- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Work, stress, coping, and stress management.

- Sharon Glazer Sharon Glazer University of Baltimore

- and Cong Liu Cong Liu Hofstra University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.30

- Published online: 26 April 2017

Work stress refers to the process of job stressors, or stimuli in the workplace, leading to strains, or negative responses or reactions. Organizational development refers to a process in which problems or opportunities in the work environment are identified, plans are made to remediate or capitalize on the stimuli, action is taken, and subsequently the results of the plans and actions are evaluated. When organizational development strategies are used to assess work stress in the workplace, the actions employed are various stress management interventions. Two key factors tying work stress and organizational development are the role of the person and the role of the environment. In order to cope with work-related stressors and manage strains, organizations must be able to identify and differentiate between factors in the environment that are potential sources of stressors and how individuals perceive those factors. Primary stress management interventions focus on preventing stressors from even presenting, such as by clearly articulating workers’ roles and providing necessary resources for employees to perform their job. Secondary stress management interventions focus on a person’s appraisal of job stressors as a threat or challenge, and the person’s ability to cope with the stressors (presuming sufficient internal resources, such as a sense of meaningfulness in life, or external resources, such as social support from a supervisor). When coping is not successful, strains may develop. Tertiary stress management interventions attempt to remediate strains, by addressing the consequence itself (e.g., diabetes management) and/or the source of the strain (e.g., reducing workload). The person and/or the organization may be the targets of the intervention. The ultimate goal of stress management interventions is to minimize problems in the work environment, intensify aspects of the work environment that create a sense of a quality work context, enable people to cope with stressors that might arise, and provide tools for employees and organizations to manage strains that might develop despite all best efforts to create a healthy workplace.

- stress management

- organization development

- organizational interventions

- stress theories and frameworks

Introduction

Work stress is a generic term that refers to work-related stimuli (aka job stressors) that may lead to physical, behavioral, or psychological consequences (i.e., strains) that affect both the health and well-being of the employee and the organization. Not all stressors lead to strains, but all strains are a result of stressors, actual or perceived. Common terms often used interchangeably with work stress are occupational stress, job stress, and work-related stress. Terms used interchangeably with job stressors include work stressors, and as the specificity of the type of stressor might include psychosocial stressor (referring to the psychological experience of work demands that have a social component, e.g., conflict between two people; Hauke, Flintrop, Brun, & Rugulies, 2011 ), hindrance stressor (i.e., a stressor that prevents goal attainment; Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, & Boudreau, 2000 ), and challenge stressor (i.e., a stressor that is difficult, but attainable and possibly rewarding to attain; Cavanaugh et al., 2000 ).

Stress in the workplace continues to be a highly pervasive problem, having both direct negative effects on individuals experiencing it and companies paying for it, and indirect costs vis à vis lost productivity (Dopkeen & DuBois, 2014 ). For example, U.K. public civil servants’ work-related stress rose from 10.8% in 2006 to 22.4% in 2013 and about one-third of the workforce has taken more than 20 days of leave due to stress-related ill-health, while well over 50% are present at work when ill (French, 2015 ). These findings are consistent with a report by the International Labor Organization (ILO, 2012 ), whereby 50% to 60% of all workdays are lost due to absence attributed to factors associated with work stress.

The prevalence of work-related stress is not diminishing despite improvements in technology and employment rates. The sources of stress, such as workload, seem to exacerbate with improvements in technology (Coovert & Thompson, 2003 ). Moreover, accessibility through mobile technology and virtual computer terminals is linking people to their work more than ever before (ILO, 2012 ; Tarafdar, Tu, Ragu-Nathan, & Ragu-Nathan, 2007 ). Evidence of this kind of mobility and flexibility is further reinforced in a June 2007 survey of 4,025 email users (over 13 years of age); AOL reported that four in ten survey respondents reported planning their vacations around email accessibility and 83% checked their emails at least once a day while away (McMahon, 2007 ). Ironically, despite these mounting work-related stressors and clear financial and performance outcomes, some individuals are reporting they are less “stressed,” but only because “stress has become the new normal” (Jayson, 2012 , para. 4).

This new normal is likely the source of psychological and physiological illness. Siegrist ( 2010 ) contends that conditions in the workplace, particularly psychosocial stressors that are perceived as unfavorable relationships with others and self, and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle (reinforced with desk jobs) are increasingly contributing to cardiovascular disease. These factors together justify a need to continue on the path of helping individuals recognize and cope with deleterious stressors in the work environment and, equally important, to find ways to help organizations prevent harmful stressors over which they have control, as well as implement policies or mechanisms to help employees deal with these stressors and subsequent strains. Along with a greater focus on mitigating environmental constraints are interventions that can be used to prevent anxiety, poor attitudes toward the workplace conditions and arrangements, and subsequent cardiovascular illness, absenteeism, and poor job performance (Siegrist, 2010 ).

Even the ILO has presented guidance on how the workplace can help prevent harmful job stressors (aka hindrance stressors) or at least help workers cope with them. Consistent with the view that well-being is not the absence of stressors or strains and with the view that positive psychology offers a lens for proactively preventing stressors, the ILO promotes increasing preventative risk assessments, interventions to prevent and control stressors, transparent organizational communication, worker involvement in decision-making, networks and mechanisms for workplace social support, awareness of how working and living conditions interact, safety, health, and well-being in the organization (ILO, n.d. ). The field of industrial and organizational (IO) psychology supports the ILO’s recommendations.

IO psychology views work stress as the process of a person’s interaction with multiple aspects of the work environment, job design, and work conditions in the organization. Interventions to manage work stress, therefore, focus on the psychosocial factors of the person and his or her relationships with others and the socio-technical factors related to the work environment and work processes. Viewing work stress from the lens of the person and the environment stems from Kurt Lewin’s ( 1936 ) work that stipulates a person’s state of mental health and behaviors are a function of the person within a specific environment or situation. Aspects of the work environment that affect individuals’ mental states and behaviors include organizational hierarchy, organizational climate (including processes, policies, practices, and reward structures), resources to support a person’s ability to fulfill job duties, and management structure (including leadership). Job design refers to each contributor’s tasks and responsibilities for fulfilling goals associated with the work role. Finally, working conditions refers not only to the physical environment, but also the interpersonal relationships with other contributors.

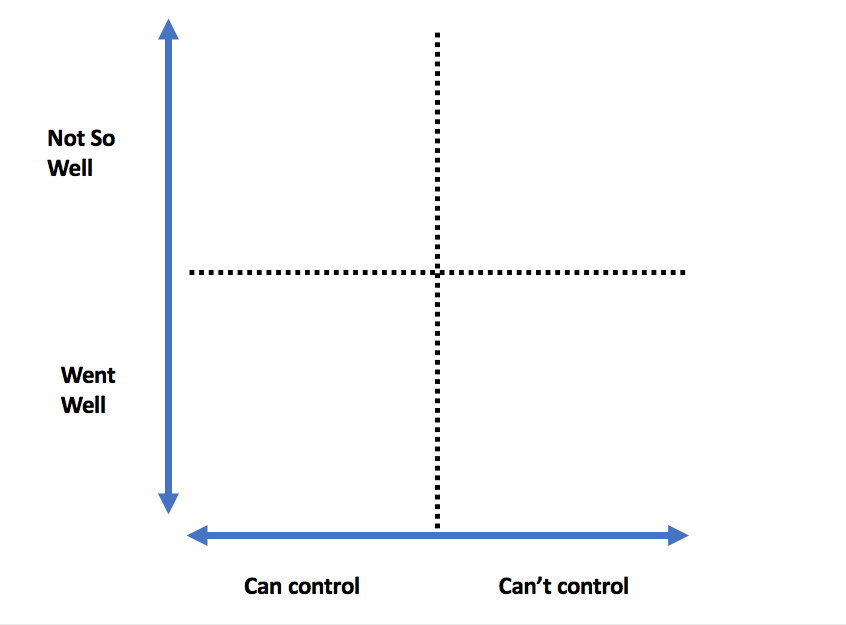

Each of the conditions that are identified in the work environment may be perceived as potentially harmful or a threat to the person or as an opportunity. When a stressor is perceived as a threat to attaining desired goals or outcomes, the stressor may be labeled as a hindrance stressor (e.g., LePine, Podsakoff, & Lepine, 2005 ). When the stressor is perceived as an opportunity to attain a desired goal or end state, it may be labeled as a challenge stressor. According to LePine and colleagues’ ( 2005 ), both challenge (e.g., time urgency, workload) and hindrance (e.g., hassles, role ambiguity, role conflict) stressors could lead to strains (as measured by “anxiety, depersonalization, depression, emotional exhaustion, frustration, health complaints, hostility, illness, physical symptoms, and tension” [p. 767]). However, challenge stressors positively relate with motivation and performance, whereas hindrance stressors negatively relate with motivation and performance. Moreover, motivation and strains partially mediate the relationship between hindrance and challenge stressors with performance.

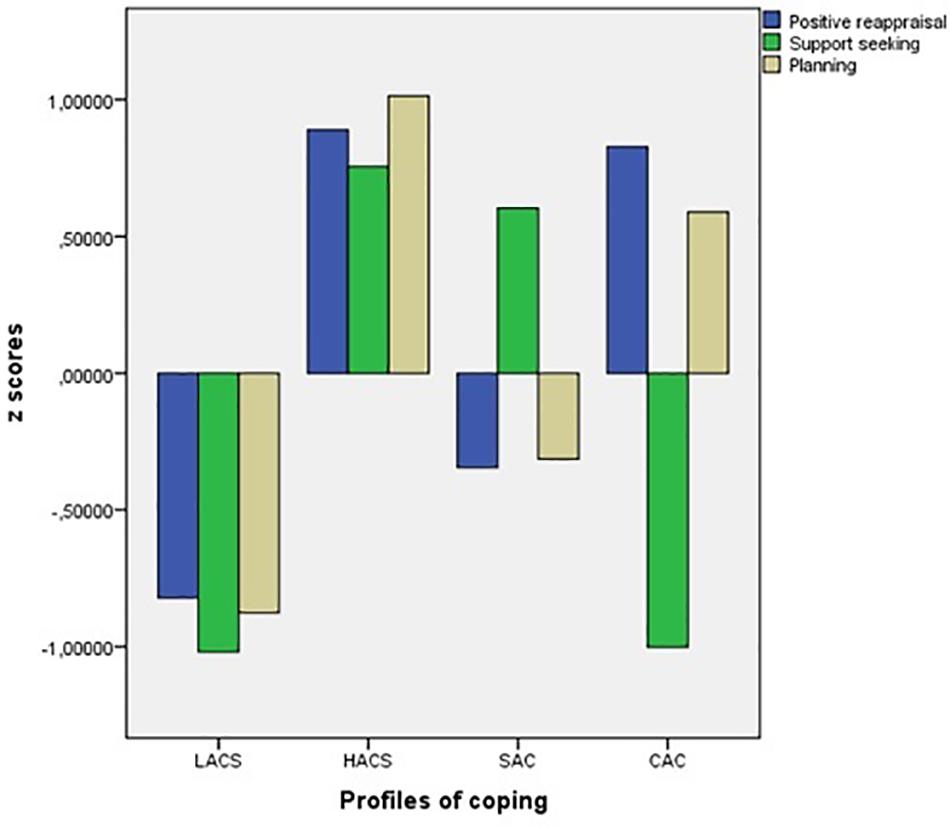

Figure 1. Organizational development frameworks to guide identification of work stress and interventions.

In order to (1) minimize any potential negative effects from stressors, (2) increase coping skills to deal with stressors, or (3) manage strains, organizational practitioners or consultants will devise organizational interventions geared toward prevention, coping, and/or stress management. Ultimately, toxic factors in the work environment can have deleterious effects on a person’s physical and psychological well-being, as well as on an organization’s total health. It behooves management to take stock of the organization’s health, which includes the health and well-being of its employees, if the organization wishes to thrive and be profitable. According to Page and Vella-Brodrick’s ( 2009 ) model of employee well-being, employee well-being results from subjective well-being (i.e., life satisfaction and general positive or negative affect), workplace well-being (composed of job satisfaction and work-specific positive or negative affect), and psychological well-being (e.g., self-acceptance, positive social relations, mastery, purpose in life). Job stressors that become unbearable are likely to negatively affect workplace well-being and thus overall employee well-being. Because work stress is a major organizational pain point and organizations often employ organizational consultants to help identify and remediate pain points, the focus here is on organizational development (OD) frameworks; several work stress frameworks are presented that together signal areas where organizations might focus efforts for change in employee behaviors, attitudes, and performance, as well as the organization’s performance and climate. Work stress, interventions, and several OD and stress frameworks are depicted in Figure 1 .

The goals are: (1) to conceptually define and clarify terms associated with stress and stress management, particularly focusing on organizational factors that contribute to stress and stress management, and (2) to present research that informs current knowledge and practices on workplace stress management strategies. Stressors and strains will be defined, leading OD and work stress frameworks that are used to organize and help organizations make sense of the work environment and the organization’s responsibility in stress management will be explored, and stress management will be explained as an overarching thematic label; an area of study and practice that focuses on prevention (primary) interventions, coping (secondary) interventions, and managing strains (tertiary) interventions; as well as the label typically used to denote tertiary interventions. Suggestions for future research and implications toward becoming a healthy organization are presented.

Defining Stressors and Strains

Work-related stressors or job stressors can lead to different kinds of strains individuals and organizations might experience. Various types of stress management interventions, guided by OD and work stress frameworks, may be employed to prevent or cope with job stressors and manage strains that develop(ed).

A job stressor is a stimulus external to an employee and a result of an employee’s work conditions. Example job stressors include organizational constraints, workplace mistreatments (such as abusive supervision, workplace ostracism, incivility, bullying), role stressors, workload, work-family conflicts, errors or mistakes, examinations and evaluations, and lack of structure (Jex & Beehr, 1991 ; Liu, Spector, & Shi, 2007 ; Narayanan, Menon, & Spector, 1999 ). Although stressors may be categorized as hindrances and challenges, there is not yet sufficient information to be able to propose which stress management interventions would better serve to reduce those hindrance stressors or to reduce strain-producing challenge stressors while reinforcing engagement-producing challenge stressors.

Organizational Constraints

Organizational constraints may be hindrance stressors as they prevent employees from translating their motivation and ability into high-level job performance (Peters & O’Connor, 1980 ). Peters and O’Connor ( 1988 ) defined 11 categories of organizational constraints: (1) job-related information, (2) budgetary support, (3) required support, (4) materials and supplies, (5) required services and help from others, (6) task preparation, (7) time availability, (8) the work environment, (9) scheduling of activities, (10) transportation, and (11) job-relevant authority. The inhibiting effect of organizational constraints may be due to the lack of, inadequacy of, or poor quality of these categories.

Workplace Mistreatment

Workplace mistreatment presents a cluster of interpersonal variables, such as interpersonal conflict, bullying, incivility, and workplace ostracism (Hershcovis, 2011 ; Tepper & Henle, 2011 ). Typical workplace mistreatment behaviors include gossiping, rude comments, showing favoritism, yelling, lying, and ignoring other people at work (Tepper & Henle, 2011 ). These variables relate to employees’ psychological well-being, physical well-being, work attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction and organizational commitment), and turnover intention (e.g., Hershcovis, 2011 ; Spector & Jex, 1998 ). Some researchers differentiated the source of mistreatment, such as mistreatment from one’s supervisor versus mistreatment from one’s coworker (e.g., Bruk-Lee & Spector, 2006 ; Frone, 2000 ; Liu, Liu, Spector, & Shi, 2011 ).

Role Stressors

Role stressors are demands, constraints, or opportunities a person perceives to be associated, and thus expected, with his or her work role(s) across various situations. Three commonly studied role stressors are role ambiguity, role conflict, and role overload (Glazer & Beehr, 2005 ; Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964 ). Role ambiguity in the workplace occurs when an employee lacks clarity regarding what performance-related behaviors are expected of him or her. Role conflict refers to situations wherein an employee receives incompatible role requests from the same or different supervisors or the employee is asked to engage in work that impedes his or her performance in other work or nonwork roles or clashes with his or her values. Role overload refers to excessive demands and insufficient time (quantitative) or knowledge (qualitative) to complete the work. The construct is often used interchangeably with workload, though role overload focuses more on perceived expectations from others about one’s workload. These role stressors significantly relate to low job satisfaction, low organizational commitment, low job performance, high tension or anxiety, and high turnover intention (Abramis, 1994 ; Glazer & Beehr, 2005 ; Jackson & Schuler, 1985 ).

Excessive workload is one of the most salient stressors at work (e.g., Liu et al., 2007 ). There are two types of workload: quantitative and qualitative workload (LaRocco, Tetrick, & Meder, 1989 ; Parasuraman & Purohit, 2000 ). Quantitative workload refers to the excessive amount of work one has. In a summary of a Chartered Institute of Personnel & Development Report from 2006 , Dewe and Kompier ( 2008 ) noted that quantitative workload was one of the top three stressors workers experienced at work. Qualitative workload refers to the difficulty of work. Workload also differs by the type of the load. There are mental workload and physical workload (Dwyer & Ganster, 1991 ). Excessive physical workload may result in physical discomfort or illness. Excessive mental workload will cause psychological distress such as anxiety or frustration (Bowling & Kirkendall, 2012 ). Another factor affecting quantitative workload is interruptions (during the workday). Lin, Kain, and Fritz ( 2013 ) found that interruptions delay completion of job tasks, thus adding to the perception of workload.

Work-Family Conflict

Work-family conflict is a form of inter-role conflict in which demands from one’s work domain and one’s family domain are incompatible to some extent (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985 ). Work can interfere with family (WIF) and/or family can interfere with work (FIW) due to time-related commitments to participating in one domain or another, incompatible behavioral expectations, or when strains in one domain carry over to the other (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985 ). Work-family conflict significantly relates to work-related outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, burnout, absenteeism, job performance, job strains, career satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors), family-related outcomes (e.g., marital satisfaction, family satisfaction, family-related performance, family-related strains), and domain-unspecific outcomes (e.g., life satisfaction, psychological strain, somatic or physical symptoms, depression, substance use or abuse, and anxiety; Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering, & Semmer, 2011 ).

Individuals and organizations can experience work-related strains. Sometimes organizations will experience strains through the employee’s negative attitudes or strains, such as that a worker’s absence might yield lower production rates, which would roll up into an organizational metric of organizational performance. In the industrial and organizational (IO) psychology literature, organizational strains are mostly observed as macro-level indicators, such as health insurance costs, accident-free days, and pervasive problems with company morale. In contrast, individual strains, usually referred to as job strains, are internal to an employee. They are responses to work conditions and relate to health and well-being of employees. In other words, “job strains are adverse reactions employees have to job stressors” (Spector, Chen, & O’Connell, 2000 , p. 211). Job strains tend to fall into three categories: behavioral, physical, and psychological (Jex & Beehr, 1991 ).

Behavioral strains consist of actions that employees take in response to job stressors. Examples of behavioral strains include employees drinking alcohol in the workplace or intentionally calling in sick when they are not ill (Spector et al., 2000 ). Physical strains consist of health symptoms that are physiological in nature that employees contract in response to job stressors. Headaches and ulcers are examples of physical strains. Lastly, psychological strains are emotional reactions and attitudes that employees have in response to job stressors. Examples of psychological strains are job dissatisfaction, anxiety, and frustration (Spector et al., 2000 ). Interestingly, research studies that utilize self-report measures find that most job strains experienced by employees tend to be psychological strains (Spector et al., 2000 ).

Leading Frameworks

Organizations that are keen on identifying organizational pain points and remedying them through organizational campaigns or initiatives often discover the pain points are rooted in work-related stressors and strains and the initiatives have to focus on reducing workers’ stress and increasing a company’s profitability. Through organizational climate surveys, for example, companies discover that aspects of the organization’s environment, including its policies, practices, reward structures, procedures, and processes, as well as employees at all levels of the company, are contributing to the individual and organizational stress. Recent studies have even begun to examine team climates for eustress and distress assessed in terms of team members’ homogenous psychological experience of vigor, efficacy, dedication, and cynicism (e.g., Kożusznik, Rodriguez, & Peiro, 2015 ).

Each of the frameworks presented advances different aspects that need to be identified in order to understand the source and potential remedy for stressors and strains. In some models, the focus is on resources, in others on the interaction of the person and environment, and in still others on the role of the person in the workplace. Few frameworks directly examine the role of the organization, but the organization could use these frameworks to plan interventions that would minimize stressors, cope with existing stressors, and prevent and/or manage strains. One of the leading frameworks in work stress research that is used to guide organizational interventions is the person and environment (P-E) fit (French & Caplan, 1972 ). Its precursor is the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research’s (ISR) role stress model (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964 ) and Lewin’s Field Theory. Several other theories have since evolved from the P-E fit framework, including Karasek and Theorell’s ( 1990 ), Karasek ( 1979 ) Job Demands-Control Model (JD-C), the transactional framework (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ), Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989 ), and Siegrist’s ( 1996 ) Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) Model.

Field Theory

The premise of Kahn et al.’s ( 1964 ) role stress theory is Lewin’s ( 1997 ) Field Theory. Lewin purported that behavior and mental events are a dynamic function of the whole person, including a person’s beliefs, values, abilities, needs, thoughts, and feelings, within a given situation (field or environment), as well as the way a person represents his or her understanding of the field and behaves in that space. Lewin explains that work-related strains are a result of individuals’ subjective perceptions of objective factors, such as work roles, relationships with others in the workplace, as well as personality indicators, and can be used to predict people’s reactions, including illness. Thus, to make changes to an organizational system, it is necessary to understand a field and try to move that field from the current state to the desired state. Making this move necessitates identifying mechanisms influencing individuals.

Role Stress Theory

Role stress theory mostly isolates the perspective a person has about his or her work-related responsibilities and expectations to determine how those perceptions relate with a person’s work-related strains. However, those relationships have been met with somewhat varied results, which Glazer and Beehr ( 2005 ) concluded might be a function of differences in culture, an environmental factor often neglected in research. Kahn et al.’s ( 1964 ) role stress theory, coupled with Lewin’s ( 1936 ) Field Theory, serves as the foundation for the P-E fit theory. Lewin ( 1936 ) wrote, “Every psychological event depends upon the state of the person and at the same time on the environment” (p. 12). Researchers of IO psychology have narrowed the environment to the organization or work team. This narrowed view of the organizational environment is evident in French and Caplan’s ( 1972 ) P-E fit framework.

Person-Environment Fit Theory

The P-E fit framework focuses on the extent to which there is congruence between the person and a given environment, such as the organization (Caplan, 1987 ; Edwards, 2008 ). For example, does the person have the necessary skills and abilities to fulfill an organization’s demands, or does the environment support a person’s desire for autonomy (i.e., do the values align?) or fulfill a person’s needs (i.e., a person’s needs are rewarded). Theoretically and empirically, the greater the person-organization fit, the greater a person’s job satisfaction and organizational commitment, the less a person’s turnover intention and work-related stress (see meta-analyses by Assouline & Meir, 1987 ; Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005 ; Verquer, Beehr, & Wagner, 2003 ).

Job Demands-Control/Support (JD-C/S) and Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model

Focusing more closely on concrete aspects of work demands and the extent to which a person perceives he or she has control or decision latitude over those demands, Karasek ( 1979 ) developed the JD-C model. Karasek and Theorell ( 1990 ) posited that high job demands under conditions of little decision latitude or control yield high strains, which have varied implications on the health of an organization (e.g., in terms of high turnover, employee ill-health, poor organizational performance). This theory was modified slightly to address not only control, but also other resources that could protect a person from unruly job demands, including support (aka JD-C/S, Johnson & Hall, 1988 ; and JD-R, Bakker, van Veldhoven, & Xanthopoulou, 2010 ). Whether focusing on control or resources, both they and job demands are said to reflect workplace characteristics, while control and resources also represent coping strategies or tools (Siegrist, 2010 ).

Despite the glut of research testing the JD-C and JD-R, results are somewhat mixed. Testing the interaction between job demands and control, Beehr, Glaser, Canali, and Wallwey ( 2001 ) did not find empirical support for the JD-C theory. However, Dawson, O’Brien, and Beehr ( 2016 ) found that high control and high support buffered against the independent deleterious effects of interpersonal conflict, role conflict, and organizational politics (demands that were categorized as hindrance stressors) on anxiety, as well as the effects of interpersonal conflict and organizational politics on physiological symptoms, but control and support did not moderate the effects between challenge stressors and strains. Coupled with Bakker, Demerouti, and Sanz-Vergel’s ( 2014 ) note that excessive job demands are a source of strain, but increased job resources are a source of engagement, Dawson et al.’s results suggest that when an organization identifies that demands are hindrances, it can create strategies for primary (preventative) stress management interventions and attempt to remove or reduce such work demands. If the demands are challenging, though manageable, but latitude to control the challenging stressors and support are insufficient, the organization could modify practices and train employees on adopting better strategies for meeting or coping (secondary stress management intervention) with the demands. Finally, if the organization can neither afford to modify the demands or the level of control and support, it will be necessary for the organization to develop stress management (tertiary) interventions to deal with the inevitable strains.

Conservation of Resources Theory

The idea that job resources reinforce engagement in work has been propagated in Hobfoll’s ( 1989 ) Conservation of Resources (COR) theory. COR theory also draws on the foundational premise that people’s mental health is a function of the person and the environment, forwarding that how people interpret their environment (including the societal context) affects their stress levels. Hobfoll focuses on resources such as objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies as particularly instrumental to minimizing strains. He asserts that people do whatever they can to protect their valued resources. Thus, strains develop when resources are threatened to be taken away, actually taken away, or when additional resources are not attainable after investing in the possibility of gaining more resources (Hobfoll, 2001 ). By extension, organizations can invest in activities that would minimize resource loss and create opportunities for resource gains and thus have direct implications for devising primary and secondary stress management interventions.

Transactional Framework

Lazarus and Folkman ( 1984 ) developed the widely studied transactional framework of stress. This framework holds as a key component the cognitive appraisal process. When individuals perceive factors in the work environment as a threat (i.e., primary appraisal), they will scan the available resources (external or internal to himself or herself) to cope with the stressors (i.e., secondary appraisal). If the coping resources provide minimal relief, strains develop. Until recently, little attention has been given to the cognitive appraisal associated with different work stressors (Dewe & Kompier, 2008 ; Liu & Li, 2017 ). In a study of Polish and Spanish social care service providers, stressors appraised as a threat related positively to burnout and less engagement, but stressors perceived as challenges yielded greater engagement and less burnout (Kożusznik, Rodriguez, & Peiro, 2012 ). Similarly, Dawson et al. ( 2016 ) found that even with support and control resources, hindrance demands were more strain-producing than challenge demands, suggesting that appraisal of the stressor is important. In fact, “many people respond well to challenging work” (Beehr et al., 2001 , p. 126). Kożusznik et al. ( 2012 ) recommend training employees to change the way they view work demands in order to increase engagement, considering that part of the problem may be about how the person appraises his or her environment and, thus, copes with the stressors.

Effort-Reward Imbalance

Siegrist’s ( 1996 ) Model of Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) focuses on the notion of social reciprocity, such that a person fulfills required work tasks in exchange for desired rewards (Siegrist, 2010 ). ERI sheds light on how an imbalance in a person’s expectations of an organization’s rewards (e.g., pay, bonus, sense of advancement and development, job security) in exchange for a person’s efforts, that is a break in one’s work contract, leads to negative responses, including long-term ill-health (Siegrist, 2010 ; Siegrist et al., 2014 ). In fact, prolonged perception of a work contract imbalance leads to adverse health, including immunological problems and inflammation, which contribute to cardiovascular disease (Siegrist, 2010 ). The model resembles the relational and interactional psychological contract theory in that it describes an employee’s perception of the terms of the relationship between the person and the workplace, including expectations of performance, job security, training and development opportunities, career progression, salary, and bonuses (Thomas, Au, & Ravlin, 2003 ). The psychological contract, like the ERI model, focuses on social exchange. Furthermore, the psychological contract, like stress theories, are influenced by cultural factors that shape how people interpret their environments (Glazer, 2008 ; Thomas et al., 2003 ). Violations of the psychological contract will negatively affect a person’s attitudes toward the workplace and subsequent health and well-being (Siegrist, 2010 ). To remediate strain, Siegrist ( 2010 ) focuses on both the person and the environment, recognizing that the organization is particularly responsible for changing unfavorable work conditions and the person is responsible for modifying his or her reactions to such conditions.

Stress Management Interventions: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary

Remediation of work stress and organizational development interventions are about realigning the employee’s experiences in the workplace with factors in the environment, as well as closing the gap between the current environment and the desired environment. Work stress develops when an employee perceives the work demands to exceed the person’s resources to cope and thus threatens employee well-being (Dewe & Kompier, 2008 ). Likewise, an organization’s need to change arises when forces in the environment are creating a need to change in order to survive (see Figure 1 ). Lewin’s ( 1951 ) Force Field Analysis, the foundations of which are in Field Theory, is one of the first organizational development intervention tools presented in the social science literature. The concept behind Force Field Analysis is that in order to survive, organizations must adapt to environmental forces driving a need for organizational change and remove restraining forces that create obstacles to organizational change. In order to do this, management needs to delineate the current field in which the organization is functioning, understand the driving forces for change, identify and dampen or eliminate the restraining forces against change. Several models for analyses may be applied, but most approaches are variations of organizational climate surveys.

Through organizational surveys, workers provide management with a snapshot view of how they perceive aspects of their work environment. Thus, the view of the health of an organization is a function of several factors, chief among them employees’ views (i.e., the climate) about the workplace (Lewin, 1951 ). Indeed, French and Kahn ( 1962 ) posited that well-being depends on the extent to which properties of the person and properties of the environment align in terms of what a person requires and the resources available in a given environment. Therefore, only when properties of the person and properties of the environment are sufficiently understood can plans for change be developed and implemented targeting the environment (e.g., change reporting structures to relieve, and thus prevent future, communication stressors) and/or the person (e.g., providing more autonomy, vacation days, training on new technology). In short, climate survey findings can guide consultants about the emphasis for organizational interventions: before a problem arises aka stress prevention, e.g., carefully crafting job roles), when a problem is present, but steps are taken to mitigate their consequences (aka coping, e.g., providing social support groups), and/or once strains develop (aka. stress management, e.g., healthcare management policies).

For each of the primary (prevention), secondary (coping), and tertiary (stress management) techniques the target for intervention can be the entire workforce, a subset of the workforce, or a specific person. Interventions that target the entire workforce may be considered organizational interventions, as they have direct implications on the health of all individuals and consequently the health of the organization. Several interventions categorized as primary and secondary interventions may also be implemented after strains have developed and after it has been discerned that a person or the organization did not do enough to mitigate stressors or strains (see Figure 1 ). The designation of many of the interventions as belonging to one category or another may be viewed as merely a suggestion.

Primary Interventions (Preventative Stress Management)

Before individuals begin to perceive work-related stressors, organizations engage in stress prevention strategies, such as providing people with resources (e.g., computers, printers, desk space, information about the job role, organizational reporting structures) to do their jobs. However, sometimes the institutional structures and resources are insufficient or ambiguous. Scholars and practitioners have identified several preventative stress management strategies that may be implemented.

Planning and Time Management

When employees feel quantitatively overloaded, sometimes the remedy is improving the employees’ abilities to plan and manage their time (Quick, Quick, Nelson, & Hurrell, 2003 ). Planning is a future-oriented activity that focuses on conceptual and comprehensive work goals. Time management is a behavior that focuses on organizing, prioritizing, and scheduling work activities to achieve short-term goals. Given the purpose of time management, it is considered a primary intervention, as engaging in time management helps to prevent work tasks from mounting and becoming unmanageable, which would subsequently lead to adverse outcomes. Time management comprises three fundamental components: (1) establishing goals, (2) identifying and prioritizing tasks to fulfill the goals, and (3) scheduling and monitoring progress toward goal achievement (Peeters & Rutte, 2005 ). Workers who employ time management have less role ambiguity (Macan, Shahani, Dipboye, & Philips, 1990 ), psychological stress or strain (Adams & Jex, 1999 ; Jex & Elaqua, 1999 ; Macan et al., 1990 ), and greater job satisfaction (Macan, 1994 ). However, Macan ( 1994 ) did not find a relationship between time management and performance. Still, Claessens, van Eerde, Rutte, and Roe ( 2004 ) found that perceived control of time partially mediated the relationships between planning behavior (an indicator of time management), job autonomy, and workload on one hand, and job strains, job satisfaction, and job performance on the other hand. Moreover, Peeters and Rutte ( 2005 ) observed that teachers with high work demands and low autonomy experienced more burnout when they had poor time management skills.

Person-Organization Fit

Just as it is important for organizations to find the right person for the job and organization, so is it the responsibility of a person to choose to work at the right organization—an organization that fulfills the person’s needs and upholds the values important to the individual, as much as the person fulfills the organization’s needs and adapts to its values. When people fit their employing organizations they are setting themselves up for experiencing less strain-producing stressors (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005 ). In a meta-analysis of 62 person-job fit studies and 110 person-organization fit studies, Kristof-Brown et al. ( 2005 ) found that person-job fit had a negative correlation with indicators of job strain. In fact, a primary intervention of career counseling can help to reduce stress levels (Firth-Cozens, 2003 ).

Job Redesign

The Job Demands-Control/Support (JD-C/S), Job Demands-Resources (JD-R), and transactional models all suggest that factors in the work context require modifications in order to reduce potential ill-health and poor organizational performance. Drawing on Hackman and Oldham’s ( 1980 ) Job Characteristics Model, it is possible to assess with the Job Diagnostics Survey (JDS) the current state of work characteristics related to skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback. Modifying those aspects would help create a sense of meaningfulness, sense of responsibility, and feeling of knowing how one is performing, which subsequently affects a person’s well-being as identified in assessments of motivation, satisfaction, improved performance, and reduced withdrawal intentions and behaviors. Extending this argument to the stress models, it can be deduced that reducing uncertainty or perceived unfairness that may be associated with a person’s perception of these work characteristics, as well as making changes to physical characteristics of the environment (e.g., lighting, seating, desk, air quality), nature of work (e.g., job responsibilities, roles, decision-making latitude), and organizational arrangements (e.g., reporting structure and feedback mechanisms), can help mitigate against numerous ill-health consequences and reduced organizational performance. In fact, Fried et al. ( 2013 ) showed that healthy patients of a medical clinic whose jobs were excessively low (i.e., monotonous) or excessively high (i.e., overstimulating) on job enrichment (as measured by the JDS) had greater abdominal obesity than those whose jobs were optimally enriched. By taking stock of employees’ perceptions of the current work situation, managers might think about ways to enhance employees’ coping toolkit, such as training on how to deal with difficult clients or creating stimulating opportunities when jobs have low levels of enrichment.

Participatory Action Research Interventions

Participatory action research (PAR) is an intervention wherein, through group discussions, employees help to identify and define problems in organizational structure, processes, policies, practices, and reward structures, as well as help to design, implement, and evaluate success of solutions. PAR is in itself an intervention, but its goal is to design interventions to eliminate or reduce work-related factors that are impeding performance and causing people to be unwell. An example of a successful primary intervention, utilizing principles of PAR and driven by the JD-C and JD-C/S stress frameworks is Health Circles (HCs; Aust & Ducki, 2004 ).

HCs, developed in Germany in the 1980s, were popular practices in industries, such as metal, steel, and chemical, and service. Similar to other problem-solving practices, such as quality circles, HCs were based on the assumptions that employees are the experts of their jobs. For this reason, to promote employee well-being, management and administrators solicited suggestions and ideas from the employees to improve occupational health, thereby increasing employees’ job control. HCs also promoted communication between managers and employees, which had a potential to increase social support. With more control and support, employees would experience less strains and better occupational well-being.

Employing the three-steps of (1) problem analysis (i.e., diagnosis or discovery through data generated from organizational records of absenteeism length, frequency, rate, and reason and employee survey), (2) HC meetings (6 to 10 meetings held over several months to brainstorm ideas to improve occupational safety and health concerns identified in the discovery phase), and (3) HC evaluation (to determine if desired changes were accomplished and if employees’ reports of stressors and strains changed after the course of 15 months), improvements were to be expected (Aust & Ducki, 2004 ). Aust and Ducki ( 2004 ) reviewed 11 studies presenting 81 health circles in 30 different organizations. Overall study participants had high satisfaction with the HCs practices. Most companies acted upon employees’ suggestions (e.g., improving driver’s seat and cab, reducing ticket sale during drive, team restructuring and job rotation to facilitate communication, hiring more employees during summer time, and supervisor training program to improve leadership and communication skills) to improve work conditions. Thus, HCs represent a successful theory-grounded intervention to routinely improve employees’ occupational health.

Physical Setting

The physical environment or physical workspace has an enormous impact on individuals’ well-being, attitudes, and interactions with others, as well as on the implications on innovation and well-being (Oksanen & Ståhle, 2013 ; Vischer, 2007 ). In a study of 74 new product development teams (total of 437 study respondents) in Western Europe, Chong, van Eerde, Rutte, and Chai ( 2012 ) found that when teams were faced with challenge time pressures, meaning the teams had a strong interest and desire in tackling complex, but engaging tasks, when they were working proximally close with one another, team communication improved. Chong et al. assert that their finding aligns with prior studies that have shown that physical proximity promotes increased awareness of other team members, greater tendency to initiate conversations, and greater team identification. However, they also found that when faced with hindrance time pressures, physical proximity related to low levels of team communication, but when hindrance time pressure was low, team proximity had an increasingly greater positive relationship with team communication.

In addition to considering the type of work demand teams must address, other physical workspace considerations include whether people need to work collaboratively and synchronously or independently and remotely (or a combination thereof). Consideration needs to be given to how company contributors would satisfy client needs through various modes of communication, such as email vs. telephone, and whether individuals who work by a window might need shading to block bright sunlight from glaring on their computer screens. Finally, people who have to use the telephone for extensive periods of time would benefit from earphones to prevent neck strains. Most physical stressors are rather simple to rectify. However, companies are often not aware of a problem until after a problem arises, such as when a person’s back is strained from trying to move heavy equipment. Companies then implement strategies to remediate the environmental stressor. With the help of human factors, and organizational and office design consultants, many of the physical barriers to optimal performance can be prevented (Rousseau & Aubé, 2010 ). In a study of 215 French-speaking Canadian healthcare employees, Rousseau and Aubé ( 2010 ) found that although supervisor instrumental support positively related with affective commitment to the organization, the relationship was even stronger for those who reported satisfaction with the ambient environment (i.e., temperature, lighting, sound, ventilation, and cleanliness).

Secondary Interventions (Coping)

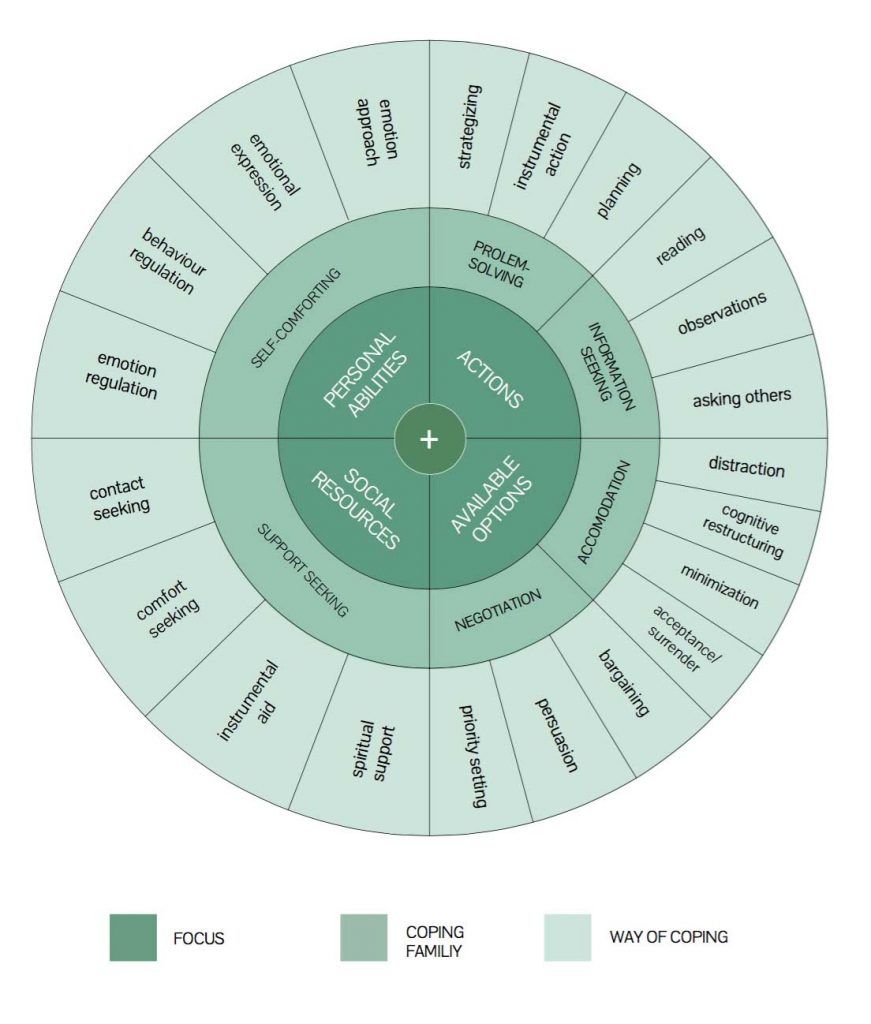

Secondary interventions, also referred to as coping, focus on resources people can use to mitigate the risk of work-related illness or workplace injury. Resources may include properties related to social resources, behaviors, and cognitive structures. Each of these resource domains may be employed to cope with stressors. Monat and Lazarus ( 1991 ) summarize the definition of coping as “an individual’s efforts to master demands (or conditions of harm, threat, or challenge) that are appraised (or perceived) as exceeding or taxing his or her resources” (p. 5). To master demands requires use of the aforementioned resources. Secondary interventions help employees become aware of the psychological, physical, and behavioral responses that may occur from the stressors presented in their working environment. Secondary interventions help a person detect and attend to stressors and identify resources for and ways of mitigating job strains. Often, coping strategies are learned skills that have a cognitive foundation and serve important functions in improving people’s management of stressors (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991 ). Coping is effortful, but with practice it becomes easier to employ. This idea is the foundation for understanding the role of resilience in coping with stressors. However, “not all adaptive processes are coping. Coping is a subset of adaptational activities that involves effort and does not include everything that we do in relating to the environment” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991 , p. 198). Furthermore, sometimes to cope with a stressor, a person may call upon social support sources to help with tangible materials or emotional comfort. People call upon support resources because they help to restructure how a person approaches or thinks about the stressor.

Most secondary interventions are aimed at helping the individual, though companies, as a policy, might require all employees to partake in training aimed at increasing employees’ awareness of and skills aimed at handling difficult situations vis à vis company channels (e.g., reporting on sexual harassment or discrimination). Furthermore, organizations might institute mentoring programs or work groups to address various work-related matters. These programs employ awareness-raising activities, stress-education, or skills training (cf., Bhagat, Segovis, & Nelson, 2012 ), which include development of skills in problem-solving, understanding emotion-focused coping, identifying and using social support, and enhancing capacity for resilience. The aim of these programs, therefore, is to help employees proactively review their perceptions of psychological, physical, and behavioral job-related strains, thereby extending their resilience, enabling them to form a personal plan to control stressors and practice coping skills (Cooper, Dewe, & O’Driscoll, 2011 ).

Often these stress management programs are instituted after an organization has observed excessive absenteeism and work-related performance problems and, therefore, are sometimes categorized as a tertiary stress management intervention or even a primary (prevention) intervention. However, the skills developed for coping with stressors also place the programs in secondary stress management interventions. Example programs that are categorized as tertiary or primary stress management interventions may also be secondary stress management interventions (see Figure 1 ), and these include lifestyle advice and planning, stress inoculation training, simple relaxation techniques, meditation, basic trainings in time management, anger management, problem-solving skills, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Corporate wellness programs also fall under this category. In other words, some programs could be categorized as primary, secondary, or tertiary interventions depending upon when the employee (or organization) identifies the need to implement the program. For example, time management practices could be implemented as a means of preventing some stressors, as a way to cope with mounting stressors, or as a strategy to mitigate symptoms of excessive of stressors. Furthermore, these programs can be administered at the individual level or group level. As related to secondary interventions, these programs provide participants with opportunities to develop and practice skills to cognitively reappraise the stressor(s); to modify their perspectives about stressors; to take time out to breathe, stretch, meditate, relax, and/or exercise in an attempt to support better decision-making; to articulate concerns and call upon support resources; and to know how to say “no” to onslaughts of requests to complete tasks. Participants also learn how to proactively identify coping resources and solve problems.

According to Cooper, Dewe, and O’Driscoll ( 2001 ), secondary interventions are successful in helping employees modify or strengthen their ability to cope with the experience of stressors with the goal of mitigating the potential harm the job stressors may create. Secondary interventions focus on individuals’ transactions with the work environment and emphasize the fit between a person and his or her environment. However, researchers have pointed out that the underlying assumption of secondary interventions is that the responsibility for coping with the stressors of the environment lies within individuals (Quillian-Wolever & Wolever, 2003 ). If companies cannot prevent the stressors in the first place, then they are, in part, responsible for helping individuals develop coping strategies and informing employees about programs that would help them better cope with job stressors so that they are able to fulfill work assignments.

Stress management interventions that help people learn to cope with stressors focus mainly on the goals of enabling problem-resolution or expressing one’s emotions in a healthy manner. These goals are referred to as problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980 ; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978 ), and the person experiencing the stressors as potential threat is the agent for change and the recipient of the benefits of successful coping (Hobfoll, 1998 ). In addition to problem-focused and emotion-focused coping approaches, social support and resilience may be coping resources. There are many other sources for coping than there is room to present here (see e.g., Cartwright & Cooper, 2005 ); however, the current literature has primarily focused on these resources.

Problem-Focused Coping

Problem-focused or direct coping helps employees remove or reduce stressors in order to reduce their strain experiences (Bhagat et al., 2012 ). In problem-focused coping employees are responsible for working out a strategic plan in order to remove job stressors, such as setting up a set of goals and engaging in behaviors to meet these goals. Problem-focused coping is viewed as an adaptive response, though it can also be maladaptive if it creates more problems down the road, such as procrastinating getting work done or feigning illness to take time off from work. Adaptive problem-focused coping negatively relates to long-term job strains (Higgins & Endler, 1995 ). Discussion on problem-solving coping is framed from an adaptive perspective.

Problem-focused coping is featured as an extension of control, because engaging in problem-focused coping strategies requires a series of acts to keep job stressors under control (Bhagat et al., 2012 ). In the stress literature, there are generally two ways to categorize control: internal versus external locus of control, and primary versus secondary control. Locus of control refers to the extent to which people believe they have control over their own life (Rotter, 1966 ). People high in internal locus of control believe that they can control their own fate whereas people high in external locus of control believe that outside factors determine their life experience (Rotter, 1966 ). Generally, those with an external locus of control are less inclined to engage in problem-focused coping (Strentz & Auerbach, 1988 ). Primary control is the belief that people can directly influence their environment (Alloy & Abramson, 1979 ), and thus they are more likely to engage in problem-focused coping. However, when it is not feasible to exercise primary control, people search for secondary control, with which people try to adapt themselves into the objective environment (Rothbaum, Weisz, & Snyder, 1982 ).

Emotion-Focused Coping

Emotion-focused coping, sometimes referred to as palliative coping, helps employees reduce strains without the removal of job stressors. It involves cognitive or emotional efforts, such as talking about the stressor or distracting oneself from the stressor, in order to lessen emotional distress resulting from job stressors (Bhagat et al., 2012 ). Emotion-focused coping aims to reappraise and modify the perceptions of a situation or seek emotional support from friends or family. These methods do not include efforts to change the work situation or to remove the job stressors (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991 ). People tend to adopt emotion-focused coping strategies when they believe that little or nothing can be done to remove the threatening, harmful, and challenging stressors (Bhagat et al., 2012 ), such as when they are the only individuals to have the skills to get a project done or they are given increased responsibilities because of the unexpected departure of a colleague. Emotion-focused coping strategies include (1) reappraisal of the stressful situation, (2) talking to friends and receiving reassurance from them, (3) focusing on one’s strength rather than weakness, (4) optimistic comparison—comparing one’s situation to others’ or one’s past situation, (5) selective ignoring—paying less attention to the unpleasant aspects of one’s job and being more focused on the positive aspects of the job, (6) restrictive expectations—restricting one’s expectations on job satisfaction but paying more attention to monetary rewards, (7) avoidance coping—not thinking about the problem, leaving the situation, distracting oneself, or using alcohol or drugs (e.g., Billings & Moos, 1981 ).

Some emotion-focused coping strategies are maladaptive. For example, avoidance coping may lead to increased level of job strains in the long run (e.g., Parasuraman & Cleek, 1984 ). Furthermore, a person’s ability to cope with the imbalance of performing work to meet organizational expectations can take a toll on the person’s health, leading to physiological consequences such as cardiovascular disease, sleep disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, and diabetes (Fried et al., 2013 ; Siegrist, 2010 ; Toker, Shirom, Melamed, & Armon, 2012 ; Willert, Thulstrup, Hertz, & Bonde, 2010 ).

Comparing Coping Strategies across Cultures

Most coping research is conducted in individualistic, Western cultures wherein emotional control is emphasized and both problem-solving focused coping and primary control are preferred (Bhagat et al., 2010 ). However, in collectivistic cultures, emotion-focused coping and use of secondary control may be preferred and may not necessarily carry a negative evaluation (Bhagat et al., 2010 ). For example, African Americans are more likely to use emotion-focused coping than non–African Americans (Knight, Silverstein, McCallum, & Fox, 2000 ), and among women who experienced sexual harassment, Anglo American women were less likely to employ emotion focused coping (i.e., avoidance coping) than Turkish women and Hispanic American women, while Hispanic women used more denial than the other two groups (Wasti & Cortina, 2002 ).

Thus, whereas problem-focused coping is venerated in Western societies, emotion-focused coping may be more effective in reducing strains in collectivistic cultures, such as China, Japan, and India (Bhagat et al., 2010 ; Narayanan, Menon, & Spector, 1999 ; Selmer, 2002 ). Indeed, Swedish participants reported more problem-focused coping than did Chinese participants (Xiao, Ottosson, & Carlsson, 2013 ), American college students engaged in more problem-focused coping behaviors than did their Japanese counterparts (Ogawa, 2009 ), and Indian (vs. Canadian) students reported more emotion-focused coping, such as seeking social support and positive reappraisal (Sinha, Willson, & Watson, 2000 ). Moreover, Glazer, Stetz, and Izso ( 2004 ) found that internal locus of control was more predominant in individualistic cultures (United Kingdom and United States), whereas external locus of control was more predominant in communal cultures (Italy and Hungary). Also, internal locus of control was associated with less job stress, but more so for nurses in the United Kingdom and United States than Italy and Hungary. Taken together, adoption of coping strategies and their effectiveness differ significantly across cultures. The extent to which a coping strategy is perceived favorably and thus selected or not selected is not only a function of culture, but also a person’s sociocultural beliefs toward the coping strategy (Morimoto, Shimada, & Ozaki, 2013 ).

Social Support

Social support refers to the aid an entity gives to a person. The source of the support can be a single person, such as a supervisor, coworker, subordinate, family member, friend, or stranger, or an organization as represented by upper-level management representing organizational practices. The type of support can be instrumental or emotional. Instrumental support, including informational support, refers to that which is tangible, such as data to help someone make a decision or colleagues’ sick days so one does not lose vital pay while recovering from illness. Emotional support, including esteem support, refers to the psychological boost given to a person who needs to express emotions and feel empathy from others or to have his or her perspective validated. Beehr and Glazer ( 2001 ) present an overview of the role of social support on the stressor-strain relationship and arguments regarding the role of culture in shaping the utility of different sources and types of support.

Meaningfulness and Resilience

Meaningfulness reflects the extent to which people believe their lives are significant, purposeful, goal-directed, and fulfilling (Glazer, Kożusznik, Meyers, & Ganai, 2014 ). When faced with stressors, people who have a strong sense of meaning in life will also try to make sense of the stressors. Maintaining a positive outlook on life stressors helps to manage emotions, which is helpful in reducing strains, particularly when some stressors cannot be problem-solved (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991 ). Lazarus and Folkman ( 1991 ) emphasize that being able to reframe threatening situations can be just as important in an adaptation as efforts to control the stressors. Having a sense of meaningfulness motivates people to behave in ways that help them overcome stressors. Thus, meaningfulness is often used in the same breath as resilience, because people who are resilient are often protecting that which is meaningful.

Resilience is a personality state that can be fortified and enhanced through varied experiences. People who perceive their lives are meaningful are more likely to find ways to face adversity and are therefore more prone to intensifying their resiliency. When people demonstrate resilience to cope with noxious stressors, their ability to be resilient against other stressors strengthens because through the experience, they develop more competencies (Glazer et al., 2014 ). Thus, fitting with Hobfoll’s ( 1989 , 2001 ) COR theory, meaningfulness and resilience are psychological resources people attempt to conserve and protect, and employ when necessary for making sense of or coping with stressors.

Tertiary Interventions (Stress Management)

Stress management refers to interventions employed to treat and repair harmful repercussions of stressors that were not coped with sufficiently. As Lazarus and Folkman ( 1991 ) noted, not all stressors “are amenable to mastery” (p. 205). Stressors that are unmanageable and lead to strains require interventions to reverse or slow down those effects. Workplace interventions might focus on the person, the organization, or both. Unfortunately, instead of looking at the whole system to include the person and the workplace, most companies focus on the person. Such a focus should not be a surprise given the results of van der Klink, Blonk, Schene, and van Dijk’s ( 2001 ) meta-analysis of 48 experimental studies conducted between 1977 and 1996 . They found that of four types of tertiary interventions, the effect size for cognitive-behavioral interventions and multimodal programs (e.g., the combination of assertive training and time management) was moderate and the effect size for relaxation techniques was small in reducing psychological complaints, but not turnover intention related to work stress. However, the effects of (the five studies that used) organization-focused interventions were not significant. Similarly, Richardson and Rothstein’s ( 2008 ) meta-analytic study, including 36 experimental studies with 55 interventions, showed a larger effect size for cognitive-behavioral interventions than relaxation, organizational, multimodal, or alternative. However, like with van der Klink et al. ( 2001 ), Richardson and Rothstein ( 2008 ) cautioned that there were few organizational intervention studies included and the impact of interventions were determined on the basis of psychological outcomes and not physiological or organizational outcomes. Van der Klink et al. ( 2001 ) further expressed concern that organizational interventions target the workplace and that changes in the individual may take longer to observe than individual interventions aimed directly at the individual.

The long-term benefits of individual focused interventions are not yet clear either. Per Giga, Cooper, and Faragher ( 2003 ), the benefits of person-directed stress management programs will be short-lived if organizational factors to reduce stressors are not addressed too. Indeed, LaMontagne, Keegel, Louie, Ostry, and Landsbergis ( 2007 ), in their meta-analysis of 90 studies on stress management interventions published between 1990 and 2005 , revealed that in relation to interventions targeting organizations only, and interventions targeting individuals only, interventions targeting both organizations and individuals (i.e. the systems approach) had the most favorable positive effects on both the organizations and the individuals. Furthermore, the organization-level interventions were effective at both the individual and organization levels, but the individual-level interventions were effective only at the individual level.

Individual-Focused Stress Management

Individual-focused interventions concentrate on improving conditions for the individual, though counseling programs emphasize that the worker is in charge of reducing “stress,” whereas role-focused interventions emphasize activities that organizations can guide to actually reduce unnecessary noxious environmental factors.

Individual-Focused Stress Management: Employee Assistance Programs

When stress become sufficiently problematic (which is individually gauged or attended to by supportive others) in a worker’s life, employees may utilize the short-term counseling services or referral services Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) provide. People who utilize the counseling services may engage in cognitive behavioral therapy aimed at changing the way people think about the stressors (e.g., as challenge opportunity over threat) and manage strains. Example topics that may be covered in these therapy sessions include time management and goal setting (prioritization), career planning and development, cognitive restructuring and mindfulness, relaxation, and anger management. In a study of healthcare workers and teachers who participated in a 2-day to 2.5-day comprehensive stress management training program (including 26 topics on identifying, coping with, and managing stressors and strains), Siu, Cooper, and Phillips ( 2013 ) found psychological and physical improvements were self-reported among the healthcare workers (for which there was no control group). However, comparing an intervention group of teachers to a control group of teachers, the extent of change was not as visible, though teachers in the intervention group engaged in more mastery recovery experiences (i.e., they purposefully chose to engage in challenging activities after work).

Individual-Focused Stress Management: Mindfulness

A popular therapy today is to train people to be more mindful, which involves helping people live in the present, reduce negative judgement of current and past experiences, and practicing patience (Birnie, Speca, & Carlson, 2010 ). Mindfulness programs usually include training on relaxation exercises, gentle yoga, and awareness of the body’s senses. In one study offered through the continuing education program at a Canadian university, 104 study participants took part in an 8-week, 90 minute per group (15–20 participants per) session mindfulness program (Birnie et al., 2010 ). In addition to body scanning, they also listened to lectures on incorporating mindfulness into one’s daily life and received a take-home booklet and compact discs that guided participants through the exercises studied in person. Two weeks after completing the program, participants’ mindfulness attendance and general positive moods increased, while physical, psychological, and behavioral strains decreased. In another study on a sample of U.K. government employees, study participants receiving three sessions of 2.5 to 3 hours each training on mindfulness, with the first two sessions occurring in consecutive weeks and the third occurring about three months later, Flaxman and Bond ( 2010 ) found that compared to the control group, the intervention group showed a decrease in distress levels from Time 1 (baseline) to Time 2 (three months after first two training sessions) and Time 1 to Time 3 (after final training session). Moreover, of the mindfulness intervention study participants who were clinically distressed, 69% experienced clinical improvement in their psychological health.

Individual-Focused Stress Management: Biofeedback/Imagery/Meditation/Deep Breathing

Biofeedback uses electronic equipment to inform users about how their body is responding to tension. With guidance from a therapist, individuals then learn to change their physiological responses so that their pulse normalizes and muscles relax (Norris, Fahrion, & Oikawa, 2007 ). The therapist’s guidance might include reminders for imagery, meditation, body scan relaxation, and deep breathing. Saunders, Driskell, Johnston, and Salas’s ( 1996 ) meta-analysis of 37 studies found that imagery helped reduce state and performance anxiety. Once people have been trained to relax, reminder triggers may be sent through smartphone push notifications (Villani et al., 2013 ).

Smartphone technology can also be used to support weight loss programs, smoking cessation programs, and medication or disease (e.g., diabetes) management compliance (Heron & Smyth, 2010 ; Kannampallil, Waicekauskas, Morrow, Kopren, & Fu, 2013 ). For example, smartphones could remind a person to take medications or test blood sugar levels or send messages about healthy behaviors and positive affirmations.

Individual-Focused Stress Management: Sleep/Rest/Respite

Workers today sleep less per night than adults did nearly 30 years ago (Luckhaupt, Tak, & Calvert, 2010 ; National Sleep Foundation, 2005 , 2013 ). In order to combat problems, such as increased anxiety and cardiovascular artery disease, associated with sleep deprivation and insufficient rest, it is imperative that people disconnect from their work at least one day per week or preferably for several weeks so that they are able to restore psychological health (Etzion, Eden, & Lapidot, 1998 ; Ragsdale, Beehr, Grebner, & Han, 2011 ). When college students engaged in relaxation-type activities, such as reading or watching television, over the weekend, they experienced less emotional exhaustion and greater general well-being than students who engaged in resources-consuming activities, such as house cleaning (Ragsdale et al., 2011 ). Additional research and future directions for research are reviewed and identified in the work of Sonnentag ( 2012 ). For example, she asks whether lack of ability to detach from work is problematic for people who find their work meaningful. In other words, are negative health consequences only among those who do not take pleasure in their work? Sonnetag also asks how teleworkers detach from their work when engaging in work from the home. Ironically, one of the ways that companies are trying to help with the challenges of high workload or increased need to be available to colleagues, clients, or vendors around the globe is by offering flexible work arrangements, whereby employees who can work from home are given the opportunity to do so. Companies that require global interactions 24-hours per day often employ this strategy, but is the solution also a source of strain (Glazer, Kożusznik, & Shargo, 2012 )?

Individual-Focused Stress Management: Role Analysis

Role analysis or role clarification aims to redefine, expressly identify, and align employees’ roles and responsibilities with their work goals. Through role negotiation, involved parties begin to develop a new formal or informal contract about expectations and define resources needed to fulfill those expectations. Glazer has used this approach in organizational consulting and, with one memorable client engagement, found that not only were the individuals whose roles required deeper re-evaluation happier at work (six months later), but so were their subordinates. Subordinates who once characterized the two partners as hostile and akin to a couple going through a bad divorce, later referred to them as a blissful pair. Schaubroeck, Ganster, Sime, and Ditman ( 1993 ) also found in a three-wave study over a two-year period that university employees’ reports of role clarity and greater satisfaction with their supervisor increased after a role clarification exercise of top managers’ roles and subordinates’ roles. However, the intervention did not have any impact on reported physical symptoms, absenteeism, or psychological well-being. Role analysis is categorized under individual-focused stress management intervention because it is usually implemented after individuals or teams begin to demonstrate poor performance and because the intervention typically focuses on a few individuals rather than an entire organization or group. In other words, the intervention treats the person’s symptoms by redefining the role so as to eliminate the stimulant causing the problem.

Organization-Focused Stress Management

At the organizational level, companies that face major declines in productivity and profitability or increased costs related to healthcare and disability might be motivated to reassess organizational factors that might be impinging on employees’ health and well-being. After all, without healthy workers, it is not possible to have a healthy organization. Companies may choose to implement practices and policies that are expected to help not only the employees, but also the organization with reduced costs associated with employee ill-health, such as medical insurance, disability payments, and unused office space. Example practices and policies that may be implemented include flexible work arrangements to ensure that employees are not on the streets in the middle of the night for work that can be done from anywhere (such as the home), diversity programs to reduce stress-induced animosity and prejudice toward others, providing only healthy food choices in cafeterias, mandating that all employees have physicals in order to receive reduced prices for insurance, company-wide closures or mandatory paid time off, and changes in organizational visioning.

Organization-Focused Stress Management: Organizational-Level Occupational Health Interventions

As with job design interventions that are implemented to remediate work characteristics that were a source of unnecessary or excessive stressors, so are organizational-level occupational health (OLOH) interventions. As with many of the interventions, its placement as a primary or tertiary stress management intervention may seem arbitrary, but when considering the goal and target of change, it is clear that the intervention is implemented in response to some ailing organizational issues that need to be reversed or stopped, and because it brings in the entire organization’s workforce to address the problems, it has been placed in this category. There are several more case studies than empirical studies on the topic of whole system organizational change efforts (see example case studies presented by the United Kingdom’s Health and Safety Executive). It is possible that lack of published empirical work is not so much due to lack of attempting to gather and evaluate the data for publication, but rather because the OLOH interventions themselves never made it to the intervention stage, the interventions failed (Biron, Gatrell, & Cooper, 2010 ), or the level of evaluation was not rigorous enough to get into empirical peer-review journals. Fortunately, case studies provide some indication of the opportunities and problems associated with OLOH interventions.

One case study regarding Cardiff and Value University Health Board revealed that through focus group meetings with members of a steering group (including high-level managers and supported by top management) and facilitated by a neutral, non-judgemental organizational health consultant, ideas for change were posted on newsprint, discussed, and areas in the organization needing change were identified. The intervention for giving voice to people who initially had little already had a positive effect on the organization, as absence decreased by 2.09% and 6.9% merely 12 and 18 months, respectively, after the intervention. Translated in financial terms, the 6.9% change was equivalent to a quarterly savings of £80,000 (Health & Safety Executive, n.d. ). Thus, focusing on the context of change and how people will be involved in the change process probably helped the organization realize improvements (Biron et al., 2010 ). In a recent and rare empirical study, employing both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, Sørensen and Holman ( 2014 ) utilized PAR in order to plan and implement an OLOH intervention over the course of 14 months. Their study aimed to examine the effectiveness of the PAR process in reducing workers’ work-related and social or interpersonal-related stressors that derive from the workplace and improving psychological, behavioral, and physiological well-being across six Danish organizations. Based on group dialogue, 30 proposals for change were proposed, all of which could be categorized as either interventions to focus on relational factors (e.g., management feedback improvement, engagement) or work processes (e.g., reduced interruptions, workload, reinforcing creativity). Of the interventions that were implemented, results showed improvements on manager relationship quality and reduced burnout, but no changes with respect to work processes (i.e., workload and work pace) perhaps because the employees already had sufficient task control and variety. These findings support Dewe and Kompier’s ( 2008 ) position that occupational health can be reinforced through organizational policies that reinforce quality jobs and work experiences.

Organization-Focused Stress Management: Flexible Work Arrangements