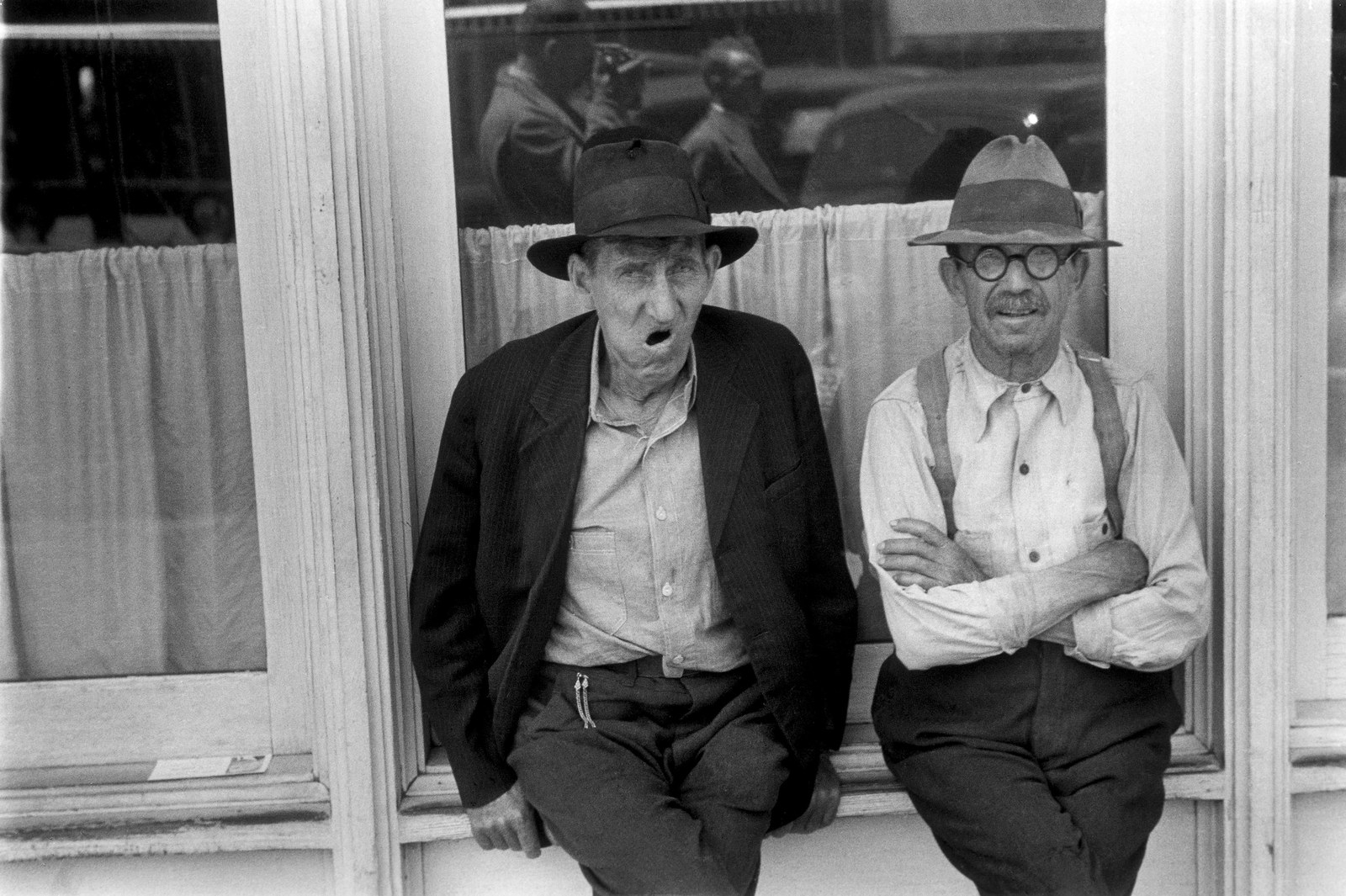

These Photographs Capture the American struggle during The Great Depression, 1929-1940

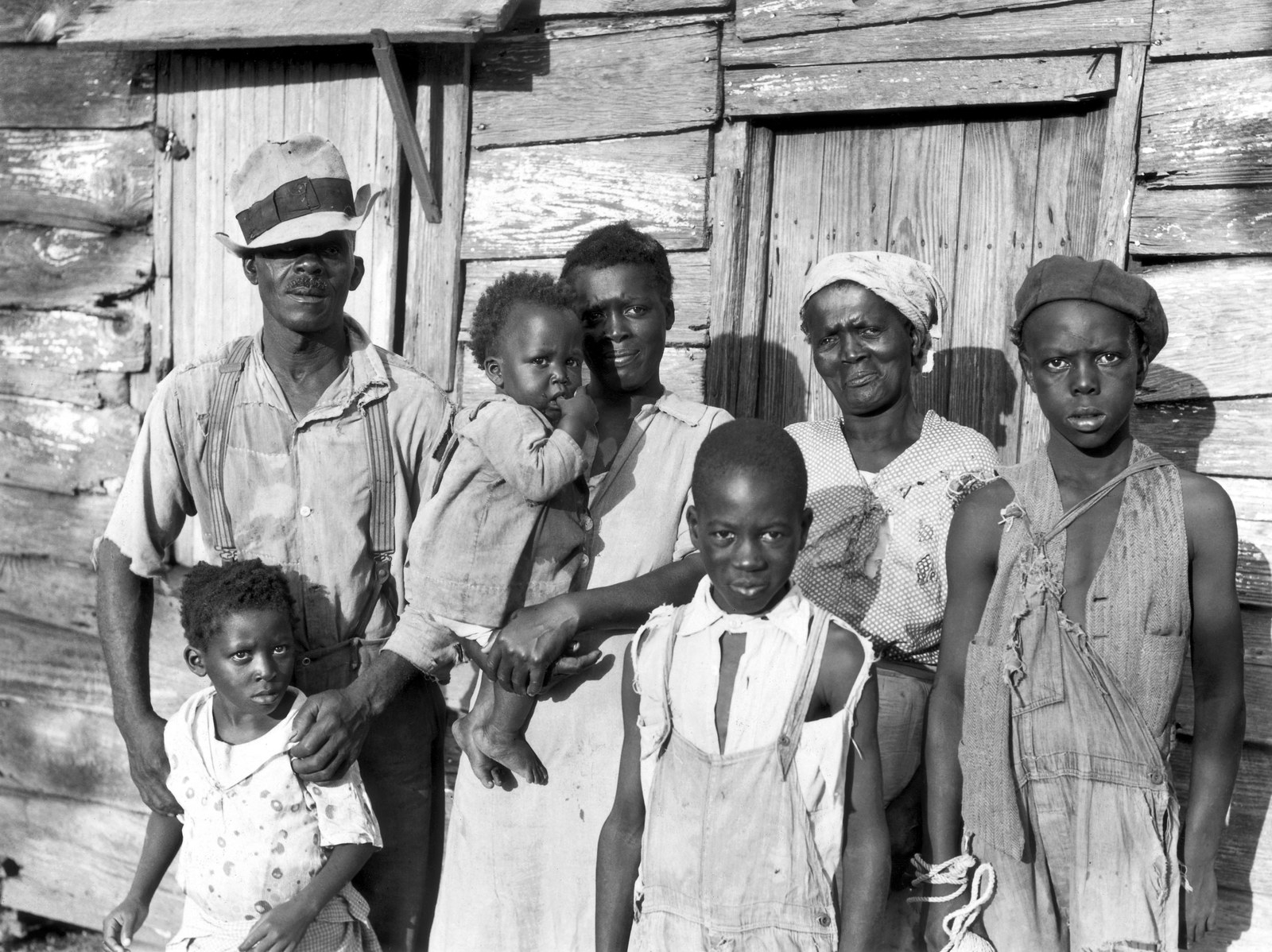

A cotton sharecropper with his family at their home in Hale County, Alabama, 1935.

Nobody could tell exactly when it began and nobody could predict when it would end. At the outset, they didn’t even call it a depression.

At worst it was a recession, a brief slump, a “correction” in the market, a glitch in the rising curve of prosperity.

Only when the full import of those heartbreaking years sank in did it become the Great Depression – Great because there had been no other remotely like it.

Crowd of men at Employment Office Desk.

In retrospect, we see it as a whole – as a neat decade tucked in between the Roaring Twenties and the Second World War, perhaps the most significant ten years in American history, a watershed era that perhaps scarred and transformed the nation.

But it hasn’t been easy for later generations to comprehend its devastating impact. The Great Depression lies just over the hill of memory; after all, it has been such a long time.

A struggling family during the Great Depression.

The Great Depression began in August 1929, when the economic expansion of the Roaring Twenties came to an end.

A series of financial crises punctuated the contraction. These crises included a stock market crash in 1929, a series of regional banking panics in 1930 and 1931, and a series of national and international financial crises from 1931 through 1933.

The downturn hit bottom in March 1933, when the commercial banking system collapsed and President Roosevelt declared a national banking holiday.

Between 1929 and 1932, worldwide gross domestic product (GDP) fell by an estimated 15%. By comparison, worldwide GDP fell by less than 1% from 2008 to 2009 during the Great Recession.

An unemployed man lies down on the New York docks. 1935.

Although the Great Depression was relatively mild in some countries, it was severe in others, particularly in the United States, where, at its nadir in 1933, 25 percent of all workers and 37 percent of all nonfarm workers were completely out of work.

Some people starved; many others lost their farms and homes. Homeless vagabonds sneaked aboard the freight trains that crossed the nation.

Dispossessed cotton farmers, the “Okies,” stuffed their possessions into dilapidated Model Ts and migrated to California in the false hope that the posters about plentiful jobs were true.

By 1933, industrial production declined by 50 percent, international trade plunged 30 percent, and investment fell 98 percent.

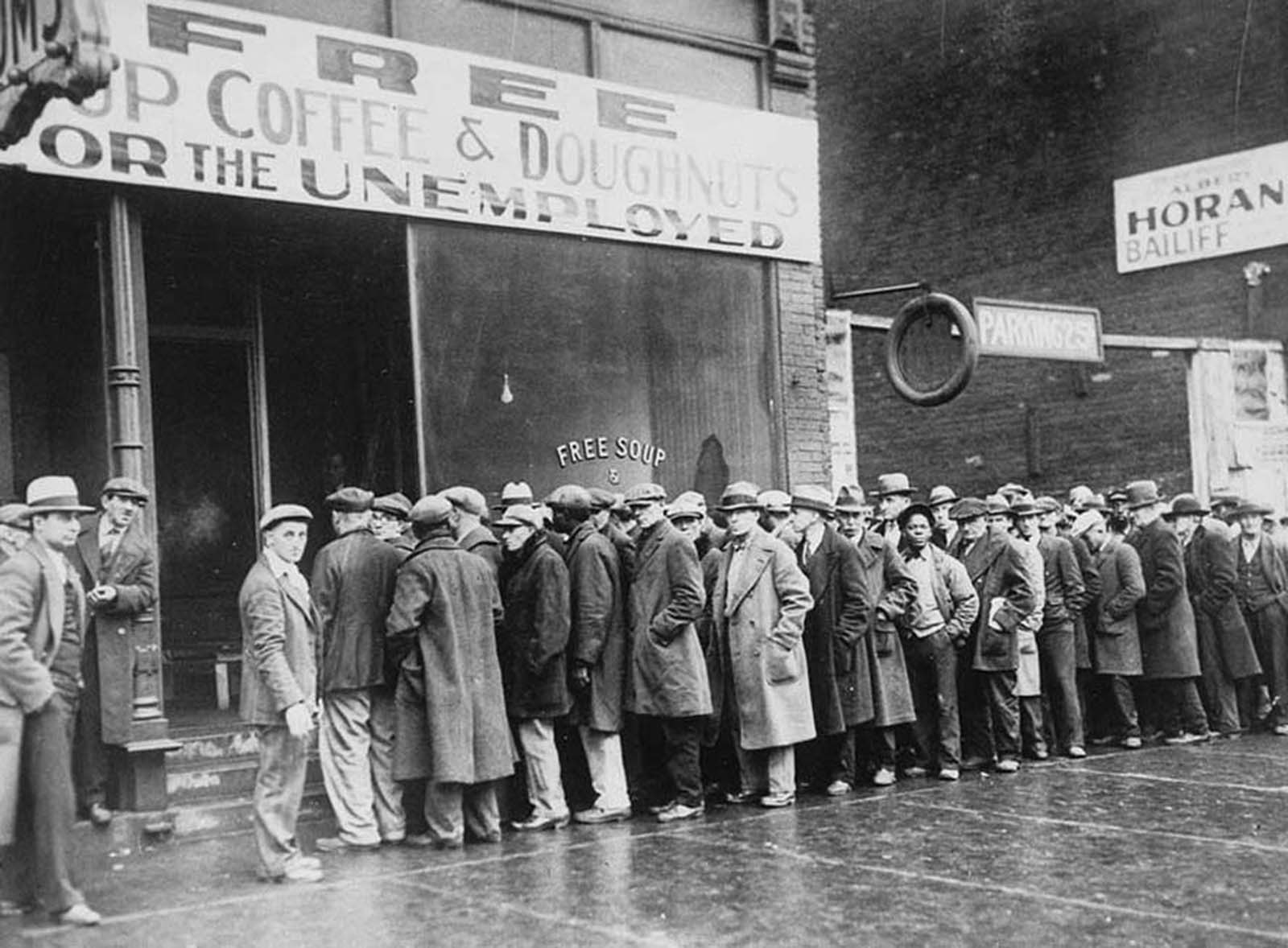

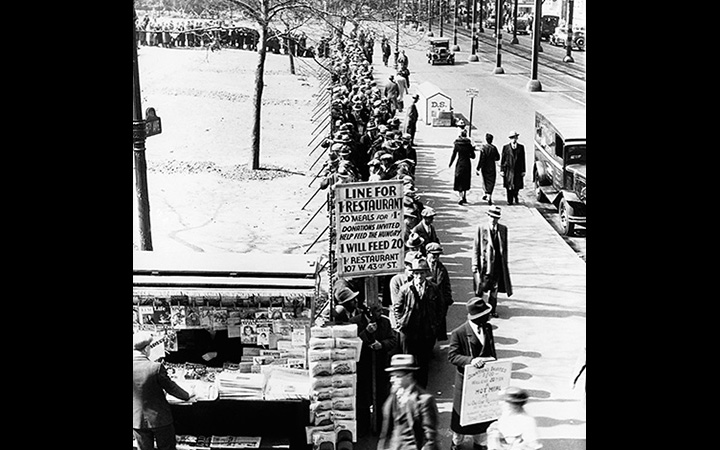

Unemployed men line up in front of a Chicago soup kitchen, which was operated by Al Capone.

Cities around the world were hit hard, especially those dependent on heavy industry. Construction was virtually halted in many countries.

Farming communities and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell by about 60%.

Facing plummeting demand with few alternative sources of jobs, areas dependent on primary sector industries such as mining and logging suffered the most.

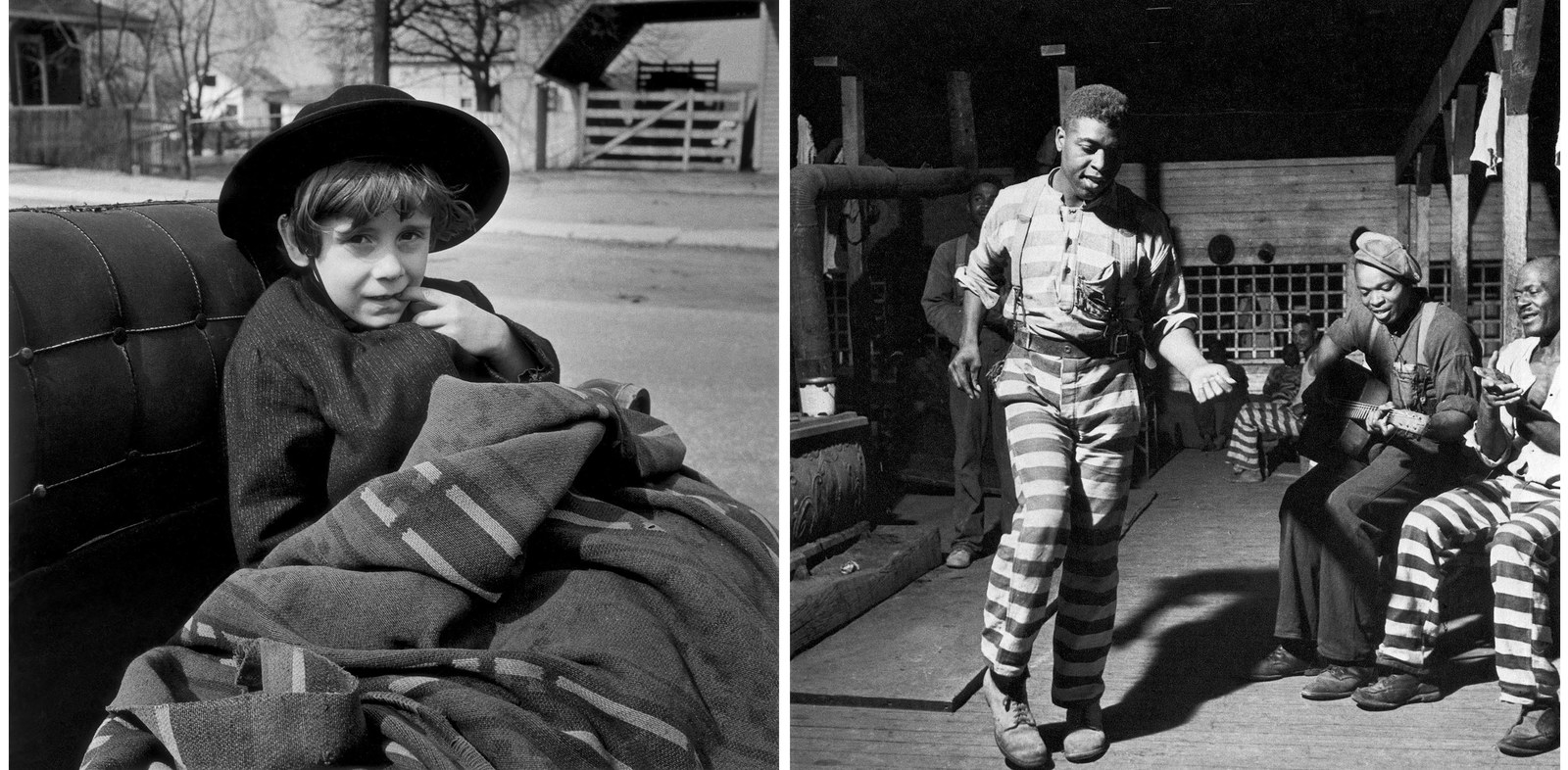

Arkansas cotton pickers. 1935.

Drought persisted in the agricultural heartland, businesses and families defaulted on record numbers of loans, and more than 5,000 banks had failed.

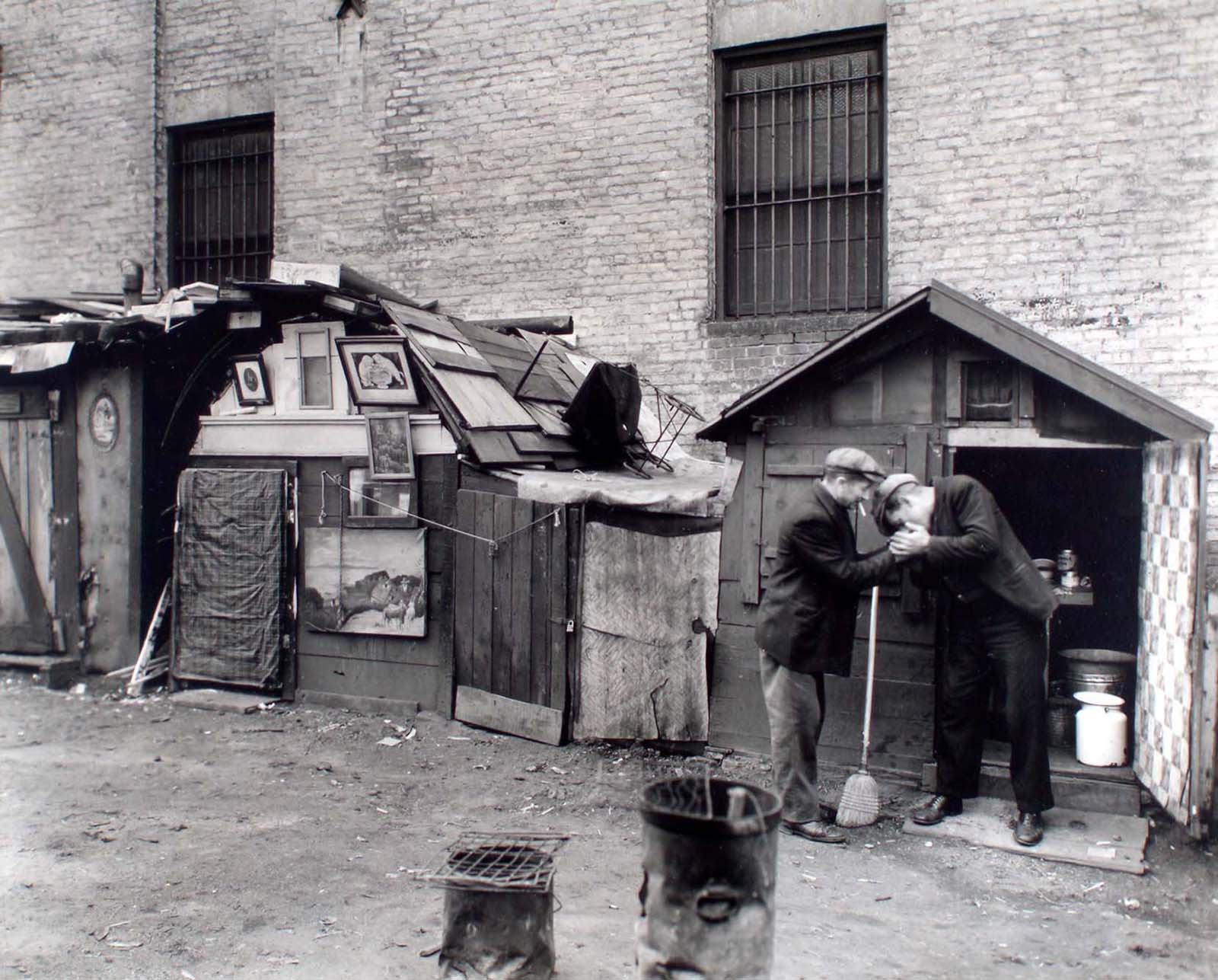

Hundreds of thousands of Americans found themselves homeless, and began congregating in shanty towns – dubbed “Hoovervilles” – that began to appear across the country.

In most countries of the world, recovery from the Great Depression began in 1933. In the U.S., recovery began in early 1933, but the U.S. did not return to 1929 GNP for over a decade and still had an unemployment rate of about 15% in 1940, albeit down from the high of 25% in 1933.

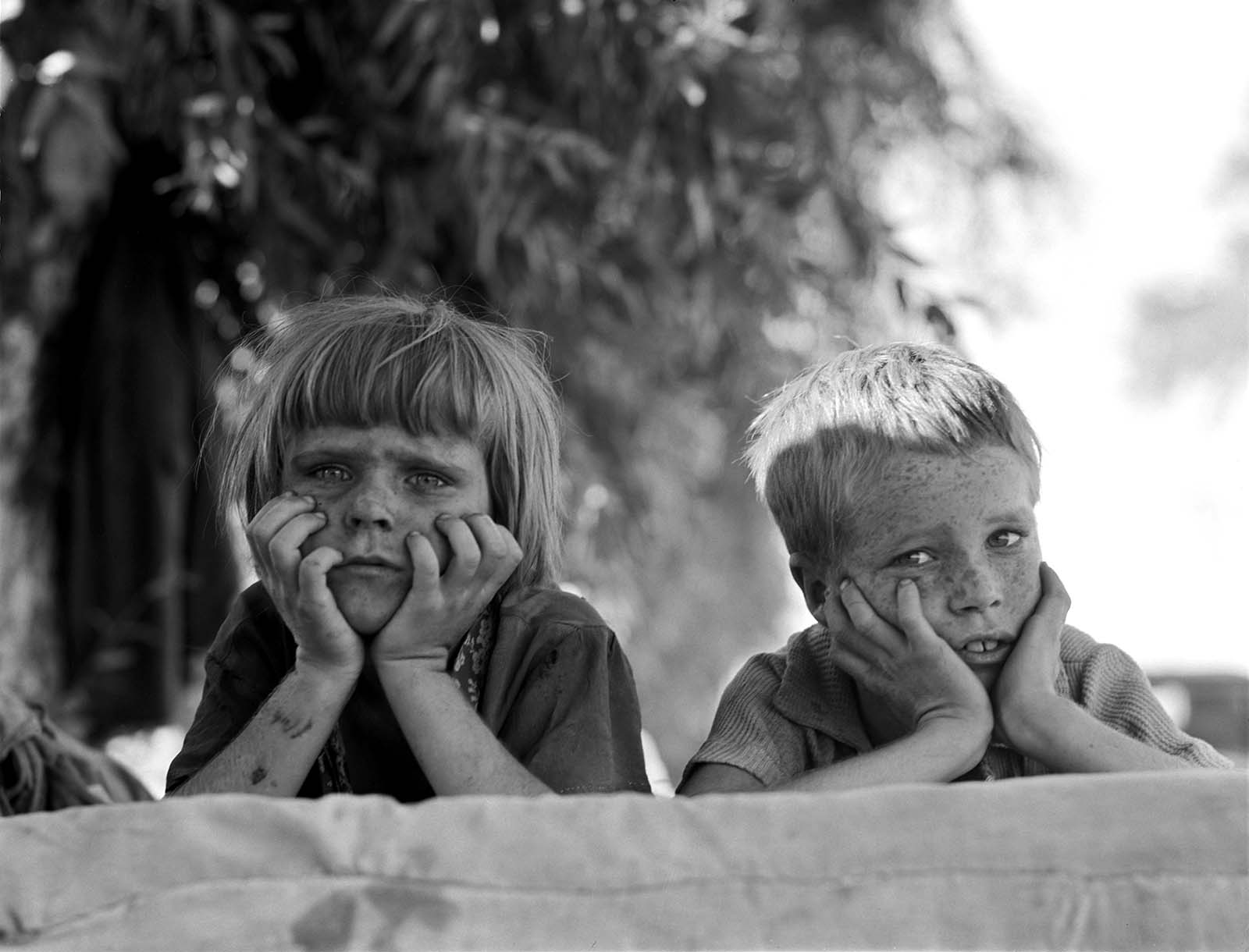

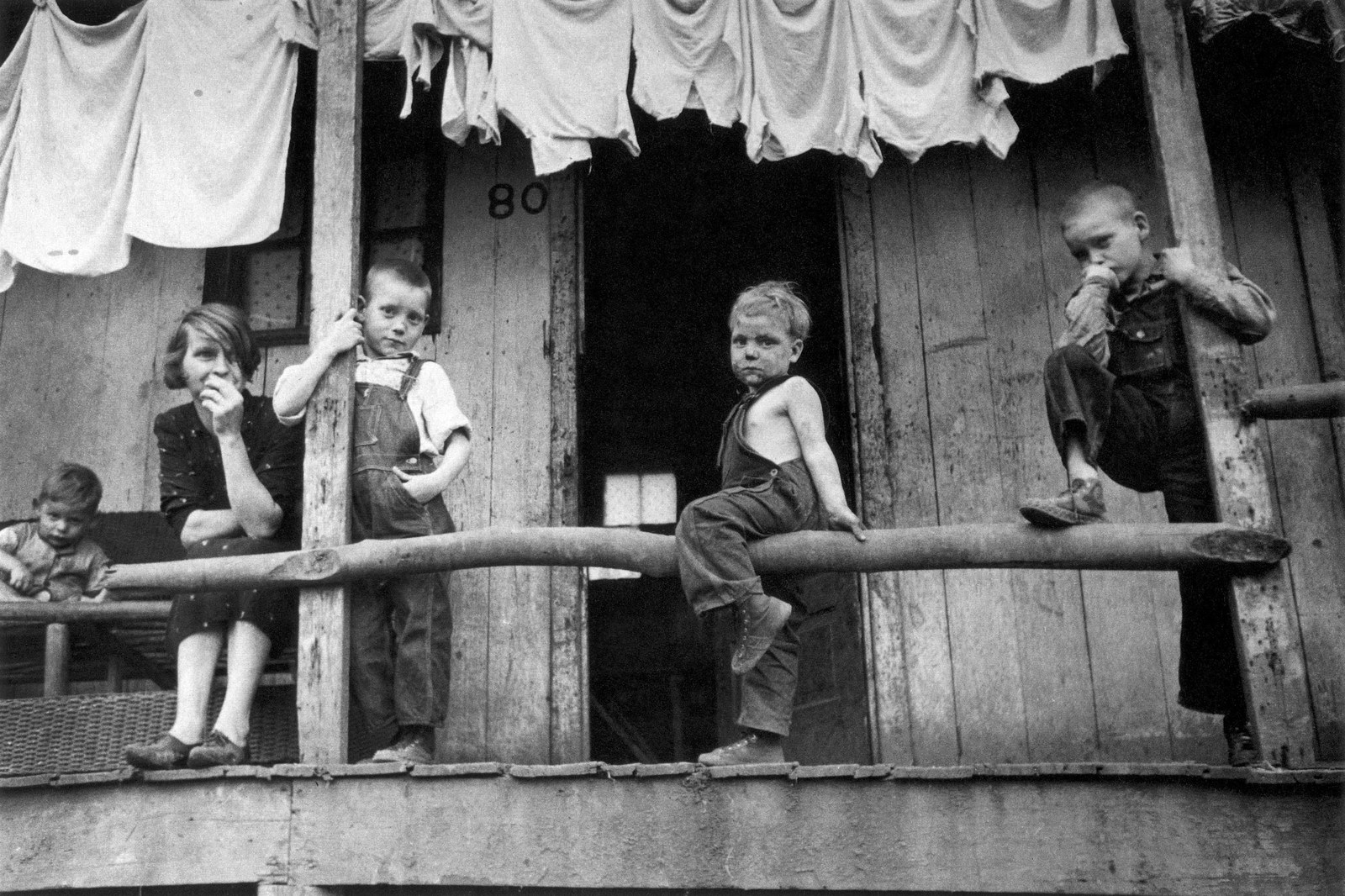

Two young boys sit on the porch in Arkansas, 1935.

There is no consensus among economists regarding the motive force for the U.S. economic expansion that continued through most of the Roosevelt years (and the 1937 recession that interrupted it).

The common view among most economists is that Roosevelt’s New Deal policies either caused or accelerated the recovery, although his policies were never aggressive enough to bring the economy completely out of recession.

Some economists have also called attention to the positive effects from expectations of reflation and rising nominal interest rates that Roosevelt’s words and actions portended.

It was the rollback of those same reflationary policies that led to the interruption of a recession beginning in late 1937.

Public health nurses from the Child Welfare Service visit a shanty home for a checkup.

One contributing policy that reversed reflation was the Banking Act of 1935, which effectively raised reserve requirements, causing a monetary contraction that helped to thwart the recovery. GDP returned to its upward trend in 1938.

The common view among economic historians is that the Great Depression ended with the advent of World War II.

Many economists believe that government spending on the war caused or at least accelerated recovery from the Great Depression, though some consider that it did not play a very large role in the recovery, though it did help in reducing unemployment.

A poor mother stands with her two children in Oklahoma. 1936..

The Great Depression transformed the American political and economic landscape.

It produced a major political realignment, creating a coalition of big-city ethnics, African Americans, organized labor, and Southern Democrats committed, to varying degrees, to interventionist government.

It strengthened the federal presence in American life, spawning such innovations as national old-age pensions, unemployment compensation, aid to dependent children, public housing, federally-subsidized school lunches, insured bank depositions, the minimum wage, and stock market regulation.

The family of an unemployed man sits around a wood stove in their empty home, 1937.

It fundamentally altered labor relations, producing a revived labor movement and a national labor policy protective of collective bargaining.

It transformed the farm economy by introducing federal price supports.

Above all, it led Americans to view the federal government as an agency of action and reform and the ultimate protector of public well-being.

Children from the homes of unemployed miners gather together for nursery school in March of 1937 in Scott’s Run, West Virginia.

The memory of the Depression also shaped modern theories of economics and resulted in many changes in how the government dealt with economic downturns, such as the use of stimulus packages, Keynesian economics, and Social Security.

It also shaped modern American literature, resulting in famous novels such as John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men.

The Central Park of New York City became Hooverville, a shanty town for the newly impoverished (named for President Herbert Hoover, in office during the market crash and widely blamed for it). 1933.

An old woman receives her Thanksgiving ration of food as other hungry people wait in line. 1930s.

Unemployed men sit outside their makeshift homes in lower Manhattan, 1935.

A large group of New Yorkers waits on a food line, 1932.

Unemployed men smoke cigarettes amid their shantytown in lower Manhattan, 1935.

Men wait on a breadline in New York, 1932.

Unemployed single women march to demand jobs, 1933.

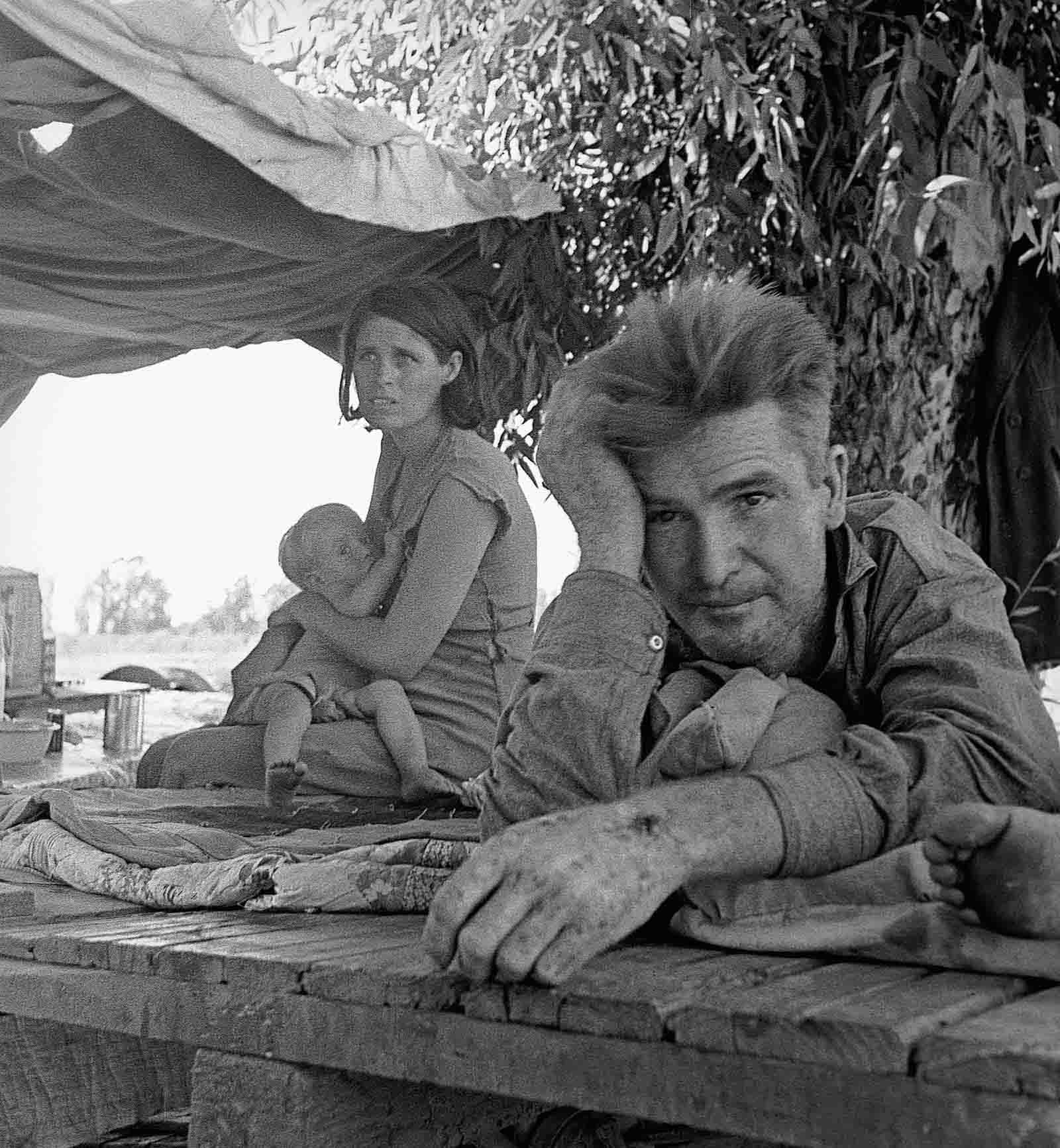

A family of migrant workers fleeing from the drought in Oklahoma camp by the roadside in Blythe, California, 1936.

An unemployed man during the Great Depression.

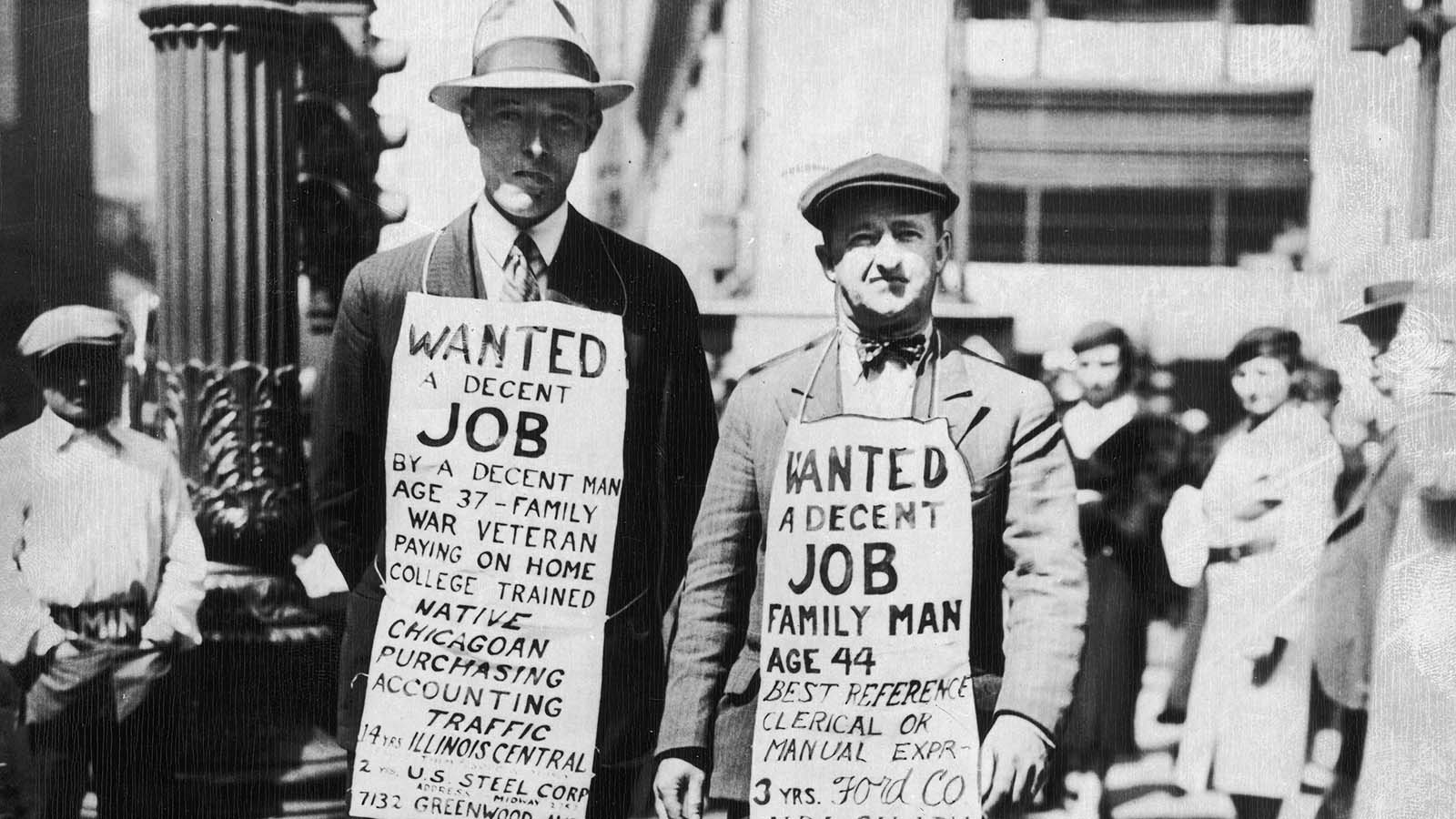

Men looking for work hold up signs. 1930s.

Children from Oklahoma staying in a migratory camp in California. 1936.

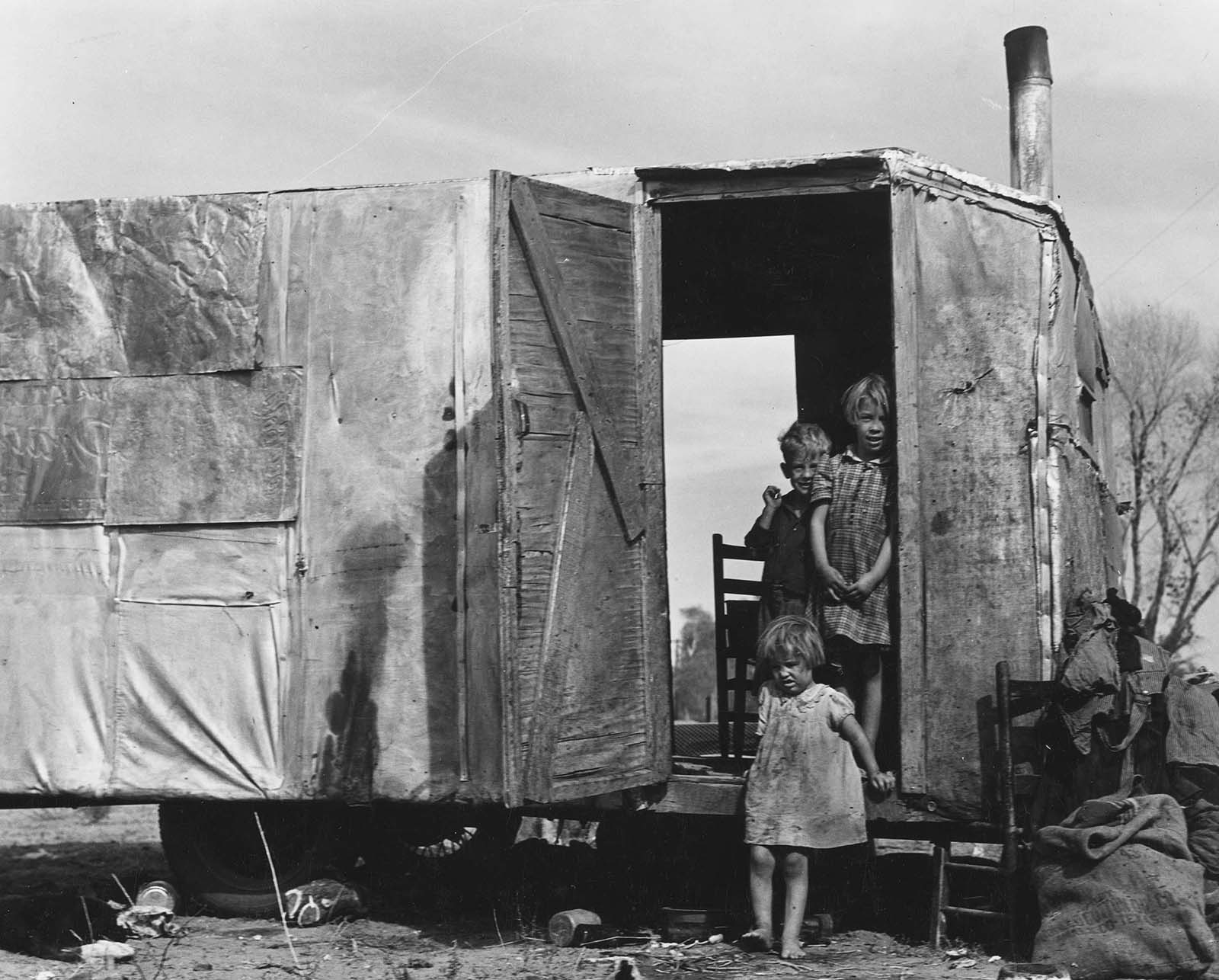

The children of a migrant family living in a trailer in the middle of a field south of Chandler, Arizona, 1940.

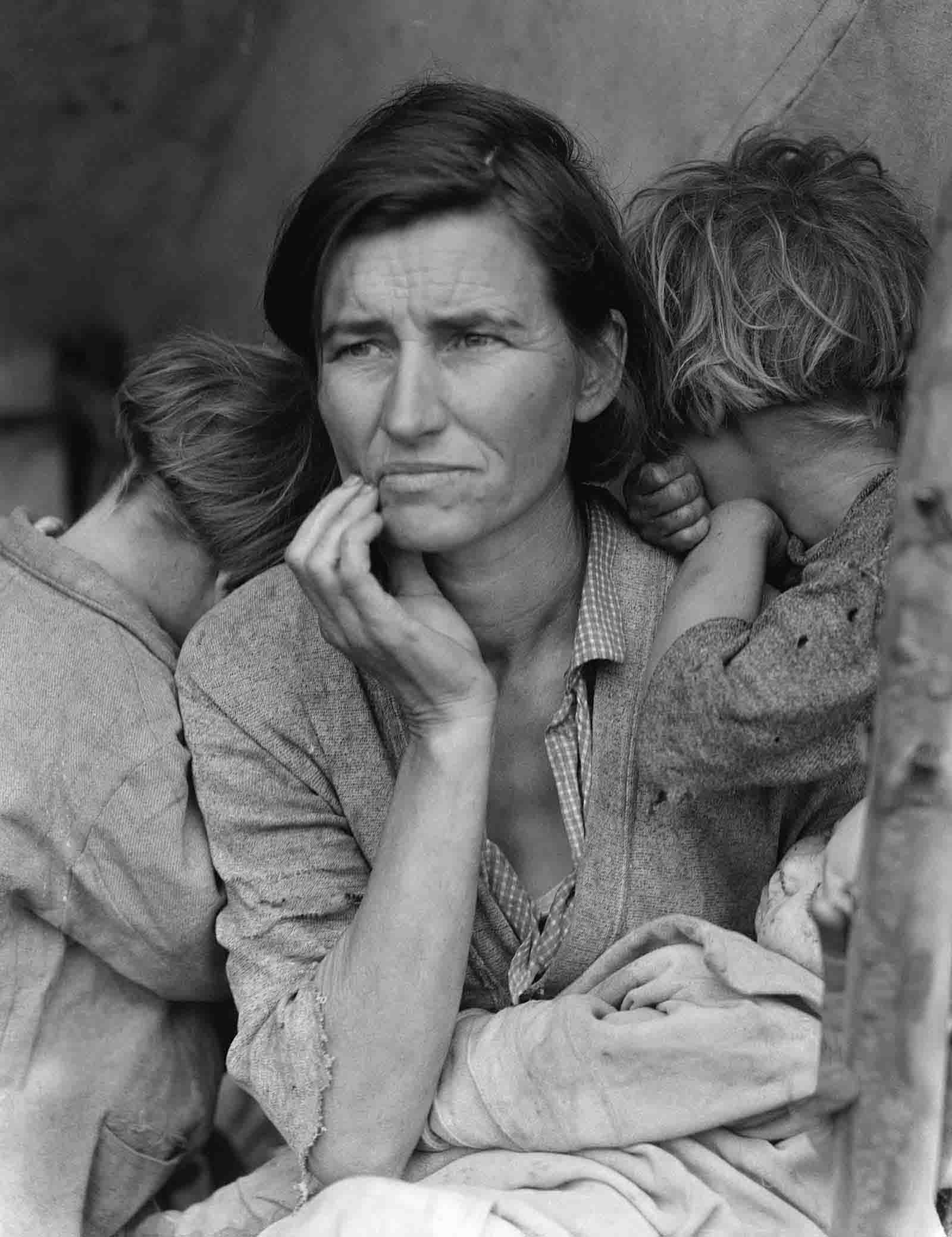

Thirty-two-year-old Florence Owens Thompson with three of her seven children at a pea pickers’ camp in Nipomo, California, 1936. The picture is famously known as “The Migrant Mother” .

Crowd gathering at the intersection of Wall Street and Broad Street after the 1929 crash.

Crowd at New York’s American Union Bank during a bank run early in the Great Depression.

Crowds outside the Bank of United States in New York after its failure in 1931.

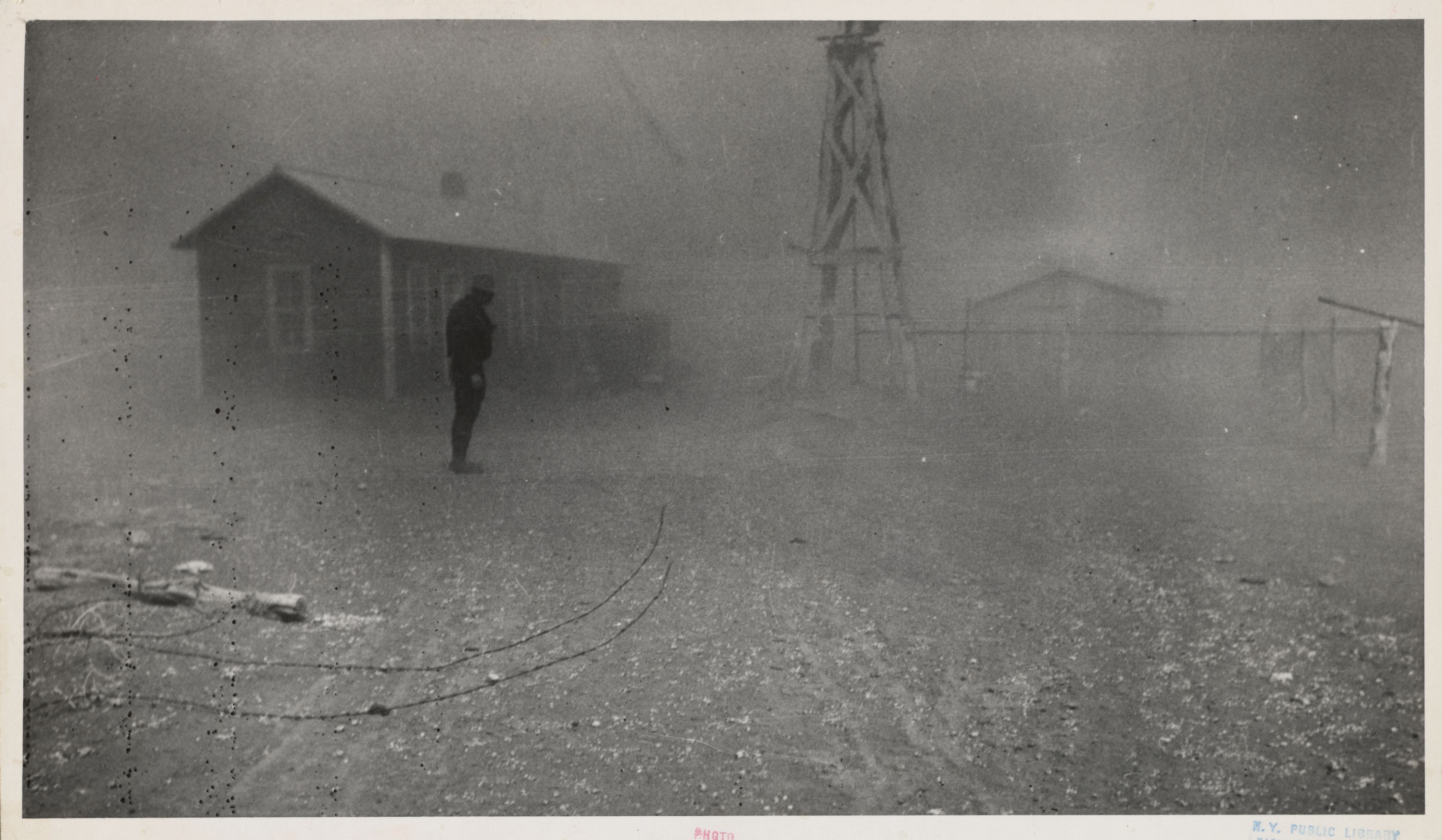

Buried machinery in a barn lot; South Dakota, May 1936. The Dust Bowl on the Great Plains coincided with the Great Depression.

Greek migratory woman living in a cotton camp near Exeter, California, ca. 1935.

Unemployed coal miner’s daughter carrying home can of kerosene. Company housing, Scotts Run, W. Va., 1938.

Farmer walking in dust storm. Cimarron County, Oklahoma circa 1936.

Government agent interviewing a prospective resettlement client in Garrett County, Maryland circa 1938.

Prospective homesteaders in front of the post office at United, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. 1935.

Power farming displaces tenants from the land in the western dry cotton area. Childress County, Texas, 1938.

Farm foreclosure sale. 1930s.

Toward Los Angeles, California.

Schoolchildren line up for the free issue of soup and a slice of bread during the Depression. 1934.

Unemployed workers sleeping in the bandstand at a park. 1938.

Interior of Ozark cabin housing six people,” Carl Mydans, Missouri, May 1936.

Lewis Hunter with his family, Lady’s Island, Beaufort,” Carl Mydans, South Carolina, June 1936.

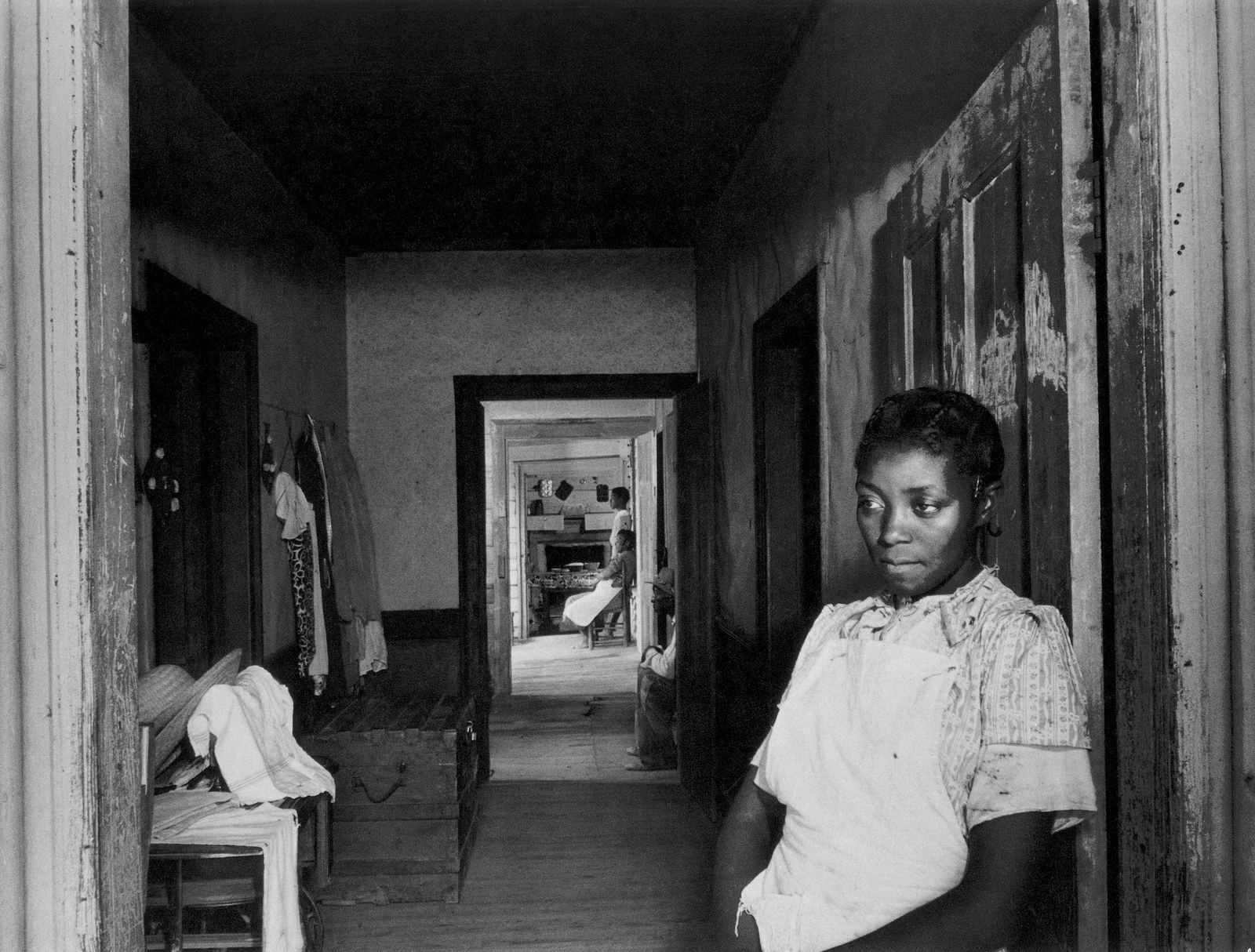

Interior of a rural home, Greene County, Georgia.

Family of migrant packinghouse workers in their quarters, Homestead, Florida. 1939.

Tenant farmer moving his household goods to a new farm, Hamilton County, Tennessee. 1937.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons).

Updated on: July 22, 2024

Any factual error or typo? Let us know.

THE DEPRESSION

Everyone was so shocked and panicky. No one knew what was ahead. — Dorothea Lange

THE DEPRESSION Topics

Discovering a Purpose: Early Documentary Work

The Dust Bowl

On the Road

In the Camps

In the Fields

Deep South: Picturing Race and Power

An American Exodus: A New Kind of Book

Migrant Mother: Birth of An Icon

Previous Section

EARLY WORK / PERSONAL WORK

Next Section

WORLD WAR II AT HOME

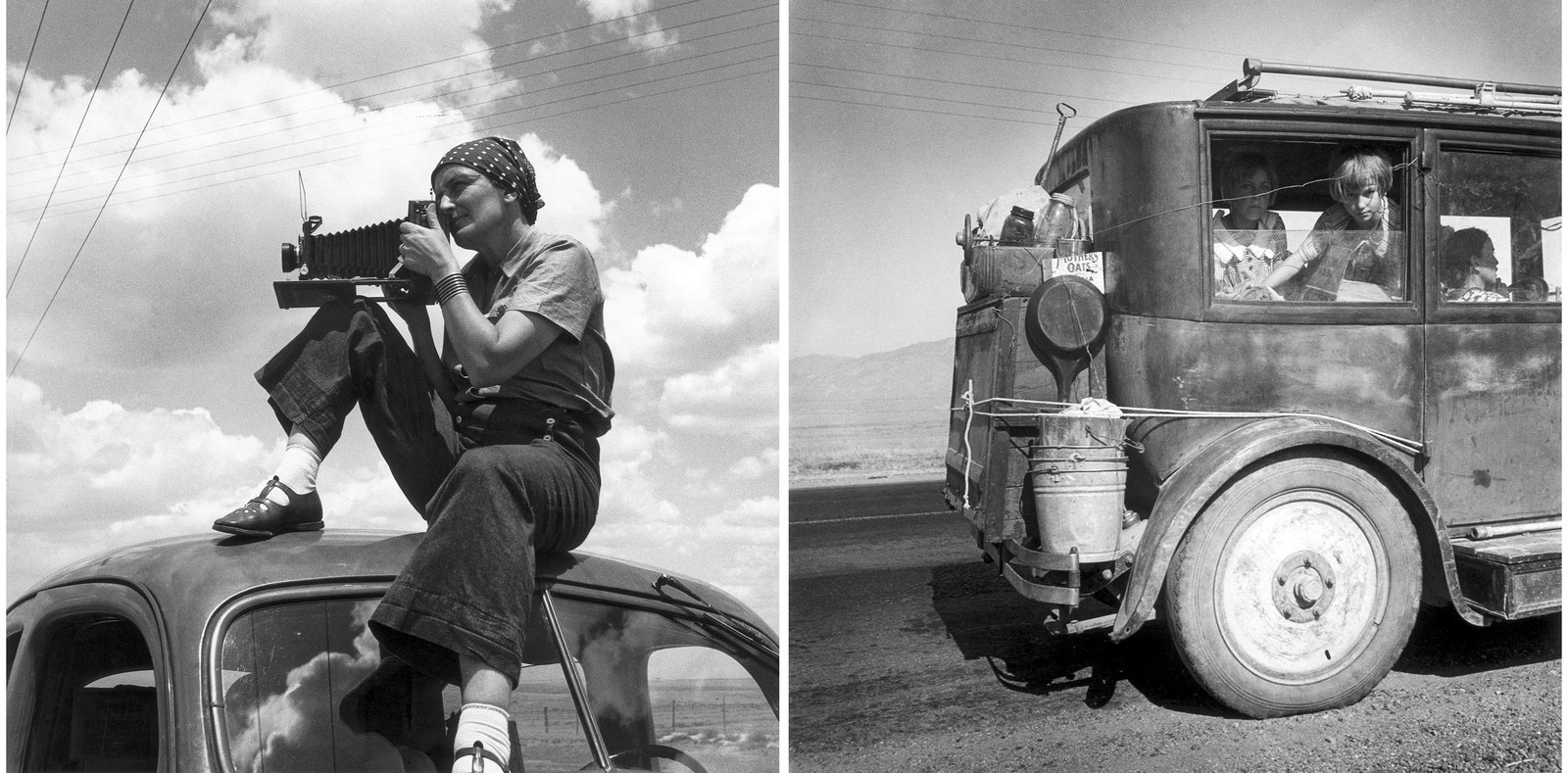

Dorothea Lange's Moving Photographs of The Depression Era

Editorial feature.

By Google Arts & Culture

Words by Rebecca Fulleylove

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco (1933) by Dorothea Lange San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

Meet the woman who showed America the consequences of the Great Depression

1. White Angel Breadline , San Francisco, 1933

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

2. Migrant Mother , Nipomo, California, 1936

Migrant Mother, Nipoma, California (1936, printed 1976) by Dorothea Lange The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

3. Damaged Child, Shacktown , Elm Grove, Oklahoma, 1936

Damaged Child, Shacktown, Elm Grove, Oklahoma (1936) by Dorothea Lange George Eastman Museum

Damaged Child, Shacktown, Oklahoma by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of George Eastman Museum)

4. Ex-Slave With Long Memory , Alabama, 1937

Ex-Slave with Long Memory, Alabama (1937) by Dorothea Lange George Eastman Museum

Ex-Slave With Long Memory, Alabama by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of George Eastman Museum)

5. Six Tenant Farmers Without Farms , Hardeman County, Texas, 1937

Six Tenant Farmers without Farms, Hardeman County, Texas (May 1937, printed 1976) by Dorothea Lange The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Six Tenant Farmers Without Farms by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

Explore more: – 7 Gordon Parks Images That Changed American Attitudes

The Usable Past: Reflections on American History 2000–2017

The museum of fine arts, houston, eastman: the inventor, george eastman museum, passion for perfection: the straus collection of renaissance art, cameras + fashion, space city: photographs from the museum of fine arts, houston, a renaissance couple, latino experience in the usa: works from the mfah collection, funny faces, #5womenartists, artistic genus: depictions of animals in the collections of the museum of fine arts, houston.

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- American History ›

- Key Events ›

Great Depression Pictures

These 35 Photos Show the Economic Impact of the Great Depression

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Amadeo-Closeup-582619cd3df78c6f6acca4e6.jpg)

- M.B.A, MIT Sloan School of Management

- M.S.P, Social Planning, Boston College

- B.A., University of Rochester

The Farm Security Administration hired photographers to document the living conditions of the Great Depression . They are a landmark in the history of documentary photography. The photos show the adverse effects of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl . Some of the most famous images portray people who were displaced from farms and migrated west or to industrial cities in search of work. These photos show better than charts and numbers the economic impact of the Great Depression.

Dust Attacks a Town

A dust storm rolled into Elkhart, Kansas, on May 21, 1937. The year before, the drought caused the hottest summer on record . In June, eight states experienced temperatures at 110 or greater. In July, the heat wave hit 12 more states : Iowa, Kansas (121 degrees), Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, North Dakota (121 degrees), Oklahoma (120 degrees), Pennsylvania, South Dakota (120 degrees), West Virginia, and Wisconsin. In August, Texas saw 120-degree record-breaking temperatures.

It was also the deadliest heat wave in U.S. history, killing 1,693 people. Another 3,500 people drowned while trying to cool off.

Causes of the Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was caused by the worst drought in North America in 300 years. In 1930, weather patterns shifted over the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The Pacific grew cooler than normal and the Atlantic became warmer. The combination weakened and changed the direction of the jet stream.

There were four waves of droughts: 1930-1931, 1934, 1936, and 1939-1940. The affected regions could not recover before the next one hit. By 1934, the drought covered 75% of the country, affecting 27 states. The worst-hit was the Oklahoma panhandle.

Once farmers settled the Midwest prairies, they plowed over 5.2 million acres of the tall, deep-rooted prairie grass. When the drought killed off the crops, high winds blew the topsoil away.

Effects of the Dust Bowl

Dust storms helped cause The Great Depression. Dust storms nearly covered buildings, making them useless. People became very ill from inhaling the dust.

These storms forced family farmers to lose their business, their livelihood, and their homes. By 1936, 21% of all rural families in the Great Plains received federal emergency relief. In some counties, it was as high as 90%.

Families migrated to California or cities to find work that often didn't exist by the time they got there. As farmers left in search of work, they became homeless. Almost 6,000 shanty towns, called Hoovervilles, sprang up in the 1930s.

Farming in 1935

This photo shows a team of two work horses hitched to a wagon with farm house visible in the background in Beltsville, Md., in 1935. It comes from the New York Public Library.

On April 15, 1934, the worst dust storm occurred. It was later named Black Sunday. Several weeks later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed the Soil Conservation Act. It taught farmers how to plant in a more sustainable way.

Farmers Who Survived the Dust Bowl

The photo shows a farmer cultivating corn with fertilizer on a horse drawn plow at the Wabash Farms, Loogootee, Indiana, June 1938. That year, the economy contracted 3.3% because FDR cut back on the New Deal. He was trying to balance the budget, but it was too soon. Prices dropped 2.8%, hurting the farmers who were left.

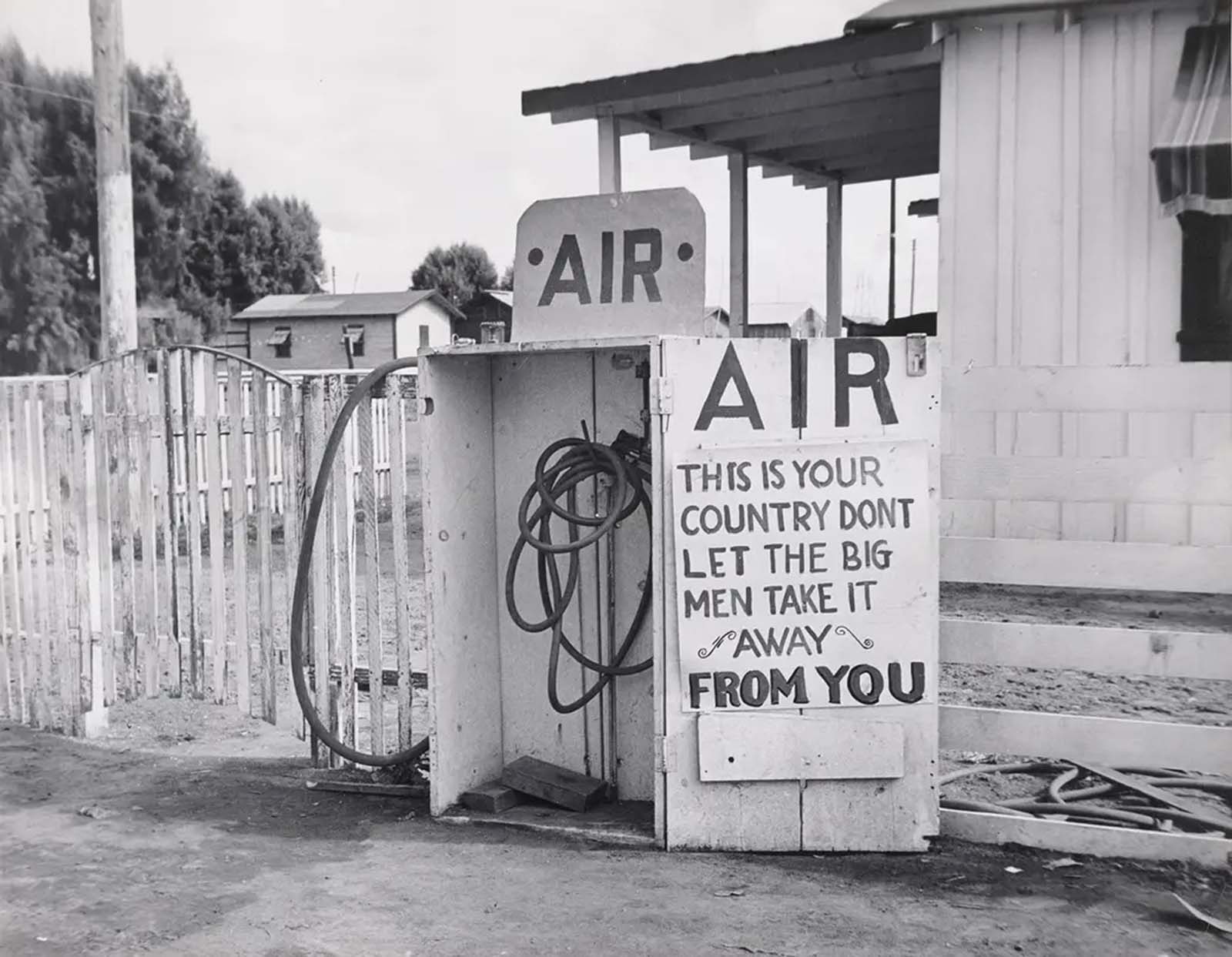

World's Greatest Standard of Living?

In March 1937, this billboard, sponsored by the National Association of Manufacturers, is displayed on Highway 99 in California during the Depression. It reads, "There's no way like the American way" and "world's highest standard of living." That year, the unemployment rate was 14.3%.

Men Were Desperate to Find Work

This photo shows two unemployed men walking towards Los Angeles, Calif., to find work.

On the Road to Find Work

The photo shows an impoverished family of nine on a New Mexico highway. The depression refugees left Iowa in 1932 due to their father's tuberculosis. He was an auto mechanic laborer and painter. The family had been on relief in Arizona.

Unemployment was 23.6%. The economy contracted 12.9%. People blamed President Herbert Hoover, who raised taxes that year to balance the budget. They voted for FDR, who promised a New Deal .

Come to California

The photo shows a roadside camp near Bakersfield, Calif., and the worldly possessions of refugees from Texas dust, drought, and depression. Many left their homes to find work in California. By the time they got there, the jobs were gone. This occurred in November 1935. Unemployment was 20.1%.

This Family Did Not Feel the Economy Improving

The photo shows a family of migrant workers fleeing from the drought in Oklahoma camp by the roadside in Blythe, Calif., on August 1, 1936. That month, Texas experienced 120 degrees, which was a record-breaking temperature.

By the end of the year, the heat wave had killed 1,693 people. Another 3,500 people drowned while trying to cool off.

The economy grew 12.9% that year. That was an incredible accomplishment, but too late to save this family's farm. Unemployment shrank to 16.9%. Prices rose 1.4%. The debt grew to $34 billion. To pay down the debt, President Roosevelt raised the top tax rate to 79%. But that proved to be a mistake. The economy wasn't strong enough to sustain higher taxes, and the Depression resumed.

Eating Along the Side of the Road

The photo shows the son of depression refugee from Oklahoma now in California taken in November 1936.

A Shanty Built of Refuse

This shanty was built of refuse near the Sunnyside slack pile in Herrin, Ill. Many residences in southern Illinois coal towns were built with money borrowed from building and loan associations, which almost all went bankrupt.

Migrant Workers in California

The photo shows a migrant worker, his young wife, and four children resting outside their temporary lodgings, situated on a migrant camp, Marysville, Calif., in 1935.

Living Out of a Car

This was the only home of a depression-routed family of nine from Iowa in August 1936.

Hooverville

Thousands of these farmers and other unemployed workers traveled to California to find work. Many ended up living as homeless “hobos” or in shantytowns called “Hoovervilles," named after then-President Herbert Hoover. Many people felt he caused the Depression by basically doing nothing to stop it. He was more concerned about balancing the budget, and felt the market would sort itself out.

Depression Family

The Great Depression displaced entire families, who became homeless. The children were most severely impacted. They often had to work to help make ends meet.

There were no social programs in the early part of the Depression. People lined up just to get a bowl of soup from a charity.

More Soup Lines

This photo shows another soup line during the Great Depression. Men this side of the sign are assured of a five-cent meal. The rest must wait for generous passersby. Buddy, can you spare a dime? The photo was taken between 1930 and 1940. There was no Social Security, welfare, or unemployment compensation until FDR and the New Deal.

Soup Kitchens Were Life Savers

Soup kitchens didn't offer much to eat, but it was better than nothing.

Even Gangsters Opened Soup Kitchens

A group of men line up outside a Chicago soup kitchen opened by Al Capone, sometime in the 1930s in this photo. In a bid to rebuild his reputation, Capone opened a soup kitchen amid the worsening economic conditions.

Soup Kitchens in 1930

Dolly Gann (L), sister of U.S. vice president Charles Curtis, helps serve meals to the hungry at a Salvation Army soup kitchen on December 27, 1930.

Effects of the Great Depression

This gentleman tried to remain well-dressed, but was forced to seek help from the Self Help Association. It was a dairy farm unit in California in 1936. Unemployment was 16.9%.

"He worked construction, but when the jobs disappeared he moved the family from Florida to his father's farm in North Georgia. On the farm, they grew a field of corn, many vegetables, apples and other fruit, and they had some livestock," according to a story from a reader.

The Faces of the Great Depression

This famous photo by Walker Evans is of Floyd Burroughs. He was from Hale County, Ala. The picture was taken in 1936.

"Fortune" magazine commissioned Walker Evans and staff writer James Agee to produce a feature on the plight of tenant farmers. They interviewed and photographed three families of cotton growers.

The magazine never published the article, but the two published " Now Let Us Praise Famous Men " in 1941.

Lucille Burroughs was Floyd's 10-year old daughter in " And Their Children After Them: The Legacy of 'Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. '" Dale Maharidge followed up on Lucille and others.

Lucille married when she was 15, and then divorced. She married again and had four children, but her husband died young.

Lucille had dreamed of becoming a teacher or a nurse. Instead, she picked cotton and waited tables. Sadly, she committed suicide in 1971. She was 45.

The Faces of the Great Depression - Migrant Mother

This woman is Florence Thompson, age 32, and the mother of five children. She was a peapicker in California. When this picture was taken by Dorothea Lange, Florence had just sold her family's home for money to buy food. The home was a tent.

In an interview available on YouTube , Florence revealed that her husband Cleo died in 1931. She picked 450 pounds of cotton a day. She moved to Modesto in 1945 and got a job in a hospital.

Children of Great Depression

The photo shows children of agricultural day laborers camped by the roadside near Spiro, Okla. There were no beds and no protection from the profusion of flies. It was taken by Russell Lee in June 1939

"For breakfast they would have cornmeal mush. For dinner, vegetables. For supper, cornbread. And they had milk at every meal. They worked hard and ate light, but they survived," a reader says.

Forced to Sell Apples

People with jobs would help out those without jobs by buying apples, pencils, or matches.

There Were No Jobs

Unemployed men are shown sitting outside waiting dinner at Robinson's soup kitchen located at 9th and Plum streets in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1931. That year, the economy contracted 6.2%, and prices dropped 9.3%. Unemployment was 15.9%, but the worst was yet to come.

Stock Market Crash of 1929

The photo shows the floor of the New York Stock Exchange right after the stock market crash of 1929 . It was a scene of total panic as stockbrokers lost all.

Stock Market Crash Destroyed Confidence in Wall Street

After "Black Thursday" at the stock market of New York, the mounted police put the excited assemblage in motion. The photograph was taken on November 2, 1929.

Ticker Tapes Couldn't Keep Up With the Sales Volume

Brokers check the tape for daily prices in a scene from the film, 'The Wolf Of Wall Street,' which opened just months before the crash in 1929.

When the Great Depression Started

President Herbert Hoover and his wife, Lou Henry Hoover, are photographed in Chicago at the final game of the 1929 World Series between the Chicago Cubs and the Philadelphia Athletics, October 1929. The Great Depression had already begun in August of that year.

Hoover Replaced by Roosevelt

President Herbert Hoover (left) is photographed with his successor Franklin D. Roosevelt at his inauguration at the U.S. Capitol on March 4, 1933.

The New Deal Programs Employed Many

The photo shows part of a fashion parade at the largest WPA sewing shop in New York where 3,000 women produce clothing and linens to be distributed among the unemployed sometime in 1935. They work a six-day, thirty-hour week on two floors of the old Siegel Cooper Building.

Could the Great Depression Reoccur?

During the Great Depression, people lost their homes and lived in tents. Could that happen in the United States again? Probably not. Congress has demonstrated it would spend whatever is necessary, regardless of the damage to the debt.

Farm Security Administration. " About This Collection ,"

- The Evolution of American Isolationism

- Decade by Decade Timeline of the 1800s

- Timeline from 1890 to 1900

- Significant Eras of the American Industrial Revolution

- The Platt Amendment and US-Cuba Relations

- The Zoot Suit Riots: Causes, Significance, and Legacy

- The Dust Bowl: The Worst Environmental Disaster in the United States

- Timeline of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

- What Was the Eisenhower Doctrine? Definition and Analysis

- Timeline of American History from 1871 to 1875

- Iran Hostage Crisis: Events, Causes, and Aftermath

- Andrew Johnson Impeachment

- The Bracero Program: When the U.S. Looked to Mexico for Labor

- The Federalist Party: America's First Political Party

- Great Disasters of the 19th Century

- What Was Jay’s Treaty?

Great Depression Project

Main pages and sections.

- BROWSE SITE CONTENT

- Video: Great Depression in Washington State

- Labor events yearbooks 1930-1939

- Brief history in chapters

- Economics and poverty

- Hoovervilles and homelessness

- Everyday life

- Strikes & unions

- Radicalism - special section

- Civil Rights and racial politics

- Public works

- Art & Culture

- Visual Arts

- Theatre Arts

- Unemployed Citizens League and poverty action

- Washington Commonwealth Federation

Select Articles

- University of Washington

- Hunger marches

- Bank crisis 1933

- Berry Lawson murder case

- Dorothea Lange Yakima photos

- Building Grand Coulee dam

- Japanese American community in early 1930s

- Jewish women in Seattle

- New Order of Cincinnatus

- Ronald Ginther watercolors

Dorothea Lange’s Social Vision: Yakima Valley in the Great Depression

By emily yoshiwara.

( Go to part two of this series on Lange)

• Dorothea Lange Photo Gallery Browse a photo gallery of Lange's 1939 photographs from the Yakima Valley.

• Culture and the Arts during the Great Depression , special section

Go to part two of our essay series on Lange: "Dorothea Lange in the Yakima Valley: Rural Poverty and Photography," by Stephanie Whitney

copyright (c) 2010, emily yoshiwara hstaa 353 fall 2009.

[1] Baldwin, Sidney. Poverty and Politics: The Rise and Decline of the Farm Security Administration . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1968. [2] Meltzer, Milton. Dorothea Lange: A Photographer's Life . New York: McGraw Hill, 1978. [3] “White Angel Bread Line” Columbia University. "Dorothea Lange: Images of the Depression." http://www.columbia.edu/cu/amstudies/resources/dorothea_lange.html . [4] Gordon, Linda. Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits . New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2009. [5] Baldwin, Poverty and Politics . [6] Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. "The Photographers: Roy E. Stryker." http://www.clpgh.org/exhibit/photog14.html. [7] Gordon, Linda. "Dorothea Lange: The Photographer as Agricultural Sociologist," Journal of American History Dec. 2006: pp 698-727.

- How to cite and copyright information

- About the project

- Contact James Gregory

Pictures That Tell Stories: Photo Essay Examples

Like any other type of artist, a photographer’s job is to tell a story through their pictures. While some of the most creative among us can invoke emotion or convey a thought with one single photo, the rest of us will rely on a photo essay.

In the following article, we’ll go into detail about what a photo essay is and how to craft one while providing some detailed photo essay examples.

What is a Photo Essay?

A photo essay is a series of photographs that, when assembled in a particular order, tell a unique and compelling story. While some photographers choose only to use pictures in their presentations, others will incorporate captions, comments, or even full paragraphs of text to provide more exposition for the scene they are unfolding.

A photo essay is a well-established part of photojournalism and have been used for decades to present a variety of information to the reader. Some of the most famous photo essayists include Ansel Adams , W. Eugene Smith, and James Nachtwey. Of course, there are thousands of photo essay examples out there from which you can draw inspiration.

Why Consider Creating a Photo Essay?

As the old saying goes, “a picture is worth 1000 words.” This adage is, for many photographers, reason enough to hold a photo essay in particularly high regard.

For others, a photo essay allow them to take pictures that are already interesting and construct intricate, emotionally-charged tales out of them. For all photographers, it is yet another skill they can master to become better at their craft.

As you might expect, the photo essay have had a long history of being associated with photojournalism. From the Great Depression to Civil Rights Marches and beyond, many compelling stories have been told through a combination of images and text, or photos alone. A photo essay often evokes an intense reaction, whether artistic in nature or designed to prove a socio-political point.

Below, we’ll list some famous photo essay samples to further illustrate the subject.

Become the photographer you were born to be.

Join Cole’s Classroom

Famous Photo Essays

“The Great Depression” by Dorothea Lange – Shot and arranged in the 1930s, this famous photo essay still serves as a stark reminder of The Great Depression and Dust Bowl America . Beautifully photographed, the black and white images offer a bleak insight to one of the country’s most difficult times.

“The Vietnam War” by Philip Jones Griffiths – Many artists consider the Griffiths’ photo essay works to be some of the most important records of the war in Vietnam. His photographs and great photo essays are particularly well-remembered for going against public opinion and showing the suffering of the “other side,” a novel concept when it came to war photography.

Various American Natural Sites by Ansel Adams – Adams bought the beauty of nature home to millions, photographing the American Southwest and places like Yosemite National Park in a way that made the photos seem huge, imposing, and beautiful.

“Everyday” by Noah Kalina – Is a series of photographs arranged into a video. This photo essay features daily photographs of the artist himself, who began taking capturing the images when he was 19 and continued to do so for six years.

“Signed, X” by Kate Ryan – This is a powerful photo essay put together to show the long-term effects of sexual violence and assault. This photo essay is special in that it remains ongoing, with more subjects being added every year.

Common Types of Photo Essays

While a photo essay do not have to conform to any specific format or design, there are two “umbrella terms” under which almost all genres of photo essays tend to fall. A photo essay is thematic and narrative. In the following section, we’ll give some details about the differences between the two types, and then cover some common genres used by many artists.

⬥ Thematic

A thematic photo essay speak on a specific subject. For instance, numerous photo essays were put together in the 1930s to capture the ruin of The Great Depression. Though some of these presentations followed specific people or families, they mostly told the “story” of the entire event. There is much more freedom with a thematic photo essay, and you can utilize numerous locations and subjects. Text is less common with these types of presentations.

⬥ Narrative

A narrative photo essay is much more specific than thematic essays, and they tend to tell a much more direct story. For instance, rather than show a number of scenes from a Great Depression Era town, the photographer might show the daily life of a person living in Dust Bowl America. There are few rules about how broad or narrow the scope needs to be, so photographers have endless creative freedom. These types of works frequently utilize text.

Common Photo Essay Genres

Walk a City – This photo essay is when you schedule a time to walk around a city, neighborhood, or natural site with the sole goal of taking photos. Usually thematic in nature, this type of photo essay allows you to capture a specific place, it’s energy, and its moods and then pass them along to others.

The Relationship Photo Essay – The interaction between families and loved ones if often a fascinating topic for a photo essay. This photo essay genre, in particular, gives photographers an excellent opportunity to capture complex emotions like love and abstract concepts like friendship. When paired with introspective text, the results can be quite stunning.

The Timelapse Transformation Photo Essay – The goal of a transformation photo essay is to capture the way a subject changes over time. Some people take years or even decades putting together a transformation photo essay, with subjects ranging from people to buildings to trees to particular areas of a city.

Going Behind The Scenes Photo Essay – Many people are fascinated by what goes on behind the scenes of big events. Providing the photographer can get access; to an education photo essay can tell a very unique and compelling story to their viewers with this photo essay.

Photo Essay of a Special Event – There are always events and occasions going on that would make an interesting subject for a photo essay. Ideas for this photo essay include concerts, block parties, graduations, marches, and protests. Images from some of the latter were integral to the popularity of great photo essays.

The Daily Life Photo Essay – This type of photo essay often focus on a single subject and attempt to show “a day in the life” of that person or object through the photographs. This type of photo essay can be quite powerful depending on the subject matter and invoke many feelings in the people who view them.

Become the photographer of your dreams with Cole’s Classroom.

Start Free Trial

Photo Essay Ideas and Examples

One of the best ways to gain a better understanding of photo essays is to view some photo essay samples. If you take the time to study these executions in detail, you’ll see just how photo essays can make you a better photographer and offer you a better “voice” with which to speak to your audience.

Some of these photo essay ideas we’ve already touched on briefly, while others will be completely new to you.

Cover a Protest or March

Some of the best photo essay examples come from marches, protests, and other events associated with movements or socio-political statements. Such events allow you to take pictures of angry, happy, or otherwise empowered individuals in high-energy settings. The photo essay narrative can also be further enhanced by arriving early or staying long after the protest has ended to catch contrasting images.

Photograph a Local Event

Whether you know it or not, countless unique and interesting events are happening in and around your town this year. Such events provide photographers new opportunities to put together a compelling photo essay. From ethnic festivals to historical events to food and beverage celebrations, there are many different ways to capture and celebrate local life.

Visit an Abandoned Site or Building

Old homes and historical sites are rich with detail and can sometimes appear dilapidated, overgrown by weeds, or broken down by time. These qualities make them a dynamic and exciting subject. Many great photo essay works of abandoned homes use a mix of far-away shots, close-ups, weird angles, and unique lighting. Such techniques help set a mood that the audience can feel through the photographic essay.

Chronicle a Pregnancy

Few photo essay topics could be more personal than telling the story of a pregnancy. Though this photo essay example can require some preparation and will take a lot of time, the results of a photographic essay like this are usually extremely emotionally-charged and touching. In some cases, photographers will continue the photo essay project as the child grows as well.

Photograph Unique Lifestyles

People all over the world are embracing society’s changes in different ways. People live in vans or in “tiny houses,” living in the woods miles away from everyone else, and others are growing food on self-sustaining farms. Some of the best photo essay works have been born out of these new, inspiring movements.

Photograph Animals or Pets

If you have a favorite animal (or one that you know very little about), you might want to arrange a way to see it up close and tell its story through images. You can take photos like this in a zoo or the animal’s natural habitat, depending on the type of animal you choose. Pets are another great topic for a photo essay and are among the most popular subjects for many photographers.

Show Body Positive Themes

So much of modern photography is about showing the best looking, prettiest, or sexiest people at all times. Choosing a photo essay theme like body positivity, however, allows you to film a wide range of interesting-looking people from all walks of life.

Such a photo essay theme doesn’t just apply to women, as beauty can be found everywhere. As a photo essay photographer, it’s your job to find it!

Bring Social Issues to Life

Some of the most impactful social photo essay examples are those where the photographer focuses on social issues. From discrimination to domestic violence to the injustices of the prison system, there are many ways that a creative photographer can highlight what’s wrong with the world. This type of photo essay can be incredibly powerful when paired with compelling subjects and some basic text.

Photograph Style and Fashion

If you live in or know of a particularly stylish locale or area, you can put together an excellent thematic photo essay by capturing impromptu shots of well-dressed people as they pass by. As with culture, style is easily identifiable and is as unifying as it is divisive. Great photo essay examples include people who’ve covered fashion sub-genres from all over the world, like urban hip hop or Japanese Visual Kei.

Photograph Native Cultures and Traditions

If you’ve ever opened up a copy of National Geographic, you’ve probably seen photo essay photos that fit this category. To many, the traditions, dress, religious ceremonies, and celebrations of native peoples and foreign cultures can be utterly captivating. For travel photographers, this photo essay is considered one of the best ways to tell a story with or without text.

Capture Seasonal Or Time Changes In A Landmark Photo Essay

Time-lapse photography is very compelling to most viewers. What they do in a few hours, however, others are doing over months, years, and even decades. If you know of an exciting landscape or scene, you can try to capture the same image in Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall, and put that all together into one landmark photo essay.

Alternatively, you can photograph something being lost or ravaged by time or weather. The subject of your landmark photo essay can be as simple as the wall of an old building or as complex as an old house in the woods being taken over by nature. As always, there are countless transformation-based landmark photo essay works from which you can draw inspiration.

Photograph Humanitarian Efforts or Charity

Humanitarian efforts by groups like Habitat for Humanity, the Red Cross, and Doctors Without Borders can invoke a powerful response through even the simplest of photos. While it can be hard to put yourself in a position to get the images, there are countless photo essay examples to serve as inspiration for your photo essay project.

How to Create a Photo Essay

There is no singular way to create a photo essay. As it is, ultimately, and artistic expression of the photographer, there is no right, wrong, good, or bad. However, like all stories, some tell them well and those who do not. Luckily, as with all things, practice does make perfect. Below, we’ve listed some basic steps outlining how to create a photo essay

Steps To Create A Photo Essay

Choose Your Topic – While some photo essayists will be able to “happen upon” a photo story and turn it into something compelling, most will want to choose their photo essay topics ahead of time. While the genres listed above should provide a great starting place, it’s essential to understand that photo essay topics can cover any event or occasion and any span of time

Do Some Research – The next step to creating a photo essay is to do some basic research. Examples could include learning the history of the area you’re shooting or the background of the person you photograph. If you’re photographing a new event, consider learning the story behind it. Doing so will give you ideas on what to look for when you’re shooting.

Make a Storyboard – Storyboards are incredibly useful tools when you’re still in the process of deciding what photo story you want to tell. By laying out your ideas shot by shot, or even doing rough illustrations of what you’re trying to capture, you can prepare your photo story before you head out to take your photos.

This process is especially important if you have little to no control over your chosen subject. People who are participating in a march or protest, for instance, aren’t going to wait for you to get in position before offering up the perfect shot. You need to know what you’re looking for and be prepared to get it.

Get the Right Images – If you have a shot list or storyboard, you’ll be well-prepared to take on your photo essay. Make sure you give yourself enough time (where applicable) and take plenty of photos, so you have a lot from which to choose. It would also be a good idea to explore the area, show up early, and stay late. You never know when an idea might strike you.

Assemble Your Story – Once you develop or organize your photos on your computer, you need to choose the pictures that tell the most compelling photo story or stories. You might also find some great images that don’t fit your photo story These can still find a place in your portfolio, however, or perhaps a completely different photo essay you create later.

Depending on the type of photographer you are, you might choose to crop or digitally edit some of your photos to enhance the emotions they invoke. Doing so is completely at your discretion, but worth considering if you feel you can improve upon the naked image.

Ready to take your photography to the next level?

Join Cole’s Classroom today! »

Best Photo Essays Tips And Tricks

Before you approach the art of photo essaying for the first time, you might want to consider with these photo essay examples some techniques, tips, and tricks that can make your session more fun and your final results more interesting. Below, we’ve compiled a list of some of the best advice we could find on the subject of photo essays.

⬥ Experiment All You Want

You can, and should, plan your topic and your theme with as much attention to detail as possible. That said, some of the best photo essay examples come to us from photographers that got caught up in the moment and decided to experiment in different ways. Ideas for experimentation include the following:

Angles – Citizen Kane is still revered today for the unique, dramatic angles used in the film. Though that was a motion picture and not photography, the same basic principles still apply. Don’t be afraid to photograph some different angles to see how they bring your subject to life in different ways.

Color – Some images have more gravitas in black in white or sepia tone. You can say the same for images that use color in an engaging, dynamic way. You always have room to experiment with color, both before and after the shoot.

Contrast – Dark and light, happy and sad, rich and poor – contrast is an instantly recognizable form of tension that you can easily include in your photo essay. In some cases, you can plan for dramatic contrasts. In other cases, you simply need to keep your eyes open.

Exposure Settings – You can play with light in terms of exposure as well, setting a number of different moods in the resulting photos. Some photographers even do random double exposures to create a photo essay that’s original.

Filters – There are endless post-production options available to photographers, particularly if they use digital cameras. Using different programs and apps, you can completely alter the look and feel of your image, changing it from warm to cool or altering dozens of different settings.

Want to never run out of natural & authentic poses? You need this ⬇️

Click here & get it today for a huge discount., ⬥ take more photos than you need .

If you’re using traditional film instead of a digital camera, you’re going to want to stock up. Getting the right shots for a photo essay usually involves taking hundreds of images that will end up in the rubbish bin. Taking extra pictures you won’t use is just the nature of the photography process. Luckily, there’s nothing better than coming home to realize that you managed to capture that one, perfect photograph.

⬥ Set the Scene

You’re not just telling a story to your audience – you’re writing it as well. If the scene you want to capture doesn’t have the look you want, don’t be afraid to move things around until it does. While this doesn’t often apply to photographing events that you have no control over, you shouldn’t be afraid to take a second to make an OK shot a great shot.

⬥ Capture Now, Edit Later

Editing, cropping, and digital effects can add a lot of drama and artistic flair to your photos. That said, you shouldn’t waste time on a shoot, thinking about how you can edit it later. Instead, make sure you’re capturing everything that you want and not missing out on any unique pictures. If you need to make changes later, you’ll have plenty of time!

⬥ Make It Fun

As photographers, we know that taking pictures is part art, part skill, and part performance. If you want to take the best photo essays, you need to loosen up and have fun. Again, you’ll want to plan for your topic as best as you can, but don’t be afraid to lose yourself in the experience. Once you let yourself relax, both the ideas and the opportunities will manifest.

⬥ It’s All in The Details

When someone puts out a photographic essay for an audience, that work usually gets analyzed with great attention to detail. You need to apply this same level of scrutiny to the shots you choose to include in your photo essay. If something is out of place or (in the case of historical work) out of time, you can bet the audience will notice.

⬥ Consider Adding Text

While it isn’t necessary, a photographic essay can be more powerful by the addition of text. This is especially true of images with an interesting background story that can’t be conveyed through the image alone. If you don’t feel up to the task of writing content, consider partnering with another artist and allowing them tor bring your work to life.

Final Thoughts

The world is waiting to tell us story after story. Through the best photo essays, we can capture the elements of those stories and create a photo essay that can invoke a variety of emotions in our audience.

No matter the type of cameras we choose, the techniques we embrace, or the topics we select, what really matters is that the photos say something about the people, objects, and events that make our world wonderful.

Dream of Being a Pro Photographer?

Join Cole’s Classroom today to make it a reality.

Similar Posts

The Ultimate Guide to Better Forest Photography Pictures

If you’ve ever tried taking pictures in the woods, you already probably know how difficult forest photography can be to master. The normal “rules” or procedures that come with nature photography don’t apply, which can make this genre even more challenging. Whether you’re an amateur or an expert, here’s what you should know about forest…

Sunset Photography – The Guide to Perfect Golden Hour Pictures

“Why don’t my sunset photos look like what I saw that day?” Among all levels of photographers, taking gorgeous sunset photos can sometimes be challenging. We want to know how to take advantage of “The Gold Hour” to capture sunset pictures and sunrise images too. What type of digital cameras are used, what shutter speed,…

Using Your Integrated Light Meter, Part Two: Metering Modes

In the first portion of this blog series I discussed how to obtain correct exposure in your camera by following the guidelines of your integrated light meter on your DSLR. Today we will take the process one step further by metering isolated areas of your photo, and discussing the various metering modes. The previous metering…

What is Photo Aspect Ratio and Definition? It’s Not as Difficult as you Think!

Have you found yourself wondering: What the heck is aspect ratio? You’re not alone. Aspect ratio a fundamental digital photography concept that can be quite confusing at first. Chances are, you’ve seen numbers representing common aspect ratios, including: 1:1 3:2 4:3 5:4 7:5 8.5:11 16:9 What do these numbers mean? And how can they make a…

Photography Tips to Make Ugly Locations Look Amazing!

Stuck with the muck? Here are some photography tips for making ugly locations look amazing! One of the most iconic images from my home state of Wyoming is the T.A. Moulton Barn. If you’re a fan of landscape photography, I’m sure you’ve seen an image of it. There are about 8.98 million images of it…

Detailed Tips for Improving Your Car Photography

Even though it may look like a simple task to photograph a car, there are many technical considerations to keep in mind. If you want to take the perfect picture of car, you will need to think about shutter speed, location, light, background, and much more. Keep reading for tips that will help you develop…

The Art of the Great Depression

Since 2020 Americans have lived through extraordinary sociopolitical events: Black Lives Matter protests erupted across the country in response to the murder of George Floyd; far-right activists stormed the Capitol, incited by Donald Trump’s false claim that the presidential election had been stolen from him; labor organizers Chris Smalls and Derrick Palmer achieved the seemingly impossible task of establishing a union for warehouse workers at the corporate juggernaut Amazon; and Joe Biden’s administration passed the largest federal climate legislation in the country’s history—all while COVID-19 upended millions of lives across the United States.

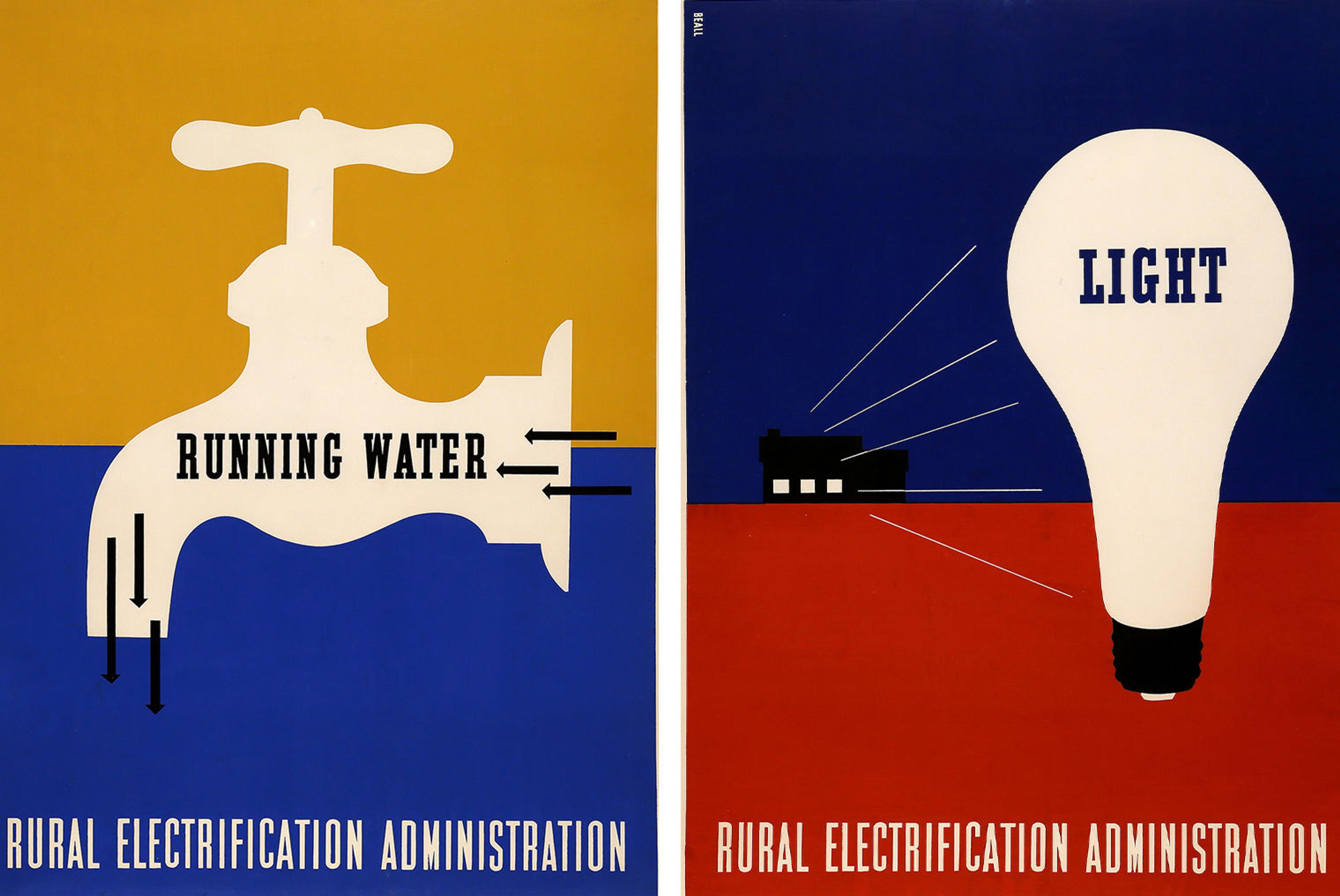

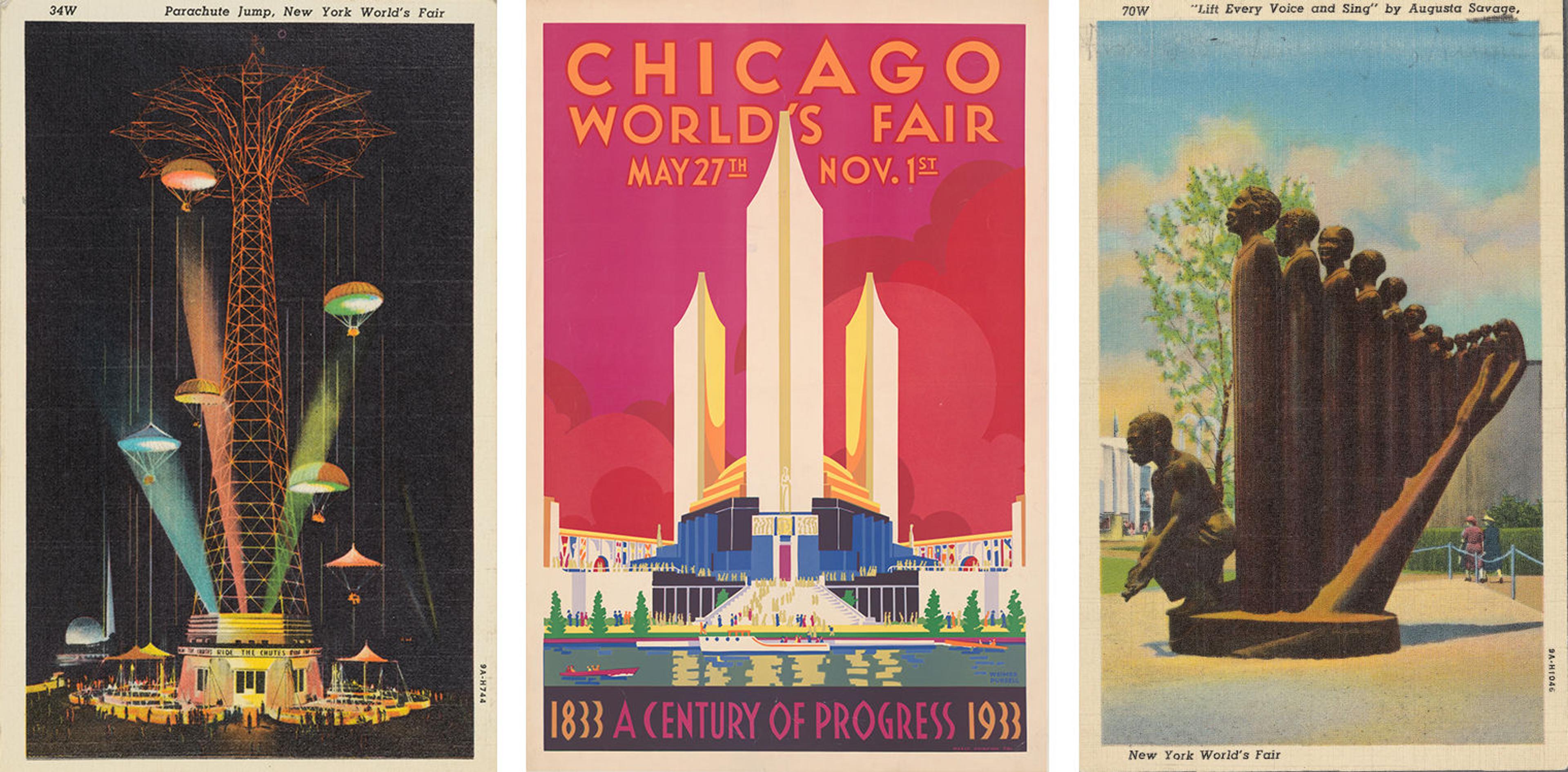

Though these circumstances might feel unprecedented, in many ways they mirror the conditions that characterized the 1930s. The decade was defined by the Great Depression, which resulted from the stock market crash of 1929—the worst crisis the nation had experienced since the Civil War. While American visual culture has always been suffused with ideology, cultural production in the 1930s represents an exceptional range of political messaging. Widely circulated prints, posters, and magazine illustrations advocated for labor unions and communist and socialist causes; propaganda for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s controversial New Deal solicited support for its relief programs, which were designed to revive the economy; and several world’s fairs communicated values of technological innovation, American imperialism, and capitalism through the work of architects and designers.

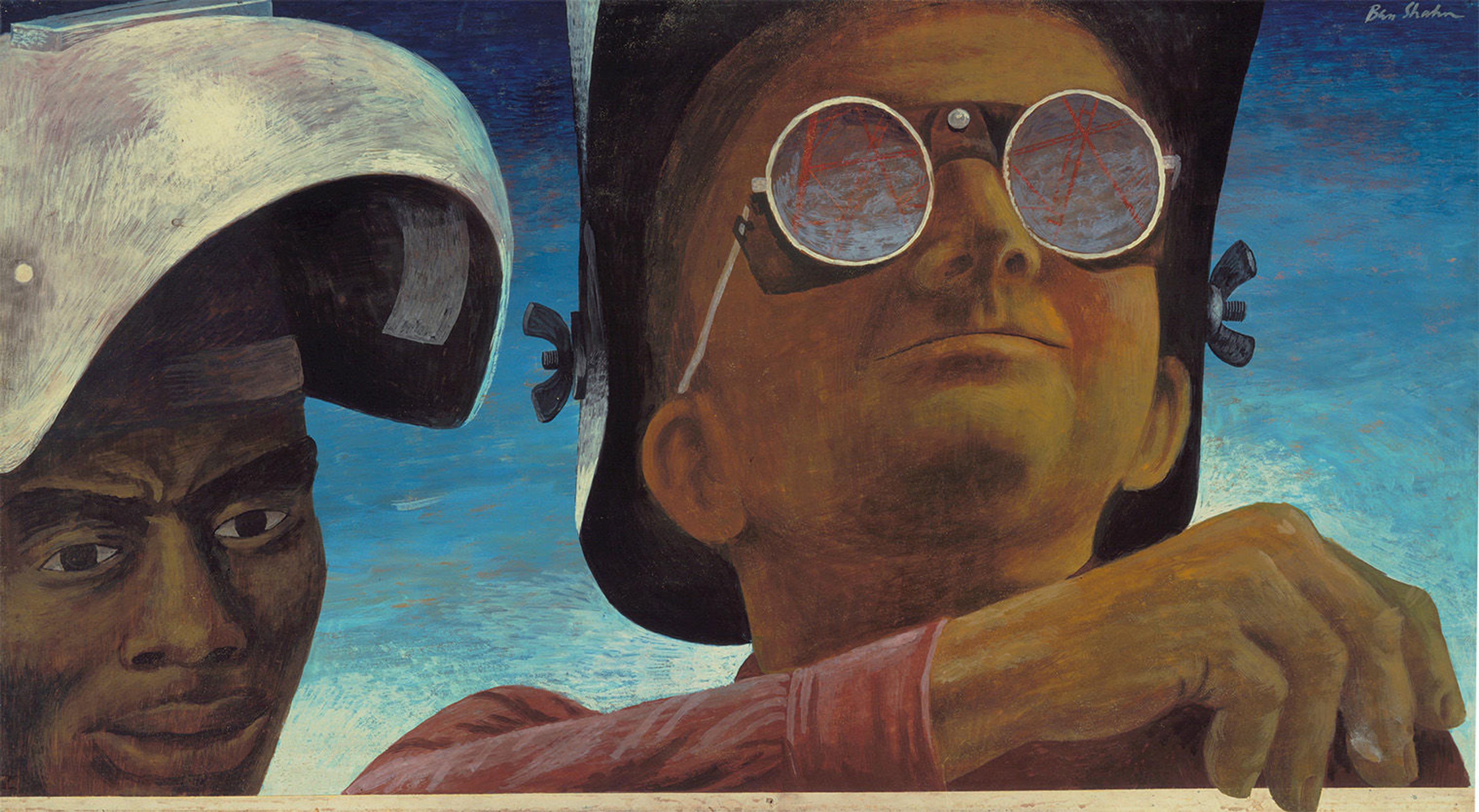

Ben Shahn (American, born Lithuania, 1898–1969). Welders , 1943. Gouache on board, 22 × 393/4 in. (55.9 × 101 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Purchase, 1944

The Works Progress Administration (WPA)—a New Deal agency established in 1935 to bring jobs to the unemployed, including artists—aimed to make and distribute “art for the millions” in order to engineer a more cultured, educated, and refined citizenry. While the exact number of people who encountered the art of the WPA is impossible to measure, it is unquestionable that millions of Americans consumed an array of complex and conflicting political messages between the output of the agency and the broader visual world around them.

Leftist Politics and Labor

At the height of the Depression in 1933, nearly 13 million people—roughly 25 percent of the total workforce—were unemployed. This dire situation ignited a militant labor movement led by organizers with left-leaning politics who drew attention to low pay and harsh working conditions. Artists across the country centered the plight of the proletariat in their work and joined activist groups associated with the American Communist Party (CPUSA) that advocated for better protections for workers.

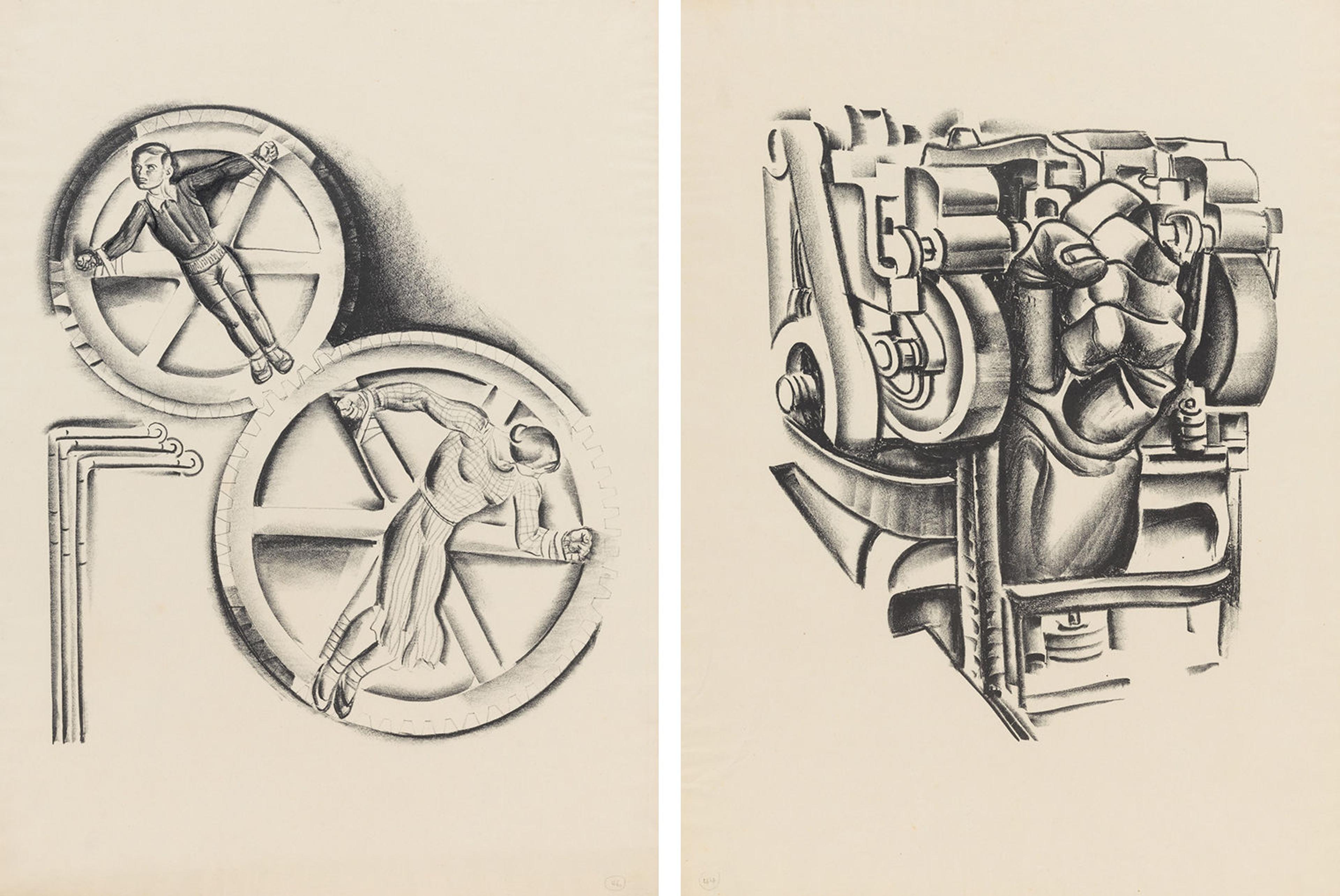

Some artists—particularly a loose group known as the Precisionists , working primarily before the stock market crash—treated industrial machinery and the plants that housed them as objects of fascination and wonder. After the onset of the economic downturn, however, wage workers were placed front and center. Images that pitted industrial machines against people invoked Karl Marx’s theory of exploitation under capitalism, as in communist artist Hugo Gellert’s illustrations for a condensed 1934 edition of Das Kapital . In one, a woman and a young boy are bound at the wrists to oversize cogs in a scene that conjures the Crucifixion, with the vulnerable sacrificed in the name of capitalism. In another, a muscular fist breaks through a mass of mechanical parts, conquering the machine-enemy.

Left: Hugo Gellert (American, born Hungary, 1892–1985). Machinery and Large Scale Industry 46 , 1933. Lithograph, 201/4 × 15 in. (51.4 × 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Abner and Miriam Diamond, 1998 (1998.392.5). Right: Hugo Gellert (American, born Hungary, 1892–1985). Machinery and Large Scale Industry 44 , 1933. Lithograph, 201/4 × 15 in. (51.4 × 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Abner and Miriam Diamond, 1998 (1998.392.4)

Tens of thousands of artists found work through the Federal Art Project (FAP) and related initiatives that operated under the aegis of the WPA. Communal WPA workshops cropped up across the country, where workshop instructors introduced legions of artists to printmaking. The public encountered these prints at WPA-organized exhibitions, and, as official government property, they were donated to or placed on long-term loan at various museums, libraries, and other public institutions across the United States after the close of the WPA in the early 1940s.

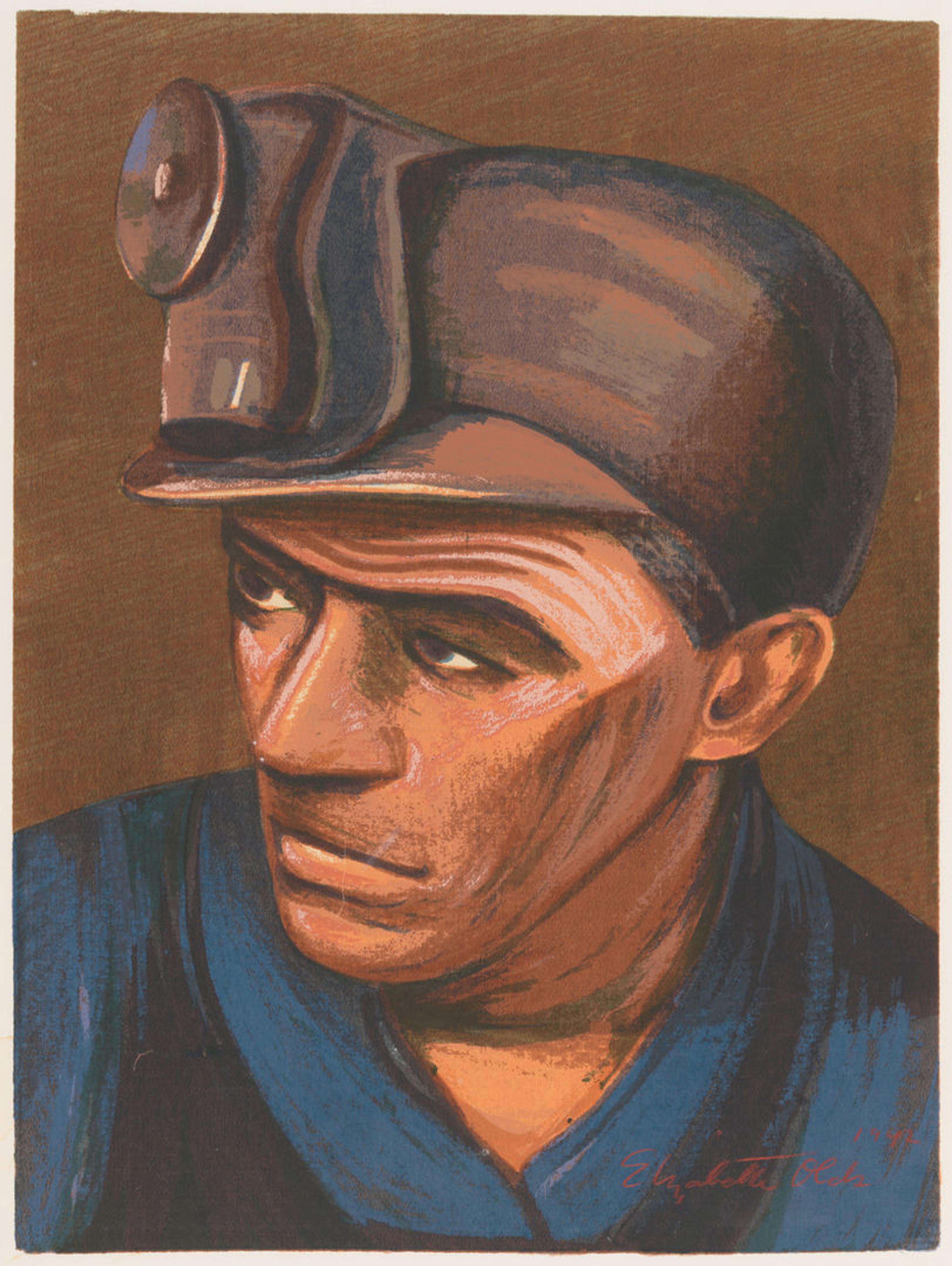

Printmaking became the medium of choice among activist artists due in large part to its capacity for producing multiple impressions of the same image, enabling them to disseminate their political messages to a broader audience. Many WPA prints featured idealized images of people at work and engaged the accessible style and sociopolitical subject matter of social realism. One powerful example is Elizabeth Olds’s screenprint Miner Joe (1942), which depicts a lone figure in a helmet and overalls from the chest up, his head tilted slightly against a bare background. Olds’s focused treatment imbues her subject with an air of dignity and valor.

Elizabeth Olds (American, 1896–1991). Miner Joe , 1942. Screenprint 183/4 × 123/4 in. (47.6 × 32.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Accession, transferred from the Lending Library Collection (64.500.1)

While women and people of color often faced barriers in hiring, visibility, and equal treatment in the art world, the WPA provided many with unprecedented access to art-making and exhibition opportunities. Though aspects of the hiring practices and management of the FAP were also undoubtedly discriminatory, its top administrators made efforts to establish egalitarian environments that could be held up as evidence of its alignment with the Roosevelt administration’s democratic values. Jacob Lawrence spoke fondly of the progress made for artists in the 1930s decades later, at a roundtable discussion titled “ The Black Artist in America ” convened at The Met in response to the backlash against its controversial 1968 exhibition Harlem on My Mind . He described it as a time when “we’ll find that some of the greatest progress, economic, professional, and so on, was made . . . by the greatest number of artists—not only Negro artists but white ones as well. The greatest exposure for the greatest number of people came during this period of government involvement in the arts.”

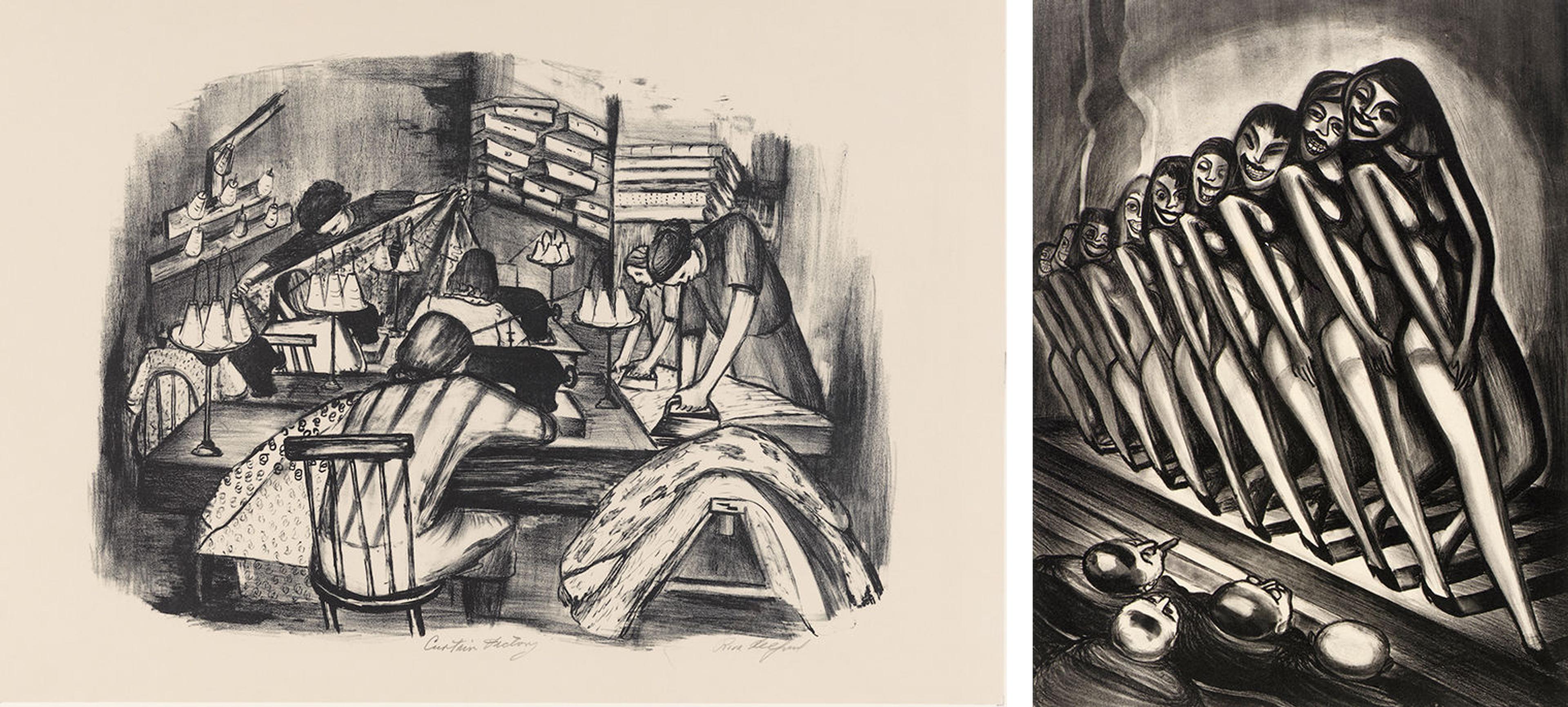

Despite the increased presence of women in the arts, images focusing on women’s paid labor were scarce. Riva Helfond was a seasoned printmaker when she joined the WPA, first as an instructor at the Harlem Community Art Center and later as an artist in the Graphic Arts Division of the New York City FAP. Her print Curtain Factory (ca. 1936–39), which depicts fatigued workers, is a rare example. She had worked in textile factories and experienced firsthand the physical strain of the work, conveyed here through the downward curves of the workers’ bodies. Although scenes of women performing in cabarets and clubs were common, few artists approached them from the perspective of feminized labor. One exception is Olds, whose Burlesque (1936) presents the bodies of female performers on stage in a serialized formation that conjures an assembly line while male viewers gaze longingly from below.

Left: Riva Helfond (American, 1910–2002). Curtain Factory , ca. 1936–39 Lithograph, 141/4 × 201/2 in. (36.2 × 52.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City WPA, 1943 (43.33.694). Right: Elizabeth Olds (American, 1896–1991). Burlesque , 1936. Lithograph, 141/2 × 1013/16 in. (36.8 × 27.4 cm) Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the Lola Downin Peck Fund from the Carl and Laura Zigrosser Collection, 1981

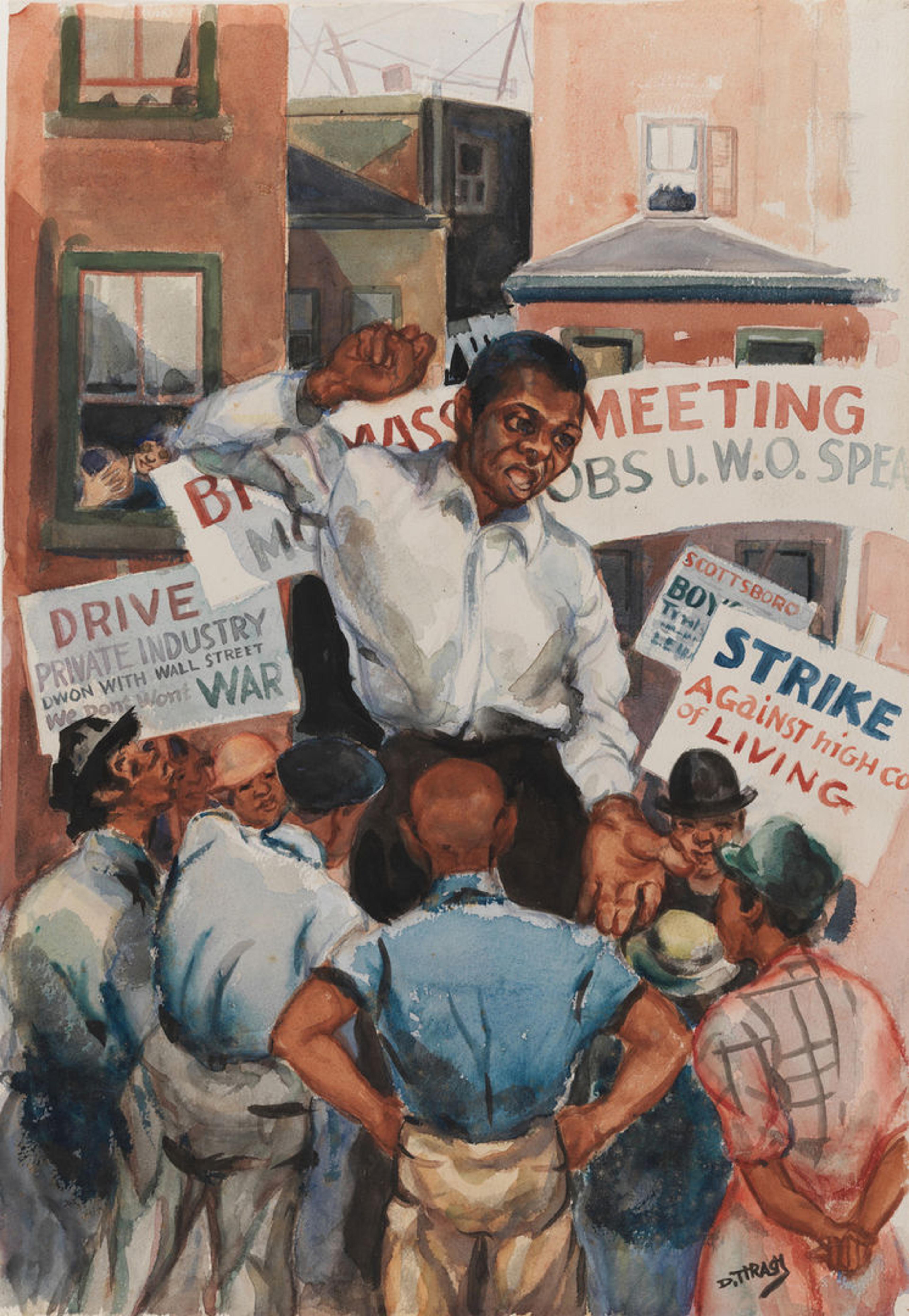

While laborers of color were frequently depicted alongside white ones in prints by white artists, prints centering workers of color are rare. One reason for this scarcity likely relates to the persistence of racial discrimination in the workforce and the labor unions that emerged as a major presence in the thirties. Workers of color came up against numerous barriers, from discriminatory hiring processes to being denied adequate training or educational opportunities; they were also often denied union membership. Dox Thrash, one of the era’s most prominent and innovative Black printmakers, was characterized as staunchly anti-union by his fellow workshop artist Claude Clark. But Thrash also experienced the effects of labor discrimination throughout his career, having been shut out of so-called skilled positions until he was employed by the FAP—experiences that might have reinforced his opposition to the labor movement.

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Untitled (Strike) , ca. 1940. Watercolor, 171/8 in. × 12 in. (43.5 × 30.5 cm). Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Museum Purchase

Whatever his political leanings, Thrash depicted scenes of leftist activity, as in Untitled (Strike) (ca. 1940), a watercolor rendering of a Black organizer surrounded by a crowd of figures carrying protest signs. A placard to the organizer’s left references the landmark Scottsboro Boys trial, in which nine Black youths were falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. To his right, a man and a woman peer out of the window of a nearby building; the woman laughs as she looks toward the man, who covers his face with his hand—a gesture that may have reflected Thrash’s own feelings toward the labor strike.

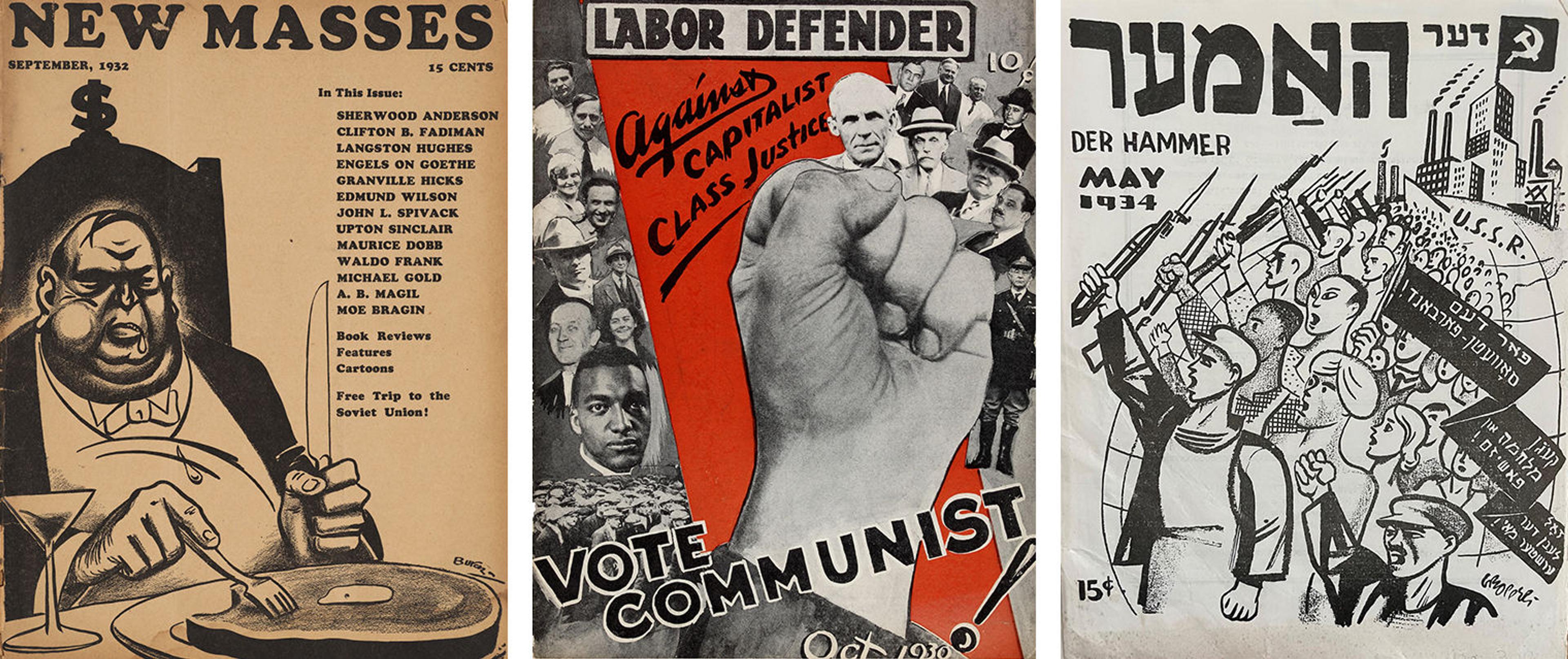

Communist newspapers, magazines, and journals offered artists opportunities to advance their messaging through vivid illustrations. The communist periodical New Masses incorporated the visual arts in its pages more than any other leftist publication of the period; in addition to political cartoons and drawings, the magazine reproduced social realist prints and paintings whose themes were aligned with its messaging. One particularly memorable cover by Jacob Burck presents a caricature of a capitalist—an embodiment of the worker’s opposition—who drools onto his rounded stomach as he prepares to consume a large steak and a martini, signaling the radicals’ association of capitalism with gluttony and greed. From 1929 to 1931 the masthead credited the artists alongside the writers as “contributing editors,” with prominent figures such as Stuart Davis, Adolf Dehn, Gellert, Louis Lozowick, and John Sloan helping to shape the magazine’s content.

Left: Cover by Jacob Burck (American, born Poland, 1904–1982). New Masses , September 1932 . Photomechanical relief print, 111/2 × 83/4 in. (29.2 × 22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of Drawings and Prints Gifts, 2022 (2022.120). Middle: Labor Defender , October 1930. Photomechanical relief print, 121/8 × 91/8 in. (30.8 × 23.2 cm). Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Right: Cover by William Gropper (American, 1897–1977). Der Hammer , May 1934 . Photomechanical relief print, 9 15/16 × 7 5/8 in. (25.2 × 19.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2023 (2023.188)

New York, where New Masses and other prominent communist publications were based, was home to a thriving community of Yiddish-speaking Jews with leftist political leanings. The monthly magazine Der Hammer (“The Hammer”) often featured political cartoons by William Gropper, a Jewish artist born to Romanian and Ukrainian immigrants. Gropper was instrumental in forging a graphic, easily legible style that celebrated the proletariat and condemned capitalism—often equating it with fascism—in illustrations targeted at a Yiddish-speaking audience. For radical artists such as Gropper, the press served as a vital means for the dissemination of their work, enabling it to reach a larger public beyond the confines of museum and gallery walls.

Cultural Nationalism(s)

For many facing unprecedented hardship, their American identity offered solace and provided a sense of belonging and pride in democracy. In the cultural sector, this wave of nationalism took the form of a question: What exactly is “American” about American art? Artists and other cultural practitioners sought to define the contours of an art tradition that was specific to the United States and distinguished from that of anywhere else—particularly Europe. Paintings, sculptures, photographs, prints, dances, films, garments, and decorative art objects evoked the American landscape, depicted themes from the country’s history, and reflected the traditions of the innumerable ethnicities represented in the population.

Modernist artists sought inspiration in craft traditions of the United States in order to create a distinctly American mode of art. Charles Sheeler was an avid collector of antique American furniture, which he began incorporating into his paintings beginning in the late 1920s. In Americana (1931), one in a series of seven paintings depicting the interior of his home in South Salem, New York, Sheeler harnessed and accentuated the pared-down, minimalist designs of his furniture to create a modernist composition marrying flat, unmodulated planes of color with striking abstract patterns.

Charles Sheeler (American, 1883–1965). Americana , 1931. Oil on canvas, 48 × 36 in (121.9 × 91.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edith and Milton Lowenthal Collection, Bequest of Edith Abrahamson Lowenthal, 1991 (1992.24.8)

Georgia O’Keeffe similarly looked to craft traditions of the United States while living in northern New Mexico. Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue (1931), one of the first of numerous paintings based on animal bones the artist encountered and collected in the region, contains several references to the Indigenous peoples of the Southwest. The cow skull resembles the animal masks worn by the Pueblo people in ceremonial dances; its protruding horns also recall the crosses that decorate the Hispano Catholic churches of northern New Mexico. The abstracted, undulating composition conjures Navajo blankets found throughout the region, and the color palette evokes the American flag—explicitly connecting the practices and products of the Indigenous cultures of the Southwest to an American art tradition.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887–1986). Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue , 1931. Oil on canvas, 397/8 × 357/8 in. (101.3 × 91.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1952 (52.203)

While O’Keeffe’s paintings were firmly grounded in the cultures of northern New Mexico, the lack of figures and concrete references to the region’s inhabitants, coupled with the artist’s “priestess of the desert” persona, perpetuated the idea that the Southwest was an untouched, secluded region. Scholar Patricia Marroquin Norby attributes this perception to the omission of the experiences of O’Keeffe’s Native American and Hispano neighbors in her work, despite career success predicated on their contributions and support. Read within this context, the merging of Indigenous Southwest and nationalist American identities performed in Cow’s Skull points to the ways in which the search for an “authentic” national arts tradition often occluded the perspectives of marginalized groups.

What exactly is “American” about American art?Several Indigenous artists from New Mexico did attain acclaim and monetary success during the 1930s. Arguably the best known was Tonita Peña (Quah Ah in her native Tewa), who was born in San Ildefonso Pueblo and moved to Cochiti Pueblo to live with her aunt and uncle, both pottery artists. An enterprising artist, she created hundreds of genre paintings for the art market, focusing on Pueblo dances that were open to the public. The precision and detail enabled by watercolor and gouache—techniques that gained popularity among contemporary Pueblo artists during the late 1920s and early 1930s—endowed Peña’s paintings with a documentary style that reinforced their appearance as records of observed events. The untouched background of Pueblo Parrot Dance (ca. 1935) is a common compositional strategy in the artist’s paintings that draws focus to the figures. As scholars have recently suggested, it might also be a representational tactic related to a specific understanding of the world. When a dance is performed, the sacred site of the dance and the landscape that surrounds it is activated; by leaving the backgrounds blank, Peña essentially neutralized the space that the figures occupy, reflecting her adherence to Pueblo values.

Tonita Peña (Quah Ah; Cochiti Pueblo, born San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1893–1949). Pueblo Parrot Dance , ca. 1935 Gouache over graphite on wove paper, 14 × 22 in. (35.6 × 55.9 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Corcoran Collection, Gift of Amelia E. White. Published with the permission of Joe Herrera Jr. on behalf of the Peña family

Another successful Pueblo artist of the period was Velino Shije Herrera (Ma Pe Wi), from Zia Pueblo, who was hired by the School of American Research in Santa Fe to create paintings of Pueblo ceremonies. Along with Peña, he became a major figure in the development of the watercolor movement, creating works that feature Pueblo subjects in which the figures—for instance, men on horseback hunting deer—are rendered in meticulous detail against a neutral background. Peña and Herrera exemplify the negotiations many Native American artists made between adhering to longstanding modes of art production and adapting aspects of their practices to appeal to the tastes of European American collectors during the 1930s.

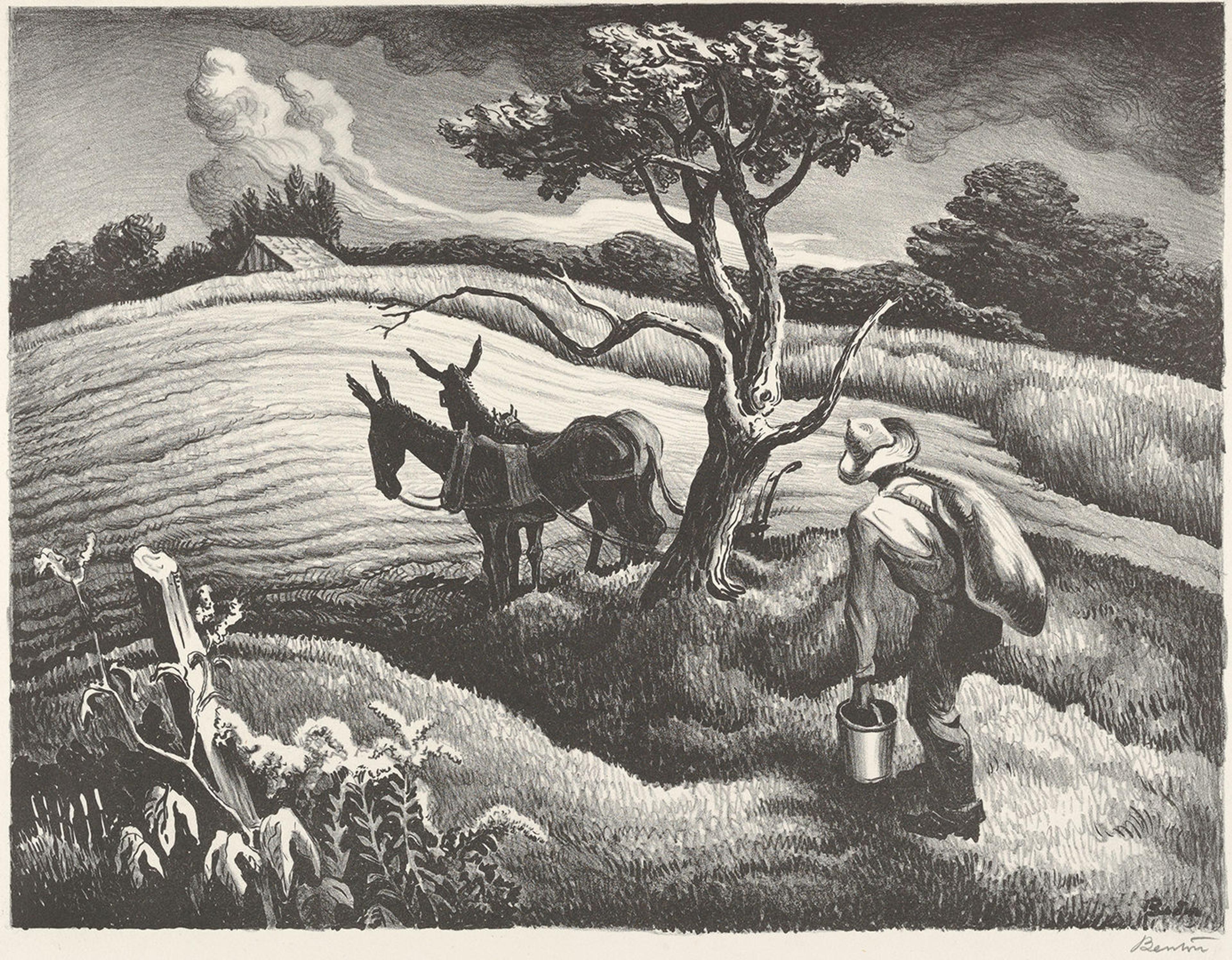

The interest in the Southwest among artists and collectors was part of a larger trend of locating an “authentic” American art tradition in the landscapes and cultures of locales outside major metropolises. The Regionalists —of whom Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood are the best known—claimed the rural, agrarian terrain as well as the inhabitants of the Midwest as subjects evocative of American values of hard work, self-reliance, and simplicity. Their stance that the Main Streets of small-town America constituted the “real” America presaged the rhetorical refrains of present-day politics on both the left and right.

Thomas Hart Benton (American, 1889–1975). Approaching Storm , 1940 Lithograph, 113/4 × 16 in. (29.8 × 40.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift (42.110.4)

Stylistically, the Regionalists tended to work in an easily legible manner marked by fluid compositions and dynamically posed figures. Many were commissioned to create prints for organizations that strove to make fine-art collecting accessible to the middle class and expand the market for American art, such as the Associated American Artists (AAA), which sold prints at accessible price points primarily through mail-order campaigns, at department stores, and at its galleries. The AAA and regional print clubs contributed to an interest in modernism and the dissemination of Regionalist ideology, with its association of American values with images of the heartland, to a large swath of the public. Benton’s Approaching Storm (1940) was commissioned by the Print Club of Cleveland, which distributed impressions of the lithograph to its members in 1940. Here, in an image typical of the artist’s mature work, a farmer glances up toward the dark roiling clouds in the sky as he makes his way home, barely visible in the distance.

Whose American Story?

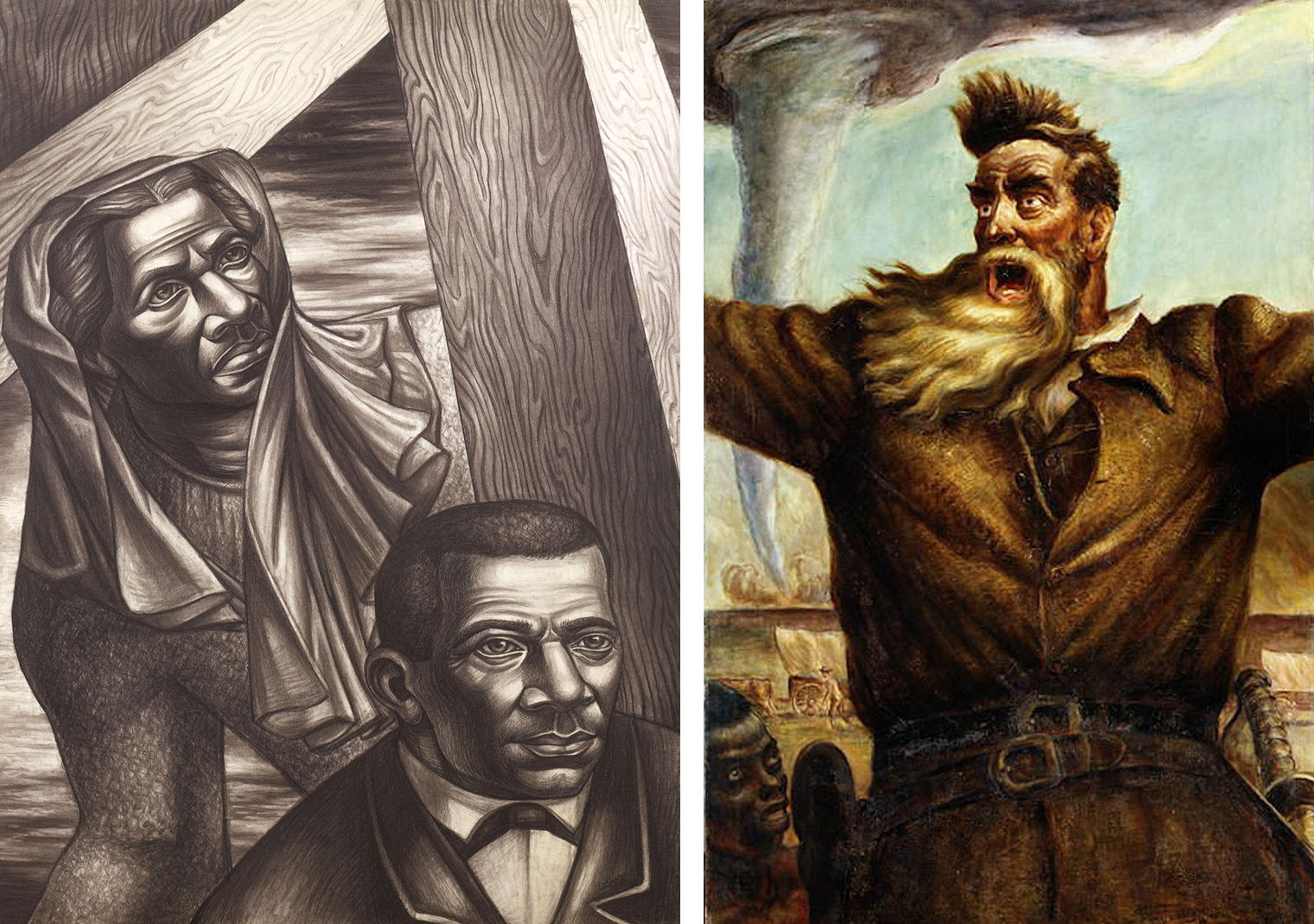

In their efforts to forge a national arts tradition during a time of upheaval, artists also turned to heroes and events from U.S. history to which they ascribed ideals of democracy and freedom. One example is the nineteenth-century white abolitionist John Brown, whose image permeated the art world of the 1930s. Curry honored him in a monumental painting , which served as a preparatory work for a mural in the rotunda of the Kansas State Capitol , as well as a print commissioned by the AAA, further cementing the image’s iconic status.

Left: Charles White (American, 1918–1979). Sojourner Truth and Booker T. Washington , 1943. Graphite on paperboard, 375/8 × 28 in. (95.6 × 71.1 cm). The Newark Museum of Art, N.J., Purchase, 1944, Sophronia Anderson Bequest Fund. Right: John Steuart Curry (American, 1897–1946). John Brown , 1939. Oil on canvas, 69 × 45 in. (175.3 × 114.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1950 (50.94.1)

Charles White sought to lay the groundwork for a more inclusive narrative of the nation’s history by centering the contributions of Black Americans. In 1942 he received a fellowship to make The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America for the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia. The mural was one of four on aspects of African American history that the painter worked on between 1939 and 1943. In conceiving the mural’s composition, White conducted thorough research on significant historical Black leaders of abolition, resistance, and cultural uplift, including Sojourner Truth and Booker T. Washington . The mural’s political resonance and arrangement of layered and overlapping figures were most directly inspired by the work of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, commonly known as los tres grandes—“the big three”—of the Mexican muralism movement that began in the early 1920s.

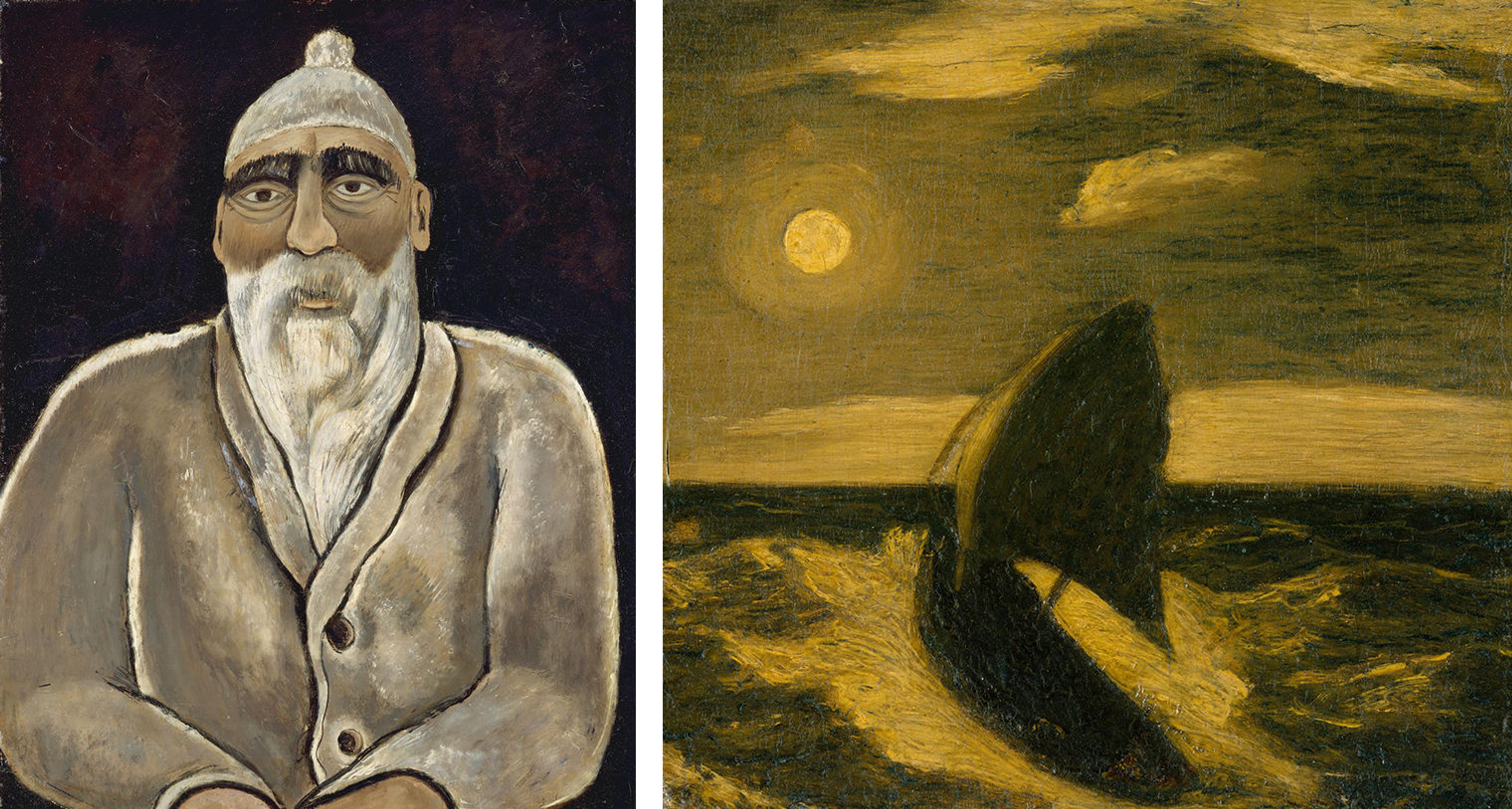

Marsden Hartley was keen to commemorate people who made an impact on the country’s cultural heritage, particularly as he reflected on his own artistic influences toward the end of his career. His 1938 portrait of Albert Pinkham Ryder speaks to the preoccupation of American artists of the 1930s with those of earlier generations; Ryder had garnered a reputation for being a mystic-like hermit during his lifetime and was revered by younger artists such as Hartley, who credited him with developing a distinctly American approach to landscape painting, characterized by a dark, moody palette, abstracted forms, and thick impasto surfaces. Hartley’s tender portrait, which is based on an encounter with Ryder in New York several decades early, evokes the imagery of religious icons, with the figure of Ryder seeming to glow against a dark background.

Left: Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). Albert Pinkham Ryder , 1938. Oil on commercially prepared paperboard (academy board) 28 × 22 in. (71.1 × 55.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edith and Milton Lowenthal Collection, Bequest of Edith Abrahamson Lowenthal, 1991 (1992.24.4). Right: Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847–1917). The Toilers of the Sea , 1880–85. Oil on wood, 11 1/2 x 12 in. (29.2 x 30.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, George A. Hearn Fund, 1915 (15.32)

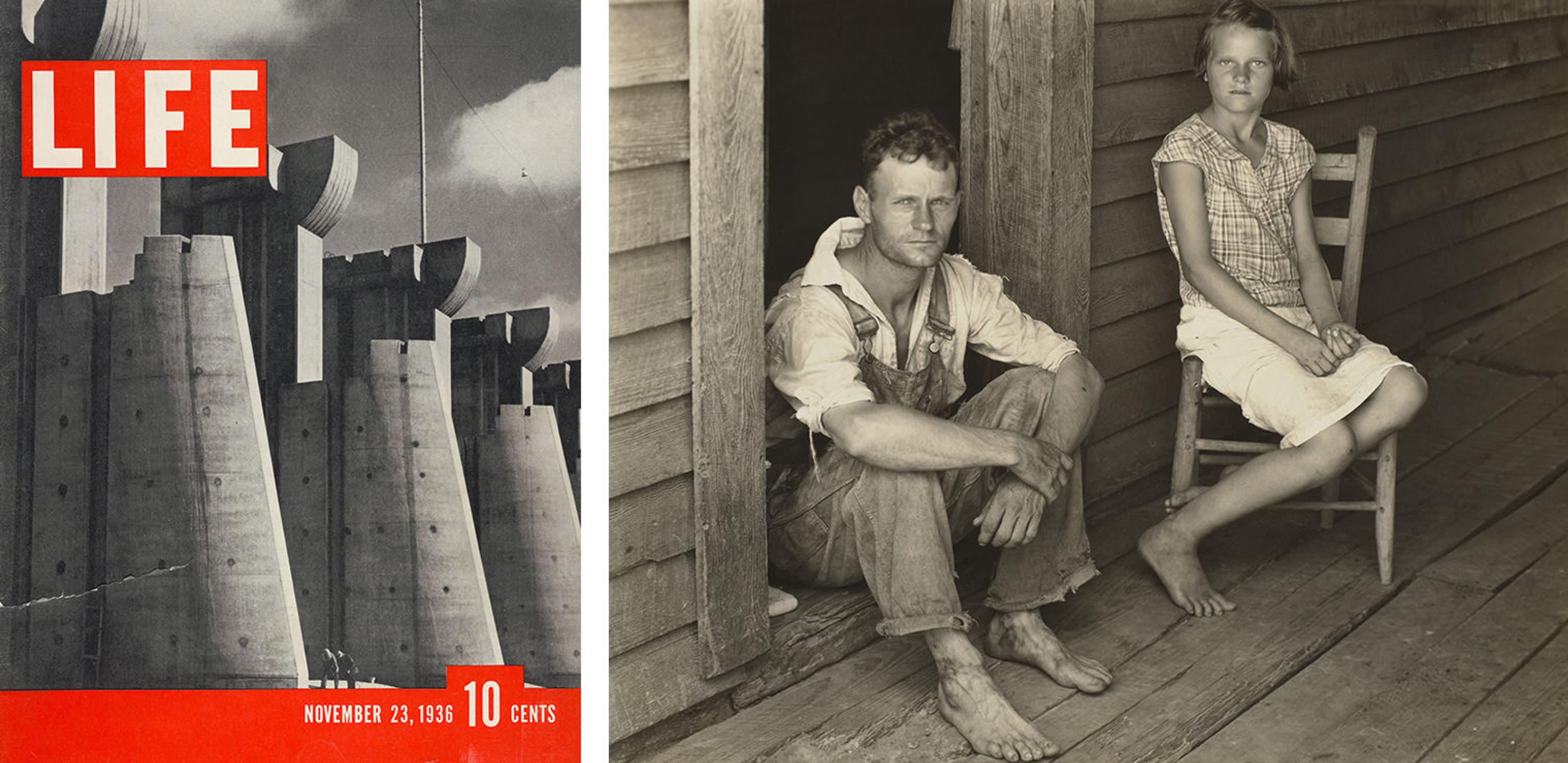

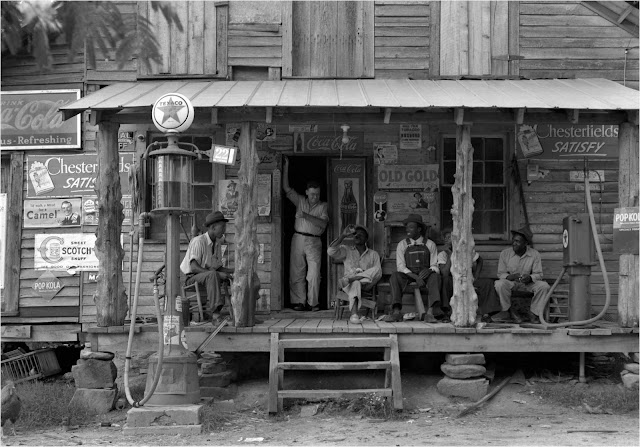

Documenting the United States

Some of the most celebrated images of the 1930s were not the sentimentalizing, romantic visions of the past and present that permeated the visual culture of the period but rather ones that captured everyday life. Photojournalism was reinvigorated with the introduction of the photo essay, which was meant to present impartial reportage of newsworthy events. At the same time, documentary-style photography representing a more subjective viewpoint experienced a resurgence thanks in large part to Roy Emerson Stryker, who headed the photography program of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a New Deal agency that combated poverty in rural areas. Stryker hired Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, and others to photograph the communities served by the FSA with the aim of promoting the agency’s raison d’être and persuading the masses of its importance. The impact of the photo essay is the subject of an editors’ note in the first issue of Life magazine in 1936. Referring to Margaret Bourke-White’s photograph of the newly constructed Fort Peck Dam in Montana that graced the cover and others by her that captured construction along the Columbia River, they wrote, “What the Editors expected—for use in some later issue—were construction pictures as only Bourke-White can take them. What the Editors got was a human document of American frontier life which, to them at least, was a revelation.” Bourke-White was, notably, the highest-paid photographer of the era.

Left: 1936 cover of Life magazine with a photo by Margaret Bourke-White. Right: Walker Evans (American, 1903–1975). Floyd and Lucille Burroughs on Porch, Hale County, Alabama , 1936. Gelatin silver print, 77/16 × 95/16 in. (18.9 × 23.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Marlene Nathan Meyerson Family Foundation Gift, in memory of David Nathan Meyerson; and Pat and John Rosenwald and Lila Acheson Wallace Gifts, 1999 (1999.237.4)

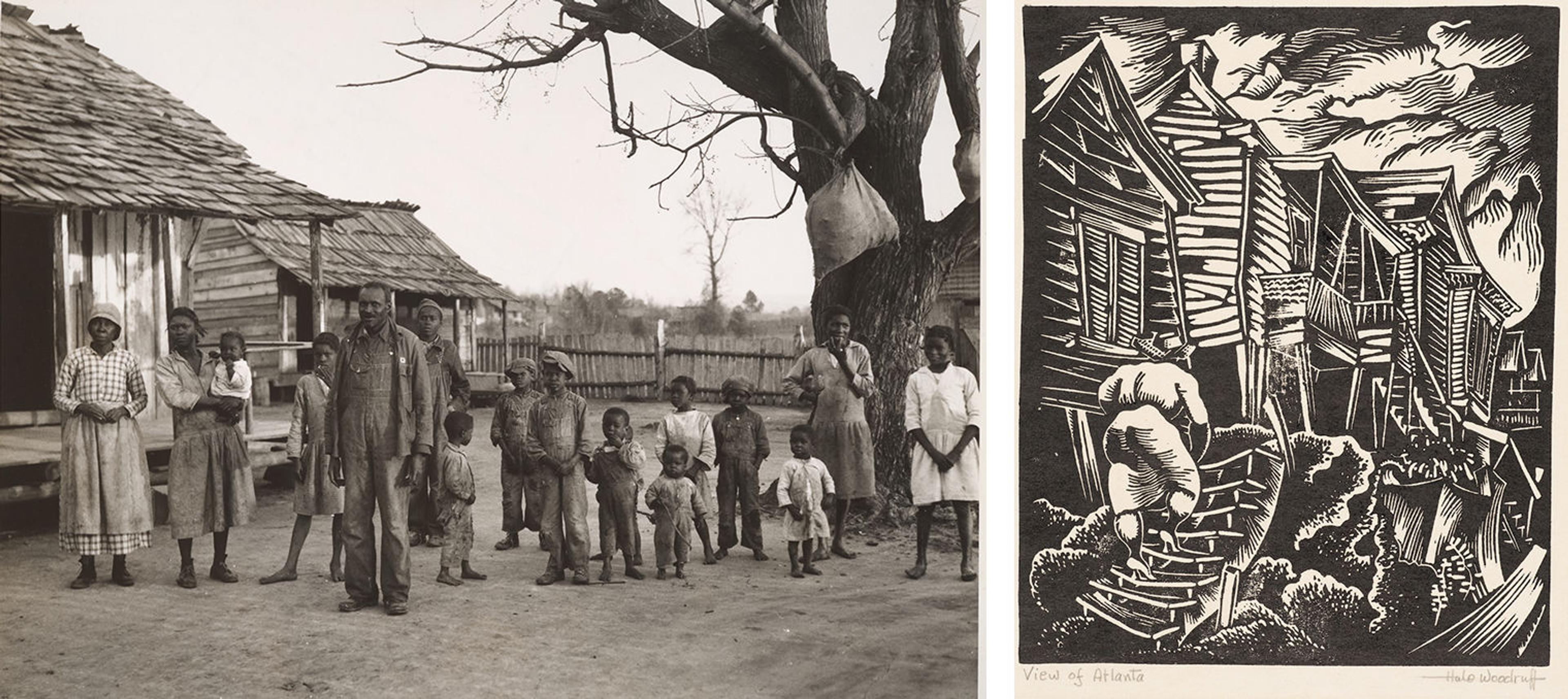

While Bourke-White celebrated American technological ingenuity in her photographs, documentary photographers often used their camera as a tool to instigate social change. Many of Evans’s most celebrated images were for Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), a book he made in collaboration with James Agee, who had been assigned to write an article on cotton tenant farming by Fortune magazine. The two friends traveled around the South in 1936, with Evans creating arresting photographs of the farmers and their families, such as the Burroughs, whom he encountered in Hale County, Alabama. The editors at Fortune stipulated that Evans photograph white farmers only, despite the fact that the vast majority of tenant farmers in the South were Black.

Left: Arthur Rothstein (American, 1915–1985). African American Family at Gee’s Bend, Alabama , 1937. Gelatin silver print, 71/8 × 91/2 in. (18.1 × 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2001 (2001.298). Right: Hale Woodruff (American, 1900–1980). View of Atlanta , 1935 Linocut, 97/8 × 8 in. (25.1 × 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 1999 (1999.529.201)