- Search for: Search

Complementary Goods: Definition & Examples

Complementary Goods Definition

A Complementary good is a product or service that adds value to another. In other words, they are two goods that the consumer uses together. For example, cereal and milk, or a DVD and a DVD player.

On occasion, the complementary good is absolutely necessary, as is the case with petrol and a car. However, a complementary good can add value to the initial product. For instance, pancakes and maple syrup.

- A complementary good is a good that adds value to another, or, a good that cannot be used without each other.

- Complementary goods that cannot be used without each other are known to have a strong relationship. In other words, when the price goes up on one, the demand goes down for the other good.

- Examples include: Tennis Balls and Tennis Racket; PlayStations and Games; Movies and Popcorn; and Mobile Phones and Sim Cards.

Complementary Goods have a negative relationship with each other – which means that when product X increases in price, demand for product Y falls. This is because fewer people buy product X due to the higher price. As a result, fewer people are also buying product Y, which only adds value to product X. In economic jargon, this is known as ’negative cross-elasticity of demand’ .

Let us consider an iPhone. If its price increases by 10 percent, this may lead to lower levels of demand. At the same time, if fewer people are buying iPhones, then there are also fewer people buying iPhone cases. It is because of this relationship that we can consider these as complementary goods.

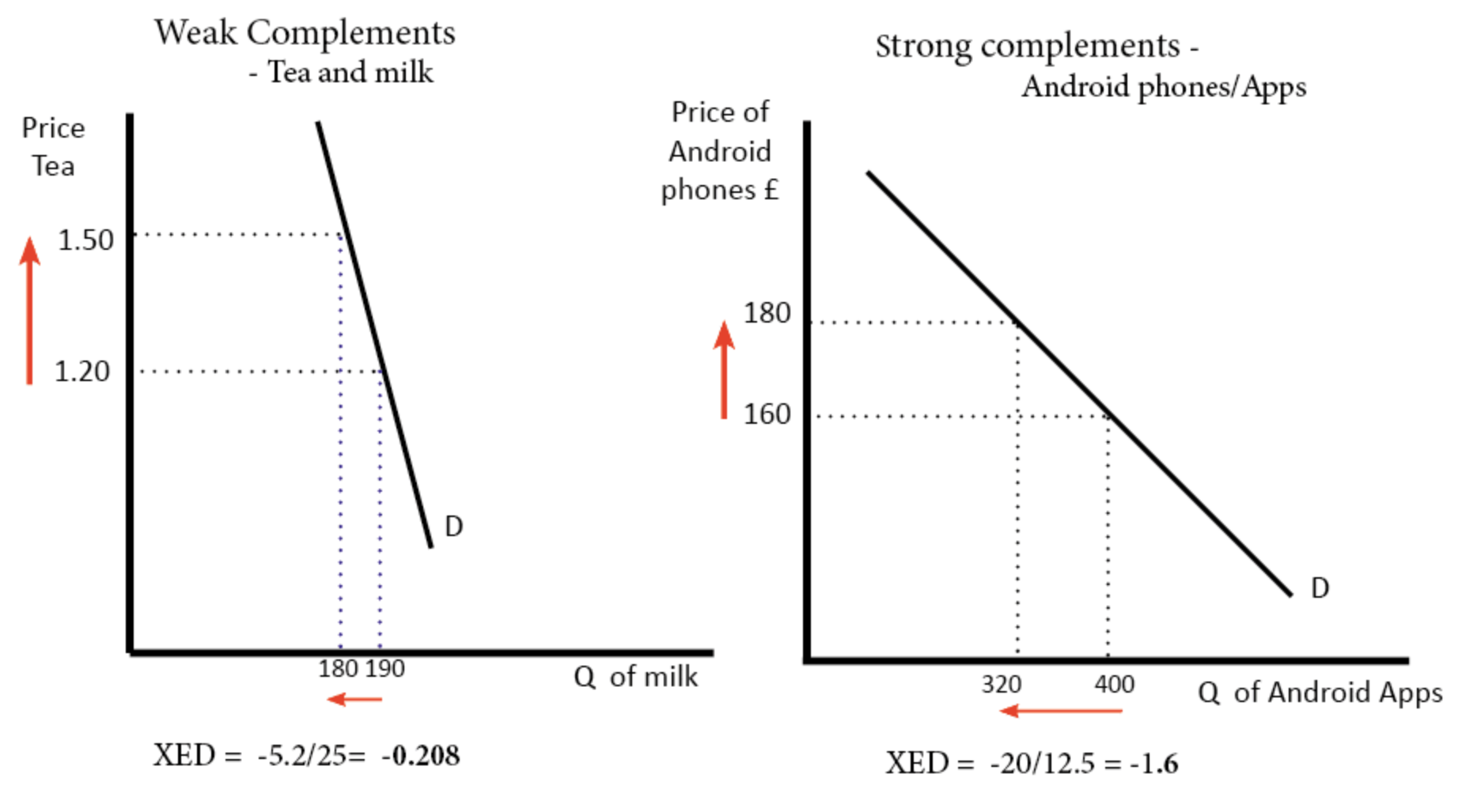

Weak Complementary Goods

Not all complementary goods are the same. There are ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ complementary goods. Weak complementary goods respond to increases in prices in a very limited way. In other words, they are not responsive to increases in prices of complementary goods. However, there is some connection between the two.

If we take pancakes and maple syrup as an example – they are two complementary goods. Consumers use maple syrup with pancakes, but they also use other toppings. For instance, consumers may use bananas or sugar instead. Therefore, whilst maple syrup is used to complement pancakes, there are many other alternatives that make the relationship between the two weak.

If the price of maple syrup increases by 10 percent, but the demand for pancakes falls by 1 percent, the relationship is therefore weak. This is because the price increase of the complementary product has little effect on the demand on the other.

Strong Complementary Goods

Strong Complementary Goods have a close relationship with each other. That is to say that one good is reliant on the other to add value. For example, we have a DVD and a DVD player. These are known as strong complementary goods because they are pretty useless without one another.

The relationship between strong complementary goods is very elastic. In other words, when the price of DVD players rise, the demand for DVDs is likely to fall. So we can say there is a ‘ negative cross-elasticity’ between them. In fact, if you look at any product that could not be sold by itself – it is likely a strong complementary good. So if you could only use Product X if you first had Product Y, then they are strong complementary goods.

Complementary Goods Graph

As we can see from the graph below; when the price of an iPhone decreases, the demand for iPhone cases increases. This is because the demand for iPhones increases as more consumers are buying it at the lower prices. In turn, those same consumers are demanding iPhone cases – which translates into high sales.

Complementary Goods Examples

Complementary goods are goods which rely on each other to add value. There are a large number of complementary goods which are necessary in order for the other to work. For example, petrol is needed for cars to work. However, there are also weak complementary goods that are not necessarily needed in order to function. An iPhone does not need a phone case in order to work, but is still classed as a complementary good. Other examples include:

- Tennis Balls and Tennis Racket

- Mobile Phones and Sim Cards

- Petrol and Cars

- Burger and Burger Buns

- PlayStation and Games

- Movies and Popcorn

- Shoes and Insoles

- Pencils and Notebooks

A Complementary good can be a product or service that is sold separately that adds value to another. In other words, they are two or more goods that are used together.

Substitute goods are two goods that can be used i n place of one another , for example, Dominos and Pizza Hut. By contrast, complementary goods are those that are used with each other . For example, pancakes and maple syrup. The key difference is that substitute goods replace one another, whilst complementary goods add value to the other.

Some examples of complementary goods include: 1. Tennis Balls and Tennis Racket 2. Mobile Phones and Sim Cards 3. Petrol and Cars 4. Burger and Burger Buns 5. PlayStation and Games 6. Movies and Popcorn 7. Shoes and Insoles 8. Pencils and Notebooks

Paul Boyce is an economics editor with over 10 years experience in the industry. Currently working as a consultant within the financial services sector, Paul is the CEO and chief editor of BoyceWire. He has written publications for FEE, the Mises Institute, and many others.

Further Reading

Find Study Materials for

- Explanations

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

- Flashcards Create and find the best flashcards.

- Notes Create notes faster than ever before.

- Study Sets Everything you need for your studies in one place.

- Study Plans Stop procrastinating with our smart planner features.

- Complementary Goods

Aren't PB&J, chips and salsa, or cookies and milk perfect duos? Of course, they are! Goods that are usually consumed together are called complementary goods in economics. Keep reading to learn the definition of complementary goods and how their demand is intertwined. From the classic complementary goods diagram to the effect of price changes, we'll explore everything you need to know about this type of goods. Plus, we'll give you some examples of complementary goods that make you want to grab a snack! Don't confuse them with substitute goods ! We'll show you the difference between substitute goods and complementary goods too!

Create learning materials about Complementary Goods with our free learning app!

- Instand access to millions of learning materials

- Flashcards, notes, mock-exams and more

- Everything you need to ace your exams

- Asymmetric Information

- Consumer Choice

- Budget Constraint

- Budget Constraint Graph

- Consumer Preferences

- Corner Solutions

- Income and Substitution Effect

- Indifference Curve

- Marginal Rate of Substitution

- Marginal Utility

- Revealed Preference

- Risk Preference

- Risk Reduction

- Risk-Return Trade Off

- Substitute Goods

- Substitutes vs Complements

- Utility Functions

- Economic Principles

- Factor Markets

- Imperfect Competition

- Labour Market

- Market Efficiency

- Microeconomics Examples

- Perfect Competition

- Political Economy

- Poverty and Inequality

- Production Cost

- Supply and Demand

Complementary Goods Definition

Complementary goods are products that are typically used together. They are goods that people tend to buy at the same time because they go well together or enhance each other's use. A good example of complementary goods would be tennis rackets and tennis balls. W hen the price of one good goes up, the demand for the other also goes down, and when the price of one good goes down, the demand for the other goes up.

Complementary goods are two or more goods typically consumed or used together, such that a change in the price or availability of one good affects the demand for the other good.

A good example of complementary goods would be video games and gaming consoles. People who buy gaming consoles are more likely to buy video games to play on them, and vice versa. When a new gaming console is released, the demand for compatible video games usually increases as well. Similarly, when a new popular video game is released, the demand for the gaming console it is compatible with may also increase.

What about a good whose consumption does not change when the price of other good changes? If price changes in two goods do not affect the consumption of either of the goods, economists say that the goods are independent goods.

Independent goods are two goods whose price changes do not influence the consumption of each other.

Complementary Goods Diagram

The complementary goods diagram shows the relationship between the price of one good and the quantity demanded of its complement. T he price of Good A is plotted on the vertical axis, whereas the quantity demanded of Good B is plotted on the horizontal axis of the same diagram.

As Figure 1 below demonstrates, when we plot the price and quantity demanded of complementary goods against each other, we get a downward-sloping curve, which shows that the quantity demanded of a complementary good increases as the price of the initial good decreases. This means that consumers consume more of a complementary good when the price of one good decreases.

Effect of Price Change on Complementary Goods

The effect of price change on complementary is that the increase in the price of one good causes a decrease in demand for its complement. It is measured using cross price elasticity of demand .

Cross price elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in the quantity demanded of one good in response to a one percent change in the price of its complementary good.

It is calculated using the following formula:

\(Cross\ Price\ Elasticity\ of\ Demand=\frac{\%\Delta Q_D\ Good A}{\%\Delta P\ Good\ B}\)

- I f the cross price elasticity is negative , it indicates that the two products are complements , and an increase in the price of one will lead to a decrease in the demand for the other.

- If the cross price elasticity is positive , it indicates that the two products are substitutes , and an increase in the price of one will lead to an increase in the demand for the other.

Let's say that the price of tennis rackets increases by 10%, and as a result, the demand for tennis balls decreases by 5%.

\(Cross\ Price\ Elasticity\ of\ Demand=\frac{-5\%}{10\%}=-0.5\)

The cross price elasticity of tennis balls with respect to tennis rackets would be -0.5, indicating that tennis balls are a complementary good for tennis rackets. When the price of tennis rackets increases, consumers are less likely to purchase balls, decreasing the demand for tennis balls.

Complementary Goods Examples

Examples of complementary goods include:

- Hot dogs and hot dog buns

- Chips and salsa

- Smartphones and protective cases

- Printer and ink cartridges

- Cereal and milk

- Laptops and laptop cases

To better understand the concept, analyze the example below.

A 20% increase in the price of fries causes a 10% decrease in the quantity demanded of ketchup. What is the cross-price elasticity of demand for fries and ketchup, and are they substitutes or complements?

\(Cross\ Price\ Elasticity\ of\ Demand=\frac{-10\%}{20\%}\)

\(Cross\ Price\ Elasticity\ of\ Demand=-0.5\)

A negative cross-price elasticity of demand indicates that fries and ketchup are complementary goods.

Complementary Goods vs Substitute Goods

The main difference between complementary and substitute goods is that complements are consumed together whie substitute goods are consumed in place of each other. Let's break the differences down for better understanding.

Complementary Goods - Key takeaways

- Complementary goods are products that are typically used together and influence each other's demand.

- The demand curve for complementary goods is downward sloping, indicating that an increase in the price of one good decreases the quantity demanded of the other good.

- The cross price elasticity of demand is used to measure the effect of price changes on complementary goods.

- A negative cross price elasticity means that the goods are complements, while a positive cross price elasticity means that they are substitutes.

- Examples of complementary goods include hot dogs and hot dog buns, smartphones and protective cases, printer and ink cartridges, cereal and milk, and laptops and laptop cases.

- The main difference between complementary and substitute goods is that complementary goods are consumed together while substitute goods are consumed in place of each other.

Learn with 0 Complementary Goods flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Complementary Goods

What are complementary goods?

Complementary goods are products that are typically used together and influence each other's demand. An increase in the price of one good decreases the quantity demanded of the other good.

How do complementary goods affect demand?

Complementary goods have a direct impact on the demand for each other. When the price of one complementary good increases, the demand for the other complementary good decreases, and vice versa. This is because the two goods are typically consumed or used together, and a change in the price or availability of one good affects the demand for the other good

Do complementary goods have derived demand?

Complementary goods do not have derived demand. Consider the case of coffee and coffee filters. These two goods are typically used together - coffee is brewed using a coffee maker and a coffee filter. If there is an increase in the demand for coffee, it will lead to an increase in the demand for coffee filters since more coffee will be brewed. However, coffee filters are not an input in the production of coffee; they are simply used in the consumption of coffee.

Are oil and natural gas complementary goods?

Oil and natural gas are often considered substitute goods rather than complementary goods because they can be used for similar purposes, such as heating. When the price of oil increases, consumers may switch to natural gas as a cheaper alternative and vice versa. Therefore, the cross-price elasticity of demand between oil and natural gas is likely to be positive, indicating that they are substitute goods.

What is the cross elasticity of demand for complementary goods?

The cross elasticity of demand for complementary goods is negative. This means that when the price of one good increases, the demand for the other good decreases. Conversely, when the price of one good decreases, the demand for the other good increases.

What is the difference between complementary goods and substitute goods?

The main difference between a substitute and a complement is that substitute goods are consumed in place of each other, whereas complements are consumed together.

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

StudySmarter Editorial Team

Team Complementary Goods Teachers

- 6 minutes reading time

- Checked by StudySmarter Editorial Team

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

Complementary Goods Defined

Products that are used together are called complementary goods.

Examples of Complementary Goods

- A video game console and the games that can be played on it

- Tennis rackets and tennis balls

- Mobile phones and mobile phone credit for sending texts and making calls

- An iPhone and apps

- A car and gasoline

Complementary Goods and Cross Elasticity of Demand

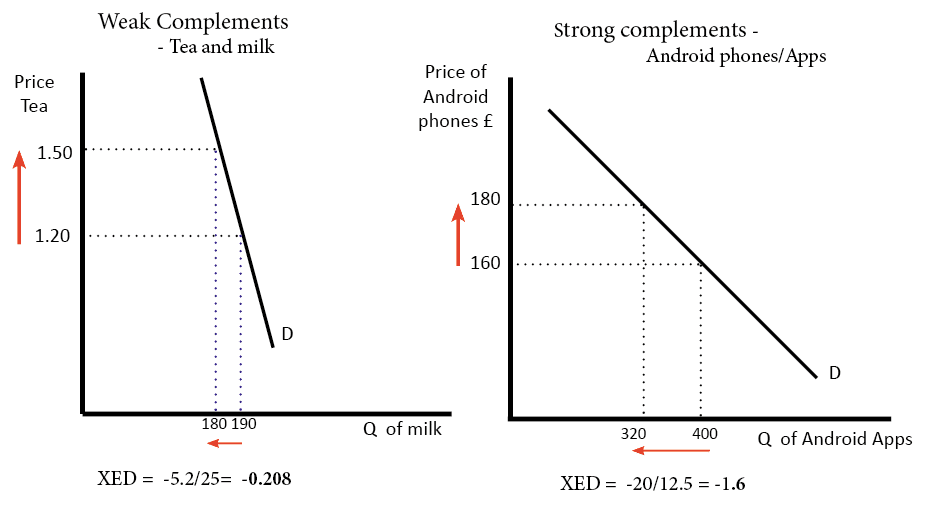

Complementary goods have a negative cross elasticity of demand. When one good’s price increases, the demand for both of the complementary goods will fall. The more closely linked these goods are, the higher the cross elasticity of demand.

If the complementary goods are only weakly linked, the cross elasticity of demand will be low. For instance, if the price of tea goes up, it’ll only have a marginal impact on the reduction of demand for tea and the consumption of milk.

But if the price of an Android phone increases, it’ll negatively affect its sales, reducing demand for Android apps.

How Firms Make Use of Complementary Goods

They increase related sales..

Supermarkets place related food items close together. You’ll see expensive pasta sauces next to pasta, for instance. The firm’s goal is to increase overall sales through the suggestion of possible related complementary goods.

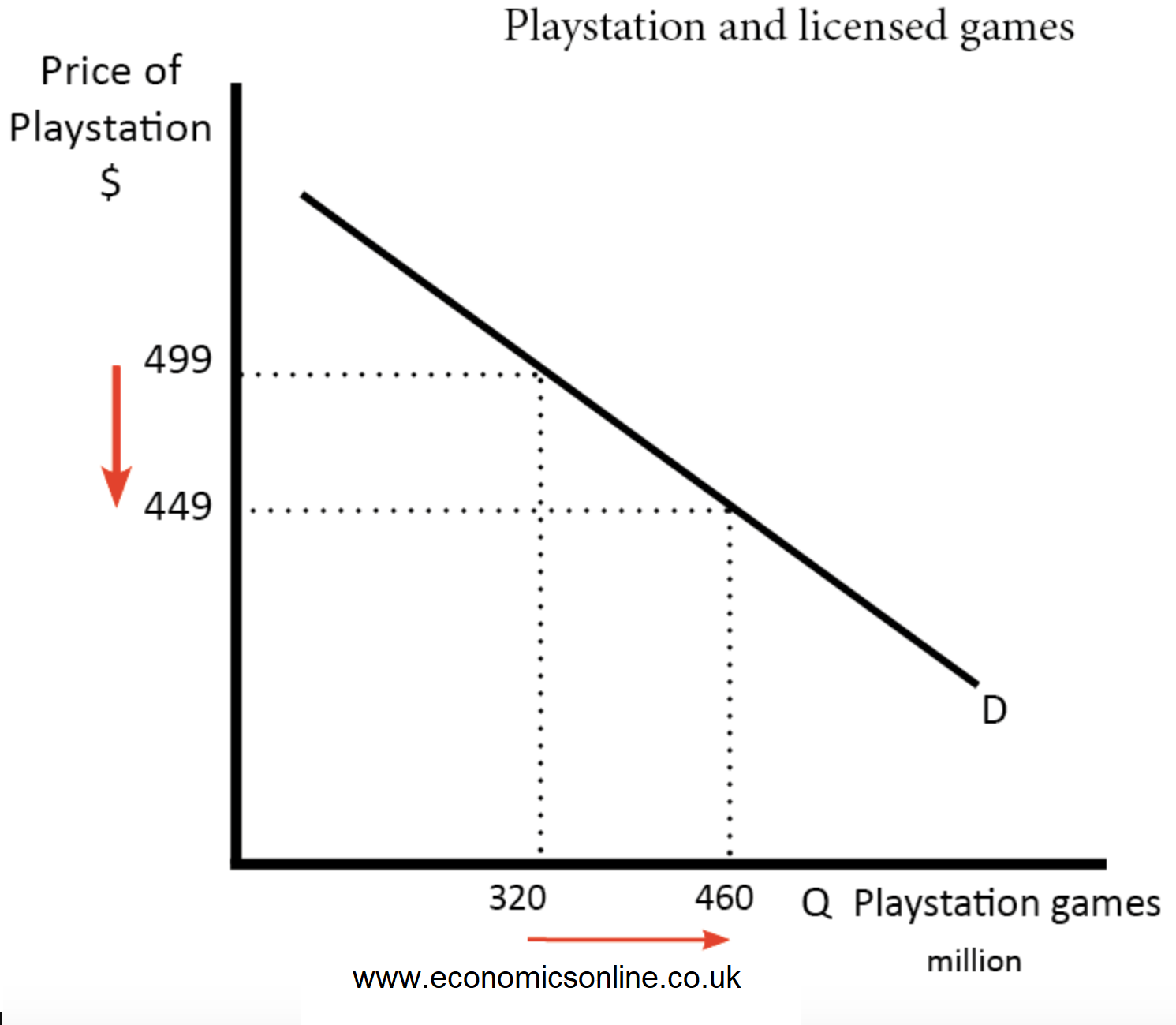

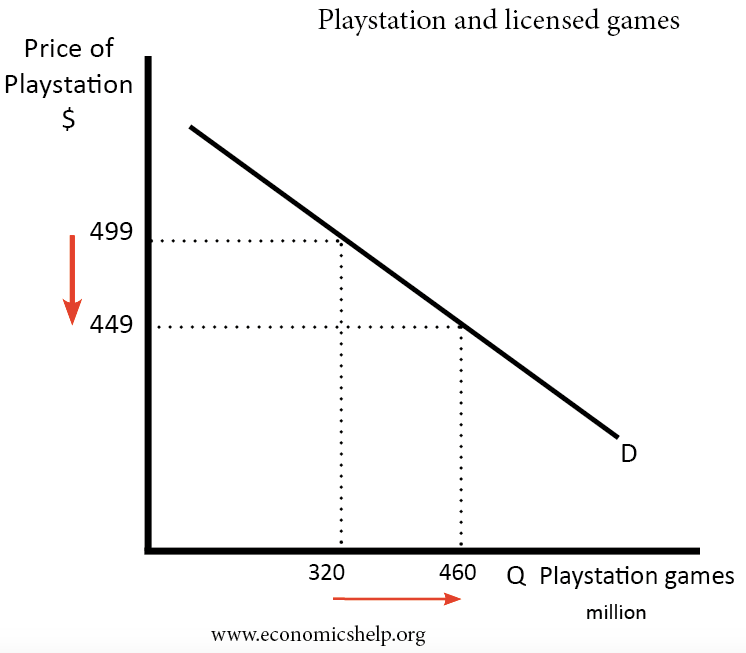

They gain loyal consumers.

Firms can also implement the strategy of offering a base product at a low price. This is because they know that when consumers purchase the base product, they can increase sales of related add-on items. The owners of PlayStation, for instance, have an incentive to decrease the price of the PlayStation itself because they will then make more sales of licensed games. This increase in revenue offsets the fall caused by the lowered price.

Cutting back on the price of videogame consoles like PlayStation can help the firm increase profits on licensed games. Similarly, many printers have low prices because the firms that manufacture them want to make the most profit by selling compatible ink.

Transforming the Automotive Supply Chain for 2022's Realities

Reserve Ratio and Money Multiplier

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

Pricing of Complementary Goods and Network Effects

We discuss the case of a monopolist of a base good in the presence of a complementary good provided either by it or by another firm. We assess and calibrate the extent of the influence of the profits from the base good that is created by the existence of complementary good, i.e., the extent of the network effect. We establish an equivalence between a model of a base and a complementary good and a reduced-form model of the base good in which network effects are assumed in the consumers’ utility functions as a surrogate for the presence of direct or indirect network effects, such as complementary goods produced by other firms. We also assess and calibrate the influence on profits of the intensity of network effects and quality improvements in both goods. We evaluate the incentive that a monopolist of the base good has to improve its quality rather than that of the complementary good under different market structures. Finally, based on our results, we discuss a possible explanation of the fact that Microsoft Office has a significantly higher price that Microsoft Windows although both products have comparable market shares.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Complementary Goods

Complementary goods are products which are used together.

- DVD player and DVD disks to play in it.

- Tennis balls and tennis rackets.

- Mobile phones and mobile phone credit for making calls.

- iPhone and Apps to use with an iPhone.

- Petrol and car.

Complementary Goods and Cross Elasticity of Demand

Complementary goods will have a negative cross elasticity of demand . If the price of one good increases, demand for both complementary goods will fall. The more closely linked the goods are, the higher will be the cross elasticity of demand.

If they are weak complementary goods then there will be a low cross elasticity of demand. For example, if the price of tea increases it will only have a marginal impact on reducing demand for tea and consumption of milk.

However, if the price of Android Phones increases, it will negatively affect sales and therefore reduce demand for Android Apps.

How firms make use of complementary goods

Increase related sales . Supermarkets will place related food items close to each other. For example, next to pasta – expensive pasta sauces. The firm hopes to increase overall sales by suggesting possible related complementary goods.

Gain loyal consumers to make related sales . Another strategy a firm can implement is to offer a base product at a low price, knowing that if consumers buy ‘base product’ they can increase sales of related (and profitable) add-on items. For example, the owners of PlayStation have an incentive to cut the price of the PlayStation itself. If they do, they know they will make increases sales of licensed games, and this increase in revenue will offset the fall in revenue from a lower price.

Reducing the price of games consoles, such as Playstation may enable the firm to make more profit on licensed games.

Many printers are sold quite cheaply because firms who manufacture printers hope to make the most profit on selling compatible ink.

- Different types of goods

- Substitute goods – the opposite of complementary goods – alternative goods.

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Economics news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Economics Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Topic Videos

Substitutes and Complements

Last updated 27 Oct 2019

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

In this micro video on the theory of demand, we look at substitute and complementary goods. You will come across these when you cover cross price elasticity of demand in introductory microeconomics.

Substitute goods

- Substitute goods are two alternative goods that could be used for the same purpose.

- They are goods that are in competitive demand

- A rise in the prices of Good S will lead to a contraction in demand for Good S

- This might then cause some consumers to switch to a rival product Good T

- This is because the relative price of Good T has fallen

- The cross-price elasticity of demand for two substitutes is positive

Examples of substitute goods:

- Tea and coffee

- Smartphone Brands

- Rival ride sharing apps

- Competing supermarket chains

- Online streaming platforms

- Cereal brands

Evaluation points on substitutes:

- Always consider the cost of substitution – there might be switching costs for consumers if they opt for a new brand

- Some products are close substitutes with a high (positive) cross price elasticity of demand

- Others are weaker substitutes especially when consumer/brand loyalty is high

Complement goods

- Complementary goods are products which are bought and used together

- A fall in the price of Good X will lead to an expansion in quantity demand for X

- And this might then lead to higher demand for the complement Good Y

- Complements are said to be in joint demand

- The cross-price elasticity of demand for two complements is negative

Examples of complement goods:

- Fish and chips

- Smartphones and apps

- Solar panels & batteries

- Flights and taxi services

- Shoes and polish

- Pasta and pasta sauces

Complement goods and product bundling

- Businesses understand that complements are bought together

- Product bundling is to offer bundles of products sold together at an attractive discount

- Substitutes

- Invisible Hand

- Cross-price elasticity of demand

- Complements

- Joint demand

You might also like

Price elasticity of demand (revision presentation).

Teaching PowerPoints

Explaining Price Elasticity of Demand and Total Revenue

Explaining price elasticity of supply.

Study Notes

Britain's biscuit shortage

6th March 2016

Different Types of Demand

The Universal Stylus Initiative - markets and complementary products

31st January 2018

Introduction to Economics and the Operations of Markets - take the Yes/No challenge

Quizzes & Activities

Adam Smith, Karl Marx and Friedrich Hayek on Economic Systems

Our subjects.

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

Complementarity of Goods and Cooperation Among Firms in a Dynamic Duopoly

- Conference paper

- First Online: 01 November 2020

- Cite this conference paper

- Mario Alberto Garcia Meza 13 &

- Cesar Gurrola Rios 13

Part of the book series: Static & Dynamic Game Theory: Foundations & Applications ((SDGTFA))

383 Accesses

We construct a simple model to show how complementarities between goods yield a possibility for cooperation between rival firms. To show this, we use a simple dynamic model of Cournot oligopoly under sticky prices. While cooperation in an oligopoly model with sticky prices is not feasible, there exists a feasible cooperation when good are perfect complements and not substitutes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The dual of Bertrand with homogenous products is Cournot with perfect complements

Endogenous Determination of Strategies in a Kantian Duopoly

On a dynamic model of cooperative and noncooperative r and d in oligopoly with spillovers.

A negative number of s would be interpreted as a reversal in the process of convergence of prices. This would mean that the prices are drifting ever apart from the natural prices of the market.

A complete detail of the calculations made for this paper can be found in the repository in https://github.com/MariusAgm/Oligopolios/tree/master/Jupyter . This includes Jupyter notebooks with the results obtained in the paper and some comprobations of the claims of the paper.

Akerlof, G.A., Yellen, J.L.: A near-rational model of the business cycle, with wage and price inertia. Q. J. Econ. 100 , 823–838 (1985)

Article Google Scholar

Akerlof, G.A., Yellen, J.L.: Can small deviations from rationality make significant differences to economic equilibria? Am. Econ. Rev. 75 (4), 708–720 (1985)

Google Scholar

Cellini, R., Lambertini, L.: Dynamic oligopoly with sticky prices: closed-loop, feedback, and open-loop solutions. J. Dyn. Control Syst. 10 (3), 303–314 (2004)

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Cournot, A.A.: Recherches sur les principes mathématiques de la théorie des richesses (1838)

Dockner, E.: On the relation between dynamic oligopolistic competition and long-run competitive equilibrium. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 4 (1), 47–64 (1988)

Duflo, E., Banerjee, A.: Poor Economics. PublicAffairs (2011)

Felzensztein, C., Deans, K.R., Dana, L.P.: Small firms in regional clusters: local networks and internationalization in the Southern Hemisphere. J. Small Bus. Manag. 57 , 496–516 (2019)

Fershtman, C., Kamien, M.I.: Dynamic duopolistic competition with sticky prices. Econometrica J. Econometric Soc. 55 , 1151–1164 (1987)

Garcia-Meza, M.A., Gromova, E.V., López-Barrientos, J.D.: Stable marketing cooperation in a differential game for an oligopoly. Int. Game Theory Rev. 20 1750028 (2018)

Gazel, M., Schwienbacher, A.: Entrepreneurial Fintech Clusters. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3309067 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3309067 (2019)

Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M.D., Green, J.R.: Microeconomic Theory. Oxford University Press (1995)

Roemer, J.E.: What Is Socialism Today? Conceptions of a Cooperative Economy. Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 2220 (2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3524617 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3524617

Sheshinski, E., Weiss, Y.: Inflation and costs of price adjustment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 44 (2), 287–303 (1977)

Simaan, M., Takayama, T.: Game theory applied to dynamic duopoly problems with production constraints. Automatica 14 (2), 161–166 (1978)

Spengler, J.J.: Vertical integration and antitrust policy. J. Polit. Econ. 58 (4), 347–352 (1950)

Yeung, D.W., Petrosjan, L.A.: Cooperative Stochastic Differential Games. Springer Science & Business Media (2006)

Zhu, X., Liu, Y., He, M., Luo, D., Wu, Y.: Entrepreneurship and industrial clusters: evidence from China industrial census. Small Bus. Econ. 52 , 595–616 (2019)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Universidad Juarez del Estado de Durango, Durango, Mexico

Mario Alberto Garcia Meza & Cesar Gurrola Rios

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mario Alberto Garcia Meza .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia

Leon A. Petrosyan

Institute of Applied Mathematical Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, Petrozavodsk, Russia

Vladimir V. Mazalov

Graduate School of Management, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia

Nikolay A. Zenkevich

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Meza, M.A.G., Rios, C.G. (2020). Complementarity of Goods and Cooperation Among Firms in a Dynamic Duopoly. In: Petrosyan, L.A., Mazalov, V.V., Zenkevich, N.A. (eds) Frontiers of Dynamic Games. Static & Dynamic Game Theory: Foundations & Applications. Birkhäuser, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51941-4_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51941-4_11

Published : 01 November 2020

Publisher Name : Birkhäuser, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-51940-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-51941-4

eBook Packages : Mathematics and Statistics Mathematics and Statistics (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Supply and Demand

- Supply Curve

- Supply Function

- Law of Supply

- Demand Curve

- Demand Function

- Law of Demand

- Market Demand

- Quantity Supplied vs Supply

- Quantity Demanded vs Demand

- Market Equilibrium

- Market Clearing Price

- Changes in Market Equilibrium

- Determinants of Supply

- Determinants of Demand

- Types of Elasticity of Demand

- Point Elasticity of Demand

- Price Elasticity of Supply

- Price Elasticity of Demand

- Elastic vs Inelastic Demand

- Cross Elasticity of Demand

- Income Elasticity of Demand

- Normal Good vs Inferior Good

- Substitute vs Complements

- Price Floor

- Price Ceiling

Substitute goods (or simply substitutes) are products which all satisfy a common want and complementary goods (simply complements) are products which are consumed together. Demand for a product’s substitutes increases and demand for its complements decreases if the product’s price increases.

One of the determinants of demand i.e. factors that can bring about a shift in the demand curve of a product is the price of the related goods. There are two types of related goods in general: good(s) which can be consumed instead of the product and good(s) which is consumed together with the product. The former is called a substitute good and the latter is a complementary good.

Substitute Goods

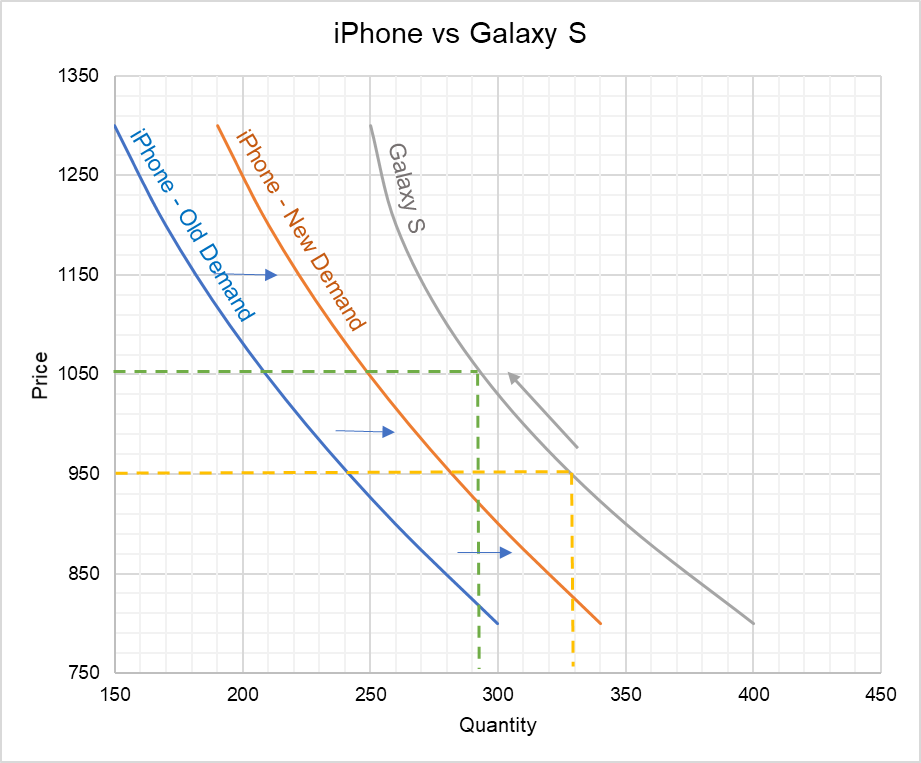

Coke and Pepsi, iPhone and Galaxy S series, Nike and Adidas are a few examples of substitute goods. If price of Coke increases, demand for Pepsi should increase because many Coke consumers will switch over to Pepsi. Similarly, prices of iPhone and Galaxy S affect their mutual demand. Given that there are many fanboys who will reprioritize their spending to afford an iPhone even after the price increase, many rational consumers will weight their preference for one product over the other and the premium they are willing to pay.

Complementary Goods

iPhones and iPhone skins, air travel and hotels, etc. are examples of complementary goods i.e. goods that are used/consumed together. If iPhone becomes expensive and its quantity demanded decreases, you would expend the demand for iPhone covers to drop too and vice versa. It follows that demand for a product is to some extent dependent on the price of its complementary goods.

Other examples of complementary goods include cars and gasoline, Big Mac and McFries, coffee and cheesecake, etc.

Substitutes, Complements and Cross Elasticity of Demand

The extent to which two products are substitutes or complements can be measured by calculating their mutual cross elasticity of demand. The cross elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in quantity demanded of the product that occurs in response a percentage change in price of a substitute good. If the cross elasticity of demand is positive, the products are substitute goods. On the other hand, if cross elasticity is negative, the products are complements.

The following chart shows what happens to demand for two substitute goods, iPhone and Galaxy S, when the price of Galaxy S changes.

When the price of Galaxy S changes from $950 to $1,050, its quantity demanded falls from 330 million per annum to a little more than 290 million. In response, the demand curve for iPhone shifts outward, i.e. its demand increases.

by Obaidullah Jan, ACA, CFA and last modified on Feb 5, 2019

Related Topics

All chapters in economics.

- Market Economy

- Production Functions

- Cost Curves

- Consumption Function

- Market Structure

- Game Theory

- National Income Accounting

- Growth Accounting

- Fiscal Policy

- Monetary Policy

- Inflation Rate

- Structural Unemployment

Current Chapter

XPLAIND.com is a free educational website; of students, by students, and for students. You are welcome to learn a range of topics from accounting, economics, finance and more. We hope you like the work that has been done, and if you have any suggestions, your feedback is highly valuable. Let's connect!

Copyright © 2010-2024 XPLAIND.com

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Complementary Goods, Oligopoly and Bundling: a reassessment of Cournot’s merger effects

In recent years the Antitrust authorities in the U.S. and EU have been addressing the issues involving non-horizontal mergers, which include vertical and conglomerate mergers, including complementary products mergers. The EU commissioned two reports on the economic knowledge about these mergers, totaling over 500 pages. This work has not recognized what we analyze here. Complementary products mergers are guided by the intuition behind Cournot’s complementary monopoly merger analysis. Pre merger there is “double marginalization”; merger leads to lower prices. We show how tenuous this intuition is if applied to oligopolists. We start with Merger Guidelines and three statements from antitrust authorities. We formalize these as theoretical propositions about such mergers. The propositions are: 1) Cournot effects will lower prices; 2) Complementary products mergers will never lead to higher prices (barring specific perverse effects); 3) if these mergers lead to mixed bundling they will be to the consumers’ advantage by offering more choice. These are all positive economics statements about what will happen. We prove these are all theoretically false via counter example. If there is vertical/quality product differentiation, price setting oligopoly and compatible components, the Cournot result disappears in price setting oligopoly modeling even using the Cournot demand structure. Such mergers will not lower prices. We show an alternative demand structure for which such mergers raise prices for all buyers through bundling. And we show a third demand structure in which mixed bundling is the culprit in extracting high prices – the mixed bundling doesn’t so much offer a discount from individual component pricing as it instead endogenously raises the individual component prices, before offering a “discount” for the purchase of a bundle. We do not do a full policy analysis, and our proofs by counter example use stylized demand structures. We emphasize, however, that before attempting a normative policy analysis, the positive economics must be understood. The views expressed herein are the authors’ own and are not purported to reflect those of the employers.

Related Papers

Serdar A . K . A . İ S M A İ L S E R D A R Dalkir , Robert Masson

DESCRIPTION In recent years the Antitrust authorities in the U.S. and EU have been addressing the issues involving non-horizontal mergers, which include vertical and conglomerate mergers, including complementary products mergers. The EU commissioned two reports on the economic knowledge about these mergers, totaling over 500 pages. This work has not recognized what we analyze here. Complementary products mergers are guided by the intuition behind Cournot’s complementary monopoly merger analysis. Pre merger there is “double marginalization”; merger leads to lower prices. We show how tenuous this intuition is if applied to oligopolists. We start with Merger Guidelines and three statements from antitrust authorities. We formalize these as theoretical propositions about such mergers. The propositions are: 1) Cournot effects will lower prices; 2) Complementary products mergers will never lead to higher prices (barring specific perverse effects); 3) if these mergers lead to mixed bundling...

Review of Law & Economics

Antitrust policy in the US and EU toward non-horizontal mergers between oligopolists is based on a strong presumption of Cournot effects and/ or improvements in consumer welfare through post-merger bundling. We show that complementary goods mergers between firms that possess market power in their respective components markets do not always assure either. The analysis underscores the importance of fully specifying the nature of premerger rivalry among all market participants and the assumed distribution of consumer preferences when making predictions about the likely effects of such transactions. https://masson.economics.cornell.edu/docs/rle-2013-0014_2.pdf

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services

Subir Bandyopadhyay

In an attempt to provide a framework that can help firms find optimum bundling product categories and pricing strategies that maximize their profits, this study develops a profit-maximization model. The results indicate that optimum bundles and price strategies exist; specifically, if a firm uses a bundling strategy to sell its products, it should combine highly complementary products and charge a relatively lower price. The value of a bundling strategy always increases with the size of market and price sensitivity. Managers can use the provided model framework and related advice and examples to plan their bundling strategies.

The Journal of Industrial Economics

Nicholas Economides

This article analyzes the competition and integration among complementary products that can be combined to create composite goods or systems. The model generalizes the Cournot duopoly complements model to the case in which there are multiple brands of compatible components. It analyzes equilibrium prices for a variety of organizational and market structures that differ in their degree of competition and integration. The model applies to a variety of product networks including ATMs, real estate MLS, airlines CRS, as well as to non-network markets of compatible components such as computer CPUs and peripherals, hardware and software, and long distance and local telephone services.

Elisa Barocio

The existing literature shows that a decrease in the degree of substitutability increases a monopoly's incentive to bundle. This paper in addition takes into account competition in the second product market and then reexamines how intra-brand and inter-brand product differentiations affect the incentive to bundle. In order to formally examine the above conjectures, this research builds up a two-firm, two-product model in which product 1 (monopoly product) is produced only by the bundling firm and product 2 (competing product) is produced by both firms. The analysis shows that under both Bertrand and Cournot competitions the incentive to bundle does not necessarily increase with the degree of intra-brand differentiation, while it strictly decreases with the degree of inter-brand differentiation. Moreover, under Bertrand competition bundling always decreases consumer surplus, but may increase the competitor's profit and social surplus. Under Cournot competition bundling always reduces the opponent's profit and social welfare, but may increase consumer surplus.

SSRN Electronic Journal

Ornella Tarola

Research in Economics

Poudou Jean-Christophe

We study the incentives to collude when firms use mixed bundling or independent pricing strategies for the sale of two components of a composite good. The main finding is that collusion is less sustainable under mixed bundling, because this increases the profitability of deviations from the collusive path. The result is robust to extensions with an endogenous choice of the mode of competition (with bundling or independent pricing) and to competition in quantities. These results offer a novel argument against a per se rule concerning bundling in antitrust policy. JEL classification: D4, L1

Jeff MacKie-Mason

Volker Nocke

RELATED PAPERS

Mohammad Hussain

Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia

Estela Suzana Horowitz

Abdulnaser Alkhalil

原版复制加拿大菲莎河谷大学毕业证 ufv学位证书双学位证书续费收据原版一模一样

Jose Manuel Hernandez Martin

Md. Latiful Haque

Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP

Sara Falsini

Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems

Gastón Aguilera

Turkish Journal of Hematology

Ahmet Muzaffer Demir

Margarida Póvoa

Philip Schlesinger

International Journal of Design and Fashion Studies

Asmaa Mustafa

Academia Environmental Sciences and Sustainability

Ruth Ogbonmwan

International journal of linguistics, literature and translation

Daniel YOKOSSI

Hernani Azevedo

Jurnal Pendidikan Akuntansi (JPAK)

indrianti er

botol asi kaca jogja

supplier grosirharga

Beatriz Giraldo Ospina

Ricardo de Oliveira

Textos & Contextos (Porto Alegre)

CASSIA BEATRIZ BATISTA

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Accountancy

- Business Studies

- Organisational Behaviour

- Human Resource Management

- Entrepreneurship

- CBSE Class 11 Microeconomics Notes

Chapter 1: Introduction

- Introduction to Microeconomics

- Microeconomics and Macroeconomics: Meaning, Scope, and Interdependence

- Difference between Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

- Economic Problem & Its Causes

- Central Problems of an Economy

- Opportunity Cost : Definition, Types, Formula & Examples

- Production Possibilities Curve (PPC) : Meaning, Assumptions, Properties and Example

Chapter 2: Consumer's Equilibrium

- Theory of Consumer Behaviour

- Difference between Needs and Wants

- Utility Analysis : Total Utility and Marginal Utility

- Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility (DMU) : Meaning, Assumptions & Example

- Consumer's Equilibrium in case of Single and Two Commodity

- Indifference Curve : Meaning, Assumptions & Properties

- Budget Line: Meaning, Properties, and Example

- Difference between Budget Line and Budget Set

- Shift in Budget Line

- Consumer’s Equilibrium by Indifference Curve Analysis

Chapter 3: Demand

- Theory and Determinants of Demand

- Individual and Market Demand

- Difference between Individual Demand and Market Demand

- What is Demand Function and Demand Schedule?

- Law of Demand

- Movement along Demand Curve and Shift in Demand Curve

- Difference between Expansion in Demand and Increase in Demand

- Difference between Contraction in Demand and Decrease in Demand

Substitute Goods and Complementary Goods

Difference between substitute goods and complementary goods.

- Normal Goods and Inferior Goods

- Difference between Normal Goods and Inferior Goods

- Types of Demand

- Substitution and Income Effect

- Difference between Substitution Effect and Income Effect

- Difference between Normal Goods, Inferior Goods, and Giffen Goods

Chapter 4: Elasticity of Demand

- Price Elasticity of Demand: Meaning, Types, Calculation and Factors Affecting Price Elasticity

- Methods of Measuring Price Elasticity of Demand: Percentage and Geometric Method

- Difference between Elastic and Inelastic Demand

- Relationship between Price Elasticity of Demand and Total Expenditure

Chapter 5: Production Function: Returns to a Factor

- Production Function: Meaning, Features, and Types

- What is TP, AP and MP? Explain with examples.

- Law of Variable Proportion: Meaning, Assumptions, Phases and Reasons for Variable Proportions

- Relationship between TP, MP, and AP

- Law of Returns to Scale: Meaning and Stages

- Difference between Returns to Factor and Returns to Scale

Chapter 6: Concepts of Cost and Revenue

- What is Cost Function?

- Difference between Explicit Cost and Implicit Cost

- Types of Cost

- What is Total Cost ? | Formula, Example and Graph

- What is Average Cost ? | Formula, Example and Graph

- What is Marginal Cost ? | Formula, Example and Graph

- Variable Cost: Meaning, Formula, Types and Importance

- Interrelation between Costs

- Concepts of Revenue| Total Revenue, Average Revenue and Marginal Revenue

- Relationship between Revenues (AR, MR and TR)

- Break-even Analysis: Importance, Uses, Components and Calculation

- What is Break-even Point and Shut-down Point?

Chapter 7: Producer’s Equilibrium

- Producer's Equilibrium: Meaning, Assumptions, and Determination

Chapter 8: Theory of Supply

- Theory of Supply: Characteristics and Determinants of Individual and Market Supply

- Difference between Stock and Supply

- Law of Supply: Meaning, Assumptions, Reason and Exceptions

- Changes in Quantity Supplied and Change in Supply

- Difference between Movement Along Supple Curve and Shift in Supply Curve

- Difference between Change in Quantity Supplied and Change in Supply

- Difference Between Expansion of Supply and Increase in Supply

- Difference between Contraction of Supply and Decrease in Supply

- Price Elasticity of Supply : Type, Determinants and Methods

- Types of Elasticity of Supply

Chapter 9: Forms of Market

- Market : Characteristics & Classification

- Perfect Competition Market: Meaning, Features and Revenue Curves

- Monopoly Market: Features, Revenue Curves and Causes of Emergence

- Monopolistic Competition: Characteristics & Demand Curve

- Oligopoly Market : Types and Features

- Difference between Perfect Competition and Monopoly

- Difference between Perfect Competition and Monopolistic Competition

- Difference between Monopoly and Monopolistic Competition

- Distinction between the four Forms of Market(Perfect Competition, Monopoly, Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly)

- Long-Run Equilibrium under Perfect, Monopolistic, and Monopoly Market

- Profit Maximization : Meaning, Elements, Conditions and Formula

- Profit Maximization in Perfect Competition Market

- Profit Maximization in Monopoly Market

Chapter 10: Market Equilibrium under Perfect Competition

- Determination of Market Equilibrium under Perfect Competition

- Effects of Changes in Demand and Supply on Market Equilibrium

- Price Ceiling and Price Floor or Minimum Support Price (MSP): Simple Applications of Supply and Demand

- Difference between Price Ceiling and Price Floor

- Important Formulas in Microeconomics | Class 11

Substitute Goods and Complementary Goods are two economic concepts describing the relationship between two or more different products in terms of their demand and consumption patterns. Substitute goods are the goods that can be used in place of one another; however, Complementary goods are the goods that can be used together. It is essential to understand the relationship between substitute goods and complementary goods, especially for organisations and policymakers. It is so because the relationship between these goods helps businesses and policymakers in predicting consumer behaviour, setting prices, and developing marketing strategies.

Geeky Takeaways:

- Substitute Goods are those goods which are used in place of one another to fulfill a specific need or want. For example, Coke and Coca-Cola.

- Complementary Goods are those goods which are used together to fulfill a specific need or want. For example, TV and remote.

- Cross Demand helps in determining the demand of a given commodity when the price of other related commodities changes.

- A commodity’s demand is only affected by a change in the price of related goods and not the price of unrelated goods.

Table of Content

What are Substitute Goods?

What are complementary goods, what is cross demand, cross price effect on demand curve.

The goods which can be used in place of one another to satisfy a specific want, like tea and coffee are known as Substitute Goods. The price of substitute goods directly affects the demand for a given commodity.

For example, if the price of a substitute good (say, coffee) increases, then demand for the given commodity (say, tea) will increase as compared to coffee.

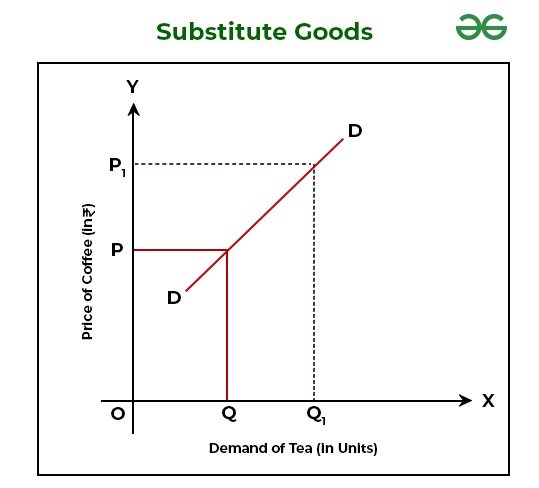

In the above graph, the price of the substitute good (coffee) is shown on the Y-axis, and demand for the given commodity (tea) is shown on X-axis. When there is an increase in the price of coffee from OP to OP 1 , then the demand for tea will also increase from OQ to OQ 1 .

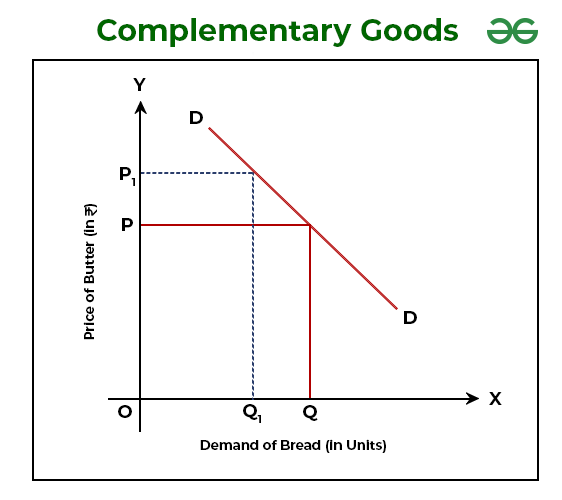

The goods which are used together to satisfy a specific want, like bread and butter are known as Complementary Goods. The price of a complementary good and demand for the given commodity inversely relates to each other.

For example, if the price of a complementary good (say, butter) increases, then demand for the given commodity (say, bread) will decrease as it will become costlier for the consumer to use both goods together.

In the above graph, the price of the complementary good (butter) is shown on the Y-axis and demand for the given commodity (bread) is shown on X-axis. When there is an increase in the price of butter from OP to OP 1 , then the demand for bread will also increase from OQ to OQ 1 .

Note: The above shown graphs are not demand curves. They only show the relationship between demand for a given commodity and price of the related good.

Demand is not affected by Change in Price of Unrelated Goods A commodity’s demand is only affected by a change in the price of related goods (substitute goods and complementary goods). If there is a change in the price of unrelated goods, then there is no impact on the demand for a given commodity. Unrelated goods are the goods which are not linked with the demand for a given commodity. For example, if there is an increase/decrease in the price of bottle, then there will be no impact on the demand for laptop.

By keeping other things constant, the relationship between the demand for a given commodity and the price of related commodities is known as Cross Demand. In simple terms, cross demand helps in knowing how much quantity of a given commodity will be demanded at different price levels of a related commodity (substitute good or complementary good). Cross Demand can be expressed as:

D x = f(P y )

D x = Demand for the given commodity

f = Functional Relationship

P y = Price of the related commodity (substitute or complementary)

Cross Demand can be either Positive or Negative

- In the case of substitute goods, cross demand is positive. It is because the demand for a given commodity varies directly with the prices of substitute goods.

- In the case of complementary goods, cross demand is negative. It is because the demand for a given commodity varies inversely with the prices of complementary goods.

The effect on the demand for a given commodity because of a change in the price of a related commodity is known as Cross Price Effect. In simple terms, the cross price effect originates from substitute goods and complementary goods. The effect of change in the prices of substitute goods and complementary goods can be explained as follows:

A. Change in Price of Substitute Goods

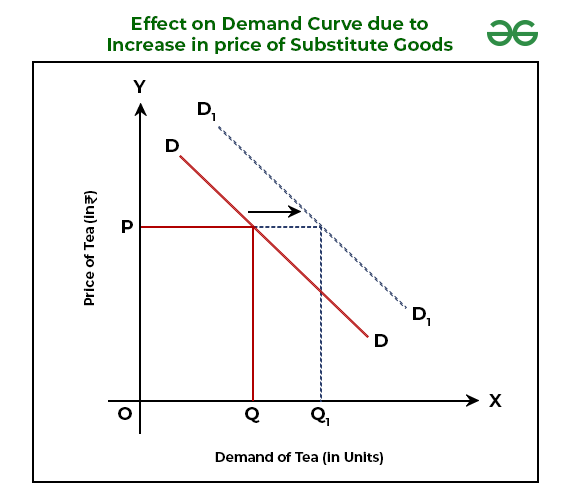

An increase or decrease in the price of substitute goods has a direct impact on the demand for a given commodity.

1. Increase in Price of Substitute Goods: When there is an increase in the price of substitute goods (say, coffee), the demand for the given commodity (say, tea) will also increase from OQ to OQ 1, with the same price OP. It results in a rightward shift in the demand curve of the given commodity (tea) from DD to D 1 D 1 .

2. Decrease in Price of Substitute Goods: When there is a decrease in the price of substitute goods (say, coffee), the demand for the given commodity (say, tea) will also decrease from OQ to OQ 1, with the same price OP. It results in a leftward shift in the demand curve of the given commodity (tea) from DD to D 1 D 1 .

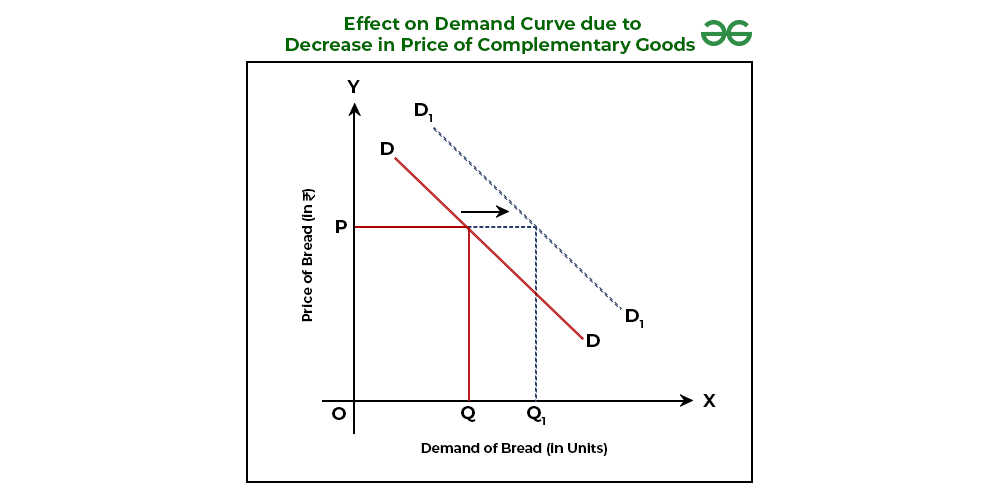

B. Change in Price of Complementary Goods

An increase or decrease in the price of complementary goods has an inverse impact on the demand for a given commodity.

1. Increase in Price of Complementary Goods: When there is an increase in the price of complementary goods (say, butter), the demand for the given commodity (say, bread) will decrease from OQ to OQ 1, with the same price OP. It results in a leftward shift in the demand curve of the given commodity (bread) from DD to D 1 D 1 .

2. Decrease in Price of Complementary Goods: When there is a decrease in the price of complementary goods (say, butter), the demand for the given commodity (say, bread) will increase from OQ to OQ 1, with the same price OP. It results in a rightward shift in the demand curve of the given commodity (bread) from DD to D 1 D 1 .

Please Login to comment...

Similar reads.

- Commerce - 11th

- Microeconomics

Improve your Coding Skills with Practice

What kind of Experience do you want to share?

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- July–August 2013

- Marketing Science

Complementary Goods: Creating, Capturing, and Competing for Value

- Format: Print

- | Pages: 16

- Find it at Harvard

About The Author

More from the Authors

- Faculty Research

21Seeds: Taking Shots at Breakout Growth

Joy4home brands: pricing matters.

- March 2024 (Revised March 2024)

Amperity: First-Party Data at a Crossroads

- 21Seeds: Taking Shots at Breakout Growth By: Julian De Freitas and Elie Ofek

- Joy4Home Brands: Pricing Matters By: Elie Ofek

- Amperity: First-Party Data at a Crossroads By: Elie Ofek, Hema Yoganarasimhan and Alexis Lefort

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Currently reading: Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG

- Business school teaching case study: can green hydrogen’s potential be realised?

- Business school teaching case study: how electric vehicles pose tricky trade dilemmas

- Business school teaching case study: is private equity responsible for child labour violations?

Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on x (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on facebook (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Gabriela Salinas and Jeeva Somasundaram

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In April this year, Hein Schumacher, chief executive of Unilever, announced that the company was entering a “new era for sustainability leadership”, and signalled a shift from the central priority promoted under his predecessor , Alan Jope.

While Jope saw lack of social purpose or environmental sustainability as the way to prune brands from the portfolio, Schumacher has adopted a more balanced approach between purpose and profit. He stresses that Unilever should deliver on both sustainability commitments and financial goals. This approach, which we dub “realistic sustainability”, aims to balance long- and short-term environmental goals, ambition, and delivery.

As a result, Unilever’s refreshed sustainability agenda focuses harder on fewer commitments that the company says remain “very stretching”. In practice, this entails extending deadlines for taking action as well as reducing the scale of its targets for environmental, social and governance measures.

Such backpedalling is becoming widespread — with many companies retracting their commitments to climate targets , for example. According to FactSet, a US financial data and software provider, the number of US companies in the S&P 500 index mentioning “ESG” on their earnings calls has declined sharply : from a peak of 155 in the fourth quarter 2021 to just 29 two years later. This trend towards playing down a company’s ESG efforts, from fear of greater scrutiny or of accusations of empty claims, even has a name: “greenhushing”.

Test yourself

This is the fourth in a series of monthly business school-style teaching case studies devoted to the responsible business dilemmas faced by organisations. Read the piece and FT articles suggested at the end before considering the questions raised.

About the authors: Gabriela Salinas is an adjunct professor of marketing at IE University; Jeeva Somasundaram is an assistant professor of decision sciences in operations and technology at IE University.