Milestone Documents

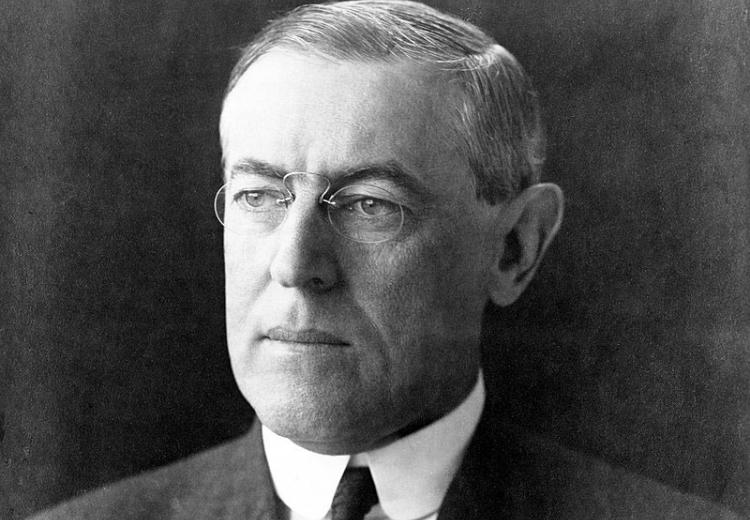

President Woodrow Wilson's 14 Points (1918)

Citation: President Wilson's Message to Congress, January 8, 1918; Records of the United States Senate; Record Group 46; Records of the United States Senate; National Archives.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

In this January 8, 1918, address to Congress, President Woodrow Wilson proposed a 14-point program for world peace. These points were later taken as the basis for peace negotiations at the end of World War I.

In this January 8, 1918, speech on War Aims and Peace Terms, President Wilson set down 14 points as a blueprint for world peace that was to be used for peace negotiations after World War I. The details of the speech were based on reports generated by “The Inquiry,” a group of about 150 political and social scientists organized by Wilson’s adviser and long-time friend, Col. Edward M House. Their job was to study Allied and American policy in virtually every region of the globe and analyze economic, social, and political facts likely to come up in discussions during the peace conference. The team began its work in secret, and in the end produced and collected nearly 2,000 separate reports and documents plus at least 1,200 maps.

In the speech, Wilson directly addressed what he perceived as the causes for the world war by calling for the abolition of secret treaties, a reduction in armaments, an adjustment in colonial claims in the interests of both native peoples and colonists, and freedom of the seas. Wilson also made proposals that would ensure world peace in the future. For example, he proposed the removal of economic barriers between nations, the promise of “self-determination” for oppressed minorities, and a world organization that would provide a system of collective security for all nations. Wilson’s 14 Points were designed to undermine the Central Powers’ will to continue, and to inspire the Allies to victory. The 14 Points were broadcast throughout the world and were showered from rockets and shells behind the enemy’s lines.

When Allied leaders met in Versailles, France, to formulate the treaty to end World War I with Germany and Austria-Hungary, most of Wilson’s 14 Points were scuttled by the leaders of England and France. To his dismay, Wilson discovered that England, France, and Italy were mostly interested in regaining what they had lost and gaining more by punishing Germany. Germany quickly found out that Wilson’s blueprint for world peace would not apply to them.

However, Wilson’s capstone point calling for a world organization that would provide some system of collective security was incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles. This organization would later be known as the League of Nations. Though Wilson launched a tireless missionary campaign to overcome opposition in the U.S. Senate to the adoption of the treaty and membership in the League, the treaty was never adopted by the Senate, and the United States never joined the League of Nations. Wilson would later suggest that without American participation in the League, there would be another world war within a generation.

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

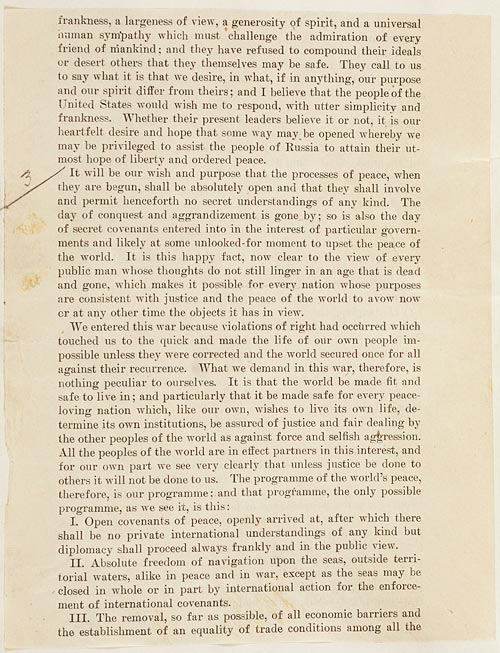

It will be our wish and purpose that the processes of peace, when they are begun, shall be absolutely open and that they shall involve and permit henceforth no secret understandings of any kind. The day of conquest and aggrandizement is gone by; so is also the day of secret covenants entered into in the interest of particular governments and likely at some unlooked-for moment to upset the peace of the world. It is this happy fact, now clear to the view of every public man whose thoughts do not still linger in an age that is dead and gone, which makes it possible for every nation whose purposes are consistent with justice and the peace of the world to avow now or at any other time the objects it has in view.

We entered this war because violations of right had occurred which touched us to the quick and made the life of our own people impossible unless they were corrected and the world secure once for all against their recurrence. What we demand in this war, therefore, is nothing peculiar to ourselves. It is that the world be made fit and safe to live in; and particularly that it be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, wishes to live its own life, determine its own institutions, be assured of justice and fair dealing by the other peoples of the world as against force and selfish aggression. All the peoples of the world are in effect partners in this interest, and for our own part we see very clearly that unless justice be done to others it will not be done to us. The programme of the world's peace, therefore, is our programme; and that programme, the only possible programme, as we see it, is this:

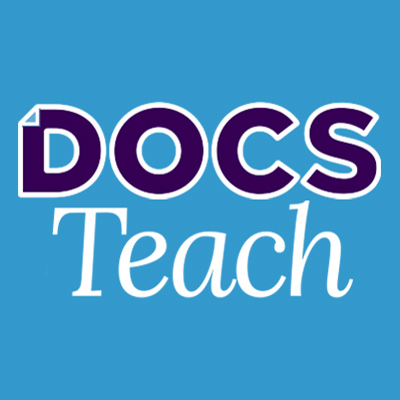

I. Open covenants of peace, openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.

II. Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.

III. The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.

IV. Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.

V. A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined.

VI. The evacuation of all Russian territory and such a settlement of all questions affecting Russia as will secure the best and freest cooperation of the other nations of the world in obtaining for her an unhampered and unembarrassed opportunity for the independent determination of her own political development and national policy and assure her of a sincere welcome into the society of free nations under institutions of her own choosing; and, more than a welcome, assistance also of every kind that she may need and may herself desire. The treatment accorded Russia by her sister nations in the months to come will be the acid test of their good will, of their comprehension of her needs as distinguished from their own interests, and of their intelligent and unselfish sympathy.

VII. Belgium, the whole world will agree, must be evacuated and restored, without any attempt to limit the sovereignty which she enjoys in common with all other free nations. No other single act will serve as this will serve to restore confidence among the nations in the laws which they have themselves set and determined for the government of their relations with one another. Without this healing act the whole structure and validity of international law is forever impaired.

VIII. All French territory should be freed and the invaded portions restored, and the wrong done to France by Prussia in 1871 in the matter of Alsace-Lorraine, which has unsettled the peace of the world for nearly fifty years, should be righted, in order that peace may once more be made secure in the interest of all.

IX. A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality.

X. The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development.

XI. Rumania, Serbia, and Montenegro should be evacuated; occupied territories restored; Serbia accorded free and secure access to the sea; and the relations of the several Balkan states to one another determined by friendly counsel along historically established lines of allegiance and nationality; and international guarantees of the political and economic independence and territorial integrity of the several Balkan states should be entered into.

XII. The Turkish portion of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development, and the Dardanelles should be permanently opened as a free passage to the ships and commerce of all nations under international guarantees.

XIII. An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

XIV. A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.

In regard to these essential rectifications of wrong and assertions of right we feel ourselves to be intimate partners of all the governments and peoples associated together against the Imperialists. We cannot be separated in interest or divided in purpose. We stand together until the end.

For such arrangements and covenants we are willing to fight and to continue to fight until they are achieved; but only because we wish the right to prevail and desire a just and stable peace such as can be secured only by removing the chief provocations to war, which this programme does remove. We have no jealousy of German greatness, and there is nothing in this programme that impairs it. We grudge her no achievement or distinction of learning or of pacific enterprise such as have made her record very bright and very enviable. We do not wish to injure her or to block in any way her legitimate influence or power. We do not wish to fight her either with arms or with hostile arrangements of trade if she is willing to associate herself with us and the other peace- loving nations of the world in covenants of justice and law and fair dealing. We wish her only to accept a place of equality among the peoples of the world, -- the new world in which we now live, -- instead of a place of mastery.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Woodrow Wilson’s 14 Points: How a Vision for World Peace Failed

By: Dave Roos

Updated: November 9, 2023 | Original: November 14, 2023

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, the United States vowed to remain neutral. The American people had no interest in becoming entangled in European alliances and empires. President Woodrow Wilson , a progressive Democrat, won reelection in 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of war.”

But that promise proved impossible to keep. Germany, which had temporarily paused unrestricted submarine warfare after the 1915 sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania , declared open season on American vessels in 1917.

Vowing to defend American lives and make the world “safe for Democracy,” Wilson and the U.S. Congress declared war on Germany in April of 1917.

“Wilson was very conscious that America didn’t want to get in the war,” says John Thompson, author of Woodrow Wilson: Profiles in Power . “The only way he could resolve that dilemma was to do everything he could to bring the European war to an end.”

Wilson and his advisors recruited a team of 150 political and social scientists to research the root causes of the war in Europe. That group, known as “The Inquiry,” produced nearly 2,000 reports and 1,200 maps that were boiled down to 14 key recommendations to achieve a stable peace in Europe.

In a speech before Congress on January 8, 1918, Wilson laid out his “ 14 Points ,” an ambitious blueprint for ending World War I that emphasized “national self-determination” for both small and large nations, and included the creation of a cooperative League of Nations to peaceably resolve all future disputes.

In 1919, Wilson attended the Paris Peace Conference with hopes that the 14 Points would form the backbone of the Treaty of Versailles . But Wilson’s ideas met fierce resistance from the Allies, who were more interested in punishing Germany than pursuing an idealistic plan for world peace.

The failure of the 14 Points is widely seen as one of the factors leading to the outbreak of World War II just two decades later.

Envisioning a ‘Peace Without Victory’

Months before the U.S. officially entered World War I , Wilson was already thinking about how it would end. In January of 1917, he gave a speech before Congress that laid the philosophical groundwork upon which the 14 Points would stand. Chief among Wilson’s ideas was the notion of “peace without victory.”

“Victory would mean peace forced upon a loser, a victor’s terms imposed upon the vanquished,” Wilson said . “It would be accepted in humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently, but only as upon quicksand. Only a peace between equals can last.”

Wilson understood that such a “peace between equals” would be a hard sell, particularly to the French. France suffered an unthinkable number of casualties during World War I—more than 1.3 million soldiers killed and another 600,000 civilian deaths. Russia, too, buried more than 2 million of its soldiers and citizens.

In drawing up what would become the 14 Points, Wilson and his advisors had to strike a balance between their progressive ideals and satisfying the demands for justice called for by allies like France, Britain and Russia.

5 Rules for a Peaceful World

Wilson was an idealist, but he wasn’t naive. He didn’t expect the warring powers of the world to simply drop their weapons, hold hands and promise to get along. Lasting peace required a new global framework based on a firm set of rules and governing principles.

When Wilson presented the 14 Points to the world in 1918, the first five proposals were dedicated to these governing principles:

- Public and transparent treaties and diplomatic agreements

Secret treaties and alliances sowed distrust between international governments. When the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in 1917, for example, Leon Trotsky published the secret treaties between the Tsarist government and the Allies. While Wilson was not a supporter of the Bolsheviks, he agreed that honest and open negotiations were the only way to achieve a permanent peace.

- Free navigation of the seas during times of both war and peace

The sinking of commercial and passenger vessels by German U-boats was what drew both Britain and the U.S. into World War I. Wilson believed that free and safe passage in international waters was essential for safeguarding peace.

- Equal trade conditions and opportunities

While falling short of “free trade,” Wilson’s third general principle called for “the removal, so far as possible,” of economic barriers to trade between all nations, both large and small. “Economics was one of the major reasons why Wilson wanted to be involved [in shaping the postwar world],” says Christopher Warren, chief curator at The National WWI Museum and Memorial . “Freedom of navigation, open trade—it would be incredibly economically advantageous for the U.S. to have a say in the stability of Europe.”

- Reduction of armaments among all nations

Well before the advent of nuclear weapons , Wilson called for all nations—both the winners and losers of global conflicts—to reduce their arms to “the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.”

- ‘Adjustment’ of colonial claims

The 14 Points called for “a free, open-minded and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims,” which sounds like a strong anti-imperialist stance. In practice, Wilson’s progressive commitment to “national self-determination” wasn’t applied universally. “Wilson was anti-imperialist when it came to the Central Powers—Austria-Hungary, Ottomans, Germany— but he didn't have any intention of touching Britain and France,” says Warren. “They weren't going to discuss any type of reduction of their overseas empires.”

8 Terms of Postwar Peace

After establishing those five general principles, the 14 Points made eight specific recommendations for resolving some of the major territorial disputes of World War I in places like France, Belgium, Russia, Italy and Poland.

While Wilson’s recommendations came down firmly in favor of the Allies, he was also careful not to alienate the Central Powers. In accordance with the philosophy of a “peace without victory,” the Central Powers would be held accountable, but their territorial claims wouldn’t be fully ignored.

Take the case of Austria-Hungary, whose empire stretched across most of Central and Eastern Europe. The British, under Prime Minister David Lloyd George, called for the total breakup of Austria-Hungary into a slew of independent nations. But Wilson, in his 10th point, was far more reserved, saying only that “the peoples of Austria-Hungary… should be accorded the freest opportunity of autonomous development.”

“Wilson was trying to strike a compromise between the two goals that he had,” says Thompson, “stability on the one hand and liberal principles of self-determination on the other.”

The 14 Points took a similarly measured approach in settling territorial disputes within the Ottoman and German empires. Germany would be required to return all of Alsace-Lorraine to the French, and to concede an independent Poland, but Wilson’s recommendations focused on “restoring” invaded territory, not exacting economic punishment.

“One of the reasons why German politicians became amenable to an Armistice is because they believed that Wilson was going to advocate on their behalf with his 14 Points,” says Warren. “They believed that the peace after the Armistice will be based on these 14 Points, which was much more palatable to them.”

The League of Nations, International Peacekeepers

Wilson’s 14th point is perhaps the best-known, a call for “a general association of nations” charged with safeguarding the “political independence and territorial integrity [of] great and small states alike.” This organization, the first international peacekeeping organization of its kind, came to be known as the League of Nations .

Wilson knew that a postwar Europe composed of large, weakened empires and small independent nations would be inherently unstable.

“He truly believed that if these small and large states couldn't solve their issues diplomatically, then this League of Nations—backed by the major democratic powers—could step in before they festered into a larger conflict,” says Thompson.

Failure at the Paris Peace Conference

When Wilson arrived in Paris in December 1919, he was the first sitting American president to travel to Europe. America, previously isolationist, was ready to claim its place as a global power and Wilson hoped that 14 Points would set a new standard for global diplomacy.

From the start, his hopes were dashed. For the peace process to work, the Central Powers needed to have an equal seat at the negotiating table. But the rest of the Allies took a hardline, refusing to participate if nations like Germany and Austria-Hungary had a say in the proceedings.

“Wilson conceded in the end,” says Thompson. “That was one of the major reasons why the peace failed to gain any sort of legitimacy in Germany. The Treaty of Versailles was seen as a diktat , not a peace in which all sides helped to shape.”

Other major provisions of the 14 Points were scuttled or watered down beyond recognition. Free navigation of the seas, for example, was rejected by the British, who controlled the most powerful navy in the world.

Several recommendations of the 14 Points were adopted by the Paris Peace Conference, including many of the territorial questions, and notably the creation of the League of Nations.

But the progressive spirit of the 14 Points, the one that gave Germany hope that this treaty would be different, was absent from the Paris Peace Conference. Instead, the Allies voted to impose stiff economic penalties on Germany in the form of war reparations totaling 132 billion gold marks, or more than $500 billion today.

In the end, Wilson’s bold framework for world peace failed to gain traction and the Treaty of Versailles became a bitter pill that the German people were forced to swallow. In the 1930s, when Germany’s economy was crippled by a global Depression, Adolph Hitler tapped into resentment over the punitive Treaty of Versailles to place the blame on scheming politicians and Jews.

Interestingly, the harshness of the Treaty of Versailles was also used as a justification for the appeasement policies of Britain and other European nations in response to Hitler’s aggressions. “They ceded ground to Hitler partly on the reasoning that the Versailles treaty had been unjust to Germany,” says Thompson.

The one potential bright spot for Wilson should have been the creation of the League of Nations, but even that victory eluded him. Congress at the time was in the hands of Republicans, whom Wilson excluded from the Paris peace talks. Republicans repaid Wilson by refusing to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, which kept the United States out of the League of Nations.

HISTORY Vault: World War I Documentaries

Stream World War I videos commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- WWI Essentials

- U.S. History

The Fourteen Points

In his war address to Congress on April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson spoke of the need for the United States to enter the war in part to “make the world safe for democracy.” Almost a year later, this sentiment remained strong, articulated in a speech to Congress on January 8, 1918, where he introduced his Fourteen Points.

Designed as guidelines for the rebuilding of the postwar world, the points included Wilson’s ideas regarding nations’ conduct of foreign policy, including freedom of the seas and free trade and the concept of national self-determination , with the achievement of this through the dismantling of European empires and the creation of new states. Most importantly, however, was Point 14, which called for a “general association of nations” that would offer “mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small nations alike.” When Wilson left for Paris in December 1918, he was determined that the Fourteen Points, and his League of Nations (as the association of nations was known), be incorporated into the peace settlements.

The Points, Summarized

1. Open diplomacy without secret treaties 2. Economic free trade on the seas during war and peace 3. Equal trade conditions 4. Decrease armaments among all nations 5. Adjust colonial claims 6. Evacuation of all Central Powers from Russia and allow it to define its own independence 7. Belgium to be evacuated and restored 8. Return of Alsace-Lorraine region and all French territories 9. Readjust Italian borders 10. Austria-Hungary to be provided an opportunity for self-determination 11. Redraw the borders of the Balkan region creating Roumania, Serbia and Montenegro 12. Creation of a Turkish state with guaranteed free trade in the Dardanelles 13. Creation of an independent Polish state 14. Creation of the League of Nations

President Wilson’s insistence on the inclusion of the League of Nations in the Treaty of Versailles (the settlement with Germany) forced him to compromise with Allied leaders on the other points. Japan, for example, was granted authority over former German territory in China, and self-determination—an idea seized upon by those living under imperial rule throughout Asia and Africa—was only applied to Europe. Following the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson returned to the United States and presented it to the Senate.

Although many Americans supported the treaty, the president met resistance in the Senate, in part over concern that joining the League of Nations would force U.S. involvement in European affairs. A dozen or so Republican “Irreconcilables” refused to support it outright, while other Republican senators, led by Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, insisted on amendments that would preserve U.S. sovereignty and congressional authority to declare war. Having compromised in Paris, Wilson refused to compromise at home and took his feelings to the American people, hoping that they could influence the senators’ votes. Unfortunately, the president suffered a debilitating stroke while on tour.

The loss of presidential leadership combined with continued refusal on both sides to compromise, led Senate to reject the Treaty of Versailles, and thus the League of Nations. Despite the lack of U.S. participation, however, the League of Nations worked to address and mitigate conflict in the 1920s and 1930s. While not always successful, and ultimately unable to prevent a second world war, the League served as the basis for the United Nations, an international organization still present today.

Return to Paris Peace Conference

- Advanced Search

Version 1.0

Last updated 08 october 2014, fourteen points.

The Fourteen Points were U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s post World War I blueprint to end territorial disputes in Europe, promote international commerce, and make the world safe for democracy. They were based on the ideas of open trade and collective diplomacy, and introduced the concept of national self-determination.

Table of Contents

- 1 Ideological Background

- 2 The Fourteen Points

- 3 Reception in Europe and Internationally

- 4 Reception in the United States

Selected Bibliography

Ideological background ↑.

President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) was a champion of democracy and saw the First World War as the consequence of a Europe that was governed, not by the people, but by power-hungry monarchs. America’s participation in the war was, for Wilson, an opportunity to “make the world safe for democracy.” A few years prior to the United States’ entrance into the Great War, Wilson had intervened in the Mexican Civil War in an effort to “teach them how to elect good men.” Nine months after the U.S. entry into the war, Wilson introduced the Fourteen Points in a speech to Congress on 8 January 1918. The points were presented as a platform upon which global peace and prosperity could be built. Along with his desire to spread democracy, Wilson was also motivated by his fear of communism spreading westward from the newly born Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In his own writings, Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) had championed disarmament, an end to making treaties without parliamentary approval, an international forum for diplomacy, and no changes in territorial boundaries without the consent of the people affected. While Wilson may have shared these political views, he staunchly opposed communism’s economic policies, as well as its atheism. The Fourteen Points offered Europe many of Lenin’s ideas, but on a liberal-democratic and capitalist foundation rather than a communist one.

The Fourteen Points ↑

Points one to four introduced general ideas that Wilson expected the nations of the world to adhere to in conducting foreign policy. The first point, open diplomacy, called for what today is referred to as transparency rather than secret alliances and partnerships for war. Wilson encouraged “open covenants of peace.” The next two points, freedom of the seas and free trade, argued for greater freedoms in commerce and trade and was certainly prompted by the United States’ wartime problems involving German U-boat attacks on American merchant ships. The fourth point, military disarmament, advocated a reduction in the peacetime armed forces of the world. In Wilson’s view the war broke out so quickly because European countries had armies at the ready. Future wars could thus be avoided by preventing nations from having armies prepared to go to war.

Point five introduced the concept of national self-determination. To Wilson, European empires were the antithesis of democracy; people have the right to determine who governs them and empires had taken away that right. The goal of point five was to dismantle European empires and to create new states organized along national-cultural lines. Points six to thirteen were specific steps for putting point five into action; for example, the monolith Austro-Hungarian Empire would be dismantled and out of it the nations of Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia , and parts of Yugoslavia would be created, each new nation sharing a common language, customs, and culture.

The fourteenth point was Wilson’s pride and joy. Wilson wanted a “general association of nations” that provided a forum for solving international crises with diplomacy instead of bullets. The realization of this point was the League of Nations . The League was to create a system of collective security that monitored world peace.

Reception in Europe and Internationally ↑

In 1918, with the failure of the St. Michael Offensive, Germany’s situation looked bleak. Its armies were defeated and its people were starving, while the rumblings of German communists grew louder in the cities. Fearing both revolution at home and total collapse at the front, the government requested an armistice using the Fourteen Points as its foundation. Under pressure, Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) abdicated on 9 November 1918, and the Weimar Republic was established. The new government hoped that the gesture would ingratiate Germany with Wilson, and make him an ally of the new republic in the forthcoming peace negotiations.

Wilson’s vision was met with cheers from the masses – in Paris the crowds screamed “Vive Wilson!” when he arrived for the peace conference – but ran into colder receptions from world leaders. Wilson’s dreams of democracy, free trade, and self-determination clashed with Europeans leaders’ goals of territorial gain and revenge against Germany. Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) , Prime Minister of France, upon hearing of Wilson’s Fourteen Points supposedly said, “God gave us the Ten Commandments and we broke them. Wilson gives us the Fourteen Points. We shall see.” [1]

The finished product of the conference, the Treaty of Versailles , contained only a fraction of the Fourteen Points. To ensure the realization of his association of nations, Wilson had to betray self-determination and its associated points. Japan , for example, wanted Chinese territory previously in German hands and threatened to quit the conference (and also the League), if not given what it wanted. Thus in the interests of his League of Nations, Wilson acquiesced and placed millions of Chinese in the control of the Japanese government . Point three – the removal of economic barriers - also suffered under the imperial ambitions of the victors. Wilson hoped, however, that the league, once functioning, could adjust these compromises.

Wilson only intended self-determination and the consent of the governed to apply to Europe. His upbringing in the American Jim Crow South made him oblivious to including non-whites in any discussion of political and social rights. However, despite his focus on Europe, the ideas of self-determination and public consent found fertile soil among nationalists and intellectuals in the colonies of European and American empires. These ideas gave subject peoples an ideological weapon to wield against the racism and ethnocentrism of the “White Man’s Burden.” This “ Wilsonian moment ” marked the beginning of decolonization, as nationalist leaders in China, Vietnam, Korea, Egypt, and India applauded the general principle and criticized the western powers for limiting it to Europe.

Reception in the United States ↑

Back in the United States, Wilson ran into staunch resistance in the Senate. Isolationists rejected the idea of belonging to a League of Nations that could entangle the country in European affairs once again. The leader of the Senate stonewall was Republican Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) , who presented Wilson with Fourteen Reservations that Congress wanted Wilson to address before they would ratify the Treaty of Versailles. The President, already having made compromises with European leaders, refused to discuss a single point with the Senate, and inseparably welded the League Covenant to the Treaty of Versailles, forcing Republicans to either accept or reject both. Ironically, the United States never ratified the treaty and therefore did not join the League of Nations, Wilson’s most beloved of his points.

Despite its immediate failures, the impact of the Fourteen Points, particularly self-determination, shaped the remainder of the 20 th century. European colonies in Asia and Africa used self-determination as a weapon to demand their independence, and, with the help of the Second World War, led to decolonization in the latter half of the century. At the same time, the next world war itself was brought on in large part by the idea of self-determination. Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and imperial Japan used the principle of self-determination to justify their plans of expansion and conquest.

The Fourteen Points did not make the world safe for democracy, nor did they prevent future conflicts. Most of the conflicts of the 20 th century were fueled by nationalism , as were the genocides and atrocities that accompanied those wars. Nevertheless, the ideas set forth in the Fourteen Points set a new standard of national identity, and the League of Nation’s successor, the United Nations, remains with us to this day.

Chris Thomas, J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

- ↑ As quoted in Bailey, Thomas: Woodrow Wilson Wouldn’t Yield, in: American Heritage, 8/4 (1957), online: http://www.americanheritage.com/content/woodrow-wilson-wouldn%E2%80%99t-yield (retrieved: 3 April 2014).

- Bailey, Thomas Andrew: Woodrow Wilson and the lost peace , New York 1944: Macmillan.

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr.: Woodrow Wilson. A biography , New York 2009: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr.: Breaking the heart of the world. Woodrow Wilson and the fight for the League of Nations , Cambridge; New York 2001: Cambridge University Press.

- Ferrell, Robert H.: Woodrow Wilson and World War I, 1917-1921 , New York 1985: Harper & Row.

- Knock, Thomas J.: To end all wars. Woodrow Wilson and the quest for a new world order , New York 1992: Oxford University Press.

- MacMillan, Margaret: Paris 1919. Six months that changed the world , New York 2002: Random House.

- Manela, Erez: The Wilsonian moment. Self-determination and the international origins of anticolonial nationalism , Oxford; New York 2007: Oxford University Press.

- Mee, Charles L.: The end of order, Versailles, 1919 , New York 1980: Dutton.

- Wilson, Woodrow: President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points , 1918.

Thomas, Chris: Fourteen Points , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI : 10.15463/ie1418.10085 .

This text is licensed under: CC by-NC-ND 3.0 Germany - Attribution, Non-commercial, No Derivative Works.

Related Articles

External links.

Ch. 26 World War I

Wilson’s fourteen points, 29.5.2: wilson’s fourteen points.

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles used for peace negotiations following the end World War I, outlined in a January 8, 1918, speech to the United States Congress by President Woodrow Wilson.

Learning Objective

Summarize the key themes of the Fourteen Points

- U.S. President Woodrow Wilson initiated a secret series of studies named The Inquiry, primarily focused on Europe and carried out by a group in New York that included geographers, historians, and political scientists. This group researched topics likely to arise in the anticipated peace conference.

- The studies culminated in a speech by Wilson to Congress on January 8, 1918, in which he articulated America’s long-term war objectives.

- The speech, known as the Fourteen Points, was authored mainly by Walter Lippmann and projected Wilson’s progressive domestic policies into the international arena.

- It was the clearest expression of intention made by any of the belligerent nations and was generally supported by the European nations.

- The first six points dealt with diplomacy, freedom of the seas, and settlement of colonial claims; pragmatic territorial issues were addressed as well, and the final point regarded the establishment of an association of nations to guarantee the independence and territorial integrity of all nations—a League of Nations.

- The actual agreements reached at the Paris Peace Conference were quite different than Wilson’s plan, most notably in the harsh economic reparations required from Germany. This provision angered Germans and may have contributed to the rise of Nazism in the subsequent decades.

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles used for peace negotiations to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918, speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress by President Woodrow Wilson. Europeans generally welcomed Wilson’s points, but his main Allied colleagues (Georges Clemenceau of France, David Lloyd George of the United Kingdom, and Vittorio Orlando of Italy) were skeptical of the applicability of Wilsonian idealism.

The United States joined the Allied Powers in fighting the Central Powers on April 6, 1917. Its entry into the war had in part been due to Germany’s resumption of submarine warfare against merchant ships trading with France and Britain. However, Wilson wanted to avoid the United States’ involvement in the long-standing European tensions between the great powers; if America was going to fight, he wanted to unlink the war from nationalistic disputes or ambitions. The need for moral aims was highlighted when after the fall of the Russian government, the Bolsheviks disclosed secret treaties made between the Allies. Wilson’s speech also responded to Vladimir Lenin’s Decree on Peace of November 1917 immediately after the October Revolution, which proposed an immediate withdrawal of Russia from the war, called for a just and democratic peace that was not compromised by territorial annexations, and led to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918.

The speech made by Wilson took many domestic progressive ideas and translated them into foreign policy (free trade, open agreements, democracy, and self-determination). The Fourteen Points speech was the only explicit statement of war aims by any of the nations fighting in World War I. Some belligerents gave general indications of their aims, but most kept their post-war goals private.

Background and Research

The immediate cause of the United States’ entry into World War I in April 1917 was the German announcement of renewed unrestricted submarine warfare and the subsequent sinking of ships with Americans on board. But President Wilson’s war aims went beyond the defense of maritime interests. In his War Message to Congress, Wilson declared that the United States’ objective was “to vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world.” In several speeches earlier in the year, Wilson sketched out his vision of an end to the war that would bring a “just and secure peace,” not merely “a new balance of power.”

President Wilson subsequently initiated a secret series of studies named the Inquiry, primarily focused on Europe and carried out by a group in New York that included geographers, historians, and political scientists; the group was directed by Colonel Edward House. Their job was to study Allied and American policy in virtually every region of the globe and analyze economic, social, and political facts likely to come up in discussions during the peace conference. The group produced and collected nearly 2,000 separate reports and documents plus at least 1,200 maps. The studies culminated in a speech by Wilson to Congress on January 8, 1918, in which he articulated America’s long-term war objectives. The speech was the clearest expression of intention made by any of the belligerent nations and projected Wilson’s progressive domestic policies into the international arena.

The Speech to Congress

The speech, known as the Fourteen Points, was developed from a set of diplomatic points by Wilson and territorial points drafted by the Inquiry’s general secretary, Walter Lippmann, and his colleagues, Isaiah Bowman, Sidney Mezes, and David Hunter Miller. Lippmann’s draft territorial points were a direct response to the secret treaties of the European Allies, which Lippman was shown by Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. Lippman’s task according to House was “to take the secret treaties, analyze the parts which were tolerable, and separate them from those which we regarded as intolerable, and then develop a position which conceded as much to the Allies as it could, but took away the poison…It was all keyed upon the secret treaties.”

In the speech, Wilson directly addressed what he perceived as the causes for the world war by calling for the abolition of secret treaties, a reduction in armaments, an adjustment in colonial claims in the interests of both native peoples and colonists, and freedom of the seas. Wilson also made proposals that would ensure world peace in the future. For example, he proposed the removal of economic barriers between nations, the promise of self-determination for national minorities, and a world organization that would guarantee the “political independence and territorial integrity [of] great and small states alike”— a League of Nations.

Though Wilson’s idealism pervades the Fourteen Points, he also had more practical objectives in mind. He hoped to keep Russia in the war by convincing the Bolsheviks that they would receive a better peace from the Allies, to bolster Allied morale, and to undermine German war support. The address was well received in the United States and Allied nations and even by Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin as a landmark of enlightenment in international relations. Wilson subsequently used the Fourteen Points as the basis for negotiating the Treaty of Versailles that ended the war.

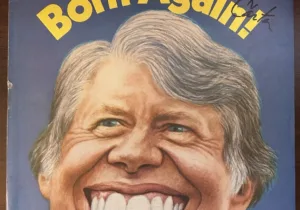

Wilson’s Fourteen Points: Wilson with his 14 points choosing between competing claims. Babies represent claims of the English, French, Italians, Polish, Russians, and enemy. American political cartoon, 1919.

Fourteen Points vs. the Versailles Treaty

President Wilson became physically ill at the beginning of the Paris Peace Conference, allowing French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau to advance demands substantially different from Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Clemenceau viewed Germany as having unfairly attained an economic victory over France, due to the heavy damage their forces dealt to France’s industries even duringretreat, and expressed dissatisfaction with France’s allies at the peace conference.

Notably, Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, which would become known as the War Guilt Clause, was seen by the Germans as assigning full responsibility for the war and its damages on Germany; however, the same clause was included in all peace treaties and historian Sally Marks has noted that only German diplomats saw it as assigning responsibility for the war.

The text of the Fourteen Points had been widely distributed in Germany as propaganda prior to the end of the war and was thus well-known by the Germans. The differences between this document and the final Treaty of Versailles fueled great anger. German outrage over reparations and the War Guilt Clause is viewed as a likely contributing factor to the rise of national socialism. At the end of World War I, foreign armies had only entered Germany’s prewar borders twice: the advance of Russian troops into the Eastern border of Prussia, and following the Battle of Mulhouse, the settlement of the French army in the Thann valley. This lack of important Allied incursions contributed to the popularization of the Stab-in-the-back myth in Germany after the war.

Attributions

- “The Inquiry.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Inquiry . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Stab-in-the-back myth.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stab-in-the-back_myth . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Idealism in international relations.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Idealism_in_international_relations . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Fourteen Points.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fourteen_Points . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “World War I.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_I . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Wilsons_Fourteen_Points_–_European_Baby_Show.png.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fourteen_Points#/media/File:Wilsons_Fourteen_Points_–_European_Baby_Show.png . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- Boundless World History. Authored by : Boundless. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

The Fourteen Points in Detail

In his Fourteen Points speech, Wilson had described the terms under which America would accept a peace settlement. Wilson wanted to grant independence to lands in Europe that had been under imperial control. Wilson firmly believed that the Fourteen Points would solve the problems that had led to World War I, prevent future wars, and spread democracy across the globe. His “new world order” would serve as a contrast to Lenin’s vision of an international Communist society.

The Fourteen Points referenced free trade, open diplomacy, arms reductions, and an international organization—the League of Nations—to settle disputes without war. Over half of the points dealt with issues of national borders and national sovereignty .

Read the full transcript of Wilson’s speech to the U.S. Congress, which includes the Fourteen Points. Highlight details that reference the impact of the war and plans for a future peace. Click Highlight It to get started.

You must be signed in to save work in this lesson. Log in

Interactive Lesson Sign In

Sign in to your PBS LearningMedia account to save your progress and submit your work, or continue as a guest.

Fourteen Points

29 pages • 58 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “fourteen points”.

On January 8, 1918, toward the end of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson stood before both houses of Congress to lay out a vision for the postwar period. He proposed a plan based on “Fourteen Points,” which gave his short speech its name. Newspapers around the world quickly reprinted the speech’s core passages under that title. This guide uses the full text of the speech in the Congressional Record for the House of Representatives (Vol. 56, Part 1). The list of 14 points, which have often been published alone, composes most of the speech’s second half.

Wilson opens his speech with an explanation of why America needs to define the peace for which it is fighting. He recounts the recent peace talks at Brest-Litovsk between the enemy Central Powers (Germany and Austria) and Russia, a US ally. Wilson describes how the Russians offered reasonable and just principles for a settlement. In contrast, the Central Powers talked about liberal ideas but in practice made harsh demands to which the Russians could not submit (690).

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,400+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,900+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Wilson speculates that this discrepancy shows tension between the Central Powers’ civilian and military leaders, which may offer hope for future negotiations. He then says it is time for all participants, especially the US, to publicly state their vision for an armistice and postwar world. He condemns all attempts at making secret deals behind closed doors. He admits that Russia is militarily broken and helpless before Germany’s armies but praises its continued heroic defiance. America, Wilson proclaims, entered the war because the Central Powers violated rights and therefore must ensure that peace is made on the foundation of justice (690-91).

Wilson then moves into his proposals (691). His first five points describe principles that, if obeyed by all nations after the war, will lead to a more prosperous world that might avoid another such war. They include:

1. All international treaties and alliances should be made in full view of the public without backroom deals.

2. All nations should have freedom of navigation (the right to sail any sea without their ships being harassed or sunk).

3. There should be open trade between nations without economic barriers.

4. Militaries and stockpiles of military supplies should be reduced to the minimum needed for self-defense.

5. European and Japanese claims to rule parts of the world as colonies should be judged by a neutral party. The desires and rights of the colonial subjects need to be given as much weight as the claims of their colonial rulers.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Wilson’s next eight points address the future borders of specific territories. These points include:

6. Wilson demands that the Central Powers withdraw from occupied Russian territory. He also demands that all nations respect the freedom of Russia to rule itself under the institutions of its choosing, a veiled reference to the new communist government being formed there.

7. Belgium, which was invaded at the beginning of the war in violation of international law, must be liberated.

8. The French territories of Alsace-Lorraine, taken by Germany in 1871, must be restored to France.

9. Italy’s frontiers are to be adjusted based on ethnicity. In other words, if most people in a disputed territory speak Italian, that region should be part of Italy.

10. The people who make up the Austro-Hungarian empire should be allowed to freely develop themselves. That is, the different ethnic groups in that empire should have the right to create their own countries.

11. The Central Powers should give up the countries in the Balkans (southeastern Europe) that they had conquered, including Serbia.

12. The Turks, who rule the Ottoman Empire, can keep the country of Turkey but other ethnic groups in the empire should be able to form their own countries.

13. The Polish people should have their own country.

Wilson rounds out his list with a final point that suggests a way to enforce his earlier principles. The later League of Nations is based on this point:

14. He calls for an association of nations that can guarantee peace and protect small nations against attack.

Wilson reaffirms that America’s concern is justice. He reassures Germans that he has no hatred of them or desire to humiliate them. He is happy to embrace a peaceful Germany as an equal—all that needs to happen is for liberal German civilians to overrule the generals who desire to become the masters of other nations. America will fight so long as justice is denied but will happily make a just peace.

Wilson concludes with a rousing declaration of America’s commitment to justice and liberty for all people. He casts the war in apocalyptic tones as the “final war for human liberty” (691). The US will fight to the end to ensure that good triumphs.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Featured Collections

Books on Justice & Injustice

View Collection

Good & Evil

Politics & Government

The Fourteen Points of Woodrow Wilson's Plan for Peace

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- Ph.D., American History, Oklahoma State University

- M.A., American history, Oklahoma State University

- B.A., Journalism, Northwestern Oklahoma State University

November 11 is, of course, Veterans' Day . Originally called "Armistice Day," it marked the ending of World War I in 1918. It also marked the beginning of an ambitious foreign policy plan by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson . Known as the Fourteen Points, the plan—which ultimately failed—embodied many elements of what we today call " globalization ."

Historical Background

World War I, which began in August 1914, was the result of decades of imperial competition between the European monarchies. Great Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Turkey, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Russia all claimed territories around the globe. They also conducted elaborate espionage schemes against each other, engaged in a continuous arms race, and constructed a precarious system of military alliances .

Austria-Hungary laid claim to much of the Balkan region of Europe, including Serbia. When a Serbian rebel killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, a string of events forced the European nations to mobilize for war against each other.

The main combatants were:

- The Central Powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Turkey

- The Entente Powers: France, Great Britain, Russia

The U.S. in the War

The United States did not enter World War I until April 1917 but its list of grievances against warring Europe dated back to 1915. That year, a German submarine (or U-Boat) sank the British luxury steamer, Lusitania , which carried 128 Americans. Germany had already been violating American neutral rights; the United States, as a neutral in the war, wanted to trade with all belligerents. Germany saw any American trade with an entente power as helping their enemies. Great Britain and France also saw American trade that way, but they did not unleash submarine attacks on American shipping.

In early 1917, British intelligence intercepted a message from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman to Mexico. The message invited Mexico to join the war on the side of Germany. Once involved, Mexico was to ignite war in the American southwest that would keep U.S. troops occupied and out of Europe. Once Germany had won the European war, it would then help Mexico retrieve land it had lost to the United States in the Mexican War, 1846-48.

The so-called Zimmerman Telegram was the last straw. The United States quickly declared war against Germany and its allies.

American troops did not arrive in France in any large numbers until late 1917. However, there were enough on hand to stop a German offensive in Spring 1918. That fall, Americans led an allied offensive that flanked the German front in France, severing the German army's supply lines back to Germany.

Germany had no choice but to call for a cease-fire. The armistice went into effect at 11 a.m., on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918.

The Fourteen Points

More than anything else, Woodrow Wilson saw himself as a diplomat. He had already roughed out the concept of the Fourteen Points to Congress and the American people months before the armistice.

The summarized Fourteen Points included:

- Open covenants of peace and transparent diplomacy.

- Absolute freedom of the seas.

- The removal of economic and trade barriers.

- An end to arms races.

- National self-determination to figure in adjustment of colonial claims.

- Evacuation of all Russian territory.

- Evacuation and restoration of Belgium.

- All French territory restored.

- Italian frontiers adjusted.

- Austria-Hungary given "opportunity to autonomous development."

- Rumania, Serbia, Montenegro evacuated and given independence.

- Turkish portion of the Ottoman Empire should become sovereign; nations under Turkish rule should become autonomous; Dardanelles should be open to all.

- Independent Poland with access to the sea should be created.

- A "general association of nations" should be formed to guarantee political independence and territorial integrity to "great and small states alike."

Points one through five attempted to eliminate the immediate causes of the war : imperialism, trade restrictions, arms races, secret treaties, and disregard of nationalist tendencies. Points six through 13 attempted to restore territories occupied during the war and set post-war boundaries, also based on national self-determination. In the 14th Point, Wilson envisioned a global organization to protect states and prevent future wars.

The Treaty of Versailles

The Fourteen Points served as the foundation for the Versailles Peace Conference that began outside of Paris in 1919. However, the Treaty of Versailles was markedly different than Wilson's proposal.

France—which had been attacked by Germany in 1871 and was the site of most of the fighting in World War I—wanted to punish Germany in the treaty. While Great Britain and the United States did not agree with punitive measures, France won out.

The resultant treaty:

- Forced Germany to sign a "war guilt" clause and accept full responsibility for the war.

- Prohibited further alliances between Germany and Austria.

- Created a demilitarized zone between France and Germany.

- Made Germany responsible for paying millions of dollars in reparations to the victors.

- Limited Germany to a defensive army only, with no tanks.

- Limited Germany's navy to six capital ships and no submarines.

- Prohibited Germany from having an air force.

The victors at Versailles did accept the idea of Point 14, a League of Nations . Once created, it became the issuer of "mandates" which were former German territories handed over to allied nations for administration.

While Wilson won the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize for his Fourteen Points, he was disappointed by the punitive atmosphere of Versailles. He was also unable to convince Americans to join the League of Nations. Most Americans—in an isolationist mood after the war—did not want any part of a global organization which could lead them into another war.

Wilson campaigned throughout the U.S. trying to convince Americans to accept the League of Nations. They never did, and the League limped toward World War II with U.S. support. Wilson suffered a series of strokes while campaigning for the League, and was debilitated for the rest of his presidency in 1921.

- World War I: The Fourteen Points

- The Treaty of Versailles: An Overview

- Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points

- The US and Great Britain's Special Relationship

- Biography of Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States

- 10 Things to Know About Woodrow Wilson

- A Guide to Woodrow Wilson's 14 Points Speech

- The Major Alliances of World War I

- Causes of World War I and the Rise of Germany

- Causes of World War II

- The Controversial Versailles Treaty Ended World War I

- World War 1: A Short Timeline 1919-20

- The Causes and War Aims of World War One

- World War 1: A Short Timeline Pre-1914

- The Consequences of World War I

- World War I's Mitteleuropa

Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, 1918

Use this primary source text to explore key historical events.

Suggested Sequencing

- Use this Primary Source with America Enters World War I Narrative to further analyze President Wilson’s vision for the end of World War I.

Introduction

President Woodrow Wilson wrote the Fourteen Points as a program to preserve peace after World War I. Wilson first presented the Fourteen Points in a speech to Congress on January 8, 1918, in what would be the final year of the war. Wilson hoped the end of the war would be an opportunity to not only establish a peace treaty but also create a just and cooperative international order to prevent future wars in Europe and the rest of the world. American allies viewed the Fourteen Points positively and even the Central Powers began to see it as a reasonable basis for peace when they realized the war was unwinnable. Although all sides initially supported the ideas presented in the Fourteen Points, demands for German reparations and other punishments made the idealism of the Fourteen Points difficult to implement at the Peace of Paris.

Sourcing Questions

- Who wrote this document? What is his relationship to the peace of World War I?

- When was this speech delivered? Consider the specific date but also the larger historical context and surrounding events.

- Who is the author’s intended audience? How might this influence what he says?

- What is the author’s purpose for writing the document?

Comprehension Questions

- What diplomatic or military restrictions did Wilson call for?

- What economic recommendations did Wilson make to ensure international peace?

- How should colonial questions be resolved in the future?

- What countries had territory that was occupied or conquered by Germany during the war?

- What recommendation did Wilson make for German-occupied territory once the war was over?

- According to this part of the Fourteen Points, what countries should be established or have territorial changes?

- What was meant by autonomous development and political and economic independence for these territories?

- How should nationality influence the creation and borders of countries?

- What was the purpose of forming a “general association of nations?”

Historical Reasoning Questions

- Explain how Wilson’s Fourteen Points respond to the major causes of World War I.

- Explain how Wilson’s Fourteen Points attempt to secure a lasting international peace.

President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/wilson14.asp

- Service and Contact

Secondary menu

- About the project

- Publications

- Reading room

Persons, Objects & Events

Developments, story the end of the war.

- A programme for world peace – President Wilson’s Fourteen Points

Präsident Thomas Woodrow Wilson, portrait photograph, 1918 Copyright: IMAGNO/Austrian Archives

Title page of the Freie Presse of 10 January 1918 with the report on Wilson's speech and the 14 points. Copyright: ÖNB/ANNO Partner: Austrian National Library

On 8 January 1918, Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924), who had been President of the USA since 1913, held a programmatic speech before both houses of Congress in which he interpreted the war as a moral struggle for democracy and staked out the cornerstones for post-war Europe.

Wilson demanded a new basis for international relations: there was to be no more secret diplomacy and the peace should be negotiated ‘frankly and in the public view’. Another point concerned the establishment of a ‘general association of nations’ as a platform to afford ‘guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike’. In 1920 this led to the foundation of the League of Nations, the forerunner of the United Nations, for which Wilson was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Wilson’s programme also contained a number of demands concerned with trade politics such as ‘absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters’ and the ‘the removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers’ in international trade relations. And in a further point he made reference to a ‘free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims’.

In addition to these demands, which were somewhat vaguely formulated and intended principally as food for thought and debate, Wilson’s famous ‘Fourteen Points’ speech also contained concrete demands for a new European order. Germany was to re-establish Belgium as an independent state and return Alsace-Lorraine to France. The Russian areas under German occupation were to be evacuated and given the freedom to determine their own political development. Furthermore, the new order after the conclusion of peace was to include the establishment of an independent Polish state and provide for stability in the Balkans and the Ottoman Empire.

With respect to the Habsburg Monarchy, Wilson demanded that the border to Italy be redrawn in accordance with the language spoken on either side (‘along clearly recognizable lines of nationality’). Particularly significant was the fact that Wilson supported the demand of the peoples of Austria-Hungary for guarantees of ‘the freest opportunity to autonomous development.’

The reactions were divided. The USA’s European allies were sceptical about the demands, which in their opinion were too idealistic. As from the German point of view Wilson’s demands seemed quite acceptable, Berlin interpreted the programme as a basic set of conditions for German capitulation. When the negotiations in the treaties of 1919/20 concluded in the suburbs of Paris finally led to results differing significantly from Wilson’s demands, the Germans considered that their trust had been abused and made extremely distorted claims concerning Wilson’s original intentions.

Vienna likewise considered Wilson’s plan for the post-war world an acceptable one. In particular, his concern for the continued existence of the Dual Monarchy was regarded as offering a glimmer of hope, for according to Wilson the multi-national state was in principle to remain in place, even though the individual nationalities were to be guaranteed the greatest possible autonomy.

In May 1918, however, the USA underwent a fundamental change of attitude. As Austria-Hungary was not willing to revoke its alliance with Germany, there was no longer any taboo on dismembering the Habsburg Monarchy and the establishment of nation-states in Central Europe now became the general aim of the Entente in the new ordering of post-war Europe.

This was the final death blow for the Monarchy, because Wilson’s call for the Central European nationalities to be accorded ‘the freest opportunity to autonomous development’ was now understood by their political leaders as a call for national liberation. The campaigns for independence being waged by the non-German and non-Magyar ethnic groups acquired new impetus and the anti-Austrian line gained the upper hand in public opinion.

Even though the noble principle of the ‘self-determination of the nations’ was hardly applicable to central and south-eastern Europe, because there were large areas inhabited by two or more different ethnic groups, the new catchword thus became the guiding principle for the creation of the new territorial order.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

- Martin Mutschlechner

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

- The course of the war 1917–1918: Face-to-face with imminent downfall

- The situation in the hinterland

- Apathy and resistance – The mood of the people

- The Sixtus Affair: A major diplomatic débacle

- ‘To My faithful Austrian peoples’ – Emperor Karl’s manifesto

- The collapse

- The disintegration of the Habsburg Monarchy – Part I: On the road to self-determination

- The disintegration of the Habsburg Monarchy – Part II: The situation in Vienna and Budapest

- The last days of the Monarchy

Contents related to this chapter

The longer the war lasted, the more disagreement was voiced by representatives of the Austrian peace and women’s movements and also by sections of the Austro‑Hungarian population. They became increasingly tired of the war, reflected in strikes and hunger riots and in mass desertions by front soldiers towards the end of the war.

Thomas Woodrow Wilson

Wilson was the President of the USA during the First World War. His “Fourteen points” of 1918 were decisive for the restructuring of Europe after the end of the war.

Peace message by US President Wilson (“14 points”)

The Paris peace treaties: post-war restructuring of Europe

National attitudes to the war

The Habsburg Monarchy as a state framework for the smaller nationalities of Central Europe was not seriously questioned before 1914, either internally or externally. With the outbreak of war, representatives of the nationalities initially emphasised their loyalty to the Monarchy’s war aims.

Memoirs from the left papers of Johann Obermüllner

War memoirs from the left papers of Anton Hanausek

War notebook from the left papers of Johann Tanzer

This website uses cookies.

We employ strictly necessary and analysis cookies. Analysis cookies are used only with your consent and exclusively for statistical purposes. Details on the individual cookies can be found under “Cookie settings”. You can also find further information in our data protection declaration.

Cookie settings Accept all cookies

Cookie settings

Here you can view or change the cookie settings used on this domain.

Cookies are a technical feature necessary for the basic functions of the website. You can block or delete these cookies in your browser settings, but in doing so you risk the danger of preventing several parts of the website from functioning properly. The information contained in the cookies is not used to identify you personally. These cookies are never used for purposes other than specified here.

We employ analysis cookies to continually improve and update our websites and services for you. The following analysis cookies are used only with your consent.

Save settings Accept all cookies

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Lesson 4: Fighting for Peace: The Fate of Wilson's Fourteen Points

In the aftermath of the First World War, Woodrow Wilson tried to push a comprehensive and enlightened peace plan.

Wikimedia Commons

In January 1918, less than one year after the United States entered World War I, President Woodrow Wilson announced his Fourteen Points to try to ensure permanent peace and to make the world safe for democracy. Wilson's aims included freedom of the seas, free trade, and, most important, an international organization dedicated to collective security and the spreading of democracy. The other Allied powers tacitly and cautiously accepted Wilson's plan as a template for a postwar treaty; however, numerous obstacles lay in the path of the Fourteen Points at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Wilson reluctantly made several concessions, yet he successfully protected the Fourteenth Point, the League of Nations, which was written into the Versailles Treaty. After enduring months of bruising, frustrating negotiations, Wilson finally returned to the United States. Despite obvious Senate reservations about the League of Nations, Wilson was certain the Versailles Treaty would be ratified. He was wrong.

Through the use of primary source documents and maps, this lesson will introduce students to Wilson's Fourteen Points, as well as his efforts to have them incorporated into the final peace treaties.

Guiding Questions

Did the Versailles Treaty represent the fulfillment of Wilson's Fourteen Points, or their betrayal?

Learning Objectives

Discuss how the Fourteen Points, especially the League of Nations, demonstrated Wilsonian principles

Summarize the aims of the other Allied powers at the Paris Peace Conference

Identify which of the Fourteen Points became part of the final peace settlement

Lesson Plan Details

In January 1918, Woodrow Wilson unveiled his Fourteen Points to the U.S. Congress. The speech was a natural extension of the proposals he had offered in his " Peace without Victory " address and his request for a declaration of war. Presuming an Allied victory, the President proposed freedom of the seas and of trade, arms reductions, and fair settlement of colonial claims and possessions. He insisted that "open covenants of peace, openly arrived at," must be the benchmark of postwar negotiations. He suggested that a repentant and reformed Germany would not be oppressed, but rather welcomed into the international community. That community, Wilson concluded, would be bound together in a league of nations devoted to collective security and spreading democracy.

Although the Allied powers cautiously agreed to use the Fourteen Points as a treaty template, the circumstances of the war and the specific postwar aims of numerous nations combined to make a formidable obstacle. In 1915, the secret London agreements had proposed ceding the German territory of the Saar (rich in coal) to France, and South Tyrol, controlled by Austria-Hungary, to Italy. Japan hoped to take German claims in the North Pacific and China, while Great Britain hoped to secure claims in Africa and south of the equator in the Pacific.

By the war's end, in November 1918, these tensions had mounted. France and Great Britain both wanted Germany to pay extensive war reparations. Great Britain, with an eye toward protecting its far-flung empire, also resisted freedom of the seas. Wilson hammered out a compromise. Together, the Allies would precisely define "freedom of the seas," and Germany would have to pay some reparations. Meanwhile domestic political tensions were rising. In the midterm elections, Republicans gained control of Congress. Nevertheless, Wilson opted only for token Republican representation on the U.S. delegation headed to Paris, the site of the postwar peace proceedings, which began in January 1919. This snub did not pass unnoticed by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Mass.), who now chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

The proceedings were raucous and confusing. Wilson, who had rejected advice that he might better fulfill his Fourteen Points by remaining in Washington, immersed himself in the day-to-day negotiations. His greatest challenge was the spirit of vengeance that animated the other Allied leaders. Not only did they want to punish Germany, they also wanted to use victory to obtain new territory in Europe and to divvy up Germany's colonial possessions. Wilson struggled to balance pragmatism and idealism. On the colonial question, he agreed to substitute the "mandate system" for full and fair self-determination. Under this system, the Allied powers assumed governing control over the colonies of Germany and areas such as Syria and Lebanon that had belonged to the Ottoman Empire. The expectation was that the Allied powers would eventually free their "mandates." He also accepted the transfer of some one million square miles of territory between nations; in return, the covenant of the League of Nations was embedded into the Versailles Treaty.

In June 1919, Germany's defiant representatives, who had been excluded from the proceedings, grudgingly signed the Versailles Treaty. Wilson's decision to now present the Versailles Treaty to the Senate as a fait accompli was quite risky. Republican doubts about the League had hardened; indeed, a group of Senators known as the "Irreconcilables," led by William Borah of Idaho, had proclaimed they would not support American membership in the League. Much opposition resulted from Article Ten of the League's covenant, which committed nations to the protection of the territorial integrity of all other members. This seemed to undermine Congressional authority to declare war, though the precise obligations of the United States were not clear. Lodge and the "Reservationists" were, at least initially, ready to act on the Versailles Treaty if Wilson separated the covenant. They also seemed willing to accept U.S. membership provided Congress kept the power to decide whether or not the United States would intervene militarily on behalf of the League. But Wilson refused to yield, as did Lodge and his allies. The debate over the League spilled over onto the 1920 presidential campaign, and while the election of Republican Warren G. Harding, who declared his opposition to the League, cannot be assessed only as a referendum on Wilsonian diplomacy, it was clear that the American public had grown weary of crusades, domestic and international. The United States never joined the League, finally ending the official state of war with Germany in the summer of 1921 through the Treaty of Berlin .

For an overview of the League of Nations and the Versailles Treaty, visit From Revolution to Reconstruction . For another EDSITEment lesson plan on this subject, see The Debate in the United States over the League of Nations: League of Nations Basics .

- This lesson may be used in sequence with the other plans in this unit on Wilsonian foreign policy, or it may be used in conjunction with the lessons in the EDSITEment curriculum unit The Debate in the United States over the League of Nations . While this lesson concentrates on Wilson's Fourteen Points, the Paris Peace Proceedings, and the Versailles Treaty, the other lessons focus on domestic political and public reaction to the League of Nations. See The Great War: Evaluating the Treaty of Versailles .