What Is Systems Thinking in Education? Understanding Functions and Interactions in School Systems

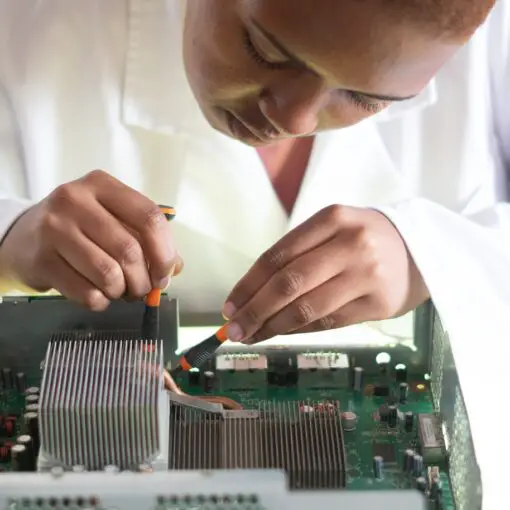

Schools, districts, and classrooms are dynamic environments, full of energy and talent. Managing them calls for creative leadership and teaching approaches. Leaders in education need to anticipate how interconnected aspects of schools interact and affect each other.

Systems thinking in education offers a valuable approach for teachers working to build student engagement. The approach also helps leaders organize schools by harnessing their assets. American University’s EdD in Education Policy and Leadership trains educators to apply systems thinking and other effective leadership approaches to transforming schools for the better.

The Systems Thinking Model

An education system is composed of many interdependent components working together. How well these components operate and interact determines the system’s health.

Education systems at the national, state, and local levels consist of interacting parts, including:

- Laws and regulations

- Funding and funding policies

- Schools and administrative offices

- Teachers and staff

- Books, computers, and instructional materials

- Students, parents, and communities

Those seeking to improve an education system might choose to analyze the system’s parts. In this way, they can identify individual characteristics of each part and evaluate how it functions. While this approach can offer some benefits, it has limitations. It stops short of examining the relationships between the parts.

For example, limited school funding might result in high student-teacher ratios and inadequate supplies for students. These factors then lead to lower levels of student achievement which, in turn, puts further strain on teachers to help their students meet achievement benchmarks, and so on.

Responding to the growing demands placed on US education, solving problems such as achievement gaps, and dealing with shrinking school budgets are significant challenges. To face them effectively, educators need to value their system’s high level of interconnectivity and interdependency.

Applying Systems Thinking in Education

Systems thinking is a mindset that helps educators understand the complex education system in a more holistic way. Teachers and administrators using systems thinking might ask questions such as:

- How might cuts to arts education impact student performance in math?

- How can policies linking teacher salaries to standardized test scores affect a low-achieving school’s ability to attract accomplished teachers?

The goal is to consider several possible scenarios to find solutions to interconnected challenges.

Helping teachers solve classroom management issues, for instance, may involve addressing missing support structures in classrooms, such as a need for special education teachers, or adjusting student schedules to give time and space for children to unwind and release their energy.

As a mindset, systems thinking guides educators to deliver thought-provoking, engaging lessons. It encourages school leaders to coordinate districts and manage schools with improved efficiency. It can also replace piecemeal approaches to implementing policies with organized and systematic approaches that bring success across the board.

Specifically, educators can use systems thinking as a framework to structure classrooms and deliver instruction, while school and district leaders can apply it to their management and organizational styles. Additionally, administrators can use systems thinking as an approach to restructuring educational systems or schools.

Systems Thinking in the Classroom

Systems thinking can be a powerful classroom tool, giving students a participatory role in the learning process. By viewing teaching through a systems thinking lens, educators can help students recognize how seemingly disparate systems interact, identifying meaningful connections in the world around them. This not only deepens students’ understanding of specific subjects, but also strengthens their critical thinking abilities.

For example, teachers at Orange Grove Middle School in Tucson, Arizona, used a systems thinking approach to develop a project that strengthened their students’ abilities to analyze and problem solve. They tasked students with developing plans for a new national park that met specific design requirements: parks needed to be attractive to users, inflict limited environmental harm, and respect an Indian burial ground on the chartered land.

During the process of developing their designs, students discovered connections between the social, ecological, and economic components of the project.

Leadership and Systems Thinking

Systems thinking in education empowers education leaders to align school initiatives, improve instruction, increase efficiency, eliminate waste, and strengthen student outcomes.

For example, by closely monitoring student data, administrators can adjust budgets to allow for the purchase of the instructional materials they need most.

A systems thinking approach lets administrators build systems that do the following:

- Recognize and adapt to changes (technological advances, policy reforms), coordinating with other parts of the system fluidly

- Include mechanisms that allow for self-reflection and self-correction

- Process information quickly and make it available to all parts of the system

- Distinguish between situations that need adjustments and those that need overhauls

Discover How an EdD in Education Policy and Leadership Prepares Education Leaders to Excel

Building collaborative cultures in districts and schools calls for a holistic, innovative approach. Systems thinking in education allows education leaders to not only recognize the relationships between the different components of a school system but also use them to solve problems.

Explore how American University’s EdD in Education Policy and Leadership cultivates the knowledge and expertise leaders in education need to confront obstacles and transform schools.

The Role of Educational Leadership in Forming a School and Community Partnership

Path to Becoming a School District Administrator

5 Effective Principal Leadership Styles

Getting Smart, “Why School System Leaders Need to Be Systems Thinkers”

Journal of School Leadership , “Sources of Systems Thinking in School Leadership”

The Learning Counsel, “What Is Systems Thinking in Education?”

Medium, “How to Practice Systems Thinking in the Classroom”

Systems Thinker, “Revitalizing the Schools: A Systems Thinking Approach”

Systems Thinker, “Systems Thinking: What, Why, When, Where, and How?”

Request Information

- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Systems Thinking for School Leaders: A Comprehensive Approach to Educational Management

Systems thinking is a powerful approach that school leaders can harness to navigate the complex landscape of education. With increasing challenges, such as growing diversity, constant change, and intricate issues, applying a systems perspective allows educators to better understand and address these complexities holistically. By viewing schools as interconnected systems, leaders can identify potential points of intervention and anticipate the effects of their decisions on various aspects of the educational system.

Incorporating systems thinking into school leadership involves asking critical questions and examining the relationships between the different components of the system. Educators employing this mindset consider factors like how policy changes may impact student performance or how resource allocation influences teacher morale and student outcomes. By focusing on the big picture, school leaders develop a deeper understanding of the dynamic nature of the educational environment and are better equipped to make well-informed decisions that drive school improvement.

A successful implementation of systems thinking in a school setting not only empowers leadership, but also leads to excellence in education. Educators and administrators, through the application of systems-thinking concepts and procedures, ensure that decision-making is rooted in a solid understanding of the interdependencies and complexities inherent in the educational system. Ultimately, embracing systems thinking helps to foster an environment of continual reflection, adaptation, and growth for both students and educators alike.

Systems Thinking in School Leadership

Systems thinking is a crucial approach for school leaders aiming to drive improvement and enhance educational outcomes. This mindset helps educators and administrators understand complex educational systems more comprehensively and enables more effective decision-making.

Incorporating a systems thinking approach in school leadership involves analyzing how different elements within educational institutions influence each other. This holistic understanding can foster better-targeted strategies, promoting overall growth, learning, and development. For example, principals can closely examine how cutting arts education may impact students’ performance in math.

Emphasizing holistic school leadership, systems thinking counters traditional reductionism by encouraging leaders to consider various parts in the context of the whole. This allows them to identify patterns, interconnections, and possible leverage points, leading to a more sustainable and impactful change.

Utilizing systems thinking in educational leadership helps principals and administrators remain adaptable amid dynamic educational environments. It emphasizes the importance of understanding how interconnected components and subsystems interact with each other, which enables leaders to address challenges and optimize the school’s performance more effectively.

As important as systems thinking is, it is also essential for school leaders to maintain a sense of positivity and optimism. By adopting a positive approach, educational leaders can better inspire and motivate their staff, students, and communities. Being a confident and knowledgeable leader helps create a supportive environment where every member can achieve their potential.

In conclusion, systems thinking in school leadership is a valuable approach for navigating the complexities of educational systems, identifying underlying issues, and implementing impactful solutions. By embracing this mindset, educational leaders can effectively facilitate growth, learning, and success in their schools.

The Importance of Systems Thinking

Systems thinking is a crucial approach for school leaders, as it allows them to have a holistic understanding of the ever-evolving and complex educational landscape. By adopting systems thinking, educational leaders can effectively manage the inherent complexities of school organizations and make informed decisions that contribute to excellence in education.

In the realm of educational leadership, systems thinking enables leaders to view schools as a system of interconnected parts. This mindset is essential for effective strategic leadership, as it helps identify the relationships between different components and their impact on the overall performance of the school. For instance, teachers and administrators using systems thinking might ask questions such as how might cuts to arts education impact student performance in math .

By considering the compounding effects of various factors, school leaders can develop innovative solutions to complex problems and make decisions that better serve the long-term interests of their students and staff. This holistic leadership approach has been highlighted in a qualitative study spanning over two academic years , which emphasizes the practical ways in which principals lead schools using systems thinking concepts and procedures.

Furthermore, embracing systems thinking in education supports ongoing improvement by encouraging leaders to regularly assess the outcomes of their decisions. As a management approach, systems thinking helps managers cope with increasing complexity and change . By analyzing the cause-and-effect relationships between different parts of the system, school leaders can identify areas for growth and adjust their strategies accordingly.

In summary, the adoption of systems thinking in the field of educational leadership is essential for promoting excellence in education. By considering the interconnectedness of various components within the education system, school leaders can make well-informed decisions, drive innovation, and support the overall success of their schools.

Key Elements of Systems Thinking

Systems thinking is an approach that allows school leaders to navigate the complexity and interconnectedness of their educational environments. By understanding the key elements of systems thinking, leaders can develop a holistic perspective that fosters improved decision-making and problem-solving in their schools.

One core element of systems thinking is recognizing and acknowledging the complexity within school systems. Schools are made up of various interconnected parts, such as students, teachers, staff, parents, and the community. Understanding this complexity is crucial for leaders to make informed decisions that take into consideration the cascading effects of their actions on all stakeholders.

Another essential aspect of systems thinking is energy . Energy, in this context, refers to the resources and effort required to run a school effectively, including financial resources, human capital, and even emotional energy. Leaders must manage and distribute energy efficiently to prevent burnout, maintain motivation, and ensure the overall smooth functioning of the school system.

Systemic thinking involves viewing the school system as a whole, consciously examining its various elements and their relationships. It enables leaders to identify patterns and trends within the system, which can guide them in implementing effective solutions that promote synergy and cooperation.

Systems view is the ability to see the big picture of the organization and its environment, enabling school leaders to make decisions that align with the long-term goals and vision of the school. This perspective also helps leaders understand how changes in one part of the system can have ripple effects throughout the entire organization.

Systemic principles serve as guiding pillars for school leaders, allowing them to navigate the complexities of their work. These principles highlight the importance of being adaptive, data-driven, and reflective when making decisions, as well as emphasizing collaboration and cooperation among stakeholders.

In summary, systems thinking helps school leaders to manage the complexity and dynamics of their institutions by providing them with a comprehensive perspective, focused on the relationships and interactions among different elements. By incorporating systemic thinking, energy management, a systems view, and systemic principles into their leadership approach, school leaders can foster a supportive and thriving learning environment for all members of the school community.

Applying Systems Thinking to Schools

Systems thinking is a valuable approach that has the potential to benefit school organizations by addressing their inherent complexity. By viewing schools as interconnected systems, administrators can better understand the relationships between different components and make more informed decisions for overall improvement.

One key aspect of applying systems thinking to schools is recognizing the interdependence of various components within the education system. This includes students, teachers, parents, communities, and districts . Each of these groups plays a vital role in the overall functioning of the educational system, and their actions and decisions have consequences that reverberate throughout the system.

In practice, a systems thinking approach involves examining different aspects of the educational process, such as instruction and assessment, and understanding how these elements interact with one another. For instance, a focus on developing high-quality instructional materials may lead to increased student engagement and improved learning outcomes. In turn, this can result in higher satisfaction and trust amongst parents and the broader community.

In addition, systems thinking can be applied to education policy and leadership as a means to facilitate school improvement. Effective leaders can utilize systems thinking to identify key relationships, such as those between politics, management, and voice and choice in education. By understanding these relationships, leaders can better allocate resources, set priorities, and make strategic decisions that have a positive impact on the school community.

Consideration should also be given to the role of feedback loops in the educational system. For example, district leaders may receive input from parents, students, and teachers on various aspects of the school experience. This feedback can then be analyzed and used to inform decision-making, allowing for adjustments to be made to improve the overall quality of the educational experience. Furthermore, regularly engaging with stakeholders bolsters a sense of collaboration and shares the responsibility for school improvement.

In conclusion, applying systems thinking to schools can lead to better decision-making and more effective school operations. By taking into account the complex relationships that exist between different components of the educational system, school leaders can create a more holistic approach to education that benefits students, teachers, parents, and the broader community.

Challenges and Solutions

School leaders face several challenges in today’s dynamic educational environment. One major challenge involves adapting to change. This may manifest through changes in curriculum, technology, or societal expectations. Addressing these problems demands a comprehensive and adaptive management approach. Fortunately, a systems thinking perspective offers a holistic management strategy for school leaders, enabling them to navigate the complexities of modern education.

Systems thinking recognizes that schools are interconnected systems with numerous stakeholders, including students, teachers, staff, parents, and the wider community. This management approach promotes an understanding of how individual components within the school system impact one another, both positively and negatively. By acknowledging these interdependencies, school leaders can make well-informed decisions and facilitate meaningful change.

Implementing systems thinking in a school’s management can help address challenges, such as closing achievement gaps, improving student engagement, and optimizing resource allocation. School leaders who embrace this holistic approach can better identify root causes and explore multiple solutions to complex problems. For example, a systemic approach can enable school leaders to develop and align curriculum plans, instructional methods, and assessment practices more effectively. This ensures coherence and consistency within the entire educational process, ultimately benefiting students and teachers alike.

Moreover, systems thinking empowers school leaders to collaborate with stakeholders, fostering a shared vision focused on student success. This collaboration can yield innovation, trust-building, and collective problem-solving. By engaging the entire school community, stakeholders can better understand their roles and commit to working together towards long-term strategic goals.

In summary, systems thinking offers a comprehensive approach to help school leaders tackle the multifaceted challenges in today’s educational landscape. It provides the tools necessary to create a shared vision, facilitate meaningful change, and ensure schools function cohesively and effectively. Through this management approach, school leaders can confidently and knowledgeably navigate the complexities of their environment while promoting positive outcomes for their students and communities.

Strategies for Implementation

Systems thinking for school leaders is an innovative approach that addresses complex problems in education by examining the relationships and interdependencies within the system. This helps administrators to develop more effective strategies, align initiatives, and facilitate change at the local level. In order to implement systems thinking in schools, leaders can follow a few key steps.

First, it is essential for school leaders to understand the core systemic principles that underlie systems thinking. This includes recognizing the interconnectedness of various elements within the system, embracing feedback loops for ongoing improvement, and prioritizing long-term thinking over short-term fixes. By applying these principles, leaders can make better informed decisions that take into consideration the wider impact on the school community.

Next, leaders should involve all staff in the process of developing and implementing a systems thinking approach. This can be achieved through workshops, ongoing professional development sessions, or incorporating systems thinking training into the regular staff meetings. When the entire school community understands and adopts a systems thinking mindset, it becomes easier to enact changes and make adjustments as needed.

In terms of funding, it is crucial for school leaders to allocate resources strategically to support the adoption of systems thinking. This may involve reallocating existing funds to prioritize professional development in systems thinking or seeking additional funds through grants or partnerships. Ensuring that the entire school community has access to the necessary tools and resources is critical for the successful implementation of systems thinking strategies.

For the implementation to be successful, it is also essential for school leaders to adhere to relevant regulations and guidelines. This ensures that the strategies and initiatives are in compliance with local, state, and federal requirements as the school adopts a more holistic approach to problem-solving.

Finally, it is essential to continuously monitor and assess the impact of the implemented strategies. This can be done through data collection and analysis, focusing on both qualitative and quantitative measures. By consistently evaluating the effectiveness of the systems thinking approach, school leaders can make adjustments as needed and ensure continuous improvement within the school.

In conclusion, implementing systems thinking for school leaders takes a collaborative effort, involving staff, supportive funding, following regulations, and embracing an innovative approach. By adhering to systemic principles and using a clear, knowledgeable, and neutral tone throughout the implementation process, schools can experience the long-term benefits of systems thinking for lasting improvement and success.

Leadership and Systems Thinking

Systems thinking is a valuable approach for school leaders in today’s increasingly complex educational environment. By adopting a holistic perspective, administrators can better identify the interconnections between various aspects of school operations and make informed decisions. This section discusses how systems thinking can be utilized in aspects such as instructional leadership, public relations, program evaluation, decision-making, complexity theory, and strategic thinking.

Instructional leadership is essential for school improvement, and applying systems thinking can help leaders understand the dynamic interactions among teachers, students, and curricula. By considering the entire educational ecosystem, administrators can address the root causes of problems and implement more effective solutions. For example, they can analyze data trends to identify areas where student performance is lacking and coordinate resources to address these gaps.

Public relations is another area where school leaders can benefit from systems thinking. By acknowledging the school’s position within the wider community, leaders can establish meaningful connections with parents, local businesses, and policy-makers. By engaging these stakeholders and gathering their input, administrators can create a more supportive and inclusive environment that fosters student success.

Program evaluation is a critical component of continuous improvement, and systems thinking can help school leaders assess the effectiveness of their initiatives. By considering the interdependencies of various programs and their impacts on student learning, administrators can identify redundancies and areas of synergy. This information enables leaders to allocate resources more efficiently and optimize the allocation of funds for maximum impact.

Informed decision-making is a cornerstone of effective school leadership, and integrating systems thinking can improve the quality of decisions made by administrators. By examining the relationships between different elements of the school system, leaders can anticipate the consequences of their decisions and minimize unintended side effects. This proactive approach to leadership can prevent problems from escalating and promote a more adaptive and resilient educational environment.

Complexity theory is closely related to systems thinking and can provide valuable insights for school leaders. By understanding the non-linear and emergent nature of educational systems, administrators can better navigate the challenges and uncertainties of modern schooling. This mindset helps leaders embrace the inherent complexity of education and promotes a culture of adaptability and continuous learning.

Finally, strategic thinking is essential for long-term success, and systems thinking can enhance the planning and visioning process. By identifying the critical leverage points within a school system, leaders can devise more effective strategies for improvement. This holistic approach enables administrators to set clear objectives, track progress, and make necessary adjustments as new challenges and opportunities arise.

In summary, systems thinking offers school leaders a powerful tool for navigating the complexities of modern education. By integrating this approach into various aspects of leadership, administrators can better understand the intricate dynamics at play within their schools and make more informed decisions that promote excellence and continuous improvement.

Impact on Special Education

Systems thinking can have a significant impact on special education by promoting a more inclusive and comprehensive approach to addressing the needs of students with disabilities. By viewing special education within the larger context of the school system, leaders are better equipped to identify challenges and implement solutions that contribute to the overall success of all students.

One notable aspect of systems thinking is its emphasis on sustainability. In special education, this means looking beyond short-term interventions and focusing on creating enduring supports that benefit students with disabilities throughout their entire educational journey. By considering the long-term implications of decisions and programs, school leaders can foster environments that promote the success and growth of special education students.

In addition to sustainability, systems thinking encourages the use of evidence-based practices to guide decision-making in special education. By utilizing data and research to inform their strategies, school leaders can ensure that their approaches are grounded in proven methodologies and that resources are allocated effectively. For example, leaders might implement or advocate for inclusive education practices based on research demonstrating their positive impact on student outcomes.

Moreover, the holistic perspective of systems thinking supports the integration of special education within the overall framework of the school. By recognizing the interconnected nature of school components, leaders can identify opportunities for collaboration and support between general and special education staff. This can lead to the development of programs and interventions that meet the unique needs of students with disabilities while also benefiting the broader school community.

In conclusion, the application of systems thinking to special education can lead to more effective, sustainable, and evidence-based practices that ultimately benefit students with disabilities and the overall school system. By adopting a comprehensive approach that considers the larger context, school leaders can make a lasting positive impact on the educational experiences and outcomes of all students, including those in special education.

Research and Academic Exploration

Systems thinking is a valuable approach in school leadership, offering potential contributions to improve educational outcomes. However, the existing knowledge on systems thinking in school leadership remains limited, and there is a need for further academic exploration .

One direction for research is understanding the process of developing systems thinking skills among school leaders. By studying how these skills are acquired and nurtured, researchers can propose frameworks and methodologies for cultivating systems thinking capabilities in educational environments. Such findings would enable schools to better adapt and improve by understanding complex relationships and making informed decisions.

Another area of interest is exploring the impact of systems thinking on school improvement initiatives. Researchers can assess the effectiveness of this leadership approach in addressing problems within schools, enhancing communication, collaboration, and decision-making processes. By finding correlations between systems thinking implementation and improvements in performance metrics, research could offer empirical support for adopting this leadership style in educational settings.

Additionally, research can delve into the theoretical understanding of systems thinking, examining its foundations, and identifying potential linkages with other leadership theories. By identifying commonalities and distinctions between different leadership approaches, researchers can contribute to a more cohesive understanding of educational leadership as a whole. This could help in customizing effective leadership styles for different school contexts.

In summary, the research and academic exploration of systems thinking in school leadership is critical for expanding our understanding of this approach and its practical applications. By investigating its development, impact, and theoretical basis, researchers can contribute to enriching the field of educational leadership and ultimately enhancing the performance and well-being of schools and the students they serve.

You may also like

Systems Thinking vs. Linear Thinking: Understanding the Key Differences

Systems Thinking and Linear Thinking are two approaches to problem-solving and decision-making that can significantly impact the effectiveness of a given solution. […]

5 Ways to Apply Systems Thinking to Your Business Operations: A Strategic Guide

In today’s fast-paced business world, success depends on the ability to stay agile, resilient, and relevant. This is where systems thinking, an […]

Exploring Critical Thinking vs. Systems Thinking

There are many differences between Critical Thinking vs Systems Thinking. Critical Thinking involves examining and challenging thoughts or ideas, while Systems Thinking […]

Best Books on Systems Thinking: Top Picks for 2023

Systems thinking is an approach to problem-solving that embraces viewing complex systems as a whole, rather than focusing on individual components. This […]

Systems thinking to transform schools: Identifying levers that lift educational quality

- Download the full policy brief

Subscribe to the Center for Universal Education Bulletin

Bruce fuller and bruce fuller sociologist - university of california, berkeley, author - "when schools work" (2021) hoyun kim hoyun kim ph.d. student - berkeley school of education.

September 12, 2022

The United Nations has set forth an ambitious vision for education systems around the globe: cultivating lifelong learning from early childhood through an individual’s civic and work life. Schools must support children and youth in basic learning—including crucial socio-emotional, literacy, and numeracy competencies—to contribute to sustainable societies. State-run education systems and their communities must now engage these global goals by 2030.

But in the wake of the global pandemic, virtually every country in the world is far behind. Prior to the pandemic, a severe learning crisis held back hundreds of millions of children. Analysts project that 9 out of 10 children in low-income countries and 5 out of 10 in middle-income countries will not develop core secondary education skills in literacy and numeracy by 2030. The pandemic has only deepened the learning crisis and widened achievement gaps.

By crisply defining what systems entail in the education sector and which levers yield organizational change, education leaders and their partners can do better in rethinking the aims of schooling and raising student achievement.

Specific country cases remain distressing: More than half of fifth grade students in India are not proficient in second-grade literacy. In Nigeria, just 1 in 10 girls completing grade six can read a single sentence in their native language. In the United States, children of African-American or Latino heritage attending fourth grade read at two grade levels below white peers on average.

Beyond deepening inequality in foundational learning, calls to rethink the underlying aims of education grow louder and more urgent. The next generation’s future—marked by global warming, fragile economic sustainability, and worsening inequality—requires new skills and wider awareness, too often poorly addressed in classrooms around the globe. The digital revolution has already shifted what and how children learn and explore and the knowledge pathways they maneuver—a radical change that many education systems fail to harness to advance learning.

Related Content

The Hon. Minister David Sengeh, Rebecca Winthrop

June 23, 2022

Rebecca Winthrop, The Hon. Minister David Sengeh

Hayin Kimner, Stacey Campo, Abe Fernández

August 15, 2022

Against this evolving backdrop, the global education community—catalyzed by the U.N. Secretary General’s Transforming Education Summit (September 2022)—is looking past recovering from the pandemic to consider full-scale system transformation. This blossoming policy discourse is replete with hopes for radically improving and transforming education systems. But how to define educational systems and then reshape them remains poorly defined. We cannot merely utter this ambitious goal without precisely defining how to surround the system, identify potent levers for change, and rethink the aims and means of human learning on a fragile planet.

People also looked at

Book review article, book review: systems thinking for school leaders: holistic leadership for excellence in education.

- College of Education, Health and Aviation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, United States

A Book Review on Systems Thinking for School Leaders: Holistic Leadership for Excellence in Education

Haim Shaked and Chen Schechter, (Cham: Springer International Publishing AG), 2017, 140 pages, ISBN: 978-3-319-53571-5.

The authors of Systems Thinking for School Leaders: Holistic Leadership for Excellence in Education , Drs. Haim Shaked and Chen Schechter are distinguished scholars and prolific authors in the fields of systems thinking and leadership development. Dr. Shaked, a former elementary and high school principal, is currently the Vice President for Academic Affairs and Head of the Department of Education at Hemdat Hadarom College of Education. Dr. Schechter is a Professor of Leadership, Organizational Development, and Policy in the School of Education at Bar-Ilan University and also serves as the Editor-in-Chief (co) of the Journal of Educational Administration (JEA). Both Drs. Shaked and Schechter bring practical knowledge of and expertise in leadership preparation to the discussion of the acquisition and application of a systems thinking, or holistic, mindset in educational leadership.

The book is divided into two parts that follow what Shaked and Schechter (2017) refer to as a “funnel-shaped” (p. ix) structure moving from general information about systems thinking to the more specific and practical approach of implementation. Part I, The Environmental and Empirical Backdrop to Developing an Enhanced Systemic Leadership Approach , devotes four chapters to a summative review providing definitions and developments regarding systems thinking. After a brief introduction on the need for holistic school leadership, the authors review the evolution of systems thinking, the varied incarnations of systems methodologies, and the existing manifestations of systems thinking as it has been applied to school leadership. It is in Part I that the authors also wade through the multitude of systems thinking definitions from various disciplines to identify two major characteristics of systems-thinking, and the foundation for the approach of the book: (1) systems thinking is “seeing the whole beyond the parts” and (2) systems thinking is “seeing the parts in the context of the whole” (p. 11).

Part II is titled The Holistic School Leadership Approach and Guidelines for Its Implementation , and it dedicates six chapters to conceptual framework of holistic school leadership and application of systems thinking in educational contexts. As the title implies, in Part II, the authors define holistic school leadership, explain its importance as a framework for educational leaders, and provide guidance on putting the theory to action. Additionally, the authors identify four core characteristics of holistic school leadership: (1) leading wholes, (2) adopting a multidimensional view, (3) influencing indirectly, and (4) evaluating significance (p. 56) and explain not only the major sources for acquiring the knowledge and skills to employ the characteristics, but also a five-stage process through which development of holistic school leadership occurs. The authors acknowledge the complexity of systems-thinking, recognizing that building the capacity for holistic school leadership is accomplished through years of cultivation in a leader's career and also highlight the lack of literature in any discipline on the process(es) used by professionals to adopt a systems-thinking perspective, calling for increased empirical research to address this gap.

The authors are forthright about the purpose of this book—to argue that systems thinking may be beneficial for school leaders who face complex educational problems and to provide practical ways for school leaders as well as policy makers and leadership preparation programs to implement systems thinking through the holistic leadership framework. To achieve this purpose, the authors present their conceptual framework in an accessible format, intertwining relevant, real-life examples, and anecdotes from their own research of Israeli principals who demonstrate systems thinking with short, bulleted summaries of major concepts and themes. The authors also include as the final chapter a series of action principles related to the four characteristics and major sources of holistic school leadership. These action principles provide leaders with actionable steps they may think about or act upon in order to enhance or develop their own systems thinking perspective.

In both the preface and the conclusion to the book, Shaked and Schechter (2017) stress the importance of context in both developing and implementing a systems thinking perspective through the holistic leadership framework. For this reason, the authors present their framework not as a structured tool or program, but as pliable allowing policy makers, leadership preparation programs, and school leaders to adjust the characteristics based on identified needs and the local environment. Though they present the idea of holistic school leadership as “global” (p. x), the authors acknowledge the importance of attending to various situational contexts—of understanding the larger system in which the framework is operating—for successful implementation. This approach is exceptionally pertinent for current leaders in public education under increased regulatory pressure that cannot afford to ascribe to a rigid or narrow framework in attempts to achieve improved outcomes.

An important distinction between the holistic school leadership framework presented in this book and existing literature on systems thinking and school leadership is that this book does not present systems thinking solely as a means to address a specific problem or as an isolated strategy for school improvement reform. Drawing on previous research by Fullan (2004 , 2005 ), who also happens to have written the forward to this book, the authors argue that while the current body of literature has established the importance of systems thinking in education, it falls short of identifying the characteristics of using systems thinking comprehensively in the regular operations of a school. In Systems Thinking for School Leaders , however, Shaked and Schechter build on the systems work by Fullan and other researchers in the field to present the holistic school leadership framework as not only an approach to problem solving, but as a paradigm shift, one in which the school leader and ultimately the school staff think through their daily work with a systems mindset.

The authors are explicit about the audience for this book: “principal educators, policy makers, and especially school leaders” (p. x). Indeed, this book is a substantial choice for systems thinking exploration by each of the aforementioned audiences as well as any educational leader who is seeking sustainable transformation of not only an educational organization, but also a transformation of self.

Author Contributions

CE is a graduate student. JM-S is CE's graduate advisor and also the instructor for CE's directed reading in which the book in the review was the main text. CE wrote the first draft of the book review, and JM-S revised, edited, and restructured for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Fullan, M. (2004). Systems Thinkers in Action: Moving Beyond the Standards Plateau . Nottingham: DFES.

Fullan, M. (2005). Leadership and Sustainability: System Thinkers in Action . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Google Scholar

Shaked, H., and Schechter, C. (2017). Systems Thinking for School Leaders: Holistic Leadership for Excellence in Education . Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 140.

Keywords: systems thinking, educational leadership, principal preparation, school reform, holistic school leadership

Citation: Mania-Singer J and Erickson C (2018) Book Review: Systems Thinking for School Leaders: Holistic Leadership for Excellence in Education. Front. Educ . 3:62. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00062

Received: 23 May 2018; Accepted: 13 July 2018; Published: 03 August 2018.

Edited and reviewed by: John Timothy Brady , Chapman University, United States

Copyright © 2018 Mania-Singer and Erickson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jackie Mania-Singer, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Systems Thinking in the K-12 Classroom: Perspective, Practice, and Possibilities

How Systems Thinking Applies to Education

Current approaches, systems definitions, open systems, schools as open systems, implications for education.

- the piecemeal, or incremental, approach;

- failure to integrate solution ideas;

- a discipline-by-discipline study of education;

- a reductionist orientation;

- staying within the boundaries of the existing system (not thinking out of the box).

Figure 1. Key Evolutionary Markers

How Systems Thinking Applies to Education - table

- Energy is transformed, and something new is produced.

- A product is exported into the environment.

- The pattern of energy exchange is cyclical; the product that is exported into the environment is the source of energy for repetition of the cycle of activities.

- The system aims to “maximize its ratio of imported to expended energy.”

- The system exhibits differentiation, a tendency toward increased complexity through specialization.

- It interacts with constantly changing (multiple) environments and coordinates with many other systems in the environment.

- It copes with constant change, uncertainty, and ambiguity while maintaining the ability to co-evolve with the environment by changing itself and transforming and the environment.

- It lives and deals creatively with change and welcomes—not just tolerates—complex and ambiguous situations.

- It becomes an organizational learning systems, capable of differentiating among situations where maintaining the organization by adjustments and corrections is appropriate (single-loop learning) and those where changing and redesigning are called for (double-loop learning) (Argyris 1982).

- It seeks and finds new purposes, carves out new niches in the environment, and develops increased capacity for self-reference, self-correction, self-direction, self-organization, and self-renewal.

- It recognizes that the continuing knowledge explosion requires a two-pronged increase in specialization and diversification and integration and generalization.

- It increases the amount of information it can process, processes it rapidly, distributes it to a larger number of groups and people, and transforms the information into organizational knowledge.

- outcomes (broad statements of purpose);

- outcome-related standards;

- benchmarks for each standard against which to measure individual and program progress continuously;

- assessment based on performance compared to benchmarks, not to other students (feedback);

- self-assessment;

- triangulation (use of multiple forms of assessment by multiple assessors to increase the validity and reliability of feedback);

- immediate intervention;

- generative learning (Wittrock 1974);

- reflective practice (Schon 1987, Educational Leadership 1991);

- balanced instructional design (Betts and Walberg, unpublished manuscript);

- varied learning structures (self-directed, one-to-one, small groups, lecture, field study, apprenticeships, mentoring);

- year-round schooling;

- assignment to learning groups based on individual performance, rather than age-grade distinctions;

- intact teams working over an extended period of time (more than one year) to achieve a common goal;

- increased sources of information via telecommunications from school and home, through peer and cross-age relationships, using cooperative learning structures, from video and optical media, supported by fully integrated, interactive computer-assisted instruction through a variety of electronically linked community resources (home, school, work, libraries, recreation centers, health care facilities, churches);

- increased access to information;

- digitized student information and instructional resources, fully accessible via touch-tone phone;

- “electronic books”;

- multilingual resources;

- multimedia delivery (sound, graphics, and/or text options);

- tightly integrated curriculum, instruction, and assessment, such as total immersion second language instruction;

- hierarchy of small, six-to-eight person, self-sufficient, semiautonomous teams (sub-systems).

Ackoff, R. L. (1981). Creating the Corporate Future . New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Ackoff, R. L. (1986). Management in Small Doses . New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Argyris, C. (1982). Reasoning, Learning, and Action . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Banathy, B. H. (1991). Systems Design of Education: A Journey to Create the Future . Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Educational Technology Publications.

Betts, F.M., and H.J. Walberg. (Unpublished manuscript). “Improving Student Achievement through Balanced Instructional Design.”

Boulding, K. E. (1956). The Image . Ann Arbor, Mich.: The University of Michigan Press.

Educational Leadership . (March 1991). Theme Issue on “The Reflective Educator.” Alexandria, Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Katz, D., and R. L. Kahn. (1969). “Common Characteristics of Open Systems.” In Systems Thinking , edited by F. E. Emery. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books Ltd.

Schon, D. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wittrock, M.C. (1974). “Learning as a Generative Process.” Educational Psychologist 11: 87–95.

Frank Betts has been a contributor to Educational Leadership.

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action., from our issue.

To process a transaction with a Purchase Order please send to [email protected]

Integration and Implementation Insights

A community blog and repository of resources for improving research impact on complex real-world problems

How systems thinking enhances systems leadership

By Catherine Hobbs and Gerald Midgley

Systems leadership involves organisations, including governments, collaborating to address complex issues and achieve necessary systemic transformations. So, if this is the case, how can systems leadership be helped by systems thinking?

Systems leadership is concerned with facilitating innovation by bringing together a network of organisations. These then collaborate between themselves and with other stakeholders to deliver some kind of service, influence a policy outcome or develop a product that couldn’t have been achieved by any one of the organisations working alone.

Recognising that a network of organisations can achieve something that emerges from their interactions involves a certain amount of implicit systems thinking. After all, the classic definition of a ‘system’ is an identifiable collection of two or more parts that has properties, or achieves outcomes, that can only be attributed to all of the parts interacting, not any one of the parts in isolation. These properties or outcomes may be intended ( eg ., a service, policy or product), unintended ( eg ., contributing to climate change), or both.

However, systems thinking, when pursued explicitly, involves much more than just recognising that a network of collaborating organisations is a system. It helps leaders review a wide range of opportunities for change by encouraging them to question the existing system – the boundaries of it, different perspectives on it, the relationships within it (and between it and its wider environment) and how the parts cohere into a system with particular emergent properties, achievements or impacts. Any or all of these forms of questioning could be relevant to addressing a complex issue and achieving a transformation.

Through systems thinking, leaders can generate deeper insights, guard against unintended consequences and co-ordinate action more effectively. Various systems thinking approaches exist. They can help guide (but should not dictate) processes of deliberation to improve complex problematic situations and develop more desirable futures.

Although each individual systems thinking approach has its own strengths and weaknesses, the true power of systems thinking comes from exploring the unique context at hand and designing a bespoke programme that draws on the best of many approaches. Principles and methods may be borrowed from one or more of the available approaches and creatively combined. Some of these are discussed below.

How to question assumptions

Decision-making is inevitably based on underlying assumptions about the boundary of the issue at hand, and therefore what purposes should be pursued and what values are relevant. Systems thinking can be used to surface these assumptions and consider alternatives. A number of approaches address this, including:

- Boundary Critique, or who and what should count? By asking who and what should count early in a project, conflict and marginalisation (of both people and issues) can be identified and addressed. Understanding power relationships helps people decide which subsequent systems approaches are going to be most appropriate for policy or service design.

- Critical Systems Heuristics, which offers twelve boundary questions. Questions such as: ‘who or what should benefit from the service, and how?’ and ‘what should count as expertise?’ help guide reflection on what the system currently is , and what it ought to be. They support people in thinking about motivation, decision-making power, sources of knowledge, and legitimation. The full set of questions can be found in a blog post by Gerald Midgley on Critical Back-Casting . The questions can be phrased in plain English, and can therefore be answered by ‘ordinary’ citizens as well as policy makers. They are particularly useful in multi-agency settings when there is a need to rethink governance.

How to explore wider contexts

Although it can seem overwhelming to explore wider contexts, there are established approaches that help with mapping the bigger picture and thinking about strategic responses:

- shape people’s understandings of the multi-dimensional problem;

- design several packages of possible policy responses;

- compare these packages; and

- choose between them.

- The Viable System Model for assessing the responsiveness of an organisation or multi-organisational network to a changing world. An organisation has an environment, comprised of all the changing economic, social and ecological needs, demands, opportunities and threats that the organisation might have to respond to. The Viable System Model looks at how an organisation responds to its environment in terms of operations ( eg ., service provision), coordination, management, intelligence about the future, and strategic oversight. The model can be used at multiple scales, so, where appropriate, relationships between local, regional, national and international systems can be visualised. It can be used to diagnose problems in existing organisations and networks, or to design new ones. Although the visual representation of the model can look complex at first, it is widely applicable and can yield powerful new insights.

How to engage people

Systems thinkers need to welcome a variety of stakeholder and citizen viewpoints, and account for them in designing or refreshing policies, services or products. Common approaches include:

- ‘rich picture’ building, to get a visual ‘map’ of people’s perceptions of a complex problem;

- identifying possible transformations that could be pursued from different stakeholder perspectives, and visualising the actions that would be needed;

- reflecting on the options and asking what kind of transformational approach is likely to best address the problem situation; and

- finding accommodations between stakeholders to agree the most desirable and feasible way forward.

- Community Operational Research for citizen-engaged transformations . Community Operational Research is about working participatively with local communities. It draws on several systems thinking approaches, including those discussed above. The focus is on meaningful community engagement in setting agendas for transformation and acting on those agendas. This work resists the top-down design and implementation of policy in favour of co-design and co-production with multiple stakeholders, communities and citizens.

Implications for systems leadership

All of the above are design-led approaches. They can aid us in thinking and acting more systemically, and they generate ‘on the ground’ insights by cultivating collective intelligence. Most of the approaches can be used in workshops, either bringing stakeholders together, or working with separate groups when power relationships make that more appropriate. Since the onset of COVID-19, many such workshops have been moved online.

If informed by these kinds of systems thinking approaches, the systems leadership practice of the future could be more exploratory, design-led, participative, facilitative, and adaptive – addressing complex, multi-faceted ecological, social, cultural, economic and personal priorities through the deliberate adoption of a process of shared endeavour. It could also help leaders better tackle the single-organisation or single-department ‘silo’ mentality that so often threatens to undermine systems leadership.

Questions for readers

What has your experience been in using systems leadership and systems thinking to address complex problems in government or other organisations? Do you have additional methods, tips or experiences to share? Do you think that useful distinctions can be made between the terminology of systems leadership and systemic leadership?

To find out more : This blog post is adapted from the following resource, written for and published by a branch of the UK Government: Hobbs, C. and Midgley, G. (2020). How systems thinking enhances systems leadership . National Leadership Centre, London. (Online): https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/926868/NL-thinkpiece-Systems-Leadership-HOBBS-MIDGLEY.pdf (PDF 340KB). This also provides references for all of the approaches described.

In addition, the format of this National Leadership Centre think-piece was based upon three of the five operational principles around ‘what matters?’ drawn from Catherine Hobbs’ Adaptive Learning Pathway for Systemic Leadership . For a fuller account of the Adaptive Learning Pathway and summarised descriptions of more approaches ( eg ., strategic assumption surfacing and testing, metaphor, Cynefin, causal loop mapping, interactive planning, lean, and vanguard), see Catherine Hobb’s (2019) book: Systemic Leadership for Local Governance . (Online): https://www.springer.com/gb/book/9783030082796?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIxfrNgcmR7wIVDSIYCh0-yQKuEAQYAyABEgIvUPD_BwE ; and, her blog post Adaptive social learning for systemic leadership .

Biography: Catherine Hobbs PhD is an independent researcher located in North Cumbria, as well as being a Visiting Fellow at Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. She is a social scientist with experience of working in academia and local government, with a focus on developing multi-agency strategies in transport and health. She is interested in developing better links between the practice of local governance and scholarly expertise in order to increase capacity to address issues of complexity through knowledge synthesis. She is also interested in the potential of applying and developing a variety of systems thinking approaches (in the tradition of critical systems thinking), with the innovation and design movements in public policy .

Biography: Gerald Midgley PhD is Professor of Systems Thinking in, and Co-Director of, the Centre for Systems Studies in the Faculty of Business, Law and Politics at the University of Hull, UK. He also holds Adjunct Professorships at Linnaeus University, Sweden; the University of Queensland, Australia; the University of Canterbury, New Zealand; Mälardalen University, Sweden; and Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. He publishes on systems thinking, operational research and stakeholder engagement, and has been involved in a wide variety of public sector, community development, third sector, evaluation, technology foresight and resource management projects .

Share this:

27 thoughts on “how systems thinking enhances systems leadership”.

Gerald and Catherine, thanks for bringing this up again: the article and the comments touch upon several issues I have come to see as critical in the meantime. Briefly, they have to do with the role of leadership and the perception of power, and the way these issues are dealt with in any discourse platform. One worrisome trend I see increasing, as a result of perhaps confusion about these things, is the retreat of many ‘leaders’ to small / local projects where the perception of of issue scopes, boundaries, and appropriate decision procedures remains manageable for local participants. But retreating to decision modes that don’t address larger ‘non-local’ issues very well, and then paradoxically lead many people to rely upon the strongman leader…

In a sense, avoiding the perception of power entities (even the most beneficial ‘leaders’ who can initialize discourse projects but on a larger than local platform) as potential big brother powers, using the very sophistication of the new tools and systems diagrams as means of marginalizing input from the less educated and informed — but very much affected — folks out there. Is there an issue of conflict between ‘improving systems leadership’ and democratic participation — especially when the issues transcend traditional governance boundaries so that traditional decision-making of the ‘democratic kind’, like majority voting, simply aren’t applicable? (Look at the contortions of the UN, for all its good intentions, to get around this issue…that still don’t manage to avoid or contain these insane wars). So systems models, empowerment and power, leadership and participation, need new evaluation and decision-making tools: how are these issues dealt with in the usual systems thinking as it is reflected in the (usually just one) systems diagrams?

Thank you Thorbjørn for your valued thoughts, which sit very much at the core of the crucial issues that we face.

Plato’s cave? Issues of leadership, power and discourse rumble on as they always have (and will) throughout history, and I share your concerns for a trend of a retreat towards manageability of decision procedures via adopting small scales and limited scoping. I interpret this as a desire to stay inside Plato’s cave, if you like. I take your point that there is thus reliance upon a ‘strongman leader,’ but I also perceive a trend where those who are dissatisfied with this situation are beginning to ally themselves to think, work and act in different ways, thus enacting a more emergent, dynamic form of systemic leadership. These are the people who are willing to emerge from Plato’s cave into the reality of the world, share the uncertainty and learn together. The Human Learning Systems movement is a good example of this dynamic impetus. See https://i2insights.org/2023/01/10/human-learning-systems/

Self-assessment At one time I was involved in a Comprehensive Performance Assessment process for a local authority and came to realise that the greatest value of that process is actually the self-assessment that is undertaken in order to provide evidence for the inspection. Self-assessment is not usually attended to.

A glorious variety of systems thinking approaches In proactively exploring approaches from systems thinking, operational research and complexity over the last 18 years, I have discovered a variety of approaches, each of which seem to be well tailored to help address the complex priorities of today and have been designed to consider the reality of multiple viewpoints and emancipation. They constitute a great deal more than just a static model or diagram in permitting new thought processes and discussions to take place, for those who are willing… No single model or tidy answers will do the job properly. We need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of a variety of approaches from systems thinking, complexity and operational research in the manner of Critical Systems Thinking. See https://i2insights.org/2023/04/04/pragmatism-and-critical-systems-thinking/ . That’s why we need to consider extending the dimensions of our thinking, planning, doing, evaluation and learning (both individually and together), around thinking differently, addressing assumptions, wider contexts (than is normal), considering wider participation with people, and systemic effectiveness. I see this as being about social learning for systemic leadership, which will inevitably be messy. ‘System leadership’ and ‘co-creation’ per se can be inadequate without the benefit of the critical (and self-critical) nature of a variety of systems thinking and other approaches. See https://i2insights.org/2016/07/07/co-creation-and-systems-thinking/ . Many systems thinking approaches are facilitative, and there is some interesting work around relating systems thinking and design thinking. See https://systemic-design.org/ .

Evaluation too has to evolve differently with these new processes and explorations as they emerge. You may find the work of Bob Williams of interest. See https://www.bobwilliams.co.nz/

A single crisis Working practices should ideally be compatible locally, regionally, sub-regionally, nationally and globally, anchored in sustainability (social, environment and economy): I do not see these scales as separate, but as inextricably woven together in the way we think about things. Yet a misguided concept of containment and ‘manageability’ has resulted in restrictive practices that deny our own capabilities in situations of complexity, both individually and together. I would agree that although there is reference to a state of ‘polycrisis’, our single crisis is one of perception (Capra).

Participation Thinking of your comment about systems leadership and democratic participation, it can sometimes be the case that multi-agency work has the potential to undermine the usual way of democratic decision-making – a UK example of this risk has been the development of Local Enterprise Partnerships which include decision-making around business interests (government funding is to cease in April 2024, providing ‘an opportunity for local leadership to determine local economic strategies and development’). Yet multi-agency working is the ‘bread and butter’ of local governance, and there are good examples of significant efforts of participation in addressing uncertainties and yet deciding to act – the Strategic Choice Approach is an example of this. See https://i2insights.org/2023/10/31/strategic-choice-approach/ . Also, substantial efforts are being made to consider inclusivity through changing practices of discourse. See https://i2insights.org/2023/03/07/inclusive-systemic-thinking/

We do owe it to ourselves and future generations to add this form of exploratory and sometimes messy design thinking to our capabilities, and indeed to move on to design processes that provide the capacity for this to happen – yet be able design something that is rooted in the practice of every-day, and accepted as such.

• Thanks, I very much appreciate hearing about such approaches, keeping one from the despair one might sink into just watching the daily news. This compels me to expand on my comment on Gerald’s inspiring ‘Introduction to Systems Thinking (ST)’ event yesterday. There I made a distinction between many approaches flying under the ST flag, focused on understanding of the problems we are dealing with, and the issues I have tried to explore. There are many such approaches, and I do see them as inspiring and useful.

• The differences are, first, that they usually are described as activities of relatively small ‘teams’, workshops orchestrated by ST experts, leading selected members of the organizations that act as the ‘’client’ of the projects. Those are what I call ’’local’ projects, they involve face-to-face activities and experiences — even with well-intended participation efforts with people in the ‘outside’ affected population. And yes, they can stay within the cave, or make amazing efforts to ‘get out’. But being small ‘live’ events, they can and often seem to rely on consensus-aiming decision tools like the old ‘town hall’ assemblies of small towns of the past.

• This, secondly, makes it look like they seem to ’stop’ at the collective, cooperative generation of ‘solutions’ – plans, — that emerge from these events, avoiding more thorough comparative evaluation. The ST tools of systems mapping, simulation models may help, but being part of larger organizations, they end up with recommendations which the organizational leadership has to decide to adopt or reject. I am asking whether more ’systematic’ analysis and evaluation procedures should be added to the ST process, and if so how.

• I see two main lines of justification. As one extreme, let me mention the ‘Pattern Language’ Approach of Christopher Alexander. It looks like an attempt to apply an ‘axiomatic’ approach to the built environment. Basically, he believed that he could identify ‘patterns’ as elements of the built environment, that are universally and timelessly ‘valid’; having what he calls ‘quality without a name’ (‘QWAN). Therefore, if designers, even together with participating users (in ‘live’ face-to-face events) use these valid patterns to construct complete designs of buildings, towns, the result will be guaranteed to have the same quality and validity; so no evaluation is necessary. The approach has been adopted as well as criticized; I won’t get into that. What I am wondering is whether the use of ST tools and approaches (that well may question traditional ‘cave’ habits) actually serve that same validating function, (but now use the ‘patterns’ of participation, questioning assumptions, inviting different frames of reference, and the amazing tools of simulation models), as the Pattern Language claims to guaranteeing Quality. And what would be the basis for the validity assumption for that?

• The overall concern is that truly ‘global’ projects cannot rely on small group activities, approaches, and decision tools, (though they may play a useful role in the process) I believe (is it an illusion?) that the global planning process must be a d i s c o u r s e, however well supported by new information technology, computer modeling, simulation, even AI tools, etc. The problem is, of course, that we currently do not have a p l a t f o r m to support such a discourse. It’s a problem like that of having to rebuild the ship on the high seas. And this task, together with the questions of what new techniques and provisions must be developed for it, does not even seem to be on the ST agenda? Or what am I missing?

Hi Thor/Cathy,

I will restrict myself to comments on aspects of this discussion not already picked up by Cathy. However, first let me indulge in one echoing of Cathy – I very much value Thor pushing against the drift to localism, as (for me) it is central to the question of how we can get to grips with large-scale issues that cannot be dealt with by nation states or geopolitical alliances acting alone.

First, let’s directly tackle the retreat into local action. I agree that this is happening in many quarters, but I don’t think it is motivated by a desire to remain within Plato’s cave, even unconsciously (if it were unconscious, presumably the base motivation would be the desire for a greater level of certainty). There are two reasons that I resist the Plato’s cave interpretation. First, the growing adoption of systems approaches that conceptualize systems thinking as strongly tied to critical thinking tells me that there is more and more epistemological sophistication out there nowadays: people are becoming increasingly aware that their perceptions are not merely a reflection of a reality ‘out there’ – there is a growing appreciation that we all actively create our realities based on past experiences (i.e., we predict or anticipate what’s out there), and our construction of our own realities is a far stronger force than the error correction we can engage in, so we miss many of our own errors. This kind of epistemological understanding is necessary for effective dialogue and action at any scale – very local or global – and there is increasing knowledge of it (albeit not at the level of sophistication that would be ideal). The second reason I don’t think the retreat to localism is motivated by a desire to remain in Plato’s cave is that the growing epistemological sophistication of decision makers includes a realization that there is no escape from the constructed nature of our own realities. The allegory of Plato’s cave depends on the idea that it’s possible for someone to see how we are all subject to illusion, and therefore appreciate what reality actually is. This is not actually the case. The best we can do is improve our error correction by becoming more consciously aware of the nature of our own perception, and therefore act more deliberatively, but there is no point at which we ‘see the world as it really is’. If I am right here, then it doesn’t matter whether we’re working hyper-locally or at a global scale: our worlds are just as constructed by our own minds, and while we can improve perception by checking things out through dialogue with others, we cannot assume that what we see is absolutely real, even when working at the smallest scale. To do so will disrupt effective action, even in very small groups.

So, what is actually happening with this retreat to the hyper-local? I suggest that there are several things happening at once:

1. The large majority of us are dependent on salaries for our survival, and the survival of our families. Relatively few of us can work for organizations like the UN and WHO that consciously set out to address global issues at a global scale. Whether we’re working in the public, private or third sectors, that means we are much more likely to end up as decision makers with a local remit (or at best national). People are simply acting out the remits they have in their jobs, and as far as their roles might let them, they may account for global issues, but there is often restricted scope for this – either because of tragedy of the commons issues (e.g., a company might become less competitive if it accepts a cost increase involved in better addressing its climate impacts) or because their human resources are stretched too thinly. Those of us in universities are similarly caught by this problem because funding agendas require us to work with stakeholders, and most of them will have a local remit (very few get to work with global issues at a global scale). In this sense, the nature of the economic system makes it extremely difficult for 99.9% of us to address global issues at a global scale, however much we might want to. It might be a little bit facile to say “capitalism is to blame”, but there really are systemic constraints here that require global governance solutions. I think this is the largest reason why decision makers appear to be retreating to localism.

2. Thor correctly identifies the “contortions” that institutions like the UN have to perform, and how their actions so often fall short of what is required to address global concerns. I believe that the inadequacy of global governance institutions has become an existential threat to humanity, and many other species on our planet. It seems to me that this kind of governance dysfunction makes many people find other places to work, where they might be more effective in their actions. Of course, these global governance dysfunctions are tied up with the pursuit of narrowly-defined national and geopolitical interests, and major national powers have stood in the way of the reform of global institutions for fear that they will be forced to adopt policies that compromise their national independence. In this respect, there is insufficient awareness of the potential for using ideas like the Viable System Model (VSM) to structure governance from global to local, as the VSM advocates a form of subsidiarity that grants autonomy at every level of governance, as long as that autonomy doesn’t harm others – if there is harm, then decision making needs to be at a higher level of governance. I have heard some people say that this will result in a drift of policy making to higher levels, thus alienating local populations, but this interpretation fails to appreciate just how radical the idea of local autonomy is in the VSM – it’s “autonomy within constraints”, and the constraints are only those concerned with preventing wider harms (including from the paralyzing effect of the tragedy of the commons). Of course, it’s an open question whether some national powers will ever accept such a model, as in some policy areas they might prefer to pursue narrow self-interest, turning a blind eye to the harms created – but there is at least a good reason to raise awareness of different ways to conceive of governance (e.g., using the VSM). Only then might the preference for localism, motivated by skepticism of any possibility of functional global governance, be countered.

3. In some countries, like the UK, the use of words like “global” has become taboo in many quarters. When Teresa May was the UK Prime Minister, she actually made the shocking statement that “if you believe you are a citizen of the world, then you are a citizen of nowhere”. It actually became newsworthy that Cambridge University refused to stop using the term “global” in its work. I have seen first hand, when working in New Zealand government, how using certain words like this can end up disqualifying people from funding. This further reinforces the valuing of local over global scales of governance.