Reporting and Presenting Research Findings

Apr 03, 2012

680 likes | 1.77k Views

Reporting and Presenting Research Findings. Effective Writing. Clear, concise, direct Thoughts are complete Attention given to details such as grammar, spelling Flow of thoughts. Quantitative Research Reporting.

Share Presentation

- support team

- comprehensive research report

- discuss method

- spss printouts

- third quarter performance

Presentation Transcript

Effective Writing • Clear, concise, direct • Thoughts are complete • Attention given to details such as grammar, spelling • Flow of thoughts

Quantitative Research Reporting • Recall, the opening sections of the proposal should be the foundation of the section introduction • Background • Research Problem (w/ research concepts) • Methodology & Procedure • Sample frame • Research Instruments

Reporting The Findings • Frame a percentages and proportions in absolute numerical terms “Sixty percent (n= 18) of the sample either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that the holiday season tends to cause a great deal of anxiety.”

The Use of Data In Reports • Tables should support discussion points “Third quarter performance peaked dramatically in the East relative to the West and North. Overall brand performance remained stagnant from region to region in the first, second, and fourth quarters.”

Discussion & Interpretation • Graphics, tables in the context of the written presentation should be minimized • More is not necessarily better

Discussion & Interpretation • Revisit the Research Problem Statement • Organize discussion around concepts of interest, research concepts • Don’t just spout numbers; tell the story behind the data • Highlight, topline, and synthesize information

Discussion & Interpretation • Leave the reader with food for thought • What does the quantitative data suggest? • Based on complete evidence in the data gathered, what conclusions can be drawn? • What recommendations, suggestions can be made to address the marketing problem?

The Conclusion & Recommendations • Make proactive recommendations for marketing the product based on the evidence uncovered in research • Look for opportunities to appeal to the target market • Are there benefits that should be addressed? • Are there attributes that have unique appeal?

The Conclusion & Recommendations • Look for opportunities in target market segmentation • Are there segmentation considerations? • What should the message strategy be?

Appendix References • Cite Exhibit tables in a separate appendix section • Each table labeled with a numerical identifier • Columns are clearly labeled • Reminder: SPSS printouts should be not be bound with the report

The Use of Data In Reports • Bar charts are appropriate for category comparisons • Pie charts visually represent portions of the whole

The Written Presentation – Part II • Organization of the written presentation for Quantitative Research should follow a recommended format

The Written Presentation – Part II • Introduction/Background • Research Objectives • Concepts of Interest • Research Method • Discuss method, instrument, and implementation of method (e.g., means for recruiting, ) • Research Sample • Discuss sample frame, number recruited, profile of participants • Remember: Classification questions

The Written Presentation – Part II • Findings • Organize presentation sub-topics by COI • Discuss questions that fall logically into COI area • Quantitative Research Conclusions • Limitations • Recommendations for Future Research

The Written Presentation – Part II • Marketing recommendations • Recall the purpose of the research exercise was “to understand college students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors” toward the Nintendo Wii • Based on what your team found, what can you offer Nintendo in terms of research insights that can be used for marketing?

Remember • The final project should: • Reflect a comprehensive research report (including secondary, qualitative, & quantitative) • Include recruitment screeners from qualitative research

The Oral Presentation

Tips for the Presentation • All members need not present, but all must attend • Put the strongest person(s) forward • Use others’ strengths where necessary • Support your team members • Support other teams

Presentation Do’s in 8 minutes or less • Do introduce yourself and your team members and your project focus early in the presentation • Do establish an outline that will be used to present your research • Do highlight, summarize the process and findings from research • Do rehearse before the presentation

The Biggest Do • Be professional, but DO HAVE FUN

Presentation Don’ts • Don’t hide behind an avalanche of slides/overhead transparencies • Don’t be a distraction to yourself or to the speaker (Be attentive) • Don’t stop the presentation because the “script,” or the technology, isn’t working • It’s not about the show, its about the information • No one knows the data better than you and your team

Presentation FAQs • Can we use Powerpoint technology to make the presentation? • Are all group member required to present? • Will the instructor need a copy of our presentation in addition to the report?

Course FAQs • When will I get my final grade? • How should I access my grade? • Can I email or call you earlier than the posting date to get my grade? • Will I be able to see the final project after the grade is in? • Can I or my team have the final project returned at the end of the semester?

Details • Office hours during the exam period • Please review your scores thoroughly before Friday, December 12, to ensure accuracy in points total

- More by User

Presenting Your Findings

Presenting Your Findings Oral & Poster Presentations Frances L. Chumney, Summer 2005 Oral Presentations Things That Matter Contents (duh!) Graphs, Figures Images Visual Appeal Graphics & Illustrations You Contents Title Slide Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion

1.36k views • 44 slides

Writing and presenting Research

Writing and presenting Research. Lecture 29 th. RECAP. Getting started with writing. Practical hints Create time for your writing Write when your mind is fresh Find a regular writing place Set goals and achieve them Use word processing Generate a plan for the report

281 views • 17 slides

REPORTING AND PRESENTING RESEARCH

Chapter 12. REPORTING AND PRESENTING RESEARCH. Learning Objectives : Convey the importance of effective communication to research success. Describe the elements of a research proposal. Provide an overview of effective research reports.

352 views • 14 slides

Understanding and presenting your findings .

Understanding and presenting your findings . Present the basics to tell a story. Do not present advanced statistics and confusion. Today is about creating business intelligence.

855 views • 73 slides

Reporting Research Findings

Reporting Research Findings.

566 views • 26 slides

Interpreting results and presenting findings

Interpreting results and presenting findings. Intermediate Food Security Analysis Training Rome, July 2010. Overview. Determining the question you want to answer Using your analysis plan Interpreting results from SPSS Visualizing findings Writing-up your analysis.

354 views • 21 slides

Research ethics and presenting data

Research ethics and presenting data. Managed Access Training I 29 July 2013. Research ethics. Definition: A system of moral principles. The recognized rules of human conduct

290 views • 11 slides

Research Findings

Research Findings. Ideas and Inspiration Project 1. LOGO IDEAS. Green Tech Resource Center. North Florida Center. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G3wemL27KcM&noredirect=1. Resource Library. Idea Starters. Floating wall dividers – textiles Castors on everything

290 views • 7 slides

Reporting and Using Evaluation Findings

Reporting and Using Evaluation Findings. The Tragedy of First Position. PLAN. COMMUNICATE. ASSESS IMPACT. PLAN. what is the objective?. keep it simple. COMMUNICATE. C is for contrafibularity. Link to Garden Hill poultry video. Wab kinew rapping

311 views • 18 slides

Chapter 4: Reporting and Presenting Results

2. Chapter 4: Reporting and Presenting Results. 2. Chapter 4: Reporting and Presenting Results. Objectives. Use a JMP journal for a presentation. Journal Presentations. Using a Journal for Presentations. This demonstration illustrates the concepts discussed previously. Exercise.

473 views • 23 slides

Presenting Your Findings. Oral & Poster Presentations. Frances L. Chumney, Summer 2005. Oral Presentations Things That Matter. Contents (duh!) Graphs, Figures Images Visual Appeal Graphics & Illustrations You. Contents. Title Slide Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion

623 views • 44 slides

Reporting research

Reporting research. Where to report it. Introduction. Results from research must be communicated to the world To assist future researchers & to add to the body of knowledge To justify further funding/support! We do this via Journals & conferences Workshops & seminars Reports Books.

256 views • 16 slides

Presenting Research Data

Presenting Research Data. Monday, March 15, 11:45 – 1:45 Present projects and studies with charts and graphs and for poster presentations. Randy Graff, PhD 352.273.5051. Presenting Research Data. How To Vote via Texting. EXAMPLE. How To Vote via Poll4.com. EXAMPLE.

1.24k views • 93 slides

Presenting Research

Presenting Research. Dr. Anjum Naveed & Dr. Peter Bloodsworth. Discussion: What is research?. Discussion: How can research outcomes be communicated to others?. How to Make a Persuasive Argument (researcher’s perspective). Getting Started. Before you start: Have your literature review handy

324 views • 15 slides

Reporting and Presenting Data

Reporting and Presenting Data. Washington School Counselors Association John Carey National Center for School Counseling Outcome Research www.cscor.org. Reporting and Presenting Data. 1. Who is the audience? How much information will you present?

858 views • 69 slides

Presenting Action Research

Presenting Action Research. Purpose. Provide an overview of the issue or the purpose for your action research. What are you trying to teach? (E.g.)

212 views • 8 slides

Presenting your research

Presenting your research. content, structure and technique. getting content right. Similar to an essay adequate & appropriate research indicate range of evidence evaluate your sources Referencing and bibliography Different from an essay A few key points engages directly with audience

184 views • 9 slides

Presenting Research Data. Thursday, March 12, 11:00 – 12:00 Create presentations with charts and graphs and for poster presentations. Randy Graff, PhD 352.273.5051. Charts. Chart - Create. Chart – Paste Special. Chart – Paste Special. Graphs. Graphs - Create. Graphs – Create and Edit.

290 views • 18 slides

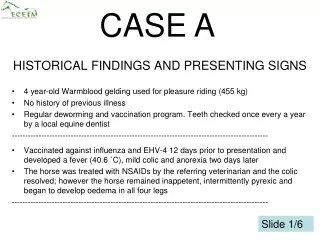

HISTORICAL FINDINGS AND PRESENTING SIGNS

HISTORICAL FINDINGS AND PRESENTING SIGNS. 4 year-old Warmblood gelding used for pleasure riding (455 kg) No history of previous illness Regular deworming and vaccination program. Teeth checked once every a year by a local equine dentist

140 views • 13 slides

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

PRESENTATION AND DISCUSSION OF RESEARCH FINDINGS

Published by Augustus Floyd Modified over 6 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "PRESENTATION AND DISCUSSION OF RESEARCH FINDINGS"— Presentation transcript:

Critical Reading Strategies: Overview of Research Process

Personal Project REPORT.

WRITING RESEARCH PAPERS Puvaneswary Murugaiah. INTRODUCTION TO WRITING PAPERS Conducting research is academic activity Research must be original work.

Dissertation Writing.

Chapter 12 – Strategies for Effective Written Reports

S OCIAL S CIENCE R ESEARCH HPD 4C W ORKING WITH S CHOOL – A GE C HILDREN AND A DOLESCENTS M RS. F ILINOV.

Reporting results: APA style Psych 231: Research Methods in Psychology.

ALEC 604: Writing for Professional Publication

EMPRICAL RESEARCH REPORTS

Literature Review and Parts of Proposal

Objective 6.01 Objective 6.01 Explain the abilities to communicate effectively in a technological world Technical Report Writing List the part of a technical.

“……What has TV guide got to with news?”. “In order to have a successful report you must assemble the facts and opinions from a variety of sources, review.

Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Application, 9 th edition. Gay, Mills, & Airasian © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

Writing the “Results” & “Discussion” sections Awatif Alam Professor Community Medicine Medical College/ KSU.

How to read a scientific paper

Thesis Statement-Examples

The Proposal AEE 804 Spring 2002 Revised Spring 2003 Reese & Woods.

Title Sub-Title Open Writing it up! The content of the report/essay/article.

How to Organize Findings, Results, Conclusions, Summary Lynn W Zimmerman, PhD.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Home Blog Presentation Ideas How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

Every research endeavor ends up with the communication of its findings. Graduate-level research culminates in a thesis defense , while many academic and scientific disciplines are published in peer-reviewed journals. In a business context, PowerPoint research presentation is the default format for reporting the findings to stakeholders.

Condensing months of work into a few slides can prove to be challenging. It requires particular skills to create and deliver a research presentation that promotes informed decisions and drives long-term projects forward.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Presentation

Key slides for creating a research presentation, tips when delivering a research presentation, how to present sources in a research presentation, recommended templates to create a research presentation.

A research presentation is the communication of research findings, typically delivered to an audience of peers, colleagues, students, or professionals. In the academe, it is meant to showcase the importance of the research paper , state the findings and the analysis of those findings, and seek feedback that could further the research.

The presentation of research becomes even more critical in the business world as the insights derived from it are the basis of strategic decisions of organizations. Information from this type of report can aid companies in maximizing the sales and profit of their business. Major projects such as research and development (R&D) in a new field, the launch of a new product or service, or even corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives will require the presentation of research findings to prove their feasibility.

Market research and technical research are examples of business-type research presentations you will commonly encounter.

In this article, we’ve compiled all the essential tips, including some examples and templates, to get you started with creating and delivering a stellar research presentation tailored specifically for the business context.

Various research suggests that the average attention span of adults during presentations is around 20 minutes, with a notable drop in an engagement at the 10-minute mark . Beyond that, you might see your audience doing other things.

How can you avoid such a mistake? The answer lies in the adage “keep it simple, stupid” or KISS. We don’t mean dumbing down your content but rather presenting it in a way that is easily digestible and accessible to your audience. One way you can do this is by organizing your research presentation using a clear structure.

Here are the slides you should prioritize when creating your research presentation PowerPoint.

1. Title Page

The title page is the first thing your audience will see during your presentation, so put extra effort into it to make an impression. Of course, writing presentation titles and title pages will vary depending on the type of presentation you are to deliver. In the case of a research presentation, you want a formal and academic-sounding one. It should include:

- The full title of the report

- The date of the report

- The name of the researchers or department in charge of the report

- The name of the organization for which the presentation is intended

When writing the title of your research presentation, it should reflect the topic and objective of the report. Focus only on the subject and avoid adding redundant phrases like “A research on” or “A study on.” However, you may use phrases like “Market Analysis” or “Feasibility Study” because they help identify the purpose of the presentation. Doing so also serves a long-term purpose for the filing and later retrieving of the document.

Here’s a sample title page for a hypothetical market research presentation from Gillette .

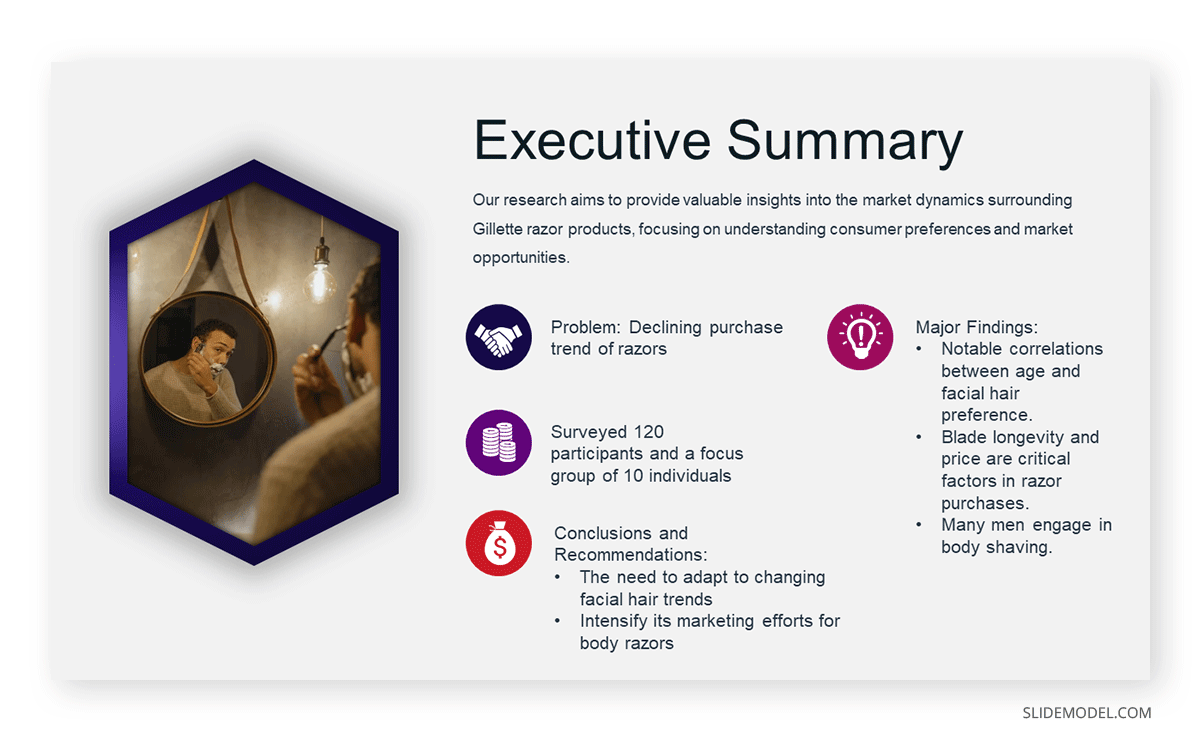

2. Executive Summary Slide

The executive summary marks the beginning of the body of the presentation, briefly summarizing the key discussion points of the research. Specifically, the summary may state the following:

- The purpose of the investigation and its significance within the organization’s goals

- The methods used for the investigation

- The major findings of the investigation

- The conclusions and recommendations after the investigation

Although the executive summary encompasses the entry of the research presentation, it should not dive into all the details of the work on which the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were based. Creating the executive summary requires a focus on clarity and brevity, especially when translating it to a PowerPoint document where space is limited.

Each point should be presented in a clear and visually engaging manner to capture the audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of the presentation. Use visuals, bullet points, and minimal text to convey information efficiently.

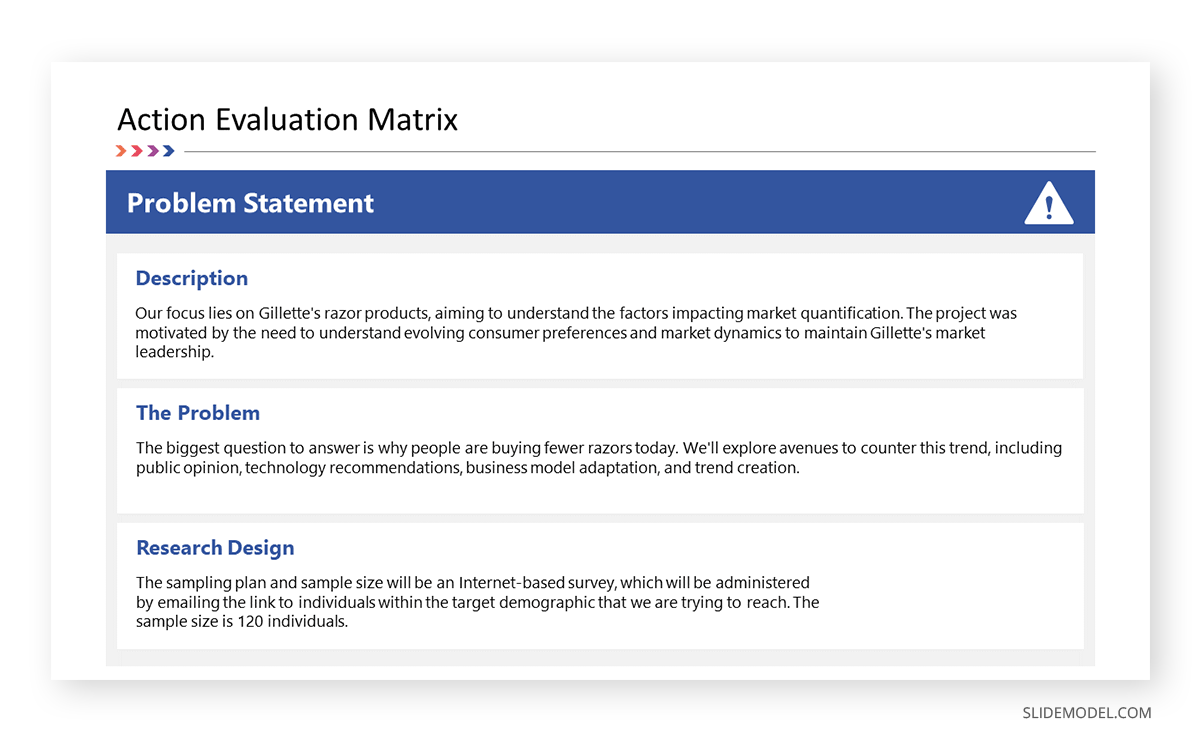

3. Introduction/ Project Description Slides

In this section, your goal is to provide your audience with the information that will help them understand the details of the presentation. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its goals, objectives, scope, and methods for gathering and analyzing data.

You want to answer these fundamental questions:

- What specific questions are you trying to answer, problems you aim to solve, or opportunities you seek to explore?

- Why is this project important, and what prompted it?

- What are the boundaries of your research or initiative?

- How were the data gathered?

Important: The introduction should exclude specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

4. Data Presentation and Analyses Slides

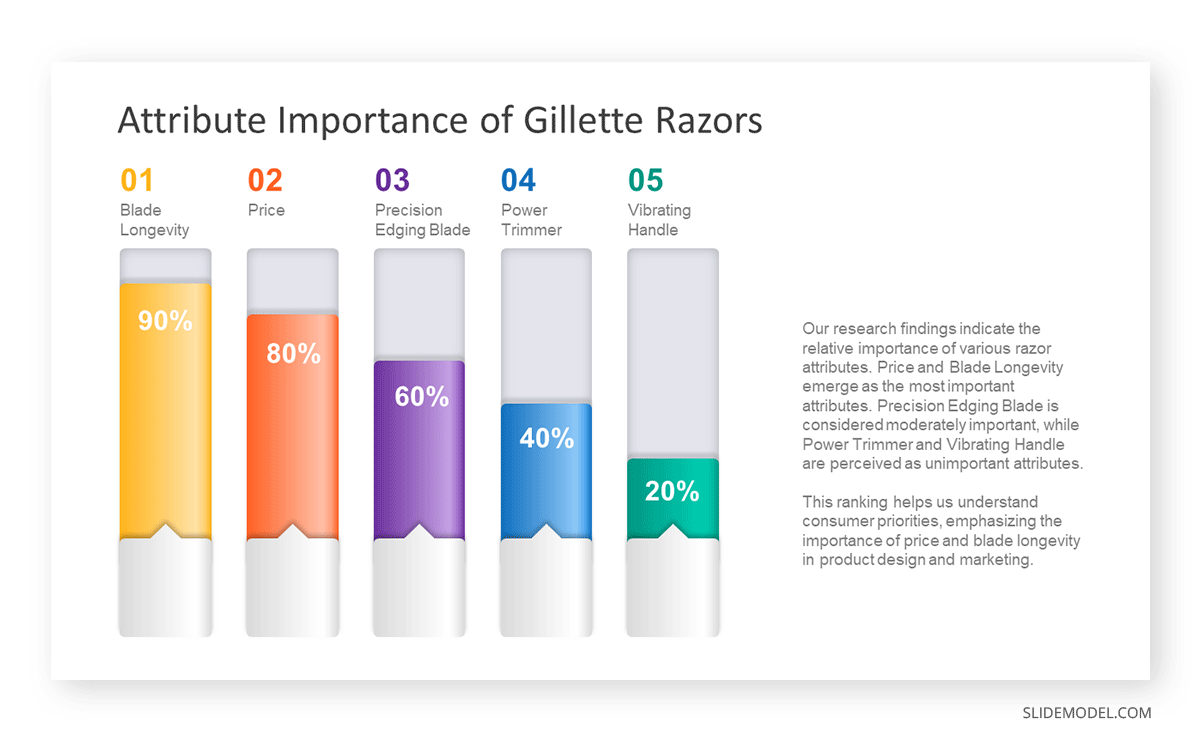

This is the longest section of a research presentation, as you’ll present the data you’ve gathered and provide a thorough analysis of that data to draw meaningful conclusions. The format and components of this section can vary widely, tailored to the specific nature of your research.

For example, if you are doing market research, you may include the market potential estimate, competitor analysis, and pricing analysis. These elements will help your organization determine the actual viability of a market opportunity.

Visual aids like charts, graphs, tables, and diagrams are potent tools to convey your key findings effectively. These materials may be numbered and sequenced (Figure 1, Figure 2, and so forth), accompanied by text to make sense of the insights.

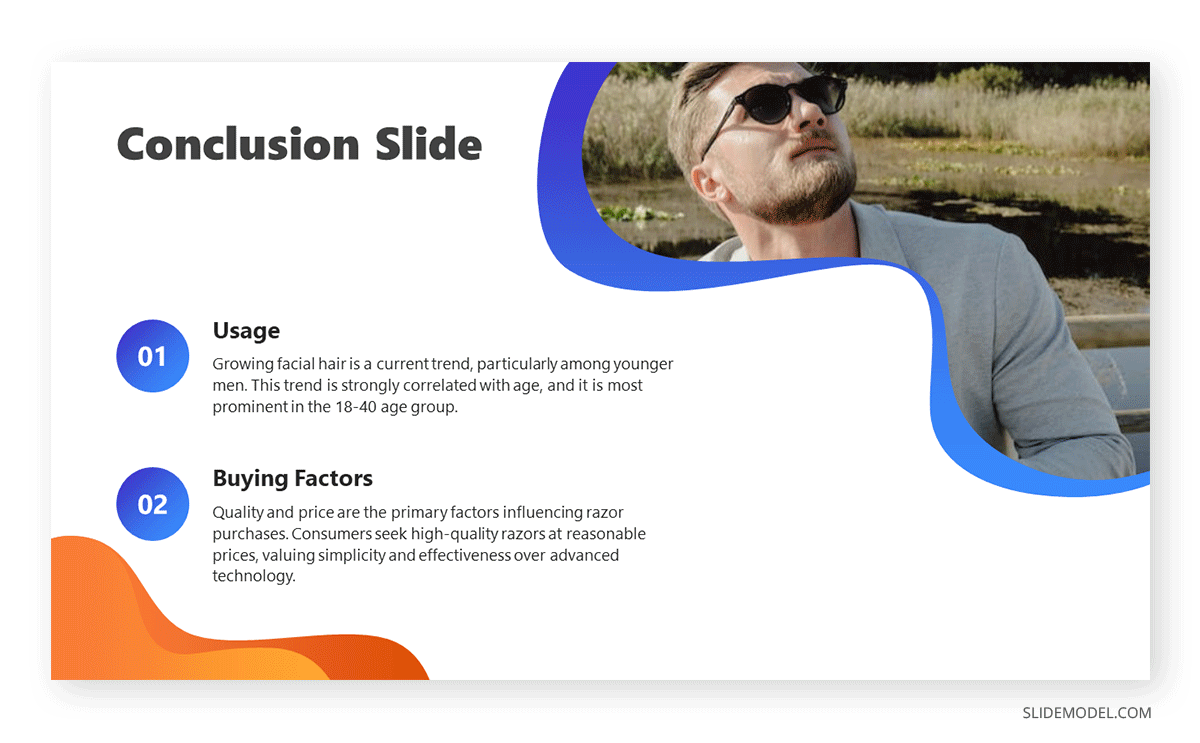

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of a research presentation is where you pull together the ideas derived from your data presentation and analyses in light of the purpose of the research. For example, if the objective is to assess the market of a new product, the conclusion should determine the requirements of the market in question and tell whether there is a product-market fit.

Designing your conclusion slide should be straightforward and focused on conveying the key takeaways from your research. Keep the text concise and to the point. Present it in bullet points or numbered lists to make the content easily scannable.

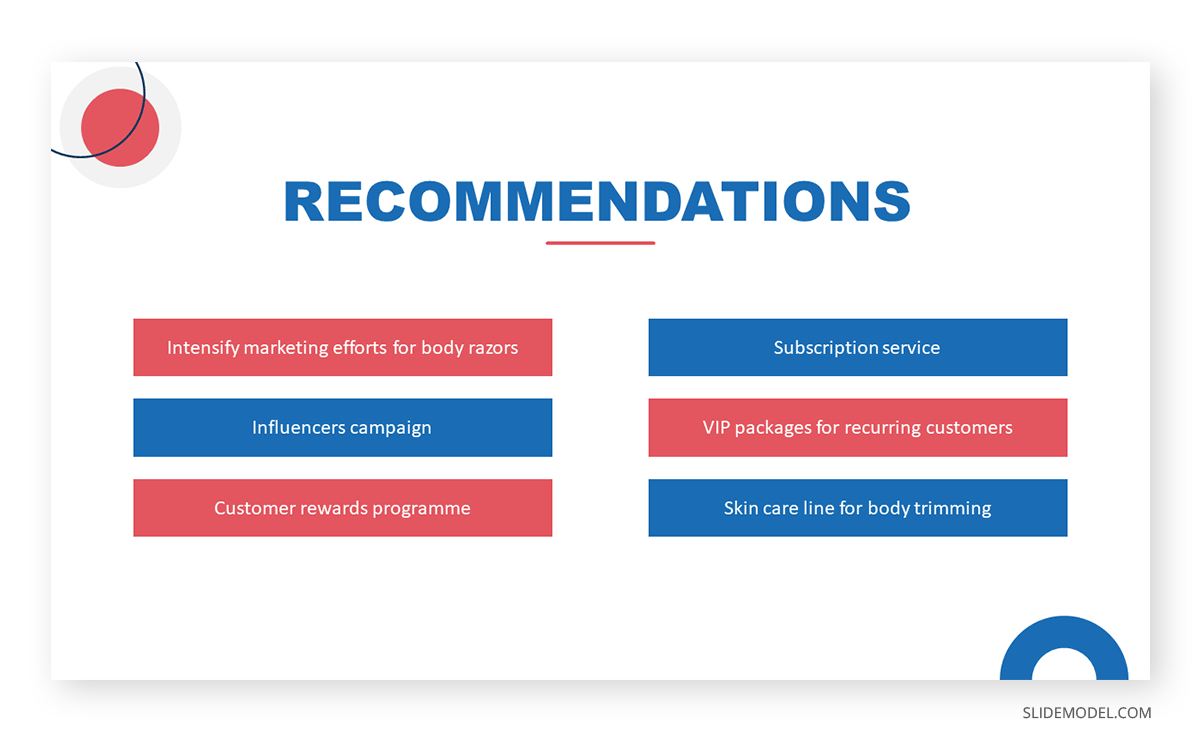

6. Recommendations

The findings of your research might reveal elements that may not align with your initial vision or expectations. These deviations are addressed in the recommendations section of your presentation, which outlines the best course of action based on the result of the research.

What emerging markets should we target next? Do we need to rethink our pricing strategies? Which professionals should we hire for this special project? — these are some of the questions that may arise when coming up with this part of the research.

Recommendations may be combined with the conclusion, but presenting them separately to reinforce their urgency. In the end, the decision-makers in the organization or your clients will make the final call on whether to accept or decline the recommendations.

7. Questions Slide

Members of your audience are not involved in carrying out your research activity, which means there’s a lot they don’t know about its details. By offering an opportunity for questions, you can invite them to bridge that gap, seek clarification, and engage in a dialogue that enhances their understanding.

If your research is more business-oriented, facilitating a question and answer after your presentation becomes imperative as it’s your final appeal to encourage buy-in for your recommendations.

A simple “Ask us anything” slide can indicate that you are ready to accept questions.

If you need a quick method to create a research presentation, check out our AI presentation maker . A tool in which you add the topic, curate the outline, select a design, and let AI do the work for you. Alternatively, check our tutorial on how to convert a research paper to presentation using AI .

1. Focus on the Most Important Findings

The truth about presenting research findings is that your audience doesn’t need to know everything. Instead, they should receive a distilled, clear, and meaningful overview that focuses on the most critical aspects.

You will likely have to squeeze in the oral presentation of your research into a 10 to 20-minute presentation, so you have to make the most out of the time given to you. In the presentation, don’t soak in the less important elements like historical backgrounds. Decision-makers might even ask you to skip these portions and focus on sharing the findings.

2. Do Not Read Word-per-word

Reading word-for-word from your presentation slides intensifies the danger of losing your audience’s interest. Its effect can be detrimental, especially if the purpose of your research presentation is to gain approval from the audience. So, how can you avoid this mistake?

- Make a conscious design decision to keep the text on your slides minimal. Your slides should serve as visual cues to guide your presentation.

- Structure your presentation as a narrative or story. Stories are more engaging and memorable than dry, factual information.

- Prepare speaker notes with the key points of your research. Glance at it when needed.

- Engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and asking rhetorical questions.

3. Don’t Go Without Handouts

Handouts are paper copies of your presentation slides that you distribute to your audience. They typically contain the summary of your key points, but they may also provide supplementary information supporting data presented through tables and graphs.

The purpose of distributing presentation handouts is to easily retain the key points you presented as they become good references in the future. Distributing handouts in advance allows your audience to review the material and come prepared with questions or points for discussion during the presentation. Also, check our article about how to create handouts for a presentation .

4. Actively Listen

An equally important skill that a presenter must possess aside from speaking is the ability to listen. We are not just talking about listening to what the audience is saying but also considering their reactions and nonverbal cues. If you sense disinterest or confusion, you can adapt your approach on the fly to re-engage them.

For example, if some members of your audience are exchanging glances, they may be skeptical of the research findings you are presenting. This is the best time to reassure them of the validity of your data and provide a concise overview of how it came to be. You may also encourage them to seek clarification.

5. Be Confident

Anxiety can strike before a presentation – it’s a common reaction whenever someone has to speak in front of others. If you can’t eliminate your stress, try to manage it.

People hate public speaking not because they simply hate it. Most of the time, it arises from one’s belief in themselves. You don’t have to take our word for it. Take Maslow’s theory that says a threat to one’s self-esteem is a source of distress among an individual.

Now, how can you master this feeling? You’ve spent a lot of time on your research, so there is no question about your topic knowledge. Perhaps you just need to rehearse your research presentation. If you know what you will say and how to say it, you will gain confidence in presenting your work.

All sources you use in creating your research presentation should be given proper credit. The APA Style is the most widely used citation style in formal research.

In-text citation

Add references within the text of your presentation slide by giving the author’s last name, year of publication, and page number (if applicable) in parentheses after direct quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

The alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (Smith, 2020, p. 27).

If the author’s name and year of publication are mentioned in the text, add only the page number in parentheses after the quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

According to Smith (2020), the alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (p. 27).

Image citation

All images from the web, including photos, graphs, and tables, used in your slides should be credited using the format below.

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image.” Website Name, Day Mo. Year, URL. Accessed Day Mo. Year.

Work cited page

A work cited page or reference list should follow after the last slide of your presentation. The list should be alphabetized by the author’s last name and initials followed by the year of publication, the title of the book or article, the place of publication, and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. New York, NY: ABC Publications.

When citing a document from a website, add the source URL after the title of the book or article instead of the place of publication and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. Retrieved from https://www.smith.com/climate-change-and-biodiversity.

1. Research Project Presentation PowerPoint Template

A slide deck containing 18 different slides intended to take off the weight of how to make a research presentation. With tons of visual aids, presenters can reference existing research on similar projects to this one – or link another research presentation example – provide an accurate data analysis, disclose the methodology used, and much more.

Use This Template

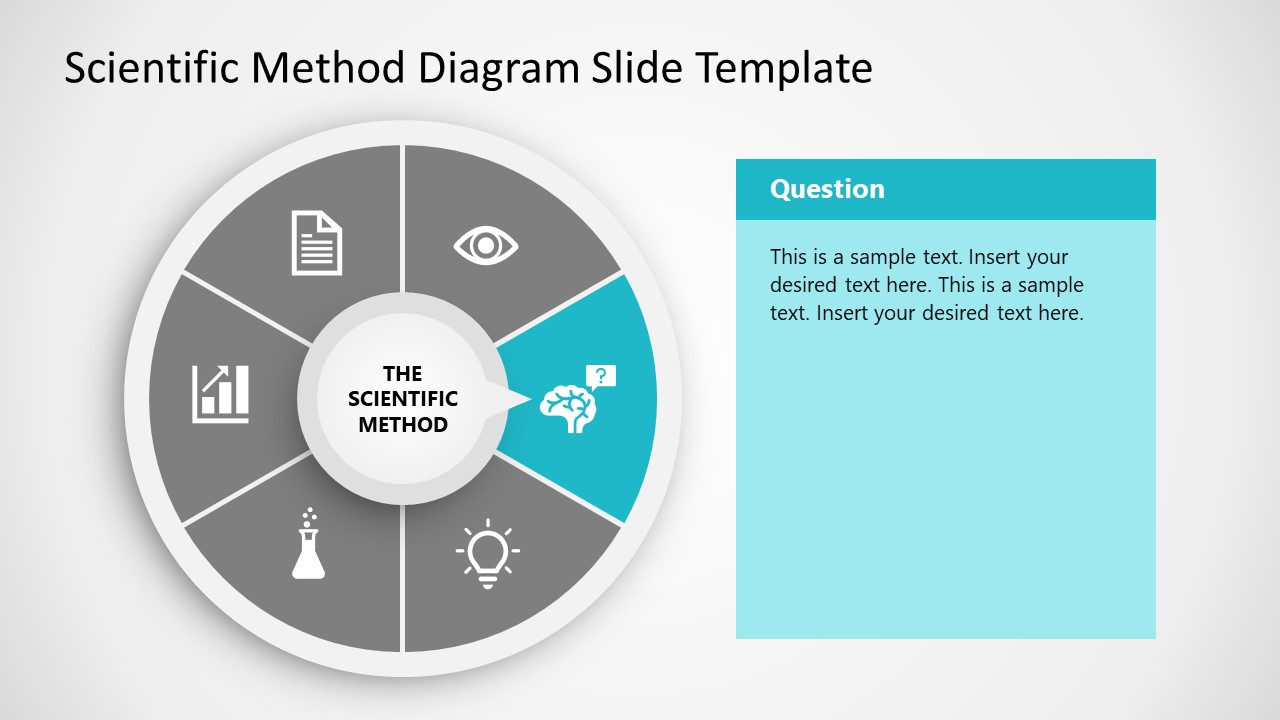

2. Research Presentation Scientific Method Diagram PowerPoint Template

Whenever you intend to raise questions, expose the methodology you used for your research, or even suggest a scientific method approach for future analysis, this circular wheel diagram is a perfect fit for any presentation study.

Customize all of its elements to suit the demands of your presentation in just minutes.

3. Thesis Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

If your research presentation project belongs to academia, then this is the slide deck to pair that presentation. With a formal aesthetic and minimalistic style, this research presentation template focuses only on exposing your information as clearly as possible.

Use its included bar charts and graphs to introduce data, change the background of each slide to suit the topic of your presentation, and customize each of its elements to meet the requirements of your project with ease.

4. Animated Research Cards PowerPoint Template

Visualize ideas and their connection points with the help of this research card template for PowerPoint. This slide deck, for example, can help speakers talk about alternative concepts to what they are currently managing and its possible outcomes, among different other usages this versatile PPT template has. Zoom Animation effects make a smooth transition between cards (or ideas).

5. Research Presentation Slide Deck for PowerPoint

With a distinctive professional style, this research presentation PPT template helps business professionals and academics alike to introduce the findings of their work to team members or investors.

By accessing this template, you get the following slides:

- Introduction

- Problem Statement

- Research Questions

- Conceptual Research Framework (Concepts, Theories, Actors, & Constructs)

- Study design and methods

- Population & Sampling

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

Check it out today and craft a powerful research presentation out of it!

A successful research presentation in business is not just about presenting data; it’s about persuasion to take meaningful action. It’s the bridge that connects your research efforts to the strategic initiatives of your organization. To embark on this journey successfully, planning your presentation thoroughly is paramount, from designing your PowerPoint to the delivery.

Take a look and get inspiration from the sample research presentation slides above, put our tips to heart, and transform your research findings into a compelling call to action.

Like this article? Please share

Academics, Presentation Approaches, Research & Development Filed under Presentation Ideas

Related Articles

Filed under Presentation Ideas • October 23rd, 2024

Formal vs Informal Presentation: Understanding the Differences

Learn the differences between formal and informal presentations and how to transition smoothly. PPT templates and tips here!

Filed under Design • October 17th, 2024

Architecture Project Presentation: Must-Know Secrets for Creative Slides

Impress your audience by mastering the art of architectural project presentations. This detailed guide will give you the insights for this craft.

Filed under Design • October 7th, 2024

Video to PPT Converter AI with SlideModel AI

Looking to generate a presentation from a video transcript? Discover why SlideModel AI is the best tool for the task.

Leave a Reply

Communicating and Disseminating Research Findings

- First Online: 23 September 2017

Cite this chapter

- Amber E. Budden 3 &

- William K. Michener 3

2226 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter provides guidance on approaches and best practices for communicating and disseminating research findings to technical audiences via scholarly publications such as peer-reviewed journal articles, abstracts, technical reports, books and book chapters. We also discuss approaches for communicating findings to more general audiences via newspaper and magazine articles and highlight best practices for designing effective figures that explain and support the research findings that are presented in scientific and general audience publications. Research findings may also be presented verbally to educate, change perceptions and attitudes, or influence policy and resource management. Key topics include simple steps for giving effective presentations and best practices for designing slide text and graphics, posters and handouts. Websites and social media are increasingly important mechanisms for communicating science. We discuss forms of commonly used social media, identify simple steps for effectively using social media, and highlight ways to track and understand your social media and overall research impact using various metrics and altmetrics.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Communicating Scientific Research Through the Web and Social Media: Experience of the United Nations University with the Our World 2.0 Web Magazine

How to Write and Publish an Empirical Report

Alred GJ, Brusaw CT, Oliu WE (2011) Handbook of technical writing, 10th edn. St. Martin’s Press, Bedford

Google Scholar

Altmetric (2016) Altmetric. https://www.altmetric.com . Accessed 18 Aug 2016

Bale R, Neveln ID, Bhalla APS et al (2015) Convergent evolution of mechanically optimal locomotion in aquatic invertebrates and vertebrates. PLoS Biol 13(4):e1002123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002123

Article Google Scholar

Bergou AJ, Swartz SM, Vejdani H et al (2015) Falling with style: bats perform complex aerial rotations by adjusting wing inertia. PLoS Biol 13(11):e1002297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002297

Bornmann L, Mutz R (2015) Growth rates of modern science: a bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. J Assn Inf Sci Technol 66:2215–2222. doi: 10.1002/asi.23329

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bourne PE (2005) Ten simple rules for getting published. PLoS Comput Biol 1(5):e57. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010057

Bourne PE (2007) Ten simple rules for making good oral presentations. PLoS Comput Biol 3(4):e77. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030077

Brody T, Harnad S, Carr L (2006) Earlier web usage statistics as predictors of later citation impact. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 57:1060–1072. doi: 10.1002/asi.20373

Chaves ÓM, Bicca-Marques JC (2016) Feeding strategies of brown howler monkeys in response to variations in food availability. PLoS One 11(2):e0145819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145819

Cho M (2013) The science behind fonts (and how they make you feel). http://thenextweb.com/dd/2013/12/23/science-behind-fonts-make-feel/ . Accessed 1 Aug 2016

Cleveland WS, McGill R (1985) Graphical perception and graphical methods for analyzing scientific data. Science 229(4716):828–833

Cook RB, Wie Y, Hook LA et al (2017) Preserve: protecting data for long-term use, Chapter 6. In: Recknagel F, Michener W (eds) Ecological informatics. Data management and knowledge discovery. Springer, Heidelberg

Cornell University (2016) The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. http://www.birds.cornell.edu/ . Accessed 18 Aug 2016

Croxall B (2014) Ten tips for tweeting at conferences. http://chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/ten-tips-for-tweeting-at-conferences/54281 . Accessed 15 June 2016

CTAN (2016) CTAN: Package tufte-latex. http://www.ctan.org/pkg/tufte-latex . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

DataONE (2016) DataONE. https://www.facebook.com/DataONEorg/ . Accessed 25 Nov 2016

Duarte N (2008) slide:ology: the art and science of creating great presentations. O’Reilly Media, Sebastopol, CA

Duarte N (2010) Resonate: present visual stories that transform audiences. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ

Duckett J (2011) HTML and CSS: design and build websites, 1st edn. Wiley, Indianapolis

Ekins S, Perlstein EO (2014) Ten simple rules of live tweeting at scientific conferences. PLoS Comput Biol 10(8):e1003789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003789

Erren TC, Bourne PE (2007) Ten simple rules for a good poster presentation. PLoS Comput Biol 3(5):e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030102

Eysenbach G (2011) Can tweets predict citations? Metrics of social impact based on Twitter and correlation with traditional metrics of scientific impact. J Med Internet Res 13(4):e123

Faulkes Z (2016) Better posters. http://betterposters.blogspot.com/ . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

Few S (2009) Now you see it: simple visualization techniques for quantitative analysis. Analytics Press, Oakland, CA

Few S (2012) Show me the numbers: designing tables and graphs to enlighten, 2nd edn. Analytics Press, Burlingame, CA

Few S (2016) Perceptual edge – examples. http://www.perceptualedge.com/examples.php . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

Forant T (2013) 10 social media best practices for brand engagement. https://www.marketingcloud.com/blog/social-media-best-practices-for-brand-engagement/ . Accessed 16 May 2016

GLEON (2016) GLEON: global lake ecological observatory network. http://gleon.org . Accessed 18 Aug 2016

Hampton SE, Anderson SS, Bagby SC et al (2015) The Tao of open science for ecology. Ecosphere 6(7):1–13. doi: 10.1890/ES14-00402.1

Hines K (2015) All of the social media metrics that matter. http://sproutsocial.com/insights/social-media-metrics-that-matter/ . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

Hirsch JE (2005) An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:16569–16572

Impactstory (2016) Impactstory. https://impactstory.org . Accessed 18 Aug 2016

Klout Inc. (2015) Klout. https://klout.com . Accessed 10 Aug 2016

Kronick DA (1976) A history of scientific & technical periodicals: the origins and development of the scientific and technical press, 1665-1790. Scarecrow Press, Metuchen, NJ

Krug S (2014) Don’t make me think, revisited: a common sense approach to web usability, 3rd edn. New Riders, San Francisco

Leek J (2016) How to be a modern scientist. Lean Publishing, Victoria, BC

Lin J, Fenner M (2013) Altmetrics in evolution: defining and redefining the ontology of article-level metrics. Inf Stand Q 25:20–26

Lister AL, Datta RS, Hofmann O et al (2010) Live coverage of scientific conferences using web technologies. PLoS Comput Biol 6(1). doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000563

LTER (2016) The long term ecological research network. http://www.lternet.edu . Accessed 18 Aug 2016

Malson G (2015) Preparing a research poster for a conference. Clin Pharm 7(3). doi: 10.1211/CP.2015.20068193

Michener WK (2017) Data discovery, Chapter 7. In: Recknagel F, Michener W (eds) Ecological informatics. Data management and knowledge discovery. Springer, Heidelberg

NEON (2016) National Ecological Observatory Network. https://www.facebook.com/NEONScienceData/ . Accessed 25 Nov 2016

NSF (2016) National Science Foundation. https://www.facebook.com/US.NSF/ . Accessed 25 Nov 2016

NutNet (2016) Nutrient network: a global research cooperative. http://www.nutnet.umn.edu . Accessed 18 Aug 2016

Piwowar H (2013) Altmetrics: value all research products. Nature 493:159. doi: 10.1038/493159a

CAS Google Scholar

Piwowar H, Priem J (2013) The power of altmetrics on a CV. Bull Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 39:10–13

Plunkett S (2016) Tips on poster presentations at professional conference. http://www.csun.edu/plunk/documents/poster_presentation.pdf . Accessed 1 Jun 2016

Priem J, Piwowar HA, Hemminger BM (2012) Altmetrics in the wild: using social media to explore scholarly impact. ArXiv.org . http://arxiv.org/abs/1203.4745 . Accessed 5 Feb 2016

Purrington CB (2016) Designing conference posters. http://colinpurrington.com/tips/poster-design . Accessed 24 May 2016

R Markdown (2016) Tufte handouts. http://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/tufte_handout_format.html . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

Robbins JN (2012) Learning web design: a beginner’s guide to HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and web graphics, 4th edn. O’Reilly Media, Sebastopol, CA

Robbins NB (2013) Creating more effective graphs. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ

Robbins NB (2016) http://www.nbr-graphs.com/examples/ . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

Rose PM, Kennard MJ, Moffatt DB et al (2016) Testing three species distribution modelling strategies to define fish assemblage reference conditions for stream bioassessment and related applications. PLoS One 11(1):e0146728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146728

Rougier NP, Droettboom M, Bourne PE (2014) Ten simple rules for better figures. PLoS Comput Biol 10(9):e1003833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003833

Statista (2016) Leading social networks worldwide as of April 2016, ranked by number of active users (in millions). http://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ . Accessed 05 May 2016

Strunk W Jr, White EB (1999) The elements of style, 4th edn. Longman, New York

Sullivan C (2011) Strata 2011 [day 1]: communicating data clearly. http://infosthetics.com/archives/2011/02/strata_2011_communicating_data_clearly.html Accessed 10 Aug 2016

Thelwall M, Haustein S, Larivière V et al (2013) Do altmetrics work? Twitter and ten other social web services. PLoS ONE 8(5):e64841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064841

Tufte EG (1983) The visual display of quantitative information. Graphics Press, Cheshire, CT

Tufte ER (1990) Envisioning information. Graphics Press, Cheshire, CT

Tufte ER (1997) Visual explanations: images and quantities, evidence and narrative. Graphics Press, Cheshire, CT

Tufte ER (2003) The cognitive style of Powerpoint. Graphics Press, Cheshire, CT

Tufte ER (2006) Beautiful evidence. Graphics Press, Cheshire, CT

Tufte E (2016) The work of Edward Tufte and Graphics Press. https://www.edwardtufte.com/tufte/ . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

University of Chicago Press Staff (2010) The Chicago manual of style, 16th edn. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Weinberger CJ, Evans JA, Allesina S (2015) Ten simple (empirical) rules for writing science. PLoS Comput Biol 11(4):e1004205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004205

Widrich L (2013) 5 essential social media metrics to track and how to improve them. https://blog.bufferapp.com/social-media-metrics-improve . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

Witt C (2016) Effective handouts. http://wittcom.com/effective-handouts/ . Accessed 26 Jul 2016

Wong DM (2013) The Wall Street Journal guide to information graphics: the dos and don'ts of presenting data, facts, and figures. Norton, New York

Zhang W (2014) Ten simple rules for writing research papers. PLoS Comput Biol 10(1):e1003453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003453

Zinsser W (2006) On writing well: the classic guide to writing nonfiction, 30th edn. Harper Perennial, New York

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Amber E. Budden & William K. Michener

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amber E. Budden .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Friedrich Recknagel

College of University Libraries, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA

William K. Michener

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Budden, A.E., Michener, W.K. (2018). Communicating and Disseminating Research Findings. In: Recknagel, F., Michener, W. (eds) Ecological Informatics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59928-1_14

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59928-1_14

Published : 23 September 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-59926-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-59928-1

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Communicating and disseminating research findings to study participants: Formative assessment of participant and researcher expectations and preferences

Cathy l melvin, jillian harvey, tara pittman, stephanie gentilin, dana burshell, teresa kelechi.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: C. L. Melvin, MPH, PhD, Department Public Health Sciences, 68 President Street, College of Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, 29425, USA. Email: [email protected]

Received 2019 May 23; Revised 2020 Jan 8; Accepted 2020 Jan 14; Collection date 2020 Jun.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction:

Translating research findings into practice requires understanding how to meet communication and dissemination needs and preferences of intended audiences including past research participants (PSPs) who want, but seldom receive, information on research findings during or after participating in research studies. Most researchers want to let others, including PSP, know about their findings but lack knowledge about how to effectively communicate findings to a lay audience.

We designed a two-phase, mixed methods pilot study to understand experiences, expectations, concerns, preferences, and capacities of researchers and PSP in two age groups (adolescents/young adults (AYA) or older adults) and to test communication prototypes for sharing, receiving, and using information on research study findings.

Principal Results:

PSP and researchers agreed that sharing study findings should happen and that doing so could improve participant recruitment and enrollment, use of research findings to improve health and health-care delivery, and build community support for research. Some differences and similarities in communication preferences and message format were identified between PSP groups, reinforcing the best practice of customizing communication channel and messaging. Researchers wanted specific training and/or time and resources to help them prepare messages in formats to meet PSP needs and preferences but were unaware of resources to help them do so.

Conclusions:

Our findings offer insight into how to engage both PSP and researchers in the design and use of strategies to share research findings and highlight the need to develop services and support for researchers as they aim to bridge this translational barrier.

Keywords: Communication, dissemination, research findings, research participant preference, researcher preference

Introduction

Since 2006, the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) have aimed to advance science and translate knowledge into evidence that, if implemented, helps patients and providers make more informed decisions with the potential to improve health care and health outcomes [ 1 , 2 ]. This aim responded to calls by leaders in the fields of comparative effectiveness research, clinical trials, research ethics, and community engagement to assure that results of clinical trials were made available to participants and suggesting that providing participants with results both positive and negative should be the “ethical norm” [ 1 , 3 ]. Others noted that

on the surface, the concept of providing clinical trial results might seem straightforward but putting such a plan into action will be much more complicated. Communication with patients following participation in a clinical trial represents an important and often overlooked aspect of the patient-physician relationship. Careful exploration of this issue, both from the patient and clinician-researcher perspective, is warranted [ 4 ].

Authors also noted that no systematic approach to operationalizing this “ethical norm” existed and that evidence was lacking to describe either positive or negative outcomes of sharing clinical trial results with study participants and the community [ 4 ]. It was generally assumed, but not supported by research, that sharing would result in better patient–physician/researcher communication, improvement in patient care and satisfaction with care, better patient/participant understanding of clinical trials, and enhanced clinical trial accrual [ 4 ].

More recent literature informs these processes but also raises unresolved concerns about the communication and dissemination of research results. A 2008 narrative review of available data on the effects of communicating aggregate and individual research showed that

research participants want aggregate and clinically significant individual study results made available to them despite the transient distress that communication of results sometimes elicits [ 3 , 5 ]. While differing in their preferences for specific channels of communication, they indicated that not sharing results fostered lack of participant trust in the health-care system, providers, and researchers [ 6 ] and an adverse impact on trial participation [ 5 ];

investigators recognized their ethical obligation to at least offer to share research findings with recipients and the nonacademic community but differed on whether they should proactively re-contact participants, the type of results to be offered to participants, the need for clinical relevance before disclosure, and the stage at which research results should be offered [ 5 ]. They also reported not being well versed in communication and dissemination strategies known to be effective and not having funding sources to implement proven strategies for sharing with specific audiences [ 5 ];

members of the research enterprise noted that while public opinion regarding participation in clinical trials is positive, clinical trial accrual remains low and that the failure to provide information about study results may be one of many factors negatively affecting accrual. They also called for better understanding of physician–researcher and patient attitudes and preferences and posit that development of effective mechanisms to share trial results with study participants should enhance patient–physician communication and improve clinical care and research processes [ 5 ].

A 2010 survey of CTSAs found that while professional and scientific audiences are currently the primary focus for communicating and disseminating research findings, it is equally vital to develop approaches for sharing research findings with other audiences, including individuals who participate in clinical trials [ 1 , 5 ]. Effective communication and dissemination strategies are documented in the literature [ 6 , 7 ], but most are designed to promote adoption of evidence-based interventions and lack of applicability to participants overall, especially to participants who are members of special populations and underrepresented minorities who have fewer opportunities to participate in research and whose preferences for receiving research findings are unknown [ 7 ].

Researchers often have limited exposure to methods that offer them guidance in communicating and disseminating study findings in ways likely to improve awareness, adoption, and use of their findings [ 7 ]. Researchers also lack expertise in using communication channels such as traditional journalism platforms, live or face-to-face events such as public festivals, lectures, and panels, and online interactions [ 8 ]. Few strategies provide guidance for researchers about how to develop communications that are patient-centered, contain plain language, create awareness of the influence of findings on participant or population health, and increase the likelihood of enrollment in future studies.

Consequently, researchers often rely on traditional methods (e.g., presentations at scientific meetings and publication of study findings in peer-reviewed journals) despite evidence suggesting their limited reach and/or impact among professional/scientific and/or lay audiences [ 9 , 10 ].

Input from stakeholders can enhance our understanding of how to assure that participants will receive understandable, useful information about research findings and, as appropriate, interpret and use this information to inform their decisions about changing health behaviors, interacting with their health-care providers, enrolling in future research studies, sharing their study experiences with others, or recommending to others that they participate in studies.

Purpose and Goal

This pilot project was undertaken to address issues cited above and in response to expressed concerns of community members in our area about not receiving information on research studies in which they participated. The project design, a two-phase, mixed methods pilot study, was informed by their subsequent participation in a committee of community-academic representatives to determine possible options for improving the communication and dissemination of study results to both study participants and the community at large.

Our goals were to understand the experiences, expectations, concerns, preferences, and capacities of researchers and past research participants (PSP) in two age groups (adolescents/young adults (AYA) aged 15–25 years and older adults aged 50 years or older) and to test communication prototypes for sharing, receiving, and using information on research study findings. Our long-term objectives are to stimulate new, interdisciplinary collaborative research and to develop resources to meet PSP and researcher needs.

This study was conducted in an academic medical center located in south-eastern South Carolina. Phase one consisted of surveying PSP and researchers. In phase two, in-person focus groups were conducted among PSP completing the survey and one-on-one interviews were conducted among researchers. Participants in either the interviews or focus groups responded to a set of questions from a discussion guide developed by the study team and reviewed three prototypes for communicating and disseminating study results developed by the study team in response to PSP and researcher survey responses: a study results letter, a study results email, and a web-based communication – Mail Chimp (Figs. 1 – 3 ).

Prototype 1: study results email prototype. MUSC, Medical University of South Carolina.

Prototype 3: study results MailChimp prototypes 1 and 2. MUSC, Medical University of South Carolina.

Prototype 2: study results letter prototype.

PSP and researcher surveys

A 42-item survey questionnaire representing seven domains was developed by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, researchers, and PSP that evaluated the questions for content, ease of understanding, usefulness, and comprehensiveness [ 11 ]. Project principal investigators reviewed questions for content and clarity [ 11 ]. The PSP and researcher surveys contained screening and demographic questions to determine participant eligibility and participant characteristics. The PSP survey assessed prior experience with research, receipt of study information from the research team, intention to participate in future research, and preferences and opinions about receipt of information about study findings and next steps. Specific questions for PSP elicited their preferences for communication channels such as phone call, email, social or mass media, and public forum and included channels unique to South Carolina, such as billboards. PSP were asked to rank their preferences and experiences regarding receipt of study results using a Likert scale with the following measurements: “not at all interested” (0), “not very interested” (1), “neutral” (3), “somewhat interested” (3), and “very interested” (4).

The researcher survey contained questions about researcher decisions, plans, and actions regarding communication and dissemination of research results for a recently completed study. Items included knowledge and opinions about how to communicate and disseminate research findings, resources used and needed to develop communication strategies, and awareness and use of dissemination channels, message development, and presentation format.

A research team member administered the survey to PSP and researchers either in person or via phone. Researchers could also complete the survey online through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap©).

Focus groups and discussion guide content

The PSP focus group discussion guide contained questions to assess participants’ past experiences with receiving information about research findings; identify participant preferences for receiving research findings whether negative, positive, or equivocal; gather information to improve communication of research results back to participants; assess participant intention to enroll in future research studies, to share their study experiences with others, and to refer others to our institution for study participation; and provide comments and suggestions on prototypes developed for communication and dissemination of study results. Five AYA participated in one focus group, and 11 older adults participated in one focus group. Focus groups were conducted in an off-campus location with convenient parking and at times convenient for participants. Snacks and beverages were provided.

The researcher interview guide was designed to understand researchers’ perspectives on communicating and disseminating research findings to participants; explore past experiences, if any, of researchers with communication and dissemination of research findings to study participants; document any approaches researchers may have used or intend to use to communicate and disseminate research findings to study participants; assess researcher expectations of benefits associated with sharing findings with participants, as well as, perceived and actual barriers to sharing findings; and provide comments and suggestions on prototypes developed for communication and dissemination of study results.

Prototype materials

Three prototypes were presented to focus group participants and included (1) a formal letter on hospital letterhead designed to be delivered by standard mail, describing the purpose and findings of a fictional study and thanking the individual for his/her participation, (2) a text-only email including a brief thank you and a summary of major findings with a link to a study website for more information, and (3) an email formatted like a newsletter with detailed information on study purpose, method, and findings with graphics to help convey results. A mock study website was shown and included information about study background, purpose, methods, results, as well as, links to other research and health resources. Prototypes were presented either in paper or PowerPoint format during the focus groups and explained by a study team member who then elicited participant input using the focus group guide. Researchers also reviewed and commented on prototype content and format in one-on-one interviews with a study team member.

Protection of Human Subjects

The study protocol (No. Pro00067659) was submitted to and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina in 2017. PSP (or the caretakers for PSP under age 18), and researchers provided verbal informed consent prior to completing the survey or participating in either a focus group or interview. Participants received a verbal introduction prior to participating in each phase.

Recruitment and Interview Procedures

Past study participants.

A study team member reviewed study participant logs from five recently completed studies at our institution involving AYA or older adults to identify individuals who provided consent for contact regarding future studies. Subsequent PSP recruitment efforts based on these searches were consistent with previous contact preferences recorded in each study participant’s consent indicating desire to be re-contacted. The primary modes of contact were phone/SMS and email.

Efforts to recruit other PSP were made through placement of flyers in frequented public locations such as coffee shops, recreation complexes, and college campuses and through social media, Yammer, and newsletters. ResearchMatch, a web-based recruitment tool, was used to alert its subscribers about the study. Potential participants reached by these methods contacted our study team to learn more about the study, and if interested and pre-screened eligible, volunteered and were consented for the study. PSP completing the survey indicated willingness to share experiences with the study team in a focus group and were re-contacted to participate in focus groups.

Researcher recruitment

Researchers were identified through informal outreach by study investigators and staff, a flyer distributed on campus, use of Yammer and other institutional social media platforms, and internal electronic newsletters. Researchers responding to these recruitment efforts were invited to participate in the researcher survey and/or interview.

Incentives for participation

Researchers and PSP received a $25 gift card for completing the survey and $75 for completing the interview (researcher) or focus group (PSP) (up to $100 per researcher or PSP).

Data tables displaying demographic and other data from the PSP surveys (Table 1 ) were prepared from the REDCap© database and responses reported as number and percent of respondents choosing each response option.

Post study participant (PSP) characteristics by Adolescents/Young Adults (AYA), Older Adults, and ALL (All participants regardless of age)

Age mean (SD) = 49.7 (18.6).

Focus group and researcher interview data were recorded (either via audio recording and/or notes taken by research staff) and analyzed via a general inductive qualitative approach, a method appropriate for program evaluation studies and aimed at condensing large amounts of textual data into frameworks that describe the underlying process and experiences under study [ 12 ]. Data were analyzed by our team’s qualitative expert who read the textual data multiple times, developed a coding scheme to identify themes in the textual data, and used group consensus methods with other team members to identify unique, key themes.

Sixty-one of sixty-five PSP who volunteered to participate in the PSP survey were screened eligible, fifty were consented, and forty-eight completed the survey questionnaire. Of the 48 PSP completing the survey, 15 (32%) were AYA and 33 (68%) older adults. The mean age of survey respondents was 49.7 years, 23.5 for AYA, and 61.6 for older adults. Survey respondents were predominantly White, non-Hispanic/Latino, female, and with some college or a college degree (Table 1 ). The percentage of participants in each group never or rarely needing any help with reading/interpreting written materials was above 93% in both groups.

Over 90% of PSP responded that they would participate in another research study, and more than 75% of PSP indicated that study participants should know about study results. Most (68.8%) respondents indicated that they did not receive any communications from study staff after they finished a study .

PSP preferences for communication channel are summarized in Table 2 and based on responses to the question “How do you want to receive information?.” Both AYA and older adults agree or completely agree that they prefer email to other communication channels and that billboards did not apply to them. Older adult preferences for communication channels as indicated by agreeing or completely agreeing were in ranked order of highest to lowest: use of mailed letters/postcards, newsletter, and phone. A majority (over 50%) of older adults completely disagreed or disagreed on texting and social media as options and had only slight preference for mass media, public forum, and wellness fairs or expos.

Communication preference by group: AYA * , older adult ** , and ALL ( n = 48)

ALL, total per column.

AYA: adolescent/young adult (age 15–24.99 years) ( n = 15).

Older adult (age 50 years or more) ( n = 33).

While AYA preferred email over all other options, they completely disagreed/disagreed with mailed letters/postcards, social media, and mass media options.

When communication formats were ranked overall by each group and by both groups combined, the ranking from most to least preferred was written materials, opportunities to interact with study teams and ask questions, visual charts, graphs, pictures, and videos, audios, and podcasts.

PSP Focus Groups

PSP want to receive and share information on study findings for studies in which he/she participated. Furthermore, participants stated their desire to share study results across social networks and highlighted opportunities to share communicated study results with their health-care providers, family members, friends, and other acquaintances with similar medical conditions.

Because of the things I was in a study for, it’s a condition I knew three other people who had the same condition, so as soon as it worked for me, I put the word out, this is great stuff. I would forward the email with the link, this is where you can go to also get in on this study, or I’d also tell them, you know, for me, like the medication. Here’s the medication. Here’s the name of it. Tell your doctor. I would definitely share. I’d just tell everyone without a doubt. Right when I get home, as soon as I walk in the door, and say Renee-that’s my daughter-I’ve got to tell you this.

Communication of study information could happen through several channels including social media, verbal communication, sharing of written documents, and forwarding emails containing a range of content in a range of formats (e.g., reports and pamphlets).

Word of mouth and I have no shame in saying I had head to toe psoriasis, and I used the drug being studied, and so I would just go to people, hey, look. So, if you had it in paper form, like a pamphlet or something, yeah I’d pass it on to them.

PSP prefer clear, simple messaging and highlighted multiple, preferred communication modalities for receiving information on study findings including emails, letters, newsletters, social media, and websites.

The wording is really simple, which I like. It’s to the point and clear. I really like the bullet points, because it’s quick and to the point. I think the [long] paragraphs-you get lost, especially when you are reading on your phone.

They indicated a clear preference for colorful, simple, easy to read communication. PSP also expressed some concern about difficulty opening emails with pictures and dislike lengthy written text. “I don’t read long emails. I tend to delete them”

PSP indicated some confusion about common research language. For example, one participant indicated that using the word “estimate” indicates the research findings were an approximation, “When I hear those words, I just think you’re guessing, estimate, you know? It sounds like an estimate, not a definite answer.”

Researcher Survey

Twenty-three of thirty-two researchers volunteered to participate in the researcher survey, were screened eligible, and two declined to participate, resulting in 19 who provided consent to participate and completed the survey. The mean age of survey respondents was 51.8 years. Respondents were predominantly White, non-Hispanic/Latino, and female, and all were holders of either a professional school degree or a doctoral degree. When asked if it is important to inform study participants of study results, 94.8% of responding researchers agreed that it was extremely important or important. Most researchers have disseminated findings to study participants or plan to disseminate findings.

Researchers listed a variety of reasons for their rating of the importance of informing study participants of study results including “to promote feelings of inclusion by participants and other community members”, “maintaining participant interest and engagement in the subject study and in research generally”, “allowing participants to benefit somewhat from their participation in research and especially if personal health data are collected”, “increasing transparency and opportunities for learning”, and “helping in understanding the impact of the research on the health issue under study”.

Some researchers view sharing study findings as an “ethical responsibility and/or a tenet of volunteerism for a research study”. For example, “if we (researchers) are obligated to inform participants about anything that comes up during the conduct of the study, we should feel compelled to equally give the results at the end of the study”.

One researcher “thought it a good idea to ask participants if they would like an overview of findings at the end of the study that they could share with others who would like to see the information”.

Two researchers said that sharing research results “depends on the study” and that providing “general findings to the participants” might be “sufficient for a treatment outcome study”.

Researchers indicated that despite their willingness to share study results, they face resource challenges such as a lack of funding and/or staff to support communication and dissemination activities and need assistance in developing these materials. One researcher remarked “I would really like to learn what are (sic) the best ways to share research findings. I am truly ignorant about this other than what I have casually observed. I would enjoy attending a workshop on the topic with suggested templates and communication strategies that work best” and that this survey “reminds me how important this is and it is promising that our CTSA seems to plan to take this on and help researchers with this important study element.”

Another researcher commented on a list of potential types of assistance that could be made available to assist with communicating and disseminating results, that “Training on developing lay friendly messaging is especially critically important and would translate across so many different aspects of what we do, not just dissemination of findings. But I’ve noticed that it is a skill that very few people have, and some people never can seem to develop. For that reason, I find as a principal investigator that I am spending a lot of my time working on these types of materials when I’d really prefer research assistant level folks having the ability to get me 99% of the way there.”

Most researchers indicated that they provide participants with personal tests or assessments taken from the study (60% n = 6) and final study results (72.7%, n = 8) but no other information such as recruitment and retention updates, interim updates or results, information on the impact of the study on either the health topic of the study or the community, information on other studies or provide tips and resources related to the health topic and self-help. Sixty percent ( n = 6) of researcher respondents indicated sharing planned next steps for the study team and information on how the study results would be used.

When asked about how they communicated results, phone calls were mentioned most frequently followed by newsletters, email, webpages, public forums, journal article, mailed letter or postcard, mass media, wellness fairs/expos, texting, or social media.

Researchers used a variety of communication formats to communicate with study participants. Written descriptions of study findings were most frequently reported followed by visual depictions, opportunities to interact with study staff and ask questions or provide feedback, and videos/audio/podcasts.

Seventy-three percent of researchers reported that they made efforts to make study findings information available to those with low levels of literacy, health literacy, or other possible limitations such as non-English-speaking populations.

In open-ended responses, most researchers reported wanting to increase their awareness and use of on-campus training and other resources to support communication and dissemination of study results, including how to get resources and budgets to support their use.

Researcher Interviews

One-on-one interviews with researchers identified two themes.

Researchers may struggle to see the utility of communicating small findings

Some researchers indicated hesitancy in communicating preliminary findings, findings from small studies, or highly summarized information. In addition, in comparison to research participants, researchers seemed to place a higher value on specific details of the study.

“I probably wouldn’t put it up [on social media] until the actual manuscript was out with the graphs and the figures, because I think that’s what people ultimately would be interested in.”

Researchers face resource and time limitations in communication and dissemination of study findings

Researchers expressed interest in communicating research results to study participants. However, they highlighted several challenges including difficulties in tracking current email and physical addresses for participants; compliance with literacy and visual impairment regulations; and the number of products already required in research that consume a considerable amount of a research team’s time. Researchers expressed a desire to have additional resources and templates to facilitate sharing study findings. According to one respondent, “For every grant there is (sic) 4-10 papers and 3-5 presentations, already doing 10-20 products.” Researchers do not want to “reinvent the wheel” and would like to pull from existing papers and presentations on how to share with participants and have boilerplate, writing templates, and other logistical information available for their use.

Researchers would also like training in the form of lunch-n-learns, podcasts, or easily accessible online tools on how to develop materials and approaches. Researchers are interested in understanding the “do’s and don’ts” of communicating and disseminating study findings and any regulatory requirements that should be considered when communicating with research participants following a completed study. For example, one researcher asked, “From beginning to end – the do’s and don’ts – are stamps allowed as a direct cost? or can indirect costs include paper for printing newsletters, how about designing a website, a checklist for pulling together a newsletter?”

The purpose of this pilot study was to explore the current experiences, expectations, concerns, preferences, and capacities of PSP including youth/young adult and older adult populations and researchers for sharing, receiving, and using information on research study findings. PSP and researchers agreed, as shown in earlier work [ 3 , 5 ], that sharing information upon study completion with participants was something that should be done and that had value for both PSP and researchers. As in prior studies [ 3 , 5 ], both groups also agreed that sharing study findings could improve ancillary outcomes such as participant recruitment and enrollment, use of research findings to improve health and health-care delivery, and build overall community support for research. In addition, communicating results acknowledges study participants’ contributions to research, a principle firmly rooted in respect for treating participants as not merely a means to further scientific investigation [ 5 ].