An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ten Steps for Writing an Exceptional Personal Statement

Danielle jones , md, j richard pittman jr , md, kimberly d manning , md, facp, faap.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author: Kimberly D. Manning, MD, FACP, FAAP, Emory University School of Medicine, [email protected] , Twitter @gradydoctor

Corresponding author.

The personal statement is an important requirement for residency and fellowship applications that many applicants find daunting. Beyond the cognitive challenge of writing an essay, time limitations for busy senior residents on clinical rotations present added pressure. Objective measures such as scores and evaluations paint only a partial picture of clinical and academic performance, leaving gaps in a candidate's full portrait. 1 , 2 Applicants, seemingly similar on paper, may have striking differences in experiences and distances traveled that would not be captured without a personal narrative. 2 , 3 We recommend, therefore, reframing personal statements as the way to best highlight applicants' greatest strengths and accomplishments. A well-written personal statement may be the tipping point for a residency or fellowship interview invitation, 4 , 5 which is particularly important given the heightened competition for slots due to increased participation on virtual platforms. Data show that 74% to 78% of residency programs use personal statements in their interview selection process, and 48% to 54% use them in the final rank. 6 , 7 With our combined 50 years of experience as clerkship and residency program directors (PDs) we value the personal statement and strongly encourage our trainees to seize the opportunity to feature themselves in their words.

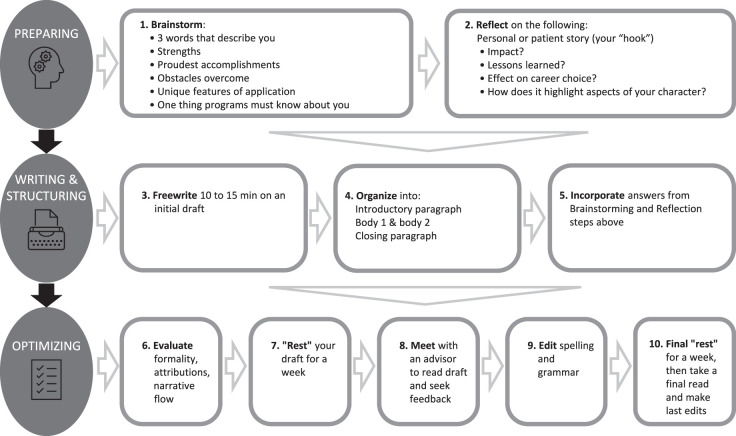

Our residency and medical school leadership roles position us to edit and review numerous resident and student personal statements annually. This collective experience has helped us identify patterns of struggle for trainees: trouble starting, difficulty organizing a cogent narrative, losing the “personal” in the statement, and failing to display unique or notable attributes. While a bland personal statement may not hurt an applicant, it is a missed opportunity. 4 , 8 We also have distinguished helpful personal statement elements that allow PDs to establish candidates' “fit” with their desired residency or fellowship. A recent study supports that PDs find unique applicant information from personal statements helpful to determine fit. 4 Personal statement information also helps programs curate individualized interview days (eg, pair interviewers, guide conversations, highlight desirable curricula). Through our work with learners, we developed the structured approach presented here ( Figure 1 ). Applicants can use our approach to minimize typical struggles and efficiently craft personal statements that help them stand out. Busy residents, particularly, have minimal time to complete fellowship applications. We acknowledge there is no gold standard or objective measures for effective personal statement preparation. 9 Our approach, however, combined with a practical tool ( Figure 2 ), has streamlined the process for many of our mentees. Moreover, faculty advisors and program leaders, already challenged by time constraints, can use this tool to enhance their coaching and save time, effort, and cognitive energy.

Structured Approach to Writing a Personal Statement

Ten Steps for Writing an Exceptional Personal Statement: Digital Tool

Note: Use the QR code to download the digital tool and follow the 10 steps highlighted in Figure 1.

Given word count and space limitations, deciding what to include in a personal statement can be challenging. An initial brainstorm helps applicants recall personal attributes and experiences that best underscore key strengths (Step 1). 10 Writing explicit self-affirmations is challenging, so we recommend pairing with a near peer who may offer insight. Useful prompts include:

What 3 words best encapsulate me?

What accomplishments make me proud?

What should every program know about me?

Reflecting on these questions (Step 2) helps elucidate the foundations of the narrative, 10 including strengths, accomplishments, and unique elements to be included. Additionally, the preparation steps help uncover the “thread” that connects the story sequentially. While not all agree that personal or patient stories are necessary, they are commonly included. 5 One genre analysis showed that 97% of applicants to residency programs in internal medicine, family medicine, and surgery used an opening that included either a personal narrative (66%) and/or a decision to enter medicine (54%) or the specialty of choice (72%). 9 Radiology PDs ranked personal attributes as the second most important component in personal statements behind choice of specialty. 9 Further, a descriptive study of anesthesia applicants' personal statements ranked those that included elements such as discussion of a family's or friend's illness or a patient case as more original. 3 We feel that personal and patient stories often provide an interesting hook to engage readers, as well as a mechanism to highlight (1) personal characteristics, (2) journey to and/or enthusiasm for desired discipline, and (3) professional growth, all without giving the impression of being boastful. Sketching these Step 2 fundamentals prepares applicants to begin writing with intention.

Writing and Structuring

Once key elements are identified, the next steps assist with the actual writing. Utilizing information gleaned from the “Preparing” steps, start with a freewriting exercise (Step 3), an unrestricted association of ideas aimed at answering, “What experiences have cultivated my strong interest in pursuing [______]?” At this stage, ignore spelling and grammar. Just write, even if the product is the roughest, rough draft imaginable. 10 Setting a timer for 10 to 15 minutes establishes a less intimidating window to start. Freewriting generates the essential initial content that typically will require multiple revisions. 10

Next, we recommend structuring the freewriting content into suggested paragraphs (Step 4), using the following framework to configure the first draft:

Introductory paragraph: A compelling story, experience, or something that introduces the applicant and makes the reader want to know more (the hook). If related to a patient or other person, it should underscore the writer's qualities.

Paragraph 2: Essential details that a program must know about the applicant and their proudest accomplishments.

Paragraph(s) 3-4: Specific strengths related to the specialty of choice and leadership experiences.

Closing paragraph: What the applicant values in a training program and what they believe they can contribute.

Evaluate what has been written and ensure that, after the engaging hook, the body incorporates the best pieces identified during the preparation steps (Step 5). A final paragraph affords ample space for a solid conclusion to the thread. Occasionally the narrative flows better with separate strengths and leadership paragraphs for a total of 5, but we strongly recommend the final statement not exceed 1 single-spaced page to reduce cognitive load on the reader.

This part of the process involves revising the piece into a final polished personal statement. Before an early draft is shared with others, it should be evaluated for several important factors by returning to the initial questions and then asking (Step 6):

“Does this personal statement…”

Amplify my strengths, highlight my proudest accomplishments, and emphasize what a program must know about me?

Have a logical flow?

Accurately attribute content and avoid plagiarism?

Use proper grammar and avoid slang or profanity?

While not as challenging as the other steps, optimization takes time. 10 At this stage, “resting” the draft for 1 week minimum (Step 7) puts a helpful distance between the writer and their work before returning, reading, and editing. 10 Writers can edit their own work to a point, but they often benefit by enlisting a trusted peer or advisor for critiques. Hearing their draft read aloud by a peer or advisor allows the applicant to evaluate the work from another perspective while noting how well it meets the criteria from the tool (provided as online supplementary data).

A virtual or in-person meeting between applicant and mentor ultimately saves time and advances the writer to a final product more quickly than an email exchange. Sending the personal statement in advance helps facilitate the meeting. Invite the advisor to candidly comment on the tool's criteria to yield the most useful feedback (Step 8). When done effectively, edits can be made in real time with the mentor's input.

We bring closure to the process by focusing on spelling and grammar checks (Step 9). Clarity, conciseness, and the use of proper English were rated as extremely important by PDs. 3 , 9 Grammatical errors distract readers, highlight inattention to detail, and detract from the personal statement. 3 , 9 Once more, we recommend resting the draft before calling it final (Step 10). If the piece required starting over or significant rewriting based on feedback received, we also suggest seeking additional feedback on this draft, ideally from someone in the desired residency or fellowship discipline. If only minor edits (eg, flow, language) were incorporated, the personal statement can be considered complete at this time.

Writing a personal statement represents a unique opportunity for residency and fellowship applicants to amplify their ERAS application beyond the confines of its objective components. 3 Using this stepwise approach encourages each personal statement to be truly personal and streamlines the process for applicants and reviewers alike. All stakeholders benefit: applicants, regardless of their scores and academic metrics, can arm themselves with powerful means for self-advocacy; PDs gain a clearer idea of individual applicants, allowing them to augment the selection process and curate the individual interview day; and faculty mentors can offer concrete direction to every mentee seeking their help.

- 1. Aagaard E, Abaz M. The residency application process—burden and consequences. N Engl J Med . 2016;374(4):303–305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1510394. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Demzik A, Filippou P, Chew C, et al. Gender-based differences in urology residency applicant personal statements. Urol . 2021;150:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.08.066. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, Beckerly R, Segal S. Have personal statements become impersonal? An evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth . 2010;22(5):346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.10.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Moulton M, Lappe K, Raaum SE, Milne CK, Chow CJ. Making the personal statement “truly personal”: recommendations from a qualitative case study of internal medicine program and associate program directors. J Grad Med Educ . 2022;14(2):210–217. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-21-00849.1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Joshi ART, Vargo D, Mathis A, Love JN, Dhir T, Termuhlen PMA. Surgical residency recruitment—opportunities for improvement. J Surg Educ . 2016;73(6):e104–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.09.005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey Accessed June 20 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf .

- 7. Naples R, French JC, Lipman JM, Prabhu AS, Aiello A, Park SK. Personal statements in general surgery: an unrecognized role in the ranking process. J Surg Educ . 2020;77(6):e20–e27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.021. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Barton E, Ariail J, Smith T. The professional in the personal: the genre of personal statements in residency applications. Iss in Writ . 2004;15(1):76–124. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Smith EA, Weyhing B, Mody Y, Smith WL. A critical analysis of personal statements submitted by radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol . 2005;12(8):1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.04.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Perdue University. Perdue Online Writing Lab (OWL) Invention Starting the Writing Process Accessed June 20. 2022. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/invention_starting_the_writing_process.html .

- View on publisher site

- PDF (367.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Office of Fellowships and Scholarships >

- Getting Started >

Develop a Strong Personal Statement

Jane Halfhill, 2023 recipient of a Fulbright research grant to study in Italy.

For students, the personal statement is one of the most difficult and most important documents they will ever write. We have the resources to boost your confidence and the know-how to help you write a powerful personal statement.

Debunking the Personal Statement

What it is:.

- Your introduction to the selection committee. This is your story, written by you. It should describe your interests, skills, questions and goals. It should clearly portray continued interest in your field of research and desire to learn more.

- A chance to demonstrate your ability to write and communicate effectively. A well-written personal statement demonstrates your ability to organize your thoughts and communicate clearly. Conversely, an unpolished statement can unintentionally portray the writer as disinterested, unprofessional and careless.

- Your personal statement should articulate your preparedness by clarifying how your past experiences, education and extra-curricular activities have prepared you for your field.

What it isn't:

- A personal autobiography. A personal statement is not the time to write about your childhood, family or hobbies that are not relevant to your field or academic development.

- A resume of accomplishments in essay form. Do not simply list information that is available in your other supporting documents (e.g., resume, transcript). Rather, you should provide context as to why your past accomplishments and experiences are significant to your academic and professional development.

- A plea for the scholarship. This is not the time to beg, plea or justify why you are more deserving of the scholarship than the other applicants. You are eligible for this scholarship for a reason. Focus on your accomplishments, not why your accomplishments make you better than others.

What to Include in Your Personal Statement

Professor Stacy Hubbard from UB's department of English breaks down what you should include in your personal statement.

- Origins of interest in a particular field. This could be a book you read, a lecture you attended or an experience you had.

- Ways in which you have developed your interest. Additional reading, experiments, internships, coursework, summer jobs, science fairs, travel experiences, writing projects, etc. Provide details about what you gained from a particular course or how a particular project or paper has helped you to develop intellectually.

- Reasons for changes in your interests and goals. These changes could be addressed in positive, rather than negative, terms. Instead of saying "I became bored with engineering and switched to physics," try "Through a bridge-design project, I discovered a new interest in thermodynamics and decided to focus my studies on physics."

- Reasons for inconsistencies in your record. If there is anything unusual or problematic in your record (poor grades, several school transfers, time away from school, etc.) this information needs to be explained in as positive a way, as possible. If you were immature and screwed up, then you matured and shaped up, say so and point to the proof (improved grades, a stellar recent employment record, etc.). Remember, failure of one kind or another, if you learn from it, is good preparation for future success.

- Special skills you have developed, relevant to the planned research. This could be general knowledge of a field acquired through reading and study or special practical skills (data analysis, fossil preservation, interviewing techniques, writing skills, etc.) that will qualify you to conduct a particular type of research. Be specific about how you acquired these skills and at what level you possess them.

- Character traits, talents or extra-curricular activities outside the field that help to qualify you. If you are particularly tenacious about overcoming obstacles, creative at problem-solving, adaptable to unfamiliar circumstances or just great at organizing teams of people, these qualities can be mentioned as relevant to the research experience. Sometimes the evidence for these traits may be other than academic. Have you have overcome a disability or disadvantage of some kind in your life? Have you persisted in a particularly challenging task? Have lived in different parts of the world and adapted to difference cultures? Have you organized teams of volunteers in the community? Make clear what traits have been developed by these experiences and how these will help you in the research experience. Acknowledge your strengths, but do so humbly.

- Knowledge and/or skills that you hope to acquire through participation in this opportunity. What is particularly intriguing to you about this opportunity? How will it help you to acquire new skills or carry forward your own research questions?

- Emerging and ongoing questions. What kinds of unsolved puzzles, problems or potential research paths are of interest to you? Which of these have you explored in school or extra-curricular projects? What sorts of projects do you hope to pursue in the future?

- Future plans and goals. Do you plan to go to graduate or professional school and in what field? What are your post-graduation goals and why? How would this research opportunity help you to achieve those goals?

The Do's and Don'ts of Writing a Personal Statement

- Adhere to the rules. Note the proper page layout, format and length, and adhere to it.

- Use proper spelling and grammar. An easy way to have your application overlooked is to submit it with spelling and grammatical errors. Use spell-checkers, proof-read and let others review your application, before you submit it.

- Show your audience, don't tell them. It's easy to say "I am a leader," but without concrete examples, your claim isn't valid. Give an example of why you believe you are a leader.

- Don't try to tell them everything. You can't cram your entire life into one personal statement. Choose a few key points to talk about and let your other application materials (resume, letter(s) of recommendation, application, interview, etc.) tell the rest of your story.

- Don't use clichés. Things like "since I was a child" or "the world we live in today" are commonly found in personal statements and don't add any value.

- Don't lie or make things up. This is not the time to fabricate or inflate your accomplishments. Don't try to guess what the committee is looking for and write what you think they want to hear. Invite them in to get to know the real you.

At the end of your personal statement, you want people to think "I'd like to meet this person." That is your end-goal.

UB Resources

- Center for Excellence in Writing

- Graduate Student Association Editing Services

Additional Resources

- Helping Students to Tell Their Stories , The Chronicle of Higher Education

- Preparing a Compelling Personal Statement , profellow.com

- Proposal Writing Resources , University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

- Purdue Online Writing Lab , Purdue University

- Writing a Winning Personal Statement for Grad School , gograd.com

IMAGES

VIDEO