Stream of Consciousness

Stream of consciousness definition.

The literary device stream of consciousness is the continuous flow of thoughts of a person and recorded, thereof, in literature as they occur. In other words, it means to capture a continuous stream of thoughts into words and then scribble them on paper for others to read. This device is used as a noun . The term was first used by a psychologist, William James, in his work published in 1890.

“… it is nothing joined; it flows. A ‘river’ or a ‘stream’ is the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let’s call it the stream of thought, consciousness, or subjective life.” – William James from The Principles of Psychology .

Another appropriate term for this device is “interior monologue ,” where the individual thought processes of a character , associated with his or her actions, are portrayed in the form of a monologue that addresses the character itself. Therefore, it is different from the “ dramatic monologue ” or “ soliloquy ,” where the speaker addresses the audience or the third person.

Difference Between Stream of Consciousness and Free Writing

Stream of consciousness and free writing seems the same. However, the stream of consciousness is a literary activity in which the character is planned, sketched, and then thoughts are scribbled afterward. In freewriting, it is specific, planned, and topic-centered. It is non- fiction as well as a fictional activity. On the other hand, the stream of consciousness in literature writing is character-specific and objective-oriented. Yet, in one way, both are similar in that both need a free mind to write on some topic which in the case of fiction could be a character while in the case of free writing could be a non-fictional essay .

Difference between Traditional Prose and Stream of Consciousness:

- Syntax : Syntax in traditional prose is correct, has an appropriate structure, and is to the point, while it could be choppy, poor, and even wrong in the case of a stream of consciousness.

- Grammar: There is no sense of grammar in the stream of consciousness writing when it is jumbled up or the mind is in a state of flux. However, it is correct, pure, and exact in traditional prose.

- Association: Traditional prose has some association with the general world while the stream of consciousness is removed from reality and is associated with the mind of the character.

- Repetition : Traditional prose is not repetitious unless it is rhetoric , while the writing in a stream of consciousness could be repetitious to the point of annoyance.

- Plot Structure: The plot is structureless in the case of a stream of consciousness, while in the case of traditional prose, it is well organized.

How to Write Stream of Consciousness?

A writer must keep the following points in mind when writing in a stream of consciousness style .

- It must be character-specific.

- It must sync with the character’s world; profession, relations, work, near and dear ones, and even daily activities .

- It must seem to follow the thoughts of that person.

- It must have some links and pieces of evidence of the thought process.

- It must not have a structure, grammar, or any other formal linguistic evidence unless it is recorded for an educational academic.

Examples of Stream of Consciousness in Literature

The stream of consciousness style of writing is marked by the sudden rise of thoughts and lack of punctuation . The use of this narration style is generally associated with the modern novelist and short story writers of the 20th century. Let us analyze a few examples of the stream of consciousness narrative technique in literature:

Example #1 Ulysses by James Joyce

James Joyce successfully employs the narrative mode in his novel Ulysses , which describes a day in the life of a middle-aged Jew, Mr. Leopold Broom, living in Dublin, Ireland. Read the following excerpt:

“He is young Leopold, as in a retrospective arrangement, a mirror within a mirror (hey, presto!), he beholdeth himself. That young figure of then is seen, precious manly, walking on a nipping morning from the old house in Clambrassil to the high school, his book satchel on him bandolier wise, and in it a goodly hunk of wheaten loaf, a mother’s thought.”

These lines reveal the thoughts of Bloom, as he thinks of the younger Bloom. The self-reflection is achieved by the flow of thoughts that takes him back to his past.

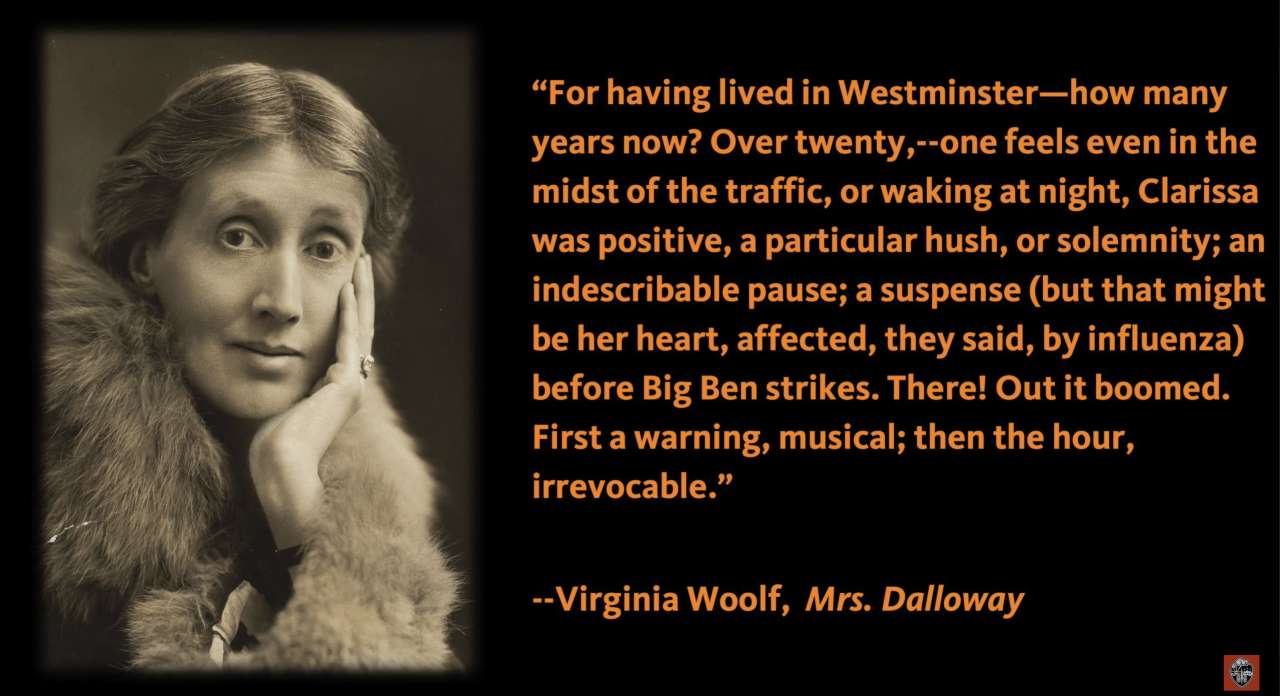

Example #2 Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

“What a lark! What a plunge! For so it always seemed to me when, with a little squeak of the hinges, which I can hear now , I burst open the French windows and plunged at Bourton into the open air. How fresh, how calm, stiller than this of course, the air was in the early morning; like the flap of a wave; the kiss of a wave; chill and sharp and yet (for a girl of eighteen as I then was) solemn, feeling as I did, standing there at the open window, that something awful was about to happen …”

Another 20th-century writer that followed James Joyce ’s narrative method was Virginia Woolf. By voicing her internal feelings, Ms. Woolf gives freedom to the characters to travel back and forth in time. Mrs. Dalloway went out to buy flowers for herself, and on the way her thoughts move through the past and present, giving us an insight into the complex nature of her character.

Example #3 The British Museum Is Falling Down by David Lodge

“It partook, he thought, shifting his weight in the saddle, of metempsychosis, the way his humble life fell into moulds prepared by literature. Or was it, he wondered, picking his nose, the result of closely studying the sentence structure of the English novelists? One had resigned oneself to having no private language any more, but one had clung wistfully to the illusion of a personal property of events. A find and fruitless illusion, it seemed, for here, inevitably came the limousine, with its Very Important Personage, or Personages, dimly visible in the interior. The policeman saluted, and the crowd pressed forward, murmuring ‘Philip’, ‘Tony’, ‘Margaret’, ‘Prince Andrew’.”

We notice the use of this technique in David Lodge’s novel The British Museum Is Falling Down. It is a comic novel that imitates the stream of consciousness narrative techniques of writers like Henry James, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf. We see the imitation of the typical structure of the stream-of-conscious narrative technique of Virginia Woolf. We notice the integration of the outer and inner realities in the passage that is so typical of Virginia Woolf, especially the induction of the reporting clauses “he thought,” and “he wondered,” in the middle of the reported clauses.

Example #4 Notes from The Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky

I have been going on like that for a long time—twenty years. Now I am forty. I used to be in the government service, but am no longer. I was a spiteful official. I was rude and took pleasure in being so. I did not take bribes, you see, so I was bound to find a recompense in that, at least. (A poor jest , but I will not scratch it out. I wrote it thinking it would sound very witty; but now that I have seen myself that I only wanted to show off in a despicable way, I will not scratch it out on purpose!)

This passage can be found at the beginning of the novel. The protagonist of the novel narrates how he has passed more than four decades of his life as it is and has been expelled from the government service. The first-person narration shows his thoughts converted into words. However, the novel was written in Russian and translated into English. Hence, grammar, syntax , and style do not seem to follow the same pattern. However, the monologue occurs in the consciousness of a person.

Example #5 As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

“Well, it isn’t like they cost me anything,” I say. I saved them out and swapped a dozen of them for the sugar and flour. It isn’t like the cakes cost me anything, as Mr Tull himself realises that the eggs I saved were over and beyond what we had engaged to sell, so it was like we had found the eggs or they had been given to us. “She ought to taken those cakes when she same as gave you her word,” Kate says. The Lord can see into the heart. If it is His will that some folks has different ideas of honesty from other folks, it is not my place to question His decree.”

These passages are borrowed from As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner . Cora narrates how she has saved something sugar and floor and that Mr. Tull has made her realize that the eggs are now finished. In the next passage, Kate also adds to things that are coming into their stream of consciousness. This stream of consciousness shows, somewhat, sophisticated thoughts with good wording, good grammar, and good sentence structure.

Example #6 On the Road by Jack Kerouac

During the following week, he confided in Chad King that he absolutely had to learn how to write from him; Chad said I was a writer and he should come to me for advice. Meanwhile Dean had gotten a job in a parking lot, had a fight with Marylou in their Hoboken apartment – God knows why they went there – and she was so mad and so down deep vindictive that she reported to the police some false trumped-up hysterical crazy charge, and Dean had to lam from Hoboken. So he had no place to live. He came right out to Paterson, New Jersey, where I was living with my aunt, and one night while I was studying there was a knock on the door, and there was Dean, bowing, shuffling obsequiously in the dark of the hall, and saying, «Hello, you remember me – Dean Moriarty? I’ve come to ask you to show me how to write.

This passage, though, has good punctuation, and good wording gives the impression that Sal Paradise shows his understanding of different things and how his mind moves from Chad to Dean and vice versa with different places and persons coming in quick succession. This shows a beautiful example of the stream of consciousness.

Function of Stream of Consciousness

Stream of consciousness is a style of writing developed by a group of writers at the beginning of the 20th century. It aimed at expressing in words the flow of characters’ thoughts and feelings in their minds. The technique aspires to give readers the impression of being inside the minds of the characters. Therefore, the internal view of the minds of the characters sheds light on the plot and motivation in the novel.

Synonyms of Stream of Consciousness

Stream of Consciousness has no other word or phrase as an exact meaning. However, the following words can be used interchangeably in general meanings such as apostrophe , association of ideas, chain of thought, interior monologue, monologue, aside , or a soliloquy.

Post navigation

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Faculty Notes Submission Form

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

What is Stream of Consciousness? | Definition & Examples

"what is stream of consciousness": a guide for english students and teachers.

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- OSU Admissions Info

- Guide to Literary Terms

What is Stream of Consciousness? - Transcript (English and Spanish Subtitles Available in Video, Click HERE for Spanish Transcript)

By Liz Delf , Oregon State University Senior Instructor of Literature

12 Nov. 2019

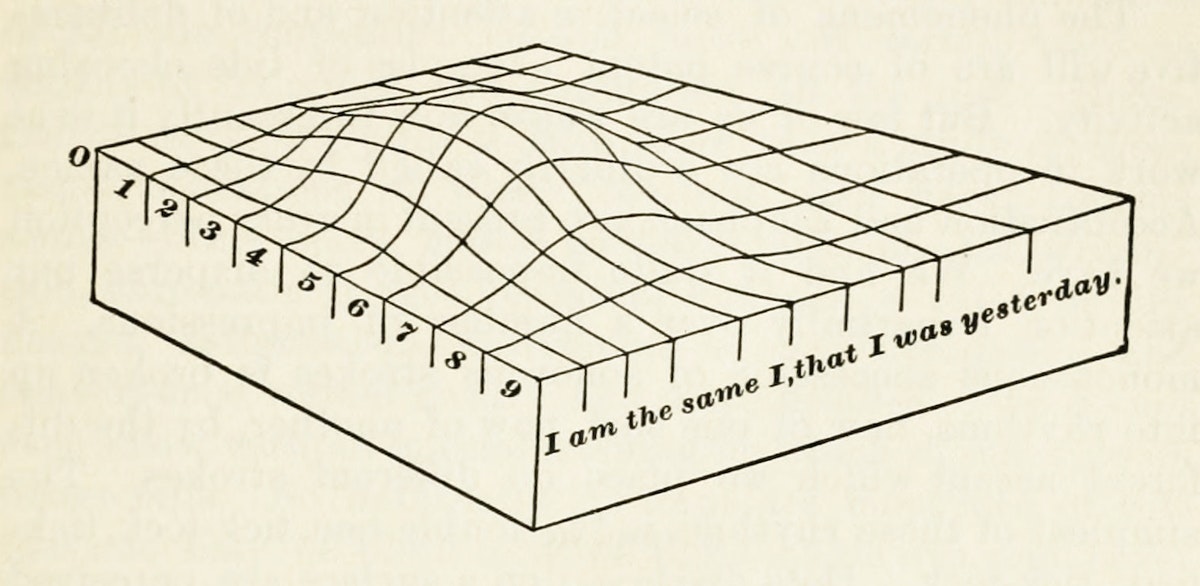

Stream of consciousness is a narrative style that tries to capture a character’s thought process in a realistic way. It’s an interior monologue, but it’s also more than that. Because it’s mimicking the non-linear way our brains work, stream-of-consciousness narration includes a lot of free association, looping repetitions, sensory observations , and strange (or even nonexistent) punctuation and syntax —all of which helps us to better understand a character’s psychological state and worldview. It’s meant to feel like you have dipped into the stream of the character’s consciousness—or like you’re a fly on the wall of their mind.

Authors who use this technique are aiming for emotional and psychological truth: they want to show a snapshot of how the brain actually moves from one place to the next. Thought isn’t linear, these authors point out; we don’t really think in logical, well-organized, or even complete sentences.

For example, on my way to record this video, I didn’t think “Ah, now I am walking to the library. When I get there, I will say good morning to the videographer, and then begin recording. I hope it goes well.”

A more accurate representation might be more like this: “cold / bright / wish I had my sunglasses / walk faster / late again / always late / did I send my script? / should I have practiced more? / oh hi Dylan / which class was he in? / shoe’s untied / ooh colors trees red orange bright / faster / late late late / so bright”

stream_of_consciousness_shoe.jpg

That more realistic, stream-like, associative thought process is what authors are aiming for when they use stream of consciousness narration.

Here’s a literary example from Mrs. Dalloway , by Virginia Woolf:

stream_of_consciousness_woolf.jpg

“For having lived in Westminster—how many years now? Over twenty,--one feels even in the midst of the traffic, or waking at night, Clarissa was positive, a particular hush, or solemnity; an indescribable pause; a suspense (but that might be her heart, affected, they said, by influenza) before Big Ben strikes. There! Out it boomed. First a warning, musical; then the hour, irrevocable.”

This passage is about Clarissa Dalloway’s connection to the city, linking her own heartbeat to the clock’s chimes. But it’s also a good example of stream of consciousness: it has associative thoughts (moving from the clock chimes to her influenza), unusual syntax (all those semi-colons !), and sensory details (like sound, music, and the feeling of a heartbeat).

Virginia Woolf is particularly well known for this narrative technique, along with some other modernist heavy hitters like James Joyce, William Faulkner, and Marcel Proust. Those particular authors were writing in the 1920s and 30s, but stream-of-consciousness isn’t limited to a particular time period or literary movement. It’s unusual, but it has been used by authors like Ken Kesey and Sylvia Plath in the 1960s, as well as Irvine Welsh, George Saunders, and Jonathan Safran Foer in the last decade or so.

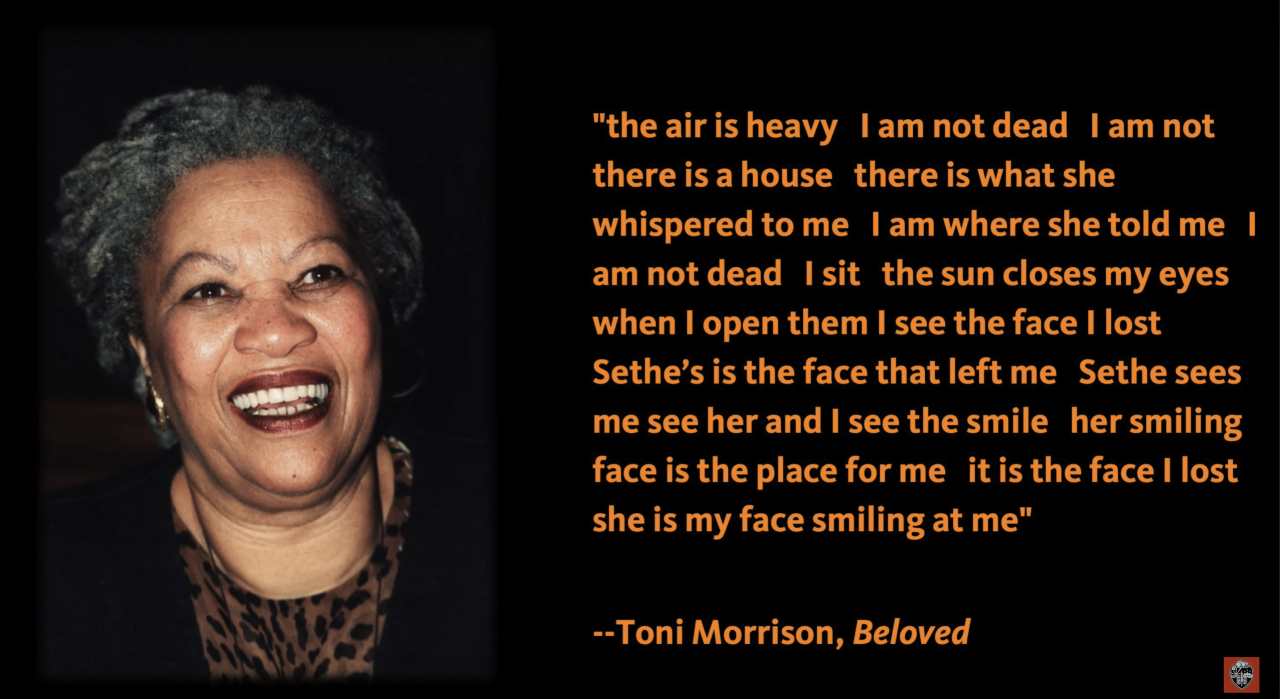

Here’s one more example, this one from Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved :

“the air is heavy / I am not dead / I am not / there is a house / there is what she whispered to me / I am where she told me / I am not dead / I sit / the sun closes my eyes / when I open them I see the face I lost / Sethe’s is the face that left me / Sethe sees me see her and I see the smile / her smiling face is the place for me / it is the face I lost / she is my face smiling at me”

stream_of_consciousness_morrison.jpg

This example is even more disjointed than the first, and that’s a key element of understanding this particular character. The speaker (Beloved) is childlike, ghostly, scared, and confused. Her agitated repetition of “I am not dead” makes it feel like she’s desperately holding onto life, and the many echoes of Sethe’s smiling face show the emotional resonance and importance that image carries for Beloved.

Association is also prominent in this example, moving from the house to the sun to the eyes to Sethe’s face. And how about that syntax?! This particular character’s thoughts are so fluid and stream-like that there is no punctuation at all. This adds to the urgency of the passage, the fear, and, finally, the hope.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Delf, Elizabeth. "What is Stream of Consciousness?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 12 Nov. 2019, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-stream-consciousness. Accessed [insert date].

Further Resources for Teachers

William Faulkner's "Barn Burning" offers a short glimpse into the young boy Sarty's "stream-of-consciousness" thought processes. At the start of the story, Sarty identifies the man who tries to prosecute his pyromaniac father as his "father's enemy" before thinking " our enemy...ourn! mine and hisn both! He's my father! "

Writing Prompt: How does the form of Sarty's thoughts relate to the stream-of-consciousness form described in the above video? What anxieties or tensions does this repetition reveal in Sarty's worldview, and how do these tensions foreshadow later elements in the plot?

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

stream of consciousness

What is stream of consciousness definition, usage, and literary examples, stream of consciousness definition.

Stream of consciousness (stuhREEM uhv CAHN-shush-niss) is a narrative technique that imitates the nonlinear flow of thought. The term originates from 19th-century psychology and later became associated with literature as psychological theories began to influence late 19th- and early 20th-century fiction.

The History of Stream of Consciousness

The term originated in William James’s 1890 book The Principles of Psychology , in which he compares thought to a stream. At the time, the contemporary belief was that thought worked as an organized chain.

Stream of consciousness, however, was already emerging in literature before James’s text; it appeared in works like Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy , Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Anna Karenina . However, the technique wouldn’t come to prominence until it began appearing throughout modern literature as psychology became a subject of interest to early 20th-century writers.

Irish author James Joyce is a notable proponent of this technique, using it in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man , Ulysses , and Finnegan’s Wake . Other authors of the time, like Virginia Woolf, used stream of consciousness as well. The technique’s relevance progressed into the second half of the 20th century and into the present day. More contemporary works that utilize the technique include Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar , Toni Morrison’s Beloved , Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting , and Brendan Connell’s The Life of Polycrates and Other Stories for Antiquated Children .

Elements of Stream of Consciousness

Stream of consciousness is characterized by its lack of linearity, which is evident in the technique’s grammar and word order, ambiguous transitions , repetition, and nonlinear plot structure or narration. Since stream of consciousness is meant to depict thought, we experience it every day. Stream of consciousness may appear as follows:

“Look at that kitten sitting on the bin outside. Did I sort through the recycling—crap, I think I threw away my debit card this morning before breakfast I really want a coffee now.”

In the example, thoughts are only loosely connected, change abruptly, and appear as run-on sentences to show the unbroken flow between the thoughts.

Why Writers Use Stream of Consciousness

This technique can depict the chaotic and disorganized nature of human thought. As a result, readers witness the complexity of characters’ minds in real time, allowing a clearer view of characters’ emotional and psychological state. This develops the reader’s connection to the character and makes the reader pay close attention to the character’s disjointed thoughts to better understand them.

Stream of Consciousness vs. Internal Monologue

Internal monologues and stream of consciousness are similar in concept but distinct in execution. Both involve internal thoughts, but while stream of consciousness renders the messy, fragmented human thought process, internal monologues follow traditional grammatical and structural rules to maintain full. Stream of consciousness thus seeks to let the audience experience what the character is thinking or feeling as it naturally occurs, whereas internal monologues are explicit, coherent statements of what the character is thinking or feeling.

Stream of Consciousness vs. Freewriting

Freewriting is an idea-generating technique that writers use to combat writers’ block. In an effort to spark creativity, writers will jot down anything that comes to mind rather than attempt to coherently organize their thoughts at the beginning of the writing process. Freewriting is similar to stream of consciousness in that the ideas are written down as they come to the writer organically.

However, after freewriting, writers are meant to sort through this material to find useable content that can be turned into a story. Stream of consciousness, on the other hand, is an aspect of a finished story—although the writer has created the effect of nonlinear thought, the precise wording and structure of these thoughts are purposeful.

Writers Known for Stream of Consciousness

Some writers most known for this technique are Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, William Faulkner, and Marcel Proust, though other prominent writers who have used this technique include Sylvia Plath and Jonathan Safran Foer.

Examples of Stream of Consciousness in Literature

1. James Joyce, Ulysses

In this excerpt, Leopold Bloom’s thoughts transition to his younger self:

He is young Leopold, as in a retrospective arrangement, a mirror within a mirror (hey, presto!), he beholdeth himself. That young figure of then is seen, precious manly, walking on a nipping morning from the old house in Clambrassil to the high school, his book satchel on him bandolier wise, and in it a goodly hunk of wheaten loaf, a mother’s thought.

Joyce accomplishes this transition by creating a continuous narrative flow of Bloom’s thoughts to his past experiences, bringing the reader along for his mental journey back in time.

2. Toni Morrison, Beloved

In this excerpt, Beloved is frantically clinging to life:

I am alone I want to be the two of us I want the join I come out of blue water after the bottoms of my feet swim away from me I come up I need to find a place to be the air is heavy I am not dead I am not there is a house there is what she whispered to me I am where she told me I am not dead I sit the sun closes my eyes when I open them I see the face I lost Sethe’s is the face that left me Sethe sees me see her and I see the smile her smiling face is the place for me it is the face I lost she is my face smiling at me

Beloved’s fear of death and desire to be with Sethe are communicated through disjointed, unpunctuated, and repetitive thoughts. The use of stream of consciousness underscores her panic and urgent desire to see Sethe.

3. T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

In this excerpt, Eliot’s speaker jumps from one thought to the next as he considers mortality:

I grow old … I grow old …

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled. Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each. I do not think that they will sing to me.

As the speaker struggles to understand death, he attempts to communicate his state of mind, and his flow of thoughts jump from one subject to the next.

Further Resources on Stream of Consciousness

Oregon State University has a concise YouTube video on the topic.

The School of Life has also created a video on the topic with additional examples.

Related Terms

- Freewriting

- Internal Monologue

- Perspective

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

Stream of Consciousness: A Literary Device

Stream of Consciousness is a literary narrative technique that aims to depict the continuous, unfiltered flow of thoughts, feelings, and perceptions within a character’s mind in real-time.

Etymology of Stream of Consciousness

Table of Contents

The term “Stream of Consciousness” in the context of literary technique originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, primarily associated with the works of authors such as James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. The etymology of this phrase is rooted in psychology and philosophy.

It reflects the idea of capturing the continuous flow of thoughts, feelings, and perceptions within an individual’s mind as they occur, much like a stream that flows uninterrupted. Stream of consciousness as a narrative style seeks to delve deep into the inner workings of characters’ minds, offering readers a direct, unfiltered glimpse into their inner thoughts and experiences.

This literary technique serves to explore the complexities of human consciousness and the subjective nature of perception, allowing for a deeper understanding of characters’ motivations and the intricacies of their inner worlds.

Meaning of Stream of Consciousness

Definition of stream of consciousness.

It often eschews traditional punctuation and structure to capture the fluidity and subjectivity of human consciousness. This technique provides readers with an intimate and immersive insight into a character’s inner thoughts and experiences, emphasizing the complexity and uniqueness of individual mental landscapes.

Common Features of and Stream of Consciousness

- Interior Monologue : Characters’ inner thoughts and mental processes are depicted in a continuous, unbroken flow, often mirroring the way thoughts naturally occur in the mind.

- Real-Time Rendering : The narrative seeks to capture thoughts as they happen, providing readers with an immediate and immersive experience of the character’s consciousness.

- Subjectivity : The narrative highlights the highly subjective nature of human perception, emphasizing that each character’s thoughts and experiences are unique and influenced by personal history and emotions.

- Fragmentation : Traditional punctuation and linear structure are frequently disregarded, leading to fragmented and nonlinear storytelling that reflects the chaotic and interconnected nature of thought.

- Multiple Perspectives : Different characters’ streams of consciousness may be presented within the same work, allowing readers to explore the inner worlds of various characters.

- Psychological Depth : Authors use this technique to delve deeply into characters’ psyches, often revealing their motivations, fears, desires, and subconscious associations.

- Temporal Fluidity : Time can be fluid in stream of consciousness narratives, with past, present, and future thoughts intermingling to reflect the non-linear nature of memory and perception.

- Immediate Sensations : The style can capture immediate sensory experiences, including sensory perceptions such as sights, sounds, smells, and tactile sensations.

- Introspection : Characters engage in introspection and self-reflection, providing insight into their self-awareness and inner conflicts.

- Complexity and Ambiguity : The narrative style may add layers of complexity and ambiguity, encouraging readers to engage actively with the text and interpret the meaning behind fragmented thoughts.

- Modernist Literary Movement : Stream of consciousness is closely associated with the modernist literary movement of the early 20th century, challenging conventional narrative structures and exploring the complexities of human consciousness.

Types of Stream of Consciousness

Common examples of stream of consciousness.

- Daydreaming : When you let your mind wander without a specific focus, you may experience a stream of consciousness. Your thoughts may flow from one idea to another, often without a clear structure or goal.

- Mindful Meditation : During mindfulness or meditation practices, you may observe your thoughts as they arise without actively trying to control or direct them. This can lead to a stream of consciousness where thoughts come and go naturally.

- Conversations : In everyday conversations, people often express their thoughts and feelings as they occur in real-time. When engaged in a spontaneous and unscripted conversation, you may notice a continuous flow of thoughts and responses.

- Journaling : When you write in a journal, especially in a freeform and unstructured way, you may find that your thoughts flow onto the page without much premeditation. This can result in a stream-of-consciousness writing style.

- Problem Solving : When you’re trying to solve a complex problem or make a decision, your thoughts may flow from one consideration to another, exploring various possibilities and weighing pros and cons.

- Creativity and Artistic Expression : Artists, writers, and musicians often tap into stream of consciousness to generate ideas and inspiration. They may let their thoughts flow freely, allowing unexpected connections to emerge.

- Reflection and Self-Analysis : During moments of self-reflection or self-analysis, you may experience a stream of consciousness as you examine your emotions, past experiences, and future aspirations.

- Dreams : While dreaming, your mind often follows a stream of consciousness, creating scenarios and narratives that can be vivid and unpredictable.

- Reading and Watching : When you read a book or watch a movie, you may find yourself mentally reacting to the content in real-time, forming opinions, making predictions, and experiencing emotional responses as the story unfolds.

- Driving or Commuting : During solitary activities like driving or commuting, your mind may wander, leading to a stream of consciousness where you reflect on various aspects of your life or engage in creative thinking.

Related posts:

- Onomatopoeia: A Literary Device

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › British Literature › Stream of Consciousness

Stream of Consciousness

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on October 7, 2022

The coining of this term has generally been credited to the American psychologist William James, older brother of novelist Henry James. It was originally used by psychologists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to describe the personal awareness of one’s mental processes. In a chapter of The Principles of Psychology titled “The Stream of Thought,” James provides a phenomenological description of this sensing of consciousness:

Consciousness, then, does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as “chain” or “train” do not describe it fitly as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows. A “river” or a “stream” are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life. (239; italics in the original).

It is helpful at the outset to distinguish stream of consciousness from free association. Stream of consciousness, from a psychological perspective, describes metaphorically the phenomena—that continuous and contiguous fl ow of sensations, impressions, images, memories, and thoughts—experienced by each person, at all levels of consciousness, that are generally associated with each person’s subjectivity, or sense of self. Free association, in contrast, is a process in which apparently random data collected from a subject allow connections to be made from the unconscious, subconscious, and preconscious to the conscious mind of that subject. Translated and mapped to the space of narrative literatures, free association can be one element in the means used to signify the stream of consciousness.

William James / Wikimedia

As a literary term, stream of consciousness appears in the early 20th century at the intersection of three apparently disparate projects: the developing science of psychology (e.g., investigations of the forms and manifestations of consciousness, as elaborated by Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, James, and others), the continuing speculations of Western philosophy as to the nature of being (e.g., investigations of consciousness in time by Henri Bergson), and reactionary forces in the arts that were turning away from realism in the late 19th century in favor of exploring a personal, self-conscious subjectivity. The psychological term was appropriated to describe a particular style of novel or technique of characterization that was prevalent in some fictional works, which relied on the mimetic representation of the mind of a character and which dramatized the full range of the character’s consciousness by direct and apparently unmediated quotation of such mental processes as memories, thoughts, impressions, and sensations. Stream of consciousness, constituting as it did the ground of self-awareness, was consequently extended to describe narratives and narrative strategies in which the overt presence of the author/narrator was suppressed in favor of presenting the story exclusively through the thought of one or more of the characters in the story. Examples of stream of consciousness techniques can arguably be found in narratives written during the last several centuries, including works by Rhoda Broughton and Lucy Clifford in the 19th century. Generally speaking, however, the British writers who are most often cited as exemplars of the stream of consciousness technique are associated with the high modern period of the early 20th century: Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, May Sinclair, and Dorothy Richardson.

Bearing in mind the origin of the term, it is easy to see why some Anglo-American literary critics and theorists have subsumed all textual manifestations of the mental activity of characters in a narrative under the overarching term stream of consciousness. While convenient, this tendency belies the rich range and depth of narrative methods for representing a character’s consciousness, often best described by the terms originally naming them. Consider, for example, the interior monologue, in which, a running monologue—similar to those we all experience inside our own minds but that we cannot experience in the minds of others except in fictional narrative—is textually rendered as the unmediated but articulated, logical thoughts of a fictional character. That this monologue is unmediated, presented to the reader without either authorial or narratorial intervention or the common textual signs associated with narrative speech (e.g., quotation marks or attributive verbs), is crucial to establishing in the reader the sense of access to the consciousness of the character. That it is logical and respects grammatical form and syntax, as opposed to appearing as a random collection of disconnected thoughts and images, distinguishes it from another textual rendering of the stream of consciousness, that of sensory impression.

Sensory impression, as a mode of representing the stream of consciousness, occurs as simple lists of a character’s sensations or impressions, sometimes with ellipses separating them. These unconscious or preconscious sensory impressions represent the inarticulable thoughts, the imaginings of a character that are not experienced as words. To prevent the free associations that stem from such sensory impressions from running away with and destroying the flow and integrity of the narrative, a story must somehow be anchored within the stream of consciousness. One method is a recurring motif or theme. The motif appears on the surface of a character’s thoughts and then disappears among the flow of memories, sensations, and impressions it initiates only to resurface some time later, perhaps in a different form, to pull the story back up into the consciousness of both the character and the reader. Consider the example of Virginia Woolf’s short story “The Mark on the Wall.” The story begins as a meditation, which could easily be read as a spoken monologue, on a series of recollected events but quickly turns, through the motif of a mark seen by the narrator over a mantlepiece on the wall, to a nearly random stream of loosely connected memories and impressions. As the story progresses, the mark and speculations as to its nature and origin appear and disappear as a thread running in and out, binding the loose folds of the narrator’s recollections to one another. The narrator’s stream of consciousness ranges widely over time and space, whereas the narrator quite clearly remains bound to a particular place and time, anchored—seemingly—by the mark on the wall.

While not generally considered a textual manifestation of stream of consciousness in the conventional sense—in part because it is associated with third-person rather than first-person narration—another method of representing the consciousness of characters is free indirect discourse, or reported or experienced speech. Consider the following, from the ending paragraphs of Joyce’s short story “The Dead”:

He wondered at his riot of emotions an hour before. From what had it proceeded? From his aunt’s supper, from his own foolish speech, from the wine and dancing, the merry-making when saying good-night in the hall, the pleasure of the walk along the river in the snow. Poor Aunt Julia! She, too, would soon be a shade with the shade of Patrick Morkan and his horse. (222)

The first sentence is clearly the narrator telling what the character, Gabriel, is thinking; but with the second sentence comes a transition in the form of a series of sensory impressions that moves the reader to Gabriel’s own conscious thoughts. In the end, it is not the narrator who thinks, “Poor Aunt Julia!”

BIBLIOGRAPHY Cohn, Dorrit. Transparent Minds: Narrative Modes for Presenting Consciousness in Fiction. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978. Bowling, Lawrence Edward. “What Is the Stream of Consciousness Technique?” PMLA 65, no. 4 (1950): 333–345. James, William. The Principles of Psychology. 1890. New York: Dover Publications, 1950. Joyce, James. Dubliners. 1916. New York: The Viking Press, 1967. Woolf, Virginia. The Complete Shorter Fiction of Virginia Woolf. 2nd ed. New York: Harcourt, 1989.

Share this:

Categories: British Literature , Literary Terms and Techniques , Literature , Short Story

Tags: Define Stream of Consciousness , Definition of Stream of Consciousness , stream of consciousness , Stream of Consciousness Define , Stream of Consciousness Defintion , Stream of Consciousness Examples , Stream of Consciousness Method , Stream of Consciousness Novels , Stream of Consciousness Practitioners , Stream of Consciousness Story , Stream of Consciousness Technique , Stream of Consciousness Writings , The Stream of Thought , William James

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment.

To the Lighthouse

Virginia woolf, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Woolf employs a stream-of-consciousness style of narration throughout To the Lighthouse as a crucial tool to manipulate the pacing of her narrative and slow it down to the speed of her characters' thoughts. Consider how Woolf follows Mrs. Ramsay's mind in the following passage, from Chapter 1 of "The Window":

If she finished it to-night, if they did go to the Lighthouse after all, it was to be given to the Lighthouse keeper for his little boy, who was threatened with a tuberculous hip; together with a pile of old magazines, and some tobacco, indeed whatever she could find lying about, not really wanted, but only littering the room, to give those poor fellows who must be bored to death sitting all day with nothing to do but polish the lamp and trim the wick... Cite this Quote

Because stream-of-consciousness narration follows a realistic articulation of thoughts as they wander from subject to subject, the reader reads the characters' thoughts at the very rate at which they occur in the characters' minds, as observed by Woolf's omniscient narrator. By setting the pace of the novel with this stream-of-consciousness technique, Woolf is able to give the reader a glimpse into the Ramsays' world in its full complexity: by the time "The Window" section draws to a close, after a 150 pages, only a day has passed. Through this view of the world in To the Lighthouse , Woolf is able to give the reader a high-resolution account of the characters' interior lives as they experience life, death, and—whether they like it or not—the passage of time.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

9 Stream of Consciousness

Dora Zhang is Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature at University of California, Berkeley. She is author of Strange Likeness: Description and the Modernist Novel (2020).

- Published: 11 August 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Few terms are more associated with the innovations of modernist fiction—and Virginia Woolf’s novels in particular—than ‘stream of consciousness’, yet the contours of the term often remain vague. This chapter argues that Woolf makes distinctive contributions to the genre that have been underrecognized both because of its gendered association with formlessness, and because stream of consciousness is often simply conflated with interior monologue, which she mostly did not use. Instead, Woolf’s contributions include her use of free indirect discourse to overcome the egotism of the first person, experiments with rendering collective streams of consciousness in Between the Acts , and finally, her use of analogies to evoke the feeling of thinking, which also illuminates unappreciated links to William James, the psychologist who coined the term together, Woolf’s strategies refute the charge of intense individualism that is often levied at stream-of-consciousness writing.

Few terms are as associated with the formal innovations of the modernist novel as stream of consciousness , a mode of writing that records the flickering parade of impressions across a character’s mind from a subjective point of view. Pioneered in the English tradition by Dorothy Richardson and James Joyce, Virginia Woolf is acknowledged to be one of its most skilled practitioners. But despite the ubiquitous familiarity of the term in general, and its association with Woolf in particular, her innovations in this arena have not been clearly recognized. This stems first of all from a confusion over whether the term refers to a particular stylistic technique, or whether it refers to something like a genre, constituted by shared themes. 1 ‘Stream of consciousness’ is often used interchangeably with one particular technique: interior monologue. However, this conflation is misleading, and I will use the term to refer to a genre that employs many aesthetic strategies, among which interior monologue is just one. 2 By expanding its definition, we are better equipped to appreciate the range of techniques that make up stream-of-consciousness texts, and Woolf’s contributions in particular. For while it is famously associated with irregular or absent punctuation, fragmented or incomplete sentences, ellipses, and discontinuous syntax, as in Molly Bloom’s soliloquy at the end of Ulysses , Woolf’s innovations in stream of consciousness writing announce themselves more quietly. Moreover, a gendered association of the genre with the personal, the private, the small, and the detail has led writing by women to be more often considered ‘formless’, obscuring the precise nature of their formal contributions.

Woolf’s contributions to stream of consciousness include at least three features, which form my focus here. First, I will look at her virtuosic use of free indirect discourse, which enables her to shift perspectives with unparalleled fluidity, and which in turn allows her to overcome what she herself felt was the great drawback of the novel of subjective experience: the egotism of the first person. Second, I examine Woolf’s experiments with evoking a collective stream of consciousness in her late novel Between the Acts . While there are dangers to collective thinking, as Woolf, a vocal critic of fascism, was well aware, she was also drawn to moments of shared perception as a way of overcoming individual isolation. Third, I make the case that her use of analogies, something not ordinarily associated with stream of consciousness, constitutes an important technique of this genre. These analogies, which are directed above all at conveying the feeling of being conscious, also illuminate unappreciated links between Woolf and William James, the psychologist who popularized the term. Taken together, Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness strategies refute a major critique of this genre: its intense individualism and liability to lapse into solipsism.

Early Tributaries

But first, let us return to the head of the stream. The term is usually credited to William James, specifically the famous ‘Stream of Thought’ chapter of his 1890 Principles of Psychology . 3 Insisting on the continuous rather than successive nature of thought, James writes:

Consciousness … does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as ‘chain’ or ‘train’ do not describe it fitly as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows. A ‘river’ or a ‘stream’ are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life. 4

Literary commentators have rarely paid close attention to the meaning of this term and its significance in James, and I will return to his affiliations with Woolf towards the end of the chapter. Suffice it for now to note that James was deploying the metaphor in order to refute Associationism, the prevailing theory of mind at the time in which substantive thoughts occurred in consciousness discretely and discontinuously. For James, the problem with Associationism was that it tended to both emphasize and atomize the terms being associated (i.e. ideas) at the expense of the actual association (i.e. the relations) between them. As we will see, it was precisely these relations that Woolf, too, sought to capture.

The literary usage of ‘stream of consciousness’ was first introduced by May Sinclair in a 1918 review of Dorothy Richardson’s novels in The Egoist . ‘Nothing happens’, Sinclair wrote, ‘It is just life going on and on. It is Miriam Henderson’s stream of consciousness going on and on.’ 5 From the first, this mode was understood as an attempt to obtain direct contact with its object—called variously consciousness, experience, reality, or life—without mediation or intervention, and freed from the falsification of plot and story. Joyce and Richardson were cited as pioneers of the method, but Woolf ’s name was rarely absent from any discussion, usually evoked as one of its most prominent practitioners. So in a 1926 article in The Atlantic defending stream-of-consciousness fiction from those who called it ‘an eccentric fad’, Ethel Wallace Hawkins wrote, ‘the evolution—or, more accurately, the gradual intensification—of this method may best be traced in the three novels of Virginia Woolf— The Voyage Out , Jacob’s Room , and Mrs Dalloway . 6 By the end of the 1920s, after the publication of Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse , as well as nine volumes of Richardson’s Pilgrimage sequence, Ulysses , and The Sound and the Fury , stream of consciousness had become the hallmark of the modern novelist. 7 Joseph Warren Beach and Percy Lubbock both used the term in their influential treatises on the craft of fiction, and by 1927, the phrase was familiar enough that the American writer and critic Katherine Fullerton Gerould could write in The Saturday Review , ‘I do not know whence the phrase came, nor does it matter, since it has become familiar to us all within the last decade.’ 8

Genre and Gender

While stream of consciousness quickly spread across the literary landscape in the early twentieth century, it was not universally praised. Common criticisms charged it with tedium, self-absorption, and triviality. Lamenting the absence of drama and action in the style, Gerould concluded, ‘the dullness of books like “Dark Laughter” and “Mrs Dalloway” almost makes the comic strips seem amusing’; and D.H. Lawrence famously remarked caustically, ‘ “Did I feel a twinge in my little toe or didn’t I”, asks every character of Mr Joyce, Miss Richardson or M. Proust.’ 9 Although these criticisms extended to male as well as female writers, it is important to note that stream of consciousness was, from the first, discussed in gendered terms. The idea that the genre was formless, that it was concerned only with trivialities, and that it was self-involved were all cast in terms of gendered binaries: soft versus hard, small versus big, internal versus external, and individual versus social. It also fell on one side of a gendered divide within the tropology of modernist poetics: the very metaphor of the stream, with its associations of vague, misty, amorphous flow, contrasts with the valorizations of the hard, rigid, precise, and granite in the poetics of Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, and T.E. Hulme, among others. 10 The charges of formlessness, or absent or failed design, were also levelled much more at female writers like Woolf, Richardson, and Katherine Mansfield. In contrast, a male stream-of-consciousness writer like Joyce was more often credited with being guided by intellect rather than ‘intuition’ or ‘impression’, and what might be called the absence of form in one context became innovative and revolutionary in another. 11 Stream-of-consciousness writing was and, in many ways, remains associated with the delicate, the miniature, the precious, and disorganized detail over the cohesive pattern—all decidedly feminized traits. 12

At the same time, the supposedly feminine nature of this style was sometimes a rallying cry for its practitioners. In a 1938 foreword to Pilgrimage Richardson characterized her project as forging a new literary form in an attempt ‘to produce a feminine equivalent of the current masculine realism’. 13 Feminine prose, she wrote, ‘should properly be unpunctuated, moving from point to point without formal obstructions’. 14 In reviewing volumes of Pilgrimage , Woolf too aligned Richardson’s linguistic innovation with her womanhood. ‘She has invented … a sentence which we might call the psychological sentence of the feminine gender. It is of a more elastic fibre than the old, capable of stretching to the extreme, of suspending the frailest particles, of enveloping the vaguest shapes’ ( E 3 367). We cannot fail to be reminded here of Woolf’s own formulation of the aim of the novel in manifestos such as ‘Modern Fiction’. While conceding that Richardson is working on ‘an infinitely smaller scale’, Woolf does not hesitate to rank her achievement with that of Chaucer, Donne, and Dickens, each of whom has also shown that the heart ‘is a body which moves perpetually, and is thus always standing in a new relation to the emotions which are its sun’ ( E 3 367).

In alluding to the smallness of the scale on which Richardson is working, Woolf is highlighting a criticism that she herself often encountered. The charge of triviality levelled at stream-of-consciousness texts depends on assumptions about whose interiority is worthy of representation, and whose experience can stand for broader conditions or reach out toward larger social, historical threads, instead of remaining confined to the personal. Woolf herself resisted the usual hierarchies of size and value, insisting, ‘let us not take it for granted that life exists more fully in what is commonly thought big than in what is commonly thought small’ ( E 4 161). We may certainly take her to task for not expanding the purview of her own representations of consciousness beyond a relatively narrow segment of the upper middle class, but this does not thereby negate the importance of her assertion that ‘everything is the proper stuff of fiction’ ( E 4 164). 15