What Is the Health Belief Model? An Updated Look

Despite this fact, participation in screening tends to be low. In Australia, only 40% of adults opted for screening for bowel cancer in 2021 — 3% lower than the previous year (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023).

Why do people decide not to participate in a low-risk activity like screening? Or visit the dentist regularly, or quit smoking? Why do we choose to ignore these necessary health steps?

Why and how people view the risks of disease, and the subsequent likelihood of people adjusting their behaviors, can be better understood with the health belief model.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains

A brief history of the health belief model, primary components of the health belief model theory, 3+ health belief model application examples, updates and modifications to the hbm, criticisms of the hbm, 6 worksheets and interventions, a take-home message.

Researchers knew that socioeconomic, sociocultural, and demographic factors, such as age, gender, ethnicity, and race, influenced the likelihood that people could afford health care and would seek it out (Abraham & Sheeran, 2015). However, what researchers observed in the 1950s surprised them.

In the 1950s, screening for tuberculosis was made easier and more accessible with mobile X-ray vans, removing the need for patients to make costly and time-consuming trips to hospitals and clinics. What social psychologists Hochbaum, Rosenstock, and Kegels observed was surprising: Despite the increased accessibility and convenience, there was meager participation (Daniati et al., 2021; Skinner et al., 2015). Why would this be?

These researchers posited that patients’ beliefs, attitudes, and understanding of the illness and health care greatly influenced the likelihood that they would seek preventive treatments and screening (Janz & Becker, 1984). This hypothesis resulted in the health belief model (HBM).

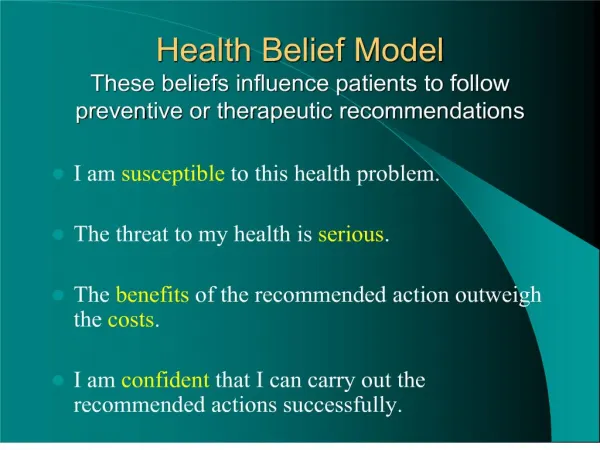

The HBM consisted of the following five concepts:

- Perceived susceptibility describes the individual’s belief about the likelihood of getting a particular health condition.

- Perceived severity refers to the individual’s belief about the seriousness of the health condition and its consequences.

- Perceived benefits describe the belief in the effectiveness of taking action to reduce risk or seriousness of the health condition.

- Perceived barriers refer to the perceived obstacles or costs associated with taking action to reduce the risk or seriousness of a health condition.

- Cues to action are triggers that prompt individuals to take action, such as symptoms, media campaigns, or recommendations from health care providers.

The health belief model was later modified to include additional factors. These are self-efficacy, our belief in our ability to take action, and the importance of socio-demographic factors.

Here is a short video that uses a simple example to explain the HBM.

Although the original use case of the HBM was to explain low participation in preventive screening programs for diseases, it has since been applied to other scenarios. These include smoking cessation treatments, vaccination programs, and treatment adherence.

These components explain how individuals gauge the threat of behaviors and illnesses and interpret and value the efficacy of treatment, ultimately shaping their decision to adopt health-promoting behaviors (Abraham & Sheeran, 2015).

We will go through each component in more detail below.

1. Perceived susceptibility

Perceived susceptibility refers to how an individual’s belief in their vulnerability to a specific disease can lead to preventive actions and behaviors. For example, people who believe they are at severe risk of contracting the flu are more likely to opt for a flu vaccine.

2. Perceived severity

People are more likely to engage in behaviors to mitigate health issues when they perceive a health issue as serious and think that it might impact their lives. This is known as perceived severity . For example, knowing the risks of smoking-related diseases can encourage quitting.

3. Perceived benefits

Perceived benefits describe how individuals are also more likely to engage in certain behaviors if they positively perceive the benefits of those behaviors. For example, people who perceive the benefits of regular exercise positively are more likely to exercise than people who undervalue or do not recognize the benefits of exercise.

4. Perceived barriers

Perceived barriers refer to the severity and difficulty of obstacles/barriers that can significantly impact whether individuals are likely to adopt certain behaviors. If people have to overcome many obstacles to achieve a particular goal, they are less likely to adopt and maintain the behavior.

These obstacles can be practical, psychological, or social and can include cost, inconvenience, fear, or a lack of social support. More examples of barriers include the cost of a gym membership, clinic location, the psychological effort to complete a task, or the time needed to exercise.

5. Cues to action

The fifth component, cues to action , prompts individuals to take action regarding their health. These cues can be internal, such as personal experiences, or external, such as advice from health care providers.

These cues influence health-related decision-making and actions by closing the gap between awareness of health risks and the initiation of appropriate health behaviors. For example, people know when to seek out a health care professional if they can identify symptoms of certain illnesses.

6. Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the sixth component added to later adaptations of the health belief model. Self-efficacy is our belief in our ability to perform healthy behaviors successfully. Higher levels of self-efficacy are associated with greater motivation and persistence in adopting and maintaining health-promoting behaviors.

Examples of self-efficacy are trusting in our ability to succeed and recognizing that we have the skill set and knowledge to overcome challenges.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

The health belief model can be applied to several health-related contexts to explain behavior and participation (Abraham & Sheeran, 2015).

Some examples include:

- Programs that tackle preventive behaviors, such as screening, risk behaviors, vaccinations, and contraceptive behaviors

- Adherence programs for the treatment of various illnesses

- Clinic visits

We will briefly look at a few of these applications in more detail.

Smoking cessation programs

To measure knowledge and perception of health behaviors related to smoking cessation, health educators and practitioners used questionnaires measuring various components of the HBM (Renuka & Pushpanjali, 2014). The aim of the study was to determine whether attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge of tobacco use could change through health care education.

This study was specifically conducted in dental care settings due to the relationship between tobacco use and dental health. Tobacco use is correlated with various dental illnesses and conditions, including dental cancer and cleft lip and palate (Renuka & Pushpanjali, 2014).

Results of the study showed that health behavior and knowledge around tobacco and smoking behaviors improved overall. Dental behavior also significantly improved, but only for younger participants, participants who smoked tobacco products (as opposed to vaping), and individuals who already visited the dentist at least once per year. So improvement in these three domains reduces the risk of oral diseases associated with smoking.

Cancer screening campaigns

Research has shown that incorporating HBM components into cancer screening campaigns is compelling and informative. For example, Luquis and Kensinger (2019) found that two components of the health belief model — perceived susceptibility and perceived seriousness — significantly predicted whether younger adults were likely to regularly screen for various cancers.

Vaccination campaigns

Previous studies have found a significant correlation between several components of the HBM and vaccination hesitancy. A systematic review of 16 studies with over 30,000 participants found that vaccine hesitancy was linked to perceived barriers in a positive way (Limbu et al., 2022).

On the other hand, vaccine hesitancy was linked to perceived benefits, perceived susceptibility, cues to action, perceived severity, and self-efficacy in a negative way (Limbu et al., 2022). These results confirm previous findings in the literature (e.g., Mercadante & Law, 2021).

With this insight, health authorities and organizations can use the HBM to encourage vaccination uptake by addressing:

- Individuals’ perceptions of susceptibility to vaccine-preventable diseases

- The severity of those diseases

- The benefits of vaccination for personal and community health

- Strategies to overcome vaccine-related barriers, such as vaccine hesitancy and misinformation

Other areas where the health belief model has been successfully applied include:

- Diabetes (Gillibrand & Stevenson, 2006; Sharifirad et al., 2006)

- Exercise (King et al., 2013)

Interestingly, applying the HBM outside the medical domain has had less success. For example, research suggests that the HBM has limited predictive value in explaining and improving seat belt usage (Şimşekoğlu & Lajunen, 2008; Tavafian et al., 2011).

These examples illustrate how the health belief model can inform the development and implementation of health promotion initiatives across various health issues.

Some of these updates and modifications include the following.

Inclusion of additional constructs

One significant modification involves the inclusion of additional constructs beyond the original components of the HBM. For example, self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to perform a specific behavior successfully, was incorporated into the model following research by King (1982, as cited in Abraham & Sheeran, 2015).

King argued that self-efficacy was an excellent predictor of patients attending hypertension screening (King, 1982, as cited in Abraham & Sheeran, 2015). Over time, this concept merged with research into locus of control and perceived control and became known as self-efficacy.

Integration with social cognitive theory

The efficacy of the health belief model is improved when used alongside other theories. One such example is the social cognitive theory (SCT).

Social cognitive theory emphasizes the role of observational learning, social influence, and self-regulation in shaping health behaviors (Abraham & Sheeran, 2015).

Integrating SCT with the HBM provides a more comprehensive understanding of how individuals’ beliefs, social environment, and self-efficacy influence health-related decisions and actions.

Incorporation of technology

With the advancement of technology, researchers and practitioners have explored the use of digital platforms, mobile apps, and online interventions to apply the principles of the health belief model in promoting health behaviors.

These technology-based interventions leverage interactive features, personalized feedback, and social support to enhance individuals’ motivation, self-efficacy, and engagement in health-promoting activities (Kim & Park, 2012).

Additionally, when paired with the technology acceptance model to measure the perceived usefulness of the internet for health information and attitudes toward internet use for health purposes, the positive effects of the HBM are amplified and the model is strengthened (Ahadzadeh et al., 2015).

Overall, the updates and modifications to the health belief model reflect efforts to enhance its theoretical robustness, practical utility, and cultural relevance in promoting health behavior change across diverse populations and settings.

Initial criticism of the model focused on the poorly defined constructs underpinning the HBM and its poor predictive statistical power (Armitage & Conner, 2000).

Although changes have been made, not all researchers and authors agree about the improvements and modifications made to the health belief model.

Some of the controversies associated with the improvements and modifications include theoretical disagreements about the underlying constructs that compose the model. Also, there is substantial overlap between models explaining health behavior, such as the health belief model and another theory, protection motivation theory (Abraham & Sheeran, 2015).

Other criticisms include the fact that the HBM largely ignores structural barriers. For example, changing attitudes and beliefs about health care does little to combat the cost of health care treatment (Wong et al., 2020).

Despite these controversies and challenges, the health belief model remains a valuable framework for understanding and promoting health behavior change.

Researchers continue to explore its applications, refine its constructs, and evaluate its effectiveness in diverse contexts. The debates surrounding the HBM contribute to ongoing discussions within health psychology and public health, fostering critical reflection and innovation in theory and practice.

Health belief model scale

Various HBM scales exist, and the difference between them is their application, because the scales measure beliefs and attitudes around a disease, behavior, treatment, or intervention of interest.

For practitioners interested in using questions from a health belief model scale to measure clients’ attitudes toward a particular treatment or behavior, they will need to adapt existing tools and interventions to incorporate the model’s principles.

- To measure attitudes toward exercise, readers can refer to Wu et al. (2020). They developed an 18-item scale with good psychometric properties. For questions around other behaviors, such as lifestyle or prevention, readers can refer to Şimşekoğlu and Lajunen (2008).

- To measure HBM constructs around self-examination, see Abraham and Sheeran (2015).

- For readers who are interested in focusing on only one component of the HBM and want to know how to adapt or target those aspects, see Orji et al. (2012). They have a useful table detailing various interventions that can be applied for each submeasure.

Health belief assessment worksheet

The Technical Assistance Network for Children’s Behavioral Health released an extensive toolkit that measures various beliefs around healthcare (Concha et al., 2014).

This 33-item questionnaire was designed to measure questions around health care relating to community, spiritual care, family, knowledge of illness, perceptions of health care practitioners, service delivery, and community.

It is quite extensive and can guide practitioners in uncovering any beliefs or attitudes that might be preventing a client from seeking or persisting in their health care journey. The worksheet is available at the University of Florida website .

SMART goals

To help clients meet their goals, practitioners can guide clients through a goal-setting exercise based on the principles of the health belief model. For example, encourage them to set specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals related to improving their health behaviors.

In this exercise, practitioners can help clients identify strategies to address perceived barriers and enhance the perceived benefits of adopting healthier habits .

Here are two worksheets to help you.

- The first worksheet helps you and your client identify the important questions needed to achieve their goals.

- The second worksheet is a condensed version of the first and can be used to track multiple goals. The second worksheet is useful once your client understands the SMART process.

Decisional balance worksheet

When helping clients make a decision about their health behaviors, practitioners can use a decisional balance worksheet to help clients weigh the pros and cons.

Ask clients to list the advantages and disadvantages of adopting healthier behaviors, considering factors such as perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and the potential outcomes of their actions. This list will help clients gain insight into their own beliefs, make informed decisions, and prioritize goals.

In this decision-making worksheet , clients are asked to list the different options available to them and list the pros and cons associated with each.

If you want to help your client evaluate their past decisions so that they can identify which decisions were good and bad, then the Behavior Self-Evaluation worksheet will help you. Clients are asked to identify previous decisions, evaluate the outcome, and decide whether they would change their decision and why.

By integrating these worksheets and interventions into coaching or counseling sessions, practitioners can effectively apply the principles of the health belief model to support clients in achieving their health and wellness goals. Practitioners will need to adapt existing tools, questions, and worksheets to individual clients to ensure its appropriateness.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

The health belief model is a useful framework for making sense of why we choose whether to participate in certain health behaviors.

With this framework, practitioners can isolate and explore different aspects of clients’ decision-making processes, help clients gain insight into their behavior, and identify the challenges they experience with implementing positive change.

Although the health belief model is not applicable to every situation, it can still be leveraged to gain insight. Remember that change will not be immediate. Help manage your clients’ expectations; small changes are not always visible, but they add up over time.

Before you go, make sure to read these posts about changing behavior in your clients.

- What Is Behavior Change in Psychology? 5 Models and Theories

- How to Change Self-Limiting Beliefs According to Psychology

Let us know in the comments if this post helped you gain insight into your own behavior or that of your clients.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Abraham, C., & Sheeran, P. (2015). The health belief model. Predicting health behavior: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models , 2 , 30–55.

- Ahadzadeh, A. S., Sharif, S. P., Ong, F. S., & Khong, K. W. (2015). Integrating health belief model and technology acceptance model: An investigation of health-related internet use. Journal of Medical Internet Research , 17 (2).

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2000). Social cognition models and health behaviour: A structured review. Psychology & Health , 15 (2), 173–189.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023, December 1). Cancer screening . Retrieved April 8, 2024, from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/cancer-screening-and-treatment

- Concha, M., Villar, M. E., & Azevedo, L. (2014). Health attitudes and beliefs tool kit. Technical Assistance Network for Children’s Behavioral Health . University of Maryland, Baltimore.

- Daniati, N., Widjaja, G., Olalla Gracìa, M., Chaudhary, P., Nader Shalaby, M., Chupradit, S., & Fakri Mustafa, Y. (2021). The health belief model’s application in the development of health behaviors. Health Education and Health Promotion , 9 (5), 521–527.

- Gillibrand, R., & Stevenson, J. (2006). The extended health belief model applied to the experience of diabetes in young people. British Journal of Health Psychology , 11 (1), 155–169.

- Janz, N. K., & Becker, M. H. (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly , 11 (1), 1–47.

- Kim, J., & Park, H. A. (2012). Development of a health information technology acceptance model using consumers’ health behavior intention. Journal of Medical Internet Research , 14 (5).

- King, K. A., Vidourek, R. A., English, L., & Merianos, A. L. (2013). Vigorous physical activity among college students: Using the health belief model to assess involvement and social support. Archives of Exercise in Health and Disease , 4 (2), 267–279.

- Limbu, Y. B., Gautam, R. K., & Pham, L. (2022). The health belief model applied to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A systematic review. Vaccines , 10 (6).

- Luquis, R. R., & Kensinger, W. S. (2019). Applying the health belief model to assess prevention services among young adults. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education , 57 (1), 37–47.

- Mercadante, A. R., & Law, A. V. (2021). Will they, or won’t they? Examining patients’ vaccine intention for flu and COVID-19 using the health belief model. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy , 17 (9), 1596–1605.

- Orji, R., Vassileva, J., & Mandryk, R. (2012). Towards an effective health interventions design: An extension of the health belief model. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics , 4 (3).

- Renuka, P., & Pushpanjali, K. (2014). Effectiveness of health belief model in motivating for tobacco cessation and to improving knowledge, attitude and behavior of tobacco users. Cancer and Oncology Research , 2 (4), 43–50.

- Sharifirad, G., Entezari, M. H., Kamran, A., & Azadbakht, L. (2009). The effectiveness of nutritional education on the knowledge of diabetic patients using the health belief model. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences , 14 (1).

- Şimşekoğlu, Ö., & Lajunen, T. (2008). Social psychology of seat belt use: A comparison of theory of planned behavior and health belief model. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour , 11 (3), 181–191.

- Skinner, C. S., Tiro, J., & Champion, V. L. (2015). Background on the health belief model. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice , 75 , 1–34.

- Tavafian, S. S., Aghamolaei, T., Gregory, D., & Madani, A. (2011). Prediction of seat belt use among Iranian automobile drivers: Application of the theory of planned behavior and the health belief model. Traffic Injury Prevention , 12 (1), 48–53.

- Wong, L. P., Alias, H., Wong, P. F., Lee, H. Y., & AbuBakar, S. (2020). The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics , 16 (9), 2204–2214.

- Wu, S., Feng, X., & Sun, X. (2020). Development and evaluation of the health belief model scale for exercise. International Journal of Nursing Sciences , 7 , S23–S30.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Circadian Rhythm: The Science Behind Your Internal Clock

Circadian rhythms are the daily cycles of our bodily processes, such as sleep, appetite, and alertness. In a sense, we all know about them because [...]

Positive Pain Management: How to Better Manage Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is a condition that causes widespread, constant pain and distress and fills both sufferers and the healthcare professionals who treat them with dread. [...]

18 Effective Thought-Stopping Techniques (& 10 PDFs)

From time to time, we all experience intrusive, unwanted thoughts in our stream of consciousness (Shackelford & Zeigler-Hill, 2020). While many are frivolous, such as [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Behavioral Change Models

- 1

- | 2

- | 3

- | 4

- | 5

- | 6

- | 7

The Health Belief Model

Limitations of health belief model.

All Modules

The Health Belief Model (HBM) was developed in the early 1950s by social scientists at the U.S. Public Health Service in order to understand the failure of people to adopt disease prevention strategies or screening tests for the early detection of disease. Later uses of HBM were for patients' responses to symptoms and compliance with medical treatments. The HBM suggests that a person's belief in a personal threat of an illness or disease together with a person's belief in the effectiveness of the recommended health behavior or action will predict the likelihood the person will adopt the behavior.

The HBM derives from psychological and behavioral theory with the foundation that the two components of health-related behavior are 1) the desire to avoid illness, or conversely get well if already ill; and, 2) the belief that a specific health action will prevent, or cure, illness. Ultimately, an individual's course of action often depends on the person's perceptions of the benefits and barriers related to health behavior. There are six constructs of the HBM. The first four constructs were developed as the original tenets of the HBM. The last two were added as research about the HBM evolved.

- Perceived susceptibility - This refers to a person's subjective perception of the risk of acquiring an illness or disease. There is wide variation in a person's feelings of personal vulnerability to an illness or disease.

- Perceived severity - This refers to a person's feelings on the seriousness of contracting an illness or disease (or leaving the illness or disease untreated). There is wide variation in a person's feelings of severity, and often a person considers the medical consequences (e.g., death, disability) and social consequences (e.g., family life, social relationships) when evaluating the severity.

- Perceived benefits - This refers to a person's perception of the effectiveness of various actions available to reduce the threat of illness or disease (or to cure illness or disease). The course of action a person takes in preventing (or curing) illness or disease relies on consideration and evaluation of both perceived susceptibility and perceived benefit, such that the person would accept the recommended health action if it was perceived as beneficial.

- Perceived barriers - This refers to a person's feelings on the obstacles to performing a recommended health action. There is wide variation in a person's feelings of barriers, or impediments, which lead to a cost/benefit analysis. The person weighs the effectiveness of the actions against the perceptions that it may be expensive, dangerous (e.g., side effects), unpleasant (e.g., painful), time-consuming, or inconvenient.

- Cue to action - This is the stimulus needed to trigger the decision-making process to accept a recommended health action. These cues can be internal (e.g., chest pains, wheezing, etc.) or external (e.g., advice from others, illness of family member, newspaper article, etc.).

- Self-efficacy - This refers to the level of a person's confidence in his or her ability to successfully perform a behavior. This construct was added to the model most recently in mid-1980. Self-efficacy is a construct in many behavioral theories as it directly relates to whether a person performs the desired behavior.

There are several limitations of the HBM which limit its utility in public health. Limitations of the model include the following:

- It does not account for a person's attitudes, beliefs, or other individual determinants that dictate a person's acceptance of a health behavior.

- It does not take into account behaviors that are habitual and thus may inform the decision-making process to accept a recommended action (e.g., smoking).

- It does not take into account behaviors that are performed for non-health related reasons such as social acceptability.

- It does not account for environmental or economic factors that may prohibit or promote the recommended action.

- It assumes that everyone has access to equal amounts of information on the illness or disease.

- It assumes that cues to action are widely prevalent in encouraging people to act and that "health" actions are the main goal in the decision-making process.

The HBM is more descriptive than explanatory, and does not suggest a strategy for changing health-related actions. In preventive health behaviors, early studies showed that perceived susceptibility, benefits, and barriers were consistently associated with the desired health behavior; perceived severity was less often associated with the desired health behavior. The individual constructs are useful, depending on the health outcome of interest, but for the most effective use of the model it should be integrated with other models that account for the environmental context and suggest strategies for change.

return to top | previous page | next page

Content ©2022. All Rights Reserved. Date last modified: November 3, 2022. Boston University School of Public Health

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How the Health Belief Model Influences Your Behaviors

Elizabeth Boskey, PhD, MPH, CHES, is a social worker, adjunct lecturer, and expert writer in the field of sexually transmitted diseases.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ElizabethBoskeyPhD_660-3602bb6a2edd4f12b085b78ff49f3dc6.jpg)

Carly Snyder, MD is a reproductive and perinatal psychiatrist who combines traditional psychiatry with integrative medicine-based treatments.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/carly-935717a415724b9b9c849c26fd0450ea.jpg)

Blend Images - Jose Luis Pelaez Inc / Brand X Pictures / Getty Images

- Effectiveness

The Takeaway

Frequently asked questions, what is the health belief model.

Scientists use the health belief model (HBM) to try to predict health behaviors. Originally developed in the 1950s and proposed by social psychologists Godfrey Hochbaum, Irwin Rosenstock, and Rosenstock and Kirscht , the health belief model is based on the theory that the willingness to change health behaviors primarily comes from health perceptions.

According to the health belief model, your beliefs about health and health conditions play a role in determining your health-related behaviors. Key factors that affect your approach to health include:

- Barriers you think might be standing in your way

- Exposure to information that prompts you to take action

- Perceived benefit of engaging in healthy behaviors

- Perceived susceptibility to illness

- Perceived consequences of sickness

- Confidence in your ability to succeed

Health experts often look for ways that health belief models affect people's actions, particularly as they relate to individual and public health.

This article discusses how the health belief model works, the different components of the model, and how this approach can be used to address health-related behaviors.

Components of the Health Belief Model

There are six main components of the health belief model. Four of these constructs were main tenets of the theory when it was first developed. Two were added in response to research on the model related to addiction.

Perceived Severity

The probability that a person will change their health behaviors to avoid a consequence depends on how serious they believe the consequences will be. For example:

- If you are young and in love, you are unlikely to avoid kissing your sweetheart on the mouth just because they have the sniffles and you might get their cold. On the other hand, you probably would stop kissing if it might give you a more serious illness.

- Similarly, people are less likely to consider condoms when they think STDs are a minor inconvenience. That's why receptiveness to messages about safe sex increased during the AIDS epidemic. The perceived severity increased enormously.

The severity of an illness can have a major impact on health outcomes. However, a number of studies have shown that perceived risk of severity is actually the least powerful predictor of whether or not people will engage in preventive health behaviors.

Perceived Susceptibility

People will not change their health behaviors unless they believe that they are at risk. For example:

- Individuals who do not think they will get the flu are less likely to get a yearly flu shot.

- People who think they are unlikely to get skin cancer are less likely to wear sunscreen or limit sun exposure.

- Those who do not think that they are at risk of acquiring HIV from unprotected intercourse are less likely to use a condom.

- Young people who don't think they're at risk of lung cancer are less likely to stop smoking.

Research suggests that perceived susceptibility to illness is an important predictor of preventive health behaviors.

Perceived Benefits

It's difficult to convince people to change a behavior if there isn't something in it for them. People don't want to give up something they enjoy if they don't also get something in return. For example:

- A person probably won't stop smoking if they don't think that doing so will improve their life in some way.

- A couple might not choose to practice safe sex if they don't see how it could make their sex life better.

- People might not get vaccinated if they do not think there is an individual benefit for them.

These perceived benefits are often linked to other factors, including the perceived effectiveness of a behavior. If you believe that getting regular exercise and eating a healthy diet can prevent heart disease, that belief increases the perceived benefits of those behaviors.

Perceived Barriers

One of the major reasons people don't change their health behaviors is that they think doing so is going to be hard. Changing health behaviors can require effort, money, and time. Commonly perceived barriers include:

- Amount of effort needed

- Inconvenience

- Social consequences

Sometimes it's not just a matter of physical difficulty, but social difficulty as well. For example, If everyone from your office goes out drinking on Fridays, it may be very difficult to cut down on your alcohol intake. If you think that condoms are a sign of distrust in a relationship, you may be hesitant to bring them up.

Perceived barriers to healthy behaviors have been shown to be the single most powerful predictor of whether people are willing to engage in healthy behaviors.

When promoting health-related behaviors such as vaccinations or STD prevention, finding ways to help people overcome perceived barriers is important. Disease prevention programs can often do this by increasing accessibility, reducing costs, or promoting self-efficacy beliefs.

Cues to Action

One of the best things about the Health Belief Model is how realistically it frames people's behaviors. It recognizes the fact that sometimes wanting to change a health behavior isn't enough to actually make someone do it.

Because of this, it includes two more elements that are necessary to get an individual to make the leap. These two elements are cues to action and self-efficacy.

Cues to action are external events that prompt a desire to make a health change. They can be anything from a blood pressure van being present at a health fair, to seeing a condom poster on a train, to having a relative die of cancer. A cue to action is something that helps move someone from wanting to make a health change to actually making the change.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy wasn't added to the model until 1988. Self-efficacy looks at a person's belief in their ability to make a health-related change. It may seem trivial, but faith in your ability to do something has an enormous impact on your actual ability to do it.

Finding ways to improve individual self-efficacy can have a positive impact on health-related behaviors. For example, one study found that women who had a greater sense of self-efficacy toward breastfeeding were more likely to nurse their infants longer. The researchers concluded that teaching mothers to be more confident about breastfeeding would improve infant nutrition.

Thinking that you will fail will almost make certain that you do. Self-efficacy has been found to be one of the most important factors in an individual's ability to successfully negotiate condom use.

There are six components of the Health Belief Model. They are perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.

Examples and Uses of the Health Belief Model

One important aspect of public health is the design of programs that encourage people to engage in healthy behaviors, so understanding how the health belief model can apply to different situations can be useful.

For example, experts may be interested in understanding public attitudes about cancer screenings. Looking at factors such as perceptions of cancer risk, the benefits of being screened for cancer, and the barriers to being screened can help healthcare professionals look for ways to encourage people to get screened.

The health belief model may also be used for public health programs. Schools, for example, may rely on educational programs to help children understand challenges regarding health, substance use, physical activity, nutrition, and personal safety. Such programs are often based on the health belief model and work to educate, offer skills training, reduce barriers, and boost self-efficacy.

Healthcare professionals and public health experts apply the health belief model to create programs and interventions to help prevent health problems, encourage treatment behaviors , and support behavior change.

How Effective Is the Health Belief Model?

The health belief model has been used for decades to help produce behavior change interventions. Research suggests that the health belief model can help professionals develop strategies that promote healthy behaviors and improve the prevention and treatment of health conditions.

A study published in Health Psychology Review found that, in studies looking at the health belief model, 78% reported significant improvement in behavior adherence. Of the studies they looked at, 39% reported moderate to large effects related to health interventions.

Criticisms of the Health Belief Model

Critics of the health belief model assert that it fails to address:

- How habits can shape decisions

- The fact that people often engage in actions for reasons other than health, such as social acceptance

- Economic and environmental factors, such as living in a food desert or lacking resources to afford fresh fruits and vegetables

- Individual beliefs, attitudes, and other characteristics

- How to change health behaviors rather than merely describe them

The health belief model can help health educators design interventions to improve individual and public health. By understanding the factors that influence health-related choices, healthcare professionals can tackle ways to reduce barriers, improve knowledge, and help motivate action .

The Health Belief Model was created by social psychologists Irwin M. Rosenstock, Godfrey M. Hochbaum, S. Stephen Kegeles, and Howard Leventhal during the 1950s. It was developed for the U.S. Public Health Services to understand why people fail to engage in healthy behaviors.

One of the main benefits of the Health Belief Model is that it simplifies health-related constructs so they can be more readily tested and implemented in public health settings. Because it emphasizes some of the prerequisites for health behaviors, it can be helpful for addressing the things that need to happen before a person can successfully implement a behavior change.

The Health Promotion Model is a multidimensional approach that takes into account how a person's interaction with their environment affects their health choices. It is similar to the Health Belief Model in some ways, but where the HBM is focused on being health-protective, the Health Promotion Model focuses more on helping people improve their well-being and achieve self-actualization .

Ghorbani-Dehbalaei M, Loripoor M, Nasirzadeh M. The role of health beliefs and health literacy in women’s health promoting behaviours based on the health belief model: a descriptive study . BMC Women’s Health . 2021;21(1):421.

Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, Weaver J. The Health Belief Model as an explanatory framework in communication research: Exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation . Health Commun . 2015;30(6):566-576. doi:10.1080/10410236.2013.873363

Loke AY, Chan LK. Maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy and the breastfeeding behaviors of newborns in the practice of exclusive breastfeeding . J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs . 2013;42(6):672-684. doi:10.1111/1552-6909.12250

Montanaro EA, Bryan AD. Comparing theory-based condom interventions: Health belief model versus theory of planned behavior . Health Psychol . 2014;33(10):1251-60. doi:10.1037/a0033969

Baghianimoghadam MH, Shogafard G, Sanati HR, Baghianimoghadam B, Mazloomy SS, Askarshahi M. Application of the Health Belief Model in promotion of self-care in heart failure patients . Acta Med Iran . 2013;51(1):52-8.

Jones CJ, Smith H, Llewellyn C. Evaluating the effectiveness of health belief model interventions in improving adherence: a systematic review . Health Psychol Rev . 2014;8(3):253-69. doi:10.1080/17437199.2013.802623

Carpenter CJ. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior . Health Commun . 2010;25(8):661-9. doi:10.1080/10410236.2010.521906

Orji R, Vassileva J, Mandryk R. Towards an effective health interventions design: An extension of the health belief model . Online J Public Health Inform . 2012;4(3):ojphi.v4i3.4321. doi:10.5210/ojphi.v4i3.4321

Galloway RD. Health promotion: causes, beliefs and measurements . Clin Med Res . 2003;1(3):249-258. doi:10.3121/cmr.1.3.249

By Elizabeth Boskey, PhD Elizabeth Boskey, PhD, MPH, CHES, is a social worker, adjunct lecturer, and expert writer in the field of sexually transmitted diseases.

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

The Health Belief Model

Published by Clyde Scott Brown Modified over 5 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "The Health Belief Model"— Presentation transcript:

Keeping Pre-ERSD Patients Pre-ERSD: Using the Health Belief Model

Introduction Medication non adherence ( noncompliance) remains a major problem. You have to assess and treat adherence related problems that can adversely.

The Health Belief Model Factors Influencing Patient Compliance.

A Presentation by the American Chronic Pain Association

Lecture 3: Health Psychology and Physical Illnesses I (Part 2)

Are you over 35? Are you seeing the doctor today because you have chest or bowel symptoms? Would you be interested in taking part in a research study?

Presinted by :Shahd Amer. Tobacco ads may make you feel like everyone is doing it but they are not. Only about 28% of high school students smoke.

Improving adherence. n Provide more information about the drugs and the treatment. n Tailored regimens are easier to comply with, and there has been some.

Physician Asthma Care Education. Background Excellence in medical treatment is worthless if the patient doesn’t take the medicine Compliance is closely.

Communication Skills Dr. Amro Al-Hibshi Department of Orthopaedics.

Models of Behaviour Change Matt Vreugde

What is Stigma? The negative reaction of people to an individual or group because of some assumed inferiority or source of difference that is degraded.

Chapter 6 Consumer Behavior Chapter 6 slides for Marketing for Pharmacists, 2nd Edition.

Avoiding tobacco use will bring lifelong health benefits.

Risk estimation and the prevention of cardiovascular disease SIGN 97.

1 Health Psychology n Health Promotion Models 2 Today’s Question n Why do people behave in health- compromising ways?

LIZ TATMAN VTS TRAINING SEPT ‘10 Health Belief Model.

Medicare Annual Wellness Exam Presented by: Susan Duden, CPC. March 24, 2012.

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES

Chapter 1 Your Health & Wellness. When looking at total health you should look at the following: 4 How are you feeling 4 Are you alert & well rested?

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clin Interv Aging

Models and theories of health behavior and clinical interventions in aging: a contemporary, integrative approach

W jack rejeski.

1 Department of Health & Exercise Science, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, 27109, USA

Jason Fanning

Background: Historically, influential models and theories of health behavior employed in aging research view human behavior as determined by conscious processes that involve intentional motives and beliefs. We examine the evolution, strengths, and weaknesses of this approach; then offer a contemporary definition of the mind, provide support for it, and discuss the implications it has for the design of behavioral interventions in research on aging.

Methods: A narrative review was conducted.

Results: Traditionally, models and theories used to either predict or change health behaviors in aging have not viewed the mind as encompassing embodied and relational processes nor have they given adequate attention to multi-level, in-the-moment determinants of health behavior.

Discussion: Future theory and research in aging would benefit from a broader integrative model of health behavior. The effects of adverse life experience and changes in biological systems with aging and chronic disease on health behavior warrant increased attention.

Introduction

The health care of older adults is complex requiring varying degrees of commitment on the part of patients to follow prescribed regimens of treatment. These regimens include behaviors such as dietary intake, physical activity, prescription drug use, taking preventive health screenings, and adherence to behavior protocols for physical rehabilitation. As a field, Behavioral Medicine has come to recognize that health behaviors are determined by multiple levels of influence. 1 For example, significant others and interactions with health care providers play a powerful role in shaping the beliefs of older adults. Similarly, what older adults would “like to do” and what they are “able to do” in the realm of health behavior is often determined, in part, by environmental and policy decisions such as access to facilities and reimbursement from Medicare. Of critical importance is that, while theories often conceptualize health behaviors as intentional and under conscious control, this is often not true as is evident in the biological and environmental determinants of addictive behaviors. 2

We open this review by touching on several models and theories of health behavior and/or health behavior change, capturing evolving thought on the topic. Our goal is to demonstrate how models/theories of health behavior have evolved across time and gaps that exist. We then present a contemporary definition for the concept of mind and review support for an integrative model based on this perspective. We believe this model will help to advance intervention development in aging research and foster an interdisciplinary science of health behavior and health behavior change.

A progression in models/theories of health behavior and behavior change

Behavioral scientists have devoted considerable effort to the development and evaluation of models and theories designed to understand and/or influence health behavior. As theory has advanced, scientists have adopted increasing specificity in the conceptual definition and measurement of constructs while becoming more interested in behavior change over understanding why individuals engage in particular health behaviors. Additionally, there has been increased interest in affect as well as the physiological and environmental input to health behavior and health behavior change. To illustrate the evolution of extant models/theories and the current state-of-the-art, we discuss the health belief model, the Social Cognitive Theory, the relapse prevention model, self-determination theory, research on affect and a biological model of desire, along with the socio-ecological model.

Health belief model (HBM)

The HBM first appeared in the 1950s as a guide to research on tuberculosis screening. 3 , 4 It distilled concepts from an established body of psychological and behavioral research and set the stage for the theories that followed. HBM is an expectancy-value model. As an example, people take medication to control their cholesterol because they value avoiding cardiovascular disease. Core constructs include perceived threat of a given disease state, which is the product of perceived susceptibility to the disease and perceived disease severity. The model also emphasizes decisional balance: the relative weight of perceived benefits as compared to perceived barriers to engaging in a behavior. As shown in Figure 1 , health behavior results from the combined effect of perceived threat and decisional balance over anticipated outcomes. 4 The HBM acknowledges the input on health behavior from other factors such as psychosocial variables and environmental cues, but it conceptualizes these effects as acting through either perceived threat or decisional balance . Of note, HBM practitioners have long recognized the limited scope of the model. For instance, as Janz and Becker noted: 4 “It is clear that other forces influence health actions as well; for example…some behaviors (eg, cigarette smoking; tooth-brushing) have a strong habitual component obviating any ongoing psychosocial decision-making process”.

The health belief model.

Note: Adapted from Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model - a decade later. Health Ed Quart . 1984;11(1):1–47. Copyright 1984, with permission from SAGE Publications. 4

Social cognitive theory (SCT)

As a second approach to models/theories of health behavior, we focus on Bandura’s SCT. 5 As with HBM, SCT conceptualizes individuals as rational actors. While there is continued emphasis on the concept of expectancy-value, a chief advancement of SCT is its focus on personal agency and the importance of context as a determinant of health behavior. Moreover, while SCT has been useful in understanding why people perform a specific health behavior, it has also had a major effect on interventions for behavior change.

Self-efficacy, or one’s perceived ability to bring about a specific course of action in a particular context, is the core construct in SCT. Efficacy beliefs are dynamic, affecting and being affected by several downstream constructs highlighted in SCT (see Figure 2 ). These include outcome expectations and barriers/facilitators of behavior that arise from both social relations and cultural forces. Individuals with higher self-efficacy for a behavior are likely to have higher expectations for associated outcomes. They also perceive greater support from the social and physical environment and engage in more favorable self-regulatory behaviors than those with low self-efficacy. Success with the behavior fuels self-efficacy, especially when success occurs in the face of challenge. In addition, encouragement from others and observing relatable peers or those less skilled having success with a given behavior also enhances self-efficacy. Finally, one’s physiological state has an immediate influence on self-efficacy. For example, Bandura calls forth the image of preparing for a public speaking event. As anxiety mounts in preparing to deliver a talk, some individuals become hypersensitive to physical symptoms such as rising heart rate, increasingly sweaty palms, and a queasy stomach. The result is that they experience a sharp, in-the-moment decline in their speech-related self-efficacy.

Social cognitive theory.

Note: Aadapted from Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164, copyrught 2004 by permission of SAGE Publications. 6

In part, the appeal of SCT arises from its specificity. 7 Other contemporary theories, such as the theory of planned behavior, prioritize parsimony and do not address behavior change. 8 , 9 SCT also offers interventionists clear targets for improving efficacy beliefs, supporting self-regulation, minimizing external barriers, and bolstering positive outcome expectancies. Moreover, it explicitly models the interplay between underlying transient biological states, one’s sense of agency, and the influence of proximal socio-structural pressure. Unfortunately, these key considerations are typically lost in implementation, with the focus constrained to individual-level perceptions and the influence of proximal social connections. 7

Relapse prevention (RP)

The third model of health behavior that we chose for inclusion is RP for addictive behavior. 10 RP is a model targeted specifically to behavior change. As an outgrowth of SCT, the intent behind RP was to describe the process of relapse for addictive behavior, emphasizing the importance of early intervention. They conceptualized relapse as an expected and transitional process; a key aim is to avoid or to learn how to cope with high-risk situations.

RP identified two categories of factors that contribute to a risk for relapse: immediate determinants and covert antecedents. Akin to Bandura’s recognition that transient, in-the-moment physiological states can exert substantial influence on self-efficacy, RP proposes that high-risk situations serve a similar function. They are immediate (in-the-moment) determinants of addictive behavior. These range from social and physical environments, to internal states such as depression or negative affect. Another immediate determinant, coping, captures how an individual responds to a high-risk situation. Outcome expectancies are a third determinant, in that individuals who expect short-term benefits such as reduced anxiety from the behavior are more likely to relapse. The fourth immediate determinant is the abstinence violation effect, which refers to the feeling of guilt or lack of control accompanying a single lapse.

Covert antecedents of relapse are a partial determinant of whether an individual successfully negotiates immediate determinants. Here, lifestyle factors, including both positive and pleasurable activities alongside one’s responsibilities contribute to or alleviate stress, which in turn is related to the likelihood of a relapse. More recent iterations of the model 11 specify both trait-like—tonic — influences on relapse, which are thought to dictate initial susceptibility to a relapse, and more dynamic and transient influences—phasic. Phasic influences include momentary mood states, urges and cravings, and in-the-moment changes in self-efficacy or outcome expectations. These phasic influences represent the most proximal determinants of a relapse.

Although not explicitly stated in RP, an interesting feature is the awareness that conscious goals related to recovery often succumb to the physiological symptoms of withdrawal, negative affective states, and the emotional tipping point created by the abstinence violation effect. Thus, it is not surprising to find that recent research on mindfulness-based treatment techniques specific to RP (MBRP) have been successful in countering the influence of negative affective states on the likelihood of relapse, and enhancing individuals’ abilities to cope with distress. 12 , 13

Self-determination theory (SDT)

We believe it is important to briefly discuss Deci and Ryan’s SDT 14 because it unites concepts from SCT (eg, goal setting; mastery), RP (eg, one’s inner state affects motivated behavior), the motivational role of affect in behavior by way of enjoyment, and the importance of strong social ties. SDT posits that humans are driven by three core needs: the need to experience competence, meaningful social connection (ie, relatedness), and autonomy (ie, a sense of control over one’s behaviors). The core needs outlined in SDT are positioned to be innately valued, and as with other theories, Deci and Ryan underscore the importance of aligning the content of one’s goals with an individual’s core needs. 14 For instance, an exercise goal formed for the explicit purpose of looking better to one’s peers, an extrinsic personal goal, will lose salience more rapidly than an intrinsic exercise goal emanating from the value of human connection and formed for the purpose of being able to engage with one’s grandchildren or to foster a relationship with friends. 15

Moreover, the ways in which these goal-driven behaviors are regulated are given importance in SDT. An intrinsically motivated behavior is one that brings about feelings of interest, enjoyment, or satisfaction, and it is theorized that this produces self-motivated, or self-determined behavior that is likely to last. When the behavior is motivated by factors aside from the merits of the behavior itself, it is said to be externally regulated. These more “controlling” forms of motivation are expected to sometimes regulate short-term behavior, but have a low likelihood of facilitating behavioral maintenance. 15

There are several important conclusions to be drawn from research on SDT and health behavior. As with research on incentives and affective valence described below, SDT highlights the importance of maximizing behaviors that produce positive bodily states such as enjoyment. It also provides a useful framework for considering appropriate incentives. Namely, by emphasizing incentives that are intrinsic as opposed to extrinsic. Lastly, it underscores the value of leveraging the group as a tool of behavior change; a notion we will highlight in the final section of this manuscript.

Incentives/affect

Although the motivational significance of incentives and affective valence that people associate with particular outcomes of a health behavior are evident in the concept of expectancy-value, within contemporary theoretical frameworks it is frequently assumed that people value their health and the focus of most research has been on self-efficacy, outcomes expectation, and behavioral intention. 7 Researchers traditionally assumed that increases in self-efficacy are valued because they increase a sense of personal agency. 5 , 16 One exception is research on RP in which researchers clearly appreciate the role of physiological withdrawal on relapse and the fact that addictive substances are often valued as a means of coping with life stress. 11

There has been a surge of interest in the affective determinants of health behavior, including work on both reflective and reflexive affect. 17 Reflective affect is cognitive based and referred to as “subjective liking”, whereas reflexive affect has been characterized as “core liking”, the pure, abrupt, visceral experience that is a function of contextual stimuli and associations. 18 Reflexive affect can be an in-the-moment experience or anticipatory in nature. Rhodes and Gray 19 recently note that most research on affect and health behavior has focused on reflective as opposed to reflexive affect. Although not conducted on older adults, reviews of the exercise literature have shown that reflexive affect may be more important in predicting future exercise behavior than reflective affect or social cognitive variables. 20

Given the growing interest in reflexive affect 17 and the importance of incentives to health behavior, there are important lessons to be learned from work in the biology of addiction. In the “Biology of Desire”, Lewis 2 describes the neuroscience of how substances and behaviors of desire become habitual through activity in the reward network. The central axis for desire begins in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain. Activation of this region of interest provides the fuel for desire—dopamine! Other key areas of the brain involved in impulsive behavior—the initiation of an addictive behavior—include the ventral and dorsal striatum, amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC). In the early stages of desire for a substance or behavior, both nonconscious and conscious processing are involved. The amygdala acquires and maintains emotional sensations and communicates with the hippocampus, a structure that stores explicit memories of experience. The ventral striatum is responsible for feelings of attraction, desire, and craving. It is the main driver for impulsivity, getting its fuel from the VTA. The PFC creates conscious, context-specific interpretations of highly motivating situations and is key to executive function, planning, bringing memories into consciousness, sorting and comparing memories, and making decisions.

Once a person has been repeatedly exposed to a desired substance or behavior, involvement of the PFC in the reward network weakens to the point where conscious processing is no longer involved—the dorsal lateral region of the striatum has led to addiction, a compulsive act. The substance or behavior is now a habit: stimuli lead to a response (S-R) in the absence of conscious thought. We believe this model describing the biology of desire is important for several reasons. First, desire—or the incentive value of a behavior—is applicable to both functional and dysfunctional health behaviors. Second, as this model illustrates, intervention development would benefit from integrating concepts from neuroscience into the study of health behavior change. Third, as we will see later, there may be important neural phenotypes that could assist in tailoring treatment. Fourth, we believe this model is applicable to understanding incentives or desire more generally; habits vary in their strength! If we hope to promote health behaviors among older adults, there is little question that we need to discover the motivational levers that operate for different people in varied contexts. Fifth, we believe a focus on desire has wide application to the design of behavioral interventions and should give pause to health scientists implementing aversive interventions such as highly popular high-intensity physical activity training regimens.

Socio-ecological models

Finally, it is important to note the growing popularity of ecological models of health behavior. Drawn from a biological sciences view of ecology, which is interested in capturing the interplay between an organism and its environment, socio-ecological models identify multiple levels of influence, typically ranging from individual factors such as one’s biological state to broader community, geopolitical, and policy influences. 21 – 23

A key assumption of these models is that researchers can study individuals at various levels of influence, including the individual, community, state, or national level. However, effective health behavior change likely needs to consider the individual as affected by these various levels of influence. For instance, the likelihood an individual sets a goal to eat better, engage in exercise, commute in an active manner, or reduce sitting will be influenced by their built (eg, are there bike paths and healthy food options?) and social (eg, do social norms support healthy behavior?) environments. Similarly, the extent to which the environment is low-stress and perceived as safe may help or hinder an individuals’ ability to adhere to behavioral goals. 24 , 25 They also recognize that environments and those existing within them are in a constant state of flux; thus, interventions should be flexible and adaptable. 23 Clearly, social-ecological approaches to behavior change require considerable resources and time relative to individual-level interventions; however, they also underscore the important role that social and physical environments have on health behaviors, a point we will come back to later.

Across the models/theories reviewed, there is general acceptance for the concept of expectancy-value. That is, people engage in health behaviors because of the belief that the behavior will yield outcomes of value. It is interesting to note that, with the emergence of SCT, the focus has been on self-efficacy even though it is one of the several core constructs alongside incentives and outcome expectations. Although the role of affect and physiological states on health behavior is apparent in SCT, the theory posits that self-efficacy mediates these effects. In addition, it is surprising that researchers have paid so little attention to the incentives underlying health behaviors, how incentives and goals benefit from being linked to core needs central to SCT, and how the affect associated with the incentive value of health behavior may be tempered by the sacrifices that older adults are often required to make when changing their behavior.

Of note is the fact that, as models and theories of health behavior have evolved, there has been an increasing conceptual focus on behavior change. In fact, RP identified the importance of phasic determinants of behavioral maintenance, emphasizing the role of reflexive affect. Peoples’ psychological and physiological states can change over relatively brief periods and cause dramatic shifts in behavioral intentions. Finally, as far back as 1984, Janz and Becker recognized that conscious, decision-based models such as HBM could not explain all health behaviors, specifically noting the habitual drive underlying behaviors such as cigarette smoking. Supported by recent trends in neuropsychology, future research in intervention development must consider the role played by nonconscious processes and, in particular, how to modify these processes.

The concept of mind: theory development and scientific inquiry

We believe there is merit in stepping back for a moment to reconsider the concept of “mind” in greater depth. The reason for this reflection is that how theoreticians/researchers think about the mind heavily influences what they believe to be the primary drivers of behavior. Traditionally separated from the body, behavioral science has conventionally viewed the mind as a faculty of being human that enables people to have an awareness of the world and of their experience; it is responsible for consciousness and gives humans the capacity to think and to feel. The role of the mind or lack thereof in theory development is perhaps most evident the classic work of B.F. Skinner. Skinner proposed that the mind was irrelevant to understanding human behavior; rather, he argued that people behave in response to operant conditioning to reinforcement and/or punishment; promoting the concept of environmental engineering as a means for shaping behavior. Even in contemporary thinking, concepts such as “nudging”, 26 popular in behavioral economics, have shown that some desired health behaviors can be achieved through positive incentives or indirect influence; reemphasizing the point that in some instances the mind, when defined by traditional criteria of awareness, thinking, and feeling, is irrelevant to human behavior. Alternatively, the cognitive revolution that followed Behaviorism and continues to be favored by many theoreticians, places an emphasis on conscious, cognitive processes as determinants of health behavior. 7

As we consider why older adults do or do not behave optimally within the context of medical research or health care, we will continue to reinforce the notion that the health behavior of older adults requires considering multiple levels of influence, some of which obviate the need for conscious decision-making. We will also emphasize that human behavior is not always rational, and that implicit memories and biased processing of information are more common than currently recognized. Most important, we believe that a more complete understanding of why older adults behave as they do within the context of medical research and health care would emerge from a broader, alternative view of the mind. Specifically, we adopt the position that the mind should be conceptualized as a process rather than as an outcome such as a thought or feeling, noting that this process is responsible for regulating energy and information flow, and that this process is both embodied and relational.

The Mind as a Process and Implications for Health Behavior

Paraphrasing Siegel, 27 the human mind is a process that regulates the flow of energy and information between the body, brain, and relationships—thus, it is both embodied and relational (see Figure 3 ). As we will soon demonstrate, defining the mind as a process is consistent with Hebb’s 28 concept of associative learning: neurons that fire together wire together. What begins as energy through activation of neurons eventually becomes information that then defines learning and the formation of memories. Furthermore, as Siegel pointed out, the flow of energy and information occurs not only in the brain, but in conjunction with the body and relationships as well. Conceptualizing the mind as embodied is critically important to understanding health behavior for two reasons. First, it positions various biological inputs that may be either stable or unstable as important determinants of subjective experience and behavior. And second, Glass and McAtee 29 argue that features of the social, built and natural environment become embodied and act as “risk-regulators” that effect health behavior via various biological pathways. In other words, toxic environments adversely affect biological regulatory systems. These systems then become “internal risk regulators” that can have powerful effects on health behavior.

The mind as a process.

Note: Reprinted from Lucas AR, Klepin HD, Porges SW, Rejeski WJ. Mindfulness-based movement: a polyvagal perspective. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2018;17(1):5–15. 30

This complex, co-dependency between molecules, the mind, and the environment has also been supported by McEwen 31 and is obvious in the area of drug addiction where toxic microenvironments influence exposure to drugs 32 that then lead to molecular and cellular adaptations in the body that result in drug abuse. 33 Drug abuse also leads to other behaviors that can compromise health such as exposure to violence and a rapid drop off in self-care.

When Siegel noted that the mind is relational, he emphasized that the human brain is engaged in a constant flow of energy and information with other people. In fact, as we have just described, micro-social environments serve as a “risk regulator” of drug use. The powerful role of social relationships on health behavior is not surprising. We all enter this world dependent on others for our survival; as one leading neuroscientist puts it, our brains are wired to connect with others. 34 It is important to note that Siegel’s focus on the relational mind emphasized the effect that attachment through close interpersonal relations in childhood has on behavior and well-being. We agree that early interpersonal attachment experience plays an important role in health behavior not only in infancy but also across the lifespan. However, as we note above and consistent with Glass and McAtee, 29 we would argue that the relational mind encompasses powerful influences from social, built, and natural environments that range from the micro to macro levels of analysis.

Figure 4 provides a conceptual model of health behavior that describes the interrelationships between the relational mind (box to the left) and the biological regulatory systems that embody relational experiences (the box to the right). Embodiment occurs when relational experiences alter biological regulatory systems (BRS) through their effects on genetic and biological substrates of these systems. Note the distinction between the body and brain in depicting the BRS. Activity within the BRS at the level of the body directly influences neural networks and neural networks affect functioning of the BRS at the level of the body. Neural networks in the brain give rise to both conscious and nonconscious levels of processing. Of particular importance to models/theories of behavior change is that, for the most part, they operate at the level of conscious processing and ignore the fact that neural networks below the level of consciousness are critically important to health behavior and health behavior change. We also want to emphasize that BRS of the body can effect behavior through both conscious and nonconscious processing. Because our relational experience alters biological regulatory structures of the body and brain, these experiences also affect health behavior through these same pathways. This is readily apparent in how social and physical environmental factors support obesogenic behavior, including physical inactivity. 35

An embodied and relational model of health behavior.

The embodied mind

In addition to addiction, there is a large body of literature supporting the notion that biological regulatory systems influence health behavior either through their effects on conscious subjective experience or via nonconscious processes. An example of such nonconscious effects that comes to mind is the phenomenon termed “sickness behavior”, a cluster of behaviors including decreased movement and increased time spent sleeping, lack of appetite, and the propensity for social isolation. Specifically, what we now know is that the release of interleukin-1 from the immune system stimulates the vagus nerve and, independent of the specific illness, has effects on the central nervous system that fuel this cluster of behavior. 36 Perhaps an even more glaring reminder of the embodied mind is depression. Tiermeier, 37 underscoring the public health significance of this disease in late life, concluded that over 50% of those with severe depression have disturbed glucocorticoid feedback mechanisms. Depression is also common with increasing comorbid conditions associated with aging, a phenomenon that appears to be related to inflammation and cell-mediated immune activation. 38 Not surprisingly, researchers have investigated the adverse effects that depression has on expectations and motives to engage in desired health behavior. For example, it is well known that depression is related to obesity 39 and sedentary behavior. 40 Additionally, there is evidence that digestive health plays a role in affect and emotion 41 and that gut bacteria can motivate people to pursue the consumption of specific macronutrients. 42 Data suggest that inflammation is a correlate of inactivity. 43 – 45 Moreover, body fat is associated with increased inflammation, whereas intentional weight loss in older adults lowers body fat and reduces inflammation. 46

Equally important is an awareness and appreciation of the fact that dynamic changes in biological regulatory systems and their substrates across relatively brief periods can profoundly influence functional brain networks and subjective states. For example, in a study of obese older adults, we found that craving for favorite foods dramatically increased over a period of 3 hrs when restricted to consume water only versus ingesting a meal replacement. 47 Even more interesting was the fact that following this brief fasting period, functional imaging of the resting state brains in the water only condition looked similar to what you would see in other addictive behaviors, brain states that differed dramatically from resting states taken following consumption of a meal replacement.