- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

The Search Warrant Requirement in Criminal Investigations & Legal Exceptions

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects people’s right “to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.” Police must obtain a search warrant from a judge, although courts have identified exceptions to this rule, such as emergency situations and items plainly visible to police officers. A defendant may ask a court to suppress evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment, which prevents the state from using it in a criminal trial .

Search Warrant Requirements

A judge or magistrate will issue a search warrant only if an affidavit establishes probable cause, and the search warrant is sufficiently limited in scope.

The Fourth Amendment itself identifies the criteria for obtaining a lawful search warrant. A police officer, or other official seeking a warrant, must establish probable cause to the satisfaction of a judge, must make an “[o]ath or affirmation” as to the truth of the matters supporting probable cause, and must “particularly describ[e] the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” A search warrant is invalid if it covers too broad an area or does not identify specific items or persons.

Establishing Probable Cause

The Supreme Court has defined “probable cause” as an officer’s reasonable belief, based on circumstances known to that officer, that a crime has occurred or is about to occur. See Carroll v. United States , 267 U.S. 132, 149 (1925). An officer may establish probable cause with witness statements and other evidence, including hearsay evidence that would not be admissible at trial. An officer’s suspicion or belief, by itself, is not sufficient to establish probable cause. Aguilar v. Texas , 378 U.S. 108, 114-15 (1964).

Exclusionary Rule

The “ exclusionary rule ” requires courts to suppress evidence obtained through an unlawful search or seizure. See Mapp v. Ohio , 367 U.S. 643 (1961). Any evidence derived from illegally obtained evidence must also be suppressed. This type of evidence is known as “fruit of the poisonous tree.” Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States , 251 U.S. 385 (1920; Nardone v. United States , 308 U.S. 338, 341 (1939.

Electronic Searches and Seizures

Privacy interests generally extend to electronics and digital information.

Computers and the internet present new challenges, since digital evidence might be stored on devices in a suspect’s possession or on the various internet servers known as the “cloud.” The Supreme Court has ruled that a warrant is required to search the contents of computers, cell phones, and other devices. Cloud storage remains a subject of contention, with different courts reaching different conclusions.

Exceptions to Warrant Requirement

Exigent Circumstances: Courts have allowed warrantless searches in situations where it would be impractical or dangerous to delay a search in order to obtain a warrant. This might include an imminent threat to an officer’s safety, or a reasonable belief that a suspect will dispose of or destroy evidence while police are waiting for a warrant.

Consent to Search: A police officer does not need a warrant to conduct a search if a person with legal authority over the items or premises consents to a search. Another person who also has legal authority over the premises may overrule consent to a search, but the Supreme Court held in Fernandez v. California , 571 U.S. ___ (2014), that the person must be physically present to prevent the search.

Search Incident to Lawful Arrest: Police officers may conduct a limited search of a person when they have placed the person under arrest. The search must be limited to the area of the person’s immediate control and be for the purpose of checking for weapons and evidence. Chimel v. California , 395 U.S. 752 (1969). Police must obtain a warrant, however, to search a person’s cell phone after an arrest. Riley v. California , 571 U.S. ___ (2014).

Automobile Exception: Related to the “lawful arrest” exception, this allows police to search a vehicle without a warrant during the lawful arrest of the driver, but only if they reasonably believe that (1) the person under arrest might still be able to access the vehicle’s passenger compartment, or (2) the vehicle contains evidence relevant to the offense for which they are arresting the person. Arizona v. Gant , 556 U.S. 332 (2009).

“Plain View” and “Open Fields” Exceptions: An officer may seize property that is visible from a location where the officer is lawfully present, provided that the officer has probable cause to believe the property is contraband. Coolidge v. New Hampshire , 403 U.S. 443 (1971). This might include items that are visible in the front seat of a vehicle during a lawful traffic stop. “Open fields,” defined as open areas of a person’s property that are not directly adjacent to his or her residence, are not protected by the Fourth Amendment and may be searched without a warrant. Hester v. United States , 265 U.S. 57 (1924); Oliver v. United States , 466 U.S. 170 (1984).

Terry Stops: The Supreme Court held in Terry v. Ohio , 392 U.S. 1 (1968), that police may “stop and frisk” a person based on reasonable suspicion that the person has been, is, or will soon be involved in criminal activity. “Reasonable suspicion” is a lower standard than “probable cause.” Evidence discovered in the course of what is now known as a Terry stop is admissible, even if police did not have a warrant.

Border Searches: Officials at the United States border, as well as airports and seaports that handle international travel, have broad discretion to conduct searches of individuals, their personal effects, and their vehicles. See United States v. Montoya de Hernandez , 473 U.S. 531 (1985); United States v. Flores-Montano , 541 U.S. 149 (2004).

Last reviewed October 2023

Criminal Law Center Contents

- Criminal Law Center

- Aggravating and Mitigating Factors in Criminal Sentencing Law

- Bail, Bonds, and Relevant Legal Concerns

- Restitution for Victims in Criminal Law

- Plea Bargains in Criminal Law Cases

- Receiving Immunity for Testimony in a Criminal Law Case

- Legal Classification of Criminal Offenses

- Common Criminal Defenses

- Admissibility of Evidence in Criminal Law Cases

- Criminal Appeals

- Motions for a New Trial in Criminal Law Cases

- Competency to Stand Trial in Criminal Law Cases

- Continuances in Criminal Law Cases

- Judgments of Acquittal in Criminal Trials

- Joint Trials for Criminal Defendants & Legal Considerations

- Immigration Removal Proceedings & Criminal Law Concerns

- Miranda Rights for Criminal Suspects Under the Law

- Police Stops on the Street & Your Legal Rights

- Video or Audio Recording of Police Officers & Your Legal Rights

- Arrests and Arrest Warrants

- Constitutional Rights in Criminal Law Proceedings

- The Right to a Speedy Trial in a Criminal Law Case

- The Right to a Public Trial in a Criminal Law Case

- Double Jeopardy & Legal Protections for Criminal Defendants

- Discovery in Criminal Law Cases

- Hearsay Evidence in Criminal Law

- Stages of a Criminal Case

- Stages of a Criminal Trial

- The Search Warrant Requirement in Criminal Investigations & Legal Exceptions

- Limits on Searches and Seizures in Criminal Investigations by Law Enforcement

- Qualified Immunity

- Criminal Statutes of Limitations: 50-State Survey

- Types of Criminal Offenses

- Alcohol Crimes Under the Law

- Parole and Probation Law

- Expungement and Sealing of Criminal Records

- Offenses Included in Other Crimes Under the Law

- The Mental State Requirement in Criminal Law Cases

- Derivative Responsibility in Criminal Law Cases

- Working with a Criminal Lawyer

- Criminal Law FAQs

- Domestic Violence Restraining Orders Laws and Forms: 50-State Survey

- 50-State Survey on Abortion Laws

- Gun Laws: 50-State Survey

- Death Penalty Laws: 50-State Survey

- Criminal Law Topics

- Find a Criminal Law Lawyer

Related Areas

- DUI & DWI Law Center

- Traffic Tickets Legal Center

- Immigration Law Center

- Tax Law Center

- Military Law Center

- Personal Injury Law Center

- Animal and Dog Law Center

- Communications and Internet Law Center

- Aviation Law Center

- Cannabis Law Center

- Constitutional Law Center

- Related Areas

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

- search warrant

Primary tabs

A search warrant is a warrant signed by a judge or magistrate authorizing a law enforcement officer to conduct a search on a certain person, a specified place, or an automobile for criminal evidence .

A search warrant usually is the prerequisite of a search, which is designed to protect individuals’ reasonable expectation of privacy against unreasonable governmental physical trespass or other intrusion. The origin of this right is from the 4th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to protect people from unlawful government searches and seizures .

The Amendment reads: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrant shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Search warrant requirements

Probable cause : The officer should give reasonable information to support the possibility that the evidence of illegality will be found. Such information may come from the officer’ personal observations or that of an informant. If the warrant lacks accurate information as to what will be searched, the search is unlawful. Se e Groh v. Ramirez, 540 U.S. 551 (2004) .

Particularity: The warrant should describe the place to be searched with particularity. See United States v. Grubbs, 547 U.S. 90 (2006) .

Signed by a “neutral and detached” magistrate or judge. See Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443 (1971) .

Execution of Warrants

Object: The warrant should be executed by government officers (i.e., police officers or government officials like firepersons) to individuals. Private citizens cannot execute it.

Timing: If an unreasonable delay occurs, causing the warrant not timely executed, the grounds that probable cause may disappear.

The warrant usually does not execute at night. Under federal law, it should occur between 6:00 a.m. and 10:00 p.m. except in some special circumstances. See §41 Fed. R. Civ. P .

Knock-and-announce rule: When searching a certain place, an officer must knock and announce authority and purpose before entering, and should wait for a reasonable time or be refused admittance before using force to enter.

Knock-and-announce rule “forms a part of the Fourth Amendment reasonableness inquiry.” See Wilson v. Arkansas, 514 U.S. 927 (1995) .

Waiting time could just be several seconds or not required, if the officer has reasonable fear or suspicion that evidence will be destroyed, or the investigation will get inhibited. See Richards v. Wisconsin, 520 U.S. 385 (1997) .

Failure to knock and announce will not cause the suppression of evidence.

During conduction of a search, the officer cannot search the places and individuals not listed on the warrant. For instance, if the fireperson was required to go to the basement to find the cause of fire, he went upstairs to find contraband . The contraband may be suppressed as it’s out of scope. However, the officer may detain or arrest anyone present during the search if they find sufficient evidence even if that person was in the list.

Exceptions to warrants

Evidence obtained without a valid warrant should be excluded. The Supreme Court in Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967) held that “searches conducted outside the judicial process, without prior approval are prohibited under the Fourth Amendment, with a few detailed exceptions.” Following are exceptions permit warrantless search.

Plain view doctrine :

- Private view: If an officer is lawfully on the premises or stop the vehicle for a lawful purpose, and “the incriminating character of the item is immediately apparent,” the officers can seize that in plain view, even if it is not on the list of search warrants. If the officer. See Horton v. California, 496 U.S. 128 (1990) .

- Public view: Since individuals have no reasonable expectation of privacy in things exposed to the public, items in public view may be seized without a warrant.

Exigent circumstances : Officers will take immediate actions to secure the place to obtain time to get a warrant or just search warrantless, if they believe that failing to do so will cause the destruction of evidence, threaten public safety, or fleeing. See Illinois v. McArthur, 531 U.S. 326 (2001) . If the exigency is caused by officers, the search violates the 4th Amendment. Se e Kentucky v. King, 563 U.S. 131 (2011).

Hot pursuit : Officers can arrest and search individuals who are suspected of committing a felony . For the pursuit, officers can enter any property to search and seize evidence without warrants. If the crime is not a felony, the exception cannot be applied. See Welsh v. Wisconsin, 466 U.S. 740 (1984) .

Emergency situations : It’s applied to avoid the destruction of evidence, protect officers or the public, or inhibit suspects to flee. Whether an emergency exists is determined objectively from the officer's side.

Automobiles: If the officer has probable cause to believe that the automobile contains evidence of a crime or contraband before the automobile is searched, they can search automobiles, including the trunk and luggage, or other containers which may reasonably contain evidence or contrabands, without a warrant. See Caroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132 (1925) .

Scope: motor, trailers, boats, airplanes, and other transportation.

Consent: A third party with possessory rights of the property may have authority to consent to a search if consent is voluntarily given.

Voluntary: If the consent was given under threats, it’s invalid. To determine whether the consent was valid, courts may evaluate the circumstances when consent was made. For instance, if the officer acquired the consent because they erroneously stated that they have a warrant, the consent given in reliance on that statement does not constitute consent. Se e Bumper v. North Carolina, 391 U.S. 543, 549 (1968) . While failing to disclose the right to withhold consent will not cause the consent invalid. See Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218, 233 (1973) .

Authority: The property should be legally owned, occupied or jointly controlled by the third party. See Frazier v. Cupp, 394 U.S. 731, 740 (1969) .

Scope: Usually it’s limited to the consent, but sometimes may extend to reasonable areas. See Florida v. Jimeno, 500 U.S. 248, 252 (1991) .

Administrative search : It is different from criminal investigation, which aims to search evidence of a regulatory violation or for public interest. S ee Camara v. Mun. Court of San Francisco, 387 U.S. 523, 533 (1967) . There are some administrative searches which needn’t warrants, like vehicle checkpoints and roadblocks, factory or inventory searches, detention of a traveler, cause of fire searches, and so on.

Stop and frisk : If officers have reasonable suspicion that a crime is occurring, they can stop a suspect for weapons to ensure their safety.

A search incident to an arrest may not require a warrant. If the officer just searches a suspect's immediate surroundings to prevent destruction of evidence or secure safety of himself or herself or nearby people. See Warden v. Hayden, 387 US. 294 (1967) .

Legitimacy: Arrest must be lawful and officers have reasonable belief that the automobile contains evidence of the offense of arrest. If the search precedes the arrest, it’s illegal.

Time & area: Search must be contemporaneous in time and place with the arrest.

Scope: the person and his wingspan no matter if it's an open or closed space, locked or unlocked items.

Exception: Need exigent circumstances or search warrant to search contents of a cell phone

Some special types of warrants

Anticipatory warrants : When a police officer is issued a search warrant for contraband or evidence, they are not required to believe that contraband is in a certain place to be searched. Once probable cause of a future triggering condition likely occurs, finding contraband or evidence of a crime in that place turn out to be possible, such a warrant becomes valid. See United States v. Grubbs, supra, 547 U.S. 90 (2006) .

Third-party premises: police officers even can search the place of a person who is not suspected of a crime. See Zurcher v. Stanford Daily, 436 U.S. 547 (1978) .

Warrants for electronically stored information: Rule 41(e)(2)(A) of Federal Rules of Criminal Procedures authorizes police officers the right to search “electronic storage media” or “copying of electronically stored information” with search warrant. officers can copy seized material for later review.

Post-Search Procedural Safeguards

Rule 41(f)(1) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure discusses the federal requirements for returning a warrant. Most jurisdictions impose additional post-search procedural safeguards. For example, many jurisdictions require officers to return a copy of the search warrant to the judge after executing it. This return copy must include information about the search, including a list of what was seized. Similarly, most jurisdictions require officers to give a receipt for seized property.

[Last updated in May of 2022 by the Wex Definitions Team ]

menu of sources

Other references, key internet sources.

- Rights of Suspects and Defendants (Nolo)

- the Constitution

- THE LEGAL PROCESS

- criminal procedure

- legal practice/ethics

- constitutional law

- courts and procedure

- criminal law and procedure

- wex articles

- wex definitions

- criminal law

- WARRANTLESS SEARCH

- REASONABLE SEARCH AND SEIZURE

Teaching Resources for the Honors Program

Introduction to Claim Evidence Warrant

This resource introduces one of the most powerful—and most widely taught—methods for understanding and making arguments in the real world. It has many names: Claim/Evidence/Warrant, the Toulmin system, and others. Whatever you call it, however, learning this approach not only makes your writing stronger but also gives you a tool for critiqueing others’ arguments. It’s an easy-to-use formula for organizing an argument that’s as useful in the workplace as it is in school.

“If everyone’s entitled to their own opinion, why do I need a model for making arguments?”

True, everyone’s equally entitled to their opinions, but that doesn’t mean all opinions are equally persuasive. And it’s often precisely your job to be persuasive in your writing. Claim/Evidence/Warrant (CL/EV/WA) helps you articulate logical—and so persuasive—arguments.

This system has three basic elements (and sometimes three additional elements). Those basic elements are:

Making a point with evidence in writing resembles conversation where you are trying to persuade someone of something.

CONTINUE TO PART 2->

Need help with the Commons?

Email us at [email protected] so we can respond to your questions and requests. Please email from your CUNY email address if possible. Or visit our help site for more information:

- Terms of Service

- Accessibility

- Creative Commons (CC) license unless otherwise noted

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Search Warrant

A search warrant is a court order authorizing law enforcement officials to search an individual’s private residence or other premises for evidence of a crime. The search warrant also allows law enforcement officials to confiscate any evidence they find that is related to the crime. Search warrants are made necessary by the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution , which protects people’s right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure . To explore this concept, consider the following search warrant definition.

Definition of Search Warrant

- A court order authorizing the search of a private premises, or other location, by law enforcement officials.

Obtaining a Search Warrant

A search warrant is an order, issued and signed by a judge , which gives police officers the authority to search a specified place, for the purpose of searching for specified items, or types of materials. According to the 4th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, police are required to prove to the court that probable cause exists, based on direct information, such as the officer’s personal observations, or hearsay information, before a search warrant can be issued.

4th Amendment Rights

The 4th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, addressing the issue of unreasonable searches and seizures, was adopted on March 1, 1792. While the amendment prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures, it sets up a method for obtaining permission to conduct reasonable and necessary searches and seizures. This process requires a warrant be issued by a judge after probable cause has been shown.

Under the 4th Amendment, a search warrant must specify what location is to be search, and what things or people are to be seized, or taken into custody. The text of the 4th Amendment reads:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Search and Seizure

In the United States, the police are required to follow certain rules in conducting searches and seizures. Evidence obtained in an illegal search cannot be used to prosecute the suspect, which motivates the investigators to follow the rules. Specific standards for search and seizure vary by state, and come largely from judicial interpretation. These rules are designed to protect people’s privacy, and to limit the ability of the police to invade areas that a person expects to be private.

What is Considered to be a Search

There are two main questions that the court considers in determining whether a police investigation is considered to be a search.

- Did the individual expect some degree of privacy at the location

- Is the individual’s expectation of privacy reasonable

If the answer to both of these questions is “yes,” it is a search. If the answer to either or both of these questions is “no,” it is not a search for legal purposes.

For example:

David is arrested on suspicion of embezzlement from his company, and police have so far been denied a warrant to search his home and car for evidence, as they cannot provide reasonable suspicion that David is the one who took the money.

During their investigation, police pick up two bags of trash before the garbage truck picked them up from the curb in front of David’s home. In one bag, police find a wadded up piece of paper containing some financial scribblings, as well as two off-shore bank account numbers.

There is no expectation of privacy in regard to the things people throw into the trash, even if the trash is at their home or other private place. Once the trash goes out to a place where the public has access, there is no privacy. Because of this, the seizure and subsequent search of David’s trash is not considered to be a search, and no warrant was needed.

What Powers Does a Search Warrant Give Police

A search warrant gives police authority to enter a specified premises without permission of the owner or suspect. If the warrant specifies an area inside the premises to be searched, police must limit their search to that area. In most cases, the warrant also specifies the evidence sought, which also limits the search parameters.

For example, if a search warrant specifies that police may search a suspect’s house, they must limit their search to the actual residence, even if they become suspicious that there may be evidence in a shed at the back of the property. If the police wish to search the shed, or any other buildings, they must obtain a separate search warrant.

There are exceptions to this rule however, as police do have the power to search beyond the scope of a warrant to ensure their own safety, or the safety of other people. Other exceptions include:

- Searching additional rooms to stop a person from destroying evidence

- Searching for additional evidence beyond what the warrant specifies based on items found

- Searching for additional evidence based on evidence in plain sight during the search

Example of Search Warrant Seizure

Police have a search warrant to search Brad’s kitchen. As they enter the house, police must walk through the living room to reach the kitchen. While walking through the living room, the officers see several baggies of cocaine and a scale sitting on the coffee table. In this example of search warrant deviation, although the living room and drugs were not included in the warrant, the police can legally seize the evidence.

Warrantless Search

There are many circumstances when a warrantless search falls within the bounds of the law. In such cases, the police have the authority to search a person, or his property, without first obtaining a search warrant. Some of these instances for warrantless search include:

Consent Searches

If a person voluntarily agrees to let police officers conduct the search, no warrant is needed. On the other hand, a person can refuse to give consent to the search and can also revoke consent at any point while the search is taking place. Consent is not valid if the individual was coerced by police.

Searches in Connection with an Arrest

When an individual is arrested, police have the authority to search person, as well as the areas immediately surrounding him, without a search warrant. In some jurisdictions, the area immediately surrounding a suspect is limited to his arm span.

Car Searches

Police can search an individual’s car if there is probable cause to believe it contains evidence of a crime. Illegal items in plain view inside the vehicle gives police such probable cause. In addition, police may conduct a search of a suspect’s person and car for their own safety. Such a search is for weapons, but they may also legitimately find contraband during such a search.

Items in Plain View

The basis of the warrantless search is the “ plain view doctrine .” This states that police can seize illegal items that are in plain view, with no warrant required, if:

- The officer is present and can plainly see the evidence

- The officer has the legal right to access the object

- It is immediately apparent that the object is evidence of a crime

- In addition, spotting illegal items left in plain view may be probable cause for the officer to obtain a search warrant, or to have the existing warrant expanded.

Example of Search Warrant Case

On May 23, 1957, police were looking for a bombing suspect named Virgil Ogletree, when they arrived at the home of Dollree Mapp, demanding entrance. Police believed, based on a tip, that the man was holding out inside Ms. Mapp’s home. Ms. Mapp, a young black woman, stood up to the white police officers, asking for a search warrant. When they could not produce a warrant, she refused to let them in.

Three hours later, four police cars arrived at Mapp’s house. Afraid, Mapp didn’t answer the door when the police knocked. The police barged in anyway, and Mapp again asked to see a search warrant. When she was shown a piece of paper an officer said was a warrant, Mapp grabbed it and put it inside her blouse. The officer reached inside Mapp’s blouse and snatched the paper back.

The officers handcuffed Ms. Mapp, then proceeded to search her entire house, including her daughter’s room, to discover there was no fugitive there. What officers did find was a gun, a nude sketch, and books that were considered obscene at the time, which Mapp stated belonged to a previous boarder. Police arrested Mapp and charged her with felony possession of obscene materials.

During the trial , officers were unable to produce the search warrant. In fact, it was never to be seen again. The fugitive was later found at a neighbor’s house, and the charges against Mapp were dropped.

When Mapp refused to testify in court against an acquaintance, she was again charged and prosecuted on the obscenity charges. A jury found her guilty in 1958, after which she filed a series of appeals based on the First Amendment right to freedom of expression.

The case found its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the justices laughed about the absurdity of the state’s obscenity law before shifting its focus to the manner in which the evidence used against Ms. Mapp was obtained.

Prior to Mapp’s case, many states made a practice of allowing all evidence into trial, even if it was obtained illegally, as it had been ruled that the Fourth Amendment did not bind the states. The five Supreme Court justices shocked the legal world when they overturned Mapp’s conviction, and made it clear that, from that point on, no state could infringe upon a person’s right to be free from illegal searches and seizures, and therefore could not take into consideration illegally obtained evidence.

The toll of that particular legal bell, in the 1961 case of Mapp v. Ohio , still rings throughout the modern judicial system, as search warrants are serious business, and any evidence obtained illegally is likely to be thrown out.

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Authority – The right or power to make decisions, to give orders, or to control something or someone.

- Coercion – The act of using force or intimidation to ensure compliance.

- Consent – To approve, permit, or agree

- Criminal Charge – A formal accusation by a prosecuting authority that an individual has committed a crime.

- Defendant – A party against whom a lawsuit has been filed in civil court, or who has been accused of, or charged with, a crime or offense.

- Probable Cause – Facts and circumstances leading to the belief that an accused person has committed a crime. Probable cause does not arise from a suspicion or a “hunch,” but from observable facts and circumstances.

- Trial – A formal presentation of evidence before a judge and jury for the purpose of determining guilt or innocence in a criminal case, or to make a determination in a civil matter.

- Warrant – A writ issued by a court or other legal official authorizing law enforcement or other agency to make an arrest, search a premises, or take some other action related to the administration of justice.

Search Warrants Essays

The fourth amendment in the united states, popular essay topics.

- American Dream

- Artificial Intelligence

- Black Lives Matter

- Bullying Essay

- Career Goals Essay

- Causes of the Civil War

- Child Abusing

- Civil Rights Movement

- Community Service

- Cultural Identity

- Cyber Bullying

- Death Penalty

- Depression Essay

- Domestic Violence

- Freedom of Speech

- Global Warming

- Gun Control

- Human Trafficking

- I Believe Essay

- Immigration

- Importance of Education

- Israel and Palestine Conflict

- Leadership Essay

- Legalizing Marijuanas

- Mental Health

- National Honor Society

- Police Brutality

- Pollution Essay

- Racism Essay

- Romeo and Juliet

- Same Sex Marriages

- Social Media

- The Great Gatsby

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- Time Management

- To Kill a Mockingbird

- Violent Video Games

- What Makes You Unique

- Why I Want to Be a Nurse

- Send us an e-mail

What Is A Warrant In Writing? (Explained + 20 Examples)

Ever wondered how writers make their claims stick?

That’s where warrants come in, bridging the gap between evidence and conclusion.

What is a warrant in writing?

A warrant in writing connects a claim to evidence, serving as the underlying logic, ethical principle, or emotional appeal that makes an argument persuasive. It’s the bridge that ensures an argument’s coherence and strength.

In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about warrants in writing.

What Is a Warrant in Writing (Long Explanation)?

Table of Contents

When we talk about a warrant in writing, we’re diving into the backbone of persuasive and argumentative writing.

It’s not the flashy evidence or the bold claim that gets the spotlight.

Rather, it’s the unsung hero that connects the two, ensuring your argument stands strong and coherent.

Through trial and error, I’ve learned that a well-crafted warrant can turn a skeptical reader into a believer, highlighting the nuanced art of persuasion that goes beyond mere facts.

Imagine you’re building a bridge.

Your claim is on one side, your evidence on the other, and the warrant is what lies beneath, holding it all together.

It answers the silent question of “Why does this evidence support my claim?” without which your argument might just fall into the water.

Warrants are based on logic, ethics, or emotions, tailored to your audience’s beliefs and values.

They’re not always explicitly stated but are crucial for the argument’s acceptability.

Think of them as the glue that binds your argument, making it not just a collection of statements but a coherent, persuasive message.

Types of Warrants in Writing (10 Types)

Warrants come in various forms, each serving a unique purpose in strengthening your argument.

Let’s explore the ten types of warrants that can transform your writing:

- Logical Warrants – These are grounded in logic, appealing to the reader’s sense of reason.

- Ethical Warrants – These appeal to the reader’s sense of morality and ethics.

- Emotional Warrants – Aimed at stirring the reader’s emotions.

- Authoritative Warrants – Rely on the credibility of the source or author.

- Analogical Warrants – Use analogies to draw parallels between concepts.

- Causal Warrants – Establish a cause-effect relationship.

- Generalization Warrants – Apply a general principle to a specific case.

- Sign Warrants – Use signs or indicators as evidence for the claim.

- Analogy Warrants – Similar to analogical but often use metaphors or similes for comparison.

- Statistical Warrants – Use statistics and numerical data to support the claim.

Understanding these types is crucial for effectively incorporating warrants into your writing, ensuring your arguments are not only heard but resonate with your audience.

20 Examples of Warrants in Writing

Before we dive into the examples, it’s essential to grasp the significance of each warrant type.

By understanding and applying these warrants, you can enhance the persuasiveness of your writing, making your arguments more compelling and impactful.

Logical Warrants: The Bridge of Reason

Imagine arguing that a well-balanced diet improves academic performance.

The logical warrant here connects the nutritional benefits of a balanced diet to enhanced brain function and, consequently, better academic outcomes.

It’s the reasoning that if your body gets the right nutrients, your brain operates more efficiently.

And that leads to improved academic performance.

Ethical Warrants: The Moral Compass

Consider the claim that companies should adopt more sustainable practices.

The ethical warrant appeals to the moral obligation of preserving the environment for future generations.

It’s the understanding that, as stewards of the planet, companies have a moral duty to minimize environmental harm, making the argument not just logical but morally compelling.

Emotional Warrants: The Heart’s Argument

Take the argument that animal shelters should receive more funding.

The emotional warrant plays on the audience’s compassion for animals, linking the plight of shelter animals to the emotional response of the audience.

It’s the heart-tugging connection that motivates action, not just through logic but through feeling.

Authoritative Warrants: The Voice of Credibility

Arguing that vaccinations are safe and effective might draw on authoritative warrants.

This warrant relies on the credibility of medical institutions and experts, asserting that if trusted sources endorse vaccinations, they must be safe and beneficial.

It’s the trust in authority that bolsters the argument’s weight.

Analogical Warrants: Connecting Dots with Similarity

If arguing for the importance of cybersecurity measures in small businesses, you might use an analogical warrant comparing cyber threats to burglaries.

This analogy highlights the necessity of protective measures, both physical and digital, to safeguard valuable assets.

Analogical warrants make the argument relatable and understandable.

Causal Warrants: Cause and Effect

In arguing that excessive screen time leads to poor sleep patterns, the causal warrant establishes a cause-effect relationship between screen time and sleep quality.

It’s the logical link that prolonged exposure to screens before bedtime disrupts sleep.

Casual warrants ground the argument in a cause-and-effect reality.

Generalization Warrants: The Broad Stroke

When claiming that reading enhances empathy, a generalization warrant might apply the broad principle that exposure to diverse perspectives through literature broadens one’s understanding and acceptance of different life experiences.

This warrant generalizes the benefit of reading to a wider application.

It suggests that engaging with a variety of characters and stories inherently fosters empathy among readers.

Sign Warrants: Reading the Signs

Consider the argument that a thriving local arts scene indicates a city’s economic health.

The sign warrant here uses the vibrancy of the arts community as an indicator or sign of broader economic prosperity.

It’s the interpretation of thriving cultural initiatives as evidence of sufficient disposable income and investment in community well-being, linking cultural vibrancy to economic health.

Analogy Warrants: Seeing in a New Light

In advocating for renewable energy sources, an analogy warrant might compare the transition from fossil fuels to renewables to upgrading from an old, inefficient car to a modern, fuel-efficient model.

This analogy makes the concept more accessible and relatable.

Analogy warrants illustrate the benefits of modernization and efficiency in energy sources through a familiar scenario.

Statistical Warrants: The Power of Numbers

This warrant leans on numerical data to substantiate the claim.

Arguing for the effectiveness of a new teaching method, a statistical warrant could highlight improved test scores in classes where the method was implemented.

These warrants offers concrete evidence that the new teaching approach leads to better academic outcomes.

Generalization Warrants: The Universal Principle

The warrant suggests that the benefits observed in the past are likely to recur under similar systems.

When arguing that democracy is the most effective form of government, a generalization warrant might draw from historical examples where democratic systems led to prosperous and stable societies.

This warrant applies the broad principle that, given the success of democracy across various contexts and times, it can be considered the best form of governance.

It’s a leap from specific historical instances to a universal conclusion.

Sign Warrants: The Indicator

In the debate over economic policies, one might claim that low unemployment rates signal a healthy economy.

The sign warrant here interprets low unemployment as an indicator of economic strength, suggesting that when more people are employed, it reflects well on the economic policies in place.

This warrant relies on the observable condition (employment rates) as a sign of broader economic health.

It makes a case for the effectiveness of current policies.

Analogy Warrants: Visual Metaphors

Advocating for regular breaks from digital devices, an analogy warrant could compare digital consumption to eating junk food.

For example, just as the latter requires moderation to maintain physical health, the former needs limits to preserve mental well-being.

This analogy helps audiences understand the concept of digital detox by relating it to a familiar practice of dietary moderation, enhancing the argument’s relatability and persuasiveness.

Statistical Warrants: Facts and Figures

This approach uses hard numbers to demonstrate the direct consequences of inaction.

Presenting an argument for urgent action on climate change, a statistical warrant might utilize data showing rising global temperatures and increasing frequency of natural disasters.

It aims to convince skeptics through undeniable evidence that climate change is not only real but also an immediate threat.

Logical Warrants: Deductive Reasoning

This warrant connects the dots between individual immunization and community health benefits.

In discussions about public health, arguing that vaccinations prevent widespread outbreaks relies on the logical warrant that vaccines build herd immunity, making it harder for diseases to spread.

Logical warrants employ deductive reasoning to make a case for widespread vaccination programs.

Ethical Warrants: The Right Thing to Do

Arguing for equal access to education, the ethical warrant might stem from the belief that education is a fundamental human right.

This warrant appeals to the sense of fairness and justice, positing that denying anyone access to education is morally wrong.

It’s an argument built on the ethical principle that equality in education is not just beneficial but a moral imperative.

Emotional Warrants: Pathos in Play

When making a case for conservation efforts, an emotional warrant could highlight the plight of endangered species facing extinction.

By evoking empathy for these animals, the warrant seeks to motivate action based on emotional response.

You can leverage the power of pathos to make the argument for conservation not just logical but emotionally compelling.

In my own writing, I’ve discovered that the most compelling arguments are those where the warrant is implicitly understood, yet powerfully resonant with the audience’s core beliefs.

Authoritative Warrants: Expert Endorsements

In advocating for a new health guideline, using authoritative warrants involves citing recommendations from health organizations or experts.

This type of warrant leans on the credibility and expertise of authorities in the field.

The warrant suggests that if such entities endorse a guideline, it is based on solid research and should be followed.

It’s an appeal to authority that lends weight to the argument through expert endorsement.

Causal Warrants: Tracing Effects to Causes

Arguing that social media can result in more loneliness and isolation, a causal warrant examines the effect (loneliness) and traces it back to its cause (social media usage).

This warrant establishes a direct link between the cause and effect.

Casual warrants offer a logical explanation for how too much social media exposure can disrupt and decrease your mental health.

Analogical Warrants: Bridging Concepts

In discussions about governance and policy, comparing the state to a ship and its government to the crew provides an analogical warrant that governance requires cooperation and direction, much like navigating a ship.

This analogy helps illustrate the complexity of governance and the importance of unified direction and teamwork.

Analogical warrants make the argument more accessible and understandable through the comparison.

Here is a good video about warrants in writing:

Final Thoughts: What Is a Warrant in Writing?

Understanding warrants is key to unlocking the full potential of your arguments.

Reflecting on my writing journey, I’ve come to appreciate that mastering the use of warrants is akin to fine-tuning a musical instrument—it’s delicate, requires practice, and when done right, makes your argument sing.

Read This Next:

- 50 Best Counterclaim Transition Words (+ Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- What Is A Lens In Writing? (The Ultimate Guide)

- What Is On-Demand Writing? (Explained with Examples

What is a Warrant in Writing?

Written by Haley Boyce

Before we do a swan dive into warrants, we will need to wade the waters of its origin. Warrants are just one part of a bigger product known as the rhetorical analysis essay.

Rhetoric is the term used to describe ideas about different texts. When you read a story (or article, essay, journal, etc.) and share your thoughts about it, those thoughts are now called rhetoric. When you read a text and have thoughts about them, those thoughts are called rhetoric. It’s one of those words that sounds fancy and feels a little intimidating when, truly, it’s got a relatively simple definition.

Warrants are similar in that they, too, sound super complicated but have a somewhat simple meaning. The difference, however, is that warrants are best defined with a lengthier explanation and examples. So, let’s get down to it.

What is the Definition of a Warrant in Writing?

In persuasive writing you will make a claim at the beginning of your essay. Then the rest of your essay will be spent proving why your claim is correct and why your reader should agree with you.

The warrant is the connection the reader can make between the claim and evidence.

When a writer makes a claim and provides evidence, they will explain why the evidence supports the claim or they will imply the connection but leave the clarity as an assumption for the reader to make.

What are the Different Types of Warrants in Writing?

There are two types of warrants in writing. The

Explicit Warrant:

An explicit warrant is used when a writer feels that the argument will need stronger support for the reader to agree with, or even understand. Explicit warrants are identifiable when the writer clearly explains why the evidence they are providing supports the claim.

Implicit Warrant:

An implicit warrant is used when an argument is strong enough without blatantly stating why the connection between the claim and the evidence. For example:

- Claim: Flying in a hot air balloon is safe.

- Support: The Federal Aviation Administration regulates hot air balloon safety.

- Warrant: The FAA is trustworthy and would not permit unsafe travel.

Stephen Toulmin Warrants Some Attention

In “The Uses of Argument”, he posited that formal logic was too abstract and an inadequate representation of how we actually argue. Roy Pea, a professor of learning sciences and education and director of the Stanford Center for Innovations in Learning at Stanford University said that Toulmin “ “argued that if we want to understand questions of ethics, science and logic, we have to inquire into the everyday situations in which they arise.”

Determined to set a new standard for how we argue, especially in academic papers, Toulmin developed what we now know in academia as the Toulmin Model. The model is a tool in the analysis of arguments, allowing one to weigh the strengths and weaknesses in arguments. This is the model used when we write warrants.

Responses to this question vary by philosopher and professor alike, but there are several agreed upon factors to consider while writing a warrant. Whether your warrant is explicit or implicit, take the following into consideration as you write.

A good warrant should:

- Be a reasonable interpretation of the facts

- Not make illogical leaps of interpretation

- Not assume more than the evidence supports

- Consider and prepare to respond to possible counterarguments

More to consider while writing your warrant:

- Do you readers already know the warrant?

- Will readers believe the warrant is true?

- Will readers see the connection to the claim and evidence the same way that you do? If not, you will need to reconsider your evidence or make your warrant explicit.

- Because the purpose of having a warrant is to persuade your reader to agree with you, will your reader see the relevance of your argument as important to their own lives? Again, if the answer to this is “no”, then you will need to explicitly state your warrant.

Presenting Counterarguments Can Be the Most Powerful Way to Support Your Own Point

In persuasive writing, the counterargument must be acknowledged in some way. Doing so gives credibility to your argument because it shows that you are writing from a sound mind that is not ignorant to opposing viewpoints. It says to the reader, “I believe this to be true because I have looked at all possibilities and see how my belief is the correct one.”

A simple structure for writing a counterargument can go something like this:

- Identify the opposing argument.

- Respond to the opposing argument by discussing the reasons the argument is illogical or weak.

- Provide examples or evidence to show why the opposing argument is illogical or weak.

- Finally, re-state your own argument and why it is stronger than the counterargument.

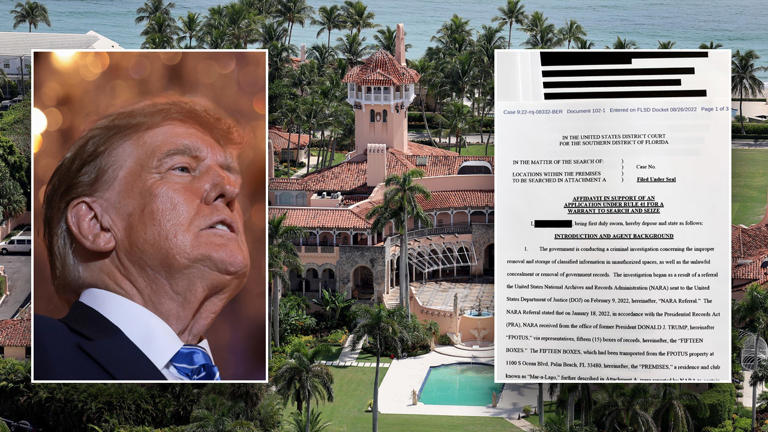

What unsealed Trump search warrant papers suggest about federal investigation

A spokesman for the former president called the raid of Mar-a-Lago "outrageous."

A redacted copy of the warrant and related papers from the FBI's search of Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago indicates that the Justice Department is investigating the potential violation of at least three separate criminal statutes, including under the Espionage Act.

The filing -- released Friday by the court, at the government's request and with Trump's agreement -- includes the warrant, two attachments ("Attachment A" and "Attachment B") and an inventory of what was taken from Mar-a-Lago during the FBI operation on Monday in Palm Beach, Florida.

Attachment B states that the property to be seized by agents includes "all physical documents and records constituting evidence, contraband, fruits of crime or other items illegally possessed" in violation of 18 USC 793, a statute under the Espionage Act involving the gathering, transmitting or loss of defense information; 18 USC 2071, which involves any federal government employee who willfully and unlawfully conceals, removes, mutilates, obliterates, falsifies or destroys public records; and 18 USC 1519, obstruction of justice.

Under the receipt, showing property that was seized from Trump's estate, agents note they recovered 11 sets of documents of various classifications ranging from confidential to top secret (TS) and sensitive compartmented information (SCI).

The receipt identifies one set referring to "various classified/TS/SCI documents," four sets of top secret documents, three sets of secret documents and three sets of documents described as confidential.

Other materials included in the receipt are an item labeled "Info re: President of France," an executive grant of clemency for Trump ally Roger Stone, binders of photos, a "potential presidential record" and a leather-bound box of documents.

It appears that there were 27 boxes taken.

The Washington Post previously reported that classified documents related to nuclear weapons were among the items sought by the federal agents at Mar-a-Lago.

Sources had told ABC News that the search was in connection to documents that Trump took with him when he departed Washington, including some records the National Archives said were marked classified.

In a statement on Friday, Trump spokesman Taylor Budowich contended that the documents were declassified and played down the items that were taken as "the President's picture books" and "a 'hand written note."

"This raid of President Trump's home was not just unprecedented, but unnecessary—and now they are leaking lies and innuendos to try to explain away the weaponization of government against their dominant political opponent. This is outrageous," Budowich said.

Whether or not the materials taken by the government were classified may not matter for two of the criminal statutes cited in the warrant, according to ABC News chief legal analyst Dan Abrams.

"As I look at these statutes, I'm focused less on the question that the Trump team has been talking about, which is the classification of the documents -- which is obviously very important in a macro picture -- but in a strictly legal sense, [for] two of these three statutes, that may not even be the critical question," Abrams told ABC's David Muir in a special report on Friday following the release of the search warrant.

One of the statutes, 18 USC 1519, relates to the destruction, alteration or falsification of records.

"That is the statue I am singularly most interested in here," Abrams said.

The other, 18 USC 793, a statute under the Espionage Act that involves the gathering, transmitting or loss of defense information, also doesn't specifically relate to classified information, Abrams said.

"It can relate to anything related to the national defense," he said. "That could be a very serious felony there."

The release of the search warrant papers comes after a daylong back-and-forth between Trump and the Department of Justice.

On Thursday afternoon, Attorney General Merrick Garland spoke for the first time about Monday's search and revealed that he personally authorized the decision to seek a search warrant, which drew intense criticism from Republicans as a partisan attack on Trump.

In his speech, which lasted less than five minutes, Garland defended the integrity of federal law enforcement and, without commenting on any specifics related to the Trump investigation, said: "Faithful adherence to the rule of law is the bedrock principle of the Justice Department and of our democracy. Upholding the rule of law means applying the law evenly without fear or favor."

"Under my watch, that is precisely what the Justice Department is doing," Garland said.

He said that the Justice Department had sought to keep the search of Mar-a-Lago from public view but that Trump then disclosed it in a statement Monday night.

Citing "the substantial public interest in this matter," Garland said the government decided to file a motion seeking to unseal the warrant.

Trump, who had been able to release the warrant earlier without the government's motion, said on his social media platform Truth Social on Thursday night that he wanted the "the immediate release of those documents."

On Friday, the court released the redacted versions.

Congressional Republicans have echoed Trump in criticizing the Justice Department's investigation, which is one of multiple legal issues Trump faces. (He denies wrongdoing in each.)

Republicans on the House Intelligence Committee defended Trump on Friday while attacking the Department of Justice and FBI during a press conference on Capitol Hill.

"President Donald Trump is Joe Biden's most likeliest political opponent in 2024 and this is less than 100 days from critical midterm elections," Rep. Elise Stefanik, the No. 3 House Republican, said Friday. "The FBI raid of President Trump is a complete abuse and overreach of its authority."

Stefanik vowed an investigation into the search if the GOP retakes the House in November.

"House Republicans are committed to immediate oversight, accountability and a fulsome investigation to provide needed transparency and answers to the American people," she said.

ABC News' Meredith Deliso and Allison Pecorin contributed to this report.

Related Topics

- Donald Trump

- Research Paper

- Book Report

- Book Review

- Movie Review

- Dissertation

- Thesis Proposal

- Research Proposal

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation Introduction

- Dissertation Review

- Dissertat. Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- Admission Essay

- Scholarship Essay

- Personal Statement

- Proofreading

- Speech Presentation

- Math Problem

- Article Critique

- Annotated Bibliography

- Reaction Paper

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Statistics Project

- Multiple Choice Questions

- Resume Writing

- Other (Not Listed)

Search Warrants (Essay Sample)

I wrote a paper for a customer on the different search warranties authorized by the federal government. It also covers the process by which a search warrant is issued and sought, with emphasis on the Fourth Amendment requirements.

Other Topics:

- Same sex marriage Description: Same sex marriage Law Essay Undergraduate level... 2 pages/≈550 words | APA | Law | Essay |

- Breach of Contract and Law suit Description: Breach of Contract and Law suit Law Essay Undergraduate level... 5 pages/≈1375 words | APA | Law | Essay |

- Human Rights In Syria Description: Human Rights In Syria Law Essay Undergraduate level... 1 page/≈275 words | APA | Law | Essay |

- Exchange your samples for free Unlocks.

- 24/7 Support

Judge unseals FBI files in Trump classified documents case, including detailed timeline of Mar-a-Lago raid

T he judge presiding over former President Trump’s classified documents case unsealed a slew of documents Monday evening pertaining to the FBI’s investigation into the former president and the FBI’s raid on his Mar-a-Lago estate in 2022.

U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon ordered the release of the new documents, which provided a detailed look into the personnel involved in the raid on Mar-a-Lago and a play-by-play timeline of the raid. One of the documents is an FBI file that suggests the agency's investigation into Trump’s alleged mishandling of classified documents was dubbed "Plasmic Echo."

"This document contains information that is restricted to case participants," the document reads. It adds, "PLASMIC ECHO; Mishandling Classified or National Defense Information, Unknown Subject; Sensitive Investigation Matter."

READ THE ‘PLASMIC ECHO' DOCUMENT – APP USERS, CLICK HERE:

Another unsealed FBI memo memorialized the role of Attorney General Merrick Garland in the investigation.

FBI RAIDS TRUMP'S MAR-A-LAGO: 'UNPRECEDENTED' FOR AGENCY TO EXECUTE SEARCH WARRANT AGAINST FORMER PRESIDENT

READ ON THE FOX NEWS APP

In a document dated March 30, 2022, Garland provided his approval to allow the investigation into Trump’s alleged mishandling of classified documents to upgrade to a "full investigation."

"This email conveys Department of Justice (DOJ) Attorney General (AG) [Merrick Garland] approval for conversion to a full investigation," a synopsis of the restricted document reads.

Another unsealed FBI document, dated Aug. 17, 2022, detailed the FBI’s unprecedented raid on Trump’s Palm Beach estate days earlier on Aug 8, 2022.

The documents describe the personnel involved in the raid and provide a by-the-minute breakdown of the incident beginning with the FBI's arrival at Mar-a-Lago.

GOP SLAMS 'WEAPONIZATION' OF DOJ AFTER TRUMP'S MAR-A-LAGO RAIDED BY FBI; DEMS CALL IT 'ACCOUNTABILITY'

It includes entering a "45 Office" safe and later taking seized documents back to Washington – ultimately to the FBI’s Washington Field Office (WFO).

"A search warrant, 22-mj-8332-BER, issued in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida on August 5, 2022, was executed at 1100 South Ocean Boulevard, Palm Beach, Florida 33480 at 10:33 a.m. on August 8, 2022," the document reads.

TRUMP SAYS MAR-A-LAGO HOME IN FLORIDA 'UNDER SIEGE' BY FBI AGENTS

"Prior to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) team’s entry onto the MAL premises, FBI leadership informed and coordinated with local United States Secret service (USSS) leadership. Local USSS facilitated entry onto the premises, provided escort and access to various locations within, and posted USSS personnel in locations where the FBI team conducted searches," it continued.

The personnel at the raid consisted of four agents from the FBI WFO, one FBI Headquarters personnel, 25 agents from the FBI Miami Field Office, one DOJ Counterintelligence and Export Control Section attorney and one attorney from the United States Attorneys Office Southern District of Florida.

Trump famously said the morning of the raid that his Mar-a-Lago estate was "under siege" by the FBI.

He also claimed to be in full cooperation with investigators.

According to the unsealed documents, the timeline for the raid is as followed, with approximate times.

08:59 a.m. — FBI team entered the Mar-a-Lago premises

09:01 a.m. — Entry photographs of exterior initiated

09:14 a.m. — Telephonic contact with attorney [name redacted] attempted

09:36 a.m. — Telephonic contact established with [name redacted]

10:13 a.m. — CCTV activated on Mar-a-Lago premises

10:33 a.m. — Search of Mar-a-Lago initiated

10:55 a.m. — Entry photographs resumed

10:55 a.m. — Filter Team review of "45 Office" initiated

01:33 p.m. — US Attorney’s Office SDFL approves FBI entry in "45 Office" safe

02:23 p.m. — Exit photos of "45 Office" initiated

04:33 p.m. — Search of Mar-a-Lago premises concluded

06:19 p.m. — Receipt for Property provided to Attorney [name redacted]

07:52 p.m. — Seized evidence arrived at FBI Field Office Miami

08:18 p.m. — Seized evidence secured in FBI Field Office Miami temporary storage

07:08 a.m. — Seized evidence removed from FBI Field Office Miami temporary storage

07:13 a.m. — Convoy briefing provided by FBI Field Office Miami SWAT Team Leader

07:54 a.m. — Seized evidence departed FBI Field Office Miami

08:34 a.m. — Seized evidence arrived at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport (FLL)

08:35 a.m. — Seized evidence loaded on aircraft

08:49 a.m. — Aircraft departs FLL

11:00 a.m. — Aircraft arrives at Reagan International Airport (DCA)

11:15 a.m. — FBI Field Office Miami Filter Team Lead transfers potentially privileged seized evidence to FBI Washington Field Office Filter Team

11:20 a.m. — Seized evidence departs DCA

11:50 a.m. — Seized evidence arrives at FBI Washington Field Office.

Original article source: Judge unseals FBI files in Trump classified documents case, including detailed timeline of Mar-a-Lago raid

Judge in Trump’s hush money case allows prosecutors to discuss 'Access Hollywood' tape and affairs as watershed trial begins

Donald Trump made history Monday as the first former president to stand trial on criminal charges — and the official start of jury selection quickly highlighted his polarizing impact on the public.

After the first 96 prospective jurors were brought into a New York courtroom, Judge Juan Merchan asked whether any of those assembled could not be "fair and impartial." More than half raised their hands and were excused from serving on the jury.

The watershed moment for American politics, the presidential election and Trump himself comes as Trump is the presumptive Republican nominee for president. He has pleaded not guilty to 34 counts of falsifying business records, a low-level felony punishable by up to four years in prison.

“The name of this case is the People of the State of New York versus Donald Trump,” Merchan told the initial pool of jurors in the afternoon. Trump stood and turned around when he was introduced as the defendant and gave the prospective jurors — some of whom were staring at him intently — a little tight-lipped smirk.

Trump had his eyes closed for a period of time as the judge was reading the potential jurors his instructions, and his eyes looked red and bloodshot when he opened them and peered at the judge.

After the court day concluded, Trump told reporters in a hallway the case is "a scam. It’s a political witch hunt. It continues, and it continues forever, and we’re not going to be given a fair job. It’s a very, very sad thing."

The jury selection process started slowly — the pool wasn't brought in until the afternoon, and after the initial group of those who said they couldn't be fair were excused, another nine were excused after saying they couldn't serve for other reasons. By the end of the day, nine other jurors had answered preliminary questions — although one wound up being excused — and were scheduled to face follow-up questions on Tuesday morning.

The process also got off to a slow start because lawyers from both sides argued over some of the more sensational evidence that prosecutors from Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg's office hope to use to show why Trump was eager to bury negative stories about him during the 2016 presidential election.

Prosecutors allege then-candidate Trump took part in a scheme with his then-lawyer Michael Cohen and the publisher of the National Enquirer to suppress scandalous stories about him in the run-up to Election Day.

One of those stories involved porn star Stormy Daniels , who alleged she had a sexual encounter with Trump in 2006. Trump has denied the claim, and Cohen paid Daniels $130,000 in October 2016 to keep quiet about the allegation. After he was elected, Trump repaid Cohen in payments recorded as legal fees at his company —documents the DA alleges were falsified to keep the hush money payments secret.

The trial is an opportunity for the former president to face off with Merchan, whom Trump has frequently attacked publicly in the run-up to the trial. The judge addressed Trump directly at one point, issuing him standard court warnings that were made more dramatic by Trump's status as a former president, his frequent public attacks on the judge and his many disruptions in his civil trials last year. "If you disrupt the proceedings we can proceed with the trial in your absence. … Do you understand?" the judge asked. "I do," Trump replied.

Merchan also warned Trump that if he fails to show up in court without any explanation, a warrant would be issued for his arrest.

The back and forth came after Merchan had heard arguments about the alleged “catch and kill” scheme, the infamous “Access Hollywood” tape and the allegations of sexual assault from various women that came out during the campaign — all while Trump sat at counsel table with little visible reaction.

Merchan greenlighted a request from prosecutor Joshua Steinglass to show jurors during the trial some headlines from the Enquirer from the 2016 Republican presidential primary campaign that they contend were part of the overall scheme to boost Trump, including stories trashing then-Trump rivals Ben Carson and Sens. Marco Rubio, of Florida, and Ted Cruz, of Texas.

The prosecutor said he also hoped to elicit information about the timing of Trump's alleged affair with another woman whom the Enquirer paid to keep quiet ahead of the election, former Playboy model Karen McDougal . Steinglass said they didn't plan to elicit "salacious details," but did want to note that the timing of the alleged affair was while Melania Trump was pregnant with Trump's child and the baby was a newborn. He said the information was relevant because it showed why Trump wanted to suppress it ahead of the election.

The judge said he'd allow testimony about the alleged affair, but not the information about Melania Trump.

Steinglass also asked Merchan to reconsider his earlier ruling that the jury not hear the notorious " Access Hollywood " tape, on which Trump was caught on a hot mic saying he can grope women without their consent because "when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything."

Audio from the 2005 hot mic moment became public in October 2016, and prosecutors contend that's why Trump was eager to silence Daniels. Steinglass also asked the judge to allow in a snippet from Trump's deposition in writer E. Jean Carroll's defamation case against him, where he defended the comment, saying, "Historically, that's true with stars."

Merchan said he still believes the tape itself is "prejudicial" and "should not come in" to evidence, but he said he would allow prosecutors to use a transcript of the tape. “The testimony from the E. Jean Carroll deposition should not come in either,” the judge added.

The judge also shot down prosecutors' suggestion that they may try to mention other women who came forward after the "Access Hollywood" tape became public to accuse Trump of assault, calling it "complete hearsay."

Later, prosecutors asked the judge to sanction Trump for posts they said violated a gag order barring him from publicly attacking witnesses. Prosecutor Christopher Conroy argued Trump should be fined $3,000 for three social media posts that were critical of Cohen and Daniels. “Not included is another post from this morning,” Conroy said, asking the judge to “remind” Trump that “he is a criminal defendant, and like all criminal defendants he is subject to court supervision.”

Blanche argued that the posts did not violate the gag order, and said Trump was “responding to salacious, repeated, vehement attacks by these witnesses.”

The judge did not immediately issue a ruling, and said he’d hear arguments on the issue on April 23.

Cohen told NBC News in a statement afterward that the proposed penalty was not severe enough. “Donald knows the damage his posts inflict on targeted individuals. A $1,000 per post fine will do nothing to curtail future violations,” he said.

In a ruling later in the day, the judge sided with the prosecution by giving Trump's lawyers 24 hours to produce the exhibits and evidence they plan to use at trial. “You have 24 hours. Whatever you don’t identify in the next 24 hours, you will be precluded from using,” the judge told Blanche.

Trump maintains the DA's case is part of a Democratic conspiracy against him, a claim he has used to galvanize his supporters and rake in millions of dollars in fundraising for his campaign. Bragg, the Manhattan DA, is a Democrat, and Trump has falsely claimed that he's doing the bidding of President Joe Biden.

The criminal case was the f irst o f fo ur brought against Trump in four different jurisdictions and is the only case definitively set to go to trial before the election.

Because Trump is required to be in court four days a week (the trial does not take place on Wednesdays), his ability to campaign in person is limited to times the court is not in session.

The jury selection process is expected to take one to two weeks. Two sources with direct knowledge of the situation told NBC News that 6,000 jurors have been called to the Manhattan criminal courts this week — 2,000 more than in a typical week.

During jury selection, eighteen jurors are put in the jury box at a time, and each one in succession reads out loud his or her answers to a series of 42 questions. The questions include inquiries about what news sources they follow, whether they’ve ever attended any Trump rallies or anti-Trump protests and whether they’ve ever supported the QAnon movement or antifa.

The form does not ask about party affiliation, political contributions or voting history, but the judge said answers to those questions “may easily be gleaned from the responses to other questions.” After the 42 questions are answered, prosecutors can ask the jurors a series of follow-up questions, and then Trump’s attorneys can ask their own follow-ups.

In court Monday, the judge told both sides the list of questions is “by far the most exhaustive questionnaire this court has ever used.”

“There will be no doubt how a prospective juror feels about Mr. Trump, the district attorney or the court” when the jurors are done answering, he added.

The trial will have an anonymous jury , meaning the jurors’ identities and addresses will not be made public. The judge said the move was necessary because of “a likelihood of bribery, jury tampering, or of physical injury or harassment of juror(s).”

While the trial is the first criminal trial involving a former president, it’s the fourth trial in New York involving Trump as a defendant since he left office. He was sued twice by writer E. Jean Carroll for sexual abuse and defamation and he and his company were accused of fraud in a civil case brought by New York Attorney General Letitia James. The verdicts against him in the three cases — all of which he is appealing — total about $550 million.

Adam Reiss is a reporter and producer for NBC and MSNBC.

Dareh Gregorian is a politics reporter for NBC News.

Lisa Rubin is an MSNBC legal correspondent and a former litigator.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Every search and arrest warrant application is governed by rules. The primary rule is found in the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: each warrant requires probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularity. More specific rules governing warrants are located within each jurisdictions' rules of criminal procedure.

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects people's right "to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures." Police must obtain a search warrant from a judge, although courts have identified exceptions to this rule, such as emergency situations and items plainly visible to police officers.

A warrant is a specialized legal document that is issued and signed by a judge. Warrants authorize the police to conduct searches, seizures, and arrests, depending on the type of warrant it is. A judge may only issue a warrant upon a showing of probable cause. Probable cause is the standard which courts apply to police requests for a warrant ...

A search warrant is a warrant signed by a judge or magistrate authorizing a law enforcement officer to conduct a search on a certain person, a specified place, or an automobile for criminal evidence. A search warrant usually is the prerequisite of a search, which is designed to protect individuals' reasonable expectation of privacy against unreasonable governmental physical trespass or other ...

A search warrant is an order signed by a judge that authorizes police officers to search for specific objects or materials at a definite location. For example, a warrant may authorize the search of "the single-dwelling premises at 11359 Happy Glade Avenue" and direct the police to search for and seize "cash, betting slips, record books, and every other means used in connection with placing ...

In law, search warrant is a written order by an official of a court. The warrant gives an authorization to an officer to search a person in a specified place for specified objects and to confiscate them if found. Under the criminal code, a search warrant can be sought according to the constitution of the particular state.

Search warrant is the form of legal documents that authorizes or allows the security officials or the police offers to enter any premises and perform the activity of searching the premises. Generally, a search warrant can be issued to search or seize any property or the person to search for: (1) evidence in case of crime; (2) an unlawfully ...

The Constitution's Fourth Amendment protects Americans " against unreasonable searches and seizures " and recognizes their right "to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects.". This language creates a general obligation for law enforcement personnel to obtain a warrant before searching you or your property.

1. Claim. What you want your readers to believe; the "point" you hope to persuade your reader of. 2. Evidence. What you will use to support the claim; your "proof"—often a direct or indirect quotation from a text, but sometimes a statistic or the like. 3. Warrant. A general principle that explains why you think your evidence is ...

Search Warrant Requirements and The Fourth Amendment. The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states the following: "The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath ...