MBA Knowledge Base

Business • Management • Technology

Home » Management Case Studies » Case Study: Euro Disney Failure – Failed Americanism?

Case Study: Euro Disney Failure – Failed Americanism?

Many of Businesses in America make detailed assumptions about the potential of expand their business to other countries and structural models of organizing which can be easily failed to consider the cultural differences. One of the examples of the outcome to intercultural business is Disney Corporation’s European venture. Due to lack of cultural information of France as well as Europe, further on their inability to forecast problems, Disney acquired a huge debt. False assumptions led to a great loss of time, money and even reputation for corporation itself. Instead of analyzing and learning from its potential visitors, Disney chose to make assumptions about the preference of Europeans, which turned out that most of those assumptions were wrong.

Euro Disney Disaster

Until 1992, the Walt Disney Company had experienced nothing but success in the theme park business. Its first park, Disneyland, opened in Anaheim, California, in 1955. Its theme song, “It’s a Small World After All,” promoted an idealized vision of America spiced with reassuring glimpses of exotic cultures all calculated to promote heartwarming feelings about living together as one happy family. There were dark tunnels and bumpy rides to scare the children a little but none of the terrors of the real world . . . The Disney characters that everyone knew from the cartoons and comic books were on hand to shepherd the guests and to direct them to the Mickey Mouse watches and Little Mermaid records. The Anaheim park was an instant success.

In the 1970s, the triumph was repeated in Florida, and in 1983, Disney proved the Japanese also have an affinity for Mickey Mouse with the successful opening of Tokyo Disneyland. Having wooed the Japanese, Disney executives in 1986 turned their attention to France and, more specifically, to Paris, the self-proclaimed capital of European high culture and style. “Why did they pick France?” many asked. When word first got out that Disney wanted to build another international theme park, officials from more than 200 locations all over the world descended on Disney with pleas and cash inducements to work the Disney magic in their hometowns. But Paris was chosen because of demographics and subsidies. About 17 million Europeans live less than a two-hour drive from Paris. Another 310 million can fly there in the same time or less. Also, the French government was so eager to attract Disney that it offered the company more than $1 billion in various incentives, all in the expectation that the project would create 30,000 French jobs. From the beginning, cultural gaffes by Disney set the tone for the project. By late 1986, Disney was deep in negotiations with the French government. To the exasperation of the Disney team, headed by Joe Shapiro, the talks were taking far longer than expected. Jean-Rene Bernard, the chief French negotiator, said he was astonished when Mr. Shapiro, his patience depleted, ran to the door of the room and, in a very un-Gallic gesture, began kicking it repeatedly, shouting, “Get me something to break!” There was also snipping from Parisian intellectuals who attacked the transplantation of Disney’s dream world as an assault on French culture; “a cultural Chernobyl,” one prominent intellectual called it. The minister of culture announced he would boycott the opening, proclaiming it to be an unwelcome symbol of American cliches and a consumer society.

Unperturbed, Disney pushed ahead with the planned summer 1992 opening of the $5 billion park. Shortly after Euro-Disneyland opened, French farmers drove their tractors to the entrance and blocked it. This globally televised act of protest was aimed not at Disney but at the US government, which had been demanding that French agricultural subsidies be cut. Still, it focused world attention upon the loveless marriage of Disney and Paris. Then there were the operational errors. Disney’s policy of serving no alcohol in the park, since reversed caused astonishment in a country where a glass of wine for lunch is a given. Disney thought that Monday would be a light day for visitors and Friday a heavy one and allocated staff accordingly, but the reality was the reverse. Another unpleasant surprise was the hotel breakfast debacle. “We were told that Europeans ‘don’t take breakfast,’ so we downsized the restaurants,” recalled one Disney executive. “And guess what? Everybody showed up for breakfast. We were trying to serve 2,500 breakfasts in a 350-seat restaurant at some of the hotels. The lines were horrendous. Moreover, they didn’t want the typical French breakfast of croissants and coffee, which was our assumption. They wanted bacon and eggs.” Lunch turned out to be another problem. “Everybody wanted lunch at 12:30. The crowds were huge. Our smiling cast members had to calm down surly patrons and engage in some ‘behavior modification’ to teach them that they could eat lunch at 11:00 AM or 2:00 PM.” There were major staffing problems too. Disney tried to use the same teamwork model with its staff that had worked so well in America and Japan, but it ran into trouble in France. In the first nine weeks of Euro-Disneyland’s operation, roughly 1,000 employees, 10 percent of the total, left. One former employee was a 22-year old medical student from a nearby town who signed up for a weekend job. After two days of “brainwashing,” as he called Disney’s training, he left following a dispute with his supervisor over the timing of his lunch hour. Another former employee noted, “I don’t think that they realize what Europeans are like . . . that we ask questions and don’t think all the same way.”

One of the biggest problems, however, was that Europeans didn’t stay at the park as long as Disney expected. While Disney succeeded in getting close to 9 million visitors a year through the park gates, in line with its plans, most stayed only a day or two. Few stayed the four to five days that Disney had hoped for. It seems that most Europeans regard theme parks as places for day excursions. A theme park is just not seen as a destination for an extended vacation. This was a big shock for Disney. The company had invested billions in building luxury hotels next to the park-hotels that the day-trippers didn’t need and that stood half empty most of the time. To make matters worse, the French didn’t show up in the expected numbers. In 1994, only 40 percent of the park’s visitors were French. One puzzled executive noted that many visitors were Americans living in Europe or, stranger still, Japanese on a European vacation! As a result, by the end of 1994 Euro-Disneyland had cumulative losses of $2 billion.

At this point, Euro-Disney changed its strategy. First, the company changed the name to Disneyland Paris in an attempt to strengthen the park’s identity. Second, food and fashion offerings changed. To quote one manager, “We opened with restaurants providing French-style food service, but we found that customers wanted self service like in the US parks. Similarly, products in the boutiques were initially toned down for the French market, but since then the range has changed to give it a more definite Disney image.” Third, the prices for day tickets and hotel rooms were cut by one-third. The result was an attendance of 11.7 million in 1996, up from a low of 8.8 million in 1994.

Read More: The Not So Wonderful World of Euro Disney

The Three Mistakes

In determining the target market did not take into account cultural differences Euro Disney’s choice of location focus on the aspects of financial and population, then Euro Disney theme park located in the populous central Europe. Disney executives did not see that Mickey Mouse and intellectuals in the region of the left bank of the Seine in Paris can not live in harmony and France is serious about their intellectual. In retrospect, Paris is not the best place to establish such a theme park, so the establishment of the Disney parks is a declaration of war to intellectuals of French. Disney’s manager stated publicly some of the criticism is “the nonsense of a small number of business” would not help them a favor. This may can be well operated according to American culture, while the French pay more attention to their own cultural elite and regard this refute as attack of national quality.

Having not adequately take into account the habits of the French when arrange the service kinds Disney do not provide breakfast because they think that the Europeans do not eat breakfast. In addition, the Disney company does not provide alcoholic beverages within the park, but the French habits are different, they are used to drinking a cup while taking lunch, which aroused the anger of the French. Disney executives did not estimate that the European are not interested in vacation in theme park so much, in the attitude of Disney Company the European will be happy about spending a few days in a theme park like the American and Japanese, but middle-class in Europe just want to “get away from everything around” and go to the coast or the mountains, and Euro Disney is the lack of such appeal.

No combination of French culture to the local staff management Disney has taken global standard model as same as the Japanese business, they transplanted the American culture to France directly then doing this result with a serious clash of cultures. The Disney Company use many measures that departed with the local culture, for example, in the Euro Disney, the France worker are requested to comply with the strict appearance code as the other theme parks in United States and Japan do, the workers are asked to break their ancient cultural aversions to smiling and being consistently polite to the park guest even must mirror the multi-country makeup of its guest. In addition, the Disney Company brought their U.S. Pop culture to France and fought hard for a greater “local cultural context”. The French people think that this is an attack on their native culture, so they adopted an unfriendly attitude toward to the arrival of the Disney, including the protest come from the intellectual and the local residence and farmers.

The Three Lessons

Multinational companies should target market accurately even in the same country or regional market, the traditional culture makes different control power to different people. Multinational companies should be fully based on detailed market research to find the weak links in the market and make a breakthrough, use the “point to an area” model to expand. For example, McDonald’s opened in the Chinese market, its target is no longer work for the busy working-class, but the children. The golden arches mark, the joy atmosphere of the shop, the furnished toys, full of playful ads, as well as various promotional activities specifically carry out for children, these have a tremendous appeal to the target customers. McDonald think that adult eating habits difficult to change, only those children whose taste not yet formed are the potential customers of Western fast food culture, the McDonald received Broad market recognition and have huge market potential.

Multinational enterprises should pay full attention to the importance of the influence of cultural differences on marketing face to the new multiple culture environment, the multinational enterprise should take an objective acknowledge about the cultural differences of the consumer demand and behavior and respect it, abandoning the prejudice and discrimination of culture completely. Moreover, multinational enterprises should be good at finding out and using the base point of communication and collaboration of different cultures and regard this base point as the important consideration factor when plan to enter the target country market. After all, the fundamental criterion for a successful business enterprise is whether it can integrate into the local social and cultural environment. The multinational enterprises should improve the sensitivity and adaptability to the different culture environment.

Multinational enterprises should make full use of the competitive advantages of cultural differences and promote international marketing. The objective of international cultural differences can also be the basic demand points of different competitive strategy . In the international market, launching culture marketing activities and highlighting the exotic culture and cultural differences in the target market can open the market quickly. Companies should strive to build cross-cultural “two-way” communication channels, it is necessary to adapt to the host’s cultural environment and values and carry out the business strategy of localization to make it can be widely accepted by the host country local government, local partners, consumers and other relevant stakeholders. Effective cross-cultural communication on the one hand contribute to cultural integration, but also can create a harmonious internal and external human environment for corporate management.

Related posts:

- Case Study: Why Did Euro Disney Fail?

- Case Study of Euro Disney: Managing Marketing Environmental Challenges

- Case Study: Why Woolworths Failed as a Business?

- Case Study: Why Walmart Failed in Germany?

- Case Study: Disney’s Diversification Strategy

- Case Study: Walt Disney’s Business Strategies

- Case Study: Failure of Vodafone in Japan

- Case Study of Nike: The Cost of a Failed ERP Implementation

- Case Study: Sony’s Business Strategy and It’s Failure

- Case Study: Marketing Strategy of Walt Disney Company

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Brought to you by:

Euro Disney or Euro Disaster?

By: Goir Sheikholeslami, Leslie Grayson, Kunihiko Amano, Thomas Falk, Virginia Kleinclaus

Concerns the troubles that Euro Disney experienced from the start. Euro Disney claimed that the major cause of its poor financial performance was the European recession and the strong French franc.…

- Length: 11 page(s)

- Publication Date: Oct 31, 1994

- Discipline: General Management

- Product #: UV0020-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

Concerns the troubles that Euro Disney experienced from the start. Euro Disney claimed that the major cause of its poor financial performance was the European recession and the strong French franc. The timing of the park's opening could not have been more inopportune. If the recession had been the only cause of Euro Disney's problems, the financial restructuring would only need to carry the park forward to better economic times. Only when Europeans began spending freely again would investors learn the answers to some uncomfortable questions: Was the whole idea of Euro Disney misconceived? Were there other fundamental cultural problems that could inhibit the park's success? Would Euro Disney fail to recover even though other European companies did? And, if so, why was the Disney theme park concept successful in Japan and not in France?

Learning Objectives

To decide what factors played a role in the poor performance of Euro Disney.

Oct 31, 1994 (Revised: Sep 1, 1995)

Discipline:

General Management

Geographies:

Industries:

Amusement and theme parks

Darden School of Business

UV0020-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- August 1992 (Revised June 1993)

- HBS Case Collection

Euro Disney: The First 100 Days

- Format: Print

- | Language: English

- | Pages: 23

About The Author

Leonard A. Schlesinger

More from the authors.

- Faculty Research

The Meteoric Rise of Skims

- May–June 2024

- Harvard Business Review

What Makes a Successful Celebrity Brand?

Growing as a purposeful leader (gpl).

- The Meteoric Rise of Skims By: Ayelet Israeli, Jill Avery and Leonard A. Schlesinger

- What Makes a Successful Celebrity Brand? By: Ayelet Israeli, Jill Avery, Leonard A. Schlesinger and Matt Higgins

- Growing as a Purposeful Leader (GPL) By: Hubert Joly and Leonard A. Schlesinger

- < Previous

Home > Law > Faculty Scholarship > 7

Law Faculty Scholarship

Mickey goes to france: a case study of the euro disneyland negotiations.

Lauren A. Newell , Ohio Northern University Follow

Document Type

Recommended citation.

Lauren A. Newell, Mickey Goes to France: A Case Study of the Euro Disneyland Negotiations, 15 Cardozo J. Conflict Resol. 193 (2013).

Euro Disneyland (since renamed Disneyland Resort Paris) in Marne-la-Vallée, France was declared a success even before it was built, and yet it narrowly escaped a humiliating bankruptcy after opening. This article applies intercultural negotiation theory to examine how The Walt Disney Company proved fallible in its negotiations with the French government and citizens in the course of constructing and operating Euro Disneyland.

Through a case study of the negotiations, this article reveals why the reality proved so different from the expectations. It concludes with advice for how The Walt Disney Company — and, by implication, any multinational firm — should approach international deal-making in the future to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Publication Date

Since January 18, 2019

Included in

Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons , International Law Commons

- Collections

- Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Author Corner

- Submit Research

- Pettit College of Law Faculty

- Privacy Statement

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, euro disney or euro disaster.

Publication date: 20 January 2017

Teaching notes

This case concerns the troubles that Euro Disney experienced from the start. Euro Disney claimed that the major cause of its poor financial performance was the European recession and the strong French franc. The timing of the park's opening could not have been more inopportune. If the recession had been the only cause of Euro Disney's problems, the financial restructuring would only need to carry the park forward to better economic times. Only when Europeans began spending freely again would investors learn the answers to some uncomfortable questions: Was the whole idea of Euro Disney misconceived? Were there other fundamental cultural problems that could inhibit the park's success? Would Euro Disney fail to recover even though other European companies did? And, if so, why was the Disney theme-park concept successful in Japan and not in France?

- Capital structure

- International case

- Diversity case

- International

- Cross-cultural behavior

Grayson, L.E. and Sheikholeslami, G. (2017), "Euro Disney or Euro Disaster?", . https://doi.org/10.1108/case.darden.2016.000110

University of Virginia Darden School Foundation

Copyright © 1994 by the University of Virginia Darden School Foundation, Charlottesville, VA. All rights reserved.

You do not currently have access to these teaching notes. Teaching notes are available for teaching faculty at subscribing institutions. Teaching notes accompany case studies with suggested learning objectives, classroom methods and potential assignment questions. They support dynamic classroom discussion to help develop student's analytical skills.

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Product details

- BINUS UNIVERSITY

- About International Business Management Program

- Faculty Profile

- Faculty Research and Publication

- Accreditation

- Student Achievements

- Alumni Testimonials

- Partnership

- Course Structure – Binusian 2027 Reg Class

- Course Structure – Binusian 2026 Reg Class

- Course Structure – Binusian 2027 Global Class

- Course Structure – Binusian 2026 Global Class

- DATA ANALYTICS

- DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM

- DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION

- INTERACTIVE & USERS EXPERIENCE DESIGN

- METAVERSE IN BUSINESS

- ROBOTIC PROCESS AUTOMATION

- SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

- VIRTUAL SERVICES EXPERIENCE

- Mobility Program

- Enrichment Program

- Articles & Knowledge

- Panduan Proposal Skripsi Semester Ganjil 2023-2024

- Admission Schedule

- Entry Requirements

- Tuition Fee

- Scholarships

Case Study Disney in France for Cross Culture Management

Until 1992, the Walt Disney Company had experienced nothing but success in the theme park business. Its first park, Disneyland, opened in Anaheim, California, in 1955. Its theme song, It’s a Small World After All, promoted an idealized vision of America spiced with reassuring glimpses of exotic cultures all calculated to promote heartwarming feelings about living together as one happy family. There were dark tunnels and bumpy rides to scare the children a little but none of the terrors of the real world. The Disney characters that everyone knew from the cartoons and comic books were on hand to shepherd the guests and to direct them to the Mickey Mouse watches and Little Mermaid records. The Anaheim park was an instant success.

In the 1970s, the triumph was repeated in Florida, and in 1983, Disney proved the Japanese also have an affinity for Mickey Mouse with the successful opening of Tokyo Disneyland. Having wooed the Japanese, Disney executives in 1986 turned their attention to France and, more specifically, to Paris, the self-proclaimed capital of European high culture and style. “Why did they pick France?” many asked. When word first got out that Disney wanted to build another international theme park, officials from more than 200 locations all over the world descended on Disney with pleas and cash inducements to work the Disney magic in their hometowns. But Paris was chosen because of demographics and subsidies. About 17 million Europeans live less than a two-hour drive from Paris. Another 310 million can fly there in the same time or less. Also, the French government was so eager to attract Disney that it offered the company more than $1 billion in various incentives, all in the expectation that the project would create 30,000 French jobs.

From the beginning, cultural gaffes by Disney set the tone for the project. By late 1986, Disney was deep in negotiations with the French government. To the exasperation of the Disney team, headed by Joe Shapiro, the talks were taking far longer than expected. Jean-Rene Bernard, the chief French negotiator, said he was astonished when Mr. Shapiro, his patience depleted, ran to the door of the room and, in a very un-Gallic gesture, began kicking it repeatedly, shouting, “Get me something to break!”

There was also snipping from Parisian intellectuals who attacked the transplantation of Disney’s dream world as an assault on French culture; “a cultural Chernobyl,” one prominent intellectual called it. The minister of culture announced he would boycott the opening, proclaiming it to be an unwelcome symbol of American clichés and a consumer society. Unperturbed, Disney pushed ahead with the planned summer 1992 opening of the $5 billion park. Shortly after Euro-Disneyland opened, French farmers drove their tractors to the entrance and blocked it. This globally televised act of protest was aimed not at Disney but at the US government, which had been demanding that French agricultural subsidies be cut. Still, it focused world attention upon the loveless marriage of Disney and Paris.

Then there were the operational errors. Disney’s policy of serving no alcohol in the park, since reversed caused astonishment in a country where a glass of wine for lunch is a given. Disney thought that Monday would be a light day for visitors and Friday a heavy one and allocated staff accordingly, but the reality was the reverse. Another unpleasant surprise was the hotel breakfast debacle. “We were told that Europeans ‘don’t take breakfast,’ so we downsized the restaurants,” recalled one Disney executive. “And guess what? Everybody showed up for breakfast. We were trying to serve 2,500 breakfasts in a 350-seat restaurant at some of the hotels. The lines were horrendous. Moreover, they didn’t want the typical French breakfast of croissants and coffee, which was our assumption. They wanted bacon and eggs.” Lunch turned out to be another problem. “Everybody wanted lunch at 12:30. The crowds were huge. Our smiling cast members had to calm down surly patrons and engage in some ‘behavior modification’ to teach them that they could eat lunch at 11:00 AM or 2:00 PM.”

There were major staffing problems too. Disney tried to use the same teamwork model with its staff that had worked so well in America and Japan, but it ran into trouble in France. In the first nine weeks of Euro-Disneyland’s operation, roughly 1,000 employees, 10 percent of the total, left. One former employee was a 22-year-old medical student from a nearby town who signed up for a weekend job. After two days of “brainwashing,” as he called Disney’s training, he left following a dispute with his supervisor over the timing of his lunch hour. Another former employee noted, “I don’t think that they realize what Europeans are like… that we ask questions and don’t think all the same way.”

One of the biggest problems, however, was that Europeans didn’t stay at the park as long as Disney expected. While Disney succeeded in getting close to 9 million visitors a year through the park gates, in line with its plans, most stayed only a day or two. Few stayed the four to five days that Disney had hoped for. It seems that most Europeans regard theme parks as places for day excursions. A theme park is just not seen as a destination for an extended vacation. This was a big shock for Disney. The company had invested billions in building luxury hotels next to the park-hotels that the day-trippers didn’t need and that stood half empty most of the time. To make matters worse, the French didn’t show up in the expected numbers. In 1994, only 40 percent of the park’s visitors were French. One puzzled executive noted that many visitors were Americans living in Europe or, stranger still, Japanese on a European vacation! As a result, by the end of 1994 Euro-Disneyland had cumulative losses of $2 billion.

At this point, Euro-Disney changed its strategy. First, the company changed the name to Disneyland Paris in an attempt to strengthen the park’s identity. Second, food and fashion offerings changed. To quote one manager, “We opened with restaurants providing Frenchstyle food service, but we found that customers wanted self-service like in the US parks. Similarly, products in the boutiques were initially toned down for the French market, but since then the range has changed to give it a more definite Disney image.” Third, the prices for day tickets and hotel rooms were cut by one-third. The result was an attendance of 11.7 million in 1996, up from a low of 8.8 million in 1994.

Many mistakes have been made in the realization of the Euro Disney entertainment park in France. They literally transplanted US culture in France without taking into consideration the cultural clash that this might have caused. US imposed their culture over the French one, and this was seen as an attack to French traditions and customs, resulting in protests from local residence and farmers.

First of all, there was a general misunderstanding of the French culture both under the lifestyle and legal aspects. The top management made wrong assumptions, which led them to take wrong management decisions. In fact, French habits and traditions were not taken in to account. For example, breakfast at the park was not served; instead in the French culture breakfast is one of the most important “moments” of the day. Moreover, alcoholic drinks were not allowed in the park: contrary French always have a glass of wine during their main meals. In addition, also the dress code requirements did not meet the French standards in work environments. And the fact that they were supposed to be always smiling and kind did not reflect the French attitude and the staff was not comfortable with these policies. Furthermore, the top management positions were al given to American, which made the situation even worse because they were incapable to fix the mistakes made from the very start. Instead, if they had hired French people to manage the park, they would have been able to assess these cultural differences in a more efficient way, avoiding such a cultural clash.

Second, it was given for granted that French entertainment culture was as the US one. Thus, staff and resources were allocated in the wrong way, because the peek days were not the same as the US Disney Land. This led to a lack of staff in crowded days and a surplus of staff in empty days affecting efficiency and profitability of the park negatively. Moreover, they assumes French would have gone to the park with their private transportation, thus they built many car parks which were most of the time empty, instead the parking were not big enough for buses, which was the more used transport used to get to the park.

Third, recession signs were not taken into consideration and too high expectations were placed in the profitability of this new Euro Disney. Thus, too high revenue expectations were set and the park did not even manage to sell the tickets available also due to the quite high price imposed. Moreover, the wrong allocation of staff and resources made the situation even worse and the park’s expenses almost were more than its revenues.

From this case study, many lessons can be learned. First of all, never give for granted that if one project is successful according to the parameters of one society and culture, this does not mean that if we export it else where this success will remain unchanged. Cultural factors are crucial for the success of any business and to disregard and to “attack” others traditions and customs can be destructive. Before opening a business already well established in another country, the company has to do a very deep and targeted market research in order to better understand both the culture and how that same business can adapt to the different kind of need clients in the country might have. Moreover, the success of an organization depends on how united the organization is especially the executive, and it is essential to resolve workplace issues, make employees happy with policies and have excellent communication tools. In conclusion, a company should make use of cultural differences to have a competitive advantage over other entertainment parks and make it unique, not only a copy of the already existing ones.

References:

http://www.depa.univ-paris8.fr/IMG/pdf/Disney_Case_Study.pdf

https://geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hofstede%27s_cultural_dimensions_theory

https://www2.gwu.edu/~umpleby/recent_papers/2003_cross_cultural_differences_managin_international_projects_anbari_khilkhanova_romanova_umpleby.htm

- Even more »

Account Options

- Try the new Google Books

- Advanced Book Search

- Find in a library

- All sellers »

Get Textbooks on Google Play

Rent and save from the world's largest eBookstore. Read, highlight, and take notes, across web, tablet, and phone.

Go to Google Play Now »

Bibliographic information

Why Euro Disney Is A 22-Year Money-Losing Failure

Even Mickey Mouse is not exempt from France's financial troubles .

Walt Disney announced on Monday a €1 billion ($1.25 billion) bailout plan to rescue its subsidiary Disneyland Paris, the Financial Times reported .

The French theme park is still Europe's top tourist destination, but it has been hit by the financial crisis more than other competitors. To make a profit, the park needs about 15 million visitors a year: there were 14.1 in the past 12 months. Losses are expected in the order of €110 million to € 120 million ($138 million to $ 150 million).

The park is burdened by its debt, which is calculated at about €1.75 billion ($2.20 billion) and roughly 15 times its gross average earnings. Speaking with the FT, Mark Stead, the company's financial director, said: “Our Achilles' heel has always been our debt ratio, which compared to our rivals is off the charts.”

Related stories

French labor law and planning regulations also make it difficult to replicate in France the success of the other Disney enterprises. For instance, Disney vastly underestimated the cost of employing French workers in France, according to the journal of the Canadian Center of Science and Education:

Before the opening of Euro Disneyland executives had estimated labor cost would be 13% of their revenues. This was another area where the executives were wrong in their assumptions. In 1992 the true figure was 24% and in 1993 it increased to a whopping 40%. These labor cost percentages increased Euro Disneyland's debt.

Bleak situations tend to repeat at Disneyland Paris, which injected $1.7 billion in 2012 to partially cover its debt. In its 22-year history so far, the European park rarely made a profit . When it first opened in 1992, critics dubbed the resort a "cultural Chernobyl." In 1994, two years after it opened its doors, it was saved from bankruptcy by a $350 million investment from the Saudi royal family, which now owns 38% of shares, as reported by Arabian Business .

In 2010 the resort made headlines by the suicides of two of its chefs , although a direct link to the working conditions in the park's kitchens has never been proved.

In addition, most of the visitors' home countries share the same problems: with Italian, French, and Spanish economies all in recession, people are not spending on Goofy and Donald Duck. Between April and June this year, Disneyland Paris sold 12,000 fewer hotel room nights compared with the same period the previous year. Fewer visitors from France and business trips counted for the biggest drop.

The European malaise is a stark contrast with the soundness of the American parks in Florida and California, which recorded revenues growth of 10% in the most recent financial year as reported by Disney's latest financial report .

Back in France, much is expected from a new Star Wars-themed attraction set to open in 2017, on the 25th birthday of the European operation: may the force be with them.

- Main content

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Euro Disney Case Study

Related Papers

Gabriel Baltazar

Revista de la Facultad de Medicina

María Francisca Alonso

Acta Informatica Medica

Samir Dedovic

In dem Beitrag wird von einer Untersuchung berichtet, die ermitteln sollte, wie die Lebenswelt und der Erziehungsalltag von Familien mit kleinen Kindern bis zu drei Jahren aussieht, welche Probleme solche Familien haben und wie sie damit umgehen. In dem Beitrag wird ein Aspekt herausgegriffen: Von welcher Art von Problemen fühlen sich diese Eltern subjektiv besonders belastet? Für die Erhebung der Daten wurden Intensivinterviews mit 34 Familien (verheiratete und unverheiratete Paare) aus der unteren sozialen Hälfte der Bevölkerung in zwei großstädtischen Bezirken (Neubaublock-Siedlung, älteres Arbeiterviertel) durchgeführt. Bei wiederholten Besuchen (bis zu zehn pro Familie und über mehrere Monate) wurden intensive Gespräche zu verschiedenen Themenbereichen geführt und Beobachtungen von Alltagsszenen auf Video aufgezeichnet und mit den Familien besprochen. Darüber hinaus fanden Einzelinterviews mit Frauen und Männern statt. Über die Ergebnisse wird berichtet: Der am häufigsten genan...

Direito Civil Contemporâneo e Direitos Fundamentais

Mateus Araújo Molina

novian smkn2

Determinan dan Invers Matriks

Jurnal SOLMA

Vera Yuli Erviana

Pemerintah Kulonprogo berupaya menciptakan desa bebas sampah hal tersebut dibuktikan dengan mendirikan bank sampah sebanyak 100 unit tak terkecuali di Desa Karangsari. Pengelolaan sampah hingga saat ini belum optimal padahal sampah dapat diolah menjadi barang bernilai ekonomis. Keterbatasan pengetahuan dan minimnya keterampilan menjadi kendala dalam pengolahan limbah. Maka dari itu perlu adanya upaya untuk meningkatkan SDM dalam pengelolaan sampah organik maupun anorganik. Pemberdayaan masyarakat menuju desa berbasis sampah di Desa Karangsari Kecamatan Pengasih Kulonprogo bertujuan untuk menciptakan lingkungan yang sehat, membuka lapangan pekerjaan, terciptanya produk unggulan desa ramah lingkungan dan menunjang potensi pariwisata di Kulonprogo sehingga dapat meningkatkan pendapatan masyarakat dan pendapatan daerah. Metode yang digunakan yaitu dengan penyuluhan dan pelatihan kepada masyarakat. Penyuluhan dan pelatihan yang diberikan tentang pengolahan limbah organik dan anorganik be...

European Journal of Radiology

Katsuyuki Kiura

Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation

Alexandra Scholze

KDD : proceedings / International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining

Multi-task learning (MTL) aims to improve the performance of multiple related tasks by exploiting the intrinsic relationships among them. Recently, multi-task feature learning algorithms have received increasing attention and they have been successfully applied to many applications involving high-dimensional data. However, they assume that all tasks share a common set of features, which is too restrictive and may not hold in real-world applications, since outlier tasks often exist. In this paper, we propose a Robust MultiTask Feature Learning algorithm (rMTFL) which simultaneously captures a common set of features among relevant tasks and identifies outlier tasks. Specifically, we decompose the weight (model) matrix for all tasks into two components. We impose the well-known group Lasso penalty on row groups of the first component for capturing the shared features among relevant tasks. To simultaneously identify the outlier tasks, we impose the same group Lasso penalty but on column...

RELATED PAPERS

Speech Prosody 2014

Veronique Auberge

Cell and tissue research

Sigit Prastowo

American journal of medical genetics

Celia Badenas

Natural Product Research

Fabrice Boyom

Perspectivas Médicas

Monica Hayashida

Pedro Pérez Herrero

El hombre detrás del maestro, el amigo detrás del hombre

Irma-Susana Carbajal-Vaca

Journal of Phycology

Elizabeth Fátima Sosa Martínez

Pericles Zouhair

Majalah Kedokteran Bandung

Ida Parwati

paul higate

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 15 May 2024

Arresting failure propagation in buildings through collapse isolation

- Nirvan Makoond ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5203-6318 1 ,

- Andri Setiawan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2791-6118 1 ,

- Manuel Buitrago ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5561-5104 1 &

- Jose M. Adam ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9205-8458 1

Nature volume 629 , pages 592–596 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

244 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Civil engineering

- Mechanical engineering

Several catastrophic building collapses 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 occur because of the propagation of local-initial failures 6 , 7 . Current design methods attempt to completely prevent collapse after initial failures by improving connectivity between building components. These measures ensure that the loads supported by the failed components are redistributed to the rest of the structural system 8 , 9 . However, increased connectivity can contribute to collapsing elements pulling down parts of a building that would otherwise be unaffected 10 . This risk is particularly important when large initial failures occur, as tends to be the case in the most disastrous collapses 6 . Here we present an original design approach to arrest collapse propagation after major initial failures. When a collapse initiates, the approach ensures that specific elements fail before the failure of the most critical components for global stability. The structural system thus separates into different parts and isolates collapse when its propagation would otherwise be inevitable. The effectiveness of the approach is proved through unique experimental tests on a purposely built full-scale building. We also demonstrate that large initial failures would lead to total collapse of the test building if increased connectivity was implemented as recommended by present guidelines. Our proposed approach enables incorporating a last line of defence for more resilient buildings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Design principles for strong and tough hydrogels

Frequent disturbances enhanced the resilience of past human populations

Superlative mechanical energy absorbing efficiency discovered through self-driving lab-human partnership

Disasters recorded from 2000 to 2019 are estimated to have caused economic losses of US$2.97 trillion and claimed approximately 1.23 million lives 11 . Most of these losses can be attributed to building collapses 12 , which are often characterized by the propagation of local-initial failures 13 that can arise because of extreme or abnormal events such as earthquakes 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , floods 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , storms 21 , 22 , landslides 23 , 24 , explosions 25 , vehicle impacts 26 and even construction or design errors 6 , 26 . As the world faces increasing trends in the frequency and intensity of extreme events 27 , 28 , it is arguably now more important than ever to design robust structures that are insensitive to initial damage 13 , 29 , irrespective of the underlying threat causing it.

Most robustness design approaches used at present 8 , 9 , 30 , 31 aim to completely prevent collapse initiation after a local failure by providing extensive connectivity within a structural system. Although these measures can ensure that the load supported by a failed component is redistributed to the rest of the structure, they are neither viable nor sustainable when considering larger initial failures 13 , 25 , 32 . In these situations, the implementation of these approaches can even result in collapsing parts of the building pulling down the rest of the structure 10 . The fact that several major collapses have occurred because of large initial failures 6 raises serious concerns about the inadequacy of the current robustness measures.

Traditionally, research in this area has focused on preventing collapse initiation after initial failures rather than on preventing collapse propagation. This trend dates back to the first impactful studies in the field of structural robustness, which were performed after a lack of connectivity enabled the progressive collapse of part of the Ronan Point tower in 1968 (ref. 33 ). Although completely preventing any collapse is certainly preferable to limiting the extent of a collapse, the occurrence of unforeseeable incidents is inevitable 34 and major building collapses keep occurring 1 , 2 , 3 .

Here we present an original approach for designing buildings to isolate the collapse triggered by a large initial failure. The approach, which is based on controlling the hierarchy of failures in a structural system, is inspired by how lizards shed their tails to escape predators 35 . The proposed hierarchy-based collapse isolation design ensures sufficient connectivity for operational conditions and after local-initial failures for which collapse initiation can be completely prevented through load redistribution. These local-initial failures can even be greater than those considered by building codes. Simultaneously, the structural system is also designed to separate into different parts and isolate a collapse when its propagation would otherwise be inevitable. As in the case of lizard tail autotomy 35 , this is achieved by promoting controlled fracture along predefined segment borders to limit failure propagation. In this work, hierarchy-based collapse isolation is applied to framed building structures. Developing this approach required a precise characterization of the collapse propagation mechanisms that need to be controlled. This was achieved using computational simulations that were validated through a specifically designed partial collapse test of a full-scale building. The obtained results demonstrate the viability of incorporating hierarchy-based collapse isolation in building design.

Hierarchy-based collapse isolation

Hierarchy-based collapse isolation design makes an important distinction between two types of initial failures. The first, referred to as small initial failures, includes all failures for which it is feasible to completely prevent the initiation of collapse by redistributing loads to the remaining structural system. The second type of initial failure, referred to as large initial failures, includes more severe failures that inevitably trigger at least a partial collapse.

The proposed design approach aims to (1) arrest unimpeded collapse propagation caused by large initial failures and (2) ensure the ability of a building to develop alternative load paths (ALPs) to prevent collapse initiation after small initial failures. This is achieved by prioritizing a specific hierarchy of failures among the components on the boundary of a moving collapse front.

Buildings are complex three-dimensional structural systems consisting of different components with very specific functions for transferring loads to the ground. Among these, vertical load-bearing components such as columns are the most important for ensuring global structural stability and integrity. Therefore, hierarchy-based collapse isolation design prevents the successive failure of columns, which would otherwise lead to catastrophic collapse. Although the exact magnitude of dynamic forces transmitted to columns during a collapse process is difficult to predict, these forces are eventually limited by the connections between columns and floor systems. In the proposed approach, partial-strength connections are designed to limit the magnitude of transmitted forces to values that are lower than the capacity of columns to resist unbalanced forces (see section ‘ Building design ’). This requirement guarantees a specific hierarchy of failures during collapse, whereby connection failures always occur before column failures. As a result, the collapse following a large initial failure is always restricted to components immediately adjacent to those directly involved in the initial failure. However, it is still necessary to ensure a lower bound on connection strengths to activate ALPs after small initial failures. Therefore, cost-effective implementation of hierarchy-based collapse isolation design requires finding an optimal balance between reducing the strength of connections and increasing the capacity of columns.

To test and verify the application of our proposed approach, we designed a real 15 m × 12 m precast reinforced concrete building with two 2.6-m-high floors. This basic geometry represents a building size that can be built and tested at full-scale while still being representative of current practices in the construction sector. The structural type was selected because of the increasing use of prefabricated construction for erecting high-occupancy buildings such as hospitals and malls because of several advantages in terms of quality, efficiency and sustainability 36 .

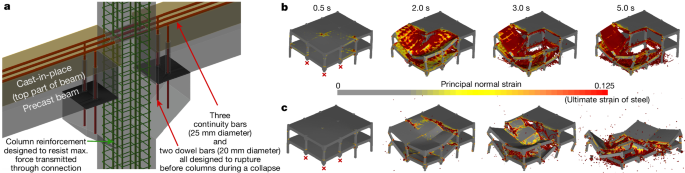

The collapse behaviour of possible design options (Extended Data Fig. 1 ) subjected to both small and large initial failures was investigated using high-fidelity collapse simulations (Fig. 1 ) based on the applied element method (AEM; see section ‘ Modelling strategy ’). The ability of these simulations to accurately represent collapse phenomena for the type of building being studied was later validated by comparing its predictions to the structural response observed during a purposely designed collapse test of a full-scale building (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Video 7 ).

a , Partial-strength beam–column connection optimized for hierarchy-based collapse isolation. b , Partial collapse of a building designed for hierarchy-based collapse isolation (design H) after the loss of a corner column and two penultimate-edge columns. c , Total collapse of conventional building design (design C) after the same large initial failure scenario.

Following the preliminary design of a structure to resist loads suitable for office buildings, two building design options considering different robustness criteria were further investigated (see section ‘ Building design ’). The first option, design H (hierarchy-based), uses optimized partial-strength connections and enhanced columns (Fig. 1a ) to fulfil the requirements of hierarchy-based collapse isolation design. The second option, design C (conventional), is strictly based on code requirements and provides a benchmark comparison for evaluating the effectiveness of the proposed approach. It uses full-strength connections to improve robustness as recommended in current guidelines 37 and building codes 8 , 9 .

Simulations predicted that both design H and design C could develop stable ALPs that are able to completely prevent the initiation of collapse after small initial failure scenarios that are more severe than those considered in building codes 8 , 9 (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

When subjected to a larger initial failure, simulations predict that design H can isolate the collapse to only the region directly affected by the initial failure (Fig. 1b ). By contrast, design C, with increased connectivity, causes collapsing elements to pull down the rest of the structure, leading to total collapse (Fig. 1c ). These two distinct outcomes demonstrate that the prevention of unimpeded collapse propagation can only be ensured when hierarchy-based collapse isolation is implemented (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Video 1 ).

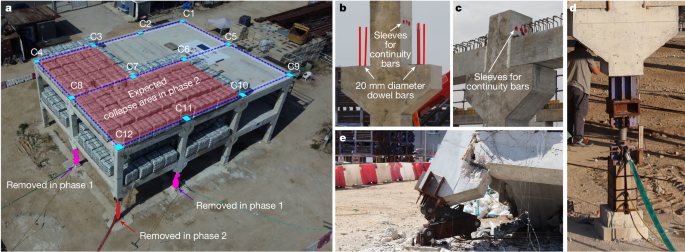

Testing a full-scale precast building

To confirm the expected performance improvement that can be achieved with the hierarchy-based collapse isolation design, a full-scale building specimen corresponding to design H was purposely built and subjected to two phases of testing as part of this work (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Information Sections 1 and 2 ). The precast structure was constructed with continuous columns cast together with corbels (Supplementary Video 4 ). The columns were cast with prepared dowel bars and sleeves for placing continuous top beam reinforcement bars through columns (Fig. 2b,c ). The bars used for these two types of reinforcing element (Fig. 1a ) were specifically selected to produce partial-strength connections. These connections are strong enough for the development of ALPs after small initial failures but weak enough to enable hierarchy-based collapse isolation after large initial failures.

a , Full-scale precast concrete structure and columns removed in different testing phases. The label used for each column is shown. The location of beams connecting the different columns is indicated by the dotted lines above the second-floor level. The expected collapse area in the second phase of testing is indicated. b , Typical first-floor connection before placement of beams during construction. c , Typical second-floor connection after placement of precast beams during construction. Both b and c show columns with two straight precast beams on either side (C2, C3, C6, C7, C10 and C11). d , Device used for quasi-static removal of two columns in the first phase of testing. e , Three-hinged mechanism used for dynamic removal of corner column in the second phase of testing.

After investigating different column-removal scenarios from different regions of the test building (see section ‘ Experiment and monitoring design ’, Extended Data Fig. 5 and Supplementary Video 2 ), two phases of testing were defined to capture relevant collapse-related phenomena and validate the effectiveness of hierarchy-based collapse isolation. Separating the test into two phases allowed two different aspects to be analysed: (1) the prevention of collapse initiation after small initial failures and (2) the isolation of collapse after large initial failures.

Phase 1 involved the quasi-static removal of two penultimate-edge columns using specifically designed removable supports (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 6 ). This testing phase corresponds to a small initial failure scenario for which design H was able to develop ALPs to prevent collapse initiation. Phase 2 reproduced a large initial failure through the dynamic removal of the corner column found between the two previously removed columns using a three-hinged collapsible column (Fig. 2e ).

During both testing phases, a distributed load (11.8 kN m −2 ) corresponding to almost twice the magnitude specified in Eurocodes 38 for accidental design situations (6 kN m −2 ) was imposed on bays expected to collapse in phase 2 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Video 5 ). Predictive simulations indicated that the failure mode and overall collapse would be almost identical when comparing this partial loading configuration with that in which the entire building is loaded (Supplementary Video 3 ). However, the partial loading configuration turns out to be more demanding for the part of the structure expected to remain upright as evidenced by the greater drifts it produces during collapse (see section ‘ Experiment and monitoring design ’ and Extended Data Fig. 7 ). The structural response during all phases of testing was extensively monitored with an array of different sensors (see section ‘ Experiment and monitoring design ’ and Supplementary Information Section 3 ) that provided the information used as a basis for the analyses presented in the following sections.

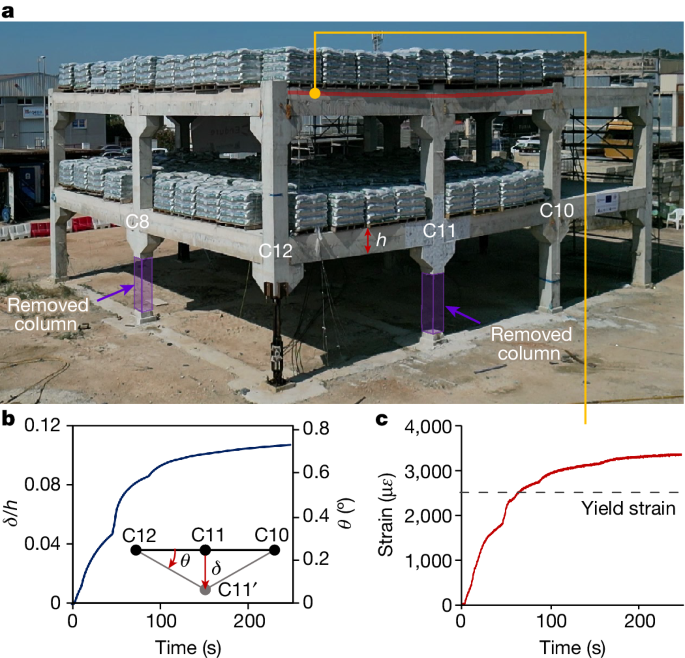

Preventing collapse initiation

Collapse initiation was completely prevented after the removal of two penultimate-edge columns in phase 1 of testing (Fig. 3a ), demonstrating that design H complies with the robustness requirements included in current building standards 8 , 9 , 39 . As this initial failure scenario is more severe than those considered by standardized design methods 8 , 9 , 30 , it represents an extreme case for which ALPs are still effective. As such, the outcome of phase 1 demonstrates that implementing hierarchy-based collapse isolation design does not impair the ability of this structure to prevent collapse initiation.

a , Test building during phase 1 of testing after removal of columns C8 and C11. The beam depth ( h ) used to compute the ratio plotted in b is shown and the location of the strain measurement plotted in c is indicated. b , Evolution of beam deflection expressed as a ratio of beam depth at the location of removed column C11. The chord rotation of the beams bridging over this removed column is also indicated using a secondary vertical axis. c , Strain increase in continuity reinforcement in the second-floor beam between C12 and C11.

Source Data

Analysis of the structural response during phase 1 (Supplementary Information Section 4 ) shows that collapse was prevented because of the redistribution of loads through the beams (Fig. 3b,c ), columns (Extended Data Fig. 8 ) and slabs (Supplementary Report 4 ) adjacent to the removed columns. The beams bridging over the removed columns sustained loads through flexural action, as evidenced by the magnitude of the vertical displacement recorded at the removal locations (Fig. 3b ). These values were far too small to allow the development of catenary forces, which only begin to appear when displacements exceed the depth of the beam 40 .

The flexural response of the structure after the loss of two penultimate-edge columns was only able to develop because of the specific reinforcement detailing introduced in the design. This was verified by the increase in tensile strains recorded in the continuous beam reinforcement close to the removed column (Fig. 3c ) and in ties placed between the precast hollow-core planks in the floor system close to column C7 (Supplementary Information Section 4 ). The latter also proves that the slabs contributed notably to load redistribution after column removal.

In general, the structure experienced only small movements and suffered very little permanent damage during phase 1 (Supplementary Information Section 4 ), despite the high imposed loads used for testing. The only reinforcement bars showing some signs of yielding were the continuous reinforcement bars of beams close to the removed columns (Fig. 3c ).

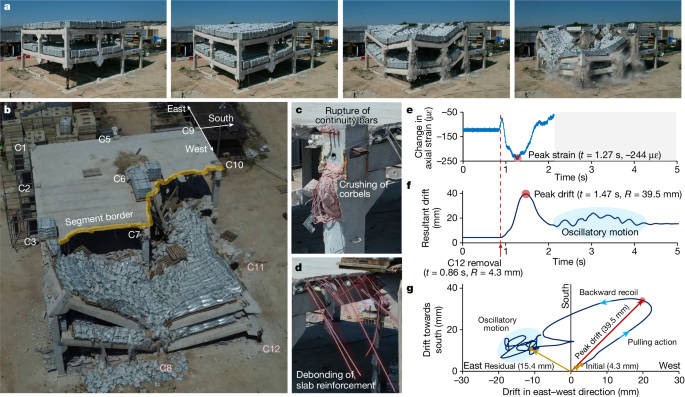

Arresting collapse propagation

Following the removal of two penultimate-edge columns in phase 1, the sudden removal of the C12 corner column in phase 2 triggered a collapse that was arrested along the border delineated by columns C3, C7, C6 and C10 (Fig. 4a–d and Supplementary Video 6 ). Thus, the viability of hierarchy-based collapse isolation design is confirmed.

a , Collapse sequence during phase 2 of testing. b , Partial collapse of full-scale test building (design H) after the removal of three columns. The segment border in which collapse propagation was arrested is indicated. The axes shown at column C9 correspond to those used in f to indicate the changing direction of the resultant drift measured at this location. c , Failure of beam–column connections at collapse border. d , Debonding of reinforcement in the floor at collapse border. e , Change in average axial strains measured in column C7. A negative change represents an increase in compressive strains. f , Magnitude of resultant drift measured at C9. g , Change in direction of resultant drift measured at C9. The initial drift after phase 1 of testing and the residual drift after the upright part of the building stabilized are also shown in the plot.

During the initial stages following the removal of C12, the collapsing bays next to this column pulled up the columns on the opposite corner of the building (columns C1, C3 and C6). During this process, column C7 behaves like a pivot point, experiencing a significant increase in compressive forces (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Information Section 5 ). This phenomenon was enabled by the connectivity between collapsing parts and the rest of the structure. If allowed to continue, this could have led to successive column failures and unimpeded collapse propagation. However, during the test, the rupture of continuous reinforcement bars (Fig. 4c ) occurred as the connections failed and halted the transmission of forces to columns. These connection failures occurred before any column failures, as intended by the hierarchy-based collapse isolation design of the structural system. Specifically, this type of connection failure occurred at the junctions with the two columns (C7 and C10) immediately adjacent to the failure origin (around C8, C11 and C12), effectively segmenting the structure along the border shown in Fig. 4b . Segmentation along this border was completed by the total separation of the floor system, which was enabled by the debonding of slab reinforcements at the segment border (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Video 8 ).

Observing the building drift measured at the top of column C9 (Fig. 4f ) enabled us to better understand the nature of forces acting on the building further away from the collapsing region. The initial motion shows the direction of pulling forces generated by the collapsing elements (Fig. 4g ). This drift peaks very shortly after the point in time when separation of the collapsing parts occurs (Fig. 4f ). After this peak, the upright part of the structure recoiled backwards and experienced an attenuated oscillatory motion before finding a new stable equilibrium (Fig. 4g ). The magnitude of the measured peak drift is comparable to the drift limits considered in seismic regions when designing against earthquakes with a 2,500-year return period 41 (Supplementary Information Section 5 ). This indicates that the upright part of the structure was subjected to strong dynamic horizontal forces as it was effectively tugged by the collapsing elements falling to the ground. The building would have failed because of these unbalanced forces had hierarchy-based collapse isolation design not been implemented.

The upright building segment suffered permanent damages as evidenced by the residual drift recorded at the top of column C9 (Fig. 4g ). This is further corroborated by the fact that several reinforcement bars in this part of the structure yielded, particularly in areas close to the segment border (Supplementary Report 5 ). Despite the observed level of damage, safe evacuation and rescue of people from this building segment would still be possible after an extreme event, saving lives that would have been lost had a more conventional robustness design (design C) been used instead.

Discussion and future outlook

Our results demonstrate that the extensive connectivity adopted in conventional robustness design can lead to catastrophic collapse after large initial failures. To address this risk, we have developed and tested a collapse isolation design approach based on controlling the hierarchy of failures occurring during the collapse. Specifically, it is ensured that connection failures occur before column failures, mitigating the risk of collapse propagation throughout the rest of the structural system. The proposed approach has been validated through the partial collapse test of a full-scale precast building, showing that propagating collapses can be arrested at low cost without impairing the ability of the structure to completely prevent collapse initiation after small initial failures.

The reported findings show a last line of defence against major building collapses due to extreme events. This paves the way for the proposed solution to be developed, tested and implemented in different building types with different building elements. This discovery opens opportunities for robustness design that will lead to a new generation of solutions for avoiding catastrophic building collapses.

Building design

Our hierarchy-based collapse isolation approach ensures buildings have sufficient connectivity for operational conditions and small initial failures, yet separate into different parts and isolate a collapse after large initial failures. We chose a precast construction as our main structural system for our case study. A notable particularity of precast systems compared with cast-in-place buildings is that the required construction details can be implemented more precisely. We designed and systematically investigated two precast building designs: designs H and C.

Design H is our building design in which the hierarchy-based collapse isolation approach is applied. Design H was achieved after several preliminary iterations by evaluating various connections and construction details commonly adopted in precast structures. The final design comprises precast columns with corbels connected to a floor system (partially precast beams and hollow-core slabs) through partial-strength beam–column connections (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information Section 1 ). This partial-strength connection was achieved by (1) connecting the bottom part of the beam (precast) to optimally designed dowel bars anchored to the column corbels and (2) passing continuous top beam bars through the columns. With this partial-strength connection, we have more direct control over the magnitude of forces being transferred from the floor system to the columns, which is a key aspect for achieving hierarchy-based collapse isolation. The hierarchy of failures was initially implemented through the beam–column connections (local level) and later verified at the system (global) level.

At the local level, three main components are designed according to the hierarchy-based concept: (1) top continuity bars of the beams; (2) dowel bars connecting beams to corbels; and (3) columns.

Top continuity bars of beams: To allow the structural system to redistribute the loads after small initial failures, top reinforcement bars in all beams were specifically designed to fulfil structural robustness requirements (Extended Data Fig. 3 ). Particularly, we adopted the prescriptive tying rules (referred to as Tie Forces) of UFC 4-023-03 (ref. 9 ) to perform the design of the ties. The required tie strength F i in both the longitudinal and transverse directions for the internal beams is expressed as

For the peripheral beams, the required tie strength F P is expressed as

where w F = floor load (in kN m −2 ); D = dead load (in kN m −2 ); L = live load (in kN m −2 ); L 1 = greater of the distances between the centres of the columns, frames or walls supporting any two adjacent floor spaces in the direction under consideration (in m); L P = 1.0 m; and W C = 1.2 times dead load of cladding (neglected in this design).

These required tie strengths are fulfilled with three bars (20 mm diameter) for the peripheral beams and three bars (25 mm diameter) for the internal beams. These required reinforcement dimensions were implemented through the top bars of the beam and installed continuously (lap-spliced, internally, and anchored with couplers at the ends) throughout the building (Extended Data Fig. 1 ).

Dowel bars connecting the beam and corbel of the column: The design of the dowel bars is one of the key aspects in achieving partial-strength connections that fail at a specific threshold to enable segmentation. These dowel bars would control the magnitude of the internal forces between the floor system and column while allowing for some degree of rotational movement. The dowels were designed to resist possible failure modes using expressions proposed in the fib guidelines 37 . Several possible failure modes were checked: splitting of concrete around the dowel bars, shear failure of the dowel bars and forming a plastic hinge in the dowel. The shear capacity of a dowel bar loaded in pure shear can be determined according to the Von Mises yield criterion:

where f yd is the design yield strength of the dowel bar and A s is the cross-sectional area of the dowel bar. In case of concrete splitting failure, the highly concentrated reaction transferred from the dowel bar shall be designed to be safely spread to the surrounding concrete. The strut and tie method is recommended to perform such a design 42 . If shear failure and splitting of concrete do not occur prematurely, the dowel bar will normally yield in bending, indicated by the formation of a plastic hinge. This failure mode is associated with a significant tensile strain at the plastic hinge location of the dowel bar and the crushing of concrete around the compression part of the dowel. The shear resistance achieved at this state for dowel (ribbed) bars across a joint of a certain width (that is, the neoprene bearing) can be expressed as

where α 0 is a coefficient that considers the bearing strength of concrete and can be taken as 1.0 for design purposes, α e is a coefficient that considers the eccentricity, e is the load eccentricity and shall be computed as the half of the joint width (half of the neoprene bearing thickness), Φ and A s are the diameter and the cross-sectional area of the dowel bar, respectively, f cd,max is the design concrete compressive strength at the stronger side, σ sn is the local axial stress of the dowel bar at the interface location, \({f}_{{\rm{yd}},{\rm{red}}}={f}_{{\rm{yd}}}-{\sigma }_{{\rm{sn}}}\) is the design yield strength available for dowel action, f yd is the yield strength of the dowel bar and μ is the coefficient of friction between the concrete and neoprene bearing. By performing the checks on these three possible failure modes, we selected the final (optimum) design with a two dowel bars (20 mm diameter) configuration.

Columns: The proposed hierarchy-based approach requires columns to have adequate capacity to resist the internal forces transmitted by the floor system during a collapse. By fulfilling this strength hierarchy, we can ensure and control that failure happens at the connections first before the columns fail, thus preventing collapse propagation. The columns were initially designed according to the general procedure prescribed by building standards. Then, the resulting capacity was verified using the modified compression field theory (MCFT) 43 to ensure that it was higher than the maximum expected forces transmitted by the connection to the floor system. MCFT was derived to consistently fulfil three main aspects: equilibrium of forces, compatibility and rational stress–strain relationships of cracked concrete expressed as average stresses and strains. The principal compressive stress in the concrete f c 2 is expressed not only as a function of the principal compressive strain ε 2 but also of the co-existing principal tensile strain ε 1 , known as the compression softening effect:

where f c 2max is the peak concrete compressive strength considering the perpendicular tensile strain, \({f}_{c}^{{\prime} }\) is the uniaxial compressive strength, and \({\varepsilon }_{{c}^{{\prime} }}\) is the peak uniaxial concrete compressive strain and can be taken as −0.002. In tension, concrete is assumed to behave linearly until the tensile strength is achieved, followed by a specific decaying function 43 . Regarding aggregate interlock, the shear stress that can be transmitted across cracks v ci is expressed as a function of the crack width w , and the required compressive stress on the crack f ci (ref. 44 ):

where a refers to the maximum aggregate size in mm and the stresses are expressed in MPa. The MCFT analytical model was implemented to solve the sectional and full-member response of beams and columns subjected to axial, bending and shear in Response 2000 software (open access) 45 , 46 . In Response 2000, we input key information, including the geometries of the columns, reinforcement configuration and the material definition for the concrete and the reinforcing bars. Based on this information, we computed the M – V (moment and shear interaction envelope) and M – N (moment and axial interaction envelope) diagrams that represent the capacity of the columns. The results shown in Extended Data Fig. 4 about the verification of the demand and capacity envelopes were obtained using the analytical procedure described here.

At the global level, the initially collapsing regions of the building generate a significant magnitude of dynamic unbalanced forces. The rest of the building system must collectively resist these unbalanced forces to achieve a new equilibrium state. Depending on the design of the structure, this phenomenon can lead to two possible scenarios: (1) major collapse due to failure propagation or (2) partial collapse only of the initially affected regions. The complex interaction between the three-dimensional structural system and its components must be accounted for to evaluate the structural response during collapse accurately. Advanced computational simulations, described in the ‘ Modelling strategy ’ section, were adopted to analyse the global building to verify that major collapse can be prevented. The final design obtained from the local-level analysis (top continuity bars, dowel bars and columns) was used as an input for performing the global computational simulations. Certain large initial failures deemed suitable for evaluating the performance of this building were simulated. In case failure propagation occurs, the original hierarchy-based design must be further adapted. An iterative process is typically required involving several simulations with various building designs to achieve an optimum result that balances the cost and desired collapse performance. The final iteration of design H, which fulfils both the local and global hierarchy checks, is provided in Extended Data Fig. 1 .

Design C is a conventional building design that complies with current robustness standards but does not explicitly fulfil our hierarchy-based approach. The same continuity bars used in design H were used in design C. We adopted a full-strength connection as recommended by the fib guideline 37 . The guideline promotes full connectivity to enhance the development of alternative load paths for preventing collapse initiation. In design C, we used a two dowel bars (32 mm diameter) configuration to ensure full connectivity when the beams are working at their maximum flexural capacity. Another main difference was that the columns in design C were designed according to codes and current practice (optimal solution) without explicitly checking that hierarchy-based collapse isolation criteria are fulfilled. The final design of the columns and connections adopted in design C is provided in Extended Data Fig. 1 .

Modelling strategy

We used the AEM implemented in the Extreme Loading for Structures software to perform all the computational simulations presented in this study 47 (Extended Data Figs. 2 – 5 and 7 and Supplementary Videos 1 , 2 , 3 and 7 ). We chose the AEM for its ability to represent all phases of a structural collapse efficiently and accurately, including element separation (fracture), contact and collision 47 . The method discretizes a continuum into small, finite-size elements (rigid bodies) connected using multiple normal and shear springs distributed across each element face. Each element has six degrees of freedom, three translational and three rotational, at its centre, whereas the behaviour of the springs represents all material constitutive models, contact and collision response. Despite the simplifying assumptions in its formulation 48 , its ability to accurately account for large displacements 49 , cyclic loading 50 , as well as the effects of element separation, contact and collision 51 has been demonstrated through many comparisons with experimental and theoretical results 47 .

Geometric and physical representations

We modelled each of the main structural components of the building separately, including the columns, beams, corbels and hollow-core slabs. We adopted a consistent mesh size with an average (representative) size of 150 mm. Adopting this mesh configuration resulted in a total number of 98,611 elements. We defined a specialized interface with no tensile or shear strength between the precast and cast-in-situ parts to allow for localized deformations that occur at these locations. The behaviour of the interface was mainly governed by a friction coefficient of 0.6, which was defined according to concrete design guidelines 52 , 53 , 54 . The normal stiffness of these interfaces corresponded to the stiffness of the concrete cast-in-situ topping. The elastomeric bearing pads supporting the precast beams on top of the corbels were also modelled with a similar interface having a coefficient of friction of 0.5 (ref. 55 ).

Element type and constitutive models

We adopted an eight-node hexahedron (cube) element with the so-called matrix-springs connecting adjacent cubes to model the concrete parts. We adopted the compression model in refs. 56 , 57 to simulate the behaviour of concrete under compression. Three specific parameters are required to define the response envelope: the initial elastic modulus, the fracture parameter and the compressive plastic strain. For the behaviour in tension, the spring stiffness is assumed to be linear (with the initial elastic modulus) until reaching the cracking point. The shear behaviour is considered to remain linear up to the cracking of the concrete. The interaction between normal compressive and shear stress follows the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. After reaching the peak, the shear stress is assumed to drop to a certain residual value affected by the aggregate interlock and friction at the cracked surface. By contrast, under tension, both normal and shear stresses drop to zero after the cracking point. The steel reinforcement bars were simulated as a discrete spring element with three force components: the normal spring takes the principal/normal forces parallel to the rebar, and two other springs represent the reinforcement bar in shear (dowelling). Three distinct stages are considered: elastic, yield plateau and strain hardening. A perfect bond behaviour between the concrete and the reinforcement bars was adopted. We assigned the material properties based on the results of the laboratory tests performed on reinforcement bars and concrete cylinders (Supplementary Information Section 2 ).

Boundary conditions and loading protocol