an abstract idea of a phenomenon. An example of a theory is Bandura’s middle range theory of self-efficacy, 3 or the level of confidence one has in achieving a goal. Self-efficacy determines the coping behaviours that a person will exhibit when facing obstacles. Those who have high self-efficacy are likely to apply adequate effort leading to successful outcomes, while those with low self-efficacy are more likely to give up earlier and ultimately fail. Any research that is exploring concepts related to self-efficacy or the ability to manage difficult life situations might apply Bandura’s theoretical framework to their study.

Using a theoretical framework in a research study

Example 1: the big five theoretical framework.

The first example includes research which integrates the ‘Big Five’, a theoretical framework that includes concepts related to teamwork. These include team leadership, mutual performance monitoring, backup behaviour, adaptability and team orientation. 4 In order to conduct research incorporating a theoretical framework, the concepts need to be defined according to a frame of reference. This provides a means to understand the theoretical framework as it relates to a specific context and provides a mechanism for measurement of the concepts.

In this example, the concepts of the Big Five were given a conceptual definition, that provided a broad meaning and then an operational definition, which was more concrete. 4 From here, a survey was developed that reflected the operational definitions related to teamwork in nursing: the Nursing Teamwork Survey (NTS). 5 In this case, the concepts used in the theoretical framework, the Big Five, were the used to develop a survey specific to teamwork in nursing.

The NTS was used in research of nurses at one hospital in northeastern Ontario. Survey questions were grouped into subscales for analysis, that reflected the concepts of the Big Five. 6 For example, one finding of this study was that the nurses from the surgical unit rated the items in the subscale of ’team leadership' (one of the concepts in the Big Five) significantly lower than in the other units. The researchers looked back to the definition of this concept in the Big Five in their interpretation of the findings. Since the definition included a person(s) who has the leadership skills to facilitate teamwork among the nurses on the unit, the conclusion in this study was that the surgical unit lacked a mentor, or facilitator for teamwork. In this way, the theory of teamwork was presented through a set of concepts in a theoretical framework. The Theoretical Framework (TF)was the foundation for development of a survey related to a specific context, used to measure each of the concepts within the TF. Then, the analysis and results circled back to the concepts within the TF and provided a guide for the discussion and conclusions arising from the research.

Example 2: the Health Decisions Model

In another study which explored adherence to intravenous chemotherapy in African-American and Caucasian Women with early stage breast cancer, an adapted version of the Health Decisions Model (HDM) was used as the theoretical basis for the study. 7 The HDM, a revised version of the Health Belief Model, incorporates some aspects of the Health Belief Model and factors relating to patient preferences. 8 The HDM consists of six interrelated constituents that might predict how well a person adheres to a health decision. These include sociodemographic, social interaction, experience, knowledge, general and specific health beliefs and patient preferences, and are clearly defined. The HDM model was used to explore factors which might influence adherence to chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Sociodemographic, social interaction, knowledge, personal experience and specific health beliefs were used as predictors of adherence to chemotherapy.

The findings were reported using the theoretical framework to discuss results. The study found that delay to treatment, health insurance, depression and symptom severity were predictors to starting chemotherapy which could potentially be adapted with clinical interventions. The findings from the study contribute to the existing body of literature related to cancer nursing.

Example 3: the nursing role effectiveness model

In this final example, research was conducted to determine the nursing processes that were associated with unexpected intensive care unit admissions. 9 The framework was the Nursing Role Effectiveness Model. In this theoretical framework, the concepts within Donabedian’s Quality Framework of Structure, Process and Outcome were each defined according to nursing practice. 10 11 Processes defined in the Nursing Role Effectiveness Model were used to identify the nursing process variables that were measured in the study.

A theoretical framework should be logically presented and represent the concepts, variables and relationships related to your research study, in order to clearly identify what will be examined, described or measured. It involves reading the literature and identifying a research question(s) while clearly defining and identifying the existing relationship between concepts and theories (related to your research questions[s] in the literature). You must then identify what you will examine or explore in relation to the concepts of the theoretical framework. Once you present your findings using the theoretical framework you will be able to articulate how your study relates to and may potentially advance your chosen theory and add to knowledge.

- Kalisch BJ ,

- Parent M , et al

- Strickland OL ,

- Dalton JA , et al

- Eraker SA ,

- Kirscht JP ,

- Lightfoot N , et al

- Harrison MB ,

- Laschinger H , et al

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Patient and public involvement Not required.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

info This is a space for the teal alert bar.

notifications This is a space for the yellow alert bar.

Research Process

- Brainstorming

- Explore Google This link opens in a new window

- Explore Web Resources

- Explore Background Information

- Explore Books

- Explore Scholarly Articles

- Narrowing a Topic

- Primary and Secondary Resources

- Academic, Popular & Trade Publications

- Scholarly and Peer-Reviewed Journals

- Grey Literature

- Clinical Trials

- Evidence Based Treatment

- Scholarly Research

- Database Research Log

- Search Limits

- Keyword Searching

- Boolean Operators

- Phrase Searching

- Truncation & Wildcard Symbols

- Proximity Searching

- Field Codes

- Subject Terms and Database Thesauri

- Reading a Scientific Article

- Website Evaluation

- Article Keywords and Subject Terms

- Cited References

- Citing Articles

- Related Results

- Search Within Publication

- Database Alerts & RSS Feeds

- Personal Database Accounts

- Persistent URLs

- Literature Gap and Future Research

- Web of Knowledge

- Annual Reviews

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- Finding Seminal Works

- Exhausting the Literature

- Finding Dissertations

- Researching Theoretical Frameworks

- Research Methodology & Design

- Tests and Measurements

- Organizing Research & Citations This link opens in a new window

- Scholarly Publication

- Learn the Library This link opens in a new window

Learn Frameworks via Email

Over the course of 7 days, you will receive bite-sized lessons in your email about researching theoretical and conceptual frameworks.

- Click on the link below.

- Complete the very short registration form.

- Check your email!

- Theoretical & Conceptual Frameworks - email series

Additional Guidance

- Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Theoretical Framework University of Southern California

- The Research Planning Process: Theoretical Framework (video)

- Theoretical Framework (video)

- Understanding, selecting, and integrating a Theoretical framework in dissertation research: Creating the blueprint for your “house” Grant, C., & Osanloo, A. (2014). Understanding, Selecting, and Integrating a Theoretical Framework in Dissertation Research: Creating the Blueprint for Your "House". Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, And Research, 4(2), 12-26.

- What is a Theoretical Framework? Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons.

NU Dissertation Center

If you are looking for a document in the Dissertation Center or Applied Doctoral Center and can't find it please contact your Chair or The Center for Teaching and Learning at [email protected]

- NCU Dissertation Center Find valuable resources and support materials to help you through your doctoral journey.

- Applied Doctoral Center Collection of resources to support students in completing their project/dissertation-in-practice as part of the Applied Doctoral Experience (ADE).

Theoretical Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks provide a particular perspective, or lens, through which to examine a topic. There are many different lenses, such as psychological theories, social theories, organizational theories and economic theories, which may be used to define concepts and explain phenomena. Sometimes these frameworks may come from an area outside of your immediate academic discipline. Using a theoretical framework for your dissertation can help you to better analyze past events by providing a particular set of questions to ask, and a particular perspective to use when examining your topic.