BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES MAJOR

Senior thesis examples.

Graduating seniors in Biological Sciences have the option of submitting a senior thesis for consideration for Honors and Research Prizes . Below are some examples of particularly outstanding theses from recent years (pdf):

Sledd Thesis

- Utility Menu

- Writing Center

- Writing Program

- Senior Thesis Writing Guides

The senior thesis is typically the most challenging writing project undertaken by undergraduate students. The writing guides below aim to introduce students both to the specific methods and conventions of writing original research in their area of concentration and to effective writing process.

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

- Course-Specific Writing Guides

- Disciplinary Writing Guides

- Gen Ed Writing Guides

- Utility Menu

- ARC Scheduler

- Student Employment

- Senior Theses

Doing a senior thesis is an exciting enterprise. It’s often the first time students are engaging in truly original research and trying to develop a significant contribution to a field of inquiry. But as joyful as an independent research process can be, you don’t have to go it alone. It’s important to have support as you navigate such a large endeavor, and the ARC is here to offer one of those layers of support.

Whether or not to write a senior thesis is just the first in a long line of questions thesis writers need to consider. In addition to questions about the topic and scope of your thesis, there are questions about timing, schedule, and support. For example, if you are collecting data, when should data collection start and when should it be completed? What kind of schedule will you write on? How will you work with your adviser? Do you want to meet with your adviser about your progress once a month? Once a week? What other resources can you turn to for information, feedback, and support?

Even though there is a lot to think about and a lot to do, doing a thesis really can be an enjoyable experience! Keep reminding yourself why you chose this topic and why you care about it.

Tips for Tackling Big Projects:

Break the process down into manageable chunks.

- When you’re approaching a big project, it can seem overwhelming to look at the whole thing at once, so it’s essential to identify the smaller steps that will move you towards the completed project.

- Your adviser is best suited to help you break down the thesis process with field-specific advice.

- If you need to refine the breakdown further so it makes sense for you, schedule an appointment with an Academic Coach . An academic coach can help you think through the steps in a way that works for you.

Schedule brief writing sessions at regular times.

- Pre-determine the time, place, and duration.

- Keep it short (15 to 60 minutes).

- Have a clear and reasonable goal for each writing session.

- Make it a regular event (every day, every other day, MWF).

- time is not wasted deciding to write if it’s already in your calendar;

- keeping sessions short reduces the competition from other tasks that are not getting done;

- having an achievable goal for each session provides a sense of accomplishment (a reward for your work);

- writing regularly can turn into a productive habit.

Create accountability structures.

- In addition to having a clear goal for each writing session, it's important to have clear goals for each week and to find someone to communicate these goals to, such as your adviser, a “thesis buddy,” your roommate, etc. Communicating your goals and progress to someone else creates a useful sense of accountability.

- If your adviser is not the person you are communicating your progress to on a weekly basis, then request to set up a structure with your adviser that requires you to check in at less frequent but regular intervals.

- Commit to attending Accountability Hours at the ARC on the same day every week. Making that commitment will add both social support and structure to your week. Use the ARC Scheduler to register for Accountability Hours.

- Set up an accountability group in your department or with thesis writers from different departments.

Create feedback structures.

- It’s important to have a means for getting consistent feedback on your work and to get that feedback early. Work on large projects often lacks the feeling of completeness, so don’t wait for a whole section (and certainly not the whole thesis) to feel “done” before you get feedback on it!

- Your thesis adviser is typically the person best positioned to give you feedback on your research and writing, so communicate with your adviser about how and how often you would like to get feedback.

- If your adviser isn’t able to give you feedback with the frequency you’d like, then fill in the gaps by creating a thesis writing group or exploring if there is already a writing group in your department or lab.

- The Harvard College Writing Center is a great resource for thesis feedback. Writing Center Senior Thesis Tutors can provide feedback on the structure, argument, and clarity of your writing and help with mapping out your writing plan. Visit the Writing Center website to schedule an appointment with a thesis tutor .

Accept that there will be some anxious moments.

- To reduce this source of anxiety, try keeping a separate document where you jot down ideas on how your research questions or central argument might be clarifying or changing as you research and write. Doing this will enable you to stay focused on the section you are working on and to stop worrying about forgetting the new ideas that are emerging.

- You might feel anxious when you realize that you need to update your argument in response to the evidence you have gathered or the new thinking your writing has unleashed. Know that that is OK. Research and writing are iterative processes – new ideas and new ways of thinking are what makes progress possible.

- Breaking down big projects into manageable chunks and mapping out a schedule for working through each chunk is one way to reduce this source of anxiety. It’s reassuring to know you are working towards the end even if you cannot quite see how it will turn out.

- It may be that your thesis or dissertation never truly feels “done” to you, but that’s okay. Academic inquiry is an ongoing endeavor.

Focus on what works for you.

- Just because your roommate wrote 10 pages in a day doesn’t mean that’s the right pace or strategy for you.

- If you are having trouble figuring out what works for you, use the ARC Scheduler to make an appointment with an Academic Coach , who can help you come up with daily, weekly, and semester-long plans.

Use your resources.

- There’s a lot of the thesis writing process that has to be done independently, but there are also a lot of free resources at Harvard to help you do the work.

- If you’re having trouble finding a source, email your question or set up a research consult via Ask a Librarian .

- If you’re looking for additional feedback or help with any aspect of writing, contact the Harvard College Writing Center . The Writing Center has Senior Thesis Tutors who will read drafts of your thesis (more typically, parts of your thesis) in advance and meet with you individually to talk about structure, argument, clear writing, and mapping out your writing plan.

- If you need help with breaking down your project or setting up a schedule for the week, the semester, or until the deadline, use the ARC Scheduler to make an appointment with an Academic Coach .

- If you would like an accountability structure for social support and to keep yourself on track, come to Accountability Hours at the ARC.

Accordion style

- Assessing Your Understanding

- Building Your Academic Support System

- Common Class Norms

- Effective Learning Practices

- First-Year Students

- How to Prepare for Class

- Interacting with Instructors

- Know and Honor Your Priorities

- Memory and Attention

- Minimizing Zoom Fatigue

- Note-taking

- Office Hours

- Perfectionism

- Scheduling Time

- Study Groups

- Tackling STEM Courses

- Test Anxiety

Honors Theses

What this handout is about.

Writing a senior honors thesis, or any major research essay, can seem daunting at first. A thesis requires a reflective, multi-stage writing process. This handout will walk you through those stages. It is targeted at students in the humanities and social sciences, since their theses tend to involve more writing than projects in the hard sciences. Yet all thesis writers may find the organizational strategies helpful.

Introduction

What is an honors thesis.

That depends quite a bit on your field of study. However, all honors theses have at least two things in common:

- They are based on students’ original research.

- They take the form of a written manuscript, which presents the findings of that research. In the humanities, theses average 50-75 pages in length and consist of two or more chapters. In the social sciences, the manuscript may be shorter, depending on whether the project involves more quantitative than qualitative research. In the hard sciences, the manuscript may be shorter still, often taking the form of a sophisticated laboratory report.

Who can write an honors thesis?

In general, students who are at the end of their junior year, have an overall 3.2 GPA, and meet their departmental requirements can write a senior thesis. For information about your eligibility, contact:

- UNC Honors Program

- Your departmental administrators of undergraduate studies/honors

Why write an honors thesis?

Satisfy your intellectual curiosity This is the most compelling reason to write a thesis. Whether it’s the short stories of Flannery O’Connor or the challenges of urban poverty, you’ve studied topics in college that really piqued your interest. Now’s your chance to follow your passions, explore further, and contribute some original ideas and research in your field.

Develop transferable skills Whether you choose to stay in your field of study or not, the process of developing and crafting a feasible research project will hone skills that will serve you well in almost any future job. After all, most jobs require some form of problem solving and oral and written communication. Writing an honors thesis requires that you:

- ask smart questions

- acquire the investigative instincts needed to find answers

- navigate libraries, laboratories, archives, databases, and other research venues

- develop the flexibility to redirect your research if your initial plan flops

- master the art of time management

- hone your argumentation skills

- organize a lengthy piece of writing

- polish your oral communication skills by presenting and defending your project to faculty and peers

Work closely with faculty mentors At large research universities like Carolina, you’ve likely taken classes where you barely got to know your instructor. Writing a thesis offers the opportunity to work one-on-one with a with faculty adviser. Such mentors can enrich your intellectual development and later serve as invaluable references for graduate school and employment.

Open windows into future professions An honors thesis will give you a taste of what it’s like to do research in your field. Even if you’re a sociology major, you may not really know what it’s like to be a sociologist. Writing a sociology thesis would open a window into that world. It also might help you decide whether to pursue that field in graduate school or in your future career.

How do you write an honors thesis?

Get an idea of what’s expected.

It’s a good idea to review some of the honors theses other students have submitted to get a sense of what an honors thesis might look like and what kinds of things might be appropriate topics. Look for examples from the previous year in the Carolina Digital Repository. You may also be able to find past theses collected in your major department or at the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library. Pay special attention to theses written by students who share your major.

Choose a topic

Ideally, you should start thinking about topics early in your junior year, so you can begin your research and writing quickly during your senior year. (Many departments require that you submit a proposal for an honors thesis project during the spring of your junior year.)

How should you choose a topic?

- Read widely in the fields that interest you. Make a habit of browsing professional journals to survey the “hot” areas of research and to familiarize yourself with your field’s stylistic conventions. (You’ll find the most recent issues of the major professional journals in the periodicals reading room on the first floor of Davis Library).

- Set up appointments to talk with faculty in your field. This is a good idea, since you’ll eventually need to select an advisor and a second reader. Faculty also can help you start narrowing down potential topics.

- Look at honors theses from the past. The North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library holds UNC honors theses. To get a sense of the typical scope of a thesis, take a look at a sampling from your field.

What makes a good topic?

- It’s fascinating. Above all, choose something that grips your imagination. If you don’t, the chances are good that you’ll struggle to finish.

- It’s doable. Even if a topic interests you, it won’t work out unless you have access to the materials you need to research it. Also be sure that your topic is narrow enough. Let’s take an example: Say you’re interested in the efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s and early 1980s. That’s a big topic that probably can’t be adequately covered in a single thesis. You need to find a case study within that larger topic. For example, maybe you’re particularly interested in the states that did not ratify the ERA. Of those states, perhaps you’ll select North Carolina, since you’ll have ready access to local research materials. And maybe you want to focus primarily on the ERA’s opponents. Beyond that, maybe you’re particularly interested in female opponents of the ERA. Now you’ve got a much more manageable topic: Women in North Carolina Who Opposed the ERA in the 1970s and 1980s.

- It contains a question. There’s a big difference between having a topic and having a guiding research question. Taking the above topic, perhaps your main question is: Why did some women in North Carolina oppose the ERA? You will, of course, generate other questions: Who were the most outspoken opponents? White women? Middle-class women? How did they oppose the ERA? Public protests? Legislative petitions? etc. etc. Yet it’s good to start with a guiding question that will focus your research.

Goal-setting and time management

The senior year is an exceptionally busy time for college students. In addition to the usual load of courses and jobs, seniors have the daunting task of applying for jobs and/or graduate school. These demands are angst producing and time consuming If that scenario sounds familiar, don’t panic! Do start strategizing about how to make a time for your thesis. You may need to take a lighter course load or eliminate extracurricular activities. Even if the thesis is the only thing on your plate, you still need to make a systematic schedule for yourself. Most departments require that you take a class that guides you through the honors project, so deadlines likely will be set for you. Still, you should set your own goals for meeting those deadlines. Here are a few suggestions for goal setting and time management:

Start early. Keep in mind that many departments will require that you turn in your thesis sometime in early April, so don’t count on having the entire spring semester to finish your work. Ideally, you’ll start the research process the semester or summer before your senior year so that the writing process can begin early in the fall. Some goal-setting will be done for you if you are taking a required class that guides you through the honors project. But any substantive research project requires a clear timetable.

Set clear goals in making a timetable. Find out the final deadline for turning in your project to your department. Working backwards from that deadline, figure out how much time you can allow for the various stages of production.

Here is a sample timetable. Use it, however, with two caveats in mind:

- The timetable for your thesis might look very different depending on your departmental requirements.

- You may not wish to proceed through these stages in a linear fashion. You may want to revise chapter one before you write chapter two. Or you might want to write your introduction last, not first. This sample is designed simply to help you start thinking about how to customize your own schedule.

Sample timetable

Avoid falling into the trap of procrastination. Once you’ve set goals for yourself, stick to them! For some tips on how to do this, see our handout on procrastination .

Consistent production

It’s a good idea to try to squeeze in a bit of thesis work every day—even if it’s just fifteen minutes of journaling or brainstorming about your topic. Or maybe you’ll spend that fifteen minutes taking notes on a book. The important thing is to accomplish a bit of active production (i.e., putting words on paper) for your thesis every day. That way, you develop good writing habits that will help you keep your project moving forward.

Make yourself accountable to someone other than yourself

Since most of you will be taking a required thesis seminar, you will have deadlines. Yet you might want to form a writing group or enlist a peer reader, some person or people who can help you stick to your goals. Moreover, if your advisor encourages you to work mostly independently, don’t be afraid to ask them to set up periodic meetings at which you’ll turn in installments of your project.

Brainstorming and freewriting

One of the biggest challenges of a lengthy writing project is keeping the creative juices flowing. Here’s where freewriting can help. Try keeping a small notebook handy where you jot down stray ideas that pop into your head. Or schedule time to freewrite. You may find that such exercises “free” you up to articulate your argument and generate new ideas. Here are some questions to stimulate freewriting.

Questions for basic brainstorming at the beginning of your project:

- What do I already know about this topic?

- Why do I care about this topic?

- Why is this topic important to people other than myself

- What more do I want to learn about this topic?

- What is the main question that I am trying to answer?

- Where can I look for additional information?

- Who is my audience and how can I reach them?

- How will my work inform my larger field of study?

- What’s the main goal of my research project?

Questions for reflection throughout your project:

- What’s my main argument? How has it changed since I began the project?

- What’s the most important evidence that I have in support of my “big point”?

- What questions do my sources not answer?

- How does my case study inform or challenge my field writ large?

- Does my project reinforce or contradict noted scholars in my field? How?

- What is the most surprising finding of my research?

- What is the most frustrating part of this project?

- What is the most rewarding part of this project?

- What will be my work’s most important contribution?

Research and note-taking

In conducting research, you will need to find both primary sources (“firsthand” sources that come directly from the period/events/people you are studying) and secondary sources (“secondhand” sources that are filtered through the interpretations of experts in your field.) The nature of your research will vary tremendously, depending on what field you’re in. For some general suggestions on finding sources, consult the UNC Libraries tutorials . Whatever the exact nature of the research you’re conducting, you’ll be taking lots of notes and should reflect critically on how you do that. Too often it’s assumed that the research phase of a project involves very little substantive writing (i.e., writing that involves thinking). We sit down with our research materials and plunder them for basic facts and useful quotations. That mechanical type of information-recording is important. But a more thoughtful type of writing and analytical thinking is also essential at this stage. Some general guidelines for note-taking:

First of all, develop a research system. There are lots of ways to take and organize your notes. Whether you choose to use note cards, computer databases, or notebooks, follow two cardinal rules:

- Make careful distinctions between direct quotations and your paraphrasing! This is critical if you want to be sure to avoid accidentally plagiarizing someone else’s work. For more on this, see our handout on plagiarism .

- Record full citations for each source. Don’t get lazy here! It will be far more difficult to find the proper citation later than to write it down now.

Keeping those rules in mind, here’s a template for the types of information that your note cards/legal pad sheets/computer files should include for each of your sources:

Abbreviated subject heading: Include two or three words to remind you of what this sources is about (this shorthand categorization is essential for the later sorting of your sources).

Complete bibliographic citation:

- author, title, publisher, copyright date, and page numbers for published works

- box and folder numbers and document descriptions for archival sources

- complete web page title, author, address, and date accessed for online sources

Notes on facts, quotations, and arguments: Depending on the type of source you’re using, the content of your notes will vary. If, for example, you’re using US Census data, then you’ll mainly be writing down statistics and numbers. If you’re looking at someone else’s diary, you might jot down a number of quotations that illustrate the subject’s feelings and perspectives. If you’re looking at a secondary source, you’ll want to make note not just of factual information provided by the author but also of their key arguments.

Your interpretation of the source: This is the most important part of note-taking. Don’t just record facts. Go ahead and take a stab at interpreting them. As historians Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff insist, “A note is a thought.” So what do these thoughts entail? Ask yourself questions about the context and significance of each source.

Interpreting the context of a source:

- Who wrote/created the source?

- When, and under what circumstances, was it written/created?

- Why was it written/created? What was the agenda behind the source?

- How was it written/created?

- If using a secondary source: How does it speak to other scholarship in the field?

Interpreting the significance of a source:

- How does this source answer (or complicate) my guiding research questions?

- Does it pose new questions for my project? What are they?

- Does it challenge my fundamental argument? If so, how?

- Given the source’s context, how reliable is it?

You don’t need to answer all of these questions for each source, but you should set a goal of engaging in at least one or two sentences of thoughtful, interpretative writing for each source. If you do so, you’ll make much easier the next task that awaits you: drafting.

The dread of drafting

Why do we often dread drafting? We dread drafting because it requires synthesis, one of the more difficult forms of thinking and interpretation. If you’ve been free-writing and taking thoughtful notes during the research phase of your project, then the drafting should be far less painful. Here are some tips on how to get started:

Sort your “evidence” or research into analytical categories:

- Some people file note cards into categories.

- The technologically-oriented among us take notes using computer database programs that have built-in sorting mechanisms.

- Others cut and paste evidence into detailed outlines on their computer.

- Still others stack books, notes, and photocopies into topically-arranged piles.There is not a single right way, but this step—in some form or fashion—is essential!

If you’ve been forcing yourself to put subject headings on your notes as you go along, you’ll have generated a number of important analytical categories. Now, you need to refine those categories and sort your evidence. Everyone has a different “sorting style.”

Formulate working arguments for your entire thesis and individual chapters. Once you’ve sorted your evidence, you need to spend some time thinking about your project’s “big picture.” You need to be able to answer two questions in specific terms:

- What is the overall argument of my thesis?

- What are the sub-arguments of each chapter and how do they relate to my main argument?

Keep in mind that “working arguments” may change after you start writing. But a senior thesis is big and potentially unwieldy. If you leave this business of argument to chance, you may end up with a tangle of ideas. See our handout on arguments and handout on thesis statements for some general advice on formulating arguments.

Divide your thesis into manageable chunks. The surest road to frustration at this stage is getting obsessed with the big picture. What? Didn’t we just say that you needed to focus on the big picture? Yes, by all means, yes. You do need to focus on the big picture in order to get a conceptual handle on your project, but you also need to break your thesis down into manageable chunks of writing. For example, take a small stack of note cards and flesh them out on paper. Or write through one point on a chapter outline. Those small bits of prose will add up quickly.

Just start! Even if it’s not at the beginning. Are you having trouble writing those first few pages of your chapter? Sometimes the introduction is the toughest place to start. You should have a rough idea of your overall argument before you begin writing one of the main chapters, but you might find it easier to start writing in the middle of a chapter of somewhere other than word one. Grab hold where you evidence is strongest and your ideas are clearest.

Keep up the momentum! Assuming the first draft won’t be your last draft, try to get your thoughts on paper without spending too much time fussing over minor stylistic concerns. At the drafting stage, it’s all about getting those ideas on paper. Once that task is done, you can turn your attention to revising.

Peter Elbow, in Writing With Power, suggests that writing is difficult because it requires two conflicting tasks: creating and criticizing. While these two tasks are intimately intertwined, the drafting stage focuses on creating, while revising requires criticizing. If you leave your revising to the last minute, then you’ve left out a crucial stage of the writing process. See our handout for some general tips on revising . The challenges of revising an honors thesis may include:

Juggling feedback from multiple readers

A senior thesis may mark the first time that you have had to juggle feedback from a wide range of readers:

- your adviser

- a second (and sometimes third) faculty reader

- the professor and students in your honors thesis seminar

You may feel overwhelmed by the prospect of incorporating all this advice. Keep in mind that some advice is better than others. You will probably want to take most seriously the advice of your adviser since they carry the most weight in giving your project a stamp of approval. But sometimes your adviser may give you more advice than you can digest. If so, don’t be afraid to approach them—in a polite and cooperative spirit, of course—and ask for some help in prioritizing that advice. See our handout for some tips on getting and receiving feedback .

Refining your argument

It’s especially easy in writing a lengthy work to lose sight of your main ideas. So spend some time after you’ve drafted to go back and clarify your overall argument and the individual chapter arguments and make sure they match the evidence you present.

Organizing and reorganizing

Again, in writing a 50-75 page thesis, things can get jumbled. You may find it particularly helpful to make a “reverse outline” of each of your chapters. That will help you to see the big sections in your work and move things around so there’s a logical flow of ideas. See our handout on organization for more organizational suggestions and tips on making a reverse outline

Plugging in holes in your evidence

It’s unlikely that you anticipated everything you needed to look up before you drafted your thesis. Save some time at the revising stage to plug in the holes in your research. Make sure that you have both primary and secondary evidence to support and contextualize your main ideas.

Saving time for the small stuff

Even though your argument, evidence, and organization are most important, leave plenty of time to polish your prose. At this point, you’ve spent a very long time on your thesis. Don’t let minor blemishes (misspellings and incorrect grammar) distract your readers!

Formatting and final touches

You’re almost done! You’ve researched, drafted, and revised your thesis; now you need to take care of those pesky little formatting matters. An honors thesis should replicate—on a smaller scale—the appearance of a dissertation or master’s thesis. So, you need to include the “trappings” of a formal piece of academic work. For specific questions on formatting matters, check with your department to see if it has a style guide that you should use. For general formatting guidelines, consult the Graduate School’s Guide to Dissertations and Theses . Keeping in mind the caveat that you should always check with your department first about its stylistic guidelines, here’s a brief overview of the final “finishing touches” that you’ll need to put on your honors thesis:

- Honors Thesis

- Name of Department

- University of North Carolina

- These parts of the thesis will vary in format depending on whether your discipline uses MLA, APA, CBE, or Chicago (also known in its shortened version as Turabian) style. Whichever style you’re using, stick to the rules and be consistent. It might be helpful to buy an appropriate style guide. Or consult the UNC LibrariesYear Citations/footnotes and works cited/reference pages citation tutorial

- In addition, in the bottom left corner, you need to leave space for your adviser and faculty readers to sign their names. For example:

Approved by: _____________________

Adviser: Prof. Jane Doe

- This is not a required component of an honors thesis. However, if you want to thank particular librarians, archivists, interviewees, and advisers, here’s the place to do it. You should include an acknowledgments page if you received a grant from the university or an outside agency that supported your research. It’s a good idea to acknowledge folks who helped you with a major project, but do not feel the need to go overboard with copious and flowery expressions of gratitude. You can—and should—always write additional thank-you notes to people who gave you assistance.

- Formatted much like the table of contents.

- You’ll need to save this until the end, because it needs to reflect your final pagination. Once you’ve made all changes to the body of the thesis, then type up your table of contents with the titles of each section aligned on the left and the page numbers on which those sections begin flush right.

- Each page of your thesis needs a number, although not all page numbers are displayed. All pages that precede the first page of the main text (i.e., your introduction or chapter one) are numbered with small roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv, v, etc.). All pages thereafter use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.).

- Your text should be double spaced (except, in some cases, long excerpts of quoted material), in a 12 point font and a standard font style (e.g., Times New Roman). An honors thesis isn’t the place to experiment with funky fonts—they won’t enhance your work, they’ll only distract your readers.

- In general, leave a one-inch inch margin on all sides. However, for the copy of your thesis that will be bound by the library, you need to leave a 1.25-inch margin on the left.

How do I defend my honors thesis?

Graciously, enthusiastically, and confidently. The term defense is scary and misleading—it conjures up images of a military exercise or an athletic maneuver. An academic defense ideally shouldn’t be a combative scene but a congenial conversation about the work’s merits and weaknesses. That said, the defense probably won’t be like the average conversation that you have with your friends. You’ll be the center of attention. And you may get some challenging questions. Thus, it’s a good idea to spend some time preparing yourself. First of all, you’ll want to prepare 5-10 minutes of opening comments. Here’s a good time to preempt some criticisms by frankly acknowledging what you think your work’s greatest strengths and weaknesses are. Then you may be asked some typical questions:

- What is the main argument of your thesis?

- How does it fit in with the work of Ms. Famous Scholar?

- Have you read the work of Mr. Important Author?

NOTE: Don’t get too flustered if you haven’t! Most scholars have their favorite authors and books and may bring one or more of them up, even if the person or book is only tangentially related to the topic at hand. Should you get this question, answer honestly and simply jot down the title or the author’s name for future reference. No one expects you to have read everything that’s out there.

- Why did you choose this particular case study to explore your topic?

- If you were to expand this project in graduate school, how would you do so?

Should you get some biting criticism of your work, try not to get defensive. Yes, this is a defense, but you’ll probably only fan the flames if you lose your cool. Keep in mind that all academic work has flaws or weaknesses, and you can be sure that your professors have received criticisms of their own work. It’s part of the academic enterprise. Accept criticism graciously and learn from it. If you receive criticism that is unfair, stand up for yourself confidently, but in a good spirit. Above all, try to have fun! A defense is a rare opportunity to have eminent scholars in your field focus on YOU and your ideas and work. And the defense marks the end of a long and arduous journey. You have every right to be proud of your accomplishments!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Atchity, Kenneth. 1986. A Writer’s Time: A Guide to the Creative Process from Vision Through Revision . New York: W.W. Norton.

Barzun, Jacques, and Henry F. Graff. 2012. The Modern Researcher , 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. 2014. “They Say/I Say”: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing , 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Lamott, Anne. 1994. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life . New York: Pantheon.

Lasch, Christopher. 2002. Plain Style: A Guide to Written English. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Turabian, Kate. 2018. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Department of American Studies

- Home ›

- The Major ›

- Senior Thesis ›

Thesis Examples

Here are some of our best senior theses from the past few years. Hard copies of all senior theses from the last four or five years are available for reading in our department offices in Flanner Hall. Extra copies may be checked out with Katie Schlotfeldt; originals must remain in our office area.

- The Haight & the Hierarchy: Church, City, and Culture in San Francisco, 1967-2008 (2016) -- Sarah Morris

- Where Have All the Manly Journalists Gone? Gender and Masculinity in Prestige Television Representations of Journalists (2016) -- Jack Rooney

- Attica! Representations of the 1971 Prison Riot in Local and National Journalism (2016) -- Gretel Kauffman

- Literary Environmentalism in the Desert Southwest (2015) -- Caroline Schuitema

- Classrooms of Democracy: Libraries and Museums as Sites of Citizenship (2014) -- Aubrey Butts

- Identity, Activism and Queer Representation in the Age of AIDS, 1985-1995 (2013) -- Colin O'Niel

- Creating and Contesting the Cult of Girlhood: Magazines, Zines, and the Girls Who Read Them (2013) -- Olivia Lee

- A Blank Generation: Richard Hell and American Punk Rock (2012) -- Ross Finney

- Cul-de-Sac Culture Within City Limits: Exploring Urban/Suburban Borders in Chicago (2012) -- Maisie O'Malley

- Bitch. Contemporary Feminism in American Consumer Culture (2011) -- Catherine Scallen

- From Slum Clearance and Public Housing High Rises to the Olympic Village: The History of Housing in Bronzeville and the Chicago 2016 Bid (2010) -- Denise Baron

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, alert: harvard yard closed to the public.

Please note, Harvard Yard gates are currently closed. Entry will be permitted to those with a Harvard ID only.

Last Updated: May 03, 11:02am

Open Alert: Harvard Yard Closed to the Public

Preparing for a senior thesis.

Every year, a little over half of Harvard’s senior class chooses to pursue a senior thesis. While the senior thesis looks a little different from field to field, one thing remains the same: completion of a senior thesis is a serious and challenging endeavor that requires the student to make a genuine intellectual contribution to their field of interest.

The senior thesis is a significant task for students to undertake, but there is a variety of support resources available here at Harvard to ensure that seniors can make the best of their senior thesis experience.

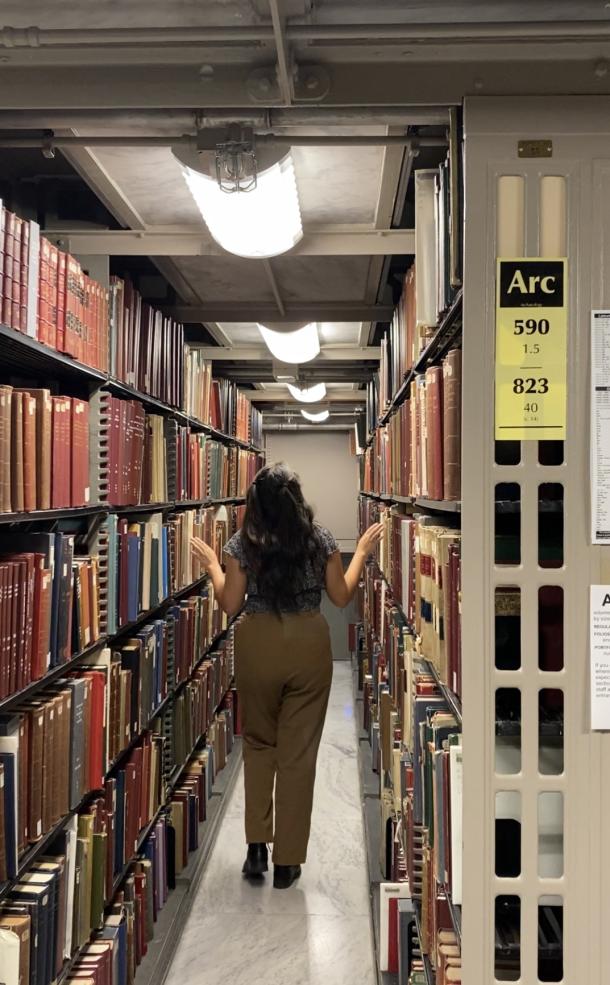

Wandering the library stacks at Widener.

I do most of my research in Widener Library. Hannah Martinez

As a rising senior in the History department, I am planning on pursuing a senior thesis on the history and use of the SAT in college admissions, and I am using the following support systems and resources to research and write my thesis:

- Staff at the History department. Every student within the department is assigned an academic advisor, who is a graduate student studying History at Harvard and knows the support available within the department. My academic advisor has helped me throughout the thesis process by connecting me with potential faculty members to advise my thesis and pick classes with a lighter course load so I can focus on completing my thesis. The Director of Undergraduate Studies in History (the History DUS) has also been pivotal in making sure that I attended a lot of information sessions about what the thesis looks like and how much of a commitment it is.

- History faculty at Harvard! All of my professors in History have been incredibly helpful in teaching me how to write like a historian, how to use primary sources in my essays, and how to undertake a serious research project over the course of a semester. Of course, while the thesis will require me to go far beyond what I’ve ever done before, I feel prepared to take on such a task because of the unwavering support from the History faculty. My mentor, Emma Rothschild, is one of the members of the faculty who has been invaluable in encouraging me to go as far as I am able.

- And last but certainly not least: funding. Funding, whether in term-time of the summer before senior year, is crucial towards making the senior thesis possible. Harvard’s Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships is dedicated to connecting Harvard students to funding sources across the university so they can pursue their research and get paid for it. This summer, I received a grant from the university of almost $2,000 so I am able to travel to libraries, buy books, and potentially take time off of work and do my research. Without such a grant, it would be incredibly difficult for me to do enough research so I can write a thesis this upcoming fall.

As you can see, there are multiple avenues for support and resources here at Harvard so your senior thesis is as easy as possible. While the senior thesis is still a challenging project that will take up a lot of time, Harvard’s resources make it possible for senior students to do their very best in all of their theses. I’m excited to start writing this fall!

Hannah Class of '23 Alumni

Hello! My name is Hannah, and I am a rising senior at Harvard concentrating in History from southeast Los Angeles County.

Student Voices

My unusual path to neuroscience, and research.

Raymond Class of '25

How the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Propelled My Love of Archives into Academic Aspirations

Beginning my senior thesis: A personal commitment to community and justice

Amy Class of '23 Alumni

Senior Thesis

A senior thesis is more than a big project write-up. It is documentation of an attempt to contribute to the general understanding of some problem of computer science, together with exposition that sets the work in the context of what has come before and what might follow. In computer science, some theses involve building systems, some involve experiments and measurements, some are theoretical, some involve human subjects, and some do more than one of these things. Computer science is unusual among scientific disciplines in that current faculty research has many loose ends appropriate for undergraduate research.

Senior thesis projects generally emerge from collaboration with faculty. Students looking for senior thesis projects should tell professors they know, especially professors whose courses they are taking or have taken, that they are looking for things to work on. See the page on CS Research for Undergrads . Ideas often emerge from recent papers discussed in advanced courses. The terms in which some published research was undertaken might be generalized, relaxed, restricted, or applied in a different domain to see if changed assumptions result in a changed solution. Once a project gets going, it often seems to assume a life of its own.

To write a thesis, students may enroll in Computer Science 91r one or both terms during their senior year, under the supervision of their research advisor. Rising seniors may wish to begin thinking about theses over the previous summer, and therefore may want to begin their conversations with faculty during their junior spring—or even try to stay in Cambridge to do summer research.

An information session for those interested in writing a senior thesis is held towards the end of each spring semester. Details about the session will be posted to the [email protected] email list.

Students interested in commercializing ideas in their theses may wish to consult Executive Dean Fawwaz Habbal about patent protection. See Harvard’s policy for information about ownership of software written as part of your academic work.

Thesis Supervisor

You need a thesis supervisor. Normally this is a Harvard Computer Science faculty member. Joint concentrators (and, in some cases, non-joint concentrators) might have a FAS/SEAS Faculty member from a different field as their thesis supervisor. Exceptions to the requirement that the thesis supervisor is a CS or FAS/SEAS faculty member must be approved by the Director of Undergraduate Studies. For students whose advisor is not a Harvard CS faculty member, note that at least one of your thesis readers must be a Harvard CS faculty member, and we encourage you to talk with this faculty member regularly to help ensure that your thesis is appropriately relevant for Harvard Computer Science.

It’s up to you and your supervisor how frequently you meet and how engaged the supervisor is in your thesis research. However, we encourage you to meet with your supervisor at least several times during the Fall and Spring, and to agree on deadlines for initial results, chapter outlines, drafts, etc.

Thesis Readers

The thesis is evaluated by the thesis readers. Thesis readers must be either:

Two Harvard CS faculty members/affiliates ; or:

Three readers, at least one of whom is a Harvard CS faculty member and the others are ordinarily teaching faculty members of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences or SEAS who are generally familiar with the research area.

The thesis supervisor is one of the readers.

The student is responsible for finding the other readers, but you can talk with your supervisor for suggestions of possible readers.

Exceptions to these thesis reader requirements must be approved by the Directors of Undergraduate Studies.

For joint concentrators, the other concentration may have different procedures for thesis readers; if you have any questions or concerns about thesis readers, please contact the Directors of Undergraduate Studies.

Senior Thesis Seminar

Computer Science does not have a Senior Thesis seminar course.

However, we do run an informal optional series of Senior Thesis meetings in the Fall to help with the thesis writing process, focused on topics such as technical writing tips, work-shopping your senior thesis story, structure of your thesis, and more. Pay attention to your email in the Fall for announcements about this series of meetings.

The thesis should contain an informative abstract separate from the body of the thesis. This abstract should clearly state what the contribution of the thesis is–which parts are expository, whether there are novel results, etc. We also recommend the thesis contain an introduction that is at most 5 pages in length that contains an “Our contributions” section which explains exactly what the thesis contributed, and which sections in the thesis these are elaborated on. At the degree meeting, the Committee on Undergraduate Studies in Computer Science will review the thesis abstract, the reports from the three readers and the student’s academic record; it will have access to the thesis. The readers (and student) are told to assume that the Committee consists of technical professionals who are not necessarily conversant with the subject matter of the thesis so their reports (and abstract) should reflect this audience.

The length of the thesis should be as long as it needs to be to present its arguments, but no longer!

There are no specific formatting guidelines. For LaTeX, some students have used this template in the past . It is set up to meet the Harvard PhD Dissertation requirements, so it is meeting requirements that you as CS Senior Thesis writers don’t have.

Thesis Timeline for Seniors

(The timeline below is for students graduating in May. For off-cycle students, the same timeline applies, but offset by one semester. The thesis due date for March 2025 graduates is Friday November 22, 2024 at 2pm. The thesis deadline for May 2024 graduates is Friday March 29th Monday April 1st at 2pm.

Please be aware that students writing a joint thesis must meet the requirements of both departments–so if there are two different due dates for the thesis, you are expected to meet the earlier date.

Senior Fall (or earlier) Find a thesis supervisor, and start research.

October/November/December Start writing.

All fourth year concentrators are contacted by the Office of Academic Programs and those planning to submit a senior thesis are requested to supply certain information, including name of advisor and a tentative thesis title. You may use a different title when you submit your thesis; you do not need to tell us your updated title before then. If Fall 2024 is your final term, please fill out this form . If May 2024 is your final term, please fill out this form .

Early February The student should provide the name and contact information for the readers (see above), together with assurance that they have agreed to serve.

Mid-March Thesis supervisors are advised to demand a first draft. (A common reaction of thesis readers is “This would have been an excellent first draft. Too bad it is the final thesis—it could have been so much better if I had been able to make some suggestions a couple of weeks ago.")

April 1, 2024 * Thesis is due by 2:00 pm. Electronic copies in PDF format should be delivered by the student to all three readers and to [email protected] (which will forward to the Director of Undergraduate Studies) on or before that date. An electronic copy should also be submitted via the SEAS online submission tool on or before that date. SEAS will keep this electronic copy as a non-circulating backup. During this online submission process, the student will also have the option to make the electronic copy publicly available via DASH, Harvard’s open-access repository for scholarly work. Please note that the thesis will NOT be published to ProQuest. More information can be found on the SEAS Senior Thesis Submission page.

The two or three readers will receive a rating sheet to be returned to the Office of Academic Programs before the beginning of the Reading Period, together with their copy of the thesis and any remarks to be transmitted to the student.

Late May The Office of Academic Programs will send students their comments after the degree meeting to decide honors recommendations.

Thesis Extensions and Late Submissions

Thesis extensions Thesis extensions will be granted in extraordinary circumstances, such as hospitalization or grave family emergency, with the support of the thesis advisor and resident dean and the agreement of all readers. For joint concentrators, the other concentration should also support the extension. To request an extension, please have your advisor or resident dean email [email protected] , ideally several business days in advance, so that we may follow up with readers. Please note that any extension must be able to fall within our normal grading, feedback, and degree recommendation deadline, so extensions of more than a few days are usually impossible.

Late submissions Late submission of thesis work should be avoided. Work that is late will ordinarily not be eligible for thesis prizes like the Hoopes Prize. Theses submitted late will ordinarily be penalized one full level of honors (highest honors, high honors, honors, no honors) per day late or part thereof, including weekends, so a thesis submitted two days and one minute late is ordinarily ineligible to receive honors. Penalties will be waived only in extraordinary cases, such as documented medical illness or grave family emergency; students should consult with the Directors of Undergraduate Studies in that event. Missed alarm clocks, crashed computers, slow printers, corrupted files, and paper jams are not considered valid causes for extensions.

Thesis Examples

Recent thesis examples can be found on the Harvard DASH (Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard) repository here . Examples of Mind, Brain, Behavior theses are here .

Spectral Sparsification: The Barrier Method and its Applications

- Martin Camacho, Advisor: Jelani Nelson

Good Advice Costs Nothing and it’s Worth the Price: Incentive Compatible Recommendation Mechanisms for Exploring Unknown Options

- Perry Green, Advisor: Yiling Chen

Better than PageRank: Hitting Time as a Reputation Mechanism

- Brandon Liu, Advisor: David Parkes

Tree adjoining grammar at the interfaces

- Nicholas Longenbaugh, Advisor: Stuart Shieber

SCHUBOT: Machine Learning Tools for the Automated Analysis of Schubert’s Lieder

- Dylan Nagler, Advisor: Ryan Adams

Learning over Molecules: Representations and Kernels

- Jimmy Sun, Advisor: Ryan Adams

Towards the Quantum Machine: Using Scalable Machine Learning Methods to Predict Photovoltaic Efficacy of Organic Molecules

- Michael Tingley, Advisor: Ryan Adams

- Research Centers

- Academic Programs

- Princeton University

- News & Activities

- Prospective Majors

- Major Requirements

- Course Selection

- Independent Work

- Other Rules and Grading Guidelines

- Economics Statistical Services (ESS)

- Minors and Programs

- Study Abroad and Internship Milestone Credit

- Funding, Research Assistant, and Career Opps

- Common Questions

- Ph.D. Admissions

- Current Students

- Course Offerings

- Job Market and Placements

- Graduate Student Directory

Senior Thesis

- Resources and Form Library

- Funding, Research Assistant, and Career Opportunities

Through their Senior Thesis, majors learn to identify interesting economics questions, survey the existing academic literature and demonstrate command of theoretical, empirical, and/or experimental methods needed to critically analyze their chosen topic.

All seniors are encouraged to browse the Senior Thesis Database for examples of past work.

To see examples of papers that won Senior Thesis Prizes, see this article about the Class of ’22 student winners.

Senior Thesis Coordinator Professor Alessandro Lizzeri [email protected]

Key Resources for Seniors

Senior Thesis Handbook Senior Thesis At-a-Glance Senior Thesis Advisors and Their Advising Interests Senior Thesis Proposal/Advisor Request Form Senior Thesis Advisor Assignments Senior Thesis Grading Rubric Exit form: Senior Thesis Research Integrity Form Exit form: Senior Thesis Advisor Evaluation Exit form: Departmental Survey

Senior Prizes

At the end of senior year, the department awards several prizes to acknowledge the best Senior Thesis projects from each class. Available awards are listed below.

- John Glover Wilson Memorial Award: Awarded to the best thesis on international economics or politics.

- Walter C. Sauer ’28 Prize (joint eligibility with Politics, SPIA): Awarded to the student whose thesis or research project on any aspect of United States foreign trade is judged to be the most creative.

- The Griswold Center for Economic Policy Studies Prize: Awarded annually to the best five policy-relevant theses.

- Burton G. Malkiel ’64 Senior Thesis Prize in Finance: Awarded for the most outstanding thesis in the field of finance.

- Elizabeth Bogan Prize in Economics: Awarded for the best thesis in health, education, or welfare.

- Daniel L. Rubinfeld ’67 Prize in Empirical Economics: Awarded for the best thesis in empirical economics.

- Hugo Sonnenschein Prize in Economic Theory: Awarded for the best thesis on economic theory.

- Wolf Balleisen Memorial Prize: Awarded for the best thesis on an economics subject, written by an economics major.

- Halbert White ’72 Prize in Economics: Awarded to the most outstanding senior economics major, as evidenced by excellence in departmental coursework and creativity in the Junior Paper and Senior Thesis.

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

Psychology junior paper and senior thesis guide.

- Research Consultations

- Junior Paper Guidelines

- Senior Thesis Guidelines

Repository of Senior Theses at Princeton

- Psychology Literature

- Keyword Searching

- Literature Mapping This link opens in a new window

- Evaluating Articles

- Finding the Full Text

- Reference Managers

- Peer Review

Examples of Senior Theses can be found in Princeton's Institutional Repository.

Browse by Academic Advisor to see theses that your advisor has previously mentored.

- << Previous: Senior Thesis Guidelines

- Next: Psychology Literature >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 11:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/psyc_jp_thesis

What Is a Senior Thesis?

Daniel Ingold/Cultura/Getty Images

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A senior thesis is a large, independent research project that students take on during their senior year of high school or college to fulfill their graduation requirement. It is the culminating work of their studies at a particular institution, and it represents their ability to conduct research and write effectively. For some students, a senior thesis is a requirement for graduating with honors.

Students typically work closely with an advisor and choose a question or topic to explore before carrying out an extensive research plan.

Style Manuals and the Paper's Organization

The structure of your research paper will depend, in part, on the style manual that is required by your instructor. Different disciplines, such as history, science, or education, have different rules to abide by when it comes to research paper construction, organization, and modes of citation. The styles for different types of assignment include:

Modern Language Association (MLA): The disciplines that tend to prefer the MLA style guide include literature, arts, and the humanities, such as linguistics, religion, and philosophy. To follow this style, you will use parenthetical citations to indicate your sources and a works cited page to show the list of books and articles you consulted.

American Psychological Association (APA): The APA style manual tends to be used in psychology, education, and some of the social sciences. This type of report may require the following:

- Introduction

Chicago style: "The Chicago Manual of Style" is used in most college-level history courses as well as professional publications that contain scholarly articles. Chicago style may call for endnotes or footnotes corresponding to a bibliography page at the back or the author-date style of in-text citation, which uses parenthetical citations and a references page at the end.

Turabian style: Turabian is a student version of Chicago style. It requires some of the same formatting techniques as Chicago, but it includes special rules for writing college-level papers, such as book reports. A Turabian research paper may call for endnotes or footnotes and a bibliography.

Science style: Science instructors may require students to use a format that is similar to the structure used in publishing papers in scientific journals. The elements you would include in this sort of paper include:

- List of materials and methods used

- Results of your methods and experiments

- Acknowledgments

American Medical Association (AMA): The AMA style book might be required for students in medical or premedical degree programs in college. Parts of an AMA research paper might include:

- Proper headings and lists

- Tables and figures

- In-text citations

- Reference list

Choose Your Topic Carefully

Starting off with a bad, difficult, or narrow topic likely won't lead to a positive result. Don't choose a question or statement that's so broad that it's overwhelming and could comprise a lifetime of research or a topic that's so narrow you'll struggle to compose 10 pages. Consider a topic that has a lot of recent research so you won't struggle to put your hands on current or adequate sources.

Select a topic that interests you. Putting in long hours on a subject that bores you will be arduous—and ripe for procrastination. If a professor recommends an area of interest, make sure it excites you.

Also, consider expanding a paper you've already written; you'll hit the ground running because you've already done some research and know the topic. Last, consult with your advisor before finalizing your topic. You don't want to put in a lot of hours on a subject that is rejected by your instructor.

Organize Your Time

Plan to spend half of your time researching and the other half writing. Often, students spend too much time researching and then find themselves in a crunch, madly writing in the final hours. Give yourself goals to reach along certain "signposts," such as the number of hours you want to have invested each week or by a certain date or how much you want to have completed in those same timeframes.

Organize Your Research

Compose your works cited or bibliography entries as you work on your paper. This is especially important if your style manual requires you to use access dates for any online sources that you review or requires page numbers be included in the citations. You don't want to end up at the very end of the project and not know what day you looked at a particular website or have to search through a hard-copy book looking for a quote that you included in the paper. Save PDFs of online sites, too, as you wouldn't want to need to look back at something and not be able to get online or find that the article has been removed since you read it.

Choose an Advisor You Trust

This may be your first opportunity to work with direct supervision. Choose an advisor who's familiar with the field, and ideally select someone you like and whose classes you've already taken. That way you'll have a rapport from the start.

Consult Your Instructor

Remember that your instructor is the final authority on the details and requirements of your paper. Read through all instructions, and have a conversation with your instructor at the start of the project to determine his or her preferences and requirements. Have a cheat sheet or checklist of this information; don't expect yourself to remember all year every question you asked or instruction you were given.

- What Is a Bibliography?

- Turabian Style Guide With Examples

- What Is a Citation?

- Formatting Papers in Chicago Style

- What Is a Style Guide and Which One Do You Need?

- Definition of Appendix in a Book or Written Work

- Bibliography: Definition and Examples

- What Are Endnotes, Why Are They Needed, and How Are They Used?

- Tips for Typing an Academic Paper on a Computer

- How to Organize Research Notes

- Bibliography, Reference List or Works Cited?

- What's the Preferred Way to Write the Abbreviation for United States?

- How to Write a Research Paper That Earns an A

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- MLA Style Parenthetical Citations

- Formatting APA Headings and Subheadings

There are active notices and/or alerts. Visit the Alerts site for details >>

This program rewards students for conducting an original, independent project at a level well above those found in a traditional course.

- Senior Thesis Program

- Academic Offices & Resources

Successful completion of the Senior Thesis Project will:

- Enhance your application to graduate school or post-graduation employment

- Earn public recognition at graduation

- Include your project in the Library’s permanent collection

View, download, and print the Senior Thesis Program Factsheet (pdf).

Get Involved

Eligibility, course work.

To be eligible to register for the Longwood Senior Thesis Program , a student must have:

- a strong interest in doing independent research

- a 3.0 overall grade point average on work taken at Longwood

- a 3.0 average in courses taken at Longwood for the major

- agreement of a faculty member to serve as a sponsor

- permission of the Longwood Senior Thesis (LST) Committee

In consultation with the faculty sponsor, develop a research topic and prepare a research proposal.

Proposals should not exceed 7-8 double-spaced pages (not including figures, tables, and bibliography). The proposal is then presented before the Longwood Senior Thesis Committee.

Submit your Longwood Senior Thesis Proposal on Digital Commons @ Longwood .

- Proposal Example 1 Biology

- Proposal Example 2 Biology

- Proposal Example 3 Business

- Proposal Example 4 Business

- Proposal Example 5 Chemistry

- Proposal Example 6 Chemistry

- Proposal Example 7 English

- Proposal Example 8 Hark

- Proposal Example 9 Hark

- Proposal Example 10 History

The Senior Thesis Program is undertaken by motivated students who wish to pursue their scholarship interests outside of the classroom.

Completion of the project requires that students enroll in two consecutive 3-credit courses, typically with the second of those courses within their senior year.

The thesis acts as the major product of your 499 course and needs to be written with a structure that is appropriate to your field of study or major.

The guidelines of which need to be discussed with your thesis advisor.

In general, the theses tend to be between 20 to 40 pages in length with a detailed introduction to the literature on the project topic.

Then a description of the project, work performed, and its outcomes.

Past approved undergraduate theses can be found on Longwood Digital Commons .

- LST Example Thesis 1 (pdf)

- LST Example Thesis 2 (pdf)

- LST Example Thesis 3 (pdf)

- Prepare proposed project in collaboration with a faculty sponsor

- Present proposal to LST committee members

- Enroll in 498 course and complete or nearly complete proposed project

- Report progress to examination committee members

- Enroll in 499 course and complete project work (if needed)

- Write thesis

- Present work at the Longwood Student Showcase

- Defend thesis project with the examination committee

Upcoming Events

- Undergraduate Programs

- Continuing Education

- Graduate Programs

- Cook-Cole College of Arts & Sciences

- College of Business & Economics

- College of Education, Health, and Human Services

- College of Graduate and Professional Studies

- Cormier Honors College for Citizen Scholars

- Academic Affairs

- Academic Success

- Accreditation & Compliance

- Assessment & Institutional Research

- Career Success

- Digital Education Collaborative

- Global Engagement

- Baliles Center

- Student Responsibilities

- Thesis Project Resources

- Research, Grants & Sponsored Projects

- Student Research

- Veteran and Military Students

- The Civitae Core Curriculum

Dr. Maxwell Hennings

201 High Street

Farmville, VA 23909

(434) 395-2387

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Senior Thesis Examples. Graduating seniors in Biological Sciences have the option of submitting a senior thesis for consideration for Honors and Research Prizes . Below are some examples of particularly outstanding theses from recent years (pdf): Sledd Thesis. Yu Thesis.

Find out how to write a thesis or dissertation by looking at previous work done by other students on similar topics. Browse a list of award-winning theses and dissertations from various disciplines and universities.

Learn how to write a Senior Thesis in HEB, a discipline that studies adaptation and natural selection. Find out the eligibility, requirements, schedule, format, and evaluation of the thesis process.

This document provides a comprehensive guide to writing a senior thesis in sociology, from choosing a topic and an adviser to drafting and revising the final product. It includes tips on time management, research methods, data analysis, writing style, and formatting.

Find resources and tips for writing a senior thesis in various disciplines at Harvard University. Download PDF guides, access writing tutorials, and explore additional resources for thesis writers.

done, for example, in their junior tutorial essays. This is, of course, just fine; and you can even use some of the material from said essays in your thesis if you must (it's not necessary to reinvent the wheel). However, your senior thesis should be a completely new project. If you wrote on William

A senior thesis in psychology, for example, is often a year-long research project—perhaps in conjunction with one of your faculty advisor's labs—where you might design and conduct your own study utilizing human subjects. Or maybe monkeys. A senior thesis in literature, on the other hand, will likely involve studying a movement, trope ...

senior thesis is not simply a much longer term paper. It is not simply an independent project carried out under the general guidance of an advisor. It does not simply require more research, more evidence, and more writing. Rather, your thesis requires more methodology. In a nutshell, that is what this handbook is meant to provide.

of their thesis project as having provided a valuable opportunity that, depending on their choice of profession, they may never have the chance to repeat. Students remember, for example, the expertise they developed on their topics; the seeming luxury of devoting

The Writing Center has Senior Thesis Tutors who will read drafts of your thesis (more typically, parts of your thesis) in advance and meet with you individually to talk about structure, argument, clear writing, and mapping out your writing plan. If you need help with breaking down your project or setting up a schedule for the week, the semester ...

What this handout is about. Writing a senior honors thesis, or any major research essay, can seem daunting at first. A thesis requires a reflective, multi-stage writing process. This handout will walk you through those stages. It is targeted at students in the humanities and social sciences, since their theses tend to involve more writing than ...

Senior Thesis › Thesis Examples; Thesis Examples. Here are some of our best senior theses from the past few years. Hard copies of all senior theses from the last four or five years are available for reading in our department offices in Flanner Hall. Extra copies may be checked out with Katie Schlotfeldt; originals must remain in our office area.

Every year, a little over half of Harvard's senior class chooses to pursue a senior thesis. While the senior thesis looks a little different from field to field, one thing remains the same: completion of a senior thesis is a serious and challenging endeavor that requires the student to make a genuine intellectual contribution to their field of interest.

The EPS Senior Thesis Guide Updated March 17, 2021 1 The EPS Senior Thesis Guide . A Note to Students: Completing a senior thesis will likely be the most challenging and rewarding experience of your ... This may involve sample collection, laboratory analysis, data collection, coding, creating models, conducting statistical tests, etc.

A senior thesis is more than a big project write-up. It is documentation of an attempt to contribute to the general understanding of some problem of computer science, together with exposition that sets the work in the context of what has come before and what might follow. ... Thesis Examples . Recent thesis examples can be found on the Harvard ...

Senior Thesis research. This Senior Thesis Prospectus is due on Tuesday, September 20, 2022. It serves the purpose of ensuring that you have a clear vision of the work that lies ahead for you and your faculty advisor. You have had all summer to think about your Senior Thesis research. You should return to campus organized and prepared to begin

Through their Senior Thesis, majors learn to identify interesting economics questions, survey the existing academic literature and demonstrate command of theoretical, empirical, and/or experimental methods needed to critically analyze their chosen topic. All seniors are encouraged to browse the Senior Thesis Database for examples of past work.

This page is for Undergraduate Senior Theses. For Ph.D. Theses, see here.. So that Math Department senior theses can more easily benefit other undergraduate, we would like to exhibit more senior theses online (while all theses are available through Harvard University Archives, it would be more convenient to have them online).It is absolutely voluntary, but if you decide to give us your ...

Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates. Published on June 7, 2022 by Tegan George.Revised on November 21, 2023. A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical early steps in your writing process.It helps you to lay out and organize your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding the specifics of your dissertation topic and showcasing its relevance to ...

Princeton University Library One Washington Road Princeton, NJ 08544-2098 USA (609) 258-1470

Updated on January 24, 2019. A senior thesis is a large, independent research project that students take on during their senior year of high school or college to fulfill their graduation requirement. It is the culminating work of their studies at a particular institution, and it represents their ability to conduct research and write effectively.

Academic Offices & Resources. Senior Thesis Program. Distinguish yourself from your peers and improve your abilities to research and write academic scholarship. Successful completion of the Senior Thesis Project will: Enhance your application to graduate school or post-graduation employment. Earn public recognition at graduation.

What is a Senior Thesis? In most classical Christian schools, 12th graders are expected to write, present, and sometimes defend, a senior thesis. The senior thesis is a wonderful opportunity for students to take the skills they have learned throughout their educational experience (skills like thinking logically and being able to communicate ...