Global Education in Context: Four Models, Four Lessons

- Share article

Editor’s Intro: As part of a National Geographic Society -funded research project, a team of researchers is documenting how school systems are approaching global learning. Laura Engel , associate professor of international education and international affairs, George Washington University; Heidi Gibson, research assistant, George Washington University ; and Kayla Gatalica, manager, Global Programs , District of Columbia public schools, share the lessons they have learned.

The need to build the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required for the 21 st -century globalized world is well-recognized by education policymakers, researchers, and practitioners. Yet too often, there is a lack of a coherent picture of what global education looks like in the United States. The decentralized nature of the U.S. education system means that in many districts and states global education is built from the ground up. Some laudable projects have aimed to share initiatives across states and to connect state leaders. One example is the States Network on International Education, created by the Asia Society and Longview Foundation, currently involving 25 member states committed to building capacity in global education. Interactive online tools like Mapping the Nation and Global Education Certificates allow researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to learn more about district- and state-level initiatives.

Four Models

To better understand global education in context, a team from George Washington University (GW) and the District of Columbia public schools (DCPS) made a series of virtual and in-person site visits to North Carolina, Virginia, and Illinois. During each of the site visits, our team had the opportunity to hear perspectives from global education leaders, teachers, administrators, students, organizations, and policymakers. We also developed an extended case study focused on the work of the DCPS Global Education team, providing a fourth context from which to better understand global education policy and practice.

Each of these four contexts reveals a different model of global education. In North Carolina, an example of a top-down approach, the state board of education adopted a framework for global learning and created a process to assess and recognize efforts by districts, schools, and educators. North Carolina’s extensive rubric for schools and districts awards “global-ready” designations and also allows schools and districts to see where they fall on a global-ready continuum ranging from “early” to “model.”

In Illinois, a group of Naperville Central High School teachers leveraged district support and successfully pushed for legislation establishing the Illinois Global Scholars Certificate . As part of this push, global-learning advocates across the state joined forces to build a statewide global education network.

Virginia’s initiatives are currently more localized, with individual districts championing globally-focused educational approaches, especially related to schools’ study abroad and exchange programs. Advocates have also leveraged state programs, such as the Governor’s World Language Academies, and new policies, like the Profile of a Graduate initiative, in support of a focus on developing students’ skills for a global future.

Lastly, within our team, we have perspectives on the robust global programming in DCPS, which reveals a multipronged approach to global education. The DCPS Global Education team manages districtwide programs like International Food Days and fully funded study abroad as well as school-specific programs such as world-language instruction and Global Studies Schools.

Four Lessons Learned

These four distinct cases provide insights into the diversity of global education practice within the United States. They also offer common lessons on how to make progress toward global education goals:

1) The Power of the Champion Behind every example of a successful global education program, policy, or practice were champions—often individuals with the power and capacity to leverage change—who sought to invest in global education for all schools and students. In each of the four contexts, this role varied. For example, in the case of Illinois, two highly respected teachers have spurred a grassroots statewide movement, whereas, in North Carolina, global education leadership came from a state-level champion, providing district supports such as resources and training.

2) Leveraging Partnerships Movements in global education in each of the four contexts had much to do with the leveraging of partnerships. These partnerships involved a range of different stakeholders, including the business community, fellow schools and districts, nonprofit organizations, and the higher education community. The function of partnerships varied as well. In the District of Columbia and Virginia, for instance, partners provided global education opportunities, such as working with local embassies to give students access to experiential learning. In North Carolina, partners helped facilitate teacher exchange by sourcing educators who brought global perspectives to the classroom.

3) Developing and Telling the Story Experienced global education advocates know that generating support for global-learning initiatives often involves pitching these programs to the right person at the right time in the right way. Policymakers who have had transformative international experiences, such as DCPS’ former Chancellor Kaya Henderson’s time spent studying abroad, are more likely to see the value of global education. Strategic use of existing policies, such as tying new global education initiatives to Virginia’s Portrait of a Graduate requirements, can help convince district leadership. In other cases, strategic thinking is needed about the best level of governance to leverage change. In Illinois, after considering a district-level approach, advocates realized they would get better traction at the state level. Building support requires a canny assessment of how to leverage existing policies and attitudes, as well as understanding how to best explain the importance of global education.

4) Building a Network In each of the four contexts, we learned the value of cohesive networks in creating opportunities and spaces for global education policy, practice, and programs. These are cross-curricular, as well as across geographical boundaries. In Virginia, international approaches have often been confined to world-language classrooms, but advocates are beginning to reach out to other curricular areas for a more interdisciplinary approach. District and state leaders frequently remarked on the power of sharing their approaches and practices with others. By building strong networks across the state, such as the one in Illinois, advocates were able to push for change.

Across the four contexts and our lessons learned, there is a clear value added when district and state leaders connect and share practices, policies, and research about global education in K-12 U.S. settings. To further develop such cross-cutting conversations, we launched the K12 Global Forum, which hosted an inaugural convening last year at the United States Institute of Peace in Washington, D.C. We look forward to future convenings to continue to share information and advice with each other.

Connect with the authors and Heather on Twitter.

Image created on Pablo .

The opinions expressed in Global Learning are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Major theories and models of learning

Several ideas and priorities, then, affect how we teachers think about learning, including the curriculum, the difference between teaching and learning, sequencing, readiness, and transfer. The ideas form a “screen” through which to understand and evaluate whatever psychology has to offer education. As it turns out, many theories, concepts, and ideas from educational psychology do make it through the “screen” of education, meaning that they are consistent with the professional priorities of teachers and helpful in solving important problems of classroom teaching. In the case of issues about classroom learning, for example, educational psychologists have developed a number of theories and concepts that are relevant to classrooms, in that they describe at least some of what usually happens there and offer guidance for assisting learning. It is helpful to group the theories according to whether they focus on changes in behavior or in thinking. The distinction is rough and inexact, but a good place to begin. For starters, therefore, consider two perspectives about learning, called behaviorism (learning as changes in overt behavior) and constructivism, (learning as changes in thinking). The second category can be further divided into psychological constructivism (changes in thinking resulting from individual experiences), and social constructivism, (changes in thinking due to assistance from others). The rest of this chapter describes key ideas from each of these viewpoints. As I hope you will see, each describes some aspects of learning not just in general, but as it happens in classrooms in particular. So each perspective suggests things that you might do in your classroom to make students’ learning more productive.

Behaviorism: changes in what students do

Behaviorism is a perspective on learning that focuses on changes in individuals’ observable behaviors— changes in what people say or do. At some point we all use this perspective, whether we call it “behaviorism” or something else. The first time that I drove a car, for example, I was concerned primarily with whether I could actually do the driving, not with whether I could describe or explain how to drive. For another example: when I reached the point in life where I began cooking meals for myself, I was more focused on whether I could actually produce edible food in a kitchen than with whether I could explain my recipes and cooking procedures to others. And still another example—one often relevant to new teachers: when I began my first year of teaching, I was more focused on doing the job of teaching—on day-to-day survival—than on pausing to reflect on what I was doing.

Note that in all of these examples, focusing attention on behavior instead of on “thoughts” may have been desirable at that moment, but not necessarily desirable indefinitely or all of the time. Even as a beginner, there are times when it is more important to be able to describe how to drive or to cook than to actually do these things. And there definitely are many times when reflecting on and thinking about teaching can improve teaching itself. (As a teacher-friend once said to me: “Don’t just do something; stand there!”) But neither is focusing on behavior which is not necessarily less desirable than focusing on students’ “inner” changes, such as gains in their knowledge or their personal attitudes. If you are teaching, you will need to attend to all forms of learning in students, whether inner or outward.

In classrooms, behaviorism is most useful for identifying relationships between specific actions by a student and the immediate precursors and consequences of the actions. It is less useful for understanding changes in students’ thinking; for this purpose we need theories that are more cognitive (or thinking-oriented) or social, like the ones described later in this chapter. This fact is not a criticism of behaviorism as a perspective, but just a clarification of its particular strength or usefulness, which is to highlight observable relationships among actions, precursors and consequences. Behaviorists use particular terms (or “lingo,” some might say) for these relationships. One variety of behaviorism that has proved especially useful to educators is operant conditioning, described in the next section.

Operant conditioning: new behaviors because of new consequences

Operant conditioning focuses on how the consequences of a behavior affect the behavior over time. It begins with the idea that certain consequences tend to make certain behaviors happen more frequently. If I compliment a student for a good comment made during discussion, there is more of a chance that I will hear further comments from the student in the future (and hopefully they too will be good ones!). If a student tells a joke to classmates and they laugh at it, then the student is likely to tell more jokes in the future and so on.

The original research about this model of learning was not done with people, but with animals. One of the pioneers in the field was a Harvard professor named B. F. Skinner, who published numerous books and articles about the details of the process and who pointed out many parallels between operant conditioning in animals and operant conditioning in humans (1938, 1948, 1988). Skinner observed the behavior of rather tame laboratory rats (not the unpleasant kind that sometimes live in garbage dumps). He or his assistants would put them in a cage that contained little except a lever and a small tray just big enough to hold a small amount of food. (Figure 1 shows the basic set-up, which is sometimes nicknamed a “Skinner box.”) At first the rat would sniff and “putter around” the cage at random, but sooner or later it would happen upon the lever and eventually happen to press it. Presto! The lever released a small pellet of food, which the rat would promptly eat. Gradually the rat would spend more time near the lever and press the lever more frequently, getting food more frequently. Eventually it would spend most of its time at the lever and eating its fill of food. The rat had “discovered” that the consequence of pressing the level was to receive food. Skinner called the changes in the rat’s behavior an example of operant conditioning , and gave special names to the different parts of the process. He called the food pellets the reinforcement and the lever-pressing the operant (because it “operated” on the rat’s environment). See below.

Figure 1: Operant conditioning with a laboratory rat

Skinner and other behavioral psychologists experimented with using various reinforcers and operants. They also experimented with various patterns of reinforcement (or schedules of reinforcement ), as well as with various cues or signals to the animal about when reinforcement was available. It turned out that all of these factors—the operant, the reinforcement, the schedule, and the cues—affected how easily and thoroughly operant conditioning occurred. For example, reinforcement was more effective if it came immediately after the crucial operant behavior, rather than being delayed, and reinforcements that happened intermittently (only part of the time) caused learning to take longer, but also caused it to last longer.

Operant conditioning and students’ learning: Since the original research about operant conditioning used animals, it is important to ask whether operant conditioning also describes learning in human beings, and especially in students in classrooms. On this point the answer seems to be clearly “yes.” There are countless classroom examples of consequences affecting students’ behavior in ways that resemble operant conditioning, although the process certainly does not account for all forms of student learning (Alberto & Troutman, 2005). Consider the following examples. In most of them the operant behavior tends to become more frequent on repeated occasions:

- A seventh-grade boy makes a silly face (the operant) at the girl sitting next to him. Classmates sitting around them giggle in response (the reinforcement).

- A kindergarten child raises her hand in response to the teacher’s question about a story (the operant). The teacher calls on her and she makes her comment (the reinforcement).

- Another kindergarten child blurts out her comment without being called on (the operant). The teacher frowns, ignores this behavior, but before the teacher calls on a different student, classmates are listening attentively (the reinforcement) to the student even though he did not raise his hand as he should have.

- A twelfth-grade student—a member of the track team—runs one mile during practice (the operant). He notes the time it takes him as well as his increase in speed since joining the team (the reinforcement).

- A child who is usually very restless sits for five minutes doing an assignment (the operant). The teaching assistant compliments him for working hard (the reinforcement).

- A sixth-grader takes home a book from the classroom library to read overnight (the operant). When she returns the book the next morning, her teacher puts a gold star by her name on a chart posted in the room (the reinforcement).

These examples are enough to make several points about operant conditioning. First, the process is widespread in classrooms—probably more widespread than teachers realize. This fact makes sense, given the nature of public education: to a large extent, teaching is about making certain consequences (like praise or marks) depend on students’ engaging in certain activities (like reading certain material or doing assignments). Second, learning by operant conditioning is not confined to any particular grade, subject area, or style of teaching, but by nature happens in every imaginable classroom. Third, teachers are not the only persons controlling reinforcements. Sometimes they are controlled by the activity itself (as in the track team example), or by classmates (as in the “giggling” example). This leads to the fourth point: that multiple examples of operant conditioning often happen at the same time. A case study in Appendix A of this book ( The decline and fall of Jane Gladstone ) suggests how this happened to someone completing student teaching.

Because operant conditioning happens so widely, its effects on motivation are a bit complex. Operant conditioning can encourage intrinsic motivation , to the extent that the reinforcement for an activity is the activity itself. When a student reads a book for the sheer enjoyment of reading, for example, he is reinforced by the reading itself, and we we can say that his reading is “intrinsically motivated.” More often, however, operant conditioning stimulates both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation at the same time. The combining of both is noticeable in the examples in the previous paragraph. In each example, it is reasonable to assume that the student felt intrinsically motivated to some partial extent, even when reward came from outside the student as well. This was because part of what reinforced their behavior was the behavior itself—whether it was making faces, running a mile, or contributing to a discussion. At the same time, though, note that each student probably was also extrinsically motivated , meaning that another part of the reinforcement came from consequences or experiences not inherently part of the activity or behavior itself. The boy who made a face was reinforced not only by the pleasure of making a face, for example, but also by the giggles of classmates. The track student was reinforced not only by the pleasure of running itself, but also by knowledge of his improved times and speeds. Even the usually restless child sitting still for five minutes may have been reinforced partly by this brief experience of unusually focused activity, even if he was also reinforced by the teacher aide’s compliment. Note that the extrinsic part of the reinforcement may sometimes be more easily observed or noticed than the intrinsic part, which by definition may sometimes only be experienced within the individual and not also displayed outwardly. This latter fact may contribute to an impression that sometimes occurs, that operant conditioning is really just “bribery in disguise,” that only the external reinforcements operate on students’ behavior. It is true that external reinforcement may sometimes alter the nature or strength of internal (or intrinsic) reinforcement, but this is not the same as saying that it destroys or replaces intrinsic reinforcement. But more about this issue later!

Key concepts about operant conditioning: Operant conditioning is made more complicated, but also more realistic, by several additional ideas. They can be confusing because the ideas have names that sound rather ordinary, but that have special meanings with the framework of operant theory. Among the most important concepts to understand are the following:

- generalization

- discrimination

- schedules of reinforcement

The paragraphs below explain each of these briefly, as well as their relevance to classroom teaching and learning.

Extinction refers to the disappearance of an operant behavior because of lack of reinforcement. A student who stops receiving gold stars or compliments for prolific reading of library books, for example, may extinguish (i.e. decrease or stop) book-reading behavior. A student who used to be reinforced for acting like a clown in class may stop clowning once classmates stop paying attention to the antics.

Generalization refers to the incidental conditioning of behaviors similar to an original operant . If a student gets gold stars for reading library books, then we may find her reading more of other material as well—newspapers, comics, etc.–even if the activity is not reinforced directly. The “spread” of the new behavior to similar behaviors is called generalization. Generalization is a lot like the concept of transfer discussed early in this chapter, in that it is about extending prior learning to new situations or contexts. From the perspective of operant conditioning, though, what is being extended (or “transferred” or generalized) is a behavior, not knowledge or skill.

Discrimination means learning not to generalize. In operant conditioning, what is not overgeneralized (i.e. what is discriminated) is the operant behavior. If I am a student who is being complimented (reinforced) for contributing to discussions, I must also learn to discriminate when to make verbal contributions from when not to make them—such as when classmates or the teacher are busy with other tasks. Discrimination learning usually results from the combined effects of reinforcement of the target behavior and extinction of similar generalized behaviors. In a classroom, for example, a teacher might praise a student for speaking during discussion, but ignore him for making very similar remarks out of turn. In operant conditioning, the schedule of reinforcement refers to the pattern or frequency by which reinforcement is linked with the operant. If a teacher praises me for my work, does she do it every time, or only sometimes? Frequently or only once in awhile? In respondent conditioning, however, the schedule in question is the pattern by which the conditioned stimulus is paired with the unconditioned stimulus. If I am student with Mr Horrible as my teacher, does he scowl every time he is in the classroom, or only sometimes? Frequently or rarely?

Behavioral psychologists have studied schedules of reinforcement extensively (for example, Ferster, et al., 1997; Mazur, 2005), and found a number of interesting effects of different schedules. For teachers, however, the most important finding may be this: partial or intermittent schedules of reinforcement generally cause learning to take longer, but also cause extinction of learning to take longer. This dual principle is important for teachers because so much of the reinforcement we give is partial or intermittent. Typically, if I am teaching, I can compliment a student a lot of the time, for example, but there will inevitably be occasions when I cannot do so because I am busy elsewhere in the classroom. For teachers concerned both about motivating students and about minimizing inappropriate behaviors, this is both good news and bad. The good news is that the benefits of my praising students’ constructive behavior will be more lasting, because they will not extinguish their constructive behaviors immediately if I fail to support them every single time they happen. The bad news is that students’ negative behaviors may take longer to extinguish as well, because those too may have developed through partial reinforcement. A student who clowns around inappropriately in class, for example, may not be “supported” by classmates’ laughter every time it happens, but only some of the time. Once the inappropriate behavior is learned, though, it will take somewhat longer to disappear even if everyone—both teacher and classmates—make a concerted effort to ignore (or extinguish) it.

Finally, behavioral psychologists have studied the effects of cues . In operant conditioning, a cue is a stimulus that happens just prior to the operant behavior and that signals that performing the behavior may lead to reinforcement. In the original conditioning experiments, Skinner’s rats were sometimes cued by the presence or absence of a small electric light in their cage. Reinforcement was associated with pressing a lever when, and only when, the light was on. In classrooms, cues are sometimes provided by the teacher deliberately, and sometimes simply by the established routines of the class. Calling on a student to speak, for example, can be a cue that if the student does say something at that moment, then he or she may be reinforced with praise or acknowledgment. But if that cue does not occur—if the student is not called on—speaking may not be rewarded. In more everyday, non-behaviorist terms, the cue allows the student to learn when it is acceptable to speak, and when it is not.

Constructivism: changes in how students think

Behaviorist models of learning may be helpful in understanding and influencing what students do, but teachers usually also want to know what students are thinking , and how to enrich what students are thinking. For this goal of teaching, some of the best help comes from constructivism , which is a perspective on learning focused on how students actively create (or “construct”) knowledge out of experiences. Constructivist models of learning differ about how much a learner constructs knowledge independently, compared to how much he or she takes cues from people who may be more of an expert and who help the learner’s efforts (Fosnot, 2005; Rockmore, 2005). For convenience these are called psychological constructivism and social constructivism (or sometimes sociocultural theory ). As explained in the next section, both focus on individuals’ thinking rather than their behavior, but they have distinctly different implications for teaching.

Psychological constructivism: the independent investigator

The main idea of psychological constructivism is that a person learns by mentally organizing and reorganizing new information or experiences. The organization happens partly by relating new experiences to prior knowledge that is already meaningful and well understood. Stated in this general form, individual constructivism is sometimes associated with a well-known educational philosopher of the early twentieth century, John Dewey (1938–1998). Although Dewey himself did not use the term constructivism in most of his writing, his point of view amounted to a type of constructivism, and he discussed in detail its implications for educators. He argued, for example, that if students indeed learn primarily by building their own knowledge, then teachers should adjust the curriculum to fit students’ prior knowledge and interests as fully as possible. He also argued that a curriculum could only be justified if it related as fully as possible to the activities and responsibilities that students will probably have later , after leaving school. To many educators these days, his ideas may seem merely like good common sense, but they were indeed innovative and progressive at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Another recent example of psychological constructivism is the cognitive theory of Jean Piaget (Piaget, 2001; Gruber & Voneche, 1995). Piaget described learning as interplay between two mental activities that he called assimilation and accommodation . Assimilation is the interpretation of new information in terms of pre-existing concepts, information or ideas. A preschool child who already understands the concept of bird , for example, might initially label any flying object with this term—even butterflies or mosquitoes. Assimilation is therefore a bit like the idea of generalization in operant conditioning, or the idea of transfer described at the beginning of this chapter. In Piaget’s viewpoint, though, what is being transferred to a new setting is not simply a behavior (Skinner’s “operant” in operant conditioning), but a mental representation for an object or experience.

Assimilation operates jointly with accommodation , which is the revision or modification of pre-existing concepts in terms of new information or experience. The preschooler who initially generalizes the concept of bird to include any flying object, for example, eventually revises the concept to include only particular kinds of flying objects, such as robins and sparrows, and not others, like mosquitoes or airplanes. For Piaget, assimilation and accommodation work together to enrich a child’s thinking and to create what Piaget called cognitive equilibrium , which is a balance between reliance on prior information and openness to new information. At any given time, cognitive equilibrium consists of an ever-growing repertoire of mental representations for objects and experiences. Piaget called each mental representation a schema (all of them together—the plural—were called schemata ). A schema was not merely a concept, but an elaborated mixture of vocabulary, actions, and experience related to the concept. A child’s schema for bird , for example, includes not only the relevant verbal knowledge (like knowing how to define the word “bird”), but also the child’s experiences with birds, pictures of birds, and conversations about birds. As assimilation and accommodation about birds and other flying objects operate together over time, the child does not just revise and add to his vocabulary (such as acquiring a new word, “butterfly”), but also adds and remembers relevant new experiences and actions. From these collective revisions and additions the child gradually constructs whole new schemata about birds, butterflies, and other flying objects. In more everyday (but also less precise) terms, Piaget might then say that “the child has learned more about birds.”

Exhibit 1 diagrams the relationships among the Piagetian version of psychological constructivist learning. Note that the model of learning in the Exhibit is rather “individualistic,” in the sense that it does not say much about how other people involved with the learner might assist in assimilating or accommodating information. Parents and teachers, it would seem, are left lingering on the sidelines, with few significant responsibilities for helping learners to construct knowledge. But the Piagetian picture does nonetheless imply a role for helpful others: someone, after all, has to tell or model the vocabulary needed to talk about and compare birds from airplanes and butterflies! Piaget did recognize the importance of helpful others in his writings and theorizing, calling the process of support or assistance social transmission . But he did not emphasize this aspect of constructivism. Piaget was more interested in what children and youth could figure out on their own, so to speak, than in how teachers or parents might be able to help the young figure out (Salkind, 2004). Partly for this reason, his theory is often considered less about learning and more about development , or long-term change in a person resulting from multiple experiences that may not be planned deliberately. For the same reason, educators have often found Piaget’s ideas especially helpful for thinking about students’ readiness to learn, another one of the lasting educational issues discussed at the beginning of this chapter. We will therefore return to Piaget later to discuss development and its importance for teaching in more detail

Exhibit 1: Learning According to Piaget

Assimilation + Accommodation → Equilibrium → Schemata

Social Constructivism: assisted performance

Unlike Piaget’s orientation to individuals’ thinking in his version of constructivism, some psychologists and educators have explicitly focused on the relationships and interactions between a learner and other individuals who are more knowledgeable or experienced. This framework often is called social constructivism or sociocultural theory . An early expression of this viewpoint came from the American psychologist Jerome Bruner (1960, 1966, 1996), who became convinced that students could usually learn more than had been traditionally expected as long as they were given appropriate guidance and resources. He called such support instructional scaffolding —literally meaning a temporary framework like the ones used to construct buildings and that allow a much stronger structure to be built within it. In a comment that has been quoted widely (and sometimes disputed), Bruner wrote: “We [constructivist educators] begin with the hypothesis that any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development.” (1960, p. 33). The reason for such a bold assertion was Bruner’s belief in scaffolding—his belief in the importance of providing guidance in the right way and at the right time. When scaffolding is provided, students seem more competent and “intelligent,” and they learn more.

Similar ideas were independently proposed by the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1978), whose writing focused on how a child’s or novice’s thinking is influenced by relationships with others who are more capable, knowledgeable, or expert than the learner. Vygotsky made the reasonable proposal that when a child (or novice) is learning a new skill or solving a new problem, he or she can perform better if accompanied and helped by an expert than if performing alone—though still not as well as the expert. Someone who has played very little chess, for example, will probably compete against an opponent better if helped by an expert chess player than if competing against the opponent alone. Vygotsky called the difference between solo performance and assisted performance the zone of proximal development (or ZPD for short)—meaning, figuratively speaking, the place or area of immediate change. From this social constructivist perspective, learning is like assisted performance (Tharp & Gallimore, 1991). During learning, knowledge or skill is found initially “in” the expert helper. If the expert is skilled and motivated to help, then the expert arranges experiences that let the novice to practice crucial skills or to construct new knowledge. In this regard the expert is a bit like the coach of an athlete—offering help and suggesting ways of practicing, but never doing the actual athletic work himself or herself. Gradually, by providing continued experiences matched to the novice learner’s emerging competencies, the expert-coach makes it possible for the novice or apprentice to appropriate (or make his or her own) the skills or knowledge that originally resided only with the expert. These relationships are diagrammed in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: Learning According to Vygotsky

Novice → Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) ← Expert

In both the psychological and social versions of constructivist learning, the novice is not really “taught” so much as simply allowed to learn. But compared to psychological constructivism, social constructivism highlights a more direct responsibility of the expert for making learning possible. He or she must not only have knowledge and skill, but also know how to arrange experiences that make it easy and safe for learners to gain knowledge and skill themselves. These requirements sound, of course, a lot like the requirements for classroom teaching. In addition to knowing what is to be learned, the expert (i.e. the teacher) also has to organize the content into manageable parts, offer the parts in a sensible sequence, provide for suitable and successful practice, bring the parts back together again at the end, and somehow relate the entire experience to knowledge and skills meaningful to the learner already. But of course, no one said that teaching is easy!

The teacher’s role in Psychological and Social Constructivism

As some of the comments above indicate, psychological and social constructivism have differences that suggest different ways for teachers to teach most effectively. The theoretical differences are related to three ideas in particular: the relationship of learning and long-term development, the role or meaning of generalizations and abstractions during development, and the mechanism by which development occurs.

The relationship of learning and long-term development of the child

In general psychological constructivism such as Piaget emphasize the ways that long-term development determines a child’s ability to learn, rather than the other way around. The earliest stages of a child’s life are thought to be rather self-centered and to be dependent on the child’s sensory and motor interactions with the environment. When acting or reacting to his or her surroundings, the child has relatively little language skill initially. This circumstance limits the child’s ability to learn in the usual, school-like sense of the term. As development proceeds, of course, language skills improve and hence the child becomes progressively more “teachable” and in this sense more able to learn. But whatever the child’s age, ability to learn waits or depends upon the child’s stage of development. From this point of view, therefore, a primary responsibility of teachers is to provide a very rich classroom environment, so that children can interact with it independently and gradually make themselves ready for verbal learning that is increasingly sophisticated.

Social constructivists such as Vygotsky, on the other hand, emphasize the importance of social interaction in stimulating the development of the child. Language and dialogue therefore are primary, and development is seen as happening as a result—the converse of the sequence pictured by Piaget. Obviously a child does not begin life with a lot of initial language skill, but this fact is why interactions need to be scaffolded with more experienced experts— people capable of creating a zone of proximal development in their conversations and other interactions. In the preschool years the experts are usually parents; after the school years begin, the experts broaden to include teachers. A teacher’s primary responsibility is therefore to provide very rich opportunities for dialogue, both among children and between individual children and the teacher.

The role of generalizations and abstractions during development

Consistent with the ideas above, psychological constructivism tends to see a relatively limited role for abstract or hypothetical reasoning in the life of children—and even in the reasoning of youth and many adults. Such reasoning is regarded as an outgrowth of years of interacting with the environment very concretely. As explained more fully in the next chapter (“Student development”), elementary-age students can reason, but they are thought to reason only about immediate, concrete objects and events. Even older youth are thought to reason in this way much, or even all of the time. From this perspective a teacher should limit the amount of thinking about abstract ideas that she expects from students. The idea of “democracy,” for example, may be experienced simply as an empty concept. At most it might be misconstrued as an oversimplified, overly concrete idea—as “just” about taking votes in class, for instance. Abstract thinking is possible, according to psychological constructivism, but it emerges relatively slowly and relatively late in development, after a person accumulates considerable concrete experience.

Social constructivism sees abstract thinking emerging from dialogue between a relative novice (a child or youth) and a more experienced expert (a parent or teacher). From this point of view, the more such dialogue occurs, then the more the child can acquire facility with it. The dialogue must, of course, honor a child’s need for intellectual scaffolding or a zone of proximal development. A teacher’s responsibility can therefore include engaging the child in dialogue that uses potentially abstract reasoning, but without expecting the child to understand the abstractions fully at first. Young children, for example, can not only engage in science experiments like creating a “volcano” out of baking soda and water, but also discuss and speculate about their observations of the experiment. They may not understand the experiment as an adult would, but the discussion can begin moving them toward adult-like understandings.

How development occurs

In psychological constructivism, as explained earlier, development is thought to happen because of the interplay between assimilation and accommodation —between when a child or youth can already understand or conceive of, and the change required of that understanding by new experiences. Acting together, assimilation and accommodation continually create new states of cognitive equilibrium . A teacher can therefore stimulate development by provoking cognitive dissonance deliberately: by confronting a student with sights, actions, or ideas that do not fit with the student’s existing experiences and ideas. In practice the dissonance is often communicated verbally, by posing questions or ideas that are new or that students may have misunderstood in the past. But it can also be provoked through pictures or activities that are unfamiliar to students—by engaging students in a community service project, for example, that brings them in contact with people who they had previously considered “strange” or different from themselves.

In social constructivism, as also explained earlier, development is thought to happen largely because of scaffolded dialogue in a zone of proximal development. Such dialogue is by implication less like “disturbing” students’ thinking than like “stretching” it beyond its former limits. The image of the teacher therefore is more one of collaborating with students’ ideas rather than challenging their ideas or experiences. In practice, however, the actual behavior of teachers and students may be quite similar in both forms of constructivism. Any significant new learning requires setting aside, giving up, or revising former learning, and this step inevitably therefore “disturbs” thinking, if only in the short term and only in a relatively minor way.

Implications of constructivism for teaching

Whether you think of yourself as a psychological constructivist or a social constructivist, there are strategies for helping students help in develop their thinking—in fact the strategies constitute a major portion of this book, and are a major theme throughout the entire preservice teacher education programs. For now, look briefly at just two. One strategy that teachers often find helpful is to organize the content to be learned as systematically as possible, because doing this allows the teacher to select and devise learning activities that are better tailored to students’ cognitive abilities, or that promote better dialogue, or both. One of the most widely used frameworks for organizing content, for example, is a classification scheme proposed by the educator Benjamin Bloom, published with the somewhat imposing title of Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook #1: Cognitive Domain (Bloom, et al., 1956; Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). Bloom’s taxonomy , as it is usually called, describes six kinds of learning goals that teachers can in principle expect from students, ranging from simple recall of knowledge to complex evaluation of knowledge. (The levels are defined briefly in Error: Reference source not found with examples from Goldilocks and the Three Bears.)

Bloom’s taxonomy makes useful distinctions among possible kinds of knowledge needed by students, and therefore potentially helps in selecting activities that truly target students’ zones of proximal development in the sense meant by Vygotsky. A student who knows few terms for the species studied in biology unit (a problem at Bloom’s knowledge and comprehension levels), for example, may initially need support at remembering and defining the terms before he or she can make useful comparisons among species (Bloom’s analysis level). Pinpointing the most appropriate learning activities to accomplish this objective remains the job of the teacher-expert (that’s you), but the learning itself has to be accomplished by the student. Put in more social constructivist terms, the teacher arranges a zone of proximal development that allows the student to compare species successfully, but the student still has to construct or appropriate the comparisons for him or herself.

A second strategy may be coupled with the first. As students gain experience as students, they become able to think about how they themselves learn best, and you (as the teacher) can encourage such self-reflection as one of your goals for their learning. These changes allow you to transfer some of your responsibilities for arranging learning to the students themselves. For the biology student mentioned above, for example, you may be able not only to plan activities that support comparing species, but also to devise ways for the student to think about how he or she might learn the same information independently. The resulting self-assessment and self-direction of learning often goes by the name of metacognition —an ability to think about and regulate one’s own thinking (Israel, 2005). Metacognition can sometimes be difficult for students to achieve, but it is an important goal for social constructivist learning because it gradually frees learners from dependence on expert teachers to guide their learning. Reflective learners, you might say, become their own expert guides. Like with using Bloom’s taxonomy, though, promoting metacognition and self-directed learning is important enough that I will come back to it later in more detail (in the chapter on “Facilitating complex thinking”).

By assigning a more active role to expert helpers—which by implication includes teachers—than does the psychological constructivism, social constructivism may be more complete as a description of what teachers usually do when actually busy in classrooms, and of what they usually hope students will experience there. As we will see in the next chapter, however, there are more uses for a theory than its description of moment-to-moment interactions between teacher and students. As explained there, some theories can be helpful for planning instruction rather than for doing it. It turns out that this is the case for psychological constructivism, which offers important ideas about the appropriate sequencing of learning and development. This fact makes the psychological constructivism valuable in its own way, even though it (and a few other learning theories as well) may seem to omit mentioning teachers, parents, or experts in detail. So do not make up your mind about the relative merits of different learning theories yet!

Alberto, P. & Troutman, A. (2005). Applied behavior analysis for teachers, 7th edition . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Anderson, L. & Krathwohl, D. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . New York: Longman.

Bruner, J. (1960). The process of education . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dewey, J. (1938/1998). How we think . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Ferster, C., Skinner, B. F., Cheney, C., Morse, W., & Dews, D. Schedules of reinforcement . New York: Copley Publishing Group.

Fosnot, C. (Ed.). (2005). Constructivism: Theory, perspectives, and practice, 2nd edition . New York: Teachers College Press.

Gruber, H. & Voneche, J. (Eds.). (1995). The essential Piaget. New York: Basic Books.

Israel, S. (Ed.). (2005). Metacognition in literacy learning. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Mazur, J. (2005). Learning and behavior, 6th edition . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Piaget, J. (2001). The psychology of intelligence . London, UK: Routledge.

Rockmore, T. (2005). On constructivist epistemology . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Salkind, N. (2004). An introduction to theories of human development . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Walden Two . New York: Macmillan.

Skinner, B. F. (1988). The selection of behavior: The operant behaviorism of B. F. Skinner . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tharp, R. & Gallimore, R. (1991). Rousing minds to life: Teaching, learning, and schooling in social context . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Privacy Policy

What the best education systems are doing right

Share this idea.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

In South Korea and Finland, it’s not about finding the “right” school.

Fifty years ago, both South Korea and Finland had terrible education systems. Finland was at risk of becoming the economic stepchild of Europe. South Korea was ravaged by civil war. Yet over the past half century, both South Korea and Finland have turned their schools around — and now both countries are hailed internationally for their extremely high educational outcomes. What can other countries learn from these two successful, but diametrically opposed, educational models? Here’s an overview of what South Korea and Finland are doing right.

The Korean model: Grit and hard, hard, hard work.

For millennia, in some parts of Asia, the only way to climb the socioeconomic ladder and find secure work was to take an examination — in which the proctor was a proxy for the emperor , says Marc Tucker, president and CEO of the National Center on Education and the Economy. Those examinations required a thorough command of knowledge, and taking them was a grueling rite of passage. Today, many in the Confucian countries still respect the kind of educational achievement that is promoted by an exam culture.

The Koreans have achieved a remarkable feat: the country is 100 percent literate. But success comes with a price.

Among these countries, South Korea stands apart as the most extreme, and arguably, most successful. The Koreans have achieved a remarkable feat: the country is 100 percent literate, and at the forefront of international comparative tests of achievement, including tests of critical thinking and analysis. But this success comes with a price: Students are under enormous, unrelenting pressure to perform. Talent is not a consideration — because the culture believes in hard work and diligence above all, there is no excuse for failure. Children study year-round, both in-school and with tutors. If you study hard enough, you can be smart enough.

“Koreans basically believe that I have to get through this really tough period to have a great future,” says Andreas Schleicher , director of education and skills at PISA and special advisor on education policy at the OECD. “It’s a question of short-term unhappiness and long-term happiness.” It’s not just the parents pressuring their kids. Because this culture traditionally celebrates conformity and order, pressure from other students can also heighten performance expectations. This community attitude expresses itself even in early-childhood education, says Joe Tobin, professor of early childhood education at the University of Georgia who specializes in comparative international research. In Korea, as in other Asian countries, class sizes are very large — which would be extremely undesirable for, say, an American parent. But in Korea, the goal is for the teacher to lead the class as a community, and for peer relationships to develop. In American preschools, the focus for teachers is on developing individual relationships with students, and intervening regularly in peer relationships.

“I think it is clear there are better and worse way to educate our children,” says Amanda Ripley, author of The Smartest Kids in the World: And How They Got That Way . “At the same time, if I had to choose between an average US education and an average Korean education for my own kid, I would choose, very reluctantly, the Korean model. The reality is, in the modern world the kid is going to have to know how to learn, how to work hard and how to persist after failure. The Korean model teaches that.”

The Finnish model: Extracurricular choice, intrinsic motivation.

In Finland, on the other hand, students are learning the benefits of both rigor and flexibility. The Finnish model, say educators, is utopia.

Finland has a short school day rich with school-sponsored extracurriculars, because Finns believe important learning happens outside the classroom.

In Finland, school is the center of the community, notes Schleicher. School provides not just educational services, but social services. Education is about creating identity.

Finnish culture values intrinsic motivation and the pursuit of personal interest. It has a relatively short school day rich with school-sponsored extracurriculars, because culturally, Finns believe important learning happens outside of the classroom. (An exception? Sports, which are not sponsored by schools, but by towns.) A third of the classes that students take in high school are electives, and they can even choose which matriculation exams they are going to take. It’s a low-stress culture, and it values a wide variety of learning experiences.

But that does not except it from academic rigor, motivated by the country’s history trapped between European superpowers, says Pasi Sahlberg, Finnish educator and author of Finnish Lessons: What the World Can Learn From Educational Change in Finland .

Teachers in Finland teach 600 hours a year, spending the rest of time in professional development. In the U.S., teachers are in the classroom 1,100 hours a year, with little time for feedback.

“A key to that is education. Finns do not really exist outside of Finland,” says Sahlberg. “This drives people to take education more seriously. For example, nobody speaks this funny language that we do. Finland is bilingual, and every student learns both Finnish and Swedish. And every Finn who wants to be successful has to master at least one other language, often English, but she also typically learns German, French, Russian and many others. Even the smallest children understand that nobody else speaks Finnish, and if they want to do anything else in life, they need to learn languages.”

Finns share one thing with South Koreans: a deep respect for teachers and their academic accomplishments. In Finland, only one in ten applicants to teaching programs is admitted. After a mass closure of 80 percent of teacher colleges in the 1970s, only the best university training programs remained, elevating the status of educators in the country. Teachers in Finland teach 600 hours a year, spending the rest of time in professional development, meeting with colleagues, students and families. In the U.S., teachers are in the classroom 1,100 hours a year, with little time for collaboration, feedback or professional development.

How Americans can change education culture

As TED speaker Sir Ken Robinson noted in his 2013 talk ( How to escape education’s death valley ), when it comes to current American education woes “the dropout crisis is just the tip of an iceberg. What it doesn’t count are all the kids who are in school but being disengaged from it, who don’t enjoy it, who don’t get any real benefit from it.” But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Notes Amanda Ripley, “culture is a thing that changes. It’s more malleable than we think. Culture is like this ether that has all kinds of things swirling around in it, some of which are activated and some of which are latent. Given an economic imperative or change in leadership or accident of history, those things get activated.” The good news is, “We Americans have a lot of things in our culture which would support a very strong education system, such as a longstanding rhetoric about the equality of opportunity and a strong and legitimate meritocracy,” says Ripley.

One reason we haven’t made much progress academically over the past 50 years is because it hasn’t been economically crucial for American kids to master sophisticated problem-solving and critical-thinking skills in order to survive. But that’s not true anymore. “There’s a lag for cultures to catch up with economic realities, and right now we’re living in that lag,” says Ripley. “So our kids aren’t growing up with the kind of skills or grit to make it in the global economy.”

“We are prisoners of the pictures and experiences of education that we had,” says Tony Wagner , expert-in-residence at Harvard’s educational innovation center and author of The Global Achievement Gap . “We want schools for our kids that mirror our own experience, or what we thought we wanted. That severely limits our ability to think creatively of a different kind of education. But there’s no way that tweaking that assembly line will meet the 21st-century world. We need a major overhaul.”

Indeed. Today, the American culture of choice puts the onus on parents to find the “right” schools for our kids, rather than trusting that all schools are capable of preparing our children for adulthood. Our obsession with talent puts the onus on students to be “smart,” rather than on adults’ ability to teach them. And our antiquated system for funding schools makes property values the arbiter of spending per student, not actual values.

But what will American education culture look like tomorrow? In the most successful education cultures in the world, it is the system that is responsible for the success of the student, says Schleicher — not solely the parent, not solely the student, not solely the teacher. The culture creates the system. The hope is that Americans can find the grit and will to change their own culture — one parent, student and teacher at a time.

Featured image via iStock.

About the author

Amy S. Choi is a freelance journalist, writer and editor based in Brooklyn, N.Y. She is the co-founder and editorial director of The Mash-Up Americans, a media and consulting company that examines multidimensional modern life in the U.S.

- Amy S. Choi

- Editor's picks

- questions worth asking

- South Korea

- What makes a good education?

TED Talk of the Day

How to make radical climate action the new normal

6 ways to give that aren't about money

A smart way to handle anxiety -- courtesy of soccer great Lionel Messi

How do top athletes get into the zone by getting uncomfortable.

6 things people do around the world to slow down

Creating a contract -- yes, a contract! -- could help you get what you want from your relationship

Could your life story use an update? Here’s how to do it

6 tips to help you be a better human now

How to have better conversations on social media (really!)

3 strategies for effective leadership, from a former astronaut

Can trees heal people?

5 things scientists now know about COVID-19 -- and 5 they're still figuring out

Required reading: The books that students read in 28 countries around the world

What is the ideal age to retire? Never, according to a neuroscientist

What will education look like in 20 years? Here are 4 scenarios

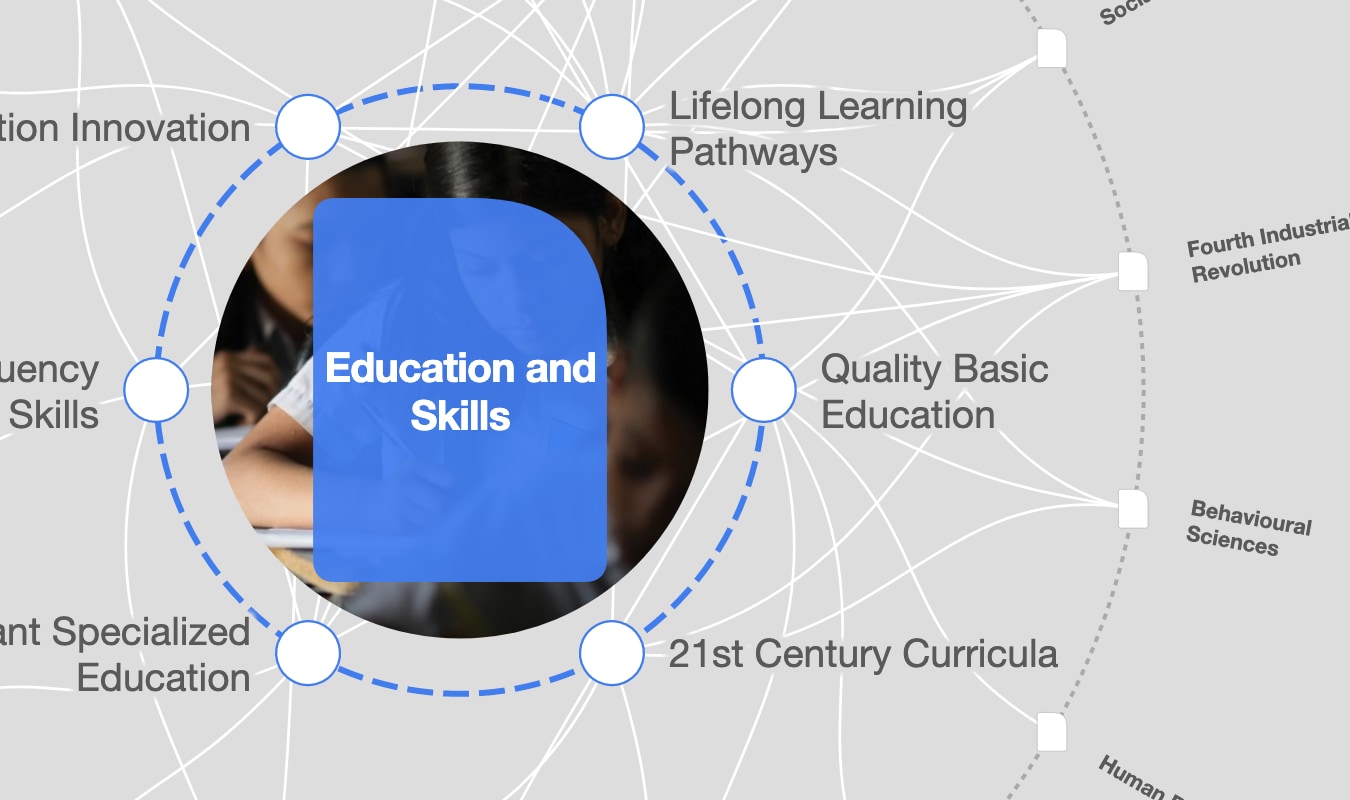

COVID-19 has shown us we must prepare for uncertainty in our future plans for education Image: REUTERS/Cindy Liu

.chakra .wef-spn4bz{transition-property:var(--chakra-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--chakra-transition-duration-fast);transition-timing-function:var(--chakra-transition-easing-ease-out);cursor:pointer;text-decoration:none;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:hover,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-hover]{text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:focus-visible,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-focus-visible]{box-shadow:var(--chakra-shadows-outline);} Andreas Schleicher

- The COVID-19 pandemic shows us we cannot take the future of education for granted.

- By imagining alternative futures for education we can better think through the outcomes, develop agile and responsive systems and plan for future shocks.

- What do the four OECD Scenarios for the Future of Schooling show us about how to transform and future-proof our education systems?

As we begin a new year, it is traditional to take stock of the past in order to look forward, to imagine and plan for a better future.

But the truth is that the future likes to surprise us. Schools open for business, teachers using digital technologies to augment, not replace, traditional face-to face-teaching and, indeed, even students hanging out casually in groups – all things we took for granted this time last year; all things that flew out the window in the first months of 2020.

Have you read?

The covid-19 pandemic has changed education forever. this is how , is this what higher education will look like in 5 years, the evolution of global education and 5 trends emerging amidst covid-19.

To achieve our vision and prepare our education systems for the future, we have to consider not just the changes that appear most probable but also the ones that we are not expecting.

Scenarios for the future of schooling

Imagining alternative futures for education pushes us to think through plausible outcomes and helps agile and responsive systems to develop. The OECD Scenarios for the Future of Schooling depict some possible alternatives:

Rethinking, rewiring, re-envisioning

The underlying question is: to what extent are our current spaces, people, time and technology in schooling helping or hindering our vision? Will modernizing and fine-tuning the current system, the conceptual equivalent of reconfiguring the windows and doors of a house, allow us to achieve our goals? Is an entirely different approach to the organization of people, spaces, time and technology in education needed?

Modernizing and extending current schooling would be more or less what we see now: content and spaces that are largely standardized across the system, primarily school-based (including digital delivery and homework) and focused on individual learning experiences. Digital technology is increasingly present, but, as is currently the case, is primarily used as a delivery method to recreate existing content and pedagogies rather than to revolutionize teaching and learning.

What would transformation look like? It would involve re-envisioning the spaces where learning takes place; not simply by moving chairs and tables, but by using multiple physical and virtual spaces both in and outside of schools. There would be full individual personalization of content and pedagogy enabled by cutting-edge technology, using body information, facial expressions or neural signals.

We’d see flexible individual and group work on academic topics as well as on social and community needs. Reading, writing and calculating would happen as much as debating and reflecting in joint conversations. Students would learn with books and lectures as well as through hands-on work and creative expression. What if schools became learning hubs and used the strength of communities to deliver collaborative learning, building the role of non-formal and informal learning, and shifting time and relationships?

Alternatively, schools could disappear altogether. Built on rapid advancements in artificial intelligence, virtual and augmented reality and the Internet of Things, in this future it is possible to assess and certify knowledge, skills and attitudes instantaneously. As the distinction between formal and informal learning disappears, individual learning advances by taking advantage of collective intelligence to solve real-life problems. While this scenario might seem far-fetched, we have already integrated much of our life into our smartphones, watches and digital personal assistants in a way that would have been unthinkable even a decade ago.

All of these scenarios have important implications for the goals and governance of education, as well as the teaching workforce. Schooling systems in many countries have already opened up to new stakeholders, decentralizing from the national to the local and, increasingly, to the international. Power has become more distributed, processes more inclusive. Consultation is giving way to co-creation.

We can construct an endless range of such scenarios. The future could be any combination of them and is likely to look very different in different places around the world. Despite this, such thinking gives us the tools to explore the consequences for the goals and functions of education, for the organization and structures, the education workforce and for public policies. Ultimately, it makes us think harder about the future we want for education. It often means resolving tensions and dilemmas:

- What is the right balance between modernizing and disruption?

- How do we reconcile new goals with old structures?

- How do we support globally minded and locally rooted students and teachers?

- How do we foster innovation while recognising the socially highly conservative nature of education?

- How do we leverage new potential with existing capacity?

- How do we reconfigure the spaces, the people, the time and the technologies to create powerful learning environments?

- In the case of disagreement, whose voice counts?

- Who is responsible for the most vulnerable members of our society?

- If global digital corporations are the main providers, what kind of regulatory regime is required to solve the already thorny questions of data ownership, democracy and citizen empowerment?

Thinking about the future requires imagination and also rigour. We must guard against the temptation to choose a favourite future and prepare for it alone. In a world where shocks like pandemics and extreme weather events owing to climate change, social unrest and political polarization are expected to be more frequent, we cannot afford to be caught off guard again.

This is not a cry of despair – rather, it is a call to action. Education must be ready. We know the power of humanity and the importance of learning and growing throughout our life. We insist on the importance of education as a public good, regardless of the scenario for the future.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Education, gender and work, related topics:.

.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-ugz4zj{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);color:var(--chakra-colors-yellow);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-ugz4zj{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-19044xk{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);color:var(--chakra-colors-uplinkBlue);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-19044xk{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

The agenda .chakra .wef-dog8kz{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineheights-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontweights-normal);} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:flex;align-items:center;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Forum Institutional .chakra .wef-17xejub{flex:1;justify-self:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-2sx2oi{display:inline-flex;vertical-align:middle;padding-inline-start:var(--chakra-space-1);padding-inline-end:var(--chakra-space-1);text-transform:uppercase;font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smallest);border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontWeights-bold);background:none;box-shadow:var(--badge-shadow);align-items:center;line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-short);letter-spacing:1.25px;padding:var(--chakra-space-0);white-space:normal;color:var(--chakra-colors-greyLight);box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width: 37.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smaller);}}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-base);}} See all

This social enterprise uses basketball to get young people back into school

Here's how to mobilize for Sustainable Development Goal 14 ahead of UN Ocean Conference 2025

Uniting for sustainability: How regional cooperation can keep MENA businesses competitive

How the Global Future Councils use 'knowledge collisions' to address today’s challenges

Country Strategy Meeting - Argentina

AI value alignment: How we can align artificial intelligence with human values

Models in Pedagogy and Education

- pp 1033–1049

Cite this chapter

- Flavia Santoianni 2

Part of the book series: Springer Handbooks ((SHB))

5259 Accesses

3 Citations

Pedagogy is a discipline concerned with theories and practices of education. Its epistemological model is complex. It may be considered as qualified by two structural directions: pluralism and dialecticity .

The pluralism of pedagogy is represented by its possible theoretical routes, by the different levels of sharing of disciplinarity and by a multiplicity of aspects. It involves empirical and experimental research, historical and philosophical dimensions, and epistemological and metatheoretical lines. The theoretical plurality of pedagogy concerns subjects, ages and places of education, languages and research methods, and actual directions and interpretative issues. The multidisciplinary plurality of pedagogy distinguishes it in pedagogical sciences, educational sciences, and educational developmental sciences. The disciplinary multiplicity of pedagogy is expressed by the diversity of pedagogical sciences that belong to general pedagogy. Even if pedagogical sciences are multiple, social pedagogy, history of pedagogy and special needs education are disciplines specifically related to the field of pedagogy.

The dialecticity of pedagogy expresses its controversial nature divided between science and philosophy. The scientific approach to pedagogy evolves from systematicity to complexity. It develops, namely, in parallel with the construction and the reconstruction of the very idea of science. The systematization of educational sciences strengthens the philosophical role of pedagogy. The so-called identity crisis of pedagogy will bring it to rediscover the sense of its own reflexive intentionality. The relationship between theory and practice makes pedagogy a science of education, in particular a theory of educational development processes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Section 2 – Philosophy of Education: Schools of Thought

Between Education and Pedagogy

Slovenian Pedagogy between Social Sciences and Humanities

Abbreviations.

ease of learning

feeling of knowing

judgment of learning

prediction of total recall

F. Cambi: Il Congegno del Discorso Pedagogico (Clueb, Bologna 1986), in Italian

Google Scholar

D.H. Jonassen, B.L. Grabowski: Handbook of Individual Differences Learning and Instruction (Routledge, New York, London 2011)

H.L. Swanson, K.R. Harris, S. Graham (Eds.): Handbook of Learning Disabilities (Guilford, New York 2013)

B.Y.L. Wong, D.L. Butler (Eds.): Learning About Learning Disabilities (Elsevier, San Diego 2012)

P. Tinkler, C. Jackson: The past in the present: Historicising contemporary debates about gender and education, Gender Educ. 26 (1), 70–86 (2014)

Article Google Scholar

P. Stephens: Social Pedagogy: Heart and Head (Europäischer Hochschulverlag, Bremen 2013)

G.S. Levine, A. Phipps, C. Blyth (Eds.): Critical and Intercultural Theory and Language Pedagogy (Cengage Learning, Florence 2010)

J.A. Banks: Cultural Diversity and Education: Foundations, Curriculum, and Teaching (Pearson Allyn Bacon, Boston 2001)

J. Clarke, A. Hanson, R. Harrison, F. Reeve (Eds.): Supporting Lifelong Learning: Perspectives on Learning (RoutledgeFalmer, London 2002)

P. Jarvis: Twentieth Century Thinkers in Adult and Continuing Education (Taylor Francis, Oxford 2012)

M.S. Knowles, E.F.I.I.I. Holton, R.A. Swanson: The Adult Learner (Elsevier, London 2011)

Z. Bekerman, N.C. Burbules, D. Silberman-Keller (Eds.): Learning in Places: The Informal Education Reader (Peter Lang, New York 2006)

F. Santoianni: Modelli di Studio. Apprendere con la Teoria Delle Logiche Elementari (Erickson, Trento 2014), in Italian

A. Rogers: Non-Formal Education: Flexible Schooling or Participatory Education? (Kluwer, New York 2005)

V.C.X. Wang, L. Farmer, J. Parker, P.M. Golubski: Pedagogical and Andragogical Teaching and Learning with Information Communication Technologies (IGI Global, Hershey 2012)

Book Google Scholar

P. Petrie: Communication Skills for Working with Children and Young People (Jessica Kingsley, London 2011)

A.A. Ciccone, R.A.R. Gurung, N.L. Chick, A. Haynie (Eds.): Exploring Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind (Stylus, Sterling 2008)

S.N. Hesse-Biber: Mixed Methods Research: Merging Theory with Practice (Guilford, New York 2010)

M. Gennari, A. Kaiser: Prolegomeni alla Pedagogia Generale (Bompiani, Milano 2000), in Italian

G.L. De Landsheere: History of educational research. In: International Encyclopedia of Education , Vol. 3, ed. by T. Husen, T.N. Postlethwaite (Pergamon, Oxford 1985)

G. Mialaret: Les Sciences de L’éducation (Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1976), in French

J. Dewey: The Sources of a Science of Education (Horace Liveright, New York 1929)

H. Daniels: Vygotsky and Pedagogy (RoutledgeFalmer, London 2001)

L.R. Meeth: Interdisciplinary studies: Integration of knowledge and experience, Change 10 , 6–9 (1978)

R. Nola, G. Irzik: Philosophy, Science, Education and Culture (Springer, Dordrecht 2005)

J. Storø: Practical Social Pedagogy (The Policy Press, Bristol 2013)

P. Orefice: Participatory research methods in the education of adult: Theoretical and methodological aspects. In: Towards the End of Teaching? Innovation in European Adult Learning , ed. by M. Dale (NIACE, Leicester 2000)

F. Cambi: Storia Della Pedagogia (Laterza, Roma-Bari 1995), in Italian

H. Leser: Das pädagogische Problem in der Geistesgeschichte der Neuzeit (Oldenburg, München 1925), in German

J. Dewey: Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (Macmillan, New York 1916)

F. Cambi: Abitare il Disincanto. Una Pedagogia per il Postmoderno (UTET Università, Turin 2006), in Italian

E.C. Winter: Preparing new teachers for inclusive schools and classrooms, Support Learn. 21 (2), 85–91 (2006)

G. Golder, B. Norwich, P. Bayliss: Preparing teachers to teach pupils with special educational needs in more inclusive schools: Evaluating a PGCE development, Br. J. Special Educ. 32 (2), 92–99 (2005)

M. Nind, J. Rix, K. Sheehy, K. Simmons (Eds.): Curriculum and Pedagogy in Inclusive Education. Values into Practice (Routledge, New York 2013)

F. Santoianni: La Fenice Pedagogica. Linee di Ricerca Epistemologica (Liguori, Napoli 2007), in Italian

R.L. Zigler: The holistic paradigm in educational theory, Educ. Theory 28 (4), 318–326 (1978)

J.F. Herbart: Allgemeine Pädagogik, aus dem Zweck der Erziehung abgeleitet (1806). In: Pädagogische Grundschriften , Pädagogische Schriften, Vol. 2, ed. by W. Asmus (Klett, Stuttgart 1982)

E. Morin: Introduction à la Pensée Complexe (ESF, Thiron 1990), in French

E. Morin: Science Avec Conscience (Fayard, Paris 1982), in French

F. De Bartolomeis: La pedagogia come scienza (La Nuova Italia, Firenze 1953)