- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 October 2018

Consumption habits of school canteen and non-canteen users among Norwegian young adolescents: a mixed method analysis

- Arthur Chortatos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1052-329X 1 ,

- Laura Terragni 1 ,

- Sigrun Henjum 1 ,

- Marianne Gjertsen 1 ,

- Liv Elin Torheim 1 &

- Mekdes K Gebremariam 2 , 3

BMC Pediatrics volume 18 , Article number: 328 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

10 Citations

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

Food/drinks available to adolescents in schools can influence their dietary behaviours, which once established in adolescence, tend to remain over time. Food outlets’ influence near schools, known to provide access to unhealthy food/drinks, may also have lasting effects on consumption behaviours. This study aimed to gain a better understanding of the consumption habits of adolescents in the school arena by comparing different personal characteristics and purchasing behaviours of infrequent and regular school canteen users to those never or seldom using the canteen.

A convergent mixed methods design collected qualitative and quantitative data in parallel. A cross-sectional quantitative study including 742 adolescents was conducted, with data collected at schools via an online questionnaire. Focus group interviews with students and interviews with school administrators formed the qualitative data content. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics and logistic regression; thematic content analysis was used to analyse qualitative data.

Sixty-seven percent of adolescents reported never/rarely using the school canteen (NEV), whereas 13% used it ≥2 times per week (OFT). When the two groups were compared, we found a significantly higher proportion of the NEV group were female, having parents with a high education, and with a high self-efficacy, whilst a significantly higher proportion of the OFT group consumed salty snacks, baked sweets, and soft-drinks ≥3 times per week, and breakfast at home < 5 days in the school week. The OFT group had significantly higher odds of purchasing food/drink from shops near school during school breaks and before/after school compared to the NEV group (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.80, 95% CI 1.07–3.01, and aOR = 3.61, 95% CI 2.17–6.01, respectively). The interviews revealed most students ate a home packed lunch, with the remainder purchasing either at the school canteen or at local shops.

Conclusions

Students using the canteen often are frequently purchasing snacks and sugar-soft drinks from shops near school, most likely owing to availability of pocket money and an emerging independence. School authorities must focus upon satisfying canteen users by providing desirable, healthy, and affordable items in order to compete with the appeal of local shops.

Peer Review reports

The school environment is an arena where many dietary norms and habits are established which potentially affect the individual throughout their future lives [ 1 ]. Owing to the considerable amount of time adolescents spend at school during the average weekday, it has been estimated that approximately one third of their food and drink is consumed in the school environment [ 2 , 3 ].

Environments which encourage a high energy intake and sedentary behaviour amongst adolescents are termed obesogenic environments, and such environments are considered to be one of the main elements behind the rapid increase in overweight and obesity among children and adolescents [ 4 ].

In this regard, the local food environment of schools, including arenas such as supermarkets and convenience stores close to the schools, is an environmental influence potentially affecting the quality of the food intake of attending adolescents [ 5 ]. Providing healthy food and drinks to adolescents in schools via canteens or vending machines plays an important role in modelling a healthy diet, particularly for those who may not have access to healthy food outside school hours, thereby making school nutrition policies a powerful tool for improving students’ nutritional status and academic achievement [ 6 ]. Yet in the school environment, foods consumed are not always obtained from on-campus sources. Research upon supermarkets and convenience stores located in the vicinity of schools has reported that these venues provide an increased accessibility to unhealthy foods and drink for school-going adolescents [ 7 ].

The Øvre Romerike region, located in the eastern part of Norway, has a total area of 2,055,550 km 2 , and composed of 6 municipalities housing approximately 100,000 people [ 8 ]. The 2016 average net income for all households in the region was 456,667 NOK, compared to the national average of 498,000 NOK for the same period [ 9 ]. In our recent investigation upon adolescents in Øvre Romerike, we reported that 33% of participants purchased food or drink in their school canteen at least once a week [ 10 ]. In addition, 27% and 34% of participants reported purchasing food and drinks from shops around schools one or more times a week, either during school breaks or on their way to or from school, respectively [ 10 ].

Investigations on adolescent behaviour in Norway and elsewhere have reported similar results, whereby approximately 30% of school-going adolescents visit local food stores for nourishment, whilst the majority are consuming their lunches at school [ 11 , 12 ].

In Norway, the average school day includes a lunch period in the middle of the day [ 13 ], and most students travel to school with a home packed lunch, usually consisting of bread slices with various toppings [ 14 , 15 ]. School canteens are often run by catering staff, with students in need of more practical education sometimes included in food preparation and selling. It is not uncommon for the canteen to be managed on a daily or occasional basis by students together with a teacher as a part of their education. School canteens most commonly offer baguettes, waffles, milk (regular or chocolate), juice, cakes and, perhaps, fruit [ 16 , 17 ]. The Norwegian Directorate of Health regularly publishes guidelines concerning school meals and eating environments, with the most recent published in 2015 [ 18 ]. The latest guidelines offer suggestions regarding topics such as length of meal times, hygiene, fresh water accessibility, the absence of sugar-rich foods and drinks, and the reduction of saturated fats on offer. The guidelines are published as a tool to assist school administration in their management of school canteens.

Eating behaviour amongst adolescents is a complex theme often involving an interplay of multiple influences and factors such as peer influence [ 19 ] and a desire to socialise whilst eating [ 20 ], a combination which often leans toward unhealthy eating practices. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for young Norwegian teens to receive pocket money [ 21 ], and this emerging autonomy aided by pocket money increases the prospect for a disruption of dietary behaviour established in the home [ 22 ].

As the school food environment has such a significant impact on food choices [ 23 , 24 ], a better understanding of adolescent’s consumption behaviour demands further attention. In particular, understanding student’s shift away from home packed lunches and canteen foods towards the appeal of off-campus shop food is necessary for implementing the successful promotion of healthier lunch alternatives at school.

The aim of the present study was to gain a better understanding of the consumption habits of adolescents in the Norwegian school lunch arena. Unlike previous ESSENS studies, here we use quantitative data combined with qualitative interviews among adolescents and school administration, in order to explore the purchasing behaviour and lifestyle demographics of the sample grouped as frequent and infrequent school canteen users compared to those never or rarely using the canteen.

Design and sample

The participants in this study were students and staff from eleven secondary schools participating in the Environmental determinantS of dietary behaviorS among adolescENtS (ESSENS) cross-sectional study [ 10 , 25 ]. Recruitment of students and staff was initiated by our making contact with principals of the twelve secondary schools in the Øvre Romerike district, after first having received permission from district school leaders. The school principals were each sent a letter detailing key elements of the proposed intervention, as well as information regarding the ESSENS study, together with a permission form requesting their school’s participation. Of the twelve secondary schools invited to participate in the study, eleven accepted the invitation.

In this mixed method approach, our sample were grouped as being part of either a quantitative or qualitative data source.

Recruitment of sample

Quantitative recruitment.

In October 2015 we recruited 8th grade adolescents for participation in a questionnaire survey. An informative letter was sent home with all 1163 adolescents in the 8th grade (average age of 12–13 years) from the 11 participating schools, containing a consent form for signing and with additional questions relating to parental education levels. A total of 781 (67%) received parental consent for participation. As the range of ages of the sample represents the lower end of the adolescent scale (10–19 years), the use of the term ‘adolescent’ here implies ‘young adolescent’. A total of 742 adolescents (64% of those invited and 95% of those with parental consent) participated in the survey. Quantitative data collection took place between October and December 2015.

Qualitative recruitment

Recruitment of adolescents to participate in the qualitative part of the study was also facilitated by approaching principals of district schools as described above, and was completed between October 2015 and January 2016. Six of the 11 participating schools were selected for qualitative data collection based upon criteria such as location (being in one of the six municipalities of Øvre Romerike), and size (based upon number of students attending). The aim was to include schools with a varied profile, with proximity to city centers, shops, and collective transport as determining factors. Thereafter a selection process for participation in the focus groups was conducted, whereby two students per class were sought after, representing both sexes. Further inclusion criteria stipulated that the students be in the 9th grade, had attended Food and Health classes, and currently lived in the Øvre Romerike area with either one or both parents.

Data collection

Quantitative data.

A web-based questionnaire was used to collect data from the adolescents, using the LimeSurvey data collection tool. The questionnaires were answered at school, taking approximately 30–45 min to complete, and queried respondents about their nutritional intake, parental rules regarding food and drink consumption, students’ school canteen and surrounding shop use, physical activity, and sedentary behaviour habits. Research group members were present during data collection to answer questions and make sure the adolescents responded independently from each other. The questionnaire relating to food behaviours completed by the sample is available online (see Additional file 1 : Appendix 1 ESSENS questionnaire relating to food behaviours).

A pilot test of the survey was conducted parallel with this process in a neighboring municipality with similar age students from the 8th grade ( n = 23). The students spent approximately 30–40 min to complete the survey, and then provided feedback regarding comprehension. The questionnaire was subsequently shortened and some questions rephrased for clarity. The results of the pilot test were not included in the final results.

Qualitative data

Focus group interviews were conducted over a period of 10 weeks, from November 2015 to January 2016. Focus group settings were favoured as they provide a more relaxed setting for data collection, facilitating the flow of a natural conversation amongst peers, especially when adult researchers interact with young subjects [ 26 ].

Six focus group interviews including a total of 55 students (29 girls, 26 boys) from the 9th grade with an average age of 13–14 years were conducted. Interviews had a duration of approximately 60 min. In addition, interview sessions with headmasters and teachers for the 9th grade students from the participating schools were also conducted. Interviews with 6 teachers (4 women and 2 men) and 6 headmasters (3 women and 3 men) were conducted from October 2015 to January 2016. The interviews with principals and teachers were each conducted separately.

Qualitative data collection took place at the selected schools using an audio recorder, with a semi-structured interview guide used for the interviews, partially inspired by a previous study conducted amongst 11–13 year old Norwegian adolescents [ 27 ]. The main themes explored by the focus group sessions were students’ eating habits, their definition of healthy and unhealthy food, attitudes towards and their impact upon diet and physical activity, as well as the student’s assessment of opportunities and barriers attached to health-promoting behaviour. School administration interviews probed food availability and meals served at the school, as well as physical activity options available for students at the schools. The interview guides used for the focus groups and the school administration are available online (see Additional file 2 : Appendix 2 Interview guide for focus group interviews, and Additional file 3 : Appendix 3 Interview guide for headmasters and teachers).

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, with names of the participants and of the schools anonymised. Interviews were analysed using a thematic analysis approach [ 28 ]. Codes were developed after an initial reading of all the transcripts and were based on the main interview questions, prior research, and emergent concepts from the current data. The initial codes were discussed among researchers and a codebook was developed. The codes were further refined during coding of subsequent transcripts. Codes were then successively grouped into general themes. The data analysis was supported by the use of NVivo software (version 10.0; QSR International, Cambridge, Mass).

Pilot testing of the intended focus group question guide was performed in October 2015 in a school belonging to a neighbouring district. After written consent was obtained from the principal of the school, 6 students from the 9th grade were selected by a 9th grade teacher from the school. Three girls and 3 boys were included in the focus group pilot test. A moderator conducted the focus group following an interview guide in order to test comprehension and flow of the planned themes. The pilot test proved effective and consequently no changes were made to the interview guide. Data from the pilot testing was not included in the results of the study.

Recruitment of school staff for participation in in-depth interviews was also facilitated by the agreement with administrative school leaders as described above. A written invitation was sent to principals and teachers of the 9th grade classes from the same 6 schools participating in focus group interviews. Those agreeing were later contacted by phone to arrange a place and time for the interview.

Pilot testing of school staff interviews was performed in October 2015 in a school belonging to a neighbouring district. Two interviews were conducted with one headmaster and one teacher separately in order to assess the comprehension and flow of the various themes probed, as well as the time used for the interview. Data from the pilot testing was not included in the results of the study.

The following measures obtained from the questionnaire were used in the quantitative analyses of the present study.

Sociodemographic measures

Two questions assessing parental education (guardian 1 and guardian 2) were included on the parental informed consent form for the adolescent. Parental education was categorised as low (12 years or less of education, which corresponded to secondary education or lower) or high (13 years or more of education, which corresponded to university or college attendance). The parent with longest education, or else the one available, was used in analysis. Participants were divided into either ethnic Norwegian or ethnic minority, with minorities defined as those having both parents born in a country other than Norway [ 29 ].

- Dietary behaviours

Frequency of carbonated sugar-sweetened soft-drink intake (hereafter referred to as soft-drinks) during weekdays was assessed using a frequency question with categories ranging from never/seldom to every weekday. Weekday frequency was categorised as less than three times per week and three or more times per week.

The questions assessing the intake of soft-drinks have been validated among 9- and 13-year-old Norwegians using a 4-day pre-coded food diary as the reference method, and moderate Spearman’s correlation coefficients were obtained [ 30 ].

Consumption of fruits and vegetables (raw and cooked) were assessed using frequency questions with eight response categories ranging from never/seldom to three times per day or more. These were further categorised as less than five times per week and five or more times per week. The questions assessing intake of fruits and vegetables have been validated among 11-year-olds with a 7-day food record as the reference method and were found to have a satisfactory ability to rank subjects according to their intake of fruits and vegetables [ 31 ].

The consumption of snacks [sweet snacks (chocolate/sweets), salty snacks (e.g. potato chips), and baked sweets (sweet biscuits/muffins and similar)] was assessed using three questions with seven response categories ranging from never/seldom to two times per day or more. These were further categorised as less than three times per week and three or more times per week. Acceptable to moderate test-retest reliability have been obtained for these measures of dietary behaviours in a previous Norwegian study conducted among 11-year-olds [ 27 ].

Self-efficacy related to the consumption of healthy foods was assessed using a scale with six items [e.g. Whenever I have a choice of the food I eat. .., I find it difficult to choose low-fat foods (e.g. fruit or skimmed milk rather than ‘full cream milk’)]. Responses were further categorised as those with ‘high’ self-efficacy (score of 3.5 or higher, from a scale of 1–5) or ‘low’ self-efficacy (under 3.5, from a scale of 1–5). The scale has been found to have adequate reliability and factorial validity among 13-year-olds [ 32 ].

Adolescents’ breakfast consumption was assessed using one question asking the adolescents on how many schooldays per week they normally ate breakfast. The answers were categorised as those eating breakfast 5 times per week or less than 5 times per week. This question has shown evidence of moderate test-retest reliability (percentage agreement of 83 and 81% respectively for weekday and weekend measures) and moderate construct validity (percentage agreement of 80 and 87% respectively for weekday and weekend measures) among 10–12 year old European children [ 27 ].

Food/drink purchases in school environment

The adolescents were asked how often they purchased foods or drinks from school canteens and on their way to and from school (answer categories ranging from ‘never’ to ‘every day’). The frequency of purchase of food/drinks at the school canteen were then re-categorised into ‘never/rarely’, ‘once per week’, or ‘two or more times per week’. The frequency of purchase of food/drinks at off-campus food stores were re-categorised into ‘never/rarely’, or ‘one or more times per week’. They were also asked about the presence of food sales outlets (e.g. supermarket, kiosk, or gas station) in a walking distance from their school (with answer categories ‘none’, ‘yes, one’, ‘yes, two’, and ‘yes, more than two’), with results categorised as ‘less than 3’ or ‘3 or more’.

Further details regarding data collection and methodology in the ESSENS study have been described previously [ 10 ]. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Norwegian Social Science Data Service (NSD 2015/44365). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents of participating students.

Statistical analyses

The study sample was divided into three groups, those who reported ‘never or rarely’ using the school canteen (NEV), those using the canteen once per week (SEL), and those reporting use of the school canteen ‘two or more times during the week’ (OFT). Results are presented as frequencies (%), with chi-square tests performed to examine differences in sociodemographic, behavioural, and dietary characteristics between the three groups. A further logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the adjusted associations between canteen use and dietary habits (salty snacks, baked sweets, soft-drinks, and home breakfast frequency). Adjustment was made for significant sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics (gender, parental education, self-efficacy) and shop use (during school break and before/after school). Logistic regression was also used to explore the adjusted association between visiting shops during school breaks or before/after school (‘never/rarely’, ‘one or more times per week’), and use of canteen (NEV, SEL, OFT). Results are presented as crude odds ratios (cOR) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Cases with missing data were excluded from relevant analyses. Because schools were the unit of measurement in this study, we checked for clustering effect through the linear mixed model procedure. Only 3% of the unexplained variance in the dietary behaviours investigated was at the school level, hence adjustment for clustering effect was not done.

A significance level of 0.05 was used. All analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Sample demographics

The mean age of the survey sample was 13.6 years ±0.3 standard deviation, 53% of participants were females, and 60% had parents with a high level of education (≥13y, Table 1 ). The proportion of adolescents who never or rarely used the school canteen was 67.4%. When comparing demographics and behavioural characteristics for the sample grouped as those using the school canteen never/rarely (NEV), those using the canteen once a week (SEL, 19.7%), and those using the canteen two or more times a week (OFT, 12.9%), we found a significantly higher proportion of the NEV group were female, having parents with a high education, and with a high self-efficacy.

Canteen use and dietary habits

When analysing the dietary habits for the sample grouped by frequency of canteen use, a significantly higher proportion of the OFT group reported consuming salty snacks, baked sweets, and soft-drinks ≥3 times per school week, and a significantly higher proportion of the NEV group reported eating breakfast 5 days in the school week compared to the SEL and OFT groups (Table 2 ). A multiple logistic regression was conducted to assess whether these significant associations between canteen use and dietary behaviours persisted after adjustment for gender, parental education, self-efficacy, and use of shops (both during and before/after school). The difference between NEV, SEL, and OFT adolescents regarding baked sweets thereafter became non-significant. However, the difference between NEV and OFT adolescents regarding salty snacks, soft-drinks, and breakfast consumption remained significant, indicating that adolescents using the canteen ≥2 times per week had increased odds for consuming salty snacks and soft-drinks (aOR 2.05, 95% CI 1.07–3.94, p < 0.03, and aOR 2.32, 95% CI 1.16–4.65, p < 0.02, respectively, data not shown). Additionally, the OFT group had reduced odds of consuming breakfast at home daily (aOR 0.48, 95% CI 0.28–0.80, p = 0.005, data not shown). No significant differences between the three groups were found for the other food items explored.

School environment

When comparing the frequency of food purchases at shops during school breaks or on the way to/from school for the NEV, SEL, and OFT groups, we found that a significantly higher proportion of OFT adolescents reported purchasing food/drink from a shop near school either during school breaks or else before or after school, one or more times during the week (Table 3 ). Logistic regression analyses revealed that the OFT group had significantly higher odds of purchasing food/drink from a shop near school, either during school breaks or else before or after school, than the NEV group (aOR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.07–3.01, and aOR = 3.61, 95% CI 2.17–6.01, respectively, Table 4 ).

Results of focus group and interview analyses

The data from the focus group interviews indicated that students were aware of issues related to food and health. A number of the relevant themes which emerged are outlined below.

Student’s lunch habits

The majority of students confirmed that most foods consumed at school were brought from home. Some students, however, stated that the other option was to purchase foods from either the canteen or local shops:

Interviewer: ….do you bring a packed lunch from home regularly? Boy2: We usually tend to buy something from the canteen. Girl5: It’s kind of both in a way. Girl5: Yes. Ehm, it is usually both, there are many who have food with them also. Also you are free to buy something. Boy1: Yes, that’s common…there are quite a few who tend to buy food at the canteen and, yes, the shop.

One teacher suggested it was the presence of pocket money that determined the source of a student’s lunch:

Teacher1: It is an incredibly large amount of money they have to buy canteen food with, especially in the 8th grade…so that means they do not have so much food with them from home, but buy it instead.

Types of foods purchased at school canteen, students’ impression of canteen

In response to the types of foods available for purchase at the canteen, student’s representing different schools reported similar food items. Overall, the students at all schools expressed a level of dissatisfaction with the healthiness of the food/drinks offered by the canteen:

Interviewer: What is the most popular items people buy [at the canteen]? Boy2: Mainly toasted sandwiches Boy2: And wraps Boy3: Eh, maybe a baguette with ham and cheese Boy1: Whole-wheat bread with cheese and ham. Capsicum maybe. Boy2: There are many different drinks one can buy, as well as yoghurt of various kinds. There is also a main thing available too, such as a baguette, pizza, or something similar. Boy2: There are many who buy toasted sandwiches and wraps. Interviewer: What can be done better in order to make other students or yourselves eat healthier from the school’s part?. Girl3: They can begin to sell more fruit and such at the canteen. Boy4: We could have healthier drink offers [from the canteen]…such as smoothies… Girl2:…and switch chocolate milk with plain milk. Boy3: [The canteen] should have healthier alternatives, not just unhealthy white-flour baguettes …with a little cheese, bit of ham and a little butter…..

Peer influence, perceived peer self-efficacy regarding healthy eating

There were questions designed to assess if students perceived other students as being more concerned with healthy eating. Those bringing food from home or considered ‘sporty’ were often perceived as eating healthy food, with the overall impression that those perceived as eating healthy tended to not purchase food at the canteen:

Interviewer: …do you think there are some in your class then, that are more concerned with eating healthy than others? Boy3: Yes, there are. Interviewer: Who are they then? Boy3: Those who ski. Interviewer: How do you know that? Or, what is it that makes them stand out? Boy2: They….don’t buy food at the canteen. Boy4: They eat healthy food Boy1: Those that eat relatively healthy food as a rule usually prepare food themselves.

A number of school staff commented upon the influence some students’ lunch habits had upon others:

Teacher6: …if there is one who begins to drop home brought food because it is boring, it become contagious over other’s behaviour I think, and then it isn’t cool to eat home packed lunches. They are at a very vulnerable age, and very affected by such things I believe. Teacher2: …(food choices are affected by) what food they have at home, how much money they have in their pocket, and what their friends eat. I think it is these three things. And I think some….won’t bring out their home packed lunch because it is not cool enough.

Prices, timing, and permission for visiting shops

In many instances, it was reported that although leaving school grounds was not allowed during school hours in individual school policy, many students frequently did so in order to visit local food shops during breaks. There were reports of shop visits outside school hours as well (before/after school). Some students also discussed the cheaper prices at the shops, as compared to the school canteen, as being an incentive to purchase from shops.

Girl2: We have some in the class that shoot off to the shops to buy some sort of fast food every day. Interviewer: So you are allowed to leave the school in your free time to buy food? Girl2: No, but after school or right before. Girl4:......They go over [to the shops] when the lunch break starts, then you see them come back when everyone has to go outside then. Boy4: Because then there are no teachers out......and then it is easy to take a trip to the shops and... Boy1: Buy cheaper things. Because they sell at a high price here.

The paradox between students visiting shops in school hours, although not allowed, was also pointed out by school staff:

Teacher1: …no, it is not allowed (to go to the shops), but there are some that do it anyway. Headmaster6: ...of course the schools must represent counterculture in some way….so our students go to the shops…and then they make use of the offers that are there…as long as they have money from home. Teacher2: …and they prefer to go (to the shops) in a group at the same time, because it is social and fun.

Types of foods purchased in shops

When questioned about the types of items purchased at the shops, the majority were in consensus that unhealthy snacks such as sweets, baked goods, and soft-drinks were mainly purchased. No participant mentioned the purchase of healthy food from the shops.

Interviewer: What do people mostly buy there then? You mentioned sweet buns..[Looks at Girl1] Boy2: Both sweet buns and doughnuts. Girl1: There are many that buy candy after school and such. Boy4: There are always some who always have money and always buy candy and such. Just like one I know who bought 1 kg of gingerbread dough here after school one day and sat down and ate it. Girl2: Mostly those….soft drinks Girl1: Soft drinks Boy1: Candy and ice-tea. Boy2: People don’t buy food at the shop…most buy themselves candy.

Adherence of school administration to guidelines for school meals

When school staff were asked about the implementation of the latest guidelines from the Norwegian Directorate of Health, most pointed out that they already offered the suggested timespan suggested for lunch, whilst others had yet to read the document.

Teacher1: We have heard there is something new that has come, but we have not spent a lot of time discussing it amongst ourselves. Teacher2: No, no relationship with them (new guidelines). I'm not sure. We do not sell sodas and juice in the cafeteria, but they [students] have it from home. Teacher3: Hehe, I don’t think I’ve seen them, no…(laughs). Headmaster1: So, what we do is to make sure that they have a good place to eat and that they have peace….we offer supervision and they do have a long enough lunch break, is it 20 minutes they should have? Headmaster2: I just have to be honest, I do not think we have come far with these.

We found the NEV group were mainly female, having a high self-efficacy regarding the consumption of healthy foods, and with parents having an education over 12 years. By contrast, the OFT adolescents had a significantly higher proportion of males consuming salty snacks, baked sweets, and soft-drinks 3 or more times a week, as well as consuming breakfast less than 5 times a week when compared to the other groups, also when controlling for gender, parental education, self-efficacy, and use of shops (both during and before/after school).

When comparing the frequency of purchasing food and drink from local shops for these groups, we found the OFT group had a significantly higher proportion purchasing food/drink from shops near the school, both during the school break as well as before or after school, one or more times per week. Logistic regression analyses revealed the OFT group had nearly twice the odds for visiting shops during the school break, and significantly higher odds for visiting shops before/after school than the NEV group of adolescents.

Of the adolescents featured in this sample, females were revealed as more likely to never or rarely use the school canteen, a finding supported by previous research amongst adolescents [ 33 , 34 ]. That females have been previously reported as having a greater self-efficacy related to healthy eating [ 35 ] may help to explain this result, although another study involving over 1200 students of comparable age found no significant difference in self-efficacy regarding gender [ 36 ]. As 67% of the sample stated that they never or rarely use the school canteen, this then begs the question of what form of lunch this group are consuming. Many of the interviews have mentioned the consumption of home packed lunches, and studies of school lunch habits amongst Norwegian adolescents have previously detailed the importance and predominance of the home packed lunch in Norwegian culture [ 37 , 38 ], with over 60% of young Norwegians reporting a packed lunch for consumption at school, a proportion similar to the results we present here. This figure is also consistent with global reports examining school lunch eating practises [ 39 ].

Our results profile the OFT group as being mostly male, skipping breakfast, with a high frequency of shop visits during and on the way to/from school, and with a higher frequency of snacks, baked sweets, and soft-drinks, elements which have featured in previous studies regarding adolescent consumer behaviour [ 12 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. A clear association between adolescents skipping breakfast and subsequent purchases of foods from shops and fast food outlets, usually on the way to or from school [ 42 , 44 , 45 , 46 ], in addition to other health-compromising behaviours [ 47 ] have been previously reported.

Although direct questions regarding pocket money were absent from our study, its role in the behaviour of this sample is evident from statements mentioning money use in the school administration interviews as well as alluded to in focus group interviews. Additionally, it stands to reason that adolescents using the school canteen often (i.e. the OFT group) would be equipped with money in order to make such purchases, as financial purchases are the norm in Norwegian secondary schools [ 48 ]. Research directed upon adolescents and pocket money has presented a number of findings that support our results regarding the OFT group, whereby access to spending money was associated with an increase of nutritionally poor food choices by adolescents, such as the increased consumption of fast-foods, soft-drinks, and unhealthy snacks off campus [ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ]. These results may also be indicative of a gender imbalance in regards to pocket money provisions, where some studies report upon more males than females receiving pocket money [ 54 , 55 ].

The mean age of this sample previously has been described as a stage in life of an emerging autonomy for young individuals, an autonomy which is exercised in terms of disposable income use and consumption of foods away from home [ 42 , 56 , 57 ]. This period of emerging autonomy may also manifest unhealthy eating behaviours as a strategy to forge identity amongst adolescents [ 58 ]. Frequent mention by students and staff in this study of themes relating to peer influence and defiance of school rules support the link between rebelliousness and unhealthy eating. Moreover, it has been reported previously that foods independently purchased by adolescents are often unhealthy, forbidden or frowned upon by parents, and express a defiant period of appearing ‘cool’ among peers, especially amongst males [ 37 , 59 , 60 , 61 ], all of which support our findings here, particularly regarding gender, self-efficacy, and peer influence.

Value for money and dissatisfaction with the school canteen were frequently mentioned in the focus group interviews, and are elements that may be affecting choices made by the groups in this study. Statements concerning student dissatisfaction with canteen prices and/or the limited healthy options available have also appeared in previous research [ 35 , 37 , 38 , 42 ]. That many of the school administrators interviewed seemed barely aware of the guidelines published by the Norwegian Directorate of Health is an alarming result, and likely adds some degree of weight upon student discontent with the school canteen. Although nearly all reports from the focus groups indicate the shops were used for unhealthy purchases, the possibility that shop purchases are a result of some adolescent’s need for healthier lunch alternatives cannot be dismissed completely.

The focus group interviews together with the quantitative data support the notion of healthy eaters avoiding the school canteen, opting instead for a home packed lunch. This view is further supported by previous reports that home prepared lunches help contribute to a healthy dietary pattern [ 39 , 62 , 63 ]. Furthermore, it has been reported that students consuming a lunch from home have significantly lower odds of consuming off-campus food during the school week [ 41 ], which further concurs with the results presented here.

By contrast, those often using the canteen – which, by all reports, could improve the healthiness of items offered – are using the off-campus shops often, purchasing mainly unhealthy snacks and drinks.

The strengths of the study include a large sample size with a high response rate at the school level, and moderate response rate at the parental level. Using a mixed method approach also provides a more comprehensive assessment of adolescent school lunch behaviours, allowing a fuller understanding of this and other adolescent food-behaviour settings by contrasting the adolescent’s own experiences with quantitative results. That the quantitative material, based on cross-sectional data, precludes any opportunity for causal inference to be made may be one of the prime weaknesses of this study. Quantitative data regarding adherence to national policy regarding school canteens, pocket money and what items it was spent upon, as well as data regarding the content and frequency of home packed lunch consumption, were also lacking from the study, where inclusion of these elements in the various analyses would have considerably strengthened the quality of results. Furthermore, reliance upon self-reported data may have led to issues regarding validity and reliability, particularly with a sample of young adolescents.

We found the majority of adolescents (67.4%) in this sample rarely or never used the school canteen. Those adolescents using the school canteen two or more times a week were also the group most likely to be purchasing food/drink from a shop near the school, either during school breaks or before/after school. This group also tended to skip breakfast and consume snacks and soft-drinks more frequently compared to the adolescents who rarely or never used the school canteen. These findings highlight a lack of satisfaction of items available for consumption at the school canteen, with adolescents intending to use the school canteen preferring instead the shops for foods that are cheaper and more desirable. Future strategies aimed at improving school food environments need to address the elements of value for money and appealing healthy food availability in the school canteen, as well as elements such as peer perception and self-identity attained from adolescent food choices, especially in contrast to the competitiveness of foods offered by nearby food outlets.

Abbreviations

Adjusted odds ratio

Confidence interval

Crude odds ratio

Environmental determinantS of dietary behaviorS among adolescENtS study

Adolescents never or rarely using the school canteen

Norwegian kroner

Adolescents using the school canteen two or more times a week

Adolescents using the school canteen once a week

Craigie AM, Lake AA, Kelly SA, Adamson AJ, Mathers JC. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2011;70:266–84.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nelson M, Bradbury J, Poulter J, McGee A, Mesebele S, Jarvis L. School meals in secondary schools in England. London: King’s College London; 2004.

Google Scholar

French SA, Story M, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. An environmental intervention to promote lower-fat food choices in secondary schools: outcomes of the TACOS study. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1507–12.

Lake A, Townshend T. Obesogenic environments: exploring the built and food environments. J R Soc Promot Heal. 2006;126:262–7.

Article Google Scholar

Day PL, Pearce J. Obesity-promoting food environments and the spatial clustering of food outlets around schools. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:113–21.

Finch M, Sutherland R, Harrison M, Collins C. Canteen purchasing practices of year 1–6 primary school children and association with SES and weight status. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30:247–51.

Harrison F, Jones AP. A framework for understanding school based physical environmental influences on childhood obesity. Health Place. 2012;18:639–48.

Akershus County. Tall og fakta 2017 [Statistics for Akershus County]. Available from: http://statistikk.akershus-fk.no/webview/

Statistics Norway. Income and wealth statistics for households 2018 [Available from: https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank/table/06944/?rxid=f7f83a05-8a59-4950-bdb5-9654860a2ae2 ?

Gebremariam MK, Henjum S, Terragni L, Torheim LE. Correlates of fruit, vegetable, soft drink, and snack intake among adolescents: the ESSENS study. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60.

Utter J, Scragg R, Schaaf D, Fitzgerald E, Wilson N. Correlates of body mass index among a nationally representative sample of New Zealand children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2007;2:104–13.

Bugge AB. Ungdoms skolematvaner–refleksjon, reaksjon eller interaksjon?[Young people's school lunch habits—reflection, reaction or interaction? In Norwegian]. National Institute for Consumer Research (SIFO), Oslo (Report 4–2007). 2007.

Lien N, van Stralen MM, Androutsos O, Bere E, Fernández-Alvira JM, Jan N, et al. The school nutrition environment and its association with soft drink intakes in seven countries across Europe–the ENERGY project. Health Place. 2014;30:28–35.

Staib M, Bjelland M, Lien, N. Mat og måltider i videregående skole – En kvantitativ landsdekkende undersøkelse blant kontaktlærere, skoleledere og ansvarlige for kantine/matbod [Pamphlet]. Norway: The Norwegian Directorate of Health; 2013 [23/05/2017]. Available from: https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/298/Mat-og-maltider-i-videregaende-skole-en-kvantitativ-landsdekkende-undersokelse-IS-2136.pdf

Johansson B, Mäkelä J, Roos G, Hillén S, Hansen GL, Jensen TM, et al. Nordic children's foodscapes: images and reflections. Food Cult Soc. 2009;12:25–51.

Løes AK. Organic and conventional public food procurement for youth in Norway. Bioforsk Rapport; 2010 [12/06/2017]. Available from: https://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2460440/Bioforsk-Rapport-2010-05-110.pdf

Ask AS, Hernes S, Aarek I, Vik F, Brodahl C, Haugen M. Serving of free school lunch to secondary-school pupils–a pilot study with health implications. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:238–44.

The Norwegian Directorate of Health. Mat og måltider i skolen. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for mat og måltider i skolen. [The Directorate of Health. Food and meals in the school. National guidelines for school food and meals.] Norway: The Norwegian Directorate of Health; 2015 [23/05/2017]. Available from: https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/mat-og-maltider-i-skolen .

Salvy S-J, De La Haye K, Bowker JC, Hermans RC. Influence of peers and friends on children's and adolescents' eating and activity behaviors. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:369–78.

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Daniel P, Gustafsson U. School lunches: children's services or children's spaces? Children's Geographies. 2010;8:265–74.

Brusdal R, Berg L. Are parents gender neutral when financing their children's consumption? Int J Consum Stud. 2010;34:3–10.

Wills W, Backett-Milburn K, Lawton J, Roberts ML. Consuming fast food: the perceptions and practices of middle-class young teenagers. In: James A, Kjorholt AT, Tinsgstad V, editors. Children, food and identity in everyday life. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2009. p. 52–68.

Chapter Google Scholar

Cullen KW, Eagan J, Baranowski T, Owens E. Effect of a la carte and snack bar foods at school on children's lunchtime intake of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:1482–6.

Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Hannan PJ, Perry CL, Story M. The association of the school food environment with dietary behaviors of young adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1168–73.

Gebremariam MK, Henjum S, Hurum E, Utne J, Terragni L, Torheim LE. Mediators of the association between parental education and breakfast consumption among adolescents: the ESSENS study. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17:61.

Eder D, Fingerson L. Interviewing children and adolescents. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA, editors. Handbook of interview research. California: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2001. p. 181–203.

Lien N, Bjelland M, Bergh IH, Grydeland M, Anderssen SA, Ommundsen Y, et al. Design of a 20-month comprehensive, multicomponent school-based randomised trial to promote healthy weight development among 11-13 year olds: the HEalth in adolescents study. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:38–51.

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. California: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1998.

Lie B. Immigration and immigrants: 2002: Statistics Norway; 2002.

Lillegaard ITL, Øverby N, Andersen L. Evaluation of a short food frequency questionnaire used among Norwegian children. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56:6399. https://foodandnutritionresearch.net/index.php/fnr/article/view/490 .

Haraldsdóttir J, Thórsdóttir I, de Almeida MDV, Maes L, Rodrigo CP, Elmadfa I, et al. Validity and reproducibility of a precoded questionnaire to assess fruit and vegetable intake in European 11-to 12-year-old schoolchildren. Ann Nutr Metab. 2005;49:221–7.

Dewar DL, Lubans DR, Plotnikoff RC, Morgan PJ. Development and evaluation of social cognitive measures related to adolescent dietary behaviors. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:36.

Bell A, Swinburn B. What are the key food groups to target for preventing obesity and improving nutrition in schools? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:258.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cleland V, Worsley A, Crawford D. What are grade 5 and 6 children buying from school canteens and what do parents and teachers think about it? Nutr Diet. 2004;61:145–50.

Rosenkoetter E, Loman DG. Self-efficacy and self-reported dietary behaviors in adolescents at an urban school with no competitive foods. J Sch Nurs. 2015;31:345–52.

Fahlman MM, McCaughtry N, Martin J, Shen B. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in nutrition behaviors: targeted interventions needed. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:10–6.

Bugge AB. Young people's school food styles naughty or nice? Young. 2010;18:223–43.

Kainulainen K, Benn J, Fjellstrom C, Palojoki P. Nordic adolescents' school lunch patterns and their suggestions for making healthy choices at school easier. Appetite. 2012;59:53–62.

Tugault-Lafleur C, Black J, Barr S. Lunch-time food source is associated with school hour and school day diet quality among Canadian children. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;31:96–107.

Jones AC, Hammond D, Reid JL, Leatherdale ST. Where should we eat? Lunch source and dietary measures among youth during the school week. Can J Pract Res. 2015;76:157–65.

Velazquez CE, Black JL, Billette JM, Ahmadi N, Chapman GE. A comparison of dietary practices at or en route to school between elementary and secondary school students in Vancouver. Canada J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:1308–17.

Caraher M, Lloyd S, Mansfield M, Alp C, Brewster Z, Gresham J. Secondary school pupils' food choices around schools in a London borough: fast food and walls of crisps. Appetite. 2016;103:208–20.

Wang YF, Liang HF, Tussing L, Braunschweig C, Caballero B, Flay B. Obesity and related risk factors among low socio-economic status minority students in Chicago. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:927–38.

Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Wing RR. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:842–9.

Savige G, MacFarlane A, Ball K, Worsley A, Crawford D. Snacking behaviours of adolescents and their association with skipping meals. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:36–45

Virtanen M, Kivimäki H, Ervasti J, Oksanen T, Pentti J, Kouvonen A, et al. Fast-food outlets and grocery stores near school and adolescents’ eating habits and overweight in Finland. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25:650–5.

Keski-Rahkonen A, Kaprio J, Rissanen A, Virkkunen M, Rose RJ. Breakfast skipping and health-compromising behaviors in adolescents and adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:842–53.

Rødje K, Clench-Aas J, Van-Roy B, Holmboe O, Müller A. Helseprofil for barn og ungdom i Akershus. Norway: Ungdomsrapporten Lørenskog; 2004.

McLellan L, Rissel C, Donnelly N, Bauman A. Health behaviour and the school environment in New South Wales. Australia Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:611–9.

Wang YF, Caballero B. Resemblance in dietary intakes between urban low-income african-american adolescents and their mothers: the healthy eating and active lifestyles from school to home for kids study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:52–63.

Prattala R. Teenage meal patterns and food choices in a Finnish city. Ecol Food Nutr. 1989;22:285–95.

Darling H, Reeder AI, McGee R, Williams S. Brief report: disposable income, and spending on fast food, alcohol, cigarettes, and gambling by New Zealand secondary school students. J Adolesc. 2006;29:837–43.

Jensen JD, Bere E, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Jan N, Maes L, Manios Y, et al. Micro-level economic factors and incentives in children's energy balance related behaviours findings from the ENERGY European crosssection questionnaire survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:136–48.

Lewis A, Scott AJ. The economic awareness, knowledge and pocket money practices of a sample of UK adolescents: a study of economic socialisation and economic psychology. Citizen Soc Econ Edu. 2000;4:34–46.

Fauth J. Money makes the world go around: European youth and financial socialization. Int J Hum Ecol. 2004;5:23–34.

French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1823.

Johnson F, Wardle J, Griffith J. The adolescent food habits checklist: reliability and validity of a measure of healthy eating behaviour in adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:644.

Stead M, McDermott L, MacKintosh AM, Adamson A. Why healthy eating is bad for young people’s health: identity, belonging and food. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1131–9.

Bugge AB. Lovin'it? A study of youth and the culture of fast food. Food Cult Soc. 2011;14:71–89.

Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:S40–51.

Feunekes GIJ, de Graaf C, Meyboom S, van Staveren WA. Food choice and fat intake of adolescents and adults: associations of intakes within social networks. Prev Med. 1998;27:645–56.

Vepsäläinen H, Mikkilä V, Erkkola M, Broyles ST, Chaput J-P, et al. Association between home and school food environments and dietary patterns among 9–11-year-old children in 12 countries. Int J Obes Suppl. 2015;5:S66.

Woodruff SJ, Hanning RM, McGoldrick K. The influence of physical and social contexts of eating on lunch-time food intake among southern Ontario, Canada, middle school students. J Sch Health. 2010;80:421–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The ESSENS study is a collaborative project between OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University and the public health project Folkehelseforum Øvre Romerike (FØR). We would like to thank all the participants who took part in this study.

The study was supported by internal funds from OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ongoing project work but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Nursing and Health Promotion, Faculty of Health Sciences, OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University, P.O. Box 4, St Olavs plass, 0130, Oslo, Norway

Arthur Chortatos, Laura Terragni, Sigrun Henjum, Marianne Gjertsen & Liv Elin Torheim

Department of Epidemiology, Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA, USA

Mekdes K Gebremariam

Department of Nutrition, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1046 Blindern, N-0317, Oslo, Norway

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AC conducted the data analyses and wrote the first draft of this manuscript. MKG2 designed the study, led the project planning and implementation of the intervention, and participated in data collection and analyses. LT1, SH, MG1, LET2 and MKG2 substantially contributed to the conception, design, and implementation of the study, as well as providing content to the final manuscript. MG1 recruited participants, conducted and transcribed focus group interviews, and contributed to data analyses. All authors have critically read and given final approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Arthur Chortatos .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the responsible institutional body, the Norwegian Social Sciences Data Services, which is the data protection official for research. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents of participating adolescents; adolescents provided assent. School administrators also provided consent for the study.

Consent for publication

‘Not applicable’.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Appendix 1. ESSENS questionnaire relating to food behaviours ESSENS Study. (DOCX 33 kb)

Additional file 2:

Appendix 2. Interview guide for focus group interviews. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 3:

Appendix 3. Interview guide for headmasters and teachers. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Chortatos, A., Terragni, L., Henjum, S. et al. Consumption habits of school canteen and non-canteen users among Norwegian young adolescents: a mixed method analysis. BMC Pediatr 18 , 328 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1299-0

Download citation

Received : 25 January 2018

Accepted : 01 October 2018

Published : 16 October 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1299-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- School lunch

- Adolescents

BMC Pediatrics

ISSN: 1471-2431

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Factors that influence food choices in secondary school canteens: a qualitative study of pupil and staff perspectives.

- 1 Nutrition Innovation Centre for Food and Health, School of Biomedical Sciences, Ulster University, Coleraine, United Kingdom

- 2 Education Authority, Armagh, United Kingdom

Background: Adolescence is recognised as a period of nutritional vulnerability, with evidence indicating that United Kingdom adolescents have suboptimal dietary intakes with many failing to meet dietary recommendations. Additionally, adolescence is a time of transition when they become more independent in their dietary choices and begin to develop their own sense of autonomy and are less reliant on their parent’s guidance, which is reported to lead to less favourable dietary behaviours. Reducing the prevalence of poor dietary intakes and the associated negative health consequences among this population is a public health priority and schools represent an important setting to promote positive dietary behaviours. The aim of this school-based study was to explore the factors and barriers which influence food choices within the school canteen and to identify feasible strategies to promote positive dietary behaviours within this setting.

Methods: Thirteen focus groups with 86 pupils in Year 8 ( n = 37; aged 11–12 years) and Year 9 ( n = 49; aged 12–13 years) in six secondary schools across Northern Ireland, United Kingdom were conducted. Additionally, one-to-one virtual interviews were conducted with 29 school staff [principals/vice-principals ( n = 4); teachers ( n = 17); and caterers ( n = 7)] across 17 secondary schools and an Education Authority (EA) senior staff member ( n = 1). Focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analysed following an inductive thematic approach.

Results: Using the ecological framework, multiple factors were identified which influenced pupils’ selection of food in the school canteen at the individual (e.g., time/convenience), social (e.g., peer influence), physical (e.g., food/beverage placement), and macro environment (e.g., food provision) level. Suggestions for improvement of food choices were also identified at each ecological level: individual (e.g., rewards), social (e.g., pupil-led initiatives), physical (e.g., labelling), and macro environment (e.g., whole-school approaches).

Conclusion: Low-cost and non-labour intensive practical strategies could be employed, including menu and labelling strategies, placement of foods, reviewing pricing policies and whole-school initiatives in developing future dietary interventions to positively enhance adolescents’ food choices in secondary schools.

Introduction

Globally, adolescent overweight and obesity has increased significantly ( 1 ) and is now recognised as one of the most urgent public health challenges ( 2 ). This issue is particularly prevalent within the United Kingdom, with >30% of adolescents (aged 11–15 years) impacted by overweight or obesity ( 3 ). The negative physical ( 4 , 5 ) and psychological ( 4 – 6 ) health implications associated with adolescent obesity are well-documented. Additionally, challenges also exist with reversing adolescent obesity, with 80% of obese adolescents likely to remain obese in adulthood ( 7 ), increasing the risk of further poor health outcomes in later life ( 8 ). Thus, determining effective preventative measures to mitigate the risk of obesity among this population is crucial to improve current and future health and minimise long-term obesity-related medical costs ( 9 ).

Less healthful dietary behaviours during adolescence, such as the overconsumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, can increase short ( 10 ) and long-term ( 11 ) obesity risk. United Kingdom adolescents’ dietary habits are of concern, with The National Diet and Nutrition Survey indicating suboptimal dietary behaviours among this population, including inadequate consumption of fruit and vegetables ( 12 ), low fibre intakes ( 13 ), excessive fat and sugar intakes ( 13 ) and higher energy intake also among those with overweight or obesity ( 14 ). As children transition to adolescents, they can become more susceptible to consuming an unbalanced diet ( 15 ) and dietary behaviours acquired during this period can persist into adult life ( 16 ). Therefore, dietary intervention during adolescence is essential to offset trends of declining dietary quality and establish healthy eating behaviours that can be sustained across the lifespan.

Adolescents are required to spend 190 days each year in school ( 17 ). Given the continuous contact time schools provide to this population, this setting represents a promising environment to deliver dietary interventions ( 18 ). School-based interventions are cost-effective ( 19 ) and offer the opportunity to reach the majority of adolescents, irrespective of socio-economic status or ethnical background ( 20 ). Moreover, adolescents’ consume a substantial proportion of their daily energy intakes in school (up to 1–2 meals per day) ( 21 , 22 ). However, despite consistent efforts to determine the most effective school-based interventions to improve adolescents’ dietary intakes, outcomes remain short-term ( 23 ).

In Northern Ireland (NI), records suggest that more than half of adolescents (54–63%) typically consume school meals (provided by schools) at lunchtime ( 24 ) as opposed to a packed lunch (brought from home) or sourcing items from nearby food outlets. Mandatory food-based standards ( 25 ) are in place in NI schools to ensure pupils have access to a healthy and balanced school meal ( 26 ), which is of particular benefit to those who may have limited access to nutritious food outside school. However, although secondary schools provide healthier options compliant with the school-food standards, many adolescents continue to purchase the less nutritious items from the menu on offer ( 27 ), highlighting the need to explore alternate influential factors on adolescents’ lunchtime food choices. In addition to improved food provision, nutritional education is also compulsory in NI secondary schools (post-primary) for adolescents in Key Stage 3 (aged 11–14 years) ( 28 ), albeit, adolescents’ nutritional knowledge often has minimal impact on their food choices ( 29 ). Thus, identifying additional opportunities within the school-setting to promote positive dietary change is of importance. As pupils progress from primary to secondary education, parental control over their eating behaviours lessens and their propensity towards their dietary decisions become more independent-based ( 15 ). It is therefore pertinent to gain insight into the principal factors influencing adolescents’ school-based food choices as they develop increasing nutritional autonomy during this transitional period to optimise engagement and success of future school-based dietary interventions.

Research suggests that adolescents’ food choices within the school canteen can be influenced by various food-related factors, including available items, quality, appearance, taste, cost, value for money and peer pressure to opt for specific foods and canteen-related factors such as food hygiene, school menu and price displays, queue length and seating availability ( 30 ). More recent work has revealed adolescents’ favour take away items in the school canteen and associate ‘main meals’ as food to be consumed within the home environment ( 31 ).

In order to better understand the multiple levels of influence on adolescents’ food choices, Story et al. ( 32 ) proposed an ecological framework to consider their eating behaviours under four broad levels of influence to include individual (intrapersonal), social environmental (interpersonal), physical environmental, and macro level to aid in the design of appropriate nutrition interventions targeted at this population.

The difficulties associated with changing health behaviours are well recognised ( 33 ). When designing interventions, early involvement of stakeholders and the target user is recommended ( 34 ). In addition, although often under-utilised, qualitative research methodologies may assist in informing and optimising the design of interventions ( 35 ). Gaining further understanding of NI adolescents’ perspectives on the factors influencing their food choices within school and their suggestions on how best to address these factors through school-based strategies is needed if effective interventions to enhance positive dietary behaviours in this population are to be achieved. Additionally, a paucity of information exists on United Kingdom school staff’s perspectives on adolescents’ school-based food choices and their recommendations for improvement, limiting the ability for comparisons between key stakeholder groups to be examined. Furthermore, to aid in successful intervention design, consulting with school staff may provide researchers with a better understanding of any existing implementation practicalities to consider, such as schools’ academic priorities, available resources and the need to avoid over-burdening staff ( 36 ).

The aim of this study was to explore the primary factors influencing adolescents’ food choices within the school canteen environment from the pupil and school staff perspective. Additionally, a secondary aim was to identify feasible strategies to encourage healthful food choices amongst adolescents within the school-setting.

Study design

Qualitative research methods were selected to provide insight into the complexity of individuals’ food-related behaviours ( 37 ), in addition to their interactive nature to facilitate in-depth exploration of topics raised that is less possible with quantitative surveys ( 38 , 39 ). Focus groups with pupils and one-to-one interviews with school staff were conducted to capture participants’ perspectives, attitudes, and experiences ( 40 , 41 ). The reporting of this study is aligned with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ; Supplementary Table S1 ) ( 42 ). This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by Ulster University’s Research Ethics Committee (FCBMS-20-016-A; REC/20/0031). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents/ guardians.

Sample selection and recruitment

School pupils.

Year 8 (aged 11–12 years) and Year 9 (aged 12–13 years) pupils in seven purposively sampled ( 43 ) mixed-gender secondary schools in NI were invited to take part in this study. Year 8 (aged 11–12 years) and year 9 (aged 12–13 years) pupils were the focus as they had recently transitioned to secondary school and had become exposed to making independent food choices in the school canteen. Pupils who purchased food in the school canteen regularly (at least once each week) were eligible to participate. Schools were contacted via email or telephone and following agreement from the school principal, information sheets, assent and consent forms were distributed by a senior teacher to eligible pupils and asked to discuss with their parents/guardians. Participants who returned completed assent and consent forms were selected by a senior teacher to participate in the focus group.

School staff

A purposive sample ( 43 ) of school staff from a range of socio-economic (assessed using number of free school meals) and geographically diverse mixed-gender secondary schools ( n = 17) across NI were invited to participate in this study. All grades of staff were eligible to participate including principals/vice principals and teaching staff from a range of subject disciplines. School catering staff included supervisors and caterers. Additionally, as the EA has responsibility for school meal provision in a large proportion of NI secondary schools, one senior EA staff member was invited to participate. School staff were contacted via email or telephone, and following agreement, information sheets and consent forms were distributed.

Data collection

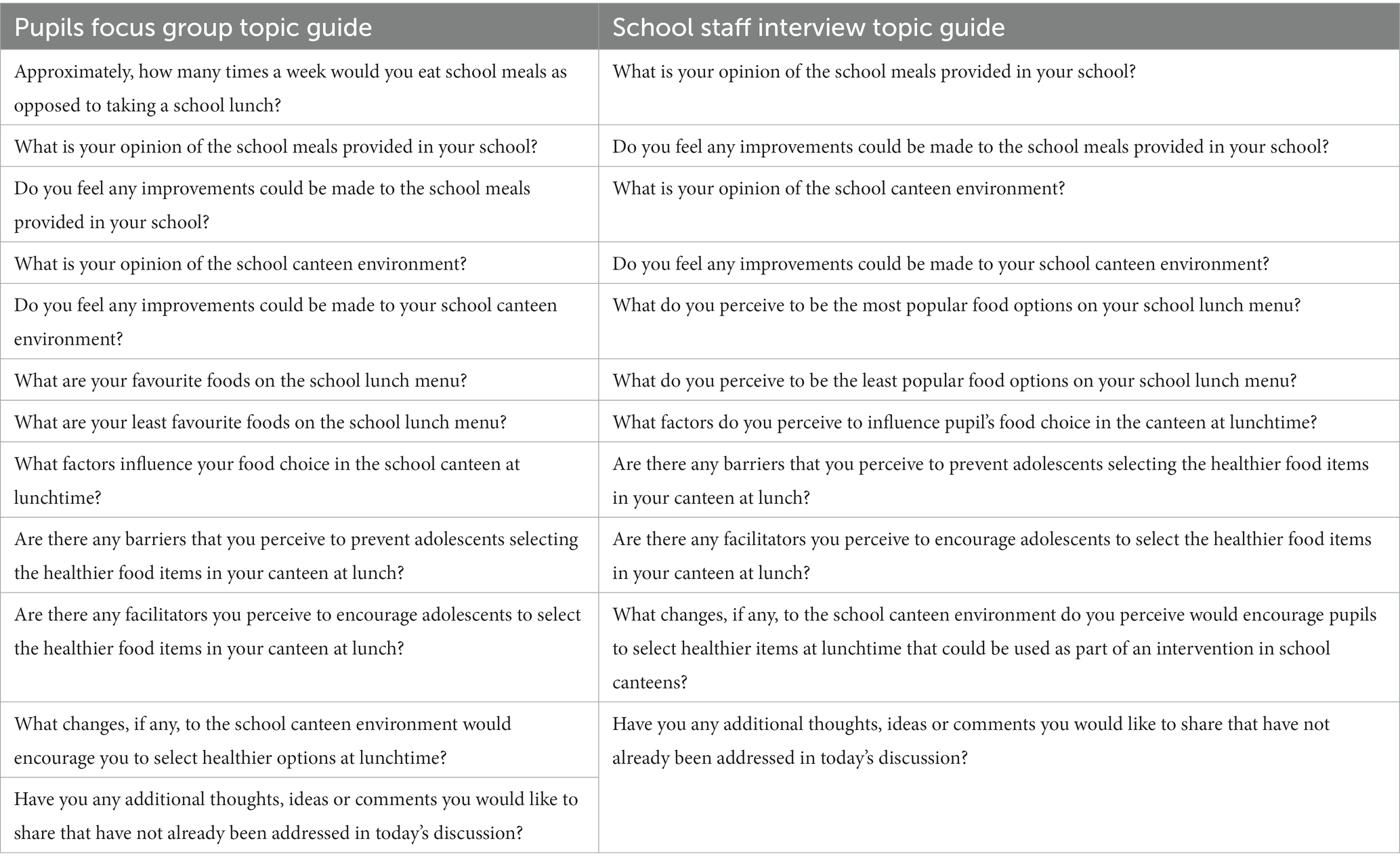

Pupils participated in mixed-gender focus groups and staff in one-to-one interviews, which were conducted independently by a researcher trained in qualitative research (L.D.D, PhD researcher, not affiliated with schools). Similar semi-structured discussion guides were used for the focus groups and interviews ( Table 1 ) to ensure consistency and facilitate comparability between the pupils’ and staff’s perspectives. All focus groups and interview discussions were facilitated by the researcher using the topic guide to explore key issues. To enhance interaction and active listening during the discussions, notes were made directly after each session to enrich the data collected ( 40 ). Focus groups and interviews were undertaken until data saturation had been reached ( 44 ).

Table 1 . Semi-structured discussion guide for pupils focus groups and school staff interviews.

Mixed-gender focus groups of 5–8 pupils were conducted between May and June 2021 within the school (classroom or hall) and during school hours under observation from a senior teacher. All pupils were reminded prior to commencing the focus groups that the information they provided would remain anonymous and would not be shared with their parents or school staff. The topic guide ( Table 1 ) was designed and developed based on a review of the area and pilot tested on a small group of Year 8 pupils in different schools to test the questions for level of comprehension to optimise clarity of questions ( 45 ). Focus group sessions were on average 30 min duration (range 12–43 min).

One-to-one interviews were conducted remotely with school staff via Microsoft Teams or by telephone call at a suitable time for each participant between October and December 2020. Interview questions were pilot tested with one teacher in a different school to test suitability of questions. Interviews took on average 30 min (range 9–57 min).

Data analysis

Focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 12 Pro Software (QSR International) for data management and analysed following the six phases of reflexive thematic analysis using an inductive approach ( 46 ). Codes were independently applied to quotes throughout each transcript by a member of the research team (L.D.D). To minimise the risk of bias and ensure correct interpretation of quotes, transcripts and codes were critically reviewed, discussed and confirmed by the research team (A.J.H and A.M.G). Quotes representing similar views were then clustered together and assigned initial sub-themes (L.D.D), which were reviewed by the research team (A.J.H and A.M.G) and refined before reaching consensus on the potential sub-themes. Each sub-theme was then mapped to each level of the ecological model, namely: individual (intrapersonal), social environment (interpersonal), physical environment, and macro environment ( 32 ). Quotes that were most reflective of the sub-themes were selected for inclusion.

Participant and school characteristics

Of the seven purposively sampled schools, six schools expressed an interest in participating and one did not respond to the study invitation. 86 pupils participated in 13 focus groups across the six schools ( n = 4 urban; n = 2 rural) throughout three different district council areas in NI, with six focus groups undertaken with Year 8 pupils ( n = 24 female; n = 13 males) and seven with Year 9 pupils ( n = 28 female; n = 21 males). All six schools were co-educational and mixed-gender. Free school meal entitlement across the schools ranged from 21 to 53%.

Of the 35 participants who received initial invitations, 29 participated in this study (four did not respond to the study invitation; one did not return the consent form; one was excluded as they did not have recent experience in a secondary school). The final sample of 29 (24 females, 5 males) comprised principals ( n = 2), vice-principals ( n = 2), teachers ( n = 17), catering staff ( n = 7) sampled across 17 secondary schools, and a senior staff member ( n = 1) in the EA. The schools were in urban ( n = 14) and rural ( n = 3) environments located within eight of 11 district council areas in NI. 16 schools were co-educational (mixed-gender) with one school being female only. Free school meal entitlement in these schools ranged from 7 to 54%.

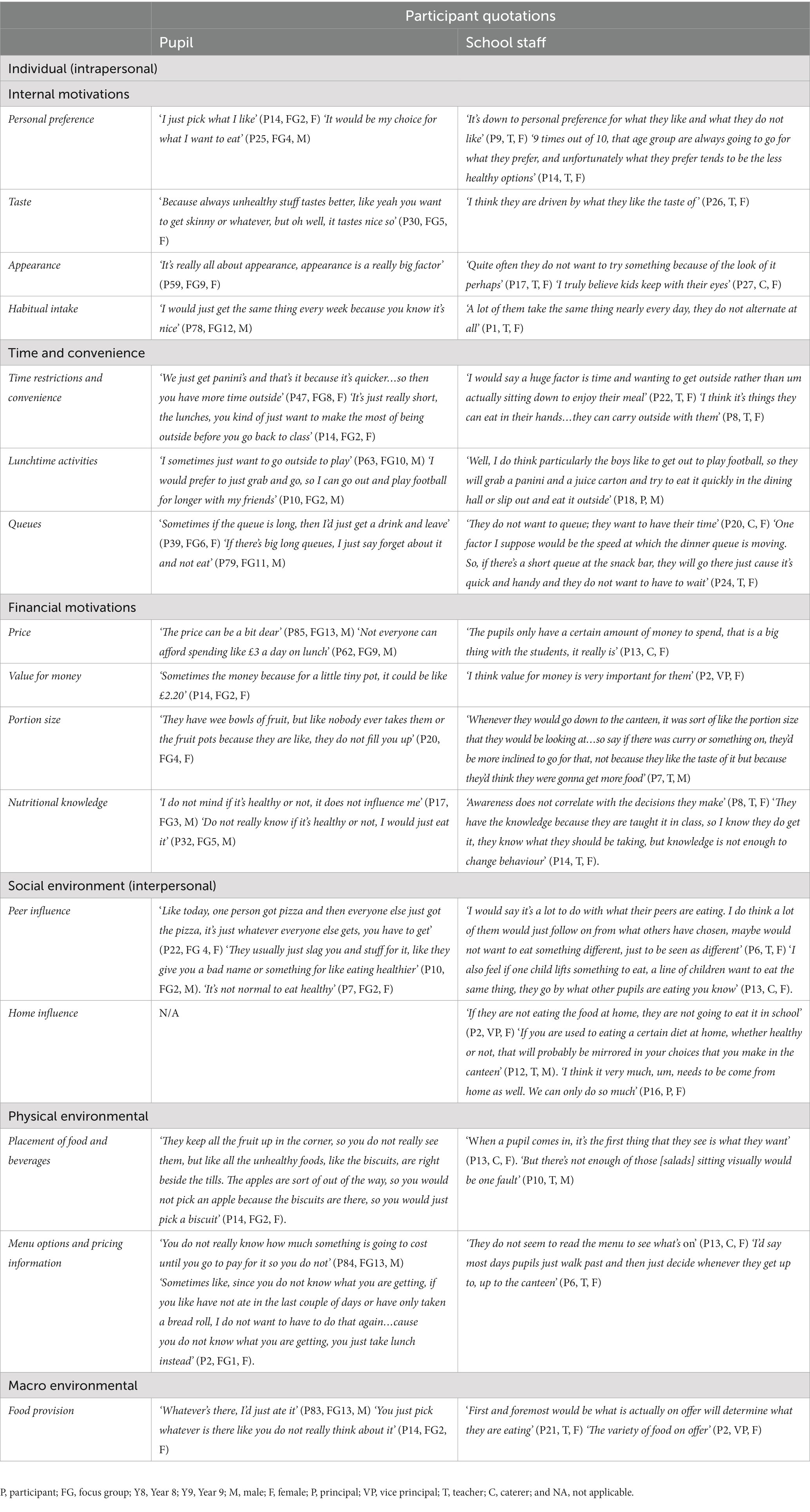

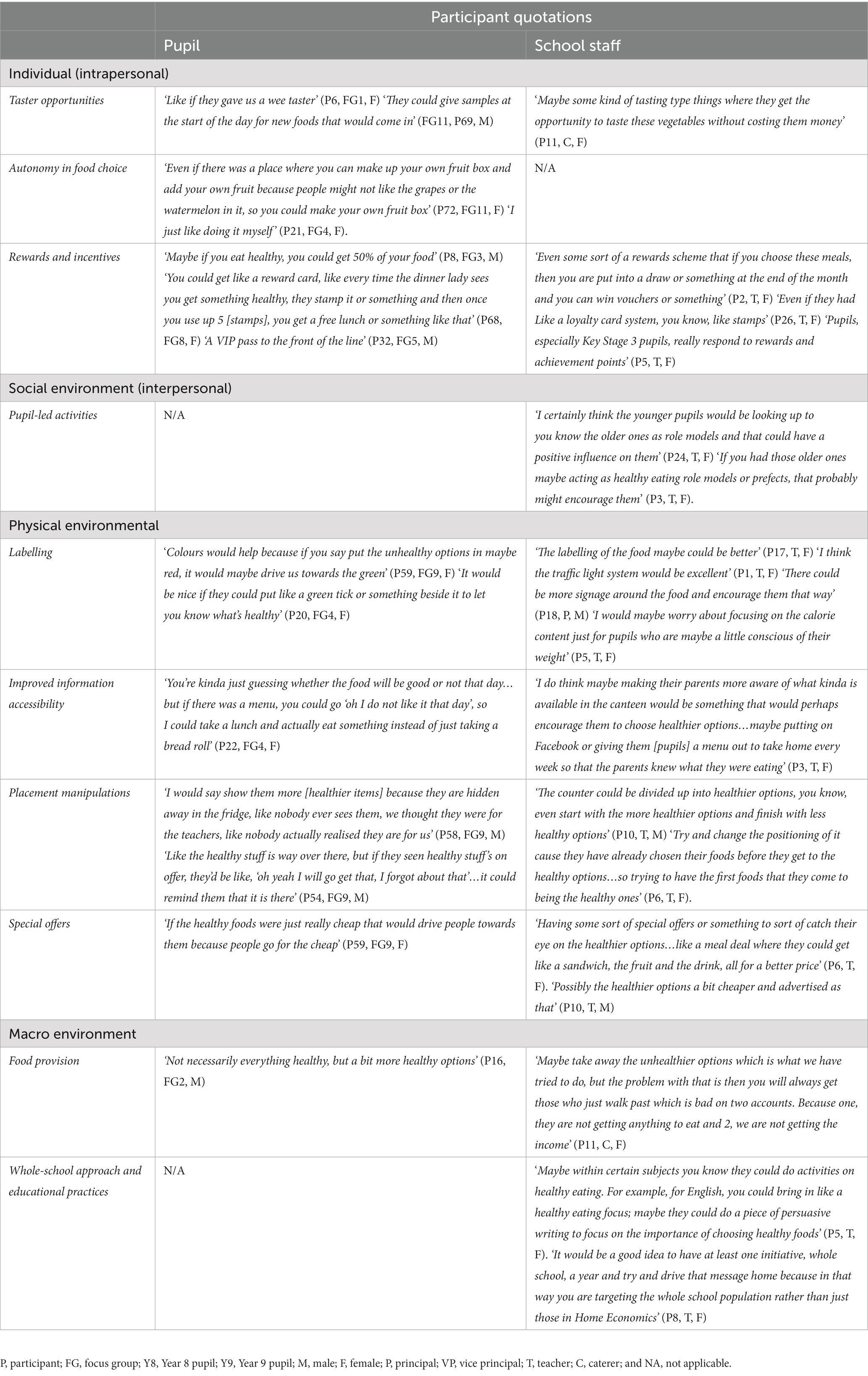

The key sub-themes identified from the pupils’ and staff’s responses and exemplar quotes are reported in Tables 2 , 3 using under the four levels of the ecological framework: individual (intrapersonal), social environment (interpersonal), physical environment, and macro environment ( 32 ).

Table 2 . Pupils’ and school staff’s perceptions on the influences of adolescents’ dietary choices in the school canteen.

Table 3 . Pupils’ and school staff’s views on strategies to encourage selecting healthier options in the school canteen.

Influences on pupils’ food choices in the school canteen

Individual (intrapersonal).

Exemplar quotes to illustrate the following sub-themes are shown in Table 2 .

Internal motivations

Pupils’ personal preferences, in addition to taste, appearance and habitual intakes, were important factors that influence their food choices in the school canteen. These factors often took precedence over the healthiness of the food items on offer, with many pupils commenting that options which were perceived to be less healthy were more tasteful. Pupils’ also commented that if they did not like the choices available, they may have not have lunch in the canteen that day.

‘I just pick what I like’ (P14, FG2, F)

School staff had similar perceptions regarding personal preferences and reinforced that pupils were more likely to select items which were less healthy. School staff also reported that the appearance, familiarity and taste of the food were important when selecting items in the canteen and that these factors may act as barriers to pupils choosing alternate food options.

Time and convenience

Many pupils identified time restrictions as being a major barrier when making food choices as they have limited time for lunch break and many preferred convenient, ‘grab-and-go’ options as they preferred to maximise their free time with peers and participate in lunchtime activities. Additionally, the length of queue in the canteen was also commonly cited, with pupils’ opting for meals which had shorter queues, which may influence choice and possibly discourage pupils from eating in the canteen or skipping their lunchtime meal.

‘If there’s big long queues, I just say forget it and not eat’ (P79, FG11, M)

This was similar to school staff’s views, who suggested that the queues were a factor which influenced food choices in the canteen and this issue was identified to be of greater importance for male pupils who prioritised socialising outside at lunchtime and were less likely to be waiting in queues. School staff also described how in more recent years, pupils’ choices have gradually changed over the years from selecting more traditional sit-down meals in the canteen to more convenient, portable and on-the-go options.

Financial motivations

Both pupils and staff commonly reported that price, value for money and portion size influenced food choice. For example, fruit options were reported to be of a small portion size and lower satiety value, thus, not good value for money, and therefore limited the selection of these items. Additionally, pupils reported that food items were expensive, with one pupil noting that on occasions, money allocated from ‘free school meal entitlement’ was insufficient to cover the cost of lunch. Financial motivations were identified as a key theme reported by five out of six schools regardless of whether the school was located in an area deemed to be rural or urban.

‘Not everyone can afford spending like £3 a day on lunch’ (P62, FG9, M)

School staff also commented that they believed that pupils had a budget to purchase lunch and that the cost of food items and value for money was an important factor in their choice of food. It was noted by staff that dissatisfaction with food choice for value for money was perceived to increase the number of pupils opting for a packed lunch. School staff also commented that male pupils prioritise purchasing food which seemed to have larger portion sizes.

Nutritional knowledge

Pupils’ reported different views on the importance of understanding the nutritional value and composition of foods and whether the food was a healthy choice. Some pupils stated that they were unaware of which foods and meals were healthier, whereas, others were very aware of the healthier options. Both groups stated that this would not be a primary factor to influence their food choices.

‘I do not mind if its healthy or not, it does not influence me’ (P17, FG3, M)